Enzymatic Biosensors: Advanced Bioreceptors for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzymatic biosensors, a cornerstone technology in biomedical research and drug development.

Enzymatic Biosensors: Advanced Bioreceptors for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzymatic biosensors, a cornerstone technology in biomedical research and drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and pharmaceutical professionals, it explores the foundational principles of enzyme-based biorecognition, from molecular interactions to device architecture. It details current methodologies, fabrication techniques, and diverse applications in therapeutic monitoring and diagnostics. The scope extends to critical challenges such as selectivity enhancement, interference management, and stability optimization, offering practical troubleshooting strategies. Finally, the article presents a comparative validation of enzymatic biosensors against other bioreceptor paradigms, evaluating their performance, commercial viability, and future potential in clinical and research settings.

The Core Principles of Enzymatic Bioreceptors: From Molecular Recognition to Sensor Architecture

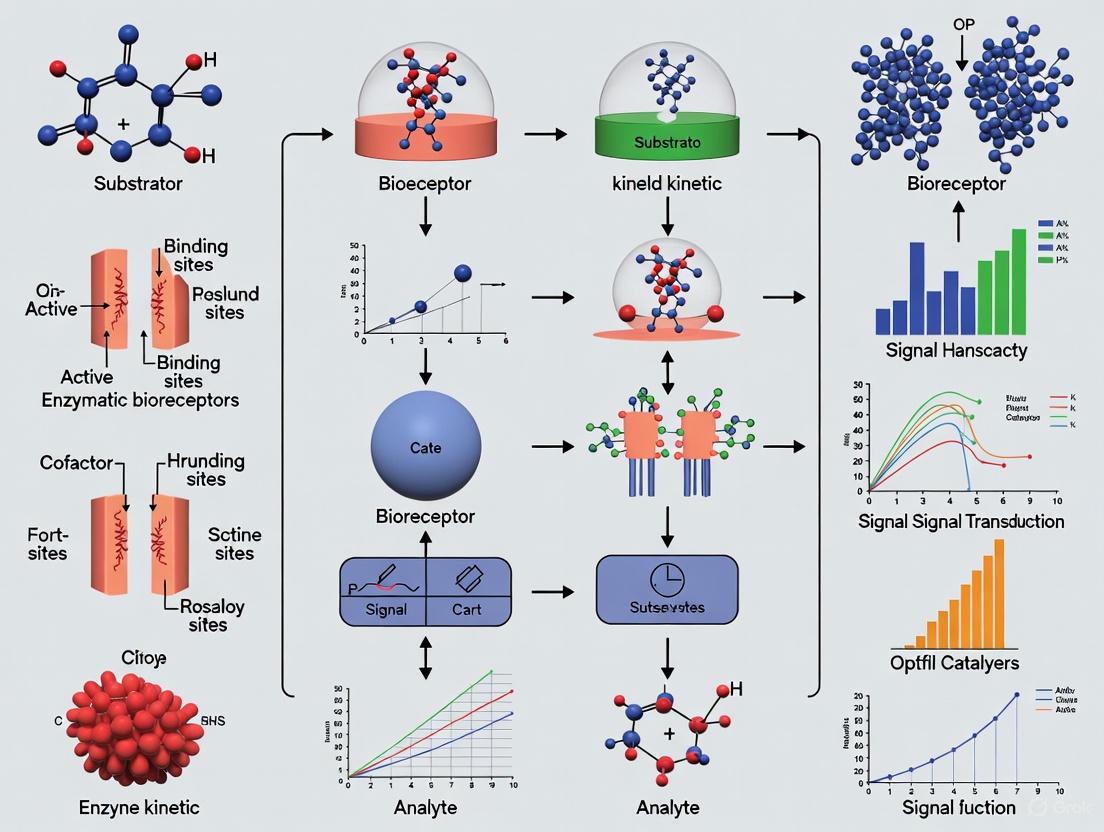

Enzymatic biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element, typically an enzyme, with a physicochemical transducer to detect target analytes with high specificity and sensitivity [1] [2]. These devices function by converting a biological response into an quantifiable electrical, optical, or thermal signal. The core of a biosensor's specificity lies in its biological recognition element (BRE), which dictates its classification into one of two primary mechanistic categories: biocatalytic or affinity-based [3] [2].

Biocatalytic biosensors utilize enzymes that act as biocatalysts, continuously converting a substrate into a product and generating a measurable signal in the process. In contrast, affinity-based biosensors rely on the specific binding of a target analyte to a biorecognition element, such as an antibody, aptamer, or engineered protein, without catalyzing a permanent chemical change in the analyte [3]. This article delineates the fundamental principles, components, and applications of these two distinct sensing mechanisms, providing a framework for their application in research and drug development.

Table: Core Characteristics of Biocatalytic and Affinity-Based Biosensors

| Feature | Biocatalytic Biosensors | Affinity-Based Biosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Element | Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, Urease) | Antibodies, Aptamers, ssDNA, Synthetic Receptors |

| Mechanism | Catalytic conversion of substrate | Selective binding and complex formation |

| Signal Generation | Consumption of substrate/formation of product | Change in mass, charge, or optical properties |

| Reusability | Often reusable due to catalyst regeneration | Typically single-use if binding is irreversible |

| Primary Application | Monitoring metabolites (e.g., glucose, lactate) | Detecting biomarkers, drugs, pathogens |

| Response Time | Typically fast (seconds to minutes) | Can be slower, depending on binding kinetics |

Fundamental Principles and Components

All enzymatic biosensors share a common architecture, comprising two fundamental components: a biorecognition layer and a transducer [1] [4].

The Biorecognition Layer

This layer houses the biological element that confers specificity to the sensor. In biocatalytic sensors, this involves immobilizing enzymes such as oxidoreductases or hydrolases on the transducer surface [1] [2]. Effective enzyme immobilization is critical for stability and reusability, achieved through methods like physical adsorption, covalent bonding, entrapment in gels or polymers, or incorporation into nanomaterials [1]. For affinity-based sensors, the layer is functionalized with capture agents like antibodies or aptamers that have high specificity for a target antigen or molecule [5] [3].

The Transducer

The transducer converts the biochemical interaction occurring at the biorecognition layer into a measurable analytical signal. Common transduction mechanisms include [1]:

- Electrochemical: Measures changes in electrical properties (current, potential, impedance). Amperometric sensors, which measure current from redox reactions, are the most prevalent, particularly in continuous glucose monitors [1] [6].

- Optical: Detects changes in light properties, such as absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, or surface plasmon resonance [7].

- Thermometric: Measures the heat absorbed or released during an enzymatic reaction [1].

- Photoelectrochemical (PEC): An emerging method where light excites a photoactive material, generating an electrical signal that is modulated by a biological binding event [3].

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow and logical decision process involved in configuring these two primary types of enzymatic biosensors.

The Biocatalytic Biosensing Mechanism

Biocatalytic biosensors leverage the inherent catalytic properties of enzymes. When the target analyte (substrate) interacts with its specific enzyme, a catalytic reaction occurs, leading to the formation of a product or the consumption of a co-substrate. This biochemical change is what the transducer detects and quantifies [1]. A quintessential and commercially triumphant example is the glucose biosensor, which uses the enzyme glucose oxidase (GOx) [2].

Signaling Pathways in Biocatalysis

The mechanism of a GOx-based amperometric biosensor demonstrates the principle elegantly. GOx catalyzes the oxidation of glucose to gluconolactone, while simultaneously reducing its innate cofactor, Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD). The reduced cofactor (FADH₂) must then be re-oxidized for the catalytic cycle to continue. The method of this re-oxidation defines the "generation" of the biosensor, each with distinct signaling pathways as shown below [1] [6].

Key Enzymes and Their Analytical Targets

A wide array of enzymes serves as robust biorecognition elements in biocatalytic biosensors for diverse applications.

Table: Key Enzymes Used in Biocatalytic Biosensors

| Enzyme | Target Analyte | Reaction Catalyzed | Primary Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Glucose | β-D-glucose + O₂ → Gluconic acid + H₂O₂ | Medical Diagnostics (Diabetes Management) [1] |

| Urease | Urea | Urea + H₂O → 2NH₃ + CO₂ | Medical Diagnostics (Kidney Function), Environmental Monitoring [1] |

| Lactate Oxidase (LOx) | Lactate | L-lactate + O₂ → Pyruvate + H₂O₂ | Sports Medicine, Critical Care [1] |

| Cholesterol Oxidase (ChOx) | Cholesterol | Cholesterol + O₂ → Cholest-4-en-3-one + H₂O₂ | Cardiovascular Health Monitoring, Food Science [1] |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Acetylcholine / Pesticides | Acetylcholine → Choline + Acetate | Environmental Monitoring (Pesticide Detection) [1] |

| Tyrosinase | Phenolic Compounds | Phenols → Quinones | Environmental Monitoring [1] |

The Affinity-Based Biosensing Mechanism

Affinity-based biosensors operate on a fundamentally different principle: molecular recognition without catalytic turnover. These sensors utilize biorecognition elements that form a stable, specific complex with the target analyte [3]. The binding event itself induces a physicochemical change—such as a shift in mass, charge, or refractive index—which is then detected by the transducer. This mechanism is ideal for detecting analytes for which no direct catalytic enzyme exists, such as specific proteins, DNA sequences, hormones, or entire pathogens [5].

Signaling Pathways in Affinity Sensing

A common strategy in affinity-based electrochemical sensors is the use of an electroactive reporter molecule. The biological binding event either modulates the access of this reporter to the electrode surface or alters the electron transfer efficiency, leading to a measurable change in current or potential [5]. Photoelectrochemical (PEC) readout is another sensitive method where biological binding modulates a photocurrent generated by a photoactive material [3]. The general workflow for a sandwich-style affinity immunosensor, a common format, is detailed below.

Key Biorecognition Elements in Affinity Biosensors

The selectivity of affinity-based biosensors is determined by the chosen biorecognition element. Each element offers a unique balance of specificity, stability, and production cost.

Table: Biorecognition Elements for Affinity-Based Biosensors

| Recognition Element | Description | Target Examples | Advantages & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | Immunoglobulins that bind to a specific antigen with high affinity. | Proteins, Hormones, Pathogens, Drugs [5] | Advantages: High specificity and affinity. Challenges: Can be sensitive to environment; irreversible binding limits reusability [2]. |

| Aptamers | Short, single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides selected for high-affinity binding. | Ions, Small molecules, Proteins, Cells [3] | Advantages: Chemical stability, reusability, ease of synthesis. Challenges: Selection process can be complex [3]. |

| Nucleic Acids (ssDNA) | Single-stranded DNA probes for complementary sequence hybridization. | DNA, RNA, Genetic Biomarkers [3] | Advantages: High predictability of interactions, design flexibility. Challenges: May require stringent hybridization conditions [3]. |

| Synzymes | Synthetic, engineered enzyme mimics. | Metabolites, Pollutants, Pharmaceuticals [8] | Advantages: Enhanced stability under harsh conditions, tunable catalytic properties. Challenges: Achieving high specificity can be challenging [8]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for establishing core assays for both biocatalytic and affinity-based biosensors, focusing on electrochemical transduction.

Protocol: Fabricating a Mediated (2nd Generation) Glucose Biosensor

This protocol outlines the steps to create a disposable amperometric glucose biosensor using a ferrocene-derived mediator [6].

5.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions Table: Essential Materials for Glucose Biosensor Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-based Electrode | Transducer platform | Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) are ideal for disposability. |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Biocatalytic recognition element | Lyophilized powder, ~150 U/mg. Store at -20°C. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent | 2.5% (v/v) solution in phosphate buffer. Use in a fume hood. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Stabilizing matrix | Provides a robust protein matrix for enzyme immobilization. |

| Ferrocene Carboxylic Acid | Artificial redox mediator | Shuttles electrons from FADH₂ to the electrode surface. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Electrolyte and dilution buffer | 0.1 M, pH 7.4. Provides a stable physiological environment. |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Resin | Permselective membrane | 5% solution. Prevents fouling and interference from large molecules [9]. |

5.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the working electrode surface of the SPCE by cycling the potential between 0.0 and +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference) in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Enzyme-Ink Preparation: In a microcentrifuge tube, mix 2 µL of GOx (50 mg/mL in PBS), 2 µL of BSA (50 mg/mL in PBS), 1 µL of ferrocene carboxylic acid (10 mM in DMSO), and 5 µL of PBS. Vortex gently to mix.

- Crosslinking and Immobilization: Add 1 µL of glutaraldehyde (2.5% v/v) to the enzyme-ink mixture and pipette to mix. Immediately deposit 5 µL of this mixture onto the active area of the pretreated working electrode.

- Membrane Casting: Allow the enzyme layer to cure for 30 minutes at room temperature. Then, dip-coat the entire electrode in a 0.5% Nafion solution and allow it to air dry for 15 minutes to form a thin, protective permselective membrane.

- Calibration and Measurement: Connect the biosensor to a potentiostat. In a stirred electrochemical cell containing 10 mL of 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4), apply a constant potential of +0.3 V vs. the onboard reference. Successively add known volumes of a concentrated glucose stock solution to achieve a desired concentration range (e.g., 0–20 mM). Record the steady-state current after each addition.

- Data Analysis: Plot the steady-state current as a function of glucose concentration. Perform linear regression to obtain the sensor's sensitivity (slope) and linear dynamic range.

Protocol: Developing an Affinity-Based Immunosensor for Protein Detection

This protocol describes the development of a sandwich-type amperometric immunosensor for detecting a model protein, such as Interlukin-6 (IL-6), in a processed sample [5].

5.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions Table: Essential Materials for Affinity Immunosensor

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Disk Electrode | Transducer platform | Provides a stable surface for antibody immobilization via thiol-gold chemistry. |

| Capture Anti-IL-6 Antibody | Primary biorecognition element | Monoclonal antibody specific for IL-6. |

| Reporter Anti-IL-6 Antibody | Secondary, signal-generating element | Monoclonal antibody conjugated to Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). Binds a different epitope. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Enzyme substrate | 10 mM solution in buffer, prepared fresh. |

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Electron donor for HRP | The reduced form of TMB (colorless) is oxidized by HRP/H₂O₂ to a product that can be electrochemically detected. |

| Ethanolamine | Blocking agent | 1 M solution, pH 8.5. Used to deactivate and block unreacted sites on the sensor surface. |

| NHS/EDC Coupling Kit | Chemistry for covalent immobilization | Standard kit for activating carboxyl groups on self-assembled monolayers for antibody coupling. |

5.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Functionalization: Clean the gold electrode according to standard protocols. Immerse it in a 2 mM solution of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (in ethanol) for 12 hours to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) with terminal carboxyl groups.

- Antibody Immobilization: Rinse the SAM-modified electrode and activate the carboxyl groups using a fresh mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS in water for 30 minutes. Rinse and incubate the electrode with a solution of the capture antibody (e.g., 50 µg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours. The antibody's amine groups will covalently attach to the activated surface.

- Surface Blocking: Incubate the electrode in 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 30 minutes to block any remaining activated ester groups, minimizing nonspecific binding.

- Antigen Incubation and Sandwich Formation: Expose the functionalized electrode to the sample containing the target antigen (IL-6) for 30 minutes. Wash thoroughly with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) to remove unbound material. Then, incubate with the HRP-conjugated reporter antibody solution for 30 minutes, followed by another wash step.

- Amperometric Detection: Transfer the electrode to an electrochemical cell containing PBS with 0.5 mM TMB. Apply a potential of -0.1 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) to monitor the reduction current of the oxidized TMB product generated by the HRP enzyme in the presence of 1 mM H₂O₂ (added to the cell just before measurement).

- Quantification: The magnitude of the cathodic current is proportional to the amount of captured HRP, which in turn is proportional to the concentration of the target antigen present in the sample. Generate a calibration curve using known standard concentrations.

Advanced Concepts and Future Perspectives

The convergence of materials science, nanotechnology, and enzyme engineering is pushing the boundaries of biosensing. Key advancements include:

- Wearable and Self-Powered Devices: The integration of biosensors into flexible substrates for wearable devices enables real-time, non-invasive health monitoring [4]. Enzymatic biofuel cells (EBFCs) can harness energy from bodily fluids like sweat, paving the way for self-sustaining, closed-loop diagnostic and therapeutic systems [4].

- Novel Materials and Transducers: The use of nanomaterials (graphene, carbon nanotubes, metal nanoparticles) enhances electron transfer, increases surface area for enzyme immobilization, and improves overall sensor sensitivity and stability [1] [4]. Photoelectrochemical (PEC) sensing is emerging as a highly sensitive alternative to traditional electrochemical methods [3].

- Addressing Selectivity Challenges: In complex matrices like whole blood, strategies such as the use of permselective membranes (e.g., Nafion/cellulose acetate composites), sentinel sensors (for background subtraction), and on-chip plasma separation membranes are critical to mitigate interference from electroactive species like ascorbic acid and uric acid [9] [5].

- Engineering Novel Biorecognition Elements: The development of synzymes (synthetic enzymes) offers catalysts with enhanced stability under extreme physicochemical conditions, suitable for applications in harsh industrial or environmental settings [8]. Furthermore, protein engineering aims to create oxidoreductases capable of Direct Electron Transfer (DET), which would simplify biosensor design and improve stability by eliminating the need for mediators or oxygen [2].

Enzyme-based biosensors represent a transformative technology in analytical science, leveraging the exceptional specificity and catalytic efficiency of enzymes for detecting target substances, or analytes. These devices integrate a biological recognition element (the enzyme) with a physicochemical transducer to convert a biochemical reaction into a quantifiable signal [1]. The core of this process, termed biorecognition, is the specific interaction between the enzyme and its target analyte. This interaction is the foundational "engine" of the biosensor, initiating a cascade that yields a measurable output proportional to the analyte's concentration. The high specificity of enzyme-analyte interactions ensures that even trace amounts of a target compound can be accurately identified in complex sample matrices like blood, urine, or environmental samples, making these biosensors indispensable in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety [1] [10].

The performance and reliability of a biosensor are governed by several key characteristics rooted in this biorecognition event. Selectivity is the most critical, referring to the bioreceptor's ability to detect a specific analyte in a sample containing other admixtures and contaminants [10]. Other vital attributes include sensitivity, which is the minimum amount of analyte that can be detected; reproducibility, the ability to generate identical responses for a duplicated experimental setup; and stability, the degree to which the sensor is susceptible to ambient disturbances over time [10]. The enzyme's intrinsic kinetic parameters, primarily the Michaelis-Menten constant ((Km)) and the turnover number ((k{cat})), directly influence these characteristics, defining the sensor's operational range, speed, and catalytic efficiency [11].

The Fundamentals of Enzyme-Analyte Interaction

Key Components of the Biorecognition System

The functionality of an enzyme-based biosensor is built upon three essential components that work synergistically.

Biological Recognition Element (Enzyme): The enzyme serves as the biocatalyst and is the source of the sensor's specificity. It initiates a reaction with its target substrate (analyte) to produce a detectable byproduct. Commonly used enzymes include glucose oxidase (GOx) for glucose monitoring, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) for pesticide detection, and urease for kidney function diagnostics [1].

Transducer: This element converts the biochemical signal from the enzyme-analyte reaction into a quantifiable electrical or optical signal. Several transducer types are employed, including electrochemical (amperometric, potentiometric), optical (fluorescence, absorbance), thermistor (detecting temperature change), and piezoelectric (detecting mass changes) [1].

Immobilization Matrix: To ensure the enzyme remains stable, active, and in proximity to the transducer, it is immobilized using various techniques. These include physical adsorption, covalent bonding, entrapment in gels or polymers, or incorporation into nanoparticles. The choice of immobilization method significantly affects the sensor's stability, reusability, and response time [1].

Kinetics of Biorecognition

The interaction between an enzyme (E) and its substrate/analyte (S) is quantitatively described by enzyme kinetics. The most fundamental model is the Michaelis-Menten mechanism, which involves the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex (ES) that subsequently decomposes to yield the product (P) and release the enzyme [11].

The mechanism is described by: [ E + S \underset{k{-1}}{\overset{k1}{\rightleftharpoons}} ES \overset{k_2}{\rightarrow} E + P ]

The rate of product formation ((v)) is given by the Michaelis-Menten equation: [ v = \frac{d[P]}{dt} = \frac{V{max} [S]}{Km + [S]} ] where:

- ( V_{max} ) is the maximum reaction rate (achieved when the enzyme is saturated with substrate).

- ( Km ) is the Michaelis constant, defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of ( V{max} ). It is a measure of the enzyme's affinity for the substrate; a lower ( K_m ) indicates a higher affinity [11].

- ( k{cat} ), the turnover number, is the number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time when the enzyme is fully saturated. It is related to ( V{max} ) by ( V{max} = k{cat} [E]0 ), where ( [E]0 ) is the total enzyme concentration [12].

The catalytic efficiency of an enzyme is given by the ratio ( k{cat}/Km ). Understanding these parameters is crucial for biosensor design, as they determine the sensor's operational range, limit of detection, and response time. The following workflow outlines the process from analyte binding to signal generation.

Quantitative Parameters of Enzyme-Substrate Interactions

The following table summarizes key kinetic parameters for enzymes commonly used in biosensing, compiled from structured datasets like SKiD which integrates experimental data from resources such as BRENDA [12].

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters of Common Enzymes Used in Biosensors

| Enzyme | EC Number | Target Analyte | kcat (s⁻¹) | Km (mM) | Assay Conditions (pH, Temp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | 1.1.3.4 | β-D-glucose | Varies by source; ~700 [12] | 20-30 [12] | pH 5.5-7.0, 25-37°C |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | 3.1.1.7 | Acetylcholine | Varies by source & type | ~0.1 (for acetylcholine) | pH 7.4-8.0, 25-37°C |

| Urease | 3.5.1.5 | Urea | ~4.0 x 10⁴ | ~5.0 | pH 7.0, 37°C |

| Lactate Oxidase (LOx) | 1.1.3.2 | L-lactate | Varies by source | ~0.2-1.0 | pH 7.0, 30°C |

| Cholesterol Oxidase (ChOx) | 1.1.3.6 | Cholesterol | Varies by source | ~0.05-0.15 | pH 7.0-7.5, 37°C |

Note: kcat and Km values are highly dependent on the enzyme source (species, tissue), immobilization method, and exact experimental conditions. The values presented are representative ranges. For rigorous experimental design, consult primary literature or curated databases like BRENDA or SKiD [12].

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments that leverage enzymatic biorecognition, from a standard calibration procedure to a cutting-edge technique for spatial mapping of enzyme activity within cells.

Protocol 1: Standard Calibration of an Amperometric Glucose Biosensor

Principle: Glucose oxidase (GOx) catalyzes the oxidation of β-D-glucose to gluconolactone and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). An amperometric transducer held at a constant potential (e.g., +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl) detects the H₂O₂ produced, generating a current proportional to the glucose concentration [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 2: Essential Materials for Glucose Biosensor Calibration

| Reagent/Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Biorecognition element; catalyzes the oxidation of glucose. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | (0.1 M, pH 7.4) Provides a stable ionic strength and pH for the enzymatic reaction. |

| D-Glucose Stock Solution | (1 M in PBS) Primary analyte for calibration. Store at 4°C. |

| Ferrocene or Ferricyanide | Optional electron mediators to shuttle electrons from GOx to the electrode, lowering operating potential. |

| Nafion or Polyurethane | Polymer membrane for enzyme immobilization and to reject interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid). |

Procedure:

- Biosensor Preparation: Immobilize GOx onto the working electrode surface. A common method is cross-linking: mix 5 µL of GOx solution (10 mg/mL in PBS) with 2 µL of a glutaraldehyde solution (2.5% v/v) and 3 µL of BSA (10 mg/mL). Spot this mixture onto the cleaned electrode surface and allow it to dry at 4°C for 1 hour.

- Apparatus Setup: Configure a potentiostat with a three-electrode system: the GOx-modified electrode as the working electrode, a Pt wire as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference. Set the applied potential to +0.6 V (or a lower potential if using a mediator).

- Calibration Curve Generation:

- Place the biosensor in a stirred electrochemical cell containing 10 mL of PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) at 25°C.

- Allow the background current to stabilize.

- Sequentially add small, known volumes of the 1 M glucose stock solution to achieve increasing concentrations in the cell (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0 mM).

- Record the steady-state current response after each addition.

- Data Analysis: Plot the steady-state current (µA) against the corresponding glucose concentration (mM). Perform linear regression on the data points within the linear range. The slope of this line represents the sensitivity of the biosensor (µA/mM).

Protocol 2: ProKAS for Spatial Mapping of Kinase Activity in Live Cells

Principle: The Proteomic Kinase Activity Sensors (ProKAS) technology uses barcoded peptides that mimic natural kinase substrates. When a kinase acts on its specific peptide, the incorporated barcode allows for the simultaneous detection of the kinase's activity and its spatial location within the cell via mass spectrometry [13]. This protocol provides an overview of the method.

Workflow Overview:

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Key Reagents for ProKAS Protocol

| Reagent/Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Barcoded Peptide Library | Engineered peptides with kinase-specific sequences and unique amino acid "barcodes" for spatial resolution. |

| Transfection Reagent | (e.g., Lipofectamine) For delivering peptides into live cells. |

| Cell Culture Components | Appropriate cell line, growth media, and reagents for drug stimulation (e.g., chemotherapeutic agents). |

| Lysis Buffer | RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors to preserve phosphorylation states. |

| Phospho-specific Antibody Beads | Anti-phospho-serine/threonine/tyrosine antibodies immobilized on beads for enriching phosphorylated peptides. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Liquid Chromatography coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry for peptide identification and quantification. |

Procedure:

- Peptide Library Design and Synthesis: Design a library of peptides that are specific substrates for the kinases of interest. Each peptide is tagged with a unique barcode sequence that corresponds to a specific subcellular location (e.g., nucleus, cytoplasm, membrane).

- Cell Transfection and Stimulation: Transfect the library of barcoded peptides into live cells using a standard transfection protocol. After allowing time for peptide distribution, subject the cells to an experimental stimulus (e.g., a DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic drug).

- Cell Lysis and Peptide Enrichment: At designated time points, lyse the cells. Use anti-phospho-amino acid antibody beads to immunoprecipitate and enrich the phosphorylated, barcoded peptides from the complex cellular lysate.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the enriched peptides by LC-MS/MS. The mass spectrometer identifies the phosphorylated peptides and sequences the barcodes.

- Data Processing and Spatial Mapping: Using computational tools, decode the barcode sequences to determine the subcellular location of each measured phosphorylation event. The intensity of the phosphopeptide signal corresponds to the level of kinase activity at that specific location and time [13].

Advanced Research and Data Integration

The field of enzymatic biosensing is being revolutionized by the integration of advanced data science and novel technologies. The creation of structured, comprehensive datasets is crucial for moving beyond empirical design. Resources like the Structure-oriented Kinetics Dataset (SKiD) are addressing a critical gap by mapping fundamental kinetic parameters ((k{cat}), (Km)) to the three-dimensional structures of enzyme-substrate complexes [12]. This allows researchers to understand the structural basis of enzymatic function and catalytic efficiency, facilitating the rational design of improved biocatalysts for biosensing applications [12].

Simultaneously, novel biosensor technologies like ProKAS are providing unprecedented insights into enzyme activity within its native cellular environment. This method overcomes the limitations of traditional microscopy-based techniques by using mass spectrometry to read the activity of multiple kinases simultaneously with high spatial and temporal resolution [13]. As noted by the developers, "We use mass spectrometry to read the activity, and this is a different approach to tracking kinase action in cells... The approach lets us follow multiple kinases at once and see exactly when and where they act inside cells" [13]. This capability is invaluable for pharmaceutical research, enabling the high-throughput screening of drug candidates and the elucidation of their mechanisms of action on kinase signaling pathways in disease processes [13].

Core Principles of Enzymatic Biosensors

Enzymatic biosensors are analytical devices that integrate a biological recognition element with a transducer to produce a measurable signal proportional to the concentration of a target analyte. These devices function based on a coherent framework of five essential components that work in sequence: the analyte, bioreceptor, transducer, electronics, and display [14].

The analyte is the substance of interest that the biosensor is designed to detect and quantify. In clinical and pharmaceutical contexts, typical analytes include glucose, lactate, cholesterol, urea, and specific biomarkers such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), a key indicator of liver function [15] [1]. The bioreceptor is a biological molecule that specifically interacts with the target analyte. In enzymatic biosensors, this is typically an enzyme like glucose oxidase, cholesterol oxidase, or pyruvate oxidase, which catalyzes a specific biochemical reaction involving the analyte [1] [14]. This interaction between the analyte and bioreceptor is termed biorecognition.

The transducer is a critical component that converts the biochemical response resulting from the biorecognition event into a quantifiable energy signal. Transducers can be electrochemical (amperometric or potentiometric), optical, thermal, or piezoelectric [1] [14]. The electronics unit processes this transduced signal, performing functions such as amplification, filtering, and conversion from analog to digital form. Finally, the display presents the processed data in a user-interpretable format, such as a numerical value, graph, or figure on a computer screen or digital readout [14].

Performance Evaluation of Enzymatic Systems

The analytical performance of enzymatic biosensors is critically dependent on the selection of the biorecognition element and the design of the transduction pathway. The table below summarizes key performance parameters for different enzyme-based biosensing systems, highlighting the trade-offs between sensitivity, detection range, and robustness.

Table 1: Performance comparison of enzyme-based biosensing systems for different analytes

| Target Analyte | Bioreceptor Enzyme | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Transduction Method | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (Liver Health) | Pyruvate Oxidase (POx) | 1–500 U/L [15] | 1 U/L [15] | Amperometric (H₂O₂) [15] | Higher sensitivity [15] |

| ALT (Liver Health) | Glutamate Oxidase (GlOx) | 5–500 U/L [15] | 1 U/L [15] | Amperometric (H₂O₂) [15] | Greater stability in complex solutions [15] |

| E. coli (Pathogen) | Anti-O Antibody (Immunosensor) | 10–10¹⁰ CFU mL⁻¹ [16] | 1 CFU mL⁻¹ [16] | Electrochemical (Impedance) [16] | Excellent selectivity and field applicability [16] |

| Cytokines (Inflammation) | Capture Antibody (Immunosensor) | Sub-picomolar [17] | Sub-picomolar [17] | Silicon Photonic Microring (Optical) [17] | Suited for complex, clinical matrices [17] |

The selection of an appropriate immobilization method is equally critical for sensor performance, as it directly impacts enzyme stability, activity, and leakage. Different techniques offer distinct advantages.

Table 2: Comparison of enzyme immobilization techniques in biosensors

| Immobilization Technique | Mechanism | Example Use Case | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrapment | Enzyme physically confined within a polymeric network [15] [1] | POx in PVA-SbQ photopolymer for ALT sensing [15] | Mild conditions, simple procedure [1] | Potential enzyme leaching, diffusion limitations [1] |

| Covalent Crosslinking | Enzyme chemically bonded to support matrix via crosslinkers (e.g., glutaraldehyde) [15] [1] | GlOx crosslinked with glutaraldehyde for ALT sensing [15] | Strong binding, minimal enzyme leakage [1] | Possible loss of enzyme activity due to harsh chemistry [1] |

| Physical Adsorption | Enzyme bound to surface via weak forces (van der Waals, ionic) [1] | Not specified in search results | Very simple and rapid [1] | Weak binding, prone to desorption [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of an Amperometric ALT Biosensor

This protocol details the construction of an amperometric biosensor for detecting Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT) using a Pyruvate Oxidase (POx)-based approach, adapted from a 2025 study [15].

Principle: ALT catalyzes the transamination of L-alanine and α-ketoglutarate to produce pyruvate and L-glutamate. Pyruvate is then oxidized by the immobilized Pyruvate Oxidase (POx), generating hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). H₂O₂ is electrochemically oxidized at a platinum electrode, and the resulting current is measured amperometrically [15].

Diagram 1: POx-based ALT detection principle.

Materials and Reagents:

- Pyruvate Oxidase (POx) from Aerococcus viridans (35 U/mg) [15]

- ALT from porcine heart (84 U/mg) [15]

- Polyvinyl alcohol with steryl pyridinium groups (PVA-SbQ) [15]

- HEPES buffer (25 mM, pH 7.4) [15]

- Glycerol and Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [15]

- Platinum disc working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, platinum counter electrode [15]

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the platinum disc working electrode with alumina slurry, rinse thoroughly with ethanol and distilled water, and dry under a nitrogen stream [15].

- Interference-Blocking Membrane: Electropolymerize a meta-phenylenediamine (m-PPD) membrane onto the clean Pt surface. Immerse the electrode in a solution of 5 mM m-PPD in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). Apply cyclic voltammetry between 0 V and 0.9 V (scan rate: 0.02 V/s) for 10-20 cycles. A stable voltammogram indicates complete surface coverage [15].

- POx Immobilization Gel Preparation: Prepare a mixture containing 10% glycerol, 5% BSA, and 4.86 U/µL POx in 25 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). Mix this gel thoroughly with a 19.8% PVA-SbQ photopolymer solution in a 1:2 ratio. The final mixture will contain approximately 1.62 U/µL POx and 13.2% PVA-SbQ [15].

- Enzyme Layer Deposition: Apply 0.15 µL of the final POx/PVA-SbQ mixture onto the surface of the m-PPD-modified Pt electrode. Immediately photopolymerize the layer under UV light (365 nm) for approximately 8 minutes until an energy dose of 2.4 J is delivered [15].

- Sensor Conditioning: Prior to measurements, rinse the biosensor 2-3 times for 3 minutes each in the working buffer (e.g., HEPES or phosphate buffer) to remove any loosely bound enzyme [15].

- Amperometric Measurement: Place the biosensor in a standard three-electrode cell with the appropriate counter and reference electrodes. Add the sample containing ALT and its substrates (L-alanine and α-ketoglutarate) to the cell. Apply a constant potential of +0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) and record the steady-state current generated by the oxidation of H₂O₂. The change in current is proportional to ALT activity [15].

Protocol 2: Silicon Photonic Microring Immunoassay for Protein Biomarkers

This protocol describes a quantitative, multiplexed sandwich immunoassay using silicon photonic microring resonators, a type of optical biosensor, for the detection of protein biomarkers like cytokines [17].

Principle: Target-specific capture antibodies are immobilized on the sensor surface. Binding of the target analyte (protein) followed by a biotinylated detection antibody and a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (SA-HRP) conjugate creates a complex. Enzymatic deposition of an insoluble product by HRP causes a measurable shift in the resonator's wavelength [17].

Diagram 2: Microring resonator sandwich immunoassay.

Materials and Reagents:

- Silicon photonic microring resonator array (e.g., from Genalyte, Inc.) [17]

- Capture antibody (≥ 0.25 mg/mL, amine-free buffer) [17]

- Biotinylated tracer (detection) antibody [17]

- Streptavidin-Horseradish Peroxidase (SA-HRP) conjugate [17]

- 4-chloro-1-naphthol (4-CN) precipitation substrate [17]

- Bissulfosuccinimidyl suberate (BS3) crosslinker [17]

- Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) [17]

- Assay Buffer: PBS with 0.5% BSA [17]

- Blocking Buffer: Commercial buffer like StartingBlock (PBS) or DryCoat stabilizer [17]

Procedure:

- Sensor Surface Silanization: Clean the sensor chip with acetone and isopropanol. Submerge the chip in a fresh 1% APTES solution in acetone for 4 minutes with mild agitation. Rinse sequentially with acetone and isopropanol for 2 minutes each [17].

- Capture Antibody Immobilization: Incubate the silanized sensor with a 5 mM solution of BS3 crosslinker (in 2 mM acetic acid) to activate the surface. After rinsing, spot the sensor with the capture antibody solution (in 2 mM acetic acid) using a robotic microarrayspotter for multiplexing. Allow the coupling reaction to proceed. Quench any remaining active esters with a buffer containing BSA [17].

- Assay Procedure:

- Analyte Binding: Incubate the functionalized sensor with the sample or protein standard solution to allow antigen binding to the capture antibody.

- Tracer Binding: Introduce the biotinylated tracer antibody to form the sandwich complex.

- Signal Enhancement: Incubate with SA-HRP conjugate, followed by the 4-CN substrate. The enzymatic conversion leads to the localized precipitation of an insoluble product on the sensor surface, amplifying the signal [17].

- Signal Detection and Analysis: Continuously monitor the resonance wavelength shift of each microring throughout the assay. The shift after the final enzymatic step is proportional to the target protein concentration in the sample. Generate a calibration curve using known standards for quantitative analysis [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful development and implementation of enzymatic biosensors rely on a set of critical reagents and materials. The following table details these key components and their specific functions within the biosensing system.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for enzymatic biosensor development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Pyruvate Oxidase (POx) | Bioreceptor for detecting pyruvate; generates H₂O₂ [15] | Used in ALT biosensors for liver health monitoring [15] |

| Glutamate Oxidase (GlOx) | Bioreceptor for detecting glutamate; generates H₂O₂ [15] | Used in ALT/AST biosensors; can be affected by AST activity [15] |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol-SbQ (PVA-SbQ) | Photocrosslinkable polymer for enzyme entrapment [15] | Used for POx immobilization; enables gentle UV-induced crosslinking [15] |

| Glutaraldehyde (GA) | Homobifunctional crosslinker for covalent enzyme immobilization [15] | Used for GlOx immobilization; creates stable bonds but requires controlled conditions [15] |

| meta-Phenylenediamine (m-PPD) | Monomer for electropolymerized interference-blocking membrane [15] | Forms a size-exclusion membrane on Pt electrodes to block ascorbic acid etc. [15] |

| Bissulfosuccinimidyl suberate (BS3) | Homobifunctional NHS-ester crosslinker for antibody immobilization [17] | Used to covalently attach capture antibodies to aminated sensor surfaces [17] |

| Streptavidin-HRP (SA-HRP) | Signal amplification conjugate in immunoassays [17] | Binds to biotinylated detection antibodies and catalyzes precipitation reaction [17] |

| Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) | Silane coupling agent for creating surface amine groups [17] | Primes silicon/silicon oxide surfaces for subsequent antibody immobilization [17] |

The development of enzymatic biosensors represents a cornerstone of modern analytical science, bridging fundamental biochemistry with practical applications across medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and drug discovery. At the heart of this field lies the Clark electrode, invented in the 1950s by Leland Clark, which established the fundamental principle of coupling biological recognition with physicochemical transduction [18] [10]. This pioneering technology not only solved the immediate challenge of measuring blood oxygen tension but unexpectedly laid the groundwork for the entire biosensor field [19]. The original Clark electrode employed a platinum surface to catalyze oxygen reduction according to the net reaction: O₂ + 4e⁻ + 4H⁺ → 2H₂O, with a semipermeable Teflon membrane isolating the electrode compartment to reduce fouling while allowing oxygen diffusion [18]. This clever design established the basic biosensor architecture that would subsequently be adapted for countless other analytes.

The evolution from the Clark electrode to contemporary enzymatic biosensors demonstrates how a fundamental sensing platform can be creatively adapted through different bioreceptors and transduction mechanisms. Clark himself demonstrated this potential in 1962 when he and Lyons created the first true biosensor by immobilizing glucose oxidase onto the oxygen-permeable membrane of his electrode, thereby coupling enzyme-catalyzed substrate conversion with electrochemical detection [18] [1]. This critical innovation established the template for subsequent enzymatic biosensors that now employ diverse enzymes including urease, lactate oxidase, cholesterol oxidase, acetylcholinesterase, and tyrosinase for detecting various analytes [1]. Modern research continues to refine these principles, addressing challenges such as enzyme instability, interference from complex matrices, and the need for portability through innovations in nanomaterials, synthetic enzymes, and miniaturization technologies [1].

The Clark Electrode: Mechanism and Historical Significance

Technical Operation and Components

The Clark electrode operates as a polarographic device that measures current generated by the electrochemical reduction of oxygen at a platinum cathode when a specific voltage is applied [19]. The key components and their functions are detailed in the following table:

Table 1: Core Components of the Clark Electrode and Their Functions

| Component | Material/Value | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cathode | Platinum | Serves as a catalytic surface for oxygen reduction; resistant to reaction with other compounds [19] |

| Anode | Silver/Silver Chloride | Provides a steady supply of electrons through the reaction: Ag → Ag⁺ + e⁻ [19] |

| Electrolyte Solution | Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Source of chloride ions to neutralize silver ions (Ag⁺ + Cl⁻ → AgCl) [19] |

| Membrane | Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) | Oxygen-permeable barrier that separates electrodes from sample; reduces fouling and metal plating [18] |

| Applied Voltage | 0.6V | Polarizes electrodes to drive oxygen reduction while minimizing interference from other reactions [19] |

The 0.6V operating voltage represents a critical "sweet spot" in the current-voltage relationship—sufficient to rapidly reduce all available oxygen without initiating competing reactions like water reduction that would occur above 1V [19]. This specific voltage ensures the reaction rate becomes limited by oxygen diffusion rather than applied potential, establishing a linear relationship between current and oxygen partial pressure [18] [19].

From Oxygen Detection to Glucose Sensing

The transition from oxygen measurement to glucose detection exemplifies the adaptability of the Clark electrode platform. The fundamental innovation involved immobilizing glucose oxidase (GOx) onto the oxygen-permeable membrane [18] [19]. This enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of glucose to gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide, consuming oxygen in the process. The subsequent decrease in oxygen tension detected by the underlying Clark electrode correlates directly with glucose concentration [18] [1]. This conceptual framework—using an enzyme to convert the target analyte into a measurable change in oxygen consumption—established the operational principle for countless subsequent enzyme-based biosensors.

Table 2: Evolution of Early Biosensor Technology

| Year | Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Clark Oxygen Electrode | First device to electrochemically measure oxygen in fluids; foundation for future biosensors [10] |

| 1962 | Clark and Lyons Glucose Biosensor | First true biosensor; introduced enzyme immobilization on electrode surface [18] |

| 1969 | Guilbault and Montalvo Potentiometric Urea Biosensor | Expanded biosensor concept to new enzymes and detection methods [10] |

| 1975 | First Commercial Glucose Biosensor (YSI) | Demonstrated commercial viability of biosensor technology [10] |

Modern Innovations in Enzymatic Biosensing

Advanced Sensing Platforms and Techniques

Contemporary enzymatic biosensing has evolved substantially from the original Clark electrode design, incorporating diverse transduction mechanisms including optical, thermal, and mass-sensitive detection alongside electrochemical methods [1]. The following table compares these modern biosensing approaches:

Table 3: Comparison of Modern Biosensor Transduction Mechanisms

| Transduction Type | Detection Principle | Example Enzymes | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric | Measures current from redox reactions [1] | Glucose oxidase, Lactate oxidase [1] | Continuous glucose monitoring, metabolite detection [1] |

| Potentiometric | Measures potential difference [1] | Urease [1] | Kidney function diagnostics, environmental monitoring [1] |

| Optical | Measures changes in light properties (absorbance, fluorescence) [20] | Tyrosinase, Cholesterol oxidase [1] | Phenolic compound detection, cholesterol measurement [1] |

| Mass-Sensitive (QCM, SAW) | Detects mass changes on sensor surface [20] | Various immobilized enzymes | Pathogen detection, toxin monitoring [20] |

| Thermal (Thermistor) | Measures heat from enzymatic reactions [1] | Enzyme-catalyzed exothermic reactions | Process monitoring, metabolic studies [1] |

ProKAS: A Case Study in Modern Innovation

A groundbreaking advancement in enzymatic biosensing is the recently developed Proteomic Kinase Activity Sensors (ProKAS) technology, which represents a complete reimagining of how kinase activity can be measured within living cells [13]. This innovative approach addresses a fundamental challenge in cell biology: mapping the spatial and temporal activity patterns of the more than 500 kinases that regulate nearly all cellular processes [13].

The ProKAS methodology employs:

- Barcoded Peptide Substrates: Engineered peptides that mimic natural kinase targets, each containing a unique amino acid "barcode" that marks its intracellular location [13].

- Mass Spectrometry Readout: Unlike traditional microscopy-based techniques, ProKAS uses mass spectrometry to detect both kinase action and the corresponding location barcode [13].

- High-Throughput Capability: The system can currently analyze 36 samples in a single 30-minute mass spectrometry run, with scalability to hundreds or thousands of samples [13].

Researchers have successfully implemented ProKAS to monitor DNA damage response kinases (ATR, ATM, CHK1) following anti-cancer drug treatment, revealing previously unmeasurable differences in kinase activity across specific nuclear regions [13]. This spatial resolution provides unprecedented insight into kinase signaling patterns relevant to drug mechanisms and disease processes, particularly in cancer [13].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Clark Electrode-Based Glucose Biosensor

Principle: Coupling glucose oxidase-mediated glucose oxidation with amperometric detection of oxygen consumption [18] [19].

Materials:

- Clark electrode system with platinum cathode and silver/silver chloride anode

- Oxygen-permeable Teflon membrane

- Glucose oxidase enzyme

- Cross-linking reagent (glutaraldehyde or similar)

- Buffer solution (phosphate buffer, pH 7.4)

- Standard glucose solutions for calibration

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Assemble Clark electrode with Teflon membrane ensuring secure fit.

- Enzyme Immobilization:

- Prepare glucose oxidase solution in appropriate buffer.

- Apply enzyme solution to Teflon membrane surface.

- Cross-link with glutaraldehyde vapor (0.5% v/v) for 30 minutes.

- Rinse thoroughly with buffer to remove unbound enzyme.

- System Calibration:

- Immerse electrode in oxygen-saturated buffer, apply 0.6V.

- Record baseline current (I₀).

- Add standard glucose solutions of known concentration.

- Record steady-state current (I) after each addition.

- Plot ΔI (I₀ - I) versus glucose concentration to establish calibration curve.

- Sample Measurement:

- Immerse biosensor in sample solution.

- Record steady-state current.

- Determine glucose concentration from calibration curve.

- Quality Control:

- Verify electrode response with standard between samples.

- Replace membrane and reimmobilize enzyme when sensitivity decreases >10%.

Technical Notes: Optimal enzyme loading is critical; excessive enzyme can hinder oxygen diffusion, while insufficient enzyme reduces sensitivity. The 0.6V operating potential must be maintained consistently to ensure oxygen reduction without side reactions [19].

Protocol 2: ProKAS for Kinase Activity Profiling

Principle: Using barcoded peptide substrates with mass spectrometry detection to map spatial kinase activity in live cells [13].

Materials:

- Library of barcoded peptide substrates with location-specific sequences

- Cell culture system of interest

- Lysis buffer compatible with mass spectrometry

- Mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization

- Anti-cancer drugs or other kinase modulators for treatment

- Solid-phase extraction columns for peptide cleanup

Procedure:

- Peptide Library Design:

- Design peptides mimicking natural kinase target sequences.

- Incorporate unique amino acid "barcodes" corresponding to specific subcellular locations.

- Synthesize and purify peptides to >95% purity.

- Cell Treatment and Incubation:

- Culture cells under appropriate conditions.

- Treat with kinase modulators (e.g., DNA-damaging agents for ATR/ATM studies).

- Introduce barcoded peptide library using optimized delivery method.

- Incubate for predetermined time (typically 15-60 minutes).

- Sample Processing:

- Lyse cells at specific time points.

- Isolate phosphorylated peptides using enrichment methods if necessary.

- Clean up samples using solid-phase extraction.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Separate peptides using liquid chromatography.

- Analyze using tandem mass spectrometry.

- Detect both phosphorylation status and location barcodes.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify phosphorylated peptides and their corresponding barcodes.

- Map kinase activity to specific cellular locations.

- Quantify temporal changes in activity patterns.

Technical Notes: The barcode system enables multiplexed analysis of multiple kinases and locations simultaneously. Kinase activity is quantified by normalizing phosphorylated peptide intensity to total peptide intensity for each barcode [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Enzymatic Biosensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biosensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Bioreceptors | Glucose oxidase, Lactate oxidase, Urease, Acetylcholinesterase [1] | Biological recognition elements that provide specificity through catalytic activity [1] |

| Immobilization Matrices | Chitosan, Polyacrylamide, Sol-gels, Nanoparticles [1] | Stabilize enzyme structure, maintain proximity to transducer, extend operational lifetime [1] |

| Transducer Materials | Platinum, Gold, Glassy carbon, Screen-printed electrodes [18] [1] | Convert biochemical signals into measurable electrical outputs [18] |

| Membrane Materials | Polytetrafluoroethylene, Polycarbonate, Cellulose acetate [18] | Control analyte diffusion, reduce interference, prevent fouling [18] |

| Nanomaterial Enhancers | Graphene, Carbon nanotubes, Metal nanoparticles, Nanozymes [1] | Increase surface area, enhance electron transfer, improve sensitivity and stability [1] |

| Signal Generation Systems | Hydrogen peroxide, Redox mediators (ferrocene), Fluorescent dyes [10] [1] | Amplify detection signals, enable different transduction mechanisms [10] |

Visualizing Biosensor Evolution and Mechanisms

Biosensor Technology Evolution Pathway

Clark Electrode Operational Mechanism

ProKAS Technology Workflow

Biosensor technology, which integrates a biological recognition element with a physicochemical transducer, has undergone significant evolution since its inception in the 1950s [21] [22]. This progression is categorized into three distinct generations, each marked by fundamental improvements in how the biological recognition event is translated into a measurable signal [21]. Enzymatic bioreceptors, particularly oxidoreductases like glucose oxidase, have been at the forefront of this development, serving as the foundational biological element from the first generation to the advanced direct electron transfer systems of the third generation [1] [2]. The global biosensor market is experiencing significant growth, driven by rising demand across medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety sectors [21] [23]. This application note, framed within broader thesis research on enzymatic biosensors, provides a structured comparison of biosensor generations, detailed experimental protocols for characterizing third-generation systems, and essential toolkit resources for researchers and drug development professionals.

Generational Evolution of Biosensors

The development of biosensors is categorized into three generations, primarily defined by the mechanism of signal transduction and the level of integration between the bioreceptor and the transducer [21] [22]. Table 1 provides a systematic comparison of the key characteristics across these generations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biosensor Generations

| Feature | First Generation (1960s-1970s) | Second Generation (1980s-1990s) | Third Generation (21st Century-Present) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Diffusion of reaction products to transducer [22] | Use of synthetic redox mediators [21] [2] | Direct electron transfer (DET) between enzyme and electrode [21] [2] |

| Signal Transduction | Mediator-less; measures O₂ consumption or H₂O₂ production [21] | "Enzyme-mediator-electrode" system [21] | Direct bioelectrocatalysis; no mediators needed [2] |

| Key Materials | Platinum black electrodes, polytetrafluoroethylene membranes [21] | Potassium ferricyanide, ferrocene [21] | Nanomaterials (graphene, CNTs), engineered enzymes, MOFs [21] [24] |

| Sensitivity Level | μM (micromolar) [21] | nM (nanomolar) [21] | Beyond fM (femtomolar) [21] |

| Detection Potential | Based on natural cosubstrates (e.g., O₂) [2] | Lowered potential (0.2–0.4 V) [21] | Intrinsic to the enzyme's redox center [2] |

| Primary Advantages | Simple concept, foundational technology | Improved sensitivity, reduced interference from sample matrix | High sensitivity, selectivity, miniaturization, ideal for in vivo sensing [21] [2] |

| Inherent Limitations | Low sensitivity, weak anti-interference ability | Potential mediator toxicity, complexity [21] [2] | Limited availability of native DET-capable enzymes [2] |

The first generation, exemplified by Clark's oxygen electrode, relied on the natural diffusion of reactants and products, such as oxygen consumption or hydrogen peroxide production, to the transducer surface [21] [22]. The second generation introduced synthetic redox mediators (e.g., ferrocene) to shuttle electrons between the enzyme's active site and the electrode, which lowered the operating potential and reduced interference, thereby enhancing sensitivity [21]. The current third generation represents the most advanced class, where the enzyme directly exchanges electrons with the electrode material without mediators, enabling superior selectivity, miniaturization, and stability [21] [2]. This direct electron transfer is considered the ideal principle for continuous in vivo monitoring applications, such as implantable glucose sensors [2].

Experimental Protocols for Third-Generation Biosensor Characterization

This section outlines a detailed methodology for fabricating and characterizing a third-generation enzymatic biosensor, using a glucose biosensor based on a fusion protein of glucose dehydrogenase and a cytochrome domain as a model system.

Fabrication of a Direct Electron Transfer (DET)-Capable Bioelectrode

Principle: The objective is to immobilize an engineered oxidoreductase enzyme capable of DET onto a nanostructured electrode surface, facilitating unmediated electron transfer [2].

Materials:

- Working Electrode: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter) or gold electrode.

- Nanomaterial Modification: Graphene oxide (GO) dispersion (1 mg/mL in deionized water) or a suspension of platinum nanoparticles (PtNPs) [25] [24].

- Bioreceptor: Purified fusion protein of PQQ-glucose dehydrogenase (PQQ-GDH) with a Shewanella cytochrome domain [2].

- Crosslinker: Poly(ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether (PEGDGE).

- Buffers: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4).

Procedure:

- Electrode Pre-treatment:

- Polish the GCE sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry under a nitrogen stream.

- Electrochemically clean by performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ from -0.2 V to +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable CV profile is obtained.

Nanomaterial Modification:

- Deposit 8 μL of the GO dispersion onto the polished surface of the GCE.

- Allow the electrode to dry overnight at room temperature under a dust-free atmosphere.

- Electrochemically reduce the GO to conductive reduced graphene oxide (rGO) by performing 10 cycles of CV in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) between 0 V and -1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s [24].

Enzyme Immobilization:

- Prepare an immobilization mixture containing 5 μL of the PQQ-GDH-cytochrome fusion protein (2 mg/mL) and 1 μL of PEGDGE crosslinker.

- Deposit 6 μL of this mixture onto the rGO-modified GCE surface.

- Allow the bioelectrode to cure for 24 hours at 4°C in a humidified chamber to prevent drying.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key fabrication steps:

Figure 1. Third-Generation Biosensor Fabrication Workflow.

Electrochemical Characterization and Performance Validation

Principle: Confirmation of successful DET is achieved by observing a redox couple in the cyclic voltammogram that is dependent on the enzyme's intrinsic cofactors and is stable over successive scans. The analytical performance is then validated by measuring the amperometric response to glucose additions [2].

Materials:

- Electrochemical Setup: Potentiostat, three-electrode system (fabricated biosensor as working electrode, Pt wire as counter electrode, Ag/AgCl as reference electrode).

- Analyte: D-Glucose stock solution (1 M) in deoxygenated PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4).

Procedure:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for DET Confirmation:

- Immerse the fabricated biosensor in a stirred electrochemical cell containing 10 mL of deoxygenated PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4).

- Record CV scans between -0.6 V and +0.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s, both in the absence and presence of 10 mM glucose.

- Expected Outcome: A well-defined, quasi-reversible redox couple appears, corresponding to the direct electron transfer of the enzyme's cytochrome center. The oxidation and reduction peak currents should increase proportionally with the addition of glucose, confirming bioelectrocatalytic activity.

Amperometric Sensitivity and Linear Range Determination:

- Apply a constant potential corresponding to the formal potential of the observed redox couple (typically between -0.3 V and -0.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl for PQQ-enzymes).

- Under continuous stirring, successively add small volumes of the D-glucose stock solution to achieve cumulative concentration increases in the range of 0.1 to 30 mM.

- Record the current response until a stable signal is achieved after each addition.

- Plot the steady-state current versus glucose concentration. The slope of the linear portion of this plot represents the sensitivity of the biosensor (e.g., in µA mM⁻¹ cm⁻²) [25].

Control Experiment:

- Repeat the amperometric measurement using a control electrode fabricated without the enzyme or with a denatured enzyme. This validates that the observed signal is due to the specific catalytic activity of the immobilized enzyme.

The signaling pathway of a third-generation biosensor can be visualized as follows:

Figure 2. Direct Electron Transfer Signaling Pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and fabrication of advanced third-generation biosensors rely on a specific set of materials and reagents. Table 2 details key components for research and development in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Third-Generation Biosensor Development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene/GO/rGO | Nanostructured electrode material [24] | High electrical conductivity, large surface area, facilitates DET [24] |

| Platinum Nanoparticles (PtNPs) | Electrode nanomodifier [25] | High catalytic activity, enhances electrode surface area and signal [25] |

| PQQ-Glucose Dehydrogenase | Model oxidoreductase enzyme | Oxygen-independent, suitable for mediatorless or DET systems [2] |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether (PEGDGE) | Crosslinking agent | Forms stable covalent bonds for robust enzyme immobilization [2] |

| Fusion Proteins (e.g., GDH-Cytochrome) | Engineered bioreceptor [2] | Genetically designed to enable or enhance Direct Electron Transfer [2] |

| Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) | Technology for generating nucleic acid aptamers [26] | Produces synthetic bioreceptors for targets where enzymes are unavailable [26] |

The evolution from first to third-generation biosensors represents a paradigm shift towards more direct, efficient, and robust analytical devices. Third-generation biosensors, characterized by their direct electron transfer mechanism, offer unparalleled advantages in sensitivity, selectivity, and miniaturization, making them ideal for advanced applications in continuous health monitoring, precise drug development analytics, and environmental sensing [21] [2]. The successful implementation of these systems hinges on the synergistic combination of engineered enzymes, advanced nanomaterials like graphene, and sophisticated fabrication protocols. While challenges remain, particularly in expanding the library of naturally DET-capable enzymes through protein engineering [2], the future of biosensing is firmly rooted in the principles of third-generation technology. The ongoing integration of these biosensors with wearable platforms, microfluidics, and artificial intelligence promises to further revolutionize diagnostic and monitoring capabilities across diverse fields [23] [22].

Fabrication and Deployment: Engineering Enzymatic Biosensors for Real-World Applications

Enzyme immobilization is a cornerstone technology in the development of enzymatic biosensors, which are critical tools in medical diagnostics, food safety monitoring, and environmental analysis [1]. Immobilization refers to the confinement of enzymes to a solid support or within a distinct spatial region, thereby restricting their mobility while retaining their catalytic activity [27]. This process is vital for enhancing the stability, reusability, and functionality of enzymatic bioreceptors within a biosensor setup [28] [29]. The selection of an appropriate immobilization technique directly influences key biosensor performance metrics, including sensitivity, selectivity, operational stability, and shelf life [30]. This document provides a detailed overview of four primary immobilization methods—cross-linking, entrapment, adsorption, and covalent bonding—framed within the context of biosensor research and development.

Comparative Analysis of Immobilization Techniques

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of the four main immobilization techniques, providing a guide for selecting the optimal method based on specific biosensor requirements.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Enzyme Immobilization Techniques for Biosensors

| Technique | Mechanism of Binding/Confinement | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Impact on Biosensor Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption [28] [29] [27] | Weak forces (Van der Waals, electrostatic, hydrophobic) | Simple, inexpensive, minimal enzyme modification, high activity retention [29]. | Enzyme leakage due to weak bonds, sensitive to pH/ionic strength changes, non-specific adsorption [28] [29] [27]. | Low operational stability; suitable for short-term or disposable sensors. |

| Covalent Bonding [31] [28] [29] | Strong covalent bonds between enzyme and activated support | High stability, no enzyme leakage, strong binding, reusable, good operational stability [31] [29]. | Complex process, risk of enzyme denaturation, potential activity loss, requires specific functional groups [28] [29]. | Excellent long-term and storage stability; ideal for reusable biosensors. |

| Entrapment [28] [29] [32] | Enzyme physically confined within a porous polymer or gel matrix | Protects enzyme from harsh environments, high enzyme loading, minimal chemical modification [28] [32]. | Diffusion limitations for substrate/product, possible enzyme leakage, mass transfer resistance [28] [29]. | Response time may be slower; useful for protecting enzymes in complex samples. |

| Cross-linking [28] [30] | Enzyme molecules linked to each other via bifunctional reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde) | Strong, stable enzyme aggregates, no solid support needed (carrier-free) [28]. | Risk of significant activity loss, can be combined with other methods for stability [28] [30]. | Can enhance rigidity and lifetime when used as a supplement to other methods. |

Detailed Protocols for Enzyme Immobilization

The following sections provide detailed, step-by-step protocols for implementing each immobilization technique in a biosensor development context.

Protocol for Adsorption Immobilization

Adsorption is one of the simplest and most straightforward methods for immobilizing enzymes onto a transducer surface [27]. The following protocol describes the Layer-by-Layer (LbL) electrostatic adsorption technique for creating a multi-layered, sensitive biosensor surface.

Workflow: Layer-by-Layer Adsorption

Materials:

- Support/Electrode: Gold, platinum, or carbon electrode.

- Polyelectrolytes: Polycation (e.g., Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) - PDDA, Chitosan) and Polycation (e.g., Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) - PSS) solutions at 1-2 mg/mL in a suitable buffer (e.g., 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.0) [27].

- Enzyme Solution: Target enzyme (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, Acetylcholinesterase) dissolved in a compatible, low-ionic-strength buffer (typically 0.5 - 2 mg/mL) to maximize electrostatic interactions [27] [30].

- Washing Buffer: Same buffer as used for enzyme and polyelectrolyte solutions.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean the transducer surface (e.g., electrode) thoroughly with solvents and water, followed by plasma cleaning or chemical etching to ensure a uniform surface charge [27].

- First Layer Deposition: Immerse the substrate in the polyelectrolyte solution with the opposite charge for 15-20 minutes to form the first layer.

- First Rinse: Remove the substrate and rinse it gently but thoroughly with washing buffer for 1-2 minutes to remove any loosely adsorbed polyelectrolyte molecules.

- Enzyme Layer Deposition: Immerse the substrate into the enzyme solution for 15-30 minutes. The enzyme, bearing a net charge opposite to the first layer, will adsorb onto the surface.

- Second Rinse: Rinse the substrate again with washing buffer to remove unadsorbed enzymes.

- Layer Buildup: Repeat steps 2-5, alternating between polyelectrolyte and enzyme solutions, until the desired number of enzyme layers is achieved.

- Final Processing: Gently dry the fabricated biosensor under a stream of nitrogen or air and store at 4°C in a dry environment until use.

Protocol for Covalent Bonding Immobilization

Covalent bonding provides a stable, leak-proof connection between the enzyme and the support, making it one of the most widely used methods for developing robust biosensors [31] [29]. This protocol outlines the carbodiimide chemistry approach for creating amide bonds between enzyme amino groups and support carboxyl groups.

Workflow: Covalent Immobilization via Carbodiimide Chemistry

Materials:

- Activation Reagents:

- EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide): A zero-length crosslinker that activates carboxyl groups. Concentration: 2-10 mg/mL in 50-100 mM MES buffer, pH 4.5-6.0 [31].

- NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide): Often used with EDC to form a more stable amine-reactive ester intermediate, improving immobilization efficiency. Concentration: 2-10 mg/mL [31] [29].

- Coupling Buffer: A non-amine buffer such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.0-7.4).

- Enzyme Solution: Prepared in the coupling buffer (typically 0.1-1 mg/mL).

- Quenching Agent: 1 M Ethanolamine (pH 8.5) or 1% (w/v) Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) solution to block any remaining activated esters.

- Washing Buffers: MES buffer (pH 6.0) and coupling buffer.

Procedure:

- Support Activation: Incubate the carboxyl-functionalized support (e.g., graphene oxide, functionalized polymer) with the EDC/NHS solution in MES buffer for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. This step forms an amine-reactive NHS ester on the support.

- Wash: Rinse the activated support thoroughly with MES buffer to remove excess EDC and NHS.

- Enzyme Coupling: Immediately transfer the activated support to the enzyme solution. Incubate for 2-4 hours at room temperature (or overnight at 4°C) with gentle agitation to allow covalent bond formation between the enzyme's amino groups (e.g., lysine residues) and the activated support.

- Wash: Rinse the biosensor construct with coupling buffer and then with a high-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.5 M NaCl) to remove any electrostatically adsorbed enzymes.

- Quenching: Incubate the biosensor with the quenching solution for 1 hour to deactivate any remaining reactive groups and minimize non-specific binding.

- Final Wash and Storage: Perform a final wash with storage buffer (e.g., 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4). The biosensor can be stored wet at 4°C.

Protocol for Entrapment Immobilization

Entrapment involves encapsulating enzymes within a porous polymer network, allowing substrates and products to diffuse while retaining the larger enzyme molecules [28] [32]. This protocol details enzyme entrapment within a silica sol-gel matrix.

Workflow: Enzyme Entrapment via Sol-Gel Method

Materials:

- Precursor: Tetramethyl orthosilicate (TMOS) or Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS).

- Hydrolysis Solution: Dilute hydrochloric acid (e.g., 1 mM HCl).

- Enzyme Solution: Prepared in a weak, neutral buffer (e.g., 10 mM PBS, pH 7.0) to avoid interference with the sol-gel chemistry.

- Hydration/Storage Buffer: 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4.

Procedure:

- Precursor Hydrolysis: Mix the silica precursor (e.g., TMOS) with the hydrolysis solution (acidified water) in a molar ratio of approximately 1:4 to 1:16 (TMOS:Water). Stir the mixture vigorously for 30-60 minutes at room temperature until it becomes a clear, homogeneous solution.

- Enzyme Incorporation: Cool the hydrolysate on ice to slow the gelation process. Gently mix the cooled hydrolysate with the enzyme solution in a 1:1 to 2:1 (v/v) ratio using a vortex mixer. Avoid vigorous stirring to prevent enzyme denaturation and foam formation.

- Casting: Quickly deposit small aliquots (5-20 µL) of the enzyme-hydrolysate mixture onto the clean transducer surface.

- Gelation and Aging: Allow the cast film to stand undisturbed at room temperature for 12-24 hours to complete the gelation process and form a rigid, porous silica network with the enzyme trapped inside.

- Hydration: Soak the solidified gel-modified biosensor in a neutral buffer for several hours to hydrate the matrix, prevent cracking, and allow the enzyme to assume its active conformation.

- Storage: Store the biosensor in buffer at 4°C to maintain hydration and enzyme activity.

Protocol for Cross-Linking Immobilization

Cross-linking (CL) uses bifunctional reagents to create covalent bonds between enzyme molecules, forming stable enzyme aggregates [28] [30]. It is often used in combination with other methods (e.g., adsorption or entrapment) to prevent enzyme leakage, a method known as cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEA).

Workflow: Preparing Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs)

Materials:

- Cross-linking Agent: Glutaraldehyde (GTA) is the most common, typically used as a 0.5-2.0% (v/v) solution in a neutral buffer [28] [29] [30].

- Precipitant: Saturated ammonium sulfate solution, or water-miscible organic solvents like acetone or t-butanol.

- Enzyme Solution: Prepared in a suitable buffer (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0).

- Washing Buffer: Dilute buffer or water.

Procedure:

- Precipitation/Aggregation: While stirring the enzyme solution, slowly add a precipitant (e.g., cold acetone or saturated ammonium sulfate) until the solution becomes turbid, indicating the formation of enzyme aggregates.

- Cross-Linking: Add the glutaraldehyde solution dropwise to the suspension of enzyme aggregates. Continue stirring slowly for 2-4 hours at 4°C to allow for extensive cross-linking.

- Washing: Recover the cross-linked aggregates by centrifugation. Wash the pellet repeatedly with washing buffer to remove any unreacted glutaraldehyde and precipitant.

- Integration into Biosensor: The resulting CLEAs can be re-suspended in a small volume of buffer and deposited onto the transducer surface, often followed by entrapment within a secondary polymer matrix or membrane to secure them in place.

- Storage: The CLEA-modified biosensor can be stored wet at 4°C or the CLEAs can be lyophilized for long-term storage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials required for executing the immobilization protocols described in this document.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde (GTA) | Bifunctional cross-linker for covalent bonding and cross-linking methods [29] [30]. | Typically used as 0.5-2.0% (v/v) solution. Caution: High concentrations can lead to excessive rigidity and activity loss. |

| EDC & NHS | Carbodiimide chemistry reagents for activating carboxyl groups for covalent bonding [31] [29]. | EDC is unstable in aqueous solution; prepare fresh. NHS stabilizes the intermediate, improving yield. |