Enzyme Kinetics and Inhibition Models: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Drug Discovery Applications

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of enzyme kinetics and inhibition models in modern drug discovery and development.

Enzyme Kinetics and Inhibition Models: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of enzyme kinetics and inhibition models in modern drug discovery and development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article bridges fundamental theoretical concepts with practical applications across the pharmaceutical pipeline. It covers foundational principles of enzyme kinetics and inhibition mechanisms, advanced methodological approaches for kinetic analysis, troubleshooting strategies for common experimental challenges, and comparative validation of analytical techniques. By synthesizing current research and case studies, this resource provides essential insights for optimizing inhibitor design, accurately characterizing drug-target interactions, and translating biochemical data into clinically relevant therapeutic strategies.

Fundamental Principles of Enzyme Kinetics and Inhibition Mechanisms

Enzyme kinetics, the study of the rates of enzyme-catalyzed reactions, provides fundamental insights into cellular metabolism, drug action, and the design of industrial biocatalysts. At the heart of this field lies the work of Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten, who in 1913 proposed a mathematical model that remains the cornerstone of enzymology over a century later [1]. Their model, now known as Michaelis-Menten kinetics, serves to explain how enzymes achieve kinetic rate enhancement and how reaction rates depend on the concentrations of both enzyme and substrate [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this foundational model is not merely academic; it is essential for predicting metabolic fluxes, analyzing enzyme inhibition, and designing targeted therapeutics. Approximately 47% of all current drugs function by inhibiting enzyme targets, underscoring the critical importance of enzyme kinetics in pharmaceutical development [3]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of Michaelis-Menten kinetics, its modern applications in complex systems, its relationship to inhibition models, and advanced methodologies for high-throughput kinetic parameter determination.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formalism

The Basic Kinetic Scheme

The Michaelis-Menten model describes a minimal enzyme-catalyzed reaction involving a single substrate transforming into a single product. The model proposes a specific mechanism whereby the enzyme (E) first binds reversibly to its substrate (S) to form an enzyme-substrate complex (ES), which then subsequently breaks down to yield product (P) while regenerating the free enzyme [2] [1]. This mechanism can be represented schematically as:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P

The model incorporates several simplifying assumptions: that the reaction involves a single substrate, that the enzyme-substrate complex is in rapid equilibrium with free enzyme and substrate, and that the reverse reaction (product to substrate) is negligible during initial rate measurements [4]. The kinetic constants k₁ and k₋₁ represent the forward and reverse rate constants for the formation of the ES complex, while k₂ (often denoted kcat) represents the catalytic rate constant for the conversion of substrate to product [2].

The Michaelis-Menten Equation

Through steady-state kinetic analysis, where the concentration of the ES complex is assumed constant over time, the following fundamental equation describing initial reaction velocity (v) as a function of substrate concentration [S] can be derived:

v = (Vmax [S]) / (Km + [S])

In this equation, Vmax represents the maximum reaction velocity achieved when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate, while Km (the Michaelis constant) is defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity reaches half of Vmax [1] [4]. Physically, Km provides an inverse measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate—a lower Km value indicates higher affinity, as less substrate is required to achieve half-maximal velocity [4]. Vmax is directly proportional to total enzyme concentration ([E]₀), expressed as Vmax = kcat[E]₀, where kcat (the turnover number) represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time [1].

Key Kinetic Parameters and Their Interpretation

The parameters kcat, Km, and their ratio kcat/Km provide crucial information about enzyme function and efficiency:

Table 1: Fundamental Parameters in Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis Constant | Km | [S] at which v = Vmax/2 | Inverse measure of substrate affinity; lower Km indicates higher affinity |

| Catalytic Constant | kcat | Vmax / [E]₀ | Turnover number; molecules converted per active site per unit time |

| Specificity Constant | kcat/Km | -- | Measure of catalytic efficiency; combines binding and catalytic steps |

The parameter kcat/Km, often termed the specificity constant, provides a measure of an enzyme's catalytic efficiency by combining both binding (Km) and catalytic (kcat) steps into a single parameter [1]. This ratio becomes particularly important when comparing an enzyme's activity toward different substrates or when comparing the effectiveness of different enzymes catalyzing the same reaction [5]. At substrate concentrations much lower than Km ([S] << Km), the Michaelis-Menten equation reduces to v = (kcat/Km)[E]₀[S], indicating that the reaction rate depends linearly on both enzyme and substrate concentration, with kcat/Km serving as the apparent second-order rate constant [1].

Modern Research Context: Beyond Simple Model Systems

Kinetics in Complex Biological Environments

While the classic Michaelis-Menten model was derived for simplified systems with one enzyme and one substrate, contemporary research increasingly focuses on enzymatic behavior in complex environments where numerous substrates compete for the same enzyme. Recent studies have demonstrated that applying classical equations to complex systems without considering competitive binding of coexisting alternative substrates can lead to inaccurate conclusions [6]. In 2016, researchers addressed this challenge by developing and validating kinetic equations specifically for enzymatic reactions in complex systems, employing an iterative approach to model reactions where an enzyme acts on a library of competing substrates, such as in proteomic samples or total cell lysates [6]. This advancement has enabled more accurate determination of catalytic efficiencies in biologically relevant contexts.

Structural Basis of Enzyme Kinetics

Understanding the relationship between enzyme structure and kinetic parameters represents another frontier in modern enzymology. The spatial arrangements of amino acids in active sites fundamentally determine substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency [7]. For example, in serine proteases, the precise geometry of the catalytic triad (Ser, His, Asp) directly influences kinetic parameters [7]. To systematically investigate these structure-kinetic relationships, researchers have developed SKiD (Structure-oriented Kinetics Dataset), a comprehensive resource integrating kcat and Km values with three-dimensional structural data of enzyme-substrate complexes [7]. This integration enables researchers to correlate structural features with catalytic efficiency, supporting rational enzyme design and optimization for industrial and therapeutic applications.

Table 2: Representative Enzyme Kinetic Parameters [1]

| Enzyme | Km (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ |

| tRNA synthetase | 9.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 7.6 | 8.4 × 10³ |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ |

Enzyme Inhibition Models in Therapeutic Development

Fundamentals of Enzyme Inhibition

Enzyme inhibition analysis is essential in drug development, necessitating precise estimation of inhibition constants for predicting drug-drug interactions and therapeutic efficacy [8]. The three primary modes of reversible inhibition—competitive, uncompetitive, and mixed—are characterized by distinct mechanisms and kinetic signatures:

- Competitive inhibition: Inhibitor binds exclusively to the free enzyme (E), competing directly with the substrate. Increases apparent Km without affecting Vmax.

- Uncompetitive inhibition: Inhibitor binds only to the enzyme-substrate complex (ES). Decreases both apparent Km and Vmax.

- Mixed inhibition: Inhibitor can bind to both E and ES, but with different affinities. Affects both Km and Vmax values [8].

The initial velocity in the presence of a mixed inhibitor can be described by the equation:

v = (Vmax [S]) / [Km(1 + [I]/Kic) + S]

where Kic and Kiu represent the inhibition constants for binding to the free enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex, respectively [8]. The relative magnitude of these two inhibition constants determines the mechanistic classification of the inhibitor.

Advanced Concepts in Inhibition

Recent research has introduced sophisticated inhibition strategies, including differential inhibition, which targets enzymes capable of acting on multiple substrates selectively [9]. Differential inhibitors (DIs) represent a promising approach for enzymes like aldose reductase, which metabolizes both hydrophilic aldoses (implicated in diabetic complications) and hydrophobic aldehydes (involved in detoxification) [9]. By selectively inhibiting only one catalytic pathway, DIs offer enhanced specificity with reduced off-target effects. In 2025, researchers further advanced inhibition analysis with "50-BOA" (IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach), demonstrating that precise estimation of inhibition constants is possible using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC₅₀ value, substantially reducing experimental requirements while maintaining accuracy [8].

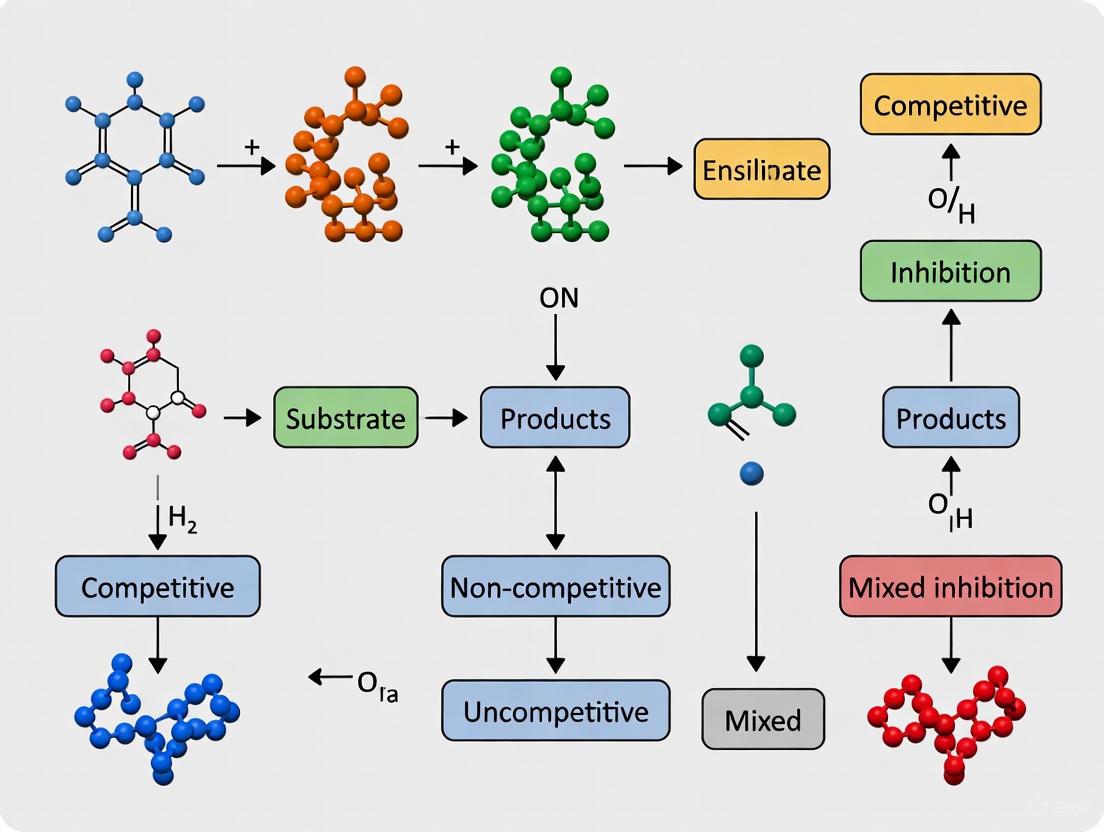

Diagram 1: Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms and Effects

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Advances

Standard Protocol for Determining Kinetic Parameters

The reliable determination of Michaelis-Menten parameters requires careful experimental design and execution. The following protocol outlines best practices for initial rate measurements:

Reaction Conditions: Conduct assays under optimal pH, temperature, and ionic strength conditions using appropriate buffer systems. Include any necessary cofactors or activators.

Initial Rate Measurements: Measure initial velocities (v₀) under conditions where product formation is linear with time and reverse reactions are negligible. Use enzyme concentrations that yield detectable product formation while maintaining [S] >> [E] conditions.

Substrate Concentration Range: Employ a substrate concentration range that brackets the Km value, typically from 0.2Km to 5Km. Include a minimum of 8-10 different substrate concentrations for reliable parameter estimation.

Data Collection: Measure initial rates in duplicate or triplicate for each substrate concentration. Include controls without enzyme and without substrate.

Parameter Estimation: Fit the Michaelis-Menten equation directly to the untransformed v versus [S] data using nonlinear regression algorithms. Avoid linear transformations like Lineweaver-Burk plots, which can distort error distribution and give misleading results [1].

Ultra-High-Throughput Kinetic Methodologies

Recent technological advances have dramatically increased the scale of kinetic measurements. Methodologies like DOMEK (mRNA-display-based one-shot measurement of enzymatic kinetics) enable quantitative determination of kcat/Km values for hundreds of thousands of substrates in parallel [10]. This approach combines mRNA display with next-generation sequencing to profile substrate specificity landscapes of promiscuous enzymes, such as post-translational modification enzymes, with unprecedented throughput. The experimental pipeline involves:

- Library Preparation: Generation of diverse peptide libraries via mRNA display (>10¹² unique sequences)

- Enzymatic Time Courses: Incubation of enzyme with peptide library across multiple time points

- Product Quantification: NGS-based measurement of substrate conversion yields

- Data Analysis: Fitting of progress curves to extract kcat/Km values for individual substrates [10]

Such high-throughput approaches are transforming enzymology from qualitative substrate identification to quantitative landscape mapping, enabling predictive models of enzyme specificity and mechanism.

Diagram 2: DOMEK High-Throughput Kinetic Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Enzymes | Catalytic component of reactions | Purified to homogeneity; concentration accurately determined via absorbance or activity assays |

| Synthetic Peptide Substrates | Enzyme substrates for specificity profiling | Custom-synthesized with >95% purity; concentrations verified by amino acid analysis |

| Cofactors (NAD(P)H, ATP, etc.) | Essential reaction components for many enzymes | Freshly prepared solutions; concentration stability verified spectrophotometrically |

| Coupled Assay Systems | Continuous monitoring of product formation | Include excess coupling enzymes; ensure non-rate-limiting conditions |

| mRNA Display Libraries | Ultra-high-throughput substrate screening | Library complexity >10¹² sequences; quality control via NGS [10] |

| Inhibitor Compounds | Mechanism and inhibition constant determination | High-purity compounds dissolved in appropriate solvents with vehicle controls |

Michaelis-Menten kinetics continues to provide an essential foundation for understanding enzyme catalysis more than a century after its initial formulation. While the basic principles remain unchanged, modern research has expanded this framework to address increasingly complex biological questions. Current frontiers include the development of ultra-high-throughput screening methods like DOMEK that can simultaneously quantify kinetic parameters for hundreds of thousands of substrates [10], the integration of structural data with kinetic parameters through resources like SKiD [7], and the refinement of inhibition analysis techniques that reduce experimental burden while improving precision [8]. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will further enhance our ability to engineer enzymes with tailored properties, design more specific therapeutic inhibitors, and predict metabolic behaviors in complex biological systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of both the fundamental principles and contemporary advancements in enzyme kinetics remains indispensable for innovation in biochemistry, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical sciences.

Enzyme inhibition analysis is a cornerstone of enzymology and drug discovery, providing critical insights into the regulation of biochemical pathways and the mechanism of action of therapeutic compounds. Reversible inhibition, characterized by non-covalent interactions between the inhibitor and enzyme, allows for equilibrium between the enzyme and inhibitory drug [11] [12]. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for predicting drug interactions, designing targeted therapies, and elucidating metabolic control systems in living organisms. The three primary models of reversible inhibition—competitive, non-competitive, and uncompetitive—are distinguished by their specific binding mechanisms and resultant effects on enzyme kinetic parameters [13]. These inhibition patterns not only reveal the nature of enzyme-inhibitor interactions but also have profound implications for drug efficacy and physiological function.

In drug development, enzyme inhibitors constitute a significant proportion of therapeutic agents, as many drugs function by specifically inhibiting enzymes involved in disease processes [13]. The screening and characterization of these inhibitors through mechanism of action (MOA) studies provide the foundation for structure-activity relationship (SAR) analyses, which guide the optimization of drug candidates for enhanced potency, selectivity, and pharmacological properties [13]. Furthermore, the type of reversible inhibition displayed by a compound determines its behavior under physiological conditions, particularly in the presence of varying substrate concentrations, which directly impacts its therapeutic potential and clinical management strategies [8].

Competitive Inhibition

Mechanism and Binding Characteristics

Competitive inhibition occurs when an inhibitor competes with the substrate for binding to the active site of the enzyme [14]. The inhibitor is typically a structural analog of the substrate, resembling the natural substrate closely enough to bind to the active site but differing in that it cannot undergo catalysis [11] [15]. This binding results in the formation of an enzyme-inhibitor (EI) complex that is catalytically inactive. The fundamental characteristic of competitive inhibition is that the inhibitor binds exclusively to the free enzyme (E) and cannot bind to the enzyme-substrate (ES) complex, making the binding of substrate and inhibitor mutually exclusive events [13] [14].

The reversibility of competitive inhibition means that the inhibitor can dissociate from the enzyme, allowing substrate binding to occur. Consequently, the inhibitory effect can be overcome by increasing the concentration of substrate, as the higher substrate concentration effectively outcompetes the inhibitor for binding to the active site [11] [14]. This property has significant implications for drug design and therapeutic applications, as the efficacy of competitive inhibitors can be influenced by the endogenous concentration of the natural substrate in physiological conditions.

Kinetic Parameters and Graphical Analysis

Competitive inhibition produces distinctive effects on the Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters of an enzyme. The presence of a competitive inhibitor increases the apparent Michaelis constant (Kₘ) while leaving the maximal reaction velocity (Vₘₐₓ) unchanged [13] [14]. The increase in apparent Kₘ occurs because a higher substrate concentration is required to achieve half-maximal velocity in the presence of the inhibitor, reflecting reduced apparent affinity of the enzyme for its substrate [11].

The Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal plot provides a characteristic pattern for competitive inhibition. The plots show a series of lines that intersect on the y-axis, indicating that Vₘₐₓ remains constant while the slope (Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ) and x-intercept (-1/Kₘ) change with increasing inhibitor concentration [16] [14]. The inhibitor constant (Kᵢ), which represents the dissociation constant of the enzyme-inhibitor complex, can be determined from secondary plots of the apparent Kₘ or the slopes of the Lineweaver-Burk lines versus inhibitor concentration [13].

The velocity equation for an enzyme reaction in the presence of a competitive inhibitor is modified as follows:

v₀ = (Vₘₐₓ × [S₀]) / (Kₘ × (1 + [I₀]/Kᵢ) + [S₀])

Research and Clinical Applications

Competitive inhibitors have significant therapeutic applications, with many drugs functioning through this mechanism. Methotrexate, an antineoplastic agent, is a classic example of a competitive inhibitor that structurally resembles folic acid and competitively inhibits dihydrofolate reductase, blocking nucleotide synthesis and cell division in rapidly dividing cancer cells [11] [14]. Similarly, the HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir competes with the viral protein substrate for binding to the active site of the HIV protease enzyme [14].

In clinical toxicology, competitive inhibition provides life-saving interventions, as demonstrated in methanol poisoning treatment. Methanol is metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase to toxic formaldehyde, and treatment involves administering either ethanol or fomepizole, which compete with methanol for the enzyme's active site, preventing the formation of toxic metabolites [14]. Penicillin represents another example, acting as a competitive inhibitor that blocks the active site of bacterial enzymes involved in cell wall synthesis [15].

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters for Competitive Inhibition

| Parameter | Effect of Competitive Inhibitor | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Vₘₐₓ | Unchanged | At infinite substrate concentration, inhibitor is completely outcompeted |

| Kₘ | Increases | Higher substrate concentration required to achieve half-maximal velocity |

| Kᵢ | Dissociation constant for EI complex | Measure of inhibitor affinity for enzyme |

| Lineweaver-Burk Pattern | Lines intersecting on y-axis | Confirms unchanged Vₘₐₓ with increasing Kₘ |

Figure 1: Competitive Inhibition Mechanism - The inhibitor (I) competes with substrate (S) for binding to the active site of the enzyme (E), forming an enzyme-inhibitor complex (EI) that cannot proceed to product formation.

Non-competitive Inhibition

Mechanism and Binding Characteristics

Non-competitive inhibition is characterized by an inhibitor that binds to an allosteric site on the enzyme, distinct from the active site where substrate binding occurs [16] [12]. Unlike competitive inhibitors, non-competitive inhibitors can bind to both the free enzyme (E) and the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) with equal affinity, forming either an enzyme-inhibitor (EI) complex or an enzyme-substrate-inhibitor (ESI) complex [13] [16]. The binding of the non-competitive inhibitor induces conformational changes in the enzyme structure that diminish catalytic activity without affecting substrate binding [16].

The mechanism of non-competitive inhibition does not involve competition between substrate and inhibitor for the same binding site, which means that increasing substrate concentration cannot overcome the inhibition [12]. The ESI complex is typically catalytically inactive or has significantly reduced activity, preventing product formation even when substrate is bound to the enzyme. This allosteric regulation represents a fundamental mechanism for controlling metabolic pathways in physiological systems [16].

Kinetic Parameters and Graphical Analysis

In non-competitive inhibition, the apparent Vₘₐₓ is decreased while the Kₘ value remains unchanged [16] [17]. The reduction in Vₘₐₓ occurs because the inhibitor effectively reduces the concentration of functional enzyme, regardless of substrate concentration. The unchanged Kₘ indicates that the enzyme's affinity for its substrate is not affected, as the substrate can still bind to the enzyme with the same affinity even when the inhibitor is bound at the allosteric site [16].

The Lineweaver-Burk plot for non-competitive inhibition shows a series of lines that intersect on the x-axis, indicating constant Kₘ with decreasing Vₘₐₓ as inhibitor concentration increases [16]. The inhibitor constant Kᵢ can be determined from secondary plots of 1/Vₘₐₓ or the slopes of the Lineweaver-Burk plots versus inhibitor concentration [13]. For simple linear non-competitive inhibition, Kᵢ represents the inhibitor concentration that halves the value of Vₘₐₓ [13].

The velocity equation for non-competitive inhibition is expressed as:

v₀ = (Vₘₐₓ × [S₀]) / ((Kₘ + [S₀]) × (1 + [I₀]/Kᵢ))

Research and Clinical Applications

Non-competitive inhibition plays crucial roles in metabolic regulation and toxicology. In metabolic pathways, feedback inhibition often operates through non-competitive mechanisms, where end products of pathways inhibit earlier enzymes to prevent overproduction [16]. For example, glucose-6-phosphate acts as a non-competitive inhibitor of hexokinase in the brain, shutting down glucose metabolism when sufficient product has accumulated [16]. Similarly, ATP and alanine function as non-competitive inhibitors of pyruvate kinase, the final enzyme in glycolysis, providing regulatory control of energy production [16].

In clinical contexts, cyanide poisoning represents a dramatic example of non-competitive inhibition, where cyanide binds to cytochrome c oxidase in the electron transport chain, disrupting cellular respiration and ATP production [16]. Heavy metals such as mercury, cadmium, and lead also exhibit toxicity through non-competitive inhibition of various essential enzymes [16]. From a therapeutic perspective, research continues to explore non-competitive inhibitors for conditions like type 2 diabetes, where compounds such as Rosha grass components act as non-competitive inhibitors of intestinal alpha-glucosidase, helping to manage postprandial blood glucose levels [16].

Table 2: Kinetic Parameters for Non-competitive Inhibition

| Parameter | Effect of Non-competitive Inhibitor | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Vₘₐₓ | Decreased | Functional enzyme concentration reduced |

| Kₘ | Unchanged | Substrate binding affinity unaffected |

| Kᵢ | Dissociation constant for EI and ESI complexes | Measure of inhibitor affinity |

| Lineweaver-Burk Pattern | Lines intersecting on x-axis | Confirms unchanged Kₘ with decreasing Vₘₐₓ |

Figure 2: Non-competitive Inhibition Mechanism - The inhibitor (I) binds to an allosteric site on both the free enzyme (E) and the enzyme-substrate complex (ES), forming inactive EI and ESI complexes.

Uncompetitive Inhibition

Mechanism and Binding Characteristics

Uncompetitive inhibition represents a less common but mechanistically distinct form of enzyme inhibition where the inhibitor binds exclusively to the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) rather than to the free enzyme [13] [18]. This binding results in the formation of an enzyme-substrate-inhibitor (ESI) complex that is catalytically inactive or has significantly reduced activity. A key characteristic of uncompetitive inhibition is that the inhibitor binding site is typically not available on the free enzyme but becomes exposed only after substrate binding induces a conformational change in the enzyme structure [18].

This sequential binding mechanism means that uncompetitive inhibitors do not compete with substrates for binding, and increasing substrate concentration does not reverse the inhibition but rather enhances it [13] [18]. This paradoxical behavior occurs because higher substrate concentrations lead to more ES complex formation, which in turn provides more target for the uncompetitive inhibitor to bind. The unique properties of uncompetitive inhibition make it particularly significant in physiological regulation and drug design, especially for multi-substrate enzyme systems [18].

Kinetic Parameters and Graphical Analysis

In uncompetitive inhibition, both Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ are decreased by the same factor (1 + [I]/Kᵢ) [13] [18]. The reduction in Vₘₐₓ occurs because the formation of the ESI complex removes active enzyme from the catalytic cycle. The decrease in Kₘ appears counterintuitive but results from the inhibitor binding to and stabilizing the ES complex, effectively increasing the enzyme's apparent affinity for the substrate by reducing the dissociation of substrate from the complex [18].

The Lineweaver-Burk plot for uncompetitive inhibition shows a series of parallel lines, with both the y-intercept (1/Vₘₐₓ) and x-intercept (-1/Kₘ) increasing with higher inhibitor concentrations while the slope (Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ) remains unchanged [18]. The inhibitor constant Kᵢ (often denoted as Kᵢᵢ to specify intercept effects) represents the dissociation constant for the ESI complex and can be determined from secondary plots of the apparent Vₘₐₓ or 1/Vₘₐₓ versus inhibitor concentration [13].

The velocity equation for uncompetitive inhibition is expressed as:

v₀ = (Vₘₐₓ × [S₀]) / (Kₘ + [S₀] × (1 + [I₀]/Kᵢ))

Research and Clinical Applications

Uncompetitive inhibition, while relatively rare compared to other forms of inhibition, offers unique advantages in therapeutic applications. Because uncompetitive inhibitors bind only to the enzyme-substrate complex, they selectively target actively catalyzing enzymes, potentially reducing off-target effects [18]. This specificity makes them particularly attractive for drug development against enzymes that exist in multiple states or conformations.

In clinical contexts, the management of uncompetitive inhibition presents distinct challenges. Unlike competitive inhibition where dose adjustments can help mitigate risks, therapeutic interventions are less effective for uncompetitive inhibitors, making clinical management more complicated [8]. This underscores the importance of identifying inhibition mechanisms during drug development to anticipate potential clinical behaviors and design appropriate dosing strategies.

Uncompetitive inhibition is more commonly observed in multi-reactant enzyme systems than single-substrate reactions, making it particularly relevant for complex metabolic pathways and signaling cascades [18]. The study of uncompetitive inhibition continues to provide insights into enzyme mechanisms and opportunities for designing highly specific therapeutic agents with reduced side-effect profiles.

Table 3: Kinetic Parameters for Uncompetitive Inhibition

| Parameter | Effect of Uncompetitive Inhibitor | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Vₘₐₓ | Decreased | ES complex diverted to inactive ESI complex |

| Kₘ | Decreased | ES complex stabilized by inhibitor binding |

| Kᵢ | Dissociation constant for ESI complex | Measure of inhibitor affinity for ES complex |

| Lineweaver-Burk Pattern | Parallel lines | Proportional decrease in both Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ |

Figure 3: Uncompetitive Inhibition Mechanism - The inhibitor (I) binds exclusively to the enzyme-substrate complex (ES), forming an inactive ESI complex without binding to free enzyme.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Classical Steady-State Inhibition Analysis

The classical approach to enzyme inhibition analysis involves measuring initial reaction velocities under steady-state conditions across a range of substrate and inhibitor concentrations [13]. The fundamental protocol begins with determining enzyme activity in the absence of inhibitor to establish baseline kinetic parameters (Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ). Subsequently, reactions are conducted with varying concentrations of inhibitor, typically spanning several orders of magnitude around the expected inhibition constant [13]. For each inhibitor concentration, initial velocities are measured at multiple substrate concentrations, usually ranging from 0.2×Kₘ to 5×Kₘ to adequately characterize the inhibition pattern [13] [8].

Data collection follows a systematic matrix design where each combination of substrate and inhibitor concentrations is tested in replicate to ensure statistical reliability. The reaction conditions—including pH, temperature, ionic strength, and cofactor concentrations—must be rigorously controlled and optimized for the specific enzyme system under investigation [13]. Continuous assays employing spectrophotometric, fluorometric, or radiometric detection methods are preferred when possible, as they provide more data points for accurate velocity determination compared to endpoint assays [13].

IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA)

Recent advancements in inhibition analysis have introduced more efficient experimental designs that reduce resource requirements while maintaining precision. The IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) represents a significant innovation that enables precise estimation of inhibition constants using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) [8]. This method substantially reduces the number of required experiments by more than 75% compared to conventional approaches while ensuring accuracy and precision [8].

The 50-BOA protocol begins with prior estimation of IC₅₀ from percentage control activity data across various inhibitor concentrations at a single substrate concentration, typically equal to Kₘ [8]. Subsequently, comprehensive initial velocity measurements are performed using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the determined IC₅₀ value across the full range of substrate concentrations [8]. By incorporating the fundamental relationship between IC₅₀ and inhibition constants into the fitting process, this approach achieves comparable precision to traditional methods with significantly reduced experimental burden [8].

The mathematical foundation of 50-BOA relies on the error landscape analysis of inhibition constant estimations, which revealed that data obtained with low inhibitor concentrations provide minimal information for constant estimation, while high inhibitor concentrations dramatically reduce estimation error [8]. This approach is particularly valuable in drug discovery settings where high-throughput screening of multiple compounds is necessary, as it enables rapid characterization of inhibition mechanisms and constants without compromising data quality.

Data Analysis and Validation

Analysis of inhibition data typically begins with visualization using Lineweaver-Burk plots to identify the inhibition pattern, followed by nonlinear regression fitting to the appropriate velocity equation to determine kinetic parameters and inhibition constants [13]. Statistical validation includes assessment of goodness-of-fit metrics, residual analysis, and determination of confidence intervals for estimated parameters [13] [8]. For mixed inhibition models involving two inhibition constants, additional validation through global fitting across multiple inhibitor concentrations is essential to ensure parameter identifiability and prevent false reporting of inhibition types [8].

Secondary plots provide crucial validation of inhibition constants and mechanisms. For competitive inhibition, plots of apparent Kₘ versus inhibitor concentration should yield linear relationships with x-intercepts of -Kᵢ [13]. For non-competitive inhibition, plots of 1/Vₘₐₓ versus inhibitor concentration provide Kᵢ values from x-intercepts [13]. Dixon plots (1/v versus [I]) represent an alternative method for determining Kᵢ values, with all inhibition types yielding linear relationships that intersect at -Kᵢ [13].

Table 4: Experimental Design for Comprehensive Inhibition Analysis

| Experimental Condition | Traditional Approach | 50-BOA Approach | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Concentrations | 0.2×Kₘ, Kₘ, 5×Kₘ | Full range (0.2×Kₘ to 5×Kₘ) | Characterize substrate dependence |

| Inhibitor Concentrations | 0, ⅓×IC₅₀, IC₅₀, 3×IC₅₀ | Single concentration > IC₅₀ | Determine inhibitor potency |

| IC₅₀ Determination | Required for design | Required for design | Establish inhibitor potency range |

| Data Points Required | 12-16 combinations | 3-5 substrate concentrations | Balance precision and efficiency |

Figure 4: Experimental Workflow for Inhibition Studies - Comparison of traditional and 50-BOA approaches for enzyme inhibition analysis, highlighting significant reduction in experimental requirements with the optimized method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful investigation of reversible inhibition mechanisms requires carefully selected reagents and specialized materials designed to maintain enzyme stability, ensure measurement precision, and enable accurate detection of reaction products. The following essential components represent the core toolkit for researchers conducting enzyme inhibition studies.

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Inhibition Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | High purity (>95%), known concentration | Primary target for inhibition studies; must have well-characterized specific activity |

| Natural Substrate | High purity, structurally characterized | Native reactant for establishing baseline kinetics and inhibition patterns |

| Inhibitor Compounds | >95% purity, solubilized in appropriate solvent | Test compounds for mechanism elucidation; require precise concentration verification |

| Assay Buffer System | pH-optimized, appropriate ionic strength | Maintains enzyme stability and activity; prevents pH artifacts in inhibition measurements |

| Cofactors/Prosthetic Groups | Enzyme-specific (NAD/H, metal ions, etc.) | Essential for enzymes requiring cofactors; concentration must be saturating |

| Detection Reagents | Spectrophotometric/fluorometric substrates | Enable monitoring of reaction progress; must have appropriate sensitivity and dynamic range |

| Positive Control Inhibitors | Well-characterized inhibition mechanism | Validation of experimental system and comparison of inhibitor potency |

| Stopping Reagents | Acid, base, or specific quenchers | Terminate reactions at precise time points for endpoint assays |

The selection of appropriate buffer systems deserves particular emphasis, as pH can significantly influence enzyme activity and inhibitor binding [13]. Buffers should be chosen based on their pKₐ values relative to the optimal pH for enzyme activity and their lack of specific ion effects that might alter enzyme conformation or inhibitor interactions. For metal-dependent enzymes, chelating agents may be incorporated into control experiments to verify metal requirement, but must be excluded from main inhibition studies to prevent confounding effects [13].

Detection methods must be optimized for the specific enzyme system under investigation. Continuous spectrophotometric or fluorometric assays are preferred when possible, as they provide multiple data points from single reactions and allow direct verification of linear initial velocity conditions [13]. For endpoint assays, the linear range of the assay must be thoroughly characterized, and reaction times adjusted to ensure that substrate depletion remains below 10% to maintain steady-state conditions [13]. Recent advancements in detection technologies, including coupled enzyme systems and high-throughput compatible methods, have expanded the toolbox available for comprehensive inhibition studies.

Enzyme kinetics provides a fundamental framework for understanding catalytic efficiency and enzyme-substrate interactions in biochemical systems. The parameters ( KM ), ( V{max} ), and ( k_{cat} ) offer critical insights into enzyme function, enabling researchers to quantify catalytic proficiency, substrate affinity, and turnover capacity. Within drug development and metabolic engineering, these parameters inform inhibitor design, pathway regulation, and therapeutic targeting. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundation, experimental determination, and biochemical significance of these core kinetic parameters, contextualized within contemporary enzyme research and industrial applications.

Enzyme kinetics is the study of reaction rates catalyzed by enzymes and the conditions affecting these rates [19]. This discipline reveals catalytic mechanisms, regulatory control points, and potential therapeutic intervention strategies [19]. The quantitative analysis of enzyme behavior allows researchers to predict metabolic flux, identify rate-limiting steps in biochemical pathways, and design effective inhibitors for pharmaceutical applications [20].

The Michaelis-Menten model, first introduced in 1913, remains the cornerstone for understanding single-substrate enzyme kinetics [21] [22]. This model describes how reaction velocity varies with substrate concentration, characterized by a hyperbolic relationship that approaches a maximum velocity (( V_{max} )) as substrate concentration increases [23] [24]. The model relies on several key assumptions: that the reaction occurs under steady-state conditions, enzyme concentration remains constant, and only initial rates are measured before significant product accumulation occurs [19] [25].

Fundamental Kinetic Parameters

The Michaelis Constant (( K_M ))

The Michaelis constant (( KM )) is defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of ( V{max} ) [24] [22]. Mathematically, ( KM ) is expressed as ( KM = \frac{k{-1} + k{cat}}{k1} ), where ( k{-1} ) and ( k1 ) are the rate constants for the dissociation and formation of the enzyme-substrate complex, respectively, and ( k{cat} ) is the catalytic rate constant [19]. In the specific case where ( k{cat} ) is much smaller than ( k{-1} ), ( KM ) approximates the dissociation constant (( KD )) of the enzyme-substrate complex, thus providing a direct measure of substrate affinity [19]. A lower ( K_M ) value indicates higher enzyme-substrate affinity, meaning the enzyme can achieve half-maximal velocity at lower substrate concentrations [26] [22].

Maximum Velocity (( V_{max} ))

( V{max} ) represents the maximum reaction rate achieved when an enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [23] [24]. At this point, all enzyme active sites are occupied, and the reaction rate depends solely on the intrinsic turnover capacity of the enzyme [19]. ( V{max} ) is directly proportional to enzyme concentration, as expressed by the relationship ( V{max} = k{cat} \cdot [E]{tot} ), where ( [E]{tot} ) is the total enzyme concentration [19]. This proportional relationship distinguishes ( V{max} ) from ( KM ), the latter being independent of enzyme concentration [24].

Turnover Number (( k_{cat} ))

The turnover number (( k{cat} )), also known as the turnover rate or turnover frequency, quantifies the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per unit time [24] [27]. Calculated as ( k{cat} = \frac{V{max}}{[E]{tot}} ), this parameter provides a measure of catalytic efficiency independent of enzyme concentration [24]. Turnover numbers vary dramatically between enzymes, from approximately 1 per second for tyrosinase to over 600,000 per second for carbonic anhydrase (Table 1) [27]. This remarkable variation reflects evolutionary adaptation to specific physiological demands and substrate characteristics.

Catalytic Efficiency (( k{cat}/KM ))

The ratio ( k{cat}/KM ) represents the catalytic efficiency of an enzyme, combining both substrate binding affinity (( KM )) and catalytic rate (( k{cat} )) into a single parameter [26]. This ratio has dimensions of a second-order rate constant (M⁻¹s⁻¹) and describes the enzyme's effectiveness at low substrate concentrations [26]. A higher ( k{cat}/KM ) value indicates greater catalytic proficiency, with some enzymes approaching the diffusion-controlled limit of approximately 10⁸ to 10⁹ M⁻¹s⁻¹ [26].

Table 1: Representative Turnover Numbers and Kinetic Parameters for Common Enzymes

| Enzyme | ( k_{cat} ) (s⁻¹) | ( K_M ) (mM) | ( k{cat}/KM ) (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Catalytic Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonic anhydrase | 600,000 [27] | ~26 [27] | ~2.3×10⁷ | Extremely high |

| Catalase | 93,000 [27] | - | - | Very high |

| β-Galactosidase | 200 [27] | - | - | Moderate |

| Chymotrypsin | 100 [27] | - | - | Moderate |

| Tyrosinase | 1 [27] | - | - | Low |

Experimental Determination of Kinetic Parameters

Initial Rate Measurements and Assay Conditions

Accurate determination of kinetic parameters requires careful measurement of initial reaction rates under conditions where substrate depletion, product inhibition, and enzyme instability are minimized [28] [19]. Enzyme assays should be conducted during the steady-state phase, typically the first few percent of the reaction, where the concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex remains relatively constant [23] [19].

Assay conditions must be carefully controlled, as kinetic parameters are dependent on temperature, pH, ionic strength, and buffer composition [28]. Researchers should ideally use conditions that reflect the enzyme's physiological environment, though this is not always practiced in literature reports [28]. Common pitfalls include using non-physiological substrates for easier detection, inappropriate pH values that shift reaction equilibria, and variable temperatures that complicate comparisons between studies [28].

Figure 1: Workflow for determining enzyme kinetic parameters, highlighting critical experimental considerations.

Data Analysis and Linearization Methods

The Michaelis-Menten equation, ( v0 = \frac{V{max}[S]}{KM + [S]} ), describes the hyperbolic relationship between initial velocity (( v0 )) and substrate concentration ([S]) [19]. While nonlinear regression of the direct plot provides the most accurate parameter estimates, linear transformations such as the Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/v₀ vs. 1/[S]) offer visual insights into enzyme inhibition mechanisms [23]. The Lineweaver-Burk plot yields a straight line with a y-intercept of 1/Vmax and an x-intercept of -1/KM [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function & Importance | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | Catalytic entity under investigation; source and purity critical | Specify organism, tissue, isoenzyme; confirm purity and activity; note potential commercial variations [28] |

| Natural Substrate | Physiological reactant for the enzyme | Preferred for relevance; may present detection challenges [28] |

| Analog Substrate | Alternative reactant with more easily detectable products | Enables high-throughput screening; verify kinetic behavior matches natural substrate [28] |

| Appropriate Buffer | Maintains optimal pH and ionic environment | Consider chelating properties, specific ion effects, and physiological relevance [28] |

| Cofactors/Coenzymes | Essential non-protein components for many enzymes | Required for holenzyme formation; concentration optimization needed [27] |

| Detection System | Quantifies product formation or substrate depletion | Spectrophotometric, radiometric, or coupled assays; ensure linear range [19] |

Biochemical Interpretation and Significance

Physiological Relevance of Kinetic Parameters

In metabolic pathways, enzymes with high catalytic efficiency (( k{cat}/KM )) often operate near diffusion-controlled limits, while those with lower efficiency may serve as regulatory points [20]. The ( KM ) value typically approximates the physiological substrate concentration, allowing enzymes to respond sensitively to changes in metabolite levels [19]. This relationship enables efficient metabolic regulation, as small fluctuations in substrate concentration around the ( KM ) value produce significant changes in reaction rate [19].

Enzyme kinetics also provides crucial insights for understanding metabolic diseases. Abnormal levels of specific metabolites may indicate alterations in the rate-limiting steps of pathways, potentially due to genetic deficiencies, environmental toxins, or pathological conditions [20]. Kinetic analysis can identify which enzyme in a patient's pathway has become newly rate-limiting, informing potential therapeutic strategies [20].

Enzyme Inhibition and Drug Design

Kinetic parameters are essential for characterizing enzyme inhibition mechanisms, which form the basis for many pharmaceutical compounds [22]. Competitive inhibitors increase the apparent ( KM ) without affecting ( V{max} ) by competing with the substrate for the active site [22]. Uncompetitive inhibitors bind exclusively to the enzyme-substrate complex, decreasing both apparent ( KM ) and ( V{max} ) [21]. Non-competitive inhibitors bind to both free enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex, reducing ( V{max} ) while leaving ( KM ) unchanged [21] [22].

Figure 2: Enzyme inhibition mechanisms showing competitive (EI), uncompetitive (ESI), and mixed inhibition pathways.

Advanced Considerations in Enzyme Kinetics

Multi-Substrate Reactions

Many enzymes catalyze reactions involving two or more substrates, requiring more complex kinetic mechanisms [21] [19]. Sequential mechanisms require all substrates to bind before any products are released, with ordered mechanisms specifying a mandatory binding sequence and random mechanisms allowing flexible substrate association [21]. Ping-pong mechanisms involve covalent modification of the enzyme and release of one product before all substrates have bound, characteristic of transaminases and phosphotransferases [21] [19].

Cooperativity and Allosteric Regulation

Enzymes with multiple subunits often display cooperativity, where substrate binding to one active site influences substrate affinity at subsequent sites [25]. Positive cooperativity results in a sigmoidal velocity vs. substrate concentration curve, with the Hill equation modifying the Michaelis-Menten relationship to accommodate this behavior [21]. Allosteric effectors modulate enzyme activity by binding at regulatory sites distinct from the active site, providing crucial metabolic feedback control [28].

The reliability of kinetic parameters depends heavily on experimental conditions and reporting standards [28]. Researchers should critically evaluate literature values for factors such as appropriate assay conditions, initial rate measurements, and physiological relevance [28]. Databases such as BRENDA, SABIO-RK, and STRENDA provide curated kinetic parameters with source references, with STRENDA establishing reporting standards to improve data reliability [28].

The kinetic parameters ( KM ), ( V{max} ), and ( k_{cat} ) provide fundamental insights into enzyme function that extend from basic biochemical understanding to applied pharmaceutical development. Proper determination and interpretation of these parameters requires careful experimental design, appropriate assay conditions, and critical evaluation of results within physiological context. As enzyme kinetics continues to evolve with improved measurement technologies and standardized reporting, these parameters remain essential for elucidating catalytic mechanisms, designing therapeutic interventions, and understanding metabolic regulation in health and disease.

The drug-target residence time model represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, moving beyond traditional equilibrium affinity measurements to incorporate kinetic parameters that often better predict in vivo efficacy. While classical drug affinity parameters (Kd, Ki, IC50) describe binding potency at equilibrium, drug-target residence time (tR), defined as the reciprocal of the dissociation rate constant (1/koff), provides crucial information about the duration of the drug-target complex [29] [30]. This concept has gained significant attention in recent years as researchers recognize that biological systems are dynamic, with drugs entering and leaving circulation through absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) processes [31]. The residence time concept acknowledges that a drug is only pharmacologically active when bound to its target, suggesting that prolonged residence time could extend therapeutic effects even after free drug concentrations have declined below effective levels [31].

The fundamental relationship between binding kinetics and residence time can be described through the simple binding mechanism:

Where R represents the receptor, L the ligand (drug), RL the drug-receptor complex, kon the association rate constant, and koff the dissociation rate constant [30]. The equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) is defined as koff/kon, while the drug-target residence time (tR) equals 1/koff [30]. This review explores the theoretical foundation, experimental evidence, methodological approaches, and ongoing controversies surrounding the drug-target residence time concept, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for applying these principles in drug discovery.

Theoretical Foundation and Kinetic Principles

Fundamental Kinetic Equations

The mathematical foundation of drug-target residence time begins with the basic equations governing molecular interactions. For the simple one-step binding mechanism described above, the dissociation rate constant (koff) directly determines the stability of the drug-target complex. The probability that a drug-target complex remains intact over time follows an exponential decay function:

Where [RL]t represents the concentration of the drug-target complex at time t, and [RL]0 represents the initial complex concentration [30]. The half-life (t1/2) of the complex is calculated as ln(2)/koff, which approximately equals 0.693/koff [31]. This relationship demonstrates that compounds with slower dissociation rates form more persistent complexes with their targets, potentially leading to longer-lasting pharmacological effects.

The crucial relationship between residence time and overall drug effect emerges when considering the dynamic nature of in vivo systems. Unlike in vitro closed systems where equilibrium measurements predominate, in vivo environments represent open systems where drugs are subject to continuous elimination and distribution [31]. The theoretical benefit of long residence time becomes most apparent when the dissociation rate (koff) is slower than the rate of pharmacokinetic elimination (kelim), potentially allowing target engagement to persist even after systemic drug concentrations have become negligible [29].

Comparative Analysis of Binding Kinetics Parameters

Table 1: Key Parameters in Drug-Target Binding Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Relationship to Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate Constant | kon | Rate of complex formation (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Determines how quickly drug reaches target |

| Dissociation Rate Constant | koff | Rate of complex breakdown (s⁻¹) | Inversely related to duration of effect |

| Equilibrium Dissociation Constant | Kd | koff/kon (M) | Measures binding affinity at equilibrium |

| Drug-Target Residence Time | tR | 1/koff (time) | Measures duration of target engagement |

| Inhibition Constant | Ki | Functional analog of Kd for enzymes | Classical measure of inhibitor potency |

| IC50 | IC50 | Concentration for 50% inhibition | Functional potency under specific conditions |

Experimental Evidence and Validation Studies

In Vivo Displacement Assay for Target Occupancy

A groundbreaking approach to validating the residence time concept came from the development of an in vivo displacement assay using soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) as a model system [31]. This innovative methodology enabled researchers to directly monitor drug-target engagement in living organisms, addressing a critical gap in kinetic pharmacology. The experimental workflow follows these key stages:

Loading Phase: Administration of a loading compound (Inhibitor A) at concentrations sufficient to achieve near-complete target occupancy (typically ≥100× Ki) [31]

Clearance Phase: A post-dosing period allowing for systemic clearance of unbound drug molecules through metabolism and excretion

Displacement Phase: Administration of a high-dose displacement compound (Inhibitor B) that competes for the same binding site

Detection Phase: Measurement of returning blood levels of the original compound as it is displaced from its target [31]

This methodology demonstrated that the sEH inhibitor TPPU (Ki = 2.5 nM, tR = 28.6 minutes) remained bound to its target in vivo long after free drug concentrations had declined to negligible levels [31]. When the displacement compound TCPU was administered seven days after TPPU dosing, a distinct secondary peak of TPPU appeared in blood measurements, confirming that a substantial amount of drug remained target-bound despite undetectable free circulating concentrations [31]. This provided direct experimental evidence that drug-target residence time significantly influences the duration of target occupancy in vivo.

Relationship Between Residence Time and Pharmacokinetics

The sEH inhibitor study revealed an additional crucial dimension of residence time effects—the impact on drug metabolism rates. Researchers observed that compounds with longer residence times were protected from metabolic degradation, effectively extending their functional half-lives [31]. This phenomenon creates a self-reinforcing cycle where prolonged target binding reduces exposure to metabolic enzymes, which in turn further extends the duration of action.

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for sEH Inhibitors in Residence Time Study

| Parameter | TPPU | TCPU |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibition Constant (Ki) | 2.5 nM | 0.92 nM |

| Residence Time (tR) | 28.6 min | 23.8 min |

| Dissociation Half-Life (t1/2) | 19.8 min | 16.5 min |

| PK Elimination Half-Life | 13.0 h | Not specified |

| Cmax at Test Dose | 456 nM | 4114 nM |

| AUC | 8813 nM·h | 56254 nM·h |

These findings fundamentally challenge the traditional separation between pharmacokinetics (what the body does to the drug) and pharmacodynamics (what the drug does to the body) [31]. Instead, they suggest a complex interplay where binding kinetics influence metabolic fate, which in turn modulates therapeutic effects. This relationship may explain why residence time often correlates better with in vivo efficacy than traditional affinity measurements.

Methodological Advances and Experimental Protocols

Enzyme Inhibition Analysis and the 50-BOA Method

Recent methodological advances have revolutionized the estimation of inhibition parameters, including those relevant to residence time calculations. The novel IC50-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) enables precise estimation of inhibition constants using dramatically reduced experimental data [8]. Traditional methods require multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations, but the 50-BOA demonstrates that accurate, precise estimation can be achieved with a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50 value [8].

The 50-BOA protocol follows these essential steps:

IC50 Determination: Estimate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration using a single substrate concentration (typically at KM) across various inhibitor concentrations [8]

Single-Concentration Design: Measure initial reaction velocities at three substrate concentrations (0.2KM, KM, and 5KM) with a single inhibitor concentration > IC50 [8]

Model Fitting: Fit the mixed inhibition model to the data using the relationship between IC50 and inhibition constants to constrain parameter estimation [8]

This approach reduces the required experimental data by >75% while improving precision and accuracy compared to traditional methods [8]. The 50-BOA method is particularly valuable for early drug discovery when compound availability is limited and rapid screening of multiple candidates is essential.

Experimental Workflow for Residence Time Determination

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for determining drug-target residence time and its relationship to in vivo efficacy:

Critical Perspectives and Controversies

Despite encouraging experimental evidence, the drug-target residence time concept faces substantial theoretical and practical challenges. A significant criticism concerns the mathematical foundation of the claim that prolonged residence time can cause pharmacodynamic effects to outlast pharmacokinetic exposure [29] [30]. Careful analysis reveals that for this prolongation to occur, the binding dissociation rate must be slower than the pharmacokinetic elimination rate [29]. However, data from numerous drugs and drug candidates show the opposite pattern—elimination rates are typically slower than dissociation rates [29]. This discrepancy severely limits the practical utility of residence time for predicting duration of action in vivo.

Another serious concern involves the equivalence between residence time and affinity. Critics argue that pursuing long residence time is fundamentally similar to pursuing high affinity, since koff contributes directly to both parameters [30]. In most practical cases, compounds with improved residence time also show enhanced affinity, making it difficult to isolate the unique contribution of residence time to efficacy [30]. Additionally, the residence time literature often emphasizes koff while neglecting kon, despite the importance of association rates for achieving rapid target engagement [30].

The relationship between different inhibition types and their kinetic parameters further complicates the residence time concept. Competitive inhibitors generally produce more pronounced drug-drug interactions than non-competitive inhibitors with the same Ki value [32]. Similarly, complete inhibitors typically cause more significant interactions than partial inhibitors [32]. These observations highlight that the mechanistic details of inhibition significantly influence in vivo effects beyond what residence time alone can capture.

Research Reagent Solutions and Technical Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Residence Time Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| sEH Inhibitor Library | Comprehensive compound collection for residence time studies | ~3000 compounds with diverse potency, physical properties, and PK parameters [31] |

| Recombinant sEH Enzymes | Well-characterized enzyme system for kinetic studies | Highly pure recombinant enzymes from multiple species [31] |

| LC/MS-MS Systems | Sensitive quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices | Limit of quantification ≤0.5 nM for precise blood and tissue measurements [31] |

| 50-BOA Software Package | Automated estimation of inhibition constants | User-friendly MATLAB and R packages implementing IC50-based optimal approach [8] |

| In Vivo Displacement Assay Components | Complete system for measuring target occupancy in live animals | Includes loading compounds, displacement compounds, and analytical methods [31] |

The drug-target residence time concept represents both an important advance and a subject of ongoing debate in drug discovery. While substantial evidence confirms that binding kinetics influence target engagement duration and metabolic protection [31], theoretical concerns about the overemphasis on koff separate from overall affinity remain unresolved [29] [30]. The most productive path forward likely involves integrated optimization of multiple parameters rather than singular focus on residence time.

Future research should prioritize developing more sophisticated models that simultaneously incorporate binding kinetics, pharmacokinetics, and tissue distribution. The continued refinement of experimental methods like the 50-BOA approach [8] and in vivo displacement assays [31] will provide increasingly precise data to validate and refine these models. Additionally, expanding residence time studies beyond soluble epoxide hydrolase to diverse target classes will clarify the generalizability of current findings.

For drug discovery practitioners, the current evidence supports measuring binding kinetics as a routine component of compound characterization while maintaining a balanced perspective on their interpretation. Residence time data provide valuable insights that complement rather than replace traditional affinity measurements, together enabling more informed decisions in the quest for efficacious therapeutics.

Evolution from IC50 to Kinetic Parameters in Modern Drug Discovery

The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) has long served as a foundational metric in drug discovery for ranking compound potency. However, this single-parameter approach provides an incomplete picture of inhibitor-enzyme interactions, failing to distinguish between binding affinity and efficiency. Contemporary drug discovery has increasingly shifted toward full kinetic characterization using parameters such as the inhibition constant (Kᵢ) and covalent modification rate constants (k₅ and k₆) that offer mechanistic insights and superior predictive value for in vivo performance. This technical guide examines innovative methodologies—including implicit equation modeling, EPIC-CoRe, and IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA)—that transform time-dependent IC₅₀ data into meaningful kinetic parameters, enabling more reliable candidate selection and optimization in modern pharmaceutical development.

Enzyme inhibition analysis constitutes a critical component of pharmaceutical development, from initial target validation to lead compound optimization. Traditional approaches have heavily relied on IC₅₀ values—the concentration of inhibitor required to reduce enzyme activity by 50% under specific assay conditions. While providing a useful initial potency measure, IC₅₀ represents an apparent value that varies significantly with experimental conditions, including substrate concentration, pre-incubation time, and enzyme levels [33]. This limitation substantially compromises its utility for comparing inhibitor potency across different laboratories and assay formats.

The evolution toward kinetic parameter determination addresses fundamental shortcomings of IC₅₀-based assessment. Kinetic parameters such as Kᵢ (inhibition constant) and k₍ᵢ₎ (rate constants) provide mechanism-independent constants that quantify the true binding affinity between inhibitor and enzyme target [34]. For reversible covalent inhibitors, which establish their covalent modification equilibrium slowly, additional parameters including the covalent modification rate constants (k₅ and k₆) are essential for understanding both binding and reactivity [35]. These parameters enable accurate ranking of drug candidates by distinguishing compounds with rapid binding from those with prolonged target residence times—a critical differentiator for in vivo efficacy.

Theoretical Foundation: From IC₅₀ to Meaningful Kinetic Parameters

Fundamental Kinetic Constants and Their Significance

The transition from IC₅₀ to kinetic parameters requires understanding several fundamental constants that define enzyme-inhibitor interactions:

- Kᵢ (Inhibition Constant): The dissociation constant for the enzyme-inhibitor complex, with lower values indicating tighter binding. Unlike IC₅₀, Kᵢ is a true constant independent of assay conditions [34].

- Kₘ (Michaelis Constant): The substrate concentration at half-maximal enzyme velocity, representing enzyme-substrate affinity [28].

- Vₘₐₓ (Maximum Velocity): The maximum reaction rate when enzyme is fully saturated with substrate [28].

- k₅ and k₆: Forward and reverse rate constants for reversible covalent inhibitors, defining the establishment and breakdown of covalent enzyme-inhibitor complexes [35].

For reversible inhibitors, the relationship between IC₅₀ and Kᵢ varies according to inhibition mechanism. In competitive inhibition, the Cheng-Prusoff equation describes this relationship: Kᵢ = IC₅₀ / (1 + [S]/Kₘ), where [S] is substrate concentration and Kₘ is Michaelis constant [34]. This relationship demonstrates the substrate dependence of IC₅₀ values—a fundamental limitation addressed by kinetic parameter determination.

Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms and Their Kinetic Signatures

Understanding inhibition mechanisms is essential for appropriate experimental design and data interpretation:

- Competitive Inhibition: Inhibitor competes with substrate for binding to the enzyme active site. Characterized by increased apparent Kₘ without effect on Vₘₐₓ [36].

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: Inhibitor binds exclusively to the enzyme-substrate complex. Results in decreased apparent Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ [8].

- Mixed Inhibition: Inhibitor binds to both enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex with different dissociation constants (Kᵢc and Kᵢu) [8].

Table 1: Kinetic Signatures of Major Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site | Effect on Apparent Kₘ | Effect on Apparent Vₘₐₓ | Lineweaver-Burk Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Enzyme active site | Increases | Unchanged | Intersecting at y-axis |

| Uncompetitive | Enzyme-substrate complex | Decreases | Decreases | Parallel lines |

| Mixed | Both enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex | Increases or decreases | Decreases | Intersecting in second quadrant |

Modern Methodologies for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

Advanced Mathematical Approaches

Contemporary solutions address the limitations of traditional IC₅₀ measurements through sophisticated mathematical modeling:

Implicit Equation Modeling for Reversible Covalent Inhibitors For reversible covalent inhibitors that establish equilibrium slowly, an implicit equation method estimates inhibition (Kᵢ) and covalent modification rate (k₅ and k₆) constants from incubation time-dependent IC₅₀ values. This approach enables characterization of both binding and reactivity components, facilitating fine-tuning of inhibitor properties [35].

EPIC-CoRe (Evaluation of Pre-Incubation Time Course for Reversible Inhibitors) This numerical modeling method fits kinetic parameters from pre-incubation time-dependent IC₅₀ data, providing a comprehensive framework for analyzing slow-binding reversible covalent inhibitors. Applied to saxagliptin evaluation, EPIC-CoRe generated results consistent with established methods while offering more efficient parameter estimation [35].

50-BOA (IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach) This innovative methodology incorporates the relationship between IC₅₀ and inhibition constants into the fitting process, enabling precise estimation with a single inhibitor concentration greater than IC₅₀. 50-BOA reduces experimental requirements by >75% while maintaining precision and accuracy compared to conventional multi-concentration designs [8].

The experimental workflow for implementing these approaches is detailed below:

Experimental Design Optimization

Traditional enzyme inhibition analysis employs a canonical approach measuring initial reaction velocity across multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations, typically at substrate concentrations of 0.2Kₘ, Kₘ, and 5Kₘ with inhibitor concentrations of 0, ¹/₃IC₅₀, IC₅₀, and 3IC₅₀ [8]. Error landscape analysis reveals that nearly half of these conventional data points contribute minimal information while potentially introducing bias [8].

The 50-BOA framework revolutionizes experimental design by demonstrating that accurate, precise estimation of inhibition constants requires only a single inhibitor concentration greater than IC₅₀ when the relationship between IC₅₀ and inhibition constants is incorporated into fitting algorithms [8]. This approach substantially reduces experimental burden while improving parameter reliability.

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional and Modern Kinetic Parameter Estimation Methods

| Method | Experimental Requirement | Key Parameters Obtained | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional IC₅₀ | Single point measurement | IC₅₀ value | Rapid, high-throughput | Condition-dependent, limited mechanistic insight |

| Cheng-Prusoff Conversion | IC₅₀ at known [S]/Kₘ ratio | Apparent Kᵢ | Simple calculation from IC₅₀ | Assumes specific mechanism, ignores time dependence |

| Full Kinetic Analysis | Multiple [S] and [I] combinations | Kᵢ, Kₘ, Vₘₐₓ | Mechanistic information, robust parameters | Resource-intensive, time-consuming |

| EPIC-CoRe | Time-dependent IC₅₀ values | Kᵢ, k₅, k₆ | Comprehensive for covalent inhibitors | Requires specialized modeling |

| 50-BOA | Single [I] > IC₅₀ with multiple [S] | Kᵢc, Kᵢu, IC₅₀ | High efficiency, reduced bias | New method, limited validation |

Practical Implementation: Experimental Protocols

Enzyme Inhibition Assay Protocol

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for generating data suitable for kinetic parameter estimation:

Reagents and Materials

- Purified enzyme preparation

- Inhibitor compounds dissolved in appropriate solvent

- Substrate solution

- Reaction buffer optimized for enzyme activity

- Stop solution (if required by detection method)

- Plate reader or spectrophotometer for detection

Procedure

- Prepare reaction mixtures with varying substrate concentrations (recommended: 0.2Kₘ, Kₘ, and 5Kₘ)

- Add inhibitor at concentrations spanning IC₅₀ value (for traditional method) or single concentration >IC₅₀ (for 50-BOA)

- Initiate reactions with enzyme addition

- Monitor reaction progress continuously or quench at multiple timepoints

- Measure product formation or substrate depletion

- Calculate initial velocities from linear phase of reaction progress curves

- Repeat for all substrate-inhibitor combinations

Data Analysis

- Plot initial velocity versus substrate concentration for each inhibitor level

- Fit data to appropriate inhibition model using nonlinear regression

- Calculate kinetic parameters with confidence intervals

- Validate model using statistical goodness-of-fit criteria

For reversible covalent inhibitors, additional time-course experiments with varying pre-incubation times are essential to determine k₅ and k₆ values [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Inhibition Studies | Example Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactase enzyme | Model enzyme for kinetic studies | Cost-effective educational and preliminary research [37] | Commercially available in purified form or from lactase pills |

| Tyrosinase | Enzyme for inhibitor detection | Amperometric biosensor construction for competitive inhibitors [33] | Immobilized onto carbon black paste electrode with glutaraldehyde/BSA |

| Carbon black paste electrode | Biosensor platform | Detection of o-quinones from tyrosinase activity [33] | High surface area, long-term stability for electrochemical detection |

| Glucometer | Glucose measurement | Indirect lactase activity monitoring via glucose production [37] | Cost-effective alternative to spectrophotometers |

| Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) | Reaction medium | Maintains pH and ionic strength during enzymatic assays [37] | Composition: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na₂HPO₄, 1.8 mM KH₂PO₄ |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Enzyme stabilization | Prevents enzyme denaturation during immobilization and storage [33] | Often used with glutaraldehyde for cross-linking immobilization |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence in Kinetic Parameter Estimation

Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing kinetic parameter determination through several innovative applications:

Generative AI for Molecular Design AI-driven approaches including generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs) now design novel inhibitors with predefined kinetic profiles, dramatically accelerating discovery timelines from years to months [38]. These systems incorporate multiobjective optimization to simultaneously maximize target affinity while minimizing toxicity risks.

Predictive Modeling for Parameter Estimation Machine learning algorithms trained on extensive kinetic datasets can predict inhibition constants from compound structural features, reducing experimental burden. Advanced models achieve >75% hit validation in virtual screening, enabling prioritization of compounds with favorable kinetic profiles before synthesis [38].

Automated Experimental Design and Analysis AI-powered platforms implement optimal experimental designs such as 50-BOA through automated workflows, integrating high-throughput experimentation with real-time data analysis. Closed-loop systems iteratively refine parameter estimates while minimizing resource consumption [38] [8].

The integration of these computational approaches with traditional enzyme kinetics is creating a new paradigm for inhibitor development, as illustrated below:

Standardization Initiatives and Data Reliability

The evolving landscape of kinetic parameter estimation emphasizes data quality and reproducibility through several key initiatives:

STRENDA (STandards for Reporting ENzymology DAta) This database establishes reporting requirements for enzyme kinetic data, ensuring adequate experimental detail accompanies published parameters [28]. Increasing journal adoption promotes consistency across studies.

BRENDA and SABIO-RK Databases These comprehensive resources provide curated kinetic parameters with source references, though users must critically evaluate assay conditions and enzyme sources for appropriate application [28].

Critical Assessment of Literature Values Researchers must verify that reported parameters derive from initial rate measurements under physiologically relevant conditions including appropriate temperature, pH, buffer composition, and ionic strength [28]. Assay conditions significantly impact parameter values, complicating cross-study comparisons.

The evolution from IC₅₀ to comprehensive kinetic parameters represents a paradigm shift in modern drug discovery, replacing a single-value potency metric with multidimensional characterization of inhibitor behavior. Methodologies such as EPIC-CoRe for reversible covalent inhibitors and 50-BOA for efficient parameter estimation exemplify this transition, offering mechanistic insights while reducing experimental burden. The integration of artificial intelligence with high-throughput experimentation further accelerates this transformation, enabling predictive compound design based on kinetic profiles rather than retrospective screening. As standardization initiatives improve data reliability and reporting consistency, kinetic parameter estimation will continue to advance as the cornerstone of rational inhibitor design, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and success of pharmaceutical development pipelines.

Advanced Kinetic Analysis Methods and Their Drug Discovery Applications