Beyond Michaelis-Menten: A Practical Guide to Nonlinear Regression for Accurate Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide to nonlinear regression analysis for enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Beyond Michaelis-Menten: A Practical Guide to Nonlinear Regression for Accurate Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to nonlinear regression analysis for enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the fundamental limitations of traditional linearization methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plots) and the statistical superiority of directly fitting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation[citation:1][citation:6]. The core of the guide details methodological workflows, including software implementation with tools like the R package 'renz', and practical application in pharmacokinetic modeling[citation:2][citation:6]. It dedicates significant focus to troubleshooting common pitfalls such as poor initial parameter estimates, error weighting, and experimental design[citation:5]. Finally, the article covers validation techniques through residual analysis and explores advanced comparative frameworks, including modern fractional-order kinetics models that account for memory effects in enzymatic systems[citation:4][citation:8]. The synthesis empowers scientists to obtain more reliable kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) for robust biochemical characterization and drug discovery.

Why Linearization Fails: The Statistical and Practical Imperative for Nonlinear Regression in Enzyme Kinetics

Historical and Conceptual Foundations

The Michaelis-Menten model, proposed in 1913, represents the cornerstone for quantifying enzyme-catalyzed reactions [1]. It provides a mathematical framework describing the rate of product formation as a function of substrate concentration, encapsulating the essential features of enzyme action through two fundamental kinetic parameters: (V{max}) and (Km) [1] [2].

The model is built upon a specific reaction scheme where an enzyme (E) reversibly binds a substrate (S) to form a complex (ES), which then yields product (P) while regenerating the free enzyme [1] [3]:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P

A critical assumption is that the reaction is measured during the steady-state phase, where the concentration of the ES complex remains constant [4] [2]. Under this condition and assuming the total enzyme concentration is much lower than the substrate concentration, the famous Michaelis-Menten equation is derived [1] [4]:

( v = \frac{dP}{dt} = \frac{V{max} [S]}{Km + [S]} = \frac{k{cat} [E]0 [S]}{Km + [S]} )

Here, (v) is the initial velocity, ([S]) is the substrate concentration, and ([E]0) is the total enzyme concentration. (V{max}) is the maximum reaction velocity achieved at saturating substrate levels, and (Km), the Michaelis constant, is the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of (V{max}) [5] [2]. The parameter (k{cat}) (the catalytic constant) represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time, and is related to (V{max}) by (V{max} = k{cat}[E]0) [1].

The strength of this model lies in its ability to describe the transition from first-order kinetics (where (v) is roughly proportional to ([S]) when ([S] << Km)) to zero-order kinetics (where (v) is approximately equal to (V{max}) and independent of ([S]) when ([S] >> K_m)) [1] [2]. This results in the characteristic hyperbolic curve when velocity is plotted against substrate concentration [2].

Beyond its original scope, the Michaelis-Menten formalism has been successfully applied to a wide range of biochemical processes, including antigen-antibody binding, DNA hybridization, and protein-protein interactions [1].

Enzyme Reaction Mechanism and Steady-State

Kinetic Parameters and Their Biochemical Significance

The parameters (Km) and (k{cat}) provide deep insight into enzyme function and efficiency. (Km) is an amalgamated constant, defined as ((k{-1} + k{cat})/k1), and is not a simple dissociation constant for substrate binding, except in the specific case where (k{cat} << k{-1}) [1] [5]. A lower (K_m) value generally indicates a higher apparent affinity of the enzyme for its substrate, as less substrate is required to achieve half-maximal velocity [2].

The parameter (k{cat}), the turnover number, defines the catalytic capacity of the enzyme at saturated substrate levels [1]. However, the most important metric for evaluating an enzyme's catalytic proficiency is often the specificity constant, defined as (k{cat}/Km) [1]. This constant represents the enzyme's efficiency at low substrate concentrations, effectively describing the apparent second-order rate constant for the reaction of free enzyme with free substrate [1]. Enzymes with a high (k{cat}/K_m) ratio are efficient catalysts, as they combine fast turnover with tight substrate binding.

These parameters vary enormously across different enzymes, reflecting their diverse biological roles and catalytic mechanisms [1].

Table 1: Representative Michaelis-Menten Parameters for Various Enzymes [1]

| Enzyme | (K_m) (M) | (k_{cat}) (s⁻¹) | (k{cat}/Km) (M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | (1.5 \times 10^{-2}) | 0.14 | 9.3 |

| Pepsin | (3.0 \times 10^{-4}) | 0.50 | (1.7 \times 10^{3}) |

| tRNA synthetase | (9.0 \times 10^{-4}) | 7.6 | (8.4 \times 10^{3}) |

| Ribonuclease | (7.9 \times 10^{-3}) | (7.9 \times 10^{2}) | (1.0 \times 10^{5}) |

| Carbonic anhydrase | (2.6 \times 10^{-2}) | (4.0 \times 10^{5}) | (1.5 \times 10^{7}) |

| Fumarase | (5.0 \times 10^{-6}) | (8.0 \times 10^{2}) | (1.6 \times 10^{8}) |

From Linearization to Direct Nonlinear Regression

Traditionally, before the widespread availability of computational power, the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation was linearized for analysis using graphical methods like the Lineweaver-Burk plot (double-reciprocal plot of (1/v) vs. (1/[S])) [5] [2]. While useful for visualization and diagnosing inhibition types, these linear transformations distort experimental error structures, making them statistically inferior for accurate parameter estimation [5] [6].

Modern enzyme kinetics relies on nonlinear regression to fit the untransformed velocity data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation [5] [7]. This approach finds the values of (V{max}) and (Km) that minimize the sum of squared differences between the observed velocities and those predicted by the model [7]. This method is statistically more valid as it respects the original error distribution of the data [6]. Software packages (e.g., GraphPad Prism, R) have made this computationally straightforward [5] [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Estimating Michaelis-Menten Parameters

| Method | Plot | Transformation | Key Advantage | Major Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis-Menten | (v) vs. ([S]) | None (Hyperbola) | Direct visualization of kinetics; statistically sound fitting. | Visual estimation of parameters from curve is difficult. |

| Lineweaver-Burk | (1/v) vs. (1/[S]) | Double-reciprocal | Linear plot; easy visualization of inhibition type. | Highly distorts error; poor for accurate parameter estimation [5]. |

| Nonlinear Regression | (v) vs. ([S]) | None (Direct fit) | Most accurate and statistically valid parameter estimation [6] [7]. | Requires computational software. |

Workflow for Modern Michaelis-Menten Analysis

Experimental Protocols and Data Acquisition

Accurate determination of Michaelis-Menten parameters hinges on well-designed experiments.

Core Protocol: Initial Velocity Assay

- Reaction Conditions: Maintain constant temperature, pH, and ionic strength using an appropriate buffer. The total enzyme concentration ([E]0) must be significantly lower than the substrate concentrations used and the (Km) (typically ([E]0 < 0.01 Km)) to satisfy the steady-state assumption [8].

- Substrate Range: Use a minimum of 8-10 substrate concentrations, spaced geometrically (e.g., half-log intervals). The range should ideally bracket the (Km), with the lowest concentration below (Km) and the highest achieving near-saturation (e.g., >5-10x (K_m)) [8].

- Initial Rate Measurement: For each ([S]), initiate the reaction (e.g., by adding enzyme) and monitor product formation or substrate depletion over time. The rate must be measured during the initial linear phase (typically <5% substrate conversion) to ensure ([S]) is essentially constant and product inhibition or reverse reaction is negligible [3].

- Data Fitting: Input substrate concentrations and corresponding initial velocities into nonlinear regression software to solve for (V{max}) and (Km) [5] [7].

Progress Curve Analysis An alternative approach fits the entire time course (progress curve) of product formation to an integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation [8] [9]: ( [P] = [S]0 - Km \cdot W\left(\frac{[S]0}{Km} e^{([S]0 - V{max} \cdot t)/Km}\right) ) or uses the linear transform: ( \ln(\frac{[S]0}{[S]}) + \frac{[S]0-[S]}{Km} = \frac{V{max}}{Km} t ) [9] Where (W) is the Lambert W function, ([S]_0) is initial substrate concentration, and ([S]) is concentration at time (t). This method can extract parameters from a single reaction, using data more efficiently, but requires solving a more complex equation and is sensitive to deviations from the ideal model (e.g., product inhibition) [8] [9].

Advanced Fitting Challenges and Modern Solutions

Despite its widespread use, standard Michaelis-Menten analysis faces significant challenges, prompting the development of advanced methodologies.

1. The High Enzyme Concentration Problem The standard model assumes ([E]0 << [S]) and ([E]0 << Km) [8]. This condition often fails in cellular environments or certain *in vitro* setups. When enzyme concentration is not negligible, the standard quasi-steady-state approximation (sQSSA) underlying the classic equation breaks down, leading to biased parameter estimates [8]. The solution is to use a more robust total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) model, which remains accurate under a much wider range of conditions, including high enzyme concentrations [8]: ( \frac{dP}{dt} = k{cat} \frac{ [E]T + Km + [S]T - P - \sqrt{([E]T + Km + [S]T - P)^2 - 4[E]T([S]T - P)} }{2} ) where ([S]_T) is total substrate. Bayesian inference based on this tQ model yields accurate estimates even when enzyme and substrate concentrations are comparable [8].

2. Parameter Identifiability and Optimal Design Parameters (Km) and (V{max}) are often highly correlated, leading to identifiability issues where different parameter pairs can fit the data equally well [8]. To overcome this, optimal experimental design is crucial:

- For initial velocity assays, ensure substrate concentrations span from below to well above the (unknown) (K_m) [8].

- For progress curve assays, starting ([S]0) near the (Km) is recommended [8].

- Collecting data under multiple conditions (e.g., different enzyme concentrations) and pooling it for a global fit, especially using the tQ model, dramatically improves precision and accuracy [8].

3. Single-Molecule Kinetics and High-Order Moments Single-molecule techniques reveal stochasticity and dynamic heterogeneity masked in bulk assays. The classical Michaelis-Menten equation holds for the mean turnover time ((\langle T \rangle)) at the single-molecule level [10]: ( \langle T \rangle = \frac{1}{k{cat}} + \frac{KM}{k_{cat}[S]} ) Recent breakthroughs show that analyzing higher statistical moments (variance, skewness) of the turnover time distribution yields high-order Michaelis-Menten equations. These provide access to previously hidden kinetic parameters, such as the actual substrate binding rate, the mean lifetime of the enzyme-substrate complex, and the probability that a binding event leads to catalysis [10]. This represents a major generalization of the classic framework.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Reagents | Purified Target Enzyme | The catalyst of interest; source and purity are critical. | Activity, concentration, and stability must be rigorously determined. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. | Purity is essential. Solubility at high concentrations needed for saturation [9]. | |

| Assay Buffer System | Maintains optimal pH and ionic strength for enzyme activity. | Must not interfere with the detection method. Chelating agents may be needed. | |

| Detection Reagents/Probes | Enables quantification of product or substrate (e.g., chromogenic, fluorogenic). | Signal must be linear with concentration change; minimal background. | |

| Data Analysis Software | GraphPad Prism | Commercial software with user-friendly nonlinear regression for enzyme kinetics [5]. | Includes tools for fitting, comparing models, and creating plots. |

R with renz package |

Open-source environment. The dir.MM() function performs direct nonlinear least squares fitting [7]. |

Highly flexible and reproducible, but requires programming knowledge. | |

| Custom Bayesian Inference Scripts (e.g., for tQ model) | For advanced analysis under challenging conditions (high [E], single-molecule data) [8] [10]. | Necessary for pushing beyond the limitations of the standard model. | |

| Experimental Design | Optimal Concentration Calculator | Determines the best range of [S] and [E] to use for robust parameter estimation [8]. | Mitigates parameter identifiability problems before experiments begin. |

Within the framework of enzyme kinetics research, a central task is the accurate determination of the kinetic parameters Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant) from initial velocity data plotted against substrate concentration. The hyperbolic relationship is described by the Michaelis-Menten equation: v = Vmax[S] / (Km + [S]) [4] [1]. Prior to the widespread accessibility of computers, linear transformations of this equation were developed to extract these parameters via simple graphical methods and linear regression [11] [12].

The Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot (1934) graphs 1/v versus 1/[S], yielding a straight line where the y-intercept is 1/Vmax and the slope is Km/Vmax [11]. The Eadie-Hofstee plot (1942, 1952) graphs v versus v/[S], producing a line with a y-intercept of Vmax and a slope of -Km [12].

While these methods revolutionized early enzymology, they introduce significant statistical distortions. The core thesis of modern enzyme kinetics is that nonlinear regression, fitting velocity data directly to the untransformed Michaelis-Menten equation, provides superior accuracy and precision and is now the recommended standard [13] [6] [14]. This guide details the inherent pitfalls of linearization methods and provides protocols for robust, modern analysis.

Mathematical Foundations and Error Propagation

The fundamental flaw of linear transformations lies in their violation of the key assumptions of ordinary least-squares linear regression: that measurement errors are independent, normally distributed, and have constant variance (homoscedasticity) across the range of the independent variable [13].

Lineweaver-Burk Transformation: Taking the reciprocal of both velocity (v) and substrate concentration ([S]) dramatically distorts the error structure. If the original experimental error in v is constant, the error in 1/v becomes larger at low velocities. Consequently, low-substrate, low-velocity data points (which have the largest 1/v values) exert disproportionate leverage on the fitted line, leading to biased parameter estimates [11]. As noted, if v = 1 ± 0.1, then 1/v = 1 ± 0.1 (a 10% error). However, if v = 10 ± 0.1, then 1/v = 0.100 ± 0.001 (only a 1% error) [11].

Eadie-Hofstee Transformation: This plot, represented by the equation v = Vmax - Km(v/[S]), uses v on both axes. This creates a statistical dependency where the experimental error in v appears in both the x-axis (v/[S]) and y-axis variables, violating the assumption of independent measurement errors. This often results in a characteristic non-random pattern of residuals [12] [13].

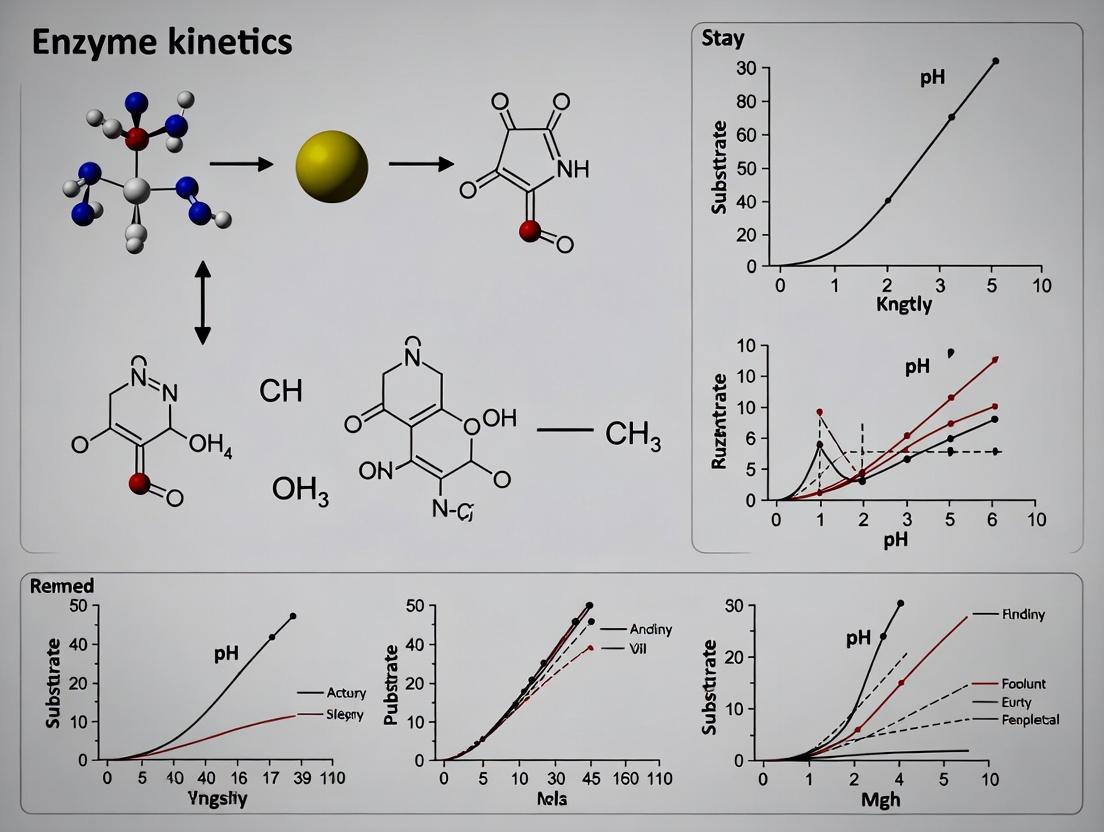

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of traditional linear analysis versus the direct, statistically sound approach of nonlinear regression.

Quantitative Evidence: Simulation Studies on Accuracy and Precision

Empirical evidence from simulation studies conclusively demonstrates the superiority of nonlinear regression. A key 2018 study compared five estimation methods using 1,000 replicates of simulated enzyme kinetic data with defined error structures [13].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Estimation Methods from Simulation Study [13]

| Estimation Method | Key Description | Relative Accuracy & Precision (Rank) | Major Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear [S]-time fit (NM) | Fits substrate depletion over time directly using numerical integration. | Most accurate and precise | Requires full time-course data. |

| Nonlinear v-[S] fit (NL) | Direct nonlinear fit of initial velocity vs. [S] to Michaelis-Menten equation. | Very high | Requires reliable initial velocity measurements. |

| Eadie-Hofstee Plot (EH) | Linear regression of v vs. v/[S]. | Low | Error dependency on both axes; poor error handling. |

| Lineweaver-Burk Plot (LB) | Linear regression of 1/v vs. 1/[S]. | Lowest | Severe error distortion; overweights low-[S] data. |

| Average Rate Method (ND) | Nonlinear fit using average rates between time points. | Moderate | Introduces approximation errors. |

The study found that nonlinear methods (NM and NL) provided the most accurate and precise estimates of Vmax and Km. The superiority was especially pronounced when data incorporated a combined (additive + proportional) error model, a realistic scenario in experimental biochemistry [13]. This confirms that the error structure is decisive, and linear transformations fail to manage it correctly.

Experimental Protocols: From Data Collection to Robust Analysis

Protocol for Generating Initial Velocity Data

This foundational protocol is common to all analysis methods.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing buffer, cofactors, and a fixed, catalytic concentration of enzyme. The enzyme concentration must be significantly lower than the substrate concentrations to maintain steady-state assumptions [4] [1].

- Substrate Dilution Series: Prepare a series of substrate stock solutions, typically spanning a range from ~0.2Km to 5Km or wider.

- Initiating Reactions: In separate reaction vessels (e.g., cuvettes or plate wells), combine the substrate dilutions with the master mix to start the reaction. Use a timer or stopped-flow apparatus for precise initiation.

- Monitoring Product Formation: Measure the increase in product (or decrease in substrate) continuously or at frequent, early time intervals using spectroscopy, fluorescence, or chromatography. The monitored signal must be linearly proportional to concentration.

- Determining Initial Velocity (v): For each substrate concentration, plot product concentration versus time. The initial velocity is the slope of the linear portion of this curve, typically within the first 5-10% of the reaction where [S] ≈ constant and product inhibition is negligible [13]. Use sufficient data points to reliably determine this slope.

Protocol for Nonlinear Regression Analysis (Recommended)

- Data Preparation: Tabulate the measured initial velocity (v) against the corresponding substrate concentration ([S]).

- Software Selection: Use a statistical or graphing package capable of nonlinear least-squares regression (e.g., GraphPad Prism, R, SigmaPlot, NONMEM).

- Model Specification: Input the Michaelis-Menten model: Y = (Vmax * X) / (Km + X), where Y is v and X is [S].

- Weighting (Critical Step): Do not assume equal weighting. Investigate the error structure. If the standard deviation of replicates for v increases with v (a common pattern [15]), apply a weighting factor of 1/Y^2 or 1/variance. Modern software can also fit a proportional error model directly [16].

- Initial Parameter Estimates: Provide rough estimates for Vmax (≈ max observed v) and Km (≈ [S] at half of Vmax) to guide the iterative fitting algorithm.

- Fit and Evaluate: Run the regression. Examine the goodness-of-fit (R², residual plots). The residuals (difference between observed and predicted v) should be randomly scattered, confirming a valid fit [6].

Protocol for Linear Transformations (For Display or Inhibition Diagnostics Only)

Note: Use this protocol only to create plots for visual display or to diagnose inhibition patterns. Do not use the linear regression parameters for quantitative analysis [14].

- Lineweaver-Burk Plot: Calculate 1/v and 1/[S] for each data point. Plot 1/v vs. 1/[S]. A straight line indicates Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Different inhibitor types (competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive) alter the pattern of lines in diagnostic ways [11].

- Eadie-Hofstee Plot: Calculate v/[S] for each data point. Plot v vs. v/[S]. A single straight line indicates Michaelis-Menten kinetics; upward curvature may suggest positive cooperativity, while downward curvature may indicate negative cooperativity or a mixture of enzyme forms [12].

- Visualization, Not Calculation: Superimpose the line derived from your nonlinear regression parameters onto these plots to correctly represent your fit [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Item | Function & Importance | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst under investigation. Source (recombinant, tissue) and purity are critical for reproducible kinetics. | Aliquot and store to prevent freeze-thaw degradation. Verify activity before full experiment. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. Must be of high purity. | Prepare fresh stock solutions. Consider solubility and stability in assay buffer. |

| Cofactors / Cations | Required for the activity of many enzymes (e.g., NADH, Mg²⁺, ATP). | Include at saturating, non-inhibitory concentrations in the master mix. |

| Spectrophotometer / Plate Reader | Instrument to measure product formation or substrate depletion over time. | Must have good signal-to-noise, stable temperature control, and kinetic measurement capability. |

| Statistical Software with Nonlinear Regression | Essential for accurate parameter estimation (e.g., GraphPad Prism, R, NONMEM). | Software must allow for custom model definition and weighting options [13] [6]. |

| Buffer System | Maintains optimal and constant pH for enzyme activity. | Choose a buffer with appropriate pKa and minimal interaction with the enzyme (e.g., Tris, phosphate, HEPES). |

Moving Beyond Simple Michaelis-Menten: Inhibition and Advanced Models

Linear plots remain useful tools for the qualitative diagnosis of enzyme inhibition, as different inhibitor types produce distinct patterns on a Lineweaver-Burk plot [11]. However, for quantitative determination of inhibition constants (Ki), nonlinear regression is again the method of choice.

Modern research extends into more complex models where linearization is infeasible. Examples include analyzing reactions with significant background signal or substrate contamination [6], fitting full time-course data without assuming initial velocity [13], and discriminating between intricate mechanistic models (e.g., competitive vs. non-competitive inhibition) using optimal experimental design [16]. These scenarios absolutely require the flexibility of nonlinear regression.

Table 3: Example Kinetic Parameters for Various Enzymes [1]

| Enzyme | Km (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ |

Note: The specificity constant (kcat/Km) is a measure of catalytic efficiency. Accurate determination of Km and kcat (where Vmax = kcat[E]total) is therefore essential for comparing enzymes.

The historical reliance on Lineweaver-Burk and Eadie-Hofstee plots was born from computational necessity. Contemporary research, framed within a thesis advocating for rigorous data analysis, must acknowledge their severe statistical shortcomings: the distortion of error structures and the resultant biased parameter estimates.

The evidence is clear: nonlinear regression applied directly to untransformed data is the gold standard for accuracy and precision [13] [6]. Best practices for modern enzyme kinetics research are:

- Collect high-quality initial velocity data with appropriate replicates to understand error structure.

- Analyze data via nonlinear least-squares regression, applying appropriate weighting based on the observed error.

- Use linear transformations (Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee, Hanes-Woolf) solely for diagnostic visualization or teaching, never as the primary analytical tool [14].

- For complex systems (inhibition, multi-substrate, progress curve analysis), employ specialized nonlinear models to extract mechanistically meaningful parameters.

By abandoning convenient yet flawed linearizations in favor of statistically sound nonlinear methods, researchers and drug developers ensure that the kinetic parameters fundamental to understanding enzyme mechanism, cellular metabolism, and drug-target interactions are derived with the highest possible fidelity.

Within the broader thesis of nonlinear regression in enzyme kinetics research, the choice of parameter estimation methodology is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental determinant of scientific reliability. Traditional linearizations of the Michaelis-Menten equation, such as the Lineweaver-Burk plot, are historically entrenched but introduce well-documented statistical biases that distort the very kinetic constants (K_m and V_max) researchers seek to measure accurately [17]. This technical guide centers on the paradigm of direct nonlinear fitting of progress curve data—a superior approach that eliminates the need for error-prone transformations and provides a direct path to unbiased parameter estimates and their associated errors [18] [17].

The core thesis posits that for rigorous enzyme kinetics, particularly in applications critical to drug development and diagnostic assay design, direct nonlinear fitting is indispensable. It enables researchers to extract maximum information from costly and time-intensive experiments by utilizing the complete temporal reaction profile, not just initial rates [17]. This guide will detail the theoretical underpinnings of unbiased estimation, provide validated experimental and computational protocols, and demonstrate how this approach provides a more truthful quantification of uncertainty, ultimately leading to more robust scientific conclusions and dependable downstream applications [19].

Theoretical Foundations of Unbiased Estimation

Unbiased parameter estimation is a statistical cornerstone for reliable kinetic modeling. An estimator is deemed unbiased if its expected value equals the true parameter value across repeated experiments. In enzyme kinetics, bias systematically skews constants like K_m, leading to incorrect conclusions about enzyme affinity, inhibitor potency, or catalytic efficiency [19].

Direct nonlinear fitting of the integrated rate equation to progress curve data inherently promotes unbiased estimation when coupled with appropriate algorithms. This is because it operates on the original, untransformed data, preserving the correct statistical weight of each measurement [17]. Conversely, linearization techniques distort the error structure; data points at low substrate concentrations (high reciprocal values) are given excessive weight, systematically biasing the results [17]. Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), often employed in nonlinear regression, provides a framework for asymptotic unbiasedness, meaning bias approaches zero as sample size increases [18] [20].

A critical advancement is the formal distinction and quantification of precision versus accuracy. Precision refers to the reproducibility of an estimate (quantified by standard error, SE), while accuracy denotes its closeness to the true value (quantified by bias) [20]. A common and dangerous pitfall in enzyme kinetics is a highly precise but inaccurate K_m value, where a deceptively small SE from nonlinear regression software masks a significant systematic error caused by factors like inaccurate substrate concentration [19]. The Accuracy Confidence Interval (ACI-Km) framework has been developed specifically to address this by propagating systematic concentration uncertainties into the K_m estimate, providing a more reliable bound for decision-making in research and development [19].

Methodological Comparison: Direct Nonlinear Fitting vs. Alternatives

The analysis of enzyme kinetic progress curves can be approached through multiple computational pathways. A 2025 methodological comparison evaluated two analytical and two numerical approaches, highlighting their distinct operational logics and performance characteristics [17].

- Analytical Approaches rely on the implicit or explicit integral of the Michaelis-Menten rate equation. These methods are mathematically rigorous and computationally fast when applicable. However, their major limitation is inflexibility; they are strictly tied to the specific integrated form of the model and cannot easily accommodate more complex reaction schemes (e.g., reversibility, multi-substrate, or inhibition kinetics) without deriving a new integral solution [17].

- Numerical Approaches offer greater flexibility. The first method involves the direct numerical integration of the differential mass balance equations during the fitting process. This is powerful for complex models but can be computationally intensive and sensitive to the initial parameter guesses provided to the optimization algorithm [17]. The second numerical method, spline interpolation of data, transforms the dynamic problem into an algebraic one. This approach was found to show a lower dependence on the initial parameter estimates, providing robustness and making it highly accessible for researchers [17].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for selecting a progress curve analysis method based on model complexity and the need for robustness against initial guess sensitivity.

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

The choice of methodology has direct, quantifiable impacts on parameter estimation. The following table summarizes key findings from the comparative study of progress curve analysis methods [17].

Table: Comparison of Progress Curve Analysis Methodologies [17]

| Method | Core Principle | Key Strength | Key Limitation | Dependence on Initial Guess |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Integral | Fitting to closed-form solution of ODE. | Computational speed; mathematically exact. | Limited to simple models; requires derived solution. | Low to Moderate |

| Direct Numerical Integration | Solving ODEs numerically during fitting. | High flexibility for complex kinetic models. | Computationally slower; can converge to local minima. | High |

| Spline Interpolation | Transforming dynamic data to algebraic problem. | High robustness; low sensitivity to initial guess. | Requires careful spline fitting to avoid over/under-fitting. | Low |

Experimental Protocols for Reliable Progress Curve Analysis

Implementing direct nonlinear fitting requires careful experimental design and execution to ensure data quality that matches the method's potential.

Protocol: Generating Progress Curve Data forK_mandV_maxDetermination

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the purified enzyme. Independently prepare a series of substrate stock solutions (typically 8-12 concentrations) spanning a range from approximately

0.2*K_mto5*K_m. Use a buffered system appropriate for enzyme activity. Include any necessary cofactors. - Instrument Setup: Use a plate reader or spectrophotometer with precise temperature control (e.g., 30°C or 37°C). Pre-warm the instrument and buffer. Set the monitoring wavelength (e.g., 340 nm for NADH, 405 nm for pNP) and take readings at intervals sufficient to define the curve shape (e.g., every 10-30 seconds for 10-30 minutes).

- Data Acquisition:

- In a multi-well plate or cuvette, add buffer and substrate solution to achieve the desired final substrate concentration in a known total volume.

- Initiate the reaction by adding a small, precise volume of enzyme stock. Mix rapidly and thoroughly.

- Immediately begin monitoring the change in absorbance (or fluorescence) over time.

- Repeat for all substrate concentrations. Run each concentration in at least duplicate.

- Data Pre-processing: Convert raw absorbance to product concentration using the Beer-Lambert law (

εand pathlengthl). Export time (t) and product concentration ([P]) data pairs for each reaction.

Protocol: Direct Nonlinear Fitting via the Integrated Michaelis-Menten Equation

This protocol fits the progress curve directly to the implicit integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation: [S]0 - [S] + K_m * ln([S]0/[S]) = V_max * t. Since [P] = [S]0 - [S], the equation can be expressed in terms of the measured product [P].

- Software Selection: Use scientific data analysis software capable of nonlinear regression (e.g., GraphPad Prism, R with

nls()function, Python with SciPy/Lmfit, or the dedicated ACI-Km web app [19]). - Model Definition: Input the fitting model:

[P] - K_m * ln(1 - [P]/[S]0) = V_max * t. Here,[S]0is a known constant for each curve,[P]is the dependentYvariable,tis the independentXvariable, andK_mandV_maxare the parameters to be fit. - Initial Parameter Estimation:

- For

V_max, estimate from the maximum observed slope of the progress curve. - For

K_m, use an approximate value from literature or preliminary experiments, or start with a value roughly equal to the middle of your substrate concentration range.

- For

- Regression Execution: Perform the nonlinear least-squares fit. Use robustness settings if available (e.g., the spline interpolation method is recommended for its lower initial guess sensitivity [17]).

- Validation & Error Analysis:

- Examine the residuals (difference between observed and fitted data) for randomness. Systematic patterns indicate a poor fit.

- Record the best-fit values for

K_mandV_maxalong with their standard errors (SE) and confidence intervals. - For critical applications, apply the ACI-Km framework to incorporate systematic concentration errors and report an Accuracy Confidence Interval alongside the precision metrics [19].

Advanced Applications: Inferring Hidden Parameters and Machine Learning Approaches

High-Order Michaelis-Menten Analysis for Single-Molecule Kinetics

A frontier in enzyme kinetics is the analysis of stochastic, single-molecule data. A groundbreaking 2025 study derived high-order Michaelis-Menten equations that generalize the classic relationship to moments of any order of the turnover time distribution [10]. This allows inference of previously hidden kinetic parameters from single-molecule trajectories.

Core Principle: While the mean turnover time (⟨T_turn⟩) follows the classic relationship ⟨T_turn⟩ = (1/k_cat) * (1 + K_m/[S]), higher moments contain additional information. The study identified specific, universal combinations of these moments that also depend linearly on 1/[S]. By performing direct nonlinear fitting of these moment combinations against 1/[S], researchers can extract parameters beyond k_cat and K_m [10].

Inferable Hidden Parameters:

- Mean lifetime of the enzyme-substrate complex (

⟨T_ES⟩). - Substrate binding rate constant (

k_on). - Probability that catalysis occurs before substrate unbinding (

P_cat).

This method is robust, requiring only several thousand turnover events per substrate concentration, and works for enzymes with complex, non-Markovian, or branched internal mechanisms [10]. The workflow for this advanced analysis is depicted below.

Machine Learning as a Comparative Approach

In parallel, artificial neural networks (ANNs) have emerged as a powerful, data-driven tool for modeling nonlinear biochemical reaction systems. A 2025 study demonstrated that a Backpropagation Levenberg-Marquardt ANN (BLM-ANN) could accurately model Michaelis-Menten kinetics defined by ODEs, achieving remarkably low mean squared error (MSE as low as 10^{-13}) [21].

Key Insight for Kinetics Researchers: While ANNs are exceptionally flexible "function approximators" and can handle complex, irreversible reactions without a priori model specification, they differ fundamentally from direct nonlinear fitting [21]. ANNs are agnostic to mechanism; they learn an input-output mapping from data but do not provide directly interpretable kinetic parameters like K_m and V_max unless specifically designed to do so. Their primary advantage is in predictive modeling and simulation when the underlying mechanistic model is unknown or excessively complex. For standard enzyme characterization where the goal is to estimate and interpret specific kinetic constants, direct nonlinear fitting of a mechanistic model remains the more appropriate and transparent choice.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Role | Critical Specification for Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst under investigation. | Purity (>95%), known specific activity, stable storage buffer to prevent denaturation. |

| Substrate | The molecule transformed by the enzyme. | High chemical purity, verified solubility in assay buffer, accurate molecular weight for molarity calculation. |

| Buffer Components | Maintains constant pH and ionic environment. | pKa suitable for target pH, non-inhibitory to enzyme, consistent preparation. |

| Detection Reagent | Allows monitoring of product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., chromophore, fluorophore, coupled enzyme system). | High extinction coefficient/quantum yield, stability during assay, non-interference with enzyme activity. |

| Standard/Calibrator | For constructing standard curves (e.g., product standard for absorbance). | Traceable to primary standard, high purity. |

| Nonlinear Regression Software | Performs the direct fitting of data to the kinetic model. | Robust fitting algorithms (e.g., supports spline interpolation method [17]), accurate error estimation. |

| Accuracy Assessment Tool (ACI-Km Web App) | Quantifies the propagation of systematic concentration errors into K_m uncertainty [19]. |

Requires input of concentration accuracy intervals for enzyme and substrate. |

Quantitative Results and Accuracy Assessment

The ultimate validation of any method lies in its quantitative output and the reliability of its estimated uncertainties. The following table synthesizes key quantitative findings from the reviewed literature, highlighting the performance and implications of different approaches.

Table: Key Quantitative Findings on Parameter Estimation and Accuracy

| Source | Context/Method | Key Quantitative Result | Implication for Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Spline Interpolation vs. Analytical Methods | The spline-based numerical method showed lower dependence on initial parameter estimates while achieving accuracy comparable to analytical integrals. | Enhances robustness and accessibility of direct nonlinear fitting, reducing risk of convergence to local minima. |

| [21] | ANN Modeling of Michaelis-Menten ODEs | The BLM-ANN model achieved a Mean Squared Error (MSE) as low as 10^{-13} when approximating the system dynamics. |

Demonstrates the predictive power of data-driven methods but highlights that high fitting accuracy does not equate to interpretable parameter estimation. |

| [10] | High-Order MM for Single-Molecule Data | Key hidden parameters (k_on, ⟨T_ES⟩, P_cat) can be inferred robustly with several thousand turnover events per substrate concentration. |

Dramatically expands the information retrievable from single-molecule experiments via direct fitting of derived moment relationships. |

| [19] | Accuracy Confidence Interval (ACI-Km) | Standard K_m ± SE from regression can severely underestimate true uncertainty. ACI-Km provides a probabilistic interval that incorporates systematic concentration errors. |

Mandates a re-evaluation of reported K_m precision. For critical applications, ACI-Km should complement traditional SE to prevent decision-making based on inaccurately precise values. |

Direct nonlinear fitting stands as the method of choice for unbiased and efficient parameter estimation in enzyme kinetics. Its core advantages—eliminating transformation bias, utilizing all data points, and providing a direct route to accurate error estimates—are essential for modern research where K_m and V_max inform critical decisions in biotechnology and medicine [18] [17] [19].

The field continues to evolve on two fronts. First, towards more comprehensive uncertainty quantification, as exemplified by the ACI-Km framework, which forces a necessary confrontation with systematic errors that are often ignored [19]. Second, towards extracting richer information from complex experiments, such as using high-order Michaelis-Menten equations to mine single-molecule data for previously hidden kinetic details [10].

Future methodologies will likely involve tighter integration of robust direct fitting algorithms with advanced error propagation tools and machine learning-assisted model selection. However, the fundamental principle will endure: accurate understanding of enzyme function begins with an unbiased estimate of its kinetic constants, and there is no substitute for fitting the correct physical model directly to high-quality data.

The accurate determination of enzyme kinetic parameters is a cornerstone of biochemical research and drug development. The Michaelis-Menten equation, which relates reaction velocity (V) to substrate concentration ([S]) through the parameters Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant), provides the fundamental model for understanding enzyme activity [13]. Historically, researchers used linear transformations of this nonlinear equation, such as the Lineweaver-Burk plot, to estimate these parameters using simple linear regression [22]. However, these linearization methods distort error distribution and often yield biased estimates [13]. Modern enzyme kinetics research therefore relies on nonlinear regression to fit the original Michaelis-Menten model directly to experimental data. This approach, framed within a broader thesis on robust biochemical analysis, provides more accurate and precise estimates of Km and Vmax, along with essential statistical measures like confidence intervals that are critical for reliable scientific inference [23].

Foundational Concepts: Km and Vmax

The Michaelis-Menten Equation The relationship is defined by the equation: ( V = \frac{V{max} \times [S]}{Km + [S]} ) where V is the initial reaction velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, Vmax is the maximum reaction velocity, and Km is the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax [13].

Biological and Experimental Interpretation of Parameters

- Vmax represents the theoretical maximum rate of the reaction when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate. Its value is expressed in units of velocity (e.g., µM/min) and is directly proportional to the total enzyme concentration ([E]) and the catalytic constant (kcat) [22].

- Km, expressed in units of concentration (e.g., mM), is an inverse measure of the enzyme's apparent affinity for the substrate. A lower Km indicates higher affinity, meaning the enzyme achieves half its maximal rate at a lower substrate concentration [13]. It is crucial to note that Km is not a simple binding constant but a complex parameter influenced by both substrate binding affinity and the rate of catalytic conversion [22].

The Critical Role of Confidence Intervals

Definition and Statistical Basis A confidence interval (CI) provides a range of plausible values for a calculated parameter (e.g., Km or Vmax) at a specified probability level (typically 95%). A 95% CI indicates that if the same experiment were repeated many times, the calculated interval would contain the true parameter value 95% of the time. In nonlinear regression, CIs are asymmetrical and are calculated based on the shape of the error surface (sum-of-squares surface), reflecting the precision of the estimate [24] [22].

Interpreting CI Width and Shape

- Narrow vs. Wide Intervals: A narrow confidence interval indicates high precision and that the data well-define the parameter. A wide interval suggests uncertainty, often due to insufficient data, high experimental scatter, or an experimental design that does not adequately define the curve's asymptotes [24].

- Asymmetry: Unlike linear regression, CIs for nonlinear parameters are often asymmetric (e.g., 4.5 to 12.0), which more accurately represents the uncertainty in the estimate.

Impact of Experimental Design on Confidence Intervals The ability to calculate a complete confidence interval depends heavily on experimental data quality. Prism software documentation notes that if data cannot define the upper or lower plateau of a dose-response curve, the software may fail to calculate a full confidence interval for parameters like EC50 (analogous to Km), yielding only an upper or lower bound [24]. This underscores the need for experimental designs that clearly define the baseline and maximum response.

Diagram: Parameter Confidence in Nonlinear Regression

Methodological Comparison: Linearization vs. Nonlinear Regression

A seminal simulation study compared the accuracy and precision of five methods for estimating Vmax and Km [13]. The key findings are summarized in the table below.

Table: Performance Comparison of Km and Vmax Estimation Methods [13]

| Estimation Method | Description | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Relative Accuracy & Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | Linear plot of 1/V vs. 1/[S] | Simple, familiar visualization | Severely distorts error; poor accuracy/precision | Lowest |

| Eadie-Hofstee (EH) | Linear plot of V vs. V/[S] | Different error distortion than LB | Still distorts error; suboptimal | Low |

| Nonlinear (NL) | Fits V vs. [S] data directly to M-M equation | Direct fit; better error handling | Requires computational software | High |

| Nonlinear from Avg. Rate (ND) | Fits derived avg. rate data to M-M equation | Uses full time course data | Requires data manipulation | Moderate |

| Nonlinear Modeling (NM) | Fits [S]-time course data directly to differential equation | Most accurate/precise; uses all data | Requires advanced software (e.g., NONMEM) | Highest |

The study concluded that nonlinear methods (NM and NL) provided the most accurate and precise parameter estimates, with their superiority being most evident when data incorporated complex (combined) error models [13]. This confirms that direct nonlinear regression is the preferred method for reliable kinetics research.

Experimental Protocols for Robust Parameter Estimation

Protocol 1: Initial Velocity Assay for Michaelis-Menten Analysis This standard protocol generates the data (V vs. [S]) for nonlinear fitting [22] [23].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a constant concentration of purified enzyme in an appropriate buffer.

- Substrate Series: Prepare a dilution series of substrate, typically spanning a range from 0.2Km to 5Km (or broader) to adequately define the hyperbolic curve.

- Initial Rate Measurement: Initiate reactions by mixing enzyme with each substrate concentration. Measure the formation of product or depletion of substrate over time, ensuring measurements are taken in the linear initial rate period (typically <5% substrate conversion).

- Data Curation: Record the initial velocity (V) for each substrate concentration ([S]).

Protocol 2: Global Nonlinear Regression for Comparing Conditions This advanced protocol is used to reliably compare parameters (e.g., Km) between experimental conditions (e.g., control vs. inhibitor) [24].

- Data Organization: Collect V vs. [S] datasets for all conditions to be compared.

- Model Selection: Choose the Michaelis-Menten model.

- Parameter Sharing: Fit all datasets simultaneously (global fit). Share parameters assumed to be identical across conditions (e.g., Vmax), while allowing others (e.g., Km) to vary. This uses data more efficiently and yields tighter confidence intervals [24].

- Statistical Comparison: Use an extra sum-of-squares F-test to determine if separately fit parameters (e.g., Km for control vs. treated) are statistically different [24].

Diagram: Workflow for Enzyme Kinetics Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Software

| Item | Function in Enzyme Kinetics | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest; concentration must be known and constant across assays. | Recombinant protein, purified from tissue. |

| Varied Substrate | The molecule whose conversion is measured; prepared in a serial dilution. | Concentration should span the Km value. |

| Detection System | Measures product formation/substrate loss over time (initial linear phase). | Spectrophotometer, fluorimeter, or HPLC. |

| GraphPad Prism | Industry-standard software for direct nonlinear regression of V vs. [S] data [25] [22]. | Offers Michaelis-Menten fitting, CI calculation, and global fitting [24] [26]. |

| NONMEM | Advanced tool for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling, ideal for fitting full time-course data [13]. | Used in the superior NM method in the cited study [13]. |

| R / Python | Programming environments for custom analysis, simulations, and robust fitting algorithms. | Enables Monte Carlo simulations to assess method performance [13] [27]. |

Practical Guide to Interpreting Results

A Step-by-Step Framework

- Examine the Fit: Visually assess the overlay of the fitted curve on the V vs. [S] data. The curve should describe the trend without systematic bias.

- Check Residual Plot: Plot residuals (observed - predicted) vs. [S]. They should be randomly scattered, indicating a good fit. Patterns suggest model misspecification.

- Analyze Confidence Intervals: For each parameter (e.g., Km = 10.0, 95% CI: 7.5 to 13.2):

- The point estimate is 10.0.

- The true value has a 95% probability of lying between 7.5 and 13.2.

- Report the entire interval, not just the point estimate.

- Compare Parameters: When comparing conditions (e.g., Km with vs. without inhibitor), use a global fitting approach with an F-test rather than comparing overlapping CIs, as it is more statistically rigorous [24].

- Troubleshoot Wide CIs: If CIs are excessively wide, consider: collecting more data points, especially near the Km; reducing experimental variability; or ensuring the substrate concentration range adequately defines the curve's lower and upper plateaus [24].

Within the framework of modern nonlinear regression analysis, Km and Vmax transcend simple descriptive metrics. Their accurate estimation, coupled with a rigorous interpretation of their confidence intervals, forms the basis for robust conclusions in enzyme kinetics research. Moving beyond historical linearization methods to direct nonlinear fitting and employing global regression for comparisons are now established best practices [13] [24]. By prioritizing these methods and critically evaluating confidence intervals, researchers and drug developers can ensure the reliability and reproducibility of their kinetic data, thereby making informed decisions in both basic science and applied pharmacology.

From Theory to Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing Nonlinear Regression

Within the broader thesis of nonlinear regression in enzyme kinetics research, the choice of an appropriate mathematical model is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental decision that shapes experimental interpretation and predictive validity. The classic Michaelis-Menten equation, foundational for over a century, describes a hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity, defined by the parameters Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant) [28]. Its enduring power lies in its derivation from a simple reversible enzyme-substrate binding mechanism and its interpretable parameters.

However, contemporary research in drug development and systems biology routinely encounters scenarios that violate the classic model's core assumptions: single-substrate reactions, absence of inhibitors, and enzyme concentrations negligible compared to Km. Complexities such as allosteric regulation, multi-substrate reactions, enzyme inhibition, and in vivo conditions where enzyme concentration is significant necessitate modified or generalized equations [29] [10] [30]. This guide provides an in-depth framework for researchers to navigate this critical model selection process, ensuring kinetic parameters are accurately extracted to inform mechanistic understanding and therapeutic design.

Core Kinetic Models: Equations, Assumptions, and Applications

The decision to use a classic or modified model must be grounded in the underlying biochemistry of the system and the specific experimental data. The following sections delineate the foundational models and their modern extensions.

The Classic Michaelis-Menten Framework

The classic model is expressed as: v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S]) where v is the initial reaction velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, Vmax is the maximum velocity, and Km is the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity [28]. Its derivation assumes rapid equilibrium (or steady state) between enzyme and substrate, a single catalytic site, and that product formation is irreversible and rate-limiting. This model remains the gold standard for characterizing simple enzymatic systems in vitro and provides the benchmark against which all deviations are measured.

Modified and Generalized Equations for Complex Scenarios

When experimental data deviates from a simple hyperbolic fit or the system's known biology introduces complexity, modified equations are required. These modifications can involve adding terms, reparameterizing the equation, or deriving new relationships from more complex reaction schemes.

Table: Comparison of Classic and Modified Michaelis-Menten Equations

| Model Name | Equation Form | Key Parameters | Primary Application & When to Use | Key Assumptions/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Michaelis-Menten [28] | v = (Vmaxˣ[S])/(Km+[S]) | Vmax, Km | Single-substrate kinetics under standard in vitro conditions ([S] >> [E]). | Irreversible product release; single binding site; no cooperativity, inhibitors, or allosteric effectors. |

| Modified (for non-zero baseline) [31] | P = c₁ + (a₁ˣAge)/(b₁+Age) | a₁, b₁, c₁ | Modeling processes with a non-zero starting point (e.g., infant growth, where c₁ represents birth weight) [31]. | The underlying process follows saturation kinetics from a baseline other than zero. |

| General Modifier (Botts-Morales) [32] | Complex form accounting for activator/inhibitor | Vmax, Km, α, β, K_a | Systems with allosteric modifiers (activators or inhibitors) that bind at sites distinct from the active site. | Modifier binding alters catalytic efficiency (Vmax) and/or substrate affinity (Km). |

| High-Order MM (for single-molecule) [10] | Relations between moments of turnover time and 1/[S] | Moments of T_on, T_off, T_cat | Single-molecule enzymology to infer hidden kinetic parameters (e.g., binding rate, ES complex lifetime) [10]. | Analyzes stochastic turnover times; provides data beyond Vmax and Km. |

| PBPK Modified Equation [29] | Accounts for [E]T relative to Km | CL_int, [E]T, Km | Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling when enzyme concentration is not negligible ([E]T ≈ Km) [29]. | Addresses violation of standard assumption [E]T << Km; improves in vivo clearance prediction. |

| Competitive Inhibition (Full/Partial) [30] | v = (Vmaxˣ[S])/(Km(1+[I]/Ki) + [S]) (full) | Vmax, Km, Ki | Characterizing competitive inhibitors (substrate mimics). Distinguish full (inhibitor is also a substrate) from partial (dead-end complex) [30]. | Inhibitor binds reversibly to active site; rapid equilibrium or steady state assumed. |

A critical advancement is the development of high-order Michaelis-Menten equations for single-molecule analysis. These equations leverage the statistical moments of stochastic turnover times, establishing universal linear relationships with the reciprocal of substrate concentration. This allows researchers to infer previously inaccessible parameters such as the mean lifetime of the enzyme-substrate complex, the substrate binding rate constant, and the probability of catalytic success before substrate unbinding, providing a much richer mechanistic picture than Vmax and Km alone [10].

Model Selection for Key Complex Scenarios

Enzyme Inhibition and Activation

Inhibitor characterization is central to drug discovery. The choice of model depends on the inhibitor's mechanism:

- Competitive Inhibition: Use the standard competitive equation. Recent theoretical work shows that traditional quasi-steady-state approximations (sQSSA) can fail when enzyme concentration is comparable to substrate and inhibitor, a common in vivo scenario. Refined equations that account for the potential emergence of temporally separated dual steady states in the enzyme-substrate-inhibitor complex are necessary for accurate parameter estimation under these conditions [30].

- Non-competitive, Uncompetitive, and Mixed Inhibition: Standard models apply but can be unified under a general modifier equation framework. This approach simplifies the field by using a single equation to distinguish between inhibitor binding (defined by Ki) and its functional effect (defined by α and β factors altering Vmax and Km), outperforming fits from multiple classical equations [33].

- Allosteric Activation/Inhibition: The Botts-Morales general modifier model is appropriate, as it explicitly includes parameters for modifier binding and its effect on catalytic constants [32].

Beyond Simple Hyperbolas: Cooperativity and Multi-Substrate Reactions

- Cooperativity (Sigmoidal Kinetics): The Hill equation (v = (Vmax * [S]^n)/(K' + [S]^n)) replaces the classic MM model, where the Hill coefficient (n) quantifies the degree of cooperativity between multiple binding sites.

- Multi-Substrate Reactions: Models such as Ordered Bi-Bi, Random Bi-Bi, and Ping Pong mechanisms must be employed. These are available in specialized nonlinear regression software libraries [32]. Selection is based on initial velocity patterns from varied substrate concentrations.

From In Vitro to In Vivo: PBPK and Physiological Modeling

A significant frontier is translating in vitro enzyme kinetics to in vivo predictions. The classic MM equation assumes the total enzyme concentration ([E]T) is negligible compared to Km. This is often violated in physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models for drugs metabolized by enzymes like cytochrome P450s, leading to overestimation of metabolic clearance [29]. A modified metabolic rate equation that remains accurate when [E]T is comparable to Km has been shown to significantly improve prediction accuracy in bottom-up PBPK modeling without requiring empirical fitting to clinical data, thereby preserving the model's true predictive power [29].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Kinetic Model Selection and Validation (Width: 760px)

Methodological Foundation: Nonlinear Regression in Practice

Fitting kinetic models to data is inherently a nonlinear regression problem, as most enzyme kinetic equations are nonlinear in their parameters [28].

Experimental Protocol for Model Discrimination

A robust protocol for distinguishing between mechanisms (e.g., competitive vs. non-competitive inhibition) involves:

- Design: Measure initial velocities (v) across a wide range of substrate concentrations [S], at several fixed concentrations of the putative inhibitor [I] (including zero). Replicates are essential [28].

- Initial Analysis: Plot data as v vs. [S] for each [I]. Visual patterns (e.g., lines converging on y-axis suggest competitive inhibition) provide initial clues.

- Global Fitting: Simultaneously fit the entire 3D dataset ([S], [I], v) to candidate models (e.g., competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive) using nonlinear least-squares regression. This uses all data points to estimate a single set of shared parameters (Vmax, Km, Ki), greatly increasing robustness compared to fitting datasets at each [I] separately [33].

- Model Selection: Compare fitted models using metrics like the normalized Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), which balances goodness-of-fit with model complexity, penalizing overparameterization [32]. The model with the smallest AIC is preferred.

- Validation: Examine residual plots for systematic patterns, which indicate a poor model fit. Use confidence intervals for parameters; intervals spanning zero for a modifier effect suggest the parameter is not significant.

Protocol for Applying Modified Equations to Growth/Pharmacokinetic Data

For applying a modified MM equation to longitudinal data like pediatric growth [31]:

- Data Preparation: Collect longitudinal measurements (e.g., weight, height) with precise ages. Exclude physiologically implausible values and measurements from the immediate postnatal period of weight loss.

- Model Specification: Use a modified MM equation: P = c₁ + (a₁ * Age)/(b₁ + Age), where P is the parameter (weight/height), Age is in days, and c₁ represents the birth value.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit the model for each subject individually using nonlinear least squares (e.g.,

nls()in R). Critical starting values (e.g., a1=5, b1=20, c1=2.5 for weight) must be provided to avoid algorithm failures [31]. - Goodness-of-fit: Assess using Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). For infant weight, median RMSEs ~0.2 kg indicate excellent fit [31].

- Imputation & Prediction: The fitted model can interpolate missing values. Predictive power for future time points (e.g., Year 3 weight from Year 1 data) can be tested using a "last value" approach [31].

Diagram 2: From In Vitro Kinetics to Clinical Prediction (Width: 760px)

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Kinetic Analysis | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Regression Software | Fits data to complex kinetic models; performs parameter estimation, confidence intervals, and model comparison. | Use software with validated algorithms (e.g., NIST-certified) [32]. Options include BestCurvFit (extensive enzyme model library) [32], R (nls function), GraphPad Prism, and SAS PROC NLIN. |

| High-Quality Enzyme & Substrates | Provides reproducible primary activity data. The foundation of all modeling. | Use recombinant, purified enzymes with known specific activity. Substrates should be >95% pure. Buffer conditions (pH, ionic strength, temperature) must be rigorously controlled. |

| Mechanistic Inhibitors/Activators | Probes for characterizing enzyme mechanism and validating modified equations. | Use well-characterized compounds (e.g., classical competitive inhibitor for the target). Essential for generating the 3D datasets ([S], [I], v) needed for robust model discrimination [33] [30]. |

| Single-Molecule Assay Systems | Enables measurement of stochastic turnover times for high-order moment analysis. | Includes techniques like single-molecule fluorescence or force spectroscopy. Allows inference of hidden kinetic parameters (binding rates, ES complex lifetime) via high-order Michaelis-Menten equations [10]. |

| PBPK Modeling Platform | Integrates in vitro kinetic parameters into physiological models for in vivo prediction. | Software like GastroPlus, Simcyp, or PK-Sim. Must incorporate the modified rate equation when enzyme concentration is not negligible to avoid clearance overprediction [29]. |

| Global Fitting & Model Selection Scripts | Automates simultaneous fitting of complex datasets to multiple models and calculates selection criteria. | Custom scripts in R or Python are invaluable. Implement global fitting and AIC calculation to objectively select the best model from a set [33] [28]. |

Selecting the correct model—classic Michaelis-Menten or a modified equation—is a critical, hypothesis-driven process in modern enzyme kinetics. The classic model remains indispensable for simple systems, but the growing sophistication of drug discovery, single-molecule analysis, and in vivo prediction demands a flexible toolkit of modified equations. Researchers must first understand their system's biological complexity, then design experiments that generate data sufficient to discriminate between rival mechanistic models through rigorous global nonlinear regression and statistical model selection.

Future developments will likely focus on further bridging scales—from the stochastic events captured by high-order single-molecule equations [10] to the whole-body predictions of PBPK models using enzyme-concentration-aware equations [29]. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning with mechanistic modeling may help navigate increasingly complex kinetic landscapes, such as those involving multiple allosteric effectors or promiscuous enzymes. By grounding these advances in solid mechanistic principles and robust regression practices, researchers can ensure their kinetic models yield not just fitted parameters, but true biochemical insight.

Within the broader thesis of introduction to nonlinear regression in enzyme kinetics research, this guide addresses the foundational yet critical challenge of experimental design. The accurate estimation of kinetic parameters—the maximum velocity (Vmax), the Michaelis constant (Km), and the specificity constant (kcat/Km)—hinges not only on sophisticated fitting algorithms but, more fundamentally, on the quality and structure of the underlying data [34] [35]. A robust experimental design proactively minimizes error, quantifies uncertainty, and ensures that the collected data are maximally informative for the chosen kinetic model. This document provides an in-depth technical framework for designing experiments that yield robust, reliable fits, focusing on the strategic selection of substrate concentration ranges and the implementation of replication strategies. This approach is essential for generating reproducible results that can inform critical decisions in drug development, enzyme engineering, and fundamental biochemical research [36].

Core Principles of Robust Experimental Design

Robust experimental design in enzyme kinetics is governed by principles that ensure parameter estimates are precise, unbiased, and minimally sensitive to experimental noise and model misspecification.

Defining the Informative Substrate Concentration Range: The ideal range spans from a concentration well below

Kmto a concentration sufficiently above it to clearly define the asymptotic approach toVmax. As demonstrated by Hamilton et al., a range extending to 3.5-fold theKmcan yield linear calibration plots for a data-processing method based on nonlinear regression [34]. For traditional initial velocity analysis, a minimum range of 0.2Kmto 5Kmis often recommended. For systems with substrate inhibition, it is critical to include data points at concentrations both lower thanKmand higher than the inhibition constant (Ki) to separately identify these parameters [37]. Failure to include data at the extremes of the curve is a primary reason for ambiguous or failed fits [37] [35].The Critical Role of Replication: Replication is non-negotiable for robust fitting. It serves two key purposes: (1) quantifying experimental variability (pure error), and (2) enabling statistical tests of model adequacy. Technical replicates (repeated measurements of the same sample) assess assay precision, while biological replicates (measurements from independently prepared samples) capture broader experimental variance. Statistical tests, such as the replicates test, compare the scatter of replicates to the scatter of data around the fitted model; a significant result (e.g., P < 0.05) suggests the model is inadequate to describe the data, prompting consideration of alternative mechanisms like inhibition or cooperativity [38].

From Initial Rates to Global Progress Curve Analysis: The traditional method of estimating initial rates from a presumed linear portion of the progress curve is prone to error, as nonlinearity can be imperceptible yet biasing [35]. A more robust approach is global nonlinear fitting of complete progress curves. This method uses all the kinetic information in the reaction time course, not just an estimated initial slope, leading to more precise and accurate parameter estimates [39] [35]. Modern algebraic solutions, such as those utilizing the Lambert Omega function, allow for efficient global fitting by treating the specificity constant (

kcat/Km) as a primary fitted parameter [35].

The following workflow diagram outlines the decision-making process for establishing a robust foundational experimental design.

Diagram 1: Workflow for foundational robust experimental design.

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

Spectrophotometric Continuous Assay for Dehydrogenase/Kinase Activity

This protocol is adapted from integrated approaches for enzymes like Alcohol Dehydrogenase (ADH) and Pyruvate Decarboxylase (PDC), which are coupled to NADH oxidation [39].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare an extraction buffer (e.g., 100 mM MES pH 7.5, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 2.5% w/v polyvinylpyrrolidone, 0.02% w/v Triton X-100). Prepare reaction buffer containing all necessary substrates and cofactors at optimal pH (e.g., 1 M MES pH 6.5, acetaldehyde or pyruvate, NADH, MgCl₂, thiamine pyrophosphate for PDC) [39].

- Enzyme Extraction: Homogenize tissue (e.g., 0.5 g apple fruit) or cell pellet in cold extraction buffer. Centrifuge at 14,000×g for 20 minutes at 4°C. Combine supernatants. Determine protein concentration via Bradford assay [39].

- Assay Assembly: In a microplate well or cuvette, mix enzyme extract (e.g., 100 µL) with reaction buffer to a final volume of 250 µL. For coupled assays (e.g., PDC), include an excess of the coupling enzyme (e.g., commercial ADH) [39].

- Data Acquisition: Initiate reaction by adding the enzyme extract or a critical substrate. Immediately begin monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (NADH) or other appropriate wavelength continuously. Record data at high frequency (e.g., every 5-10 seconds) until the reaction reaches a steady baseline.

- Replication: Perform a minimum of three independent biological replicates, each with duplicate or triplicate technical measurements [38] [39].

Global Progress Curve Analysis for Kinetic Parameter Determination

This method uses the complete time-course data for fitting, as described by algebraic models employing the Lambert Omega function [35].

- Experimental Design: For a single substrate, prepare at least 5-8 different initial substrate concentrations (

[S]₀), spaced unevenly across the informative range (e.g., 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 × estimatedKm). Use the same enzyme concentration for all reactions. - Data Collection: For each

[S]₀, collect a dense progress curve (product concentration[P]vs. timet). The reaction should ideally proceed to near-completion (>80%) for at least the lowest[S]₀to define the curve fully [34] [35]. - Global Nonlinear Regression: Fit all progress curves simultaneously to the integrated rate equation. A robust model uses the Lambert W function:

[P] = [S]₀ + Km * W( [S]₀/Km * exp(([S]₀ - kcat*[E]₀*t)/Km) ), where[E]₀is the total enzyme concentration. ParametersKmandkcat(orkcat/Km) are shared across all datasets. Software like DynaFit or custom scripts in R/Python can perform this fit [35]. - Parameter Uncertainty: Estimate confidence intervals for

Kmandkcatfrom the covariance matrix of the nonlinear fit or via Monte Carlo bootstrap analysis.

Stochastic Simulation for Complex Enzyme Systems (Polymerase γ)

For highly processive, error-prone enzymes like mitochondrial DNA Polymerase γ, a stochastic simulation approach (Gillespie algorithm) bridges single-turnover kinetics and overall function [40] [41].

- Define Reaction List: Enumerate all possible reactions (e.g., correct/incorrect nucleotide incorporation, exonuclease proofreading, polymerase dissociation) [40].

- Input Kinetic Parameters: Populate the model with experimentally measured microscopic rate constants (

kpol,Kdfor dNTPs, exonuclease rates) for each reaction type [41]. - Set Initial Conditions: Define starting state: a polymerase bound to a DNA template, with specific intracellular concentrations of the four dNTPs.

- Run Stochastic Simulation: Execute the Gillespie algorithm: (a) calculate reaction propensities based on current state; (b) randomly choose the next reaction and its time interval; (c) update the molecular state and time; (d) iterate until DNA replication is complete [40] [41].

- Analyze Output: Repeat simulation thousands of times to generate statistical distributions of outcomes: total replication time, mutation frequency, processivity. This allows the analysis of how bulk kinetic parameters affect functional outcomes.

Data Analysis and Robust Fitting Strategies

Strategy Comparison for Parameter Estimation

The choice of data analysis strategy significantly impacts the robustness of the resulting parameters.

Table 1: Comparison of Enzyme Kinetic Data Analysis Strategies

| Strategy | Core Approach | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Rate (Lineweaver-Burk) | Linear fit of double-reciprocal transformed initial velocity data. | Simple graphical representation. | Highly sensitive to errors at low [S]; statistically unsound [35]. | Historical context; educational use. |

| Initial Rate (Nonlinear Fit) | Direct nonlinear fit of v₀ vs. [S] to Michaelis-Menten equation. |

Direct parameter estimation; standard method. | Depends on accurate, often subjective, v₀ estimation [39] [35]. |

High-quality, clear initial linear phases. |

| Global Progress Curve Analysis | Nonlinear fit of complete [P] vs. t curves for multiple [S]₀ to integrated rate law. |

Uses all data; avoids v₀ bias; often more precise [35]. |

Computationally more intensive; requires accurate [E]₀. |

Most robust general-purpose determination. |

| Stochastic Simulation | Monte Carlo simulation of individual reaction events using microscopic rates. | Links microscopic kinetics to macroscopic outcomes; models complex mechanisms [40] [41]. | Requires extensive microscopic rate data; computationally heavy. | Processive, multi-step enzymes (e.g., polymerases). |

Pathway for Robust Data Analysis and Model Discrimination

Following data collection, a systematic analysis pathway is required to validate the model and ensure robustness. The following diagram illustrates this critical post-experimental process.

Diagram 2: Pathway for robust data analysis and model discrimination.

Implementing Robust Optimal Design (ROD)

When discriminating between rival mechanistic models (e.g., standard Michaelis-Menten vs. substrate inhibition), Robust Optimal Design (ROD) algorithms can compute the most informative experimental conditions [42].

- Define Rival Models: Formulate the ODEs for competing kinetic models (e.g.,

v = Vmax*[S]/(Km + [S])vs.v = Vmax*[S]/(Km + [S] + [S]²/Ki)) [37] [42]. - Formulate Max-Min Problem: The ROD aims to find experimental conditions (e.g.,

[S]points) that maximize the difference between model predictions for the worst-case parameter sets within their uncertainty ranges. This is a semi-infinite optimization problem [42]. - Solve Iteratively: Use tools like the ModelDiscriminationToolkitGUI [42]:

- Phase 1: For a candidate design, find parameters that minimize difference (worst-case).

- Phase 2: Find a new design that maximizes difference for the fixed worst-case parameters.

- Iterate until convergence, ensuring the design is robust to parameter uncertainty.

- Apply Design: Run the experiment at the computed optimal substrate concentrations to collect maximally discriminating data.

Computational Tools and Predictive Frameworks

The field is increasingly augmented by computational tools that reduce experimental burden and guide design.

Table 2: Computational Tools for Robust Enzyme Kinetics

| Tool/Approach | Function | Application in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| GraphPad Prism | General nonlinear regression & diagnostics. | Performing replicates test; fitting substrate inhibition models; initial data exploration [38] [37]. |

| DynaFit | Global analysis of progress curves & complex inhibition. | Fitting integrated rate equations globally; discriminating between rival multi-step mechanisms [35]. |

| Gillespie Algorithm | Stochastic simulation of discrete chemical reactions. | Designing single-molecule kinetic experiments for polymerases; interpreting bulk parameters in functional context [40] [41]. |