Enzyme Immobilization Techniques: A Strategic Guide for Industrial Biocatalysis and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzyme immobilization techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Enzyme Immobilization Techniques: A Strategic Guide for Industrial Biocatalysis and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzyme immobilization techniques, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It bridges foundational principles with advanced methodological applications, offering a clear pathway from selecting support materials to implementing techniques like covalent binding, entrapment, and carrier-free systems in industrial and pharmaceutical contexts. The content delivers practical troubleshooting strategies and comparative validation frameworks to optimize biocatalyst performance, enhance process sustainability, and reduce operational costs, directly addressing the core needs of high-value industrial biocatalysis.

Enzyme Immobilization Fundamentals: Principles, Benefits, and Industrial Drivers

Enzyme immobilization refers to the process of confining enzyme molecules to a distinct solid phase or support, separate from the reaction mixture, while retaining their catalytic activity [1]. This technology has evolved into a powerful tool for biocatalyst engineering, enabling researchers to overcome inherent limitations of free enzymes, such as poor stability under industrial conditions, limited reusability, and difficulties in separation from reaction products [1] [2]. The fundamental concept was first observed by Nelson and Griffin in 1916, who discovered that invertase could hydrolyze sucrose even after being adsorbed onto charcoal [3]. Since the 1960s, enzyme immobilization has developed into a sophisticated field integrating biotechnology, materials science, and process engineering [2].

Immobilized enzymes possess significantly enhanced resistance to environmental changes and can be easily recovered and recycled compared to their free counterparts [3]. The primary benefits include protection from harsh process conditions, continuous processing capability, and minimized enzyme contamination in final products [3] [4]. These advantages position immobilized enzymes as critical components in sustainable industrial applications across pharmaceutical manufacturing, food processing, biomedical diagnostics, and environmental biotechnology [1] [4].

Core Immobilization Techniques and Mechanisms

Classical Immobilization Methods

Immobilization techniques are broadly categorized into carrier-bound and carrier-free methods, each with distinct mechanisms and applications [1].

Table 1: Classical Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism | Binding Force | Reversibility | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Enzyme attached to support surface | Hydrophobic, ionic, van der Waals forces [2] | Reversible [2] | Simple, inexpensive, high activity retention [2] | Enzyme leakage, sensitive to pH/ionic strength [2] |

| Covalent Binding | Formation of covalent bonds with support | Covalent bonds [3] [2] | Irreversible [3] | No enzyme leakage, high stability, reusable [2] | Possible activity loss, expensive supports, complex process [2] |

| Entrapment | Enzyme confined within porous matrix | Physical confinement [1] | Irreversible | Protection from denaturation, high loading capacity [1] | Mass transfer limitations, enzyme leakage possible [1] |

| Encapsulation | Enzyme enclosed in semi-permeable membranes | Physical confinement [1] | Irreversible | Suitable for sensitive enzymes/cells [1] | Diffusion barriers, limited substrate size [1] |

| Cross-linking | Enzyme molecules linked without support | Covalent bonds between enzymes [2] | Irreversible | High enzyme concentration, no support needed | Reduced activity, mass transfer issues [2] |

Advanced and Site-Specific Methods

Modern immobilization strategies integrate protein engineering with bio-orthogonal chemistry to achieve precise control over enzyme orientation and interaction with carriers [1]. These advanced techniques include:

- Immobilization by Metal Affinity: Utilizes recombinant production of enzymes with histidine tags (His-tag) attached to N- or C-terminus, enabling specific binding to metal-functionalized supports [1].

- Site-Specific Immobilization: Incorporation of unique unnatural amino acid residues or specific tags into enzyme sequences to control orientation during immobilization [1].

- Carrier-Free Immobilization: Cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) and crystals (CLECs) that eliminate the need for solid supports, resulting in high volumetric activity [1].

These sophisticated approaches optimize catalytic performance by preserving active site accessibility and maintaining enzyme conformation, thereby maximizing activity retention and operational stability [1].

Experimental Protocols for Enzyme Immobilization

Protocol 1: Adsorption Immobilization

Principle: Immobilization through weak physical interactions between enzyme and support surface [2].

Materials:

- Enzyme solution (1-10 mg/mL in appropriate buffer)

- Adsorbent support (e.g., silica, chitosan, mesoporous materials)

- Incubation buffer (pH optimized for enzyme stability)

- Centrifuge tubes and laboratory centrifuge

- Shaking incubator or orbital shaker

Procedure:

- Support Preparation: Weigh 100 mg of adsorbent material and wash with incubation buffer (3×) to equilibrate.

- Enzyme Loading: Add 5 mL of enzyme solution to the support and incubate at 25°C with gentle shaking (100-150 rpm) for 2-4 hours.

- Washing: Centrifuge at 5000 × g for 10 minutes and discard supernatant. Wash immobilized enzyme with fresh buffer (3×) to remove unbound enzyme.

- Storage: Resuspend in storage buffer and store at 4°C until use.

Validation: Measure protein content in wash fractions to calculate immobilization yield. Assess activity retention using standard enzyme assays.

Protocol 2: Covalent Immobilization

Principle: Formation of stable covalent bonds between enzyme functional groups and activated support [2].

Materials:

- Enzyme solution (1-10 mg/mL in coupling buffer)

- Functionalized support (agarose, Eupergit C, chitosan)

- Cross-linker (glutaraldehyde or carbodiimide)

- Coupling buffer (avoiding amines for glutaraldehyde method)

- Blocking solution (e.g., 1M ethanolamine for glutaraldehyde method)

- Centrifuge equipment and vacuum filtration setup

Procedure:

- Support Activation: Incubate 100 mg of functionalized support with 2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in coupling buffer for 2 hours at 25°C with shaking.

- Washing: Wash activated support extensively with coupling buffer to remove excess cross-linker.

- Enzyme Coupling: Add 5 mL enzyme solution to activated support and incubate for 12-24 hours at 4°C with continuous mixing.

- Blocking: Wash immobilized enzyme and incubate with blocking solution for 1-2 hours to quench unreacted groups.

- Final Wash: Wash with storage buffer (3×) and store at 4°C.

Validation: Determine immobilization yield by measuring protein concentration in initial and final solutions. Test enzyme activity and compare to free enzyme.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent/ Material | Function/Application | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Supports | High surface area, mechanical stability | Silica, titania, hydroxyapatite, porous glass [2] |

| Natural Polymer Supports | Biocompatibility, functional groups | Chitosan, chitin, alginate, cellulose, agarose [2] |

| Synthetic Polymer Supports | Tunable properties, chemical resistance | Polyacrylamide, Eupergit C, polysulfone membranes [1] [2] |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Form covalent bonds between enzyme and support | Glutaraldehyde, carbodiimide [2] |

| Activation Reagents | Create reactive groups on support surface | Cyanogen bromide, N-hydroxysuccinimide [2] |

| Eco-friendly Carriers | Sustainable, cost-effective options | Coconut fibers, microcrystalline cellulose, kaolin [2] |

| Nanoparticle Supports | Enhanced surface area, unique properties | Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) [2] |

Industrial Applications and Performance Metrics

Immobilized enzymes demonstrate superior performance across multiple industrial sectors, enabling sustainable manufacturing processes with reduced environmental impact [4].

Table 3: Industrial Applications and Performance of Immobilized Enzymes

| Industry Sector | Key Enzymes | Application Examples | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical | Proteases, lipases | Drug synthesis, chiral resolution, intermediate production | High stereoselectivity, reduced production steps, >60% cost reduction [1] [4] |

| Food Processing | Proteases, amylases, lactases | Dairy processing (cheese, yogurt), starch conversion, baking | 50% lower energy input, continuous processing, extended shelf-life [3] [4] |

| Bioenergy | Cellulases, ligninases | Biomass conversion, biofuel production, platform chemicals | 85% sugar yields, 35% lower energy demands, 40-60% water usage reduction [4] |

| Environmental | Laccases, peroxidases | Wastewater treatment, dye degradation, pollutant removal | Enhanced stability under harsh conditions, reusable for multiple cycles [1] |

| Detergents | Proteases, amylases | Stain removal, fabric care, color brightening | Stability in alkaline conditions, surfactant tolerance, cold water activity [3] |

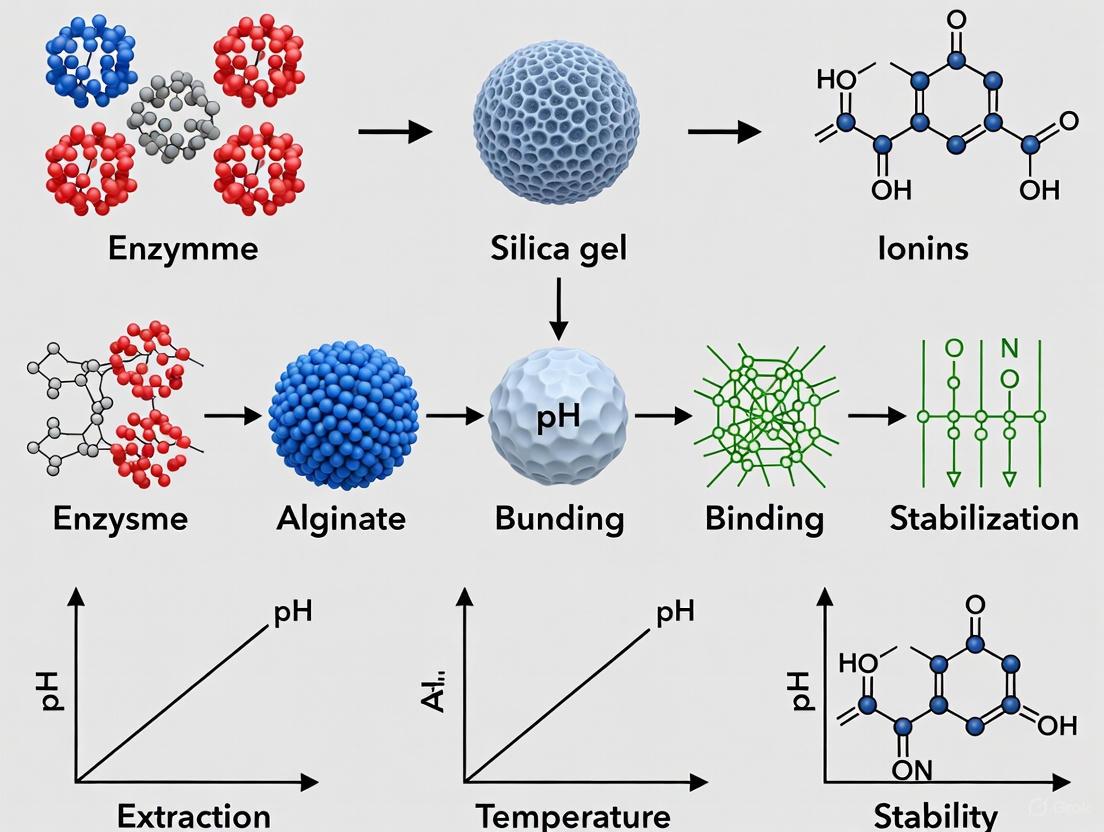

Visualization of Immobilization Workflows

Figure 1: Generalized Workflow for Enzyme Immobilization

Figure 2: Covalent Immobilization Protocol Detail

Technical Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Successful implementation of immobilized enzyme systems requires careful consideration of multiple technical parameters to balance activity, stability, and cost-effectiveness.

Support Material Selection Criteria

The ideal carrier material should possess excellent mechanical stability, substantial porous structure, large surface area, ease of modification, low cost, abundance, and environmental compatibility [3] [2]. Recent advances focus on developing high-quality, inexpensive carriers to address cost limitations of traditional materials like agaroses and Eupergit C [2].

Mass Transfer Considerations

Diffusion limitations represent a significant challenge in immobilized enzyme systems, particularly for entrapment and encapsulation methods [1]. Strategies to mitigate mass transfer constraints include:

- Utilizing supports with optimized pore size distribution

- Implementing nanoscale carriers to increase surface-to-volume ratio

- Designing hierarchical pore structures to facilitate substrate access

- Employing computational modeling to predict diffusion pathways

Integration with Enzyme Engineering

The combination of protein engineering and immobilization technologies represents the cutting edge of biocatalyst development [1]. Site-directed mutagenesis and directed evolution can enhance enzyme properties before immobilization, while specific tags or unnatural amino acids enable controlled orientation during immobilization [1]. This integrated approach maximizes stability and performance across diverse industrial applications.

Enzyme immobilization technology has evolved from basic adsorption methods to sophisticated systems integrating biotechnology, nanotechnology, and materials science. The continued advancement of immobilization strategies, particularly through integration with enzyme engineering and artificial intelligence-driven design, promises to further enhance biocatalyst performance and expand industrial applications [4]. As sustainable manufacturing becomes increasingly imperative, immobilized enzymes are positioned as key enabling technologies for circular bioeconomy models, reducing environmental impacts while maintaining economic viability across pharmaceutical, food, energy, and chemical sectors [1] [4].

Enzyme immobilization has emerged as a cornerstone technology for enabling efficient and sustainable biocatalysis in industrial processes. By fixing enzymes onto solid supports or within functional matrices, this technique directly addresses critical limitations of free enzymes, including poor operational stability, inability to recycle, and challenges in product separation [3] [1]. These advancements are particularly valuable for industries requiring high-purity products, such as pharmaceuticals, food processing, and fine chemicals [5]. This document details the core advantages of enzyme immobilization—enhanced reusability, improved stability, and superior product purity—within the broader context of developing robust industrial biocatalysts. Supported by quantitative data and detailed protocols, this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with practical insights for implementing immobilization technologies.

Core Advantages and Quantitative Data

The immobilization of enzymes significantly enhances their practical utility in industrial settings. The table below summarizes key performance metrics demonstrating improvements in reusability, stability, and purity across different immobilized enzyme systems.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Immobilized Enzymes in Industrial Applications

| Enzyme | Support/Method | Reusability | Stability Enhancement | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitinase A (SmChiA) [6] | Sodium Alginate-modified Rice Husk Beads (Covalent) | >22 cycles with full activity retention | Superior pH, temperature, and storage stability vs. free enzyme | Dye decolorization in wastewater |

| Lipase [3] | Various (e.g., adsorption, covalent binding) | Easily recovered and recycled multiple times | Higher resistance to elevated temperatures and extreme pH | Biodiesel production, food processing |

| Alkaline Protease [1] | Mesoporous Silica/Zeolite (Entrapment) | Not specified | Immobilization yield of 63.5% and 79.77% | Milk coagulation in dairy production |

| Horseradish Peroxidase [1] | Alginate Beads (Entrapment) | Not specified | Protected from denaturation and environmental stressors | Dye removal from water |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Covalent Immobilization on Functionalized Beads

This protocol describes the covalent attachment of recombinant chitinase A (SmChiA) to sodium alginate-modified rice husk beads, a method that demonstrated exceptional reusability and stability [6].

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Sodium Alginate (SA): A natural polysaccharide that forms the gel matrix of the bead [6].

- Modified Rice Husk Powder (mRHP): An eco-friendly, low-cost filler material that increases surface area and active sites for binding after modification with citric acid [6].

- Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂): A cross-linking agent that gelates sodium alginate to form solid beads [6].

- 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDAC): A cross-linker that catalyzes the formation of amide bonds between carboxyl groups on the beads and amino groups on the enzyme [6].

- Enzyme Solution (SmChiA): The recombinant chitinase A to be immobilized, expressed and purified from E. coli [6].

Procedure:

- Carrier Preparation: Mix 5g of rice husk powder (RHP) with a solution of citric acid to create modified RHP (mRHP). Dry the mixture at 60°C for 2 hours, followed by incubation at 120°C for 12 hours. After cooling, wash and vacuum-filter the mRHP to remove excess citric acid [6].

- Bead Formation: Combine sodium alginate (SA) with mRHP (at 50% weight of SA) in distilled water. Drop this mixture into a 0.1 M CaCl₂ solution using a syringe to form spherical beads. Allow the beads to cure in the CaCl₂ solution for 1 hour to ensure complete gelation, then wash with distilled water [6].

- Enzyme Immobilization: Activate the carboxyl groups on the SA-mRHP beads by incubating with EDAC solution. After activation, add the purified SmChiA enzyme solution (1.75 U/mL) to the beads and incubate for 5 hours under gentle agitation to facilitate covalent bonding [6].

- Washing and Storage: Recover the immobilized enzyme beads by filtration and wash thoroughly with buffer to remove any unbound enzyme. The prepared biocatalyst can be stored in a suitable buffer at 4°C until use [6].

Protocol 2: One-Pot Co-Precipitation in Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

This protocol outlines a one-pot method to encapsulate enzymes within Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework-8 (ZIF-8), a metal-organic framework, under mild, aqueous conditions [7].

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Zinc Acetate (Zn(OAc)₂): Provides the metal ion (Zn²⁺) nodes for MOF construction [7].

- 2-Methylimidazole (2-MIM): The organic linker that coordinates with zinc ions to form the ZIF-8 crystal structure [7].

- Target Enzyme: The enzyme to be immobilized, which must be stable under the synthesis conditions [7].

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP - optional): An additive used to form a protective layer around the enzyme, helping to preserve its activity during encapsulation [7].

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare separate aqueous solutions of zinc acetate (e.g., 25 mM) and 2-methylimidazole (e.g., 0.5-1.0 M). The 2-MIM solution should be clear [7].

- Enzyme Mixture: Mix the target enzyme solution with the zinc acetate solution. For sensitive enzymes, include a macromolecular protectorate like PVP at this stage [7].

- One-Pot Synthesis: Rapidly combine the enzyme-zinc mixture with the 2-methylimidazole solution under vigorous stirring. The formation of the ZIF-8 matrix around the enzyme molecules will begin immediately, observable by the solution turning cloudy [7].

- Incubation and Harvesting: Allow the reaction to proceed for a predetermined time (e.g., 1 hour) at room temperature. Recover the solid Enzyme@ZIF-8 biocomposite by centrifugation, then wash several times with a mild buffer (e.g., MOPS or HEPES) to remove unreacted precursors and any superficially adsorbed enzyme [7].

- Characterization and Storage: The final biocomposite can be characterized (e.g., by SEM, FTIR) and stored in a buffer at 4°C [7].

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Immobilization Technique Selection Logic

This diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting an appropriate enzyme immobilization technique based on the application's primary requirements, such as cost, stability, and need for enzyme retention.

Immobilization Impact on Industrial Biocatalysis

This workflow illustrates how the core advantages of enzyme immobilization collectively contribute to more efficient and sustainable industrial biocatalytic processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table catalogs key reagents and materials used in enzyme immobilization, along with their primary functions, as demonstrated in the featured protocols.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Immobilization Research

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Immobilization | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate | Biocompatible polymer for gel bead formation; provides carboxyl groups for covalent attachment [6]. | Entrapment and covalent immobilization [6]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Homobifunctional cross-linker for creating covalent bonds between enzyme amino groups and support [8] [7]. | Covalent immobilization on animated supports [8]. |

| Carbodiimide (e.g., EDAC) | Promotes amide bond formation between carboxyl and amino groups without being incorporated [6]. | Covalent binding to alginate-based beads [6]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (e.g., ZIF-8) | Micro-/mesoporous crystalline support for enzyme encapsulation via one-pot synthesis [7]. | One-pot enzyme encapsulation under mild conditions [7]. |

| Mesoporous Silica | Inorganic support with high surface area and tunable pores for adsorption or covalent binding [8] [1]. | Adsorptive immobilization of proteases [1]. |

| Calcium Chloride | Divalent cation for ionic cross-linking and gelation of alginate solutions [6]. | Formation of solid alginate beads [6]. |

| Chitosan | Cationic natural polymer used as a support; offers amino groups for functionalization [8]. | Ionic or covalent enzyme immobilization [8]. |

Enzyme immobilization refers to the process of confining or localizing enzyme molecules onto a solid support or within a specific space, with retention of their catalytic activities, allowing for their repeated and continuous use [9]. In the context of industrial applications, this technology provides transformative economic and environmental benefits by enhancing enzyme stability under process conditions, facilitating easy separation from reaction mixtures, and enabling catalyst reuse [9] [2]. These attributes directly translate to reduced operational costs and diminished environmental impact, aligning with the principles of green chemistry by minimizing waste and energy consumption [4].

The driving forces for immobilization are multifaceted. Principally, it confers greater operational stability to enzymes against denaturation from temperature, pH extremes, solvents, and impurities [9] [2]. Furthermore, it simplifies downstream processing and biocatalyst recycling, which significantly reduces the overall cost of enzymatic products [9] [2]. By providing a heterogeneous catalyst system, immobilization allows for continuous fixed-bed operations in bioreactors, a key factor for scalable industrial processes [9].

Economic and Environmental Drivers

The Cost-Benefit Analysis of Immobilization

The economic rationale for enzyme immobilization is compelling. The initial costs associated with the immobilization procedure and support materials are offset by the dramatic extension of the enzyme's functional lifespan and its reusability. Immobilization can reduce biocatalyst costs by over 60% through enhanced durability, making enzymatic processes economically viable on an industrial scale [4]. The table below summarizes the key economic drivers.

Table 1: Economic Benefits of Enzyme Immobilization

| Economic Factor | Impact of Immobilization | Quantitative Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Reusability | Enzyme can be recovered and used for multiple batches or in continuous processes. | Drastic reduction in enzyme consumption per unit of product. |

| Process Efficiency | Facilitates continuous fixed-bed operation; easy arrest of reaction. | Increased productivity; reduced processing time and labor [9]. |

| Downstream Processing | Simplifies separation of enzyme from products and reaction mixtures. | Lower purification costs; minimized protein contamination of products [9] [2]. |

| Operational Stability | Enhanced resistance to temperature, pH, and solvents reduces inactivation. | Less frequent enzyme replacement; more consistent operation under harsh conditions [9] [2]. |

Enhancing Green Chemistry Credentials

Immobilized enzymes are pillars of sustainable industrial processes. They operate under milder conditions (e.g., lower temperatures and near-neutral pH) compared to traditional chemical catalysts, leading to lower energy consumption [4]. Their high specificity minimizes the formation of undesirable by-products, reducing waste and simplifying purification. Lifecycle assessments of processes using immobilized enzymes demonstrate 40–60% reductions in water usage and 35% lower energy demands compared to conventional methods [4]. The integration of immobilized enzymes in biorefineries for converting lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels and chemicals is a prime example of a circular economy approach, transforming renewable waste into marketable products [4].

Core Immobilization Techniques: A Comparative Analysis

Several well-established techniques exist for enzyme immobilization, each with distinct advantages, drawbacks, and suitability for specific applications. The choice of method is critical as it directly influences the activity, stability, and cost-effectiveness of the final biocatalyst [9] [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Core Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism of Attachment | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption [2] | Weak forces (van der Waals, ionic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bonds). | Simple, reversible, low-cost, high activity retention. | Enzyme leakage due to desorption. | Rapid, low-cost setups; lab-scale screening. |

| Covalent Binding [9] [2] | Stable covalent bonds (e.g., amide, ether) via enzyme functional groups (-NH₂, -COOH). | No enzyme leakage; high stability; reusable carrier. | Harsher conditions; potential activity loss; higher cost. | Industrial processes requiring high stability and continuous use. |

| Entrapment/ Encapsulation [2] | Physical confinement within a porous polymer gel or matrix. | Enzyme protected from harsh external environment. | Diffusion limitations can reduce reaction rate. | Enzymes with small substrates; sensitive enzymes. |

| Cross-Linking [2] | Enzyme molecules linked to each other via bifunctional reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde). | Carrier-free; high enzyme concentration. | Can be rigid; potential for significant activity loss. | Generating robust, carrier-free biocatalyst aggregates. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting an appropriate immobilization technique based on enzyme properties and application goals.

Application Notes: Protocol for Covalent Immobilization on Functionalized Supports

This protocol details the covalent immobilization of an enzyme onto an epoxy-functionalized methacrylate support (e.g., ECR8204M), a method known for creating highly stable biocatalysts suitable for continuous industrial processes [10].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Covalent Immobilization

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | The biological catalyst to be immobilized. | Purified Lipase CalB (33 kDa) or other target enzyme. |

| Epoxy-Activated Support | Carrier for immobilization. Provides functional groups for stable covalent attachment. | ECR8204M resin (hydrophilic methacrylate with epoxide groups) [10]. |

| Buffer Solution | Provides optimal pH environment for enzyme activity and immobilization. | 10-100 mM Phosphate or Carbonate buffer, pH 7.0-8.5. |

| Glutaraldehyde (Optional) | A bifunctional cross-linker used for pre-activation of supports or additional cross-linking. | 2-5% (v/v) solution in immobilization buffer [2]. |

| Washing Solutions | Removes unbound enzyme and reaction by-products. | Immobilization buffer, followed by buffer with 1M NaCl. |

| Blocking Agent | Quenches unreacted functional groups on the support after immobilization. | 1M Ethanolamine, pH 8.0, or 1% (w/v) Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). |

Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Support Preparation

Weigh out an appropriate amount of dry epoxy-functionalized support (e.g., 1 g). Hydrate and wash the support with 3 volumes of deionized water, followed by 3 volumes of the chosen immobilization buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5) to equilibrate the matrix.

Step 2: Enzyme Binding

- Dissolve the purified enzyme in the immobilization buffer to a known concentration (e.g., 5-20 mg/mL).

- Combine the enzyme solution with the pre-equilibrated support in a ratio of 10:1 to 20:1 (v/w) solution to support.

- Incubate the mixture with gentle agitation (e.g., on a rotary shaker) at 25°C for a defined period, typically 4-24 hours, to allow for covalent coupling between the enzyme's amino groups (e.g., lysine residues) and the support's epoxy groups [2].

Step 3: Washing and Blocking

- After incubation, separate the immobilized enzyme from the solution by filtration or mild centrifugation.

- Wash the solid biocatalyst thoroughly with immobilization buffer to remove physically adsorbed enzyme. A subsequent wash with 1M NaCl in buffer can remove ionically bound enzyme.

- To block any remaining unreacted epoxy groups on the support, incubate the immobilized enzyme with 1M ethanolamine (pH 8.0) for 2-4 hours. This step prevents non-specific binding during subsequent use.

Step 4: Storage

Wash the final immobilized enzyme preparation with storage buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) and store at 4°C until use.

Advanced Visualization and Characterization Protocol

Understanding the enzyme's distribution within the carrier bead is crucial for diagnosing performance issues, such as diffusion limitations. The following protocol uses Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) microscopy to visualize enzyme interactions with hydrophobic and hydrophilic carriers [10].

Materials and Reagents

- Immobilized enzyme beads (e.g., CalB on ECR1030M and ECR8204M) [10].

- Paraffin wax (histology-grade).

- Rotary microtome.

- 3D-printed microscopy slides or standard IR-transparent windows (e.g., BaF₂).

- FT-IR microscope with a benchtop IR light source.

Experimental Workflow for FT-IR Microscopy

Step 1: Sample Embedding

Embed the immobilized enzyme beads in histology-grade paraffin wax to provide structural integrity for sectioning.

Step 2: Sectioning

Use a rotary microtome to slice the embedded beads into thin sections (e.g., 10 µm thickness).

Step 3: Mounting

Mount the resulting sections on 3D-printed microscopy slides or standard IR-transparent windows.

Step 4: IR Spectral Acquisition

Using the FT-IR microscope, acquire full transmission IR spectra (spectral range 4000–600 cm⁻¹) across the diameter of the carrier bead section. Record spectra at sequential steps (e.g., 10 µm intervals). The presence of the enzyme is monitored via the absorbance of the amide I band at approximately 1658 cm⁻¹ [10].

Step 5: Data Analysis

Plot the background-corrected absorbance at 1658 cm⁻¹ as a function of the location along the bead's diameter. This generates an enzyme distribution profile, revealing whether the enzyme is confined to the outer surface or has penetrated uniformly throughout the carrier.

Expected Results and Interpretation

As demonstrated in the study, the interaction between the enzyme and carrier is heavily influenced by hydrophobicity [10]:

- Hydrophobic Carriers (e.g., ECR1030M): Immobilization occurs rapidly, forming a dense enzyme layer (~50-70 µm thick) on the external surface of the bead, with minimal penetration into the core. This can lead to higher specific activity but may be prone to surface inactivation or shedding.

- Hydrophilic/Covalent Carriers (e.g., ECR8204M): The enzyme penetrates and binds uniformly throughout the entire bead, resulting in a more robust and stable preparation with a lower risk of enzyme loss, though potentially with higher diffusion resistance.

This characterization is essential for diagnosing the kinetic performance and long-term stability of the immobilized enzyme, enabling researchers to rationally select and optimize the carrier-immobilization system for their specific industrial application.

Historical Evolution and Key Milestones in Immobilization Technology

Immobilization technology represents a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, enabling the transformation of enzymes from soluble, single-use catalysts into robust, reusable systems integral to industrial and pharmaceutical applications. This technology confines enzymes to a defined space, preserving their catalytic activity while granting the operational advantages of a heterogeneous catalyst, such as easy separation, reusability, and enhanced stability [11]. The drive for sustainable and economically viable industrial processes has propelled the evolution of immobilization from simple adsorption techniques to sophisticated methods leveraging nanotechnology and artificial intelligence [12] [13]. This article details the historical progression, key methodologies, and practical protocols of enzyme immobilization, providing a structured resource for researchers and drug development professionals working within the broader context of industrial enzyme applications.

Historical Evolution and Key Milestones

The development of immobilization technology spans over a century, marked by significant methodological breakthroughs and the advent of novel support materials.

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Enzyme Immobilization Technology

| Time Period | Key Milestones and Paradigm Shifts | Representative Supports and Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| Mid-20th Century | Initial development of basic techniques: adsorption and covalent binding [14]. | Inert polymers, inorganic materials, glass, polysaccharide derivatives [14]. |

| 1960s-1970s | Technology popularization; expansion of covalent binding methods and introduction of entrapment techniques [12] [11]. | CNBr-activated Sepharose, collagen, (\kappa)-carrageenan [14]. |

| 1980s-1990s | Optimization of existing methods; focus on enzyme stability and carrier functionalization [15]. | Agarose, porous silica, synthetic polymers [1]. |

| 2000s-2010s | Rise of nanomaterials as supports; development of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) [16] [13]. | Nanofibers, magnetic nanoparticles, mesoporous silica [14] [13]. |

| 2020s-Present | Integration of advanced frameworks and AI-driven design; focus on multifunctional systems [12] [17]. | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs), 3D-printed scaffolds [12] [17] [13]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and evolution of the primary immobilization strategies:

Established Immobilization Techniques: Mechanisms and Protocols

Physical Adsorption

Principle: This simplest and oldest method relies on weak physical forces—such as hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic ionic bonding—to attach enzymes to the surface of a solid support [16] [11]. Its key advantage is the absence of harsh chemicals, which typically preserves high enzyme activity. However, the binding is weak, often leading to enzyme leakage from the support under changing operational conditions like pH or ionic strength [16] [11].

Protocol: Adsorption of Lipase on Polypropylene-Based Granules (e.g., Accurel EP-100) [14]

- Step 1: Support Preparation. Weigh 1 gram of the hydrophobic polymer granules. Wash the support with 20 mL of ethanol, followed by rinsing with 50 mL of distilled water. Dry the granules at room temperature.

- Step 2: Enzyme Loading. Prepare 10 mL of lipase solution in a 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Add the pre-washed granules to the enzyme solution. Incubate the mixture with gentle shaking (120 rpm) at 4°C for 2-4 hours to allow for physical adsorption.

- Step 3: Washing and Recovery. Separate the immobilized enzyme by filtration. Wash thoroughly with the same phosphate buffer to remove any unbound enzyme. The immobilized lipase can be stored at 4°C or used directly for biocatalysis in organic synthesis. This protocol can achieve over 94% residual activity and reusability for up to 12 cycles with certain supports [14].

Covalent Binding

Principle: This technique involves forming stable covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme surface (e.g., amino, carboxyl, thiol, hydroxyl) and reactive groups on a functionalized support [1] [11]. It provides a very stable conjugate, minimizing enzyme leakage. A potential drawback is the risk of enzyme inactivation if the covalent modification occurs at or near the active site [11].

Protocol: Covalent Immobilization on Epoxy-Activated Supports [1]

- Step 1: Support Activation. (If the support is not pre-activated) The chosen support (e.g., sepharose) is often activated with cyanogen bromide (CNBr) or other agents to create reactive epoxy or aldehyde groups [14].

- Step 2: Enzyme Coupling. Dissolve the enzyme in a 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 8.5–9.0). Mix the enzyme solution with the activated support. Incubate the mixture for 12-24 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. The high pH facilitates the nucleophilic attack of the enzyme's amino groups on the epoxy rings.

- Step 3: Blocking and Washing. After coupling, block any remaining reactive groups on the support by adding 1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) and incubating for 4-6 hours. Wash the immobilized enzyme sequentially with the coupling buffer, a high-salt buffer (e.g., 1 M NaCl), and finally with the storage or reaction buffer to remove any adsorbed, non-covalently bound enzyme.

Entrapment and Encapsulation

Principle: This method physically confines enzymes within the interstices of a porous polymer matrix (entrapment) or within a semi-permeable membrane (encapsulation) [1] [16]. The pore size allows substrates and products to diffuse freely while retaining the enzyme. While it generally causes minimal conformational change, it can introduce mass transfer limitations [16].

Protocol: Entrapment in Alginate-Calcium Beads [1]

- Step 1: Polymer-Enzyme Mixture. Prepare a 2-4% (w/v) sodium alginate solution in a suitable buffer. Gently mix this solution with an equal volume of enzyme solution to form a homogeneous suspension.

- Step 2: Gel Bead Formation. Using a syringe with a needle, drop the polymer-enzyme mixture into a 0.1 M calcium chloride (CaCl₂) solution. The divalent calcium ions cross-link the alginate polymer chains instantaneously, forming stable gel beads with the enzyme trapped inside.

- Step 3: Curing and Washing. Allow the beads to cure in the CaCl₂ solution for 30 minutes to ensure complete gelation. Harvest the beads by filtration and wash them with buffer to remove excess Ca²⁺ ions and enzyme on the surface.

Cross-Linking

Principle: This carrier-free strategy uses bifunctional reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde) to cross-link enzyme molecules with each other, forming insoluble aggregates known as Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) [12] [13]. This method offers high enzyme stability and loading but may reduce activity if cross-linking is excessive.

Protocol: Preparation of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) [13]

- Step 1: Enzyme Precipitation. To a solution of the target enzyme, slowly add a precipitant such as ammonium sulfate or tert-butanol under constant stirring. The enzyme will precipitate out of solution as fine aggregates. Centrifuge the mixture to collect the aggregates.

- Step 2: Cross-Linking. Re-suspend the wet enzyme aggregates in a small volume of buffer. Add a cross-linking agent, typically glutaraldehyde, to a final concentration of 1-5 mM. Stir the suspension gently for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Step 3: Product Recovery. Stop the reaction by centrifugation and wash the resulting CLEAs thoroughly with buffer to remove any unreacted cross-linker. The CLEAs can be stored as a suspension or in a lyophilized form.

Table 2: Comparison of Classic Immobilization Techniques

| Technique | Binding Force | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Weak physical interactions (Hydrophobic, ionic) [11] | Simple, inexpensive, high activity retention [16] | Enzyme leakage, non-specific binding [11] | Rapid screening, single-batch processes |

| Covalent Binding | Strong covalent bonds [1] | Very stable, no leakage, reusable [18] | Potential activity loss, complex protocol, expensive [11] | Continuous processes in harsh environments |

| Entrapment/Encapsulation | Physical confinement in a lattice [1] | No chemical modification, protects enzyme [1] | Mass transfer limitations, enzyme leaching from large pores [16] | Biosensors, food processing with sensitive enzymes |

| Cross-Linking (CLEAs) | Covalent bonds between enzyme molecules [13] | High stability & enzyme loading, carrier-free, cost-effective [12] [13] | Potential for over-cross-linking and activity loss [12] | Industrial biocatalysis where support cost is prohibitive |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Enzyme Immobilization Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Support Materials | Octyl-agarose, Sepabeads [14], Mesoporous Silica (SBA-15) [14], Chitosan [12], Alginate [1], Metal-Organic Frameworks (ZIF-8) [17] | Provides a high-surface-area solid phase for enzyme attachment or entrapment. Choice dictates loading capacity, stability, and mass transfer. |

| Activation Agents/Cross-linkers | Glutaraldehyde [13], Cyanogen Bromide (CNBr) [14], Divinyl sulfone [13], 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) [16] | Activates inert support surfaces or creates covalent links between enzyme molecules and the support or between enzymes (in CLEAs). |

| Precipitants (for CLEAs) | Ammonium sulfate, tert-Butanol, Polyethylene glycol (PEG) [13] | Causes the enzyme to aggregate out of solution, forming a physical concentrate ready for cross-linking. |

| Buffers | Phosphate Buffer (for adsorption), Carbonate Buffer (pH 8.5-9.0 for covalent binding) [1] | Maintains optimal pH during the immobilization process to ensure enzyme stability and efficient binding. |

Advanced and Emerging Immobilization Strategies

The frontier of immobilization technology is defined by precision engineering and intelligent design.

- Nanomaterial Carriers: Nanoparticles, nanofibers, and graphene oxide provide exceptionally high surface area-to-volume ratios, drastically increasing enzyme loading and reducing mass transfer barriers [16] [12]. Magnetic nanoparticles, for instance, facilitate easy separation of the biocatalyst using an external magnetic field [12].

- Hybrid Porous Frameworks: Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) are crystalline porous materials with tunable pore environments [17] [13]. They allow for enzyme immobilization via pore adsorption or in-situ encapsulation, offering superior protection against denaturing conditions like organic solvents and high temperatures.

- Carrier-Free Systems: Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) remain a popular carrier-free format due to their high stability and simplicity [13]. Recent innovations include magnetic CLEAs (mCLEAs) for easy separation and combi-CLEAs for multi-enzyme cascade reactions [13].

- AI and Smart Systems: Artificial intelligence and machine learning are now being deployed to predict optimal immobilization conditions, design novel support materials, and model the performance of immobilized enzymes, accelerating research and development cycles [12]. The future points towards "smart" biocatalysts that can dynamically respond to environmental stimuli [13].

Application Notes for Industrial and Pharmaceutical Contexts

The choice of immobilization technique is critically dependent on the final application.

- Pharmaceutical API Synthesis: The synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), such as sitagliptin, often employs immobilized engineered transaminases via covalent binding. This provides the extreme operational stability and high enantioselectivity (>99.5% e.e.) required for pharmaceutical manufacturing, often in the presence of organic co-solvents like DMSO [18].

- Industrial Biocatalysis: For processes like the production of the herbicide Dimethenamide-P, immobilized lipase B from Candida antarctica (CalB) is used in column reactors. This setup enables continuous operation in organic solvents, high productivity, and excellent stereoselectivity, offering a green alternative to traditional chemical synthesis [18].

- Biosensing and Biofuel Production: Entrapment within polymeric membranes or encapsulation in silica gels is suitable for biosensors and biofuel production, where the enzyme needs to be protected while allowing rapid diffusion of small molecules [1]. CLEAs are also extensively explored for biomass conversion in bioethanol production [13].

The experimental workflow for developing an immobilized enzyme system for industrial use involves multiple critical steps, as visualized below:

The efficacy of immobilized enzyme systems in industrial applications is governed by a fundamental framework: the Enzyme-Support-Mode Interaction Triangle. This paradigm illustrates that optimal biocatalyst performance emerges from the precise interplay between the enzyme (biological catalyst), the support (immobilization matrix), and the mode (method of immobilization). Individually, each component possesses specific characteristics; collectively, they determine critical performance parameters such as activity, stability, specificity, and reusability. Understanding these interactions is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals designing immobilized enzyme systems for manufacturing therapeutics, biosensors, and fine chemicals. The selection of one component directly influences and constrains the choices for the other two, creating a tightly coupled design space that requires systematic optimization [14].

The Support Component: Immobilization Matrices

The support matrix provides the physical foundation for enzyme immobilization, creating a microenvironment that can either stabilize or denature the enzyme structure. An ideal support matrix must be chemically inert, physically robust, stable under operational conditions, and cost-effective [14]. The surface chemistry and morphology of the support directly influence enzyme loading, stability, and accessibility to substrates.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Support Matrices

| Support Material | Type | Key Properties | Impact on Enzyme | Common Industrial Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octyl-Agarose | Natural Polymer | Hydrophobic, macroporous [14] | Enhances affinity for hydrophobic substrates, increases stability [14] | Lipase purification and activation |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) | Inorganic | Tunable pore size, high surface area, long-term durability [14] | Mitigates diffusion limitation, high activity retention [14] | Biocatalysis in energy applications |

| Chitosan | Natural Polymer | Biocompatible, amenable to chemical modification [14] | Enhances thermal stability and enzyme-binding capacity [14] | Affinity adsorbents for simultaneous purification and immobilization |

| Electrospun Nanofibers | Synthetic/Composite | High surface-area-to-volume ratio, high porosity [14] | Increases residual activity due to greater enzyme loading [14] | High-density enzyme immobilization for biosensing |

| Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) | Biodegradable Polymer | Eco-friendly, less tough and crystalline [14] | High residual activity and reusability [14] | Environmentally friendly biocatalytic processes |

| Molecular Sieves (Silanized) | Inorganic | Silanols on pore walls facilitate hydrogen bonding [14] | Stable enzyme immobilization, shielded from aggregation [14] | Reduction and oxidation reactions |

The Mode Component: Immobilization Techniques

The immobilization technique defines the nature of the bond between the enzyme and the support. The choice of mode impacts not only the strength of attachment but also the enzyme's conformation, freedom of movement, and accessibility of its active site.

Covalent Binding

Covalent binding involves forming stable chemical bonds between functional groups on the enzyme (e.g., amino, carboxyl, phenolic) and reactive groups on the support [14]. This method often employs cross-linking agents like glutaraldehyde to create stable inter- and intra-subunit bonds, resulting in highly stable, non-leaching preparations with prolonged operational lifetime [14]. The method's drawback is potential loss of activity due to conformational changes or modification of active site residues.

Adsorption

Adsorption relies on weak, non-covalent interactions such as hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, and ionic linkages [14]. This simple, cost-effective method preserves high enzyme activity as it causes minimal conformational disruption. However, the binding is weak, leading to enzyme leakage upon changes in pH, ionic strength, or temperature, limiting its industrial applicability.

Affinity Immobilization

This sophisticated technique exploits the specific biological recognition between the enzyme and an affinity ligand pre-attached to the support [14]. Bioaffinity layering can exponentially increase enzyme-binding capacity and reusability. It allows for simultaneous purification and immobilization, yielding highly active and stable preparations, though the supports are often more expensive [14].

Entrapment

Entrapment physically cages enzymes within the interstitial spaces of a polymer network (e.g., alginate, gelatin-calcium hybrids) without direct binding [14]. This protects enzymes from proteolysis and denaturation by creating a sheltered microenvironment. A significant challenge is diffusion limitation, where substrate access and product egress are hindered, reducing observed reaction rates.

Table 2: Comparison of Immobilization Techniques

| Immobilization Mode | Binding Force | Stability | Risk of Activity Loss | Cost | Ideal for Enzymes That Are: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Binding | Covalent bonds | Very High | Moderate to High | Moderate | Stable to chemical modification |

| Adsorption | Hydrophobic, Ionic | Low | Low | Low | Sensitive to conformational change |

| Affinity Immobilization | Bio-specific | High | Low | High | Requiring specific orientation/purification |

| Entrapment | Physical barrier | Moderate | Low | Low | Small, and used with small substrates |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Covalent Immobilization on Epoxy-Activated Supports

This protocol details the covalent immobilization of an enzyme onto sepabeads, a common epoxy-activated support, ideal for achieving high operational stability [14].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Epoxy-Activated Support (e.g., Sepabeads) | Matrix providing stable covalent linkage via epoxy groups. |

| Enzyme Purification Buffer (e.g., 50mM Phosphate, pH 7.0) | Provides a stable chemical environment for the enzyme. |

| Coupling Buffer (e.g., 1M Potassium Phosphate, pH 8.0) | High ionic strength buffer to promote enzyme-support interaction. |

| Blocking Solution (1M Ethanolamine, pH 8.0) | Deactivates unreacted epoxy groups post-immobilization. |

| Washing Buffer (Coupling Buffer + 1M NaCl) | Removes non-covalently adsorbed enzyme. |

Methodology:

- Preparation: Wash 1 gram of epoxy-activated support sequentially with distilled water and coupling buffer.

- Immobilization: Incubate the prepared support with 10-20 mL of enzyme solution (5-10 mg/mL in coupling buffer) under gentle agitation for 24 hours at 25°C.

- Blocking: Recover the immobilized enzyme by filtration and incubate with 10 mL of 1M ethanolamine (pH 8.0) for 4 hours at 25°C to block any remaining epoxy groups.

- Washing: Wash the preparation extensively with coupling buffer, followed by washing buffer (to remove ionically adsorbed enzyme), and finally with the standard assay buffer.

- Activity Assay: Determine the activity of the immobilized enzyme and the supernatant to calculate immobilization yield and expressed activity. The activity should be measured in triplicate to ensure reproducibility [19].

- Storage: Store the final preparation at 4°C in an appropriate buffer.

Protocol: Determining Inhibition Modality via IC₅₀ Replots

Understanding inhibition modality is critical in drug discovery. This protocol uses IC₅₀ shifts at varying substrate concentrations to diagnose the mode of enzyme-inhibitor interaction [20].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Target Enzyme | The protein of interest (e.g., kinase, protease). |

| Inhibitor Compound | The small molecule whose mode of action is being characterized. |

| Substrate | The natural molecule converted by the enzyme. |

| Reaction Buffer | Buffered solution at optimal pH for enzyme activity. |

| Detection Reagents | reagents to quantify reaction rate (e.g., NADH, chromogenic substrate). |

Methodology:

- Experimental Setup: For a given inhibitor concentration, measure the initial reaction rate at a minimum of six substrate concentrations, spanning values below and above the known Kₘ. Perform each measurement in triplicate to assess precision [19].

- IC₅₀ Determination: Repeat step 1 for at least six different inhibitor concentrations. For each inhibitor concentration, fit the rate vs. substrate concentration data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (or appropriate inhibition model) using nonlinear regression software to obtain apparent Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ values [19].

- Data Analysis: Plot the initial reaction rate against the logarithm of inhibitor concentration for each substrate level. Fit the data to a sigmoidal dose-response curve to determine the IC₅₀ value at each substrate concentration.

- Diagnostic Replot: Create a secondary plot of the measured IC₅₀ values as a function of the substrate concentration normalized to Kₘ ([S]/Kₘ).

- Mode Identification: Analyze the replot pattern [20]:

- Competitive Inhibition: IC₅₀ increases linearly with increasing [S]/Kₘ.

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: IC₅₀ decreases with increasing [S]/Kₘ.

- Non-competitive/Mixed Inhibition: IC₅₀ changes but does not follow the patterns above.

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: A systematic workflow for selecting and optimizing the components of the Enzyme-Support-Mode Interaction Triangle for industrial application development.

Figure 2: A detailed experimental workflow for determining enzyme inhibition modality through the analysis of IC₅₀ shifts at varying substrate concentrations, a key technique in drug discovery. [20]

The selection of an appropriate support material is a critical determinant in the success of enzyme immobilization for industrial biocatalysis. An ideal support must concurrently fulfill multiple physicochemical and biological criteria to enhance the immobilized enzyme's stability, activity, reusability, and cost-effectiveness [9] [21]. These properties directly influence the catalytic performance and operational lifespan of the biocatalyst in applications ranging from pharmaceutical synthesis to biofuel production [4] [22]. This document outlines the essential properties of support materials, provides a comparative analysis of common support types, and details standardized protocols for evaluating these key characteristics within a research setting.

Essential Properties of Ideal Support Materials

The performance of an immobilized enzyme system hinges on the properties of its support material. The following properties are considered fundamental for an ideal support [9] [21] [22]:

- Biocompatibility: The support material must be non-toxic and not induce denaturation or conformational changes that impair enzymatic activity. It should provide a favorable microenvironment for the enzyme [23] [22].

- Mechanical Strength: The carrier must exhibit sufficient resistance to compression, shear forces, and abrasion to withstand the hydrodynamic conditions and physical stresses of industrial reactors, especially in continuous fixed-bed operations [9] [21].

- Chemical Stability: The support should be inert and stable under the operational conditions of the process, including extremes of pH, temperature, and the presence of organic solvents or other chemicals [9] [21].

- High Surface Area & Porosity: A large surface area, often provided by a mesoporous structure, permits higher enzyme loading per unit mass. Controlled pore distribution is crucial for optimizing binding capacity, substrate diffusion, and flow properties [9] [24].

- Ease of Functionalization: The surface should possess or be readily modified with functional groups (e.g., amino, carboxyl, epoxy) to facilitate strong and stable attachment of the enzyme via various immobilization chemistries [9] [23].

- Hydrophilicity: A hydrophilic surface is generally preferred as it helps to maintain the essential water layer around the enzyme, preserving its catalytically active tertiary structure [9].

- Cost-Effectiveness and Availability: The material should be readily available, inexpensive, and ideally reusable to ensure the economic viability of the immobilization process on an industrial scale [9] [2].

Table 1: Key Properties and Their Impact on Immobilized Enzyme Performance

| Property | Description | Impact on Immobilized Enzyme |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Non-toxic and does not denature the enzyme [23]. | Preserves catalytic activity and prevents enzyme inactivation. |

| Mechanical Strength | Resistance to compression and shear forces [9]. | Ensures long-term structural integrity in industrial bioreactors. |

| Chemical Stability | Inertness across a range of pH, temperatures, and solvents [21]. | Enables application in diverse and harsh industrial processes. |

| High Surface Area & Porosity | Large surface area and controlled pore distribution (e.g., mesoporous) [9] [24]. | Increases enzyme loading capacity and minimizes diffusion limitations. |

| Ease of Functionalization | Availability of reactive functional groups for binding [9]. | Allows for robust and stable enzyme attachment via multiple methods. |

| Hydrophilicity | Hydrophilic surface character [9]. | Maintains the enzyme's hydration shell and native conformation. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Low cost and ready availability [2]. | Essential for scalable and economically feasible industrial applications. |

Comparative Analysis of Support Material Classes

Support materials can be broadly categorized into organic (natural and synthetic polymers) and inorganic (porous and non-porous) materials. The emergence of nanomaterials and advanced composites has further expanded the options available to researchers [9] [22].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Support Material Classes for Enzyme Immobilization

| Material Class | Examples | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Chitosan, alginate, cellulose, collagen [21] [2]. | Biocompatible, biodegradable, low cost, abundant [2] [22]. | Variable mechanical strength, susceptibility to microbial degradation [9]. |

| Synthetic Polymers | Polyacrylamide, epoxy resins, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) [21] [23]. | High mechanical/chemical stability, tunable properties [21]. | Potential toxicity of monomers, low biocompatibility, non-biodegradable [9]. |

| Inorganic Porous Materials | Silica, porous glass, zeolites, hydroxyapatite [9] [2]. | High mechanical strength, thermal stability, controlled porosity [9] [23]. | Brittleness, high density, limited functionalization without modification [9]. |

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials | Carbon nanotubes, graphene [24] [22]. | Very high surface area, excellent electrical/thermal conductivity [24]. | High cost, potential toxicity, complex preparation and functionalization [24]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) [24] [23]. | Easy separation & recovery via magnetic field, high surface area [24] [22]. | Can aggregate, may degrade in acidic/oxidative environments [24]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) & Crystalline Porous Organic Frameworks (CPOFs) | ZIF series, COFs, HOFs [4] [25]. | Extremely high surface area, precisely tunable pore size, designable functionality [25]. | Complex synthesis, cost, stability in water/acids/bases can be limited [25]. |

Support Material Selection Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Support Materials

Protocol: Determination of Surface Area and Porosity

Principle: The surface area and pore characteristics of a support material are determined from nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms measured at 77 K, typically using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method for surface area and the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method for pore size distribution [9].

Materials:

- High-purity nitrogen gas

- Liquid nitrogen

- Degassed sample of the support material

- Surface area and porosity analyzer (e.g., Micromeritics ASAP series, Quantachrome Autosorb series)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh approximately 0.1-0.3 g of the support material. Place it in a sample tube and degas under vacuum at a suitable temperature (e.g., 120°C for silica) for a minimum of 6 hours to remove moisture and adsorbed contaminants.

- Analysis: Transfer the sample tube to the analysis port. The instrument will automatically cool the sample to 77 K using liquid nitrogen and expose it to nitrogen gas at a series of precisely controlled pressures.

- Data Collection: The instrument measures the volume of nitrogen gas adsorbed onto and desorbed from the sample surface at each pressure point, generating an adsorption-desorption isotherm.

- Data Analysis: Use the instrument's software to apply the BET model to the relative pressure (P/P₀) range of 0.05-0.30 to calculate the specific surface area. Apply the BJH model to the desorption branch of the isotherm to determine the pore size distribution and total pore volume.

Reporting: Report the specific surface area in m²/g, the average pore diameter in nm, and the total pore volume in cm³/g. A mesoporous material ideal for enzyme immobilization typically has a pore diameter between 2-50 nm [9].

Protocol: Assessment of Mechanical Stability via Compressibility Testing

Principle: This test evaluates the resistance of support materials to crushing forces, simulating the physical stresses encountered in packed-bed reactors [9].

Materials:

- Universal Testing Machine (UTM) equipped with a flat-plate compression fixture

- Precision balance

- Cylindrical mold (if forming pellets is necessary)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: If the support is a powder, it may be pressed into a pellet of defined dimensions (e.g., 5 mm diameter, 3 mm thickness) using a hydraulic press at a standard pressure. Alternatively, a known volume of pre-formed beads can be used.

- Measurement: Place a single pellet or a small, known mass of beads on the lower plate of the UTM. Program the UTM to apply a compressive force at a constant crosshead speed (e.g., 1 mm/min) until the sample fractures or a predefined deformation is reached.

- Data Collection: The instrument software records the applied force (in Newtons, N) and the corresponding displacement (in mm).

Data Analysis: The mechanical strength is reported as the crushing strength, which is the maximum force (N) sustained by the particle before failure. For a more standardized value, the crushing strength can be divided by the particle's diameter to report strength in N/mm.

Protocol: Evaluation of Chemical Stability

Principle: This protocol assesses the structural integrity and mass loss of the support material when exposed to various chemical environments relevant to the intended biocatalytic process [21].

Materials:

- Buffers at different pH values (e.g., pH 4.0, 7.0, 9.0)

- Organic solvents (e.g., methanol, hexane, isopropanol)

- Analytical balance (0.1 mg precision)

- Oven

- Desiccator

Procedure:

- Initial Weighing: Accurately weigh a sample of the dry support material (W₁, ~1.0 g) in a pre-weighed vial.

- Incubation: Add 20 mL of the test solution (buffer or solvent) to the vial. Seal the vial and incubate in a shaking incubator at the operational temperature (e.g., 30°C or 50°C) for 24-72 hours.

- Final Weighing: After incubation, carefully decant the solution. Wash the solid support with a volatile, miscible solvent (e.g., acetone) if needed, and dry to constant weight in an oven. Let the sample cool in a desiccator and record the final dry weight (W₂).

Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage mass loss using the formula: Mass Loss (%) = [(W₁ - W₂) / W₁] × 100 A support with good chemical stability will show minimal mass loss (<5%) under its intended operational conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Support Material Evaluation and Enzyme Immobilization

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles | High-surface-area inorganic support for adsorption/covalent binding [23]. | Particle size: 50-200 nm; Pore size: 5-10 nm; Surface area: >500 m²/g. |

| Chitosan | Biocompatible, biodegradable natural polymer support; easily functionalized [21] [2]. | Medium molecular weight; Deacetylation degree ≥75%. |

| Epoxy-Activated Agarose | Robust support for covalent immobilization; stable, hydrophilic [2]. | Bead size: 50-150 μm; Epoxy density: ~20 μmol/mL settled gel. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) | Enable easy biocatalyst recovery via magnetic separation [24] [22]. | Core-shell structure (e.g., Fe₃O₄@SiO₂); diameter: 20-50 nm. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinker for activating amine-bearing supports and creating covalent enzyme bonds [2]. | 25% Aqueous solution, molecular biology grade. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Crystalline supports with ultra-high surface area and tunable pores [25]. | Pore size tailored to target enzyme (e.g., 3-8 nm). |

| Eupergit C | Macroporous copolymer beads for stable covalent enzyme immobilization [2]. | Oxirane content: ~0.8 mmol/g. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Nanoscale support with high conductivity and surface area [9] [24]. | Single or multi-walled; functionalized with -COOH or -NH₂ groups. |

Industrial Immobilization Methods and Their Pharmaceutical Applications

Enzyme immobilization is a cornerstone of industrial biocatalysis, enhancing enzyme reusability, stability, and simplifying downstream processing [16]. Among the various techniques, physical adsorption stands out for its straightforwardness and wide applicability. This method involves the confinement of an enzyme to a solid phase different from that of the substrates and products, utilizing weak physical forces to bind the enzyme to a support matrix [14] [26]. For industrial applications, where cost-effectiveness and operational simplicity are paramount, physical adsorption offers a compelling strategy for developing robust immobilized enzyme systems. This application note provides a detailed overview of the technique, its quantitative performance, and a standardized protocol for implementation.

Mechanism and Characteristics of Physical Adsorption

Physical adsorption relies on non-covalent, intermolecular interactions between the enzyme and the surface of the support material. These interactions primarily include van der Waals forces, hydrophobic effects, and hydrogen bonds [26] [16]. Unlike covalent methods, no chemical linkers or surface modifications are strictly necessary, which helps preserve the native structure and catalytic activity of the enzyme [16].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and the key interactions involved in the enzyme immobilization process via physical adsorption.

Comparative Analysis of Immobilization Techniques

Selecting an appropriate immobilization strategy requires balancing factors such as activity retention, stability, and cost. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of physical adsorption with other common techniques, highlighting its characteristic profile of high enzyme loading and simple operation, albeit with a potential risk of enzyme leaching.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Enzyme Immobilization Strategies

| Immobilization Technique | Binding Force | Typical Activity Retention | Operational Stability | Risk of Enzyme Leaching | Relative Cost & Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Adsorption | Van der Waals, Hydrophobic, Hydrogen bonds [26] [16] | High (Structure not modified) [26] | Moderate (Sensitive to pH, ionic strength) [26] | High [16] | Low [16] |

| Covalent Binding | Covalent bonds [14] | Variable (Can be low due to active site involvement) [16] | High [14] [16] | Very Low [16] | High [16] |

| Entrapment/ Encapsulation | Physical confinement within a polymer network [14] [16] | High to Moderate [16] | High [27] | Low [16] | Moderate [16] |

| Cross-Linking | Covalent bonds between enzyme molecules [14] [16] | Often limited [16] | High [14] | Very Low | Moderate [16] |

Note: The performance metrics are highly dependent on the specific enzyme-support system and immobilization conditions. Data is synthesized from comparative studies. [14] [27] [16]

A specific study comparing glucose oxidase immobilization for biosensing demonstrated that while hydrogel entrapment provided the most stable and sensitive biosensors, adsorption-based biosensors, though functional, showed poor sensitivity and unstable performance [27]. This underscores the need to align the technique with the application's requirements.

Support Materials for Physical Adsorption

The choice of support is critical to the success of the immobilization process. An ideal matrix should be affordable, physically robust, and have a high surface area for enzyme binding [14]. The following table catalogs common and advanced support materials used in adsorption.

Table 2: Overview of Support Materials for Physical Adsorption

| Support Material | Type | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Supports | Synthetic/ Natural | Alumina, Silica Gel, Calcium Phosphate Gel, Glass, Kaolin [26]. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs): Long-term durability, large surface area [14]. Molecular Sieves: Silanols on pore walls facilitate hydrogen bonding [14]. |

| Organic Polymeric Supports | Natural/ Synthetic | Polypropylene-based granules (e.g., Accurel EP-100): Hydrophobic, good for lipases, smaller particle sizes increase reaction rates [14]. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate): Biodegradable, shown 94% residual activity after 4h at 50°C and reusability for 12 cycles [14]. Starch, Cellulose derivatives (CM-cellulose, DEAE-cellulose), Chitosan [26]. |

| Nanomaterial Supports | Engineered | Electrospun Nanofibers: High surface area and porosity, can lead to greater residual activity [14]. Magnetic Nanoclusters: Enhanced longevity, operational stability, reusability, easy separation [14] [16]. Coconut Fibers: Eco-friendly, good water-holding capacity, high cation exchange [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Adsorption of Enzymes on Solid Supports

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Solid Support (e.g., Mesoporous Silica, Accurel EP-100, Chitosan) | Provides a high-surface-area matrix for enzyme attachment via physical forces. |

| Enzyme of Interest (Lyophilized powder or pure solution) | The biocatalyst to be immobilized. |

| Buffer Solution (e.g., 0.1 M Sodium Citrate, Phosphate Buffer) | Maintains optimal pH for enzyme stability and binding during immobilization. |

| Orbital Shaker Incubator | Provides agitation to ensure uniform contact between the enzyme and support. |

| Centrifuge or Magnetic Separator (for magnetic supports) | Separates the immobilized enzyme from the free enzyme and washing solutions. |

| Lyophilizer (Freeze Dryer) | For drying and long-term storage of the final immobilized enzyme preparation. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

This protocol describes the adsorption of an enzyme onto a porous solid support, adapted from established procedures in the literature [14] [26].

Step 1: Support Preparation

- Weigh an appropriate amount of dry support material (e.g., 4 mg for small-scale experiments) [26].

- If necessary, pre-wash the support with the immobilization buffer to remove fines and equilibrate it.

Step 2: Enzyme Solution Preparation

- Dissolve the enzyme in a selected buffer (e.g., 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.0 for laccase) to a defined concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL) [26]. The buffer's pH and ionic strength should be optimized for the specific enzyme to ensure stability.

Step 3: Immobilization Procedure

- Suspend the prepared support in the enzyme solution (e.g., 4 mg support in 10 mL enzyme solution) [26].

- Incubate the mixture with constant agitation (e.g., at 100 rpm) at a controlled temperature (typically 25-30°C) for a predetermined time (e.g., 3 hours) to allow for binding equilibrium [26].

Step 4: Washing and Separation

- Separate the solid support with the immobilized enzyme from the liquid. This can be achieved by centrifugation, filtration, or magnetic separation if using magnetic carriers [14] [26].

- Wash the solid thoroughly with the same buffer to remove any unbound or weakly adsorbed enzyme. The washings can be analyzed for protein content to determine immobilization yield.

Step 5: Storage

- The final immobilized enzyme preparation can be lyophilized and stored at 4°C for future use [26].

Critical Parameters for Optimization

- Enzyme/Support Ratio: A ratio of 0.4 mg enzyme per mL of suspension has been shown to yield 91% activity recovery for laccase on a magnetic carbon composite, beyond which activity may drop due to overcrowding [26].

- pH and Ionic Strength: These parameters dramatically influence the charge and conformation of the enzyme and the support, directly affecting adsorption efficiency and stability. Low ionic strength can enhance adsorption capacity [26].

- Time and Temperature: Sufficient time is required to reach binding equilibrium. While increased temperature can enhance adsorption forces, it must be balanced against the risk of enzyme denaturation [26].

Physical adsorption remains a highly valuable immobilization technique due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to achieve high enzyme loadings with minimal impact on catalytic activity. While challenges such as enzyme leaching under shifting operational conditions persist, the strategic selection of supports—especially modern nanomaterials and renewable agrowaste carriers—and careful optimization of protocols can yield highly effective and stable biocatalysts [14] [16]. For industrial researchers and drug development professionals, this method provides a versatile and accessible starting point for developing immobilized enzyme systems tailored to diverse bioprocessing needs.

In the pursuit of sustainable industrial biocatalysis, enzyme immobilization has emerged as a cornerstone technology. Among the various techniques available, covalent binding stands out for its ability to produce immobilized enzymes with exceptional operational stability and minimal enzyme leakage, which is paramount for cost-effective processes in the pharmaceutical, food, and fine chemicals industries [28] [5]. This method involves the formation of stable covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme surface and a complementary solid support [3]. Unlike physical adsorption or entrapment, this robust linkage effectively prevents the enzyme from leaching into the reaction mixture, even under harsh operational conditions or in the presence of solvents, thereby ensuring product purity and enabling catalyst reuse over multiple cycles [3] [5]. This application note delineates standardized protocols and critical considerations for implementing covalent immobilization, framed within a broader research context aimed at developing robust biocatalytic systems for industrial applications.

Key Principles and Rationale

Covalent immobilization enhances enzyme stability by creating strong, irreversible attachments. However, this often comes at the cost of some initial activity, as the chemical reaction can involve amino acid residues critical for catalysis or induce conformational changes [28] [5]. The selection of an appropriate immobilization strategy is therefore a critical compromise, dependent on the specific enzyme characteristics, the support material, and the intended application [28].

The most common covalent techniques leverage carbodiimide chemistry and Schiff base reactions, which target functional groups like –NH2 (from lysine residues) and –COOH (from aspartic or glutamic acid residues) that are abundantly present on the enzyme surface [28] [29]. Achieving optimal enzyme orientation on the support is crucial to minimize unnecessary conformational alterations and steric hindrance of the active site, thereby fostering the development of a stable, highly active, and reproducible biocatalyst [28].

Quantitative Performance of Covalently Immobilized Enzymes

The following table summarizes recent data on the operational stability of various enzymes immobilized via covalent strategies, highlighting their performance in terms of reusability and stability.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Covalently Immobilized Enzymes

| Enzyme | Support Material | Immobilization Method | Key Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l-Tyrosine Decarboxylase (LbTDC) | Hydroxyapatite (HAP) | APTES/Glutaraldehyde | Retained significant activity over multiple reaction cycles, demonstrating operational stability and reusability. [30] | |

| R-selective Transaminase (TsRTA) | Hydroxyapatite (HAP) | APTES/Glutaraldehyde | Showed promising stability during reusability tests in repeated batch reactions. [30] | |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Covalent Organic Framework (COF) Microcapsules | Interfacial Assembly & Regrowth | The robust COF shell protected the enzyme from harsh conditions, significantly enhancing stability for biosensing. [31] | |

| Trypsin | Boronate Affinity Monolith | Schiff Base Reaction | Maintained 80% of initial enzyme activity after 28 days of storage at 4°C. [29] |

Standardized Experimental Protocols