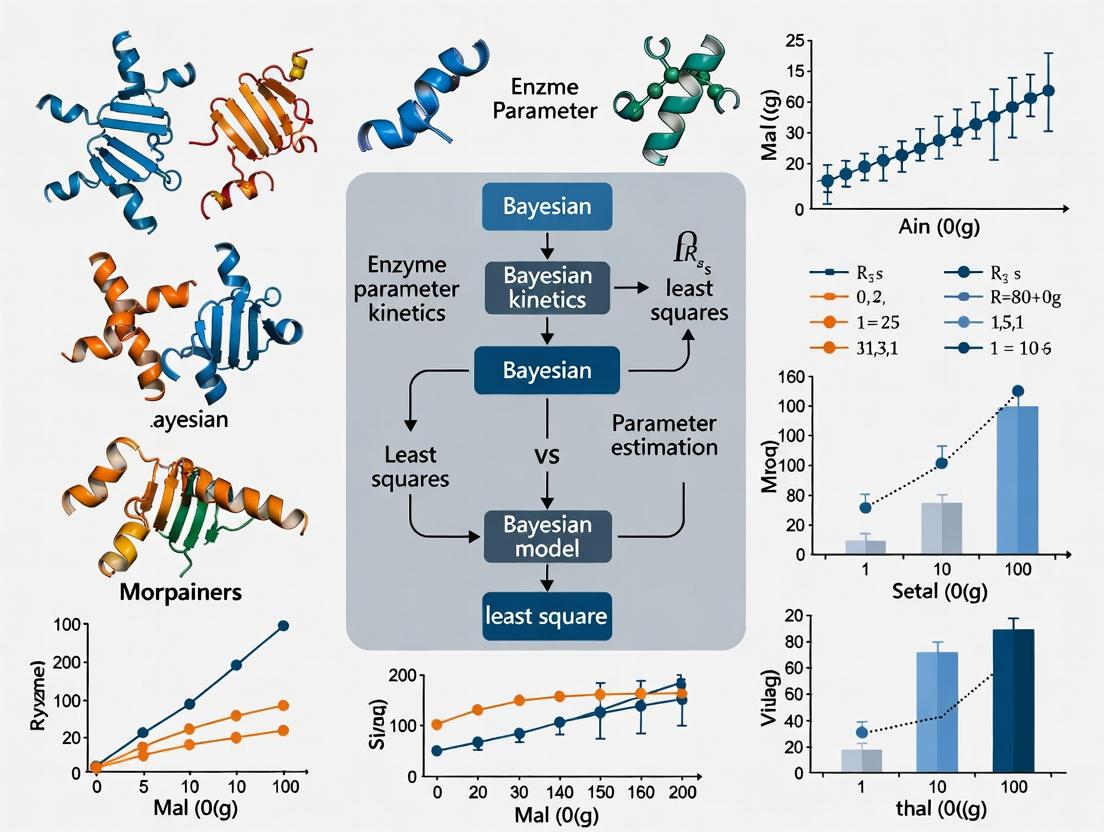

Bayesian vs Least Squares: A Modern Guide to Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation for Biomedical Research

Accurate estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., Vmax, KM, Ki) is fundamental to understanding biological mechanisms, predicting drug interactions, and guiding therapeutic development.

Bayesian vs Least Squares: A Modern Guide to Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurate estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., Vmax, KM, Ki) is fundamental to understanding biological mechanisms, predicting drug interactions, and guiding therapeutic development. This article provides a comprehensive, comparative analysis of two core statistical frameworks: the traditional least-squares regression and the increasingly prominent Bayesian inference. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, the scope ranges from foundational philosophical and statistical principles to practical methodological implementation, troubleshooting of common pitfalls, and rigorous validation strategies. We synthesize recent methodological advances to offer clear guidance on selecting and optimizing the appropriate estimation approach based on data quality, prior knowledge, and the specific goals of the kinetic study, ultimately aiming to enhance the reliability and efficiency of biomedical research.

Core Philosophies in Enzyme Kinetics: Understanding Least Squares Assumptions and Bayesian Probability

In biochemical research and drug development, the quantification of kinetic parameters from experimental data is foundational for understanding enzyme behavior, metabolic pathways, and drug mechanisms. The Michaelis-Menten equation, which describes the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction rate via parameters Vmax and Km, is a cornerstone of this analysis [1]. However, experimental data is invariably contaminated by measurement noise—unwanted deviations arising from instrumentation, biological variability, and environmental fluctuations [2]. This noise transforms parameter estimation from a straightforward calculation into a central challenge in systems biology and pharmacokinetics [3].

The choice of estimation methodology critically determines how this noise is processed and interpreted, directly impacting the reliability of the resulting parameters. Traditional least squares regression methods, including linearized transformations like the Lineweaver-Burk and Eadie-Hofstee plots, have been widely used for their simplicity [1]. In contrast, Bayesian inference approaches explicitly model uncertainty by incorporating prior knowledge and providing probability distributions for parameter estimates [4]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of these paradigms in the face of noisy data, providing researchers with a clear framework for selecting estimation methods that yield accurate, precise, and trustworthy parameters for predictive modeling and decision-making [5].

Methodological Comparison: Protocols and Data Generation

A rigorous comparison of estimation methods requires standardized, reproducible experimental and computational protocols. The following sections detail the key methodologies for generating noisy biochemical data and the subsequent parameter estimation processes.

Experimental Protocol: Simulating Noisy Enzyme Kinetic Data

A robust protocol for comparing estimation methods begins with the generation of simulated kinetic data where the "true" parameter values are known, allowing for direct accuracy assessment [1].

- Step 1: Define True Kinetic Parameters. Based on a known enzyme system (e.g., invertase with Vmax = 0.76 mM/min and Km = 16.7 mM), define the error-free Michaelis-Menten relationship [1].

- Step 2: Generate Error-Free Time-Course Data. Using numerical integration (e.g., with the

deSolvepackage in R), simulate substrate depletion over time for a set of initial substrate concentrations (e.g., 20.8, 41.6, 83, 166.7, 333 mM) [1]. - Step 3: Introduce Stochastic Noise. Corrupt the error-free data by adding random noise to create realistic "observed" data. Two primary error models are used:

- Additive Error Model:

[S]i = [S]pred + ε1i, where ε1 is a random variable from a normal distribution (mean=0, SD=0.04) [1]. - Combined Error Model:

[S]i = [S]pred + ε1i + [S]pred × ε2i, where ε2 is a random variable from a normal distribution (mean=0, SD=0.1). This model accounts for both fixed measurement noise and noise proportional to the signal magnitude [1].

- Additive Error Model:

- Step 4: Monte Carlo Replication. Repeat Step 3 to create a large number of replicate datasets (e.g., 1,000) for each error scenario. This ensemble approach allows for statistical analysis of estimator performance across many instances of random noise [1].

Parameter Estimation Protocols

From each noisy dataset, parameters are estimated using different methods. The workflow for preparing data and executing fits is critical for a fair comparison [1].

Data Preparation & Estimation Workflow

- Estimation Method 1 & 2: Linearization (LB, EH). Initial velocities (Vi) are calculated from the early linear phase of the substrate depletion curve for each concentration. For the Lineweaver-Burk (LB) method, the reciprocal data (1/Vi vs. 1/[S]) is fit with linear regression. For the Eadie-Hofstee (EH) method, Vi is plotted against Vi/[S] and fit linearly [1].

- Estimation Method 3 & 4: Direct Nonlinear Regression (NL, ND). The Michaelis-Menten equation is fit directly to velocity-substrate data using nonlinear least squares. The NL method uses the initial velocity (Vi). The ND method uses the average velocity (VND) calculated between adjacent time points and the corresponding average substrate concentration ([S]ND) [1].

- Estimation Method 5: Nonlinear Regression of Time-Course Data (NM). This most advanced method fits the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten ordinary differential equation (ODE) directly to the full time-series substrate concentration data, without the need for preliminary velocity calculation [1].

- Bayesian Estimation Protocol. In a separate framework, prior distributions (e.g., log-normal) are defined for Vmax and Km based on existing literature or biological plausibility. Using computational tools (e.g., Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling), the posterior distribution of the parameters is estimated, given the observed noisy data. This yields not just point estimates but full probability densities, quantifying uncertainty directly [4] [5].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The core of this guide is an objective comparison of how different estimation methods perform under controlled noisy conditions. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from simulation studies.

Table 1: Performance of Estimation Methods with Different Error Types [1]

| Estimation Method | Error Model | Relative Accuracy (Median % Bias) | Relative Precision (90% CI Width) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | Additive | High Bias (e.g., >15%) | Low Precision (Widest CI) | Linearizes data, distorts error structure. |

| Eadie-Hofstee (EH) | Additive | Moderate Bias | Moderate Precision | Less distortion than LB but still problematic. |

| Nonlinear (NL) | Additive | Low Bias | Good Precision | Direct fit, handles additive noise well. |

| Nonlinear (ND) | Additive | Low Bias | Good Precision | Uses more data points than NL. |

| Nonlinear (NM) | Additive | Lowest Bias | Best Precision | Uses all time-course data; most efficient. |

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | Combined | Very High Bias | Very Low Precision | Performs poorly with proportional error. |

| Nonlinear (NM) | Combined | Low Bias | Best Precision | Robust to complex error models. |

Table 2: Bayesian vs. Least Squares in Data-Limited Scenarios [4]

| Feature | Weighted Least Squares (Standard NL) | Bayesian Estimation | Subset-Selection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Find parameters minimizing sum of squared errors. | Update prior belief with data to obtain posterior distribution. | Fix inestimable parameters at prior values; estimate only key subset. |

| Handling Limited Data | Prone to overfitting; unreliable estimates. | Incorporates prior knowledge to stabilize estimates. | Reduces degrees of freedom to avoid overfitting. |

| Output | Point estimates & confidence intervals. | Full probability distributions (quantifies uncertainty). | Point estimates for a subset of parameters. |

| Reliance on Initial Guess | Moderate. Can converge to local minima. | High. Overly confident poor priors mislead. | Low. Less susceptible to poor initial guesses. |

| Computational Cost | Low to Moderate. | High (MCMC sampling). | Very High (requires estimability analysis). |

| Best Use Case | Abundant, high-quality data. | Prior knowledge is reliable and informative. | Model is large; prior knowledge is vague. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right computational and analytical tools is as critical as choosing the right biochemical reagents. This table details key solutions for performing robust uncertainty quantification in enzyme kinetics.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Uncertainty Quantification

| Item | Function in Estimation | Example/Platform | Relevance to Noise Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| NONMEM | Industry-standard software for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling. Used for advanced NM and NL methods [1]. | NONMEM (ICON plc) | Directly models complex error structures (additive, proportional, combined) in time-course data. |

| R with deSolve & nls | Open-source environment for simulation (ODE integration) and nonlinear least-squares fitting [1]. | R Statistical Language | Provides flexible framework for Monte Carlo simulation and custom estimator implementation. |

| Bayesian Inference Engine | Software for performing MCMC sampling to obtain posterior parameter distributions. | Stan, PyMC, JAGS | Quantifies parameter uncertainty directly and incorporates prior knowledge to combat noise [4] [5]. |

| Global Optimizer | Solver to find best-fit parameters in complex, multi-modal landscapes common in nonlinear models. | MEIGO, SciPy optimize | Avoids convergence to local minima, ensuring more accurate point estimates from noisy data [5]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Machine learning architecture for predicting molecular properties with inherent uncertainty quantification [6]. | Chemprop (D-MPNN) | Offers scalable UQ for high-dimensional design spaces (e.g., drug discovery), where noise is prevalent. |

| Conformal Prediction Toolkit | Framework for generating prediction sets with guaranteed coverage probabilities, regardless of data distribution. | crepes (Python) |

Provides distribution-free, rigorous uncertainty intervals for model predictions in the presence of noise [7]. |

Discussion: Implications for Research and Development

The comparative data leads to a clear conclusion: nonlinear regression methods, particularly those leveraging full time-course data (NM) or Bayesian inference, provide superior accuracy and precision in the presence of experimental noise compared to traditional linearization techniques [1]. The Least Squares (LB, EH) methods fail because their required data transformations distort the inherent noise structure, violating the fundamental assumptions of linear regression and producing biased estimates [1].

The choice between advanced least squares (e.g., NM) and Bayesian methods hinges on the data context and the research goal. When data is plentiful and the primary need is a classic point estimate, nonlinear least squares (NM) is robust and efficient. However, in the prevalent real-world scenario of sparse, noisy data—common in early drug discovery or patient-specific modeling—Bayesian estimation becomes indispensable [4]. It formally integrates prior knowledge, provides a complete picture of parameter uncertainty, and can prevent overfitting. This is critical for building trust in automated, high-throughput experimentation platforms where UQ must be a built-in feature [8].

Philosophical Divergence in Handling Noise

Emerging trends point toward hybrid frameworks that combine mechanistic models (like Michaelis-Menten ODEs) with machine learning surrogates to manage uncertainty in highly complex systems [3]. Furthermore, techniques like conformal prediction are rising to provide strict, distribution-free guarantees on prediction intervals, offering a new layer of reliability for AI-driven discovery in biochemistry [7]. For the practicing scientist, the imperative is to move beyond simplistic linearization. Embracing nonlinear regression as a baseline and adopting Bayesian or other advanced UQ methods for challenging data scenarios will lead to more reproducible, reliable, and actionable biochemical insights.

Classical Least Squares (CLS), also known as Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), is a foundational parameter estimation method that minimizes the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values [9]. In enzyme kinetics and drug development, accurate parameter estimation for models like the Michaelis-Menten equation is critical for predicting biological activity and drug interactions [10]. This guide compares the performance of Classical Least Squares against modern Bayesian alternatives within enzyme parameter estimation research, highlighting foundational principles, practical pitfalls, and data-driven performance metrics [4] [11].

Methodological Foundations: CLS vs. Bayesian Estimation

The core distinction between CLS and Bayesian methods lies in their philosophical approach to uncertainty and incorporation of prior knowledge.

Classical Least Squares (CLS) is a deterministic, frequentist approach. It seeks a single set of parameter values that minimize the sum of squared residuals, providing point estimates [9]. Its validity depends on strict statistical assumptions, including linearity, homoscedasticity (constant error variance), and independence of errors [12] [13]. Violations of these assumptions can lead to biased and unreliable estimates.

Bayesian Estimation is a probabilistic framework. It treats model parameters as random variables with distributions. The method combines prior knowledge (encoded as prior probability distributions) with experimental data (via the likelihood function) to form a posterior probability distribution for the parameters [4]. This directly quantifies estimation uncertainty and allows for the integration of diverse information sources.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logical and procedural differences between these two pathways for parameter estimation.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The choice between CLS and Bayesian methods has tangible impacts on estimation accuracy, robustness, and experimental efficiency.

Foundational Comparison of Methodologies

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each approach.

Table: Foundational Comparison of CLS and Bayesian Estimation Methods

| Aspect | Classical Least Squares (CLS) | Bayesian Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Frequentist; deterministic point estimation. | Probabilistic; parameters as distributions. |

| Use of Prior Knowledge | Not incorporated formally. | Explicitly incorporated via prior distributions. |

| Handling of Limited Data | Prone to overfitting and unreliable estimates [4]. | Prior information stabilizes estimates, mitigating overfitting [4]. |

| Output | Point estimates and approximate confidence intervals. | Full posterior distributions (mean, median, credible intervals). |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Indirect (e.g., confidence intervals). | Direct and inherent to the posterior distribution. |

| Computational Demand | Typically low; analytical or simple numerical solutions. | Can be high; often requires Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. |

| Robustness to Poor Initial Guesses | Can converge to local minima, sensitive to initialization. | More robust if priors are not overly confident and incorrect [4]. |

Performance in Enzyme Parameter Estimation

Recent studies directly comparing these paradigms reveal significant differences in performance, particularly with complex or limited data.

Table: Performance in Enzyme Kinetics & Drug Discovery Applications

| Study Focus | CLS Performance & Limitations | Bayesian/Hybrid Performance | Key Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimating Inhibition Constants (Ki) [10] | Conventional design requires data at multiple substrate/inhibitor concentrations. Prone to bias if model is misspecified. | 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach), integrating Bayesian-like prior structural knowledge, achieved accurate estimation with >75% fewer experiments using a single inhibitor concentration. | 50-BOA reduced required data points by over 75% while maintaining precision [10]. |

| Progress Curve Analysis [14] | Analytical integral methods require precise initial guesses and can be unstable. Direct OLS fitting of differential equations is sensitive to noise. | Numerical approaches using spline interpolation (akin to flexible Bayesian modeling) showed lower dependence on initial guesses and comparable/better accuracy. | Spline-based methods provided robust parameter estimates independent of initial values [14]. |

| Enzyme Activity with GFET Data [11] | Standard nonlinear regression (e.g., CLS) to Michaelis-Menten models may fail with noisy, complex sensor data. | A hybrid Bayesian inversion-supervised learning framework outperformed standard methods in accuracy and robustness for estimating turnover number and Km. | The hybrid framework provided more accurate and robust predictions of enzyme behavior under varying conditions [11]. |

| Drug Discovery Screening [15] | Not directly applicable to sequential experimental design. | Multifidelity Bayesian Optimization (MF-BO) efficiently integrated low (docking), medium (single-point), and high (dose-response) fidelity assays. | MF-BO discovered top-performing histone deacetylase inhibitors with sub-micromolar potency using significantly fewer high-cost experiments [15]. |

Experimental Protocols & Linearization Pitfalls

Canonical vs. Optimized Protocol for Enzyme Inhibition

A key area where methodology impacts practice is in estimating enzyme inhibition constants (K_ic, K_iu), vital for predicting drug-drug interactions [10].

A. Canonical CLS-Based Protocol:

- Determine IC50: Measure percentage control activity across a range of inhibitor concentrations at a single substrate concentration (often ~Km) [10].

- Design Experiment: Measure initial reaction velocities (V0) across a matrix of substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.2Km, Km, 5Km) and inhibitor concentrations (0, 1/3IC50, IC50, 3IC50) [10].

- Model Fitting: Use nonlinear least squares (an extension of CLS) to fit the mixed inhibition velocity equation (Equation 1 in [10]) to the dataset, minimizing the sum of squared residuals between observed and predicted V0.

B. Optimized 50-BOA Protocol (Informs Bayesian Design):

- Determine IC50: As in the canonical protocol.

- Design Experiment: Perform kinetics experiments using only a single inhibitor concentration (I_T) greater than the IC50, across a range of substrate concentrations [10].

- Constrained Fitting: Fit the same kinetic model, but incorporate the known harmonic mean relationship between IC50 and the inhibition constants as a structural prior. This reduces the effective parameter space and allows precise estimation from minimal data [10].

The Pitfall of Linearization in CLS

To enable the use of simple linear least squares, enzyme kinetic models like the Michaelis-Menten equation are often linearized (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plot). This practice introduces significant pitfalls:

- Error Distortion: Linearization transforms the error structure of the data. Errors that are normally distributed in the original V0 measurements become heteroscedastic (non-constant variance) in the transformed space, violating a core OLS assumption [13]. This gives unequal weight to data points, yielding biased estimates.

- Amplification of Noise: Data points at low substrate concentrations (high values in a Lineweaver-Burk plot) become disproportionately influential, amplifying experimental noise and leading to inaccurate parameter estimates.

Modern practice strongly favors direct nonlinear least squares fitting to the original, untransformed model, which preserves the correct error structure, though it requires iterative numerical methods.

Critical Error Assumptions of CLS and Their Violations

The reliability of CLS estimates hinges on several statistical assumptions, the violation of which is common in biochemical data [12] [13].

Table: Key OLS Assumptions and Consequences of Violation in Enzyme Kinetics

| OLS Assumption | Meaning | Common Violation in Kinetic Studies | Consequence & Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity in Parameters | The model must be a linear function of the parameters being estimated. | Enzyme kinetic models (e.g., V_max, K_m) are inherently nonlinear. | Use nonlinear least squares. Linearizing transforms (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk) violate other assumptions. |

| Homoscedasticity | Constant variance of errors across all observations. | Errors in velocity measurements often increase with the magnitude of V0. | Use weighted least squares, where each data point is weighted inversely to its variance. Model the error structure explicitly in Bayesian frameworks. |

| Independence of Errors | No correlation between residual errors. | Progress curve data, where sequential measurements come from the same reaction mixture, show autocorrelation [14]. | Use techniques designed for time-series data (e.g., modeling error covariance) or use progress curve analysis methods [14]. |

| Normality of Errors | Residuals should be normally distributed. | Outliers from experimental artifacts or model misspecification can create heavy-tailed error distributions. | Robust regression techniques or Bayesian methods with t-distributed error models offer more resilience. |

The following workflow diagram for the optimized 50-BOA protocol illustrates how a smarter experimental design, informed by error landscape analysis, can overcome some limitations of traditional CLS approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents & Materials for Enzyme Parameter Estimation Studies

| Item | Typical Function in Experiment | Consideration for Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biocatalyst of interest. Source, purity, and specific activity must be standardized and reported. | Batch-to-batch variability can be modeled as a random effect in hierarchical Bayesian models. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. Should be >99% purity. | Stock concentration accuracy is critical. Errors propagate into parameter estimates. |

| Inhibitor(s) | Compound(s) used to probe enzyme function and mechanism. | Solubility and stability in assay buffer are key. DMSO concentrations must be controlled. |

| Detection System | Method to quantify reaction progress (e.g., fluorescence plate reader, HPLC, GFET sensor [11]). | Defines the noise characteristics (error variance) of the V0 data, impacting weighting in CLS or likelihood in Bayesian. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength, and cofactors for enzyme activity. | Conditions must ensure stable activity throughout the measurement period to avoid confounding trends. |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Validates assay performance (e.g., no-enzyme control, known inhibitor control). | Essential for defining 0% and 100% activity baselines for robust IC50 determination [10]. |

| Software | For analysis (e.g., R, Python, GraphPad Prism, MATLAB, custom Bayesian MCMC tools like Stan). | Choice determines accessibility to advanced methods like Bayesian estimation or spline-based progress curve analysis [14]. |

Classical Least Squares provides a transparent, computationally simple foundation for parameter estimation but is constrained by its strict assumptions and lack of a formal mechanism to incorporate prior knowledge or fully quantify uncertainty. In contrast, Bayesian methods and modern hybrid approaches offer a powerful, probabilistic framework that is particularly advantageous for complex enzyme kinetic studies with limited or noisy data, as prevalent in drug development.

The evidence indicates that Bayesian methods are often preferred when reliable prior knowledge exists, as they provide robust, information-rich estimates and can dramatically reduce experimental burden through optimal design [4] [10]. However, CLS and nonlinear least squares remain vital tools, especially for initial exploratory analysis, when priors are weak or unreliable, or when computational simplicity is paramount. The evolving best practice lies in selecting the tool based on the problem context: using CLS for well-behaved systems with abundant data, and leveraging Bayesian strategies for high-stakes estimation, complex models, or when maximizing information from every experiment is critical.

The transition from traditional least squares estimation to Bayesian methods represents a fundamental paradigm shift in enzyme parameter estimation and metabolic engineering. While classical approaches yield single-point parameter estimates, Bayesian inference provides complete probabilistic distributions that quantify uncertainty—a critical advancement for drug development and bioproduction where experimental data is inherently noisy and limited. This comparison guide objectively evaluates these competing methodologies within the broader thesis that Bayesian frameworks offer superior uncertainty quantification and information integration for complex biological systems, albeit with increased computational demands. Recent research demonstrates how Bayesian methods like BayesianSSA integrate environmental information from perturbation data to improve predictions in metabolic networks [16], while least squares approaches combined with model reduction techniques remain valuable for well-posed parameter estimation problems with complete data [17].

Methodological Comparison: Foundational Principles

Least squares minimization operates on frequentist principles, seeking parameter values that minimize the sum of squared differences between model predictions and observed data. This approach yields deterministic point estimates with confidence intervals derived from asymptotic approximations. In contrast, Bayesian updating treats parameters as random variables with probability distributions [18]. Beginning with prior distributions representing initial beliefs, Bayesian methods update these to posterior distributions via Bayes' theorem, incorporating experimental evidence through likelihood functions. This probabilistic framework naturally quantifies parameter uncertainty and facilitates the integration of diverse data types.

The computational implications are significant: least squares optimization typically requires less computational effort, while Bayesian approaches employing Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods like the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm demand substantially more resources to approximate posterior distributions [18]. However, this computational investment yields richer inference, capturing multi-modal distributions and parameter correlations often missed by point-estimate methods.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The practical performance differences between these methodologies are evident across multiple metrics relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of Parameter Estimation Approaches

| Characteristic | Least Squares Minimization | Bayesian Inference | Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Output | Point estimates with approximate confidence intervals | Full posterior probability distributions | Bayesian posteriors enable direct probability statements about parameters |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Based on curvature of objective function at optimum | Intrinsic to posterior distribution | Bayesian approach captures asymmetric and multi-modal uncertainties |

| Prior Information Integration | Challenging to incorporate formally | Natural framework through prior distributions | Bayesian methods leverage historical data or biological constraints [16] |

| Computational Demand | Generally lower (optimization problem) | Higher (MCMC sampling or variational inference) [18] | Least squares preferable for very large models with complete data |

| Identifiability Assessment | Local evaluation via Hessian matrix | Global evaluation via posterior inspection | Bayesian methods reveal parameter correlations and non-identifiabilities |

| Required Parameters per Reaction | Varies with kinetic model (e.g., 2 for Michaelis-Menten) | Often fewer (e.g., BayesianSSA requires 1 for one-substrate reaction) [16] | Bayesian methods can reduce parameterization burden |

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Case Studies

| Study/Application | Method | Performance Metric | Result | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Central Metabolism Prediction [16] | BayesianSSA | Prediction accuracy for perturbation responses | Successfully integrated environmental data into structural predictions | Bayesian approach reduced indefinite predictions from SSA |

| Trypanosoma brucei Trypanothione Synthetase [17] | Weighted Least Squares | Training error | 0.70 | Least squares effective with complete concentration data |

| Trypanosoma brucei Trypanothione Synthetase [17] | Unweighted Least Squares | Training error | 0.82 | Weighting improved fit for this system |

| Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors [17] | Weighted Least Squares | Training error | 3.61 | Higher error suggests model mismatch or noisy data |

| Metabolic Engineering Optimization [19] | Bayesian Optimization | Convergence to optimum | 22% of experimental points vs. grid search | Dramatic reduction in experimental resources required |

| Progress Curve Analysis [14] | Spline-based Numerical Approach | Dependence on initial estimates | Lower than direct integration methods | Hybrid approaches can mitigate initialization sensitivity |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Objective: Predict metabolic flux responses to enzyme perturbations by integrating structural network information with environmental data.

Protocol:

- Network Structural Encoding: Represent the metabolic network as a stoichiometric matrix (ν) where rows correspond to metabolites and columns to reactions.

- SSA Variable Definition: Define matrix R(r) with elements rj,m = ∂Fj/∂x_m representing reaction sensitivities to metabolite concentrations.

- Prior Distribution Specification: Assign prior distributions to SSA variables based on general biological knowledge or historical data.

- Perturbation Data Integration: Collect perturbation-response datasets from the target environment and compute likelihood functions.

- Posterior Estimation: Use MCMC sampling to obtain posterior distributions for SSA variables given perturbation data.

- Response Prediction: Calculate posterior predictive distributions for flux changes to novel perturbations using the updated SSA variables.

- Validation: Compare predictions against hold-out experimental data or synthetic benchmarks.

Key Advantage: This Bayesian approach reduces indefinite predictions from structural analysis alone by incorporating environmental-specific data.

Objective: Estimate kinetic parameters when only partial concentration measurements are available.

Protocol:

- Model Reduction: Apply Kron reduction to the original kinetic model to eliminate unmeasured species, creating a reduced model governed by the same kinetic law (e.g., mass action).

- Parameter Transformation: Express reduced model parameters as functions of original model parameters.

- Preliminary Estimation: Use weighted or unweighted least squares to fit the reduced model to available time-series concentration data.

- Error Metric Definition: Introduce a trajectory-independent measure quantifying dynamical differences between original and reduced models.

- Original Parameter Estimation: Solve an optimization problem minimizing the difference measure to estimate original model parameters.

- Cross-Validation: Apply leave-one-out cross-validation to determine whether weighted or unweighted least squares is preferable for the specific system.

- Identifiability Check: Assess whether parameters are uniquely determinable from the available measurements.

Key Advantage: Transforms ill-posed estimation problems with incomplete data into well-posed problems through model reduction.

Bayesian vs Least Squares Workflow Comparison

Applications in Drug Development and Metabolic Engineering

Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE): Bayesian approaches significantly enhance MBDoE for parameter precision in enzyme kinetic characterization [20]. By quantifying parameter uncertainty through posterior distributions, researchers can design experiments that maximize information gain about uncertain parameters. This is particularly valuable in drug development where experimental resources are limited and each data point is costly to obtain. Recent advances in MBDoE address challenges in real industrial scenarios, improving robustness and reliability of model calibration [20].

Progress Curve Analysis: Traditional initial slope analysis for enzymatic reactions requires substantial experimental effort. Progress curve analysis offers efficient alternatives, with Bayesian methods providing natural frameworks for handling measurement noise and parameter correlations [14]. Comparative studies show that spline-based numerical approaches exhibit lower dependence on initial parameter estimates compared to direct integration methods, though analytical approaches remain limited in applicability [14].

Bayesian Optimization of Bioproduction: In synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, Bayesian optimization has emerged as a powerful strategy for optimizing complex enzymatic pathways with minimal experimental iterations [19]. The Imperial iGEM 2025 team's BioKernel framework demonstrates how Bayesian optimization can identify optimal induction conditions for multi-enzyme pathways using dramatically fewer experiments than grid search approaches—converging to optima in approximately 22% of the experimental points required by traditional methods [19].

BayesianSSA Integration of Structural and Environmental Information

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Parameter Estimation

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Method Compatibility | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perturbation Datasets | Provide response data for enzyme activity changes | BayesianSSA, Validation for both methods | Quality and relevance to target environment critical [16] |

| Kinetic Model Software | Implement differential equation models of enzyme systems | Both (different implementations) | MATLAB libraries available for Kron reduction approaches [17] |

| MCMC Sampling Algorithms | Generate samples from posterior distributions | Bayesian methods exclusively | Metropolis-Hastings common but computationally intensive [18] |

| Progress Curve Analysis Tools | Extract kinetic parameters from time-course data | Both (different statistical frameworks) | Spline-based methods reduce initial value sensitivity [14] |

| Model-Based DoE Platforms | Design optimal experiments for parameter estimation | Bayesian methods particularly benefit | Maximizes information gain from limited experiments [20] |

| Bayesian Optimization Frameworks | Optimize multi-parameter biological systems | Bayesian methods exclusively | BioKernel offers no-code interface for biologists [19] |

| Structural Network Databases | Provide stoichiometric matrices for metabolic networks | BayesianSSA, Structural analysis | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) commonly used |

Decision Framework and Future Perspectives

The choice between Bayesian and least squares methodologies depends on multiple factors including data completeness, computational resources, and uncertainty quantification needs. For well-posed problems with complete concentration measurements and limited computational resources, least squares approaches combined with model reduction techniques offer practical solutions [17]. When facing indefinite predictions from structural models, partial or noisy data, or requirements for comprehensive uncertainty quantification, Bayesian methods provide superior frameworks [16] [18].

Future developments in enzyme parameter estimation will likely focus on hybrid approaches that leverage strengths of both paradigms. Promising directions include approximate Bayesian computation methods that reduce computational burdens, and sequential experimental design frameworks that integrate MBDoE with real-time Bayesian updating. The increasing availability of high-throughput experimental data from automated platforms will further drive adoption of Bayesian methods that can effectively integrate diverse data types while quantifying uncertainties essential for robust decision-making in drug development.

Decision Framework for Method Selection

Conceptual Foundations: A Comparative Framework

The choice between frequentist and Bayesian statistical paradigms fundamentally shapes how scientists approach parameter estimation, interpret results, and quantify uncertainty. This section delineates the core conceptual components and their practical implications for research.

Core Definitions and Philosophical Contrast

The distinction between the frameworks begins with their definition of probability. The frequentist approach interprets probability as the long-term frequency of an event occurring in repeated identical trials [21]. Parameters (e.g., the true Michaelis constant, Km) are considered fixed but unknown quantities. In contrast, the Bayesian framework views probability as a degree of belief or confidence in an event [21]. Parameters are treated as random variables described by probability distributions, allowing researchers to make direct probabilistic statements about them [21].

The process of learning from data differs accordingly. A frequentist uses the likelihood—the probability of observing the collected data given a specific parameter value—to find the most probable parameter value that explains the evidence, a method known as maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) [22]. The Bayesian approach formalizes learning by starting with a prior distribution, which encapsulates existing knowledge or belief about a parameter before seeing the new data. This prior is then updated with the likelihood of the observed data via Bayes' theorem to yield the posterior distribution [22] [23]. The posterior represents a complete synthesis of old and new information, containing all current knowledge about the parameter [23]. The foundational Bayes' formula is: Posterior ∝ Likelihood × Prior [23].

Table 1: Foundational Comparison of Frequentist and Bayesian Approaches

| Aspect | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Parameters | Fixed, unknown constants [21]. | Random variables with probability distributions [21]. |

| Core Objective | Estimate fixed parameter values (e.g., via MLE) and construct frequency-based intervals [22]. | Derive the posterior probability distribution of parameters [23]. |

| Use of Prior Information | Not formally incorporated. | Formally incorporated via the prior distribution [22]. |

| Interpretation of Uncertainty | Expressed as confidence intervals, based on hypothetical repeated sampling [24]. | Expressed as credible intervals, derived directly from the posterior distribution [24]. |

| Typical Output | Point estimate (e.g., MLE) and a confidence interval [25]. | Entire posterior distribution, summarized by a point estimate (e.g., mean) and a credible interval [23]. |

Illustrative Case Study: Diagnostic Testing

A classic example highlights the practical impact of these philosophical differences [22]. Consider a rare disease with a 0.1% prevalence (prior) and a diagnostic test that is 99% accurate (likelihood). A patient tests positive.

- A frequentist (maximum likelihood) analysis focuses solely on the test accuracy. Since the likelihood of a positive result given the disease (99%) is much higher than the likelihood of a positive result without the disease (1%), one might conclude a high probability of illness [22].

- A Bayesian analysis incorporates the low disease prevalence (prior) via Bayes' rule. The calculation shows the posterior probability of having the disease given a positive test is only about 9%, with a 91% probability of being healthy [22]. This counterintuitive result demonstrates how strong prior information can drastically alter conclusions drawn from data alone.

Uncertainty Quantification: Confidence vs. Credible Intervals

Both paradigms provide interval estimates to quantify uncertainty, but their interpretations are profoundly different and often confused [21].

A 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is a frequentist construct. Its correct interpretation is: "If we were to repeat the experiment an infinite number of times, 95% of the calculated CIs would contain the true, fixed population parameter" [21] [24]. It is a statement about the long-run performance of the method, not about the probability of the parameter lying in a specific observed interval. The parameter is fixed; the interval is random [21].

A 95% Credible Interval (CrI), also called a Bayesian confidence interval, is derived directly from the posterior distribution [24]. Its interpretation is more intuitive: "Given the observed data and the prior, there is a 95% probability that the true parameter value lies within this specific interval" [24]. Here, the parameter is random (described by a distribution), and the interval is fixed for a given posterior.

Table 2: Comparison of Confidence and Credible Intervals

| Feature | 95% Confidence Interval (Frequentist) | 95% Credible Interval (Bayesian) |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Long-run frequency of the interval containing the fixed true parameter [21]. | Degree of belief from the posterior distribution [24]. |

| Interpretation of a Specific Interval | Incorrect: "There's a 95% chance the parameter is in this interval." Correct: "95% of such intervals from repeated experiments contain the parameter." [24] | Correct: "There is a 95% probability the parameter is in this interval." [24] |

| Incorporates Prior Knowledge? | No. | Yes, via the prior distribution. |

| Construction | Based on sampling distribution of the estimator (e.g., mean). | Derived from quantiles of the posterior probability distribution. |

| Width Influenced By | Sample size, data variability [24]. | Sample size, data variability, and prior information. |

Diagram 1: Contrasting Paths to Confidence and Credible Intervals (Max Width: 760px)

Application in Enzyme Kinetics: Bayesian vs. Least Squares Estimation

Estimating parameters like the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) and Michaelis constant (Km) from enzyme kinetic data (e.g., from spectrophotometric assays measuring initial velocity vs. substrate concentration) is a central task in biochemical research and drug discovery. The choice of estimation method significantly impacts the reliability and interpretability of these parameters.

Methodological Comparison

Nonlinear Least Squares (NLLS) is the standard frequentist approach. It finds parameter values that minimize the sum of squared residuals between observed reaction velocities and those predicted by a model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten). It yields a single best-fit parameter set with confidence intervals typically derived from linear approximations, which can be unreliable for nonlinear models with limited data [25].

Bayesian Parameter Estimation treats the parameters (Vmax, Km) as distributions. It starts with priors (e.g., Km must be positive, within a physiologically plausible range), uses the likelihood of the observed kinetic data, and computes a posterior distribution for the parameters [26]. This method naturally handles parameter uncertainty, correlations, and allows for direct probability statements (e.g., "There is a 90% probability that Km is between 2.1 and 3.0 mM").

Supporting Experimental Data and Protocol

A study applying Adaptive Population Monte Carlo Approximate Bayesian Computation (APMC) to estimate parameters of the Farquhar photosynthetic enzyme model provides a relevant experimental template for enzyme kinetics [26].

1. Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Gather paired observational data. In the photosynthesis study, this was net CO₂ assimilation rate (A) vs. intercellular CO₂ concentration (Ci) [26]. For enzyme kinetics, this would be initial velocity (v) vs. substrate concentration ([S]).

- Model Definition: Specify the mechanistic model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten: v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])) and identify parameters to estimate (Vmax, Km).

- Prior Distribution Specification: Define prior probability distributions for each parameter based on literature or pilot experiments (e.g., Vmax ~ Lognormal(μ, σ), Km ~ Uniform(0, 10)) [26].

- Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC): If the likelihood function is intractable, use ABC [26]: a. Sample candidate parameter sets from the priors. b. Simulate synthetic data using the model and candidate parameters. c. Compare simulated data to real data using a distance metric (e.g., sum of squared errors). d. Retain parameters that produce synthetic data "close enough" to the real data, forming an approximate posterior sample [26].

- Posterior Analysis: Analyze the accepted parameters to obtain posterior distributions, point estimates (e.g., median), and credible intervals for Vmax and Km.

2. Key Results from Photosynthesis Study:

- Using 1,948 measured data points for validation, the Bayesian APMC method achieved a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.75 between predicted and observed photosynthesis rates [26].

- The slope of the linear regression between simulated and observed values was 1.04, closely matching the ideal value of 1.0, indicating unbiased predictions [26].

- All estimated parameters fell within their known physiological limits [26].

Table 3: Performance Comparison in Parameter Estimation

| Criterion | Traditional Nonlinear Least Squares (NLLS) | Bayesian Estimation (APMC Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimates | Single point estimates (Vmax, Km). | Full posterior distributions for each parameter. |

| Uncertainty Output | Approximate, symmetric confidence intervals (may assume normality). | Direct, potentially asymmetric credible intervals from the posterior. |

| Handling of Prior Knowledge | Not possible. | Directly incorporated via prior distributions. |

| Model Complexity | Can overfit with many parameters without regularization. | Priors naturally regularize, guarding against overfitting. |

| Result in Validation Study | Not provided in source. | Unbiased predictions (slope ~1.0) and parameters within physiological bounds [26]. |

Diagram 2: Workflow for Bayesian Enzyme Parameter Estimation (Max Width: 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Enzyme Kinetic Studies with Bayesian Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Role in Bayesian Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biological catalyst under study. Its concentration must be carefully controlled and kept constant across assays. | The source of the parameters (Vmax, Km) to be estimated. Uncertainty in enzyme purity/activity can inform prior distributions. |

| Varied Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme. Prepared in a range of concentrations to establish the kinetic curve. | Provides the independent variable ([S]) for the model. Measurement error in stock concentrations should be considered in the error model. |

| Cofactors / Buffers | Maintain optimal and consistent reaction conditions (pH, ionic strength, essential ions). | Ensures data consistency. Variation in conditions between replicates can be modeled as an additional source of uncertainty. |

| Detection Reagent (e.g., NADH/NADPH, chromogenic substrate) | Allows quantitative measurement of product formation or substrate depletion over time (initial velocity). | Generates the dependent variable (v). The assay's measurement error variance is a key component of the likelihood function. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R/Stan, PyMC, JAGS) | Not a wet-lab reagent, but an essential tool. | Used to implement the Bayesian computational sampling (e.g., MCMC, ABC) to compute the posterior distributions from priors and data [26]. |

The comparison reveals a fundamental trade-off. Least squares and maximum likelihood are often computationally simpler and faster, providing straightforward point estimates [25]. Their primary limitation is the frequentist interpretation of uncertainty, which is often misunderstood, and the inability to formally incorporate valuable prior knowledge [24].

Bayesian methods offer a cohesive framework for updating knowledge. Their strength lies in providing an intuitive probabilistic interpretation of parameters and their uncertainties through credible intervals [21] [24]. The explicit use of priors is both an advantage and a point of criticism; while it allows the integration of domain expertise (e.g., physiologically plausible parameter ranges), it also introduces subjectivity [22] [26]. Computationally, Bayesian estimation, especially with complex models, can be more demanding but is increasingly feasible with modern software [26].

In the context of enzyme parameter estimation for drug development, the Bayesian approach holds particular promise. It can formally integrate prior information from related compounds or pre-clinical studies, provide full probability distributions for parameters to better assess risk, and robustly handle complex, nonlinear models common in pharmacology. As computational power grows and regulatory science evolves, Bayesian methods are poised to become a central tool for making more informed, probabilistic decisions in therapeutic research and development [27].

The estimation of kinetic parameters for enzyme-catalyzed reactions is a cornerstone of quantitative biology and drug development. This process transforms experimental data, such as substrate depletion or product formation over time, into the rate constants and binding affinities that define a mechanistic model. The philosophical and methodological choice between Frequentist and Bayesian inference fundamentally shapes this transformation, influencing the certainty of the estimates, the interpretation of uncertainty, and the ultimate utility of the model for prediction [28].

The Frequentist paradigm, anchored in long-run frequency and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), seeks to find the single set of parameter values that maximize the probability of observing the collected data. Uncertainty is expressed through confidence intervals, which are interpreted as the range that would contain the true parameter value in a high percentage of repeated experiments [29]. In contrast, the Bayesian paradigm treats parameters as random variables with probability distributions. It begins with a prior distribution representing belief before seeing the data and updates this belief using Bayes' theorem to form a posterior distribution, which fully quantifies parameter uncertainty in light of the evidence [30]. This article objectively compares these frameworks within the critical context of enzyme parameter estimation, examining their performance, appropriate applications, and practical implementation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Foundational Concepts and Comparative Framework

At their core, the two philosophies answer different questions. Frequentist methods ask, "Given a hypothetical true parameter, what is the probability of observing my data?" The output is a point estimate with a confidence interval. Bayesian methods ask, "Given the observed data, what is the probability distribution for the parameter?" The output is a full posterior distribution from which point estimates (e.g., the mean) and credible intervals can be derived [29] [31].

This difference manifests in their handling of uncertainty and prior knowledge. Frequentist confidence intervals are statements about the reliability of the estimation procedure, not the parameter itself. Bayesian credible intervals are direct probability statements about the parameter [31]. Furthermore, the Bayesian framework formally incorporates existing knowledge or biological constraints through the prior, which can be particularly valuable in data-sparse scenarios common in early-stage research [30] [32].

The following table summarizes the key philosophical and methodological distinctions:

Table: Foundational Comparison of Frequentist and Bayesian Paradigms

| Aspect | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Probability as long-run frequency. Parameters are fixed, unknown constants. | Probability as a degree of belief. Parameters are random variables with distributions. |

| Inferential Goal | Point estimate (MLE) with a confidence interval for the estimator. | Full posterior distribution for the parameter, summarized by credible intervals. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Confidence Interval (CI): If experiment were repeated, X% of CIs would contain the true value. | Credible Interval (CrI): There is an X% probability the true value lies within this interval, given the data and prior. |

| Use of Prior Information | Not formally incorporated. Relies solely on the likelihood of the observed data. | Formally incorporated via the prior distribution, which is updated by data to form the posterior. |

| Typical Computational Methods | Nonlinear Least Squares (NLS), Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), parametric bootstrap [28] [33]. | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) via platforms like Stan [28] [34]. |

| Handling of Complex Models | Can struggle with practical non-identifiability and requires "good" initial guesses [33]. | Priors can help regularize non-identifiable parameters; provides full uncertainty even in complex hierarchies [30] [34]. |

Quantitative Performance in Biological Modeling

Recent comparative studies provide empirical data on the performance of both frameworks under varying experimental conditions relevant to enzyme kinetics, such as data richness and observability of system states.

A 2025 comprehensive analysis compared Bayesian and Frequentist inference across three biological models (Lotka-Volterra, generalized logistic, and an SEIUR epidemic model) using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and 95% Prediction Interval (PI) coverage [28]. The study's key finding was that performance is context-dependent. Frequentist inference, implemented via nonlinear least squares with parametric bootstrap, performed best when data were rich and system states were fully observed. Conversely, Bayesian inference, using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling, excelled in scenarios with high latent-state uncertainty and sparse data, as it more rigorously propagates all sources of uncertainty into the predictions [28].

Table: Performance Comparison in Biological Model Inference [28]

| Condition / Model | Best-Performing Framework | Key Performance Metric Advantage | Primary Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lotka-Volterra (Rich, Fully Observed Data) | Frequentist | Lower Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Efficient point estimation with low uncertainty. |

| SEIUR COVID-19 Model (Sparse, Latent-State Data) | Bayesian | Superior Prediction Interval (PI) Coverage & Weighted Interval Score (WIS) | Better quantification and propagation of complex, hierarchical uncertainty. |

| Generalized Logistic Model | Context-Dependent | Similar MAE, Bayesian better PI coverage with less data. | Bayesian priors stabilize estimates when data is limited. |

In enzyme kinetics, a common challenge is parameter non-identifiability, where different parameter sets fit the data equally well. A unified computational framework highlights that traditional Frequentist methods can fail under non-identifiability, while a Bayesian approach using an informed prior within a constrained unscented Kalman filter (CSUKF) can yield a unique and biologically plausible estimation [34]. This is critical for enzyme models where many parameters must be estimated from limited time-course data.

Application in Practical Research and Drug Development

The choice of statistical philosophy has direct implications for research workflows and decision-making in drug development.

In Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD): Population PK (PopPK) modeling often employs nonlinear mixed-effects models, which have Frequentist (e.g., in Monolix using SAEM algorithm) and Bayesian (e.g., in Stan) implementations [35]. A study on the drug APX3330 used a Frequentist PopPK model to identify high absorption variability and the effect of food, and then used a physiology-based PK (PBPK) model to explore the mechanistic cause [35]. A Bayesian approach could seamlessly integrate uncertainty from the PopPK stage as a prior for the PBPK stage, creating a more cohesive uncertainty pipeline.

In Clinical Trial Design: The FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) actively promotes the use of Bayesian methods through initiatives like the Bayesian Statistical Analysis (BSA) Demonstration Project [36]. Bayesian adaptive designs allow for more efficient trials by using accumulating data to update probabilities, adjust randomization ratios, or make early stopping decisions [32]. This is philosophically aligned with probabilistic belief updating and is particularly valuable in rare disease or oncology trials where patient data is sparse [32].

In Biotechnology and Calibration: Accurate parameter estimation for microbial growth or enzyme activity depends on reliable calibration curves. A Bayesian calibration framework explicitly models the error structure of the measurement system, leading to more robust uncertainty quantification for downstream process parameters like microbial growth rate [30]. This contrasts with Frequentist calibration, which often relies on standard error approximations from a single best-fit curve.

Table: Comparison of Parameter Estimation Methods in an Experimental Study on Protein Denaturation Kinetics [33]

| Estimation Method | Description | Key Finding | Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) / Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Least Squares (NLS) | Standard Frequentist minimization of residual variance. | Prone to bias if error structure is mis-specified. | Higher SSE and MAPE compared to WLS. |

| Weighted Least Squares (WLS) | Frequentist method accounting for non-constant error variance. | Most accurate when error structure is known. | Lowest average SSE (0.18) and MAPE (12.3%). |

| Two-Step Linearized Method | Linearizes the model for initial analytical estimates. | Useful for generating initial guesses for NLS/WLS. | Less accurate than NLS and WLS. |

| Bayesian Inference (Contextual Note) | Not directly tested in this study, but analogous to incorporating weighting and prior knowledge. | The study concludes knowledge of error structure (variance) is crucial—a requirement naturally embedded in full Bayesian modeling [30]. | N/A |

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagent Solutions

Protocol 1: Comparative Frequentist vs. Bayesian Workflow for ODE Models [28]

- Model Definition: Formulate the ordinary differential equation (ODE) model (e.g., enzyme kinetic model like Michaelis-Menten with extensions).

- Structural Identifiability Analysis: Perform a priori analysis (e.g., via differential algebra) to determine which parameters can theoretically be uniquely estimated.

- Frequentist Pathway:

- Estimation: Use a nonlinear least squares (NLS) optimizer (e.g.,

lsqnonlinin MATLAB,optimin R) to find parameters minimizing the sum of squared residuals. - Uncertainty: Perform a parametric bootstrap: Resample residuals, generate synthetic datasets, re-estimate parameters repeatedly to build an empirical sampling distribution for each parameter.

- Forecasting: Generate point forecasts and prediction intervals from the bootstrap ensemble.

- Estimation: Use a nonlinear least squares (NLS) optimizer (e.g.,

- Bayesian Pathway:

- Specification: Define prior distributions for all parameters (e.g., weakly informative based on literature).

- Estimation: Use a probabilistic programming language (e.g., Stan, PyMC) with an MCMC sampler (e.g., Hamiltonian Monte Carlo) to draw samples from the joint posterior distribution.

- Diagnostics: Check chain convergence (Gelman-Rubin R-hat ≈ 1.0) [28], and effective sample size.

- Forecasting: Use posterior parameter samples to simulate the model forward, generating a posterior predictive distribution for forecasts.

- Validation: Compare approaches on metrics like MAE, MSE, and interval coverage using held-out or simulated data.

Protocol 2: Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation with Identifiability Analysis [34]

- Data Collection: Obtain time-course data for substrate and product concentrations under various initial conditions.

- State-Space Formulation: Convert the ODE model into a state-space representation, treating parameters as augmented states with zero rate of change.

- Identifiability Analysis (IA) Module: Apply local (e.g., profile likelihood) or global methods to classify parameters as identifiable, structurally non-identifiable, or practically non-identifiable.

- Resolution Attempt: If non-identifiable parameters exist, use IA module feedback to redesign experiments (e.g., measure additional states, change sampling times) if possible.

- Estimation via Constrained Filtering: If non-identifiability cannot be resolved experimentally, apply the Constrained Square-Root Unscented Kalman Filter (CSUKF). Use information from the IA (e.g., parameter correlations) to formulate an informed prior state distribution for the filter, enabling it to converge to a unique, biologically plausible solution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Estimation | Typical Framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolix | Software | Suite for nonlinear mixed-effects (population) modeling, using SAEM algorithm for MLE. | Frequentist [35] |

| Stan / PyMC | Software | Probabilistic programming languages for specifying Bayesian models and performing MCMC sampling. | Bayesian [28] [30] |

| GastroPlus | Software | Simulates absorption and PK using PBPK models; can integrate prior parameter distributions. | Both (Bayesian-ready) [35] |

calibr8 & murefi Python Packages |

Software | Create custom calibration models and hierarchical process models with built-in uncertainty quantification. | Bayesian-leaning [30] |

| Constrained UKF (CSUKF) | Algorithm | A recursive Bayesian filter for parameter estimation in nonlinear ODEs with built-in constraints. | Bayesian [34] |

| Parametric Bootstrap | Algorithm | A resampling method to approximate the sampling distribution of Frequentist estimators. | Frequentist [28] |

| Informative Prior Distribution | Conceptual | Encodes existing knowledge (e.g., parameter must be positive, likely within a known range) into the analysis. | Bayesian [32] [34] |

The debate between Frequentist certainty and Bayesian belief updating is not about which is universally correct, but which is most useful for a given research problem within enzyme kinetics and drug development. The experimental evidence suggests a guiding principle: Frequentist methods are powerful and straightforward for well-posed problems with abundant, high-quality data and fully observed systems. Their strength lies in providing a clear, single best estimate. Bayesian methods are indispensable for complex, hierarchical models, when data are sparse or noisy, when prior knowledge is meaningful and should be formally included, and when a full probabilistic assessment of all uncertainties is required for decision-making [28] [30] [32].

For the enzyme kinetic modeler, this means assessing the identifiability of their model, the richness and uncertainty of their data, and the ultimate goal of the analysis (e.g., a precise point estimate for a well-characterized enzyme versus a predictive distribution for a novel target with limited data). Increasingly, the field is moving toward hybrid approaches and Bayesian frameworks that offer a cohesive, probabilistic representation of knowledge from experiment to model to clinical application, aligning with the modern demands of predictive and precision medicine [36] [32].

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Least Squares and Bayesian Fitting for Kinetic Models

The construction of a predictive kinetic model for enzymatic reactions hinges on the accurate estimation of fundamental parameters such as the Michaelis constant (Km), the turnover number (kcat), and the maximum reaction velocity (Vmax). These parameters are traditionally derived by fitting experimental rate data to the Henri-Michaelis-Menten equation or its derivatives. The choice of estimation methodology critically impacts the reliability and interpretability of the resulting parameters, especially when dealing with the inherent noise of experimental data and limited data availability [4].

This guide frames the comparison within the ongoing methodological debate between classical least squares regression and Bayesian estimation techniques. Least squares methods, including weighted and non-linear variants, aim to find parameter values that minimize the sum of squared residuals between observed and predicted reaction rates. In contrast, Bayesian methods treat parameters as probability distributions, formally incorporating prior knowledge and quantifying estimation uncertainty [4] [11]. The central thesis explored here is that while least squares methods provide a straightforward point estimate, Bayesian frameworks offer a more robust and informative paradigm for parameter estimation, particularly in data-scarce or high-noise scenarios common in biochemical research and drug development.

Methodological Comparison: Core Principles and Workflows

The fundamental difference between least squares and Bayesian estimation lies in their philosophical approach to parameters and uncertainty. The following diagram contrasts their logical workflows.

Bayesian Estimation begins by formalizing prior beliefs about parameters as probability distributions (e.g., "Km is likely between 1 and 10 µM based on similar enzymes"). These priors are updated with experimental data via Bayes' Theorem to yield a posterior distribution, which fully characterizes parameter uncertainty and correlations [4] [11]. Least Squares Estimation treats parameters as unknown fixed constants. It defines an objective function—typically the residual sum of squares (RSS)—and employs optimization algorithms to find the single parameter set that minimizes it [37]. Advanced implementations may subsequently approximate confidence intervals.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The practical merits and limitations of each approach are best illustrated through direct comparison in key performance areas relevant to researchers.

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of Estimation Approaches

| Aspect | Bayesian Estimation | Least Squares Estimation | Key Implications for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Parameters are random variables with probability distributions [4]. | Parameters are fixed, unknown constants to be determined [37]. | Bayesianism naturally quantifies uncertainty; frequentism provides precise point estimates. |

| Treatment of Prior Knowledge | Explicitly incorporated via prior distributions. Essential for stable estimation with limited data [4]. | Implicitly incorporated through initial guesses for optimization. No formal mechanism for inclusion [14]. | Bayesian methods are superior for leveraging literature or expert knowledge, guiding system identification [11]. |

| Output & Uncertainty | Full posterior distribution for all parameters. Provides credible intervals, correlations, and prediction uncertainty [4]. | Point estimates. Confidence intervals require additional linear approximation (e.g., error propagation) [37]. | Bayesian output is richer for risk analysis and decision-making in drug development. |

| Computational Demand | High. Requires Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) or variational inference for sampling the posterior [4]. | Low to Moderate. Involves solving a deterministic optimization problem [14] [37]. | Least squares is more accessible and faster for routine analysis. |

| Robustness to Poor Initial Guesses | High. Well-specified prior distributions can guide estimation away from poor regions [4]. | Low. Can converge to local minima, making results sensitive to initial values [14]. | Bayesian methods reduce the risk of non-identifiability and optimization artifacts. |

| Handling Limited/Noisy Data | High. Prior regularization prevents overfitting; posterior reflects increased uncertainty [4]. | Low. Prone to overfitting and unreliable estimates; uncertainty may be underestimated [4]. | Bayesian is preferred for novel enzymes or expensive experiments where data is scarce. |

A 2025 review highlights that Bayesian estimation is preferred when prior knowledge is reliable, as it efficiently regularizes the problem. However, it can yield misleading results if the modeler is overly confident in incorrect prior assumptions. Least squares subset-selection methods, while computationally more expensive, can be less susceptible to issues from poor initial guesses and offer insight into parameter estimability and model simplification opportunities [4].

Experimental Data & Case Studies

Recent studies provide empirical data comparing these methodologies in action.

Table 2: Summary of Key Comparative Case Studies

| Study Context | Methodologies Compared | Key Performance Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroisomerization Mechanism | Subset-selection vs. Bayesian estimation. | Both produced different estimates from same data. Bayesian favored with good priors; subset-selection more robust to bad initial guesses and offered model insights [4]. | [4] |

| Enzyme Parameter Estimation from GFET Data | Standard Bayesian inversion vs. Hybrid ML-Bayesian framework. | The proposed hybrid framework (deep neural net + Bayesian inversion) outperformed standard Bayesian and ML methods in accuracy and robustness for estimating kcat and Km [11]. | [11] |

| Progress Curve Analysis | Analytical (integral) methods vs. Numerical (spline interpolation) methods. | Numerical approach using spline interpolation showed lower dependence on initial parameter guesses, achieving accuracy comparable to analytical methods but with wider applicability [14]. | [14] |

| Analysis of Historical Michaelis-Menten Data | Automated Least Squares (Excel Solver). | Demonstrated reliable parameter estimation (Km=0.023±0.003 M, Vmax=0.088±0.004 °/min) from classic sucrose hydrolysis data, including standard errors [37]. | [37] |

A pivotal finding supporting more flexible experimental design comes from a 2023 study which demonstrated that reliable parameter estimation does not strictly require initial rate measurements. Using the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation, researchers showed that analyzing a single time-point per substrate concentration, even with up to 50-70% substrate conversion, can yield good estimates, though with a quantifiable systematic error in Km. This greatly facilitates the study of systems where continuous monitoring or numerous time-points are impractical [38].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Progress Curve Analysis via Numerical Integration

This protocol is adapted from methodologies comparing analytical and numerical approaches for progress curve analysis [14] [38].

- Reaction Setup: Perform the enzymatic reaction across a range of initial substrate concentrations ([S]₀). For each, monitor the product concentration ([P]) or substrate depletion over time. Continuous (e.g., spectrophotometry) or discrete (e.g., HPLC) methods can be used [38].

- Data Smoothing (if noisy): Fit a smoothing spline to the [P] vs. time (t) data for each progress curve. This step transforms discrete data into a continuous function.

- Numerical Differentiation: Differentiate the spline function analytically to obtain an estimate of the instantaneous reaction rate, v(t) = d[P]/dt, at desired time points.

- Substrate Calculation: Calculate the corresponding substrate concentration at each time t as S = [S]₀ - P.

- Parameter Estimation: Construct a dataset of paired values (v(t), S) from all progress curves. Use non-linear regression (least squares) or Bayesian inference to fit these data to the Michaelis-Menten model, v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])*.

Protocol: Bayesian Parameter Estimation for GFET Enzymatic Data

This protocol outlines the workflow for a hybrid machine learning-Bayesian framework as applied to graphene field-effect transistor (GFET) data [11].

- GFET Experimentation: Immobilize the target enzyme (e.g., horseradish peroxidase) on a GFET sensor. Acquire real-time electrical response data (e.g., Dirac point shift, conductance change) as the enzymatic reaction proceeds under varying substrate concentrations and environmental conditions.

- Data Calibration: Convert the recorded electrical signals into reaction rate (v) data using a calibration model specific to the GFET-enzyme system.

- Deep Learning Surrogate Model: Train a deep neural network (e.g., a multilayer perceptron) using a subset of the experimental data. The network learns to predict reaction rates given inputs of substrate concentration, enzyme details, and environmental factors (pH, temperature).

- Bayesian Inversion: Define prior distributions for the target kinetic parameters (Km, kcat). Use the trained neural network as a fast, accurate forward model within a Bayesian inference framework (e.g., MCMC sampling). The algorithm samples the parameter space to find distributions that maximize the likelihood of observing the full experimental dataset.

- Validation: Compare posterior parameter distributions against estimates obtained from traditional fitting methods or literature values. Use hold-out experimental data for prediction validation.

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental and computational workflow for modern enzyme kinetic parameter estimation, integrating elements from both protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Item / Solution | Function in Kinetic Studies | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Preparation | The catalyst of interest. Concentration ([E]₀) must be known accurately and activity stable throughout assay. | Source (recombinant, native), specific activity, and storage buffer are critical for reproducibility. |

| Substrate Solutions | The molecule transformed by the enzyme. Prepared at a range of concentrations bracketing the expected Km. | Requires high purity. Stability under assay conditions must be verified. Solubility can be a limiting factor. |

| Activity Assay Buffer | Maintains optimal and constant pH, ionic strength, and provides essential cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺). | Buffer must not inhibit the enzyme. Common choices: Tris-HCl, phosphate, HEPES. |

| Detection System | Quantifies the appearance of product or disappearance of substrate over time. | Spectrophotometric: Uses chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates. GFET Sensor: Monitors real-time electrical changes from surface reactions [11]. Chromatographic (HPLC): For non-chromogenic reactions, used in discontinuous assays [38]. |

| Parameter Estimation Software | Performs the numerical optimization or statistical inference to calculate parameters from data. | Least Squares: Excel Solver with GRG algorithm [37], GraphPad Prism, custom scripts in R/Python. Bayesian: Probabilistic programming languages (Stan, PyMC, TensorFlow Probability). |

| Reference Kinetic Datasets | Validated experimental data for method benchmarking and training of machine learning models. | Used to test new estimation algorithms or train frameworks like UniKP [39]. Public databases include BRENDA and SABIO-RK. |

The choice between least squares and Bayesian parameter estimation is not merely technical but strategic, impacting experimental design, resource allocation, and interpretability of results.

For routine characterization of enzymes under standard conditions with ample, high-quality data, non-linear least squares remains the workhorse due to its simplicity, speed, and wide availability in software tools [37]. Researchers should employ progress curve analysis to maximize data yield from experiments [14] [38] and use subset-selection techniques to avoid overfitting when model complexity increases [4].