Cell-Free Enzymatic Systems: A Transformative Platform for Bioproduction and Drug Development

Cell-free enzymatic systems (CFES) have emerged as a powerful and flexible platform for bioproduction, bypassing the constraints of living cells.

Cell-Free Enzymatic Systems: A Transformative Platform for Bioproduction and Drug Development

Abstract

Cell-free enzymatic systems (CFES) have emerged as a powerful and flexible platform for bioproduction, bypassing the constraints of living cells. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of CFES, from core definitions and system types to their inherent advantages. It delves into practical methodologies and cutting-edge applications, including the synthesis of therapeutics, enzymes, and complex natural products. The content further offers actionable troubleshooting guidance and a comparative analysis of major CFES platforms to inform experimental design. Finally, it synthesizes key takeaways and explores the future trajectory of CFES in accelerating biomedical research and clinical translation, highlighting its role in rapid prototyping, personalized medicine, and decentralized biomanufacturing.

What Are Cell-Free Systems? Core Concepts and inherent Advantages

Cell-free systems (CFS) are in vitro biochemical platforms that utilize cellular extracts or purified biological components to replicate complex biological processes—such as protein synthesis, metabolic pathways, and gene expression—outside of intact living cells [1]. By removing the physical barrier of the cell wall and eliminating the requirement for cellular viability, these systems provide direct, unrestricted access to the inner workings of the cell [2] [3]. This open nature offers researchers an unprecedented level of control and freedom of design, enabling the precise manipulation of biochemical environments that would be impossible or impractical within living organisms [3].

These systems can be broadly classified into two primary types. Cell extract-based systems utilize crude or semi-purified lysates derived from whole cells, providing a complex mixture of endogenous components that support processes like transcription and translation [1]. These extracts can be sourced from prokaryotes such as Escherichia coli or eukaryotes like wheat germ, rabbit reticulocytes, and insect cells [4] [1]. In contrast, purified component-based systems are assembled from individually purified or recombinantly produced biomolecules. The seminal example is the PURE (Protein synthesis Using Recombinant Elements) system, a fully reconstituted platform comprising 31 defined protein factors derived from E. coli that allows for customizable reactions with minimal off-target activity [1]. This piece will explore the historical development, current applications, and detailed methodologies that define modern cell-free enzymatic systems, providing a foundational resource for production research.

Historical Development and Fundamental Principles

The origins of cell-free systems trace back to a landmark discovery at the close of the 19th century. In 1897, German chemist Eduard Buchner demonstrated that a cell-free yeast extract could convert sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide, establishing for the first time that enzymes could catalyze complex biochemical reactions independently of viable cells [1] [3]. This work, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1907, challenged the prevailing vitalist views of the time and laid the conceptual groundwork for all subsequent in vitro biochemistry [1].

The mid-20th century saw the scope of cell-free systems expand dramatically into the realm of protein synthesis. A pivotal achievement came in 1961, when Marshall Nirenberg and Heinrich Matthaei employed an E. coli S30 extract to decipher the genetic code. By adding synthetic polyuridylic acid (poly-U) RNA to the extract and observing the synthesis of polyphenylalanine, they conclusively demonstrated that the codon UUU encodes the amino acid phenylalanine [1]. This breakthrough, for which Nirenberg later received a Nobel Prize, highlighted the immense utility of cell-free systems for unraveling fundamental biological mechanisms and cemented their role in molecular biology [1] [3]. The following decades witnessed the refinement of eukaryotic cell-free systems, such as rabbit reticulocyte lysates for studying hemoglobin synthesis, and continuous technical optimizations that boosted protein yields from micrograms to milligrams per milliliter [1]. The pursuit of greater control and definition culminated in 2001 with the development of the PURE system by Takuya Ueda, representing a full transition from crude extracts to a fully reconstituted, defined platform for protein production [1].

At their core, all cell-free systems operate on the principle of harnessing and recombining the molecular machinery of the cell. The fundamental "reactor" requires a set of essential components, as detailed below.

Diagram 1: Core functional components of a generic cell-free system and their primary outputs.

The energy to drive these thermodynamically unfavorable processes, particularly the ribosome's activity during translation, is supplied by the hydrolysis of nucleoside triphosphates. The core energy-yielding reactions are [1]:

- ATP Hydrolysis: ( \text{ATP} + \text{H}2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{ADP} + \text{P}i + \text{energy} )

- GTP Hydrolysis: ( \text{GTP} + \text{H}2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{GDP} + \text{P}i + \text{energy} ) To prevent rapid energy depletion, cell-free reactions are typically supplemented with energy regeneration systems, such as the creatine phosphate/creatine kinase couple, which efficiently recycles ATP and GTP from their spent forms, ADP and GDP [1].

Current Applications in Production Research

Biomanufacturing of Therapeutics and Proteins

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) has established itself as a powerful platform for the production of therapeutic proteins and other valuable biologics. The open reaction environment is particularly advantageous for expressing proteins that are toxic to host cells, require incorporation of non-canonical amino acids, or are difficult to fold in conventional cellular systems [2] [3]. Recent advances have resolved initial challenges related to protein folding and post-translational modifications, paving the way for the synthesis of more complex protein therapeutics [2]. The scalability of CFPS has been demonstrated impressively, with some production reactions reaching volumes of 100 to 1000 liters, moving the technology firmly into the commercial sphere [2]. For instance, the company Sutro Biopharma has leveraged cell-free expression for the synthesis of antibody-drug conjugates and other innovative therapeutics, highlighting the industrial viability of this approach [5].

Prototyping Metabolic Pathways and Bioproduction

A highly impactful application of cell-free systems is the rapid design-build-test cycling of synthetic metabolic pathways. Cell extracts provide a near-native metabolic context without the confounding variables of cell growth, division, or genetic regulation, allowing researchers to characterize enzyme combinations and optimize pathway flux with remarkable speed [6] [7]. This "cell-free prototyping" can accurately predict in vivo performance, dramatically accelerating metabolic engineering projects. A seminal example is the engineering of Clostridium autoethanogenum, a slow-growing anaerobic bacterium with limited genetic tools. By prototyping over 200 unique biosynthesis pathways in E. coli extracts, researchers were able to identify optimal enzyme homologs and designs, leading to successfully engineered C. autoethanogenum strains with increased titers of target chemicals like butanol and 3-hydroxybutyrate [7]. This approach compressed what would have been years of in vivo work into a matter of weeks.

Next-Generation Diagnostics and Biosensors

The biosafe, stable, and programmable nature of cell-free systems, particularly when lyophilized (freeze-dried), has enabled their deployment outside laboratory settings for diagnostic applications [2]. These freeze-dried cell-free (FD-CF) reactions can be stored at room temperature for over a year and activated on demand by adding water, making them ideal for distributed, low-cost sensing [2]. A transformative innovation in this field was the incorporation of toehold switches, a class of synthetic riboregulators that can be designed to detect virtually any RNA sequence with high specificity [2]. This technology was famously deployed during the 2016 Zika virus outbreak, where paper-based FD-CF sensors detected all global strains of the virus at clinically relevant concentrations (down to 2.8 femtomolar) and could distinguish viral genotypes with single-base resolution [2]. More recently, this platform has been adapted for quantitative detection of gut bacteria and for diagnosing Clostridium difficile infections, demonstrating its versatile potential in clinical diagnostics [2].

Table 1: Key Applications of Cell-Free Systems in Production Research

| Application Area | Key Technology/System | Performance/Impact | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic Protein Production | E. coli CFPS; Eukaryotic extracts | Scale demonstrated up to 1000 L [2]; Yields >1 g/L for select proteins [3] | Bypasses cellular toxicity; enables non-canonical amino acid incorporation |

| Metabolic Pathway Prototyping | E. coli cell extracts for pathway assembly | 200+ pathways prototyped in weeks; high correlation (R² ~0.75) with in vivo performance [7] | Rapid design-build-test cycles; decouples pathway flux from cell growth |

| Portable Diagnostics | Freeze-dried, paper-based CF reactions with toehold switches | Detection of Zika virus down to 2.8 femtomolar; single-base mismatch specificity [2] | Room-temperature storage; biosafe; deployable in low-resource settings |

| Expanded Chemical Production | Purified enzyme systems; non-model organism extracts | Synthesis of novel chemicals, biofuels, and materials not found in nature [3] [7] | Access to non-natural chemistry; utilization of non-standard substrates (e.g., C1 gases) |

Essential Protocols for Production Research

Protocol: Preparation of an E. coli-Based Cell Extract for Protein Synthesis

This protocol describes the generation of a crude cell lysate from E. coli, which forms the core of a highly productive cell-free protein synthesis system [4].

- Cell Cultivation and Harvest: Inoculate a rich medium (e.g., 2xYTPG) with an appropriate E. coli strain (e.g., A19 or BL21 Rosetta2). Grow the culture at 37°C with vigorous shaking until it reaches the mid-exponential growth phase (OD600 of ~0.6). A key systems biology study found that the proteome of the harvested cells significantly impacts the final lysate's productivity, with harvest time being a critical parameter [4]. Chill the culture rapidly on ice and pellet the cells by centrifugation at 4°C.

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend the cell pellet in a lysis buffer (e.g., S30 Buffer A: 10 mM Tris-acetate, 14 mM magnesium acetate, 60 mM potassium glutamate, pH 8.2). Lyse the cells using a high-pressure homogenizer (e.g., French Press) or by bead beating. Sonication is also a common method. The goal is to achieve thorough cell disruption while minimizing heat generation.

- Clarification and Run-Off Reaction: Centrifuge the lysate at 30,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris and insoluble fractions, including membranes. The resulting supernatant is the S30 extract. Incubate the S30 extract for 80 minutes at 37°C with a "run-off" reaction mixture (containing amino acids, nucleotides, and salts) to allow for the degradation of endogenous mRNA and the completion of endogenous protein synthesis. This step reduces background activity.

- Dialysis and Storage: Dialyze the extract extensively against a storage buffer (e.g., S30 Buffer A) to remove small molecules and exchange the buffer. Aliquot the clarified, dialyzed extract, flash-freeze it in liquid nitrogen, and store it at -80°C. Properly prepared extracts remain active for years.

Protocol: Running a Batch-Mode Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Reaction

This protocol utilizes the prepared E. coli extract to express a protein of interest from a DNA template [4].

- Reaction Assembly: On ice, combine the following components in a microcentrifuge tube to a final volume of 15 μL:

- 5 μL of S30 E. coli extract (33% v/v of final reaction).

- 1 μL of plasmid DNA (25-50 ng/μL) or PCR product encoding the gene of interest under a T7 or native promoter.

- 9 μL of Energy/Mix solution. A standard 10x energy mix contains:

- 1.2 mM ATP and GTP each; 0.8 mM CTP and UTP each

- 200 mM Glutamic acid (potassium salt)

- 10 mM of each of the 20 canonical amino acids

- 250 mM Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) or a creatine phosphate-based energy regeneration system

- 2 mg/mL E. coli tRNA

- 100 mM HEPES buffer, pH 8.0

- 175 mM Potassium glutamate

- 20 mM Magnesium glutamate

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 30°C or 37°C for 2-8 hours, depending on the protein and the desired yield. Protein synthesis is typically most active during the first few hours before resources are depleted or inhibitory byproducts accumulate.

- Analysis: After incubation, the reaction can be analyzed directly by SDS-PAGE to check for protein synthesis, or the protein can be purified for functional assays. For quantification, a radiolabeled amino acid (e.g., 14C-Leucine) can be included in the reaction, and the incorporated radioactivity can be measured using a scintillation counter after precipitation with trichloroacetic acid (TCA).

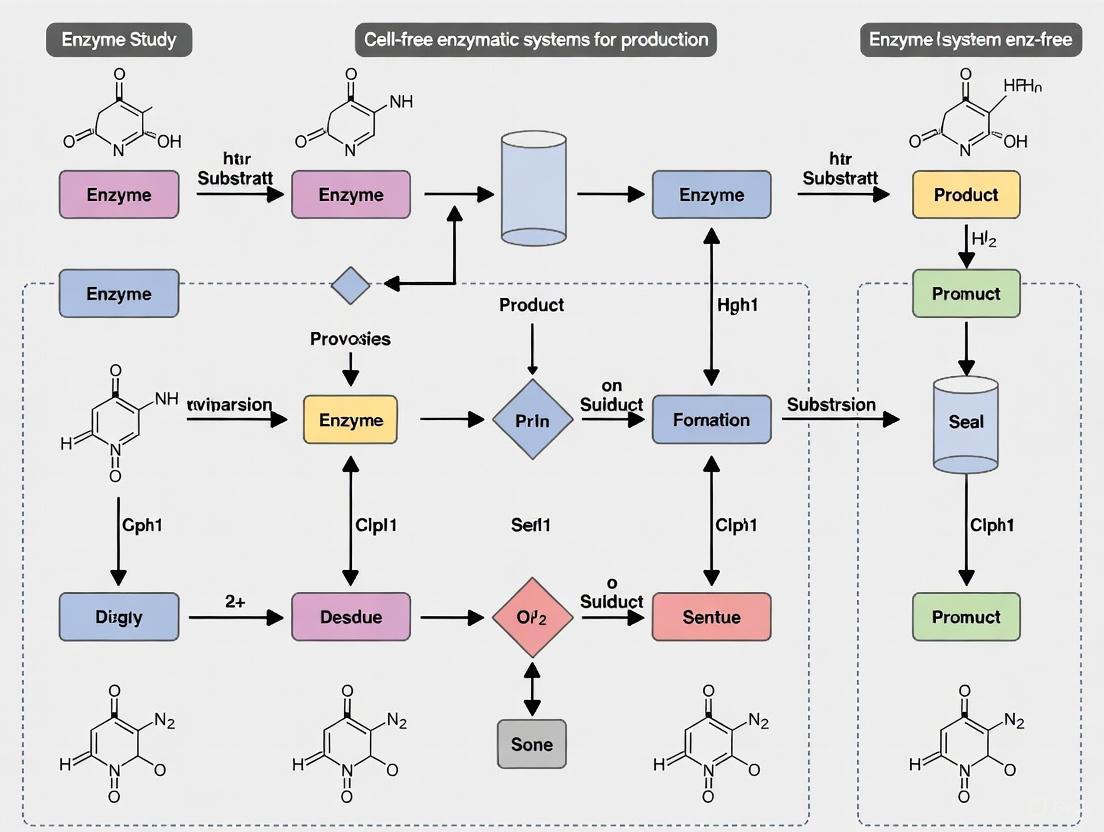

The workflow for creating and utilizing a cell-free system for production research is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: A generalized workflow for establishing and applying cell-free systems for production research, from system selection to final application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The consistent performance of cell-free systems relies on the quality and preparation of its core components. The table below details essential reagents and materials, drawing from both historical standards and modern commercial solutions referenced in the literature.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Cell-Free Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Source Organism/Strain | Provides the foundational enzymatic machinery for the system. | E. coli (e.g., A19, BL21): High productivity, well-established [4]. Wheat Germ Extract: Eukaryotic folding/modifications [1]. Rabbit Reticulocyte Lysate: Mammalian-like environment [1]. |

| Commercial Cell-Free Kit | Provides a pre-optimized, reproducible system for specific applications. | PURExpress (NEB): A defined, PURE-system-based kit [1]. myTXTL (Arbor Biosciences): A commercial S30-type extract [4]. |

| Energy Regeneration System | Sustains reactions by regenerating ATP/GTP from ADP/GDP. | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) & Pyruvate Kinase: Common but can lead to inhibitory phosphate accumulation. Creatine Phosphate & Creatine Kinase: Highly efficient, widely used system [1]. |

| Cofactor Supplements | Enhance yield and extend reaction lifetime by mitigating bottlenecks. | Putrescine & Beta-Alanine: Shown to improve protein production nearly three-fold in some systems [4]. NAD+, CoA: Essential for metabolic pathway reactions. |

| Magnetic Beads (for cleanup) | Purify and size-select DNA or reaction products post-synthesis/conversion. | AMPure XP, NEBNext Sample Purification Beads: Critical for enzymatic conversion workflows; bead-to-sample ratio impacts DNA recovery [8]. |

Performance Data and System Comparisons

The utility of any platform technology is ultimately judged by its quantitative performance. The table below synthesizes key metrics for various cell-free systems as reported in the literature, providing a benchmark for researchers.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of Different Cell-Free Systems

| System Type | Primary Application | Reported Yield/Performance | Key Limitation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli S30 Extract | Protein synthesis; Metabolic prototyping | Protein: 100 - 500 μg/mL (batch); >1 g/L with optimization [1] [3]. Metabolites: Up to ~1 M [7]. | Batch-to-batch variability; presence of nucleases/proteases [4]. |

| PURE System | High-fidelity protein production; Unnatural amino acid incorporation | Protein: ~160 μg/mL/h; typical yields of 100-300 μg/mL in batch [1]. | High cost; lacks some chaperones and complex folding machinery of crude extracts. |

| Wheat Germ Extract | Eukaryotic protein production, especially with glycosylation | Lower protein productivity than E. coli systems, but superior for complex eukaryotic proteins [4]. | Lower overall productivity; more complex preparation. |

| Freeze-Dried (FD-CF) System | Diagnostics; portable biosensing | Stable for >1 year at room temperature [2]. Detection sensitivity for Zika virus: 2.8 femtomolar [2]. | Limited reaction lifetime once rehydrated; typically single-use. |

| Enzymatic DNA Conversion | DNA methylation analysis for diagnostics | Cytosine conversion efficiency: 99-100%. DNA recovery: 34-47% (lower than bisulfite conversion) [8]. | Lower DNA recovery compared to bisulfite method, impacting sensitivity [8]. |

Cell-free systems are in vitro tools widely used to study biological reactions that happen within cells apart from a full cell system, thus reducing the complex interactions typically found when working in a whole cell [9]. These systems provide a simplified biological environment that offers researchers unparalleled control over reaction conditions, enabling the precise examination of cellular processes like protein synthesis and metabolic pathway operation. The core value of cell-free technologies lies in their ability to bypass the constraints of cellular membranes, allowing direct access to and manipulation of the reaction environment without the homeostatic considerations required to keep cells alive [10]. This technology has evolved significantly since Eduard Buchner's pioneering work with yeast extracts in the late 19th century, which demonstrated that biochemical reactions could occur outside living cells [9].

Cell-free systems have become indispensable in modern biotechnology and synthetic biology, particularly for production research where they enable more efficient biomanufacturing, faster prototyping of genetic circuits, and detailed study of metabolic pathways. The open nature of these systems allows for real-time monitoring and manipulation of biochemical reactions that would be impossible within intact cells. As platforms for production research, cell-free systems dedicate all energy and resources specifically to the synthesis of target molecules rather than diverting resources to cellular maintenance and growth, resulting in potentially higher yields and more controlled production processes [10]. This article examines the two primary classifications of cell-free systems—cell extract-based and purified enzyme-based—providing detailed comparisons, protocols, and implementation guidance for research applications.

System Classifications and Comparative Analysis

Cell-free systems are broadly divided into two primary classifications based on their composition and preparation methodology: cell extract-based systems and purified enzyme-based systems. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different research and production applications.

Cell Extract-Based Systems

Cell extract-based systems utilize the internal molecular machinery obtained by lysing cells and collecting the supernatant containing enzymes, ribosomes, cofactors, and other cellular components [9]. These systems are essentially "cellular soups" that maintain much of the native enzymatic complexity of the source organism while eliminating the barrier of the cell membrane. Preparation typically involves growing source cells (commonly E. coli, wheat germ, or rabbit reticulocytes), harvesting them during maximum growth, lysing them using methods such as high-pressure homogenization, sonication, or bead vortexing, and then clarifying the lysate through centrifugation to remove cell debris [9] [11].

A key advantage of extract-based systems is their functional completeness, as they contain the full complement of natural enzymes, cofactors, and energy regeneration systems needed for complex multi-step biochemical processes [11]. This makes them particularly valuable for protein synthesis applications, where they provide all necessary transcription and translation components. However, these systems also contain degradative enzymes such as nucleases and proteases that can limit reaction longevity and product yield [9]. Researchers have addressed this through genetic engineering of source cells, such as creating E. coli strains with deletions of genes encoding problematic enzymes like endonuclease I (endA) to decrease DNA template degradation [11].

Purified Enzyme-Based Systems

In contrast to the complex mixtures found in extract-based systems, purified enzyme-based systems are reconstituted from individually purified components that are specifically selected and mixed to create a defined synthetic environment [9] [10]. This "bottom-up" approach offers precise control over system composition, allowing researchers to include only the enzymes and factors directly required for the target biochemical reaction while excluding degradative pathways and competing reactions.

The primary strength of purified enzyme systems is their highly defined nature, which eliminates batch-to-batch variability and provides a more predictable, engineerable platform for biochemical production [10]. Without nucleases, proteases, and other degradative enzymes present in crude extracts, these systems often demonstrate enhanced stability for sensitive reaction components like mRNA templates [9]. However, this approach requires extensive prior knowledge of the necessary pathway components and typically involves higher initial costs for enzyme purification or procurement.

Quantitative Comparison of System Performance

The following table summarizes key performance characteristics and applications of both system types, highlighting their respective advantages for different production research scenarios:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cell-Free System Types

| Parameter | Cell Extract-Based Systems | Purified Enzyme-Based Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation Complexity | Moderate | High |

| Cost | Lower (uses crude extracts) | Higher (enzyme purification/purchase) |

| Pathway Complexity | Suitable for complex, multi-step pathways | Better for defined, linear pathways |

| Yield Potential | High (natural enzyme complexes) | Variable (optimization dependent) |

| Reaction Longevity | Limited (degrades faster) | Extended (more stable) |

| Template Stability | Lower (nucleases present) | Higher (controlled environment) |

| Technical Barrier | Lower | Higher |

| Best Applications | Protein synthesis, metabolic engineering with unknown components | Controlled biomanufacturing, specialized incorporations |

Table 2: Metabolic Engineering Performance Metrics

| System Type | Maximum Production Rate Reported | Cofactor Turnover | Key Product Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Extract-Based | 11.3 g/L-h (2,3-butanediol) [11] | ~900 cycles [11] | 2,3-butanediol, n-butanol, hydrogen |

| Purified Enzyme-Based | Varies by system | Potentially higher with engineering | Starch from cellulose, specialized chemicals |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of E. coli-Based Cell Extract System

This protocol describes the preparation of a cell extract from E. coli for protein synthesis or metabolic engineering applications, based on established methodologies with optimization for high productivity [9] [11].

Materials and Equipment

- Source Strain: E. coli strain (e.g., A19 with deletions of tonA, endA, speA, tnaA, sdaA, sdaB, gshA to minimize unwanted side reactions) [11]

- Growth Medium: Appropriate rich medium (e.g., 2xYT)

- Lysis Buffer: 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.2), 14 mM magnesium acetate, 60 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)

- Equipment: High-pressure homogenizer (French Press or continuous unit) or sonicator, centrifuge capable of 30,000× g, shaking incubator

Procedure

Cell Growth: Inoculate the source strain into growth medium and incubate with vigorous shaking (200-250 rpm) at 37°C. Monitor growth and harvest cells during mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8) to ensure high ribosome content and metabolic activity [11].

Cell Harvest: Centrifuge culture at 5,000× g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Discard supernatant and wash cell pellet with lysis buffer. Repeat centrifugation and resuspend cells in a minimal volume of lysis buffer.

Cell Lysis: Utilize one of the following methods:

- High-Pressure Homogenization: Pass cell suspension through a French Press at approximately 20,000 psi [11].

- Sonication: Sonicate on ice using 30-second pulses with 30-second rest intervals until sample clarifies [11].

- Bead Vortexing: Use glass beads (0.1 mm diameter) and vortex vigorously for multiple cycles [11].

Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 12,000-30,000× g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris [11]. Carefully collect the supernatant (S30 extract).

Run-Off Reaction: Incubate the extract with energy mix (1.5 mM ATP, 0.3 mM each amino acid, 10 mM magnesium glutamate, 100 mM potassium glutamate, 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0) for 30-80 minutes at 37°C. This step depletes endogenous mRNA and improves subsequent protein synthesis efficiency [11].

Dialysis and Storage: Dialyze against fresh buffer to remove small molecules. Aliquot, flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C where extracts remain stable for multiple years [11].

Quality Assessment

- Measure total protein concentration (target: 30-50 mg/mL)

- Test protein synthesis activity using a reporter gene (e.g., green fluorescent protein)

- Confirm absence of live cells by plating on growth medium

Protocol 2: Assembling a Purified Enzyme System

This protocol outlines the assembly of a defined enzyme system for targeted bioconversion, using a minimal set of purified enzymes for precise pathway control.

Materials and Equipment

- Purified Enzymes: Commercially sourced or previously purified enzymes specific to the desired pathway

- Cofactors: ATP, NAD(H), NADP(H), Coenzyme A, and other required cofactors

- Energy Regeneration System: Creatine phosphate/creatine kinase or pyruvate kinase/phosphoenolpyruvate

- Reaction Buffer: System-specific optimized buffer (typically Tris or HEPES-based with magnesium and potassium salts)

Procedure

Pathway Design: Identify all required enzymes and cofactors for the target biochemical transformation. Consider enzyme kinetics, stability, and potential inhibitory interactions.

Enzyme Preparation: Obtain enzymes through:

- Commercial sources for common enzymes

- Heterologous expression and purification for specialized enzymes

- Confirm enzyme activity and concentration before use

System Assembly:

- Prepare master mix containing buffer, salts, and energy regeneration components

- Add cofactors at physiologically relevant concentrations (typically 0.1-1 mM)

- Introduce enzymes in the stoichiometric ratio optimized for the pathway flux

Reaction Initiation: Start the reaction by adding substrate(s). For continuous reactions, implement a substrate feeding strategy to maintain optimal concentrations.

Process Monitoring: Track reaction progress through:

- Substrate consumption (HPLC, enzyme assays)

- Product formation (appropriate detection methods)

- Cofactor recycling efficiency (spectrophotometric assays)

Optimization Considerations

- Determine optimal enzyme ratios for balanced pathway flux

- Identify potential bottleneck steps and adjust enzyme concentrations accordingly

- Test different energy regeneration systems for efficiency and cost-effectiveness

- Evaluate stabilizers (e.g., PEG) to enhance enzyme longevity

System Workflows and Functional Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the key preparation workflows and functional relationships for both cell-free system types.

Cell Extract System Preparation

Purified Enzyme System Assembly

Application-Specific Implementation

Protein Synthesis Applications

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) represents one of the most established applications for both system types. Extract-based systems, particularly those derived from E. coli, wheat germ, and rabbit reticulocytes, have been extensively used for protein production because they contain the complete translation machinery [9]. The Nirenberg and Matthaei experiment, which used a cell-free system with 30S extract from E. coli to incorporate radioactive amino acids into proteins, exemplifies this approach and was foundational to cracking the genetic code [9]. More recent advances, such as the continuous-flow system developed by Spirin et al., have significantly increased protein production yields in extract-based systems [9].

Purified enzyme systems offer distinct advantages for specialized protein synthesis applications, particularly when unnatural amino acids need to be incorporated. By omitting specific release factors (e.g., RF1) and carefully controlling the composition of the system, researchers can reprogram the genetic code to incorporate non-standard amino acids at desired positions [9]. This approach also enables specific labeling of amino acids for multidimensional NMR spectroscopy, as demonstrated by Kigawa et al., who successfully labeled amino acids in a system where natural amino acid metabolism was absent [9].

Metabolic Engineering Applications

Cell-free metabolic engineering (CFME) leverages both system types for the production of metabolites and other small molecules. Extract-based systems provide a complete metabolic network that can be manipulated for bioproduction. For example, Bujara et al. used glycolytic network extracts from E. coli to produce dihydroxyacetone phosphate while dynamically analyzing metabolite concentrations and optimizing enzyme levels [9]. The impressive catalytic efficiency of these systems is demonstrated by cofactor recycling, where cofactors can be used hundreds to thousands of times, significantly reducing production costs [11].

The modularity of purified enzyme systems makes them particularly valuable for pathway prototyping and optimization. Researchers can rapidly test different enzyme combinations and ratios to maximize product yield before implementing pathways in whole cells. Karim and Jewett demonstrated this approach by preparing separate extracts enriched for individual pathway enzymes, then mixing them in varying ratios to optimize n-butanol production [11]. This "mix-and-match" approach enables rapid iteration and optimization that would be much more time-consuming in vivo.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of cell-free systems requires careful selection of reagents and components. The following table outlines key solutions and materials essential for working with both system types:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cell-Free Systems

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Sources | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), Creatine phosphate, Acetyl phosphate | Drive ATP-dependent reactions; PEP historically common but creatine phosphate can be more cost-effective [9] |

| Cofactors | ATP, NAD(H), NADP(H), Coenzyme A, Thiamine pyrophosphate | Essential electron carriers and co-substrates for enzymatic reactions [11] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Protect synthesized proteins from degradation in extract-based systems [12] |

| Nuclease Inhibitors | RNaseOUT, DNase I | Protect DNA templates and mRNA in transcription-translation systems [11] |

| Amino Acid Mixtures | 20 standard L-amino acids | Building blocks for protein synthesis; typically included at 0.3-1 mM each [11] |

| Nucleotides | NTPs (ATP, GTP, UTP, CTP) | Substrates for RNA polymerase in transcription-coupled systems [10] |

| Salts & Buffers | Magnesium/potassium glutamate, HEPES/KOH | Maintain optimal ionic strength and pH for enzymatic activity [11] |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol | Maintain sulfhydryl groups in reduced state; stabilize enzyme activity [11] |

Cell-free systems represent a powerful platform for production research, with both cell extract-based and purified enzyme-based approaches offering complementary advantages. Extract-based systems provide a functionally complete environment that excels at complex tasks like protein synthesis and multi-step metabolic transformations, while purified enzyme systems offer precise control and defined composition ideal for optimized bioconversion and specialized applications. The choice between systems depends on research goals, with extract-based methods generally offering lower technical barriers and purified enzyme systems providing greater engineering control.

Emerging trends in cell-free biotechnology include the integration of machine learning for system optimization, development of more efficient energy regeneration modules, and implementation of automated high-throughput screening platforms [10]. These advancements are making cell-free systems increasingly attractive for industrial-scale biomanufacturing, particularly for the production of high-value proteins, metabolites, and customized therapeutics. As the field continues to evolve, the complementary use of both system types will enable researchers to tackle increasingly complex production challenges in biotechnology and pharmaceutical development.

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems, also referred to as cell-free expression systems (CFES), are in vitro platforms that utilize the biological machinery essential for transcription and translation—such as ribosomes, enzymes, and tRNAs—extracted from cells to synthesize proteins without the constraints of living organisms [13]. This technology has evolved from a basic biochemical tool used to decipher the genetic code into a robust biomanufacturing platform for protein production, enzyme engineering, and synthetic biology applications [14] [13].

The fundamental advantage of CFPS lies in its open reaction environment, which removes the biological barriers and regulatory complexities of living cells. This provides researchers with unprecedented control over the reaction conditions, direct access to the synthesis process, and the flexibility to produce proteins and biomolecules that are challenging or impossible to generate using traditional cell-based methods [15].

Comparative Advantages: A Data-Driven Analysis

The transition from cell-based to cell-free expression systems offers significant, quantifiable benefits across key performance metrics, including speed, yield, and application range. The tables below summarize these advantages based on current market data and peer-reviewed research.

Table 1: Key Performance Advantages of Cell-Free vs. Cell-Based Systems

| Performance Metric | Cell-Free Systems | Cell-Based Systems | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Synthesis Time | A few hours [16] | Several days to weeks [14] | Speed |

| Toxic Protein Production | Direct, efficient production [17] [15] | Limited by host cell viability [18] [15] | Flexibility & Range |

| Membrane Protein Production | Enabled with vesicle assistance [15] | Often results in misfolding or low yields [15] | Flexibility & Range |

| Reaction Control & Optimization | Direct, real-time control [15] | Limited by cellular homeostasis [15] | Control |

| High-Throughput Screening | Ideal for rapid prototyping [16] [18] | Slower and more resource-intensive [18] | Speed & Efficiency |

Table 2: Market Data Reflecting Adoption and Application of CFPS

| Market Segment | Market Share or Growth Rate | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Global CFPS Market (2024) | USD 315 - 269 million [16] [19] | Reflects the established commercial value of the technology. |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2034) | 8.63% - 8.07% [16] [19] | Indicates strong, sustained growth and future adoption. |

| Leading Application (2024) | Enzyme Engineering [16] [19] | Highlights use in designing and optimizing novel biocatalysts. |

| Fastest-Growing Application | High-Throughput Production [16] [19] | Aligns with the advantage of speed for drug discovery and screening. |

| Dominant End-User (2024) | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Companies [16] [19] | Underpins critical industry reliance for therapeutic development. |

Core Advantages in Detail

Enhanced Control and Flexibility

The open nature of CFPS reactions provides a level of control that is unattainable in living cells, primarily because there is no need to maintain cell viability [15].

- Direct Reaction Manipulation: Researchers can directly adjust critical parameters such as pH, temperature, and substrate concentration in real-time to optimize protein yield and folding [15]. The reaction buffer's composition can be precisely tuned, allowing for rapid optimization and parameter identification [15].

- Modular Component Integration: The system allows for the straightforward addition of cofactors, chaperones, and specialized enzymes to assist with protein folding and complex post-translational modifications (PTMs) [15]. For instance, the redox potential can be stabilized, and disulfide bond formation can be enhanced by adding enzymes like DsbC and glutathione buffers [15].

- Simplified Template Design: CFPS efficiently uses linear DNA templates, bypassing the time-consuming steps of cloning and chromosomal integration required for cell-based systems [14]. This significantly accelerates the "design-build-test" cycle for metabolic pathways and genetic circuits [7].

The following diagram illustrates how this open environment provides a more direct and controllable workflow compared to cell-based systems.

Superior Speed and Yield for Specific Applications

CFPS dramatically accelerates protein production and can achieve higher functional yields for proteins that are problematic in cell-based systems.

- Rapid Synthesis Timelines: Cell-free systems can produce proteins within a few hours, a process that typically takes days in living cells [16]. This speed is paramount in high-throughput applications, such as screening enzyme variants or generating protein libraries for drug discovery [16] [19].

- Production of Problematic Proteins:

- Toxic Proteins: CFPS is ideal for synthesizing proteins that are lethal to host cells, as there are no viability constraints [17] [15]. This allows for the high-yield production of antimicrobial peptides (e.g., cecropin, defensin) and cytotoxic agents for therapeutic use [13].

- Membrane Proteins: These proteins often misfold or exhibit low expression in vivo. CFPS, especially when integrated with vesicle systems like liposomes, facilitates the correct folding and integration of complex membrane proteins (e.g., G Protein-Coupled Receptors - GPCRs) into lipid bilayers, preserving their native structure and function [15].

- High-Yield Production of Complex Therapeutics: Advances in CFPS have enabled the synthesis of proteins with multiple disulfide bonds, a previous challenge. Through redox potential optimization, researchers have successfully produced functional proteins containing up to 24 disulfide bonds [15].

Expanded Functional and Production Flexibility

The flexibility of CFPS extends its utility beyond simple protein production to innovative applications in synthetic biology and therapeutic delivery.

- Incorporation of Non-Standard Amino Acids (NSAAs): The open system allows for the easy incorporation of NSAAs into proteins, enabling the creation of novel protein functions and properties not possible with canonical biology [19]. This is a key enabler for advanced biologics and enzyme engineering.

- Pathway Prototyping and Metabolic Engineering: CFPS is powerfully used to prototype and optimize complex multi-enzyme biosynthetic pathways in vitro before implementing them in living cells [7]. This approach drastically reduces development time for strains producing chemicals like butanol and acetone [7].

- On-Demand Biomanufacturing and Delivery:

- Therapeutic Manufacturing: CFPS systems can be freeze-dried for storage and rehydrated for use, facilitating point-of-care diagnostic applications and portable therapeutic production [14].

- Programmable Drug Delivery: The integration of CFPS with vesicle-based delivery platforms creates synergistic systems. These "synthetic cells" can be designed to produce and deliver therapeutic proteins in response to specific biological signals, enabling precise, targeted therapies [15].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for a Typical E. coli-Based CFPS Experiment

| Reagent / Component | Function in the System | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Extract (S30 Extract) | Source of core machinery: ribosomes, tRNAs, translation factors, and enzymes. | Prepared from E. coli strains like BL21. High ribosome content from fast-growing cells is crucial [13]. |

| Energy Source | Regenerates ATP to power transcription and translation. | Common systems use Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) or Creatine Phosphate [7]. |

| Amino Acids | Building blocks for protein synthesis. | Includes all 20 canonical amino acids; NSAAs can be added for specialized applications [19] [13]. |

| DNA Template | Encodes the gene of interest (GOI) for expression. | Can be a plasmid with a T7 promoter or a linear PCR product. Offers great flexibility [13]. |

| Polymerase (T7 RNA Pol) | Drives transcription of the GOI from the DNA template. | A standard for high-level expression in many CFPS systems [13]. |

| Cofactors & Salts | Essential for enzyme function and maintaining proper ionic strength. | Includes Mg²⁺, K⁺, NH₄⁺, and folinic acid [13]. |

| Energy Disulfide Buffer | Controls redox potential to enable correct disulfide bond formation. | Contains oxidized/reduced glutathione and the enzyme DsbC [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Production of a Functional Protein via E. coli-Based CFPS

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for producing a target protein, such as an enzyme or antibody fragment, using a standard E. coli extract-based CFPS system.

- Cell Culture:

- Inoculate a suitable E. coli strain (e.g., BL21) into a rich medium like 2xYT.

- Grow the culture at 37°C with vigorous shaking (≈200 rpm) to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 3-4). Critical: Fast growth ensures high ribosome content.

- Cell Harvest and Washing:

- Chill the culture on ice. Centrifuge at 4,000-5,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet cells.

- Discard the supernatant and wash the pellet with cold S30 Buffer (10 mM Tris-acetate pH 8.2, 14 mM magnesium acetate, 60 mM potassium acetate).

- Cell Lysis:

- Resuspend the pellet in a minimal volume of fresh S30 Buffer.

- Lyse the cells using a high-pressure homogenizer (e.g., French Press) or by bead beating. Note: Keep the suspension ice-cold throughout.

- Clarification and Run-Off Reaction:

- Centrifuge the lysate at 12,000-30,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris and insoluble particles.

- Carefully collect the supernatant (the S30 extract). Incubate it for 80 minutes at 37°C with gentle shaking to run-off endogenous mRNA and deplete residual energy.

- Dialysis and Storage:

- Dialyze the extract against a large volume of fresh S30 buffer overnight at 4°C.

- Aliquot the clarified extract, flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C.

Setting Up the CFPS Reaction

Prepare Reaction Mixture: Assemble the following components on ice to a final volume of 50 μL. Volumes can be scaled as needed.

Table 4: CFPS Reaction Master Mix Components

Component Final Concentration Volume (μL) for 50 μL rxn S30 Cell Extract 30-40% of reaction volume 15-20 μL HEPES/KOH pH 8.2 50-100 mM 5 μL of 10x stock Magnesium Acetate 10-15 mM To be optimized Potassium Glutamate 100-200 mM To be optimized Amino Acid Mix (All 20) 2 mM each 4 μL of 25 mM stock Energy Solution e.g., 20 mM PEP 5 μL of 200 mM stock NTPs (ATP, GTP, CTP, UTP) 2 mM each 4 μL of 25 mM stock DNA Template 10-20 μg/mL (plasmid) 1-2 μL T7 RNA Polymerase If using T7 promoter 0.5-1 μL Nuclease-Free Water To final volume To 50 μL Incubation:

- Mix the reaction gently and incubate at 30-37°C for 2-6 hours, depending on the target protein.

- Monitor protein yield over time by measuring fluorescence (if using a tagged reporter) or by taking aliquots for SDS-PAGE/Western blot analysis.

Downstream Analysis and Purification

- Analysis:

- Analyze expression by running reaction aliquots on SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie staining or Western blotting.

- Assess protein functionality using activity-specific assays (e.g., enzymatic activity, binding assays).

- Purification:

- Due to the lack of host cell contaminants, purification is often simplified.

- If the protein is His-tagged, purify it directly from the reaction mixture using Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) under native or denaturing conditions.

The following diagram summarizes the key advantages of CFPS and their interconnected relationships, forming a powerful rationale for its adoption.

Cell-free synthesis systems have emerged as a powerful platform for enzymatic production research, enabling the in vitro execution of complex biochemical processes without the constraints of the cell wall or the need to maintain cell viability [17]. These systems leverage the transcriptional and translational machinery of cells in a controlled test tube environment, offering unprecedented flexibility for engineering and optimization. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the three core components—the cell extract, the energy system, and the template—is fundamental to harnessing the full potential of cell-free technology. This application note details these essential elements and provides a validated protocol for implementing a cell-free protein synthesis system, with a specific focus on applications in enzyme engineering and the production of valuable small molecule pharmaceuticals [20].

The Core Components of a Cell-Free System

A functional cell-free reaction requires the precise combination of three essential components: a cellular extract that provides the core molecular machinery, an energy regeneration system to fuel the reaction, and a nucleic acid template that encodes the target protein or pathway. The synergistic interaction of these components is outlined in Figure 1 below.

Cellular Extract: The Enzymatic Workhorse

The cellular extract, or lysate, forms the foundation of the system, containing the essential macromolecular machinery required for protein synthesis and metabolism. It is prepared by lysing cells and removing membranes and debris, leaving behind the cytosolic and organelle components [21]. The choice of extract source is critical and depends on the specific application requirements, particularly the need for post-translational modifications.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Cell-Free Extract Types

| Extract Source | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli [21] [22] | Very high protein yield; Cost-effective; Robust | Lacks eukaryotic PTMs*; Codon usage differs from eukaryotes | High-throughput screening; Expression of non-eukaryotic proteins [20] |

| Wheat Germ [21] | High yield of large proteins; Low endogenous background | Lacks mammalian PTMs | Expression of cytotoxic proteins; Functional genomics |

| Rabbit Reticulocyte [21] | Mammalian system; Cap-independent translation | Requires additives for glycosylation; Endogenous proteins | Expression of mammalian viral proteins |

| Insect Cells [21] | Supports some glycosylation; Can produce large proteins | Non-mammalian glycosylation patterns | Production of virus-like particles (VLPs) |

| Mammalian (e.g., HeLa) [21] [23] | Native human PTMs including glycosylation; Functional protein synthesis | Lower yield than E. coli; Sensitive to additives | Production of complex human therapeutics; Functional studies [23] |

*PTMs: Post-Translational Modifications

Energy Regeneration System: Fueling the Reaction

Protein synthesis is energy-intensive. The energy system must therefore continuously supply adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to power transcription, translation, and co-translational folding [21] [24]. A typical energy mix includes:

- Nucleoside Triphosphates (NTPs): ATP and GTP are direct energy sources, while CTP and UTP are substrates for RNA synthesis [24].

- Energy Regeneration Substrates: To prevent rapid depletion, secondary substrates are included to regenerate ATP from ADP. Common systems use creatine phosphate and creatine kinase, or phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) [7] [24].

- Amino Acids: All 20 standard amino acids are required as the building blocks for the nascent polypeptide chain [21].

- Cofactors and Salts: Magnesium and potassium salts are essential for ribosomal function and enzyme activity, while other cofactors (e.g., NAD+) support metabolic pathways [22].

Nucleic Acid Template: The Genetic Blueprint

The template carries the genetic code for the protein or enzymatic pathway of interest. It can be either DNA (for coupled transcription and translation) or mRNA (for translation only) [21]. For DNA templates, which are more commonly used, specific regulatory sequences are critical for efficient expression:

- Promoter: A specific DNA sequence recognized by RNA polymerase. Bacteriophage promoters like T7, T3, and SP6 are commonly used for their high efficiency and specificity in prokaryotic systems [21] [22]. For expression using native bacterial machinery, σ70 promoters are used [22].

- Ribosome Binding Site (RBS): In prokaryotic systems, the Shine-Dalgarno sequence is essential for ribosome binding and translation initiation [21].

- Gene of Interest: The coding sequence for the target protein. For eukaryotic systems, this may require a Kozak sequence to ensure proper translation initiation [21].

- Terminator: A sequence that signals the end of transcription, ensuring the production of a discrete mRNA molecule [22].

Application in Enzyme Engineering: A Machine-Learning Guided Workflow

Cell-free systems are particularly transformative for enzyme engineering. They enable the rapid construction and testing of thousands of enzyme variants in a high-throughput manner, facilitating machine-learning (ML) guided optimization cycles [20]. The workflow below illustrates this accelerated Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle.

This integrated approach was successfully used to engineer amide synthetases. By screening 1,217 enzyme variants across 10,953 unique reactions in a cell-free system, researchers built a machine learning model that predicted optimized variants. These variants showed 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity in the synthesis of nine small-molecule pharmaceuticals, demonstrating the power of cell-free systems for rapid biocatalyst development [20].

Detailed Protocol: Cell-Free Protein Synthesis for Enzyme Production

This protocol describes a coupled transcription-translation reaction using E. coli-based cell extract for the synthesis of a target enzyme. The workflow is adaptable to a 96-well microplate format for high-throughput applications.

Materials and Reagent Setup

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Reaction | Notes/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Extract [22] | Supplies core machinery (ribosomes, tRNAs, enzymes). | Use E. coli BL21 or Rosetta2 strains for high yield. Keep on ice. |

| 10X Reaction Mix | Provides energy (ATP, GTP), NTPs, amino acids, and energy regeneration salts. | Contains creatine phosphate; aliquot to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| T7 RNA Polymerase [21] | Drives transcription from the T7 promoter on the DNA template. | Omit if using a system with endogenous RNAP or an mRNA template. |

| DNA Template | Genetic blueprint for the target enzyme. | 50-100 ng/µL of plasmid DNA or 5-10 ng/µL of linear DNA. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for the reaction. | Essential to prevent degradation of reaction components. |

| Magnesium Glutamate | Essential cofactor for ribosomal function. | Concentration is critical; often optimized for each extract batch. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Thaw Components: Thaw all reaction components (cell extract, 10X reaction mix, T7 RNA polymerase, amino acids) on ice. Gently mix each component by tapping and briefly centrifuge to collect the liquid at the bottom of the tube.

- Prepare Master Mix: In a sterile, nuclease-free microcentrifuge tube kept on ice, prepare a master mix for the number of reactions needed, plus a 10% excess to account for pipetting error.

- Table 3: Master Mix Calculation for a Single 15 µL Reaction

Component Volume per Reaction Final Concentration (Approx.) Nuclease-Free Water To 15 µL - 10X Reaction Mix 1.5 µL 1X T7 RNA Polymerase 0.5 µL As per manufacturer Cell Extract 7.5 µL 50% of reaction volume Total Master Mix Volume ~12 µL

- Table 3: Master Mix Calculation for a Single 15 µL Reaction

- Aliquot and Add Template: Pipette 12 µL of the master mix into each well or reaction tube. Add 3 µL of your DNA template (e.g., 150-300 ng of plasmid) to each reaction. For a negative control, add 3 µL of nuclease-free water.

- Incubate: Cap the tubes or seal the microplate and incubate the reaction for 4-6 hours at 30°C with shaking (if possible) or stationary. For expression from native bacterial σ70 promoters, a longer incubation (up to 15 hours) may be necessary [22].

- Stop Reaction: After incubation, place the reactions on ice. The synthesized enzyme can now be used directly in downstream functional assays or purified.

Critical Factors for Success

- Template Quality: Use high-purity DNA templates. For linear DNA, ensure clean PCR purification to avoid inhibitors.

- Additives: For difficult-to-express proteins, consider additives like chaperones (e.g., GroEL/ES) or folding enhancers. Be aware that some mammalian extracts are sensitive to additives [21].

- Post-Lysis Processing: For optimal activity with native E. coli σ70 promoters, research indicates that subjecting the crude extract to a ribosomal runoff and dialysis step post-lysis can improve transcription and increase protein yield by up to 5-fold [22].

The strategic combination of a well-chosen cellular extract, a robust energy regeneration system, and a properly designed genetic template forms the foundation of any successful cell-free reaction. As demonstrated, these systems are no longer just a tool for simple protein production; they are evolving into sophisticated platforms for accelerated enzyme engineering and the sustainable production of complex molecules. The integration of machine learning with high-throughput cell-free experimentation, as detailed in this note, is set to further revolutionize drug development and enzymatic production research, dramatically shortening the design cycles for novel biocatalysts.

Cell-free metabolic engineering (CFME) is an emerging biotechnology platform that uses in vitro ensembles of catalytic proteins prepared from purified enzymes or crude cell lysates for the production of target products, operating without the constraints of intact living cells [25]. This approach provides unprecedented freedom of design and control compared to traditional in vivo systems, enabling researchers to overcome persistent challenges in biomanufacturing, including product toxicity, low yields, and metabolic burden [25] [26]. By separating catalyst synthesis (cell growth) from catalyst utilization (metabolite production), CFME eliminates the fundamental "tug-of-war" that exists between the cell's physiological objectives and the engineer's process objectives [25].

The foundational principle of CFME recognizes that precise complex biomolecular synthesis can be conducted using purified enzyme systems or crude cell lysates, which can be accurately monitored and modeled without cellular compartmentalization [25]. This technology has evolved beyond single-enzyme applications to encompass long enzymatic pathways (>8 enzymes) with demonstrated capabilities for near-theoretical conversion yields and productivities exceeding 100 mg L⁻¹ h⁻¹ at scales surpassing 100 liters [25]. As a platform, CFME offers exciting opportunities to debug and optimize biosynthetic pathways, perform design-build-test iterations without re-engineering organisms, and implement molecular transformations when cellular toxicity or yield limitations restrict commercial feasibility [25].

Quantitative Advantages of Cell-Free Systems

The measurable benefits of cell-free systems over traditional cell-based approaches are substantial and span multiple performance metrics essential for industrial biomanufacturing. The table below summarizes key comparative advantages documented in scientific literature.

Table 1: Performance comparison between cell-based and cell-free systems

| Performance Metric | Cell-Based Systems | Cell-Free Systems | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Yield | Limited by cellular maintenance | Maximum biochemical potential | 1,3-propanediol: 0.95 mol/mol (CFME) vs 0.6 mol/mol (fermentation) [25] |

| Toxicity Constraints | Significant limitation (~2.5% v/v butanol) [25] | Greatly reduced | Enables production of toxic compounds [17] |

| Pathway Engineering | Constrained by cellular physiology [25] | Unconstrained design freedom | Direct control of all reaction components [26] |

| Volumetric Productivity | Limited by cellular growth | High (>100 mg L⁻¹ h⁻¹ demonstrated) [25] | All resources directed toward production |

| Scale-Up Factor | Challenging due to heterogeneity | ~10⁶ demonstrated for CFPS [25] | Consistent performance from microliters to 100L+ [25] |

| Complex Protein Production | Limited for toxic/membrane proteins [17] | Straightforward synthesis [17] | Direct control of reaction conditions [17] |

These quantitative advantages position cell-free systems as a transformative technology for biomanufacturing applications where cellular limitations present fundamental barriers. The separation of cell growth from production phases eliminates the metabolic burden of maintaining viability, allowing the entire biochemical machinery to be dedicated to the target pathway [25]. Furthermore, the open nature of cell-free systems facilitates continuous product removal and substrate addition, overcoming equilibrium limitations that restrict yield in closed cellular systems [25].

Application Note: Overcoming Product Toxicity

Many valuable bio-based chemicals, including fuels, pharmaceuticals, and specialty chemicals, exhibit cytotoxicity at concentrations far below commercially viable levels in traditional fermentation processes [25]. For example, bio-butanol toxicity limits fermentative production to approximately 2.5% (v/v), rendering the process economically challenging despite the chemical's attractive properties [25]. Similarly, many non-natural chemicals and complex proteins cannot be produced efficiently in living cells because they interfere with essential cellular functions or membrane integrity [17].

CFME Solution Principle

Cell-free systems overcome toxicity constraints by eliminating the requirement for cellular viability [25]. Without the complex, interconnected metabolic network of a living cell, toxic compounds cannot disrupt essential physiological processes. The CFME approach enables:

- Production of antimicrobial compounds that would kill microbial production hosts

- Synthesis of non-natural chemicals that bypass cellular metabolic regulation

- Generation of membrane-disrupting compounds that would compromise cellular integrity

- Accumulation of products to high concentrations without triggering cellular stress responses

Experimental Protocol: Toxic Metabolite Production

Table 2: Reagents and equipment for toxicity-resistant production

| Category | Specific Items | Application Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Sources | Purified enzyme cocktails, Crude cell lysates | Catalytic pathway components |

| Cofactor Regeneration | ATP, NAD(P)H, Coenzyme A | Driving thermodynamically unfavorable reactions |

| Substrates | Low-cost commodity chemicals | Starting material for biotransformation |

| Toxic Compounds | Butanol, Antimicrobial precursors | Spiking experiments to demonstrate robustness |

| Specialized Equipment | Small-scale bioreactors, Continuous feeding systems | Maintaining optimal reaction conditions |

Procedure:

Lysate Preparation (8-10 hours)

- Grow appropriate microbial strain (e.g., E. coli) to mid-log phase in rich medium

- Harvest cells by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C

- Resuspend cell pellet in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA)

- Lyse cells by homogenization or sonication on ice

- Remove cellular debris by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C

- Aliquot supernatant (lysate) and flash-freeze in liquid N₂ for storage at -80°C

Toxic Compound Production Reaction (24-72 hours)

- Prepare reaction mixture in small-scale bioreactor:

- 40% (v/v) cell lysate or purified enzyme cocktail

- Substrate(s) at target concentration (e.g., 50-100 mM)

- Energy regeneration system (10 mM ATP, 10 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 50 U/mL pyruvate kinase)

- Cofactors as required by pathway (e.g., 0.5 mM NAD⁺, 0.1 mM CoA)

- Mg²⁺ (10-20 mM) as enzyme cofactor

- Incubate with mixing (200 rpm) at optimal temperature (30-37°C)

- Maintain pH using buffering system or automated pH controller

- For continuous systems, implement substrate feeding and product removal

- Prepare reaction mixture in small-scale bioreactor:

Process Monitoring and Optimization

- Sample reaction mixture at regular intervals (every 2-4 hours)

- Quantify substrate consumption and product formation via HPLC or GC

- Monitor cofactor levels and energy charge via spectrophotometric assays

- Adjust feeding rate in continuous systems to maximize productivity

The experimental workflow below illustrates the key steps in establishing a toxicity-resistant cell-free production system:

Diagram 1: Workflow for toxicity-resistant production

Application Note: Enabling Unnatural Chemistries

Living cells possess highly regulated metabolic networks that have evolved for specific biological functions, creating significant barriers to implementing non-natural biochemical pathways or incorporating unnatural amino acids [17]. These limitations restrict access to valuable chemical space that could yield novel pharmaceuticals, materials, and specialty chemicals with enhanced properties.

CFME Solution Principle

Cell-free systems provide an open engineering environment where pathway design is limited only by enzyme availability and catalytic capability, not cellular survival requirements [26]. This freedom enables:

- Integration of non-biological catalysts alongside enzymatic steps

- Implementation of metabolic routes that would disrupt native cellular metabolism

- Incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins using expanded genetic codes [17]

- Utilization of synthetic cofactors and energy sources not found in nature

Experimental Protocol: Unnatural Pathway Implementation

Table 3: Key reagents for unnatural chemistries

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in System |

|---|---|---|

| Unnatural Building Blocks | Non-natural amino acids, Synthetic substrates | Expanding product diversity beyond natural repertoire |

| Orthogonal Cofactors | Synthetic NAD analogs, Non-biological energy sources | Driving reactions independent of natural metabolism |

| Engineered Enzymes | Designed active sites, Promiscuous catalysts | Catalyzing non-natural chemical transformations |

| Stabilizing Agents | Polyols, Osmolytes, Protease inhibitors | Maintaining enzyme activity in non-physiological conditions |

Procedure:

Pathway Design and Enzyme Selection (Variable Timeline)

- Identify target unnatural chemical structure and potential synthetic routes

- Source enzymes from biodiversity or engineer via directed evolution

- Consider cofactor requirements and compatibility with regeneration systems

- Model pathway kinetics to identify potential bottlenecks or thermodynamic barriers

Enzyme Preparation and Characterization (3-5 days)

- Express individual enzymes in suitable host systems (E. coli, yeast, etc.)

- Purify using affinity chromatography (His-tag, GST-tag, etc.)

- Determine specific activity, kinetic parameters (Kₘ, Vₘₐₓ), and stability

- Assess compatibility with other pathway enzymes in mixed assays

Unnatural Pathway Assembly (1-2 days)

- Combine purified enzymes in optimal stoichiometry based on kinetic characterization

- Include necessary cofactors and energy sources at appropriate concentrations

- Add substrate(s) at target concentration with consideration of solubility and stability

- Include stabilizing agents (e.g., 10% glycerol, 1 mg/mL BSA) if needed

- Initiate reaction by temperature shift or substrate addition

Non-Natural Amino Acid Incorporation (Specialized Application)

- Utilize cell-free protein synthesis system optimized for genetic code expansion

- Include orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair specific to unnatural amino acid

- Supplement with unnatural amino acid (0.1-2 mM concentration)

- Program synthesis with DNA template containing appropriate codon (typically amber stop codon)

- Isroduce and characterize product for accurate incorporation

The implementation of unnatural chemistries requires careful balancing of multiple system components as shown in the pathway design diagram below:

Diagram 2: Unnatural chemistry pathway design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of cell-free systems for overcoming cellular barriers requires specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components and their functions:

Table 4: Essential research reagents for cell-free systems

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Lysate Preparation Systems | E. coli extracts, Yeast extracts, Wheat germ extracts | Source of catalytic machinery and native metabolism [25] |

| Energy Regeneration | Phosphoenolpyruvate/pyruvate kinase, Creatine phosphate/creatine kinase | Maintaining ATP levels for energy-intensive reactions [25] |

| Cofactor Regeneration | NAD(P)H/format dehydrogenase, NAD(P)+/alcohol dehydrogenase | Sustaining redox balance for oxidative/reductive reactions |

| Stabilizing Agents | Polyethylene glycol, Glycerol, Dithiothreitol | Maintaining enzyme stability and activity over extended reactions |

| Unnatural Building Blocks | Non-natural amino acids, Synthetic substrates, Analog cofactors | Enabling synthesis of novel compounds beyond natural repertoire [17] |

| Monitoring Tools | HPLC standards, Spectrophotometric assay kits, Biosensors | Quantifying reaction progress and identifying bottlenecks |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Even well-designed cell-free systems may require optimization to achieve maximum performance. The following table addresses common challenges and solution strategies:

Table 5: Troubleshooting guide for cell-free systems

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Solution Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Low Product Yield | Cofactor depletion, Enzyme instability, Thermodynamic barriers | Implement cofactor regeneration; Add stabilizers; Adjust pathway thermodynamics |

| Pathway Inefficiency | Kinetic bottlenecks, Enzyme incompatibility, Substrate inhibition | Identify rate-limiting step; Enzyme engineering; Controlled substrate feeding |

| Rapid Activity Loss | Proteolysis, Cofactor degradation, Product inhibition | Add protease inhibitors; Use stable cofactor analogs; Implement product removal |

| Poor Scalability | Oxygen transfer limits, Mixing inefficiency, Gradient formation | Optimize reactor design; Improve mixing; Consider continuous systems |

Cell-free metabolic engineering represents a paradigm shift in biomanufacturing by directly addressing two fundamental limitations of cellular systems: product toxicity and constrained natural metabolism. The protocols and applications detailed in this document provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing CFME solutions to overcome these cellular barriers. As the field continues to advance, integration of CFME with emerging technologies such as synthetic biology, microfluidic control, and automated analytics will further expand the scope of accessible products and processes [17]. By liber biochemical production from the constraints of cellular survival, CFME opens new frontiers for sustainable manufacturing of valuable chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and materials.

Building and Applying CFES: From Protein Synthesis to Advanced Biomanufacturing

This application note provides detailed methodologies for the preparation of cell extracts for cell-free expression systems (CFES), a foundational step in creating versatile platforms for protein synthesis, metabolic engineering, and biosynthetic production. Cell-free biology enables transcription, translation, and complex metabolism in vitro by utilizing the molecular machinery from cells within a controlled test tube environment [7]. Freed from the constraints of cell viability and growth, these systems offer a programmable and automation-compatible platform for rapid design iteration in research and biomanufacturing [27]. The quality of the final cell extract is paramount, as it directly influences the efficiency and yield of the downstream cell-free reaction, whether for protein production [28] or more complex metabolic transformations [7]. The following protocols detail the critical stages of host cell growth, harvest, lysis, and extract preparation, with a focus on producing high-quality extracts from bacterial hosts, particularly Escherichia coli.

Host Growth and Culture Conditions

The first critical phase in creating a high-performance cell-free system is the cultivation of the host organism to generate robust, metabolically active cells with a high concentration of the translational machinery.

Culture Media and Growth Parameters

The selection of culture media and precise control of growth conditions are designed to maximize the concentration of active ribosomes and translational factors within the cells, which is a primary determinant of extract performance [28].

Key Considerations:

- Growth Rate vs. Cell Mass: Achieving a high cell mass is not the sole objective. Faster-growing cells contain more ribosomes per unit cell mass, which is crucial for efficient translation in the subsequent cell-free reaction. Therefore, protocols are optimized to promote rapid growth [28].

- Common Media: The standard enriched medium for preparing E.. coli-based extracts is 2x Yeast Extract Tryptone (2xYT) [28]. This rich medium provides the nutrients necessary to support high-density growth and the accumulation of translational components.

- Culture System: Cells are typically grown in a controlled bioreactor or flask with vigorous shaking to ensure adequate aeration and mixing.

- Harvest Point: Cells are harvested during mid- to late-exponential phase (often at an OD600 of 0.6 to 0.9) when they are metabolically most active and the translational machinery is most abundant [28].

Table 1: Standard Host Growth Parameters for E. coli Extract Preparation

| Parameter | Typical Specification | Rationale & Impact on Extract Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Culture Medium | 2x Yeast Extract Tryptone (2xYT) | A rich, complex medium that supports high-density growth and accumulation of translational machinery. |

| Growth Phase at Harvest | Mid- to late-exponential phase | Cells are metabolically active and possess a high density of ribosomes and transcription/translation factors. |

| Optical Density (OD600) | 0.6 - 0.9 | A indicator of cell density that correlates with metabolic activity; harvesting within this range ensures high-quality extracts. |

| Primary Objective | Maximize ribosome content per cell | The ribosome concentration in the extract is a key limiting factor for protein synthesis yield in the cell-free reaction. |

Detailed Protocol: Host Cell Cultivation

Materials:

- E. coli strain (e.g., BL21(DE3) or A19)

- 2xYT medium: 16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl

- Erlenmeyer flasks or a bioreactor

- Shaking incubator (or bioreactor control system)

- Sterile centrifuge bottles and tubes

Method:

- Inoculum Preparation: Inoculate a single colony of the desired E. coli strain into a small volume (e.g., 5-10 mL) of 2xYT medium. Incubate overnight at 37°C with shaking at 200-250 rpm.

- Main Culture: Dilute the overnight culture 1:100 into a larger volume of fresh, pre-warmed 2xYT medium in a flask that has a volume at least 5 times the culture volume to ensure proper aeration.

- Incubation: Incubate the culture at 37°C with vigorous shaking (200-250 rpm). Monitor the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) periodically.

- Harvest: When the culture reaches an OD600 of 0.6-0.9, promptly transfer the culture flask to an ice-water bath for 15-20 minutes to rapidly cool the cells and halt metabolism.

- Cell Pellet Formation: Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 4°C (e.g., 5,000 x g for 15 minutes). Decant and discard the supernatant.

- Washing (Optional): Wash the cell pellet by resuspending it in a cold buffer solution, such as S30 Buffer A (see Section 4.1 for formulation). Recentrifuge and discard the wash supernatant.

- Storage: The cell pellet can be processed immediately for lysis or flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for future use.

Cell Harvest and Lysis

This phase involves the controlled disruption of the harvested cell pellet to release the intracellular components while maintaining the integrity and function of the delicate transcriptional and translational machinery.

Lysis Method Comparison

The method of cell lysis must effectively break the cell wall and membrane while minimizing the denaturation of proteins, ribosomes, and enzymes. Mechanical disruption is the most common and effective approach for bacterial cells.

Table 2: Comparison of Cell Lysis Methods for Extract Preparation

| Lysis Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Suitability for CFES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Pressure Homogenization | Forcing cell suspension through a narrow valve at high pressure, creating shear forces that disrupt cell walls. | Highly efficient and scalable; reproducible; suitable for large-volume preparations. | Equipment cost; potential for local heating; requires careful pressure optimization to avoid damaging machinery. | Excellent - The widely used S30 extract protocol often employs this method [28]. |

| Bead Milling | Agitating cells with abrasive beads to physically grind and break open cell walls. | Effective for small volumes; high efficiency. | Can generate significant heat requiring active cooling; potential for co-precipitation of beads with extract. | Good - Common for lab-scale preparations. |

| Sonication | Using high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles that implode and shear cells. | Rapid; requires minimal specialized equipment beyond a sonicator. | Low scalability; high potential for protein denaturation due to heat and free radicals; process difficult to standardize. | Fair - Can be used but requires careful optimization to preserve activity. |

| Enzymatic Lysis | Using enzymes (e.g., lysozyme) to degrade the bacterial cell wall. | Gentle; no specialized equipment needed. | Can be slow and incomplete; introduction of enzymes may require subsequent removal steps; less reproducible. | Limited - Less common for high-quality CFES extracts. |

Detailed Protocol: Cell Lysis and Crude Extract Preparation

Materials:

- Cell pellet (from Section 2.2)

- S30 Buffer A: 10 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.2), 14 mM magnesium acetate, 60 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)

- High-pressure homogenizer (e.g., French Press) or bead mill

- Refrigerated centrifuge and ultracentrifuge

- DNase I (RNase-free)

Method:

- Resuspension: Thaw the cell pellet (if frozen) on ice. Resuspend the pellet thoroughly in cold S30 Buffer A (approximately 1 mL buffer per gram of wet cell paste). The final suspension should be homogeneous.

- Cell Disruption: Lyse the cells using your chosen method.

- For High-Pressure Homogenization: Pass the cell suspension through the homogenizer at a pressure of ~10,000-15,000 psi. Typically, one or two passes are sufficient for >90% lysis.

- For Bead Milling: Agitate the cell suspension with an equal volume of chilled, acid-washed glass beads (0.1 mm diameter) in a bead mill for multiple cycles (e.g., 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off on ice) until lysis is complete.