Enzyme Kinetic Modeling: A Complete Guide from Foundational Principles to Precision Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to enzyme kinetic modeling for researchers and drug development professionals.

Enzyme Kinetic Modeling: A Complete Guide from Foundational Principles to Precision Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to enzyme kinetic modeling for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the journey from foundational biochemical principles and the derivation of classic equations like Michaelis-Menten to advanced applications in physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and AI-driven parameter prediction. The scope includes practical methodologies for data fitting and model building, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls and optimizing models for complex biological systems, and a critical comparison of different modeling frameworks and validation techniques. By integrating traditional theory with modern computational approaches, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build robust, predictive kinetic models that accelerate therapeutic innovation and enhance the precision of drug development.

Core Principles of Enzyme Catalysis: Mastering the Fundamentals of Kinetic Theory

This technical guide elucidates the dual biochemical pillars of enzymatic catalysis: the precise molecular strategies that lower activation energy and the structural determinants of substrate specificity. Framed within the evolving paradigm of enzyme kinetic modeling research, we dissect the progression from classical Michaelis-Menten formalisms to contemporary variable-order fractional calculus models that incorporate memory effects and time delays for superior predictive power in biological systems [1]. Enzymes achieve extraordinary rate accelerations—from 10³ to 10¹⁷-fold—by stabilizing high-energy transition states through concerted acid-base catalysis, covalent intermediates, and precise substrate orientation within the active site [2] [3]. Specificity, ranging from absolute to group or bond specificity, is governed by the dynamic architecture of the active site via the induced fit model, ensuring metabolic fidelity [4] [5]. This synthesis of mechanism and kinetics provides an indispensable framework for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to modulate enzymatic activity with high precision.

Enzymes are protein catalysts indispensable for life, accelerating biochemical reactions under mild physiological conditions to rates compatible with cellular processes [3]. The study of how they achieve this—through lowering activation energy and binding specific substrates—forms the cornerstone of mechanistic biochemistry. Historically, this understanding has been quantified through enzyme kinetic modeling, most famously the Michaelis-Menten model, which relates reaction velocity to substrate concentration [6] [7].

Today, kinetic modeling is undergoing a significant transformation. While classical models assume reactions depend only on present conditions, modern research recognizes that biological memory effects, time delays from conformational changes, and fractal-like geometries of active sites influence dynamics [1]. This has spurred the development of advanced models using variable-order fractional derivatives, which capture how past system states affect current reaction rates, offering a more nuanced view for applications in drug discovery and bioprocess engineering [1]. This guide bridges the fundamental biochemical principles with these cutting-edge modeling approaches, providing a comprehensive resource for the scientific community.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Activation Energy Lowering

Enzymes function as catalysts by lowering the activation energy (Eₐ) of a chemical reaction, the energy barrier that must be overcome for reactants to convert to products. They achieve this without being consumed or altering the reaction's equilibrium, often accelerating rates by a factor of 10⁶ or more [2] [3]. The following table summarizes the key quantitative impact of enzymes:

Table 1: Magnitude of Enzymatic Rate Enhancement and Key Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Description & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Rate Acceleration | 10³ to 10¹⁷-fold | Factor by which enzymes increase reaction rate over the uncatalyzed reaction [3]. |

| Activation Energy Reduction | Can be reduced to ~1/3 of original value | Enzymes lower the energy required to reach the transition state [2]. |

| Michaelis Constant (Kₘ) | ~10⁻⁶ to 10⁻² M | Substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity. Measures enzyme-substrate affinity [8]. |

| Turnover Number (k_cat) | 0.1 to 10⁶ s⁻¹ | Maximum number of substrate molecules converted per active site per second [8]. |

| Specificity Constant (k_cat/Kₘ) | 10¹ to 10⁸ M⁻¹s⁻¹ | Apparent second-order rate constant for enzyme action on low substrate; best measure of catalytic efficiency [8]. |

The reduction in Eₐ is accomplished through several interconnected mechanisms centered on the formation of a transient enzyme-substrate (ES) complex:

- Transition State Stabilization: The active site is complementary not to the substrate itself, but to the high-energy transition state of the reaction. By forming multiple weak interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions) with this transition state, the enzyme dramatically lowers its free energy, making it much easier to attain [3].

- Provision of an Alternative Reaction Pathway: Enzymes often facilitate reactions through mechanisms involving transient covalent intermediates or acid-base catalysis. For example, in the serine protease chymotrypsin, a catalytic triad (Ser-His-Asp) collaborates to cleave peptide bonds via a covalent acyl-enzyme intermediate, bypassing the need for a highly energetic uncatalyzed hydrolysis [3].

- Substrate Orientation and Proximity Effects: The active site binds substrates in a specific orientation and brings reacting groups into close proximity. This organizes reactants precisely, reducing the entropy penalty and increasing the probability of a productive collision, which would occur rarely in free solution [3] [5].

- Induced Fit and Substrate Strain: Upon substrate binding, many enzymes undergo a conformational change that tightens around the substrate (induced fit). This can distort (strain) the substrate's bonds, bending them toward the transition state geometry and weakening bonds that must be broken during the reaction [3] [5].

Diagram: Enzyme Catalytic Pathway. Illustrates the cycle of substrate binding, transition state stabilization, and product release, highlighting the induced fit mechanism and enzyme regeneration.

The Molecular Basis of Enzyme Specificity

Specificity is the defining feature that distinguishes enzymes from general chemical catalysts. It ensures that the thousands of reactions in a cell occur in a controlled and coordinated manner [4] [9]. Specificity exists on a continuum and can be categorized based on the enzyme's selectivity:

Table 2: Categories and Examples of Enzyme Specificity

| Specificity Category | Description | Classic Example |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute Specificity | Acts on only one substrate and catalyzes only one reaction. | Urease, which catalyzes only the hydrolysis of urea [4]. |

| Group Specificity | Acts on a specific functional group or bond type within a limited molecular environment. | Trypsin cleaves peptide bonds after basic amino acids (Lys, Arg) [4] [3]. |

| Bond Specificity | Acts on a particular type of chemical bond regardless of the surrounding molecular structure. | α-Amylase cleaves α-1,4-glycosidic bonds in starch [4]. |

| Low Specificity (Promiscuity) | Acts on a broad range of substrates with different structures. | Cytochrome P450 3A4 metabolizes diverse xenobiotics [4]. |

The molecular basis for this specificity lies almost entirely in the structure of the enzyme's active site:

- Complementary Geometry and Chemical Environment: The active site is a three-dimensional cleft or groove composed of amino acid residues from different parts of the polypeptide chain. Its unique shape and chemical properties (e.g., hydrophobic pockets, clusters of charged residues) are complementary to the size, shape, and charge distribution of its intended substrate(s) [5]. The lock-and-key model (rigid complementarity) has been largely supplanted by the induced fit model, where both enzyme and substrate adjust their conformations for optimal binding and catalysis [3] [5].

- Specific Interactions: Binding is mediated by multiple non-covalent interactions: hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic effects. The precise arrangement required for these interactions excludes molecules that are even slightly different. For instance, maltase hydrolyzes α-glucosidic linkages but not β-glucosidic linkages due to stereochemical specificity [4].

- Evolutionary Tuning: An enzyme's specificity reflects evolutionary pressure. Enzymes in central metabolism (e.g., glucokinase) are often highly specific to maintain pathway integrity, while digestive enzymes (e.g., pepsin) or detoxification enzymes (e.g., P450s) have broader specificity to handle diverse nutrients or toxins [4].

Diagram: Continuum of Enzyme Specificity. Shows the range from absolute to promiscuous specificity with corresponding biological examples.

Classical Kinetic Modeling: From Michaelis-Menten to Specificity Constants

The quantitative study of enzyme kinetics provides parameters that link mechanistic biochemistry to observable reaction rates. The Michaelis-Menten equation is the fundamental model for single-substrate reactions [6] [8]:

v = (V_max * [S]) / (K_m + [S])

where v is the initial reaction velocity, V_max is the maximum velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, and K_m is the Michaelis constant.

- Derivation Assumptions: The model assumes rapid equilibrium between enzyme, substrate, and the ES complex, or a steady-state where the concentration of ES remains constant over time [6] [7]. It traditionally applies when the total enzyme concentration

[E]_0is much less than[S]. - Key Parameters:

K_m: Reflects the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate. A low K_m indicates high affinity.V_max: The theoretical maximum rate when all enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate(V_max = k_cat * [E]_0).k_cat: The turnover number, a first-order rate constant describing the catalytic event after substrate binding.

- The Specificity Constant (

k_cat/K_m): This composite constant is the most important kinetic parameter for specificity. It represents the catalytic efficiency for a given substrate. At low substrate concentrations ([S] << K_m), the reaction velocityv = (k_cat/K_m)[E]_0[S], makingk_cat/K_man apparent second-order rate constant for the enzyme's action on a substrate. An enzyme's ability to discriminate between two competing substrates is governed by the ratio of theirk_cat/K_mvalues, not byK_mork_catalone [8].

Generalized Rate Considerations: Recent work emphasizes that the classical Michaelis-Menten formalism is a special case where [E]_0 << [S]. A more generalized rate equation is required when substrate concentration is not in vast excess, as the rate-limiting factor can shift from substrate availability to enzyme availability [10].

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Analysis

Determining kinetic parameters like K_m and V_max requires careful experimental design. The following is a standard protocol for initial rate kinetics based on the Michaelis-Menten model.

Protocol: Determining Michaelis-Menten Parameters via Initial Rate Analysis

Objective: To measure the initial velocity (v₀) of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction at varying substrate concentrations ([S]) and fit the data to determine K_m and V_max.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme stock solution of known concentration.

- Substrate stock solution(s).

- Assay buffer (optimal pH, ionic strength, temperature).

- Cofactors or essential ions if required.

- Stopping reagent or method (e.g., acid, heat, inhibitor).

- Spectrophotometer, fluorometer, or other detection instrument.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a series of reaction tubes (or wells in a microplate) containing a constant, low concentration of enzyme ([E]_0) in a fixed volume of assay buffer. The enzyme concentration must be low enough that substrate depletion is negligible (<5%) during the measurement period.

- Vary Substrate Concentration: Add substrate to each tube to create a range of concentrations, typically spanning from 0.2Km to 5Km (a preliminary experiment may be needed to estimate this range). Include a negative control with no substrate.

- Initiate and Monitor Reaction: Start the reaction by adding enzyme (or substrate if the enzyme is pre-mixed) and immediately begin monitoring the formation of product or disappearance of substrate. Use a method that allows continuous or frequent time-point measurements (e.g., spectrophotometry). Record data only during the initial linear phase of the reaction (typically the first 5-10% of substrate conversion).

- Calculate Initial Velocity (v₀): For each [S], determine v₀ as the slope of the linear plot of product concentration (or absorbance change) versus time.

- Data Analysis: Plot v₀ versus [S]. The data should follow a hyperbolic curve. Linearize the data using a double-reciprocal Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]), an Eadie-Hofstee plot, or a Hanes-Woolf plot. Alternatively, and preferably, fit the raw (v₀, [S]) data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression software to obtain best-fit values for

V_maxandK_m. - Determine k_cat: Calculate

k_cat = V_max / [E]_0, where[E]_0is the total molar concentration of active enzyme sites.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Michaelis-Menten Analysis. Outlines the key steps from reaction setup to parameter calculation.

Advanced Kinetic Models: Incorporating Memory and Time Delays

Classical models assume reactions are memoryless and instantaneous. However, complex enzyme behaviors like allosteric regulation, slow conformational changes, and hysteresis suggest history-dependent dynamics. This has led to the development of fractional calculus models in enzyme kinetics [1].

The Variable-Order Fractional Derivative Model:

A leading-edge approach incorporates a Caputo variable-order fractional derivative with a constant time delay (τ) [1]. The model can be conceptually represented as an extension of the reaction scheme:

E + S ⇌ ES*(t) → E + P

where the formation and breakdown of the ES complex are governed by differential equations containing a fractional derivative of variable order α(t) and a delay term τ.

- Fractional Derivative (

α): The orderαis not an integer (e.g., 1.0 for first-order) but a fraction that can vary with time. It quantifies the "memory" or non-local influence of past states on the current reaction rate. A system with strong memory (e.g., due to a sticky, fractal-like active site) would have a differentαthan one with simple, memoryless kinetics [1]. - Time Delay (

τ): Accounts for finite times required for processes like substrate-induced conformational changes or the formation of successive intermediates in multi-step reactions, which are not instantaneous [1]. - Advantages: This framework can more accurately capture oscillatory dynamics, lag phases, and complex saturation patterns observed in real enzymatic systems, particularly for allosteric enzymes or processive enzyme complexes [1].

Application in Research: These advanced models are crucial for systems biology and drug development, where predicting enzyme behavior in complex, fluctuating cellular environments is essential. They move beyond the steady-state assumption to model how enzymes adapt their activity over time in response to changing conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful enzymatic and kinetic studies rely on high-quality, well-characterized components. The following table details key reagents and their critical functions in experimental research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Must be highly purified to eliminate interfering activities and accurately determine [E]_0. |

Source (recombinant vs. native), specific activity, stability, storage conditions (pH, temperature, glycerol). |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) upon which the enzyme acts. Defines the reaction being studied. | Purity, solubility in assay buffer, stability (non-enzymatic degradation), availability of synthetic analogs for specificity studies. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for enzyme activity and stability. | Correct pKa of buffering agent, ionic composition (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases), absence of inhibitory contaminants. |

| Cofactors / Coenzymes | Small molecules (e.g., NADH, ATP, metal ions) required for catalysis by many enzymes. | Essential for activity; concentration must be saturating and non-limiting in the assay. |

| Stopping Reagent | Halts the enzymatic reaction at a precise time point for discontinuous assays. | Must act instantaneously (e.g., strong acid, denaturant, specific inhibitor) and be compatible with detection method. |

| Detection System | Measures the formation of product or disappearance of substrate (e.g., spectrophotometer, fluorometer, HPLC). | Sensitivity, dynamic range, specificity for the product/substrate, compatibility with assay buffer and volume. |

| Inhibitors / Activators | Compounds used to probe mechanism, regulate activity, or serve as potential drug leads. | Specificity, potency (IC₅₀, Kᵢ), solubility, stability in assay. |

The exquisite ability of enzymes to lower activation energy with high specificity originates from the precise physical and chemical architecture of their active sites. The classical Michaelis-Menten framework has served for a century to quantify this activity, providing the fundamental parameters K_m, V_max, and k_cat/K_m that bridge biochemistry and kinetics.

The future of enzyme kinetic modeling research lies in embracing complexity. Variable-order fractional calculus models that incorporate memory effects and time delays represent a significant advancement for simulating real-world enzymatic behavior in heterogeneous cellular environments [1]. Furthermore, the explosion of genomic data and high-throughput screening technologies is enabling the mining and characterization of vast enzyme families, expanding our repertoire of catalysts for synthetic biology and green chemistry [4].

For drug development professionals, a deep understanding of both the biochemical basis of enzyme action and modern kinetic models is paramount. It allows for the rational design of high-specificity inhibitors, the prediction of metabolic outcomes, and the optimization of biocatalysts—ensuring that this foundational science continues to drive innovation in biotechnology and medicine.

The Michaelis-Menten equation stands as the cornerstone of modern enzymology, providing a quantitative framework to describe the catalytic activity of enzymes [7]. Proposed by Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten in 1913, this model transformed enzyme studies from qualitative observations into a rigorous mathematical science [8]. Within the broader context of principles of enzyme kinetic modeling research, the Michaelis-Menten framework establishes the fundamental relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity, serving as the essential first-order model from which more complex theories evolve [11].

This framework is indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals, as it provides the kinetic parameters—Vmax, Km, and kcat—used to characterize enzyme efficiency, substrate affinity, and catalytic power [12]. These parameters are critical for understanding metabolic pathways, designing enzyme inhibitors, and predicting drug metabolism [13]. This whitepaper deconstructs the classical derivation, explicates its foundational assumptions, and details the interpretation of its key parameters, while also exploring contemporary advancements that address its limitations.

The Michaelis-Menten Derivation: A Step-by-Step Deconstruction

The classic derivation begins with the fundamental reaction scheme for a single-substrate, irreversible enzyme-catalyzed reaction:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P

where E is the free enzyme, S is the substrate, ES is the enzyme-substrate complex, and P is the product [7] [8]. The rate constants are defined as: k₁ for the formation of ES, k₋₁ for its dissociation, and k₂ (often denoted k_cat) for the catalytic conversion to product [7].

The derivation relies on several critical assumptions to make the system mathematically tractable [14]:

- The reaction is measured at initial velocity, where product concentration is negligible, and the reverse reaction (P → S) is ignored.

- The enzyme concentration is much lower than the substrate concentration ([E] << [S]), ensuring that substrate depletion is insignificant.

- The system is in a steady state regarding the ES complex. This Briggs-Haldane assumption states that the rate of ES formation equals its rate of breakdown over the measured period, so d[ES]/dt ≈ 0 [14].

Applying the steady-state assumption forms the core of the derivation:

- The rate of formation of ES is:

k₁[E][S]. - The rate of breakdown of ES is:

(k₋₁ + k₂)[ES]. - Setting formation equal to breakdown gives:

k₁[E][S] = (k₋₁ + k₂)[ES]. - Solving for the concentration of the complex, [ES], requires expressing [E] in terms of total enzyme [E]_total. By conservation of mass:

[E]_total = [E] + [ES]. - Substituting and rearranging yields:

[ES] = ([E]_total * [S]) / ( (k₋₁ + k₂)/k₁ + [S] ).

The expression (k₋₁ + k₂)/k₁ is defined as the Michaelis constant, Km [14]. The observed reaction velocity (v) is proportional to the concentration of productive complex: v = k₂[ES]. Substituting the expression for [ES] gives the Michaelis-Menten equation:

v = (k₂[E]_total [S]) / (K_m + [S])

When the enzyme is fully saturated (all enzyme is present as ES), velocity reaches its maximum, Vmax = k₂[E]_total. The final, canonical form of the equation is:

v = (V_max [S]) / (K_m + [S])

Core Assumptions and Their Implications for Research

The validity of the Michaelis-Menten equation is bounded by its foundational assumptions. Understanding their implications is critical for accurate experimental design and data interpretation in kinetic modeling research.

Table 1: Core Assumptions of the Michaelis-Menten Framework and Their Research Implications

| Assumption | Mathematical Statement | Practical Implication for Research | Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State | d[ES]/dt ≈ 0 |

Valid for the initial period after mixing enzyme and substrate. Requires rapid measurement of initial velocity [14]. | If the pre-steady-state phase is measured, [ES] changes, and the derived equation does not apply. |

| Irreversible Product Formation | k₋₂ [E][P] ≈ 0 |

Experiments must measure initial velocities with negligible product accumulation. High product concentrations can inhibit the reaction [14]. | Significant back-reaction alters net velocity, making estimates of Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ inaccurate. |

| Single Substrate | Reaction scheme: E + S → ES → E + P |

Strictly applies only to uni-substrate reactions. Must be adapted (e.g., with saturating co-substrate) for bisubstrate reactions. | The simple hyperbolic equation fails to model the kinetics of multi-substrate reactions correctly. |

| Enzyme Concentration | [E]_total << [S] |

Must use enzyme concentrations sufficiently low that substrate depletion is minimal during the assay [13]. | If [E] is comparable to Kₘ, the standard equation fails, leading to systematic errors in parameter estimation [13]. |

| Rapid Equilibrium (Simplified) | k₂ << k₋₁ (Optional) |

In the original Michaelis-Menten derivation, this was assumed to simplify Kₘ to a dissociation constant (Kₛ) [7]. The steady-state derivation does not require it. | If not true, Kₘ is a kinetic constant, not a pure measure of substrate binding affinity. |

A major contemporary challenge arises from the violation of the [E] << [S] assumption in physiological and in vitro contexts. Recent research shows that in systems like hepatocytes, enzyme concentrations can be comparable to or even exceed their Kₘ values [13]. This invalidates the standard Michaelis-Menten equation and leads to significant errors in predicting metabolic clearance and drug-drug interactions in physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. Modified rate equations that account for enzyme concentration are now being implemented to restore predictive accuracy in these bottom-up models [13].

Key Parameters: Vmax, Km, and kcat

The Michaelis-Menten equation yields three fundamental kinetic parameters that define an enzyme's functional characteristics.

Vmax (Maximum Velocity)

Vmax represents the theoretical maximum rate of the reaction when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate. It is defined as V_max = k_cat * [E]_total. Experimentally, it is the asymptotic plateau of the velocity vs. [S] curve. While Vmax is dependent on total enzyme concentration, it provides crucial information about an enzyme's total catalytic capacity in a given system [12]. Recent advancements in artificial intelligence aim to predict Vmax from enzyme structure, using neural networks trained on amino acid sequences and molecular fingerprints of reactions to accelerate in silico modeling [15].

Km (Michaelis Constant)

The Km is the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax. It is defined as K_m = (k₋₁ + k_cat)/k₁. While often informally described as a measure of substrate affinity, this is strictly true only if k_cat << k₋₁ (i.e., the rapid equilibrium condition). A lower Km indicates that the enzyme reaches half its maximum velocity at a lower substrate concentration, often reflecting tighter substrate binding or more efficient conversion [12] [16]. It is a central parameter for comparing an enzyme's activity against different substrates.

kcat (Turnover Number) The turnover number, kcat, is the first-order rate constant for the catalytic step (ES → E + P). It represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time. It is a direct measure of an enzyme's intrinsic catalytic proficiency once the substrate is bound [8].

Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km)

The ratio k_cat/K_m is a second-order rate constant that describes the enzyme's overall effectiveness at low substrate concentrations ([S] << Km). It incorporates both binding affinity (reflected in Km) and catalytic rate (k_cat). An enzyme with a high k_cat/K_m is efficient at selecting and transforming its substrate from a dilute solution. This parameter is critical for comparing the specificity of an enzyme for alternative substrates [8].

Table 2: Representative Kinetic Parameters for Various Enzymes [8]

| Enzyme | K_m (M) | k_cat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Catalytic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 | Moderate affinity, slow turnover. |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ | Higher affinity and efficiency than chymotrypsin. |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ | Very fast turnover, high efficiency. |

| Carbonic Anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ | Extremely high turnover number, near diffusion-controlled efficiency. |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ | Very high substrate affinity and exceptional catalytic efficiency. |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Kinetic Parameters

The standard method for determining Vmax and Km involves measuring initial velocities (v) across a range of substrate concentrations ([S]) and fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

1. Assay Design:

- Maintain constant, saturating levels of all other reaction components (cofactors, buffers at optimal pH, temperature).

- Use enzyme concentrations sufficiently low ([E] << K_m) to meet model assumptions and prevent significant substrate depletion (<5%) during the measurement period [14].

- Use a sensitive, continuous or stopped method to measure product formation or substrate disappearance over time.

2. Data Collection:

- Measure initial velocity (v) for at least 6-8 substrate concentrations, ideally spanning from ~0.2Km to 5Km.

- Perform replicates to ensure data reliability.

3. Data Analysis:

- Nonlinear Regression (Gold Standard): Directly fit the v vs. [S] data to the hyperbolic equation

v = (V_max[S])/(K_m + [S])using software like GraphPad Prism [16]. This method provides the most accurate estimates of Vmax and Km with confidence intervals. - Linear Transformations (Historical/Diagnostic): The Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) linearizes the data but distorts error distribution and is statistically inferior for parameter estimation. It should be used for data visualization only, not for calculation [16]. Other plots include the Eadie-Hofstee (v vs. v/[S]) and Hanes-Woolf ([S]/v vs. [S]).

4. Determining k_cat:

- Once Vmax is obtained, calculate kcat using the relationship:

k_cat = V_max / [E]_total. - This requires an accurate measure of the molar concentration of active enzyme sites in the assay, often determined by active site titration or quantitative amino acid analysis.

Modern Frontiers: Extending the Classical Framework

The classical model is a one-state, memoryless (Markovian) representation. Modern single-molecule enzymology reveals complex kinetic behaviors that necessitate framework extensions.

High-Order Michaelis-Menten Equations A significant 2025 advancement is the derivation of high-order Michaelis-Menten equations that generalize the classic model to moments of any order of the turnover time distribution [11]. While the mean turnover time (first moment) always shows the classic linear dependence on 1/[S], higher moments (variance, skewness) exhibit complex, non-universal behaviors. The new theoretical framework identifies specific combinations of these higher moments that regain universal linear relationships with 1/[S] [11].

Table 3: Information Accessible from Classical vs. High-Order Michaelis-Menten Analysis [11]

| Analysis Type | Accessible Parameters | Experimental Requirement | Biological Insight Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical (Bulk/Mean) | Vmax, Km, kcat/Km | Standard steady-state kinetics. | Macroscopic catalytic efficiency and affinity. |

| Single-Molecule (1st Moment) | Same as classical, but from single enzymes. | Tracking turnovers of individual enzyme molecules. | Confirms homogeneity/heterogeneity of activity. |

| High-Order Moment Analysis | Mean binding/unbinding times, lifetime of ES complex, probability of catalysis vs. unbinding. | Distribution of single-molecule turnover times (requires ~thousands of events) [11]. | Reveals hidden kinetic states, dynamic disorder, and non-Markovian dynamics in catalysis. |

This approach allows researchers to infer previously hidden parameters—such as the mean lifetime of the enzyme-substrate complex, the substrate binding rate, and the probability that a binding event leads to catalysis—from the statistical distribution of single-molecule turnover times, even when internal states are not directly observable [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Michaelis-Menten Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Must have known concentration and, ideally, specific activity. | Purity and stability are paramount. Aliquot and store to prevent freeze-thaw degradation. Determine active site concentration for k_cat. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. | Solubility in assay buffer is critical. Prepare a stock solution at the highest concentration needed. Verify it is stable under assay conditions. |

| Detection System | Measures product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., spectrophotometer, fluorimeter, HPLC). | Must be specific, sensitive, and have a linear range covering all expected velocities. Coupled assays require excess coupling enzymes. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains optimal pH, ionic strength, and provides necessary cofactors (Mg²⁺, ATP, etc.). | Buffer should not interact with reactants. Include reducing agents (e.g., DTT) for cysteine-dependent enzymes if needed. Control temperature precisely. |

| Positive Control Inhibitor/Activator | A known modulator of enzyme activity. | Used to validate the assay is functioning correctly and responding as expected to perturbations. |

The Michaelis-Menten framework remains an indispensable and active foundation in enzyme kinetic modeling research. Its straightforward derivation and clearly defined parameters (Vmax, Km, k_cat) provide the essential language for quantifying and comparing enzyme function. For drug development professionals, these parameters are critical for predicting in vivo metabolism, assessing drug-drug interaction risks, and designing targeted inhibitors [13].

However, modern research, powered by single-molecule techniques and sophisticated modeling, is rigorously testing and expanding this century-old framework. Contemporary studies address its limitations—such as the invalidity of the low-enzyme assumption in physiological systems [13]—and probe dynamics hidden within the classical three-state model [11]. The development of high-order equations and AI-driven parameter prediction represents the evolution of the framework from a purely empirical tool to a gateway for discovering deeper mechanistic truths about enzyme catalysis [11] [15]. Therefore, a thorough deconstruction of the Michaelis-Menten model is not merely a historical exercise but a vital prerequisite for engaging with the current frontiers of enzymology and quantitative bioscience.

The cornerstone of quantitative enzymology, the Michaelis-Menten equation (v = Vmax * [S] / (Km + [S])), describes a hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration [S] and initial reaction velocity v [17]. While fundamental, the hyperbolic form presents significant challenges for the accurate graphical determination of its key parameters—the maximum velocity (Vmax) and the Michaelis constant (Km). Direct non-linear fitting is now the preferred method, but graphical linear transformations retain critical importance for visualizing data, diagnosing inhibition patterns, and teaching core concepts [18].

Within the broader thesis of enzyme kinetic modeling research, these transformations are not mere mathematical curiosities but essential tools for hypothesis testing. They provide a framework for distinguishing between mechanistic models of enzyme action, particularly in the critical evaluation of inhibitors, which form the basis for a vast array of therapeutic drugs [19]. This guide delves into the two predominant linear transformations—the Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot and the Eadie-Hofstee plot—contrasting their derivations, applications, and inherent statistical limitations to empower researchers in making informed analytical choices.

Foundational Theory: From Hyperbola to Line

The Michaelis-Menten model derives from the canonical enzyme reaction scheme: E + S ⇌ ES → E + P. Under steady-state assumptions, this yields the hyperbolic velocity equation [17]. The primary kinetic parameters are:

Vmax: The maximum theoretical reaction rate when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate.Km: The substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half ofVmax. It is an inverse measure of the enzyme's affinity for the substrate—a lowerKmindicates higher affinity [20].

The Lineweaver-Burk (Double-Reciprocal) Transformation

The Lineweaver-Burk plot is generated by taking the reciprocal of both sides of the Michaelis-Menten equation [18]:

1/v = (Km/Vmax) * (1/[S]) + 1/Vmax

This equation is of the form y = mx + b, where:

- y-axis:

1/v - x-axis:

1/[S] - Slope (m):

Km / Vmax - y-intercept (b):

1/Vmax - x-intercept:

-1/Km

The Eadie-Hofstee Transformation

The Eadie-Hofstee plot arises from a different algebraic rearrangement of the Michaelis-Menten equation [21]:

v = Vmax - Km * (v/[S])

In this form:

- y-axis:

v - x-axis:

v/[S] - Slope (m):

-Km - y-intercept (b):

Vmax - x-intercept:

Vmax / Km

Table 1: Comparison of Linear Transformation Methods

| Feature | Michaelis-Menten Plot | Lineweaver-Burk Plot | Eadie-Hofstee Plot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinate (y-axis) | v |

1/v |

v |

| Abscissa (x-axis) | [S] |

1/[S] |

v/[S] |

| Form | Hyperbola | Straight Line | Straight Line |

| Slope | – | Km / Vmax |

-Km |

| y-intercept | – | 1 / Vmax |

Vmax |

| x-intercept | – | -1 / Km |

Vmax / Km |

| Primary Visual Readout | Vmax as plateau, Km as [S] at Vmax/2 |

Vmax from y-intercept, Km from x-intercept |

Vmax from y-intercept, Km from slope |

Graphical Interpretation and Diagnosis of Inhibition

A paramount application of linearized plots is the rapid diagnosis and classification of enzyme inhibition, crucial in drug discovery [19]. Each inhibitor type produces a characteristic pattern.

Competitive Inhibition

The inhibitor competes with the substrate for binding to the active site. It increases the apparent Km without affecting Vmax [20] [22].

- Lineweaver-Burk: Lines intersect on the y-axis (identical

1/Vmax). The slope increases with inhibitor concentration [18]. - Eadie-Hofstee: Lines intersect on the y-axis (identical

Vmax). Slopes become more negative (apparentKmincreases).

Pure Non-Competitive Inhibition

The inhibitor binds to a site distinct from the active site with equal affinity for the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex. It decreases Vmax without affecting Km [18].

- Lineweaver-Burk: Lines intersect on the x-axis (identical

-1/Km). The y-intercept increases [18]. - Eadie-Hofstee: Lines are parallel (identical slope,

-Km). The y-intercept decreases.

Uncompetitive Inhibition

The inhibitor binds only to the enzyme-substrate complex. It decreases both Vmax and the apparent Km [18].

- Lineweaver-Burk: Parallel lines. Both intercepts change (

1/Vmaxincreases,-1/Kmbecomes less negative) [22]. - Eadie-Hofstee: Lines intersect on the x-axis (identical

Vmax/Kmratio). Both slope and y-intercept change.

Diagram: Diagnostic Patterns of Enzyme Inhibition on Linear Plots

Critical Analysis of Error Propagation and Modern Best Practices

Despite their utility for visualization, linear transformations have significant statistical drawbacks, as both variables (v and [S]) are subject to experimental error.

Error Structure and Limitations

- Lineweaver-Burk Plot: It is the most error-prone. Taking the reciprocal of

vdisproportionately amplifies errors at low substrate concentrations (wherevis small), giving undue weight to the least accurate data points and distorting the regression line [18]. This can lead to poor estimates ofKmandVmax. - Eadie-Hofstee Plot: It is less distorting than the Lineweaver-Burk plot because it avoids double reciprocals. However, it suffers from having the dependent variable

von both axes (vvs.v/[S]), which violates an assumption of standard linear regression and complicates error analysis [21].

Table 2: Error Characteristics and Modern Utility of Linear Plots

| Plot Type | Primary Statistical Shortcoming | Best Use Case | Contemporary Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk | Severe distortion of error; over-weights low-[S], low-v data [18]. |

Qualitative diagnosis of inhibition type. Educational tool. | Avoid for parameter calculation. Use weighted non-linear regression of raw (v, [S]) data for accurate Km & Vmax [18]. |

| Eadie-Hofstee | Dependent variable (v) on both axes violates regression assumptions [21]. Spans full theoretical range of v. |

Visual identification of data heterogeneity (e.g., multiple enzymes, cooperativity) as points scatter across the full v range [21]. |

Can be a useful diagnostic plot to detect deviations from simple Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Final parameters should come from non-linear fit. |

| Non-Linear Fit | Requires appropriate weighting model and computational tools. | Gold standard for accurate, unbiased parameter estimation and confidence intervals. | Mandatory for publication-quality kinetics. Use software (e.g., Prism, GraphPad, KinetiScope) to fit v = Vmax*[S]/(Km+[S]) directly. |

Protocol for Robust Kinetic Analysis

- Experimental Design: Measure initial velocities across a substrate concentration range that brackets the suspected

Km(e.g.,0.2Kmto5Km). Use at least 8-10 data points with replicates [19]. - Data Visualization:

- Plot raw data as a Michaelis-Menten hyperbola.

- Create an Eadie-Hofstee plot as a diagnostic for deviations from linearity (indicative of multiple phases, cooperativity, or poor data).

- Use a Lineweaver-Burk plot only to illustrate inhibition patterns once simple kinetics are confirmed.

- Parameter Estimation: Perform non-linear regression on the raw (

v,[S]) data using an appropriate weighting function (often1/v²or1/Y²). ReportKmandVmaxwith 95% confidence intervals. - Inhibition Studies: Collect velocity data at multiple substrate concentrations across a range of inhibitor concentrations. Fit data globally to competitive, non-competitive, or uncompetitive models using non-linear regression to determine the inhibition constant (

Ki).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetic Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. May be wild-type or recombinant. | Purity is critical. Activity should be validated. Store in stable, aliquoted batches at -80°C to minimize freeze-thaw degradation [23]. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. | High purity. Prepare fresh solutions or stable aliquots. The concentration range must be verified (e.g., via spectrophotometry) [19]. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength, and cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases). | Mimics physiological conditions. Must not interfere with detection method. Include stabilizing agents (e.g., BSA, DTT) if needed [19]. |

| Detection System | Quantifies product formation or substrate depletion. | Spectrophotometric: Uses chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates. Coupled Assay: Links reaction to NADH oxidation/reduction. Radioactive/MS-based: For direct, label-free measurement [19]. Must have a linear signal range. |

| Inhibitor Compounds | Molecules tested for modulation of enzyme activity. | Solubilize in DMSO or buffer. Final solvent concentration must be constant (<1% v/v) and non-inhibitory. Use a dose-response series [19]. |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Validates assay performance. | Positive: A known potent inhibitor. Negative: No-enzyme control, vehicle-only control. Essential for calculating percent inhibition and IC₅₀ [19]. |

Advanced Context: Integration with Modern Drug Discovery and PBPK Modeling

The principles underlying these graphical methods extend into cutting-edge research. Mechanistic enzymology, which relies on precise determination of kinetic parameters, is vital for characterizing drug targets and optimizing small-molecule inhibitors [19]. Understanding Km and Ki informs structure-activity relationships (SAR) and the design of compounds with desired potency and selectivity.

Furthermore, traditional Michaelis-Menten kinetics, which assumes enzyme concentration [E] is negligible compared to Km, can falter in complex physiological systems. Recent advancements in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling highlight this limitation. A 2025 study demonstrated that a modified rate equation, which accounts for scenarios where [E] is comparable to Km, significantly improves the prediction of in vivo drug clearance and drug-drug interactions over the standard Michaelis-Menten equation used in bottom-up PBPK modeling [24]. This underscores the ongoing evolution of kinetic modeling from in vitro graphical analysis to sophisticated in vivo prediction, anchored by the fundamental parameters these transformations were designed to reveal.

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Modern Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

Lineweaver-Burk and Eadie-Hofstee plots remain indispensable components of the enzymologist's conceptual toolkit. Their power lies not in modern parameter estimation—a task best relegated to weighted non-linear regression—but in their unmatched ability to provide intuitive, visual insights into enzyme mechanism and inhibition. Within the rigorous framework of contemporary enzyme kinetic modeling research, they serve as critical diagnostic and pedagogical instruments. Their enduring relevance is evidenced by their foundational role in supporting advanced applications, from the mechanistic-driven discovery of next-generation therapeutics [19] to the refinement of complex physiological models that predict drug behavior in vivo [24]. Mastery of both the interpretation and the limitations of these graphical transformations is therefore essential for any researcher engaged in the quantitative analysis of enzyme action.

A fundamental objective in pharmacology and systems biology is the accurate prediction of in vivo physiological and therapeutic outcomes from in vitro experimental data. This translation is predicated on mathematical models of enzyme kinetics, which serve as the mechanistic core for describing drug metabolism, signaling pathways, and cellular responses [25]. However, these models are built upon simplifying assumptions that are often necessary for in vitro tractability but which may fracture under the complexity of living systems [26]. The quasi-steady-state assumption, low enzyme concentration postulates, and the treatment of systems as thermodynamically closed are cornerstones of classical models like Michaelis-Menten [25]. Their violation in vivo can lead to significant predictive errors in drug efficacy and toxicity [27] [28]. This guide examines these critical assumptions within the broader thesis of enzyme kinetic modeling research, detailing their physiological implications, and presents modern frameworks—including advanced kinetic models, physiologically-based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) integration, and novel in vitro systems—designed to bridge the translational gap for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Kinetic Models and Their Foundational Assumptions

The choice of enzyme kinetic model dictates the fidelity of biochemical network simulations. This section deconstructs the assumptions of prevalent models.

Classical Michaelis-Menten (MM) Kinetics operates under two primary constraints: the quasi-steady-state assumption (QSSA), where the enzyme-substrate complex concentration is assumed constant, and the "low enzyme" assumption, where total enzyme concentration is significantly less than the substrate concentration ([E]T << [S]T) [25] [29]. While useful for simple in vitro systems, the low enzyme condition is frequently invalid in cellular environments where enzymes and substrates can exist at comparable concentrations. Applying MM kinetics in such contexts can introduce substantial errors in predicting reaction fluxes and metabolite levels [25].

The Total Quasi-Steady State Assumption (tQSSA) model was developed to eliminate the restrictive low-enzyme assumption, extending accuracy to a wider range of in vivo conditions. However, this comes at the cost of increased mathematical complexity, requiring more sophisticated algebraic solutions for each network topology [25].

The Differential QSSA (dQSSA), proposed as a generalized model, aims to balance accuracy and simplicity. It expresses differential equations as a linear algebraic system, eliminating reactant stationary assumptions without increasing parameter dimensionality. This model has demonstrated improved performance in simulating reversible reactions and phenomena like coenzyme inhibition in lactate dehydrogenase, which the MM model fails to capture [25].

Fractional Calculus Models represent a paradigm shift by incorporating memory and hereditary effects into kinetic equations. Unlike integer-order derivatives, fractional-order derivatives account for the influence of past system states. Variable-order fractional derivatives further allow this "memory strength" to evolve over time, capturing complex in vivo dynamics such as enzyme adaptation, slow conformational changes, and delays from intermediate complex formation [1]. These models are particularly suited for systems with fractal-like geometries or non-instantaneous regulatory feedback [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Enzyme Kinetic Modeling Frameworks

| Model | Key Assumptions | Mathematical Complexity | Primary In Vivo Limitation | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis-Menten | Quasi-steady state; [E]T << [S]T; Irreversible reaction [25] [29] | Low (explicit equation) | Invalid at high enzyme concentration; misses reversibility [25] | Simple in vitro assays with excess substrate. |

| Total QSSA (tQSSA) | Quasi-steady state only [25] | High (requires network-specific solution) | Complex application in large networks [25] | Single or few enzyme systems where [E]T ~ [S]T. |

| Differential QSSA (dQSSA) | Quasi-steady state; linear algebraic form [25] | Moderate (linear system) | Does not account for all physical intermediate states [25] | Reversible reactions and complex enzyme-mediated networks. |

| Variable-Order Fractional | History-dependence; power-law memory [1] | Very High (numerical solution required) | Parameter estimation and computational demand [1] | Systems with documented memory effects, delays, or oscillatory dynamics. |

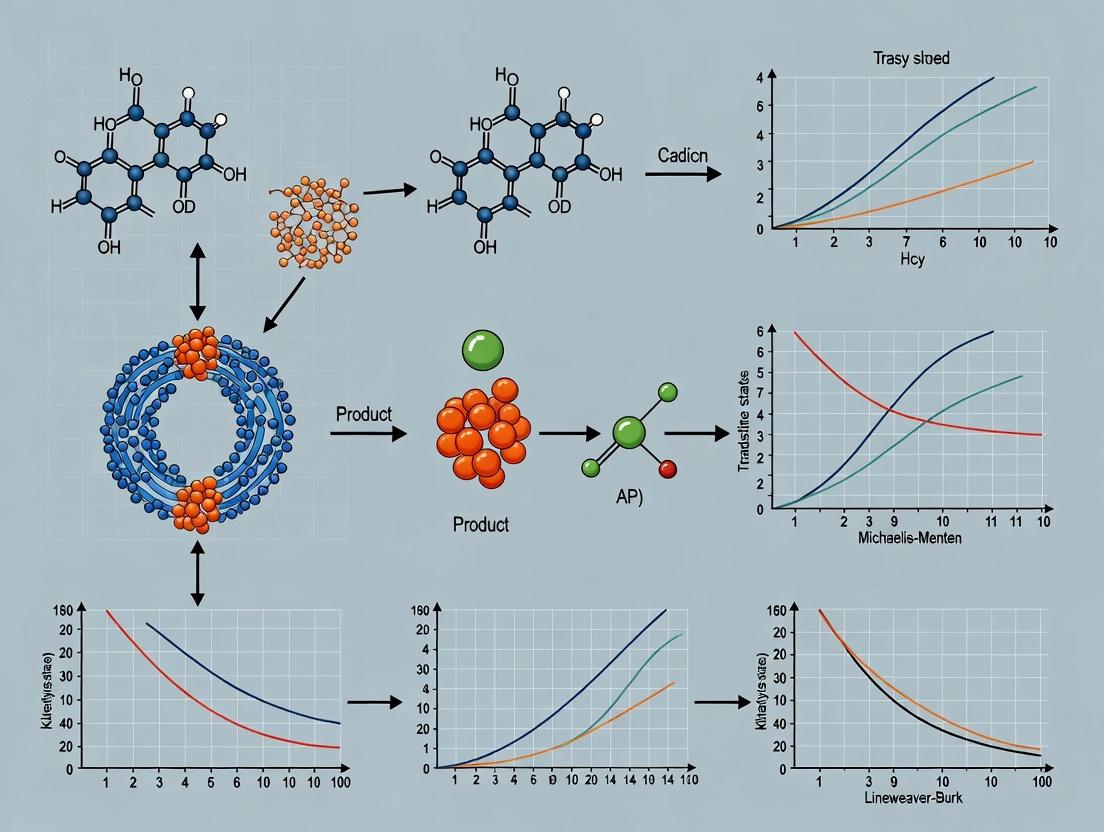

Figure 1: Logical map of core in vitro modeling assumptions, their in vivo violations, and resulting physiological implications [25] [1] [26].

Integrating Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics (PK/PD)

Predicting in vivo outcomes requires coupling enzyme kinetic-driven pharmacodynamics (PD) with physiological pharmacokinetics (PK). A seminal study on the LSD1 inhibitor ORY-1001 demonstrated a successful PK/PD modeling framework trained predominantly on in vitro data [27].

Model Structure and Workflow:

- In Vitro PD Model: An ordinary differential equation (ODE) model integrated four key measurements: target engagement (% bound LSD1), biomarker dynamics (GRP levels), drug-treated cell viability, and drug-free cell growth. The model was trained using high-dimensional data across multiple doses, time points, and dosing regimens (pulsed and continuous) [27].

- In Vivo PK Model: A two-compartment model with first-order absorption was fitted to mouse plasma concentration-time data. The critical link was the unbound plasma drug concentration, assumed to be in equilibrium with intracellular free drug concentration driving target engagement [27].

- Scaling to In Vivo: The in vitro PD model was directly connected to the in vivo PK model via the unbound drug concentration. Remarkably, only one parameter required adjustment: the intrinsic cell growth rate constant (k_p), which was scaled to reflect the slower growth of tumor cells in vivo and the change in units from cell number to tumor volume [27].

Table 2: Key Experimental Data for PK/PD Model Training [27]

| Measurement Type | Context | Time Points | Doses | Dosing Regimen | Purpose in Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Engagement | In vitro | 4 | 3 | Pulsed | Define drug-binding kinetics & occupancy. |

| Biomarker Levels (GRP) | In vitro | 3 | 3 | Both | Link target engagement to downstream effect. |

| Drug-Free Cell Growth | In vitro | 6 | No drug | No drug | Establish baseline growth parameter (k_p). |

| Drug-Treated Cell Viability | In vitro | No | 9 | Both | Quantify growth inhibition dose-response. |

| Drug-Free Tumor Growth | In vivo | 9 | No drug | No drug | Re-calibrate k_p for in vivo context. |

| Plasma Drug PK | In vivo | 3-7 | 3 | Single dose | Define systemic exposure (PK model input). |

Advanced Computational Extrapolation Frameworks

Beyond direct PK/PD linking, more comprehensive computational frameworks are essential for quantitative in vitro to in vivo extrapolation (QIVIVE).

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling: PBPK models incorporate mechanistic, physiological knowledge to predict drug disposition. A 2025 study on predicting brain extracellular fluid (ECF) PK for P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrates highlights both the promise and challenges of a bottom-up approach using in vitro data [28].

- Methodology: Apparent permeability (Papp) and corrected efflux ratios from cell lines (Caco-2, LLC-PK1-MDR1, MDCKII-MDR1) were used to calculate P-gp efflux clearance (CLpgp). This was scaled using a relative expression factor (REF) based on differences in P-gp expression between the in vitro system and the in vivo rat blood-brain barrier [28].

- Outcome & Challenge: The model predicted brain ECF PK within a two-fold error for 3 out of 4 compounds after continuous infusion. However, prediction success was highly variable and dependent on the source of the in vitro data, underscoring the significant impact of inter-laboratory variability on model robustness [28].

Biomimetic In Vitro Systems and IVIVE: Novel in vitro systems strive to better replicate the in vivo microenvironment. A 2025 study integrated a biomimetic system with a mesh insert to simultaneously model drug diffusion and hepatic metabolism in HepaRG cells [30].

- Protocol: Drug diffusion across different mesh pore sizes was quantified and modeled using a Weibull distribution equation. This diffusion model was then coupled with metabolic conversion data (e.g., diclofenac to 4'-hydroxydiclofenac) to perform IVIVE for hepatic clearance prediction [30].

- Advantage: This integrated approach allows for the simultaneous assessment of physical transport barriers and metabolic capacity, providing a more holistic set of parameters for PBPK model input and improving IVIVE accuracy [30].

Figure 2: Workflows of advanced computational frameworks for in vitro to in vivo extrapolation.

Experimental Protocols for Translation-Ready Data

Generating data suitable for QIVIVE requires carefully designed experiments that probe dynamics and mechanisms.

Protocol for Comprehensive In Vitro PK/PD Training Data (as implemented for LSD1 inhibitor) [27]:

- Cell Culture: Maintain target cancer cell line (e.g., NCI-H510A for SCLC) under standard conditions.

- Target Engagement Assay:

- Treat cells with a range of drug concentrations (e.g., low, medium, high) in pulsed regimens.

- At multiple time points post-treatment (e.g., 2, 6, 24, 48h), lysate cells.

- Quantify bound vs. total target enzyme using a method like immunocapture or probe-based spectroscopy to calculate % target engagement.

- Biomarker Response Assay:

- Treat cells similarly. Measure mRNA or protein levels of a relevant pharmacodynamic biomarker (e.g., GRP) at selected time points (e.g., 24, 48, 72h) via qPCR or ELISA.

- Cell Growth/Viability Assay:

- Drug-free growth: Seed cells and count them frequently over 6-9 days to establish baseline growth kinetics.

- Drug-treated viability: Expose cells to a wide dose range under both continuous and pulsed regimens. Measure cell viability (e.g., via ATP luminescence) at a standardized endpoint (e.g., 96h or 144h) to generate dose-response curves.

- Data Integration: All data (concentration-time-responses) are formatted for simultaneous fitting in a ODE-based modeling software (e.g., Monolix, NONMEM, R/Matlab with optimization packages) to estimate parameters for target binding, biomarker modulation, and cell kill.

Protocol for Generating PBPK Input from Transwell Assays [28]:

- Cell Monolayer Preparation: Culture transporter-expressing cells (e.g., MDCKII-MDR1) on transwell inserts until a tight, confluent monolayer forms (validate with transepithelial electrical resistance).

- Bidirectional Permeability Assay:

- Add the test compound to either the apical (A) or basolateral (B) donor compartment. Use a P-gp inhibitor control (e.g., zosuquidar) in parallel to define specific transport.

- Sample from the receiver compartment at multiple time points over ~2 hours.

- Quantify compound concentration in samples using LC-MS/MS.

- Data Calculation:

- Calculate apparent permeability:

P_app = (dQ/dt) / (A * C_0), where dQ/dt is the flux rate, A is the filter area, and C_0 is the initial donor concentration. - Calculate efflux ratio:

ER = P_app(B->A) / P_app(A->B). - Calculate corrected efflux ratio:

ER_c = ER (with inhibitor) / ER (without inhibitor).

- Calculate apparent permeability:

- In Vitro-to-In Vivo Scaling:

- Calculate in vitro active efflux clearance:

CL_invitro = (P_app(B->A) - P_app(A->B)) * A. - Apply a relative expression factor (REF):

CL_invivo = CL_invitro * (Expression_P-gp_invivo / Expression_P-gp_invitro).

- Calculate in vitro active efflux clearance:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Translation-Focused Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Critical Consideration for Translation |

|---|---|---|

| ORY-1001 (or analogous tool compound) [27] | Potent, selective, covalent inhibitor of LSD1/KDM1A. Used to establish a proof-of-concept PK/PD modeling framework. | Covalent mechanism simplifies target engagement modeling (quasi-irreversible binding) [27]. |

| Engineered Cell Lines (MDCKII-MDR1, LLC-PK1-MDR1) [28] | Stably overexpress human P-glycoprotein (MDR1) for transwell transport assays. | Expression level must be quantified to calculate Relative Expression Factors (REF) for scaling [28]. |

| Caco-2 Cells [28] | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line that endogenously expresses various transporters, including P-gp. | Exhibits significant inter-laboratory phenotypic variability, impacting reproducibility of in vitro parameters [28]. |

| HepaRG Cells [30] | Bipotent human hepatic progenitor cell line that differentiates into hepatocyte-like and biliary-like cells. | Provides a stable and metabolically competent human-relevant liver model for IVIVE of clearance [30]. |

| Selective P-gp Inhibitors (e.g., Zosuquidar, Tariquidar) | Used in control experiments during transport assays to delineate P-gp-specific efflux from passive diffusion. | Essential for calculating the corrected efflux ratio (ER_c), a more specific metric for transporter activity [28]. |

| Biomimetic Mesh Inserts [30] | Inserts with defined pore sizes placed in well plates to create a diffusion barrier. | Allows for the simultaneous experimental study of diffusion and metabolism, key for modeling absorption and distribution [30]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates | Isotopically labeled versions of drug molecules or endogenous metabolites. | Enable highly sensitive and specific tracking of metabolic conversion rates in complex systems via LC-MS/MS, crucial for accurate CL_int estimation [30]. |

The translation from in vitro data to in vivo prediction remains a central challenge in quantitative systems pharmacology. Success hinges on recognizing and addressing the physiological implications of core enzyme kinetic assumptions. As demonstrated, advancements are being made on multiple fronts: through the development of more robust kinetic models (e.g., dQSSA, fractional calculus), the sophisticated integration of PK/PD models trained on high-quality in vitro dynamic data, and the use of bottom-up PBPK models informed by mechanistic in vitro transport and metabolism studies [25] [27] [1].

The future lies in the systematic integration of these approaches. This includes standardizing in vitro systems to reduce data variability, further developing biomimetic models that capture tissue-level complexity, and employing multi-scale modeling that seamlessly connects molecular-scale enzyme kinetics to organism-level physiology [30] [26]. Embracing the "3R" principle (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement of animal testing) provides a strong ethical and economic impetus for this work [27] [30]. By rigorously validating these integrated frameworks against clinical data, the field can move towards a future where in vitro models, governed by principled enzyme kinetics, become truly predictive pillars of drug discovery and development.

From Theory to Practice: Building and Applying Robust Kinetic Models

Within the broader thesis on the principles of enzyme kinetic modeling research, the translation of raw experimental data into robust, predictive mathematical models represents a critical juncture. This process, encompassing curve fitting and rigorous error analysis, is fundamental to deriving biologically meaningful parameters such as Vmax and Km, which describe catalytic efficiency and substrate affinity [31]. In biological systems, enzymes rarely operate under the idealized, isolated conditions assumed by basic models. Instead, they function within complex, open thermodynamic networks where factors like coenzyme concentration, allosteric regulation, and multi-substrate reactions prevail [25] [32]. Consequently, the researcher’s task extends beyond simple parameter estimation to selecting mechanistically appropriate models that balance parameter dimensionality with predictive accuracy [25]. This guide provides a rigorous, step-by-step framework for this essential process, ensuring that models derived from experimental data are both statistically sound and biologically interpretable, thereby advancing the core objectives of mechanistic enzyme kinetic research.

Theoretical Foundations: From Enzyme Mechanisms to Fittable Models

Core Kinetic Models and Their Applications

The choice of a kinetic model is a hypothesis about the underlying enzyme mechanism. Selecting an appropriate model is the first and most critical step in curve fitting.

Table 1: Common Enzyme Kinetic Models and Their Applications

| Model Type | Mathematical Form | Key Parameters | Primary Application & Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis-Menten (Irreversible) [31] | ( v = \frac{V{max}[S]}{Km + [S]} ) | Vmax, Km | Single-substrate, irreversible reaction under reactant stationary and low enzyme concentration assumptions. |

| Reversible Mass Action [25] | System of ODEs (e.g., ( \dot{[ES]} = k{fa}[S][E] - (k{fd} + k_{fc})[ES] )) | kfa, kfd, kfc, kra, krd, krc | Fundamental mechanistic description; requires six parameters for reversible conversion of S to P. |

| Total Quasi-Steady-State (tQSSA) [25] | Complex implicit algebraic form | Km, Vmax, ET | Relaxes low-enzyme assumption but increases mathematical complexity for network modeling. |

| Differential QSSA (dQSSA) [25] | Linear algebraic form derived from ODEs | Reduced parameter set vs. mass action | Generalised model for complex networks; minimizes assumptions without excessive parameter dimensionality. |

| Allosteric (Hill Equation) [32] | ( v = \frac{V{max}[S]^n}{K{0.5}^n + [S]^n} ) | Vmax, K0.5, n (Hill coeff.) | Models cooperativity in enzymes with multiple substrate-binding sites. |

The Curve Fitting Imperative

Curve fitting is the process of constructing a mathematical function that has the best fit to a series of experimental data points [33]. In enzyme kinetics, this typically involves adjusting the parameters (θ) of a chosen model (f) to minimize the difference between predicted velocities (vpred) and observed velocities (vobs). The most common method is nonlinear least squares regression, which aims to find the parameter set that minimizes the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS): RSS = Σ(vobs - vpred)² [34]. For linearizable models like Michaelis-Menten (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plot), linear regression can be used, but nonlinear fitting of the original equation is preferred as it avoids statistical distortion of error structures [35].

Methodological Framework: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Phase 1: Experimental Design and Data Acquisition

A robust fitting process begins with high-quality data.

- Experimental Replicates: Perform initial velocity measurements in triplicate at minimum to estimate intrinsic variability at each substrate concentration [36].

- Substrate Concentration Range: Design experiments so that [S] values bracket the expected Km (typically 0.2Km to 5Km) to well-definethe hyperbolic curve [31].

- Control for Systematic Error: Use calibrated instrumentation and standardized buffers to minimize systematic errors (bias). Record environmental conditions (temperature, pH) as they are critical for reproducibility [37] [38].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Kinetic Experiments |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest; stability and storage conditions must be optimized to maintain activity. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) converted by the enzyme; purity is critical to avoid alternative reactions. |

| Buffer System | Maintains constant pH, which is crucial as enzyme activity is highly pH-dependent [32]. |

| Spectrophotometer / Fluorimeter | For continuous assay of product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., NADH absorbance at 340 nm). |

| Stopped-Flow Apparatus | For measuring very fast reaction rates on the millisecond timescale. |

| Microplate Reader | Enables high-throughput kinetic screening of multiple conditions or inhibitors. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python, Prism) | Essential for performing nonlinear regression, error analysis, and residual diagnostics [34]. |

Phase 2: The Curve Fitting Workflow

This core protocol adapts the nonlinear least squares approach for enzyme kinetic data [34].

Diagram: Core Curve Fitting Workflow for Enzyme Kinetics

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Model Selection: Based on mechanistic knowledge (e.g., single vs. multi-substrate, cooperativity), choose the model from Table 1.

- Define Function: Implement the model equation in your software (e.g.,

MM <- function(S, Vmax, Km) {Vmax * S / (Km + S)}in R). - Initial Estimates: Graph the data. Estimate Vmax from the plateau and Km as the [S] at half Vmax. For Michaelis-Menten, these visual guesses are often sufficient [34].

- Perform Fitting: Use a nonlinear fitting algorithm (e.g.,

nlsin R,lsqcurvefitin MATLAB). The algorithm iteratively adjusts θ to minimize RSS.

- Extract Output: Obtain best-fit parameters (θ̂) and their standard errors from the covariance matrix. The standard error quantifies the uncertainty in each parameter estimate.

- Generate Curve: Calculate the predicted model curve using θ̂ across a finely spaced range of [S] for a smooth plot.

- Visual Validation: Superimpose the best-fit curve on the original data for an initial visual assessment of goodness-of-fit.

Phase 3: Error Analysis and Model Validation

Parameter estimates are meaningless without quantification of their uncertainty.

A. Types of Experimental Error:

- Random Error: Unpredictable fluctuations causing data scatter (imprecision). Quantified by the standard deviation of replicates [38] [36].

- Systematic Error: Consistent bias displacing results from the "true" value (inaccuracy). Harder to detect; may arise from instrument calibration or assay interference [37] [38].

B. Propagating Error to Parameters: The uncertainty in the raw data propagates into the fitted parameters. For nonlinear fits, this is derived from the covariance matrix of the fit. The square roots of the diagonal elements give the standard errors (SE) of each parameter. A 95% confidence interval can be approximated as θ̂ ± 1.96SE.

C. Critical Diagnostic: Residual Analysis Examining residuals (observed - predicted) is non-negotiable for validating model assumptions [34].

Diagram: Diagnostic Residual Analysis Workflow

A random scatter of residuals indicates the model adequately describes the data. A systematic pattern (e.g., a "U-shape") indicates a fundamental model failure, necessitating selection of a more complex model (e.g., moving from Michaelis-Menten to a biphasic or allosteric model) [34].

Application in Advanced Enzyme Kinetic Research

Fitting Complex and Networked Systems

Modern enzyme kinetics often involves systems beyond simple Michaelis-Menten hyperbolas.

- Inhibition Studies: Competitive, uncompetitive, and non-competitive inhibition are diagnosed by how the inhibitor changes the apparent Km and Vmax. Each mechanism has a distinct modified rate equation for fitting [32].

- dQSSA for Networks: When modeling enzymatic cascades or metabolic networks, the differential QSSA (dQSSA) provides a balance between the simplicity of Michaelis-Menten and the accuracy of full mass-action models. It reduces parameter dimensionality while relaxing the restrictive low-enzyme assumption, leading to more reliable in vivo predictions [25].

- Multi-Substrate Mechanisms: Models for ordered-sequential, random-sequential, or ping-pong mechanisms require fitting data from varying concentrations of multiple substrates, yielding a set of kinetic constants (Km for each substrate, Ki for dissociation) [32].

A Practical Example: Distinguishing Single vs. Double Exponential Decay

While not an enzyme kinetic example per se, the process of fitting fluorescence decay data to exponential models perfectly illustrates the model discrimination process [34]. An initial fit to a single exponential decay (F = A*exp(-t/τ)) yielded a curve that visually seemed adequate. However, residual analysis revealed a pronounced systematic pattern. Refitting the same data to a double exponential model (F = A[f*exp(-t/τ₁) + (1-f)*exp(-t/τ₂)]) eliminated the pattern in the residuals and produced a significantly better fit, correctly identifying the underlying biophysical process of two distinct fluorescent states. This directly parallels the need in enzyme kinetics to reject an inadequate simple model in favor of a more complex, correct one.

The rigorous journey from experimental data to model parameters is the cornerstone of quantitative enzyme kinetics. It requires a disciplined, iterative process: selecting a mechanistically plausible model, fitting the data with appropriate numerical methods, and—most critically—subjecting the fit to stringent diagnostic checks like residual analysis. Understanding and propagating error is essential for stating meaningful confidence in the derived parameters, such as Km and Vmax. As enzyme kinetics advances towards modeling complex in vivo networks and allosteric systems, frameworks like the dQSSA and sophisticated fitting protocols become increasingly vital [25] [32]. By adhering to this structured guide, researchers ensure their conclusions about enzyme mechanism, inhibition, and cellular function are built upon a solid, statistically defensible foundation.

Enzyme kinetics provides the fundamental quantitative framework for describing the rates of drug metabolism, a cornerstone of pharmacokinetics. The integration of these detailed mechanistic models into Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic (PBPK/PD) platforms represents a paradigm shift in systems pharmacology. This integration moves beyond descriptive, data-fitting models to predictive, mechanism-driven simulations of drug behavior in the human body [39]. A PBPK model is a mathematical framework that integrates human physiological and anatomical parameters with drug-specific physicochemical and biochemical properties to quantitatively predict pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles in specific tissues or human populations [39]. By explicitly incorporating enzyme kinetic parameters—such as Vmax (maximum reaction velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant)—within a physiological context, these advanced models can simulate complex interactions and extrapolate drug behavior to untested clinical scenarios. This approach is particularly valuable for predicting drug-drug interactions (DDIs), optimizing doses for special populations, and de-risking drug development, thereby addressing the high attrition rates historically seen in clinical trials [40]. The evolution of this field reflects a broader thesis in pharmaceutical research: that rigorous, principle-based kinetic modeling is essential for translating in vitro biochemical data into accurate predictions of in vivo clinical outcomes.

Foundational Principles: From Michaelis-Menten to Systems Pharmacology

Core Enzyme Kinetic Concepts

Enzyme kinetics is the mathematical description of how enzymes, as biological catalysts, speed up biochemical reactions [32]. The foundational model for a single-substrate reaction is the Michaelis-Menten equation: v = (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S]) where v is the reaction velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, Vmax is the maximum velocity, and Km is the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity [31]. The parameter Km provides a measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate (a lower Km indicates higher affinity), while Vmax relates to the catalytic capacity or turnover number [31]. These parameters are derived from in vitro experiments using human-derived tissues (e.g., liver microsomes, recombinant enzymes) and form the critical "drug-biological properties" input for PBPK models [41].

Advanced Kinetic Mechanisms

Real-world drug metabolism often involves more complex kinetics than the simple Michaelis-Menten model. Advanced mechanisms must be characterized and modeled for accurate prediction:

- Inhibition Kinetics: Inhibitors reduce enzyme activity through competitive (binds active site), uncompetitive (binds enzyme-substrate complex), or non-competitive (binds both free enzyme and complex) mechanisms, each affecting Km and Vmax differently [32]. This is central to DDI prediction.

- Multi-Substrate Reactions: Many metabolic reactions involve two substrates (e.g., cytochrome P450 reactions require drug and oxygen). Models like the ordered-sequential or ping-pong mechanisms are required [32].

- Allosteric Regulation and Cooperativity: Some enzymes display sigmoidal kinetics, described by the Hill equation, where binding of one substrate molecule affects the binding of subsequent molecules [32].

The PBPK Modeling Framework

PBPK modeling employs a "bottom-up" or "middle-out" approach, constructing the body as a network of physiological compartments (organs and tissues) interconnected by the circulatory system [42] [41]. Differential equations based on mass balance govern drug movement. The model integrates three core parameter types:

- Organism/System Parameters: Species- and population-specific physiological data (organ volumes, blood flow rates, tissue composition) [41].

- Drug Parameters: Physicochemical properties (lipophilicity (logP), pKa, molecular weight, solubility) which inform passive distribution [41].

- Drug-Biological Interaction Parameters: This is where enzyme kinetics is integrated, including fraction unbound in plasma (fu), tissue-plasma partition coefficients (Kp), and crucially, metabolic clearance parameters derived from enzyme kinetics (Vmax, Km) [41].

Table 1: Key Parameter Types in a PBPK Model Integrating Enzyme Kinetics

| Parameter Category | Description | Source/Typical Assay | Role in PBPK Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Parameters | Organ volumes, blood flows, tissue composition | Physiological literature, population databases | Defines the anatomical and physiological structure of the virtual population. |

| Drug Physicochemical Parameters | Lipophilicity (LogP/LogD), pKa, solubility, molecular weight | In vitro assays (e.g., shake-flask, potentiometric titration) | Predicts passive diffusion, membrane permeability, and tissue partitioning. |

| Drug-Biological Parameters: Protein Binding | Fraction unbound in plasma (fu) and tissues | Equilibrium dialysis, ultrafiltration | Determines the free drug concentration available for metabolism, distribution, and activity. |

| Drug-Biological Parameters: Metabolism (Enzyme Kinetics) | Km (affinity), Vmax (capacity), CLint (Vmax/Km) | In vitro incubation with human liver microsomes (HLM), hepatocytes, or recombinant enzymes | Quantifies the metabolic clearance rate for each enzyme pathway. The core input for IVIVE. |

| Drug-Biological Parameters: Transport | Transporter affinity (Km) and capacity (Jmax) | Cell systems overexpressing specific transporters (e.g., MDCK, HEK293) | Defines active uptake or efflux in organs like the liver, kidney, and intestine. |

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for integrating enzyme kinetic data into a PBPK/PD modeling and simulation framework.

Quantitative Data: Genetic Polymorphisms and Regulatory Impact

The predictive power of enzyme kinetic-integrated PBPK models is most evident when quantifying the impact of inter-individual variability. Genetic polymorphisms in drug-metabolizing enzymes lead to distinct phenotypic populations (e.g., poor, intermediate, normal, rapid, and ultrarapid metabolizers), which can be modeled by adjusting the abundance or activity (Vmax) of the relevant enzyme in the virtual population [43].

Table 2: Phenotype Frequencies of Key CYP Enzymes Across Populations [43]

| Enzyme | Phenotype | European (%) | East Asian (%) | Sub-Saharan African (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|