Engineering Thermostable Enzymes: AI-Driven Strategies for Industrial and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing enzyme thermostability, a critical factor for industrial and pharmaceutical biocatalysis.

Engineering Thermostable Enzymes: AI-Driven Strategies for Industrial and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for enhancing enzyme thermostability, a critical factor for industrial and pharmaceutical biocatalysis. It covers foundational principles of protein stability, explores cutting-edge methodologies from rational design to machine learning, and addresses key challenges like the stability-activity trade-off. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes recent advances in AI-aided engineering, practical troubleshooting guides, and comparative validation of techniques, offering a roadmap for developing robust biocatalysts for greener manufacturing and advanced biomedical research.

The Why and How: Fundamental Principles of Enzyme Thermostability

Thermostability as a Key Driver in Industrial and Pharmaceutical Biocatalysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary molecular determinants of enzyme thermostability? Enhanced thermostability is achieved through a complex network of stabilizing forces. Key determinants include hydrophobic interactions that drive the folding of a stable core, hydrogen bonds and salt bridges that provide structural rigidity, and disulfide bonds that covalently cross-link regions of the protein [1] [2]. Strategies like cavity filling in short-loop regions by mutating to hydrophobic residues with larger side chains (e.g., Tyr, Phe, Trp) also significantly reduce internal voids and enhance stability [3].

FAQ 2: How can I overcome the common stability-activity trade-off during enzyme engineering? The stability-activity trade-off is a major challenge in enzyme evolution. A promising solution is the use of integrated strategies that consider conformational dynamics, such as the machine learning-based iCASE (isothermal compressibility-assisted dynamic squeezing index perturbation engineering) strategy [4]. This approach constructs hierarchical modular networks for enzymes and uses a dynamic response predictive model to identify mutations that synergistically improve both stability and activity, as validated across multiple enzyme classes [4].

FAQ 3: What advanced computational tools are available for predicting stabilizing mutations? The field has moved beyond traditional methods to sophisticated computational toolkits. Key resources include:

- Structure-based supervised Machine Learning models that predict enzyme function and fitness by analyzing epistasis and conformational dynamics [4].

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) tools like FireProtASR, FastML, and PhyloBot, which resurrect stable ancestral enzymes [5].

- Stability prediction algorithms like Rosetta and FoldX, which calculate changes in folding free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation and are often integrated with B-factor analysis to identify flexible, destabilizing regions [4] [3] [5].

FAQ 4: Why is thermostability crucial for industrial biocatalytic processes? Thermostability is a key indicator of overall enzyme robustness. Industrially, thermostable enzymes (thermozymes) lead to higher reaction rates, reduced risk of microbial contamination, improved substrate solubility, and longer catalyst half-lives, which significantly lower operational costs [3] [2]. Furthermore, operating at higher temperatures is often necessary to match industrial process conditions, making thermostability a prerequisite for successful application [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Loss of Enzyme Activity at High Temperatures

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Excessive flexibility in key structural regions.

- Solution: Implement B-factor guided design. Target residues in regions with high B-factor values (indicating high flexibility) for rigidifying mutations. This can be combined with computational tools like Rosetta to predict stabilizing mutations that reduce flexibility [5].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Obtain your enzyme's 3D structure (via X-ray crystallography or a high-confidence AlphaFold2 model).

- Calculate B-factors for each residue (available from PDB files or via molecular dynamics simulations).

- Target the most flexible loop or surface regions for saturation mutagenesis.

- Use FoldX or Rosetta to perform virtual screening of mutations and calculate the predicted ΔΔG.

- Experimentally validate the top 10-20 candidates for improved thermal half-life (t₁/₂).

Cause 2: Presence of destabilizing cavities within the protein structure.

- Solution: Apply short-loop engineering. Identify rigid "sensitive residues" in short loops that create cavities. Mutate these to bulky hydrophobic residues (Tyr, Phe, Trp) to fill the void [3].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Identify short loops (3-6 residues) in your enzyme's structure.

- Use a tool like FoldX to perform virtual saturation mutagenesis on each residue in the short loop.

- Identify "sensitive residues" where many mutations, especially to bulky hydrophobic ones, yield a negative ΔΔG (stabilizing).

- Construct a saturation mutagenesis library at the sensitive residue position.

- Screen for variants with improved melting temperature (Tm) and half-life.

Problem: Enzyme Performs Well in Lab But Fails Under Industrial Process Conditions

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Laboratory assays do not mimic industrial reaction environments (e.g., high substrate/product concentrations, solvents, shear stress).

- Solution: Employ machine learning-guided engineering with data collected under industrially-relevant conditions. Use strategies like iCASE that incorporate dynamics under "new-to-nature" conditions to guide evolution [7] [4].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Perform initial screenings under conditions that more closely mimic your industrial process (e.g., with co-solvents, high substrate loading).

- Sequence variants that perform well under these harsh conditions to build a dataset.

- Train a structure-based supervised ML model on this dataset to predict fitness.

- Use the model to screen a vast mutational space in silico and select optimal combinations for experimental testing.

- Validate the final variants in a bench-scale reactor that mimics the full industrial process.

Experimental Protocols for Enhancing Thermostability

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Guided Thermostability Engineering (iCASE Strategy)

This protocol is adapted from the iCASE strategy for the evolution of enzyme stability and activity [4].

Objective: Synergistically improve the thermostability and activity of an enzyme.

Workflow:

Materials & Steps:

- Identify Fluctuation Regions: Calculate the isothermal compressibility (βT) profile across the enzyme's structure using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify high-fluctuation regions (e.g., specific loops, α-helices) [4].

- Calculate Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI): Compute the DSI, which is coupled to the active center, to identify residues critical for function. Select candidate residues with a DSI > 0.8 (top 20%) [4].

- Virtual Screening: Predict the change in free energy (ΔΔG) for mutations at candidate sites using computational tools like Rosetta 3.13 or FoldX. Filter for mutations with negative ΔΔG values [4] [3].

- Library Construction & Screening: Construct a site-saturation or combinatorial mutagenesis library based on the in silico predictions. Express and purify the mutant enzymes.

- Experimental Validation:

- Activity Assay: Measure specific activity under standard and elevated temperature conditions.

- Thermal Stability: Determine the melting temperature (Tm) via differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) and the half-life (t₁/₂) at the target process temperature.

Protocol 2: Short-Loop Engineering for Cavity Filling

This protocol details the stabilization of enzymes by targeting rigid sites in short loops [3].

Objective: Enhance thermal stability by filling internal cavities in short-loop regions.

Workflow:

Materials & Steps:

- Identify Short Loops: From the enzyme's 3D structure, identify short loops, typically consisting of 3-6 amino acid residues [3].

- Virtual Saturation Screening: Use FoldX or a similar tool to perform virtual saturation mutagenesis on every residue in the short loop. Calculate the ΔΔG for each possible mutation [3].

- Find Sensitive Residue: Identify a "sensitive residue" where a high number of mutations (particularly to large, hydrophobic residues) result in a negative ΔΔG. This residue is often alanine, glycine, or serine creating a cavity [3].

- Library Construction: Build a saturation mutagenesis library focused on the identified sensitive residue.

- Expression & Screening: Express the library variants and screen for improved thermal stability. Primary screening can be done via DSF for increased Tm. Confirm hits by measuring the half-life at a elevated temperature (e.g., 60°C), where a longer half-life indicates a more stable enzyme [3].

Table 1: Performance Improvements from Advanced Engineering Strategies

| Engineering Strategy | Enzyme Example | Reported Improvement in Thermostability | Reported Improvement in Activity | Key Mutations / Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iCASE (ML-based) [4] | Xylanase (XY) | Tm increased by 2.4 °C | Specific activity increased 3.39-fold | R77F/E145M/T284R |

| Short-Loop Engineering [3] | Lactate Dehydrogenase (PpLDH) | Half-life increased 9.5-fold | Not Specified | A99Y (cavity filling) |

| Short-Loop Engineering [3] | Urate Oxidase (UOX) | Half-life increased 3.11-fold | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| B-Factor/ML Combined [5] | Various (Case Studies) | Half-life increased up to 67-fold; >400-fold half-life increase in some cases | Significantly improved enantioselectivity | Targeting high B-factor regions guided by ML |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for Thermostability Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta 3.13 [4] | Software suite for protein structure prediction and design; used for calculating ΔΔG of mutations. | Predicting stabilizing mutations in high-fluctuation regions identified by the iCASE strategy [4]. |

| FoldX [3] | A computational tool for the quantitative estimation of the importance of interactions for protein stability. | Performing virtual saturation mutagenesis to find "sensitive residues" in short loops and calculate their ΔΔG [3]. |

| FireProtASR / PhyloBot [5] | Software tools for Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR). | Resurrecting thermostable ancestral enzymes to serve as robust starting templates for further engineering [5]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Calculating isothermal compressibility (βT) profiles and root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions [4]. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | High-throughput method to measure protein thermal unfolding (Tm). | Initial high-throughput screening of mutant libraries for improved melting temperature [3]. |

For researchers in industrial enzyme development, understanding the non-covalent forces that maintain a protein's functional three-dimensional structure is paramount. The intricate balance of hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and salt bridges determines an enzyme's thermostability, activity, and overall robustness under industrial process conditions. These forces work in concert to stabilize the folded, catalytically active conformation against the denaturing effects of high temperature, extreme pH, and chemical solvents. Current research focuses on manipulating these interactions through rational design and machine learning to engineer enzymes that withstand harsh industrial environments, directly addressing the critical stability-activity trade-off that often hinders biocatalyst performance [4] [8].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and contributions of these key forces:

Table: Key Non-Covalent Forces Governing Enzyme Thermostability

| Interaction Force | Chemical Basis | Relative Energy Contribution | Primary Role in Stability | Prevalent Locations in Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Entropic driving force from water molecule reorganization; burial of non-polar residues [9]. | Contributes ~1-5 kcal/mol per interaction; major driver of folding [9]. | Provides thermodynamic stability for the folded core; contributes to mechanical resistance [9]. | Protein core; subunit interfaces [9]. |

| Hydrogen Bonds | Dipole-dipole attraction between a hydrogen atom covalently bound to an electronegative atom (e.g., O, N) and another electronegative atom [8]. | ~1-4 kcal/mol per bond in proteins [10]. | Maintains secondary structure (α-helices, β-sheets); crucial for mechanical strength [9]. | Throughout polypeptide backbone and side chains. |

| Salt Bridges | Combination of electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding between oppositely charged residues (e.g., Asp/Glu with Lys/Arg) [10] [11]. | ~3-6 kcal/mol in proteins; highly dependent on environment [10] [12]. | Stabilizes tertiary and quaternary structure; can act as molecular clips to lock conformations [11]. | Often on protein surface; can be buried in specific cases [10]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Force Contributions

The relative importance of these interactions shifts depending on whether one considers thermodynamic stability under equilibrium conditions or mechanical stability against forced unfolding. Understanding this distinction is vital for designing enzymes suited for specific industrial processes, such as those involving high-shear fluid flow.

Recent computational studies using Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) simulations have quantified the contribution of hydrophobic interactions to the total resistance force during mechanical unfolding to be between one-fifth and one-third. The remaining majority of the force is attributed primarily to hydrogen bonds. This highlights the superior role of highly directional hydrogen bonds in providing immediate mechanical resistance, whereas hydrophobic forces, while crucial for initial folding, exhibit a shallower free energy dependence on extension [9].

Table: Relative Contribution to Thermodynamic vs. Mechanical Stability

| Interaction Force | Contribution to Thermodynamic Stability (Folding) | Contribution to Mechanical Stability (Resistance to Unfolding) |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interactions | Major driver; significant free-energy gain from burying non-polar surfaces [9]. | Minor to moderate contributor (20-33% of total force peaks in SMD) [9]. |

| Hydrogen Bonds | Controversial role due to exchange with solvent; can be neutral or mildly stabilizing [9]. | Primary contributor (67-80% of force peaks); key to mechanical integrity of β-sheets [9]. |

| Salt Bridges | Context-dependent; can be stabilizing or destabilizing; strength is modulated by solvent exposure and ionic strength [10] [12]. | Can provide specific, strong points of conformational locking; role in mechanical stability is less explored [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Interactions

Protocol: Quantifying Salt Bridge Stability via Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Thermal Denaturation

This protocol assesses a specific salt bridge's contribution to global protein stability by mutating the participating residues and measuring the change in melting temperature.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Pseudo-Wild-Type Protein: A engineered background protein variant that prevents precipitation at high pH, allowing for clean measurement [10].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit: For creating point mutations (e.g., Asp→Asn, Lys→Ala) to disrupt the salt bridge.

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrophotometer: Equipped with a temperature-controlled Peltier unit.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or other appropriate buffer.

Methodology:

- Generate Mutants: Create single and double mutants where the charged residues forming the suspected salt bridge are replaced with neutral residues (e.g., Asp to Asn, Glu to Gln, Lys to Leu, Arg to Ala).

- Purify Proteins: Express and purify the wild-type and all mutant proteins to homogeneity using standard chromatography methods (e.g., FPLC, affinity chromatography) [13].

- Thermal Denaturation: For each protein, prepare a solution in a suitable buffer. Using a CD spectrophotometer, monitor the change in ellipticity at a wavelength sensitive to secondary structure (e.g., 222 nm for α-helices) while applying a linear temperature ramp (e.g., 1-2 °C/min).

- Data Analysis: Determine the melting temperature ((Tm)) for each variant from the denaturation curve's inflection point. The free energy contribution of the salt bridge ((ΔΔG)) can be calculated using the formula: (ΔΔG = ΔTm \times ΔS), where (ΔT_m) is the difference in melting temperature between the wild-type and mutant, and (ΔS) is the denaturational entropy change for the protein, which must be determined independently or obtained from literature [10].

Protocol: Quantifying Salt Bridge Stability via NMR Titration and pKa Shift Analysis

This method leverages Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to detect the pKa perturbation of a residue involved in a salt bridge, providing a direct, local measure of the interaction strength.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Isotopically Labeled Protein: (^{15}\text{N})-labeled protein is typically required for observing backbone amide chemical shifts.

- NMR Buffer: A low-ionic-strength buffer that does not interfere with the titration (e.g., 20 mM phosphate).

- D₂O: For locking and shimming the NMR spectrometer.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of identical (^{15}\text{N})-labeled protein samples across a range of pH values.

- NMR Acquisition: For each sample, collect a (^{1}\text{H})-(^{15}\text{N}) HSQC spectrum. The chemical shift of the proton attached to the C2 carbon of a histidine side chain or the amide protons of backbone nuclei adjacent to acidic/basic residues are excellent probes.

- Titration Curve Fitting: Plot the chemical shift of a specific nucleus as a function of pH. Fit the data to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation to determine the pKa of the residue.

- Free Energy Calculation: Compare the measured pKa of the residue in the folded protein ((pKa^{folded})) to its pKa in the unfolded state (often measured in a model peptide or inferred from the mutant, (pKa^{unfolded})). The free energy contribution of the salt bridge is calculated using: (ΔG = -RT \ln(K{a}^{folded}/K{a}^{unfolded}) = -2.303RT(pKa^{folded} - pKa^{unfolded})), where (R) is the gas constant and (T) is the temperature in Kelvin [10]. A large, perturbed pKa value for a histidine (e.g., shifted from 6.8 in the unfolded state to 9.05 in the folded state) is a hallmark of its participation in a stabilizing salt bridge [10].

Experimental Workflow for Quantifying Salt Bridge Stability

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Issue 1: Engineered Salt Bridge Does Not Enhance Thermostability

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Destabilizing Entropic Cost | Constraining charged, flexible side chains into a salt bridge reduces conformational entropy, which can outweigh the energetic benefit of the interaction [10]. | Prefer surface salt bridges where side chains are already partially constrained. Use structural analysis to target residues with low conformational flexibility. |

| Unfavorable Desolvation Penalty | The energy cost of stripping water molecules from the charged groups before they form the bridge can be prohibitively high, especially in buried environments [10] [12]. | Design salt bridges in areas with low local dielectric constant or where partial desolvation already occurs. Avoid burying charged groups fully. |

| High Ionic Strength Buffer | The electrostatic component of the salt bridge is screened by ions in the solution, significantly weakening the interaction [10] [12]. | Assess enzyme stability under low ionic strength conditions relevant to the final application. Re-engineer the local environment to include cooperative hydrogen bonds. |

Issue 2: Enzyme is Mechanically Unstable Under High-Shear Flow Reactors

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Shear Plane Stabilization | The network of hydrogen bonds connecting secondary structure elements (like β-strands) is insufficient to resist mechanical force, leading to unraveling [9]. | Focus rational design on strengthening inter-strand hydrogen bonds in key β-sheets. Consider introducing proline residues in loops to reduce flexibility. |

| Insufficient Hydrophobic Core Consolidation | While less critical for mechanical resistance, a consolidated core provides a foundational stability [9]. | Use computational protein design (e.g., Rosetta) to identify core mutations that increase packing density without compromising activity. |

Issue 3: Introduced Disulfide Bond Fails to Stabilize or Inactivates Enzyme

| Possible Cause | Explanation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction of Strain | The disulfide bond was geometrically poorly designed, forcing the protein backbone into a high-energy conformation [8]. | Use modeling software (e.g., Modeller, PyRosetta) to validate the geometry of the proposed disulfide (Cα-Cα, Cβ-Cβ, χ3 distances and dihedrals) before mutagenesis. |

| Disruption of Critical Dynamics | The disulfide bond overly rigidifies a region of the protein required for catalytic activity or substrate binding [4]. | Avoid introducing disulfides near active site loops. Analyze B-factors (crystallographic temperature factors) to target flexible, non-functional regions for stabilization. |

Advanced Engineering Strategies and Machine Learning

Moving beyond single-point mutations, the field is increasingly adopting multi-dimensional strategies that consider conformational dynamics and long-range interactions.

Machine Learning (ML) in Enzyme Engineering: ML models are being developed to predict the fitness of enzyme variants by learning from sequence-structure-function data. Structure-based supervised ML models can account for non-additive effects (epistasis) where combinations of mutations have unpredictable outcomes, a common challenge in stability engineering [4]. These models help navigate the fitness landscape more efficiently than traditional directed evolution.

The iCASE Strategy: A recent ML-based approach, isothermal compressibility-assisted dynamic squeezing index perturbation engineering (iCASE), constructs hierarchical modular networks for enzymes. It uses metrics like isothermal compressibility (βT) fluctuations and a Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI) to identify flexible regions and key residues for mutation that can enhance both stability and activity, successfully demonstrating universality across monomeric enzymes, TIM barrel structures, and hexameric enzymes [4].

Immobilization for Enhanced Stability: Engineering the enzyme's external environment is as crucial as engineering the protein itself. Creating a stable, porous "interphase" at the water-oil interface, inspired by cell membranes, can dramatically enhance operational stability. For example, immobilizing Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) within a hydrophobic silica nanoshell at a Pickering emulsion interface enabled continuous-flow olefin epoxidation for over 800 hours with a 16-fold increase in catalytic efficiency, by protecting the enzyme from deactivation by H₂O₂ while providing access to substrates [14].

Advanced Strategies for Enzyme Stabilization

Extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme environments—possess naturally robust enzymes, known as extremozymes, that maintain structure and function under high temperatures, extreme pH, and high salinity [15]. These biological blueprints provide innovative solutions for overcoming the common challenge of enzyme instability in industrial processes [16]. This technical support center equips researchers with the practical knowledge to harness these powerful natural designs, featuring troubleshooting guides, detailed protocols, and essential resources to accelerate your work in enzyme engineering.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What makes extremophiles a superior source for industrial enzymes? Extremophiles have evolved unique biochemical adaptations, such as specialized enzymes (extremozymes), stress-resistant cellular mechanisms, and unique biomembrane structures, to survive in harsh conditions [15]. These natural adaptations result in enzymes with incredible stability and bioactivity under industrial process conditions that would deactivate conventional enzymes [16] [15].

FAQ 2: How can I troubleshoot a loss of enzyme activity at high temperatures? A loss of activity often indicates insufficient thermostability. First, verify the enzyme's optimal temperature range from the supplier's datasheet. If activity remains low, consider engineering the enzyme for enhanced stability. Machine learning strategies, like the iCASE strategy, can help identify mutation sites that improve thermal stability without sacrificing activity [4]. Sourcing the enzyme from thermophilic organisms is another effective approach [16].

FAQ 3: My enzyme reaction shows unexpected or off-target cleavage. What could be the cause? Unexpected cleavage, often called "star activity," in enzymes like restriction enzymes can be caused by improper reaction conditions [17] [18]. To resolve this:

- Always use the manufacturer's recommended reaction buffer.

- Reduce the number of enzyme units in the reaction, as excess enzyme can promote star activity.

- Decrease the incubation time to the minimum required for complete digestion.

- Consider using High-Fidelity (HF) engineered enzymes, which are designed to eliminate star activity [17].

FAQ 4: Can I use a recombinant protein after shipping and storage at room temperature? Many lyophilized (freeze-dried) recombinant proteins are stable when shipped at ambient temperature. Manufacturers often perform stress tests to ensure stability for a specific window (e.g., 3 days at 37°C) [19]. Upon receipt, you should store the product at the recommended long-term temperature (typically -20°C) and reconstitute it according to the datasheet instructions. If the product was not delivered within the guaranteed timeframe, contact technical support [19].

FAQ 5: What are the key considerations for scaling up extremozyme applications? Scaling up requires a focus on stability and consistent production. Key considerations include:

- Stability Testing: Follow regulatory guidelines (e.g., ICH Q1) to understand the enzyme's stability profile under long-term storage and stress conditions [20].

- Production Yield: Many extremophiles are difficult to culture. Leveraging metagenomics to discover novel extremozymes and using heterologous expression in standard model hosts can overcome this challenge [15].

- Activity-Stability Balance: Be mindful of the trade-off between enzyme activity and stability. Advanced engineering strategies are often needed to improve both simultaneously [4].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common problems encountered when working with enzymes for industrial applications.

Table 1: Common Enzyme Experiment Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or No Digestion/Reaction [17] [18] | Incorrect buffer or salt inhibition; DNA/protein contamination; Methylation blocking recognition site; Too few enzyme units | Use the manufacturer's recommended buffer; Clean up DNA/protein to remove contaminants; Check enzyme sensitivity to Dam/Dcm methylation and use dam-/dcm- E. coli strains if needed [17]; Use 3-5 units of enzyme per µg of DNA [18]. |

| Unexpected Cleavage Pattern or Low Specificity [17] [18] | Star activity (off-target effects); Partial digestion due to contaminants; Contamination with another enzyme | Reduce enzyme units and incubation time; Use High-Fidelity (HF) enzymes; Purify DNA before digestion; Replace enzyme and buffer stocks [17]. |

| Low Enzyme Activity or Rapid Deactivation [4] [19] | Instability at process temperature or pH; Loss of activity during storage; Missing cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺) | Source enzymes from relevant extremophiles (e.g., thermophiles for high heat) [16]; Store enzymes at recommended temperature in single-use aliquots; Add recommended cofactors to the reaction [18]. |

| Low Transformation Efficiency | Incompletely digested DNA; Smear on agarose gel due to enzyme bound to DNA | Ensure complete digestion by cleaning up DNA and using enough enzyme; If a smear appears, lower the number of enzyme units or add SDS (0.1-0.5%) to the loading dye [17]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering Enzyme Thermostability Using a Machine Learning-Guided Workflow

This protocol is adapted from recent research on the iCASE (isothermal compressibility-assisted dynamic squeezing index perturbation engineering) strategy, which uses machine learning to balance the stability-activity trade-off in enzyme evolution [4].

Key Applications:

- Enhancing the thermal stability of industrial enzymes for processes like sugar degradation (xylanase), protein modification (protein-glutaminase), and polymer breakdown (PET hydrolase) [4].

- Rapidly generating enzyme variants with improved performance.

Materials:

- Wild-type enzyme gene sequence and 3D structure (e.g., from PDB).

- Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation software (e.g., GROMACS).

- Machine learning model (e.g., structure-based supervised ML).

- Rosetta software suite for free energy (ΔΔG) predictions.

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit.

- Equipment for protein expression and purification.

- Thermostability and activity assays (e.g., specific activity assay, differential scanning calorimetry for Tm).

Methodology:

- Identify High-Fluctuation Regions: Calculate the isothermal compressibility (βT) of the enzyme's secondary structures using MD simulations to identify flexible, high-fluctuation regions (e.g., loops, specific α-helices) [4].

- Select Mutation Sites: Apply the Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI), an indicator coupled with the active center, to residues in high-fluctuation regions. Select candidate residues with a DSI > 0.8 [4].

- Predict Energetic Effects: Use computational tools like Rosetta to predict the change in free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation for the candidate residues to filter for stabilizing mutations [4].

- Screen and Combine Mutants: Perform wet-lab experiments to test the screened single-point mutants for specific activity and thermal stability. Combine positive mutants to generate double or triple mutants and test for synergistic effects [4].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Enzyme Thermostability Engineering

| Reagent/Software | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Models enzyme dynamics and flexibility to identify high-fluctuation regions [4]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Model | Predicts enzyme function and fitness from sequence/structure data, guiding variant design [4]. |

| Rosetta Software | Predicts the change in free energy (ΔΔG) of protein mutants to screen for stabilizing mutations [4]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces specific point mutations into the gene encoding the enzyme. |

| Protein Expression System (e.g., E. coli) | Produces the wild-type and mutant enzyme proteins for testing. |

Protocol 2: Bioprospecting for Novel Extremozymes from Environmental Samples

This protocol outlines a culture-independent method for discovering novel enzymes from extremophiles using metagenomics [15].

Key Applications:

- Discovering novel biocatalysts from extreme environments (e.g., hot springs, deep-sea vents, saline lakes) that are difficult to replicate in the lab.

- Building a library of extremozymes for various industrial applications.

Materials:

- Environmental sample from an extreme habitat.

- DNA extraction kit (for complex samples).

- Metagenomic sequencing services.

- Bioinformatics software for sequence assembly and annotation.

- Heterologous expression host (e.g., E. coli).

- Functional screening assays (e.g., for antimicrobial activity, specific enzyme activity).

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Collect an environmental sample (e.g., soil, water, sediment) from an extreme habitat such as a hot spring or saline lake [16] [15].

- Metagenomic DNA Extraction: Extract total DNA directly from the environmental sample, capturing the genetic material of all microorganisms present, including those that are unculturable [15].

- Sequence and Analyze: Sequence the metagenomic DNA using high-throughput sequencing. Assemble the sequences and use bioinformatics tools to annotate genes, identifying potential enzyme-encoding genes (extremozymes) [15].

- Clone and Express: Clone the identified genes into a suitable heterologous expression host, such as E. coli, to produce the extremozyme [15].

- Functional Screening: Screen the expressed enzymes for desired functional activities, such as thermostability, antimicrobial properties, or specific catalytic functions [16] [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| dam-/dcm- E. coli Strains | Host strains for propagating plasmid DNA without Dam/Dcm methylation, which can block certain restriction enzymes [17]. |

| DNA Cleanup Kits | Removing contaminants like salts, solvents, or inhibitors from DNA samples prior to enzymatic reactions to ensure efficiency [17] [18]. |

| HF (High-Fidelity) Restriction Enzymes | Engineered enzymes that cut with high specificity to avoid star activity (off-target cleavage) [17]. |

| Recombinant Albumin (rAlbumin) | A non-animal-derived enzyme stabilizer used in modern reaction buffers to prevent enzyme degradation and maintain activity [17]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | A platform for rapid enzyme production without the need for living cells, accelerating the testing of engineered enzyme variants [21]. |

Workflow Diagrams

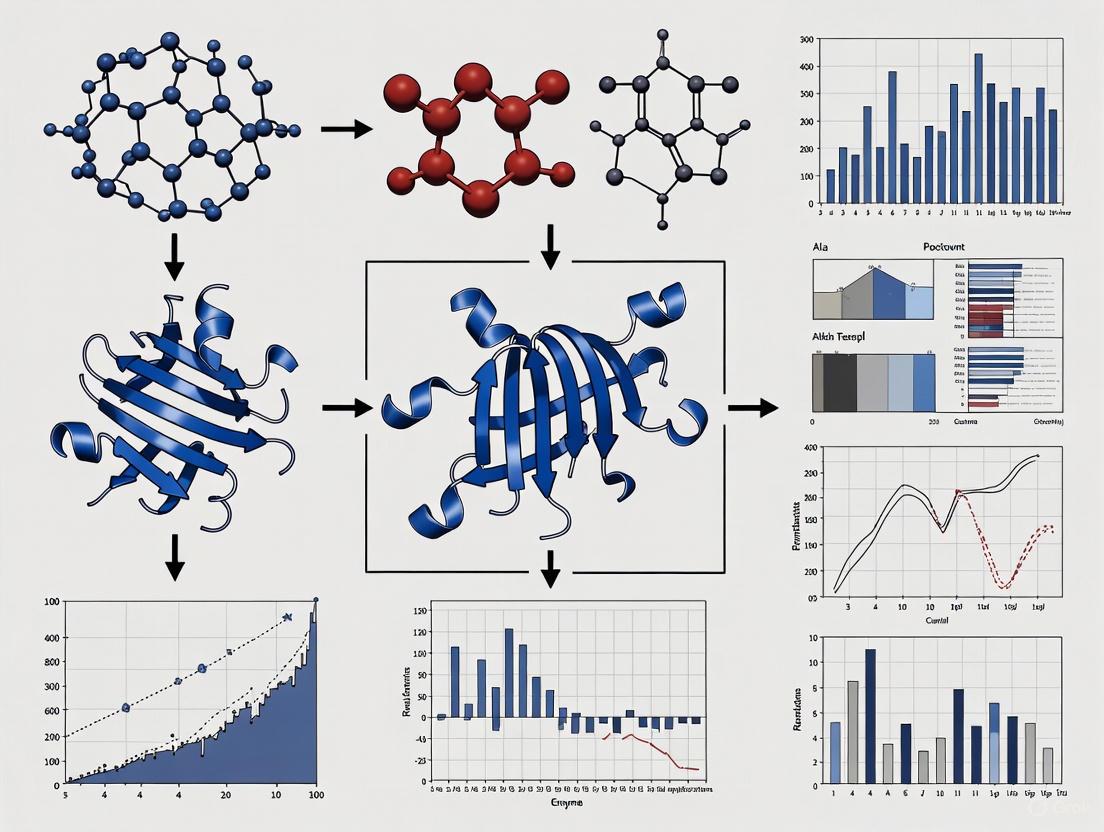

Machine Learning-Guided Enzyme Engineering Workflow

Metagenomic Discovery of Novel Extremozymes

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Interpreting Thermal Melt Curves

Problem: A researcher obtains a thermal melt curve for an enzyme but observes a broad, non-sigmoidal transition, making the melting temperature (Tm) difficult to determine.

Solution:

- Check Protein Purity and Homogeneity: A broad transition can indicate a heterogeneous sample. Analyze your enzyme preparation via SDS-PAGE to confirm purity. Impurities or protein aggregates can lead to complex unfolding patterns.

- Verify Buffer Conditions: The ionic strength and pH of the buffer significantly impact unfolding. Ensure you are using a standard, recommended buffer (e.g., 100 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) and confirm its compatibility with your detection method [22].

- Calculate a Melting Curve Quality Score (Q): Quantify the quality of your melt curve. Calculate Q = ΔFmelt / ΔFtotal, where ΔFmelt is the melting-associated fluorescence increase and ΔFtotal is the total fluorescence range between the minimum and maximum values from 20°C to 90°C. A high-quality curve typically has a Q value close to 1, while a low Q score (e.g., below 0.5) suggests a poorly folded protein or suboptimal experimental conditions [22].

- Correlate with Activity: Always correlate Tm with functional data. An enzyme with a high Tm but no activity may be misfolded. Perform a residual activity assay on a sample taken before the melt experiment to confirm the enzyme was active initially [23] [22].

Guide 2: Discrepancy Between Tm and Functional Half-Life

Problem: An enzyme variant shows an increased Tm in thermal melt assays, but its half-life at the target process temperature does not improve.

Solution:

- Understand the Stability-Activity Trade-off: Recognize that some stabilizing mutations can rigidify the enzyme, potentially reducing its catalytic activity or flexibility required for function. This is a known challenge in enzyme engineering [4].

- Measure Kinetic Stability Directly: Tm provides a measure of thermodynamic stability. For industrial processes, kinetic stability (resistance to irreversible inactivation over time) is often more relevant. Perform a half-life determination experiment by incubating the enzyme at the desired temperature and measuring residual activity over time [24].

- Investigate Local Rigidity: The mutation may have stabilized the overall structure (increasing Tm) but increased flexibility in a critical region like the active site, leading to faster inactivation. Strategies like increasing the rigidity of flexible segments near the active site can enhance kinetic stability without necessarily drastically altering the Tm [24].

- Use Complementary Metrics: Rely on both Tm and half-life. A small increase in Tm can sometimes translate to a large increase in half-life, and vice-versa. Use Tm for initial, high-throughput screening, and always confirm with functional half-life assays under process-relevant conditions [23] [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between an enzyme's Melting Temperature (Tm) and its half-life at an elevated temperature?

Answer: The Tm and half-life represent different aspects of enzyme stability. The Tm (Melting Temperature) is the temperature at which 50% of the enzyme molecules are unfolded. It is a thermodynamic parameter that indicates the point of major structural collapse and is typically measured by techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) or using fluorescent dyes [23] [22]. In contrast, the half-life at an elevated temperature is a kinetic parameter. It measures the time required for the enzyme to lose 50% of its initial activity under specific conditions (e.g., at 50°C). It directly reflects functional stability and is more predictive of performance in an industrial bioreactor where the enzyme is held at a high temperature for extended periods [23] [25].

FAQ 2: My experimental Tm value differs from a value I found in literature for the same enzyme. What are the common factors that cause this variation?

Answer: Tm is not an intrinsic constant for an enzyme; it is highly dependent on experimental conditions. Key factors causing variation include:

- Buffer Composition: The type and concentration of salts, pH, and specific ions (especially divalent cations like Mg²⁺) can dramatically shift Tm [26].

- Protein Concentration: For some oligomeric enzymes, Tm can vary with concentration [26].

- Scanning Rate: The temperature ramp rate in DSC or thermal melt assays can affect the observed Tm.

- Presence of Additives: Stabilizers like glycerol or sugars can increase Tm, while denaturants will decrease it [23].

- Definition of Tm: Ensure the same method defines Tm (e.g., from a DSC peak, from the inflection point of a fluorescence melt curve, or from CD spectroscopy) [23].

FAQ 3: How can I quickly assess if my purified enzyme is properly folded and active before running lengthy thermal stability assays?

Answer: The thermal melt curve itself can be a rapid diagnostic tool. Perform a thermal melt assay using a fluorescent dye like SYPRO Orange. A high-quality, sigmoidal melt curve with a high quality score (Q) generally indicates a well-folded, monodisperse protein population. Enzymes with high-quality melt curves are almost uniformly found to be active, while those with poor or flat melt curves are often inactive or denatured [22]. This provides a quick, low-consumption check before committing to more complex activity or stability assays.

FAQ 4: What strategies can I use to improve an enzyme's half-life without compromising its catalytic activity?

Answer: Overcoming the stability-activity trade-off is a key goal. Modern strategies include:

- Computational Rational Design: Using programs like RosettaDesign to identify mutations in the enzyme's core that optimize packing and stability without disturbing the active site [25].

- Directed Evolution: Screening large libraries of enzyme variants for those that retain activity after heat incubation, directly selecting for improved functional half-life [27].

- Increasing Active Site Rigidity: Targeting flexible residues near the active site for mutagenesis to reduce local fluctuations that lead to inactivation, which can improve kinetic stability (half-life) without reducing activity [24].

- Machine Learning-Guided Engineering: Using models trained on protein sequences and stability data to predict a minimal set of mutations that synergistically improve both stability and activity [4].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Metrics for Enzyme Thermostability

| Metric | Definition | Typical Measurement Methods | Information Provided | Industrial Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | The temperature at which 50% of the enzyme molecules are unfolded. | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy, Fluorescence-based thermal shift assays [23] [22]. | Point of major structural denaturation; thermodynamic stability. | High-throughput screening; indicator of structural robustness. |

| Half-life (t₁/₂) | The time required for the enzyme to lose 50% of its initial activity at a specific temperature. | Residual activity assays over time at a constant, elevated temperature [23] [25] [24]. | Functional stability over time; kinetic stability. | Directly predicts operational lifespan in a bioreactor or process. |

| T₅₀,₁₅ | The temperature at which the enzyme loses 50% of its activity after a 15-minute heat treatment. | Residual activity assay after short, high-temperature incubations [24]. | Resistance to short-term thermal shock. | Useful for processes involving brief, high-temperature steps (e.g., pasteurization). |

Table 2: Experimental Data from Enzyme Thermostabilization Studies

| Enzyme | Mutation(s) | Change in Tm (°C) | Change in Half-life | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Cytosine Deaminase (yCD) | A23L / I140L / V108I | +10 °C (from 52°C to 62°C) | 30-fold increase at 50°C (from ~4h to ~117h) | Unchanged | [25] |

| Candida antarctica Lipase B (CalB) | D223G / L278M | Not specified | 13-fold increase at 48°C | Not specified | [24] |

| Humicola insolens Cutinase (HiC) | 17 mutations (ML-guided) | Not specified | 3.9-fold increase after heat treatment | No reduction | [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Melting Temperature (Tm) Using a Fluorescent Dye

Principle: A fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) binds to hydrophobic regions of the protein as it unfolds upon heating, causing a increase in fluorescence [22].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dilute the purified enzyme to a final concentration of 0.1-0.5 mg/mL in a suitable buffer (e.g., 100 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5).

- Add SYPRO Orange dye to a final concentration of 1X-5X as recommended by the manufacturer.

- Instrument Setup:

- Use a real-time PCR instrument or a dedicated thermal shift instrument.

- Place the sample in a 96-well PCR plate. Include a buffer-only control with dye.

- Thermal Ramp:

- Set the temperature ramp from 20°C to 90°C with a slow, incremental increase (e.g., 0.2-1.0 °C per minute).

- Fluorescence readings (excitation ~470-530 nm, emission ~560-580 nm) are taken at each temperature increment.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot fluorescence intensity versus temperature.

- The Tm is determined as the temperature at the inflection point (midpoint) of the sigmoidal transition curve, often obtained from the first derivative peak [22].

Protocol 2: Determining Functional Half-life at an Elevated Temperature

Principle: The enzyme is incubated at a constant, elevated temperature, and samples are withdrawn at time intervals to measure residual activity [25].

Procedure:

- Heat Incubation:

- Pre-incubate a large volume of enzyme solution (in its operational buffer) in a thermostated water bath or thermal cycler at the desired temperature (e.g., 50°C).

- At time zero, withdraw an aliquot and immediately place it on ice. This is the "time zero" sample.

- Sampling:

- Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 hours) and transfer them immediately to ice.

- Activity Assay:

- Measure the catalytic activity of all samples (including the "time zero" sample) using a standard assay under optimal conditions (e.g., at 30°C).

- Data Analysis:

Experimental Workflow and Data Interpretation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Thermostability Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Fluorescent probe for thermal shift assays. Binds hydrophobic patches exposed during protein unfolding. | Used in real-time PCR machines for high-throughput Tm determination [22]. |

| HEPES Buffer | A common, non-reactive buffering agent for protein studies. | Used at 100 mM concentration with 150 mM NaCl for standardizing thermal melt assays [22]. |

| Glycerol / Trehalose | Chemical stabilizers that can protect enzymes from thermal denaturation. | Often added at 5-20% (v/v) to storage or reaction buffers to increase Tm and half-life [23]. |

| RosettaDesign Software | Computational protein design software for predicting stabilizing mutations. | Used for rational design by optimizing the protein sequence for a given fold [25]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | For generating specific point mutations in the enzyme gene. | Essential for creating variants predicted by rational design or other methods [25]. |

The Engineer's Toolkit: From Rational Design to AI-Guided Evolution

In the pursuit of enhancing enzyme thermostability for industrial processes, rational and semi-rational protein design have emerged as powerful strategies to overcome the limitations of natural enzymes. These approaches enable the precise engineering of protein rigidity and foldability—key determinants of an enzyme's ability to retain structure and function under high-temperature industrial conditions. By targeting specific amino acid residues that govern structural stability, researchers can develop robust biocatalysts that maintain activity in processes ranging from pharmaceutical synthesis to biofuel production, thereby improving efficiency and reducing operational costs [27] [28].

This technical support center addresses the specific experimental challenges researchers encounter when implementing these design strategies, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological frameworks to accelerate the development of thermostable industrial enzymes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What defines a 'key residue' for targeting in thermostability engineering?

Key residues are specific amino acid positions within a protein structure that disproportionately influence structural stability, dynamics, and the folding process. They can be systematically identified through several characteristic features:

- Folding Nuclei: A limited set of rigid residues, often forming a tight interaction network within the protein's core, that play a critical role during the folding process. These residues are highly conserved and can be predicted through coarse-grain simulations and sequence analysis [29].

- Dual-Function Residues: A small subset (approximately 2%) of residues that are involved in both structural stabilization and molecular binding, making them critical for maintaining both stability and function [30].

- Weak Sites: Regions with high flexibility or low geometric constraint, identified through high B-factor values from crystal structures or molecular dynamics simulations. Stabilizing these areas often enhances overall rigidity [27].

2. How do rational and semi-rational design approaches differ in their targeting of residues?

The core distinction lies in the use of prior structural knowledge and the subsequent library generation and screening requirements.

- Rational Design: This is a knowledge-driven approach. It requires a deep understanding of the protein's structure-function relationship. Researchers use computational tools to predict mutations that will enhance stability—for example, by engineering salt bridges, disulfide bonds, or optimizing surface charge. The outcome is a small, focused set of predicted beneficial mutations, making it a low-cost, targeted strategy [27] [31].

- Semi-Rational Design: This approach hybridizes rational and combinatorial elements. It uses structural and evolutionary knowledge to identify "hotspot" regions or residues (e.g., flexible loops near the active site) but then employs techniques like saturation mutagenesis to create a limited library of variants at those sites. This reduces the screening burden compared to fully random methods while still exploring sequence diversity beyond a few computationally predicted mutations [27] [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Rational and Semi-Rational Design Approaches

| Feature | Rational Design | Semi-Rational Design |

|---|---|---|

| Basis for Target Selection | Detailed structural/evolutionary knowledge & computational prediction [27] | Identification of "hotspot" regions based on structure/sequence, followed by local exploration [27] |

| Library Size | Small and focused | Medium-sized, focused on specific regions |

| Primary Methods | Computational tools (Rosetta, MD simulations, consensus design) [31] [32] | Saturation mutagenesis, iterative saturation mutagenesis (ISM) [31] |

| Screening Throughput | Low to medium | High-throughput screening (HTS) required [27] |

| Advantage | Cost-effective; minimal experimental screening [27] | Balances design efficiency with exploration of unforeseen beneficial mutations |

3. What are the most effective computational tools for identifying key residues?

A suite of software tools is available for predicting residues critical for stability:

- For Flexibility Analysis: Tools that analyze crystallographic B-factors or perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations can identify dynamic and flexible regions (weak sites) that are potential targets for stabilization [27].

- For Stability Prediction: Tools like Rosetta can calculate the change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation, helping to rank the stability of designed variants [4] [31].

- For Consensus Design: Generating a consensus sequence from a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of homologous proteins helps identify residues that are evolutionarily conserved for stability and function [32].

- For Tunnel/Channel Analysis: Software like CAVER can identify and analyze substrate access tunnels, allowing for engineering residues that influence substrate specificity and stability [31].

4. A common stability-activity trade-off occurs; how can it be mitigated?

The stability-activity trade-off, where enhancing rigidity compromises catalytic efficiency, is a central challenge. Advanced strategies to decouple this trade-off include:

- Targeting Remote Sites: Introducing mutations at residues that are structurally distant from the active site. This can optimize global rigidity and dynamics without directly disrupting the precise geometry of the active site [4].

- Machine Learning-Guided Design: Using models like the iCASE (isothermal compressibility-assisted dynamic squeezing index perturbation engineering) strategy. This method uses multi-dimensional conformational dynamics to predict mutations that can synergistically improve both stability and activity, as demonstrated with enzymes like xylanase and protein-glutaminase [4].

- Substrate Channel Engineering: Modifying residues in access tunnels (e.g., using CAVER) can improve substrate binding and product release without altering the core catalytic machinery, thereby maintaining activity while improving stability [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Success Rate in Identifying Beneficial Mutations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inaccurate Structural Model.

- Solution: If an experimental structure is unavailable, ensure homology models are built from templates with >30% sequence identity using tools like YASARA. Validate the model with checks for steric clashes and proper folding [31].

- Cause: Over-reliance on a Single Prediction Method.

- Cause: Ignoring Long-Range Epistatic Effects.

- Solution: A single mutation's effect can depend on the presence of other mutations (epistasis). Use structure-based supervised machine learning models that account for these higher-order genetic interactions to better predict the fitness of variants with multiple mutations [4].

Problem 2: Engineered Variants Exhibit Reduced Catalytic Activity

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Introduced Rigidity Compromises Essential Dynamics.

- Solution: Avoid over-stabilizing regions critical for catalysis, such as active site loops. Use the Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI) or similar metrics to target residues that modulate dynamics without freezing catalytically essential motions [4].

- Cause: Mutation Disrupts Critical Active Site Interactions.

- Solution: When designing near the active site, perform molecular docking to ensure mutations do not sterically hinder substrate binding or alter the transition state geometry. Prefer semi-rational saturation mutagenesis over a single rational mutation in these sensitive areas [31].

- Cause: Unintended Changes in Surface Charge or Polarity.

- Solution: Analyze the surface charge distribution of the wild-type and variant enzymes. A mutation that introduces a charged residue in an inappropriate context can disrupt substrate affinity or solubility [27].

Problem 3: Designed Enzyme Shows Insufficient Improvement in Thermostability

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Targeting Residues with Insufficient Structural Impact.

- Cause: Lack of Synergistic Mutations.

- Solution: Isolated single mutations often provide limited gains. Implement iterative strategies or use machine learning to design combinatorial mutations that have a supra-additive (positive epistatic) effect on stability [4].

- Cause: Aggregation at High Temperatures.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Consensus Design to Identify Stabilizing Mutations

This method uses evolutionary information to guide stability engineering [32].

- Sequence Collection: Gather a large and diverse multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of homologs of your target enzyme from public databases (e.g., UniProt, Pfam).

- Generate Consensus Sequence: Calculate the most frequent amino acid at each position in the MSA. This defines the consensus sequence.

- Target Selection: Identify positions where the wild-type sequence of your enzyme differs from the consensus residue.

- Prioritize Mutations: Focus on mutations where the consensus amino acid is more hydrophobic, has a higher propensity for secondary structure, or is known to form better internal packing (e.g., Ile, Leu, Val).

- Construct and Test: Synthesize the gene for the consensus variant or introduce specific consensus mutations into your wild-type gene. Express, purify, and assay for thermostability (e.g., by measuring melting temperature,

T_m) and activity.

Protocol 2: Semi-Rational Design using Saturation Mutagenesis

This protocol is ideal for exploring the functional space of a pre-identified hotspot residue [27] [31].

- Hotspot Identification: Select a target residue based on structural criteria (e.g., high B-factor in a flexible loop, position near the active site, or residue identified from consensus analysis).

- Library Design: Design primers to perform saturation mutagenesis at the codon of the target residue. This creates a library where the wild-type amino acid is replaced with all other 19 possibilities.

- Library Construction: Use standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., PCR-based mutagenesis) to build the variant library and clone it into an expression vector.

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Transform the library into a host strain and screen for improved thermostability. A common method is to assay for activity after a heat challenge (e.g., incubate cell lysates or colonies at an elevated temperature and then measure residual activity versus a non-heated control). Colorimetric or fluorescent assays are preferable for HTS [27].

- Hit Validation: Sequence positive clones and characterize the best hits in purified form to confirm enhanced thermostability (

T_m, half-life at process temperature) and determine kinetic parameters.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for choosing and implementing a rational or semi-rational design strategy for enzyme thermostability.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example / Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | A comprehensive platform for computational protein design. Used for predicting ΔΔG of mutations, de novo design, and optimizing active sites. | [31] [32] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS, YASARA) | Simulates protein motion to identify flexible regions (weak sites) and understand dynamic effects of mutations. | [27] [31] |

| CAVER Software | Analyzes and identifies tunnels and channels in protein structures for engineering substrate access and selectivity. | [31] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Laboratory kits for constructing specific point mutations or small libraries. | Foundation for creating variants [27] |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay Reagents | Colorimetric or fluorescent substrates enabling rapid activity screening of thousands of variants after heat challenge. | Critical for directed evolution and semi-rational design [27] |

| Thermal Shift Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Used in thermofluor assays to measure protein melting temperature (T_m), a key metric for thermostability. |

Standard for stability assessment [27] |

Core Concepts: Protein Language Models and High-Order Mutants

What are Protein Language Models (PLMs) and how do they relate to predicting high-order mutants?

Protein Language Models (PLMs), such as Pro-PRIME and ESM-2, are deep learning systems trained on millions of protein sequences to understand the "language" of proteins. Unlike traditional methods that struggle with predicting combinations of multiple mutations (high-order mutants) due to complex epistatic interactions, these AI models capture subtle patterns that allow them to forecast how multiple mutations will collectively impact enzyme properties like thermostability and activity [33] [34].

Epistasis refers to the non-additive effects when multiple mutations interact, meaning the effect of a mutation combination isn't simply the sum of individual mutations. This creates significant challenges for traditional protein engineering methods [33] [4]. PLMs address this by learning from evolutionary patterns and, when fine-tuned, can predict these complex interactions to identify optimal high-order mutants that enhance thermostability without costly trial-and-error experimentation [33] [35].

What makes Pro-PRIME particularly suited for thermostability engineering?

Pro-PRIME is a specialized PLM pre-trained on a dataset of optimal growth temperatures from 96 million bacterial strains. This multi-task learning approach allows it to capture temperature-related features in protein sequences, enabling it to assign higher scores to sequences with enhanced temperature tolerance. The model can be further fine-tuned with experimental data to dramatically improve its accuracy in predicting thermostability for specific enzyme engineering campaigns [33].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard workflow for using Pro-PRIME in enzyme thermostability engineering

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative process of using Pro-PRIME for enzyme engineering:

Detailed methodology: Pro-PRIME implementation for creatinase thermostability

A proven experimental protocol for implementing Pro-PRIME involves these key steps [33]:

Initial Data Collection

- Generate single-point mutants (e.g., 18 mutants for creatinase) using methods like site-saturation mutagenesis or phylogenetic analysis

- Characterize mutants for key thermostability parameters: melting temperature (Tm), half-life (t1/2) at target temperature, and relative activity compared to wild-type

- Include some low-order combinatorial mutants (double, triple, quadruple) if available to enhance model training

Model Fine-Tuning

- Use collected experimental data (Tm and relative activity) to fine-tune Pro-PRIME

- Create two prediction models: regression model for thermostability (Tm) and discriminant model for activity classification (>60% relative activity threshold)

- Validate model performance using cross-validation or hold-out test sets

Combinatorial Library Design & Prediction

- Input all possible combinations of beneficial single-point mutations into fine-tuned Pro-PRIME

- For 18 single-point mutants, this represents 262,144 possible combinations

- Filter predictions based on both thermostability improvement and maintained activity (>60% wild-type)

Experimental Validation & Iteration

- Select top-ranking predicted mutants for experimental testing

- Feed new experimental results back into model for further refinement

- Typically, 2-3 design cycles yield optimal high-order mutants

Workflow for industrial enzyme engineering with AI assistance

The following diagram expands on the integration of AI models like Pro-PRIME within a broader industrial enzyme engineering pipeline:

Technical Reference Tables

Key experimental parameters for AI-guided thermostability engineering

Table 1: Critical experimental parameters for successful Pro-PRIME implementation

| Parameter | Description | Typical Values/Measurement | Importance for Model Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | Temperature at which 50% of protein is unfolded | °C, measured via differential scanning fluorimetry | Primary stability metric for regression models |

| Half-life (t1/2) | Time for enzyme to lose 50% activity at target temperature | Hours/minutes at specific temperature | Functional stability assessment |

| Relative Activity | Catalytic efficiency compared to wild-type | Percentage of wild-type activity | Ensures thermostability improvements don't compromise function |

| Optimal Growth Temperature (OGT) | - | °C of host organism source | Pre-training feature for Pro-PRIME |

| Mutation Order | Number of amino acid changes in variant | Single, double, triple, etc. | Critical for capturing epistatic effects |

Performance comparison of AI-assisted protein engineering

Table 2: Efficiency comparison between traditional and AI-assisted enzyme engineering

| Engineering Aspect | Traditional Methods | AI-Assisted (Pro-PRIME) | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time for optimization | Months to years [36] | 2-4 weeks [37] [35] | 3-12x faster |

| Number of variants tested | 500-1000+ | ~65-500 [37] [35] | 2-15x fewer experiments |

| Success rate for combinatorial mutants | Low due to epistasis [33] | Up to 100% for thermostable designs [33] | Significant improvement |

| Maximum mutation order achievable | Typically 2-4 mutations | 13+ mutations demonstrated [33] | 3-6x higher complexity |

| Ability to capture epistasis | Limited, requires extensive testing | Accurately predicts sign and magnitude epistasis [33] | Superior predictive capability |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Data and Modeling Issues

What if I have limited experimental data for fine-tuning?

Pro-PRIME and similar PLMs are specifically designed for low-data scenarios. METL, another biophysics-based PLM, demonstrated the ability to design functional GFP variants when trained on only 64 examples [34]. Start with characterizing 20-50 well-chosen single-point mutants, ensuring they cover diverse positions and chemical properties. The pre-training on evolutionary data provides strong priors that require minimal fine-tuning data [34] [36].

How do I handle the stability-activity trade-off in predictions?

Set appropriate activity thresholds during filtering. In the creatinase study, mutants with >60% relative activity were considered acceptable, prioritizing stability gains while maintaining sufficient function [33]. You can also implement multi-objective optimization where the model jointly maximizes both stability and activity parameters, though this may require more sophisticated modeling approaches.

Why are my model predictions inaccurate for high-order mutants?

This typically indicates insufficient epistasis capture. Ensure your training data includes some low-order combinatorial mutants (double, triple) rather than only single-point mutations. The creatinase study successfully trained Pro-PRIME with 18 single-point mutants plus 22 double-point and 21 triple-point mutants before predicting higher-order combinations [33]. Also verify that your experimental measurements are consistent and high-quality, as noisy data significantly impacts model performance.

Experimental Implementation Issues

How many mutation sites should I include in combinatorial libraries?

For practical feasibility, limit initial combinatorial spaces to 15-20 beneficial single-point mutations. With 18 single-point mutants, Pro-PRIME successfully navigated 262,144 possible combinations [33]. Beyond 20 sites, computational requirements increase exponentially, though the model can still prioritize the most promising regions of sequence space.

What experimental validation rate should I expect?

AI-guided approaches typically achieve significantly higher success rates than traditional methods. The creatinase study reported 100% success (50/50 designed mutants showed improved thermostability) [33], while the autonomous engineering platform demonstrated 50-59% of initial variants performing above wild-type baseline [37]. Expect lower success rates when exploring more ambitious engineering goals or less characterized enzyme systems.

How do I integrate Pro-PRIME with existing biofoundry automation?

The platform described by [37] provides a reference architecture: implement modular workflows for DNA assembly, transformation, protein expression, and functional assays. Schedule instruments via integrated software (e.g., Thermo Momentum) and use a central robotic arm for physical integration. Each module should handle discrete steps like mutagenesis PCR, DpnI digestion, microbial transformations, and enzyme assays to enable robust operation and easy troubleshooting.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for AI-assisted enzyme engineering

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application Purpose | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Models | Pro-PRIME [33], ESM-2 [37], METL [34] | Stability and function prediction | Evolutionary pattern capture, temperature adaptation features |

| Experimental Data Platforms | iBioFAB [37], Design2Data [38] | Automated characterization | High-throughput data generation, standardized measurements |

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold Database [39], Rosetta [34] | Structural context and analysis | 200M+ predicted structures, biophysical simulations |

| Epistasis Modeling | EVmutation [37], Potts models [4] | Capturing mutation interactions | Co-evolutionary analysis, residue-residue interactions |

| Automation Equipment | Liquid handlers, colony pickers, plate readers | High-throughput experimentation | Robotic pipeline integration, continuous operation |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing the machine learning-based iCASE strategy for enzyme engineering.

FAQ 1: What is the iCASE strategy and how does it overcome the stability-activity trade-off in enzyme engineering?

The iCASE (isothermal compressibility-assisted dynamic squeezing index perturbation engineering) strategy is a machine learning-based framework designed to simultaneously improve both the thermostability and activity of industrial enzymes, effectively addressing the classic stability-activity trade-off. It constructs hierarchical modular networks for enzymes of varying complexity by identifying key regulatory residues outside the active site through multidimensional conformational dynamics analysis. The strategy employs a dynamic response predictive model using structure-based supervised machine learning to forecast enzyme function and fitness, demonstrating robust performance across different datasets and reliable prediction for epistasis (non-additive mutational effects). By focusing on dynamic response mechanisms among variants rather than static local interactions, iCASE reaches what the authors describe as "the peak of adaptive evolution" through structural response mechanisms [4].

FAQ 2: What are the common reasons for poor prediction accuracy in the machine learning models, and how can they be improved?

Poor prediction accuracy typically stems from three main issues:

- Insufficient Training Data: The model may not have enough experimentally validated variants to learn complex sequence-function relationships. Solution: Start with orthogonal design to select initial training points efficiently, as demonstrated in magnesium alloy optimization where only 10 initial observations were used [40].

- Inadequate Feature Representation: The numerical representations of protein sequences may not capture relevant structural and dynamic properties. Solution: Incorporate structure-based features like isothermal compressibility (βT) and Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI) rather than relying solely on sequence information [4].

- Ignoring Epistatic Effects: Linear models may miss higher-order genetic interactions. Solution: Implement nonlinear models like EVmutation or DeepSequence VAE that consider interactions among all residues [4].

For iterative improvement, establish a closed-loop system where the machine learning algorithm controls the experiment, gathers cost information, and uses this feedback to update its model parameters continuously [41].

FAQ 3: How should researchers select appropriate mutation sites when applying the iCASE strategy to a new enzyme?

Follow this structured approach for mutation site selection:

- Identify High-Fluctuation Regions: Calculate isothermal compressibility (βT) fluctuations across the enzyme structure to identify regions with high conformational flexibility [4].

- Apply Dynamic Squeezing Index: Calculate DSI values coupled with the active center, selecting residues with DSI > 0.8 (representing the top 20% of residues with the highest scores) [4].

- Prioritize Flexible Regions Near Active Site: Focus on flexible loops and secondary structure elements proximate to the substrate binding site, as these often influence activity modification [4].

- Predict Energetic Impacts: Use computational tools like Rosetta to calculate changes in free energy upon mutations (ΔΔG) and prioritize mutations with favorable energetics [4].

- Check Conservation: Perform multiple-sequence alignment to identify whether candidate sites are conserved; non-conserved sites often tolerate mutations better [4].

FAQ 4: What experimental validation steps are crucial after computational screening of enzyme variants?

After computational screening, implement this validation workflow:

- Express and Purify Single-Point Mutants: Begin with individual mutations to assess their specific contributions [4].

- Measure Activity and Stability: Determine specific activity and thermal stability (Tm) compared to wild-type enzyme [4].

- Combine Beneficial Mutations: Generate combinatorial mutants from positive single-point mutations [4].

- Evaluate Comprehensive Performance: Assess both activity enhancement and stability maintenance in combinatorial mutants, selecting variants that offer the best balance of improvements [4].

- Characterize Top Performers: Conduct detailed biochemical and structural analysis of the best-performing variants to understand mechanistic basis for improvements [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing iCASE Strategy for Enzyme Engineering

This protocol outlines the step-by-step methodology for applying the iCASE strategy to improve enzyme thermostability and activity, based on validated approaches from recent research [4].

Materials and Equipment

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation Software: GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD for conformational dynamics analysis

- Molecular Docking Tools: AutoDock Vina or similar for substrate-enzyme interaction studies

- Rosetta Software Suite: Version 3.13 or higher for free energy calculations (ΔΔG)

- Machine Learning Frameworks: TensorFlow or PyTorch for building predictive models

- Protein Expression System: Appropriate microbial host (E. coli, B. subtilis, etc.) for variant production

- Activity Assay Reagents: Substrate-specific detection reagents

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): For thermal stability measurements (Tm)

Method Details

Step 1: Conformational Dynamics Analysis

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations of the wild-type enzyme under relevant conditions (temperature, pH)

- Calculate isothermal compressibility (βT) fluctuations across all secondary structure elements

- Identify high-fluctuation regions (typically loops and specific α-helices/β-sheets) that show above-average βT values

- For protein-glutaminase, researchers identified α1 (amino acids 8-19), loop2 (amino acids 20-41), α2 (amino acids 42-55), and loop6 (amino acids 102-113) as high-fluctuation regions [4]

Step 2: Active Site Coupling Analysis

- Perform molecular docking of substrate or transition state analogs to identify active site residues

- Calculate Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI) values for all residues, focusing on coupling to the active center

- Select candidate residues with DSI > 0.8 (representing the top 20% of residues with highest scores)

- For xylanase engineering, this approach identified 13 candidate single-point mutations for experimental testing [4]

Step 3: Energetic Filtering

- Use Rosetta 3.13 to calculate changes in free energy (ΔΔG) for all candidate mutations

- Filter out mutations with predicted strongly destabilizing ΔΔG values

- Retain mutations with neutral or stabilizing predictions for experimental testing

Step 4: Machine Learning Model Implementation

- Train supervised machine learning models using structural features as input and experimentally determined stability/activity as output

- Use the model to predict fitness of novel variants before experimental testing

- Implement an active learning loop where newly characterized variants are added to the training set to improve model accuracy

Step 5: Experimental Validation

- Express and purify selected single-point mutants

- Measure specific activity and thermal stability (Tm) compared to wild-type

- Combine beneficial mutations to generate combinatorial variants

- For xylanase, the best triple-point mutant (R77F/E145M/T284R) showed a 3.39-fold increase in specific activity and a Tm increase of 2.4°C [4]

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Assisted Multi-Parameter Optimization

This protocol describes the general framework for optimizing multiple parameters using machine learning, adaptable for various biotechnology applications [40] [41].

Materials and Equipment

- Experimental Setup: Appropriate bioreactor or enzyme assay system

- Data Acquisition System: For automated data collection (e.g., National Instruments NI USB-6366)

- Machine Learning Packages: scikit-learn, XGBoost, or specialized Bayesian optimization libraries

- Parameter Control Interface: Software-controlled adjustable parameters (temperature, pH, substrate concentration, etc.)

Method Details

Step 1: Initial Experimental Design

- Use orthogonal design or other design-of-experiment methods to select initial parameter combinations

- For magnesium alloy optimization with four parameters, researchers used orthogonal design with 3 levels of each parameter to select 9 initial points [40]

- Measure performance metrics (e.g., enzyme activity, stability) for these initial conditions

Step 2: Model Training

- Train support vector regression (SVR) with radial basis function (rbf) kernel or other appropriate ML models on initial data

- Use cross-validation to assess model performance and avoid overfitting

Step 3: Iterative Optimization Loop

- Use the trained model to predict performance across parameter space

- Select next parameter combinations using acquisition functions (e.g., expected improvement, probability of improvement)