Benchmarking Enzyme Stability in Mutants: Integrating Multi-Omics, Machine Learning, and High-Throughput Assays

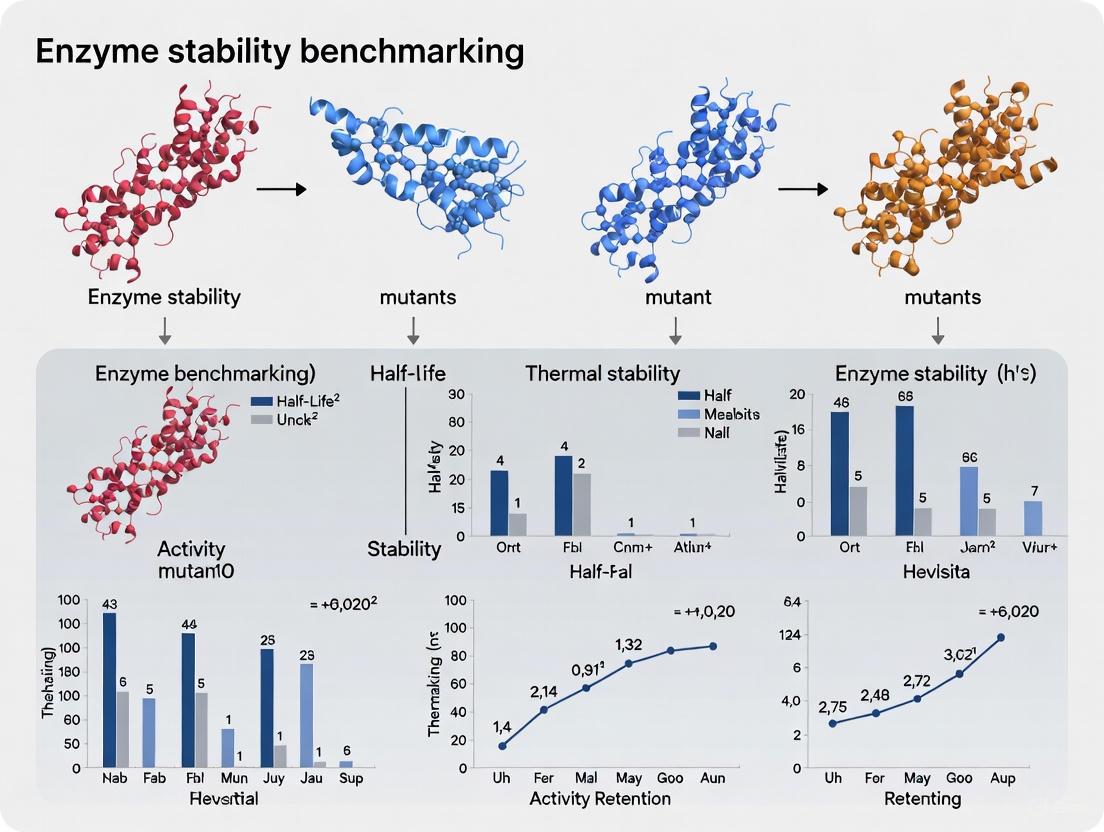

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking enzyme stability across engineered mutants, addressing a critical need in biocatalyst and therapeutic protein development.

Benchmarking Enzyme Stability in Mutants: Integrating Multi-Omics, Machine Learning, and High-Throughput Assays

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking enzyme stability across engineered mutants, addressing a critical need in biocatalyst and therapeutic protein development. We synthesize foundational concepts linking stability to activity, explore cutting-edge methodological advances from multi-omics analyses to machine learning-driven predictions, and address troubleshooting for the ubiquitous stability-activity trade-off. The content further delivers rigorous validation protocols, comparing computational models and experimental techniques like thermal proteome profiling. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review serves as a strategic guide for systematically evaluating and enhancing enzyme stability to meet industrial and biomedical demands.

The Fundamentals of Enzyme Stability: From Molecular Principles to Mutant Phenotypes

In enzyme engineering and drug development, quantifying stability is paramount for characterizing mutants and guiding design. Researchers rely on distinct metrics—melting temperature (Tₘ), half-life (t₁/₂), and free energy of folding (ΔG)—each providing unique insights into a protein's structural robustness. While Tₘ and t₁/₂ assess kinetic stability under harsh conditions, ΔG measures thermodynamic stability under equilibrium. Understanding the applications, methodologies, and limitations of these metrics is essential for selecting the appropriate assay in benchmarking studies, as no single metric provides a complete picture of enzyme behavior.

Metric Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of the three primary stability metrics.

| Metric | What It Measures | Stability Type | Key Experimental Methods | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature (Tₘ) | Temperature at which 50% of the protein is unfolded [1] | Mainly thermodynamic (under equilibrium conditions) | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy [2] | Quick stability ranking, initial mutant screening [3] | Does not directly measure the free energy of folding (ΔG); can miss kinetic stability components [1] |

| Half-Life (t₁/₂) | Time for a protein to lose 50% of its initial activity at a defined temperature [4] | Kinetic (irreversible denaturation) | Incubation at elevated temperature followed by activity assays [4] | Industrial enzyme engineering (e.g., detergents, biocatalysts) [4] | Measures irreversible loss (unfolding + aggregation); results are condition-specific [4] |

| Free Energy of Folding (ΔG) | Energy difference between the folded (N) and unfolded (U) states at equilibrium [2] [5] | Thermodynamic (reversible denaturation) | Chemical Denaturation (urea, guanidinium HCl) monitored by CD or fluorescence [4] [2] | Gold standard for fundamental stability; reveals mutational effects [4] [6] | Experimentally demanding; requires reversible folding; less suitable for large/complex proteins [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Measuring Melting Temperature (Tₘ)

The Tₘ is widely used for its experimental speed, making it ideal for high-throughput screening of enzyme mutants [3].

Detailed Protocol: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC directly measures the heat absorbed by a protein solution as it is heated, providing a direct readout of Tₘ.

- Principle: The instrument applies a constant temperature increase to both a sample cell (containing the protein) and a reference cell (containing buffer). The differential power required to maintain both cells at the same temperature is measured. As the protein unfolds, it absorbs excess heat, resulting in an endothermic peak.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Purified protein is dialyzed into a suitable buffer and degassed to prevent air bubble formation.

- Loading: The sample and reference cells are loaded with protein solution and buffer, respectively.

- Scanning: The temperature is ramped at a constant rate (e.g., 1°C per minute) while continuously measuring the heat flow.

- Data Analysis: The resulting thermogram is plotted as heat capacity (Cp) versus temperature. The Tₘ is the temperature at the peak maximum of the thermal transition.

The workflow for this experimental method is standardized, as follows:

Determining Half-Life (t₁/₂) at Elevated Temperature

This method assesses kinetic stability, which is critical for enzymes in industrial processes where long-term functional stability is required [4].

Detailed Protocol: Thermal Inactivation and Activity Assay

- Principle: Enzyme samples are incubated at a specific, challenging temperature. Aliquots are removed at timed intervals, cooled, and assayed for remaining activity. The decay of activity over time is used to calculate the half-life.

- Procedure:

- Incubation: Multiple aliquots of a purified enzyme solution are placed in a heated thermal block or water bath set to the target temperature (e.g., 55°C or 60°C).

- Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes), an aliquot is removed and immediately placed on ice to halt denaturation.

- Activity Assay: The residual enzymatic activity of each aliquot is measured under standard, optimized assay conditions (e.g., by monitoring substrate conversion per unit time).

- Data Analysis: The natural logarithm of the residual activity (ln[A]) is plotted against the incubation time (t). The data are fitted to a first-order decay model: ln[A] = -kt + ln[A₀], where

kis the inactivation rate constant. The half-life is then calculated as: t₁/₂ = ln(2) / k [4].

The following diagram illustrates the logical and experimental sequence:

Quantifying Free Energy of Folding (ΔG)

ΔG provides the fundamental thermodynamic parameter for stability, typically measured through reversible chemical denaturation [2] [6].

Detailed Protocol: Urea-Induced Denaturation Monitored by Fluorescence

- Principle: A denaturant (e.g., urea) progressively shifts the equilibrium between the folded (N) and unfolded (U) states. A spectroscopic signal sensitive to conformation (e.g., intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence) tracks this transition.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: A series of protein solutions are prepared with identical protein concentration but varying concentrations of denaturant (e.g., 0 M to 8 M urea).

- Equilibration: Solutions are incubated to ensure folding/unfolding equilibrium is reached.

- Measurement: The fluorescence emission spectrum (or intensity at a specific wavelength) is recorded for each sample. The folded and unfolded states have distinct spectral properties.

- Data Analysis: The signal is plotted against denaturant concentration to generate a sigmoidal denaturation curve. Data is fitted to a model that extrapolates the stability to zero denaturant, yielding ΔG(H₂O), the folding free energy in water [4] [2].

The experimental workflow is a sequential process, visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful stability assays require specific reagents and instruments. The table below lists essential solutions and materials for the described protocols.

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Urea / Guanidine HCl | Chemical denaturants that disrupt hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, enabling ΔG measurement [4]. | Creating a concentration gradient for equilibrium unfolding studies. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Instrument that directly measures heat capacity changes during thermal unfolding to determine Tₘ [2]. | Precisely measuring the Tₘ of a purified protein mutant. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrophotometer | Instrument that measures changes in secondary structure during thermal or chemical denaturation [2]. | Tracking the loss of alpha-helical content as temperature increases. |

| Fluorescence Spectrophotometer | Instrument that detects changes in the local environment of aromatic residues (Trp, Tyr), monitoring unfolding [2]. | Following the shift in tryptophan fluorescence emission during urea titration. |

| Controlled-Temperature Water Bath | Provides a stable elevated temperature environment for thermal inactivation studies [4]. | Incubating enzyme aliquots for half-life (t₁/₂) determination. |

| Trypsin / Chymotrypsin | Proteases used in high-throughput proteolysis assays to measure folded stability based on cleavage resistance [6]. | cDNA display proteolysis to measure stability of thousands of variants in parallel. |

Selecting the optimal stability metric is critical for effective enzyme benchmarking. Tₘ offers speed for initial screening, t₁/₂ provides practical insight for industrial application, and ΔG delivers fundamental thermodynamic understanding. A robust strategy often employs Tₘ for high-throughput mutant screening, followed by deeper characterization of lead candidates using t₁/₂ and ΔG. Emerging high-throughput technologies, like cDNA display proteolysis, are now enabling the simultaneous measurement of ΔG for hundreds of thousands of variants, promising to revolutionize our understanding of sequence-stability relationships and accelerate the design of superior enzymes for research and industry [6].

For researchers in drug development and enzyme engineering, achieving predictable and enhanced enzyme stability is a paramount goal. The pursuit of robust biocatalysts for industrial and therapeutic applications hinges on a fundamental understanding of the molecular interactions that govern protein stability. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three key non-covalent interactions—hydrophobic interactions, salt bridges, and hydrogen bonding networks—framed within the context of benchmarking enzyme stability across engineered mutants. We objectively summarize experimental data on their relative contributions and provide detailed methodologies for their investigation, serving as a foundation for rational enzyme design.

Comparative Analysis of Stabilizing Interactions

The thermodynamic and kinetic stability of an enzyme is an emergent property of its amino acid sequence and three-dimensional structure, orchestrated by a complex network of non-covalent interactions. The following table provides a quantitative comparison of the three primary stabilizing forces based on experimental and simulation data.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Molecular Stabilizing Interactions

| Interaction Type | Relative Contribution to Mechanical Stability | Primary Role in Stability | Key Structural Features | Susceptibility to Environmental Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interactions | ~20-33% of total mechanical force [7] | Major driver of protein folding; provides thermodynamic stability through the hydrophobic effect [8] | Clustering of non-polar side chains; cavity minimization [8] | High temperatures disrupt organized water shell, leading to unfolding |

| Salt Bridges | Not quantified in mechanical studies | Provides conformational specificity and geometric constraints; contributes to stability, particularly in buried environments [9] | Oppositely charged groups (Asp/Glu with His/Arg/Lys) within 4Å; specific geometric preferences [9] | Sensitive to pH changes and high ionic strength that can screen electrostatic forces |

| Hydrogen Bonds | ~67-80% of total mechanical force [7] | Primary contributor to mechanical strength; stabilizes secondary structures and domain interfaces | Donor-H...Acceptor atoms within hydrogen bonding distance; direction-dependent strength | Competed by water molecules; sensitive to urea and other hydrogen-bond disrupting agents |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Stabilizing Interactions

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation for Interaction Network Analysis

Purpose: To characterize the dynamic behavior of hydrophobic cores, salt bridge networks, and hydrogen bonding patterns under varying conditions [10] [11] [8].

Workflow:

- System Preparation: Obtain protein structure from PDB or homology modeling. Add missing hydrogens and assign protonation states appropriate for physiological pH (e.g., +1 for histidine δ-nitrogen) [10].

- Solvation and Ionization: Solvate the system in an explicit water model (e.g., TIP3P). Add ions to simulate physiological ionic strength (e.g., 75 mM NaCl) [10].

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration: Perform energy minimization using conjugate gradient algorithms. Equilibrate the system with constant pressure and temperature (CPT) simulations using a Langevin algorithm [10].

- Production Run: Conduct MD simulations (e.g., using NAMD with CHARMM forcefield). Apply periodic boundary conditions and handle long-range electrostatics with Particle Mesh Ewald method [10].

- Trajectory Analysis:

Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) for Mechanical Stability Assessment

Purpose: To quantitatively deconvolute the relative contributions of hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds to mechanical stability [7].

Workflow:

- System Setup: Prepare solvated and equilibrated protein system as in standard MD protocols.

- Constant-Velocity Pulling: Apply a constant velocity pulling force to selected protein atoms while constraining others.

- Force-Extension Curve Generation: Monitor the force required to unfold the protein as a function of extension.

- Interaction Deconvolution: Analyze force peaks by monitoring:

- Hydrophobic Contribution: Track the unraveling of hydrophobic surface area. Hydrophobic force peaks typically appear at larger protein extensions [7].

- Hydrogen Bond Contribution: Identify force peaks corresponding to the rupture of hydrogen bonds, which occur at shorter extensions and constitute the majority (67-80%) of the mechanical resistance [7].

Virtual Saturation Mutagenesis for Stability Prediction

Purpose: To computationally screen for stabilizing mutations by predicting changes in folding free energy (ΔΔG) [8].

Workflow:

- Target Selection: Identify candidate residues for mutation, such as those in short loops with cavities or high B-factor regions [8].

- Virtual Mutagenesis: Generate all 19 possible amino acid substitutions at each target position.

- Free Energy Calculation: Use tools like FoldX or Rosetta to calculate the predicted change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) for each mutant [11] [8].

- Variant Prioritization: Select mutants with predicted stabilizing ΔΔG values (ΔΔG < 0) for experimental validation. Mutations that fill cavities with large hydrophobic side chains (e.g., Phe, Trp, Tyr) are particularly effective in short-loop regions [8].

Integration of Stabilizing Interactions in Enzyme Engineering

The most successful enzyme engineering strategies leverage multiple stabilizing interactions simultaneously. The following diagram illustrates a integrative workflow, such as the iCASE strategy, that combines computational analysis of dynamics with experimental screening to engineer highly stable enzymes [11].

Diagram 1: Integrative enzyme engineering workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme Stability Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan-based Supports | Biocompatible, biodegradable natural polymer for enzyme immobilization via covalent or ionic attachment [12] | Enhancing enzyme reusability and resistance to harsh pH and solvents [12] |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) | High-surface-area inorganic carriers for adsorption-based immobilization [12] | Bio-catalysis in energy applications; improving stability and facilitating enzyme separation [12] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Multifunctional linker for covalent immobilization; forms self-assembled monolayers (SAM) on carrier surfaces [12] | Creating stable covalent bonds between enzyme amino groups and support materials [12] |

| FoldX / Rosetta | Software for predicting changes in folding free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation [8] | Virtual screening of stabilizing mutations during rational design [11] [8] |

| NAMD with CHARMM Forcefield | Molecular dynamics simulation software and parameters [10] | Simulating enzyme dynamics, interaction networks, and unfolding pathways [10] [7] |

Benchmarking enzyme stability across mutants requires a multifaceted approach that acknowledges the distinct yet complementary roles of hydrophobic interactions, salt bridges, and hydrogen bonding networks. Hydrogen bonds provide the core mechanical strength, hydrophobic interactions drive folding and thermodynamic stability, and salt bridges offer geometric specificity. Modern engineering strategies like iCASE [11] and short-loop engineering [8] successfully integrate computational predictions of these interactions with high-throughput experimental validation, enabling the systematic development of robust biocatalysts for therapeutic and industrial applications. The continued refinement of these approaches, particularly with advances in machine learning, promises to further accelerate the design of enzymes with tailored stability profiles.

The relationship between an enzyme's structural stability and its catalytic activity represents a fundamental challenge in enzyme engineering. Engineering highly active enzymes often inadvertently reduces their stability, while over-stabilization can rigidify the structure and impair the conformational flexibility essential for catalysis [13]. This delicate balance is governed by biophysical principles where catalytic residues are often intrinsically destabilizing to the native structure, requiring surrounding residues to provide compensatory stabilization [14].

This guide objectively compares this trade-off through two exemplary enzyme systems: Kemp eliminases, which serve as models for de novo enzyme design, and β-glucanases, industrially important enzymes whose performance is routinely enhanced through protein engineering. By comparing quantitative data and experimental approaches across these systems, we provide researchers with actionable insights for benchmarking enzyme stability and activity in engineered variants.

Case Study 1: Kemp Eliminases

Experimental Approaches and Workflow

The engineering of Kemp eliminases has been revolutionized by fully computational workflows that generate efficient enzymes without requiring extensive mutant library screening [15]. These approaches leverage:

- Backbone generation using fragments from natural TIM-barrel proteins

- Geometric matching to position the catalytic theozyme (transition-state model)

- Atomistic design using Rosetta to optimize active-site residues

- "Fuzzy-logic" filtering to balance potentially conflicting objectives like low system energy and high catalytic base desolvation

Advanced engineering strategies combine NMR-identified catalytic hotspots with computational design (FuncLib) to predict stabilizing mutations that enhance activity without compromising stability [16]. This method restricts amino acid choices to those likely in natural protein families, then ranks multi-mutant variants by predicted stability.

Figure 1: Computational design workflow for high-efficiency Kemp eliminases, integrating scaffold selection, theozyme positioning, and stability optimization [15] [16].

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Kemp Eliminase Variants

Table 1: Catalytic parameters and stability of engineered Kemp eliminases

| Variant / Description | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM, M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Catalytic Rate (kcat, s⁻¹) | Thermal Stability | Key Mutations from Natural | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Computational Designs | 1-420 | 0.006-0.7 | Not specified | Not specified | [15] |

| Des27/Des61 (Initial designs) | 130-210 | <1 | Cooperative unfolding | 30-93% sequence diversity | [15] |

| Optimized Des61 variant | 3,600 | 0.85 | High (cooperative unfolding) | 5-8 specific mutations | [15] |

| Highly Stable Design | 12,700 | 2.8 | >85°C | >140 mutations | [15] |

| Most Proficient Variant | ~430,000 | ~1700 | 80°C denaturation temperature | Includes W229D, F290W | [16] |

| Natural Enzyme Level | >100,000 | 30 | Not specified | Novel active site | [15] |

The data demonstrates remarkable progress, with catalytic efficiencies increasing by up to five orders of magnitude from early designs to the most recent variants. The most proficient engineered Kemp eliminase now achieves a catalytic efficiency of ~4.3×10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹ with a remarkable kcat of ~1700 s⁻¹, rivaling natural enzymes [16]. This represents a ∼3-fold enhancement over an already optimized variant, demonstrating that simultaneous improvement of both activity and stability is achievable through advanced computational methods.

Case Study 2: β-Glucanases

Experimental Approaches and Workflow

β-Glucanase engineering primarily employs experimental directed evolution approaches, complemented by rational design. A representative study using Atmospheric and Room Temperature Plasma (ARTP) mutagenesis on Trichoderma reesei generated mutant libraries screened for improved β-glucanase activity [17]. The key steps include:

- Random mutagenesis using ARTP at optimal lethality rates (85-95%)

- Primary screening via Congo red hydrolysis zone measurement

- Secondary screening through shake-flask fermentation and enzyme assays

- Stability assessment across multiple generations

- Multi-omics analysis (transcriptomics and metabolomics) of superior mutants

Alternative protein engineering strategies include error-prone PCR, site-saturation mutagenesis, DNA recombination, and sequence alignment [18]. Semi-rational approaches incorporate N- and C-terminal modifications, surface charge optimization, intermolecular force enhancement, and rigidification of flexible regions.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for engineering β-glucanases through ARTP mutagenesis and multi-tier screening [17].

Quantitative Performance Comparison of β-Glucanase Variants

Table 2: Performance comparison of engineered β-glucanase variants

| Variant / Source | Enzyme Activity | Improvement Over Wild-Type | Stability Characteristics | Engineering Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. reesei CICC 2626 (WT) | 28.34 U/mL | Baseline | Not specified | N/A | [17] |

| ARTP-9 Mutant | 45.12 U/mL | 56.23% increase | Transgenerational stability over 7 generations | ARTP mutagenesis | [17] |

| ARTP-3 Mutant | 45.69 U/mL | 61.22% increase | Unstable over generations | ARTP mutagenesis | [17] |

| Paecilomyces sp. FLH30 | 61,754 U/mL | Not applicable | Not specified | Heterologous expression in P. pastoris | [17] |

| Arthrobacter KQ11 Mutant | 6.27 U/mL | 1.5-fold increase | Not specified | ARTP mutagenesis | [17] |

The ARTP-9 mutant of T. reesei demonstrates the successful balancing of activity and stability, maintaining 56.23% higher activity than wild-type across seven generations without significant衰减 [17]. This contrasts with the higher-activity but unstable ARTP-3 mutant, whose activity declined markedly over generations, exemplifying the stability-activity trade-off. Multi-omics analysis of superior mutants revealed 1,793 differentially expressed genes and enrichment in metabolic pathways related to cofactors and carbohydrate energy metabolism, providing insights into the molecular basis of improved performance [17].

Comparative Analysis & Research Applications

Cross-System Comparison of Engineering Strategies

Table 3: Comparison of engineering approaches between Kemp eliminases and β-glucanases

| Engineering Aspect | Kemp Eliminases | β-Glucanases |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Engineering Strategy | Computational design | Directed evolution + Rational design |

| Key Methods | Rosetta design, FuncLib, PROSS stability optimization | ARTP mutagenesis, error-prone PCR, site-saturation mutagenesis |

| Library Size | Dozens of designs | Thousands of mutants |

| Screening Throughput | Low-throughput individual characterization | High-throughput Congo red plating |

| Stability Assessment | Thermal denaturation temperature | Transgenerational stability, thermal stability assays |

| Activity Characterization | Steady-state kinetics (kcat, KM) | Enzyme activity (U/mL), hydrolysis zone assays |

| Optimization Cycle | Fully computational design-test cycles | Iterative mutation-screening cycles |

| Key Outcomes | Orders of magnitude efficiency improvements | 50-60% activity improvements |

The comparison reveals fundamentally different engineering philosophies: Kemp eliminases exemplify the rational design paradigm with precise atomic-level control, while β-glucanase engineering employs high-throughput experimental screening of diverse mutant libraries. Kemp eliminase engineering achieves more dramatic catalytic improvements but requires sophisticated computational infrastructure and expertise. Conversely, β-glucanase engineering offers more modest gains but utilizes more accessible laboratory techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Key research reagents and methods for enzyme stability-activity studies

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | Protein structure prediction & design | Kemp eliminase active site design [15] |

| FuncLib Server | Computational design of stable, multiple mutant variants | Kemp eliminase optimization [16] |

| ARTP Mutagenesis | Random mutagenesis method for library generation | β-glucanase mutant generation [17] |

| Congo Red Staining | High-throughput screening via hydrolysis zone detection | β-glucanase primary screening [17] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Identifying catalytic hotspots via chemical shift perturbations | Kemp eliminase engineering [16] |

| Thermal Denaturation Assays | Quantifying enzyme stability via melting temperature | Kemp eliminase stability assessment [15] |

| Transcriptomics/Metabolomics | Systems-level analysis of mutant strains | β-glucanase mutant analysis [17] |

| Enzyme Proximity Sequencing (EP-Seq) | Deep mutational scanning of stability and activity | General enzyme engineering [13] |

The comparative analysis of Kemp eliminases and β-glucanases reveals that while the stability-activity trade-off presents a universal challenge in enzyme engineering, its manifestation and solutions differ substantially across enzyme systems. Computational design approaches excel for novel reaction catalysis where natural templates are unavailable, enabling dramatic activity enhancements through atomic-level precision. Conversely, directed evolution methods remain highly effective for optimizing natural enzymes like β-glucanases, providing robust improvements through experimental screening.

For researchers benchmarking enzyme mutants, the choice of strategy should be guided by system constraints and objectives. When structural knowledge and computational resources are available, FuncLib-guided designs and stability-activity trade-off analysis can efficiently identify enhanced variants. For systems with established high-throughput assays, directed evolution coupled with multi-omics analysis provides a powerful alternative. Emerging technologies like Enzyme Proximity Sequencing promise to further bridge this divide by enabling large-scale characterization of both stability and activity phenotypes [13], potentially offering the best of both rational and evolutionary approaches for future enzyme engineering endeavors.

How Mutations Distal to the Active Site Influence Global Stability and Catalytic Efficiency

The engineering of enzymes for enhanced catalytic performance and stability is a central goal in biotechnology and drug development. While traditional enzyme design has focused on optimizing active-site residues, emerging evidence highlights the critical, yet poorly understood, role of mutations distant from the active site. This review objectively compares the effects of distal versus active-site mutations on global stability and catalytic efficiency, synthesizing recent experimental findings to provide benchmarks for enzyme engineering campaigns.

Comparative Analysis of Distal vs. Active-Site Mutations

Quantitative Comparison of Mutational Effects

Table 1: Functional Effects of Core (Active-Site) and Shell (Distal) Mutations in Kemp Eliminases

| Enzyme Variant | # Mutations | kcat/KM (M⁻¹ s⁻¹) | Fold Increase vs. Designed | Melting Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HG3-Designed | - | 1,300 ± 90 | - | 51 |

| HG3-Shell | 9 | 4,900 ± 500 | 4 | 50 |

| HG3-Core | 7 | 120,000 ± 20,000 | 90 | 52 |

| HG3-Evolved | 16 | 150,000 ± 40,000 | 120 | 56 |

| 1A53-Designed | - | 4.6 ± 0.4 | - | 74 |

| 1A53-Shell | 8 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 1 | 65 |

| 1A53-Core | 6 | 7,000 ± 3,000 | 1,500 | 85 |

| 1A53-Evolved | 14 | 14,000 ± 3,000 | 3,000 | 61 |

| KE70-Designed | - | 150 ± 7 | - | 57 |

| KE70-Shell | 2 | 130 ± 30 | 1 | 60 |

| KE70-Core | 6 | 22,000 ± 4,000 | 150 | 55 |

| KE70-Evolved | 8 | 26,000 ± 2,000 | 170 | 58 |

Data compiled from kinetic analyses of three de novo Kemp eliminase lineages [19] [20].

The quantitative data reveal distinct functional roles for active-site (Core) and distal (Shell) mutations. Core mutations are the primary drivers of enhanced catalytic efficiency, providing 90 to 1500-fold improvements in kcat/KM across enzyme lineages [19]. In contrast, Shell mutations alone provide minimal catalytic benefits (0-4 fold improvement) [19]. However, in evolved variants containing both mutation types, catalytic efficiency exceeds that of Core variants alone, demonstrating synergistic enhancement [19].

Stability measurements reveal no consistent pattern. Effects on melting temperature (Tm) vary considerably, with mutations conferring stabilization, destabilization, or neutral effects depending on context [19]. This challenges the hypothesis that distal mutations primarily compensate for stability trade-offs introduced by active-site mutations, instead suggesting they are selected specifically for functional enhancement [19].

Structural and Mechanistic Comparisons

Table 2: Structural and Functional Roles of Mutation Types

| Parameter | Core Mutations | Shell Mutations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Effect | Preorganized catalytic sites | Facilitated substrate binding and product release |

| Structural Impact | Optimized side-chain conformations | Widened active-site entrance; reorganized surface loops |

| Dynamic Properties | Reduced conformational flexibility at active site | Tuned structural dynamics across protein scaffold |

| Catalytic Step Enhanced | Chemical transformation | Substrate binding and product release |

| Contribution to Efficiency | Major driver (90-1500 fold) | Synergistic enhancer (1.2-2 fold over Core alone) |

X-ray crystallography and molecular dynamics simulations reveal distinct structural mechanisms for Core and Shell mutations [19]. Core mutations create preorganized active sites with catalytic residues adopting nearly identical side-chain conformations regardless of ligand binding [19]. This preorganization optimizes the enzyme for the chemical transformation step.

Shell mutations enhance catalysis through altered structural dynamics that widen the active-site entrance and reorganize surface loops, facilitating substrate binding and product release without substantially changing the backbone conformation [19]. These dynamic modifications optimize different steps of the catalytic cycle compared to Core mutations, explaining their synergistic effect when combined.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Mutational Effects

Kinetic Characterization Protocol

Enzyme Kinetics Assay for Kemp Elimination

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), supplemented with 100 mM NaCl and 10% methanol [19]

- Temperature: 27°C [19]

- Substrates: 5-nitrobenzisoxazole (HG3 and KE70 series) or 6-nitrobenzisoxazole (1A53 series) [19]

- Parameter Determination:

- For enzymes reaching saturation: Michaelis-Menten parameters (KM and kcat) determined from nonlinear regression

- For enzymes not reaching saturation (N.D. in Table 1): kcat/KM determined from the slope of the linear portion of Michaelis-Menten plot where [S] << KM [19]

- Replication: Average of six or nine individual measurements from two or three independent protein batches [19]

Structural Biology Workflow

X-ray Crystallography Protocol

- Crystallization: Sparse matrix screening under different conditions for each variant [19]

- Ligand Complexes: Co-crystallization with transition-state analogue 6-nitrobenzotriazole (6NBT) [19]

- Data Collection: Resolution ranging from 1.44 to 2.36 Å [19]

- Structure Determination: Molecular replacement using parent structures

- Analysis: Comparison of backbone conformations and side-chain orientations between bound and unbound structures [19]

Computational Assessment Methods

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

- System Preparation: Structures solvated in explicit water with appropriate ions

- Simulation Length: Sufficient for convergence of conformational sampling [19]

- Analysis:

- Active-site entrance dimensions

- Loop conformational sampling

- Residue fluctuation profiles

- Distance measurements between key residues [19]

Stability Prediction with BoostMut

- Primary Filter: Initial mutation selection using predictors like FoldX or Rosetta [21]

- MD Simulations: Production runs for wild-type and mutant structures [21]

- Biophysical Metrics:

- Hydrogen bond network changes (intramolecular and unsatisfied bonds)

- Protein flexibility alterations

- Solvent-exposed hydrophobic surface area [21]

- Scoring: Comparison of mutant vs. wild-type metrics across local and global protein environments [21]

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for analyzing mutational effects illustrating the integrated approach combining enzyme engineering, kinetic characterization, structural biology, and computational simulations [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme Engineering Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| 6-Nitrobenzotriazole (6NBT) | Transition-state analogue | Mapping active-site structure in crystallography studies [19] |

| 5-Nitrobenzisoxazole | Kemp elimination substrate | Kinetic assays for HG3 and KE70 enzyme variants [19] |

| 6-Nitrobenzisoxazole | Alternative substrate | Kinetic characterization of 1A53 enzyme series [19] |

| MES Buffer | Crystallization component | Identified as active-site binder in structural studies [19] |

| BoostMut Algorithm | Computational stability filter | Automated analysis of MD trajectories for mutation effects [21] |

| QresFEP-2 Protocol | Free energy perturbation | Quantifying mutational effects on stability and binding [22] |

This comparison guide demonstrates that distal and active-site mutations enhance catalytic efficiency through distinct yet complementary mechanisms. While active-site mutations are the primary drivers of catalytic improvement by preorganizing the catalytic apparatus, distal mutations facilitate the complete catalytic cycle by tuning structural dynamics to optimize substrate binding and product release. Stability effects are variable and context-dependent, challenging simplistic compensatory models. Successful enzyme engineering strategies must therefore incorporate both mutation types, employing integrated experimental-computational workflows to balance the competing demands of precise active-site organization and dynamic flexibility throughout the protein scaffold. These insights provide a benchmark for future enzyme engineering campaigns across biocatalysis and therapeutic development.

In the field of enzyme engineering and mutant characterization, stability is a pivotal trait determining industrial applicability. Traditional single-method approaches often fail to capture the complex molecular networks underlying stability mechanisms. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics has emerged as a powerful methodological framework that simultaneously probes gene expression dynamics and metabolic flux changes, providing unprecedented insights into stability mechanisms in mutant strains [23]. This approach enables researchers to connect genetic alterations with their functional metabolic consequences, revealing how mutations influence protein folding, stress response pathways, and cellular homeostasis mechanisms that collectively determine stability phenotypes [24] [17].

The application of multi-omics in mutant stability research represents a paradigm shift from descriptive observation to mechanistic understanding. By correlating differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs), researchers can construct comprehensive regulatory networks that elucidate how mutations translate into stability traits through coordinated molecular changes [25]. This guide systematically compares experimental designs, analytical approaches, and methodological considerations for employing transcriptomic-metabolomic integration in mutant stability research, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these techniques in their enzyme engineering programs.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics Studies on Mutant Stability

Table 1: Comparative analysis of multi-omics studies investigating stability mechanisms in mutants

| Study System | Mutation Type | Key Transcriptomic Findings | Key Metabolomic Findings | Integrated Stability Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trichoderma reesei β-glucanase mutant [17] | ARTP mutagenesis | 1,793 DEGs; upregulation of hemicellulose hydrolases, trehalase, GABA aminotransferase, PEP carboxykinase | Increased palmitic acid and linolenate; altered energy metabolism | Enhanced enzymatic stability linked to membrane composition remodeling and energy metabolism optimization |

| Rice rel1-D mutant (heat tolerance) [24] | T-DNA insertion | 1,184 DEGs enriched in phenylalanine and flavonoid biosynthetic pathways; upregulation of OsCHI, OsF3H, OsFLS, OsCHS, OsPAL, Os4CL | 126 DAMs; elevated flavonoid compounds | Flavonoid-mediated antioxidant system enhancement conferring thermal stability |

| Taxus cuspidata yellow leaf mutant [26] | Natural variation | Upregulation of F3H, FLS, ZEP, PSY in flavonoid/carotenoid pathways; downregulation of GLK, SGR in chlorophyll synthesis | Increased kaempferol/ quercetin derivatives; reduced tetrapyrrole compounds | Stability of photosynthetic apparatus through balanced pigment metabolism |

| Trifolium ambiguum (cold adaptation) [25] | Environmental adaptation | DEGs enriched in glycerophospholipid metabolism, proline metabolism, plant hormone signaling | DAMs in lipid metabolism, compatible solutes, antioxidant compounds | Membrane fluidity maintenance and osmotic homeostasis under cold stress |

Table 2: Methodological comparison of multi-omics approaches for stability mechanism analysis

| Methodological Aspect | Transcriptomics Component | Metabolomics Component | Integration Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Platform | RNA-Seq (Illumina platforms) | LC-MS/MS (Q-TOF, QQQ), GC-MS, NMR | Cross-omics correlation networks (WGCNA) |

| Data Output | Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) | Differentially abundant metabolites (DAMs) | Gene-metabolite interaction networks |

| Pathway Analysis | KEGG enrichment, GO term analysis | KEGG metabolite pathway mapping | Integrated pathway visualization |

| Key Stability Insights | Regulatory network shifts, stress response genes | Metabolic flux changes, compatible solute accumulation | System-level understanding of stability mechanisms |

| Experimental Design | Time-series sampling during stress exposure | Parallel quenching and extraction | Paired samples for direct correlation |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Analysis of Mutant Stability

Sample Preparation and Quenching Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for generating high-quality multi-omics data that accurately reflects the in vivo state of mutant strains. For transcriptomic analysis, RNA integrity is paramount – samples should exhibit RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) >8.0, with clear 18S and 28S ribosomal bands on electrophoretograms [25]. For metabolomics, rapid quenching of metabolic activity is essential to capture authentic metabolic states. The recommended protocol involves:

Rapid Filtration and Flash Freezing: Cells are rapidly filtered under vacuum and immediately submerged in liquid nitrogen-cooled methanol (-40°C) for instantaneous metabolic quenching [23].

Dual-Phase Extraction: Implementation of methanol:chloroform:water (2:2:1.8 v/v/v) biphasic extraction system for comprehensive coverage of hydrophilic and hydrophobic metabolites [23] [27].

Stable Isotope Tracing: For metabolic flux analysis, use [1-13C]-glucose or other isotopically labeled substrates to track carbon flow through central metabolic pathways [23].

Paired Sampling: Always process identical biological samples for both transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis to enable direct correlation between gene expression and metabolic changes [24] [17].

Analytical Workflow for Integrated Data Acquisition

The integrated multi-omics workflow combines parallel analytical streams that converge during data integration:

Transcriptomics Stream: Total RNA extraction using silica-membrane columns, followed by library preparation with poly-A enrichment or rRNA depletion. Sequencing on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq, HiSeq) to achieve minimum depth of 20 million reads per sample with Q30 scores >96.9% [25] [26].

Metabolomics Stream: Metabolite separation using HILIC and reversed-phase chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry (Orbitrap, TOF) for untargeted analysis, and triple quadrupole instruments for targeted quantification [23] [27].

Quality Control: Implement systematic quality control including poolede quality control samples, internal standards (isotopically labeled compounds), and process blanks to monitor technical variability [27].

Data Preprocessing: Transcriptomic data processed through fastp for adapter trimming and quality filtering, followed by alignment with HISAT2 and quantification with featureCounts. Metabolomic data processed using XCMS for peak picking, CAMERA for annotation, and in-house databases for metabolite identification [26].

Analytical Approaches for Data Integration and Interpretation

Bioinformatics Pipelines for Multi-Omics Data Integration

The true power of multi-omics approaches lies in sophisticated data integration strategies that extract biologically meaningful insights from complex datasets. The recommended analytical workflow includes:

Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): Constructs gene-metabolite correlation networks to identify functional modules associated with stability traits. As demonstrated in Trifolium ambiguum cold adaptation studies, WGCNA can identify key modules (e.g., "pink module" associated with lipid metabolism and "black module" linked to hormone signaling) that coordinately respond to stress conditions [25].

KEGG Pathway Enrichment Mapping: Joint mapping of DEGs and DAMs onto KEGG pathways reveals consistently perturbed metabolic and regulatory pathways. In rice rel1-D mutants, this approach demonstrated coordinated enrichment in phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis pathways, indicating their importance for thermal stability [24].

Correlation Network Construction: Calculation of Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients between gene expression levels and metabolite abundances identifies putative regulatory relationships. Strong correlations between transcription factors and metabolite levels can suggest direct regulatory interactions relevant to stability mechanisms [26].

Multivariate Statistical Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) performed on combined transcriptomic and metabolomic datasets to visualize systemic differences between mutant and wild-type strains [17].

Interpretation of Stability Mechanisms from Integrated Data

Translating integrated omics data into mechanistic understanding requires careful biological contextualization. Key interpretation principles include:

Identify Consistently Regulated Pathways: Genuine stability mechanisms typically manifest as coordinated changes at both transcriptional and metabolic levels within the same biological pathways. For example, in Trichoderma reesei mutants with enhanced β-glucanase stability, transcriptomic upregulation of trehalase genes coupled with increased trehalose metabolites suggests osmotic adaptation as a stability mechanism [17].

Distinguish Direct and Compensatory Effects: Some molecular changes represent direct consequences of mutations, while others reflect compensatory adaptations. Temporal multi-omics sampling across different stress durations helps distinguish these effects, as demonstrated in Trifolium ambiguum cold stress time courses [25].

Differentiate Stability Mechanisms from General Stress Responses: Compare mutant responses with wild-type stress responses to identify mechanisms specifically associated with stability traits rather than general stress adaptation [24].

Validate Key Findings: Use targeted approaches (qRT-PCR, enzyme assays, metabolite quantification) to confirm central hypotheses generated from integrated omics data [26].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Stability Studies

Table 3: Essential research reagents and platforms for multi-omics analysis of mutant stability

| Reagent Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Application in Stability Studies | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Sequencing Kits | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA, NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA | Library preparation for transcriptome profiling | Maintain strand specificity for accurate transcript quantification |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA Nano Kit, Qubit RNA HS Assay | RNA integrity verification before sequencing | RIN >8.0 required for high-quality data |

| Metabolite Extraction | Methanol:chloroform:water (2:2:1.8), 80% methanol -20°C | Comprehensive metabolite extraction | Biphasic system for polar/non-polar coverage |

| Chromatography Columns | HILIC (e.g., Acquity UPLC BEH Amide), C18 reversed-phase | Metabolite separation prior to MS detection | HILIC for polar, C18 for non-polar metabolites |

| Mass Spectrometry Platforms | Q-Exactive HF Orbitrap (untargeted), QQQ (targeted) | Metabolite detection and quantification | High-resolution for discovery, triple quad for validation |

| Stable Isotope Tracers | [1-13C]-glucose, [U-13C]-glutamine, 15N-ammonium chloride | Metabolic flux analysis | Enables determination of pathway activities |

| Bioinformatics Tools | XCMS, MetaboAnalyst, WGCNA, KEGG Mapper | Data processing and pathway analysis | Critical for integrated data interpretation |

Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics provides a powerful methodological framework for deciphering the complex molecular networks underlying stability mechanisms in mutant strains. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that despite diversity in biological systems and mutation types, common stability mechanisms emerge across studies, including remodeling of membrane composition, enhancement of antioxidant systems, accumulation of protective metabolites, and optimization of energy metabolism.

Future developments in multi-omics technologies will further enhance our ability to investigate mutant stability mechanisms. Spatial metabolomics techniques such as MALDI-MSI and DESI-MSI will enable correlation of metabolic changes with tissue or subcellular localization [23]. Single-cell multi-omics approaches will reveal heterogeneity in stability responses within populations. Advanced computational methods, particularly artificial intelligence and machine learning applications, will improve prediction of stability traits from integrated omics data [28].

The continued refinement of multi-omics integration methodologies will accelerate the engineering of industrial enzymes and mutant strains with enhanced stability properties, ultimately contributing to more efficient biotechnological processes and therapeutic development. By providing both a comparative framework and practical methodological guidance, this review enables researchers to effectively implement these powerful approaches in their mutant characterization and engineering programs.

Advanced Methodologies for Stability Assessment: From Bench to Silicon

In the field of enzyme engineering and mutant characterization, researchers require robust methods to detect subtle changes in protein conformation and stability. Energetics-based proteomic profiling techniques have emerged as powerful tools for quantifying these changes on a proteome-wide scale, moving beyond simple abundance measurements to assess functional protein states. Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP), Stability of Proteins from Rates of Oxidation (SPROX), and Limited Proteolysis (LiP) represent three complementary approaches that probe different aspects of protein structural stability. These methods enable the comprehensive characterization of enzyme mutants by detecting alterations in thermal stability, resistance to chemical denaturation, and protease accessibility. By applying these techniques, researchers can benchmark enzyme stability across different mutant libraries, identify structural consequences of point mutations, and elucidate structure-function relationships that inform protein engineering efforts. The integration of these approaches provides a multi-dimensional view of protein energetics, offering unique insights into mutant-specific stability profiles that are crucial for advancing biotechnological and therapeutic applications.

Methodological Principles and Technical Specifications

Fundamental Mechanisms and Detection Strategies

Each profiling technique operates on distinct biophysical principles to probe protein stability and conformational changes:

Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP): This method monitors protein thermal stability by measuring the temperature-dependent unfolding and aggregation of proteins. The core principle relies on the fact that proteins denature and become insoluble when heated to their melting temperature (Tm). When a ligand, drug, or mutation stabilizes a protein, it typically increases the Tm value, shifting the denaturation curve to higher temperatures. In practice, samples are heated to a range of temperatures (typically 8-12 points), followed by separation of soluble and insoluble fractions. The soluble fraction is then analyzed via quantitative mass spectrometry to generate melting curves for thousands of proteins simultaneously [29] [30].

Stability of Proteins from Rates of Oxidation (SPROX): SPROX utilizes chemical denaturation coupled with methionine oxidation kinetics to probe protein folding states. The technique exploits the fact that methionine residues in unfolded protein regions are more susceptible to oxidation than those in structurally protected folded regions. Samples are exposed to increasing concentrations of a chemical denaturant (e.g., guanidine hydrochloride), followed by hydrogen peroxide treatment to oxidize exposed methionine residues. The extent of oxidation is quantified via mass spectrometry, generating denaturation curves that reflect protein folding stability [31] [32].

Limited Proteolysis (LiP): LiP assesses protein structural alterations through differential protease accessibility. The core premise is that proteinase K preferentially cleaves unstructured regions or flexible loops of native proteins, while structured domains remain protected. Conformational changes induced by mutations, ligand binding, or post-translational modifications alter this protease accessibility pattern. Following brief proteinase K treatment, proteins are digested to completion with trypsin, and the resulting semi-tryptic peptides are analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify structural changes [33] [34] [35].

Comparative Technical Specifications

Table 1: Technical comparison of TPP, SPROX, and LiP methodologies

| Parameter | TPP | SPROX | LiP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability Probe | Temperature | Chemical denaturant | Protease accessibility |

| Primary Readout | Solubility after heating | Methionine oxidation rate | Proteolytic cleavage patterns |

| Key Measurement | Melting temperature (Tm) | Denaturation midpoint (C1/2) | Structural peptide ratios |

| Throughput | High (16-18 plex TMT) | Moderate | High (DIA or TMT) |

| Proteome Coverage | ~7,000 proteins | ~2,500 proteins | ~5,000 proteins |

| Sample Requirements | Cell lysates, intact cells, tissues | Cell lysates, tissues | Cell lysates, intact cells, physiological fluids |

| Detection Capability | Global stability changes, direct binding | Ligand binding, folding stability | Conformational changes, allostery |

| Key Limitations | Temperature range critical | Limited to Met-containing peptides | Protease optimization needed |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Thermal Proteome Profiling (TPP) Workflow

Diagram Title: TPP Experimental Workflow

The TPP protocol begins with sample preparation using cell lysates or intact cells, which are treated with the compound of interest versus vehicle control. The samples are aliquoted into multiple tubes and heated at different temperatures (typically spanning 37-67°C) for 3 minutes, followed by incubation at room temperature for 3 minutes. After heating, samples are centrifuged to separate soluble proteins from denatured aggregates. The soluble fractions are then digested with trypsin and labeled with tandem mass tags (TMT), allowing multiplexed analysis of all temperature points. For the OnePot TPP variant, all temperature-challenged aliquots are physically pooled prior to isobaric labeling, reducing ratio compression effects. Labeled samples are combined and analyzed via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods. The resulting data is processed using specialized statistical tools such as MSstatsTMT or NPARC to generate melting curves and identify significant thermal shifts [29] [30].

SPROX Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: SPROX Experimental Workflow

The SPROX protocol involves preparing protein extracts and distributing them across a series of increasing chemical denaturant concentrations (typically guanidine hydrochloride). After incubation to allow denaturation equilibrium, methionine oxidation is induced using hydrogen peroxide, with the reaction terminated by adding excess methionine. Proteins are then precipitated, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The key measurement is the quantification of methionine-containing peptides across the denaturant series, generating oxidation curves that reflect the protein's unfolding transition. Data analysis focuses on identifying significant shifts in these denaturation curves between experimental conditions, indicating changes in protein folding stability due to ligand binding or mutations [31] [32].

Limited Proteolysis (LiP) Workflow

Diagram Title: LiP-MS Experimental Workflow

The LiP-MS workflow begins with native protein extracts or intact cells under non-denaturing conditions. Samples undergo limited proteolysis with proteinase K for a short duration (typically 30 seconds to 10 minutes), carefully controlled to ensure partial digestion that reflects native protein structure. The reaction is stopped by heat inactivation at 95°C, followed by complete digestion with trypsin to generate peptides for MS analysis. The resulting peptide mixtures are analyzed via LC-MS/MS using either data-independent acquisition (DIA) or tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling. Critical to the analysis is the identification of semi-tryptic peptides (peptides with only one tryptic terminus) that indicate proteinase K cleavage sites. These structural peptides are quantified and statistically analyzed using tools like LiPAnalyzeR to identify protein structural alterations between conditions [33] [34] [35].

Comparative Performance Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance benchmarking of TPP, SPROX, and LiP in drug target identification

| Performance Metric | TPP | SPROX | LiP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Proteins Quantified | 6,000-7,000 | 2,000-2,500 | 4,000-5,000 |

| Coefficient of Variation | <15% (with TMT) | 15-20% | 10-15% (DIA) |

| Sensitivity for Known Binders | 80-90% | 70-80% | 75-85% |

| Dose-Response Correlation | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| False Positive Rate | 5-10% | 10-15% | 5-10% |

| Throughput (Samples/Week) | 20-30 | 15-20 | 25-35 |

| Biological Replicate Requirements | 3-4 | 3-4 | 2-3 |

Recent benchmarking studies have revealed critical differences in method performance. In LiP-MS comparisons, TMT labeling enabled quantification of more peptides and proteins with lower coefficients of variation, while DIA-MS exhibited greater accuracy in identifying true drug targets and stronger dose-response correlations. Specifically, LiP with DIA quantification demonstrated superior performance in detecting conformational changes with approximately 30% higher sensitivity for allosteric binders compared to TPP and SPROX. However, TPP with the OnePot approach showed enhanced sensitivity for direct binders, particularly when combined with MS3 quantification to minimize ratio compression [35].

For enzyme stability benchmarking, TPP has proven most effective for detecting global stability changes across mutant libraries, while LiP provides superior resolution for identifying specific structural regions affected by mutations. SPROX offers complementary information, particularly for detecting subtle folding stability changes that might not manifest in thermal denaturation profiles [32].

Applications in Enzyme Mutant Characterization

In practical applications for enzyme engineering, these methods have distinct strengths:

TPP excels at ranking mutant stability, providing quantitative Tm values that correlate well with traditional biochemical stability measurements. The ability to profile thousands of proteins simultaneously also enables detection of off-target effects and global proteome responses to mutations.

SPROX is particularly valuable for detecting binding-induced stabilization, even for low-affinity interactions, making it suitable for characterizing enzyme-cofactor complexes and metal binding sites that are common in engineered enzymes.

LiP provides residue-level resolution of structural changes, enabling mapping of specific regions and domains affected by mutations. This spatial information is invaluable for understanding structure-function relationships and guiding iterative protein engineering.

A comparative study applying all three techniques to hippocampus tissue lysates demonstrated their complementarity, with each method identifying unique sets of stabilized and destabilized proteins, highlighting the value of multi-method approaches for comprehensive stability assessment [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and resources for experimental profiling

| Reagent/Resource | Application | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) | TPP, LiP | Multiplexed sample labeling | 16-18 plex available, ratio compression concerns |

| Proteinase K | LiP | Limited proteolysis | Concentration and time optimization critical |

| Guanidine HCl | SPROX | Chemical denaturation | High-purity grade required for consistent results |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | SPROX | Methionine oxidation | Fresh preparation essential for reproducibility |

| MSstatsTMT R Package | TPP | Statistical analysis | Handles complex designs, no curve fitting required |

| LiPAnalyzeR | LiP | Statistical framework | Removes unwanted variation, infers structural changes |

| Orbitrap Astral Mass Spectrometer | All methods | High-sensitivity detection | Improves proteome coverage, reduces labeling need |

| FragPipe Software | DIA Analysis | Open-source data processing | Balance of precision and sensitivity |

Implementation Guidelines for Enzyme Stability Benchmarking

Method Selection Framework

Choosing the appropriate method for enzyme mutant characterization depends on several factors:

For high-throughput stability ranking of mutant libraries, TPP with OnePot design provides the most efficient approach, especially when combined with TMTpro 16-plex labeling. This enables parallel assessment of multiple mutants under identical conditions.

For identifying structural mechanisms behind stability changes, LiP-MS offers superior resolution, particularly when mapping mutation-induced conformational alterations to specific protein domains.

For detecting subtle folding changes that may not involve major structural rearrangements, SPROX provides sensitive detection of stability changes, especially for metal-binding enzymes or those requiring cofactors.

For comprehensive characterization, employing all three methods in a complementary manner delivers the most complete stability assessment, as demonstrated in studies of aging-related stability changes in brain proteomes [32].

Experimental Design Considerations

Successful implementation requires careful experimental planning:

Biological replication: A minimum of 3-4 biological replicates is essential for all methods to ensure statistical robustness, with recent studies emphasizing that additional replicates provide more power than increased temperature points in TPP [29] [30].

Temperature range optimization: For TPP, preliminary experiments should verify that the chosen temperature range captures the full melting transition for proteins of interest, typically spanning 37-67°C for most eukaryotic proteomes.

Denaturant concentration range: For SPROX, an appropriate denaturant gradient (typically 0-4 M guanidine HCl) must be established to properly capture unfolding transitions.

Protease concentration and time: For LiP, proteinase K concentration and digestion time must be optimized to achieve partial proteolysis (5-15% digestion) that reflects native structure.

Recent advances in mass spectrometry instrumentation, particularly the introduction of the Orbitrap Astral platform, have significantly improved the sensitivity and coverage of all three methods, potentially reducing the reliance on TMT labeling for sufficient quantification depth [35].

Thermal Proteome Profiling, SPROX, and Limited Proteolysis represent three powerful, complementary approaches for benchmarking enzyme stability across mutant libraries. Each method provides unique insights into protein energetics—TPP through thermal denaturation, SPROX via chemical denaturation, and LiP via structural accessibility. The integration of these approaches enables comprehensive characterization of mutant enzymes, from global stability rankings to residue-level structural mechanisms. As mass spectrometry technology continues to advance, these methods will play an increasingly important role in rational protein engineering and drug discovery, providing the quantitative stability data needed to decode sequence-structure-function relationships across the proteome.

The pursuit of enzyme variants with enhanced thermal stability and catalytic activity is a central goal in industrial biotechnology, yet it is often hindered by the profound complexity of protein sequence-structure-function relationships. Traditional methods face significant challenges in efficiently exploring the vast mutational space, particularly due to non-additive epistatic interactions that make the effects of combined mutations unpredictable [36]. The emergence of sophisticated machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) models is revolutionizing this field. This guide provides an objective comparison of three advanced computational strategies—iCASE, VenusREM, and Segment Transformer—benchmarked within the context of enzyme stability research. These models represent a paradigm shift from traditional directed evolution, offering data-driven solutions to navigate the combinatorial mutational landscape and accelerate the development of industrially robust biocatalysts [3].

At a Glance: Model Comparison

The table below summarizes the core architectures, strengths, and experimental validation of the three models.

Table 1: Overview of iCASE, VenusREM, and Segment Transformer Models

| Feature | iCASE | VenusREM | Segment Transformer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Structure-based supervised ML; conformational dynamics [11] | Retrieval-enhanced Protein Language Model (PLM) integrating sequence, structure, and evolutionary data [37] | Segment-level sequence representation focusing on unequal regional contributions to stability [38] |

| Key Innovation | Hierarchical modular networks; Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI) [11] | Disentangled multi-head cross-attention; plug-and-play evolutionary representations [37] | Segmented sequence analysis to capture regional thermal properties [38] |

| Handling of Epistasis | Explicitly models epistasis through dynamic response predictive model [11] | Captures implicit co-evolutionary patterns and amino acid interactions [37] | Not explicitly stated |

| Experimental Validation | Protein-glutaminase, Xylanase; 1.42 to 3.39-fold activity increase; ΔTm up to 2.4°C [11] | VHH antibody, Phi29 DNAP; state-of-the-art on ProteinGym benchmark (217 assays) [37] | Cutinase; 1.64-fold improvement in relative activity post-heat treatment [38] |

| Reported Performance | Robust performance across different datasets; reliable epistasis prediction [11] | Superior performance in predicting stability, activity, and binding affinity [37] | RMSE: 24.03; MAE: 18.09; Pearson correlation: 0.33 [38] |

Model Architectures and Methodologies

iCASE (Isothermal Compressibility-Assisted Dynamic Squeezing Index Perturbation Engineering)

The iCASE strategy is a machine learning-based framework designed to overcome the stability-activity trade-off in enzyme evolution [11]. Its methodology involves:

- Hierarchical Modular Network Construction: The enzyme structure is decomposed into hierarchical modules—secondary structures, super-secondary structures, and domains. This allows for targeted engineering based on the enzyme's structural complexity [11].

- Identification of High-Fluctuation Regions: Molecular dynamics simulations are used to calculate the isothermal compressibility (βT) of these modules, identifying regions with high conformational flexibility that are critical for stability and function [11].

- Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI): A key metric, DSI, is calculated and coupled with the enzyme's active center. Residues with a DSI > 0.8 (top 20%) are selected as candidate mutation sites to improve activity [11].

- Energetic and Fitness Prediction: The free energy change of proposed mutations (ΔΔG) is predicted using tools like Rosetta. A dynamic response predictive model, trained on structural data, then forecasts enzyme fitness and epistatic interactions to select optimal mutants for experimental testing [11].

VenusREM (Retrieval-Enhanced Protein Language Model)

VenusREM distinguishes itself through its comprehensive integration of multimodal protein information [37]. Its workflow consists of:

- Multi-Modal Input and Tokenization: The model accepts three sets of inputs:

- Sequence: Tokenized directly into a vocabulary of 20 standard amino acids.

- Structure: Local structures are encoded as graphs and processed by a Geometric Vector Perceptron (GVP) autoencoder, then mapped to a discrete 2048-dimensional codebook.

- Evolutionary Information: Homologous sequences are retrieved from databases based on sequence and structural similarity to the target protein [37].

- Disentangled Multi-Head Cross-Attention: This core architectural component unifies the tokenized sequence and structural features, learning a native representation of the protein that captures both sequence context and spatial constraints [37].

- Plug-and-Play Evolutionary Integration: The retrieved homologous sequences are processed through an alignment tokenization module and integrated into the fitness evaluation without requiring additional model training, providing a flexible and powerful incorporation of evolutionary data [37].

Segment Transformer

The Segment Transformer model is predicated on the biological observation that different regions of a protein sequence contribute unequally to its thermal behavior [38]. Its methodology includes:

- Segmented Sequence Analysis: Instead of processing the entire enzyme sequence as a whole, the model breaks it down into smaller segments. This allows it to focus on and identify specific regions that are disproportionately important for thermal stability [38].

- Deep Learning Framework: A transformer-based architecture is then applied to these segments to learn their representations and predict the overall temperature stability of the enzyme [38].

- Curated Dataset: The model was developed using a specially curated temperature stability dataset designed to address common challenges of data limitation and imbalanced distributions in the field [38].

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking

Key Experimental Workflows

The experimental validation of computational predictions is crucial. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow common to enzyme engineering projects, integrating both computational and wet-lab stages.

Diagram 1: Generalized Enzyme Engineering Workflow

Performance Metrics and Comparative Data

The table below consolidates key quantitative results from studies that applied these models to engineer specific enzymes, providing a basis for cross-model performance comparison.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for Engineered Enzymes

| Enzyme | Model Used | Key Mutations | Activity Improvement | Thermal Stability Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-glutaminase (PG) [11] | iCASE | H47L, M49E, M49L | 1.42-fold to 1.82-fold specific activity | Slight increase |

| Xylanase (XY) [11] | iCASE | R77F/E145M/T284R | 3.39-fold specific activity | ΔTm +2.4 °C |

| Creatinase [36] | Pro-PRIME (Comparable PLM) | 13M4 (13 mutations) | Near full catalytic activity retained | ΔTm +10.19 °C; ~655x half-life at 58°C |

| Cutinase [38] | Segment Transformer | 17 mutations | 1.64-fold relative activity after heat treatment | Not Compromised |

| Phi29 DNA Polymerase [37] | VenusREM | Not specified | Enhanced activity at elevated temperatures | Validated |

Successful AI-driven enzyme engineering relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Enzyme Engineering

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosetta [11] | Software Suite | Predicts free energy changes (ΔΔG) upon mutation. | Used in iCASE for initial mutant filtering. |

| ProteinGym [37] | Benchmark Dataset | A collection of 217 Deep Mutation Scanning (DMS) assays for model benchmarking. | Used to validate VenusREM's general prediction performance. |

| BRENDA [3] | Database | Manually curated enzyme function and property database, including optimal temperatures. | Source of high-quality experimental data for training and validation. |

| ThermoMutDB [3] | Database | Manually collected thermodynamic data (Tm, ΔΔG) for protein mutants. | Provides reliable ground-truth data for stability prediction models. |

| Geometric Vector Perceptron (GVP) [37] | Neural Network | A module for processing 3D structural data (e.g., atom coordinates, residues). | Core to VenusREM's structure tokenization pipeline. |

The integration of AI and machine learning into enzyme engineering represents a transformative advancement for the field. iCASE, VenusREM, and Segment Transformer each offer distinct and powerful approaches to tackling the perennial challenge of predicting mutational effects, especially complex epistasis. iCASE provides deep, dynamics-driven structural insights, VenusREM offers a robust and holistic integration of multimodal data, and Segment Transformer presents a novel, region-focused sequence analysis. Their successful experimental validation across diverse enzymes underscores their potential to drastically reduce the time and cost associated with developing industrial biocatalysts. As these tools continue to evolve and integrate, they will form an indispensable part of the molecular biologist's toolkit, pushing the boundaries of what is achievable in protein design and synthetic biology.

Leveraging Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations with Tools like BoostMut for Automated Stability Analysis

In enzyme engineering, thermostability is a critical goal for developing effective biocatalysts and biomedicines. Despite significant advances in predictive algorithms, reliably identifying stabilizing mutations remains a formidable challenge. A persistent issue in the field is the systematic outperformance of destabilizing mutation prediction compared to stabilizing mutation prediction. For instance, the widely used FoldX tool correctly identifies destabilizing mutations approximately 69% of the time but achieves a success rate of only ~29% for stabilizing mutations [21]. Even state-of-the-art machine learning predictors have struggled to surpass a 44% success rate for stabilizing mutations [21]. This performance gap stems from inherent biases in stability datasets, where destabilizing mutations are significantly overrepresented, and from the complex biophysical trade-offs involved in stabilization [39].

To address these limitations, researchers have increasingly turned to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations as a secondary filter to improve the success rate of mutations pre-selected by thermostability algorithms. However, traditional approaches relying on visual inspection of MD simulations suffer from low throughput, subjectivity, and limited reproducibility [40] [21]. This comparison guide examines how automated computational tools, particularly BoostMut, are transforming this process by standardizing and enhancing the analysis of MD simulations for enzyme stability benchmarking.

Tool Comparison: BoostMut Versus Alternative Approaches

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Protein Stability Analysis Tools

| Tool/Method | Primary Approach | Automation Level | Key Metrics | Reported Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BoostMut | MD simulation analysis with biophysical metrics | Fully automated | Hydrogen bonding, unsatisfied donors/acceptors, flexibility, hydrophobic exposure | 46% (experimentally validated on limonene epoxide hydrolase) [21] |

| Visual Inspection (Traditional) | Manual assessment of MD trajectories | Low (subjective) | Structural visualization experience-dependent | Lower than BoostMut (specific mutations overlooked) [21] |

| iCASE Strategy | Machine learning with dynamics squeezing index | Semi-automated | Isothermal compressibility, dynamic squeezing index, free energy changes | Improved activity & stability (1.42-3.39x activity increase, ΔTm +2.4°C) [11] |

| FRESCO | FoldX/Rosetta with MD and visual inspection | Semi-automated | Energy calculations, structural dynamics | Achieved ΔTm +51°C in 10-fold mutant [21] |

| Cartesian ΔΔG | Rosetta-based free energy calculations | Fully automated | Cartesian space relaxation, energy assessments | Varies by mutation type (improved with benchmark adjustments) [39] |

Table 2: Performance Across Mutation Types

| Tool/Method | Stabilizing Mutations | Destabilizing Mutations | Charged Residue Mutations | Hydrophobic Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BoostMut | 46% success rate [21] | Not specifically reported | Handled via formalized biophysical metrics | Handled via formalized biophysical metrics |

| FoldX | ~29% success rate [21] | ~69% success rate [21] | Historically challenging [39] | Better performance due to dataset bias [39] |

| Traditional Predictors | Generally lower accuracy [21] | Generally higher accuracy [21] | Underrepresented in benchmarks [39] | Overrepresented in benchmarks [39] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

BoostMut Workflow and Implementation

The BoostMut (Biophysical Overview of Optimal Stabilizing Mutations) tool operates as a secondary filter that analyzes structural features from MD simulations of pre-selected mutations [21]. Its experimental protocol follows these key stages:

Mutation Pre-selection: Candidate mutations are first generated using primary predictors (FoldX, Rosetta, or other thermostability algorithms) to narrow down the mutational space [21].

MD Simulation Execution: Short molecular dynamics simulations are run for both wild-type and mutant protein structures. The implementation utilizes the MDAnalysis Python library, which supports various topology and trajectory formats [21].