Enzyme Engineering Methodologies: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Machine Learning, Directed Evolution, and High-Throughput Approaches

This article provides a critical evaluation of modern enzyme engineering methodologies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Enzyme Engineering Methodologies: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Machine Learning, Directed Evolution, and High-Throughput Approaches

Abstract

This article provides a critical evaluation of modern enzyme engineering methodologies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of enzyme engineering, examines cutting-edge methodological approaches including machine learning and directed evolution, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents rigorous validation frameworks for comparative analysis. By synthesizing insights from recent high-impact studies and emerging technologies, this review serves as a comprehensive resource for selecting appropriate engineering strategies to develop biocatalysts with enhanced properties for biomedical, industrial, and therapeutic applications.

The Enzyme Engineering Landscape: Core Principles and Evolutionary Frameworks

Enzyme engineering represents a pivotal frontier in biotechnology, dedicated to overcoming the inherent limitations of natural enzymes for industrial applications. Native biocatalysts, while efficient in their physiological contexts, often lack the robust stability, substrate specificity, or catalytic efficiency required for commercial-scale processes in pharmaceuticals, biofuel production, and sustainable chemistry [1]. The field has evolved significantly from traditional random mutagenesis to sophisticated methodologies that integrate computational intelligence and high-throughput experimental biology. This guide objectively compares the dominant enzyme engineering paradigms, providing a detailed analysis of their experimental protocols, performance outcomes, and practical implementation requirements to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

The imperative for advanced enzyme engineering stems from critical industrial challenges. Naturally occurring enzymes frequently demonstrate insufficient activity under process conditions, vulnerability to harsh industrial environments (extreme pH, temperature, organic solvents), and limited substrate scope for non-natural compounds [1]. Pharmaceutical applications particularly demand high enantioselectivity and product yield for economic viability. Engineering approaches aim to systematically address these limitations through targeted modifications of enzyme structure and function, bridging the gap between natural catalysis and industrial requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Engineering Methods

Contemporary enzyme engineering employs three primary strategies: rational design, directed evolution, and the emerging machine learning (ML)-guided framework. Each approach offers distinct mechanisms for navigating the vast protein sequence space to identify variants with enhanced properties. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these methodologies across critical performance and implementation parameters.

| Engineering Method | Key Differentiating Factor | Screening Throughput Required | Data Dependency | Typical Activity Improvement (Fold) | Primary Industrial Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational Design | Structure-based computational prediction | Low to Moderate (102-103 variants) | High (requires detailed structural knowledge) | 1.5-5x | Introducing specific properties (e.g., thermostability) |

| Directed Evolution | Iterative random mutagenesis and screening | Very High (104-106 variants) | Low (initial library generation) | 10-100x+ | Broad substrate scope, activity enhancement |

| ML-Guided Engineering | Predictive modeling from sequence-function data | Moderate (103-104 variants for training) | High (requires structured training dataset) | 1.6-42x (demonstrated for amide synthetases) [2] | Parallel optimization for multiple target reactions |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Specifications

Directed Evolution Protocol:

- Library Generation: Create genetic diversity through error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis targeting specific residues [1].

- Expression and Screening: Express variant libraries in host systems (e.g., E. coli, yeast) and implement high-throughput activity screening (microtiter plates, FACS).

- Selection and Iteration: Identify improved variants, use as templates for subsequent evolution rounds. Critical to this method is the screening assay design, which must reliably detect desired improvements in activity, specificity, or stability across thousands of variants.

ML-Guided Engineering Protocol (as demonstrated for amide synthetase engineering [2]):

- Initial Dataset Generation:

- Model Training: Use sequence-function data to train supervised ridge regression ML models, optionally augmented with evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictors [2].

- Prediction and Validation: Model predicts higher-order mutants with improved activity; top candidates are experimentally validated.

- DBTL Cycle: Iterate through design-build-test-learn cycles, incorporating new data to refine model predictions [2].

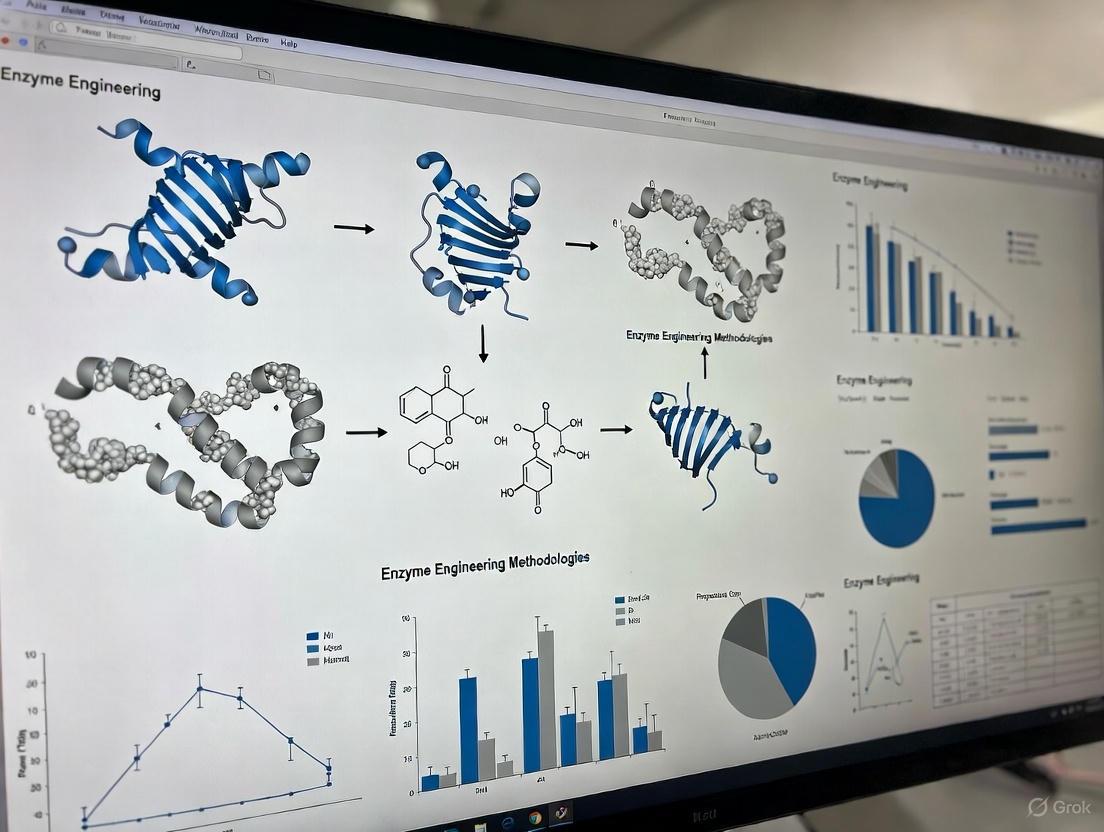

Visualization of ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering Workflow

ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering Workflow

Case Study: ML-Guided Engineering of Amide Synthetases

Experimental Implementation and Outcomes

A recent landmark study demonstrates the implementation of ML-guided engineering for amide bond-forming enzymes, with significant implications for pharmaceutical synthesis [2]. Researchers focused on McbA, an ATP-dependent amide bond synthetase from Marinactinospora thermotolerans, which displays natural substrate promiscuity but requires enhancement for efficient synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds [2]. The experimental workflow generated 1,217 enzyme variants that were evaluated in 10,953 unique reactions to map sequence-function relationships for nine target pharmaceutical compounds, including moclobemide, metoclopramide, and cinchocaine [2].

The resulting dataset trained augmented ridge regression ML models that successfully predicted enzyme variants with significantly improved activity. Quantitative results demonstrated 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity relative to the parent enzyme across the nine target compounds [2]. This approach notably enabled parallel optimization of a single generalist enzyme (McbA) into multiple specialist variants, each optimized for distinct chemical transformations – a capability challenging to achieve with conventional directed evolution.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the quantitative improvements achieved through ML-guided engineering of McbA amide synthetase compared to what might be expected through conventional methods.

| Engineering Outcome | ML-Guided Approach | Traditional Directed Evolution | Rational Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variants Screened | 1,217 initial variants [2] | Typically 104-106 variants | 102-103 variants |

| Activity Improvement Range | 1.6-42x fold increase [2] | 10-100x+ possible, but resource intensive | Typically 1.5-5x |

| Parallel Optimization Capacity | High (9 compounds simultaneously) [2] | Low (typically sequential) | Moderate (requires individual designs) |

| Sequence-Function Insights | Quantitative landscape mapping | Limited to hit identification | Structure-based hypotheses |

| Resource Requirements | Moderate throughput screening with computational prediction | Very high throughput screening | Low throughput with computational design |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of advanced enzyme engineering methodologies requires specialized reagents and platforms. The following table details essential research solutions employed in cutting-edge enzyme engineering workflows, particularly the ML-guided cell-free approach.

| Research Tool | Function in Workflow | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Gene Expression (CFE) Systems | Rapid protein synthesis without cloning or transformation | Expressed 1,217 McbA variants in a day [2] |

| Linear Expression Templates (LETs) | PCR-amplified DNA for direct protein expression | Enabled rapid iteration in design-build-test-learn cycles [2] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Libraries | Systematic exploration of single-residue mutations | Targeted 64 active site residues in McbA (1,216 variants) [2] |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Predictive modeling from sequence-function data | Ridge regression models trained on 10,953 reaction outcomes [2] |

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | Functional characterization of variant libraries | Measured amide bond formation for pharmaceutical synthesis [2] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that ML-guided approaches represent a transformative advancement in enzyme engineering, particularly for complex optimization challenges requiring parallel development of multiple enzyme specialties. While directed evolution remains powerful for broad activity enhancements and rational design offers precision for specific properties, the integration of machine learning with high-throughput experimental platforms creates unprecedented capability to navigate protein sequence space efficiently [2] [3].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the practical implications are substantial. The ML-guided framework reduces screening burdens while generating quantitative sequence-function landscapes that accelerate both applied enzyme development and fundamental understanding of catalytic mechanisms [2]. As artificial intelligence methodologies continue advancing rapidly, future developments will likely further enhance prediction accuracy and expand the scope of engineerable enzyme functions [3]. These technologies promise to bridge more effectively the critical gap between natural catalysis and industrial requirements, enabling more sustainable and efficient biocatalytic processes across the pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

The concept of a protein fitness landscape provides a powerful framework for understanding the complex relationship between a protein's amino acid sequence and its function. Originally introduced to describe the relationship between fitness and an entire genome, this term is now widely used to describe the mapping between a protein-coding gene sequence and the resulting protein function [4]. In this landscape, protein sequences are mapped to corresponding fitness values representing measurable properties like catalytic activity, thermostability, or expression levels [5]. Protein engineering aims to navigate this vast sequence space to discover variants with enhanced or novel functions, with applications spanning biotechnology, medicine, and industrial biocatalysis [6] [5].

Despite conceptual elegance, experimental characterization of fitness landscapes faces fundamental challenges. The sequence space for even a small protein is astronomically large—a 250-amino-acid protein has 20²⁵⁰ possible sequences [4]—while experimental measurements remain sparse relative to this vastness [7]. This data limitation has driven the development of innovative methodologies that combine high-throughput experimentation with machine learning to efficiently explore and exploit fitness landscapes. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies, their experimental protocols, and their performance in practical protein engineering applications.

Methodological Comparison

Recent advances in protein engineering have produced three dominant paradigms for navigating fitness landscapes: autonomous laboratory platforms, machine-learning guided cell-free systems, and computational prediction methods. The table below compares their key characteristics and applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Protein Fitness Landscape Navigation Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Features | Throughput | Experimental Validation | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Driving Laboratories (SAMPLE) | Fully autonomous design-test-learn cycles; Bayesian optimization; robotic experimentation | 3 protein designs per round; 9-hour cycle time | Glycoside hydrolase thermal tolerance improved by ≥12°C; <2% of landscape searched [6] | Enzyme thermal stability optimization; autonomous protein engineering |

| ML-Guided Cell-Free Engineering | Ridge regression models; cell-free protein expression; substrate promiscuity mapping | 10,953 reactions for 1,217 variants [2] | 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity for pharmaceutical synthesis [2] | Divergent enzyme specialization; multi-substrate optimization |

| Computational Fitness Prediction (EvoIF) | Protein language models; evolutionary information; inverse folding likelihoods | 217 mutational assays; >2.5M mutants [7] | State-of-the-art on ProteinGym benchmark with 0.15% training data [7] | Zero-shot fitness prediction; mutation impact assessment |

Experimental Protocols

Autonomous Laboratory Systems

The Self-driving Autonomous Machines for Protein Landscape Exploration (SAMPLE) platform implements fully autonomous protein engineering through integrated machine learning and robotic experimentation [6]. The experimental workflow comprises:

Gene Assembly: Pre-synthesized DNA fragments are assembled using Golden Gate cloning to produce full genes with necessary untranslated regions for T7-based protein expression [6].

Expression Template Amplification: Assembled expression cassettes are amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR), with products verified using EvaGreen fluorescent dye for double-stranded DNA detection [6].

Cell-Free Protein Expression: Amplified expression cassettes are added directly to T7-based cell-free protein expression reagents to produce target proteins [6].

Biochemical Characterization: Expressed proteins are characterized using colorimetric/fluorescent assays to evaluate biochemical activity and properties, with specialized assays for thermostability (T₅₀ measurement) [6].

The platform incorporates multiple quality control checkpoints, including verification of successful gene assembly and PCR, analysis of enzyme reaction progress curves, and detection of background hydrolase activity from cell-free extracts [6].

ML-Guided Cell-Free Engineering

This methodology employs cell-free systems for rapid protein expression and functional characterization, with the following optimized protocol [2]:

Cell-Free DNA Assembly: DNA primers containing nucleotide mismatches introduce desired mutations through PCR, followed by DpnI digestion of parent plasmid.

Intramolecular Gibson Assembly: Forms mutated plasmid without requiring bacterial transformation.

Linear Expression Template Amplification: Second PCR amplifies linear DNA expression templates (LETs) for direct use in cell-free systems.

Cell-Free Protein Synthesis: Mutated proteins are expressed using cell-free gene expression systems, bypassing cellular constraints.

High-Throughput Functional Assay: Enzyme activities are measured against multiple substrates in parallel, enabling substrate promiscuity profiling.

This workflow enables construction and testing of hundreds to thousands of sequence-defined protein mutants within a single day, with mutations accumulated through rapid iterations [2].

Deep Mutational Scanning

For fitness landscape characterization, deep mutational scanning provides high-throughput functional assessment of protein variants [8] [4]:

Library Construction: Generate variant libraries through error-prone PCR or saturation mutagenesis, with each variant identified by a unique DNA barcode.

Functional Sorting: Sort variants based on functional output (e.g., fluorescence intensity via FACS) while controlling for expression levels using a reporter protein like mKate2 [4].

Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence barcodes from sorted populations and use frequency changes to estimate functional fitness for thousands of variants.

Data Processing: Employ specialized tools like InDelScanner for detecting, aggregating, and filtering insertions, deletions, and substitutions in sequencing data [8].

Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Fitness Landscape Navigation

Performance Metrics

Quantitative assessment of methodology performance reveals distinct strengths across optimization metrics.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics Across Methodologies

| Methodology | Optimization Target | Performance Gain | Screening Efficiency | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAMPLE Platform | Glycoside hydrolase thermal tolerance | ≥12°C improvement in T₅₀ [6] | <2% of landscape searched; 60 designs tested [6] | Specialized robotics required; initial equipment cost |

| ML-Cell-Free | Amide synthetase activity | 1.6- to 42-fold improvement across 9 pharmaceuticals [2] | 1217 variants tested in 10,953 reactions [2] | Limited to reactions compatible with cell-free systems |

| EvoIF Prediction | General fitness prediction | State-of-the-art on ProteinGym benchmark [7] | Zero-shot prediction without experimental data [7] | Accuracy depends on evolutionary information availability |

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental methodologies rely on specialized reagents and computational tools, summarized in the table below.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Fitness Landscape Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | Biochemical reagent | Rapid protein synthesis without cellular constraints | High-throughput enzyme characterization [2] |

| Golden Gate Assembly | Molecular biology tool | Modular DNA assembly from standardized fragments | Combinatorial library construction [6] |

| DNA Barcodes | Sequencing tool | Unique variant identification in pooled assays | Deep mutational scanning [8] [4] |

| InDelScanner | Software | Detection and analysis of insertions and deletions | Fitness landscape analysis with indels [8] |

| Protein Language Models (pLMs) | Computational tool | Zero-shot fitness prediction from evolutionary patterns | EvoIF framework [7] |

| Fluorescent Reporters (mKate2) | Optical tool | Expression normalization in sorting assays | FACS-based deep mutational scanning [4] |

The navigation of protein fitness landscapes has evolved from purely experimental approaches to integrated methodologies that combine machine learning, high-throughput experimentation, and computational modeling. Autonomous systems like SAMPLE demonstrate remarkable efficiency in focused optimization tasks, achieving significant stability improvements while searching only a tiny fraction of sequence space [6]. ML-guided cell-free engineering excels at parallel optimization across multiple functional objectives, enabling divergent specialization of generalist enzymes [2]. Meanwhile, computational methods like EvoIF provide increasingly accurate zero-shot predictions by leveraging evolutionary information from natural sequences [7].

The choice between these methodologies depends critically on the specific protein engineering objectives, available resources, and desired throughput. For industrial applications requiring specialized enzymes with multiple optimized properties, ML-guided cell-free systems offer compelling advantages. For stability engineering with limited experimental capacity, autonomous platforms provide robust optimization. Computational methods continue to advance, with benchmarks like the Protein Engineering Tournament establishing standardized performance evaluation [9] [10]. As these methodologies mature and integrate, they promise to accelerate the design of novel proteins with transformative applications across biotechnology, medicine, and sustainable manufacturing.

Historical Context

Directed evolution (DE), a method that mimics natural selection in a laboratory setting to steer proteins toward user-defined goals, has revolutionized enzyme engineering and biomolecule design [11]. Its development, recognized by the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, represents a convergence of insights from various experimental traditions over decades.

The conceptual origins of directed evolution can be traced to pioneering in vitro evolution experiments in the 1960s. In 1967, Sol Spiegelman and colleagues conducted a landmark study demonstrating the evolution of self-replicating RNA molecules by Qβ bacteriophage RNA polymerase, creating what became known as "Spiegelman's Monster" [11] [12]. This work provided an early model system for studying evolutionary principles under controlled conditions. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, researchers began applying mutagenesis to whole cells; one early example from 1964 used chemical mutagenesis to induce a xylitol utilization phenotype in Aerobacter aerogenes [13].

A significant shift toward application-driven protein engineering occurred in the 1980s with the development of phage display by George Smith. This technique allowed the selection of binding peptides and proteins displayed on the surface of filamentous phages, providing a direct link between genotype and phenotype [13] [12]. However, the broader adoption of directed evolution for enzyme engineering began in the 1990s, marked by the development of general methods for creating and screening diverse gene libraries. A landmark 1993 study by Chen and Arnold demonstrated the power of iterative random mutagenesis using error-prone PCR to evolve subtilisin E for 256-fold higher activity in dimethylformamide [13]. The subsequent development of DNA shuffling by Willem Stemmer in 1994 introduced in vitro recombination as a powerful diversification strategy, enabling the evolution of a β-lactamase with a 32,000-fold increase in antibiotic resistance [13].

Table 1: Major Historical Milestones in Directed Evolution

| Time Period | Key Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1960s-1970s | Early in vitro evolution (Spiegelman's Monster) | Demonstrated evolutionary principles in a test tube [12] |

| 1980s | Development of phage display | Enabled selection of proteins with desired binding properties [11] |

| 1990s | Error-prone PCR & DNA shuffling | Established general methods for enzyme evolution and improvement [13] |

| 2000s-2010s | High-throughput screening methods | Dramatically increased library screening capacity [14] |

| 2010s-Present | Ultrahigh-throughput & in vivo continuous evolution | Enabled exploration of vastly larger sequence spaces [15] |

Fundamental Mechanisms

The fundamental mechanism of directed evolution intentionally mirrors the process of natural selection, condensing it into an iterative, manageable laboratory workflow. This process consists of three core steps repeated over multiple generations: diversification, selection/screening, and amplification [11].

The Directed Evolution Cycle

The directed evolution cycle is a recursive process designed to accumulate beneficial mutations in a stepwise fashion.

Step 1: Generating Diversity (Diversification)

The first step involves creating a library of genetic variants for the gene of interest. The methods for generating this diversity fall into several categories, each with distinct advantages.

Random Mutagenesis introduces mutations throughout the entire gene sequence without requiring prior structural knowledge. The most common method is error-prone PCR (epPCR), which uses biased reaction conditions (e.g., Mn²⁺ addition, unbalanced dNTP concentrations) to reduce the fidelity of DNA polymerase, resulting in random base substitutions [13] [16]. This approach is ideal for globally determined properties like thermostability but offers reduced sampling of mutagenesis space [12]. Other methods include using mutator strains of E. coli with defective DNA repair systems or chemical mutagens like nitrous acid or ethyl methane sulfonate to modify template DNA [16].

Recombination Strategies mimic natural genetic recombination by shuffling fragments from multiple parent genes. DNA shuffling involves digesting a set of homologous genes with DNase I, then reassembling the fragments into full-length chimeric genes using a primer-free PCR [13]. This method allows the combination of beneficial mutations from different parents and can access novel sequences between parental genes in sequence space [11]. Related techniques include the Staggered Extension Process (StEP), which generates recombinant genes through abbreviated primer extension cycles that promote template switching [13].

Targeted/Semi-Rational Mutagenesis focuses diversity on specific regions of the protein to create smaller, more intelligent libraries. Site-saturation mutagenesis replaces a specific amino acid position with all or most of the other 19 amino acids, allowing in-depth exploration of key positions [12] [16]. This approach is particularly effective when structural data identifies active site residues or other functionally important regions [14].

Table 2: Common Methods for Library Generation in Directed Evolution

| Method | Principle | Key Advantage | Common Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR | Random point mutations via low-fidelity PCR | Easy to perform; no prior knowledge needed | Global properties (e.g., thermostability) [12] |

| DNA Shuffling | Recombination of gene fragments from multiple parents | Combines beneficial mutations; jumps in sequence space | Family shuffling of homologous enzymes [13] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Systematic randomization of specific codons | Focused exploration of key residues | Active site engineering [16] |

| RAISE | Random insertion and deletion of short sequences | Generates indels; explores different length variations | Backbone remodeling [12] |

| Orthogonal Replication Systems | In vivo mutagenesis using engineered DNA polymerases | Continuous evolution in host organism | Long-term adaptive evolution [15] |

Step 2: Identifying Improved Variants (Selection/Screening)

The second step involves identifying the rare improved variants from the library. This requires a robust method that links the protein's function (phenotype) to its gene (genotype) [11].

Screening Methods involve individually assaying each variant (or host cell expressing it) to quantitatively measure activity. This requires a detectable signal, often from a colorimetric or fluorogenic reaction. While providing detailed quantitative data, screening throughput is often limited by instrumentation [11]. Ultrahigh-throughput screening methods have dramatically expanded capabilities:

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) can screen millions of variants per hour when activity is coupled to fluorescence [15].

- Microfluidic Droplet Sorting encapsulates single cells or enzymes in picoliter-volume water-in-oil emulsions, allowing compartmentalized assays and sorting at rates exceeding thousands of droplets per second [14].

Selection Methods directly couple desired protein function to host cell survival or replication. For example, an enzyme that degrades a toxin or synthesizes an essential metabolite allows only improved variants to propagate [11]. While extremely powerful for enriching functional clones from enormous libraries (up to 10¹⁵ variants), selection systems can be challenging to design and provide less quantitative information than screening [11].

Step 3: Gene Amplification and Iteration

The final step involves amplifying the genes encoding the best-performing variants, either using PCR or by growing host cells [17]. These sequences then serve as templates for the next round of diversification, continuing the evolutionary cycle until the desired functionality is achieved [11]. The stringency of selection can be increased with each round to drive further improvements.

Experimental Protocols and Data

Representative Experimental Workflow: Evolving Thermostable α-Amylase

A 2024 study demonstrated an ultrahigh-throughput screening-assisted in vivo directed evolution platform for enzyme engineering [15]. The workflow for evolving α-amylase activity exemplifies modern directed evolution protocols:

Library Construction: An in vivo mutagenesis system in E. coli was employed, utilizing a mutagenic plasmid expressing an error-prone DNA polymerase I (Pol I*) and a genomic MutS mutation to fix mutations. The system was thermally inducible, allowing controlled mutation rates.

Diversification: Cultures of E. coli hosting the α-amylase gene were grown under inducing conditions (temperature upshift to 37°C) to activate the mutagenesis system, generating a diverse library of α-amylase variants.

Screening: The library was subjected to microfluidic droplet screening. Single cells were encapsulated in droplets with a fluorescent substrate for α-amylase. Active variants produced a fluorescent signal, enabling sorting.

Iteration: Improved variants identified by sorting were subjected to additional rounds of diversification and screening.

Outcome: After iterative rounds, a mutant with a 48.3% improvement in α-amylase activity was identified [15].

Quantitative Outcomes of Directed Evolution Campaigns

An analysis of 81 directed evolution campaigns from the literature provides quantitative insight into the typical improvements achieved [16]. The data reveal that while dramatic improvements are possible, most successful campaigns achieve more modest gains.

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis of Directed Evolution Outcomes from 81 Studies [16]

| Kinetic Parameter | Average Fold Improvement | Median Fold Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| kcat (or Vmax) | 366-fold | 5.4-fold |

| Km | 12-fold | 3-fold |

| kcat/Km | 2548-fold | 15.6-fold |

Notable success stories beyond these averages include:

- The evolution of a P450 monooxygenase for propane oxidation, creating a pathway from alkanes to alcohols as biofuels [16].

- The engineering of phosphite dehydrogenase for cofactor regeneration, improving its half-life at 45°C by more than 23,000-fold [16].

- The evolution of an enantioselective transaminase for sitagliptin synthesis, streamlining manufacturing and reducing costs for this antihyperglycemic drug [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful directed evolution experiments rely on specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for a typical campaign.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Directed Evolution

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenic Polymerases | Introduces random mutations during PCR | Engineered error-prone polymerases (e.g., Mutazyme II) reduce mutation bias [16] |

| Expression Vectors | Hosts the gene library for expression in a host organism | Vectors with inducible promoters (e.g., pET, pBAD); phage vectors for display technologies [11] |

| Host Organisms | Expresses the variant proteins | E. coli (common), yeast (for eukaryotic proteins), specialized mutator strains [11] |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrates | Enables detection of enzyme activity in screening | Substrates that release a fluorescent or colored product upon enzymatic turnover [14] |

| Microfluidic Droplet Generators | Creates monodisperse emulsion compartments for UHTS | Commercial systems (e.g., Dolomite Bio); allows screening of >10⁷ variants [14] [15] |

| FACS Instrumentation | Sorts cells or beads based on fluorescence | Standard flow cytometers; essential for screening display libraries or biosensor-coupled systems [14] [15] |

| Commercial Library Services | Synthesizes custom DNA libraries | Vendors (e.g., Twist Bioscience, Genscript) provide high-quality targeted libraries [14] |

The field of enzyme engineering is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional laboratory-based methods to sophisticated computational approaches that are accelerating the design and optimization of biocatalysts. Where once researchers relied primarily on directed evolution and rational design based on natural enzyme templates, computational methods now enable the prediction, design, and optimization of enzyme structures and functions with unprecedented speed and precision [18] [19]. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques that can analyze complex sequence-function relationships and generate novel enzyme designs that transcend natural evolutionary boundaries [20] [21]. These advanced approaches are overcoming the limitations of conventional methods, which often struggled with small functional datasets, low-throughput screening strategies, and limited exploration of sequence space [3].

The integration of multi-step computational workflows represents the cutting edge of enzyme engineering research. By combining structure prediction algorithms with generative AI and molecular dynamics simulations, researchers can now tackle increasingly complex enzyme design challenges [22]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of computational enzyme engineering methodologies, their experimental validation, and their practical applications in addressing pressing challenges in biotechnology, medicine, and sustainable chemistry.

Methodological Comparison: Computational Approaches in Enzyme Engineering

Traditional Structure-Based Design

Traditional computational approaches to enzyme engineering have primarily focused on modifying existing enzyme scaffolds through structure-based rational design. These methods leverage computational tools to analyze protein structures and identify specific residues for mutation to enhance desirable properties such as stability, activity, or selectivity [19]. Molecular docking simulations and molecular dynamics have been particularly valuable for understanding enzyme-substrate interactions and predicting the effects of mutations on enzyme function [23]. While these approaches have yielded significant successes, they remain constrained by the fundamental limitations of natural enzyme templates and our incomplete understanding of the complex relationship between protein structure and function [19].

AI and Machine Learning-Driven Engineering

The emergence of AI and ML has introduced powerful new capabilities to enzyme engineering. These data-driven approaches can identify complex patterns in large sequence-function datasets that are not apparent through traditional analysis [18] [24]. Supervised learning algorithms such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forests, and neural networks have demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting enzyme functional classes from sequence and structural features [18]. More recently, deep learning architectures including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and graph neural networks (GCNs) have shown superior capability in capturing spatial and sequential relationships within enzyme structures [18] [24].

Generative AI for De Novo Enzyme Design

The most revolutionary development in computational enzyme engineering is the application of generative AI for de novo enzyme design [20] [21]. Unlike previous approaches that modified existing natural enzymes, generative AI models can create entirely novel enzyme sequences and structures optimized for specific functions [20]. Techniques such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and diffusion models have enabled researchers to explore vast regions of protein sequence space beyond natural evolutionary boundaries [24] [21]. For instance, ProteinGAN, a specialized variant of GAN, has demonstrated the ability to learn natural protein sequence diversity and generate functional novel sequences [21]. These approaches mark a pivotal shift from identifying and modifying natural enzymes to ground-up design of bespoke biocatalysts [21].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Computational Approaches in Enzyme Engineering

| Methodology | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Tools/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Rational Design | Modifies existing enzyme scaffolds based on structural analysis | High precision for targeted mutations; Well-established methodology | Limited by natural enzyme templates; Requires extensive structural knowledge | Molecular docking software; Molecular dynamics simulations |

| Machine Learning-Guided Engineering | Learns sequence-function relationships from large datasets | Identifies complex patterns beyond human perception; Improves with more data | Dependent on quality and quantity of training data; Black box nature | SVM; Random Forest; CNN; RNN [18] |

| Generative AI De Novo Design | Creates novel enzyme sequences from scratch | Explores beyond natural sequence space; No template limitations | High computational cost; Complex validation required | RFDiffusion; PLACER; ProteinGAN [21] [22] |

| Hybrid AI-Physics Workflows | Combines AI with physics-based simulations | Leverages strengths of both approaches; More physiologically realistic | Implementation complexity; Parameterization challenges | PLACER with RFDiffusion [22] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

ML-Guided Cell-Free Engineering Platform

A groundbreaking experimental platform developed by Karim and colleagues demonstrates the powerful integration of machine learning with high-throughput experimentation for enzyme engineering [3]. This methodology addresses critical limitations of conventional approaches by enabling rapid generation of large functional datasets that ML models require. The protocol begins with the creation of a diverse mutant library of the target enzyme, in their case the amide synthetase McbA. Rather than relying on cellular expression systems, the team employs a cell-free protein synthesis platform to express 1,217 enzyme variants in parallel [3]. This cell-free approach enables high-throughput screening under customizable reaction conditions, ultimately allowing the team to assess enzyme functionality across 10,953 unique reactions [3].

The resulting sequence-function data serves as training material for machine learning models that predict enzyme performance on novel substrates. In their published work, the researchers used the trained model to identify amide synthetase variants capable of synthesizing nine small-molecule pharmaceuticals [3]. The platform's iterative nature enables continuous refinement of the ML models as additional experimental data is accumulated. This methodology significantly accelerates the exploration of sequence-fitness landscapes across multiple regions of chemical space simultaneously, representing a substantial advancement over conventional one-reaction-at-a-time approaches [3].

AI-Driven Multi-Step Enzyme Design Workflow

A more complex experimental workflow for designing entirely novel enzymes has been demonstrated by researchers tackling the challenge of creating esterase enzymes capable of digesting plastic polymers [22]. This protocol involves a multi-step AI pipeline that begins with RFDiffusion, a generative AI tool that creates novel protein scaffolds based on structural motifs from known esterase enzymes [22]. The initial designs are then filtered by a second neural network that selects amino acid sequences forming binding pockets complementary to the target ester substrate.

The most innovative aspect of this protocol is the integration of PLACER, a specialized AI tool trained on protein-ligand complex structures that can optimize enzyme designs for multi-step catalytic mechanisms [22]. Through iterative cycles of design generation with RFDiffusion and optimization with PLACER, the researchers successfully created functional enzymes capable of catalyzing the complex four-step reaction mechanism required for ester bond hydrolysis [22]. This workflow represents a significant advancement in de novo enzyme design, as it addresses the challenge of creating enzymes that must adopt multiple transition states during their catalytic cycle.

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Multi-Step Enzyme Design Workflow. This workflow illustrates the iterative process combining multiple AI tools for de novo enzyme design, as demonstrated in the development of plastic-digesting enzymes [22].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Assessment of Engineering Approaches

Direct comparison of computational enzyme engineering approaches reveals significant differences in their efficiency, success rates, and applicability. Traditional structure-based design methods typically achieve functional enzyme variants in approximately 5-15% of designed mutants, with optimization cycles requiring several months to complete [19]. In contrast, ML-guided approaches demonstrate substantially improved efficiency. The cell-free platform described by Karim et al. enabled engineering of McbA amide synthetase for six pharmaceutical compounds simultaneously, with all newly generated enzyme variants showing improved amide bond formation capability [3].

The most impressive performance metrics come from advanced AI-driven de novo design workflows. In the development of esterase enzymes, researchers reported that initial designs using RFDiffusion alone yielded only 2 functional enzymes out of 129 designs (1.6% success rate) [22]. However, with the integration of PLACER for multi-step mechanism optimization, the success rate increased more than three-fold, ultimately reaching 18% for enzymes capable of cleaving ester bonds, with two designs ("super" and "win") demonstrating full catalytic cycling capability [22]. This progressive improvement highlights the power of combining complementary AI tools in structured workflows.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Computational Enzyme Engineering Approaches

| Engineering Approach | Success Rate | Time Cycle | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Design | 5-15% | 3-6 months | Moderate improvements in activity/selectivity | Individual enzyme assays; Kinetic characterization |

| ML-Guided Cell-Free Platform [3] | Significant improvement over conventional methods | Weeks | Enabled engineering for 6 compounds simultaneously | 10,953 reactions tested; Pharmaceutical synthesis validated |

| AI-Driven De Novo Design (Initial Phase) [22] | 1.6% (2/129 designs) | Not specified | Basic ester bond cleavage | Fluorescence-based activity screening |

| AI-Driven De Novo Design (with PLACER) [22] | 18% | Not specified | Full catalytic cycling; PET plastic digestion | Multiple reaction cycles; Plastic degradation assays |

Application-Specific Performance

The comparative performance of computational enzyme engineering approaches varies significantly across different application domains. In industrial biotechnology, ML-guided engineering has demonstrated remarkable success in optimizing enzymes for harsh process conditions. For example, engineering of cellulases and hemicellulases to withstand high temperatures and acidic environments has significantly improved the economic viability of biofuel production [19]. Similarly, in the pharmaceutical sector, engineered cytochrome P450s and amine oxidases have enabled more efficient synthesis of complex drug molecules [19].

Generative AI approaches have shown particular promise in creating enzymes for novel functions not observed in nature. The development of enzymes capable of digesting plastic polymers like PET demonstrates how AI-driven design can address environmental challenges [22]. In another innovative application, Biomatter's generative AI tools successfully redesigned α1,2-fucosyltransferase to selectively produce Lacto-N-fucopentaose (LNFP I), a valuable human milk oligosaccharide, while minimizing byproduct formation – an essential achievement for industrial-scale manufacturing [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Enzyme Engineering

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems [3] | High-throughput expression of enzyme variants without cellular constraints | Rapid screening of 1,217 McbA mutants across 10,953 reactions [3] |

| Directed Mutagenesis Libraries | Generation of sequence diversity for ML training | Creating sequence-function landscapes for amide synthetase engineering [3] |

| Fluorescence-Based Activity Reporters [22] | High-throughput screening of enzyme function | Detection of ester bond cleavage in de novo designed enzymes [22] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Predictions [24] | Accurate 3D structure prediction from amino acid sequences | Providing structural data for enzyme binding pocket engineering [24] [23] |

| RFDiffusion [22] | Generative AI for novel protein scaffold design | Creating initial enzyme designs for esterase function [22] |

| PLACER [22] | AI optimization for multi-step catalytic mechanisms | Engineering functional esterases with full catalytic cycling capability [22] |

| ProteinGAN [21] | Generative adversarial network for protein sequence generation | De novo design of α1,2-fucosyltransferase with improved specificity [21] |

The field of computational enzyme engineering is rapidly evolving, with several emerging frontiers promising to further accelerate innovation. The integration of larger and more diverse training datasets will continue to enhance the predictive capabilities of ML and AI models [18] [24]. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated AI architectures that better capture the dynamic nature of enzyme catalysis and allosteric regulation represents an important research direction [20] [23]. As noted by Karim, "New and powerful artificial intelligence approaches are coming out rapidly. We would like to take advantage of these new methods to make our workflows even more capable of creating new-to-nature proteins" [3].

Future advancements will likely focus on increasing the robustness and industrial applicability of computationally designed enzymes. This includes engineering not just for catalytic activity, but also for stability, expression yield, and resistance to process inhibitors [3] [19]. The successful application of these advanced computational approaches will ultimately enable the development of bespoke enzymes for applications in green chemistry, pharmaceutical manufacturing, environmental remediation, and sustainable energy production – expanding the toolbox available to address some of humanity's most pressing challenges [3] [21] [22].

In the field of enzyme engineering, the systematic evaluation of engineered biocatalysts relies on four fundamental performance metrics: activity, stability, specificity, and expressibility. These parameters form the cornerstone of assessing the success of enzyme engineering methodologies, from traditional directed evolution to cutting-edge machine learning (ML)-guided approaches. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and quantifying these metrics is crucial for developing enzymes that meet the demanding requirements of industrial applications, pharmaceutical synthesis, and sustainable technologies.

The evolution of enzyme engineering has been significantly accelerated by the integration of computational and data-driven approaches. Where conventional methods faced limitations in screening throughput and navigating vast sequence spaces, modern frameworks combine high-throughput experimental systems with ML models to efficiently explore fitness landscapes [3] [2]. This review provides a comparative analysis of current methodologies for evaluating enzyme performance, presenting standardized experimental protocols and quantitative benchmarking data to inform research and development decisions across academic and industrial settings.

Quantitative Comparison of Enzyme Performance Metrics

Activity: The Catalytic Measure

Enzyme activity, typically quantified as catalytic efficiency or turnover number, represents the fundamental capacity of an enzyme to convert substrate to product. The Michaelis constant (Kₘ) serves as a crucial parameter measuring enzyme-substrate affinity, with lower values generally indicating higher affinity [25]. Recent machine learning approaches have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in predicting Kₘ values for both wildtype and mutant enzymes, enabling virtual screening of enzyme variants before experimental validation.

Table 1: Benchmarking Enzyme Activity Enhancement Through Engineering Approaches

| Engineering Approach | Enzyme Class | Activity Enhancement | Experimental Measurement Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Guided Cell-Free Platform [3] [2] | Amide synthetase (McbA) | 1.6- to 42-fold improvement relative to parent enzyme | Cell-free expression with functional assays | High-throughput screening of 1,217 mutants across 10,953 reactions |

| GraphKM Model [25] | Various wildtype and mutant enzymes | Kₘ prediction accuracy: MSE = 0.653, R² = 0.527 | Literature-derived HXKm dataset validation | Integrates graph neural networks with protein language models |

| Data-Driven Engineering [26] | Various enzyme classes | Identified function-enhancing mutations (<1% natural occurrence) | Statistical modeling of sequence-function relationships | Machine learning screens efficiency-enhancing mutants |

Stability: Operational Longevity

Stability encompasses an enzyme's capacity to maintain structural integrity and catalytic function under operational conditions, including thermal, pH, and solvent challenges. This metric is broadly categorized into shelf stability (retention of activity during storage) and operational stability (retention of activity during use) [27]. The half-life—time taken for an enzyme to lose half its initial activity—serves as a key quantitative measure for stability assessment.

Table 2: Enzyme Stability Profiles and Enhancement Strategies

| Stability Type | Measurement Parameters | Enhancement Strategies | Industrial Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shelf Stability [27] | Time-dependent activity loss under storage conditions | Immobilization, chemical modification, supercritical fluid treatment | Determines storage requirements and product shelf life |

| Operational Stability [27] | Activity retention during reaction cycles, temperature profiles | Directed evolution, rational design, non-conventional media | Impacts process efficiency and cost in continuous operations |

| Thermal Stability | Half-life at elevated temperatures, melting temperature (Tₘ) | Ancestral sequence reconstruction, consensus design | Critical for high-temperature industrial processes |

Environmental factors profoundly influence enzyme stability. Pressure treatments, temperature-time profiles, and reaction media composition can induce conformational changes that either stabilize or destabilize enzyme structure [27]. In industrial applications, enzyme stability directly correlates with process economics, as more stable enzymes require less frequent replacement and maintain consistent productivity over extended operational periods.

Specificity: Catalytic Precision

Specificity defines an enzyme's selectivity toward particular substrates, reaction types, or stereochemical outcomes. This metric is crucial for applications requiring precise biotransformations, such as pharmaceutical synthesis where enantioselectivity determines product purity and regulatory compliance. Modern enzyme engineering approaches have demonstrated success in transforming generalist enzymes into specialized catalysts through divergent evolution strategies [2].

Engineering campaigns focused on specificity often begin with evaluating enzymatic substrate promiscuity—testing an extensive array of substrates including primary, secondary, alkyl, aromatic, and complex pharmacophore molecules [2]. This mapping of substrate scope identifies both preferred substrates and inaccessible products, guiding subsequent engineering efforts. For the amide synthetase McbA, wild-type enzyme showed strong chemo-, stereo-, and regioselectivity preferences, such as strongly favoring synthesis of S-sulpiride over R-sulpiride [2].

Expressibility: Production Yield

Expressibility quantifies the achievable yield of functional enzyme produced in a host system, directly impacting process scalability and economic viability. This metric encompasses both the quantity of expressed protein and the fraction that correctly folds into active conformation. Cell-free protein synthesis systems have emerged as valuable tools for rapid expression screening, bypassing the complexities of cellular transformation and culturing [2].

Advanced platforms now integrate cell-free DNA assembly with cell-free gene expression, enabling construction and testing of thousands of sequence-defined protein variants within days [2]. This approach eliminates biases from degenerate primers in traditional site-saturation libraries and allows accumulation of mutations through rapid iterative cycles. The methodology has been validated using well-characterized proteins like monomeric ultra-stable green fluorescent protein before application to target enzymes such as McbA [2].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

High-Throughput Activity Screening

The ML-guided cell-free platform demonstrates a comprehensive workflow for activity assessment [3] [2]:

- DNA Library Construction: Design primers containing nucleotide mismatches to introduce desired mutations via PCR

- Template Preparation: Digest parent plasmid with DpnI, perform intramolecular Gibson assembly to form mutated plasmids

- Cell-Free Expression: Amplify linear DNA expression templates (LETs) via PCR and express mutated proteins through cell-free systems

- Functional Assay: Conduct reactions under industrially relevant conditions (low enzyme loading, high substrate concentration)

- Data Collection: Quantify conversion rates using analytical methods (e.g., mass spectrometry)

- Model Training: Use sequence-function data to train machine learning models (e.g., augmented ridge regression) for predictive design

Stability Assessment Protocol

Standardized methodologies for stability evaluation include [27]:

- Thermal Stability: Incubate enzymes at various temperatures, periodically sampling for residual activity determination

- Storage Stability: Monitor activity retention of enzyme preparations (dehydrated, solution, immobilized) over extended storage periods

- Operational Stability: Measure activity maintenance during continuous use or multiple batch cycles

- Kinetic Analysis: Calculate half-life from activity decay curves to obtain quantitative stability parameters

Specificity Profiling

Comprehensive specificity assessment involves [2]:

- Substrate Scope Screening: Test enzyme against diverse substrate panels including structural analogs, stereoisomers, and functionalized molecules

- Kinetic Parameter Determination: Measure Kₘ and k꜀ₐₜ values for each substrate to calculate catalytic efficiency (k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ)

- Selectivity Analysis: Quantify enantiomeric ratio (E-value) for chiral synthesis applications

- Product Characterization: Identify and quantify reaction products using chromatographic and spectroscopic methods

Expressibility Quantification

Standardized expressibility evaluation includes [2]:

- Host System Comparison: Express target enzyme in multiple production systems (bacterial, yeast, mammalian, cell-free)

- Soluble Fraction Analysis: Separate soluble and insoluble fractions, quantifying active enzyme in each

- Functional Yield Determination: Measure total active enzyme per unit culture volume or reaction time

- Scale-Up Correlation: Assess consistency of expression levels between small-scale screening and production-scale systems

Diagram: Enzyme Engineering Workflow and Metric Evaluation

Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Performance Characterization

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Enzyme Evaluation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Expression Systems [2] | Rapid protein synthesis without cellular constraints | High-throughput screening of enzyme variants |

| ESM-2 Model [25] | Protein sequence representation via transformer-based language model | Converting protein sequences to 1,280-dimensional feature vectors |

| Graph Neural Networks [25] | Molecular graph representation of substrates | Generating 128-dimensional substrate vectors for activity prediction |

| RDKit [25] | Chemical informatics and SMILES processing | Converting substrate SMILES codes to molecular graphs |

| PaddlePaddle/PGL Framework [25] | Deep learning and graph learning implementation | GNN training and enzyme kinetics prediction |

| Gradient Boosting Models (XGBoost) [25] | Machine learning for regression tasks | Predicting kinetic parameters from sequence and structural features |

Comparative Analysis of Engineering Methodologies

Traditional vs. Data-Driven Approaches

The landscape of enzyme engineering has evolved significantly from traditional methods to increasingly sophisticated data-driven approaches:

- Directed Evolution: Classical approach involving iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening; effective but limited by screening throughput and potential oversight of epistatic interactions [2]

- Rational Design: Structure-based engineering requiring detailed mechanistic knowledge; effective for targeted improvements but limited by structural information availability

- ML-Guided Engineering: Integrates high-throughput experimental data with machine learning models; enables navigation of sequence-function landscapes and prediction of higher-order mutants with enhanced activities [2] [26]

Key Advances in Methodology

Recent innovations have addressed fundamental limitations in enzyme engineering:

- Overcoming Small Functional Datasets: ML-guided platforms rapidly generate large sequence-function datasets, capturing interactions among different amino acid residues within proteins [3]

- High-Throughput Screening Strategies: Cell-free approaches enable testing of thousands of enzyme variants across multiple reactions, providing comprehensive fitness landscapes [2]

- Divergent Evolution Capability: Engineering generalist enzymes into multiple specialists for different chemical transformations, dramatically expanding application potential [2]

Diagram: Data-Driven Prediction of Enzyme Performance Metrics

The comprehensive evaluation of activity, stability, specificity, and expressibility provides the critical framework for advancing enzyme engineering methodologies. As the field progresses toward increasingly sophisticated data-driven approaches, the integration of high-throughput experimental systems with predictive computational models enables more efficient navigation of complex sequence-function landscapes. This synergistic methodology accelerates the development of specialized biocatalysts for pharmaceutical applications, industrial processes, and sustainable technologies.

Future directions will likely focus on enhancing model generalizability across diverse enzyme families, addressing multi-objective optimization challenges, and improving integration of structural and dynamic information. The continued refinement of standardized assessment protocols and benchmarking datasets will further establish rigorous comparative evaluation across enzyme engineering platforms, ultimately advancing the design of novel biocatalysts with tailored properties for specific applications.

Advanced Engineering Toolkit: Machine Learning, Automation, and Experimental Platforms

In the field of enzyme engineering, the creation of mutant libraries represents a fundamental step in the pursuit of optimized biocatalysts. These strategies primarily diverge into two philosophical approaches: targeted mutagenesis, which focuses diversity on specific regions predicted to be functionally important, and whole-gene random approaches, which distribute genetic changes broadly across the entire gene sequence. The choice between these methodologies significantly impacts the size, quality, and functional diversity of the resulting library, ultimately determining the success of downstream screening and selection campaigns [28] [1].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these core strategies, framing them within the broader context of evaluating enzyme engineering methodologies. We present experimental data, detailed protocols, and analytical frameworks to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the most appropriate library creation method for their specific project goals.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Defining the Approaches

- Targeted Mutagenesis encompasses methods that introduce mutations at predefined positions or regions within a gene. This approach requires prior structural or functional knowledge, such as active site residues, substrate-binding pockets, or regions known to influence stability [28] [29]. Techniques include site-saturation mutagenesis (where a single codon is randomized to all possible amino acids) and combinatorial mutagenesis of multiple specific sites [1].

- Whole-Gene Random Mutagenesis involves the introduction of mutations randomly throughout the entire gene sequence. This approach does not require prior structural knowledge and aims to explore a broader sequence space, potentially discovering unexpected beneficial mutations in distal regions [28] [30]. Common methods include error-prone PCR (epPCR) and random transposon insertion [28] [30].

Quantitative Comparison of Strategic Profiles

Table 1: Strategic comparison between targeted and whole-gene random mutagenesis approaches.

| Feature | Targeted Mutagenesis | Whole-Gene Random Mutagenesis |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Requirement | High (requires structural/functional data) | Low (no prior knowledge needed) |

| Library Size & Diversity | Smaller, focused diversity | Larger, broad diversity |

| Control over Mutation Location | High precision | No control |

| Probability of Identifying "Hot-Spots" | High, as focused on known areas | Can discover novel, unexpected hot-spots |

| Risk of Disrupting Protein Folding | Lower, as stable regions can be avoided | Higher, due to random mutations |

| Primary Application | Optimizing specific properties (e.g., activity, selectivity) | Gene mining, discovering novel functions, directed evolution |

| Throughput & Screening Efficiency | Higher, smaller libraries are easier to screen | Lower, requires high-throughput screening |

| Representative Techniques | Site-directed, Site-saturation, MAGE | Error-prone PCR, Chemical mutagenesis, Transposon mutagenesis |

Key Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Table 2: Summary of experimental data and performance outcomes from selected studies.

| Study Focus | Mutagenesis Approach | Key Experimental Outcome | Performance Improvement / Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Binding Affinity [29] | Site-directed amino acid-specific mutagenesis | Molecular docking and MD simulations on cellulase (1FCE) | Binding free energy (ΔG) improved by 13.0% (Thr226Leu) and 23.3% (Pro174Ala). |

| Functional Genome Analysis [30] | IS6100-based random transposon mutagenesis | Creation of a library of 10,080 independent clones in Corynebacterium glutamicum. | 97% probability of disrupting any given non-essential gene; 2.9% frequency of auxotrophic mutants obtained. |

| Directed Evolution [28] | Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Established under mutagenic PCR conditions (modified MgCl₂, MnCl₂, dNTP concentrations). | Achieved an overall mutation rate of ~0.007 per base per reaction. |

| Therapeutic Enzyme Engineering [31] | Coupled with HTS and NGS | Integration of mutagenesis with microfluidic HTS and next-generation sequencing. | Enabled a 25-fold improvement in detection sensitivity for NADH-coupled assays. |

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol for Targeted Saturation Mutagenesis

This protocol is used to randomize a single residue to all 19 possible amino acids.

- Primer Design: Design forward and reverse primers that are complementary to the region flanking the target codon. The target codon is replaced with an NNK degeneracy, where N is any nucleotide (A, C, G, or T) and K is G or T. This degeneracy encodes all 20 amino acids and the TAG stop codon, but reduces the number of stop codons compared to NNN.

- PCR Amplification: Perform a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase, the designed mutagenic primers, and a plasmid template containing the wild-type gene.

- Template Digestion: Following PCR, treat the product with the restriction enzyme DpnI. DpnI specifically cleaves methylated DNA, which is present in the original plasmid template isolated from most E. coli strains. This step digests the parental template, enriching the final product for the newly synthesized mutated plasmids.

- Transformation and Library Generation: Transform the DpnI-treated PCR product into competent E. coli cells. The cells repair the nicks in the plasmid, and the resulting colonies constitute the mutant library.

- Validation: Sequence a statistically relevant number of clones (e.g., 20-50) to confirm the diversity and distribution of mutations at the targeted position.

Protocol for Whole-Gene Random Mutagenesis via Error-Prone PCR (epPCR)

This protocol introduces random point mutations throughout the entire gene.

- Reaction Setup: Set up a PCR reaction under mutagenic conditions to reduce polymerase fidelity. Key parameters include:

- Non-standard dNTP concentrations: Imbalance the concentrations of dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and dCTP.

- Addition of MnCl₂: Manganese ions promote misincorporation of nucleotides by the polymerase.

- Elevated MgCl₂ concentration: Increases the error rate further.

- Use of Taq DNA polymerase: This polymerase lacks proofreading activity, allowing mutations to be retained.

- Amplification: Run the PCR for the desired number of cycles. The mutation frequency can be adjusted by varying the number of cycles and the concentration of Mn²⁺.

- Cloning: Purify the epPCR product and clone it into an expression vector using standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., restriction digestion/ligation or Gibson assembly).

- Library Transformation: Transform the ligated plasmid library into a suitable host strain to create the mutant library for screening.

- Library Assessment: Sequence a random subset of clones to determine the average mutation rate (mutations per kilobase) and the spectrum of mutations (transitions vs. transversions).

Advanced Workflow: Integrating Machine Learning

Modern enzyme engineering increasingly couples these experimental library creation methods with computational analysis. A prominent workflow involves:

- Creating a initial mutant library using targeted or random approaches.

- High-throughput screening to gather sequence-function data.

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of active and inactive variants [31] [32].

- Training machine learning (ML) models (e.g., Random Forest, CNN) on this data to predict the fitness of unseen sequences [33].

- Using the ML model to virtually screen much larger sequence spaces and design a subsequent, more focused, and higher-quality library for experimental testing, creating an efficient "design-build-test-learn" cycle [31] [33].

Visualizing Strategic Workflows

Targeted vs. Random Mutagenesis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and solutions for library creation and analysis.

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Primers | Encodes all 20 amino acids at a targeted codon during PCR. | Central to site-saturation mutagenesis for exploring all possible substitutions at a single residue [1]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | A low-fidelity polymerase lacking 3'→5' exonuclease proofreading activity. | Essential for error-prone PCR (epPCR) to introduce random mutations across a gene [28]. |

| MnCl₂ (Manganese Chloride) | A divalent cation that increases the error rate of DNA polymerases. | Added to epPCR reactions to elevate the mutation frequency [28]. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Specifically digests methylated and hemimethylated DNA. | Used post-PCR to selectively degrade the original, template plasmid DNA, enriching for the mutated product [29]. |

| Transposon Vector (e.g., pAT6100) | An artificial DNA construct containing a mobile genetic element (transposon) and a selectable marker. | Used for random insertional mutagenesis to disrupt genes and create comprehensive mutant libraries, as in C. glutamicum [30]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Platforms for massively parallel DNA sequencing (e.g., Illumina, SOLiD). | Critical for deep mutational scanning, analyzing library diversity, and generating data for machine learning models [31] [32]. |

| Machine Learning Tools (e.g., RF, CNN) | Algorithms for predicting sequence-function relationships. | Used to analyze NGS data from mutant libraries and guide the design of subsequent, smarter libraries [33]. |

The dichotomy between targeted and whole-gene random mutagenesis is not a matter of selecting a single superior strategy, but rather of choosing the right tool for the specific stage of an engineering project. Targeted mutagenesis offers a highly efficient path for optimization when functional regions are known, maximizing resource utilization. In contrast, whole-gene random approaches remain invaluable for initial discovery, exploring uncharted sequence space, and when structural data is lacking.

The future of library creation lies in the intelligent integration of both approaches, powered by computational and data-driven methods. As exemplified by the rise of machine learning in enzyme engineering, the iterative cycle of building diverse libraries, testing them with high-throughput methods, and learning from the resulting data will continue to accelerate the development of novel biocatalysts for therapeutics and industrial applications.

Enzyme engineering is undergoing a transformative shift with the integration of machine learning (ML), moving beyond traditional directed evolution approaches. Where directed evolution performs greedy hill-climbing on the protein fitness landscape through iterative mutagenesis and screening, ML methods now enable researchers to navigate this vast sequence space more intelligently [34]. The search space of possible proteins is astronomically large, and functional proteins are scarce within this space, making accurate fitness prediction and sequence design an NP-hard problem [34]. ML-assisted enzyme engineering addresses this challenge through three fundamental approaches: classifying enzyme functions from sequence data, generating novel enzyme variants using generative models, and predicting variant fitness to guide experimental screening. This review provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies, their experimental protocols, and their performance in engineering enzymes for industrial and pharmaceutical applications.

Machine Learning Classification for Enzyme Function Prediction

Computational Tools for Enzyme Commission Number Prediction

Accurate enzymatic classification serves as the foundation for discovering engineering starting points. The Enzyme Commission (EC) number represents a hierarchical classification system that divides enzymes into classes and subclasses based on their catalytic activities [35]. ML classification models have emerged to annotate the millions of uncharacterized proteins in databases like UniProt, where less than 0.3% of sequences have functional annotations [34]. These models use sequence and structural features beyond simple homology, enabling accurate predictions even for proteins with few known homologs.

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Tools for Enzyme Classification

| Tool Name | ML Method | Input Type | Key Capability | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepEC | CNN | Sequence | Complete EC number prediction | Downloadable |

| ECPred | Ensemble (SVMs, kNN) | Sequence | Complete or partial EC number prediction | Webserver |

| mlDEEPre | Ensemble (CNN, RNN) | Sequence | Multiple EC number predictions for one sequence | Webserver |

| CLEAN | Contrastive Learning | Sequence | State-of-the-art EC classification with promiscuity detection | Not specified |

These classification tools address a critical bottleneck in enzyme engineering—identifying suitable starting points for engineering campaigns. For example, CLEAN (Contrastive Learning-Enabled Enzyme Annotation) has demonstrated remarkable accuracy in characterizing understudied halogenase enzymes with 87% accuracy, significantly outperforming the next-best method at 40% accuracy [34]. Importantly, CLEAN can also identify enzymes with multiple EC numbers, corresponding to promiscuous activities that often serve as starting points for evolving non-natural enzyme functions [34].

Experimental Workflow for Function-Based Enzyme Discovery

The typical workflow for ML-classified enzyme discovery involves:

- Database Curation: Compiling sequences from UniProt, metagenomic databases, and other biological repositories

- Feature Extraction: Generating numerical representations of protein sequences (e.g., embeddings, structural features)

- Model Training: Optimizing classifiers on known enzyme families and activities

- Experimental Validation: Testing predicted enzymes against target substrates using high-throughput assays

Generative Models for Enzyme Design and Optimization

Steering Generative Models with Experimental Data

Generative models represent a paradigm shift in enzyme engineering, enabling the design of novel sequences rather than merely optimizing existing ones. Steered Generation for Protein Optimization (SGPO) has emerged as a powerful framework that combines unlabeled sequence data with limited experimental fitness measurements [36]. SGPO methods leverage generative priors of natural protein sequences while steering generation using fitness data, addressing the limitations of zero-shot methods that rely solely on evolutionary patterns without experimental guidance [36].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Generative Modeling Approaches

| Method Category | Prior Information Used | Experimental Fitness Used | Scalability to Large N | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGPO | Yes | Yes | Yes | Lisanza et al., Widatalla et al. |

| Generative: Zero-Shot | Yes | No | Yes | Hie et al., Sumida et al. |

| Generative: Adaptive | No | Yes | Yes | Song & Li, Jain et al. |

| Supervised | Yes | Yes | No | Wittmann et al., Ding et al. |

Recent advances demonstrate that steering discrete diffusion models with classifier guidance or posterior sampling outperforms fine-tuning protein language models with reinforcement learning [36]. These methods show particular promise when working with small datasets (hundreds of labeled sequence-fitness pairs), which aligns with the real-world constraints of wet-lab experiments where fitness measurements are low-throughput and costly [36].

MODIFY: Co-optimizing Fitness and Diversity in Library Design

The MODIFY (Machine learning-Optimized library Design with Improved Fitness and diversitY) algorithm addresses a critical challenge in enzyme engineering: designing combinatorial libraries that balance fitness and diversity, particularly for new-to-nature functions where fitness data is scarce [37]. MODIFY employs an ensemble ML model that leverages protein language models and sequence density models for zero-shot fitness predictions, then applies Pareto optimization to design libraries with optimal fitness-diversity tradeoffs.

The algorithm solves the optimization problem: max fitness + λ · diversity, where parameter λ balances between prioritizing high-fitness variants (exploitation) and generating diverse sequence sets (exploration) [37]. This approach traces out a Pareto frontier where neither fitness nor diversity can be improved without compromising the other.

In benchmark evaluations across 87 deep mutational scanning datasets, MODIFY demonstrated superior zero-shot fitness prediction compared to individual state-of-the-art models including ESM-1v, ESM-2, EVmutation, and EVE [37]. MODIFY achieved the best Spearman correlation in 34 out of 87 datasets, showing robust performance across protein families with low, medium, and high multiple sequence alignment depths [37].

Fitness Prediction and Landscape Navigation

Supervised Learning for Fitness Prediction

Supervised ML models learn mappings between protein sequences and their associated fitness values from experimental data, acting as virtual screens to prioritize variants for experimental testing [34]. These models range from simpler ridge regression to sophisticated deep learning architectures. For example, augmented ridge regression ML models have been successfully applied to engineer amide synthetases, evaluating substrate preference for 1,217 enzyme variants across 10,953 unique reactions [2]. The resulting models predicted variants with 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity relative to the parent enzyme across nine pharmaceutical compounds [2].

Experimental Framework for ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering

A comprehensive ML-guided enzyme engineering platform integrates several components:

- Cell-free DNA assembly for rapid construction of sequence-defined protein libraries

- Cell-free gene expression for protein synthesis without laborious transformation and cloning

- High-throughput functional assays to generate sequence-function data