ELISA Protocols: A Comprehensive Guide from Setup to Validation for Biomedical Research

This article provides a complete guide to Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

ELISA Protocols: A Comprehensive Guide from Setup to Validation for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide to Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles and major ELISA types, detailed step-by-step protocols for direct, indirect, sandwich, and competitive formats, and their applications in drug discovery and diagnostics. The guide also offers systematic troubleshooting for common issues like high background and weak signal, optimization strategies for reagents and buffers, and a rigorous framework for assay validation including precision, accuracy, and regulatory compliance. By integrating foundational knowledge with advanced methodological and validation insights, this resource supports the development of robust, reliable immunoassays for clinical and research applications.

Understanding ELISA: Core Principles, Types, and Key Components

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a foundational technique in biochemical research and clinical diagnostics, leveraging the specificity of antigen-antibody interactions to detect and quantify soluble substances such as peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones [1] [2]. First described by Engvall and Perlmann in 1971, ELISA replaced radioimmunoassays by conjugating antigens and antibodies with enzymes instead of radioactive iodine 125, offering a safer and highly versatile platform [3] [2] [4]. The assay is performed in a microplate format, typically using 96- or 384-well polystyrene plates that passively bind proteins and antibodies, facilitating the separation of bound and unbound materials through simple washing steps [1].

The fundamental principle of ELISA relies on the immobilization of an antigen (or antibody) to a solid surface, followed by its detection using a specific antibody conjugated to a reporter enzyme [4]. The most crucial element is the highly specific antibody-antigen interaction, which ensures the assay's selectivity [1]. Detection is accomplished by measuring the activity of the reporter enzyme after incubation with a substrate, which generates a measurable product such as a color change [1] [2]. The intensity of this signal is proportional to the amount of analyte present in the sample [2].

The Biochemical Interaction: Antigen and Antibody

At the heart of every ELISA is the specific, non-covalent, and reversible biochemical interaction between an antigen and its corresponding antibody. An antigen is a substance (typically a protein, peptide, or polysaccharide) that can be recognized and bound by an antibody. The specific region on the antigen that the antibody recognizes is called an epitope [1]. Antibodies, or immunoglobulins, are Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system, with the tips of the "Y" (the variable regions) forming a unique binding pocket for a specific epitope.

This interaction is driven by multiple weak forces, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, Van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects. The cumulative effect of these forces results in a high-affinity binding that is both specific and strong, allowing the assay to distinguish the target analyte from other components in a complex mixture, such as serum or cell lysates [1]. In the context of ELISA, this interaction is harnessed and stabilized by immobilizing one component on a solid phase, enabling the thorough washing away of non-specifically bound materials to ensure a low background and high signal-to-noise ratio.

Common ELISA Formats and Methodologies

The core principle of antigen-antibody interaction is applied in different ELISA formats, each tailored for specific experimental needs. The major types are direct, indirect, sandwich, and competitive ELISA [2] [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Major ELISA Formats

| Format | Principle | Key Steps | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA | A labeled primary antibody detects immobilized antigen [2]. | 1. Antigen coating2. Blocking3. Incubation with enzyme-conjugated primary antibody4. Signal detection [2]. | Rapid; minimizes cross-reactivity from secondary antibodies [1]. | Lower sensitivity; expensive due to labeling every primary antibody [1] [2]. |

| Indirect ELISA | An unlabeled primary antibody is detected by a labeled secondary antibody [2]. | 1. Antigen coating2. Blocking3. Incubation with primary antibody4. Incubation with enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody5. Signal detection [3]. | High sensitivity due to signal amplification; flexible and cost-effective [1] [2]. | Potential for cross-reactivity with secondary antibody [1]. |

| Sandwich ELISA | The antigen is "sandwiched" between a capture antibody and a detection antibody [1] [2]. | 1. Capture antibody coating2. Blocking3. Sample (antigen) addition4. Incubation with detection antibody (direct or indirect)5. Signal detection [1] [2]. | Highest sensitivity and specificity; ideal for complex samples [1]. | Requires two antibodies recognizing different epitopes; more optimization needed [1]. |

| Competitive ELISA | Sample antigen and labeled reference antigen compete for binding to a limited number of antibody sites [1]. | 1. Antibody coating2. Simultaneous/additive incubation of sample and labeled antigen3. Signal detection [1] [2]. | Best for small antigens; less sample purification needed [1] [2]. | Lower specificity; signal decreases with increasing analyte [2]. |

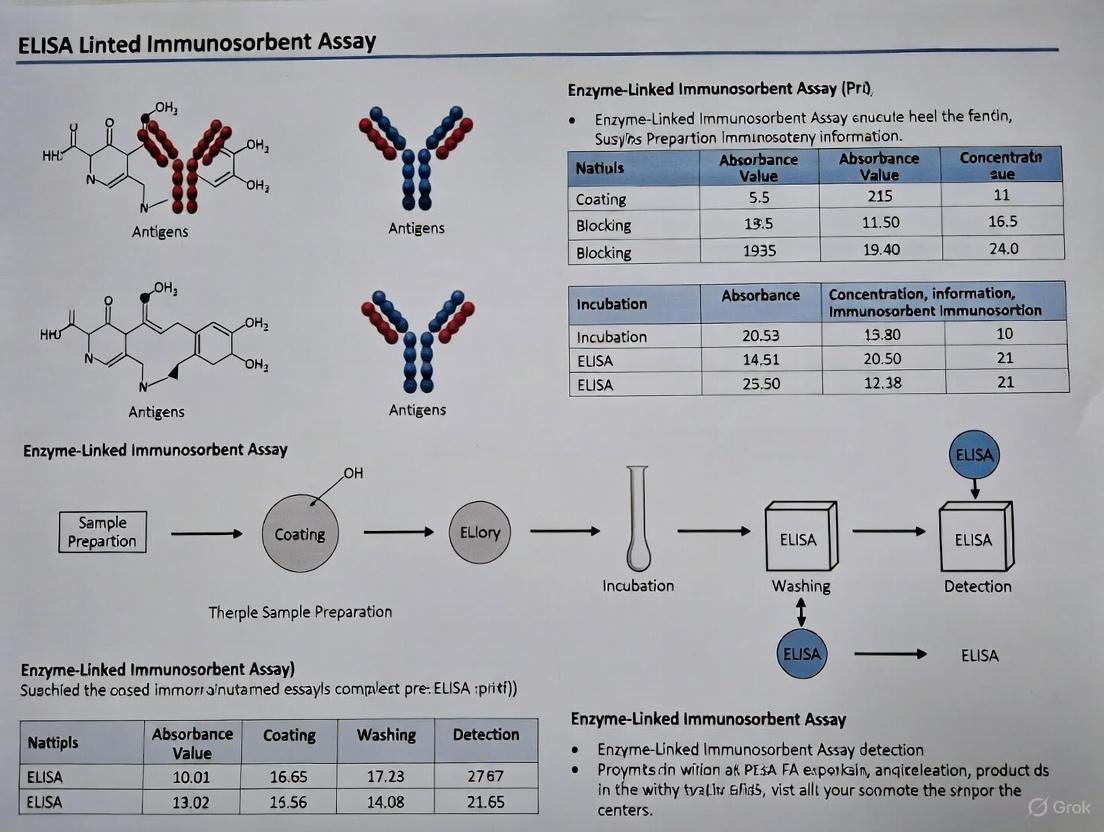

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points for performing a sandwich ELISA, the most widely used format:

Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful ELISA requires a suite of optimized reagents and proper laboratory equipment. The key components are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA

| Reagent / Material | Function | Common Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase | Provides a surface for immobilizing the capture molecule [3]. | 96- or 384-well polystyrene microplates; must have high protein-binding capacity and low well-to-well variation (CV <5%) [1]. |

| Coating Reagent | The first molecule immobilized to capture the target; can be an antigen or antibody [1]. | Diluted in an alkaline coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.4) to facilitate passive adsorption via hydrophobic interactions [1]. |

| Blocking Buffer | Covers any remaining unsaturated binding sites on the plate surface to prevent nonspecific binding of other proteins later in the assay [1] [2]. | Solutions of irrelevant proteins like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, or ovalbumin [2]. |

| Antibodies | Provide specificity for capturing and detecting the analyte. | Capture Antibody: Binds and immobilizes the antigen.Detection Antibody: Binds to the captured antigen; can be conjugated (direct) or detected via a secondary antibody (indirect) [1]. |

| Enzyme Conjugate | The reporter molecule linked to an antibody; catalyzes the conversion of a substrate into a detectable signal [1] [3]. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) are most common [1] [2]. |

| Substrate | The compound acted upon by the enzyme conjugate to generate a measurable signal [3]. | Colorimetric: TMB (turns yellow), pNPP (turns yellow). Chemiluminescent: Luminol-based (emits light). Choice depends on desired sensitivity and available readers [1] [2]. |

| Wash Buffer | Removes unbound reagents and proteins between steps to reduce background signal [2]. | Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or Tris-buffered saline, often with a non-ionic detergent like Tween-20 [3] [2]. |

| Stop Solution | An acidic or basic solution that halts the enzyme-substrate reaction at a defined timepoint [3]. | e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for HRP/TMB reaction, which also changes the color to a stable endpoint [3]. |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Accurate data analysis is critical for reliable quantification. Quantitative ELISA requires comparison with a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of a known concentration of the purified antigen [5].

- Standard Curve: The optical density (OD) of the standards is plotted against their concentration. The curve is typically non-linear, and fitting with a 4- or 5-parameter logistic (4PL or 5PL) model is recommended for the best fit, especially for immunoassays [5]. For competitive ELISA, the standard curve is inverted, with the highest concentration corresponding to the lowest OD [5].

- Calculating Concentration: The mean absorbance of the unknown sample is located on the y-axis of the standard curve, and a vertical line is drawn down to the x-axis to determine the concentration [5]. Samples with OD values outside the standard curve range must be diluted and re-assayed.

- Assay Validation: To ensure accuracy, samples should be run in duplicate or triplicate, with duplicates ideally within 20% of the mean. The Coefficient of Variation (CV) should be calculated, and spike/recovery experiments are recommended to check for matrix interference [5].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of data analysis in a quantitative ELISA:

Applications in Research and Drug Development

The versatility, sensitivity, and robustness of ELISA make it indispensable across numerous fields. Its primary applications include:

- Diagnostic Testing: Detecting and measuring antibodies (e.g., against HIV, Hepatitis, SARS-CoV-2) and autoantibodies (e.g., ANA, anti-dsDNA) in patient serum [2].

- Biomarker Quantification: Measuring levels of tumor markers (e.g., PSA, CEA), hormones (e.g., hCG, LH, testosterone), and cytokines in biological fluids for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring [3] [2].

- Drug Development and Pharmacodynamics: Used in pre-clinical and clinical studies to measure biomarkers of drug efficacy, pharmacokinetics (e.g., anti-drug antibodies), and target engagement [6].

- Quality Control: Ensuring the safety of donated blood by screening for viral contaminants and monitoring the quality and consistency of biopharmaceutical products [2] [4].

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay remains a cornerstone technology in life sciences, built upon the fundamental and powerful biochemical interaction between an antigen and an antibody. Its various formats provide flexible solutions for a wide range of quantitative and qualitative analytical challenges. A deep understanding of the underlying principles, combined with meticulous optimization of protocols and rigorous data analysis, is essential for researchers and drug development professionals to harness the full potential of ELISA in generating accurate, reliable, and meaningful data.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol research, this analysis provides a detailed comparison of the four principal ELISA formats. The ELISA technique, first developed in 1971 as a safer alternative to radioimmunoassay (RIA), has become a cornerstone method in research and diagnostic laboratories for detecting and quantifying specific proteins, antibodies, and other molecules [2] [7]. The core principle of all ELISA formats involves the specific binding of an antibody to its target antigen, with one component immobilized on a solid surface, typically a 96-well polystyrene plate [2] [3]. Detection is achieved via enzyme-conjugated antibodies that catalyze a colorimetric, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent reaction, the intensity of which is proportional to the amount of analyte present [3] [8]. The selection of an appropriate ELISA format—direct, indirect, sandwich, or competitive—is critical and depends on factors such as the nature of the analyte, the required assay sensitivity and specificity, the available reagents, and the experimental timeframe [9] [8]. This article provides application notes and detailed protocols to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting, optimizing, and executing these fundamental immunological assays.

The four major ELISA formats each possess a unique mechanism for antigen capture and detection, leading to distinct performance characteristics and ideal application scenarios. Direct ELISA is characterized by the use of a single enzyme-conjugated primary antibody that binds directly to the immobilized antigen [9] [10]. Indirect ELISA employs an unlabeled primary antibody, which is then detected by an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody raised against the host species of the primary antibody [2] [7]. Sandwich ELISA, the most common format for quantifying specific antigens in complex mixtures, uses two specific antibodies that bind to different epitopes on the target antigen, effectively "sandwiching" it [9] [8]. Competitive ELISA, also known as inhibition ELISA, operates on the principle of competition, where the analyte in the sample competes with a reference substance for binding to a limited number of antibody sites, resulting in a signal that is inversely proportional to the analyte concentration [9] [7].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the fundamental steps and logical relationships shared across the different ELISA formats, from immobilization to final quantification.

Table 1: Core Procedural Steps in ELISA Protocols. This workflow outlines the common sequence of operations in most ELISA formats, though the specific components used in each step (e.g., antigen vs. antibody for immobilization) vary by type [2] [3].

Comparative Advantages, Disadvantages, and Applications

A thorough understanding of the strengths and limitations of each format is essential for making an informed selection. The table below provides a consolidated summary of the key characteristics of each ELISA type.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Major ELISA Formats

| ELISA Format | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA [9] [8] | - Fast and simple protocol (fewer steps)- No cross-reactivity from secondary antibodies- Lower background noise | - Lower sensitivity- Limited to antigens that bind directly- Potential for high background with complex samples- Requires conjugated primary antibody for every target | - Rapid antigen screening- Assessing antibody affinity and specificity- Immune response analysis |

| Indirect ELISA [9] [7] | - Higher sensitivity (signal amplification)- Flexible (one labeled secondary can be used for many primaries)- Cost-effective | - More complex protocol (extra step)- Risk of cross-reactivity from secondary antibody- Longer procedure time | - Antibody detection and quantification (e.g., in serum)- Determining antibody titers (e.g., vaccine studies)- High-throughput serological surveys |

| Sandwich ELISA [9] [8] | - High sensitivity and specificity- Suitable for complex samples (e.g., serum, tissue lysates)- Low background and high precision | - Requires two specific antibodies against different epitopes- Technically demanding and longer protocol- Can be costly to develop | - Quantifying specific antigens in complex mixtures- Biomarker detection in disease diagnostics (e.g., cytokines, tumor markers)- Protein expression monitoring |

| Competitive ELISA [9] [10] | - Ability to quantify small molecules/haptens- Less susceptible to sample matrix effects- Requires only one specific antibody | - Lower sensitivity than sandwich or indirect ELISA- Inverse data interpretation can be complex- Requires careful optimization of competition conditions | - Detecting small molecules (drugs, hormones, contaminants)- Measuring haptens and inhibitors- Assessing antibody neutralization |

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

Direct ELISA Protocol

The direct ELISA is the most straightforward format, ideal for quick assessments when a conjugated primary antibody is available [8].

Detailed Protocol:

- Coating: Dilute the antigen to a concentration of 1–10 µg/mL in a coating buffer (e.g., carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6). Add 50–100 µL of this solution to each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Seal the plate and incubate overnight at 4°C or for 1–2 hours at 37°C [2] [3].

- Washing: Discard the coating solution. Wash the plate 2–3 times with a wash buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T). To wash, fill the wells completely with wash buffer, then discard the content by flicking the plate over a sink. Blot the plate on absorbent paper to remove residual liquid [2] [3].

- Blocking: Add 200–300 µL of a blocking buffer (e.g., 1–5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS) to each well to cover all potential protein-binding sites. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature or 37°C [2].

- Washing: Repeat the washing step as described in Step 2.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add 50–100 µL of the enzyme-conjugated primary detection antibody, diluted in blocking buffer, to each well. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature [9] [8].

- Washing: Repeat the washing step 3–4 times to ensure all unbound antibody is removed.

- Substrate Addition: Prepare the enzyme substrate according to the manufacturer's instructions. Common enzymes are Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), for which TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) is a common substrate, or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP), which uses pNPP (p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate) [2] [3]. Add 50–100 µL of the substrate solution to each well and incubate in the dark for 15–30 minutes at room temperature to allow color development.

- Stop Solution: To terminate the enzymatic reaction, add 50 µL of a stop solution (e.g., 1M H₂SO₄ for TMB, changing the color from blue to yellow; or 3M NaOH for pNPP) [3].

- Reading: Measure the absorbance of each well within 30 minutes using a microplate reader at the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB, 405 nm for pNPP) [3].

Indirect ELISA Protocol

The indirect ELISA introduces a secondary antibody for detection, providing greater sensitivity and flexibility [7].

Detailed Protocol:

- Coating and Washing: Identical to Steps 1 and 2 of the Direct ELISA protocol. Coat the plate with the antigen of interest.

- Blocking and Washing: Identical to Steps 3 and 4 of the Direct ELISA protocol.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Add 50–100 µL of the unlabeled, antigen-specific primary antibody (e.g., patient serum if detecting antibodies) diluted in blocking buffer to each well. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature or 37°C [2] [7].

- Washing: Wash the plate 3–4 times as before to remove unbound primary antibody.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Add 50–100 µL of an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., Goat Anti-Human IgG-HRP if the primary is from a human sample) diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature [2] [10].

- Washing, Substrate, Stop, and Reading: Identical to Steps 6–9 of the Direct ELISA protocol. The signal is amplified because multiple secondary antibodies can bind to a single primary antibody.

Sandwich ELISA Protocol

The sandwich ELISA offers superior specificity and is the format of choice for quantifying antigens in complex biological samples [8] [7].

Detailed Protocol:

- Coating: Dilute the capture antibody to 2–10 µg/mL in coating buffer. Add 50–100 µL per well and incubate overnight at 4°C. Note: The capture antibody must be specific to a different epitope on the antigen than the detection antibody [2] [8].

- Washing and Blocking: Identical to Steps 2–4 of the Direct ELISA protocol.

- Sample and Standard Incubation: Add 50–100 µL of the sample or a serial dilution of the antigen standard (prepared in blocking buffer or a sample matrix) to each well. Incubate for 90 minutes at 37°C or 2 hours at room temperature to allow the antigen to be captured [2] [11].

- Washing: Wash the plate 3–5 times thoroughly to remove all unbound material from the sample.

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add 50–100 µL of the biotinylated or enzyme-conjugated detection antibody, diluted in blocking buffer, to each well. Incubate for 1–2 hours at room temperature [2] [8].

- Washing: Wash the plate 3–5 times.

- (Optional) Signal Amplification: If using a biotinylated detection antibody, add 50–100 µL of enzyme-conjugated streptavidin (e.g., Streptavidin-HRP) diluted in blocking buffer. Incubate for 30–60 minutes at room temperature. This step significantly amplifies the signal [8] [10].

- Washing: Perform a final 3–5 washes.

- Substrate, Stop, and Reading: Identical to Steps 7–9 of the Direct ELISA protocol. Generate a standard curve from the serial dilutions to interpolate the exact concentration of the antigen in the samples [9].

Competitive ELISA Protocol

The competitive ELISA is particularly useful for measuring small molecules that cannot be bound by two antibodies simultaneously [9] [10].

Detailed Protocol (One Common Format):

- Coating: Coat the plate with a known amount of purified antigen (not the sample antigen). Alternatively, the plate can be coated with a specific capture antibody. Follow the coating, washing, and blocking steps from the Direct or Sandwich ELISA protocols [9].

- Competition Incubation: In a separate tube, pre-mix a constant, known amount of the enzyme-conjugated antibody with a series of dilutions of the sample containing the unknown antigen. Incubate this mixture for 1–2 hours at 37°C. During this step, the antigen in the sample and the enzyme-conjugated antigen (if using that format) compete for the limited binding sites on the labeled antibody [9] [7].

- Transfer and Incubation: Transfer the pre-mixed solutions to the coated and blocked plate. Incubate for a further 30–60 minutes. The amount of labeled antibody that can subsequently bind to the immobilized antigen on the plate is inversely proportional to the amount of antigen present in the sample.

- Washing: Wash the plate thoroughly to remove all unbound components, including the sample antigen-antibody complexes.

- Substrate, Stop, and Reading: Identical to Steps 7–9 of the Direct ELISA protocol. A weaker signal indicates a higher concentration of the target analyte in the sample [9].

The following diagram visualizes the distinct antigen-antibody interactions and key procedural differences between the four major ELISA formats.

Table 3: Core Mechanisms of Major ELISA Formats. This diagram summarizes the fundamental immunological principles that differentiate each ELISA type, which dictates their specific applications and performance [9] [8] [7].

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Specialized Application Notes

The choice of ELISA format is driven by the specific analytical question. The following examples from recent literature illustrate their application in diverse fields.

Sandwich ELISA for Food Allergen Detection: To protect consumers, detecting trace amounts of undeclared food allergens is critical. A research group developed a sensitive and specific sandwich ELISA for detecting pistachio residues in processed foods. They used pooled sheep antisera as the capture reagent and pooled rabbit antisera as the detector reagent. The assay demonstrated a limit of quantification (LOQ) of less than 1 part per million (ppm) and was successfully used to recover pistachio from spiked model foods like vanilla ice cream and sugar cookies, showcasing its utility for food safety compliance [11].

Indirect ELISA for Cancer Biomarker Quantification: In cancer research, accurately measuring tumor suppressor proteins is essential. A 2023 study developed an indirect ELISA to quantify ARID1A, a protein frequently mutated in gynecologic cancers, in tissue lysates. The researchers coated the plate with cell or tissue lysates and used a specific primary antibody followed by an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody. The assay was rigorously validated according to EMA and FDA guidelines, achieving a standard curve with an R² = 0.99 and excellent inter-assay precision, providing a more objective and quantitative alternative to semi-quantitative immunohistochemistry [12].

Sandwich ELISA for Immunological Biomarker Validation: In the study of innate immunity, a highly sensitive and specific sandwich ELISA was established for quantifying Collectin 11 (CL-11) in human serum. The assay was based on two different monoclonal antibodies, providing high specificity. It exhibited excellent reproducibility, dilution linearity, and recovery (97.7–104%), with a working range of 0.15–34 ng/ml. This reliable method facilitates the study of CL-11 levels in various human diseases and syndromes [13].

Competitive ELISA for Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Inhibitor Screening: In drug development, competitive ELISAs are invaluable for quantifying small molecules. They are used in inhibitor screening to identify candidate molecules with pharmacological effects during early-stage drug discovery [14]. Furthermore, competitive ELISA formats have been developed to measure the concentration of biologic drugs (like monoclonal antibodies) in serum samples for pharmacokinetic (PK) studies, offering advantages over traditional methods by avoiding background interference [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of any ELISA protocol relies on high-quality, well-validated reagents and proper laboratory equipment. The following table details the essential components of an ELISA toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ELISA

| Item | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates [2] [12] | 96-well polystyrene plates with high protein-binding capacity (e.g., NUNC MaxiSorp) are standard. The hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity of the plate should be considered based on the analyte. |

| Coating Antibodies/Antigens [8] | High-affinity, specific monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies (for sandwich/competitive) or purified antigens (for direct/indirect) are required for the initial immobilization step. |

| Detection Antibodies [8] [7] | For sandwich ELISA, a matched antibody pair (capture and detection) recognizing different epitopes is critical. Antibodies are typically conjugated to enzymes like HRP or AP, or to biotin for amplification. |

| Blocking Buffers [2] | Solutions containing irrelevant proteins (e.g., 1-5% BSA, non-fat dry milk, or animal sera) are used to block unbound sites on the plate to prevent nonspecific binding and reduce background noise. |

| Wash Buffers [2] [3] | Typically PBS or Tris-based buffers with a mild detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween-20) to facilitate the removal of unbound reagents and reduce non-specific signal. |

| Enzyme Substrates [2] [3] | Chromogenic (e.g., TMB for HRP, pNPP for AP), chemiluminescent, or fluorescent substrates are converted by the enzyme into a measurable signal. TMB is common, producing a blue color that turns yellow when stopped with acid. |

| Spectrophotometric Plate Reader [3] | An essential instrument for measuring the absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence of the wells in the plate, allowing for the quantification of the assay results. |

In conclusion, the selection and proficient execution of an ELISA format are foundational to success in both basic research and applied drug development. By understanding the comparative strengths of each format, adhering to detailed protocols, and utilizing a well-characterized toolkit of reagents, scientists can leverage the full power of ELISA to generate precise, reliable, and meaningful quantitative data.

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is a foundational technique in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, leveraging the specificity of antigen-antibody interactions and enzymatic signal generation for the detection and quantification of target analytes. The performance of an ELISA hinges on the precise interplay of specialized reagents, consumables, and instrumentation. A thorough understanding of these core components—from the coated plates that serve as the solid phase to the specialized buffers that optimize interactions and the readers that quantify results—is critical for developing robust, sensitive, and reproducible assays. This document details the essential materials and methodologies required to execute reliable ELISA protocols, framed within the context of advanced immunoassay research and development.

Essential Reagents and Materials

The following section catalogs the fundamental reagents and materials that constitute the "research reagent solutions" for a typical ELISA workflow. Each component plays a specific role in ensuring the assay's specificity, sensitivity, and overall performance.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for ELISA

| Component | Function | Key Types & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase (Microplate) [15] | Provides a surface for immobilizing the capture antibody or antigen. | 96-well polystyrene plates; High-binding, medium-binding, or non-binding surface treatments. |

| Coating Antibody/Antigen [16] | The biomolecule immobilized on the plate to specifically capture the target analyte. | Purified capture antibody (for sandwich ELISA) or specific antigen (for indirect/competitive ELISA). |

| Blocking Buffer [17] | Binds to any unsaturated surface-binding sites on the coated plate to prevent non-specific binding of other proteins. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [16], casein, or proprietary commercial blockers [17]. |

| Detection Antibody [7] | Binds specifically to the captured analyte. Often conjugated to an enzyme for detection. | Monoclonal or polyclonal antibody; Can be direct (enzyme-conjugated) or indirect (recognized by a secondary antibody). |

| Enzyme Conjugate [3] [7] | Enzyme linked to the detection system catalyzes the conversion of a substrate into a measurable signal. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) or Alkaline Phosphatase (AP). |

| Substrate [16] [17] | The chromogenic, chemiluminescent, or fluorescent compound acted upon by the enzyme conjugate to generate a signal. | TMB (colorimetric for HRP), pNPP (colorimetric for AP), or luminol-based (chemiluminescent for HRP). |

| Stop Solution [3] [16] | An acidic or basic solution that halts the enzyme-substrate reaction at a defined timepoint. | 0.16M Sulfuric Acid (for TMB), 1M Sodium Hydroxide (for pNPP). |

| Wash Buffer [3] [17] | Removes unbound reagents and proteins from the microplate wells between incubation steps, reducing background. | Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS), often with a detergent like Tween-20. |

| Assay Diluent [17] | A matrix used to dilute samples and standards to an appropriate concentration while minimizing matrix effects. | Protein-based or protein-free commercial diluents designed to reduce non-specific interference. |

Critical Equipment and Instrumentation

The accurate execution and measurement of an ELISA require specific instruments that ensure precise liquid handling, controlled incubation, and sensitive signal detection.

Table 2: Essential Equipment for ELISA

| Equipment | Primary Function | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Microplate Reader [3] | Measures the signal generated in each well of the microplate. | Absorbance (for colorimetric), luminescence, or fluorescence detectors; Compatible with 96-well or 384-well formats. |

| Microplate Washer [16] | Automates the washing steps, ensuring thorough and consistent removal of unbound material from all wells. | Programmable wash cycles, adjustable aspiration and dispense volumes. |

| Pipettes & Tips | Enables accurate and precise transfer and aliquoting of reagents and samples. | Single-channel and multi-channel pipettes covering a range of volumes (e.g., 1µL to 1mL). |

| Incubator | Maintains a constant temperature during assay incubation steps, which is critical for consistent binding kinetics. | Capable of maintaining 37°C ± 0.5°C; some assays require room temperature or other set points. |

| Analytical Software | Analyzes the raw data from the plate reader, generates standard curves, and calculates analyte concentrations in samples. | Software provided with the plate reader or third-party data analysis packages. |

Detailed ELISA Protocols

This section provides step-by-step methodologies for the most common types of ELISA, highlighting the role of each essential reagent and critical control points.

Sandwich ELISA Protocol

The sandwich ELISA is renowned for its high specificity and sensitivity, making it ideal for detecting complex antigens in crude samples [7]. It requires two antibodies that bind to distinct epitopes on the target antigen.

Procedure:

- Coating: Dilute the capture antibody in a suitable coating buffer (e.g., 0.2M carbonate/bicarbonate, pH 9.6). Dispense 100 µL per well into a high-binding 96-well microplate. Seal the plate and incubate overnight at 4°C [16].

- Washing: Aspirate the coating solution and wash the plate three times with ~300 µL of wash buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) per well. Blot the plate firmly on clean paper towels to remove residual liquid [7] [16].

- Blocking: Add 200-300 µL of blocking buffer (e.g., 5% BSA or a commercial protein blocker) to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate three times as before [16] [17].

- Sample & Standard Incubation: Prepare serial dilutions of the standard in the same matrix as the sample. Add 100 µL of standards, samples, and appropriate controls (e.g., blank) to designated wells. Incubate for 2 hours at room temperature or 37°C. Wash the plate three times [3].

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add 100 µL of the detection antibody (conjugated to HRP or AP) diluted in assay diluent to each well. Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature. Wash the plate three times [7].

- Substrate Addition: Add 100 µL of substrate solution (e.g., TMB for HRP) to each well. Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes to allow color development [16].

- Stop the Reaction: Add 50-100 µL of stop solution (e.g., 0.16M sulfuric acid for TMB) to each well. The color will change from blue to yellow if TMB is used.

- Reading & Analysis: Measure the absorbance of each well within 30 minutes using a microplate reader set to the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 450 nm for TMB). Generate a standard curve by plotting the absorbance against the standard concentration and use it to interpolate the concentration of the unknown samples [3].

Competitive ELISA Protocol

The competitive ELISA is typically used for detecting small molecules or antigens with a single epitope. The signal generated is inversely proportional to the amount of analyte in the sample [3] [7].

Procedure:

- Coating: Coat wells with a known amount of the purified antigen (or an antibody, depending on the format) as described in step 4.1.1.

- Blocking: Block the plate as described in step 4.1.3.

- Competitive Reaction: Pre-mix a constant amount of enzyme-conjugated antigen (or antibody) with serially diluted standards or samples. The analyte in the sample competes with the labeled antigen for a limited number of antibody binding sites.

- Incubation: Transfer the mixture to the antigen-coated plate and incubate. The less analyte present in the sample, the more conjugated antigen will bind to the plate.

- Washing: Wash the plate thoroughly to remove any unbound conjugate.

- Substrate, Stop, and Read: Add substrate, stop solution, and read the plate as described in steps 4.1.6 to 4.1.8. A lower signal indicates a higher concentration of analyte in the sample.

Key Considerations for Protocol Optimization

- Antibody Validation: Antibodies must be specifically validated for use in ELISA to ensure high affinity and specificity for the target analyte [16].

- Matrix Effects: The sample matrix (e.g., serum, plasma) can interfere with the assay. Conduct spike-and-recovery experiments to evaluate and mitigate matrix effects [16].

- Controls: Always include appropriate controls: blank (assay diluent only), negative control (sample known to lack the analyte), and positive control (sample with a known concentration of analyte).

Advanced Reagent and Protocol Innovations

Recent advancements in nanotechnology and material science have led to significant improvements in ELISA performance, particularly in sensitivity and ease of use [18].

- Nanozymes: Nanomaterials with enzyme-like activities (e.g., peroxidase-like activity) are used as stable and cost-effective alternatives to natural enzymes like HRP, enhancing catalytic stability and sensitivity [18].

- Fluorescent and Chemiluminescent Substrates: The integration of highly sensitive fluorescent and chemiluminescent detection methods, often referred to as FELISA, offers a broader dynamic range and several-fold higher sensitivity compared to traditional colorimetric detection [16] [18].

- Signal Amplification Systems: Systems like the biotin-streptavidin interaction, which has a high binding affinity, allow for significant signal amplification by enabling multiple enzyme molecules to bind per detection antibody [7] [16].

Advantages and Inherent Limitations of ELISA in Research and Diagnostics

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) stands as a cornerstone technique in immunology and diagnostics, renowned for its ability to detect and quantify peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones with notable sensitivity and specificity [3] [19]. This assay detects antigen-antibody interactions using enzyme-labelled conjugates and substrates that generate a measurable color change, providing a versatile tool for both research and clinical applications [3]. The technique's evolution since the 1960s has solidified its position as an indispensable method in laboratories worldwide [3]. Despite the emergence of sophisticated technologies like Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), ELISA maintains widespread adoption due to its relative simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high-throughput capabilities [20]. This application note examines the technical advantages and inherent limitations of ELISA within the context of modern research and diagnostic paradigms, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for practitioners.

Core Principles and Types of ELISA

The fundamental principle of ELISA revolves around the specific binding between an antigen and its antibody, with the detection achieved via an enzyme-linked conjugate that produces a colorimetric signal upon reacting with a substrate [3]. The key components essential for any ELISA include: a solid phase (typically a 96-well microplate); a conjugate (enzyme-labelled antibodies); a substrate; wash buffers; and a stop solution to terminate the reaction [3]. The intensity of the final color, measured spectrophotometrically as optical density (OD), correlates with the concentration of the target analyte [3] [19].

Several ELISA formats have been developed to address different experimental needs, each with distinct mechanisms and applications:

Direct ELISA

In this format, a known antibody is coated onto the plate, followed by addition of the sample containing the suspected antigen. After binding and washing, an enzyme-linked antibody specific to the antigen is added, followed by substrate. This method is relatively simple but may offer lower sensitivity [3].

Indirect ELISA

Used primarily for antibody detection, this method coats the plate with a known antigen. The sample containing the primary antibody is added, followed by an enzyme-linked secondary antibody that recognizes the primary antibody. This amplification step enhances sensitivity but may increase non-specific binding [3].

Sandwich ELISA

The most sensitive format for antigens, Sandwich ELISA employs a capture antibody coated onto the plate that binds the target antigen. A second, enzyme-linked detection antibody then binds to the captured antigen, creating a "sandwich." This format is particularly useful for complex samples but requires two distinct antibodies recognizing different epitopes [19].

Competitive ELISA

Commonly used for small molecules, this format operates on the principle of competition between the patient's antigen and a labeled antigen for binding to limited antibody sites. Higher analyte concentration in the sample results in less binding of the labeled antigen and consequently a weaker signal [3] [19]. This format is especially valuable for detecting small molecules or when only one specific antibody is available.

Table 1: Comparison of Major ELISA Formats

| Format | Principle | Sensitivity | Applications | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Antigen is detected by enzyme-labeled primary antibody | Moderate | Antigen detection | Simple, rapid, minimal cross-reactivity | Lower sensitivity, primary antibody must be labeled |

| Indirect | Antigen is detected by primary antibody followed by enzyme-labeled secondary antibody | High | Antibody detection, serology | Signal amplification, flexible, same secondary antibody can be used for multiple primaries | Potential for cross-reactivity, longer procedure |

| Sandwich | Antigen captured between two antibodies | Very High | Cytokine measurement, protein quantification | High specificity and sensitivity, suitable for complex samples | Requires two matched antibodies recognizing different epitopes |

| Competitive | Sample antigen competes with labeled antigen for antibody binding sites | Variable (depends on target) | Small molecules, haptens, drugs | Robust, less affected by sample matrix, ideal for small antigens | Inverse relationship between signal and concentration |

Advantages of ELISA

Technical and Operational Advantages

ELISA offers numerous technical benefits that sustain its popularity across diverse laboratory settings:

High Throughput Capability: The 96-well microplate format enables simultaneous processing of numerous samples, making ELISA ideal for large-scale screening studies, epidemiological surveillance, and clinical diagnostics [3] [21]. Automated plate washers and readers further enhance processing efficiency.

Excellent Sensitivity and Specificity: Modern ELISA kits can detect targets at picogram per milliliter concentrations, sufficient for most clinical and research applications [3]. The combination of highly specific antibody-antigen interactions and optimized blocking/washing steps minimizes cross-reactivity.

Quantitative Precision: When properly optimized with appropriate standard curves and replicates, ELISA provides highly reproducible quantitative data. The 4-parameter logistic (4PL) model typically offers the best fit for the sigmoidal standard curves generated in quantitative assays [19].

Simplicity and Accessibility: Compared to techniques like LC-MS/MS that require specialized instrumentation and expertise, ELISA utilizes standard laboratory equipment and can be established in most research or clinical settings with minimal infrastructure investment [20].

Economic and Practical Advantages

Cost-Effectiveness: ELISA represents a economically viable option for many laboratories, with lower per-test costs compared to advanced instrumental methods [20]. The availability of commercial kits from multiple suppliers (including Bio-Rad Laboratories, Fisher Scientific, and Thermo Fisher Scientific) ensures competitive pricing [22].

Proven Reliability and Established Protocols: Decades of refinement have yielded robust, validated protocols for countless analytes. The technique's long history means troubleshooting resources are widely available, and many applications have been standardized for regulatory compliance [3] [6].

Adaptability to Various Sample Matrices: ELISA has been successfully applied to diverse biological fluids including serum, plasma, urine, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, and tissue culture supernatants [3]. Sample preparation is typically minimal, though matrix effects must be considered and addressed through appropriate controls.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its numerous advantages, ELISA possesses inherent limitations that researchers must acknowledge and address experimentally:

Technical Limitations

Antibody Dependency and Specificity Issues: The performance of any ELISA fundamentally depends on the quality and specificity of the antibodies employed. Cross-reactivity with similar epitopes or related molecules can yield false-positive results [20]. This limitation is particularly relevant when analyzing samples from multiple species, as commercial kits validated for human applications may perform differently with animal specimens [21].

Matrix Effects: Components in complex biological samples can interfere with antibody-antigen binding or generate non-specific signals, potentially compromising accuracy [20]. This necessitates careful optimization of sample dilution and inclusion of appropriate matrix-matched controls.

Dynamic Range Constraints: The effective working range of standard ELISA is typically limited to 1.5-2 logs, potentially requiring sample dilution or concentration to bring unknown values within the quantifiable range [19]. This contrasts with LC-MS/MS, which often offers wider dynamic ranges [20].

Limited Multiplexing Capacity: Traditional ELISA measures a single analyte per well, restricting the amount of information obtainable from limited sample volumes. While multiplex platforms exist, they often require specialized instrumentation and remain less common than conventional formats.

Practical and Operational Challenges

Standardization Variability: Different commercial kits for the same analyte may yield disparate results due to variations in antibody pairs, standard preparations, or buffer compositions [21]. A 2025 comparative study of SARS-CoV-2 ELISA kits demonstrated significant performance differences, with diagnostic sensitivity varying between kits targeting different viral antigens [21].

Inability to Distinguish Isoforms and Modifications: Unlike mass spectrometry, ELISA generally cannot differentiate between various post-translationally modified forms of a protein or closely related molecular isoforms unless specifically designed to do so [20]. This limitation can obscure important biological nuances.

Sensitivity Ceiling: While sufficient for many applications, ELISA's sensitivity has inherent limits due to the enzymatic reaction kinetics and detection methodology. For trace-level analysis requiring detection beyond the femtogram range, more sensitive techniques like LC-MS/MS may be necessary [20].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis: ELISA vs. LC-MS/MS

| Feature | ELISA | LC-MS/MS |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Antibody-antigen interaction | Separation and fragmentation by mass spectrometry |

| Complexity | Simple, single-step assay | Multistep, complex technique |

| Cost-effectiveness | Relatively inexpensive | More expensive |

| Sensitivity | Good for moderate concentrations (typically pg/mL) | Excellent for trace-level detection (often fg/mL) |

| Specificity | Can be affected by cross-reactivity | Highly specific |

| Throughput | High | Moderate |

| Multiplexing | Limited (usually single analyte) | Extensive (can measure hundreds simultaneously) |

| Ability to detect modifications | Limited unless specific antibodies are available | Excellent |

| Instrument requirements | Standard laboratory equipment | Specialized, costly instrumentation |

| Operator expertise | Moderate technical training required | Advanced technical expertise necessary |

| Sample preparation | Minimal to moderate | Extensive |

Detailed Protocol: Sandwich ELISA for Protein Quantification

The following protocol provides a standardized approach for sandwich ELISA, adaptable to various protein targets with appropriate antibody reagents.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Phase | 96-well microplates (polystyrene, polyvinyl) | Platform for immobilizing capture antibody and subsequent reactions |

| Coating Antibody | Target-specific capture antibody | Binds and immobilizes the target antigen from the sample |

| Detection Antibody | Enzyme-conjugated target antibody | Binds captured antigen; enzyme generates detectable signal |

| Coating Buffer | Carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) | Optimal pH for passive adsorption of antibodies to plastic surface |

| Wash Buffer | PBS with 0.05% Tween-20 | Removes unbound materials while maintaining protein stability |

| Blocking Buffer | PBS with 1-5% BSA or non-fat dry milk | Covers uncovered plastic surface to prevent non-specific binding |

| Standard | Recombinant protein of known concentration | Generates standard curve for quantitative interpolation |

| Substrate | TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Chromogenic enzyme substrate that produces measurable color change |

| Stop Solution | 1M H₂SO₄ or 1M HCl | Terminates enzyme-substrate reaction at defined timepoint |

| Instrumentation | Microplate reader, microplate washer, pipettes | Enables precise liquid handling, washing, and signal measurement |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Plate Coating:

- Dilute capture antibody in coating buffer to manufacturer's recommended concentration (typically 1-10 μg/mL).

- Add 100 μL per well to a 96-well microplate.

- Seal plate and incubate overnight at 4°C or for 2 hours at room temperature.

Washing and Blocking:

- Aspirate contents and wash plate 3 times with 300 μL wash buffer per well.

- Add 300 μL blocking buffer to each well.

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking.

Standard and Sample Incubation:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the standard protein in appropriate matrix.

- Dilute test samples in the same matrix.

- Wash plate 3 times as before.

- Add 100 μL of standards, samples, and blanks to appropriate wells in duplicate or triplicate.

- Cover plate and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature or according to kit specifications.

Detection Antibody Incubation:

- Wash plate 3 times.

- Add 100 μL of appropriately diluted detection antibody to each well.

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

Signal Development:

- Wash plate 5 times to ensure complete removal of unbound detection antibody.

- Add 100 μL substrate solution to each well.

- Incubate in the dark for 15-30 minutes, monitoring color development.

Signal Measurement:

- Add 50 μL stop solution to each well.

- Read optical density at 450 nm within 30 minutes using a microplate reader.

- Subtract reference wavelength (570 nm or 630 nm) if applicable to correct for optical imperfections.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Background Subtraction: Calculate mean OD of blank wells and subtract from all standard and sample readings.

Standard Curve Generation:

- Plot log of standard concentration versus corrected OD values.

- Apply appropriate curve fit (typically 4-parameter logistic for sandwich ELISA): Where A = minimum asymptote, B = slope factor, C = inflection point (EC50), D = maximum asymptote [19].

Sample Concentration Calculation:

- Interpolate sample concentrations from the standard curve.

- Multiply by any applicable dilution factors to obtain final concentration.

Quality Assessment:

- Calculate coefficient of variation (CV%) for replicates: CV% = (Standard Deviation ÷ Mean) × 100.

- Acceptable intra-assay CV is typically <10-15% [19].

- Verify standard curve fit with R² > 0.98.

Troubleshooting Common ELISA Issues

Even with optimized protocols, technical challenges may arise. The following table addresses common problems and their solutions:

Table 4: Troubleshooting Guide for Common ELISA Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low OD or No Signal | - Expired or degraded substrate- Inadequate incubation times- Improper reagent preparation- Over-washing | - Use fresh substrate aliquots- Validate incubation conditions- Calibrate pipettes and confirm concentrations- Optimize wash cycles |

| High Background | - Incomplete washing- Excessive detection antibody concentration- Inadequate blocking- Contaminated reagents | - Increase wash cycles and ensure thorough aspiration- Titrate detection antibody for optimal dilution- Extend blocking time or try alternative blocking agents- Prepare fresh reagents with purified water |

| High Variation Between Replicates | - Inconsistent pipetting- Plate edge effects- Inhomogeneous samples- Bubble formation in wells | - Calibrate pipettes and use reverse pipetting for viscous samples- Use plate sealers during incubations- Centrifuge samples before use and mix thoroughly- Tap plate gently to remove bubbles before reading |

| Poor Standard Curve Fit | - Improper standard serial dilution- Inadequate standard concentration range- Plate reader malfunction | - Prepare fresh standard dilutions with thorough mixing- Ensure standard points cover expected sample range- Validate plate reader performance with calibration plates |

| Non-linear Dilution of Samples | - Matrix interference- Target concentration outside dynamic range- Hook effect (very high antigen concentrations) | - Dilute samples in appropriate matrix- Test multiple sample dilutions to find linear range- If hook effect is suspected, test higher sample dilutions |

Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

The ELISA platform continues to evolve, with ongoing innovations addressing its traditional limitations. Automated ELISA systems from companies like Tecan, Hamilton Robotics, and Hudson Robotics are enhancing reproducibility and throughput while reducing manual errors [23]. Digital ELISA technologies are pushing sensitivity boundaries toward single-molecule detection, potentially bridging the sensitivity gap with LC-MS/MS for some applications [3].

The growing integration of ELISA with big data analytics represents another frontier, where large datasets generated from high-throughput ELISA screening are mined for biomarker discovery and systems biology applications. Furthermore, the development of multiplexed bead-based immunoassays extends the multiplexing capacity beyond traditional ELISA while maintaining the core antibody-antigen detection principle.

According to market analysis, the ELISA testing platform is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.3% from 2025 to 2032, reflecting continued innovation and adoption in both diagnostic and research settings [23]. This growth is fueled by increasing demand for diagnostic testing, particularly for infectious diseases and chronic conditions, as well as ongoing technological advancements.

ELISA remains a powerful and versatile technique that strikes a balance between practicality, sensitivity, and throughput for numerous applications in research and diagnostics. Its advantages of accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and robust performance ensure its continued relevance, while its limitations regarding specificity, dynamic range, and multiplexing necessitate careful experimental design and interpretation. By understanding both the capabilities and constraints of this foundational technology, researchers and clinicians can make informed decisions about its appropriate implementation and complementarity with emerging analytical platforms. As the technique continues to evolve, ELISA will likely maintain its position as an essential tool in the biomedical sciences for the foreseeable future.

ELISA Type Selection Guide

ELISA Experimental Workflows

Executing Robust ELISA Protocols: Step-by-Step Guide and Real-World Applications

This application note provides a detailed protocol for the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), a foundational technique in biomedical research and drug development. ELISA is a plate-based assay for the detection and quantification of peptides, proteins, antibodies, and hormones, leveraging the specific binding between an antigen and an antibody, with detection facilitated by an enzyme-linked conjugate [24] [25]. This document is framed within broader research on optimizing ELISA protocols for reproducibility and sensitivity, catering to the needs of researchers and scientists engaged in protein detection and quantification. The sandwich ELISA format, known for its high specificity and suitability for complex samples, will be the primary focus [24] [26].

Principle of the Assay

The ELISA technique is predicated on the immobilization of a target antigen to a solid surface (typically a polystyrene microplate) and its subsequent detection by an antibody linked to an enzyme. The conversion of a substrate by the enzyme into a measurable product, such as a colorimetric, fluorometric, or chemiluminescent signal, allows for the quantification of the analyte of interest [24] [25]. The sandwich ELISA, a common format, employs two antibodies that bind to distinct, non-overlapping epitopes on the target antigen. This "sandwiches" the antigen between a capture antibody immobilized on the plate and a detection antibody conjugated to an enzyme, enhancing specificity and reducing background [24] [26].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential materials and reagents required to perform a standard sandwich ELISA.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for Sandwich ELISA

| Item | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| Microplate | 96-well polystyrene plates are standard. Clear for colorimetry, black/clear-bottom for fluorescence, white for chemiluminescence [16]. |

| Capture Antibody | The first antibody, specific to the target antigen, is immobilized on the plate to facilitate capture [26]. |

| Detection Antibody | The second antibody, binding a different epitope on the antigen; often enzyme-conjugated (e.g., HRP or AP) [26]. |

| Coating Buffer | 0.2 M carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.4-9.6) is common; must be protein-free to avoid competitive binding [16]. |

| Blocking Buffer | 3-5% BSA in PBS or 5% normal serum to cover any remaining protein-binding sites on the plate, minimizing non-specific binding [16] [26]. |

| Wash Buffer | PBS or Tris-buffered saline (TBS), often with 0.05% Tween 20, to remove unbound materials during wash steps [26]. |

| Sample/Diluent Buffer | Buffer used to dilute samples and standards, typically containing a protein base like BSA to stabilize proteins [26]. |

| Enzyme Substrate | Solution added for detection. TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) is a common colorimetric substrate for HRP [16]. |

| Stop Solution | Acid (e.g., 0.16M sulfuric acid for TMB) to terminate the enzyme-substrate reaction, stabilizing the signal for reading [16]. |

Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation

Proper sample handling is critical for assay integrity. General guidelines for various sample types are summarized below. Always keep samples on ice or at 4°C and minimize freeze-thaw cycles [26].

Table 2: Sample Preparation Guidelines

| Sample Type | Preparation Protocol |

|---|---|

| Cell Culture Supernatants | Centrifuge media at 1,500-10,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Aliquot and store the supernatant at -80°C [24] [26]. |

| Cell Extracts | Wash cells with cold PBS. Lyse cells in extraction buffer with protease inhibitors on ice for 15-30 min. Centrifuge at 13,000-18,000 x g for 10-20 min at 4°C. Collect, aliquot, and store the supernatant [24] [26]. Protein concentration should be ~1-2 mg/mL [24]. |

| Tissue Homogenates | Homogenize dissected tissue on ice in an ice-cold extraction buffer with protease inhibitors. Agitate for 2 hours at 4°C. Centrifuge at 13,000-18,000 x g for 20 min at 4°C. Collect, aliquot, and store the supernatant [24] [26]. |

| Serum/Plasma | Collect blood with an anti-coagulant (for plasma) or allow it to clot (for serum). Centrifuge at 1,000-10,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C. Collect, aliquot, and store the supernatant at -80°C [26]. |

| Other Fluids (e.g., Urine) | Centrifuge samples at 1,000-10,000 x g for 2-10 min at 4°C. Collect, aliquot, and store the supernatant [26]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

The workflow for a sandwich ELISA consists of several key stages with intervening wash steps to remove unbound material.

Step 1: Plate Coating (Capture Antibody Immobilization)

- Dilute the capture antibody in a suitable coating buffer (e.g., 0.2 M carbonate/bicarbonate, pH 9.4) to a concentration of 1-10 µg/mL [16] [26].

- Add 50-100 µL of the diluted antibody to each well of a polystyrene microplate.

- Seal the plate and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation or overnight at 4°C [26].

- After incubation, flick out the solution from the wells.

Step 2: Blocking

- Add 200-300 µL of a blocking buffer (e.g., 3-5% BSA in PBS or 5% normal serum) to each well to cover all remaining protein-binding sites [16] [26].

- Incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature.

- Flick out the blocking buffer. Wash the plate three times with wash buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween 20). Between washes, flick the plate over a sink to remove all liquid. Automated plate washers can also be used for uniformity [24] [25].

Step 3: Sample and Antigen Incubation

- Prepare serial dilutions of the antigen standard in the diluent buffer.

- Add prepared samples and standards to the assigned wells. A volume of 50-100 µL is typical.

- Cover the plate and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature (or as optimized) to allow the antigen to bind to the capture antibody [26].

- Flick out the content and wash the plate three times as before [25].

Step 4: Detection Antibody Incubation

- Dilute the enzyme-conjugated detection antibody in diluent buffer.

- Add 50-100 µL of the detection antibody solution to each well.

- Cover the plate and incubate for 1-2 hours at room temperature (or as optimized).

- Flick out the content and wash the plate three times thoroughly to remove any unbound detection antibody [25] [26].

Step 5: Signal Detection

- Prepare the enzyme substrate solution according to the manufacturer's instructions. For HRP, common substrates are TMB (colorimetric) or luminol (chemiluminescent) [16].

- Add 50-100 µL of the substrate solution to each well.

- Incubate the plate in the dark at room temperature for 5-30 minutes, monitoring for color development (for colorimetric assays).

- For colorimetric assays, if required, add an equal volume of stop solution (e.g., 0.16 M sulfuric acid for TMB) to each well to terminate the reaction [16].

Step 6: Plate Reading and Data Analysis

- Read the plate immediately after the reaction is stopped or as per the detection method.

- For colorimetric assays using TMB, read the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader [16].

- The amount of antigen in unknown samples is calculated by interpolating their absorbance values from a standard curve generated using the known concentrations of the standard [24] [25].

Detection Methods and Data Analysis

ELISA detection can be colorimetric, fluorometric, or chemiluminescent, each with distinct advantages. The following diagram illustrates the final detection principle in a colorimetric ELISA.

Table 3: Common ELISA Detection Substrates

| Enzyme | Substrate Type | Example Substrate | Stop Solution | Final Color / Read Wavelength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Colorimetric | 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) | 0.16 M Sulfuric Acid | Yellow / 450 nm [16] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Colorimetric | o-Phenylenediamine (OPD) | 3 M Acid (HCl/H₂SO₄) | Orange / 492 nm [16] |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) | Colorimetric | p-Nitrophenyl Phosphate (pNPP) | 1 M Sodium Hydroxide | Yellow / 410 nm [16] |

For quantification, the optical density (OD) values of the standards are plotted against their known concentrations to generate a standard curve. The concentration of antigen in unknown samples is determined by comparing their OD values to this curve. Data analysis software, often integrated with plate readers, can automatically fit the data (e.g., using a four-parameter logistic (4-PL) curve fit) and calculate sample concentrations [24] [25].

Troubleshooting and Technical Notes

- High Background Signal: Ensure sufficient washing between steps and check the specificity of the antibody pairs. Verify that the blocking agent is effective and that the detection antibody is not cross-reacting [16].

- Low Signal: Check the activity of enzyme conjugates and substrates. Optimize antibody concentrations and incubation times. Ensure samples are not degraded and contain the analyte of interest [26].

- High Well-to-Well Variation: Use multichannel pipettes for consistent reagent dispensing. Ensure plates are from a trusted supplier to avoid plate-to-plate variability [16].

- Matrix Effects: For complex samples like serum, perform a spike-and-recovery experiment to assess whether the sample matrix is interfering with the assay. Diluting the sample or using a matrix-matched standard curve may be necessary [16].

Plate Selection and Coating

The foundation of a robust Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) is the appropriate selection and preparation of the solid phase, which is typically a polystyrene microplate. The choices made at this stage directly influence assay sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [1].

Microplate Selection Criteria

Table 1: Guidelines for Microplate Selection Based on Assay Requirements

| Parameter | Recommended Choice | Rationale and Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Plate Type | ELISA plate (protein-binding) | Designed for high protein-binding capacity (~400 ng/cm²); not tissue culture plates [1] [27]. |

| Well Color | Clear: Colorimetric detectionWhite: Chemiluminescent detectionBlack: Fluorescent detection | Optimizes signal detection and minimizes cross-talk [1] [16]. |

| Binding Capacity | High, with low well-to-well variation | Coefficient of variation (CV) for protein binding should be low (<5% preferred) [1]. |

| Surface | Standard polystyrene | For passive adsorption of proteins via hydrophobic interactions [1]. |

Protocol: Plate Coating and Blocking

Coating via Passive Adsorption

- Coating Buffer: Dilute the capture antibody or antigen to a concentration of 2–10 µg/mL in an alkaline buffer such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4) [1] [16].

- Incubation: Add the coating solution to the wells and incubate for several hours to overnight. incubation temperature can range from 4°C to 37°C [1].

- Storage: Coated plates can be used immediately, or dried and stored at 4°C for later use [1].

Blocking

- Blocking Buffer: After coating, add a blocking buffer containing irrelevant proteins (e.g., 1-5% BSA or casein) or other molecules to all wells [1] [28].

- Incubation: Incubate for 1 to 2 hours at room temperature to cover all unsaturated binding sites on the polystyrene surface, thereby preventing non-specific binding in subsequent steps [1] [24].

- Washing: Perform multiple wash steps with wash buffer (e.g., PBS or Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20) to remove unbound coating and blocking reagents [24].

Standard Curve Preparation and Data Analysis

The standard curve is the cornerstone of quantitative ELISA, enabling the conversion of optical density (OD) readings into precise analyte concentrations [5] [29].

Protocol: Preparing the Standard Curve

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the lyophilized standard according to the kit protocol, often using the provided sample diluent buffer [24].

- Serial Dilution: Perform a serial dilution of the reconstituted standard to create a concentration series. A common approach is a two-fold or three-fold dilution series in the same matrix as the sample to account for matrix effects [5] [30].

- Assay Run: Add the standard concentrations to the plate in duplicate or triplicate, following the same procedure as the unknown samples [5] [29].

- Data Screening: Prior to curve fitting, screen the raw data for anomalies, outliers, and increasing variability with mean spot intensity (heteroskedasticity), which may be minimized with log transformations [30].

Data Analysis and Curve Fitting

Table 2: Common Models for ELISA Standard Curve Fitting

| Model | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear (y = mx + c) | Limited dynamic range; quick analysis. | Simple to compute without specialized software. | Poor fit for sigmoidal data; compresses data at curve ends [5]. |

| Semi-Log (x = log(conc)) | Counteracting compression at lower concentrations. | Often results in a more distributable sigmoidal curve [5]. | May not linearize the entire curve. |

| Log/Log (x & y = log) | Low to medium concentration range. | Provides good linearity for this range [5]. | Loses linearity at the higher end of the range [5]. |

| 4-Parameter Logistic (4PL) | Most sigmoidal ELISA data (assumes symmetry). | Excellent fit for most standard curves; accounts for asymptotes [5] [29]. | Requires curve-fitting software; more complex calculations. |

| 5-Parameter Logistic (5PL) | Asymmetrical sigmoidal data. | Provides the best fit for immunoassays with asymmetry [5]. | Requires sophisticated software and more data points. |

- Calculating Sample Concentration: Average the duplicate or triplicate absorbance readings for each sample. Subtract the average zero standard OD. Find the average absorbance on the standard curve's y-axis, draw a horizontal line to the curve, then a vertical line down to the x-axis to determine the concentration. Multiply by the dilution factor if applicable [5] [29].

- Quality Control: Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for replicates. The CV (standard deviation/mean) should generally be ≤ 20% to ensure precision. High CV can indicate pipetting errors, contamination, or temperature variations [5] [29].

Proper Washing Techniques

Washing is a critical yet often underestimated step that directly governs the signal-to-noise ratio by removing unbound reagents and minimizing non-specific binding [31].

Wash Buffer Composition and Preparation

- Base Buffer: Use phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or Tris-buffered saline (TBS) at a physiological pH (7.2–7.4) to maintain ionic strength and prevent non-specific electrostatic interactions [31].

- Detergent: Include a non-ionic surfactant like TWEEN 20 (Polysorbate 20) at a concentration of 0.01 - 0.1% to reduce surface tension and facilitate the displacement of weakly bound, non-specific proteins [31] [28].

- Purity: Prepare wash buffers using high-purity, deionized water and filter through a 0.22 µm filter to prevent contamination [31].

Protocol: Optimizing the Washing Process

Manual Washing:

- Aspirate the content of the well and dispense wash buffer to fill the wells completely. Invert the plate onto absorbent tissue after each wash, tapping firmly to remove residual fluid [27].

Automated Washer Calibration: The mechanics of automated washing must be precisely controlled [31].

Table 3: Automated Microplate Washer Optimization Parameters

| Parameter | ELISA Recommendation | Rationale and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Dispense Volume | 300 - 350 µL per cycle [31] | Ensures complete exchange of the liquid phase within the well. |

| Number of Cycles | 3 - 6 cycles per wash step [31] | Sufficient for background reduction without risking delamination of bound components. |

| Soak Time | Incorporate a 5-30 second soak between cycles [31] [32] | Helps to dislodge non-specific binding. |

| Residual Volume | < 5 µL is the industry standard target [31] | High residual volume dilutes subsequent reagents, lowering signal and increasing variability. |

| Aspiration Depth | Position probe as close to well bottom as possible without touching [31] | Primary determinant of residual volume. |

| Aspiration Speed | Use a slower speed [31] | Minimizes bubble formation and vacuum stress that can disturb bound material. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for ELISA

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA Plates | Solid phase for immobilization of capture antibody or antigen. | Choose binding capacity, well color, and surface based on assay needs [1] [16]. |

| Coating Buffers | Stabilize the biomolecule during passive adsorption to the plate. | Carbonate/bicarbonate (pH 9.4-9.6) or PBS (pH 7.4); must be protein-free [1] [16]. |

| Blocking Agents | Cover unsaturated binding sites to prevent non-specific antibody binding. | BSA, casein, or gelatin at 1-5%; or normal serum from a non-immunized animal [1] [28] [16]. |

| Wash Buffer | Remove unbound reagents and reduce background. | PBS or TBS with 0.05% Tween 20; pH 7.2-7.4 [31] [28]. |

| Matched Antibody Pairs | For sandwich ELISA: capture and detect the target antigen. | Must recognize different, non-overlapping epitopes [1] [28]. |

| Enzyme Conjugates | Generate a detectable signal. | Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) and Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) are most common [1] [16]. |

| Detection Substrates | Converted by the enzyme conjugate into a measurable product. | TMB (colorimetric/HRP), pNPP (colorimetric/AP), or luminol-based (chemiluminescent/HRP) [16]. |

| Stop Solution | Halt the enzyme-substrate reaction. | Acidic solution (e.g., 0.16M H₂SO₄ for TMB); stabilizes the signal for reading [16]. |

The Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) represents a cornerstone analytical technique in the development and assessment of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). This immunological biochemical assay detects antigen-antibody interactions using enzyme-labelled conjugates and substrates that generate measurable color changes [3]. In the context of biotherapeutic development, ELISA provides a reliable means to quantify antibody concentrations in biological fluids, assess pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles, and evaluate immunogenic responses [3] [33]. The method's specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility make it particularly valuable for determining critical parameters that underlie efficacy and safety assessments throughout the drug discovery pipeline [3] [34].

A thorough understanding of drug metabolism and disposition, enabled by robust bioanalytical methods like ELISA, is essential for accurate assessment of efficacy and safety for biotherapeutic candidates [35]. For therapeutic antibodies, which constitute a rapidly growing class of targeted therapeutics, ELISA-based quantification provides the exposure data necessary to establish PK/pharmacodynamic (PD) relationships, determine safety margins, and project doses from animal studies to humans [34]. This application note details the specific methodologies and experimental considerations for applying ELISA technologies to the evaluation of therapeutic antibody efficacy and pharmacokinetics.

Key Applications of ELISA in Antibody Assessment

Pharmacokinetic Profiling of Therapeutic Antibodies

Pharmacokinetic analysis tracks the temporal dynamics of therapeutic antibody concentration in biological systems, providing critical information about absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties. ELISA formats are particularly valuable for distinguishing between different drug species that may coexist in vivo, especially in the presence of soluble targets or shed receptors [34].

Free vs. Total Drug Measurement: The choice between measuring "free" (unbound) versus "total" (both bound and unbound) antibody concentrations represents a critical consideration in PK assay design [34]. Free antibody concentrations typically reflect the pharmacologically active form required for establishing PK/PD relationships and safety margin calculations [34]. In contrast, total drug measurement may be more relevant for evaluating the dynamic interaction between the drug and its target, as well as assessing overall drug exposure [34]. In situations with minimal circulating target, both measurements often yield equivalent results; however, in the presence of significant amounts of soluble ligand or shed receptor, the assay format dramatically influences the resulting PK profiles and subsequent interpretation [34].

Case Study: Assay Format Impact on PK Profiles: A comparative analysis of anti-CD20 therapeutic antibodies (rituximab, ocrelizumab, and v114) demonstrated how assay format selection significantly influences PK interpretation [34]. When a monoclonal anti-CDR (MAC) assay format was used to quantify ocrelizumab in rheumatoid arthritis patients, the calculated terminal half-life was approximately 8 days, suggesting the drug cleared three times faster than rituximab [34]. However, when a polyclonal anti-CDR (PAC) assay format was applied to the same samples, the half-life extended to 16.7-17.4 days, aligning with expected profiles [34]. This discrepancy underscores how reagent selection and assay design fundamentally affect which drug species are detected and quantified [34].

Table 1: Comparison of ELISA Formats for Therapeutic Antibody PK Assessment

| Assay Format | Target Species | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ELISA | Free drug | Measures pharmacologically active form; minimal reagent requirements | Potential underestimation due to target interference |

| PAC (Polyclonal anti-CDR) Assay | Total drug | Comprehensive detection of various drug forms; less susceptible to format-based discrepancies | May not reflect bioactive concentration |