Enzyme Structure and Substrate Binding: From Atomic Mechanisms to Therapeutic Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzyme structure and substrate binding mechanisms, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Enzyme Structure and Substrate Binding: From Atomic Mechanisms to Therapeutic Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of enzyme structure and substrate binding mechanisms, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles of enzyme architecture, from primary to quaternary structure, and details the lock-and-key and induced-fit models of substrate recognition. The content covers advanced methodological approaches, including cryo-EM, molecular dynamics simulations, and docking studies, for investigating enzyme-substrate interactions. It further addresses challenges in enzyme engineering and optimization, highlighting the role of distal mutations in enhancing catalytic efficiency. Finally, the article examines validation techniques and comparative analyses across enzyme families, establishing a direct connection between structural insights and the development of enzyme-targeted therapeutics, with implications for treating metabolic disorders, cancer, and infectious diseases.

Architectural Blueprints: Exploring the Structural Hierarchy and Fundamental Mechanisms of Enzyme-Substrate Interactions

Enzymes, as biological catalysts, are indispensable for sustaining life, with their function exquisitely dictated by a hierarchical structural organization spanning four distinct levels: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary [1] [2]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of this hierarchy, framing it within ongoing research on enzyme structure and substrate binding mechanisms. We detail the covalent and non-covalent forces stabilizing each level, discuss advanced experimental and computational methodologies for structural interrogation, and explore the critical implications for drug development and enzyme engineering. The integration of machine learning (ML) with high-throughput screening is highlighted as a transformative approach for designing novel biocatalysts with tailored functions, offering new avenues for therapeutic and industrial applications [3].

Enzymes are predominantly globular proteins that act as highly specialized biological catalysts, dramatically accelerating biochemical reaction rates by lowering the activation energy barrier without being consumed in the process [4] [5]. The foundational principle of enzymology is that an enzyme's unique three-dimensional structure, arising from its specific amino acid sequence, determines its catalytic activity and specificity [6] [7]. This structure-function relationship is organized hierarchically, a concept critical for deconstructing enzyme mechanism and rational drug design.

Disruptions at any level of this structural organization can lead to a loss of function or pathogenic protein aggregation, as observed in conditions like sickle cell anemia and Alzheimer's disease [1] [8]. Consequently, a rigorous understanding of this hierarchy is not merely academic but essential for advancing research in enzymology and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

The Four Levels of Enzymatic Organization

Primary Structure: The Informational Blueprint

The primary structure is the most fundamental level, defined as the linear sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain, linked by covalent peptide bonds [1] [2]. This sequence is the determinant for all subsequent levels of folding and, ultimately, the enzyme's functional characteristics [8].

- Peptide Bond Characteristics: The peptide bond is rigid and planar due to its partial double-bond character, which restricts rotation and influences the possible conformations of the backbone [8]. The bonds on either side of the alpha-carbon, however, are free to rotate, defining the Ramchandran angles that govern the polypeptide chain's spatial orientation [8].

- Functional Implications: The amino acid sequence encodes all the information necessary for the enzyme's final three-dimensional shape. A single point mutation—such as the substitution of valine for glutamic acid at position six in the beta-globin chain of hemoglobin—can be sufficient to cause sickle cell anemia by altering the protein's structural and functional properties [1] [2]. This level of structure is maintained solely by strong covalent bonds and is not disrupted by denaturing conditions like heat or urea [8].

Secondary Structure: Local Folding Patterns

The secondary structure refers to local, regularly repeating folding patterns stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the backbone carbonyl oxygen (C=O) and amide hydrogen (N-H) groups [6] [2]. The two most prevalent types are the alpha-helix and the beta-pleated sheet.

- Alpha-Helix: This structure is a right-handed coiled conformation, with each turn comprising 3.6 amino acid residues [2] [8]. Hydrogen bonds form between the C=O of residue i and the N-H of residue i+4, creating a stable, rod-like structure. Amino acids like proline, which introduce kinks, or clusters of charged/bulky residues (e.g., tryptophan, isoleucine) can disrupt or terminate helix formation [8].

- Beta-Pleated Sheet: In this structure, polypeptide beta-strands align side-by-side, forming a sheet-like array stabilized by interstrand hydrogen bonds [6] [2]. Strands can run in the same direction (parallel) or opposite directions (antiparallel), with the latter being more stable. The surfaces of these sheets appear pleated due to the tetrahedral geometry of the alpha-carbons [8].

- Non-Repetitive Structures: Beta-turns (or reverse turns) are short, compact loops that allow the polypeptide chain to abruptly change direction, often facilitated by small residues like glycine or structure-breaking residues like proline [2] [8]. Loops and coils are irregular structures that provide flexibility and are often found at the protein surface.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Secondary Structures

| Feature | Alpha-Helix | Beta-Pleated Sheet | Beta-Turn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Right-handed coiled spiral | Extended strands forming a pleated sheet | Tight loop reversing chain direction |

| H-Bonding | Intrachain, between C=O of residue i and N-H of i+4 | Interchain, between adjacent strands | Often a single H-bond stabilizes the turn |

| Residues per Turn | 3.6 | 2 (for a 180° turn in antiparallel) | 4 residues typically form the turn |

| Strand Spacing | ~1.5 Å between adjacent residues | ~3.5 Å between adjacent residues in a strand | N/A |

| Disruptive Amino Acids | Proline, charged/bulky side chains (Val, Ile, Trp) | Bulky side chains can cause steric clashes | Requires specific residues (Gly, Pro common) |

Tertiary Structure: The Functional Three-Dimensional Form

The tertiary structure is the overall three-dimensional conformation of a single, fully folded polypeptide chain, formed by the packing of secondary structural elements and the interactions between amino acid side chains that may be distant in the primary sequence [2] [7]. This level is stabilized by a combination of non-covalent and covalent interactions, which are crucial for maintaining the enzyme's native, functional state.

Stabilizing Interactions:

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Non-polar side chains cluster in the interior of the protein, away from the aqueous environment, driving the folding process and providing significant stability [6] [2].

- Hydrogen Bonds: Polar side chains and the polypeptide backbone can form extensive networks of hydrogen bonds [2].

- Electrostatic (Ionic) Bonds: Attractive forces between positively (e.g., Lys, Arg) and negatively (e.g., Asp, Glu) charged side chains form salt bridges, often on the protein surface [6] [2].

- Van der Waals Forces: Weak, transient electrostatic interactions between closely packed atoms contribute to the stability of the protein core [6].

- Disulfide Bridges: Covalent bonds between the sulfur atoms of cysteine residues are a primary source of stability for extracellular enzymes, conferring rigidity and resistance to denaturation [6] [2].

Domains: The tertiary structure is often organized into semi-independent domains—compact, globular units that represent fundamental functional and structural modules [2] [8]. A single enzyme may contain multiple domains, such as catalytic, regulatory, and protein-protein interaction domains, enabling complex functionality and regulation [8].

Quaternary Structure: Multi-Subunit Assemblies

The quaternary structure refers to the spatial arrangement and non-covalent interactions between multiple independently folded polypeptide chains, or subunits, to form a single functional protein complex [1] [2]. Not all enzymes possess quaternary structure; it is a hallmark of proteins like hemoglobin, DNA polymerase, and many allosteric enzymes [2].

- Subunit Composition: Complexes can be homomeric (composed of identical subunits, e.g., lactate dehydrogenase) or heteromeric (composed of different subunits, e.g., hemoglobin with two α- and two β-globin chains) [6].

- Stabilizing Forces: The assembly is maintained by the same non-covalent interactions that stabilize tertiary structure: hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and electrostatic interactions [2]. In some cases, interchain disulfide bridges provide additional covalent stabilization [2].

- Functional Significance: Quaternary assembly enables sophisticated regulatory mechanisms, most notably allosteric regulation and cooperativity [6]. In hemoglobin, the binding of an oxygen molecule to one subunit induces conformational changes that increase the oxygen-binding affinity of the remaining subunits, resulting in a sigmoidal binding curve that is crucial for efficient oxygen uptake and release [1] [6].

Table 2: Forces Stabilizing Tertiary and Quaternary Structures

| Force Type | Nature of Interaction | Strength | Role in Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfide Bridge | Covalent bond between thiol groups of cysteine residues | Strong | Provides permanent, rigid cross-links, especially critical for extracellular protein stability [2]. |

| Hydrophobic Effect | Entropically driven clustering of non-polar side chains away from water | Strong | Major driving force for protein folding; creates the hydrophobic core [6] [2]. |

| Electrostatic (Ionic) Bonds | Attraction between oppositely charged side chains (e.g., NH₃⁺ of Lys, COO⁻ of Asp/Glu) | Strong | Forms salt bridges; often found on the protein surface; can be important for active site chemistry [6] [2]. |

| Hydrogen Bonds | Sharing of a hydrogen between an electronegative atom (O, N) and a hydrogen atom | Moderate | Abundantly stabilizes secondary structures and side-chain interactions; crucial for active site specificity [6] [2]. |

| Van der Waals Forces | Weak, transient attractive forces between closely packed electron clouds | Weak | Optimizes packing of atoms in the protein interior; contributes to overall stability [6]. |

Advanced Structural Concepts and Research Applications

Allosteric Regulation in Quaternary Assemblies

Allosteric regulation is a pivotal mechanism in metabolic control, where the binding of an effector molecule at a site distinct from the active site (the allosteric site) alters the enzyme's conformational equilibrium, thereby modulating its activity [6] [2]. This is a key functional consequence of quaternary structure.

- Mechanism: Effector binding induces a conformational change that is transmitted through the subunit interfaces, altering the enzyme's catalytic efficiency at the active sites of other subunits [2].

- Cooperativity: A classic example is positive cooperativity in hemoglobin, where oxygen binding to one subunit increases the affinity of the other subunits for oxygen, yielding a sigmoidal oxygen-binding curve [1] [6]. Conversely, negative cooperativity decreases the affinity of subsequent subunits, allowing for fine-tuned regulation of enzyme activity in complex metabolic pathways [6].

Experimental Protocols for Structural Determination

Understanding enzyme hierarchy relies on sophisticated biophysical techniques that provide atomic-level structural information.

Protocol 1: Determining Tertiary Structure via X-ray Crystallography X-ray crystallography is a primary method for determining high-resolution 3D structures of enzymes [2].

- Protein Purification and Crystallization: The target enzyme is expressed and purified to homogeneity. It is then induced to form highly ordered crystals by creating supersaturated conditions in a crystallization buffer. The quality of the crystal is critical for resolution.

- Data Collection: A crystal is exposed to a high-energy X-ray beam. The beam diffracts upon interacting with the electron clouds of the atoms in the crystal, producing a characteristic diffraction pattern.

- Phase Problem and Electron Density Map: The intensities of the diffraction spots are measured, but the phases of the waves are lost. Phases are determined experimentally (e.g., via molecular replacement using a known homologous structure or heavy-atom derivatization). The phased diffraction data are used to calculate an electron density map.

- Model Building and Refinement: An atomic model of the protein is built into the electron density map using computational software. The model is iteratively refined to minimize the discrepancy between the observed and calculated diffraction patterns, resulting in a final, detailed atomic structure [2].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Dynamics via Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy NMR spectroscopy is used to study protein structures in solution and investigate their dynamic behavior [2].

- Isotope Labeling: The protein is produced with isotopic labels (e.g., ¹⁵N, ¹³C) to aid in signal assignment.

- Data Acquisition: The labeled protein in solution is placed in a strong magnetic field and probed with radiofrequency pulses. A series of multi-dimensional NMR experiments (e.g., ¹⁵N-¹H HSQC, NOESY) are performed to measure through-bond (J-coupling) and through-space (Nuclear Overhauser Effect, NOE) interactions.

- Structure Calculation: NOE-derived distance restraints, along with dihedral angle restraints from J-couplings, are used as inputs for computational algorithms that calculate an ensemble of structures consistent with the experimental data. This ensemble provides insights into the protein's conformational flexibility [2].

Machine Learning-Guided Enzyme Engineering

Recent advances are merging high-throughput experimentation with machine learning to engineer enzymes with novel or enhanced properties. A pioneering study by Karim et al. developed a platform to engineer the amide synthetase McbA [3].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Library Generation: Creation of a defined library of 1,217 McbA mutant genes.

- Cell-Free Expression: High-throughput synthesis of the mutant enzymes using a cell-free protein expression system.

- Functional Screening: Performance of 10,953 unique reactions to quantitatively map the sequence-fitness landscape of the McbA variants for amide bond formation.

- Machine Learning Model Training: The resulting large-scale functional dataset was used to train an ML model to predict effective enzyme variants.

- Validation: The model successfully designed new McbA variants capable of synthesizing nine small-molecule pharmaceuticals, demonstrating improved activity in all cases [3].

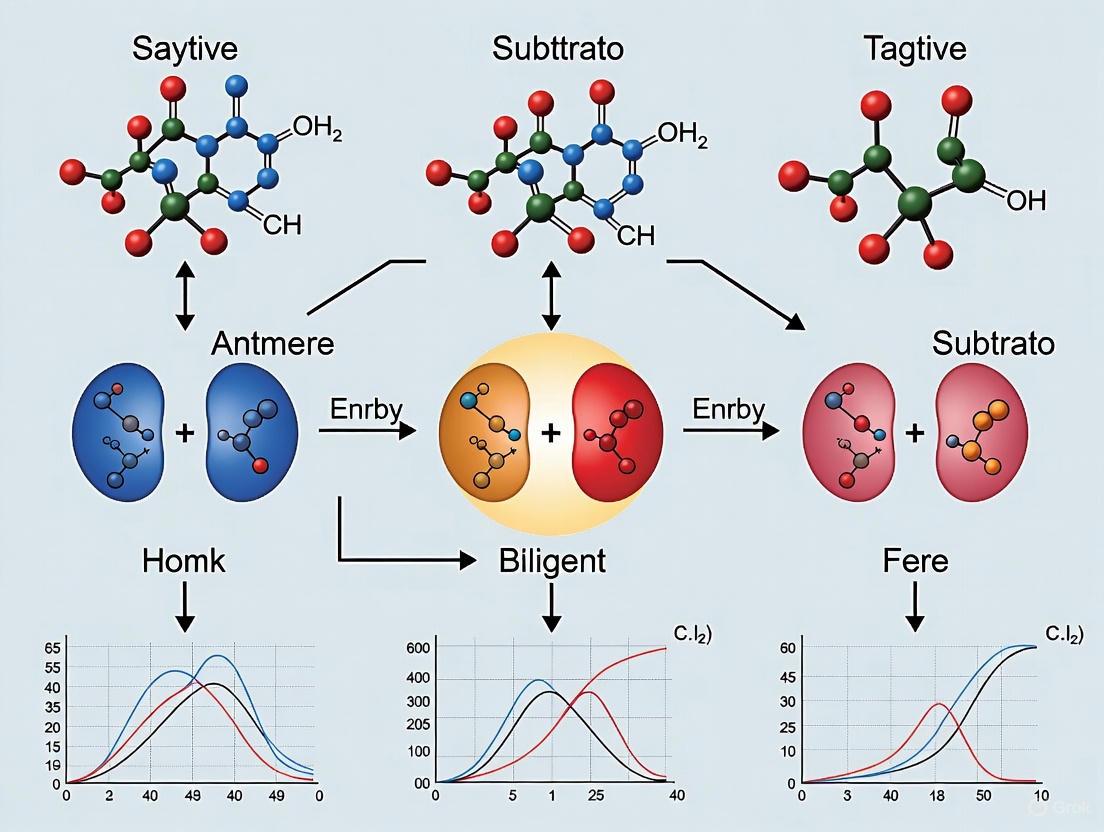

Diagram 1: ML-guided enzyme engineering workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Structural Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Expression System | Enables rapid, high-throughput synthesis of enzyme variants without the constraints of cellular viability, crucial for ML-guided engineering platforms [3]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Allows for the precise introduction of point mutations into the gene encoding an enzyme, enabling structure-function studies (e.g., alanine scanning). |

| Molecular Chaperones (Hsp70, GroEL/ES) | Facilitate the proper folding of polypeptides in vitro by providing a protected environment, preventing aggregation and studying folding pathways [2] [8]. |

| Protease & Nuclease Inhibitors | Protect enzyme samples during purification and handling from endogenous proteolytic and nucleolytic degradation. |

| Stable Isotope Labels (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Essential for NMR spectroscopy, allowing for residue-specific assignment and dynamic analysis of enzyme structures [2]. |

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Contain sparse matrixes of conditions to efficiently identify initial parameters for growing protein crystals for X-ray crystallography. |

| Allosteric Modulators/Inhibitors | Small molecules used as chemical probes to investigate allosteric communication pathways and conformational changes in multi-subunit enzymes. |

Discussion: Implications for Drug Discovery and Enzyme Engineering

The hierarchical model of enzyme structure is the cornerstone of modern drug discovery and biocatalyst development. Most pharmaceuticals function by modulating enzyme activity, often through competitive inhibition at the active site or allosteric regulation [9] [5]. A detailed understanding of the tertiary and quaternary structure is therefore indispensable for rational drug design, enabling the creation of highly specific inhibitors that minimize off-target effects.

Furthermore, the field of enzyme engineering leverages this knowledge to create "new-to-nature" biocatalysts. As demonstrated by Karim et al., the combination of structural insights and ML models allows researchers to navigate the vast sequence-function landscape efficiently [3]. This approach is poised to revolutionize the production of pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and biodegradable materials, contributing significantly to the growing bioeconomy. Future directions will likely involve integrating these methods with advanced AI to predict not only activity but also industrial stability from sequence alone.

The hierarchical organization of enzymes—from the linear primary sequence to the complex quaternary assembly—provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how biological catalysts are constructed and function. Each level, stabilized by a specific set of covalent and non-covalent interactions, builds upon the previous one to create a precise three-dimensional architecture capable of remarkable specificity and efficiency. Contemporary research, powered by structural biology techniques and machine learning, continues to deepen our understanding of this hierarchy. This knowledge is fundamentally advancing our capabilities in drug development and synthetic biology, enabling the precise engineering of enzymes to address pressing challenges in medicine and green chemistry.

The active site of an enzyme represents one of the most sophisticated architectural designs in biological systems, serving as the precise location where substrate binding and transformation occur. This highly specialized region, typically constituting a small portion of the enzyme's total structure, directly lowers the activation energy of biochemical reactions, thereby accelerating reaction rates by several orders of magnitude [10]. Enzymes achieve this remarkable catalytic efficiency through their defined three-dimensional structure, which forms specific cavities or clefts on their surface that are complementary to their target substrates [11] [12]. The architecture of these active sites is not static; rather, it embodies a dynamic interface where molecular recognition and chemical transformation converge through precisely positioned amino acid residues that facilitate bond breakage and formation [12].

Understanding active site architecture extends beyond fundamental biochemistry into practical applications in drug development and industrial biotechnology. The principles governing substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency directly inform rational drug design strategies where molecules are engineered to either mimic substrates or block active sites, thereby modulating enzymatic activity [13]. Furthermore, advances in computational biology and artificial intelligence are revolutionizing our ability to predict and manipulate active site properties, enabling the design of novel enzymes with tailored functions for therapeutic and industrial applications [14] [13]. This technical guide examines the structural components, mechanistic principles, and experimental methodologies that define active site architecture and its role in substrate binding and transformation.

Structural Components of the Active Site

Hierarchical Organization and Chemical Environment

The catalytic proficiency of an enzyme's active site emerges from its unique structural organization, which integrates multiple levels of protein architecture to create a highly specialized micro-environment. The primary structure (linear amino acid sequence) contains residues that may be distant in sequence but are brought into proximity through protein folding to form the functional active site [12] [15]. This folding creates the three-dimensional configuration essential for catalysis, with active sites typically residing in grooves, pockets, or clefts that exclude bulk solvent while creating specialized chemical environments optimized for specific reactions [12].

The chemical landscape of the active site is characterized by strategically positioned amino acid residues with specific functional groups that directly participate in catalysis. These residues create distinctive charge distributions and binding pockets that facilitate substrate orientation and stabilization [12] [15]. The active site architecture typically comprises two essential components: the catalytic site, where the chemical transformation occurs, and the substrate-binding site, which ensures precise substrate positioning and recognition [11]. This precise arrangement of amino acid side chains creates an environment that significantly differs from the surrounding aqueous medium, often enhancing nucleophilicity, electrostatic stabilization, or acid-base catalysis through strategic placement of residues such as histidine, aspartate, glutamate, cysteine, serine, and lysine [12].

Cofactors and Prosthetic Groups

Many enzymes require additional non-protein components, known as cofactors, to achieve full catalytic activity. These cofactors may be metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺, Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺) or complex organic molecules referred to as coenzymes [11] [12]. When tightly bound to the enzyme, these organic cofactors are termed prosthetic groups. These components often serve as essential functional elements within the active site, participating directly in catalytic mechanisms by facilitating electron transfer, substrate activation, or structural stabilization [12]. The integration of cofactors expands the catalytic repertoire beyond the limitations of standard amino acid side chains, enabling enzymes to catalyze a wider range of chemical transformations, including redox reactions that would otherwise be impossible with proteinaceous residues alone.

Table 1: Key Components of Enzyme Active Sites and Their Functions

| Component Type | Specific Examples | Function in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Residues | Serine, Histidine, Aspartate, Cysteine, Glutamate | Direct participation in bond cleavage/formation; acid-base catalysis; nucleophilic attack |

| Binding Residues | Hydrophobic patches, Charged side chains (Lys, Arg, Asp, Glu) | Substrate recognition and orientation; transition state stabilization |

| Cofactors | Metal ions (Zn²⁺, Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺), NAD⁺, FAD, PLP | Electron transfer; electrophilic catalysis; radical reactions; group transfer |

| Structural Elements | Disulfide bonds, Hydrogen bonding networks | Maintenance of active site geometry; stabilization of transition state |

Molecular Mechanisms of Substrate Binding and Catalysis

Molecular Recognition Models

The precise molecular recognition between an enzyme and its substrate is fundamental to catalytic specificity and efficiency. Two primary models describe this interaction: the Lock and Key Hypothesis and the Induced Fit Model. The Lock and Key Hypothesis, proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894, posits that the enzyme's active site possesses a rigid, pre-formed geometry that is complementary in shape and chemical character to its substrate, analogous to a key fitting into a lock [11] [16]. This model effectively explains enzyme specificity but fails to account for the dynamic nature of many enzyme-substrate interactions.

The more contemporary Induced Fit Model, proposed by Koshland in 1960, addresses these limitations by proposing that the active site is flexible and adaptable [11] [15] [16]. Upon initial substrate binding, the enzyme undergoes a conformational change that reshapes the active site to achieve optimal complementarity with the substrate [15]. This induced fit enhances catalytic efficiency by precisely orienting reactive groups and creating binding interactions that specifically stabilize the transition state of the reaction [15]. The dynamic nature of this model also explains how enzymes can exhibit broad specificity for multiple related substrates or be regulated through allosteric mechanisms where binding at one site induces conformational changes at distant active sites [15].

Catalytic Mechanisms and Transition State Stabilization

Enzymes employ several sophisticated mechanistic strategies to lower the activation energy of reactions, with most enzymes combining multiple approaches to achieve remarkable rate enhancements:

Transition State Stabilization: This is a fundamental strategy where the active site is structured to bind more tightly to the reaction's transition state than to either the substrate or product [15]. This preferential binding effectively lowers the energy barrier for the reaction, increasing the proportion of substrate molecules with sufficient energy to reach the transition state and proceed to products [11] [10].

Acid-Base Catalysis: Specific amino acid side chains within the active site can act as proton donors or acceptors, facilitating bond cleavage and formation by stabilizing charged intermediates [12]. Histidine is particularly important in this context due to its pKₐ near physiological pH, allowing it to function as both an acid and base.

Covalent Catalysis: This mechanism involves the formation of a transient covalent bond between the enzyme and substrate, creating a reaction intermediate with altered chemical properties that facilitates the transformation [16]. The enzyme's nucleophilic groups (e.g., serine hydroxyl, cysteine thiol, or histidine imidazole) attack electrophilic centers on the substrate, forming short-lived covalent complexes that are subsequently resolved to yield products.

Orientation and Proximity Effects: By binding substrates in specific orientations and bringing reactive groups into close proximity, enzymes effectively increase the local concentration of reactants and ensure that collisions occur with proper geometry, significantly enhancing reaction probability [11].

Figure 1: Enzyme Catalytic Cycle illustrating the formation of enzyme-substrate and enzyme-product complexes during catalysis

Experimental Methodologies for Active Site Characterization

Structural Determination Techniques

Elucidating the detailed architecture of enzyme active sites requires sophisticated experimental approaches that can resolve atomic-level details. The following methodologies represent cornerstone techniques in active site characterization:

X-ray Crystallography: This technique provides high-resolution three-dimensional structures of enzyme-substrate complexes, enabling direct visualization of active site geometry, substrate orientation, and amino acid coordination [12]. By solving structures with bound substrates, inhibitors, or transition state analogs, researchers can infer mechanistic details and identify key residues involved in catalysis and binding.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis: This approach involves systematically altering specific amino acid residues within the putative active site and analyzing the functional consequences on catalytic efficiency and substrate binding [17]. By replacing suspected catalytic residues (e.g., changing serine to alanine) and measuring kinetic parameters, researchers can directly determine the functional contribution of individual amino acids to the catalytic mechanism.

Spectroscopic Methods: Techniques such as NMR spectroscopy and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) provide insights into the dynamic aspects of active sites, including conformational changes, protonation states, and electronic environments of cofactors [12]. These methods are particularly valuable for studying reaction intermediates and time-dependent processes.

Kinetic Analysis and Parameter Determination

Quantitative assessment of enzyme activity provides critical information about active site function and efficiency. Standard kinetic analyses measure the rates of substrate conversion under controlled conditions to determine key parameters:

Michaelis-Menten Kinetics: This foundational approach measures initial reaction velocities at varying substrate concentrations to determine Kₘ (Michaelis constant) and Vₘₐₓ (maximum velocity) values [13] [17]. The Kₘ provides information about substrate binding affinity, while k꜀ₐₜ (calculated from Vₘₐₓ) represents the catalytic turnover number, indicating the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per active site per unit time [13].

Inhibition Studies: Analyzing how specific inhibitors affect enzyme kinetics provides insights into active site architecture and mechanism [13]. Competitive inhibitors typically bind directly to the active site, increasing the apparent Kₘ without affecting Vₘₐₓ, while non-competitive inhibitors bind to allosteric sites, altering the active site conformation and reducing Vₘₐₓ [15] [10].

Table 2: Key Kinetic Parameters for Enzyme Characterization

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover Number | k꜀ₐₜ | Maximum number of substrate molecules converted per active site per second | Direct measure of catalytic efficiency |

| Michaelis Constant | Kₘ | Substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity | Inverse measure of substrate binding affinity |

| Catalytic Efficiency | k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ | Ratio of turnover number to Michaelis constant | Overall measure of enzymatic proficiency; higher values indicate more efficient enzymes |

| Inhibition Constant | Kᵢ | Dissociation constant for enzyme-inhibitor complex | Measure of inhibitor potency; lower values indicate tighter binding |

Advanced computational approaches are increasingly complementing experimental methods. Tools like CatPred leverage deep learning frameworks to predict in vitro enzyme kinetic parameters (k꜀ₐₜ, Kₘ, and Kᵢ) by exploring diverse learning architectures and feature representations, including pretrained protein language models and three-dimensional structural features [13]. Similarly, AlphaFold3 has achieved high-precision prediction of protein-substrate interactions, advancing structure-based enzyme discovery and design [14].

Computational and AI-Driven Advances

Predictive Modeling and Deep Learning Applications

The integration of artificial intelligence and computational methods has revolutionized the study of active site architecture, enabling predictive modeling at unprecedented scales and accuracy. Deep learning frameworks such as CatPred address key challenges in enzyme kinetics prediction, including performance evaluation on enzyme sequences dissimilar to training data and model uncertainty quantification [13]. These approaches utilize diverse feature representations, with pretrained protein language models particularly enhancing performance on out-of-distribution samples by capturing evolutionary patterns and structural constraints from vast sequence databases [13].

The CatPred framework exemplifies this advancement, providing accurate predictions with query-specific uncertainty estimates by employing ensemble-based approaches that distinguish between aleatoric uncertainty (inherent data noise) and epistemic uncertainty (model uncertainty due to limited training data) [13]. This capability is particularly valuable for drug development applications where understanding prediction reliability informs decision-making in lead compound optimization and off-target effect assessment.

Data Extraction and Curation Technologies

A significant bottleneck in enzyme kinetics research has been the limited availability of standardized, high-quality datasets. Traditional databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK contain extensive kinetic measurements but capture only a fraction of published parameters [17]. Recent advances in large language model (LLM) applications are addressing this limitation through automated extraction tools such as EnzyExtract, which processes full-text scientific literature to identify and structure enzyme kinetic data [17].

This AI-powered pipeline has demonstrated remarkable efficacy, extracting over 218,095 enzyme-substrate-kinetics entries from 137,892 publications and identifying 89,544 unique kinetic entries absent from BRENDA [17]. By incorporating specialized optical character recognition and entity disambiguation techniques, EnzyExtract maps extracted data to standardized identifiers in UniProt and PubChem, creating sequence-mapped enzymology databases that significantly enhance predictive model performance when used for retraining state-of-the-art kinetic parameter predictors [17].

Figure 2: AI-enhanced research workflow for active site analysis and kinetic parameter prediction

Research Reagent Solutions for Active Site Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Active Site Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | Transition state analogs, Competitive inhibitors, Allosteric modulators | Mapping active site topology, Determining mechanistic pathways | Probe substrate binding pockets, Identify catalytic residues, Elucidate regulatory mechanisms |

| Spectroscopic Probes | Fluorescent dyes, Spin labels, NMR-active nuclei | Monitoring conformational changes, Assessing binding events | Report on local environment changes, Distance measurements at atomic scale, Track structural dynamics |

| Crystallography Reagents | Cryoprotectants (glycerol), Heavy atom derivatives (Hg, Pt salts) | Structure determination of enzyme complexes | Facilitate crystal formation, Enable phase determination, Preserve crystal integrity during data collection |

| Mutagenesis Kits | Site-directed mutagenesis systems, CRISPR-Cas9 editors | Functional analysis of specific residues | Alter specific amino acids in active site, Establish structure-function relationships, Engineer novel enzyme properties |

| Activity Assays | Chromogenic substrates, Fluorogenic probes, Antibody-based detection | Quantifying enzymatic rates and inhibition | Provide measurable signal proportional to activity, Enable high-throughput screening, Facilitate kinetic parameter determination |

The architecture of enzyme active sites represents a sophisticated integration of structural elements, chemical functionalities, and dynamic properties that collectively enable remarkable catalytic efficiency and specificity. Through precise three-dimensional arrangement of amino acid residues and cofactors, active sites create specialized microenvironments that stabilize transition states and lower activation energy barriers for biochemical transformations. The continuing evolution of experimental and computational methodologies, particularly AI-enhanced prediction frameworks and large-scale data extraction tools, is rapidly advancing our understanding of these fundamental catalytic centers. These developments promise to accelerate applications in drug discovery, where detailed active site knowledge enables rational inhibitor design, and in industrial biotechnology, where enzyme engineering creates tailored catalysts for specific synthetic needs. As research continues to unravel the complexities of active site architecture, our ability to predict, manipulate, and design catalytic function will undoubtedly expand, opening new frontiers in biochemistry and molecular medicine.

The molecular recognition of substrates by enzymes represents a cornerstone of biochemical research, with the classical Lock-and-Key and Induced Fit hypotheses providing foundational frameworks for understanding enzyme specificity and catalysis. Proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894, the Lock-and-Key model established the fundamental principle of geometric complementarity between enzymes and their substrates, suggesting that the active site possesses a rigid, pre-formed structure that perfectly accommodates its substrate much like a key fits into a specific lock [18] [16]. This model successfully explained enzyme specificity but failed to account for the dynamic nature of enzyme-substrate interactions and the structural flexibility observed in many enzymes.

In 1958, Daniel E. Koshland proposed the Induced Fit hypothesis to address these limitations, introducing a more dynamic view of enzyme-substrate recognition [18]. This model posits that the active site is not rigid but flexible, undergoing conformational adjustments upon substrate binding to optimize complementarity. According to this view, the initial binding induces structural changes in both the enzyme and substrate that lead to the precise orientation necessary for catalysis, prioritizing stabilization of the transition state over the ground state substrate complex [19] [20]. This paradigm shift from a static to dynamic recognition mechanism has profoundly influenced our understanding of enzyme function, allosteric regulation, and the development of enzyme-targeted therapeutics.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Principles of Each Model

The Lock-and-Key model emphasizes structural complementarity as the primary determinant of enzyme specificity. According to this view, the active site's three-dimensional configuration contains precisely positioned chemical groups that create a sterically and chemically complementary environment for the substrate [16]. This precise fit allows for the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex without requiring structural rearrangements, facilitating catalysis through proximity and orientation effects. The model effectively explains why enzymes typically exhibit high specificity for their native substrates and provides a straightforward mechanism for competitive inhibition, where inhibitor molecules mimic the substrate's shape to block the active site [18].

In contrast, the Induced Fit hypothesis introduces a temporal dimension to enzyme-substrate recognition, emphasizing the conformational plasticity of enzyme structures. This model proposes that substrate binding induces precise alignment of catalytic groups within the active site that may not exist in the unbound enzyme [18] [21]. The induced conformational changes serve multiple purposes: they enhance catalytic efficiency by optimizing the active site geometry for the transition state, prevent unnecessary side reactions by isolating the substrate from solvent, and provide a mechanism for allosteric regulation where binding at one site influences activity at another [19]. This dynamic recognition process explains how some enzymes can catalyze reactions for multiple related substrates and accounts for observed cooperativity in multi-subunit enzymes [20].

Comparative Structural and Energetic Profiles

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Lock-and-Key versus Induced Fit Models

| Characteristic | Lock-and-Key Model | Induced Fit Model |

|---|---|---|

| Active Site Structure | Rigid and static [18] | Flexible and dynamic [18] |

| Substrate Complementarity | Perfect in ground state [20] | Optimized for transition state [19] |

| Conformational Changes | None upon binding [18] | Significant in both enzyme and substrate [19] |

| Energy Landscape | Potential for overly stable ES complex [19] | Stabilized transition state lowers activation energy [19] |

| Allosteric Regulation | Not explained [18] | Explains cooperative effects [18] |

| Competitive Inhibition | Explained by steric blockage [18] | Explains non-competitive inhibition [18] |

| Historical Context | Proposed by Emil Fischer (1894) [18] [16] | Proposed by Daniel Koshland (1958) [18] |

The energy diagrams below illustrate the fundamental thermodynamic differences between these two recognition mechanisms, highlighting how each model approaches activation energy reduction:

The Lock-and-Key model often results in an overly stable enzyme-substrate (ES) complex that may not effectively lower the activation energy (Ea) barrier, as indicated by the red arrow [19]. In contrast, the Induced Fit model prioritizes transition state (ES*) stabilization, significantly reducing the activation energy (green arrow) and thereby enhancing catalytic efficiency [19].

Experimental Methodologies and Validation

Structural Biology Approaches

X-ray crystallography has served as a pivotal technique for distinguishing between these recognition models. By solving enzyme structures both in their apo form and in complex with substrates or transition state analogs, researchers can directly observe whether conformational changes occur upon binding [22] [23]. For example, studies on engineered Kemp eliminases have revealed that active-site mutations create preorganized catalytic sites, while distal mutations facilitate substrate binding and product release through dynamic structural adjustments [22]. These crystallographic analyses typically involve:

Protein Purification and Crystallization: Recombinant enzymes are expressed in systems like E. coli or HEK293 cells and purified to homogeneity using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification) followed by size exclusion chromatography [24]. Crystallization screens employ various conditions to obtain diffraction-quality crystals.

Ligand Soaking or Co-crystallization: Substrates, inhibitors, or transition state analogs are introduced either by soaking into pre-formed crystals or through co-crystallization [22]. For instance, 6-nitrobenzotriazole (6NBT) has been used as a transition state analog in Kemp eliminase studies [22].

Data Collection and Structure Determination: High-resolution X-ray diffraction data are collected at synchrotron facilities, followed by phase determination and structural refinement. Comparative analysis of ligand-bound versus apo structures reveals conformational changes supporting induced fit mechanisms [22].

Kinetic Analysis and Binding Studies

Enzyme kinetics provides functional evidence for distinguishing recognition mechanisms through detailed analysis of reaction rates and binding constants [23]. The Michaelis-Menten equation (v₀ = Vₘₐₓ[S]/(Kₘ + [S])) describes the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity, where Kₘ represents the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity and serves as an approximate measure of substrate affinity [23]. Key methodological considerations include:

Initial Rate Determinations: Enzyme assays are conducted under conditions where substrate depletion is minimal (typically <5%), allowing accurate measurement of initial velocities [23]. Continuous assays using spectrophotometric methods provide real-time monitoring of product formation.

Progress Curve Analysis: For slower reactions, complete time courses are analyzed using nonlinear regression to extract kinetic parameters [23]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying pre-steady-state kinetics.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Techniques like Biacore enable direct measurement of binding kinetics (kₒₙ and kₒff) and equilibrium dissociation constants (K_D) without requiring enzyme activity [24]. SPR studies have revealed that compounds with similar affinities can have markedly different binding kinetics, providing insights into recognition mechanisms [24].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Assay Components

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transition State Analogs | 6-nitrobenzotriazole (6NBT) [22] | Probing active site complementarity to transition state |

| Expression Systems | HEK293, CHO cells, E. coli [24] | Recombinant enzyme production |

| Purification Tags | Polyhistidine (His-tag), GST [24] | Affinity chromatography purification |

| Binding Assay Components | Radioligands (³H, ¹²⁵I), fluorescent probes [24] | Direct binding measurements |

| Enzyme Assay Components | NADH (for dehydrogenases), chromogenic substrates [23] | Continuous activity monitoring |

| Crystallization Reagents | PEGs, salts, buffers [22] | Protein crystallization for structural studies |

Biophysical and Computational Approaches

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as powerful tools for visualizing the temporal evolution of enzyme-substrate interactions, providing atomic-level insights into recognition mechanisms [22]. These computational approaches complement experimental findings by:

Sampling Conformational Landscapes: MD simulations explore the flexible nature of enzymes, revealing how substrate binding restricts conformational freedom and stabilizes catalytically competent states [22].

Identifying Allosteric Networks: Simulations can detect how distal mutations influence active site dynamics through long-range interactions, as demonstrated in studies where distal mutations widened active-site entrances and reorganized surface loops in Kemp eliminases [22].

Energy Calculations: Free energy perturbation methods quantify the energetic contributions of specific residues to substrate binding and catalysis.

The integrated experimental workflow below illustrates how these diverse methodologies converge to elucidate enzyme recognition mechanisms:

Current Research and Practical Applications

Insights from Enzyme Engineering and Directed Evolution

Recent studies on de novo designed Kemp eliminases have revealed sophisticated aspects of enzyme recognition mechanisms that transcend simple categorization into Lock-and-Key versus Induced Fit models. Directed evolution of these artificial enzymes has demonstrated that both active-site (Core) and distal (Shell) mutations contribute distinctly to catalytic efficiency [22]. While active-site mutations primarily create preorganized catalytic environments optimized for the chemical transformation step, distal mutations enhance catalysis by facilitating substrate binding and product release through modulation of structural dynamics [22]. This research demonstrates that optimal enzyme function requires a balance between active site organization (emphasized in the Lock-and-Key model) and dynamic flexibility (highlighted in the Induced Fit model).

Notably, these studies have challenged the historical view that distal mutations primarily serve compensatory roles in stabilizing engineered enzymes. Instead, they actively participate in shaping the catalytic cycle by widening active-site entrances and reorganizing surface loops, demonstrating that a well-organized active site, while necessary, is insufficient for optimal catalysis [22]. These findings underscore the functional significance of enzyme dynamics in substrate recognition and have important implications for enzyme design strategies.

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The distinction between Lock-and-Key and Induced Fit mechanisms has profound consequences for pharmaceutical research, particularly in inhibitor design and optimization. Understanding enzyme flexibility and transition state stabilization has led to several important applications:

Rational Drug Design: Knowledge of induced fit mechanisms enables the design of inhibitors that specifically target transition state analogs rather than ground state substrates, often resulting in higher affinity and selectivity [24]. For example, the drug Tiotropium exploits differential off-rates at muscarinic receptor subtypes due to distinct induced fit responses, resulting in physiological selectivity despite similar binding affinities [24].

Kinetic Optimization: Modern drug discovery programs increasingly consider binding kinetics (residence time) alongside affinity measurements, as compounds with slow dissociation rates often demonstrate superior efficacy [24]. Surface plasmon resonance techniques enable direct measurement of these parameters.

Allosteric Modulator Development: The Induced Fit model's emphasis on conformational changes has facilitated the development of allosteric regulators that modulate enzyme activity by binding at sites distinct from the active center, offering greater specificity and novel therapeutic approaches.

The classical Lock-and-Key and Induced Fit hypotheses, though historically presented as competing models, now represent complementary aspects of a comprehensive understanding of enzyme recognition mechanisms. Contemporary research reveals that enzyme function emerges from complex interplays between structural complementarity and dynamic adaptability, with different enzymes occupying various positions along this mechanistic spectrum. The Lock-and-Key model effectively explains the remarkable specificity of many enzymatic reactions, while the Induced Fit model accounts for regulatory complexity, multi-substrate capability, and transition state stabilization.

Future research directions will likely focus on quantifying the energetic contributions of conformational changes to catalytic efficiency, engineering dynamic control into artificial enzymes, and developing therapeutic agents that specifically target distinct recognition states. As single-molecule techniques and computational methods continue to advance, our understanding of these fundamental recognition mechanisms will become increasingly refined, enabling more sophisticated manipulation of enzyme function for industrial, research, and therapeutic applications.

Enzymes, as biological catalysts, are predominantly composed of proteins built from amino acids. While the functional groups of these amino acids can catalyze a wide array of chemical reactions through ionic interactions or acid-base mechanisms, their catalytic repertoire is inherently limited. Amino acids alone cannot efficiently catalyze crucial biochemical reactions such as oxidation-reduction and specific group transfer reactions. To overcome these limitations, many enzymes require the assistance of non-protein components known as cofactors [25]. These essential partners expand the catalytic capabilities of enzymes, enabling the diverse biochemistry that sustains life. Within the broader context of enzyme structure and substrate binding mechanisms research, understanding cofactors is fundamental to deciphering catalytic efficiency, specificity, and regulation. For researchers and drug development professionals, this knowledge provides critical insights for designing enzyme inhibitors, understanding metabolic diseases, and developing therapeutic interventions that target specific enzymatic pathways.

The terminology in this field has evolved somewhat haphazardly, leading to multiple classification systems. According to the Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI) database, a cofactor is broadly defined as "an organic molecule or ion (usually a metal ion) that is required by an enzyme for its activity" [26]. This overarching category is then subdivided based on chemical composition and binding affinity. The complete, catalytically active enzyme-cofactor complex is termed a holoenzyme, while the protein component alone is called an apoenzyme [27] [25] [28]. An apoenzyme without its necessary cofactor is typically inactive, as it lacks the chemical functionality required for complete catalysis [28].

Classification and Definitions

Cofactors can be classified through two primary, overlapping frameworks: one based on their chemical nature (organic versus inorganic) and another based on their binding affinity and behavior during the catalytic cycle.

Hierarchical Classification of Cofactors

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between the different types of cofactors:

Chemical Classification of Cofactors

Inorganic Cofactors: These are typically metal ions that associate with enzymes, either loosely or tightly. Common examples include Mg²⁺, Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Mn²⁺, as well as inorganic ions like chloride (Cl⁻) [28] [29]. For instance, chloride ions act as a cofactor for amylase, while zinc ions serve as a prosthetic group in carbonic anhydrase [28]. These ions often help stabilize the enzyme's structure, facilitate substrate binding, or participate directly in the reaction at the active site by stabilizing charged intermediates or facilitating electron transfer [28] [29].

Organic Cofactors: This category encompasses organic molecules, which are further subdivided into coenzymes and prosthetic groups based on their binding mode [26]. The key distinction lies in the permanence of their association with the enzyme.

Coenzymes: These are organic, non-protein molecules that often bind transiently to the enzyme during the catalytic cycle [27] [30]. They are typically derived from water-soluble vitamins and act as shuttle molecules, carrying electrons or specific functional groups between different enzymes [31] [28]. A classic example is Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD⁺), derived from vitamin B3 (nicotinic acid), which functions as a cosubstrate in oxidation-reduction reactions by accepting electrons and being converted to NADH [25] [28]. Because they are altered during the reaction and dissociate, they are reusable and must be regenerated for continuous catalysis [30].

Prosthetic Groups: These are cofactors, either organic or inorganic, that are tightly or even covalently bound to their apoenzyme [31] [30] [28]. They form a permanent feature of the enzyme's structure and are essential for its function [28]. Unlike cosubstrates, prosthetic groups do not dissociate from the enzyme after the reaction is complete and are not modified in a way that requires regeneration for subsequent cycles [31] [27]. A prime example is the heme group in hemoglobin and cytochromes, a porphyrin ring coordinated to an iron ion that is covalently linked to the protein moiety in c-type cytochromes [32] [25]. Another example is the zinc ion in carbonic anhydrase, which is permanently bound and crucial for its catalytic activity in converting carbon dioxide and water into carbonic acid [28]. Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide (FAD) is often classified as a prosthetic group because, despite being involved in redox reactions, it remains firmly associated with its enzyme [31] [26].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cofactor Types

| Characteristic | Inorganic Cofactors | Coenzymes (Cosubstrates) | Prosthetic Groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nature | Inorganic ions (e.g., Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Cl⁻) [28] [29] | Organic molecules (often vitamin-derived) [31] [29] | Organic molecules or metal ions [28] [26] |

| Binding Affinity | Loosely or tightly bound | Loosely bound, transient association [27] [30] | Tightly or covalently bound, permanent association [31] [28] |

| Role in Catalysis | Stabilize structure, participate in reactions [29] | Transfer chemical groups/electrons between enzymes [30] [28] | Integral part of active site, direct role in reaction [30] |

| Fate in Reaction | Typically unchanged | Modified and dissociate, require regeneration [30] | Remain attached and are not consumed [31] |

| Examples | Zn²⁺ in carbonic anhydrase, Cl⁻ in amylase [28] | NAD⁺, Coenzyme A [25] [28] | Heme in hemoglobin, FAD in some enzymes [32] [31] |

Mechanisms of Action in Catalytic Function

Cofactors and prosthetic groups enhance enzymatic catalysis through several sophisticated mechanistic strategies that complement the chemical capabilities of amino acid side chains.

Facilitating Oxidation-Reduction Reactions

A primary function of many cofactors is to mediate electron transfer in redox reactions, a process poorly served by standard amino acids. Oxidoreductase enzymes rely heavily on cofactors for this purpose. NAD⁺ and FAD are exemplary coenzymes that function as electron carriers. NAD⁺ accepts a hydride ion (H⁻) to become NADH, while FAD accepts two hydrogen atoms to become FADH₂ [28]. These reduced forms then shuttle electrons to other metabolic pathways, such as the electron transport chain. Prosthetic groups like the heme iron in cytochromes also participate in electron transfer through reversible changes in the oxidation state of their central iron ion (Fe²⁺ Fe³⁺) [32]. The heme group in c-type cytochromes is covalently attached to the polypeptide via thioether bonds formed between the vinyl groups of heme and the thiol groups of two cysteinyl residues in a conserved Cys-X-Y-Cys-His peptide motif, ensuring its permanent integration into the electron transport machinery [32].

Enabling Group Transfer Reactions

A vast array of metabolic pathways depends on the transfer of specific functional groups, a function efficiently performed by coenzymes. Transferase enzymes utilize coenzymes that act as activated carrier molecules. For instance, Coenzyme A (CoA) is essential for transferring acyl groups (e.g., acetyl-CoA) in critical processes like the citric acid cycle and fatty acid metabolism [28]. ATP universally transfers phosphate groups, coupling energy release from catabolism to energy-requiring processes [28]. Another key example is pyridoxal phosphate (derived from vitamin B6), which serves as a carrier of amino groups in transamination reactions, fundamental to amino acid synthesis and degradation [31].

Stabilizing Transition States and Modifying the Active Site Environment

Metal ion cofactors and prosthetic groups are masters of electrostatic catalysis. They can stabilize negatively charged transition states and intermediates that would otherwise be highly unfavorable. The Zn²⁺ ion in carbonic anhydrase is a classic example. This metalloenzyme catalyzes the rapid conversion of CO₂ and H₂O to carbonic acid. The Zn²⁺ ion, held in place by coordination to three histidine side chains in the active site, polarizes a water molecule, facilitating the deprotonation to form a nucleophilic hydroxide ion. This hydroxide then attacks CO₂, significantly lowering the activation energy of the reaction [28]. Without this prosthetic group, the reaction would be physiologically irrelevant.

The conceptual relationship between a cofactor, its enzyme, and the catalytic outcome is summarized below:

The Role of Induced Fit in Cofactor-Assisted Catalysis

The binding of a cofactor or prosthetic group can induce conformational changes in the enzyme's structure, a phenomenon described by the induced fit model [33] [30]. This structural reorganization is not merely passive; it actively optimizes the active site for substrate binding and catalysis. The cofactor helps to "tug" on the enzyme and substrate molecules, applying energy that helps coax the molecules into the transition state, thereby facilitating the reaction [33]. This dynamic interaction is crucial for the high specificity exhibited by many enzymes, as the correct substrate must induce the precise conformational change that aligns the cofactor and catalytic residues for efficient catalysis.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Prosthetic Groups

Investigating the structure, binding, and function of prosthetic groups requires a multidisciplinary approach. Below are detailed methodologies for key experimental paradigms, using heme-containing proteins like cytochromes as a primary model.

Protocol: Detachment and Analysis of a Covalently Bound Prosthetic Group

This protocol is designed to isolate and characterize a tightly bound prosthetic group, such as the heme in c-type cytochromes, to confirm its covalent linkage and identify its chemical structure.

Objective: To isolate the heme prosthetic group from cytochrome c and confirm its covalent attachment to the apoprotein. Background: In c-type cytochromes, the heme is covalently linked to the polypeptide chain via thioether bonds between the heme's vinyl groups and the cysteine residues of a Cys-X-Y-Cys-His motif. These bonds are stable to heat and acid hydrolysis but can be cleaved with specific reagents [32].

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified cytochrome c (e.g., from horse heart or bovine heart).

- Silver salts (AgNO₃) or Mercury salts (HgCl₂): Used to cleave the thioether bonds by targeting the sulfur-cysteine linkages [32].

- Acidification agents (e.g., Trichloroacetic acid): For protein precipitation.

- Organic solvents (Acetone, Diethyl ether): For extraction and purification of the liberated heme group.

- Spectrophotometer (UV-Vis): For monitoring the characteristic Soret band (~400 nm) and Q-bands of heme.

- Mass Spectrometer (MALDI-TOF or ESI-MS): For precise determination of the molecular weight of the isolated heme peptide.

- HPLC system: For purification of heme and peptide fragments.

Methodology:

- Protein Denaturation and Cleavage:

- Incubate a purified sample of cytochrome c (~1-5 mg/mL) with 10 mM AgNO₃ or HgCl₂ in an appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH ~7.0) for 1-2 hours at 37°C in the dark [32].

- Include a control sample without the silver/mercury salt to confirm the stability of the native linkage.

- Separation of Components:

- Precipitate the apoprotein by acidifying the solution with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to a final concentration of 5-10%. Centrifuge to pellet the denatured protein.

- The supernatant, containing the liberated heme, is collected.

- Heme Extraction:

- Extract the heme from the aqueous supernatant into an organic solvent like acidified acetone or diethyl ether.

- Evaporate the solvent under a gentle stream of nitrogen to obtain the purified heme.

- Proteolytic Digestion (Alternative Method):

- As an alternative to chemical cleavage, digest the native cytochrome c with a protease (e.g., trypsin or pepsin).

- The covalent heme-peptide bonds are resistant to proteolysis, resulting in heme-bearing peptides [32].

- Analysis:

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Analyze the extracted heme or heme-peptides. The Soret band and characteristic alpha and beta bands confirm the presence and redox state of the heme.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze the proteolytic digest. The presence of a peptide with a mass increase corresponding to the heme group confirms the covalent attachment and identifies the specific peptide sequence bearing the prosthetic group.

Data Interpretation: Successful detachment via silver salts indicates the presence of labile bonds, typical of metal-sensitive linkages like thioethers. Mass spectrometric identification of a heme-bound peptide provides definitive evidence of a covalent prosthetic group and allows for mapping the exact attachment sites.

Protocol: Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy to Probe Ligand Binding in Heme Proteins

This technique is particularly powerful for studying the active site environment and dynamics of prosthetic groups.

Objective: To characterize the binding of small diatomic ligands (e.g., CO, NO) to the iron center of a heme prosthetic group and probe the influence of the protein environment. Background: The vibrational frequencies of bonds in a ligand (like C-O or N-O) are exquisitely sensitive to the electronic properties of the metal center and the surrounding protein matrix. IR spectroscopy can detect these vibrations, providing a fingerprint of the active site structure and conformational states [34].

Materials and Reagents:

- Purified heme protein (e.g., Myoglobin, Hemoglobin, or a Cytochrome).

- Gas-tight IR cell with calcium fluoride or barium fluoride windows, transparent to IR light.

- Source of ligand gas (e.g., Carbon monoxide (CO) or Nitric oxide (NO) in an inert gas matrix).

- FTIR Spectrometer: Equipped with a high-sensitivity detector (e.g., MCT detector).

- Cryostat (for low-temperature studies): To trap intermediates by slowing down reaction kinetics [34].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Place the purified heme protein in the IR cell at a suitable concentration (e.g., 0.5-2 mM).

- For low-temperature studies, the sample is often prepared in a glycerol-containing buffer to form a clear glass upon freezing.

- Data Collection - Photolysis Difference Spectroscopy:

- Cool the sample to cryogenic temperatures (e.g., 4-100 K) to inhibit ligand rebinding.

- Collect a background IR spectrum of the ligand-bound state (e.g., Fe-CO).

- Photolyze the sample with a brief, intense laser pulse at a wavelength absorbed by the heme (e.g., ~500 nm) to break the Fe-ligand bond.

- Immediately collect a second IR spectrum.

- The difference spectrum (spectrum after photolysis minus spectrum before photolysis) reveals positive bands (from the photodissociated ligand) and negative bands (from the bound ligand) [34].

- Data Analysis:

- Identify the precise wavenumber (cm⁻¹) of the C-O or N-O stretch in the bound and unbound states.

- Compare the frequency shifts under different conditions (e.g., pH, mutation, allosteric effectors) to infer changes in the heme pocket's polarity and hydrogen-bonding network.

Data Interpretation: A shift in the vibrational frequency of the bound ligand indicates a change in the electron density on the heme iron or a change in the steric and electrostatic constraints imposed by the protein. This is a sensitive probe for how the protein matrix fine-tunes the reactivity of a prosthetic group.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Prosthetic Group Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) / Mercury Salts | Selective cleavage of covalent thioether bonds in c-type cytochromes to detach the heme prosthetic group [32]. |

| FTIR Spectrometer with Cryostat | High-sensitivity measurement of ligand-binding kinetics and active site environmental changes in heme proteins at cryogenic temperatures [34]. |

| Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂) IR Cells | Windows for IR spectroscopy that are transparent in the mid-IR range, allowing observation of ligand vibrational frequencies [34]. |

| Proteases (Trypsin, Pepsin) | Enzymatic digestion of the protein backbone while leaving covalent prosthetic group-peptide bonds intact for mass spectrometric analysis [32]. |

| MALDI-TOF / ESI Mass Spectrometer | Precise determination of the molecular weight of intact proteins and heme-bearing peptides to confirm covalent modification [32]. |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The central role of cofactors and prosthetic groups in enzyme catalysis makes them prime targets for pharmaceutical intervention. Understanding these components is critical for rational drug design.

Many enzymes essential for pathogen survival require specific cofactors. Drugs can be designed to mimic or interfere with these essential cofactors. For example, the anti-cancer drug methotrexate is a structural analog of the coenzyme dihydrofolate. It binds tightly to the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, inhibiting the synthesis of tetrahydrofolate, a coenzyme required for nucleotide synthesis, thereby halting rapid cell division [31]. Similarly, statin drugs inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol synthesis, by mimicking the enzyme's natural substrate and a portion of its coenzyme, HMG-CoA.

The knowledge of a enzyme's essential metal ion cofactor can also guide toxicology studies. Lead poisoning, for instance, exerts its toxic effects partly by displacing essential metal ions like Zn²⁺ and Fe²⁺ from their native prosthetic groups in critical enzymes, rendering them inactive.

Cofactors and prosthetic groups are indispensable for the vast catalytic network that underpins life. They are not mere accessories but fundamental components that empower enzymes to perform chemistry beyond the scope of amino acids alone. From enabling electron transfer and group transfer to stabilizing transition states and modulating protein conformation, their roles are diverse and critical. For researchers, a deep understanding of these partners is not just an academic exercise. It provides the foundational knowledge required to manipulate biochemical pathways, decipher disease mechanisms, and design powerful and specific therapeutic agents. The continued development of advanced experimental techniques for probing their structure and dynamics will undoubtedly yield further insights, driving innovation in biomedicine and biotechnology.

Enzymes orchestrate essential biochemical reactions with remarkable efficiency and specificity, primarily by lowering the activation energy barrier that impedes these processes. This catalytic proficiency originates from sophisticated interactions between enzyme structure and substrate, creating energy landscapes that favor reaction progression. Within these landscapes, enzymes stabilize high-energy transition states through precisely orchestrated molecular strategies. Recent structural biology and biophysics research has illuminated how distinct elements—from active site architecture to distal residue networks—collectively reshape energy profiles to accelerate chemical transformations. Understanding these mechanisms provides critical insights for therapeutic intervention and enzyme engineering, particularly as structural data reveal how mutations disrupt function in diseases like isovaleric acidemia and how directed evolution optimizes catalytic efficiency in designed enzymes.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Energy Landscape Alteration

Transition State Stabilization

The predominant mechanism by which enzymes lower activation energy involves the stabilization of the transition state structure. Unlike ground state binding, transition state stabilization disproportionately reduces the energy barrier between substrate and product. Enzymes achieve this through preorganized active sites that exhibit complementarity to the transition state geometry rather than the substrate ground state. This principle explains the remarkable rate enhancements—up to billions-fold—observed in biological catalysis. The energy required to reach this transition state is significantly reduced when the enzyme active site provides stabilizing interactions that are maximized at the reaction transition state rather than at the substrate binding stage.

Conformational Dynamics and Substate Sampling

Enzymes exist as ensembles of conformational substates that continuously interconvert, and this dynamic behavior plays a crucial role in catalytic efficiency. Research on de novo Kemp eliminases reveals that enzymes exhibit slow equilibria between active and inactive conformations [35]. Directed evolution optimizes these ensembles by progressively populating catalytically competent conformations while minimizing non-productive states. In evolved Kemp eliminase HG3.17, the population of the inactive conformational substate was reduced to just 5% under ambient conditions, compared to 25% in earlier variants [35]. This reshaping of the energy landscape ensures that the enzyme predominantly samples conformations primed for catalysis, effectively lowering the activation barrier by pre-organizing the catalytic apparatus.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Conformational State Populations in Kemp Eliminase Variants

| Enzyme Variant | % Inactive State (25°C) | % Inactive State (40°C) | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HG3 (Initial) | ~25% | >58% | Baseline |

| HG3.7 (Intermediate) | ~25% | ~58% | Intermediate improvement |

| HG3.17 (Evolved) | ~5% | ~42% | ~200-fold improvement |

Structural Determinants of Energy Barrier Reduction

Active Site Architecture and Chemical Mechanism

The arrangement of functional groups within enzyme active sites directly facilitates catalysis through multiple chemical strategies. The isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase (IVD) enzyme, which catalyzes the conversion of isovaleryl-CoA to 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA in leucine catabolism, exemplifies precise active site organization [36]. Structural analyses reveal that IVD contains a catalytic glutamate residue (E286) that abstracts α-hydrogen from the substrate, while an FAD cofactor stabilizes the transition state through electronic interactions [36]. The enzyme's active site architecture creates a specialized environment that preferentially stabilizes the reaction's transition state over either substrate or product, thereby lowering the activation energy barrier.

The spatial constraints of active sites also contribute significantly to substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency. IVD exhibits a "U-shaped" substrate channel with residues L127 and L290 forming a narrowed side-chain distance that creates a "bottleneck effect" [36]. This architecture selectively recognizes short-branched chain substrates while excluding longer chains due to steric hindrance, ensuring that only appropriate substrates enter the catalytic environment where transition state stabilization occurs.

Distal Mutations and Allosteric Influences

Residues distant from active sites profoundly impact catalytic efficiency by modulating structural dynamics and energy landscapes. In engineered Kemp eliminases, distal mutations enhance catalysis by facilitating substrate binding and product release through tuning structural dynamics to widen the active-site entrance and reorganize surface loops [22]. These distal residues exert their effects not by directly participating in chemistry, but by altering the conformational ensemble to favor states with improved access to the active site or enhanced transition state stabilization.

Molecular dynamics simulations of designed enzymes reveal that distal mutations can enable global conformational changes, including high-energy backbone rearrangements that cooperatively organize catalytic residues [35]. This long-range communication within enzyme structures demonstrates that catalysis is not solely governed by active site residues but emerges from integrated dynamics throughout the protein scaffold. The functional impact of distal mutations challenges traditional views of enzyme mechanisms and highlights the importance of considering global protein dynamics in understanding how enzymes lower activation barriers.

Table 2: Functional Classification of Enzyme Residues in Catalytic Optimization

| Residue Type | Location | Primary Function | Impact on Activation Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Residues | Active site | Direct chemical participation | Direct transition state stabilization |

| Second-Shell Residues | Surrounding active site | Active site organization | Indirect through precise positioning |

| Distal/Allosteric Residues | Remote from active site | Modulating conformational dynamics | Alters energy landscape sampling |

Methodological Approaches for Studying Enzyme Energy Landscapes

Structural Biology Techniques

X-ray crystallography provides atomic-resolution snapshots of enzyme structures in various states, revealing conformational changes associated with catalysis. Studies on IVD utilized cryo-EM structures at high resolutions (2.5-3.0 Å) to capture the enzyme in apo state and in complex with substrates (isovaleryl-CoA and butyryl-CoA) [36]. This approach revealed how substrate binding induces structural rearrangements that pre-organize the catalytic environment. Temperature-controlled crystallography has been particularly valuable for capturing transient conformational states, as demonstrated by experiments on HG3.17 at 70°C that simultaneously revealed both active and inactive conformations [35].

Kinetic and Biophysical Analyses

Stopped-flow kinetics enables monitoring of rapid enzymatic processes, including substrate binding and product release, on millisecond timescales. When applied to Kemp eliminase variants, this technique revealed distinct steps in transition state analogue binding, including conformational selection and induced-fit components [35]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy provides unparalleled insights into enzyme dynamics across multiple timescales. Backbone NMR assignments of HG3.17 revealed slow conformational exchange processes (k~10⁻³-10⁻⁴ s⁻¹) between active and inactive states, with temperature and pH dependence indicating thermodynamic parameters of these transitions [35].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry quantitatively characterizes the thermodynamics of substrate binding, revealing enthalpy-entropy compensation mechanisms that contribute to activation energy reduction. These biophysical approaches collectively enable researchers to reconstruct the complex energy landscapes that govern enzymatic catalysis.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for studying enzyme energy landscapes, integrating structural, kinetic, and dynamic approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Probing Catalytic Mechanisms

Protocol: Transition State Analogue Binding Studies

Objective: Quantify transition state stabilization energy through binding affinity measurements of transition state analogues.

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify enzyme variants using optimized purification protocols. For IVD studies, this involved obtaining homogenous tetrameric enzyme preparations suitable for biophysical analysis [36].

- Ligand Selection: Identify appropriate transition state analogues that mimic the geometry and electronic distribution of the actual transition state. For Kemp eliminases, 6-nitrobenzotriazole (6NBT) served as an effective transition state analogue [35].