Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Inhibition Constants: Methods, Applications, and Best Practices in Drug Discovery

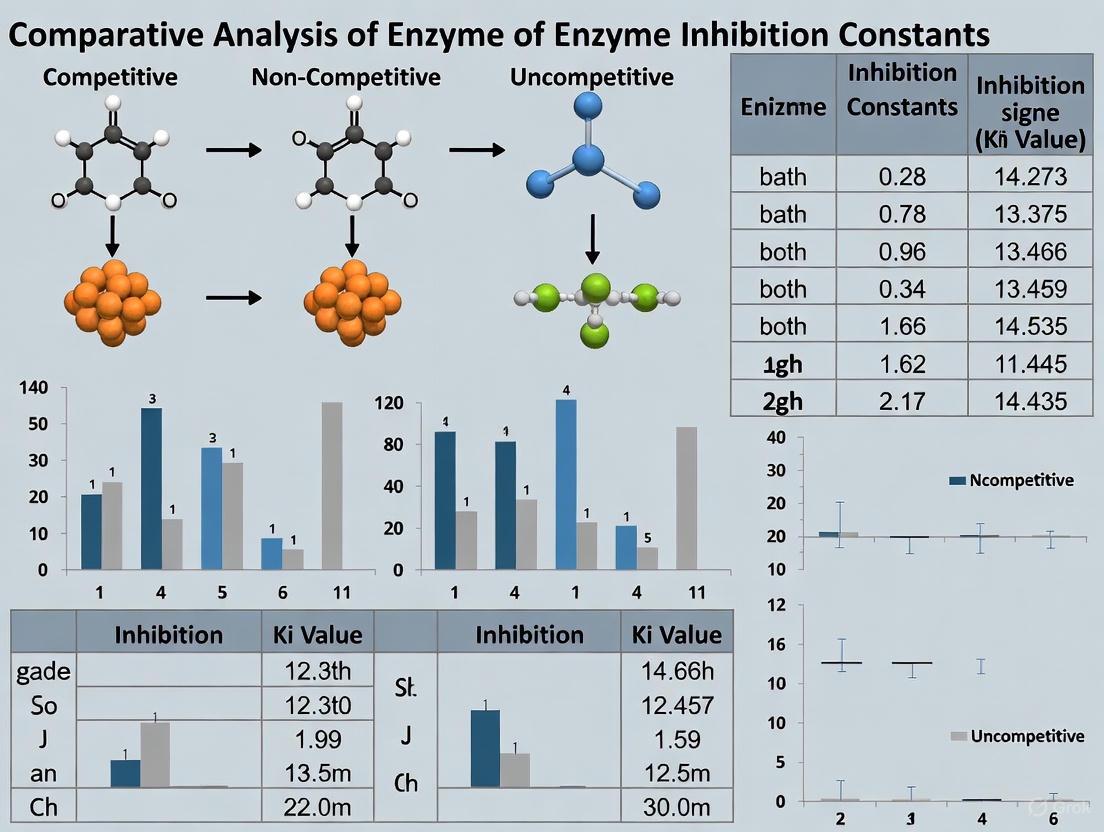

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of enzyme inhibition constants (Ki, IC50), which are critical parameters in enzymology and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Inhibition Constants: Methods, Applications, and Best Practices in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of enzyme inhibition constants (Ki, IC50), which are critical parameters in enzymology and drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of enzyme inhibition, evaluates traditional and modern methodological approaches for constant determination, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers a validated comparative framework for selecting appropriate analysis techniques. By synthesizing current research and established practices, this review serves as a strategic guide for the accurate and efficient characterization of enzyme inhibitors, ultimately facilitating more robust drug discovery pipelines.

Understanding Inhibition Constants: The Bedrock of Enzymology and Therapeutic Intervention

In the fields of enzymology, drug discovery, and pharmacology, accurately quantifying the potency of inhibitory substances is fundamental for comparing compounds, predicting in vivo behavior, and guiding the development of new therapeutics. Two parameters, the inhibition constant (Ki) and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), are cornerstone metrics used for this purpose. Although sometimes used interchangeably by those less familiar with enzyme kinetics, they represent distinct concepts with different theoretical foundations and practical implications. Ki is defined as the dissociation constant describing the binding affinity between the inhibitor and the enzyme, an intrinsic value that reflects the strength of the enzyme-inhibitor interaction independent of assay conditions. In contrast, IC50 is defined as the total concentration of inhibitor required to reduce the enzymatic activity to half of the uninhibited value in a specific assay, an operational parameter whose value is highly dependent on the experimental setup. This guide provides a comparative analysis of Ki and IC50, detailing their definitions, mathematical relationships, appropriate usage, and methodologies for estimation to support researchers in making informed decisions in their experimental design and data interpretation.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Ki: The Inhibition Constant

The inhibition constant, Ki, is a thermodynamic parameter that represents the intrinsic binding affinity of an inhibitor for its enzyme target.

- Fundamental Nature: It is an equilibrium dissociation constant. For a simple competitive inhibition scenario, the equilibrium is represented as Enzyme + Inhibitor ⇌ Enzyme-Inhibitor Complex, and Ki is defined as Ki = [E][I] / [EI], where [E] is the free enzyme concentration, [I] is the free inhibitor concentration, and [EI] is the concentration of the enzyme-inhibitor complex. A lower Ki value indicates a tighter binding interaction and greater inhibitor potency.

- Mechanistic Insight: The specific interpretation of Ki can depend on the mechanism of inhibition (e.g., competitive, uncompetitive, non-competitive, mixed). For instance, in mixed inhibition, two constants, Kic and Kiu, describe the dissociation of the inhibitor from the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex, respectively. The relative magnitude of these constants reveals the inhibition mechanism.

- Independence: As an intrinsic measure of affinity, Ki is, in theory, independent of enzyme concentration and, for a given inhibition mechanism, is also independent of substrate concentration.

IC50: The Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration

The IC50 is a functional measure of inhibitor potency derived directly from dose-response experiments.

- Fundamental Nature: It is an operational parameter indicating the total concentration of inhibitor ([I]T) required to reduce the enzymatic activity to 50% of its uninhibited value under a specific set of assay conditions. It is always measured relative to a defined system and baseline.

- Context Dependence: Unlike Ki, the IC50 value is highly dependent on the experimental conditions, including the substrate concentration, the enzyme concentration, and the incubation time. Consequently, an IC50 value is only directly comparable to other values obtained under identical conditions.

- Empirical Utility: Its key advantage is the simplicity of its determination. It does not require prior knowledge of the inhibition mechanism and can be obtained from a single dose-response curve at a fixed substrate concentration, making it a convenient first-pass metric for comparing compound potency in high-throughput screening campaigns.

Comparative Analysis: Ki vs. IC50

The following table summarizes the core differences between Ki and IC50 to facilitate a clear, objective comparison.

Table 1: Fundamental differences between Ki and IC50

| Feature | Ki (Inhibition Constant) | IC50 (Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Dissociation constant for enzyme-inhibitor binding [1] | Functional concentration for 50% activity reduction [1] |

| Fundamental Nature | Intrinsic measure of binding affinity [1] | Empirical, operational measure of potency [2] |

| Dependence on [Enzyme] | Independent (theoretically) [1] | Dependent; IC50 always larger than Ki and increases with [Enzyme] [1] |

| Dependence on [Substrate] | Independent for a given mechanism (but value signifies mechanism) [3] | Highly dependent; varies with [Substrate] and inhibition mechanism [2] [4] |

| Quantitative Relationship | Ki = IC50 / (1 + [S]/Km) for competitive inhibition (Cheng-Prusoff) [4] | IC50 = Ki (1 + [S]/Km) for competitive inhibition [2] |

| Theoretical Basis | Derived from enzyme kinetic theory and fitting to kinetic models [3] | Directly read from a dose-response curve [2] |

| Reported Value | "Free" inhibitor concentration at half-saturation [1] | "Total" inhibitor concentration for half-maximal effect [1] |

| Primary Application | Mechanistic studies, in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) [3] | Initial compound screening, functional potency ranking [2] |

The relationship IC50 = E/2 + Ki, as noted in the search results, explicitly shows the dependency of IC50 on total enzyme concentration ([E]T), explaining why IC50 is always larger than Ki. This is a critical consideration when enzyme concentrations are high, particularly for tight-binding inhibitors where Ki is less than the total enzyme concentration.

Mathematical Relationships and Conversion

The most renowned framework for connecting IC50 and Ki is the Cheng-Prusoff equation. This set of relationships allows for the estimation of the intrinsic Ki from an experimentally determined IC50, provided the assay conditions and inhibition mechanism are known.

Table 2: IC50 to Ki conversion equations for major inhibition types

| Inhibition Mechanism | Relationship (Ki =) | Key Dependence |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive | IC50 / (1 + [S]/Km) [4] [5] | Increases with higher [S] |

| Non-Competitive | IC50 [6] | Independent of [S] |

| Uncompetitive | IC50 / (1 + [S]/Km) | Decreases with higher [S] |

A large-scale retrospective analysis of 343 experiments found that under specific, optimized conditions ([S] = Km, low enzyme concentration, short incubation), the Ki for competitive inhibitors could be reliably estimated as IC50/2, with 92% of predicted values falling within a 2-fold range of the experimentally determined Ki. However, for non-competitive inhibitors, this simple relationship overestimated Ki by a factor of nearly two, consistent with the theoretical expectation that Ki = IC50 for this mechanism.

Workflow for Estimation and Conversion

The following diagram illustrates the key experimental and computational pathways for determining Ki and IC50, highlighting both traditional and modern approaches.

Figure 1. A workflow comparing experimental pathways for determining IC50, traditional Ki, and the modern 50-BOA method for Ki estimation.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Canonical Protocol for Ki Determination

The traditional method for determining Ki involves a comprehensive set of initial reaction velocity measurements across a matrix of substrate and inhibitor concentrations.

- Preliminary IC50 Estimation: First, a dose-response curve is generated by measuring enzyme activity over a range of inhibitor concentrations at a single substrate concentration, typically the Km value. This curve is fit to a logistic function to determine an approximate IC50 value [3].

- Establishing Experimental Matrix: Based on the estimated IC50, a full experimental design is established. This typically uses substrate concentrations at 0.2Km, Km, and 5Km, and inhibitor concentrations at 0, (1/3)IC50, IC50, and 3IC50 [3].

- Initial Velocity Measurements: The initial velocity (V0) of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction is measured for every combination of substrate and inhibitor concentrations in the matrix.

- Model Fitting and Constant Estimation: The collective velocity data is fitted to the appropriate inhibition model (e.g., the mixed inhibition model defined in the introduction, which is a general case) using non-linear regression analysis. The fitting procedure directly yields estimates for the kinetic constants, including Vmax, Km, and the inhibition constants Ki (and Kiu for mixed inhibition).

The IC50-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA)

Recent research has demonstrated a more efficient methodology that substantially reduces the number of required experiments while maintaining precision.

- Determine IC50: As in the canonical protocol, first determine the IC50 value using a dose-response curve at a single substrate concentration (e.g., [S] = Km) [3].

- Single Inhibitor Concentration Experiment: Instead of a full matrix, perform initial velocity measurements varying the substrate concentration, but using only a single inhibitor concentration that is greater than the determined IC50.

- Integrated Fitting: Incorporate the known relationship between IC50 and the inhibition constants (Ki and Kiu) directly into the fitting process of the kinetic model to the data. This integration dramatically improves the precision of the estimation even with the drastically reduced dataset.

- Output: This approach, termed the 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach), has been shown to reduce the number of required experiments by over 75% while ensuring accuracy and precision comparable to or better than the canonical approach [3].

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for enzyme inhibition studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Inhibition Assays |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Enzyme / Cell Lysate | The primary catalytic target whose activity is being measured and inhibited. |

| Inhibitor Compound(s) | The molecules being tested for their ability to reduce enzyme activity. |

| Enzyme-Specific Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme to product; its concentration is a key variable. |

| Detection Reagents (e.g., NADPH, Chromogenic Probes) | Enable quantification of reaction velocity by measuring product formation or substrate depletion. |

| IC50-to-Ki Converter Tools | Web servers and software that estimate Ki from IC50 using the Cheng-Prusoff equation and its derivatives, accounting for mechanism and concentrations [7]. |

Ki and IC50 are complementary yet distinct parameters, each with its own strategic value in the drug development pipeline. IC50 is an invaluable tool for the high-throughput screening of compound libraries, providing a rapid, mechanism-agnostic ranking of functional potency under standardized assay conditions. Its condition-dependence, however, limits its use for predictive biology. Ki, as an intrinsic binding constant, is the superior parameter for mechanistic studies, understanding the nature of enzyme-inhibitor interactions, and for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) in pharmacokinetic and toxicokinetic modeling, as its value is more transferable across systems.

The choice between focusing on Ki or IC50 should be guided by the research objective: use IC50 for rapid potency ranking and Ki for deep mechanistic understanding and predictive modeling. Furthermore, the adoption of modern efficient methods like the 50-BOA can significantly accelerate the drug discovery process by providing precise Ki estimates with a fraction of the experimental effort traditionally required.

Enzyme inhibition analysis is a cornerstone of drug development and metabolic research, providing critical insights for predicting drug-drug interactions and designing therapeutic agents. The classification of reversible inhibition mechanisms—competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive, and mixed—relies on distinct kinetic parameters that describe the interaction between an enzyme, its substrate, and an inhibitor. These parameters, specifically the inhibition constants, define the potency and mechanism of inhibition, guiding researchers in understanding biological regulation and developing targeted pharmaceuticals. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these mechanisms, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Inhibition Mechanisms

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, kinetic effects, and biological examples of the four primary reversible enzyme inhibition mechanisms.

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site of Inhibitor | Effect on Km | Effect on Vmax | Inhibition Constant | Biological/Clinical Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Binds to the free enzyme (E) at the active site, competing with the substrate [8] [9]. | Increases (Kmapp = Km(1+[I]/Kic)) [8] [9]. | No change [8] [10]. | Kic (slope inhibition constant) [8]. | Methotrexate binds to dihydrofolate reductase, competing with folate; used in chemotherapy [10] [9]. |

| Non-competitive | Binds to both the free enzyme (E) and the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) at an allosteric site with equal affinity [11] [12]. | No change [11] [12]. | Decreases (Vmaxapp = Vmax/(1+[I]/Ki)) [11] [13]. | Ki (Kic = Kiu) [11] [12]. | Cyanide inhibits cytochrome c oxidase; heavy metals like lead and cadmium inhibit various vital enzymes [11]. |

| Uncompetitive | Binds exclusively to the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) [3] [14]. | Decreases [3]. | Decreases [3]. | Kiu (intercept inhibition constant) [3]. | ECSI#6 inhibits the serotonin transporter (SERT) by preferentially binding to its inward-facing, potassium-bound conformation [14]. |

| Mixed | Binds to both the free enzyme (E) and the enzyme-substrate complex (ES), but with different affinities [15] [3]. | Increases or decreases [15]. | Decreases [15]. | Kic and Kiu (Kic ≠ Kiu) [15] [3]. | Often a result of active-site binding in multi-substrate reactions or tight-binding inhibitors, rather than binding to two distinct sites [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Inhibition Studies

Accurate determination of inhibition mechanisms relies on well-established kinetic experiments. The following protocol details the canonical method for characterizing inhibition.

Canonical Enzyme Inhibition Assay

This protocol is used to determine the type of inhibition and calculate the inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) by measuring initial reaction velocities under varying conditions [3].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Enzyme Solution: Prepare a stock solution of the purified enzyme in an appropriate buffer. Keep on ice to maintain stability.

- Substrate Stock Solution: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the substrate.

- Inhibitor Stock Solutions: Prepare serial dilutions of the inhibitor to achieve a range of concentrations, typically centered around the IC50 value.

- Reaction Buffer: Use a buffer that maintains optimal pH and ionic strength for the enzyme, and includes any necessary cofactors.

2. IC50 Determination (Initial Scoping):

- Measure the initial velocity of the enzyme reaction at a single substrate concentration (often near the Km) across a broad range of inhibitor concentrations [3].

- Plot the percentage of control activity (without inhibitor) versus the logarithm of inhibitor concentration ([I]).

- Fit a dose-response curve to the data to determine the IC50 value—the concentration of inhibitor that reduces enzyme activity by 50% under these specific conditions [3].

3. Comprehensive Kinetic Data Collection:

- Design an experiment that measures initial reaction rates using a matrix of substrate and inhibitor concentrations.

- Substrate Concentrations: Use a range that brackets the Km (e.g., 0.2Km, Km, and 5Km) [3].

- Inhibitor Concentrations: Use a range based on the estimated IC50 (e.g., 0, ⅓ IC50, IC50, and 3 IC50) [3].

- For each combination, initiate the reaction by adding the enzyme, allow it to proceed for a set time within the linear range, and then stop it.

- Quantify the product formed or substrate consumed using spectroscopic, chromatographic, or other suitable methods.

4. Data Analysis and Model Fitting:

- Plot the data on a Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) for each inhibitor concentration.

- The pattern of lines indicates the inhibition type: competitive lines intersect on the y-axis; non-competitive lines intersect on the x-axis; uncompetitive lines are parallel; and mixed inhibition lines intersect in the second quadrant [8] [11].

- Fit the initial velocity data directly to the general mixed inhibition equation using nonlinear regression software to obtain the most accurate estimates for Vmax, Km, Kic, and Kiu [3]: V₀ = (Vmax × [S]) / ( Km × (1 + [I]/Kic) + [S] × (1 + [I]/Kiu) )

Note on Advanced Methods: Recent studies suggest that precise estimation of inhibition constants, even for the mixed model, can be achieved with a drastically reduced dataset. The 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach) uses a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50, incorporated into the fitting process, to reliably estimate Kic and Kiu with >75% fewer experiments [3].

Visualization of Inhibition Mechanisms and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the molecular mechanisms and experimental workflows for enzyme inhibition analysis.

Mechanism of Reversible Enzyme Inhibition

Enzyme Inhibition Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for conducting enzyme inhibition experiments.

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Inhibition Studies |

|---|---|

| Purified Target Enzyme | The protein whose activity is being measured and inhibited. Purity is critical for accurate kinetic analysis. |

| Enzyme Substrate | The molecule converted to product by the enzyme. Used at varying concentrations to determine kinetic parameters. |

| Inhibitor Compounds | Molecules tested for their ability to reduce enzyme activity. Stock solutions are prepared at high concentration for serial dilution. |

| Reaction Buffer | Aqueous solution that maintains optimal pH, ionic strength, and provides necessary cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺, NADPH) for enzyme function. |

| Microplate Reader / Spectrophotometer | Instrument for high-throughput measurement of product formation or substrate consumption, often via absorbance or fluorescence. |

| Analytical Software | Non-linear regression tools (e.g., GraphPad Prism, R, MATLAB) for fitting data to kinetic models and estimating parameters like Ki and IC50 [3] [13]. |

The classification of enzyme inhibition mechanisms through kinetic analysis remains a fundamental practice in biochemical research and pharmaceutical development. Competitive inhibition is characterized by an increased apparent Km without affecting Vmax, while non-competitive inhibition reduces Vmax leaving Km unchanged. Uncompetitive inhibition, which is relatively rare, uniquely decreases both Km and Vmax. Mixed inhibition presents a more complex picture, often involving alterations to both parameters. Emerging methodologies, such as the 50-BOA, are refining the efficiency of these studies, enabling precise estimation of inhibition constants with reduced experimental burden. A clear understanding of these principles and techniques is indispensable for researchers aiming to elucidate metabolic pathways, design effective drugs, and anticipate clinical drug interactions.

In drug discovery and biochemical research, accurately quantifying a molecule's ability to inhibit an enzyme is fundamental. Two parameters stand as critical metrics for this assessment: the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and the inhibition constant (Ki). While often discussed interchangeably, they represent fundamentally different concepts. The IC50 is an experimentally derived concentration that depends heavily on specific assay conditions, whereas the Ki is an absolute thermodynamic constant representing the true binding affinity between an inhibitor and its enzyme target [16]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these two key parameters, focusing on the theoretical and practical application of the Cheng-Prusoff equation, which serves as the crucial link between empirical measurement (IC50) and fundamental biochemical property (Ki).

The central challenge in comparing inhibitor potency arises from the condition-dependent nature of IC50 values. As a direct consequence of this relationship, IC50 values obtained under different substrate concentrations cannot be directly compared, whereas Ki values, being intrinsic properties, provide a standardized basis for comparison across different experimental setups and studies [16]. This distinction is not merely academic; it has profound implications for the reliability of data interpretation in drug development pipelines.

Theoretical Foundation: Ki vs. IC50

Comparative Definitions and Properties

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of Ki and IC50, highlighting their comparative differences.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison between IC50 and Ki

| Feature | IC50 | Ki |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Concentration of inhibitor that reduces enzyme activity by 50% under a specific set of assay conditions [16] | Equilibrium dissociation constant for the enzyme-inhibitor complex; concentration at which 50% of enzyme sites are occupied in the absence of substrate [16] |

| Dependence on Substrate Concentration | Yes, significantly affected by [S] and Km [16] [10] |

No, an intrinsic property of the enzyme-inhibitor interaction [16] |

| Nature | Empirical measurement | Fundamental thermodynamic constant |

| Comparability | Can only be compared when measured under identical conditions [16] | Can be compared across different studies and experimental setups [16] |

| Primary Use | Initial, experimental readout of inhibitor potency | Gold-standard metric for reporting binding affinity and inhibitor potency |

The Cheng-Prusoff Relationship

The mathematical relationship that connects IC50 to Ki for competitive inhibition is defined by the Cheng-Prusoff equation [16] [5] [17]:

Ki = IC50 / (1 + [S]/Km)

In this equation:

Kiis the inhibition constant.IC50is the half-maximal inhibitory concentration measured experimentally.[S]is the concentration of the substrate used in the assay.Kmis the Michaelis-Menten constant of the substrate for the enzyme [16].

This equation illustrates a critical concept: the measured IC50 is always greater than the true Ki, and the difference is a function of how closely the substrate concentration [S] approaches the enzyme's Km. When [S] is much lower than Km, the IC50 approaches the Ki value. Conversely, as [S] increases, the IC50 value becomes progressively larger than the Ki [16] [10]. The equation can be rearranged to predict an IC50 from a known Ki: IC50 = Ki × (1 + [S]/Km) [17].

Figure 1: The workflow for converting the empirical IC50 value into the fundamental Ki constant using the Cheng-Prusoff equation, which requires knowledge of the assay's substrate concentration ([S]) and the enzyme's Km for the substrate.

Experimental Protocols for Determination

Accurate determination of Ki via the Cheng-Prusoff equation relies on robust experimental protocols for obtaining its components: IC50, Km, and [S].

The Canonical IC50 Determination Protocol

The traditional method for estimating inhibition constants is a multi-step process that ensures reliable data collection [3].

Preliminary IC50 Estimation:

- The % control activity of the enzyme is measured over a range of inhibitor concentrations (

[I]). - A single substrate concentration is used, typically set at or near the

Kmvalue for that substrate [3]. - A dose-response curve is fitted to the data to determine the preliminary IC50 value.

- The % control activity of the enzyme is measured over a range of inhibitor concentrations (

Establishing the Experimental Design:

- A matrix of experimental conditions is established based on the preliminary IC50.

- Substrate Concentrations (

[S]): Typically tested at 0.2Km,Km, and 5Kmto characterize the inhibition mechanism and potency across different saturation levels [3]. - Inhibitor Concentrations (

[I]): Typically tested at 0, (1/3) IC50, IC50, and 3 × IC50 to adequately define the inhibition curve [3]. - For each combination of

[S]and[I], the initial velocity (V0) of the enzyme reaction is measured.

Data Fitting and Constant Estimation:

Advanced and Rapid Methodologies

Recent methodological advances are streamlining the process of inhibition constant determination.

The 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach): A 2025 study demonstrates that precise and accurate estimation of inhibition constants is possible using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50, a significant reduction from traditional methods. This approach incorporates the relationship between IC50 and the inhibition constants directly into the fitting process, reducing the number of required experiments by over 75% while maintaining precision [3].

One-Step Capillary Electrophoresis (CE): An improved capillary electrophoresis method allows for the rapid, one-step determination of both enzyme kinetic constants (

Km,Vmax) and inhibition constants. This technique uniquely integrates reactant mixing, enzymatic reaction, and product separation within a single capillary. A key feature is "zero-volume change mixing," which allows for the analysis of the dynamic enzymatic reaction process and subsequent extraction of kinetic parameters from the product peak profile on the electropherogram [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of enzyme inhibition assays requires specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their critical functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Inhibition Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function in Inhibition Assays |

|---|---|

| Pooled Human Liver Microsomes (HLM) | A common enzyme source for studying the inhibition of human drug-metabolizing enzymes, particularly Cytochrome P450s (CYPs) [19]. |

| Recombinant Enzymes | Provide a pure system for studying inhibition against a specific enzyme target without interference from other enzymatic activities. |

| Cytochrome P450 Probe Substrates (e.g., Midazolam for CYP3A4) | Specific substrates metabolized by a single CYP enzyme, allowing for targeted inhibition studies [19]. |

| β-Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) | Essential cofactor for CYP-mediated and other oxidative metabolism; required as an electron donor in reaction mixtures [19]. |

| Inactivation Co-factors (e.g., Glutathione, GSH) | Used as trapping agents in time-dependent inhibition (TDI) assays to bind reactive intermediate metabolites and provide a more physiologically relevant assessment [19]. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) System | Used in advanced methods for integrated on-line enzymatic reaction, separation, and detection, minimizing sample consumption and analysis time [18]. |

Critical Considerations and Modern Perspectives

Limitations and Appropriate Use of the Cheng-Prusoff Equation

The Cheng-Prusoff equation is a powerful tool but has specific limitations that researchers must acknowledge.

- Valid for Reversible Inhibition: The relationship assumes a reversible, equilibrium-based interaction between the enzyme and inhibitor [16].

- Assumes No Cooperativity: The model assumes simple bimolecular interaction kinetics without cooperativity between binding sites [16] [5].

- Inhibition Mechanism Specificity: The standard equation Ki = IC50 / (1 + [S]/Km) is explicitly derived for competitive inhibition [16] [17] [10]. Different forms of the equation apply to other mechanisms:

- Power Equations for Complex Systems: In functional assays (e.g., cellular or tissue responses), agonist-receptor interactions may not follow simple kinetics. A more general power equation has been derived to account for cooperativity: KB = IC50 / (1 + (A/EC50)^K ), where K is a slope function representing overall cooperativity influences [5].

Impact of Experimental Design on Data Quality

The precision of estimated inhibition constants is highly sensitive to experimental design choices. A 2025 analysis of the "error landscape" for estimation revealed that nearly half of the data points collected in conventional experimental designs may be dispensable and can even introduce bias [3]. The study found that data obtained using low total inhibitor concentrations ([I]T) provides little information for the precise estimation of inhibition constants, especially for the Kiu parameter in mixed inhibition models. This insight directly challenges traditional protocols and underscores the superiority of modern, optimized approaches like the 50-BOA, which uses a single, well-chosen inhibitor concentration to achieve higher precision with far fewer experiments [3].

Figure 2: The logical relationship between substrate concentration [S], the measured IC50, and the true Ki. High [S] leads to a large overestimation of the inhibitor's true affinity (higher IC50), while low [S] yields an IC50 closer to the Ki, which the Cheng-Prusoff equation corrects for in both cases.

The Role of Inhibition Constants in Target Validation and Druggability Assessment

In the disciplined world of drug development, the journey from a theoretical target to a viable therapeutic candidate is paved with quantitative rigor. At the heart of this process lies the critical evaluation of enzyme inhibitors, where the inhibition constant (Ki) serves as a fundamental metric for assessing both the potency of a drug candidate and the druggability of its intended target. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the key experimental methodologies used to determine these essential parameters, offering researchers a framework for robust target validation.

Fundamental Concepts of Enzyme Inhibition

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions can be suppressed by an inhibitor (I) that binds to either the free enzyme (E) or the enzyme-substrate complex (C), forming reversible complexes with dissociation constants of Kic or Kiu, respectively [3]. These inhibition constants characterize not only the potency of the inhibition—with lower constants indicating higher binding affinity—but also the mechanism of action.

The relative magnitude of these two constants determines the inhibition type: competitive (Kic << Kiu), uncompetitive (Kiu << Kic), or mixed (Kic ≈ Kiu) [3]. The initial velocity of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction (V₀) is described by a general equation that can describe all these inhibition types [3]: $$V₀ = \frac{V{max} ST}{KM (1 + \frac{IT}{K{ic}}) + ST (1 + \frac{IT}{K{iu}})}$$

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies for Determining Inhibition Constants

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of major methodological approaches for inhibitor characterization.

| Method | Key Principle | Data Output | Throughput | Key Applications | Major Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Multi-Concentration Analysis [3] | Fitting velocity data from multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations to kinetic models. | Ki, Vmax, KM | Low | Basic enzyme characterization; mechanistic studies. | Well-established; provides comprehensive kinetic parameters. | High reagent consumption; time-intensive; can introduce bias. |

| 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach) [3] | Uses relationship between IC50 and Ki with a single inhibitor concentration >IC50 for fitting. | Kic, Kiu | High (>75% reduction in experiments) | Efficient drug screening; target validation. | Dramatically reduces experimental load; maintains precision/accuracy. | Requires initial IC50 determination. |

| Dixon Plot [20] | Plots reciprocal velocity (1/v) against inhibitor concentration [I] at different substrate levels. | Ki (from intersection point) | Medium | Visual determination of Ki and inhibition mechanism. | Simple graphical method; clear visualization of inhibition type. | Less precise than comprehensive fitting; interpretation sensitive. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis (One-Step) [18] | Monitors substrate depletion/product formation as zones migrate and interact within a capillary. | Ki, KM | High | Rapid screening of inhibitors; enzyme kinetics with minimal sample. | Very low reagent consumption; automated and rapid. | Specialized equipment required; method development can be complex. |

| Kitz & Wilson (Continuous Progress Curves) [21] | Fits progress curves of product formation in the presence of inhibitor to a decay model. | KI, kinact | Medium | Characterization of irreversible covalent inhibitors. | Directly measures time-dependent inhibition; provides kinetic constants. | Requires continuous assay; complex fitting; prone to error with substrate depletion [22]. |

| Time-Dependent IC50 (Reversible Covalent) [22] | Models shift in IC50 values with varying pre-incubation or incubation times. | Ki, k₅, k₆ | Medium | Evaluating reversible covalent inhibitors with time-dependent effects. | Deconvolutes binding and covalent modification kinetics. | Complex modeling; requires multiple time-point experiments. |

Classical Multi-Concentration Analysis

- Experimental Workflow:

- IC50 Determination: Initially estimate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) using a range of inhibitor concentrations at a single substrate concentration (typically at KM) [3].

- Experimental Design: Establish a matrix of substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.2KM, KM, and 5KM) and inhibitor concentrations (e.g., 0, ⅓IC50, IC50, and 3IC50) [3].

- Data Collection: Measure the initial velocity (V₀) of the enzymatic reaction for each concentration combination.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit the collected velocity data to the appropriate inhibition model (e.g., the general equation for mixed inhibition) using non-linear regression to estimate the inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) [3].

50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach)

- Experimental Workflow:

- IC50 Determination: As in the classical method, first determine the IC50 value of the inhibitor [3].

- Optimized Experimental Design: For a single substrate concentration (e.g., at KM), use only a single inhibitor concentration that is greater than the determined IC50 value. Research indicates this single point can suffice for precise estimation [3].

- Data Collection & Fitting: Measure the initial velocity at this condition. Crucially, incorporate the established harmonic mean relationship between the IC50 and the inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) directly into the fitting process to estimate their values [3].

Characterization of Time-Dependent Covalent Inhibitors

- Experimental Workflow for Reversible Covalent Inhibitors [22]:

- Time-Dependent IC50 Assay: Perform a series of IC50 determinations where the pre-incubation time (enzyme with inhibitor) or the incubation time (enzyme, inhibitor, and substrate) is systematically varied.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting time-dependent IC50 data using specialized methods, such as an implicit equation or numerical modelling (e.g., EPIC-CoRe), to derive the initial non-covalent inhibition constant (Ki), the covalent modification rate constants (k₅ and k₆), and the overall inhibition constant (K_i^{app}) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below outlines key reagents and materials essential for conducting robust enzyme inhibition assays.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Inhibition Assays | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Target | The biological macromolecule whose function is being inhibited. | Alkaline Phosphatase, α-Glucosidase, Xanthine Oxidase [18] [23] | Purity, stability, and source (recombinant vs. native) are critical for reproducible kinetics. |

| Chemical Inhibitors | Compounds screened or characterized for inhibitory activity. | Saxagliptin (reversible covalent DPPIV inhibitor) [22] | Solubility (may require DMSO stocks), stability in assay buffer, and potential for non-specific binding. |

| Enzyme Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme to a detectable product. | p-Nitrophenyl-disodium phosphate for Alkaline Phosphatase [18] | Must be specific to the enzyme; product should be distinguishable from substrate for detection. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | Instrumentation for separation-based kinetic analysis [18]. | One-step determination of Ki and KM [18] | Enables minimal reagent use and automated, rapid analysis. |

| Detection Reagents/Sensors | Enable quantification of reaction progress. | Absorbance/fluorescence probes, LC-MS detectors [21] | Compatibility with enzyme activity, sensitivity, and dynamic range must be validated. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for selecting and applying the key methodologies discussed in this guide.

Discussion and Strategic Application

The choice of methodology is not merely a technical decision but a strategic one that directly impacts the reliability and efficiency of target validation. The emerging 50-BOA method challenges the canonical requirement for extensive data collection, demonstrating that precise and accurate estimation of inhibition constants is possible with a single, well-chosen inhibitor concentration, thereby streamlining early-stage screening [3].

For covalent inhibitors, the kinetic characterization must be more nuanced. Methods that deconvolute the initial binding affinity (KI) from the rate of covalent modification (kinact for irreversible; k₅/k₆ for reversible) are essential for a true structure-activity relationship, guiding the optimization of warhead reactivity and binding scaffold selectivity [22] [21].

Ultimately, a well-determined inhibition constant (Ki) provides a foundational metric for druggability assessment. A potent Ki suggests strong target engagement potential, while the mechanism of inhibition informs on the likely pharmacological profile and potential clinical management strategies [3] [24]. Integrating these precise kinetic parameters into broader pharmacological and toxicological profiles enables researchers to make data-driven decisions on which targets and inhibitor chemotypes to advance through the costly drug development pipeline.

Methodologies for Determining Ki: From Classical Analyses to Cutting-Edge Approaches

The accurate determination of enzyme kinetics and inhibition constants is a cornerstone of biochemical research and pharmaceutical development. Classical linearization methods provide accessible graphical approaches to estimate key parameters such as the Michaelis constant (Kₘ), maximum velocity (Vₘₐₓ), and inhibition constant (Kᵢ). Among these, the Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee, and Dixon plots have been widely utilized for decades to transform the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation into linear forms, enabling researchers to extract kinetic parameters through linear regression [25] [26].

Despite their historical significance and continued use in educational settings, these linear transformation methods exhibit significant limitations in accuracy and precision compared to modern nonlinear regression techniques [27] [25]. This comparative analysis examines the underlying principles, applications, and methodological constraints of these three classical linearization approaches, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate analytical methods based on their experimental requirements and precision needs.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Formulations

The Michaelis-Menten Equation

Enzyme-catalyzed reactions follow a hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration ([S]) and initial reaction velocity (V₀), described by the Michaelis-Menten equation:

[ V0 = \frac{V{max} [S]}{K_m + [S]} ]

where Vₘₐₓ represents the maximum reaction velocity attained at infinite substrate concentration, and Kₘ is the Michaelis constant, defined as the substrate concentration at half Vₘₐₓ [28]. The Kₘ value provides insight into the enzyme's affinity for its substrate, with lower values indicating higher affinity [28].

Principles of Linear Transformation

Linear transformation methods convert this hyperbolic relationship into a linear form by applying algebraic manipulations, allowing kinetic parameters to be determined from the slopes and intercepts of straight-line plots [26]. This approach gained historical significance due to the simplicity of linear regression calculations before the widespread availability of computers capable of performing nonlinear regression [25].

Methodological Comparison of Linearization Approaches

Lineweaver-Burk Plot

The Lineweaver-Burk plot, also known as the double-reciprocal plot, transforms the Michaelis-Menten equation by taking reciprocals of both sides [25]:

[ \frac{1}{V0} = \frac{Km}{V{max}} \cdot \frac{1}{[S]} + \frac{1}{V{max}} ]

This creates a linear relationship where 1/V₀ is plotted against 1/[S], yielding a straight line with slope of Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ, y-intercept of 1/Vₘₐₓ, and x-intercept of -1/Kₘ [25] [26].

Applications and Limitations: The Lineweaver-Burk plot is particularly useful for distinguishing different types of enzyme inhibition. Competitive inhibitors increase the apparent Kₘ without affecting Vₘₐₓ, resulting in plots with different slopes that intersect on the y-axis. Uncompetitive inhibitors decrease both Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ, producing parallel lines. Non-competitive and mixed inhibitors affect both parameters, causing intersections typically in the second quadrant [25] [29].

The primary limitation of this method stems from the reciprocal transformation, which disproportionately compresses data points at high substrate concentrations while expanding those at low concentrations where measurement errors are typically larger [25]. This distortion amplifies experimental errors and can yield biased parameter estimates, making it the least accurate among linearization methods [27] [25] [26].

Eadie-Hofstee Plot

The Eadie-Hofstee plot employs an alternative linearization of the Michaelis-Menten equation:

[ V0 = V{max} - Km \cdot \frac{V0}{[S]} ]

In this approach, V₀ is plotted against V₀/[S], generating a straight line with slope of -Kₘ, y-intercept of Vₘₐₓ, and x-intercept of Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ [26].

Applications and Limitations: The Eadie-Hofstee plot offers a significant advantage over the Lineweaver-Burk method by avoiding reciprocal transformation of the measured reaction velocities, giving equal weight to all data points [26]. This provides a more reliable estimate of kinetic parameters, particularly Vₘₐₓ [26]. The plot directly displays both fundamental kinetic parameters: Vₘₐₓ (krelease) as the y-intercept and Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ (kcapture) as the x-intercept [26].

A potential limitation is that both axes contain V₀, so any experimental error in measuring velocity will affect both coordinates [26]. Nevertheless, the Eadie-Hofstee plot is generally recommended over Lineweaver-Burk for determining kinetic parameters from experimental data [26].

Dixon Plot

The Dixon plot specializes in analyzing enzyme inhibition kinetics, plotting 1/V₀ against inhibitor concentration [I] at varying substrate concentrations [30]:

[ \frac{1}{V0} = \frac{Km}{V{max}[S]}(1 + \frac{[I]}{Ki}) + \frac{1}{V_{max}} ]

The intersection point of lines obtained at different substrate concentrations provides an estimate of the inhibition constant Kᵢ, with the lines crossing at [I] = -Kᵢ [30].

Applications and Limitations: This method is particularly valuable for distinguishing between competitive, non-competitive, and uncompetitive inhibition mechanisms and determining inhibitor potency [30] [29]. It provides a visual assessment of inhibitor strength and is foundational for pharmacological assays in drug discovery [30].

The Dixon plot shares similar limitations with other reciprocal plots regarding error distortion. Additionally, accurate determination requires testing multiple substrate concentrations to generate the intersecting lines necessary for Kᵢ estimation [30].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Classical Linearization Methods

| Feature | Lineweaver-Burk | Eadie-Hofstee | Dixon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables Plotted | 1/V₀ vs 1/[S] | V₀ vs V₀/[S] | 1/V₀ vs [I] |

| Y-Intercept | 1/Vₘₐₓ | Vₘₐₓ | Complex function of parameters |

| Slope | Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ | -Kₘ | Varies with inhibition type |

| X-Intercept | -1/Kₘ | Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ | Varies with inhibition type |

| Primary Application | Determining Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ | Determining Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ | Determining Kᵢ |

| Error Distribution | Unequal weighting, amplifies errors | Equal weighting of V₀ measurements | Unequal weighting, amplifies errors |

| Recommended Use | Educational demonstration, inhibition typing | Parameter estimation from experimental data | Inhibition constant determination |

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

General Experimental Workflow for Enzyme Kinetics

Detailed Protocol for Michaelis-Menten Parameter Determination

Enzyme Preparation: Prepare purified enzyme solution with standardized activity units. Maintain constant enzyme concentration across all assays while varying substrate concentrations [26].

Substrate Dilution Series: Create minimum of 6-8 substrate concentrations spanning a range from below to above the expected Kₘ value (typically 0.2Kₘ to 5Kₘ) [26]. Ideally, include 3-4 concentrations below Kₘ and 3-4 above Kₘ for optimal parameter estimation [26].

Initial Velocity Measurement: For each substrate concentration, measure the initial rate of product formation (V₀) by monitoring the linear phase of the reaction. Ensure less than 10% substrate depletion during the measurement period to maintain steady-state conditions [31] [26].

Data Transformation and Plotting:

- Lineweaver-Burk: Calculate 1/V₀ and 1/[S] for each data point [25] [26].

- Eadie-Hofstee: Calculate V₀/[S] for each data point [26].

- Direct Linear Plot: Plot each [S] on the negative x-axis and corresponding V₀ on the y-axis, drawing lines between them; the intersection point estimates (Kₘ, Vₘₐₓ) [26].

Parameter Estimation: Perform linear regression on transformed data. For Lineweaver-Burk: Vₘₐₓ = 1/y-intercept, Kₘ = slope/y-intercept. For Eadie-Hofstee: Vₘₐₓ = y-intercept, Kₘ = -slope [26].

Protocol for Inhibition Constant Determination Using Dixon Plot

Experimental Design: Select 3-4 substrate concentrations (typically 0.5Kₘ, 1Kₘ, and 2Kₘ) and 5-6 inhibitor concentrations including 0 (uninhibited control) [30].

Velocity Measurements: Measure initial reaction velocities (V₀) for all combinations of substrate and inhibitor concentrations [30].

Data Transformation: Calculate 1/V₀ for each measurement [30].

Plot Generation: Create Dixon plot with [I] on x-axis and 1/V₀ on y-axis. Plot separate lines for each substrate concentration [30].

Kᵢ Determination: Identify the intersection point of the lines. The x-coordinate of this intersection provides -Kᵢ [30].

Inhibition Mechanism Identification: Competitive inhibition produces lines intersecting above the x-axis; non-competitive inhibition shows intersection on the x-axis; uncompetitive inhibition results in parallel lines [29].

Performance Assessment: Accuracy and Precision Analysis

Comparative Statistical Performance

A comprehensive simulation study comparing various estimation methods for Michaelis-Menten parameters revealed significant differences in accuracy and precision between linearization approaches [27]. The study employed Monte-Carlo simulation with 1,000 replicates of substrate concentration-time data, incorporating both additive and combined error models to assess methodological robustness [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation Methods

| Estimation Method | Relative Accuracy | Relative Precision | Error Model Sensitivity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Regression | Highest | Highest | Low | Gold standard; direct fitting without data transformation |

| Eadie-Hofstee | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Recommended linear method for parameter estimation |

| Lineweaver-Burk | Lowest | Lowest | High | Severe error distortion; educational use only |

| Dixon Plot | Variable | Variable | High | Specialized for inhibition studies; requires multiple [S] |

The simulation results demonstrated that nonlinear regression methods provided the most accurate and precise parameter estimates, with superiority becoming more pronounced when data incorporated combined error models [27]. Among linearization methods, the Eadie-Hofstee approach generally outperformed the Lineweaver-Burk method due to its more balanced error distribution [27] [26].

Error Propagation and Methodological Limitations

All linear transformation methods distort experimental error structures, but to varying degrees [25] [26]. The Lineweaver-Burk plot is particularly problematic because it applies reciprocal transformation to both variables, dramatically amplifying errors at low substrate concentrations where measurements are typically least accurate [25]. For example, if V = 1±0.1, then 1/V = 1±0.1 (10% error), but if V = 10±0.1, then 1/V = 0.1±0.001 (1% error) [25]. This unequal error weighting biases parameter estimates and reduces reliability [25].

The Eadie-Hofstee plot partially mitigates this issue by avoiding reciprocal transformation of the measured velocity values, though it still incorporates V₀ in both coordinates, resulting in correlated errors [26]. All linearization methods assume that true initial velocities are measured, and deviations from this assumption – such as progressive enzyme inactivation during assay – can produce misleading linear plots with erroneous kinetic parameters [31].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Functional Role | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | High specific activity, known concentration | Biological catalyst | Stability, purity >95%, absence of contaminants |

| Substrate | High purity, solubility in buffer | Reactant molecule | Purity >99%, stability under assay conditions |

| Inhibitor Compounds | Known molecular weight, solubility | Inhibition studies | Purity >98%, stock solution stability |

| Buffer Components | Appropriate pKₐ, non-interfering | pH maintenance | Temperature consistency, ionic strength effects |

| Cofactors | As required by specific enzyme | Catalytic assistance | Stability, appropriate concentration |

| Detection Reagents | Spectrophotometric, fluorometric | Product quantification | Sensitivity, linear range, minimal background |

| Reference Standards | Authentic product compounds | Calibration | Certified purity, solution stability |

Classical linearization methods have played a significant historical role in enzyme kinetics, providing accessible approaches for estimating kinetic parameters through graphical analysis. Among these methods, the Eadie-Hofstee plot generally offers superior performance for determining Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ due to its more balanced error weighting, while Dixon plots remain valuable for initial inhibition studies and Kᵢ estimation [26] [30].

However, contemporary research demands higher standards of accuracy and precision than these classical methods typically provide. Modern nonlinear regression techniques, implemented in software packages such as GraphPad Prism, MATLAB, and specialized tools like DynaFit and NONMEM, offer significantly improved parameter estimation by directly fitting the untransformed data to the Michaelis-Menten equation without distorting error structures [27] [25] [26]. These approaches have become the gold standard in rigorous enzyme kinetics research [27].

For researchers conducting inhibition studies, emerging methodologies like the 50-BOA (IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach) demonstrate that precise estimation of inhibition constants is possible with dramatically reduced experimental requirements – potentially using just a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC₅₀ value [32]. This represents a promising direction for increasing efficiency in enzyme inhibition analysis while maintaining accuracy.

While classical linearization methods retain value for educational purposes and initial data exploration, researchers engaged in drug development and precise biochemical characterization should prioritize nonlinear regression approaches for definitive parameter estimation, reserving linear transformations for preliminary analysis and visualization purposes.

In the field of enzyme kinetics, accurately determining inhibition constants (Ki) is crucial for understanding drug-drug interactions and chemical bioaccumulation. Researchers commonly employ various analytical methods to estimate these parameters from experimental data. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three predominant methods for analyzing enzyme inhibition data: Simultaneous Nonlinear Regression (SNLR), the KM,app method, and the Dixon linearization approach. Evaluation of quantitative performance data reveals that SNLR demonstrates superior robustness, accuracy, and efficiency, establishing it as the preferred methodology for reliable Ki determination in both pharmacological and environmental research contexts.

Enzyme inhibition occurs when a molecule (inhibitor) interferes with an enzyme's activity, reducing the rate of a metabolic reaction. This phenomenon is fundamental to drug action, toxicology, and cellular regulation. Competitive inhibition, a common mechanism, arises when an inhibitor competes with the substrate for binding to the enzyme's active site. The reaction scheme can be represented as a reversible equilibrium where the enzyme (E) binds either the substrate (S) to form a complex (ES) that yields product (P), or the inhibitor (I) to form an inactive complex (EI) [33].

The fundamental equation describing competitive inhibition is:

v = Vmax * [S] / [KM * (1 + [I]/Ki) + [S]]

Where:

- v is the initial reaction velocity

- Vmax is the maximum reaction velocity

- [S] is the substrate concentration

- KM is the Michaelis-Menten constant (substrate concentration at half Vmax)

- [I] is the inhibitor concentration

- Ki is the inhibition constant (dissociation constant for the enzyme-inhibitor complex)

The Ki value quantitatively represents the inhibitor's potency; a lower Ki indicates stronger binding and more effective inhibition. Accurate determination of Ki is therefore critical for predicting metabolic interactions, such as those occurring when multiple drugs are administered concurrently [33] [34].

Methodologies for Determining Inhibition Constants

Simultaneous Nonlinear Regression (SNLR)

Experimental Protocol: SNLR requires initial velocity measurements at multiple substrate concentrations across a range of inhibitor concentrations, including a control with no inhibitor. The entire dataset is fitted simultaneously to the competitive inhibition equation using nonlinear regression algorithms. This method directly estimates all parameters (Vmax, KM, and Ki) by minimizing the sum of squared residuals between observed and predicted reaction velocities [35].

KM,app Method

Experimental Protocol: This two-step approach first involves separately fitting the Michaelis-Menten equation to velocity data at each inhibitor concentration, obtaining an apparent KM (KM,app) for each. In the second step, these KM,app values are plotted against the corresponding inhibitor concentrations. The Ki is then determined from the x-intercept of this linear plot, where KM,app = -Ki [35].

Dixon Plot (Linearization)

Experimental Protocol: The Dixon method uses a linear transformation of the Michaelis-Menten equation. Researchers measure reaction rates at one or two substrate concentrations across varying inhibitor levels. They then plot the reciprocal of velocity (1/v) against inhibitor concentration ([I]). For competitive inhibition, these lines intersect at a point where [I] = -Ki, providing an estimate of the inhibition constant [35].

Comparative Performance Analysis

A comprehensive simulation study directly compared the performance of these three methods for estimating Ki values across a wide range of KM/Ki ratios (from <0.1 to >600). The results demonstrate clear differences in method performance [35].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Ki Estimation Methods

| Method | Parameter Recovery | Computational Efficiency | Implementation Complexity | Robustness to Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNLR | Excellent (Accurate KM, VMAX, and Ki) | Highest | Fastest and easiest | Most robust |

| KM,app Method | Good Ki estimates | Moderate | More time-consuming | Moderately robust |

| Dixon Plot | Inaccurate and widely ranging Ki | N/A | Simple but unreliable | Least robust |

The superiority of SNLR is particularly evident in its handling of experimental error. When metabolic formation rates were simulated with random error (10% coefficient of variation), SNLR provided significantly more accurate and precise Ki estimates compared to the other methods. The Dixon method, despite its historical popularity and simplicity, produced "widely ranging and inaccurate estimates of Ki" according to the controlled simulations [35].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Enzyme Inhibition Studies

Sample Preparation and Characterization

Liver S9 Fraction Protocol:

- Tissue Homogenization: Clear liver tissue of blood and homogenize in 2-4 volumes of ice-cold buffer (e.g., 150 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA, 250 mM sucrose, pH 7.8) using a Potter-Elvehjem mortar and pestle with 4-5 strokes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the homogenate at 13,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C.

- Aliquoting and Storage: Collect the supernatant (S9 fraction), aliquot into small volumes (e.g., 0.5 mL), flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen, and store at -80°C until use [33].

Enzyme Activity Characterization:

- CYP450 Activity: Measure via ethoxyresorufin O-dealkylation (EROD) assay.

- GST Activity: Assess by monitoring glutathione conjugation of 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB).

- UGT Activity: Determine using p-nitrophenol (p-NP) glucuronidation assays.

- Perform all assays in quadruplicate at physiologically relevant temperature and pH [33].

Data Collection for SNLR Analysis

Substrate Depletion Approach:

- Incubation Conditions: Use environmentally/pharmacologically relevant substrate and inhibitor concentrations. For PAH studies, examples include phenanthrene, pyrene, and benzo[a]pyrene as binary mixtures.

- Time Course Measurements: Monitor substrate depletion over time to determine initial rates.

- Replicate Design: Include adequate replication (minimum n=3-4) for statistical power.

- Control Experiments: Always include control incubations without inhibitor and without enzyme to account for non-enzymatic degradation [33].

Optimal Experimental Design: Recent research suggests that informative data for precise Ki estimation can be obtained using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50 value, substantially reducing experimental requirements while maintaining accuracy. This model-informed approach allows for a more than 75% reduction in required data points while achieving equal or improved precision compared to conventional designs [34].

SNLR Data Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Example Use in Inhibition Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Liver S9 Fractions | Source of metabolic enzymes | Provide complete phase I and II enzyme systems for substrate depletion studies [33] |

| β-NADPH | Cofactor for CYP450 enzymes | Essential for cytochrome P450-mediated reactions; required in incubation mixtures [33] |

| Substrate Compounds | Molecules whose metabolism is studied | PAHs (phenanthrene, pyrene, benzo[a]pyrene) or specific drug substrates [33] |

| Inhibitor Compounds | Molecules that reduce enzyme activity | Test compounds for inhibition potential; included at varying concentrations [33] |

| UDPGA | Cofactor for UGT enzymes | Required for glucuronidation reactions in phase II metabolism [33] |

| Reduced Glutathione (GSH) | Cofactor for GST enzymes | Essential for glutathione conjugation reactions [33] |

| Alamethicin | Pore-forming peptide | Activates UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activity in membrane preparations [33] |

| Model Substrates | Probe compounds for specific enzymes | 7-ethoxyresorufin (CYP1A), CDNB (GST), p-nitrophenol (UGT) [33] |

Methodological Comparison Visualization

The comparative analysis of methods for determining enzyme inhibition constants demonstrates the clear superiority of Simultaneous Nonlinear Regression (SNLR). This approach outperforms both the KM,app method and traditional Dixon linearization in accuracy, precision, and efficiency. SNLR's robustness to experimental error and its ability to provide reliable parameter estimates with realistic confidence intervals make it particularly valuable for modern pharmacological research and environmental risk assessment.

For researchers designing enzyme inhibition studies, implementing SNLR with optimal experimental designs—potentially incorporating model-informed approaches that reduce data requirements—represents the current gold standard for generating reliable, reproducible Ki values that accurately reflect inhibitor potency and inform critical decisions in drug development and chemical safety assessment.

Enzyme inhibition analysis is a cornerstone of drug development, essential for predicting drug-drug interactions and evaluating inhibitor potency as recommended by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [32] [3]. Traditionally, estimating inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) has required extensive experimental data involving multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations—an approach utilized in over 68,000 studies since its introduction in 1930 [32]. However, inconsistencies across studies highlight the need for more systematic experimental designs, particularly when prior knowledge of inhibition type is unavailable [3].

This comparison guide examines a groundbreaking methodological framework—the IC50-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA)—that challenges conventional paradigms by enabling precise estimation of inhibition constants using a single inhibitor concentration. We objectively evaluate its performance against traditional methods, supported by experimental data and implementation protocols.

Understanding Enzyme Inhibition Constants

Fundamental Concepts and Significance

Enzyme inhibition occurs when a substance (inhibitor) reversibly binds to an enzyme (competitive), enzyme-substrate complex (uncompetitive), or both (mixed) [3]. The key parameters characterizing these interactions are the inhibition constants:

- Kic: Dissociation constant between inhibitor and free enzyme

- Kiu: Dissociation constant between inhibitor and enzyme-substrate complex

These constants represent both inhibitor potency and mechanism, with lower values indicating higher binding affinity [32] [3]. Their accurate estimation is crucial for predicting in vivo enzyme inhibition through mathematical models derived from in vitro experiments [32].

The Traditional Approach to Estimation

The canonical method for estimating inhibition constants follows a well-established protocol [32] [3]:

- IC50 Determination: Estimate half-maximal inhibitory concentration using various inhibitor concentrations with a single substrate concentration (typically KM)

- Experimental Design: Establish conditions with ST at 0.2KM, KM, and 5KM and IT at 0, 1/3 IC50, IC50, and 3IC50

- Velocity Measurement: Measure initial reaction velocity for each concentration combination

- Model Fitting: Fit the mixed inhibition model to the data to estimate constants

This approach generates 12 data points and relies on the general equation for mixed inhibition [32]:

The 50-BOA Method: A Paradigm Shift

Theoretical Foundation and Innovation

The 50-BOA method emerged from analyzing error landscapes of estimations across various experimental designs [32] [3]. Researchers discovered that nearly half of conventional data is dispensable and potentially bias-inducing [3]. The key insight was that precise estimation becomes possible when using a single inhibitor concentration greater than IC50 while incorporating the harmonic mean relationship between IC50 and inhibition constants into the fitting process [32].

The method specifically addresses the challenge of estimating two inhibition constants for mixed inhibition without prior knowledge of inhibition type—a significant limitation of previous single-concentration methods [32] [3].

Experimental Design and Workflow

The 50-BOA workflow represents a substantial simplification compared to traditional approaches:

Computational Implementation

The researchers provide user-friendly MATLAB and R packages that automate the estimation process [36]. The core implementation involves:

- Data Formatting: Organizing initial velocity data in a defined Excel format with Vmax, KM, IC50, and experimental setups

- Condition Checking: The 'BOA_Condition' function verifies data sufficiency (presence of IT ≥ IC50 and distinct ST values within 0.2KM to 5KM)

- Cross-Validation: The 'CV_Inhibition' function selects appropriate regularization constants

- Error Landscape Analysis: The main function estimates inhibition constants with confidence intervals and generates diagnostic heatmaps [36]

The package also extends to specialized systems including bi-substrate mechanisms, substrate cooperativity, and inhibitor cooperativity [36].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Requirements and Efficiency

The 50-BOA method demonstrates remarkable efficiency improvements over traditional approaches:

Table 1: Method Efficiency Comparison

| Parameter | Traditional Method | 50-BOA Method | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of inhibitor concentrations required | 4 | 1 | 75% reduction |

| Minimum total data points | 12 | 3 | 75% reduction |

| Prior knowledge of inhibition type | Required | Not required | More versatile |

| Experimental time and resources | High | Minimal | Substantial savings |

| Applicability to mixed inhibition | Limited | Excellent | Broader application |

Precision and Accuracy in Experimental Applications

The method has been validated through multiple experimental applications:

Table 2: Experimental Validation Data

| Enzyme-Inhibitor Pair | Method | Kic (μM) | Kiu (μM) | Confidence Interval | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triazolam-Ketoconazole (CYP3A4) | Traditional | Varied reported values | Inconsistent across studies | [32] | |

| Triazolam-Ketoconazole (CYP3A4) | 50-BOA | Precise estimation | Narrow CI | [3] | |

| Chlorzoxazone-Ethambutol | Traditional | 0.0367 | 0.0766 | Extremely wide (0.0244-1.59×10^12) | [36] |

| Chlorzoxazone-Ethambutol | 50-BOA | 0.0398 | 0.0403 | Narrow (0.0358-0.0460, 0.0337-0.0482) | [36] |

The 50-BOA method consistently produces narrower confidence intervals, indicating superior precision. In test cases, the traditional method generated implausibly wide confidence intervals (e.g., 0.0244-1.59×10^12 for Kic), while 50-BOA provided biologically meaningful ranges [36].

Error Landscape Analysis

The theoretical foundation of 50-BOA involves analyzing error landscapes to identify optimal experimental designs [32] [3]. Key findings include:

- Low IT Limitations: When IT is much lower than Kic and Kiu, the error landscape shows broadly distributed dark regions, indicating poor identifiability of inhibition constants

- Optimal Conditions: Precise estimation requires IT > IC50, which creates well-defined minima in the error landscape

- Regularization Benefits: Incorporating the IC50-inhibition constant relationship acts as effective regularization, constraining the parameter space and improving identifiability [32]

Practical Implementation Guide

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for 50-BOA Implementation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Role | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 50-BOA Software Package | Computational implementation of the method | Available for MATLAB and R; includes auxiliary functions for condition checking and cross-validation [36] |

| Enzyme Inhibition Data | Experimental input for analysis | Formatted Excel files with Vmax, KM, IC50, and initial velocity measurements [36] |

| IC50 Estimation Assay | Preliminary inhibitor potency assessment | Standard enzyme activity measurements with varying inhibitor concentrations [32] |

| Multi-substrate Velocity Assay | Core experimental data generation | Initial velocity measurements with single IT > IC50 and varying ST values [3] |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Preliminary IC50 Determination

- Perform standard enzyme activity assays with a range of inhibitor concentrations (0-3×IC50)

- Use a single substrate concentration (typically KM)

- Fit dose-response curve to calculate IC50 value

Experimental Design for 50-BOA

- Select a single inhibitor concentration > IC50

- Choose at least two different substrate concentrations within 0.2KM to 5KM

- Measure initial reaction velocities for these conditions

Computational Analysis

- Format data according to package requirements

- Run Error_Landscape function with appropriate parameters

- Verify data adequacy using BOA_Condition output

- Extract inhibition constants with confidence intervals

Validation and Interpretation

- Check confidence interval width for precision assessment

- Compare Kic and Kiu values to determine inhibition type

- Utilize error landscape visualization for diagnostic purposes

The 50-BOA method represents a significant advancement in enzyme inhibition analysis, addressing critical limitations of traditional approaches while maintaining—and often enhancing—estimation precision. By reducing experimental requirements by over 75% and eliminating the need for prior knowledge of inhibition type, this approach offers substantial practical benefits for drug development pipelines and biochemical research.

The incorporation of error landscape analysis and IC50-based regularization provides a robust theoretical foundation, while user-friendly computational packages ensure accessibility for researchers across disciplines. As the field continues to prioritize efficiency and reproducibility, methodologies like 50-BOA establish new standards for biochemical characterization in pharmaceutical and academic settings.

The quantitative assessment of enzyme inhibition is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery. The inhibition constant (Ki), a direct measure of an inhibitor's binding affinity for its target enzyme, serves as a crucial parameter for ranking compound potency, defining selectivity, and predicting in vivo efficacy. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental approaches for determining inhibition constants, framed through case studies from three therapeutically significant enzyme families: monoamine oxidases (MAOs), cholinesterases, and HIV-1 protease. The accurate determination of these constants is not merely an academic exercise; it directly impacts the reliability of drug candidate selection and the understanding of therapeutic mechanisms. However, as we will explore, the experimental conditions under which Ki values are determined can profoundly influence the results, necessitating rigorous and well-optimized protocols [37].

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: From Natural Products to Selective Therapeutics

Background and Therapeutic Significance

Monoamine oxidases (MAO-A and MAO-B) are flavin-dependent enzymes bound to the outer mitochondrial membrane. They catalyze the oxidative deamination of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Although they share 70% sequence identity, they exhibit distinct substrate and inhibitor specificities. Selective MAO-A inhibitors are effective in the treatment of depression, while MAO-B inhibitors are useful for Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and also depression [38]. This therapeutic importance makes the accurate characterization of MAO inhibitors a vital activity in neuropharmacology.

Case Study: Kinetics of MAO Inhibition by Propolis Flavonoids

Dichloromethane extracts of propolis show potent, dose-dependent inhibition of both human MAO-A and MAO-B. Bioassay-guided fractionation identified the flavonoids galangin and apigenin as the principal inhibitory constituents. The kinetics of inhibition were characterized using recombinant human MAO enzymes, revealing that the binding of both flavonoids is reversible and time-independent [38].

The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Enzyme Source: Recombinant human MAO-A and MAO-B.

- Assay Conditions: A standard reaction mixture containing the enzyme, a buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), and a fluorogenic or chromogenic substrate (e.g., kynuramine for MAO-A, benzylamine for MAO-B).

- Inhibition Measurement: The test compound (e.g., galangin or apigenin) is incubated with the enzyme, and the reaction is initiated by adding the substrate. The initial velocity of the reaction is measured, often by detecting a fluorescent or colored product.

- Data Analysis: The mechanism of inhibition is determined by analyzing the initial velocity data at varying substrate and inhibitor concentrations. For galangin and apigenin, Lineweaver-Burk plots indicated a competitive mechanism, meaning the inhibitors bind directly to the enzyme's active site, competing with the substrate. The inhibition constant (Ki) is then calculated from this data [38].

Table 1: Inhibition of Recombinant Human MAO-A and MAO-B by Propolis Extract and its Constituents

| Sample Name | Monoamine Oxidase-A (IC₅₀) | Monoamine Oxidase-B (IC₅₀) | Selectivity (A/B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propolis Extract | 0.60 ± 0.12 μg/mL | 6.99 ± 0.09 μg/mL | ~10-fold (A) |

| Galangin | 0.13 ± 0.01 μM | 3.65 ± 0.15 μM | ~28-fold (A) |

| Apigenin | 0.64 ± 0.11 μM | 1.12 ± 0.27 μM | ~1.7-fold (A) |

| Quercetin | 2.44 ± 0.12 μM | 38.66 ± 1.20 μM | ~16-fold (A) |

| Clorgyline (Ref.) | 0.0065 ± 0.0003 μM | - | - |

| Deprenyl (Ref.) | - | 0.036 ± 0.0012 μM | - |

Data adapted from [38]. IC₅₀ values are Mean ± S.D. Ref.: Reference inhibitor.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors: Stopped-Flow Kinetics and Pesticide Detection

Background and Significance

Cholinesterases (ChEs), including acetylcholinesterase (AChE), are key enzymes in the nervous system, responsible for hydrolyzing the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Inhibitors of cholinesterases have applications ranging from the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's (e.g., donepezil) to use as pesticides (carbamates and organophosphates). The analysis of ChE inhibition is therefore critical in both neuroscience and environmental safety.

Case Study: Stopped-Flow Instrumentation for Kinetic Analysis

Stopped-flow instrumentation is a rapid-kinetics technique used to study fast enzymatic reactions, including the inhibition of cholinesterases. This method allows for the efficient and simultaneous determination of inhibitory potency for compounds like carbaryl and phoxim [39].

A generalized experimental protocol involves:

- Instrumentation: A stopped-flow apparatus, which rapidly mixes small volumes of enzyme and substrate/inhibitor solutions and monitors the reaction in real-time.

- Reaction Monitoring: The enzymatic reaction is typically followed by a change in absorbance or fluorescence. For AChE, a common assay uses acetylthiocholine as a substrate, which is hydrolyzed to thiocholine. Thiocholine then reacts with DTNB (Ellman's reagent) to produce a yellow-colored product that can be measured spectrophotometrically.