Engineering Superior Enzymes: Advanced Mutagenesis Strategies for Peak Catalytic Efficiency

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing enzyme catalytic efficiency through mutagenesis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Engineering Superior Enzymes: Advanced Mutagenesis Strategies for Peak Catalytic Efficiency

Abstract

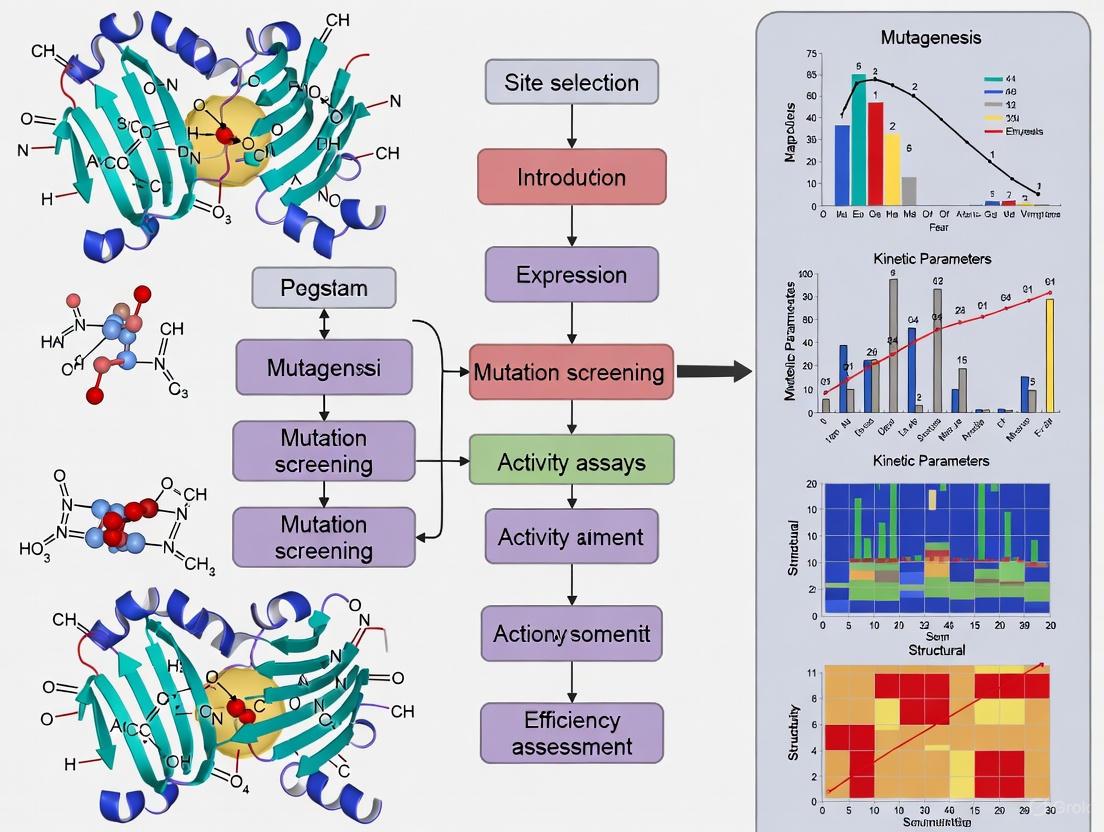

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing enzyme catalytic efficiency through mutagenesis, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of catalytic efficiency, explores established and emerging mutagenesis methodologies like directed evolution and rational design, and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges. The content also details rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of successful engineering outcomes, synthesizing insights from recent high-impact studies to serve as a guide for developing high-performance biocatalysts for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Understanding Catalytic Efficiency: The Blueprint for Enzyme Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is catalytic efficiency and why is it a critical parameter in enzyme engineering? Catalytic efficiency, quantified as the ratio ( k{cat}/KM ), is a measure of how effectively an enzyme converts a substrate into a product. It combines the maximum turnover number (( k{cat} )) and the Michaelis constant (( KM )), which represents the enzyme's affinity for the substrate. A higher ( k{cat}/KM ) value indicates a more efficient enzyme, particularly at low substrate concentrations. This ratio is essential for comparing the performance of engineered enzyme variants and for evaluating the success of mutagenesis strategies aimed at improving enzyme function for industrial and pharmaceutical applications [1] [2].

Q2: In the context of mutagenesis, how can a change in ( k{cat}/KM ) guide our understanding of the mutation's effect? A change in ( k{cat}/KM ) reveals whether a mutation has primarily affected the enzyme's catalytic power (( k{cat} )) or its substrate binding affinity (( KM )).

- An increase in ( k_{cat} ) suggests the mutation has enhanced the rate of the chemical conversion step after substrate binding.

- A decrease in ( K_M ) indicates the mutation has improved the enzyme's affinity for the substrate, meaning it requires a lower substrate concentration to achieve half of its maximum velocity.

Therefore, analyzing the individual changes to ( k{cat} ) and ( KM ) following mutagenesis provides mechanistic insight into how the amino acid substitution influences enzyme function [3] [2].

Q3: What are the common experimental pitfalls when determining ( k{cat} ) and ( KM ), and how can they be avoided? Common pitfalls include:

- Inaccurate Enzyme Concentration: The calculation of ( k{cat} ) (( k{cat} = V{max} / [E]t )) depends on an accurate measurement of the total active enzyme concentration ( [E]t ). An overestimation of ( [E]t ) will lead to an underestimation of ( k_{cat} ) and thus catalytic efficiency.

- Not Measuring Initial Velocity: Kinetic assays must be conducted under initial velocity conditions where product accumulation is minimal and the reaction rate is constant. Using time points beyond this initial linear phase violates the assumptions of the Michaelis-Menten model.

- Insufficient Data Points: Reliable estimation of ( KM ) and ( V{max} ) requires measuring reaction rates across a broad range of substrate concentrations, both below and above the expected ( K_M ) value [2].

Q4: My engineered enzyme shows a higher ( k{cat} ) but also a much higher ( KM ), resulting in a lower overall catalytic efficiency. What could explain this? This is a classic trade-off where a mutation that accelerates the chemical step (higher ( k{cat} )) has simultaneously compromised substrate binding (higher ( KM ) means lower affinity). This often occurs when a mutation in the active site reduces favorable interactions with the substrate's ground state, making it harder for the enzyme to form the initial enzyme-substrate complex. However, if the transition state is stabilized more than the ground state, the net effect can still be a higher ( k_{cat} ). Your mutation may have stabilized the transition state but destabilized the ground state complex, leading to a net decrease in efficiency. Further structural analysis, such as molecular docking, could reveal the specific loss of interactions [4] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Variation in Replicate Kinetic Assays

| Possible Cause | Suggested Solution | Related Reagents/Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent enzyme preparation or quantification. | Standardize protein purification and quantification protocols (e.g., use Bradford assay and SDS-PAGE). Confirm active enzyme concentration via titration. | Spectrophotometer, Bradford Assay Kit, SDS-PAGE Equipment [4] |

| Substrate depletion or product inhibition during the assay. | Ensure that measurements are taken in the initial linear rate phase, using less than 10% substrate conversion. Use a higher enzyme dilution if necessary. | - |

| Improper handling of temperature-sensitive reagents. | Pre-incubate all reagents to the assay temperature before mixing. Use a thermostatted spectrophotometer or microplate reader. | Thermostatted Spectrophotometer [4] |

Problem: Engineered Mutant Shows No Detectable Activity

| Possible Cause | Suggested Solution | Related Reagents/Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation disrupted protein folding, leading to aggregation or degradation. | Analyze protein solubility via centrifugation and SDS-PAGE. Use circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to check secondary structure. | Centrifuge, CD Spectrometer [6] |

| Mutation in a critical catalytic residue. | Perform structural analysis via molecular docking or consult existing catalytic mechanism literature to avoid mutating essential residues. | Molecular Docking Software (AutoDock, Rosetta) [4] [6] |

| The protein is not expressing. | Verify gene sequence and plasmid integrity. Check expression conditions (inductor concentration, temperature, time). | - |

Quantitative Data from Mutagenesis Studies

The table below summarizes key kinetic parameters from a study on site-directed mutagenesis of Oenococcus oeni β-glucosidase, demonstrating how mutations can enhance catalytic efficiency [4].

| Enzyme Variant | Specific Activity (Relative to Wild-Type) | ( K_M ) for p-NPG (mM) | ( k_{cat} ) (s⁻¹) * | ( k{cat}/KM ) (M⁻¹s⁻¹) * | Catalytic Efficiency (Relative to Wild-Type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 1.0 | [Value not provided] | [Value not provided] | [Value not provided] | 1.0 |

| Mutant III (F133K) | 3.8 | Decreased by 18.2% | [Value not provided] | [Value not provided] | ~3.0 (estimated) |

| Mutant IV (N181R) | 4.2 | Decreased by 33.3% | [Value not provided] | [Value not provided] | ~3.4 (estimated) |

Note: The original study [4] reported relative activity and % change in ( K_M ), from which the relative improvement in ( k_{cat}/K_M ) can be inferred, as a decrease in ( K_M ) with an increase in activity suggests a higher ( k_{cat}/K_M ).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining ( k{cat} ) and ( KM ) via a Continuous Enzyme Assay

This protocol is adapted for a β-glucosidase using a chromogenic substrate like p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG) but can be modified for other enzymes [4].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Assay Buffer: Prepare an appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5).

- Substrate Stock Solution: Prepare a high-concentration stock of pNPG in assay buffer. Prepare serial dilutions to create a range of substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0 mM).

- Enzyme Solution: Dilute your purified enzyme (wild-type or mutant) in assay buffer to a concentration that will give a linear signal change over at least 1-2 minutes.

2. Kinetic Measurement:

- For each substrate concentration, add the appropriate volume of substrate solution to a cuvette.

- Place the cuvette in a thermostatted spectrophotometer set to the optimal temperature (e.g., 50°C) and the correct wavelength (e.g., 405 nm for pNP).

- Start the reaction by adding a small, precise volume of enzyme solution. Mix quickly and record the increase in absorbance every 5-10 seconds for 2-3 minutes.

3. Data Analysis:

- For each substrate concentration, calculate the initial velocity (V₀) from the slope of the linear portion of the absorbance vs. time plot.

- Plot V₀ (y-axis) against substrate concentration [S] (x-axis). Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression software to obtain ( V{max} ) and ( KM ).

- Calculate ( k{cat} ) using the formula: ( k{cat} = V{max} / [E]t ), where ( [E]_t ) is the molar concentration of active enzyme in the assay.

- Calculate catalytic efficiency as ( k{cat} / KM ).

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Rational Design of Enzyme Mutants

This protocol outlines a computational and experimental pipeline for enhancing catalytic efficiency through site-directed mutagenesis [4] [6].

Key Steps:

- Identify Key Residues: Use computational tools like alanine scanning to identify amino acids in the catalytic pocket that contribute significantly to substrate binding or transition state stabilization. Residues with a binding energy change (ΔΔG) greater than a certain threshold (e.g., 0.2 kcal/mol) are potential targets for mutagenesis [4].

- Design Mutations: Perform in silico site-directed mutagenesis. Use molecular docking programs (e.g., AutoDock, Rosetta) to dock the substrate into the mutant enzyme's active site and calculate the new binding free energy (ΔG). Select mutations that show a more negative ΔG (indicating stronger binding) or other favorable interactions [4] [6].

- Wet-Lab Validation: Experimentally create the top-predicted mutants using site-directed mutagenesis kits.

- Express and Purify: Express the mutant proteins in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli) and purify them, for example, using affinity chromatography. Verify purity and concentration via SDS-PAGE and protein quantification assays [4].

- Characterize Kinetics: Determine the kinetic parameters (( k{cat} ) and ( KM )) for the wild-type and mutant enzymes as described in Protocol 1. Compare their catalytic efficiencies (( k{cat}/KM )) to evaluate the success of the engineering effort [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Catalytic Efficiency Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking Software (AutoDock, Rosetta) | Predicts the binding orientation and affinity of a substrate within an enzyme's mutant active site. | Used to virtually screen designed mutations by calculating changes in binding free energy (ΔG) before wet-lab experiments [4] [6]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces specific nucleotide changes into a plasmid containing the gene of interest. | Used to create the desired amino acid substitution in the target enzyme gene for expression [4]. |

| Chromogenic Substrate (e.g., pNPG) | A substrate that releases a colored product (e.g., p-nitrophenol) upon enzyme hydrolysis. | Enables continuous, real-time monitoring of enzyme activity in a spectrophotometer for kinetic assays [4]. |

| Affinity Chromatography System (e.g., His-Tag Purification) | Purifies recombinant proteins based on a specific tag fused to the protein. | Used to obtain highly pure samples of wild-type and mutant enzymes for accurate kinetic characterization [4]. |

| Thermostatted Spectrophotometer | Measures light absorbance of a solution while maintaining a constant temperature. | Essential for performing reproducible enzyme kinetic assays at a defined, optimal temperature [4]. |

Troubleshooting Common Michaelis-Menten Experiments

This section addresses frequent challenges researchers encounter when determining enzyme kinetic parameters.

FAQ 1: My reaction velocity versus substrate concentration plot does not yield a clean hyperbolic curve. What could be the cause?

Several factors can lead to non-ideal kinetic data:

- Substrate Inhibition: At high concentrations, the substrate may bind to a non-productive site on the enzyme, causing a decrease in velocity at high

[S][7]. - Enzyme Instability: The enzyme may be denaturing or losing activity during the assay. Verify enzyme stability by measuring velocity over time at a single substrate concentration [6].

- Incorrect pH or Buffer Conditions: The enzyme has an optimal pH, and deviation can alter ionization states of critical active site residues, reducing activity. Always use an appropriate buffer [7].

- Presence of Inhibitors: Contaminants in your substrate or buffer preparation may act as competitive or non-competitive inhibitors [7].

FAQ 2: How can I determine if my estimated Km and Vmax values are reliable?

- Replicate Measurements: Perform experiments in triplicate to calculate standard deviations for your velocity measurements.

- Linear Transformation: Plot your data using a Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot. A straight line suggests the data fits the Michaelis-Menten model, allowing for graphical estimation of Km and Vmax [7]. However, be aware that this method can distort experimental errors.

- Statistical Fitting: Use non-linear regression software to fit the hyperbolic function

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])directly to your untransformed data. This is the most accurate method [8].

FAQ 3: I have engineered a mutant enzyme and want to assess its catalytic efficiency. Which parameter should I prioritize?

The specificity constant, kcat/Km, is the best measure of catalytic efficiency [8] [9].

kcat/Kmis a second-order rate constant that describes the enzyme's efficiency at low substrate concentrations.- An increase in

kcat/Kmafter mutagenesis indicates a successful improvement, whether it stems from a higher turnover number (kcat) or a lower Michaelis constant (Km, indicating higher affinity) [8] [6].

Quantitative Data on Enzyme Kinetics and Mutagenesis

The following tables summarize key kinetic parameters for natural enzymes and the results of recent mutagenesis studies.

Table 1: Example Michaelis-Menten Parameters for Representative Enzymes [8]

| Enzyme | Km (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ |

| tRNA synthetase | 9.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 7.6 | 8.4 × 10³ |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ |

Table 2: Recent Examples of Catalytic Efficiency Enhancement via Mutagenesis

| Enzyme (Variant) | Mutation | Ligand | Change in Binding Free Energy (ΔΔG) | Efficiency Gain | Primary Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1FCE | Pro174Ala | Avicel | - | 23.3% | Computational Mutagenesis, MD Simulations | [6] |

| 1AVA | Asp126Arg | Starch | - | 45.6% | Computational Mutagenesis, MD Simulations | [6] |

| Bacterial Rubisco (Gallionellaceae) | Three mutations near active site | CO₂/O₂ | - | 25% (in carboxylation efficiency) | Directed Evolution (MutaT7) | [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Analysis and Mutagenesis

Protocol 1: Determining Km and Vmax via Initial Rate Measurements

This is a foundational protocol for characterizing enzyme kinetics [11] [12].

- Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of your substrate and a fixed, dilute concentration of your purified enzyme in an appropriate reaction buffer.

- Reaction Series: Set up a series of reactions with identical enzyme concentration and varying substrate concentrations. The range should span from well below to well above the expected Km.

- Initial Rate Measurement: For each reaction, initiate the reaction by adding enzyme and immediately measure the initial velocity (V₀), the linear rate of product formation before more than ~5% of the substrate has been consumed. This can be done by monitoring a change in absorbance, fluorescence, or other signal related to product formation over a short time period (e.g., 30-60 seconds) [12].

- Data Analysis: Plot the initial velocity (V₀) against the substrate concentration

[S]. Use non-linear regression software to fit the Michaelis-Menten equationv = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])to the data points, yielding values for Km and Vmax [8].

Protocol 2: A Computational Workflow for Guiding Mutagenesis

This protocol outlines a modern computational approach to identify promising mutation sites for improving substrate binding affinity and catalytic efficiency [6].

- Structure Retrieval: Obtain the high-resolution 3D crystal structure of your target enzyme from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Molecular Docking: Use molecular docking software (e.g., CB-Dock 2) to simulate the binding of the substrate to the enzyme's active site. Calculate the binding free energy (ΔG) of the wild-type complex.

- In silico Mutagenesis: Use a tool like PyMOL or FoldX to introduce specific amino acid substitutions at sites near the active site or substrate-binding channel.

- Re-docking and Scoring: Re-dock the substrate to the mutated enzyme model and calculate the new binding free energy. An improvement (more negative ΔG) suggests a mutation that may enhance substrate affinity (lower Km) [6].

- Stability Validation: Subject the top mutant models to further analysis, such as Ramachandran plotting (to confirm structural integrity) and Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MDS) to verify the stability of the mutant structure over time [6].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Computational Mutagenesis Workflow

Diagram 2: Michaelis-Menten Reaction Scheme

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use in Mutagenesis Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking Software (CB-Dock 2, AutoDock) | Predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a substrate molecule to an enzyme. | Calculating the change in binding free energy (ΔΔG) for mutant enzymes [6]. |

| Directed Evolution Platform (MutaT7) | A continuous mutagenesis technique in live cells that rapidly generates and screens large mutant libraries. | Identifying mutations that improve catalytic efficiency (e.g., in Rubisco) under selective pressure [10]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (WebGRO, CABS-Flex 2.0) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess conformational stability. | Validating that a beneficial mutation does not compromise the structural integrity of the enzyme [6]. |

| AI Prediction Tools (CatPred, ECEP) | Deep learning frameworks that predict kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) from enzyme sequence and structure. | Providing initial estimates of kinetic parameters for uncharacterized enzymes or mutants to guide experimental design [13] [14]. |

| Stability Analysis Tools (Aggrescan4D, FoldX) | Predicts the change in protein folding stability (ΔΔG) and aggregation propensity upon mutation. | Screening out mutations that are predicted to destabilize the enzyme before conducting expensive experiments [6]. |

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What fundamental properties do all enzymes, including engineered mutants, share? Enzymes are biological catalysts characterized by two fundamental properties: they increase the rate of chemical reactions without themselves being consumed or permanently altered, and they increase reaction rates without altering the chemical equilibrium between reactants and products [15]. This means that while mutagenesis can enhance the rate of a reaction, it does not change the reaction's final equilibrium [15] [16].

Q2: How does an enzyme actually lower the activation energy of a reaction? Enzymes lower the activation energy (Ea) by providing an alternative pathway for the reaction [7]. They achieve this by binding their substrates to form an enzyme-substrate complex (ES) and utilizing several mechanisms that favor the formation of the reaction's transition state [15]. These mechanisms include stabilizing the transition state, distorting the substrate to more closely resemble it, and participating directly in the catalytic process via amino acid side chains [15].

Q3: We want to improve an enzyme's catalytic efficiency via mutagenesis. What is a key parameter to measure? The Michaelis constant (Km) is a key parameter. It represents the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax [7]. A lower Km value indicates a higher affinity for the substrate, as the enzyme can achieve half its maximum rate at a lower substrate concentration. This is a common target for mutagenesis studies aimed at enhancing efficiency [7].

Q4: Can enzyme mutagenesis change the equilibrium of a reaction (Keq)? No. A fundamental truth of enzyme catalysis is that enzymes, including mutated variants, do not change the equilibrium constant (Keq) for a reaction [16]. The Keq depends only on the difference in energy level between the reactants and products. Enzymes only accelerate the rate at which equilibrium is reached [15] [16].

Q5: What modern computational tools can help plan a mutagenesis experiment? The field has shifted to integrated, AI-accelerated design cycles. Tools like AlphaFold2 and ESM-Fold can predict protein structures, while FoldX, Rosetta, and DeepDDG can compute the change in free energy (ΔΔG) for thousands of mutants to predict stability. Tools like AutoDock-Mut can specifically quantify changes in ligand-binding affinity [6].

Q6: What is the Induced Fit model, and why is it important for catalysis? The Induced Fit model states that the active site is not a rigid, perfect fit for the substrate. Instead, when the substrate binds, the enzyme undergoes a conformational change that tightens the fit around the substrate [15] [7]. This change helps distort the substrate into the transition state, a mechanism that can be enhanced through targeted mutagenesis [15].

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Problem: Low Catalytic Efficiency in Engineered Enzyme

Symptoms: Low reaction rate (V0) and high Km, even after mutagenesis.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Investigation Step | Technique/Tool | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check binding affinity | Molecular Docking (e.g., AutoDock, CB-DOCK 2) | Improved binding free energy (ΔG) indicates successful enhancement. A more negative ΔG signifies stronger binding [6]. |

| 2. Assess structural integrity | Ramachandran Plot Analysis | Minimal deviation (e.g., ≤ 0.6%) in backbone dihedral angles confirms the mutation did not disrupt the overall protein fold [6]. |

| 3. Analyze local flexibility | Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) | Peak shifts of 0.2–0.5 Å at key residues can indicate enhanced flexibility and adaptability at the active site, facilitating catalysis [6]. |

| 4. Verify global stability | Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MDS) / Radius of Gyration | Stable RMSD (e.g., 0.25-0.26 nm) and constant radius of gyration over a 50 ns simulation indicate the mutant is stable and does not unfold [6]. |

### Problem: Engineered Enzyme is Less Stable

Symptoms: Protein aggregation, precipitation, or low expression yield.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Investigation Step | Technique/Tool | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Predict thermostability | Thermodynamic Analysis (Melting Temperature, Tm) | Small Tm variations (e.g., ± 1.3°C) suggest the mutation did not significantly destabilize the protein. Large drops are a red flag [6]. |

| 2. Check aggregation propensity | Aggrescan4D (pH-dependent) | Low aggregation score across pH 5.0–8.5 confirms the enzyme remains soluble and stable under a broad range of industrially relevant conditions [6]. |

### Problem: Poor Substrate Specificity

Symptoms: Enzyme acts on unintended, promiscuous substrates.

Investigation and Resolution:

| Investigation Step | Technique/Tool | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Predict specificity profile | Machine Learning Models (e.g., EZSpecificity) [17] | The model can accurately identify the single potential reactive substrate from a pool (e.g., 91.7% accuracy), guiding mutagenesis for altered specificity [17]. |

| 2. Analyze active site interactions | Molecular Docking & MD Simulations | Visualizing the enzyme-substrate complex can reveal if mutations have created unfavorable interactions or failed to enforce precise substrate positioning [15] [6]. |

## Quantitative Data for Enzyme Enhancement

The following table summarizes experimental data from a recent computational mutagenesis study, providing benchmarks for successful enzyme engineering.

Table 1: Benchmarking Data from Computational Mutagenesis for Enhanced Enzyme Efficiency [6]

| Enzyme Mutant | Ligand | Binding Free Energy (ΔG) Wild-type | Binding Free Energy (ΔG) Mutant | % Improvement in ΔG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1FCE_Thr226Leu | Cellulose | -7.2160 kcal/mol | -8.1532 kcal/mol | +13.0% |

| 1FCE_Pro174Ala | AVICEL | -7.2160 kcal/mol | -8.8992 kcal/mol | +23.3% |

| 1AVA_Asp126Arg | Starch | -5.2035 kcal/mol | -7.5767 kcal/mol | +45.6% |

Table 2: Stability Metrics of Engineered Enzyme Mutants [6]

| Protein | Melting Temp (Tm) Wild-type | Melting Temp (Tm) Mutant | RMSD at 50 ns MD Simulation | Key RMSF Shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1FCE | 74.7 °C | 75.1 °C | 0.26 nm | 0.2–0.5 Å at catalytic residues |

| 1AVA | 67.9 °C | 67.8 °C | Stable, similar to wild-type | 0.2–0.5 Å at catalytic residues |

| 6M4K | 62.4 °C | 62.1 °C | Stable, similar to wild-type | 0.2–0.5 Å at catalytic residues |

## Experimental Protocols

### Protocol 1: In-Silico Workflow for Mutagenesis and Analysis

This integrated computational protocol allows for the comprehensive characterization of enzyme mutants before moving to the lab [6].

### Protocol 2: P3a Site-Specific and Cassette Mutagenesis

This wet-lab protocol describes a modern, highly efficient method for creating precise DNA mutations for protein engineering [18].

Principle: Uses specially designed primers with 3'-overhangs combined with high-fidelity enzymes (Q5 and SuperFi II DNA polymerases) to achieve nearly 100% success in introducing point mutations, large deletions, and insertions [18].

Procedure:

- Primer Design: Design a pair of primers that are complementary to the target DNA sequence. The primers must contain the desired mutation (e.g., single nucleotide change) and have 3'-overhanging sequences.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Set up the PCR reaction using the high-fidelity DNA polymerases (Q5 or SuperFi II) and the designed primers. The high-fidelity enzymes ensure accurate DNA replication with minimal errors.

- Digestion: Following PCR, treat the product with the DpnI restriction enzyme. DpnI specifically cleaves methylated and hemi-methylated DNA, which is the template plasmid. This digests the original, non-mutated DNA template.

- Transformation: Transform the digested PCR product into competent E. coli cells.

- Screening and Sequencing: Screen colonies and sequence the DNA to confirm the introduction of the correct mutation. The high efficiency of the method often means a very high proportion of colonies contain the desired mutant.

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Modern Enzyme Engineering Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases (Q5, SuperFi II) | Essential for accurate PCR amplification in mutagenesis protocols like P3a, minimizing errors during DNA synthesis [18]. |

| P3a Mutagenesis Primers | Specially designed primers with 3'-overhangs that enable highly efficient and precise site-specific and cassette mutagenesis [18]. |

| Molecular Docking Software (CB-DOCK 2, AutoDock) | Predicts the binding orientation and affinity (ΔG) of a substrate to an enzyme's active site, crucial for virtual screening of mutants [6]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (WebGRO, CABS-Flex 2.0, OpenMM) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess the stability, flexibility, and dynamics of enzyme mutants [6]. |

| Structure Prediction Tools (AlphaFold2, OmegaFold, ESM-Fold) | Generates high-accuracy 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences, which is vital when experimental structures are unavailable [6]. |

| ΔΔG Prediction Tools (FoldX 5.0, Rosetta, DeepDDG, ThermoNet2) | Machine learning-powered tools that calculate the change in free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation, predicting its effect on protein stability [6]. |

| Aggregation Prediction Tool (Aggrescan4D) | Predicts the pH-dependent aggregation propensity of protein sequences, helping to engineer mutants with better solubility and stability for industrial applications [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do mutations that improve my enzyme's solubility often disrupt its catalytic activity? This is a common trade-off in enzyme engineering. Many solubility-enhancing mutations decrease specific activity because they can introduce changes that subtly alter the precise geometry of the active site or affect dynamics crucial for catalysis. The tendency for a mutation to disrupt activity is correlated with its distance from the catalytic active site and its evolutionary conservation. Mutations far from the active site and those that align with evolutionary consensus are more likely to improve solubility without sacrificing function [19].

Q2: What computational strategies can I use to simultaneously improve an enzyme's thermostability and catalytic efficiency? A semi-rational design workflow combining multi-strategy computational screening with single-site saturation mutagenesis has been successfully applied to enzymes like glucose oxidase. The approach uses two parallel strategies:

- Strategy I for Catalytic Efficiency: Integrates molecular docking, co-evolutionary analysis, and consensus residue identification.

- Strategy II for Thermostability: Combines B-factor analysis, solvent-accessible surface area, conservation analysis, and FoldX free energy prediction. Mutant libraries constructed from the identified sites are then subjected to high-throughput screening and combinatorial optimization to obtain high-performance variants [20] [21].

Q3: Are there high-throughput experimental methods to gauge protein solubility for my enzyme engineering projects? Yes, deep mutational scanning can be used to assess solubility. Two common methods are:

- Yeast Surface Display (YSD): A protein is fused to a surface display tag; proper folding and solubility are assessed via binding to a fluorescently conjugated antibody and measured by FACS.

- Tat-Selection: A protein is fused to a periplasmic export signal; its successful translocation (which requires a folded state) is selected for via survival on antibiotic plates [19].

Q4: What is a key advantage of using a fully computational workflow for designing de novo enzymes? A primary advantage is the potential to bypass the need for intensive, laborious experimental optimization through mutant-library screening. Advanced computational pipelines can now design highly efficient, stable, and novel enzymes directly, achieving catalytic parameters that rival natural enzymes without relying on high-throughput screening of random mutants [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Protein Solubility

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Protein aggregation | Hydrophobic residues on protein surface. | Use site-directed mutagenesis to replace surface hydrophobic residues with hydrophilic ones [23]. |

| Unfavorable buffer conditions | Incorrect pH or ionic strength leading to precipitation. | Optimize buffer pH to be near the protein's isoelectric point. Adjust ionic strength by adding salts like NaCl to shield electrostatic interactions [23]. |

| Temperature instability | High temperatures causing denaturation and aggregation. | Perform expression and purification at lower temperatures [23]. |

| Challenging expression in a host system | Lack of proper post-translational modifications or folding machinery. | Switch the expression host (e.g., from bacterial to yeast, insect, or mammalian systems) [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Using Yeast Surface Display to Identify Solubility-Enhancing Mutations

- Library Construction: Create a comprehensive single-site saturation mutagenesis library of your target enzyme.

- Yeast Transformation: Fuse the mutant library in-frame with a C-terminal epitope tag and an N-terminal Aga2p domain for surface display in yeast.

- Display and Staining: Incubate the yeast cells with a fluorescently conjugated antibody that binds the C-terminal epitope tag.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Sort the population to collect the top 5% of cells with the highest fluorescence intensity, indicating high surface expression and, by proxy, good solubility.

- Deep Sequencing: Sequence the sorted population and the initial library to calculate enrichment ratios and assign a solubility score for each mutation [19].

Issue 2: Poor Thermostability

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Marginal native stability | The wild-type enzyme is only marginally stable, making it susceptible to unfolding at moderate temperatures. | Implement a "back-to-consensus" strategy, mutating residues to the most common amino acid found in the enzyme's protein family to improve stability [19]. |

| Local flexibility in key regions | High B-factor values (indicating flexibility) in regions critical for stability. | Use computational tools (B-factor analysis, FoldX) to identify flexible residues and design stabilizing mutations (e.g., introducing prolines, salt bridges) [20] [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Combining Computational Strategies for Stability and Efficiency This protocol outlines the synergistic approach used to engineer glucose oxidase [20] [21].

- Site Identification:

- Run Strategy I (molecular docking, co-evolution, consensus) to find sites for improving catalytic efficiency.

- Run Strategy II (B-factor, SASA, conservation, FoldX) to find sites for improving thermostability.

- Library Construction: Perform single-site saturation mutagenesis at all identified positions.

- High-Throughput Screening: Screen the mutant libraries for both activity (e.g., using a colorimetric assay) and thermal stability (e.g., measuring half-life at elevated temperatures or melting temperature (T_m)).

- Combinatorial Optimization: Combine beneficial single-point mutations into multi-site variants.

- Validation: Express and purify the combinatorial mutants to characterize specific activity, kinetic parameters ((k{cat}), (KM)), and half-life, comparing them to the wild-type enzyme.

Issue 3: Insufficient Catalytic Efficiency

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal active site geometry | The catalytic residues are not positioned optimally for the transition state. | Use a computational workflow that allows extensive backbone and sequence sampling to precisely position the catalytic theozyme [22]. |

| Trade-offs with solubility | Active site mutations that enhance activity may compromise folding or stability. | Use hybrid classification models that predict mutations enhancing solubility without disrupting fitness, or focus on mutations oversampled in evolutionary history [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Yeast Surface Display (YSD) System | High-throughput platform to screen for protein solubility and stability. It leverages the endoplasmic reticulum quality control in yeast [19]. |

| Tat-Selection System | A genetic selection in E. coli based on the export of folded proteins into the periplasm, used to identify soluble variants [19]. |

| FoldX Software | A computational tool for the rapid evaluation of the effect of mutations on protein stability, folding, and dynamics [20] [21]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | A comprehensive modeling suite for de novo protein design and enzyme redesign, enabling atomistic modeling of active sites [22]. |

| PROSS (Protein Repair One Stop Shop) | A computational design server used to stabilize a given protein conformation based on evolutionary conservation [22]. |

| FuncLib | A computational method that focuses on designing functionally diverse protein sequences by restricting mutations to those found in natural homologs, useful for active site optimization [22]. |

Experimental Workflows in Enzyme Optimization

The following diagrams, generated using the DOT language, illustrate key workflows and relationships in enzyme optimization.

Diagram 1: A semi-rational design workflow for optimizing enzyme catalytic efficiency and thermal stability [20] [21].

Diagram 2: High-throughput experimental workflow for identifying solubility-enhancing mutations [19].

Diagram 3: Logical relationships and common trade-offs between key enzyme properties [19].

The Role of Active Site Architecture and Substrate Binding

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I engineer an enzyme to function efficiently at non-physiological pH, such as alkaline conditions? Current research demonstrates that a combination of rational design and directed evolution is highly effective. The core strategy involves reprogramming key catalytic residues to shift the enzyme's proton transfer mechanism. For instance, substituting a conserved catalytic glutamate (with a lower pKa) with a tyrosine (with a higher pKa) can fundamentally alter pH dependence. While this initial mutation (e.g., E166Y in TEM β-lactamase) often severely impairs activity, subsequent directed evolution can restore and enhance function through compensatory mutations. One optimized variant, YR5-2, exhibited a shift in optimal pH by over 3 units and achieved a kcat of 870 s–1 at pH 10.0, a performance comparable to the wild-type enzyme at its optimal pH [24].

Q2: Beyond the active site, what role do distal mutations play in enhancing catalysis? Mutations far from the active site (distal or "shell" mutations) play a crucial role in facilitating the complete catalytic cycle. While active-site ("core") mutations typically pre-organize the catalytic residues for the chemical transformation step, distal mutations enhance catalysis by improving substrate binding and product release. They achieve this by tuning structural dynamics, such as widening the active-site entrance or reorganizing surface loops, which helps reduce energy barriers for these steps. Incorporating distal mutations alongside active-site improvements is often key to achieving optimal catalytic efficiency [25].

Q3: What computational tools are available for predicting the effect of mutations on enzyme efficiency? The computational mutagenesis landscape has advanced significantly, now featuring integrated, AI-accelerated design cycles. Key tools and workflows include:

- Structure Prediction: AlphaFold2-Multimer or ESM-Fold for near-experimental-quality structures.

- Stability & Binding Energy Calculation: FoldX 5.0, Rosetta, DeepDDG, and ThermoNet2 to compute changes in folding free energy (ΔΔG) and ligand-binding affinity.

- pKa Modulation Analysis: PROPKA to quantify shifts in the pKa of catalytic residues.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Tools like OpenMM and WebGRO to verify stability and conformational dynamics. These tools can systematically scan active-site regions to identify mutations that improve substrate-binding affinity and thermostability without compromising structural integrity [6].

Q4: My engineered enzyme has high catalytic activity but is unstable under process conditions. What stabilization strategies can I use? Enzyme immobilization is a key strategy to enhance stability and enable recyclability. The table below summarizes advanced immobilization techniques [26]:

| Strategy | Description | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Carrier-Free (CLEAs) | Cross-linking of enzyme aggregates into insoluble particles. | High enzyme loading, cost-effective, no solid support needed. |

| Magnetic CLEAs (m-CLEAs) | CLEAs formed in the presence of functionalized magnetic particles. | Easy recovery via magnet, simplifies downstream processing. |

| Combi-CLEAs | Co-immobilization of two or more enzymes in a single particle. | Minimizes diffusion of intermediates in multi-step reaction cascades. |

| Genetic Fusion Tags | Enzyme fused to a binding module (e.g., a cellulose-binding domain). | Precise, uniform orientation on a support; strong binding. |

Q5: How can I accurately determine enzyme inhibition constants with higher efficiency? Traditional methods for estimating inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) require extensive data from multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations. A novel approach, termed the "IC50-Based Optimal Approach" (50-BOA), dramatically streamlines this process. This method demonstrates that precise and accurate estimation for all inhibition types (competitive, uncompetitive, and mixed) is possible using initial velocity data from a single inhibitor concentration that is greater than the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). This can reduce the number of required experiments by over 75% while improving estimation precision [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Engineered enzyme shows excellent kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) in assays but performs poorly in actual industrial processes.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Susceptibility to Process Conditions | Test stability in the presence of organic solvents, at operational temperature, and under shear stress. | Implement an immobilization strategy (see table above) to enhance operational stability [26]. |

| Inhibition by Substrate or Product | Measure reaction velocity at different starting substrate and accumulating product concentrations. | Engineer the enzyme to reduce inhibitor affinity or design a continuous process to remove products [27]. |

| Inefficient Catalytic Cycle | Perform pre-steady-state kinetics to determine if substrate binding or product release is the rate-limiting step. | Use directed evolution to introduce distal mutations that widen the active site or improve loop dynamics, facilitating substrate and product flow [25]. |

Problem: Rational design of a key catalytic residue successfully shifted pH optimum but resulted in a dramatic loss of activity.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Positioning of New Residue | Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze the geometry and interactions of the mutated residue in the active site. | Employ directed evolution to identify second-shell mutations that optimally reposition the catalytic residue and restore the active site architecture [24]. |

| Disrupted Proton Relay Network | Calculate the pKa of all acidic/basic residues in the active site using computational tools like PROPKA. | Re-engineer the hydrogen-bonding network through further site-saturation mutagenesis of surrounding residues to re-establish efficient proton transfer [6] [28]. |

| Reduced Transition State Stabilization | Perform molecular docking with a transition state analog to compare binding free energy (ΔG) between wild-type and mutant enzymes. | Introduce compensatory mutations that form new electrostatic interactions or hydrogen bonds to better stabilize the transition state [6]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Integrated Strategy for pH Optimum Shifting via Catalytic Residue Reprogramming [24]

- Rational Design: Identify the conserved catalytic general base/residue (e.g., Glu166 in TEM β-lactamase). Substitute it with a residue possessing a higher intrinsic pKa (e.g., Tyrosine) using site-directed mutagenesis to create a low-activity intermediate variant.

- Directed Evolution:

- Library Construction: Subject the gene encoding the designed variant to iterative rounds of random mutagenesis (e.g., error-prone PCR).

- Screening: Screen libraries for restored growth or activity under selective pressure (e.g., high antibiotic concentration for β-lactamases) at the desired pH.

- Characterization:

- Steady-State Kinetics: Purify evolved hits and determine kcat and KM across a broad pH range (e.g., pH 7.0-11.0) to quantify the shift in pH-activity profile.

- Mechanistic Validation: Use molecular dynamics simulations and analyze revertant mutants (e.g., Y166E) to confirm the new catalytic mechanism (e.g., phenolate-mediated proton transfer).

Quantitative Data on Engineered Enzyme Performance [24] [6]

| Enzyme / Variant | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Optimal pH | Key Mutations & Functional Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEM β-lactamase (WT) | Benchmark at pH ~7 | ~7.0 | Glu166 as general base (carboxylate-mediated catalysis). |

| TEM β-lactamase (YR5-2) | kcat of 870 s⁻¹ at pH 10.0 | ~10.0 (>3-unit shift) | E166Y + compensatory mutations; Tyr166 as general base (phenolate-mediated catalysis) [24]. |

| Cellulase (1FCE_Thr226Leu) | Binding free energy (ΔG) improved by 13.0% | - | Enhanced substrate (Cellulose) binding affinity via improved dynamics [6]. |

| Cellulase (1FCE_Pro174Ala) | Binding free energy (ΔG) improved by 23.3% | - | Enhanced substrate (Avicel) binding affinity [6]. |

| Amylase (1AVA_Asp126Arg) | Binding free energy (ΔG) improved by 45.6% | - | Enhanced substrate (Starch) binding affinity; stable across pH 5.0-8.5 [6]. |

Protocol: Computational Workflow for Enhancing Enzyme-Substrate Binding [6]

- Structure Retrieval: Obtain 3D crystal structures of the target enzyme (e.g., from PDB) and its substrate (e.g., from PubChem).

- Molecular Docking: Perform docking simulations (e.g., using CB-Dock 2) to analyze wild-type enzyme-substrate interactions and binding free energy (ΔG).

- In-silico Mutagenesis: Use software like PyMOL to model specific point mutations (e.g., Thr226Leu).

- Binding Analysis: Re-dock the substrate to the mutant model and calculate the new ΔG to predict improvements.

- Stability Validation: Use tools like CABS-flex 2.0 or WebGRO for molecular dynamics simulations to ensure mutations do not destabilize the enzyme (check RMSD, RMSF). Analyze results with Ramachandran plots and aggregation predictors like Aggrescan4D.

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| TEM β-lactamase (plasmid) | Model enzyme system for studying catalytic mechanisms and engineering pH resilience [24]. |

| Transition State Analogue (e.g., 6NBT) | Used in crystallography and binding studies to mimic the reaction's transition state and analyze active site organization [25]. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Bifunctional reagent used to create Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) for immobilization [26]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) | Functionalized solid support for creating magnetic CLEAs (m-CLEAs), enabling easy biocatalyst recovery with a magnet [26]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., OpenMM, WebGRO) | Simulates enzyme motion over time to study the effects of mutations on structural dynamics, stability, and substrate binding [6] [25]. |

| pKa Prediction Tool (e.g., PROPKA) | Computes the pKa values of ionizable residues in protein structures, critical for designing pH-dependent catalytic mechanisms [6]. |

Mutagenesis in Action: From Directed Evolution to AI-Driven Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using directed evolution over rational design for enhancing enzyme catalytic efficiency?

Directed evolution is a powerful, forward-engineering process that harnesses the principles of Darwinian evolution—iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection—within a laboratory setting to tailor proteins for specific applications [29]. Its key strategic advantage is the capacity to deliver robust solutions without requiring detailed a priori knowledge of a protein's three-dimensional structure or its catalytic mechanism [29]. This allows it to bypass the inherent limitations of rational design, which relies on a predictive understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships that is often incomplete [29]. By exploring vast sequence landscapes through mutation and functional screening, directed evolution frequently uncovers non-intuitive and highly effective solutions that would not be predicted by computational models or human intuition [29].

FAQ 2: When should I use random mutagenesis versus focused/semi-rational approaches?

The choice depends on your starting information and goals. Random mutagenesis techniques, like error-prone PCR (epPCR), are ideal when you have no structural information or pre-existing knowledge of beneficial mutation sites [29]. epPCR introduces mutations across the entire gene, typically aiming for 1–5 base mutations per kilobase [29]. In contrast, focused/semi-rational mutagenesis, such as Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM), is highly effective when you have already identified key "hotspot" residues from a prior round of random mutagenesis or from a structural model [30]. SSM comprehensively explores all 19 possible amino acids at a targeted codon, allowing for a deep, unbiased interrogation of a residue's role [31]. A robust strategy often involves using these methods sequentially [31].

FAQ 3: Why might my evolved enzyme library show no improved variants, and how can I troubleshoot this?

A lack of improved variants is often due to issues with library quality or the screening method. Here are common problems and solutions:

| Problem Area | Common Issues | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Library Diversity | • Mutation rate too low/high• epPCR amino acid bias (accesses only 5-6 of 19 possible alternatives) [29]• Low library size | • Tune epPCR (e.g., Mn²⁺ concentration) [29]• Use complementary methods (e.g., Gene Shuffling) [29]• Use TRIM synthesis to avoid out-of-frame mutations [31] |

| Screening Method | • Assay not detecting desired property• Low throughput misses rare variants• "You get what you screen for" [29] | • Ensure screen directly links genotype to phenotype [29]• Match throughput to library size (10⁶-10⁸ for selections; 10⁴-10⁶ for screens) [32]• Design a selective pressure that directly correlates with the desired trait [33] |

FAQ 4: What are the typical costs and timelines for a directed evolution project?

Costs are highly project-dependent but can be estimated based on the diversification strategy [31]. For a 300 amino acid protein, saturating all positions with pooled single substitution variants costs approximately $30,000 [31]. Site-saturation at individual positions ranges from $100-$150 per site for pooled variants to $800-$1,200 per site for variants delivered as single constructs [31]. Turnaround times for gene libraries are typically 4-6 weeks, while cloned libraries can take up to 8 weeks [31].

FAQ 5: Can directed evolution improve properties linked to residues far from the active site?

Yes, absolutely. A common misconception is that only active-site mutations enhance catalysis. However, distal mutations (far from the active site) play critical roles by facilitating other aspects of the catalytic cycle [34]. Research on de novo Kemp eliminases reveals that while active-site mutations create preorganized sites for the chemical transformation itself, distal mutations enhance catalysis by tuning structural dynamics to widen the active-site entrance and reorganize surface loops [34]. This can significantly improve substrate binding and product release, demonstrating that a well-organized active site, though necessary, is not sufficient for optimal catalysis [34].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Hurdles

Problem 1: Low Library Diversity or Quality

- Challenge: The generated mutant library lacks sufficient diversity or contains a high percentage of non-functional variants.

- Solution: Implement a combined approach of Segmental Error-prone PCR (SEP) and Directed DNA Shuffling (DDS) [35]. This method minimizes negative mutations, reduces revertant mutations, and facilitates the integration of positive mutations more effectively than traditional epPCR or DNA shuffling alone [35].

- Protocol Outline:

- SEP: Divide your target gene (e.g., 16bgl for β-glucosidase) into segments. Perform independent error-prone PCR on each segment to generate mutations [35].

- Assembly PCR: Use the mutated segments as templates in an assembly PCR to reconstitute the full-length gene [35].

- DDS: Mix the assembled PCR products with a linearized yeast expression vector (e.g., pYAT22). Co-transform the mixture into S. cerevisiae for in vivo recombination and assembly [35].

- Library Validation: Isolate the plasmid library from yeast and transform into E. coli for amplification and sequencing to validate diversity [35].

- Protocol Outline:

Problem 2: Host-System Toxicity or Poor Expression

- Challenge: The target enzyme (especially from fungi) is toxic to the expression host, poorly expressed, or misfolded.

- Solution: Choose an appropriate expression host based on your protein's origin and requirements [35].

- E. coli: Preferred for prokaryotic proteins due to rapid growth and ease of manipulation. However, it can struggle with soluble, correctly folded fungal enzymes [35].

- S. cerevisiae (Baker's Yeast): An excellent choice for constitutive secretory expression, offering high recombination rates and post-translational modification capabilities. Its high homologous recombination efficiency is ideal for in vivo assembly of mutant libraries [35].

- P. pastoris: Widely used for overexpression and has glycosylation capabilities, though genetic engineering can be more challenging [35].

Problem 3: Identifying Synergistic Mutations

- Challenge: Beneficial mutations identified in early rounds may have synergistic effects that are missed when only combining top hits.

- Solution: After an initial round of epPCR to identify beneficial single mutations, use DNA Shuffling (or Family Shuffling for homologous genes) to recombine those mutations [29]. This mimics natural sexual recombination, bringing together beneficial mutations from multiple parent genes into single, improved offspring and can uncover synergistic effects [29]. Be aware that neutral mutations, which might be synergistic, are often excluded from combinatorial libraries, a limitation no method fully solves [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Directed Evolution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) Kit | Introduces random point mutations across the gene [29]. | Look for kits that allow tuning of mutation rates (e.g., via Mn²⁺). Beware of inherent amino acid bias [29]. |

| S. cerevisiae (e.g., strain EBY100) | Eukaryotic host for expression and in vivo assembly of libraries via homologous recombination [35]. | High recombination efficiency is key for complex library assembly. Enables secretory expression. |

| Yeast Expression Vector (e.g., pYAT22) | Shuttle vector for cloning and expression in yeast and E. coli [35]. | Should contain constitutive promoters (e.g., TEF1), secretion signals (e.g., α-factor), and selection markers (e.g., ura3) [35]. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) Library | Generates all 19 possible amino acid substitutions at a targeted residue [30]. | Use to exhaustively explore "hotspot" positions. TRIM-based synthesis avoids out-of-frame mutations [31]. |

| Microtiter Plates (96- or 384-well) | High-throughput screening of individual library variants [32]. | Essential for colorimetric or fluorometric assays to quantify activity of thousands of clones. |

| Transition-State Analogue (e.g., 6NBT) | Used in structural studies (X-ray crystallography) to analyze how mutations affect active-site architecture and ligand binding [34]. | Provides a snapshot of the enzyme's catalytic state. |

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing Catalytic Efficiency via Directed Evolution

The following workflow is adapted from successful studies on microbial uricases and β-glucosidases [36] [35].

Library Generation via SEP and DDS

- Step 1: Segmental Error-prone PCR (SEP)

- Design primers to amplify the target gene (e.g., 16bgl) in ~500 bp segments.

- Perform epPCR on each segment using a standard epPCR kit. A sample 50 µL reaction mix: 10-100 ng DNA template, 1x epPCR buffer, 0.2 mM each dATP/dGTP, 1 mM each dCTP/dTTP, 0.5 mM Mn²⁺, 5 U Taq polymerase, and 0.5 µM primers [35].

- Thermocycler conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 50-60°C (primer-specific) for 45 s, 72°C for 1 min/kb; final extension at 72°C for 10 min [35].

- Step 2: Assembly PCR

- Purify the epPCR segments. Use them as templates and primers in an assembly PCR to reconstitute the full-length, mutated gene [35].

- Step 3: Directed DNA Shuffling (DDS) in S. cerevisiae

- Linearize your yeast expression vector (e.g., pYAT22) within the cloning site.

- Co-transform 1 µg of the assembled PCR product and 0.2 µg of linearized vector into competent S. cerevisiae cells using a standard yeast transformation protocol [35].

- Plate on appropriate selective medium (e.g., SC-URA for pYAT22) and incubate at 30°C for 2-3 days.

- Step 4: Plasmid Recovery and Amplification

- Isolate the plasmid library from the yeast transformant pool.

- Transform the isolated plasmid library into electrocompetent E. coli for high-efficiency amplification and subsequent storage as a glycerol stock [35].

High-Throughput Screening for Improved Activity

- Culture: Inoculate library clones into deep-well plates containing liquid selective medium. Incubate with shaking to express the enzymes [32].

- Lysate Preparation: Depending on the enzyme and host, screen using whole cells, permeabilized cells, or crude cell lysates [32].

- Activity Assay:

- For a β-glucosidase, assay activity by adding a colorimetric or fluorogenic substrate (e.g., p-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside, pNPG) to the lysates in a microtiter plate [35].

- After incubation, quench the reaction and measure the release of p-nitrophenol at 405 nm, or fluorescence if using a fluorogenic substrate [35].

- Select the top 0.1-1% of variants showing the highest activity for the next round of evolution.

Characterization of Evolved Hits

- Kinetic Analysis: Purify the top-performing variants and the wild-type enzyme. Determine kinetic parameters (kcat, KM, kcat/KM) under standard conditions to quantify improvement [36] [34].

- Thermostability Assessment: Perform thermal shift assays or incubate enzymes at elevated temperatures for various times, then measure residual activity to assess stability gains [34].

- Structural Analysis (If Possible): Use site-directed mutagenesis to confirm the role of key substitutions [36]. For deeper insight, employ X-ray crystallography and molecular dynamics simulations to understand how mutations (especially distal ones) affect active-site architecture, structural dynamics, and the catalytic cycle [34].

Directed Evolution Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental principle behind rational design for site-directed mutagenesis? Rational design is a strategy to engineer enzymes by predicting mutations based on the understanding of the relationship between protein structure and function [37]. It involves using computational and bioinformatic tools to analyze an enzyme's three-dimensional structure, identify key amino acid residues that influence catalytic activity, stability, or selectivity, and then introducing specific mutations via site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) to achieve a desired improvement [37] [6].

FAQ 2: How do I select which amino acid residues to mutate? Residues are typically selected based on their role in the enzyme's structure and function. Common strategies include [37]:

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Identifying conserved residues or "conserved but different" (CbD) sites by comparing sequences of homologous enzymes [37].

- Analysis of the Catalytic Pocket: Targeting residues involved in substrate binding, transition state stabilization, or the chemical reaction step itself. This often involves molecular docking to understand enzyme-substrate interactions [4] [6].

- Steric Hindrance Considerations: Mutating residues that create spatial constraints to better accommodate a substrate or favor a specific enantiomer [37].

- Interaction Network Analysis: Remodeling hydrogen bonds or other non-covalent interactions around the substrate or in the protein core to improve activity or stability [37].

FAQ 3: What are the most common issues encountered during a rational design project? Common issues include:

- Inaccurate Computational Predictions: Predicted beneficial mutations may not yield improvements in the wet-lab experiment due to the complexity of enzyme dynamics [37] [6].

- Low Catalytic Activity in Mutants: Designed variants may show reduced or no activity, often because a mutation perturbed the precise geometry of the active site or key dynamic motions [37] [4].

- Poor Protein Expression or Stability: Mutations can sometimes destabilize the protein fold, leading to aggregation or reduced solubility [6] [38].

- Experimental Noise in High-Throughput Screening: Background signal or assay variability can obscure the detection of genuinely improved variants [39] [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Computationally Designed Mutants Show No Improvement in Activity

Issue: After performing SDM based on computational predictions (e.g., binding free energy calculations), the expressed and purified mutant enzymes do not show the expected increase in catalytic efficiency.

Solution: A systematic troubleshooting approach is required [39] [40].

Step 1: Verify the Experiment

Step 2: Re-examine the Computational Design

- Check Structural Integrity: Use tools like Ramachandran plot analysis to ensure the modeled mutation does not cause significant backbone strain or deviate from allowed conformational angles [6].

- Analyze Dynamics: Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MDS) can reveal if the mutation has unintended consequences on protein flexibility or stability. Check the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) and Radius of Gyration from MDS data [6].

- Confirm Substrate Pose: Re-dock the substrate into the mutated model to verify that the binding mode is as predicted and still productive for catalysis [4].

Step 3: Check Equipment and Reagents

- Ensure all reagents (substrates, cofactors, buffers) are fresh, properly stored, and not degraded [39].

- Calibrate any instruments used in the assay (e.g., spectrophotometers, plate readers).

Step 4: Change Variables Systematically

- Test the mutant enzyme's activity under a broader range of conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, substrate concentration) to see if the improvement is condition-specific [38].

- If possible, test activity with a different substrate to see if the mutation altered substrate specificity rather than overall activity [37].

Problem: High Experimental Variance in Screening Data Obscures Results

Issue: When screening a library of SDM-generated variants, the data has high error bars, making it difficult to distinguish improved mutants from the wild-type.

Solution: Focus on optimizing the assay protocol and controls [39] [40].

Step 1: Implement Robust Controls

Step 2: Review the Protocol in Detail

Step 3: Test Key Variables One at a Time

- Generate a list of variables that could contribute to noise (e.g., incubation times, reagent concentrations, number of wash steps) [39].

- Systematically test these variables one by one. For instance, try a slightly higher or lower enzyme concentration in the assay to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio [39] [40].

Workflow for Troubleshooting Rational Design Experiments

The following diagram illustrates a logical, step-by-step workflow for diagnosing and resolving common issues in a rational design project.

Data Presentation: Successful Applications of Rational Design

The table below summarizes quantitative data from recent studies where rational design and SDM successfully enhanced enzyme performance, demonstrating the power of this approach.

Table 1: Summary of Successful Enzyme Engineering via Rational Design and Site-Directed Mutagenesis

| Enzyme | Rational Design Strategy | Key Mutation(s) | Catalytic Efficiency Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oenococcus oeni β-Glucosidase | Molecular docking & binding energy scanning of catalytic pocket | F133K, N181R | Activity increased by 3.81 and 4.18 times, respectively; improved thermal stability. | [4] |

| Enterobacter faecalis Arginine Deiminase (ADI) | Computer-aided site-specific mutation near catalytic loops | F44W, E220I, T340I | Specific activity increased by 1.33 to 2.53 times that of the wild-type enzyme. | [38] |

| Cellulase (1FCE) | Computational mutagenesis for improved substrate dynamics | Pro174Ala, Thr226Leu | Binding free energy (ΔG) improved by 23.3% and 13.0%, respectively. | [6] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana Halide Methyltransferase (AtHMT) | AI-powered library design (Protein LLM & Epistasis Model) | Not Specified | 16-fold improvement in ethyltransferase activity achieved in 4 weeks. | [43] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: A Standard Workflow for Rational Design and Validation

This protocol outlines the key steps from initial computational analysis to the experimental validation of designed mutants [37] [4] [6].

Protocol Title: Integrated Computational and Experimental Workflow for Enzyme Engineering via Rational Design.

Protocol Description: This protocol describes an end-to-end process for enhancing enzyme catalytic efficiency. It begins with in silico analysis to identify mutation sites, followed by site-directed mutagenesis, protein expression, and biochemical characterization.

Protocol Steps:

Target Identification and Structural Analysis

- Description: Retrieve the target enzyme's 3D structure from the PDB (e.g., 1FCE, 1AVA). If unavailable, use AI-based tools like AlphaFold2 to generate a reliable model [6] [44].

- Checklist:

- Obtain protein sequence and structure.

- Perform multiple sequence alignment with homologous enzymes.

- Identify conserved residues and potential catalytic residues.

Molecular Docking and Residue Selection

- Description: Dock the substrate of interest into the enzyme's active site using software like CB-DOCK2. Analyze the interaction network to identify residues for mutagenesis that influence substrate binding, steric hindrance, or transition state stabilization [4] [6].

- Checklist:

- Perform molecular docking.

- Calculate binding free energy (ΔG).

- Select target residues based on interaction analysis and energy calculations.

In-silico Mutagenesis and Prediction

- Description: Use computational tools (e.g., PyMOL, FoldX, Rosetta) to introduce specific amino acid changes and predict the change in binding free energy (ΔΔG). Select mutants with predicted lower (more negative) ΔG for experimental testing [37] [6].

- Checklist:

- Model mutations in silico.

- Run ΔΔG calculations.

- Filter and rank promising mutants.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Plasmid Construction

- Description: Design primers for the selected mutations. Perform site-directed mutagenesis PCR using a high-fidelity polymerase. Use a method like HiFi-assembly to achieve high accuracy (~95%), eliminating the need for intermediate sequencing and enabling a continuous workflow [43].

- Checklist:

- Design and order mutagenesis primers.

- Perform mutagenesis PCR and DpnI digestion.

- Transform into cloning host and sequence-verify the plasmid.

Protein Expression and Purification

- Description: Transform the verified plasmid into an expression host (e.g., E. coli). Induce protein expression and purify the protein using a method like affinity chromatography. Verify purity and concentration via SDS-PAGE [4].

- Checklist:

- Transform expression host.

- Induce protein expression.

- Purify protein and confirm via SDS-PAGE.

Enzyme Characterization

- Description: Determine the kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) and specific activity of the wild-type and mutant enzymes under optimal conditions (pH, temperature). Assess thermal stability by measuring residual activity after incubation at elevated temperatures [4] [38].

- Checklist:

- Measure enzyme activity across substrate concentrations.

- Calculate kinetic parameters.

- Perform thermal stability assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Rational Design Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for accurate PCR amplification during SDM, minimizing spurious mutations. | Essential for constructing mutant libraries with high accuracy as used in automated biofoundries [43]. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., CB-DOCK 2) | Computationally predicts how a substrate binds to the enzyme active site, guiding residue selection. | Used to model enzyme-substrate complexes and calculate binding free energy changes (ΔΔG) for proposed mutants [6]. |

| Protein Stability Prediction Tools (e.g., FoldX, Rosetta) | Predicts the change in protein folding stability (ΔΔG) upon mutation. | Filters out destabilizing mutations early in the design process, focusing resources on viable candidates [37] [6]. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resin | For purifying recombinant proteins based on a specific tag (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag). | Critical for obtaining pure enzyme samples for reliable kinetic assays and structural characterization [4]. |

| Spectrophotometer / Plate Reader | Instrument to measure enzyme activity by detecting changes in absorbance or fluorescence over time. | Used in high-throughput screening of mutant libraries to quantify catalytic activity and identify hits [43] [44]. |

The MutaT7 system represents a significant advancement in the field of continuous directed evolution, enabling researchers to enhance enzyme catalytic efficiency through targeted in vivo mutagenesis. Unlike traditional directed evolution methods that rely on labor-intensive, iterative rounds of in vitro mutagenesis and screening, MutaT7 combines mutagenesis and selection into a single, continuous process within living bacterial cells [45]. This system utilizes a chimeric protein consisting of T7 RNA polymerase fused to a base deaminase, which introduces targeted mutations specifically in genes of interest (GOIs) under the control of T7 promoters [46] [47]. By linking enzyme activity directly to bacterial growth fitness and employing high-throughput continuous culture systems, MutaT7 facilitates the automated evolution of enzyme variants with improved properties, dramatically accelerating the engineering of biocatalysts for industrial and pharmaceutical applications [45].

Table: Key Components of a Growth-Coupled Continuous Directed Evolution (GCCDE) System Using MutaT7

| System Component | Description | Function in Enzyme Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| MutaT7 Mutagenesis Machinery | T7 RNA polymerase fused to cytidine/adenine deaminase(s) [46] [47] | Introduces targeted C→T (G→A) and/or A→C (T→G) transition mutations in the GOI. |

| Selection Plasmid | Plasmid carrying the GOI under a T7 promoter and a biosensor circuit [46] | Links improved enzyme activity to a selectable phenotype (e.g., antibiotic resistance, growth advantage). |

| Growth-Coupled Selection | Culture system where enzyme activity provides essential nutrients [45] | Enriches superior enzyme variants by coupling their activity to host cell growth rate. |

| DNA Repair Pathway Knockdown | CRISPRi-mediated suppression of repair enzymes like Ung and Nfi [46] | Increases mutagenesis efficiency by preventing repair of deaminated bases. |

| Continuous Culture Apparatus | Automated bioreactor for maintaining continuous bacterial growth [45] | Allows for prolonged mutagenesis and real-time selection under tunable pressure. |

System Setup and Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the MutaT7 platform requires careful assembly of genetic elements and choice of host strains. A common approach involves a three-plasmid system to modularize the key functions of mutagenesis, selection, and repair pathway interference [46]. The GOI is typically cloned into a selection plasmid downstream of a T7 promoter. A critical design feature is the use of flanking T7 terminators to prevent mutagenic enzymes from causing off-target mutations in adjacent DNA sequences, thereby confining diversity generation to the GOI [46]. The entire system is often implemented in engineered host strains like the E. coli Dual7 strain, which contains chromosomal mutations (e.g., Δung) to enhance the fixation of mutations and may already integrate the MutaT7 proteins [45].

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for setting up and running a MutaT7 continuous evolution experiment.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MutaT7 Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hypermutation Plasmid | Expresses the MutaT7 chimeric protein(s) [46]. | Some designs include two fusions (adenine & cytosine deaminase) for broader mutation scope [46]. |

| Selection Plasmid | Carries the gene of interest (GOI) and growth-coupling circuitry [46]. | Uses a T7 promoter for targeted mutagenesis and a biosensor to link enzyme output to fitness. |

| CRISPRi Knockdown Plasmid | Expresses dCas9 and gRNAs to knock down DNA repair pathways [46]. | gRNAs typically target ung (uracil-DNA glycosylase) and nfi (endonuclease V) to boost mutation rates. |

| Specialized E. coli Strain | Host organism with optimized genetic background. | Dual7 strain (derived from DH10B, Δung, lacZ-), or dam-methylase proficient strains for template prep [45] [48]. |

| Chemically Defined Medium | Medium for growth-coupled selection. | Minimal medium with the enzyme's substrate as the sole carbon source (e.g., lactose) [45]. |

| Inducers | Small molecules to control system components. | Lactose or IPTG to induce MutaT7 expression; aTc for GOI expression from a P_tetO hybrid promoter [45]. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: Why am I observing an unacceptably low mutation rate in my target gene?

A low mutation rate can stem from several factors related to the efficiency of the mutagenesis machinery and the host's repair systems.

- Solution A: Verify Inducer and Promoter Function. Ensure the MutaT7 proteins are being adequately expressed. Confirm that the inducer (e.g., lactose or IPTG) is present at the correct concentration and is functional. Check the health of the culture and the activity of the promoter controlling MutaT7 expression [45] [46].

- Solution B: Enhance Mutagenesis Efficiency via DNA Repair Knockdown. The host's native DNA repair pathways actively counteract the deamination events caused by MutaT7. Implement a CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) system to knock down key base excision repair enzymes. As demonstrated in successful systems, this involves using gRNAs to target and suppress uracil-DNA glycosylase (ung) and endonuclease V (nfi), which can increase mutation rates up to 1000-fold [46].

- Solution C: Optimize Genetic Context of the GOI. Ensure the GOI is flanked by strong T7 terminators. This prevents the mutagenic enzymes from acting on regions outside the GOI and also focuses the mutational load where it is needed [46]. Furthermore, using a low-copy-number plasmid for the GOI can help maintain stability over long evolution experiments [45].

FAQ 2: Why am I failing to establish a proper link between enzyme activity and cellular fitness (growth-coupled selection)?

A weak or non-existent growth-selection link means improved enzyme variants are not being enriched, causing evolution to fail.

- Solution A: Use a Dedicated Host Strain. Employ a host strain that lacks the native activity you are trying to evolve. For example, when evolving a β-galactosidase, use an E. coli strain (like Dual7) with mutations in the native lacZ gene to ensure that cellular growth in a lactose minimal medium depends solely on the activity of your engineered enzyme [45].

- Solution B: Design a Robust Selection Circuit. The genetic circuit linking enzyme output to a fitness advantage must be carefully designed. You can use:

- Positive Selection: The product of the enzymatic reaction induces the expression of a gene essential for metabolism in a defined medium (e.g., a sorbitol metabolism gene when sorbitol is the sole carbon source) [46].

- Negative Selection: The enzyme's product suppresses the expression of a growth-slowing or toxic gene (e.g., an antisense RNA that inhibits the expression of a gene that interferes with ribosome function) [46].