Beyond Trial and Error: Leveraging the Fisher Information Matrix for Precision Enzyme Experimental Design

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) to optimize enzyme kinetic experiments.

Beyond Trial and Error: Leveraging the Fisher Information Matrix for Precision Enzyme Experimental Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) to optimize enzyme kinetic experiments. We bridge theoretical foundations with practical application, moving from core concepts of model-based experimental design (MBDoE) to advanced, field-specific methodologies[citation:1][citation:2]. The content explores how FIM-based criteria, such as D-optimality, minimize parameter uncertainty and transform experimental planning from an empirical art into a precision science[citation:2][citation:8]. We detail actionable strategies for designing fed-batch experiments, selecting sampling points, and navigating computational approximations of the FIM[citation:2][citation:8]. The guide also addresses critical troubleshooting for robust design against model misspecification and validates FIM approaches against emerging methods like information-matching for active learning[citation:6][citation:8]. Finally, we synthesize key takeaways and outline future directions, demonstrating how FIM-driven design accelerates reliable model calibration, enhances resource efficiency, and underpins innovation in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Informational Engine: Core Principles of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) in Enzyme Kinetics

Accurate enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km, Ki) are foundational for predictive metabolic modeling, drug discovery, and enzyme engineering. However, their experimental determination is plagued by high uncertainty, stemming from suboptimal experimental designs, data scarcity, and intrinsic biochemical complexities. This uncertainty propagates into computational models and engineering decisions, incurring significant costs in time and resources. This article frames the problem within Fisher information matrix (FIM) research, arguing that systematic, information-theoretic experimental design is critical for cost reduction. We present a synthesis of modern computational frameworks (ENKIE, CatPred, UniKP) that provide priors and uncertainty quantification, alongside advanced FIM-based protocols for optimal data collection. Application notes detail protocols for fed-batch kinetic assays and inhibition constant estimation, demonstrating how integrative computational and experimental strategies can drastically improve parameter identifiability and reduce the high cost of uncertainty.

The precise estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters—the maximum turnover rate (kcat), the Michaelis constant (Km), and inhibition constants (Ki)—is a cornerstone of quantitative biology. These parameters are critical for constructing dynamic models of metabolism [1], predicting drug-drug interactions [2], and engineering enzymes for industrial applications [3]. However, the classical approach to their determination is inherently inefficient and vulnerable to high variance. Traditional Michaelis-Menten analysis, often relying on graphical linearization methods, can distort error structures and yield unreliable estimates [4]. Experimental designs are frequently based on tradition rather than statistical optimality, leading to an overuse of resources for underwhelming gains in parameter precision [5].

The consequence is a high cost of uncertainty. In drug development, inaccurate Ki values for cytochrome P450 enzymes can lead to misprediction of pharmacokinetic interactions, posing clinical risks and potentially causing late-stage trial failures [2]. In metabolic engineering, poorly constrained parameters force models to be fitted to limited data, resulting in non-identifiable parameters and models that fail in predictive extrapolation [4]. The scarcity of reliable data is stark: while databases like BRENDA contain entries for thousands of enzymes, they cover only a minority of known enzyme-substrate pairs, and the reliability of many recorded values is unverified [1].

This article posits that the solution lies at the intersection of Bayesian statistics, machine learning, and optimal experimental design (OED). Framed within research on the Fisher Information Matrix, we explore how to maximize the information content of each experiment. The FIM, whose inverse provides the Cramér-Rao lower bound for the variance of any unbiased estimator, offers a mathematical framework to design experiments that minimize parameter uncertainty a priori [5]. When combined with modern computational tools that provide informed priors and uncertainty-aware predictions, FIM-based design transitions from a theoretical ideal to a practical, essential protocol for reducing the high costs associated with empirical enzyme characterization.

Computational Frameworks: Quantifying and Predicting Uncertainty

Before designing a single wet-lab experiment, researchers can leverage computational tools to predict parameter values and, crucially, to quantify the confidence in those predictions. This establishes priors for Bayesian estimation and highlights where experimental effort is most needed.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Computational Prediction Frameworks

| Framework | Core Methodology | Key Parameters | Uncertainty Quantification | Key Advantage | Reported Performance (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENKIE [1] | Bayesian Multilevel Models (BMMs) | kcat, Km | Calibrated predictive uncertainty from model and residuals. | Uses only categorical data (EC#, substrate); provides well-calibrated, interpretable uncertainty. | kcat: 0.36, Km: 0.46 |

| CatPred [3] | Deep Learning (pLMs, GNNs) | kcat, Km, Ki | Aleatoric & epistemic via ensemble/Bayesian methods. | Comprehensive framework; excels on out-of-distribution samples via pLM features. | Competitive with SOTA; lower variance correlates with higher accuracy. |

| UniKP [6] | Ensemble Models (e.g., Extra Trees) on pLM features | kcat, Km, kcat/Km | Not inherent; can be added via ensemble methods. | Unified high-accuracy prediction for three parameters; effective for enzyme discovery. | kcat: 0.68 (improvement over previous DLKcat) |

| 50-BOA [2] | Analytical error landscape analysis | Ki (Kic, Kiu) | Precision gained from optimal design, not prediction. | Reduces required experiments by >75% for inhibition constants. | Enables precise estimation from a single inhibitor concentration. |

ENKIE exemplifies a principled statistical approach. It employs Bayesian Multilevel Models on curated database entries, treating enzyme properties hierarchically (e.g., substrate, EC-reaction pair, protein family). This structure allows it to predict not only a parameter value but also a calibrated uncertainty that increases sensibly when predicting for enzymes distantly related to training data [1]. Its performance is comparable to more complex deep learning models, demonstrating that systematic statistical modeling of existing data is a powerful first step.

CatPred represents the state-of-the-art in deep learning for kinetics. It addresses critical challenges like performance on out-of-distribution enzyme sequences and explicit uncertainty quantification. By leveraging pretrained protein language models (pLMs), it learns generalizable patterns, ensuring more robust predictions for novel enzymes. The framework outputs query-specific uncertainty estimates, where lower predicted variances reliably correlate with higher accuracy [3].

UniKP focuses on achieving high predictive accuracy across multiple parameters using efficient ensemble models on top of pLM-derived features. Its demonstrated success in guiding the discovery of high-activity enzyme mutants underscores the practical utility of such tools for directing experimental campaigns [6].

These tools transform the experimental design problem. Instead of starting from complete ignorance, researchers can begin with an informative prior distribution (e.g., N(μ, σ) from ENKIE) for their parameters of interest. The goal of the experiment then becomes to reduce the variance (σ²) of this distribution as efficiently as possible.

The Fisher Information Matrix: A Framework for Optimal Design

The Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) formalizes the concept of information content in an experiment. For a kinetic model with parameters θ (e.g., Vmax, Km) and measurements y with covariance matrix Σ, the FIM I(θ) is defined by the expected curvature of the log-likelihood function. Its inverse provides a lower bound (Cramér-Rao bound) for the covariance matrix of any unbiased parameter estimator [5].

Optimal Experimental Design (OED) selects experimental conditions ξ (e.g., substrate concentration time points, sampling schedule) to optimize a scalar function of I(θ), such as:

- D-optimality: Maximizes det(I(θ)), minimizing the volume of the confidence ellipsoid for θ.

- A-optimality: Minimizes trace(I(θ)⁻¹), minimizing the average variance of parameter estimates.

- E-optimality: Maximizes the smallest eigenvalue of I(θ), strengthening the weakest direction of information.

Table 2: FIM-Based Insights for Michaelis-Menten Kinetic Design [5]

| Experimental Design Variable | Key FIM-Based Insight | Practical Implication for Uncertainty Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Feeding (Fed-Batch) | Superior to batch or enzyme feeding. Small, continuous substrate flow is favorable. | Fed-batch design can reduce the Cramér-Rao lower bound for Vmax and Km variance to 82% and 60% of batch values, respectively. |

| Substrate Concentration Range | Measurements should be clustered at the highest attainable concentration and near c2 = (Km*cmax)/(2Km + cmax). |

Avoid uniformly spaced concentrations. Prioritize achieving high substrate saturation and one point in the curved part of the Michaelis-Menten hyperbola. |

| Number of Measurements | Precision improves with more measurements, but with diminishing returns. | For a fixed total resource budget, optimal spacing of fewer points is often better than many suboptimal points. |

| Initial Parameter Guess | The FIM and optimal design depend on the nominal parameter values. | An iterative/sequential design is crucial: use a preliminary experiment to get rough estimates, then compute the optimal design for a refined experiment. |

A seminal application [5] demonstrates that moving from a batch to a substrate-fed-batch process significantly improves parameter precision. The FIM analysis proves that adding more enzyme is ineffective, while a controlled substrate feed maintains the reaction in the most informative dynamic region for longer. This is a direct example of reducing the cost of uncertainty: better data from one well-designed experiment can surpass the information from multiple poorly designed ones.

For inhibition studies, the 50-BOA method [2] is a specialized application of error landscape analysis congruent with FIM principles. It identifies that traditional multi-concentration designs waste resources on uninformative low-inhibitor conditions. It finds that using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC₅₀ and incorporating the harmonic mean relationship between IC₅₀ and Ki into the fitting process yields precise estimates with a fraction of the experimental effort.

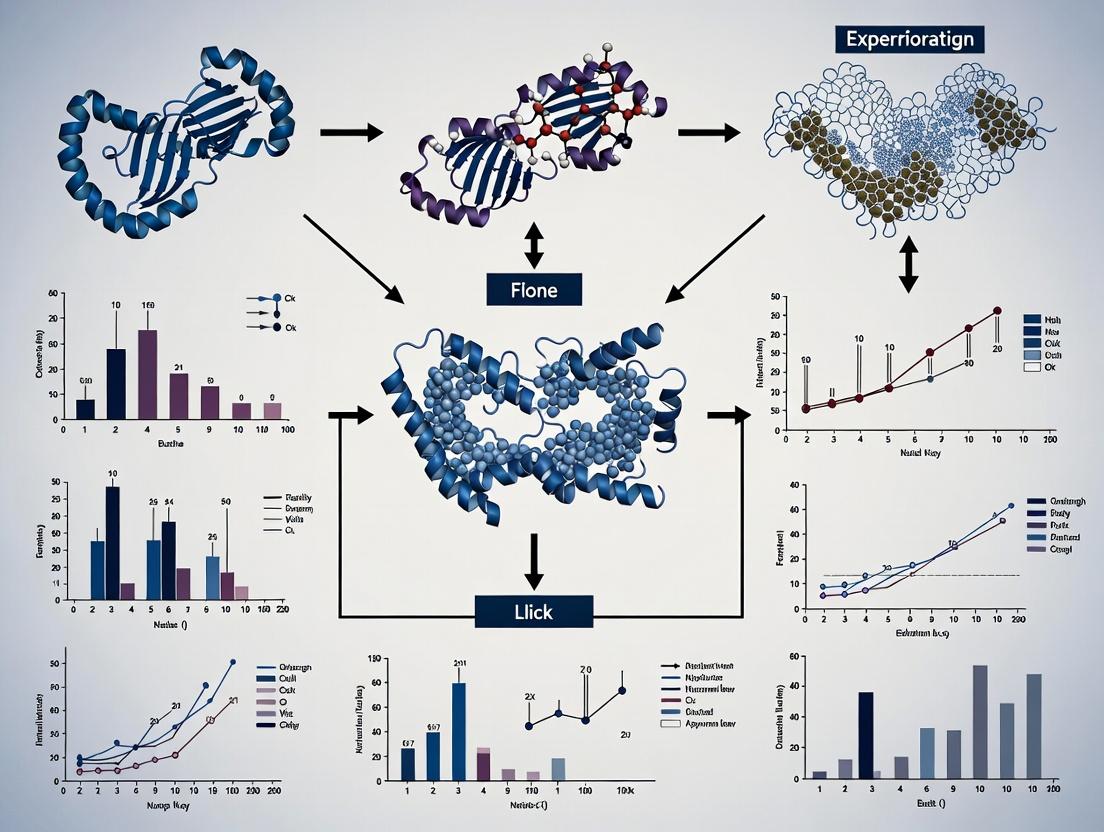

Diagram 1: FIM-Informed Iterative Experimental Design Workflow (94 chars)

Addressing Specialized Challenges: Identifiability and Complex Mechanisms

Standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics can present identifiability issues, where parameters are highly correlated (e.g., Vmax and Km). These issues are magnified in more complex systems.

A case study on CD39 (NTPDase1) [4] highlights a severe identifiability challenge: ADP is both the product of the ATPase reaction and the substrate for the ADPase reaction. Attempting to fit all four parameters (Vmax₁, Km₁, Vmax₂, Km₂) simultaneously from a single time-course ATP depletion curve leads to unidentifiable parameters—vastly different parameter sets can fit the data equally well. The solution is a protocol-based workflow that isolates the reactions.

Protocol 5.1: Ensuring Identifiability for Competing Substrate Reactions (e.g., CD39)

- Reaction Isolation: Perform two separate experimental setups.

- ATPase Reaction: Spike with a high concentration of ATP (e.g., 500 µM) and measure the initial rate of ATP depletion before ADP accumulates significantly. This initial rate primarily informs Vmax₁ and Km₁.

- ADPase Reaction: Spike with ADP as the sole initial substrate and measure the rate of ADP depletion. This informs Vmax₂ and Km₂.

- Independent Estimation: Fit a standard Michaelis-Menten model to the initial velocity data from each isolated reaction to obtain independent parameter sets.

- Global Validation: Use the independently estimated parameters as fixed inputs in the full competitive model (Eq. 3 in [4]) to simulate the time-course for the coupled reaction. Validate against the original coupled time-course data.

- Refinement (Optional): If discrepancy remains, use the independent estimates as strong priors in a final Bayesian fitting procedure for the full coupled model data.

This protocol enforces identifiability by designing experiments that decouple the information content for correlated parameters, a direct application of the principles underlying the FIM.

Application Notes & Detailed Experimental Protocols

- Objective: Precisely estimate Vmax and Km for a Michaelis-Menten enzyme.

- Principle: Maintain reaction velocity in its most sensitive region by controlled substrate feeding, maximizing information per sample.

- Materials: Enzyme solution, substrate stock, fed-batch reactor (or small-scale reaction vessel with syringe pump), spectrophotometer/LC-MS for product quantification, data acquisition system.

- Procedure:

- Preliminary Batch Run: Conduct a short batch experiment with a high initial substrate concentration to obtain rough estimates for Vmax' and Km.

- Design Calculation: Using the rough parameters, solve the D-optimal design problem for a fed-batch system. This typically yields an optimal substrate feed rate profile (often a small, constant flow) and optimal sampling times.

- Fed-Batch Execution: Initiate the reaction with a low initial substrate concentration (e.g., near Km). Start the substrate feed according to the optimal profile.

- Sampling: Collect samples at the pre-determined optimal time points. Immediately quench the reaction (e.g., acid, heat, inhibitor).

- Analysis: Measure product concentration for each sample.

- Non-Linear Regression: Fit the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation (or the differential equation system for fed-batch) to the time-course product concentration data using non-linear least squares (e.g., in MATLAB, R, or Python).

- Objective: Accurately and precisely estimate inhibition constants (Kic, Kiu) with minimal experimental effort.

- Principle: Use a single, well-chosen inhibitor concentration to capture the system's response, leveraging the IC₅₀ relationship.

- Materials: Enzyme, substrate, inhibitor, plate reader or LC-MS for activity measurement.

- Procedure:

- Determine IC₅₀: Perform a single-inhibitor-concentration experiment with substrate at [S] ≈ Km. Measure % activity remaining over a broad inhibitor concentration range (e.g., 0.1x to 10x expected IC₅₀). Fit a sigmoidal curve to estimate the IC₅₀ value.

- Optimal Single-Concentration Experiment: Choose one inhibitor concentration [I] > IC₅₀ (e.g., 2x IC₅₀). Measure initial reaction velocities (v) at multiple substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.2Km, 0.5Km, 1Km, 2Km, 5Km) both with and without the chosen inhibitor.

- Data Fitting with 50-BOA: Fit the mixed inhibition model (Eq. 1 in [2]) to the dataset. Critically, incorporate the estimated IC₅₀ value and its harmonic mean relationship with Kic and Kiu as a constraint during the fitting process (implemented in the provided 50-BOA software package). This step is key to recovering precision from limited data.

- Model Selection: The fitted values of Kic and Kiu will indicate the inhibition type (competitive if Kic << Kiu, uncompetitive if Kiu << Kic, mixed if they are comparable).

Diagram 2: Enzyme Inhibition Kinetics with Key Rate Constants (73 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Advanced Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | Gold-standard in vitro system for studying drug-metabolizing enzyme (e.g., CYP450) kinetics. Contains the full complement of cofactors and membrane environment [7]. | Pooled, gender-mixed, high-donor-count HLM for generalizable results. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Enables specific, sensitive, and multiplexed quantification of substrates and products, especially crucial for complex biological matrices like HLM incubations [7]. | High-sensitivity triple quadrupole or Q-TOF systems. |

| Controlled Fed-Batch Mini-Reactors | Enables precise implementation of FIM-optimized substrate feeding protocols for kinetic assays in small volumes, maximizing information yield [5]. | Microfluidic devices or well-plates integrated with syringe pumps for precise per-well feeding. |

| Pretrained Protein Language Model (pLM) Embeddings | Numerical representations (e.g., from ProtT5, ESM) of enzyme sequences that serve as high-quality feature inputs for computational predictors like CatPred and UniKP, enhancing accuracy for novel enzymes [3] [6]. | Embeddings from models like ProtT5-XL-UniRef50 (1024-dimensional per protein). |

| Software for Optimal Design & FIM Analysis | Tools to compute the Fisher Information Matrix and optimize experimental conditions (ξ) based on a defined kinetic model and prior parameters. | MATLAB (Statistics & Optimization Toolboxes), R (OptimalDesign package), Python (pyodes, sympy). |

| Bayesian Inference Software | Essential for parameter estimation that formally incorporates prior knowledge (from computational tools) and yields full posterior distributions, not just point estimates. | Stan (via cmdstanr/pystan), PyMC, MATLAB Bayesian Tools. |

| Metabolite & Reaction Identifier Standardization Tools | Critical for curating training data and ensuring correct mapping between biochemical names and structures for computational prediction. | MetaNetX API [1], PubChem, ChEBI, and KEGG mapping services. |

Within the broader thesis on Fisher Information Matrix (FIM)-driven enzyme experimental design research, this document establishes practical Application Notes and Protocols. The core premise is that the FIM provides a rigorous, quantitative framework to maximize the information content of experimental data for parameter estimation, directly addressing the challenges of costly and time-intensive enzyme kinetics studies [8] [9]. In drug development, precise estimation of kinetic and inhibition constants (e.g., Km, Vmax, Kic, Kiu) is non-negotiable for reliable in vitro to in vivo extrapolation and mechanism identification [10] [2]. Traditional one-factor-at-a-time or canonical multi-point designs are often statistically inefficient, wasting resources on non-informative data points [11] [2]. Model-based optimal experimental design (MBDoE or OED), which uses the FIM as an objective function to be maximized, systematically guides researchers toward experiments that yield the most precise parameter estimates, thereby accelerating the path from data to actionable kinetic knowledge [8] [12].

Core Quantitative Insights from Recent Literature

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent, high-impact research that demonstrates the power of FIM-based experimental design in enzymology.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of FIM-Based Experimental Designs in Enzymology

| Study Focus | Key Metric & Result | Methodology & FIM Criterion | Implication for Experimental Efficiency | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Inhibition Constant (Ki) Estimation | 75% reduction in experiments required for precise estimation of mixed inhibition constants. | 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach): Uses a single inhibitor concentration >IC50 with a defined substrate range, informed by error landscape analysis. | Replaces traditional multi-inhibitor concentration grids. Enables precise, mechanism-agnostic Ki estimation with minimal data. | [2] |

| Iterative Training of Complex Enzymatic Network Models | A 3-iteration OED cycle sufficed to build a predictive kinetic model for an 8-reaction network. | D-Optimality (D-Fisher Criterion): Maximized determinant of FIM to design substrate pulsation profiles in a microfluidic CSTR. | Efficiently maps complex kinetic landscapes. Active learning loop minimizes costly, non-informative experiments. | [9] |

| Population Pharmacokinetic (PK) Design in Drug Development | Up to 45% reduction in number of blood samples per subject in clinical studies. | Population FIM Evaluation/Optimization: Software (PFIM, PFIMOPT) used to optimize sampling schedules for population PK models. | Reduces clinical trial burden and cost while maintaining statistical power for parameter estimation. | [13] |

| Enzyme Assay Optimization | Optimization process reduced from >12 weeks (traditional) to <3 days. | Design of Experiments (DoE): Fractional factorial and response surface methodology to identify significant factors. | Dramatically speeds up assay development, a prerequisite for high-quality kinetic data generation. | [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Iterative Optimal Design for Enzymatic Reaction Network Characterization

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 Nature Communications study, details an active learning workflow for building predictive models of multi-enzyme systems [9].

Objective: To iteratively design maximally informative perturbation experiments to train a kinetic ODE model of an enzymatic network (e.g., a nucleotide salvage pathway).

Materials:

- Purified enzymes and substrates.

- Microfluidic continuous stirred-tank reactor (CSTR) system with multiple inlets.

- Immobilization matrix (e.g., hydrogel beads).

- Automated fraction collector.

- Analytics (e.g., ion-pair HPLC).

Procedure:

- Initialization: Immobilize enzymes individually. Perform basic activity assays to define feasible concentration ranges for substrates [9].

- Preliminary Calibration Experiment: Run a manually designed experiment (e.g., single steady-state condition). Use data to calibrate a prior kinetic model.

- Optimal Experimental Design Loop: For i = 1 to n iterations: a. OED Computation: Using the current model, compute parameter sensitivities. Apply a D-optimality criterion (maximize det(FIM)) via a swarm/evolutionary algorithm to design a time-varying input profile (pulsing sequence) for all substrates [9] [12]. b. Experiment Execution: Implement the computed profile in the flow reactor. Collect output fractions over time. c. Model Training: Add new data to the training set. Re-estimate all kinetic parameters of the ODE model. d. Validation & Stopping Criterion: Use the model from iteration i-1 to predict the outcomes of iteration i. Assess prediction error. Cycle terminates when prediction error falls below a threshold or ceases to improve [9].

Data Analysis: Fit the ODE model using maximum likelihood or least-squares estimation. The inverse of the FIM at convergence provides the lower-bound variance-covariance matrix for the parameter estimates, quantifying their precision.

Protocol 2: Single-Point IC50-Based Estimation of Inhibition Constants (50-BOA)

This protocol, based on a 2025 Nature Communications paper, enables efficient, precise estimation of inhibition constants (Kic, Kiu) without prior knowledge of the inhibition mechanism [2].

Objective: To accurately estimate competitive, uncompetitive, or mixed inhibition constants using a minimal experimental design.

Materials:

- Target enzyme.

- Substrate and inhibitor compounds.

- Assay components (buffer, cofactors, detection system).

- Plate reader or suitable spectrophotometer.

Procedure:

- Determine Michaelis-Menten Constant (Km): Under initial velocity conditions ([S] << [E]), vary substrate concentration to estimate Km and Vmax using standard methods [10].

- Determine Apparent IC50: Using a single substrate concentration near the Km value, perform a dose-response curve with inhibitor. Fit a standard inhibition curve to estimate the IC50 value [2].

- Optimal Single-Point Experiment: Set up reactions with substrate concentrations at 0.2Km, Km, and 5Km. For each substrate concentration, use a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50 (e.g., 2-3 x IC50). Include uninhibited controls (0 inhibitor) [2].

- Measurement: Measure initial velocities for all conditions (3 substrate x 2 inhibitor conditions = 6 data points plus controls).

- Analysis: Fit the mixed inhibition model (Equation 1) to the initial velocity data. Critically, incorporate the harmonic mean relationship between IC50, Km, and the inhibition constants (Kic, Kiu) as a constraint during fitting. This is the key step that ensures identifiability from sparse data [2].

Validation: The provided 50-BOA software package automates fitting and returns estimates with confidence intervals. Precision is proven to be superior to traditional multi-point designs using the same total number of data points [2].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Iterative FIM-Driven Experimentation Cycle (Active Learning) [9] [12]

Diagram 2: From Experimental Design to the Fisher Information Matrix [8] [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Solution Essentials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for FIM-Informed Enzyme Kinetics

| Category / Item | Specification & Purpose | Key Considerations for Optimal Design |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | High-purity, well-characterized recombinant or native enzyme. Source and lot consistency are critical [10]. | Specific activity must be known to set appropriate concentrations for initial velocity conditions [10]. Stability under assay conditions dictates feasible experimental timeframes. |

| Substrates & Inhibitors | Natural substrates or validated surrogates. Inhibitors of known purity. Solubility limits must be established [10] [2]. | Defining the experimentally feasible concentration range ([S]min to [S]max) is a fundamental constraint for the OED algorithm [9] [15]. |

| Cofactors & Essential Ions | Mg²⁺, ATP, NAD(P)H, etc., as required by the enzyme system. | Concentrations may be treated as fixed or as additional design variables to optimize, depending on the experimental goal. |

| Buffer System | Chemically defined buffer (e.g., HEPES, Tris, phosphate) at optimal pH. | pH and ionic strength can be included as factors in a DoE screening phase prior to detailed kinetic OED [11]. |

| Detection System | Spectrophotometer, fluorimeter, or HPLC/MS for product formation/substrate depletion. | Linear range of detection is paramount [10]. The signal-to-noise ratio (affecting σ² in FIM calculation) must be characterized. |

| Automation & Fluidics | Liquid handler, microfluidic flow reactor (e.g., CSTR) [9]. | Enables precise execution of complex, time-varying optimal input profiles generated by OED algorithms that are impractical manually. |

| Software | OED/MBDoE platforms (e.g., PopED, PFIM, R/Python packages), kinetic modeling tools. |

Required to compute sensitivities, construct the FIM, and solve the optimization problem to find the next best experiment [12] [13] [14]. |

Theoretical Foundation: FIM and CRLB in Parameter Estimation

The precision of any parameter estimation experiment is fundamentally bounded by the Cramér-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB), with the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) serving as the quantitative bridge to this limit [16]. For a deterministic parameter vector (\boldsymbol{\theta}) estimated from measurements, the covariance matrix of any unbiased estimator (\boldsymbol{\hat{\theta}}) is bounded by the inverse of the FIM [17] [16]: [ \operatorname{cov}(\boldsymbol{\hat{\theta}}) \geq I(\boldsymbol{\theta})^{-1} ] Here, (I(\boldsymbol{\theta})) is the FIM, whose elements for a probability density function (f(x; \boldsymbol{\theta})) are defined by [17]: [ I{m,k} = \operatorname{E} \left[ \frac{\partial}{\partial \thetam} \log f(x; \boldsymbol{\theta}) \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_k} \log f(x; \boldsymbol{\theta}) \right] ] Intuitively, the FIM measures the sensitivity of the observed data to changes in the parameters. Greater sensitivity yields a larger FIM, which in turn leads to a smaller CRLB, indicating the potential for higher estimation precision [17].

In the context of enzyme kinetic experiments, the parameters of interest (e.g., (Km), (V{max})) are embedded within a dynamic model describing substrate consumption and product formation [5]. The design of the experiment—such as when to sample, whether to add substrate, and how much measurement noise is present—directly influences the FIM and, consequently, the best achievable precision of the parameter estimates [5].

The following diagram illustrates the logical and mathematical relationship between experimental design, the FIM, and the resulting bounds on estimation precision.

Practical Implementation in Enzyme Kinetics: From Theory to Protocol

Applying the FIM-CRLB framework requires translating the theoretical model into a computable criterion for designing experiments. For a dynamic enzyme kinetic process described by ordinary differential equations (ODEs), the FIM is computed based on the sensitivity of the model outputs to its parameters [5].

Core Calculation for Dynamic Systems: For a model defined by ODEs (\frac{dx}{dt} = f(x,t,\boldsymbol{\theta})) with measurement function (y = g(x,t,\boldsymbol{\theta})), the FIM for (N) measurement time points under additive Gaussian noise (variance (\sigma^2)) is [5]: [ I(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \sum{i=1}^{N} \left( \frac{\partial y(ti)}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}} \right)^T \left( \frac{\partial y(ti)}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}} \right) ] The term (\frac{\partial y(ti)}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}}) is the parameter sensitivity at time (t_i), typically calculated by solving the model's sensitivity equations alongside the original ODEs [5].

Key Experimental Insight from FIM Analysis: A pivotal study applying this to Michaelis-Menten kinetics yielded a critical finding for experimental design: substrate feeding in a fed-batch mode can significantly improve parameter estimation precision compared to a simple batch experiment, while enzyme feeding does not [5] [18]. The quantitative gains are summarized below.

Table 1: Impact of Substrate Fed-Batch Design on Estimation Precision (CRLB) for Michaelis-Menten Parameters [5] [18]

| Parameter | Batch Experiment (Baseline Variance) | Optimal Substrate Fed-Batch Experiment | Improvement (Reduction in CRLB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Reaction Rate ((\mu{max}) or (V{max})) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.82 | 18% reduction |

| Michaelis Constant ((K_m)) | 1.0 (Reference) | 0.60 | 40% reduction |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents and Materials for FIM-Optimized Experiments

Conducting experiments designed via FIM analysis requires standard enzymatic assay components, with particular attention to reagents that enable controlled substrate feeding and precise measurement.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FIM-Optimized Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Design | Key Consideration for FIM |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Target | The biocatalyst whose parameters ((Km), (V{max})) are being estimated. | High purity is critical to ensure the model accurately describes the observed kinetics [19]. |

| Substrate Solution | The reactant consumed by the enzyme. Prepared at high concentration for feeds. | Fed-batch optimization requires a concentrated stock for controlled addition [5]. |

| Buffered Reaction System | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength to isolate kinetic effects. | Stability is essential for long-duration fed-batch experiments [5]. |

| Stopping Reagent or Real-time Probe | Quenches the reaction or allows continuous monitoring (e.g., fluorescent, colorimetric) [20]. | Defines the measurement error variance ((\sigma^2)), a key term in the FIM calculation [5] [21]. |

| Programmable Syringe Pump | Precisely delivers substrate feed according to the optimal calculated profile. | Enables implementation of the optimal fed-batch trajectory [5]. |

| Plate Reader or Spectrophotometer | Measures product formation or substrate depletion at designed time points. | High precision reduces (\sigma^2), directly improving the CRLB [19]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial Batch Experiment for Preliminary Parameter Estimation Objective: Obtain rough parameter estimates required to initialize FIM-based optimization for a subsequent fed-batch experiment [5].

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a batch reaction mixture with a high initial substrate concentration (e.g., (S0 \gg K{m(guess)})). Run parallel reactions with different initial substrate levels if possible.

- Sampling: Take aliquots at evenly spaced time intervals covering the progression from initial velocity to near substrate depletion.

- Analysis: Fit the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation or the differential model directly to the time-course data using nonlinear least squares to obtain (\hat{K}{m}) and (\hat{V}{max}) [5].

- Output: These estimates form the nominal parameter vector (\boldsymbol{\theta}_0) used to calculate the FIM for the next design stage.

Protocol 2: FIM-Based Optimization of a Fed-Batch Experiment Objective: Compute and execute a substrate feeding profile that minimizes the CRLB for (Km) and (V{max}).

Procedure:

- Define Design Variables: Parameterize the substrate feed rate (Fs(t)) over the experiment duration ([0, tf]). Discretize into a finite number of control intervals.

- Compute Sensitivities: Using the nominal parameters (\boldsymbol{\theta}_0) from Protocol 1, solve the system ODEs and sensitivity equations (\partial x/\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}) numerically [5].

- Optimize: Maximize a scalar function of the FIM (e.g., D-optimality: (\max \det(I(\boldsymbol{\theta}, Fs(t))))) by adjusting (Fs(t)). This is a nonlinear optimization problem. Constraints include total substrate volume and reactor capacity [5].

- Experimental Execution: Run the enzyme reaction in a stirred vessel. Start the reaction in batch mode. Initiate the optimized feed profile (F_s^*(t)) using a programmable pump. Sample the reaction at pre-determined, optimally chosen time points [5].

The following workflow diagram maps the sequential and iterative process from initial data collection to an optimized experiment.

Advanced Protocols and Computational Methods

Protocol 3: Accounting for Non-Gaussian Measurement Noise Background: The standard FIM formula assumes additive Gaussian noise. For instruments like plate readers or MRI scanners, noise may follow a Rician or noncentral χ-distribution, especially at low signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) [21]. Procedure: Use the more general log-likelihood (\log(L)) for the correct noise distribution to calculate the FIM elements [21]. For a noncentral χ-distribution with (m) coils, the first derivative of the log-likelihood is [21]: [ \frac{\partial}{\partial \betaj} \log(L\chi) = \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \sum{n=1}^N \frac{\partial An}{\partial \betaj} \left( Mn \frac{Im(zn)}{I{m-1}(zn)} - An \right) ] where (An) is the noise-free signal model, (Mn) is the measured magnitude, and (zn = Mn An / \sigma^2). This formulation must be used in the FIM calculation (Eq. 2) for accurate CRLB prediction in low-SNR regimes [21].

Protocol 4: Estimating the FIM via Parametric Bootstrap Background: For complex nonlinear mixed-effects models, the analytical FIM may be difficult to derive or compute. Procedure: Use parametric bootstrap to numerically approximate the FIM [22].

- Using the nominal model and parameters (\boldsymbol{\theta}_0), generate a large number (B) (e.g., 100) of simulated datasets.

- Fit the model to each simulated dataset to obtain (B) parameter estimates (\boldsymbol{\hat{\theta}}_b).

- Compute the empirical covariance matrix (\operatorname{cov}(\boldsymbol{\hat{\theta}})) of these bootstrap estimates.

- The inverse of this covariance matrix provides a numerical estimate of the FIM: (\hat{I}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \approx \operatorname{cov}(\boldsymbol{\hat{\theta}})^{-1}) [22]. This method is computationally intensive but highly general.

Data Presentation: Comparing Experimental Designs

The ultimate validation of an FIM-optimized design is the measurable improvement in parameter estimation. The following table synthesizes key findings from the literature on optimal design strategies for Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

Table 3: Comparison of Experimental Designs for Michaelis-Menten Parameter Estimation [5]

| Design Criterion | Optimal Measurement Strategy (Constant Error Variance) | Key Advantage | Practical Compromise |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-optimality (max det(FIM)) | Half at highest ([S]{max}), half at (c2 = \frac{Km[S]{max}}{2Km + [S]{max}}) | Maximizes overall joint precision of (Km) and (V{max}). | Requires good prior for (K_m). |

| Minimize var((K_m)) | Measurements spread across range, emphasis on lower [S]. | Best precision for the Michaelis constant. | Less precise (V_{max}) estimate. |

| Simple Batch (even sampling) | Measurements at evenly spaced time intervals. | Simple to execute, robust. | Lower precision than optimal designs. |

| Optimal Fed-Batch | Controlled substrate feed with small volume flow [5]. | CRLB reduced to 60-82% of batch values [5] [18]. | Requires programmable pump and prior estimates. |

Future Directions and Integration with Modern Enzyme Engineering

The integration of FIM-based experimental design with cutting-edge enzyme engineering and high-throughput screening (HTS) represents a powerful frontier [23] [20]. Computational and AI tools are increasingly used for enzyme engineering [23], and these models can directly inform the design of kinetic characterization experiments via the FIM framework. Furthermore, as assays move toward more sensitive, label-free biosensor technologies (e.g., SPR, BLI) [20], the accurate characterization of their noise distributions (Rician, noncentral χ) becomes essential for correct FIM and CRLB calculation, ensuring that optimal designs truly deliver the best possible parameter precision [21].

Foundations of Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) for Biochemical Systems

The Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) is a systematic framework that uses mathematical models to plan experiments that maximize information gain, particularly for model calibration and parameter estimation [8]. Within biochemical systems research, such as enzyme kinetics and metabolic pathway analysis, MBDoE is critical because experimental resources are often limited, and the systems are inherently complex and nonlinear [8] [5]. This article frames MBDoE within the specific context of Fisher information matrix (FIM) research for enzyme experimental design. The FIM quantifies the amount of information that observable data provides about unknown model parameters, serving as the cornerstone for designing experiments that yield precise and reliable parameter estimates, thereby accelerating drug discovery and bioprocess optimization [5].

Theoretical Foundations: The Fisher Information Matrix

The core of MBDoE for parameter precision is the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM). For a dynamic model described by differential equations, the FIM is calculated from the sensitivity of model outputs to its parameters. It is defined as the expectation of the Hessian of the log-likelihood function [5]. The inverse of the FIM provides the Cramér-Rao lower bound (CRLB), which represents the minimum possible variance for an unbiased parameter estimator [5]. Therefore, by maximizing a scalar function of the FIM, an experiment can be designed to minimize the expected variance of parameter estimates.

Different optimality criteria are used to scalarize the FIM, each with a specific statistical goal [8] [24] [5].

Table 1: Key Optimality Criteria for Experimental Design

| Criterion | Objective | Application in Biochemical Systems |

|---|---|---|

| D-Optimality | Maximize the determinant of the FIM. | Minimizes the joint confidence region volume for all parameters. Commonly used for general parameter estimation in enzyme kinetics [24] [5]. |

| A-Optimality | Minimize the trace of the inverse of the FIM. | Minimizes the average variance of the parameter estimates [24]. |

| E-Optimality | Maximize the smallest eigenvalue of the FIM. | Focuses on improving the precision of the least identifiable parameter [8]. |

| c-Optimality | Minimize the variance of a linear combination of parameters. | Useful for precise prediction of a specific system output, such as a reaction rate at a physiologically relevant substrate concentration [24]. |

Protocols for MBDoE Implementation in Enzyme Kinetics

This protocol outlines the steps for applying MBDoE to estimate parameters (e.g., V_max and K_m) of the Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetic model.

3.1. Preliminary Step: Initial Model and Priors

- Define Model Structure: Start with the ordinary differential equation (ODE): dS/dt = - (V_max * S) / (K_m + S), where S is substrate concentration.

- Obtain Preliminary Parameter Estimates (θ₀): Conduct a small, space-filling initial experiment (e.g., measuring initial velocity at 4-6 broadly spaced substrate concentrations). Use nonlinear regression to obtain initial guesses for V_max and K_m [5].

3.2. Core MBDoE Iterative Cycle

- Compute the FIM: For a candidate experimental design (e.g., a set of proposed substrate concentration sampling points and times), calculate the FIM based on the current parameter estimates θ₀ and the model sensitivity equations [5].

- Optimize the Experimental Design: Using a D-optimal criterion, formulate and solve an optimization problem to find the design (substrate concentrations, sampling times, initial conditions) that maximizes det(FIM). For Michaelis-Menten kinetics, analytical results show that substrate feeding in a fed-batch setup can improve precision over batch experiments, and optimal sampling often focuses on points near the K_m and at the highest feasible concentration [5].

- Execute the Designed Experiment: Perform the laboratory experiment according to the optimized design, ensuring careful control of conditions (pH, temperature, cofactors) as defined in assay development best practices [25] [26].

- Estimate Parameters & Validate: Fit the new experimental data to the model to obtain updated parameter estimates (θ₁). Perform statistical validation (e.g., residual analysis, confidence intervals).

- Assess Convergence & Iterate: If parameter uncertainties are above the required threshold, update the prior estimates to θ₁ and repeat the cycle from Step 1.

3.3. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzymatic MBDoE

| Reagent/Material | Function in MBDoE Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biological catalyst under study. Source (recombinant vs. native) and specific activity must be standardized [27]. | Purity and stability are critical for reproducible kinetics. Aliquots should be stored to minimize activity loss between experiment cycles [26]. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) converted by the enzyme. | Selection of physiologically relevant substrate is crucial. A range of concentrations must be preparable to cover values below, near, and above the expected K_m [5]. |

| Cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺, ATP, NADH) | Required for the activity of many enzymes. | Concentration must be optimized and held constant in all assay wells to avoid being a confounding variable [25] [26]. |

| Detection System | Quantifies product formation or substrate depletion. Common methods include fluorescence (FP, TR-FRET) or luminescence [25]. | Homogeneous, "mix-and-read" assays (e.g., Transcreener) are preferred for HTS and simplify automated workflows for data-rich MBDoE [25]. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains optimal pH, ionic strength, and enzyme stability. | Composition (e.g., HEPES, Tris) and pH can dramatically affect kinetic parameters. Must be optimized and rigorously controlled [25] [26]. |

Advanced Applications and Future Challenges

4.1. Robust Design for Handling Uncertainty A primary challenge in MBDoE is that the optimal design depends on the prior parameter estimates (θ₀), which are uncertain. A robust experimental design methodology addresses this by generating designs that maintain high efficiency over a range of possible parameter values [24]. One approach is to add support points to a standard D-optimal design, creating an augmented design that is less sensitive to misspecifications in θ₀ [24]. This is particularly valuable for complex biochemical models like the Baranyi model for microbial growth, where initial guesses may be poor.

Diagram: Workflow for Robust MBDoE Against Parameter Uncertainty

4.2. MBDoE for Complex Biochemical Systems Future directions involve applying MBDoE to larger, more complex systems, such as full metabolic networks or pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) models. Key challenges include:

- Computational Burden: Calculating FIM for high-dimensional systems is expensive. Machine-learning-assisted methods, like using Gaussian process regression to approximate model sensitivities, are emerging solutions [28].

- Model Discrepancy and Sloppiness: Models are always simplifications. MBDoE under structural model uncertainty is an open research area to prevent designs from reinforcing model errors [8] [28].

- Online/Adaptive MBDoE: Integrating real-time data analysis to dynamically redesign experiments during their execution, closing the loop between data collection, model updating, and design optimization for maximum efficiency [28].

Diagram: MBDoE for Large Metabolic Networks with ML Support

Within the broader thesis on Fisher information matrix (FIM) research for enzyme experimental design, this primer establishes the critical link between abstract optimality criteria and practical laboratory efficacy. The primary goal of optimal experimental design (OED) is to plan experiments that yield the most informative data for parameter estimation or model discrimination, thereby maximizing knowledge gain while conserving valuable resources like time, enzymes, and substrates [29]. At the core of this approach lies the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM), a mathematical quantity that summarizes the amount of information an observable random variable carries about unknown parameters. According to the Cramér-Rao inequality, the inverse of the FIM provides a lower bound for the variance-covariance matrix of any unbiased estimator [30]. Therefore, by designing an experiment to maximize an appropriate function of the FIM, we directly minimize the expected uncertainty in our parameter estimates.

This process is particularly vital in enzyme kinetics, where models like Michaelis-Menten and its extensions for competitive and non-competitive inhibition are fundamental [31]. The choice of experimental conditions—such as substrate and inhibitor concentration levels and sampling times—profoundly impacts the precision of estimated parameters like ( V{max} ) and ( Km ). A model-based OED approach moves beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time designs to provide a systematic, statistically principled framework for efficient experimentation in drug development and basic enzymology [29] [5].

Core Optimality Criteria: Definitions and Comparisons

Different optimality criteria scalarize the FIM to optimize different properties of the parameter estimates or model predictions. The choice of criterion depends on the primary objective of the experimental study.

- D-Optimality: This is the most commonly used criterion. A D-optimal design maximizes the determinant of the FIM, which is equivalent to minimizing the volume of the confidence ellipsoid of the parameter estimates [32]. It is the appropriate choice when the goal is precise, simultaneous estimation of all model parameters. For nonlinear models, the FIM—and thus the optimal design—depends on the prior nominal values of the parameters themselves [5]. Research indicates that for a simple Michaelis-Menten model, a D-optimal design typically places measurements at just two substrate concentrations [5].

- A-Optimality: An A-optimal design minimizes the trace of the inverse of the FIM, which is equivalent to minimizing the average variance of the parameter estimates [32]. This criterion focuses on the precision of individual parameter estimates rather than their joint confidence region. It allows researchers to place differential emphasis on specific parameters of greatest interest, which is useful when certain kinetic constants are more critical to the study's objective than others.

- E-Optimality: An E-optimal design maximizes the minimum eigenvalue of the FIM. This translates to minimizing the length of the largest axis of the confidence ellipsoid for the parameters, thereby improving the worst-case scenario of estimation precision [30]. It is particularly valuable for ensuring that no single parameter or linear combination of parameters is estimated with disproportionately poor precision.

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guidance The table below summarizes the mathematical objective and primary application of each criterion.

| Criterion | Mathematical Objective | Primary Application in Enzyme Studies | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-Optimality | Maximize ( \det(FIM) ) | Precise joint estimation of all kinetic parameters (e.g., ( V{max} ), ( Km ), ( K_i )) [31] [32]. | The "gold standard" for general parameter estimation; design depends on prior parameter guesses. |

| A-Optimality | Minimize ( \operatorname{tr}(FIM^{-1}) ) | Minimizing the average or weighted variance of parameter estimates; useful when specific parameters are of key interest [32]. | Can be more sensitive to parameter scaling than D-optimality. |

| E-Optimality | Maximize ( \lambda_{min}(FIM) ) | Improving the precision of the least-estimable parameter or linear combination; ensures balanced information [30]. | Less commonly used than D or A; focuses on the worst-case precision. |

Diagram: Decision Pathway for Selecting an Optimality Criterion The following diagram illustrates the logical process for selecting an appropriate optimality criterion based on the research goal.

Application Notes for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

Applying OED principles requires careful consideration of the enzymatic system's unique characteristics. A critical and often overlooked aspect is the statistical error structure. While enzyme kinetic data are inherently non-negative, a standard nonlinear regression model with additive, normally distributed errors can theoretically produce negative simulated reaction rates, violating biological reality [31]. A robust alternative is to assume multiplicative, log-normal errors. This involves log-transforming both the Michaelis-Menten model (e.g., ( v = \frac{V{max}[S]}{Km + [S]} )) and the data: ( \ln(v) = \ln\left(\frac{V{max}[S]}{Km + [S]}\right) + \epsilon ), where ( \epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma^2) ). This transformation ensures positive rate predictions, aligns better with the error behavior in many assay systems, and can decisively affect the resulting optimal experimental designs, especially for model discrimination [31].

Practical Substrate Concentration Ranges For the foundational Michaelis-Menten model, analytical solutions for D-optimal designs exist under specific error assumptions [5]. The recommended substrate concentrations shift significantly based on the presumed error structure.

| Error Assumption | Optimal Substrate Concentration 1 | Optimal Substrate Concentration 2 | Implied Design Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Absolute Error(Additive Gaussian) | Highest feasible concentration (([S]_{max})) | ( [S]{opt} = \frac{Km \cdot [S]{max}}{2Km + [S]_{max}} ) | Half measurements at very high [S], half at a moderate level [5]. |

| Constant Relative Error(Multiplicative Log-normal) | Highest feasible concentration (([S]_{max})) | Lowest feasible concentration (([S]_{min})) | Spread measurements across the entire accessible range [5]. |

Extension to Inhibition Studies For more complex models like competitive inhibition (( v = \frac{V{max}[S]}{Km(1+[I]/K_i) + [S]} )), the design space expands to two dimensions: substrate concentration ([S]) and inhibitor concentration ([I]). A D-optimal design for parameter estimation in such a model typically consists of a few support points at the corners and edges of the (([S]), ([I])) design region [31]. When the goal shifts to discriminating between rival models (e.g., competitive vs. non-competitive inhibition), criteria like T-optimality or Ds-optimality are used. These criteria design experiments to maximize the expected difference in model predictions, making the correct model easier to identify [31].

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols detail the steps for implementing a model-based optimal design, from initial setup to final experimental execution, with a focus on enzyme inhibition studies.

Protocol 1: Initialization and Preliminary Parameter Estimation This protocol is essential for generating the nominal parameter values required to compute the FIM for a nonlinear model.

- Literature & Preliminary Experiment:

- Conduct a literature review to obtain approximate values for kinetic parameters ((V{max}), (Km), (K_i)).

- If reliable estimates are unavailable, perform a small-scale preliminary experiment.

- For an inhibition study, use a matrix of 4-6 substrate concentrations (spanning from ~0.2(Km) to 5(Km)) and 2-3 inhibitor concentrations (including zero) [31].

- Data Fitting and Error Analysis:

- Fit the preliminary data to the intended kinetic model (e.g., competitive inhibition) using nonlinear regression.

- Critical Step: Analyze the residuals. Plot them against the predicted reaction rate. If the variance increases with the rate, adopt a multiplicative error model and perform fitting on log-transformed data [31].

- Record the obtained parameter estimates as the nominal vector ( \theta0 = (V{max}, Km, Ki) ). Estimate the residual variance ( \sigma^2 ).

Protocol 2: Computing a D-Optimal Design for Parameter Estimation This protocol uses software tools to find the optimal combination of design variables.

- Define Design Variables and Region:

- Let the design variable be ( x = ([S], [I]) ).

- Define the experimentally feasible region: ( [S]{min} \leq [S] \leq [S]{max} ), ( [I]{min} \leq [I] \leq [I]{max} ).

- Specify the total number of experimental runs ( N ) (e.g., 24).

- Calculate and Optimize the FIM:

- For a given candidate design (a set of (N) points ( \xi = {x1, x2, ..., xN} )), compute the Fisher Information Matrix. For a nonlinear model with nominal parameters ( \theta0 ): ( FIM(\theta0, \xi) = \sum{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{\sigma^2} \left( \frac{\partial f(xi, \theta)}{\partial \theta} \right){\theta=\theta0}^T \left( \frac{\partial f(xi, \theta)}{\partial \theta} \right){\theta=\theta0} ) where ( f ) is the kinetic model equation.

- Use optimal design software (e.g.,

PopED,PFIM) to find the design ( \xi^* ) that maximizes ( \det(FIM(\theta_0, \xi)) ). The output will be a set of optimal support points and the proportion of replicates at each point.

- Design Validation and Robustness:

- Evaluate the D-efficiency of a simpler, more practical design (e.g., a full factorial grid) relative to the optimal design.

- Perform a robustness check by recomputing the optimal design using slightly perturbed nominal parameters. A robust design will maintain high efficiency across this range.

Protocol 3: Implementing an Optimal Model Discrimination Design This protocol is followed when the primary goal is to determine which of several rival models is correct.

- Specify Rival Models:

- Define the competing models, e.g., Model 1: Competitive Inhibition; Model 2: Non-competitive Inhibition [31].

- For each model, provide nominal parameters from Protocol 1.

- Compute Discriminating Design:

- Use a criterion tailored for discrimination, such as T-optimality or Ds-optimality [31].

- T-optimality maximizes the integrated squared difference between the predictions of the two rival models.

- Optimize the design ( \xi ) to maximize this criterion using specialized software or algorithms.

- Execute and Analyze Discrimination Experiment:

- Run the enzyme assays according to the computed optimal design points.

- Fit the collected data to each rival model.

- Use statistical tests (e.g., likelihood ratio test, AIC/BIC comparison) to select the best-fitting model, benefiting from the enhanced discriminatory power of the optimal design.

Diagram: Optimal Design and Parameter Estimation Workflow The following workflow diagram integrates the protocols, showing the iterative process from initial setup to final parameter estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents and Materials

Implementing optimal designs for enzyme studies requires specific, high-quality materials. The following table details essential reagent solutions and their functions.

| Item Name | Specification / Preparation | Primary Function in OED |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Stock Solution | High-purity compound dissolved in assay buffer at a concentration well above the expected (Km) (e.g., 50-100x (Km)). Filter-sterilized. | To create the precise range of concentrations specified by the optimal design, from very low to saturating levels [31] [5]. |

| Inhibitor Stock Solution (for inhibition studies) | High-purity inhibitor dissolved in DMSO or assay buffer. Concentration should allow addition of small volumes to achieve the high end of the design range without perturbing reaction conditions. | To systematically vary inhibitor concentration as per the 2D optimal design ([S], [I]) for parameter estimation or model discrimination [31]. |

| Enzyme Stock Solution | Purified enzyme in a stable storage buffer (e.g., with glycerol). Aliquoted and stored at -80°C. Activity should be precisely determined in a pilot assay. | The catalyst concentration must be constant and limiting across all design points to ensure initial velocity measurements are valid for Michaelis-Menten analysis. |

| Assay Buffer | A buffered system (e.g., Tris, phosphate) at optimal pH, ionic strength, and temperature for the enzyme. May include essential cofactors (Mg²⁺, NADH). | Maintains consistent chemical environment across all design points, a critical assumption for interpreting kinetic data from optimally spaced samples. |

| Detection Reagent | Substance that allows quantitative measurement of product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., chromogen, fluorophore, coupled enzyme system). Must have a linear response over the expected product range. | Enables accurate measurement of the initial velocity response variable at each optimal design point, forming the dataset for parameter estimation. |

From Theory to Bench: Implementing FIM-Optimal Designs for Enzyme Experiments

The optimization of experimental design for parameter estimation in enzyme kinetics represents a critical frontier in quantitative biology and drug development. This article details a computational pipeline that integrates kinetic modeling with Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) analysis to guide efficient experimentation. Framed within a broader thesis on information-theoretic experimental design, these application notes provide protocols for constructing models, calculating the FIM, and optimizing experimental conditions to minimize parameter uncertainty. The methodologies enable researchers to systematically maximize information gain from resource-intensive experiments, with direct applications in characterizing therapeutic enzyme targets and metabolic pathways [18] [33] [34].

This work is situated within a research thesis dedicated to advancing Fisher information matrix enzyme experimental design. The core thesis posits that the strategic planning of experiments based on the quantitative information content of data can dramatically improve the precision of kinetic parameter estimation for enzymatic systems. Traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches are inefficient and often fail to reveal parameter correlations or identifiability issues [18]. By contrast, a model-based design of experiments (MBDoE) using the FIM provides a rigorous mathematical framework to predict which experimental measurements—such as substrate concentrations, sampling timepoints, or reaction conditions—will most effectively reduce the uncertainty in estimated parameters like (Km) and (V{max}) [18] [34]. This pipeline is foundational for research aiming to accurately characterize enzyme inhibition, validate drug-target interactions, and understand metabolic dysregulation in disease [33].

Foundational Quantitative Data in FIM-Based Experimental Design

The efficacy of FIM-based design is demonstrated by its quantitative impact on parameter estimation benchmarks. The following tables summarize key performance data from foundational and contemporary studies.

Table 1: Performance of FIM-Optimized Designs for Michaelis-Menten Kinetics This table compares the theoretical lower bounds on parameter estimation variance for batch versus substrate-fed-batch experimental designs, as derived from FIM analysis [18].

| Experimental Design | Parameter | Cramér-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) Improvement | Key Design Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Batch | ( \mu{max} ) (Vmax) | Baseline (100%) | Initial substrate concentration only |

| Substrate Fed-Batch | ( \mu{max} ) (Vmax) | Reduced to 82% of batch value | Small, continuous substrate feed |

| Standard Batch | ( K_m ) | Baseline (100%) | Initial substrate concentration only |

| Substrate Fed-Batch | ( K_m ) | Reduced to 60% of batch value | Small, continuous substrate feed |

Table 2: Optimized Experimental Parameters from Information-Theoretic Design This table lists optimal experimental parameters derived from maximizing mutual information (related to FIM) for a hyperpolarized MRI study of pyruvate-to-lactate conversion kinetics, an enzyme-mediated process [34].

| Optimized Variable | Optimized Value | Application Context | Resulting Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate excitation flip angle | 35 degrees | HP (^{13})C-pyruvate MRI | Maximizes mutual info for rate constant (k_{PL}) |

| Lactate excitation flip angle | 28 degrees | HP (^{13})C-pyruvate MRI | Maximizes mutual info for rate constant (k_{PL}) |

| Design Criterion | Mutual Information | Kinetic model of metabolite conversion | Directly accounts for prior parameter uncertainty |

Detailed Application Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Kinetic Model Development and Parameter Identifiability Pre-Screening

Objective: To construct a preliminary kinetic model and assess which parameters are theoretically identifiable before experimentation [35].

Materials: Systems Biology software (COPASI, MATLAB), symbolic computation tool (MATLAB Symbolic Toolbox, Mathematica).

Procedure:

- Model Formulation: Encode the hypothesized enzyme mechanism (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, allosteric, ping-pong) into a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Represent the state variables (e.g., [S], [P], [ES]) and parameters ((k{cat}), (Km), (k{on}), (k{off})).

- Structural Identifiability Analysis: Apply a symbolic tool to compute the Taylor series expansion of the observable model outputs. Analyze the resulting coefficients to determine if a unique mapping exists between the parameters and the idealized, noise-free output. Parameters yielding non-unique mappings are structurally unidentifiable and the model must be re-parameterized [35].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Calculate local sensitivity coefficients (S{ij} = (\partial yi/\partial \thetaj)(\thetaj / yi)) for model outputs (yi) (e.g., product concentration) with respect to parameters (\theta_j). Parameters with near-zero sensitivity across the experimental domain will be practically unidentifiable and may be fixed to literature values.

Protocol 3.2: Fisher Information Matrix Calculation and Local Design

Objective: To compute the FIM for a given kinetic model and experimental design, enabling the prediction of parameter estimation precision [18] [34].

Materials: Parameter values from Protocol 3.1, proposed design vector (D) (e.g., timepoints, initial conditions), computational script for numerical integration and differentiation.

Procedure:

- Define Design & Model Output: Specify the design vector (D = [t1, t2, ..., tn; S0^1, S0^2, ...]). Using the ODE model from Protocol 3.1, simulate the observable output (y(ti, \theta)) for each condition in (D).

- Compute Sensitivity Matrix: Numerically calculate the sensitivity matrix (X), where each element (X{ij} = \partial y(ti, \theta) / \partial \theta_j). This is often done via finite differences or solving the sensitivity ODE system.

- Assemble the FIM: For a scalar output with measurement error variance (\sigma^2), compute the FIM as (FIM(\theta, D) = X^T \Sigma^{-1} X), where (\Sigma) is the covariance matrix of the measurement errors (often (\sigma^2 I)). The FIM is an (n{\theta} \times n{\theta}) matrix, where (n_{\theta}) is the number of parameters.

- Evaluate Design Quality: Calculate the determinant ((D)-optimality) or trace ((A)-optimality) of the FIM, or the inverse of its trace ((E)-optimality). These scalar metrics quantify the total information content; a larger value indicates a more informative design.

Protocol 3.3: FIM-Based Sequential Experimental Design and Optimization

Objective: To iteratively optimize the experimental design (D) by maximizing a criterion of the FIM, then update parameter estimates with new data [35] [34].

Materials: Initial parameter estimates (\theta_0), preliminary data set (optional), optimization software.

Procedure:

- Initialize: Begin with an initial design (D0) (e.g., from literature) and parameter estimate (\theta0).

- Optimization Loop: a. Compute Optimal Design: Solve the optimization problem: (D^* = \arg\maxD \Psi[FIM(\thetak, D)]), where (\Psi) is an optimality criterion (e.g., (D)-optimal). Constraints (e.g., total time, substrate cost) are incorporated here [18]. b. Execute Experiment: Perform the experiment according to the optimized design (D^*) and collect new data. c. Re-estimate Parameters: Fit the kinetic model to the aggregated data set (all prior data plus new data) to obtain updated parameter estimates (\theta{k+1}). Use robust estimators to handle noise [35]. d. Check Convergence: Assess if parameter uncertainties (from the diagonal of (FIM^{-1})) are below a pre-defined threshold. If not, return to step (a) using (\theta{k+1}).

- Global vs. Local Search: For highly nonlinear models, use global optimization algorithms (e.g., Bayesian Optimization [35]) in Step 2a to avoid local maxima in the information landscape.

Protocol 3.4: A Posteriori Practical Identifiability and Uncertainty Analysis

Objective: To assess the reliability of parameter estimates obtained from the final fitted model and experimental data [35].

Materials: Final parameter estimates (\hat{\theta}), final dataset, profile likelihood calculation script.

Procedure:

- Compute Confidence Intervals: Approximate the parameter covariance matrix as (C \approx FIM(\hat{\theta})^{-1}). Calculate asymptotic confidence intervals for parameter (\thetai) as (\hat{\theta}i \pm t{\alpha/2, df} \sqrt{C{ii}}), where (t) is the t-statistic.

- Profile Likelihood Analysis: For each parameter (\thetai), construct a profile likelihood: repeatedly fit the model while constraining (\thetai) to a fixed value, allowing all other parameters to vary. Plot the optimized likelihood value against the fixed (\theta_i). A flat profile indicates practical non-identifiability.

- Validate with Hybrid Modeling (if applicable): In cases of partially known biology, embed the mechanistic model within a Hybrid Neural ODE (HNODE). Treat kinetic parameters as hyperparameters during a global search, then perform the identifiability analysis a posteriori on the mechanistic component to ensure the neural network did not obscure parameter identifiability [35].

Visualizations of the Computational and Experimental Workflow

Pipeline for FIM-Based Enzyme Experiment Design

The FIM-Based Experimental Design Cycle

Canonical Michaelis-Menten Kinetic Pathway & Parameters

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Resources

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example/Product | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Modeling & FIM Analysis | COPASI, MATLAB with Global Optimization Toolbox, Python (SciPy, PINTS) | Simulates kinetic ODEs, performs sensitivity analysis, calculates FIM, and executes design optimization algorithms [18] [35]. |

| Parameter Estimation & Identifiability | MEIGO Toolbox, PESTO (Parameter EStimation TOolbox), dMod (R) |

Provides robust global and local parameter estimation routines, profile likelihood calculation, and structural identifiability testing [35]. |

| Hybrid Mechanistic/ML Modeling | Julia DiffEqFlux, Python TorchDiffEq |

Implements Hybrid Neural ODEs (HNODEs) for systems with partially known biology, enabling parameter estimation where models are incomplete [35]. |

| Structural Biology & Target Validation | Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Provides near-atomic resolution structures of enzyme-ligand complexes, informing mechanism and validating parameters from kinetic studies (e.g., SUMO pathway enzymes) [36]. |

| Advanced Experimental Readouts | Hyperpolarized (^{13})C MRI | Enables real-time, in vivo measurement of metabolite conversion kinetics (e.g., pyruvate to lactate via LDH), generating data for FIM-based design optimization [34]. |

| Novel Therapeutic Modalities | PROTACs (Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras) | Serves as a complex kinetic system for drug discovery; understanding the ternary complex formation and degradation kinetics requires sophisticated parameter estimation [37]. |

The systematic design of fed-batch bioreactors is a cornerstone of modern industrial enzymology and biopharmaceutical production. This case study investigates the design of optimal substrate feeding strategies, framing the challenge within the broader research context of Fisher information matrix (FIM)-based experimental design. The primary objective of such research is to devise experiments that maximize information gain for precise kinetic parameter estimation (e.g., µ_max, K_s, q_p), thereby enabling robust model-predictive control of bioreactors [38] [39].

Traditional one-factor-at-a-time or standard design of experiments (DoE) approaches can be suboptimal for complex, nonlinear biological systems. In contrast, FIM-based design quantifies the information content of an experiment concerning the parameters of a postulated kinetic model. An optimal design maximizes a scalar function of the FIM (e.g., D-optimality), leading to experiments that yield parameter estimates with minimal variance [40]. Recent advances integrate this classical approach with Bayesian experimental design (BED) and machine learning [41] [40]. BED is a sequential, adaptive framework that uses prior knowledge to select the next most informative experimental condition, balancing exploration of the design space with exploitation of promising regions [40]. This synergy between FIM principles and modern computational optimization forms the theoretical backbone for the advanced feeding strategies explored herein.

This case study demonstrates the practical application of these principles through the fed-batch production of Mannosylerythritol Lipids (MEL), a high-value biosurfactant, using Moesziomyces aphidis. We analyze how model-informed feeding policies—contrasted with heuristic methods—dramatically improve key performance indicators like volumetric productivity and final titer [42].

The impact of different feeding strategies on process outcomes is substantial. The following tables summarize quantitative data from key studies, highlighting the superiority of optimized fed-batch operations over simple batch processes.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Batch vs. Optimized Fed-Batch for MEL Production [42]

| Process Parameter | Batch Process | Exponential Fed-Batch | Optimized Oil-Fed Fed-Batch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max. Dry Biomass (g/L) | 4.2 | 10.9 – 15.5 | Not Specified |

| MEL Volumetric Productivity (g/L·h) | 0.1 | Up to ~0.4 | Sustained high rate |

| Final MEL Concentration (g/L) | Significantly lower | Up to 50.5 (with residual FA) | 34.3 (pure extract) |

| Process Duration (h) | ~140 | ~170 | ~170 |

| Key Outcome | Low biomass, low productivity | 2-3x biomass, 4x productivity, impure product | High purity (>90% MEL), efficient substrate use |

Table 2: Evaluation of Glycerol Feeding Strategies for Recombinant Enzyme Production in P. pastoris [43]

| Feeding Strategy | Max. Biomass (g/L) | Volumetric Enzyme Activity (U/L) | Volumetric Productivity (U/L·h) | Process Duration (h) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DO-Stat Fed-Batch | Lower | Higher (20.8% > engineered) | Lower | 155 | Prevents oxygen limitation |

| Constant Feed Fed-Batch | Higher | High (13.5% > engineered) | Higher | 59 | Shorter process, higher productivity |

Table 3: Results of Medium Optimization for Ligninolytic Enzyme Production [44]

| Optimized Factor | Optimal Value | Resulting Enzyme Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C/N) Ratio | 7.5 | Most statistically significant positive factor |

| Copper (Cu²⁺) | 0.025 g/L | Acts as laccase cofactor |

| Manganese (Mn²⁺) | 1.5 mM | Inducer for MnP |

| Enzyme Cocktail Yield (After Fed-Batch & Concentration) | ||

| Laccase (Lac) | 4 × 10⁵ U/L | |

| Manganese Peroxidase (MnP) | 220 U/L | |

| Total Protein | 2.5 g/L |

Core Principles and Kinetic Framework for Fed-Batch Optimization

Optimal feeding strategy design is grounded in microbial kinetics and mass balances. The state of a fed-batch bioreactor is described by the concentration of biomass (X), substrate (S), product (P), and the culture volume (V). The system dynamics are governed by [45] [38]:

d(XV)/dt = µ(S) * X * V

d(SV)/dt = F * S_in - (1/Y_(X/S)) * µ(S) * X * V

d(PV)/dt = q_p(µ) * X * V

dV/dt = F

Where µ(S) is the substrate-dependent specific growth rate (often Monod kinetics: µ = µ_max * S / (K_s + S)), Y_(X/S) is the biomass yield coefficient, q_p is the specific product formation rate, F is the feed rate, and S_in is the substrate concentration in the feed.

The optimal control problem is to find the feeding trajectory F(t) that maximizes a predefined objective function (e.g., final product amount, productivity) subject to constraints (e.g., reactor volume, oxygen transfer rate). Analytical solutions for F(t) can be derived using Pontryagin's Maximum Principle, often resulting in a sequence of batch, exponential feed, and possibly singular control arcs [38]. In practice, this translates to multi-phase strategies [45]:

- Batch Phase: Achieve rapid biomass accumulation at

µ_max. - Exponential Fed-Batch: Maintain a specific growth rate (

µ_set) that maximizesq_p, increasing biomass while avoiding catabolite repression. - Limited/Critical Fed-Batch: Once a reactor constraint (e.g., dissolved oxygen

pO₂hits a lower limit) is reached, reduceµ_setto trade lower productivity for further increases in biomass concentration [45].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol is designed to maximize final product titer by structuring the process into distinct kinetic phases.

- Objective: To maximize the final concentration of a target metabolite (e.g., MEL) by sequentially optimizing for biomass growth, specific productivity, and total biomass concentration.

- Key Kinetic Parameters Required:

µ_max,Y_(X/S,max), maintenance coefficient (m_s), and the functionq_p = f(µ). - Procedure:

- Inoculum and Batch Phase:

- Prepare a defined mineral salt medium with a primary carbon source (e.g., glucose). Inoculate with the production organism (e.g., M. aphidis spore suspension or pre-culture).

- Allow the culture to grow in batch mode with unlimited substrate. Monitor biomass (via dry cell weight or optical density) and substrate concentration.

- Calculate

µ_maxandY_(X/S,max)from this batch data [45].

- Exponential Fed-Batch Phase Initiation:

- Upon batch substrate depletion, initiate feeding. The initial feed rate

F_0is calculated based on the current biomass (X_0), volume (V_0), target growth rate (µ_set), and feed substrate concentration (S_in) [45]:F_0 = (µ_set / Y_(X/S,abs) + m_s) * (X_0 * V_0) / S_in. - The feed rate is increased exponentially over time:

F_t = F_0 * exp(µ_set * t). - The

µ_setfor this phase should be set at the value (µ_qp,max) that maximizes the specific product formation rateq_p, as determined from prior characterization experiments [45].

- Upon batch substrate depletion, initiate feeding. The initial feed rate

- Transition to pO₂-Limited Fed-Batch: