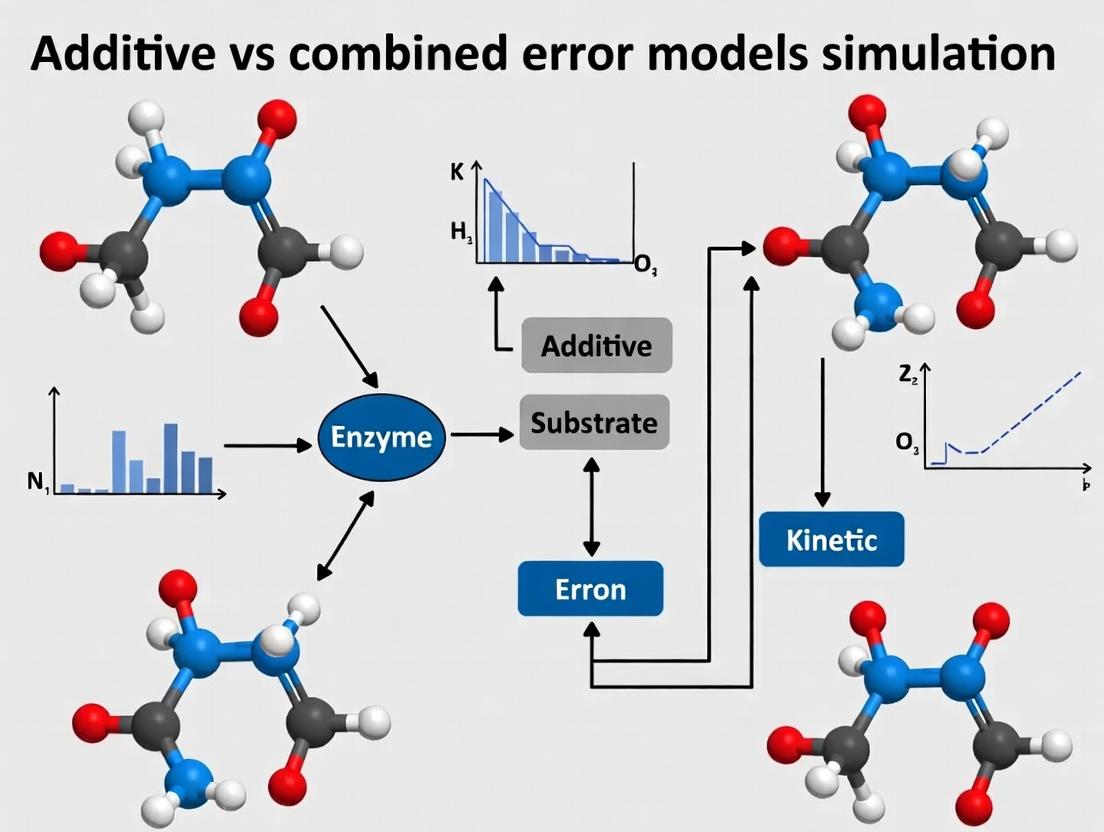

Additive vs. Combined Error Models in Pharmacometric Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides an in-depth exploration of additive and combined error models in simulation-based pharmacometric and biomedical research.

Additive vs. Combined Error Models in Pharmacometric Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides an in-depth exploration of additive and combined error models in simulation-based pharmacometric and biomedical research. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts of residual error variability, practical implementation methods in software like NONMEM and Pumas, troubleshooting strategies using graphical diagnostics, and comparative validation through simulation studies. The scope includes theoretical frameworks, application case studies, optimization techniques, and performance evaluation to enhance model accuracy and reliability in pharmacokinetics, clinical trial design, and related fields.

Foundations of Error Models: From Basic Concepts to Advanced Theory

Introduction to Residual Error and Unexplained Variability in Pharmacometric Modeling

Foundational FAQs: Core Concepts

Q1: What exactly is Residual Unexplained Variability (RUV) in a pharmacometric model? RUV, also called residual error, represents the discrepancy between an individual's observed data point (e.g., a drug concentration) and the model's prediction for that individual at that time [1]. It is the variability "left over" after accounting for all known and estimated sources of variation, such as the structural model (the PK/PD theory) and between-subject variability (BSV) [2]. RUV aggregates all unaccounted-for sources, including assay measurement error, errors in recording dosing/sampling times, physiological within-subject fluctuations, and model misspecification [3] [1].

Q2: What is the difference between "Additive," "Proportional," and "Combined" error models? These terms describe how the magnitude of the RUV is assumed to relate to the model's predicted value.

- Additive (Constant) Error: The variance of the residual error is constant, independent of the predicted value. It is suitable when the measurement error is absolute (e.g., ± 0.5 mg/L) [4].

- Proportional (Multiplicative) Error: The standard deviation of the residual error is proportional to the predicted value. This means the error is relative (e.g., ± 10% of the predicted concentration) [4].

- Combined Error: This model incorporates both additive and proportional components, making it the most flexible and commonly used for pharmacokinetic data. It accounts for both a fixed lower limit of detection (additive) and a relative component that scales with concentration [5] [6].

Q3: How does misspecifying the RUV model impact my analysis? Choosing an incorrect RUV model can lead to significant issues [3] [7]:

- Bias in Parameter Estimates: Misspecification can cause systematic bias (inaccuracy) in the estimation of key pharmacokinetic parameters like clearance or volume of distribution.

- Incorrect Precision Estimates: The standard errors and confidence intervals for your parameter estimates may be invalid, affecting statistical inference [7].

- Poor Predictive Performance: A model with a misspecified error component will generate unrealistic simulations, as it does not correctly characterize the variability in the observed data [5].

Q4: What are the primary sources that contribute to RUV in a real-world study? RUV is a composite of multiple factors [3] [2] [8]:

- Assay and Measurement Error: The inherent imprecision and inaccuracy of the bioanalytical method.

- Protocol Execution Errors: Deviations from the nominal timing of dose administration or blood sample collection.

- Data Handling Errors: Mistakes in data entry, transcription, or sample labeling.

- Model Misspecification: Using an incorrect structural model (e.g., one-compartment when the true system is two-compartment) leaves unexplained variability that is absorbed into the RUV.

- Unmodeled Dynamical Noise: True biological within-individual variation over time that is not captured by the model structure.

Table 1: Properties of Common Residual Error Models

| Error Model | Mathematical Form (Variance, Var(Y)) | Typical Use Case | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive | Var(Y) = σ² | Assay error is constant across concentration range. Simple, stable estimation. | Does not account for larger absolute errors at higher concentrations. | |

| Proportional | Var(Y) = (μ · σ)² | Error scales with the observed value (e.g., %CV). Appropriate for data spanning orders of magnitude. | Can fail at very low concentrations near zero. | |

| Combined (Variance) | Var(Y) = σadd² + (μ · σprop)² [5] [4] | Most PK data, where both a limit of detection and proportional error exist. Flexible; accounts for both absolute and relative error. | Requires estimation of two RUV parameters. | |

| Log-Normal | Var(log(Y)) ≈ σ² [4] | Alternative to proportional error; ensures predictions and errors are always positive. | Naturally handles positive-only data. | Parameters are on log scale, which can be less intuitive. |

Troubleshooting Guides & Advanced FAQs

Q5: My diagnostic plots show a pattern in the residuals vs. predictions. What does this mean, and how do I fix it? Patterns in residual plots indicate a potential misspecification of the structural model, the RUV model, or both [9].

- Funnel Shape (Residuals fan out as predictions increase): This is classic heteroscedasticity. Your error is proportional, but you are using an additive model. Solution: Switch to a proportional or combined error model.

- Trend or Slope (Residuals are not centered around zero across the prediction range): The structural model is biased. It consistently over- or under-predicts in certain concentration ranges. Solution: Re-evaluate the structural model (e.g., consider an extra compartment, non-linear elimination).

- U-shaped Pattern: Suggoses systematic model misspecification. Solution: Investigate alternative structural models and ensure the RUV model is appropriate [9].

Table 2: Key Diagnostic Tools for RUV Model Evaluation [9]

| Diagnostic Plot | Purpose | Interpretation of a "Good" Model |

|---|---|---|

| Conditional Weighted Residuals (CWRES) vs. Population Predictions (PRED) | Assesses adequacy of structural and RUV models. | Random scatter around zero with no trend. |

| CWRES vs. Time | Detects unmodeled time-dependent processes. | Random scatter around zero. |

| Individual Weighted Residuals (IWRES) vs. Individual Predictions (IPRED) | Evaluates RUV model on the individual level. | Random scatter around zero. Variance should be constant (no funnel shape). |

| Visual Predictive Check (VPC) | Global assessment of model's predictive performance, including variability. | Observed data percentiles fall within the confidence intervals of simulated prediction percentiles. |

Q6: When should I use a combined error model vs. a simpler one? A combined error model should be your default starting point for most pharmacokinetic analyses [5]. Use a simpler model only if justified by diagnostics and objective criteria:

- Start with Combined: Fit a combined (additive + proportional) error model as your base.

- Diagnostic Check: Examine the IWRES vs. IPRED plot. If the variance is constant (no funnel), the proportional component may be negligible.

- Objective Test: Use the Objective Function Value (OFV). Fit a proportional-only model and an additive-only model. A drop in OFV of >3.84 (for 1 degree of freedom, p<0.05) for the combined model versus a simpler one justifies the extra parameter [1].

- Parameter Precision: If the estimate for either the additive (

σ_add) or proportional (σ_prop) component is very small with a high relative standard error, it may be redundant.

Q7: What are advanced strategies if standard error models (additive, proportional, combined) don't fit my data well? If diagnostic plots still show skewed or heavy-tailed residuals after testing standard models, consider these advanced frameworks [7]:

- Dynamic Transform-Both-Sides (dTBS): This approach estimates a Box-Cox transformation parameter (

λ) alongside the error model. It handles skewed residuals. Aλof 1 implies no skew, 0 implies log-normal skew, and other values adjust for different skewness types [7]. - t-Distribution Error Model: This model replaces the normal distribution assumption for residuals with a Student's t-distribution. It is robust to heavy-tailed residuals (more outliers) because the t-distribution has heavier tails than the normal. The degrees of freedom (

ν) parameter is estimated; a lowνindicates heavy tails [4] [7]. - Time-Varying or Autocorrelated Error: For residuals showing correlation over time within a subject, consider models with serial correlation (e.g., autoregressive AR(1) structure) [8].

Experimental Protocols for Simulation Research

Protocol 1: Simulating the Impact of RUV Model Misspecification This protocol, based on methodology from Jaber et al. (2023), allows you to quantify the bias introduced by using the wrong error model [3].

- Define a "True" Pharmacokinetic Model: Use a known model (e.g., a two-compartment IV bolus model with parameters: CL=5 L/h, V1=35 L, Q=50 L/h, V2=50 L). Assign realistic between-subject variability (e.g., 30% CV log-normal) [3].

- Define a "True" RUV Model: Specify the true error structure, e.g., a combined error with

σ_add=0.5 mg/Landσ_prop=0.15 (15%). - Generate Simulation Datasets: Use software like

mrgsolveorNONMEMto simulate 500-1000 replicate datasets of 100 subjects each, following a realistic sampling design [3]. - Estimate with Misspecified Models: Fit three different RUV models to each simulated dataset: the true combined model, a proportional-only model, and an additive-only model.

- Calculate Performance Metrics: For each replicate and each fitted model, calculate:

- % Bias: ((Median Estimated Parameter - True Parameter Value) / True Parameter Value) * 100.

- Relative Root Mean Square Error (RRMSE): A measure of imprecision (random error).

- Compare the magnitude of RUV (

σ) estimates across the different fitted models.

- Analysis: Summarize the bias and imprecision across all replicates in tables and boxplots. You will typically observe that misspecified models yield biased PK parameters and incorrect estimates of the RUV magnitude [3].

Protocol 2: Comparing Coding Methods for Combined Error (VAR vs. SD) This protocol investigates a technical but crucial nuance in implementing combined error models [5] [6].

- Theory: Two common mathematical implementations exist:

- Method VAR: Assumes total variance is the sum of independent additive and proportional variances:

Var(Y) = σ_add² + (μ · σ_prop)²[5]. - Method SD: Assumes total standard deviation is the sum:

SD(Y) = σ_add + μ · σ_prop.

- Method VAR: Assumes total variance is the sum of independent additive and proportional variances:

- Simulation: Simulate datasets using Method VAR as the true generating process.

- Estimation: Fit the same datasets using software code that implements Method VAR and code that implements Method SD.

- Outcome: You will find that both methods can fit the data, but the estimated values for

σ_addandσ_propwill differ between methods. Crucially, the structural parameters (CL, V) and their BSV are largely unaffected [6]. - Critical Recommendation: The simulation tool used for future predictions must use the same method (VAR or SD) that was used during model estimation to avoid propagating errors [5] [6].

Visualization Workflows

Decision Workflow for Error Model Selection & Diagnosis

Visualizing the Path from Data to Residual Diagnostics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Packages for RUV Modeling & Diagnostics

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in RUV Research | Key Feature / Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| NONMEM | Industry-Standard Estimation Software | Gold-standard for NLMEM estimation. Used to fit complex error models and perform likelihood-based comparison (OFV). | Implements Method VAR and SD for combined error; supports user-defined models [5]. |

| R (with packages) | Statistical Programming Environment | Data processing, simulation, and advanced diagnostics. The core platform for custom analysis. | ggplot2 (diagnostic plots), xpose/xpose4 (structured diagnostics), mrgsolve (simulation) [3]. |

| Pumas | Modern Pharmacometric Suite | Integrated platform for modeling, simulation, and inference. | Native support for a wide range of error models (additive, proportional, combined, log-normal, t-distribution, dTBS) with clear syntax [4]. |

| Monolix | GUI-Integrated Modeling Software | User-friendly NLMEM estimation with powerful diagnostics. | Excellent automatic diagnostic plots and Visual Predictive Check (VPC) tools for RUV assessment [9]. |

| Perl-speaks-NONMEM (PsN) | Command-Line Toolkit | Automation of complex modeling workflows and advanced diagnostics. | Executes large simulation-estimation studies, calculates advanced diagnostics like npde, and automates VPC [9]. |

In pharmacological research and drug development, mathematical models are essential for understanding how drugs behave in the body (pharmacokinetics, PK) and what effects they produce (pharmacodynamics, PD). A critical component of these models is the residual error model, which describes the unexplained variability between an individual's observed data and the model's prediction [2]. This discrepancy arises from multiple sources, including assay measurement error, model misspecification, and biological fluctuations that the structural model cannot capture [2].

Choosing the correct error model is not a mere statistical formality; it is fundamental to obtaining unbiased and precise parameter estimates. An incorrect error structure can lead to misleading conclusions about a drug's behavior, potentially impacting critical development decisions. Within the context of nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NONMEM), the three primary structures are the additive (constant), proportional, and combined (additive plus proportional) error models [10]. This guide defines these models, provides protocols for their evaluation, and addresses common troubleshooting issues researchers face.

Core Definitions and Mathematical Structures

Error models define the relationship between a model's prediction (f) and the observed data (y), incorporating a random error component (ε), which is typically assumed to follow a normal distribution with a mean of zero and variance of 1 [10].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, mathematical formulations, and typical applications of the three primary error models.

| Error Model Type | Mathematical Representation | Standard Deviation of Error | Description & When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Additive (Constant) | y = f + aε [10] | a [10] | The error is an absolute constant value, independent of the predicted value. Use when the magnitude of measurement noise is consistent across the observed range (e.g., a scale with a constant ±0.5 mg precision) [11] [12]. |

| Proportional | y = f + b|f|ε [10] | b|f| [10] | The error is proportional to the predicted value. The standard deviation increases linearly with f. Use when the coefficient of variation (CV%) is constant, common with analytical methods where percent error is stable (e.g., 5% assay error) [10] [2]. |

| Combined | y = f + (a + b|f|)ε [10] | a + b|f| [10] | A hybrid model incorporating both additive and proportional components. It is often preferred in PK modeling as it can describe a constant noise floor at low concentrations and a proportional error at higher concentrations [5] [6]. |

Key Notes on Implementation:

- The combined error model can be implemented differently in software. The common "VAR" method assumes the variance is the sum of the two independent components:

Var(error) = a² + (b*f)²[4]. An alternative "SD" method defines the standard deviation as the sum:SD(error) = a + b*|f|[5] [6]. - The log-transformed equivalent of the proportional error model is the exponential error model: y = f · exp(aε), often used to ensure predicted values remain positive [10] [4].

Experimental Protocol: Comparing Combined Error Model Implementations

A key methodological study by Proost (2017) compared the VAR and SD methods for implementing the combined error model in population PK analysis [5] [6]. The following protocol is based on this research.

Objective: To evaluate the impact of two different mathematical implementations (VAR vs. SD) of the combined error model on the estimation of structural PK parameters, inter-individual variability (IIV), and residual error parameters.

Materials & Software:

- Software: NONMEM (or equivalent like Monolix, Pumas [4]).

- Data: Real or simulated PK dataset with sufficient observations across the concentration range.

- Computing Environment: Standard workstation capable of running nonlinear mixed-effects modeling software.

Procedure:

- Model Development: First, develop the structural PK model (e.g., 2-compartment IV) and identify sources of IIV.

- Error Model Implementation:

- Implement the combined error model using the VAR method:

Y = F + SQRT(THETA(1)2 + (THETA(2)*F)2) * EPS(1). - Implement the combined error model using the SD method:

Y = F + (THETA(1) + THETA(2)*F) * EPS(1). - In both cases,

THETA(1)estimates the additive component (a) andTHETA(2)estimates the proportional component (b).

- Implement the combined error model using the VAR method:

- Model Estimation: Estimate parameters for both model implementations using the same estimation algorithm (e.g., FOCE with interaction).

- Comparison & Evaluation:

- Record the final parameter estimates for PK parameters, their IIV, and the residual error parameters (a and b).

- Compare the objective function value (OFV). A difference >3.84 (χ², 1 df) suggests one model fits significantly better.

- Perform visual predictive checks (VPC) and analyze diagnostic plots (e.g., conditional weighted residuals vs. population prediction) for both models.

Expected Results & Interpretation: Based on the findings of Proost [5] [6]:

- The VAR and SD methods are both valid, and selection can be based on the OFV.

- The values of the error parameters (a, b) will be lower when using the SD method compared to the VAR method.

- Crucially, the values of the structural PK parameters and their IIV are generally not affected by the choice of method.

- Critical Consideration: If the model is used for simulation, the simulation tool must use the same error model method (VAR or SD) as was used during estimation to ensure consistency and accuracy [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: How do I choose between an additive, proportional, or combined error model for my PK/PD analysis? A1: The choice is primarily data-driven and based on diagnostic plots.

- Plot Conditional Weighted Residuals (CWRES) vs. Population Predicted Value (PRED): If the spread of residuals is constant across all predictions, an additive model may be suitable. If the spread widens as the prediction increases, a proportional model is indicated. If there is wide scatter at low predictions that tightens and then widens proportionally at higher values, a combined model is often necessary [2].

- Use Objective Function Value (OFV): Nest the models. The combined model nests both the additive and proportional. A significant drop in OFV (>3.84 points) when adding a parameter supports the more complex model.

- Consider the assay characteristics: Understand the validated performance of your bioanalytical method—its lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) and constant vs. percent error characteristics [2].

Q2: My model diagnostics show a pattern in the residuals even after trying different error models. What should I do? A2: Patterns in residuals (e.g., U-shaped trend) often indicate structural model misspecification, not just an error model issue [2].

- Re-evaluate your structural model: Consider alternative PK models (e.g., 3-compartment vs. 2), different absorption models, or more complex PD relationships.

- Investigate covariates: Unexplained trends may be explained by incorporating patient covariates (e.g., weight, renal function) on PK parameters.

- Check for data errors: Verify dosing and sampling records, and ensure BLQ (below limit of quantification) data are handled appropriately (e.g., M3 method for censored data [4]).

Q3: What does a very high estimated coefficient of variation (CV%) for a residual error parameter indicate? A3: A high CV% (e.g., >50%) for a proportional error parameter suggests the model is struggling to describe the data precisely [2]. Possible causes:

- Over- or under-parameterization: The structural model may be too complex for the data or too simple to capture the true dynamics.

- Outliers: A few extreme data points can inflate the estimated variability.

- Incorrect model: The fundamental PK/PD structure may be wrong.

- Sparse data: Too few data points per individual can lead to poorly identifiable error parameters.

Q4: Why is consistency between estimation and simulation methods for the error model so important?

A4: As highlighted in research, using a different method for simulation than was used for estimation can lead to biased simulations that do not accurately reflect the original data or model [5] [6]. For example, if a model was estimated using the VAR method (SD = sqrt(a² + (b*f)²)), but simulations are run using the SD method (SD = a + b*f), the simulated variability around predictions will be incorrect. This is critical for clinical trial simulations used to inform study design or dosing decisions.

Visualization: Error Model Selection and Relationship

Error Model Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

This table lists key software tools and conceptual "reagents" essential for implementing and testing error models in pharmacometric research.

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Error Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM | Software | Industry-standard software for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling, offering flexible coding for all error model types [5] [6]. |

| Pumas/Julia | Software | Modern, high-performance modeling platform with explicit syntax for additive (Normal(μ, σ)), proportional (Normal(μ, μ*σ)), and combined error models [4]. |

| R/Python (ggplot2, Matplotlib) | Software | Critical for creating diagnostic plots (residuals vs. predictions, VPCs) to visually assess the appropriateness of the error model. |

| Monolix | Software | User-friendly GUI-based software that implements error model selection and diagnostics seamlessly. |

| SimBiology (MATLAB) | Software | Provides built-in error model options (constant, proportional, combined) for PK/PD model building [10]. |

| "Conditional Weighted Residuals" (CWRES) | Diagnostic Metric | The primary diagnostic for evaluating error model structure; patterns indicate misfit [2]. |

| Objective Function Value (OFV) | Diagnostic Metric | A statistical measure used for hypothesis testing between nested error models (e.g., combined vs. proportional). |

| Visual Predictive Check (VPC) | Diagnostic Tool | A graphical technique to simulate and compare model predictions with observed data, assessing the overall model, including error structure. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Combined Error Models

This support center addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing and interpreting combined (additive and proportional) error models in simulation studies, a core component of advanced pharmacokinetic and quantitative systems pharmacology research.

Issue: My model fit is acceptable, but simulations from the model parameters produce implausible or incorrect variability. What is wrong?

- Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of a methodology mismatch between estimation and simulation. The combined error model you used for parameter estimation (e.g., in NONMEM) may differ from the one implemented in your simulation tool [5].

- Solution: Audit your error model code across platforms. Crucially, you must ensure the simulation tool uses the exact same mathematical definition (VAR or SD) as used during parameter estimation. The parameter values for residual error are not interchangeable between the two methods [5].

Issue: How do I choose between the VAR and SD method for my analysis? The results differ.

- Diagnosis: Both methods are statistically valid but represent the combined error differently. The SD method will typically yield lower estimated parameter values for the residual error components (θprop, θadd) compared to the VAR method, while structural parameters (e.g., clearance, volume) remain largely unaffected [5].

- Solution: Use the objective function value (OFV) for model selection when comparing nested models. The method with the significantly better (lower) OFV provides a better fit to your specific data. Consistency within a research project is key [5].

Issue: I am implementing the combined error model in code. The VAR method is said to have three coding options. Are they equivalent?

- Diagnosis: Yes. The VAR method, which defines total error variance as

Var(total) = (θ_prop * F)^2 + θ_add^2, can be coded in different syntactic ways in software like NONMEM (e.g., usingY=F+ERR(1)with a suitable$ERRORblock definition). - Solution: Different codings of the VAR method yield identical results [5]. Choose the coding that is most transparent and error-proof for your specific model structure and team.

- Diagnosis: Yes. The VAR method, which defines total error variance as

Issue: When is it critical to use a combined error model instead of a simple additive or proportional one?

- Diagnosis: Use a combined model when the magnitude of residual error scales with the predicted value (F). This is common in pharmacokinetics where assay precision is a percentage at high concentrations but hits a floor at low concentrations.

- Solution: Test model fits graphically and statistically. Plot residuals (CWRES) vs. predictions (PRED) or observed values (DV). A "fan-shaped" pattern suggests a proportional component is needed. A combined model is justified when it significantly improves the OFV and residual plots over simpler models.

Issue: Can these error modeling concepts be applied outside of pharmacokinetics?

- Diagnosis: Absolutely. The framework of separating additive and proportional (multiplicative) error is universal in measurement science. For example, it has been successfully applied to improve the accuracy of Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) generated from LiDAR data, where both error types are present [13].

- Solution: Evaluate the nature of measurement error in your field. If your instrument or assay error has both a fixed baseline component and a component that scales with the signal magnitude, a combined error model is theoretically appropriate and may yield more accurate and precise estimates [13].

Comparative Analysis: VAR vs. SD Methodologies

The core distinction lies in how the proportional (εprop) and additive (εadd) error components are combined. Assume a model prediction F, a proportional error parameter θ<sub>prop</sub>, and an additive error parameter θ<sub>add</sub>.

Table 1: Foundational Comparison of Error Model Frameworks

| Aspect | Variance (VAR) Method | Standard Deviation (SD) Method |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Errors are statistically independent. Total variance is the sum of individual variances [5]. | Standard deviations of the components are summed directly [5]. |

| Mathematical Formulation | Var(Total) = Var(Prop.) + Var(Add.) = (θ_prop * F)² + θ_add² [5] |

SD(Total) = SD(Prop.) + SD(Add.) = (θ_prop * F) + θ_add [5] |

| Parameter Estimates | Yields higher values for θprop and θadd [5]. | Yields lower values for θprop and θadd [5]. |

| Impact on Other Parameters | Minimal effect on structural model parameters (e.g., clearance, volume) and their inter-individual variability [5]. | Minimal effect on structural model parameters (e.g., clearance, volume) and their inter-individual variability [5]. |

| Primary Use Case | Standard in pharmacometric software (NONMEM). Preferred when error components are assumed independent. | An alternative valid approach. May be used in custom simulation code or other fields. |

Table 2: Implications for Simulation & Dosing Regimen Design

| Research Phase | Implication of Using VAR Method | Implication of Using SD Method | Critical Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimation | Estimates specific to the VAR framework. | Estimates specific to the SD framework. | Never mix and match. Parameters from one method are invalid for the other. |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Simulated variability aligns with variance addition. | Simulated variability aligns with SD addition. | The simulation engine must implement the same method used for estimation to preserve the intended error structure [5]. |

| Predicting Extreme Values | Tails of the distribution are influenced by the quadratic term (F²). |

Tails of the distribution are influenced by the linear term (F). |

For safety-critical simulations (e.g., predicting Cmax), verify the chosen method's behavior in the extreme ranges of your predictions. |

| Protocol Development | Simulations for trial design must use the correct method to accurately predict PK variability and coverage. | Simulations for trial design must use the correct method to accurately predict PK variability and coverage. | Document the error model methodology (VAR/SD) in the statistical analysis plan and simulation protocols. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following protocol is adapted from seminal comparative studies of VAR and SD methods [5].

1. Objective: To compare the Variance (VAR) and Standard Deviation (SD) methods for specifying combined proportional and additive residual error models in a population pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis, evaluating their impact on parameter estimates and model performance.

2. Materials & Software:

- Dataset: PK concentration-time data from a published study (e.g., a drug with a wide range of observed concentrations).

- Software: NONMEM (version 7.4 or higher) with PsN or Pirana for workflow management.

- Supporting Tools: R (with

xpose,ggplot2packages) for diagnostics and visualization.

3. Methodology:

1. Base Model Development:

* Develop a structural PK model (e.g., 2-compartment IV) using only an additive error model.

* Estimate population parameters and inter-individual variability (IIV) on key parameters.

2. Combined Error Model Implementation:

* VAR Method: Code the error model in the $ERROR block such that the variance of the observation Y is given by:

VAR(Y) = (THETA(1)*F)2 + (THETA(2))2

where THETA(1) is θprop and THETA(2) is θadd.

* SD Method: Code the error model such that the standard deviation of Y is given by:

SD(Y) = THETA(1)*F + THETA(2)

This often requires a different coding approach in NONMEM, such as defining the error in the $PRED block or using a specific $SIGMA setup.

3. Model Estimation: Run the estimation for both methods (first-order conditional estimation with interaction, FOCE-I).

4. Model Comparison: Record the objective function value (OFV), parameter estimates (θprop, θadd, structural parameters, IIV), and standard errors for both runs.

5. Diagnostic Evaluation: Generate standard goodness-of-fit plots (observed vs. predicted, conditional weighted residuals vs. predicted/time) for both models.

6. Simulation Verification:

* Using the final parameter estimates from each method, simulate 1000 replicates of the original dataset using the same error model method.

* Compare the distribution of simulated concentrations against the original data to verify the error structure is correctly reproduced.

4. Expected Outcomes:

- The OFV for both combined models will be significantly better than the base additive error model.

- The θprop and θadd estimates from the SD method will be numerically lower than those from the VAR method [5].

- Estimates for structural parameters (e.g., CL, V) and their IIV will be nearly identical between the two methods [5].

- Goodness-of-fit plots will be similar and acceptable for both methods.

Visualization of Key Concepts

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Combined Error Model Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacometric Software | Core engine for non-linear mixed-effects modeling and simulation. | NONMEM, Monolix, or Phoenix NLME. Ensure you know how your software implements the combined error model by default (usually VAR). |

| Diagnostic & Visualization Package | Generates goodness-of-fit plots, conducts model diagnostics, and manages workflows. | R with xpose or Python with PharmPK. Essential for comparing VAR vs. SD model fits. |

| Clinical PK Dataset | The empirical substrate for model building and testing. | Should contain a wide range of concentrations. Public resources like the OECD PK Database or published data from papers [5] can be used for method testing. |

| Script Repository | Ensures reproducibility and prevents coding errors in complex model definitions. | Maintain separate, well-annotated script files for VAR and SD model code. Version control (e.g., Git) is highly recommended. |

| Simulation & Validation Template | Verifies that the estimated parameters correctly reproduce the observed error structure. | A pre-written script to perform the "Simulation Verification" step from the protocol above. This is a critical quality control step. |

| Digital Terrain Model (DTM) Data | For cross-disciplinary validation. Demonstrates application beyond pharmacology. | LiDAR-derived DTM data with known mixed error properties can be used to test the universality of the framework [13]. |

This technical support center provides resources for researchers navigating the critical challenge of error quantification and management in biomedical experiments. Accurate characterization of error is fundamental to robust simulation research, particularly when evaluating additive versus combined error models. These models form the basis for predicting variability in drug concentrations, biomarker levels, and treatment responses.

An additive error model assumes the error's magnitude is constant and independent of the measured value (e.g., ± 0.5 ng/mL regardless of concentration). In contrast, a combined error model incorporates both additive and multiplicative (proportional) components, where error scales with the size of the measurement (e.g., ± 0.5 ng/mL + 10% of the concentration) [14] [5]. Choosing the incorrect error structure can lead to biased parameter estimates, invalid statistical tests, and simulation outputs that poorly reflect reality [15] [7].

This guide addresses the three primary sources of uncertainty that conflate into residual error: Measurement Error, Model Misspecification, and Biological Variability. The following sections provide troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and methodologies to identify, quantify, and mitigate these errors within your research framework.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Dominant Source of Error in Your Dataset

Symptoms: High residual unexplained variability (RUV), poor model fit, parameter estimates with implausibly wide confidence intervals, or simulations that fail to replicate observed data ranges.

Diagnostic Procedure:

- Visualize Residuals: Plot conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) or absolute residuals against population predictions and against time.

- Pattern Analysis:

- Fan-shaped pattern (variance increases with predictions): Suggests proportional (multiplicative) error is dominant. An additive model is misspecified [7].

- Constant spread across all predictions: Suggests additive error may be sufficient.

- Systematic bias (residuals not centered around zero across predictions): Suggests model misspecification (e.g., wrong structural model, missing covariate).

- Outliers or heavy tails: Suggests potential biological variability not captured by the model or data corruption [7].

- Statistical Testing: Perform likelihood ratio tests (LRT) between nested error models (e.g., additive vs. combined). A significant drop in objective function value (OFV, e.g., >3.84 for 1 degree of freedom) favors the more complex model [5].

- External Verification: If possible, compare the precision of your assay (from validation studies) to the estimated residual error from the model. A significantly larger model-estimated error implies substantial biological variability or model misspecification.

Guide 2: Correcting for Measurement Error in Covariates

Problem: An independent variable (e.g., exposure biomarker, physiological parameter) is measured with error, causing attenuation bias—the estimated relationship with the dependent variable is biased toward zero [15].

Solutions:

- Regression Calibration: Use replicate measurements to estimate the measurement error variance and correct the parameter estimates [16].

- SIMEX (Simulation-Extrapolation): A simulation-based method that adds increasing levels of artificial measurement error to the data, observes the trend in parameter bias, and extrapolates back to the case of no measurement error [16].

- Error-in-Variables Models: Implement models that formally incorporate a measurement equation for the error-prone covariate [15]. This is the most statistically rigorous approach.

Diagram: Impact and Correction of Measurement Error in Covariates

Guide 3: Selecting and Validating a Residual Error Model

Workflow for PK/PD and Biomarker Data:

- Start Simple: Fit an additive error model (

Y = F + ε). - Assess Fit: Examine residual plots. If a fan pattern is evident, proceed.

- Fit a Proportional Model: Fit a multiplicative error model (e.g.,

Y = F + F * εor constant coefficient of variation). - Fit a Combined Model: Fit a combined error model (e.g.,

Y = F + sqrt(θ₁² + θ₂²*F²) * ε) [5] [7]. - Compare Objectively: Use LRT to compare nested models (e.g., additive vs. combined). Use OFV/Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to compare non-nested models.

- Consider Advanced Structures: If skewness or heavy tails remain, investigate:

- Predictive Check: Perform a visual predictive check (VPC) or numerical prediction-corrected VPC (pcVPC) using the final model. The simulations should adequately reproduce the spread and central tendency of the observed data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I definitively use a combined error model over a simpler one? A: A combined error model is strongly indicated when the standard deviation of the residuals shows a linear relationship with the model predictions [5]. This is common in pharmacokinetics where assay precision may be relative (proportional) at high concentrations, but a floor of absolute noise (additive) exists at low concentrations. Always validate with diagnostic plots and statistical tests [7].

Q2: How does biological variability differentiate from measurement error in a model? A: Biological variability (e.g., inter-individual, intra-individual) is "true" variation in the biological process and is typically modeled as random effects on parameters (e.g., clearance varies across subjects). Measurement error is noise introduced by the analytical method. In a model, biological variability is explained by the random effects structure, while measurement error is part of the unexplained residual variability [2]. A well-specified model partitions variability correctly.

Q3: My model diagnostics suggest misspecification. What are the systematic steps to resolve this? A: Follow this hierarchy: 1) Review the structural model: Is the fundamental pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship wrong? 2) Check covariates: Have you included all relevant physiological (e.g., weight, renal function) or pathophysiological factors? 3) Examine the random effects structure: Are you allowing the right parameters to vary between individuals? 4) Finally, refine the residual error model: The error model should be addressed only after the structural model and covariates are justified [2] [7].

Q4: In simulation research for trial design, why is the choice of error model critical? A: The error model directly determines the simulated variability around concentration-time or response-time profiles. Using an additive model when the true error is combined will under-predict variability at high concentrations/effects and over-predict it at low levels. This can lead to incorrect sample size calculations, biased estimates of probability of target attainment, and ultimately, failed clinical trials [5]. The simulation tool must use the same error model structure as the analysis used for parameter estimation.

Q5: How can I design an experiment to specifically quantify measurement error vs. biological variability? A: Incorporate a reliability study within your experimental design [17]. For example:

- To isolate assay measurement error, analyze multiple technical replicates from the same biological sample.

- To quantify biological variability, take measurements from the same subject under stable, repeated conditions (e.g., same time of day, fasting state). The variance components can then be partitioned using a mixed model, where the residual variance primarily represents measurement error, and the between-subject/inter-occasion variance represents biological variability [17] [18].

Detailed Methodologies & Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Combined Error Model in Pharmacometric Software (e.g., NONMEM)

This protocol outlines steps to code and estimate a combined proportional and additive residual error model, a common task in population PK/PD analysis [5].

1. Objective: To characterize residual unexplained variability (RUV) using a model where the variance is the sum of proportional and additive components.

2. Software: NONMEM (version ≥ 7.4), PsN, or similar.

3. Mathematical Model:

The observed value (Y) is related to the individual model prediction (IPRED) by:

Y = IPRED + IPRED · ε₁ + ε₂

where ε₁ and ε₂ are assumed to be independent, normally distributed random variables with mean 0 and variances σ₁² and σ₂², respectively.

Therefore, the conditional variance of Y is: Var(Y | IPRED) = (IPRED · σ₁)² + σ₂² [5].

4. NONMEM Control Stream Code Snippet ($ERROR block):

5. Estimation:

- Use the First-Order Conditional Estimation method with interaction (FOCE-I).

- Initial estimates for

σ₁andσ₂can be informed from assay validation data (CV% and lower limit of quantification).

6. Diagnostic Steps:

- Plot conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) vs. population predictions (PRED) and vs. time.

- Perform a visual predictive check (VPC) stratified by dose or other relevant factors to assess if the model accurately simulates the spread of the data across the prediction range.

Protocol: Conducting a Reliability Study for a Continuous Biomarker

This protocol is adapted from guidelines for assessing measurement properties [17].

1. Define the Aim: To quantify the contributions of different sources of variation (e.g., between-rater, between-device, within-subject) to the total measurement variance of a continuous biomarker.

2. Design: A repeated-measures study in stable patients/participants. The design depends on the sources you wish to investigate.

- Example Design (Rater & Day Variability): Each of

nsubjects is measured by each ofkraters on each ofddays. The order should be randomized.

3. Data Collection:

- Subjects: Recruit a representative sample (

n > 15) with a range of biomarker values relevant to the intended use. - Stability: Ensure the underlying biological state is stable (e.g., fasting, same time of day).

- Blinding: Raters should be blinded to each other's scores and to previous measurements.

4. Statistical Analysis using a Linear Mixed Model:

- Fit a model where the biomarker measurement is the dependent variable.

- Fixed Effect: Include an intercept (the overall mean).

- Random Effects: Include random intercepts for

Subject,Rater, andDay, and potentially their interactions (e.g.,Subject-by-Ratervariance). The residual variance then represents pure measurement error. - Model Equation (simplified):

Y_{ijk} = μ + S_i + R_j + D_k + ε_{ijk}whereS_i ~ N(0, τ²),R_j ~ N(0, ρ²),D_k ~ N(0, δ²),ε_{ijk} ~ N(0, σ²).

5. Output & Interpretation:

- Extract the variance components (

τ²,ρ²,δ²,σ²). - Calculate the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for agreement. For example, the ICC for a single rater on a single day might be:

ICC = τ² / (τ² + ρ² + δ² + σ²). - Calculate the Standard Error of Measurement (SEM):

SEM = sqrt(ρ² + δ² + σ²). This is an absolute index of reliability, expressed in the biomarker's units [17].

Diagram: Reliability Study Workflow for Variance Component Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of Key Error Model Structures in Pharmacometric Modeling

| Error Model | Mathematical Form | Variance | Primary Use Case | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive | Y = F + ε |

σ² (constant) |

Assay error is constant across all magnitudes. Homoscedastic data. | Simple, stable estimation. | Unsuitable for data where error scales with the measurement [14]. |

| Proportional (Multiplicative) | Y = F + F·ε |

(F·σ)² |

Constant coefficient of variation (CV%). Common in PK. | Realistic for many analytical methods. Variance scales with prediction. | Can overweight low concentrations; fails at predictions near zero [2] [7]. |

| Combined (Additive + Proportional) | Y = F + F·ε₁ + ε₂ |

(F·σ₁)² + σ₂² |

Data with both a constant CV% component and a floor of absolute noise. Most realistic for PK. | Flexible, captures complex error structures. Good for simulation. | More parameters to estimate. Can be overparameterized with sparse data [5] [7]. |

| Power | Y = F + F^ζ·ε |

(F^ζ·σ)² |

Heteroscedasticity where the power relationship is not linear (exponent ζ ≠ 1). | Highly flexible for describing variance trends. | Exponent ζ can be difficult to estimate precisely [7]. |

Table 2: Impact of Ignoring Measurement Error in Covariates: Simulation Results Summary Based on principles from [16] [15]

| Scenario | True Slope (β) | Naive Estimate (Ignoring Error) | Bias (%) | Impact on Type I Error Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Measurement Error (CV~5%) | 1.0 | ~0.99 | ~1% | Slightly inflated (>5%) |

| Moderate Measurement Error (CV~20%) | 1.0 | ~0.96 | ~4% | Moderately inflated (e.g., 10%) |

| High Measurement Error (CV~40%) | 1.0 | ~0.86 | ~14% | Severely inflated (e.g., 25%) |

| Null Effect (β=0) with High Error | 0.0 | ~0.0 (but highly variable) | N/A | False positive rate uncontrolled. Standard tests invalid [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Error Assessment Studies

| Item / Category | Function / Purpose | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides a "true value" for calibrating instruments and assessing systematic measurement error (accuracy). | Certified plasma spiked with known concentrations of a drug metabolite for LC-MS/MS assay validation [14]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Monitors precision (random measurement error) across assay runs. High, mid, and low concentration QCs assess stability of error over range. | Prepared pools of subject samples with characterized biomarker levels, run in duplicate with each assay batch. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Corrects for variability in sample preparation and instrument response in mass spectrometry, reducing technical measurement error. | ¹³C- or ²H-labeled analog of the target analyte added to every sample prior to processing. |

| Biobanked Samples from Stable Subjects | Enables reliability studies to partition biological vs. measurement variance. Samples from individuals in a steady state are critical [17]. | Serum aliquots from healthy volunteers drawn at the same time on three consecutive days for a cortisol variability study. |

| Software for Mixed-Effects Modeling | Tool to statistically decompose variance into components (biological, measurement, etc.) and fit combined error models. | NONMEM, R (nlme, lme4, brms packages), SAS PROC NLMIXED [5] [18]. |

| Simulation & Estimation Software | Used to perform visual predictive checks (VPCs) and power analyses for study design, testing the impact of different error models. | R, MATLAB, PsN, Simulx. |

The Role of Error Models in Simulation and Predictive Accuracy

In computational science and quantitative drug development, the choice of error model is a foundational decision that directly determines the reliability of simulations and the accuracy of predictions. An error model mathematically characterizes the uncertainty, noise, and residual variation within data and systems. The ongoing research debate between additive error models and more complex combined (mixed additive and multiplicative) error models is central to advancing predictive science [13] [19]. While additive models assume noise is constant regardless of the signal size, combined models recognize that error often scales with the measured value, offering a more realistic representation of many biological and physical phenomena [13]. This technical support center is framed within this critical thesis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with targeted guidance to troubleshoot simulation issues, which often stem from inappropriate error model specification. Implementing a correctly specified error model is not merely a statistical formality; it is essential for generating trustworthy simulations that can inform dose selection, clinical trial design, and regulatory decisions [20] [21].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common technical challenges encountered when building and executing simulations in pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD), systems pharmacology, and related computational fields.

A. General Troubleshooting & Model Configuration

Q1: My simulation fails to start or terminates immediately with a configuration error. What are the first steps to diagnose this?

- Context & Thesis Link: This fundamental issue can occur in any simulation environment (e.g., Simulink, ANSYS, AnyLogic) and halts progress before error model performance can even be assessed. Incorrect physical or logical configuration violates the solver's basic assumptions.

- Solution:

- Verify Solver and Reference Blocks: Ensure every distinct physical domain in your model has the required global configuration block (e.g., one Solver Configuration block per diagram in Simscape). Check that all electrical, mechanical, or hydraulic circuits are properly grounded with the correct reference blocks (e.g., Electrical Reference) [22].

- Inspect Connections for Physical Impossibility: Look for illegal configurations such as two ideal velocity sources (across-variable sources) connected in parallel or two ideal force sources (through-variable sources) connected in series. These create unsolvable loops [22].

- Check for Over-Specification: Ensure you do not have multiple global property blocks (e.g., two

Gas Propertiesblocks) in the same fluid circuit, which confuses the solver [22]. - Simplify and Rebuild: Adopt an incremental modeling strategy. Start with a highly simplified, idealized version of your system, verify it runs, and then gradually add complexity (e.g., friction, compliance, detailed error structures) [22].

Q2: I receive a "Degree of Freedom (DOF) Limit Exceeded" or "Rigid Body Motion" error in my finite element analysis. How do I resolve it?

- Context & Thesis Link: In mechanical and biomechanical simulations, this error indicates the model is not fully constrained and can move freely, preventing a static solution. This is analogous to a statistical model that is not identifiable due to insufficient data or over-parameterization.

- Solution:

- Check All Constraints: Verify that every part in your assembly has sufficient external supports (fixtures) to prevent translation and rotation. Ensure parts are either directly constrained or connected via contacts/joints to parts that are constrained [23].

- Validate Contacts: If using nonlinear contacts (e.g., frictional) to hold the model together, use the Contact Tool to ensure they are initially closed. Be aware that frictionless contacts do not prevent separation [23].

- Run a Modal Analysis: As a diagnostic tool, run a linear modal analysis with the same supports. Look for modes at or near 0 Hz—the animation will clearly show which parts are moving without deformation, identifying the under-constrained components [23].

B. Numerical & Solver Instability Issues

Q3: The solver reports convergence failures during transient simulation or "unconverged solution." What does this mean and how can I fix it?

- Context & Thesis Link: Convergence failures are hallmarks of numerical instability, often triggered by high nonlinearity or discontinuities. In PK-PD modeling, this can arise from sharp, saturating drug-receptor binding kinetics or on/off switches in systems biology models. A robust error model must account for the noise structure around these nonlinear processes.

- Solution:

- Activate Solver Diagnostics: Enable the Newton-Raphson Residual plot in your solver settings. After a failed run, this plot will highlight geographic "hotspots" in the model (colored red) where the numerical residuals are highest, often pinpointing problematic contacts or elements [23].

- Review Nonlinearities: The primary culprits are material nonlinearity (e.g., plasticity), nonlinear contact, and large deformations. If diagnostics point to a contact region, try mesh refinement, reducing contact stiffness, or using displacement-controlled loading instead of force-controlled [23].

- Troubleshoot Systematically: Remove all nonlinearities and verify the model solves linearly. Then, reintroduce nonlinearities one by one to isolate the component causing the failure [23].

- Adjust Solver Tolerances: For iterative parameter estimation in mixed error models, algorithms like bias-corrected Weighted Least Squares (bcWLS) have been developed to handle the correlated structure of combined errors and improve convergence [19]. Ensure you are using an appropriate estimation method for your error model type.

Q4: My process or systems pharmacology model suffers from numerical oscillations or stiffness, leading to very small time steps and failed runs.

- Context & Thesis Link: Stiff systems have dynamics operating on vastly different time scales (e.g., rapid receptor binding vs. slow disease progression). Mis-specified error models can exacerbate stiffness by introducing ill-conditioned matrices.

- Solution:

- Review Model Components: Check for parameters with extreme value ranges or events that create sudden, large changes in state variables (discontinuities). These are common in pharmacology (e.g., bolus doses, target saturation).

- Adjust Solver Settings: Tighten the relative tolerance or specify an absolute tolerance for state variables. In some tools, you can also increase the number of allowed consecutive minimum step size violations before failure [22].

- Add Parasitic Elements: In physical system models, adding small damping or capacitance can mitigate stiffness arising from dependent dynamic states (e.g., idealized inertias connected by rigid constraints) [22].

- Re-evaluate Error Structure: For parameter estimation, consider if a correlated observation mixed error model is appropriate. Recent methods account for correlation between additive and multiplicative error components, which can stabilize estimation and improve predictive accuracy for complex systems [19].

C. Data, Parameter, & Model Specification Errors

Q5: How do I choose the correct thermodynamic model or property package for my chemical process or physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) simulation?

- Context & Thesis Link: The property package defines the "physics" of the simulation, governing phase equilibria, solubilities, and reaction rates. An incorrect choice is a fundamental model misspecification error, leading to systematic prediction bias that no statistical error model can correct.

- Solution:

- Consult Literature & Software Guides: Research the standard property packages for your specific chemical systems (e.g., NRTL for electrolytes, Peng-Robinson for hydrocarbons). For PBPK, ensure tissue partition coefficients (Kp) are predicted or measured using appropriate methods [20] [24].

- Validate with Known Data: Before simulating novel conditions, test the model's ability to reproduce simple, well-established experimental data (e.g., vapor-liquid equilibrium for binaries, blood concentration-time profiles for a reference compound).

- Ensure Input Consistency: Double-check that all component properties, stream compositions, and operating conditions are physically realistic and consistent with the chosen property package's requirements [24].

Q6: I encounter "compile-time" or "runtime" errors related to variable names, types, or logic in my agent-based or discrete-event simulation.

- Context & Thesis Link: These are syntax and logical errors in the model's code or structure. They prevent the model from being executed and are distinct from numerical errors arising from the simulated processes. Clean code is a prerequisite for testing scientific hypotheses about error structures.

- Solution:

- Understand Error Messages: Carefully read the error in the Problems or Console window. Common compile-time errors include "cannot be resolved" (misspelled object name), "type mismatch" (assigning a

doubleto aboolean), and "syntax error" (missing semicolon or bracket) [25]. - Use Code Completion: Leverage the IDE's code completion feature (

Ctrl+Space). If a known variable doesn't appear, check that its containing object is not set to "Ignore" in the properties [25]. - Check Agent Flow Logic: For runtime errors like "Agent cannot leave port," ensure all pathways in your flowchart are connected, and blocks like

QueueorServicehave adequate capacity or a "Pull" protocol to avoid deadlock [25].

- Understand Error Messages: Carefully read the error in the Problems or Console window. Common compile-time errors include "cannot be resolved" (misspelled object name), "type mismatch" (assigning a

Q7: How can I ensure my machine learning model for biomarker discovery reliably identifies true feature interactions and controls for false discoveries?

- Context & Thesis Link: In omics and high-dimensional data, ML models can detect complex, non-additive interactions (e.g., synergistic gene pairs). Traditional interpretability methods lack robust error control, risking spurious scientific claims. This relates to the thesis by emphasizing the need for error-controlled discovery within predictive modeling.

- Solution: Implement the Diamond framework or similar methodologies designed for error-controlled interaction discovery [26].

- Generate Model-X Knockoffs: Create a set of "dummy" features (

X_tilde) that perfectly mimic the correlation structure of your original features (X) but are conditionally independent of the response variable (Y). - Train Model on Augmented Data: Concatenate

XandX_tildeand train your chosen ML model (DNN, random forest, etc.) on this extended dataset. - Distill Non-Additive Effects: Use Diamond's distillation procedure to calculate interaction importance scores that isolate true synergistic effects, not just additive combinations of main effects.

- Apply False Discovery Rate (FDR) Control: Use the knockoff copies as a calibrated control to select a threshold for discovered interactions, ensuring the expected proportion of false discoveries remains below a target level (e.g., 5%) [26].

- Generate Model-X Knockoffs: Create a set of "dummy" features (

Data & Evidence Tables

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Additive vs. Mixed Error Models in LiDAR Data Processing

This table summarizes key findings from a 2025 study applying different error models to generate Digital Terrain Models (DTM), highlighting the superior accuracy of the combined error approach [13].

| Error Model Type | Theoretical Basis | Application Case | Key Finding | Implication for Predictive Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive Error Model | Assumes random error is constant, independent of signal magnitude. | LiDAR DTM generation; treating all error as additive. | Provided lower accuracy in both DTM fitting and interpolation compared to mixed model. | Can lead to systematic bias and under/over-estimation in predictions, especially where measurement error scales with value. |

| Mixed Additive & Multiplicative Error Model | Accounts for both constant error and error that scales proportionally with the observed value. | LiDAR DTM generation; acknowledging both error types present in the data. | Delivered higher accuracy in terrain modeling. Theoretical framework was more appropriate for the data [13]. | Enhances prediction reliability by correctly characterizing the underlying noise structure, leading to more accurate uncertainty quantification. |

Table 2: Impact of Modeling & Simulation (M&S) on Clinical Trial Efficiency

This table quantifies the tangible benefits of robust modeling in drug development, where accurate error models within simulations lead to more efficient trial designs [27] [21].

| Therapeutic Area | Modeling Approach Adapted | Efficiencies Gained vs. Historical Approach | Key Metric Improved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Model-based dose-response, adaptive design, omitting a trial phase. | ~95% fewer patients in Phase 3; Total development time reduced by ~2 years. | Patient burden, Cost, Time-to-market [27]. |

| Oncology (Multiple Cancers) | Integrative modeling to inform design. | ~90% fewer patients in Phase 3; ~75% reduction in trial completion time (~3+ years saved). | Patient burden, Time-to-market [27]. |

| Renal Impairment Dosing | Population PK modeling using pooled Phase 2/3 data instead of a dedicated clinical pharmacology study. | Avoids a standalone clinical study. | Cost, Development Timeline [21]. |

| QTc Prolongation Risk | Concentration-QT (C-QT) analysis from early-phase data instead of a Thorough QT (TQT) study. | Avoids a costly, dedicated TQT study. | Cost, Resource Allocation [21]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Applying a Mixed Additive and Multiplicative Error Model to LiDAR Data for DTM Generation

This protocol is based on the methodology described in the 2025 study comparing error models [13].

- Objective: To generate a high-accuracy Digital Terrain Model (DTM) from LiDAR point cloud data by correctly characterizing and applying a mixed additive and multiplicative random error model.

- Materials & Data:

- Raw LiDAR point cloud data for the area of interest.

- Software with geospatial statistical analysis and adjustment capabilities (e.g., custom MATLAB/Python code implementing the models from [13] or specialized surveying software).

- Ground control points (GCPs) with known, high-precision coordinates for validation.

- Procedure:

a. Data Pre-processing: Filter the LiDAR point cloud to classify ground points from vegetation and buildings.

b. Error Model Formulation:

* Define the mixed error model mathematically. A common form is:

y = f(β) ⊙ (1 + ε_m) + ε_a, whereyis the observation vector,f(β)is the true signal function,⊙denotes element-wise multiplication,ε_mis the vector of multiplicative random errors, andε_ais the vector of additive random errors [19]. * Specify the stochastic properties (mean, variance, correlation) ofε_mandε_a. In advanced applications, consider methods that account for correlation betweenε_mandε_a[19]. c. Parameter Estimation: Use an appropriate adjustment algorithm (e.g., bias-corrected Weighted Least Squares - bcWLS) to solve for the unknown terrain parameters (β) while accounting for the mixed error structure [13] [19]. d. Interpolation & DTM Creation: Interpolate the adjusted ground points to create a continuous raster DTM surface. e. Validation: Compare the generated DTM against the independent GCPs. Calculate accuracy metrics (e.g., Root Mean Square Error - RMSE). f. Comparison (Control): Repeat steps (b-d) using a traditional additive error model (treatingε_mas zero) on the same dataset. - Analysis: Statistically compare the validation RMSE from the mixed error model DTM and the additive error model DTM. The mixed model is expected to yield a significantly lower RMSE, confirming its higher predictive accuracy for the physical measurement system [13].

Protocol 2: Error-Controlled Discovery of Non-Additive Feature Interactions in ML Models (Diamond Method)

This protocol outlines the core workflow of the Diamond method for robust scientific discovery from machine learning models [26].

- Objective: To discover biologically relevant, non-additive feature interactions (e.g., gene-gene synergies) from a trained ML model while controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR).

- Materials & Data:

- High-dimensional dataset (

X,Y) (e.g., gene expression matrix and a phenotypic response). - Computational environment for machine learning (Python/R).

- Implementation of the Diamond framework or the model-X knockoffs package.

- High-dimensional dataset (

- Procedure:

a. Generate Knockoffs: Create a knockoff copy

~Xof your feature matrixX. The knockoffs must satisfy: (1)(~X, X)has the same joint distribution as(X, ~X), and (2)~Xis independent of the responseYgivenX[26]. b. Train Model on Augmented Set: Concatenate the original and knockoff features to form[X, ~X]. Train your chosen ML model (e.g., neural network, gradient boosting) on this augmented dataset to predictY. c. Compute Interaction Statistics: For every candidate feature pair (including original-original and original-knockoff pairs), use an interaction importance measure (e.g., integrated Hessians, split scores in trees) on the trained model to obtain a scoreW. d. Distill Non-Additive Effects: Apply Diamond's distillation procedure to the importance scoresWto filter out additive effects and obtain purified statisticsTthat represent only non-additive interaction strength [26]. e. Apply FDR Control Threshold: For a target FDR levelq(e.g., 0.10), calculate the thresholdτ = min{t > 0: (#{T_knockoff ≤ -t} / #{T_original ≥ t}) ≤ q}. Discover all original feature pairs whose purified statisticT_original ≥ τ[26]. - Analysis: The final output is a list of discovered feature interactions with the guarantee that the expected proportion of false discoveries among them is at most

q. These interactions can be prioritized for experimental validation.

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational tools and data components for conducting simulation research with a focus on error model specification.

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Error Model Research |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling & Simulation Software | NONMEM, Monolix, Simulink/Simscape, Ansys, AnyLogic, R/Python (with mrgsolve, Simpy, FEniCS). |

Provides the environment to implement the structural system model (PK-PD, mechanical, process) and integrate different stochastic error models for simulation and parameter estimation. |

| Statistical Computing Packages | R (nlme, lme4, brms), Python (statsmodels, PyMC, TensorFlow Probability), SAS (NLMIXED). |

Offers algorithms for fitting complex error structures (mixed-effects, heteroscedastic, correlated errors) and performing uncertainty quantification (e.g., bootstrapping, Bayesian inference). |

| Specialized Error Model Algorithms | Bias-Corrected Weighted Least Squares (bcWLS), Model-X Knockoffs implementation, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) samplers. | Directly implements advanced solutions for specific error model challenges: bcWLS for mixed additive/multiplicative errors [19], Knockoffs for FDR control in feature selection [26], HMC for efficient Bayesian fitting of high-dimensional models. |

| Benchmark & Validation Datasets | Public clinical trial data (e.g., FDA PKSamples), LiDAR point cloud benchmarks, physicochemical property databases (e.g., NIST). | Serves as ground truth to test the predictive accuracy of different error models. Used for method comparison and validation, as in the LiDAR DTM study [13]. |

| Sensitivity & Uncertainty Analysis Tools | Sobol indices calculation, Morris method screening, Plots (e.g., prediction-corrected visual predictive checks - pcVPC). | Diagnoses the influence of model components (including error parameters) on output uncertainty and evaluates how well the model's predicted variability matches real-world observation variability. |

Practical Implementation: Coding, Simulation, and Case Studies

In population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) modeling, accurately characterizing residual unexplained variability (RUV) is critical for developing reliable models that inform drug development decisions. The residual error model accounts for the discrepancy between individual model predictions and observed concentrations, arising from assay error, model misspecification, and other unexplained sources [28]. A combined error model, which incorporates both proportional and additive components, is frequently preferred as it can flexibly describe error structures that change over the concentration range [6].

The implementation of this combined model in NONMEM is not standardized, primarily revolving around two distinct methods: VAR and SD [6]. The choice between them has practical implications for parameter estimation and, crucially, for the subsequent use of the model in simulation tasks. This technical support center is designed within the broader research context of evaluating additive versus combined error models through simulation. It provides targeted guidance to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on correctly coding, troubleshooting, and applying these methods.

Comparison of VAR and SD Methods

The fundamental difference between the VAR and SD methods lies in how the proportional and additive components are combined to define the total residual error.

| Feature | VAR Method | SD Method |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Assumption | Variance of total error is the sum of independent proportional and additive variances [6]. | Standard deviation of total error is the sum of the proportional and additive standard deviations [6]. |

| Mathematical Form | Var(RUV) = (θ₁*IPRED)² + (θ₂)² |

SD(RUV) = θ₁*IPRED + θ₂ |

| Parameter Interpretation | θ₁ (dimensionless) and θ₂ (concentration units) scale the variances. | θ₁ (dimensionless) and θ₂ (concentration units) scale the standard deviations. |

| Typical Impact on Estimates | Generally yields higher estimates for the residual error parameters (θ₁, θ₂) [6]. | Yields lower estimates for θ₁ and θ₂ compared to the VAR method [6]. |

| Impact on Structural Parameters | Negligible effect on structural parameters (e.g., CL, V) and their inter-individual variability [6]. | Negligible effect on structural parameters (e.g., CL, V) and their inter-individual variability [6]. |

| Critical Requirement for Simulation | The simulation tool must use the same method (VAR or SD) as was used during model estimation to ensure correct replication of variability [6]. | The simulation tool must use the same method (VAR or SD) as was used during model estimation to ensure correct replication of variability [6]. |

Decision Guidance: The choice between methods can be based on statistical criteria like the objective function value (OFV), with a lower OFV indicating a better fit [6]. Some automated PopPK modeling frameworks employ penalty functions that balance model fit with biological plausibility, which can guide error model selection as part of a larger model structure search [29].

Implementation Guide for NONMEM

Coding the VAR Method

The VAR method assumes the total variance is the sum of the independent proportional and additive variances. It can be implemented in the $ERROR or $PRED block. The following are three valid, equivalent codings [6].

Option A: Explicit Variance

(This is the most direct translation of the mathematical formula.)

Option B: Separate EPS for Each Component

(Uses two EPS elements but fixes their variances to 1, as scaling is handled by THETA.)

Option C: Using ERR() Function (Alternative)

Coding the SD Method

The SD method assumes the total standard deviation is the sum of the proportional and additive standard deviations. The coding is more straightforward [6].

In this code, THETA(1) is the proportional coefficient and THETA(2) is the additive standard deviation term. Note that THETA(2) here is not directly comparable in magnitude to the THETA(2) estimated using the VAR method [6].

Essential Implementation Checklist

- Initial Estimates: Provide sensible initial estimates for

THETA(1)(e.g., 0.1 for 10% proportional error) andTHETA(2)(near the assay error level) in$THETA. - Bounds: Use boundaries (e.g.,

(0, 0.1, 1)for a proportional term) to keep estimates positive and plausible. - Documentation: Clearly comment in the control stream whether the VAR or SD method is used.

- Simulation Alignment: Verify that any downstream simulation script (e.g., in

$SIMULATION) matches the chosen method exactly.

Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses common errors and instability issues encountered when implementing error models in NONMEM.

Data and Syntax Errors

ITEM IS NOT A NUMBER: This commonDATA ERRORindicates NONMEM encountered a non-numeric value. Ensure all cells are numbers; convert categorical covariates (e.g., "MALE") to numeric codes (e.g., 1). In R, usena="."when writing the dataset to represent missing values [30].TIME DATA ITEM IS LESS THAN PREVIOUS TIME: Time must be non-decreasing within each individual. Sort your dataset byIDand thenTIME[30].OBSERVATION EVENT RECORD MAY NOT SPECIFY DOSING INFORMATION: This occurs when a record hasEVID=0(observation) but a non-zeroAMT(amount). EnsureEVID=0for observations andEVID=1for dosing records [30].$ERROR syntax error: Check for typos or incorrect use of keywords like(ONLY OBS). The correct syntax is(ONLY OBSERVATIONS)[31].

Model Stability and Estimation Problems

Model instability often stems from a mismatch between model complexity and data information content [28].

- Symptoms: Failure to converge, absence of standard errors, different estimates from different initial values, or biologically unreasonable parameters [28].

- Diagnosis Tool: Examine the R matrix in the NONMEM output. A singular R matrix indicates high correlation between parameters and potential overparameterization relative to the data [28].

- Action: If the model is overparameterized, simplify it (e.g., remove an error component if it is estimated near zero with high uncertainty). Alternatively, consider if the data is insufficient to inform a complex combined error model; an additive or proportional model might be more stable.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose between the VAR and SD method for my analysis? A: The choice is primarily statistical. Run your model using both methods and compare the objective function value (OFV). A decrease of more than 3.84 points (for 0 degrees of freedom) suggests a significantly better fit. Also, evaluate diagnostic plots (e.g., CWRES vs. PRED, CWRES vs. TIME). The method yielding a lower OFV and more randomly scattered residuals is preferred [6]. For consistency in a research thesis comparing error models, apply both methods systematically across all scenarios.

Q2: My combined error model won't converge. What should I try? A: Follow a systematic troubleshooting approach [28]:

- Simplify: Start with a simple proportional or additive error model. Ensure it converges.

- Sequential Addition: Fix the parameters of the simple model and add the second error component with a small initial estimate. Then, try estimating all parameters.

- Check Boundaries: Ensure your initial estimates and boundaries for

THETAare realistic. - Data Review: Confirm your data can support a combined structure. Very low or high concentration ranges might only inform one component.

Q3: Why is it critical to use the same error method for simulation as for estimation? A: The VAR and SD methods make different statistical assumptions about how variability scales. If you estimate a model using the VAR method but simulate using the SD method (or vice versa), you will incorrectly propagate residual variability. This leads to biased simulated concentration distributions and invalidates conclusions about dose-exposure relationships [6]. Always document the method used and configure your simulation script accordingly.

Q4: How do I handle concentrations below the limit of quantification (BLQ) or DV=0 in my dataset?