Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation: A Comprehensive Comparison of Traditional and Machine Learning Methods

This article provides a thorough comparison of enzyme kinetic parameter estimation methods, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation: A Comprehensive Comparison of Traditional and Machine Learning Methods

Abstract

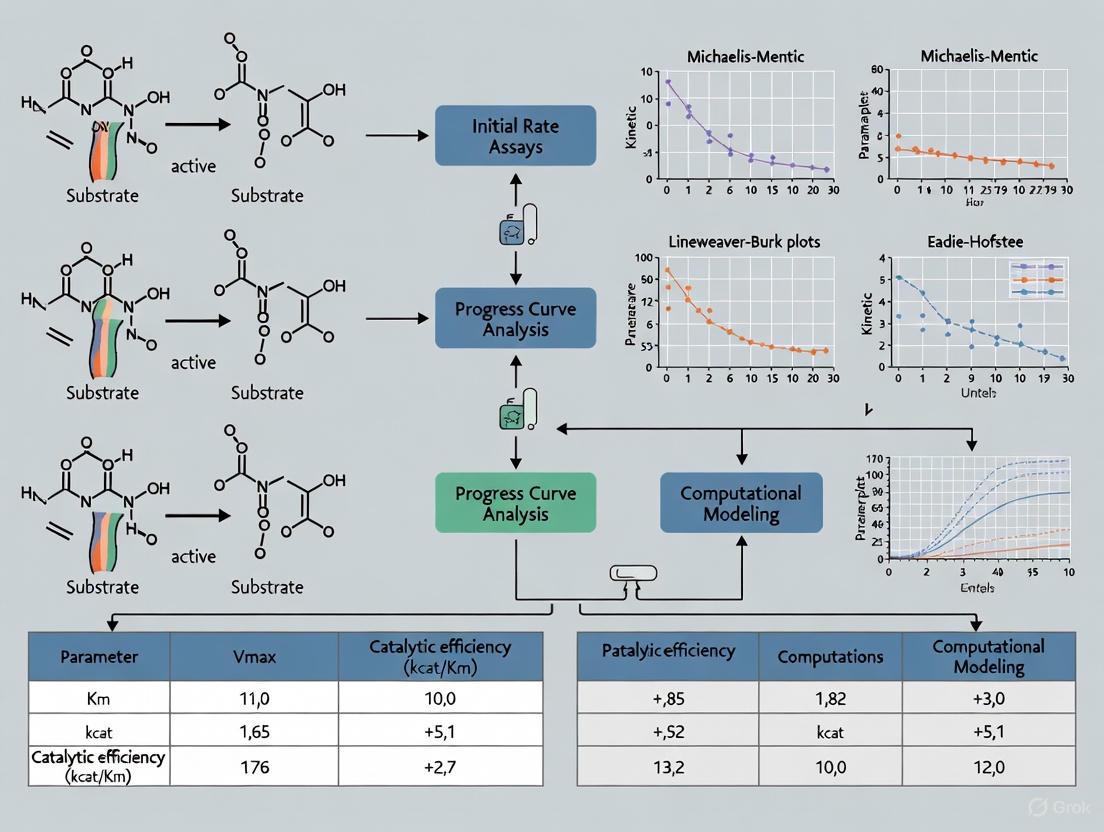

This article provides a thorough comparison of enzyme kinetic parameter estimation methods, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of Michaelis-Menten kinetics and key parameters (kcat, Km, Ki), explores traditional experimental assays alongside modern machine learning frameworks like CatPred, and addresses critical challenges including parameter identifiability and data reliability. The content also details best practices for model validation, uncertainty quantification, and selecting the appropriate method based on specific research goals, synthesizing key takeaways to guide future biomedical research and clinical applications.

Core Principles of Enzyme Kinetics: Understanding kcat, Km, and Ki

First proposed in 1913, the Michaelis-Menten model remains a cornerstone of enzymology, providing the fundamental framework for quantifying enzyme-substrate interactions and catalytic efficiency [1] [2]. This model's enduring relevance stems from its ability to describe reaction rates through two essential parameters: the Michaelis constant (Kₘ) and the maximum reaction velocity (Vₘₐₓ) [3]. While traditional estimation methods like Lineweaver-Burk plots dominated early research, contemporary science has witnessed significant methodological evolution toward nonlinear regression and machine learning approaches that offer enhanced accuracy and throughput [4] [5]. This review systematically compares classical and modern parameter estimation techniques, examining their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and applications in current drug development and basic research.

The Michaelis-Menten equation originated from the collaborative work of Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten, who in 1913 published their seminal paper "Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung" based on studies of the enzyme invertase [2]. Their work built upon earlier concepts by Victor Henri but introduced critical improvements in experimental methodology, particularly through pH control and initial velocity measurements, which enabled the first rigorous quantitative analysis of enzyme kinetics [2]. The model proposed that enzymes catalyze reactions by forming a transient enzyme-substrate complex, with the reaction rate following a hyperbolic dependence on substrate concentration according to the equation:

v = (Vₘₐₓ × [S]) / (Kₘ + [S])

where v represents the initial reaction velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, Vₘₐₓ is the maximum reaction rate achieved when enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate, and Kₘ (the Michaelis constant) equals the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vₘₐₓ [1] [3]. The constant Kₘ provides a measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate, with lower values indicating higher affinity [3]. The catalytic efficiency is quantified by the specificity constant k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ, where k꜀ₐₜ (the catalytic constant) represents the number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time when the enzyme is fully saturated [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Parameters of Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Biochemical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis Constant | Kₘ | Substrate concentration at half Vₘₐₓ | Measure of enzyme-substrate affinity |

| Maximum Velocity | Vₘₐₓ | Maximum reaction rate at enzyme saturation | Proportional to k꜀ₐₜ and enzyme concentration |

| Catalytic Constant | k꜀ₐₜ | Turnover number (Vₘₐₓ/[E]ₜₒₜ) | Catalytic efficiency per active site |

| Specificity Constant | k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ | Second-order rate constant for substrate capture | Overall measure of catalytic efficiency |

Comparative Analysis of Parameter Estimation Methods

Traditional Linearization Approaches

Traditional methods for estimating Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ relied on linear transformations of the Michaelis-Menten equation, enabling researchers to determine parameters using linear regression before widespread computational resources were available [4]. The most prominent among these, the Lineweaver-Burk plot, uses a double-reciprocal transformation (1/v versus 1/[S]) to produce a straight line with a y-intercept of 1/Vₘₐₓ and an x-intercept of -1/Kₘ [3]. Similarly, the Eadie-Hofstee plot graphs v versus v/[S], yielding a slope of -Kₘ and a y-intercept of Vₘₐₓ [4]. While these linear methods gained widespread adoption due to their simplicity and straightforward graphical interpretation, they introduce significant statistical limitations. The transformations distort experimental error distribution, violating key assumptions of linear regression and potentially producing biased parameter estimates, particularly with noisy data [4].

Modern Nonlinear and Computational Methods

Contemporary enzyme kinetics has increasingly shifted toward nonlinear regression methods that fit the untransformed rate data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation [4]. These approaches maintain the original error structure and provide more accurate and precise parameter estimates compared to linearized methods [4]. A comprehensive 2018 simulation study systematically compared five estimation methods using Monte Carlo simulations with 1,000 replicates, revealing that nonlinear regression approaches consistently outperformed traditional linearization methods in both accuracy and precision, particularly when data incorporated combined error models [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Michaelis-Menten Parameter Estimation Methods

| Estimation Method | Key Principle | Relative Accuracy | Relative Precision | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | Double-reciprocal linearization | Low | Low | Severe error distortion; unreliable with noisy data |

| Eadie-Hofstee (EH) | v vs. v/[S] plot | Moderate | Moderate | Error propagation issues |

| Nonlinear Vi-[S] (NL) | Direct nonlinear fitting of initial rates | High | High | Requires accurate initial velocity measurements |

| Nonlinear [S]-time (NM) | Full progress curve analysis | Highest | Highest | Requires extensive time-course data |

The most significant advancement comes from nonlinear regression analyzing substrate-time data (designated as NM in comparative studies), which fits the complete reaction progress curve to the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation using numerical integration [4]. This approach eliminates the need for precise initial rate measurements and can yield excellent parameter estimates even when up to 70% of substrate has been consumed, circumventing the traditional requirement of limiting measurements to the first 5-20% of the reaction [6].

Ultra-High-Throughput and Machine Learning Approaches

Recent technological innovations have pushed enzyme kinetics into unprecedented throughput realms. The DOMEK (mRNA-display-based one-shot measurement of enzymatic kinetics) platform enables simultaneous determination of k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ values for hundreds of thousands of enzymatic substrates in parallel, far surpassing the capacity of traditional instrumentation-based methods [7]. This approach uses mRNA display and next-generation sequencing to quantitatively analyze enzymatic time courses, achieving throughput levels unattainable by conventional techniques [7].

Concurrently, machine learning frameworks like CatPred leverage deep learning architectures and pretrained protein language models to predict in vitro enzyme kinetic parameters (k꜀ₐₜ, Kₘ, and Kᵢ) directly from sequence and structural information [5]. CatPred incorporates uncertainty quantification, providing researchers with confidence metrics for predictions and demonstrating competitive performance with existing methods while offering substantially greater scalability [5]. These computational approaches address critical bottlenecks in kinetic parameterization, especially for applications in metabolic engineering and drug discovery where experimental characterization cannot keep pace with sequence discovery [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Traditional Initial Velocity Determination

The classical protocol for Michaelis-Menten parameter estimation involves measuring initial velocities at varying substrate concentrations while maintaining enzyme concentration constant [2] [8]. The standard methodology requires that substrate consumption does not exceed 10-20% during the measurement period to approximate true initial conditions where substrate concentration remains essentially constant [6]. Reactions are typically monitored spectrophotometrically by following the appearance of product or disappearance of substrate continuously, with the initial linear portion of the progress curve used to calculate velocity [8]. For discontinuous assays requiring HPLC or other separation methods, multiple time points must be collected during the early reaction phase to establish the initial rate [6].

Progress Curve Analysis Protocol

As an alternative to traditional initial rate methods, full progress curve analysis utilizes the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation to estimate parameters from a single reaction time course [6]. The standard protocol involves: (1) initiating the enzymatic reaction with a defined substrate concentration; (2) monitoring product formation or substrate depletion throughout the reaction until approaching completion or equilibrium; (3) fitting the complete time course data to the integrated rate equation using nonlinear regression; (4) verifying enzyme stability during the assay using Selwyn's test [6]. This approach is particularly valuable for systems where obtaining initial rate measurements is technically challenging or when substrate concentrations approach detection limits [6].

High-Throughput DOMEK Protocol

The DOMEK methodology represents a radical departure from conventional kinetics, enabling ultra-high-throughput screening through mRNA display [7]. The experimental workflow comprises: (1) preparation of a genetically encoded library of peptide substrates (>10¹² unique sequences); (2) enzymatic reactions performed with the library in a non-compartmentalized format; (3) isolation of modified substrates at multiple time points; (4) quantification of reaction yields via next-generation sequencing; (5) computational fitting of time-course data to extract k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ values for hundreds of thousands of substrates simultaneously [7]. This method has been successfully applied to profile substrate specificity landscapes of promiscuous post-translational modification enzymes, generating kinetic parameters for approximately 286,000 substrates in a single experiment [7].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in Kinetic Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometric Assays | Continuous monitoring of reaction progress via absorbance changes | Traditional initial rate determination; real-time kinetics |

| Radiometric Assays | Highly sensitive detection through incorporation or release of radioactivity | Low-abundance enzymes; trace substrate conversion |

| Mass Spectrometry | Precise quantification using stable isotope labeling | Complex reaction mixtures; substrate specificity profiling |

| mRNA Display Libraries | Genetically encoded substrate libraries for ultra-high-throughput screening | DOMEK platform; substrate specificity mapping |

| Fluorescent Dyes/Cofactors | Single-molecule enzyme kinetics through fluorescence changes | Pre-steady-state kinetics; mechanistic studies |

| NONMEM Software | Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling for parameter estimation | Population-based kinetic analysis; precision dosing |

Applications in Drug Development and Biotechnology

Michaelis-Menten kinetics provides the foundational principles for understanding drug metabolism and enzyme inhibition in pharmaceutical development [4]. The parameters Kₘ and k꜀ₐₜ are essential for predicting in vivo metabolic rates, drug-drug interactions, and optimizing dosage regimens [4]. Plasma enzyme assays based on Michaelis-Menten principles serve as critical diagnostic tools in clinical medicine, with abnormal enzyme levels indicating tissue damage or disease states [3]. For instance, elevated levels of creatine kinase MB isoenzyme signal myocardial infarction, while increased aspartate transaminase indicates potential liver damage [3].

In biotechnology and metabolic engineering, kinetic parameters inform the design and optimization of biosynthetic pathways [5] [9]. The development of genome-scale kinetic models incorporating Michaelis-Menten parameters enables prediction of metabolic behaviors under different genetic and environmental conditions [9]. Frameworks like SKiMpy, Tellurium, and MASSpy facilitate semiautomated construction of kinetic models by sampling parameter sets consistent with thermodynamic constraints and experimental data [9]. These computational approaches allow researchers to identify rate-limiting steps in metabolic pathways and prioritize enzyme engineering targets for improved production of valuable compounds [5] [9].

The Michaelis-Menten model continues to serve as an indispensable foundation for enzymology more than a century after its introduction, testament to its robust theoretical framework and practical utility. While the fundamental equation remains unchanged, methodological advances have transformed parameter estimation from simplistic linear transformations to sophisticated computational approaches. Modern nonlinear regression methods provide more accurate and precise parameter estimates than traditional linearizations, with progress curve analysis offering practical advantages for challenging experimental systems [4] [6].

The emerging paradigm of ultra-high-throughput kinetics, exemplified by the DOMEK platform, and machine learning prediction frameworks like CatPred are revolutionizing enzyme kinetics, enabling characterization at scales previously unimaginable [7] [5]. These developments are particularly valuable for drug discovery and metabolic engineering, where comprehensive understanding of enzyme specificity and efficiency guides development of therapeutics and bioprocesses. As kinetic modeling continues to advance toward genome-scale integration, the Michaelis-Menten equation will undoubtedly remain central to quantitative analyses of enzymatic behavior, maintaining its legacy as one of the most enduring and impactful models in biochemical research.

The quantitative characterization of enzyme activity is fundamental to understanding metabolic pathways, designing biocatalytic processes, and developing therapeutic drugs. Enzyme kinetics provides a framework for this characterization, with several key parameters offering a window into the efficiency, speed, and regulation of enzymatic reactions. Among these, the catalytic turnover number (kcat), the Michaelis constant (Km), and the inhibition constant (Ki) are paramount. These parameters are indispensable for researchers and scientists aiming to compare enzyme performance, predict cellular behavior, and engineer novel enzymes with enhanced properties. [10] [1]

The kcat and Km values are derived from the Michaelis-Menten model, which describes the kinetics of many enzyme-catalyzed reactions involving the transformation of a single substrate into a product [1]. This report will define these core parameters, detail the experimental and computational methodologies used for their estimation, and provide a comparative analysis of emerging deep-learning tools that are revolutionizing the field of enzyme kinetic parameter prediction.

Defining the Core Parameters

2.1 Catalytic Turnover Number (kcat)

The catalytic turnover number, or kcat, is the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit of time when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [11] [12]. It represents the enzyme's intrinsic speed at its maximum operational capacity. The unit for kcat is time^{-1} (e.g., s^{-1}). Mathematically, it is defined as V_max / [E_total], where V_max is the maximum reaction rate and [E_total] is the total enzyme concentration [11]. This parameter reveals the catalytic power of an enzyme's active site, with values ranging from as low as 0.14 s^{-1} for chymotrypsin to an astonishing 4.0 x 10^5 s^{-1} for carbonic anhydrase [1].

2.2 Michaelis Constant (Km)

The Michaelis constant, or Km, is defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of V_max [11] [12]. It provides a quantitative measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate: a lower Km value indicates a higher affinity, meaning the enzyme requires a lower substrate concentration to become semi-saturated and achieve half of its maximum velocity. The Km is independent of enzyme concentration and is specific to an enzyme-substrate pair under defined conditions. Its value can vary widely, from 5.0 x 10^{-6} M for fumarase to 1.5 x 10^{-2} M for chymotrypsin [1].

2.3 Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km)

The ratio kcat/Km is a vital parameter that describes the catalytic efficiency of an enzyme [12]. It combines information about both the speed of the reaction (kcat) and the binding affinity (Km). A higher kcat/Km value indicates a more efficient enzyme, particularly at low substrate concentrations. This ratio is especially useful for comparing the efficiency of different enzymes or the same enzyme acting on different substrates [1] [12]. For example, fumarase has a high catalytic efficiency of 1.6 x 10^8 M^{-1}s^{-1}, while pepsin's is 1.7 x 10^3 M^{-1}s^{-1} [1].

2.4 Inhibition Constant (Ki)

The inhibition constant, Ki, quantifies the potency of an enzyme inhibitor. It is the dissociation constant for the enzyme-inhibitor complex; a lower Ki value signifies a tighter binding and a more potent inhibitor [5]. Ki is crucial in pharmaceutical sciences for characterizing drug candidates, as it helps predict how effectively a molecule can suppress the activity of a target enzyme.

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Estimation

3.1 Determining kcat and Km via Initial Rate Measurements

The classical method for determining kcat and Km involves measuring the initial velocity of an enzymatic reaction at a series of substrate concentrations [11].

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a set of reaction tubes, each containing the same amount of enzyme and buffer, but with varying concentrations of substrate, ranging from well below to well above the anticipated

Kmvalue. - Initial Rate Measurement: For each tube, initiate the reaction and allow it to proceed for a short, fixed time interval to ensure that only a small fraction (typically <5%) of the substrate is consumed, and product formation is linear with time.

- Product Quantification: Stop the reaction and measure the concentration of product formed in each tube. The initial velocity (

v) for each reaction is calculated asv = [product] / time. - Data Analysis: Plot the initial velocity (

v) against the substrate concentration ([S]). The data are fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation:v = (V_max * [S]) / (K_m + [S]).V_maxis identified as the plateau value the curve asymptotically approaches, andKmis the substrate concentration that yieldsV_max/2[11]. Thekcatis then calculated from the determinedV_maxusing the formulakcat = V_max / [E_total].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a set of reaction tubes, each containing the same amount of enzyme and buffer, but with varying concentrations of substrate, ranging from well below to well above the anticipated

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

3.2 Key Research Reagent Solutions The following table details essential materials and their functions in a typical enzyme kinetics experiment.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Enzyme Kinetics Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst whose kinetic parameters are being characterized. Must be of high purity and known concentration ([E_total]). |

| Substrate | The molecule upon which the enzyme acts. Must be available in pure form for accurate concentration preparation. |

| Reaction Buffer | Maintains a constant pH optimal for enzyme activity and stability, preventing denaturation. |

| Cofactors/Ions | Required by many enzymes for activity (e.g., Mg^{2+}, NADH, Zn^{2+} in carbonic anhydrase) [13]. |

| Detection Reagent | Allows for quantification of product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., a chromogenic dye or coupled enzyme system). |

| Inhibitor (for Ki) | A molecule used to study enzyme regulation and to determine the inhibition constant (Ki). |

Computational Prediction of Kinetic Parameters

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have led to the development of computational models that predict kinetic parameters directly from enzyme sequences and substrate structures, offering a high-throughput alternative to laborious experiments [14] [15] [5].

4.1 Overview of Deep Learning Frameworks

Several models have been developed to predict kcat, Km, and Ki. These models typically use enzyme amino acid sequences and substrate representations (e.g., SMILES strings) as input.

- CatPred: A comprehensive deep learning framework that predicts

kcat,Km, andKivalues. It utilizes pretrained protein language models (pLMs) and 3D structural features to enable robust predictions. A key feature of CatPred is its ability to provide query-specific uncertainty estimates, which helps researchers gauge the reliability of each prediction [5]. - RealKcat: This model employs a gradient-boosted decision tree architecture. It is trained on a manually curated dataset of 27,176 experimental entries (KinHub-27k) and is noted for its high sensitivity to mutations, especially those at catalytically essential residues. It frames the prediction as a classification problem, clustering

kcatandKmvalues by orders of magnitude [14]. - CataPro: A deep learning model based on pre-trained models and molecular fingerprints to predict

kcat,Km, andkcat/Km. CataPro has been demonstrated to have enhanced accuracy and generalization ability on unbiased datasets and has been successfully used in enzyme mining and engineering projects [15].

4.2 Comparative Performance of Prediction Models The following table summarizes the key features and reported performance of these state-of-the-art models.

Table 2: Comparison of Deep Learning Models for Kinetic Parameter Prediction

| Model | Key Features | Reported Performance | Uncertainty Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatPred [5] | Uses pLM and 3D structural features; predicts kcat, Km, Ki; trained on ~23k (kcat), ~41k (Km), ~12k (Ki) data points. |

Competitive with existing methods; enhanced performance on out-of-distribution samples using pLM features. | Yes (a key feature) |

| RealKcat [14] | Gradient-boosted trees; trained on manually curated KinHub-27k dataset; classifies parameters by order of magnitude. | >85% test accuracy for kcat/Km; 96% "e-accuracy" (within one order of magnitude) on a PafA mutant validation set. |

Not explicitly mentioned |

| CataPro [15] | Uses ProtT5 pLM for enzymes and MolT5+MACCS for substrates; predicts kcat, Km, kcat/Km. |

Shows clearly enhanced accuracy and generalization on unbiased benchmark datasets. | Not explicitly mentioned |

| TurNup [5] | Gradient-boosted tree using ESM-1b enzyme features and reaction fingerprints; trained on a smaller dataset (~4k kcat). |

Good generalizability on test enzyme sequences dissimilar to training data. | No |

4.3 Workflow for Computational Prediction The general process for predicting kinetic parameters using these ML models involves several standardized steps, from data curation to model inference.

The parameters kcat, Km, and Ki form the cornerstone of quantitative enzymology. While traditional experimental methods remain the gold standard for their determination, the field is rapidly evolving with the integration of sophisticated computational tools. Deep learning frameworks like CatPred, RealKcat, and CataPro are demonstrating remarkable accuracy in predicting these parameters, thereby accelerating enzyme discovery and engineering. For researchers in drug development and biotechnology, a dual approach—leveraging robust experimental data to validate and refine powerful predictive models—promises to be the most effective strategy for advancing the understanding and application of enzyme kinetics.

The Critical Role of Kinetic Parameters in Metabolic Modeling and Drug Discovery

Enzyme kinetic parameters—the maximal turnover number (kcat), Michaelis constant (Km), and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km)—serve as fundamental quantitative descriptors of enzymatic activity, defining the relationship between reaction velocity and substrate concentration [6]. In metabolic modeling, these parameters are indispensable for constructing predictive, dynamic models that can simulate how metabolic networks respond to genetic, environmental, or therapeutic perturbations [9]. Similarly, in drug discovery, characterizing the interaction between a potential drug and its enzyme target through kinetic parameters is crucial for understanding the mechanism of action, optimizing inhibitor potency, and predicting efficacy in vivo [16] [17]. The accurate determination and application of these parameters bridge the gap between static metabolic maps and dynamic, predictive biology, enabling advances in both basic science and applied biotechnology.

Kinetic Modeling Frameworks: A Comparative Analysis

The development of kinetic models has been transformed by new computational methodologies that address the historical challenges of parameterization speed, accuracy, and model scale [9]. The table below compares several modern frameworks for building kinetic models of metabolism.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Kinetic Modeling Frameworks

| Method/ Framework | Core Approach | Key Requirements | Principal Advantages | Reported Performance/Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RENAISSANCE [18] | Generative Machine Learning using Neural Networks & Evolution Strategies | Steady-state profiles (fluxes, concentrations); Thermodynamic data | No training data needed; Dramatically reduced computation time; Ensures physiologically relevant timescales | 92-100% model validity; E. coli model: 113 ODEs, 502 parameters |

| UniKP [19] | Unified Pre-trained Language Models for Parameter Prediction | Enzyme protein sequences; Substrate structures (SMILES) | Predicts kcat, Km, kcat/Km from sequence/structure; Accounts for pH/temperature | Test set R² = 0.68 for kcat prediction (20% improvement over prior tool) |

| SKiMpy [9] | Sampling & Model Pruning | Steady-state fluxes & concentrations; Thermodynamics | Efficient & parallelizable; Automatically assigns rate laws; Ensures relevant time scales | (Framework designed for large-scale model construction) |

| KETCHUP [9] | Parameter Fitting | Extensive perturbation data (wild-type & mutants) | Efficient parametrization with good fitting; Parallelizable and scalable | (Requires multi-condition data for reliable parameterization) |

Experimental Protocol: Generative ML for Kinetic Model Parameterization (RENAISSANCE)

The RENAISSANCE framework demonstrates a groundbreaking approach to parameterizing large-scale kinetic models without needing pre-existing training data [18].

- Input Preparation: Steady-state profiles of metabolite concentrations and metabolic fluxes are computed by integrating structural properties of the metabolic network (stoichiometry, regulatory structure, rate laws) with available multi-omics data (metabolomics, fluxomics, proteomics) and thermodynamic constraints [18].

- Generator Network Initialization: A population of feed-forward neural networks (generators) is initialized with random weights. Each generator is designed to take multivariate Gaussian noise as input and output a batch of kinetic parameters [18].

- Model Parameterization & Evaluation: The kinetic parameters produced by each generator are used to parameterize the kinetic model. The dynamics of each parameterized model are evaluated by computing the eigenvalues of its Jacobian matrix and the corresponding dominant time constants. Models producing dynamic responses that match experimentally observed timescales (e.g., a cell doubling time) are classified as "valid" [18].

- Optimization via Natural Evolution Strategies (NES):

- Reward Assignment: Each generator receives a reward based on the incidence of valid models it produces.

- Weight Update: The weights of all generators are combined, weighted by their normalized rewards, to create a parent generator for the next generation. High-performing generators have a greater influence, but lower-performing ones also contribute.

- Mutation: The parent generator's weights are mutated by injecting a predefined noise level, recreating a new population of generators for the next iteration [18].

- Iteration: Steps 3 and 4 are repeated for multiple generations until the generator meets a user-defined objective, such as maximizing the proportion of valid kinetic models produced [18].

Workflow Visualization: Kinetic Model Generation with RENAISSANCE

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, generative machine learning workflow of the RENAISSANCE framework.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Kinetic Studies

| Item | Type | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Datasets (Metabolomics, Fluxomics, Proteomics) | Data | Provides experimental constraints on metabolite concentrations, reaction fluxes, and enzyme levels for model construction and validation [18]. |

| Thermodynamic Data (e.g., Reaction Gibbs Free Energy) | Data/Calculation | Constrains reaction directionality and ensures the kinetic model is thermodynamically feasible [9]. |

| Enzyme Kinetic Databases (e.g., BRENDA, SABIO-RK) | Database | Repository of experimentally measured kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) used for model parameterization and validation [19]. |

| Stoichiometric Metabolic Model (e.g., Genome-Scale Model) | Model | Serves as a structural scaffold defining the network of reactions to be converted into a kinetic model [9]. |

| Pretrained Language Models (e.g., ProtT5 for proteins, SMILES transformer) | Computational Tool | Encodes protein sequences and substrate structures into numerical representations for machine learning-based parameter prediction [19]. |

Kinetic Parameters in Drug Discovery: From Mechanisms to Medicines

In drug discovery, particularly for enzyme targets, detailed kinetic characterization is vital for moving from simple inhibitor identification to developing optimized therapeutic candidates with a differentiated mechanism of action [16].

Table 3: Applications of Enzyme Kinetics in Drug Discovery and Development

| Application Area | Role of Kinetic Parameters | Impact on Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action Elucidation | Discriminate between different types of inhibition (e.g., competitive, non-competitive) and transient kinetics. | Informs the chemical strategy for lead optimization; can reveal unique, differentiated mechanisms [16]. |

| Lead Optimization | Guides the relationship between molecular structures of hits/leads and their kinetics of binding and inhibition. | Enhances the probability of translational success to the clinic [16]. |

| Target Residence Time Analysis | Measurement of drug-target residence time (the lifetime of the drug-target complex). | Provides an alternative, often more predictive, approach to optimizing in vivo efficacy compared to thermodynamic affinity (IC50) alone [16]. |

| Experimental Design | Using prior knowledge (e.g., Km) in Bayesian experimental design to optimize substrate concentrations and data points. | Increases the efficiency and information yield of kinetic experiments, saving time and resources [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Integrated Workflow for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for estimating enzyme kinetic parameters, adaptable to various measurement constraints.

Reaction Setup & Calibration:

Reaction Monitoring:

- Classical Initial Rate Method: Initiate the reaction and monitor the continuous (e.g., spectrophotometrically) or discontinuous (e.g., via HPLC) formation of product or disappearance of substrate. The initial rate (

v) is determined from the linear portion of the progress curve, where less than 10-20% of the substrate has been converted [6]. - Progress Curve Analysis: For systems where continuous monitoring is difficult, allow the reaction to proceed, converting a larger proportion of substrate (up to 70%). Measure the product concentration ([P]) at multiple time points (

t). This method requires the reaction to be practically irreversible, the enzyme to be stable, and no significant inhibition by products [6].

- Classical Initial Rate Method: Initiate the reaction and monitor the continuous (e.g., spectrophotometrically) or discontinuous (e.g., via HPLC) formation of product or disappearance of substrate. The initial rate (

Data Analysis:

- For Initial Rate Data: Fit the initial velocity (

v) at different initial substrate concentrations ([S]0) directly to the Henri-Michaelis-Menten (HMM) equation (v = (V * [S]0) / (Km + [S]0)) using nonlinear regression to extractVandKm[6]. - For Full Progress Curves: Fit the time-course data of [P] versus

tto the integrated form of the HMM equation:t = [P]/V + (Km/V) * ln([S]0/([S]0-[P])). This directly yields estimates forVandKmwithout the need for initial rate approximations and can be more reliable when a large fraction of substrate is consumed [6].

- For Initial Rate Data: Fit the initial velocity (

Model Validation: Use statistical tests and diagnostic plots (e.g., residual analysis) to evaluate the goodness-of-fit and the appropriateness of the Michaelis-Menten model for the enzyme system under study [17].

The field of kinetic modeling is undergoing a rapid transformation, moving toward the dawn of high-throughput and genome-scale kinetic models [9]. Key future directions include the continued development of unified, accurate prediction frameworks like UniKP that can seamlessly estimate all key kinetic parameters from sequence and substrate information [19]. Furthermore, the integration of generative machine learning methods, such as RENAISSANCE, with expansive kinetic databases and high-performance computing will enable the robust construction of large-scale models capable of providing unique insights into metabolic processes in health, disease, and biotechnology [18] [9]. In drug discovery, the efficient use of high-quality mechanistic enzymology, combined with biophysical methods and advanced experimental design, will enhance the identification and progression of compound series with an optimized kinetic profile and a higher probability of clinical success [16]. As these computational and experimental methodologies mature and converge, they will undoubtedly solidify the critical role of kinetic parameters as a cornerstone of predictive biology and rational therapeutic design.

For researchers in enzymology, selecting the appropriate data resource is crucial for experimental design, modeling, and validation. BRENDA, SABIO-RK, and the STRENDA Standards (including STRENDA DB) serve distinct yet complementary roles. The following comparison outlines their core characteristics, data handling methodologies, and optimal use cases to guide this selection.

Database Characteristics and Data Acquisition

The table below summarizes the fundamental attributes, data sources, and primary outputs of each resource.

| Feature | BRENDA | SABIO-RK | STRENDA DB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Comprehensive enzyme information [20] | Reaction-oriented kinetics [21] | Data reporting standards & validation [22] |

| Data Scope | Enzyme nomenclature, reactions, kinetics, organisms, substrates [20] | Kinetic parameters, rate laws/equations, experimental conditions [21] | Validated enzyme kinetics data and full experimental metadata [22] |

| Data Source | Scientific literature (primarily via KENDA text-mining) [20] | Manual curation from literature & direct lab submission [21] | Direct submission from researchers [22] |

| Curation Method | Automated text-mining augmented with manual curation [20] | Expert manual curation & automated consistency checks [21] | Automated validation against STRENDA Guidelines during submission [22] |

| Key Output | Extensive enzyme data, including kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) [20] | Kinetic data in SBML format for modeling tools [21] | STRENDA-compliant dataset with SRN & DOI [22] |

Functional Comparison and Practical Application

This table contrasts the practical application of each resource, highlighting their strengths and roles in the research workflow.

| Aspect | BRENDA | SABIO-RK | STRENDA DB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Breadth of information; most comprehensive resource [20] | Quality and model-readiness of kinetic data [21] | Ensuring data completeness, reproducibility, and FAIRness [22] [23] |

| Role in Workflow | Hypothesis generation, initial data exploration [20] | Systems biology modeling, network analysis [21] | Data publication, peer-review support, data sharing [22] |

| Data Quality | Varies; dependent on original publication quality [20] | High; due to manual expert curation [21] | High; enforced by standardized submission guidelines [22] |

| Initiative | Data extraction from existing literature [20] | Data curation and integration [21] | Data reporting standards before publication [22] [23] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Handling

Understanding how each resource acquires and processes data is key to evaluating its reliability.

BRENDA's Data Integration Protocol

BRENDA employs a mixed-method approach to populate its database [20].

- Automated Data Retrieval: The KENDA (Kinetic ENzyme DAtabase) tool uses text-mining to extract kinetic parameters from scientific literature automatically [20].

- Data Processing: In-house scripts process raw data into a uniform format. Redundancy is resolved by comparing annotations (EC number, UniProt ID, substrate, conditions), and geometric means are calculated for conflicting values [20].

- Annotation and Mapping: Enzyme annotations are extracted, and structures are mapped using UniProtKB IDs. Substrate IUPAC names are converted to SMILES notation using tools like OPSIN and PubChemPy [20].

- Quality Control: An outlier analysis prunes data points with values outside thrice the standard deviation of log-transformed parameter distributions [20].

SABIO-RK's Manual Curation Workflow

SABIO-RK prioritizes data quality through structured manual curation [21].

- Literature Selection: Publications are selected via keyword searches in PubMed, often in collaboration with systems biology projects [21].

- Structured Data Input: Curation staff uses a password-protected web interface with form fields and selection lists to input data into a temporary database [21].

- Data Standardization: Information is normalized and annotated using controlled vocabularies and ontologies (NCBI taxonomy, ChEBI, SBO). Reaction equations are automatically generated from substrates and products [21].

- Expert Verification and Transfer: A curation team of biological experts checks, complements, and verifies the data to eliminate errors and inconsistencies before transferring it to the public database [21].

STRENDA DB's Submission and Validation Process

STRENDA DB focuses on the pre-publication stage to ensure data quality at the source [22].

- Researcher Submission: Authors enter functional enzyme data from their manuscript into the STRENDA DB web submission tool [22].

- Automated Validation: The system automatically checks all entered data for compliance with the STRENDA Guidelines, flagging missing mandatory information or formal errors (e.g., pH range) [22].

- Data Structuring: Data is organized hierarchically: a "Manuscript" contains one or more "Experiments" (studies of a specific enzyme), and each Experiment contains one or more "Datasets" (results under defined assay conditions) [22].

- Registration and Access: Compliant datasets receive a perennial STRENDA Registry Number (SRN) and a Digital Object Identifier (DOI). Data becomes publicly available after the associated article is published [22].

Complementary Roles in Research Workflow

The following diagram illustrates how these resources can interact within a typical enzymology research pipeline, from literature mining to standardized reporting.

Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics

This table lists key reagents and tools essential for conducting and reporting enzyme kinetics experiments.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Enzyme Kinetics |

|---|---|

| UniProtKB | Provides unambiguous protein identifiers and sequence data, essential for reporting enzyme identity [22]. |

| PubChem | Database for small molecule information; used to definitively identify substrates and inhibitors [22]. |

| STRENDA DB Submission Tool | Web-based service to validate experimental data for completeness against community guidelines prior to publication [22]. |

| EnzymeML | Standardized data exchange format for enzymatic data, supporting reproducibility and data sharing [24]. |

| Controlled Buffers | Define assay pH and ionic strength; critical environmental parameters required for reproducible kinetics [22] [23]. |

BRENDA, SABIO-RK, and STRENDA Standards form a powerful, interconnected ecosystem for enzymology research. BRENDA offers unparalleled breadth for initial discovery. SABIO-RK delivers high-quality, model-ready kinetic data. The STRENDA Guidelines and DB address the root cause of poor data quality by standardizing reporting before publication. For robust and reproducible research, leveraging all three in tandem—using STRENDA to report new data, which then enriches BRENDA and SABIO-RK—represents the current best practice.

From Bench to Algorithm: Traditional Assays and Modern Machine Learning Approaches

Estimating enzyme kinetic parameters, such as the turnover number ((k{cat})) and the Michaelis constant ((KM)), is fundamental to understanding catalytic efficiency and enzyme function in both basic research and drug development. For over a century, the Michaelis-Menten equation has served as the cornerstone for analyzing enzyme kinetics. The two primary experimental assays for parameter estimation are the initial velocity assay (initial rate analysis) and the reaction progress curve assay (progress curve analysis). The initial velocity method measures the rate of reaction immediately after mixing enzyme and substrate, relying on the linear portion of the progress curve. In contrast, the progress curve analysis fits the entire timecourse of substrate consumption or product formation to an integrated rate equation. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two traditional methods, detailing their protocols, data analysis, and appropriate applications to inform research and development workflows.

Core Principles and Methodological Comparison

Initial Velocity Assay

The initial velocity assay involves measuring the initial rates of the reaction ((v_0)) over a range of substrate concentrations. The underlying principle is that, under conditions of substrate saturation, the velocity of the catalyzed reaction is directly proportional to the enzyme concentration. This method requires that the initial rate is measured during the steady-state period, where the enzyme-substrate intermediate concentration remains approximately constant, and only a small fraction of the substrate has been consumed.

- Key Assumption: The approximation that the amount of free substrate is nearly equal to the initial substrate amount is valid because measurements are taken over a very short period with a large excess of substrate.

- Historical Context: Initial rate experiments are the simplest to perform and analyze and are relatively free from complications such as back-reaction and enzyme degradation, making them the most commonly used type of experiment in enzyme kinetics [25].

Progress Curve Assay

The progress curve assay determines kinetic parameters from expressions for species concentrations as a function of time. The concentration of substrate or product is recorded from the initial fast transient period until the reaction approaches equilibrium. This method uses the entire progress curve, fitting the data to the solution of a differential equation or an integrated rate equation.

- Key Assumption: The model used to fit the progress curve must accurately describe the enzyme's behavior throughout the reaction. Recent advances suggest that models derived with the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQ) are accurate over a wider range of conditions, including when enzyme concentrations are not negligible compared to substrate concentrations, unlike the traditional standard QSSA (sQ) model [26].

- Modern Context: Although more technically challenging, the progress curve assay uses data more efficiently than the initial velocity assay [26].

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison of Initial Velocity and Progress Curve Assays

| Feature | Initial Velocity Assay | Progress Curve Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Measures initial reaction rates ((v_0)) at different substrate concentrations [27] [25] | Fits the complete timecourse of the reaction (progress curve) to a kinetic model [26] [28] |

| Primary Data Output | Initial velocity ((v_0)) vs. substrate concentration ([S]) plot [25] | Progress curve of product formation ([P]) or substrate consumption ([S]) over time (t) [26] |

| Data Analysis Method | Linear transforms (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk) or direct nonlinear fitting of the Michaelis-Menten equation to initial rates [26] | Nonlinear fitting of the complete progress curve to an integrated rate equation (e.g., Michaelis-Menten or tQ model) [26] [28] |

| Fundamental Requirement | Substrate must be in large excess over enzyme; only the initial, linear part of the reaction is used [27] [25] | The kinetic model must be valid for the entire course of the reaction, including non-linear phases [26] [28] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Initial Velocity Assay Protocol

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: Prepare a series of reactions with a fixed, known concentration of enzyme and varying concentrations of substrate. The initial substrate concentration should range from values well below the anticipated (K_M) to values well above it to observe saturation.

- Initiation and Monitoring: Initiate the reaction by adding the enzyme. For continuous assays, immediately begin monitoring the formation of product or consumption of substrate over time using an appropriate method (e.g., spectrophotometry, fluorometry).

- Initial Rate Determination: Record the change in signal (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence) for a short period after the steady state is established but before a significant fraction (typically <5-10%) of the substrate has been consumed. The slope of the linear part of this progress curve is the initial velocity, (v_0) [27] [25].

- Replication: Repeat steps 1-3 for each substrate concentration in the series.

Progress Curve Assay Protocol

- Single Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mixture with a fixed concentration of enzyme and a single initial concentration of substrate.

- Continuous Monitoring: Initiate the reaction and continuously monitor the product formation or substrate consumption until the reaction approaches equilibrium or the signal stabilizes. This generates a full progress curve [28].

- Model Fitting: Fit the obtained progress curve data to an appropriate kinetic model. The traditional model is the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation (sQ model). However, for greater accuracy, especially when enzyme concentration is not negligible, the model derived with the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQ model) is recommended [26]. The tQ model is described by: ( \dot{P} = k{cat} ET \frac{(ET + KM + ST - P) - \sqrt{(ET + KM + ST - P)^2 - 4 ET (ST - P)}}{2} ) where ( \dot{P} ) is the production formation rate, (ET) is total enzyme concentration, (ST) is total initial substrate concentration, and (P) is the product concentration [26].

Comparative Data Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of data analysis for both methods, highlighting key differences and decision points.

Performance and Application Analysis

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

The choice between initial velocity and progress curve assays involves trade-offs between experimental simplicity, data efficiency, and analytical rigor.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Assay Performance and Practical Considerations

| Aspect | Initial Velocity Assay | Progress Curve Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Data & Resource Efficiency | Requires many separate reaction runs to profile multiple [S]; can be substrate-intensive [26] | Can estimate parameters from a single progress curve; uses data more efficiently; less substrate required per parameter estimate [26] [28] |

| Parameter Identifiability | Requires [S] range from below to far above KM (often >10x KM) for reliable estimation, which can be difficult to achieve [26] [28] | Parameters can be identifiable with [S] around the KM level; optimal experiment design is simpler without prior KM knowledge [26] |

| Validity Conditions & Robustness | Validity of Michaelis-Menten equation requires enzyme concentration much lower than substrate + KM [26]. Simple and robust when conditions are strictly met. | The tQ model is accurate over wider conditions, including when enzyme concentration is not low [26]. More robust for in vivo-like conditions. |

| Handling of Non-Ideality | Only uses initial linear phase, avoiding complications like product inhibition or enzyme inactivation. | The full curve can be sensitive to non-idealities (e.g., inhibition, inactivation), which can be incorporated into more complex models for diagnosis [28]. |

| Technical & Computational Demand | Experimentally straightforward; data analysis is simple (linear or basic nonlinear regression) [25] | Requires high-quality continuous data; computational fitting is more complex, often requiring Bayesian inference or advanced algorithms [26] |

Supporting Experimental Data

A 2017 study systematically evaluated parameter estimation using Bayesian inference based on the standard QSSA (sQ) model (foundation of initial velocity analysis) and the total QSSA (tQ) model (suited for progress curve analysis). The study found that estimates obtained with the sQ model were "considerably biased when the enzyme concentration was not low," a restriction not required for the tQ model. Furthermore, the progress curve approach with the tQ model enabled accurate and precise estimation of kinetic parameters for diverse enzymes like chymotrypsin, fumarase, and urease from a minimal amount of timecourse data [26].

Another study highlighted that estimating enzyme activity through linear regression of the initial rate should only be applied when linearity is true, which is often not checked. In contrast, kinetic models for progress curve analysis can estimate maximum enzyme activity whether or not linearity is achieved, as they integrally account for the complete progress curve [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of either kinetic assay requires careful control of experimental conditions and the use of specific reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function in Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Buffers (e.g., MES, Phosphate) | Maintain constant pH, crucial for enzyme activity and stability [29] [28] | Choice of buffer type and ionic strength is critical; each enzyme has an optimal pH [29]. |

| Cofactors (e.g., NADH, Thiamine Pyrophosphate) | Essential for the catalytic activity of many enzymes; often act as cosubstrates [28] | Must be added at saturating concentrations to avoid becoming rate-limiting. |

| Spectrophotometer / Fluorometer | Instrument for continuous monitoring of reaction progress via absorbance or fluorescence change [25] | Must have precise temperature control (≤±0.1°C), as a 1°C change can cause 4-8% activity variation [29]. |

| Discrete Analyzer / Automated System | Performs automated reagent additions and measurements in discrete, low-volume cuvettes [29] | Eliminates edge effects and offers superior temperature control, improving reproducibility for high-quality progress curves [29]. |

| Stopping Agent (for discontinuous assays) | Halts the reaction at precise times for product quantification (e.g., by HPLC) [29] | Used if continuous monitoring is not feasible; requires careful validation of quenching efficiency [29]. |

| Pure Enzyme / Crude Extract | The catalyst of interest. | Specific activity should be determined; crude extracts require controls for interfering activities [28] [25]. |

Both initial velocity and progress curve assays are vital tools for elucidating enzyme kinetics. The initial velocity assay remains the gold standard for its simplicity and robustness when ideal conditions (low enzyme, high substrate) can be met, making it excellent for routine characterization. The progress curve assay, particularly when employing more accurate kinetic models like the tQ model, offers a powerful, data-efficient alternative. It reduces experimental burden, is valid under a broader range of conditions (including high enzyme concentrations relevant to in vivo contexts), and can provide more precise parameter estimates from minimal data.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection criteria are clear: choose the initial velocity method for straightforward, traditional analysis under defined in vitro conditions. Opt for progress curve analysis when dealing with precious materials, when enzyme concentration is high, when seeking highly precise parameter estimates, or when aiming to detect and model more complex kinetic phenomena. The ongoing development of automated analysis systems and sophisticated computational packages for Bayesian inference is making progress curve analysis increasingly accessible and reliable, positioning it as a cornerstone of modern enzyme kinetics research.

The accurate estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters is a cornerstone of quantitative biology and drug development. For decades, the standard Quasi-Steady-State Approximation (sQSSA), leading to the classic Michaelis-Menten equation, has been the default model for analyzing enzyme-catalyzed reactions. However, its application is restricted to idealized conditions of low enzyme concentration, limiting its utility for studying modern experimental systems, including intracellular environments. This comparison guide evaluates the Total Quasi-Steady-State Approximation (tQSSA) as a superior alternative for parameter estimation. We provide a direct, data-driven comparison of their performance, experimental validation protocols, and practical applications, contextualizing their use within contemporary enzyme kinetics research.

Enzyme kinetic parameters—the Michaelis constant ((KM)), the catalytic rate constant ((k{cat})), and the dissociation constant ((Kd))—are fundamental for characterizing enzyme function, understanding metabolic pathways, and screening potential therapeutic inhibitors. The traditional method for estimating these parameters relies on the sQSSA, which is valid only under the condition that the total enzyme concentration is much lower than the total substrate concentration and the Michaelis constant ((ET \ll ST + KM)) [30] [31]. In vitro experiments often satisfy this condition, but it is frequently violated in vivo and in many modern experimental setups, such as those involving enzyme excess [32] [33].

When the sQSSA is applied outside its validity domain, it leads to systematic errors in parameter estimation, distorting the true catalytic efficiency and binding affinity of the enzyme. The tQSSA was developed to overcome this limitation. By redefining the reaction's slow variable to the total substrate concentration, it provides a mathematically rigorous and more accurate approximation across a vastly broader range of enzyme and substrate concentrations [30] [31] [33]. This guide objectively compares these two approaches, providing researchers with the data and methodologies needed to select the optimal tool for accurate kinetic characterization.

Theoretical and Practical Performance Comparison

The core difference between the sQSSA and tQSSA lies in their choice of the slow variable and the resulting form of the governing equations. The sQSSA assumes the free substrate concentration is the slow variable, while the tQSSA uses the total substrate concentration (( \bar{S} = S + C )), which is a conserved quantity [31]. This simple change in perspective resolves the mathematical stiffness that plagues the sQSSA under conditions of high enzyme concentration.

Validity Domains and Estimation Accuracy

The following table summarizes the key differences in the validity and performance of the two approximation methods.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of sQSSA and tQSSA

| Feature | Standard QSSA (sQSSA) | Total QSSA (tQSSA) |

|---|---|---|

| Validity Condition | ( ET \ll ST + K_M ) [30] | Broadly valid for low and high enzyme concentrations (( ET \ll ST + KM ) and ( ST \ll ET + KM )) [30] [33] |

| Primary Limitation | Fails under high enzyme concentrations [31] | More complex mathematical formulation [31] |

| Accuracy in Deterministic Simulations | Poor outside its validity domain, can distort dynamics (e.g., dampen oscillations) [34] | Excellent across a wide parameter range; captures true system dynamics more reliably [34] [32] |

| Accuracy in Stochastic Simulations | Can be inaccurate even with timescale separation; accuracy depends on sensitivity of rate functions [34] | Generally more accurate than sQSSA, but not universally valid; can still distort dynamics in some stochastic systems [35] [36] |

| Parameter Estimation Fidelity | Tends to overestimate parameter values when (E_T) is significant [32] | Provides estimates much closer to real values, especially when (E_T) is not negligible [32] |

| Best-Suited For | Traditional in vitro assays with low enzyme concentrations. | In vivo modeling, high-throughput assays, and systems with any enzyme-to-substrate ratio. |

The superior accuracy of the tQSSA in deterministic contexts is well-established. For instance, in a genetic negative feedback model, the sQSSA reduced a limit cycle to damped oscillations, while the tQSSA correctly preserved the original system's oscillatory dynamics [34]. Furthermore, in "reverse engineering" tasks where models are fit to data to find unknown parameters, using the tQSSA yields estimates that are significantly closer to the true values, whereas the sQSSA "overestimates the parameter values greatly" [32].

A Note on Stochastic Simulations

A critical consideration for modern systems biology is the performance of these approximations in stochastic models, which are essential when molecular copy numbers are low. While the deterministic tQSSA is more robust than the sQSSA, recent research cautions against assuming this superiority automatically transfers to stochastic simulations.

The validity of the stochastic tQSSA depends not only on timescale separation but also on the sensitivity of the nonelementary reaction rate functions to changes in the slow species [34] [35]. The tQSSA results in less sensitive functions than the sQSSA, which generally makes it more accurate. However, applying the deterministic tQSSA directly to define propensity functions in stochastic simulations can sometimes distort dynamics, even when the deterministic approximation itself is valid [35] [36]. This highlights the need for caution and verification when using any deterministic QSSA for stochastic model reduction.

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

This section outlines detailed methodologies for estimating kinetic parameters using both the sQSSA and tQSSA, enabling researchers to implement and compare these techniques directly.

Traditional Protocol: Initial Rate Analysis with sQSSA

The sQSSA protocol is the classic method found in most biochemistry textbooks.

- Experiment: Perform a series of reactions with a fixed, low concentration of enzyme ((ET)) and varying concentrations of substrate ((ST)). The condition (ET \ll ST) must be maintained for all data points used in the fit.

- Measurement: Measure the initial velocity ((v_0)) of product formation for each substrate concentration.

- Analysis: Fit the Michaelis-Menten equation, ( v0 = \frac{V{max} [S]}{KM + [S]} ), to the ((v0), ([S])) data, where ([S]) is the free substrate concentration (often approximated by (ST) when (ET) is low). (V{max}) and (KM) are the fitted parameters.

- Calculation: Calculate (k{cat}) from (V{max} = k{cat} ET).

This workflow is based on the established sQSSA theory described in the search results [30] [31].

Advanced Protocol: Full Time-Course Analysis with tQSSA

The tQSSA leverages modern computational power to fit parameters directly from the full progress curve, which is more robust and works under a wider range of conditions.

- Experiment: Conduct a single reaction (or preferably a few for validation) with known initial concentrations of enzyme ((ET)) and substrate ((ST)). The ratio can be arbitrary, including (ET \approx ST) or (ET > ST).

- Measurement: Continuously monitor the concentration of product (P(t)) or total substrate (\bar{S}(t)) over time to obtain a full progress curve.

- Model Definition: Use the tQSSA rate equation derived from the reversible Michaelis-Menten scheme: [ \frac{d\bar{S}}{dt} = -k2 C + k{-2} (ET - C)(ST - \bar{S}) ] where the complex concentration (C) is defined implicitly by the solution of the quadratic equation: [ C = \frac{(ET + KM + \sigma) - \sqrt{(ET + KM + \sigma)^2 - 4 ET \sigma}}{2} ] and (\sigma \equiv \bar{S} + (k{-2}/k1)(ST - \bar{S})) [31].

- Parameter Fitting: Use non-linear regression to fit the parameters (k1), (k{-1}), (k2), and (k{-2}) (and thus (KM) and (k{cat})) directly to the experimental progress curve (P(t)) or (\bar{S}(t)) by numerically integrating the tQSSA ordinary differential equation (ODE).

This total QSSA-based sequential method for estimating all kinetic parameters of the reversible Michaelis-Menten scheme has been demonstrated as a robust alternative to traditional methods [30] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and computational tools required for implementing the tQSSA estimation protocol.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for tQSSA Implementation

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Preparation | High-purity enzyme at known concentration for setting up reactions with precise (E_T). |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Instrument for rapidly mixing enzyme and substrate and monitoring rapid, early reaction kinetics. |

| Quenched-Flow Instrument | Apparatus for halting a reaction at precise millisecond timescales for chemical analysis of intermediates. |

| Computational Software (e.g., R, Python, MATLAB) | Platform for numerically integrating the tQSSA ODE and performing non-linear regression analysis. |

| Fluorescent/Luminescent Substrate Analog | A substrate that generates a detectable signal upon conversion, enabling continuous progress curve monitoring. |

Decision Workflow and Comparative Analysis Diagrams

To aid in selecting the appropriate method, use the following decision workflow. The subsequent diagram illustrates the core conceptual difference between the two approximations.

Diagram 1: QSSA Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: Conceptual Framework of sQSSA vs. tQSSA

The Total Quasi-Steady-State Approximation represents a significant advancement in enzyme kinetics, effectively overcoming the limitations of the classic sQSSA. While the sQSSA remains a valid tool for simple, traditional assays, the tQSSA offers a more powerful and flexible framework for accurate parameter estimation across a wide spectrum of experimental conditions, including those relevant to drug development and systems biology. By adopting the tQSSA and the associated full time-course analysis protocol, researchers can achieve more reliable and accurate kinetic characterizations, leading to better predictive models and a deeper understanding of enzymatic mechanisms.

The accurate prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters—the turnover number (kcat), the Michaelis constant (Km), and the inhibition constant (Ki)—is a cornerstone of understanding and engineering biological systems. These parameters are pivotal for applications in metabolic engineering, drug discovery, and the development of biocatalysts. Traditionally, their determination has relied on costly, time-consuming experimental assays, creating a major bottleneck. The disparity between the millions of known enzyme sequences and the thousands with experimentally measured kinetics underscores this challenge [5]. Machine learning (ML), particularly deep learning, has emerged as a powerful tool to bridge this gap. By learning complex patterns from existing biochemical data, ML models can provide rapid, in silico estimates of kinetic parameters, thereby accelerating research and development. This guide objectively compares the performance and methodologies of several state-of-the-art ML frameworks, including the newly introduced CatPred, UniKP, CataPro, and others, providing researchers with the data needed to select the optimal tool for their work.

A diverse set of computational frameworks has been developed, each with distinct architectural philosophies and input requirements.

CatPred is a comprehensive deep learning framework designed to predict kcat, Km, and Ki. It explicitly addresses key challenges in the field, such as the evaluation of model performance on out-of-distribution enzyme sequences and the provision of reliable, query-specific uncertainty quantification for its predictions. It explores diverse feature representations, including pretrained protein language models (pLMs) and 3D structural features [5] [37].

UniKP is a unified framework that also predicts kcat, Km, and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km). It leverages pretrained language models for both enzyme sequences (ProtT5) and substrate structures (SMILES transformer). Its machine learning module employs an ensemble model (Extra Trees) that was selected after a comprehensive comparison of 16 different ML models. A derivative framework, EF-UniKP, incorporates environmental factors like pH and temperature [38].

CataPro is another neural network-based framework that uses ProtT5 for enzyme sequence embedding and combines MolT5 embeddings with MACCS keys fingerprints for substrate representation. A key feature of CataPro is its rigorous evaluation on unbiased datasets, created by clustering enzyme sequences to ensure no test enzyme is highly similar to any training enzyme, thus providing a more realistic assessment of generalization ability [15].

ENKIE takes a different approach by employing Bayesian Multilevel Models (BMMs). Instead of using raw sequence or structure data, it leverages categorical predictors like Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, substrate identifiers, and protein family annotations. This results in an inherently interpretable model that provides well-calibrated uncertainty estimates [39].

Specialized Architectures also exist for specific challenges. For instance, a three-module ML framework was developed to predict the temperature-dependent kcat/Km of β-glucosidase. This framework decomposes the problem into predicting the optimum temperature, the efficiency at that temperature, and the relative efficiency profile across temperatures [40].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow common to many of these deep learning frameworks, from data input to final prediction.

Performance Comparison: A Quantitative Analysis

Benchmarking these tools reveals their respective strengths and weaknesses across different kinetic parameters and evaluation scenarios. The coefficient of determination (R²) and Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) are common metrics, with higher values indicating better predictive performance.

Table 1: Prediction Performance forkcat

| Framework | Core Model Architecture | Test R² | Test PCC | Key Evaluation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatPred [5] | Deep Learning (pLM/3D features) | Competitive | N/A | Out-of-distribution & with uncertainty |

| UniKP [38] | Extra Trees (with pLM features) | 0.68 | 0.85 | Random split (vs. DLKcat baseline) |

| CataPro [15] | Neural Network (pLM/fingerprints) | N/A | ~0.41 (for kcat/Km) | Unbiased, sequence-split validation |

| ENKIE [39] | Bayesian Multilevel Model | 0.36 | N/A | Extrapolation to new reactions |

Table 2: Prediction Performance forKm

| Framework | Core Model Architecture | Test R² | Test PCC | Key Evaluation Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatPred [5] | Deep Learning (pLM/3D features) | Competitive | N/A | Out-of-distribution & with uncertainty |

| UniKP [38] | Extra Trees (with pLM features) | Similar to baseline | N/A | Uses dataset from Kroll et al. |

| ENKIE [39] | Bayesian Multilevel Model | 0.46 | N/A | Extrapolation to new reactions |

A critical differentiator among frameworks is their approach to evaluation. While some models report high performance on random train-test splits, others use more rigorous "unbiased" or "out-of-distribution" splits where test enzymes share low sequence similarity with training enzymes. For example, CataPro employs a sequence-similarity clustering (40% identity cutoff) to create its test sets, ensuring a tougher and more realistic assessment of its generalization capability [15]. CatPred also highlights its robust performance on out-of-distribution samples, a scenario where pretrained protein language model features are particularly beneficial [5].

Furthermore, UniKP demonstrated a significant 20% improvement in R² over an earlier model, DLKcat, on a standard kcat prediction task [38]. Meanwhile, ENKIE achieves performance comparable to more complex deep learning models while using only categorical features, and it provides well-calibrated uncertainty estimates that increase when predictions are made for reactions or enzymes distant from the training data [39].

Experimental Protocols: How the Frameworks Are Built and Tested

The development of a robust predictive framework follows a multi-stage process, from data curation to final validation. The methodologies cited in the performance comparisons are built upon detailed experimental protocols.

Data Curation and Preprocessing

The foundation of any model is its data. Most frameworks source their initial data from public kinetic databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK [5] [15] [39].

- Substrate Mapping: A critical step is the accurate mapping of substrate names to their chemical structures. This is typically done by converting common names to canonical SMILES strings using databases like PubChem, ChEBI, or KEGG [5].

- Sequence Retrieval: Enzyme sequences are obtained from UniProt using provided identifiers [15].

- Data Filtering: Entries with missing sequence or substrate information are filtered out. Some studies impose additional criteria to reduce measurement noise, though CatPred notes this can lead to information loss and bias [5].

Feature Representation

A key step is converting raw inputs into numerical features.

- Enzyme Representation: Most modern frameworks (CatPred, UniKP, CataPro) use embeddings from pretrained protein Language Models (pLMs) like ProtT5-XL-UniRef50. These models convert an amino acid sequence into a fixed-length vector that captures complex semantic and syntactic information [5] [15] [38].

- Substrate Representation: Common methods include:

Model Training and Evaluation

- Unbiased Evaluation: To prevent inflated performance metrics, CataPro and others use sequence-based splitting. Enzymes are clustered by sequence similarity (e.g., 40% identity), and clusters are assigned to training or test sets, ensuring no high-similarity sequences are shared between sets [15].

- Uncertainty Quantification: CatPred and ENKIE incorporate methods to estimate prediction uncertainty. CatPred uses probabilistic regression to distinguish between aleatoric (data noise) and epistemic (model uncertainty) variances, while ENKIE's Bayesian framework naturally provides posterior distributions [5] [39].

The following diagram illustrates the specialized three-module architecture designed for predicting enzyme activity across different temperatures, a complexity that single-module models struggle to capture.

The development and application of these ML frameworks rely on a suite of public databases, software tools, and computational resources.

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Relevance to Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA [5] [15] [39] | Database | Primary source of experimentally measured enzyme kinetic parameters. | Used as a core training data source for all major frameworks. |

| SABIO-RK [5] [15] [39] | Database | Repository for biochemical reaction kinetics. | Another key data source for model training and validation. |

| UniProt [15] [39] | Database | Provides comprehensive protein sequence and functional information. | Used to retrieve amino acid sequences for enzymes in the datasets. |

| PubChem [5] [15] | Database | Repository of chemical molecules and their biological activities. | Used to map substrate names to canonical SMILES strings. |

| ProtT5 [15] [38] | Pre-trained Model | Protein language model that generates numerical embeddings from sequences. | Used by UniKP, CataPro, and CatPred for enzyme feature representation. |

| SMILES Transformer [38] | Pre-trained Model | Language model that generates embeddings from SMILES strings. | Used by UniKP for substrate feature representation. |

| MACCS Keys [15] | Molecular Fingerprint | A set of 166-bit structural keys for representing molecular features. | Used by CataPro as part of its substrate representation. |

| CD-HIT [15] | Software Tool | Tool for clustering biological sequences to reduce redundancy. | Used by CataPro to create unbiased train/test splits. |

The advent of deep learning frameworks like CatPred, UniKP, and CataPro marks a significant leap forward in the computational prediction of enzyme kinetics. While they share common goals, their comparative analysis reveals distinct strengths: CatPred's emphasis on uncertainty quantification and out-of-distribution robustness, UniKP's strong overall performance and flexibility with environmental factors, CataPro's rigorous generalization on unbiased splits, and ENKIE's interpretability and calibrated uncertainties with minimal input data.

For researchers, the choice of tool depends on the specific application. For high-confidence predictions on novel enzyme sequences, a framework with robust out-of-distribution testing and uncertainty estimates is crucial. For tasks involving environmental conditions, EF-UniKP is currently a leading option. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with future progress likely hinging on larger and more standardized datasets, improved integration of physical constraints, and methods that offer greater interpretability to guide experimental design. These tools are poised to become indispensable assets in the toolkit of researchers and drug developers, accelerating the cycle of discovery and engineering in biochemistry.

The accurate estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters is a cornerstone of enzymology, metabolic engineering, and drug discovery. Traditional experimental methods for determining parameters such as ( k{cat} ) (turnover number) and ( Km ) (Michaelis constant) are often cost and time-intensive, creating a significant bottleneck in enzyme characterization [5]. The rapid expansion of protein sequence and structural data has catalyzed the development of computational methods to bridge this gap. At the heart of these advances lies feature representation—the process of transforming raw protein data into meaningful numerical descriptors that machine learning (ML) models can interpret. Two dominant paradigms have emerged: protein Language Models (pLMs) that learn evolutionary patterns from vast sequence databases, and 3D structural approaches that leverage the spatial arrangement of atoms and residues. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these feature representation strategies, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for enzyme kinetic parameter estimation.

Comparative Analysis of Feature Representation Methodologies

Protein Language Models (pLMs) for Sequence-Based Feature Extraction

Protein Language Models represent a transformative approach to feature extraction by learning contextual representations of amino acid sequences through self-supervised training on millions of protein sequences.