Extremozymes: Discovering Novel Enzymes from Extremophiles for Biomedical and Industrial Applications

This article explores the rapidly advancing field of discovering novel enzymes, or extremozymes, from microorganisms that thrive in extreme environments.

Extremozymes: Discovering Novel Enzymes from Extremophiles for Biomedical and Industrial Applications

Abstract

This article explores the rapidly advancing field of discovering novel enzymes, or extremozymes, from microorganisms that thrive in extreme environments. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of the unique adaptations of extremophiles, modern discovery methods like functional metagenomics and computational mining, and strategies to overcome key challenges in cultivation and expression. The content synthesizes current research to highlight the significant potential of these robust biocatalysts in driving innovation across pharmaceuticals, industrial biotechnology, and bioremediation, with a forward-looking perspective on future research directions.

Life on the Edge: Understanding Extremophiles and Their Unique Enzymatic Toolkit

Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in environments characterized by extreme physical or geochemical conditions, habitats that were once considered incompatible with life [1] [2]. These remarkable organisms have redefined our understanding of life's limits and adaptability, inhabiting ecological niches from scorching hydrothermal vents and acidic lakes to frozen polar regions and hypersaline basins [3] [4]. The study of extremophiles provides critical insights into evolutionary biology, the origins of life on Earth, and the potential for life elsewhere in the universe [1] [5]. From a biotechnological perspective, extremophiles represent a largely untapped reservoir of novel enzymes, or "extremozymes," with unique properties that make them invaluable for industrial processes, molecular biology, and drug development [3] [5]. Their enzymes exhibit remarkable stability and functionality under extreme conditions that would denature most conventional proteins, offering tremendous potential for applications requiring high temperatures, extreme pH, high salinity, or other challenging parameters [1] [6]. This taxonomic framework outlines the classification of extremophiles based on their environmental preferences, describes their unique adaptive mechanisms, and details the experimental methodologies enabling the discovery of novel biocatalysts from these resilient organisms, all within the context of advancing extremophile enzyme research.

Extremophile Taxonomy and Environmental Classification

Extremophiles are classified based on the specific environmental parameters in which they exhibit optimal growth. These classifications are not mutually exclusive, and many organisms fall into multiple categories, being classified as polyextremophiles [2]. The table below provides a comprehensive taxonomy of major extremophile types, their environmental preferences, and representative examples.

Table 1: Taxonomic Classification of Extremophiles and Their Environmental Niches

| Extremophile Type | Optimal Growth Conditions | Representative Genera/Species | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophile | Temperatures > 45°C [2] | Thermus aquaticus [5] | Bacteria |

| Hyperthermophile | Temperatures > 80°C [7] [2] | Pyrolobus fumarii, Methanopyrus kandleri [2] | Archaea |

| Psychrophile | Temperatures < 15°C [7] [2] | Psychrobacter sp. [1] [4] | Bacteria |

| Acidophile | pH < 5 [7] | Picrophilus oshimae (pH < 1) [2] | Archaea |

| Alkaliphile | pH > 9 [7] [2] | Natronobacterium [2] | Archaea |

| Halophile | Salt concentrations > 50 g/L [2] | Halobacteriaceae, Dunaliella salina [1] [2] | Archaea, Eukarya |

| Piezophile (Barophile) | High hydrostatic pressure (> 10 MPa) [2] | Pyrococcus species from Mariana Trench [2] | Archaea |

| Radioresistant | High ionizing radiation [2] | Deinococcus radiodurans [3] [2] | Bacteria |

| Xerophile | Low water activity (< 0.8) [2] | Chroococcidiopsis from deserts [2] | Bacteria |

Prokaryotes, including bacteria and archaea, represent the most common and diverse group of extremophiles, largely due to their simpler cellular structure, genetic flexibility, and rapid adaptive capabilities [1] [5]. However, certain extremophilic eukaryotes, including fungi, algae, and even some multicellular organisms, also exhibit unique adaptations to extreme conditions [1]. The environmental factors shaping these classifications impose intense selective pressures, driving the evolution of specialized structural, biochemical, and genomic adaptations that enable survival [5].

Genomic and Molecular Adaptation Mechanisms

Genomic Signatures of Environmental Adaptation

Recent advances in genomic analysis have revealed that adaptation to extreme environments imprints a discernible environmental component in the genomic signature of microbial extremophiles. Machine learning analyses of k-mer frequency vectors (genomic signatures) from approximately 700 extremophile genomes have demonstrated that environmental conditions such as extreme temperature and pH can be classified with medium to high accuracy ((3 \leq k \leq 6)), independent of taxonomy [7]. This suggests convergent evolution at the genomic level in response to similar environmental pressures.

Specific genomic adaptations include:

- Nucleotide Composition Bias: Thermophiles often display higher G+C content in their tRNA and DNA, contributing to nucleic acid stability at high temperatures [7] [4].

- Codon Usage Patterns: Selective pressure favors codons that enhance translation efficiency and protein folding under extreme conditions [7].

- Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT): This process enables extremophiles to acquire advantageous genes from other organisms, rapidly conferring traits like stress resistance [5]. The radiophile Deinococcus radiodurans, for instance, possesses the PprA DNA protection protein that aids in repair of radiation-induced damage [5].

Proteomic and Enzymatic Adaptations

At the proteomic level, extremophiles exhibit distinct amino acid compositional biases that stabilize protein structure under extreme conditions. The following table summarizes key adaptive strategies across different extremophile types.

Table 2: Molecular Adaptation Mechanisms in Extremophiles

| Extremophile Type | Protein Adaptations | Membrane Adaptations | Specialized Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophiles | Increased hydrophobic interactions, salt bridges, disulfide bonds; shorter loops; more compact structures [4] | Ether-linked lipids in Archaea; saturated fatty acids [4] | Heat-shock proteins; chaperonins [1] |

| Psychrophiles | Increased protein flexibility; more glycine residues; fewer salt bridges; reduced hydrophobic cores [4] | Increased unsaturated fatty acids to maintain fluidity [4] | Antifreeze proteins (AFPs) [1] |

| Halophiles | Acidic proteome with high surface glutamate and aspartate residues for hydration shell formation [1] | Production of compatible solutes (e.g., glycerol, ectoine) [1] | |

| Acidophiles | Reinforced protein surface structures; proton pumps [1] | Highly impermeable membranes with tetraether lipids [1] | Buffering molecules |

| Piezophiles | Reduced protein cavity volume; increased small amino acids [1] | Increased unsaturated fatty acids to maintain membrane fluidity [4] | Piezolyte proteins |

These molecular adaptations enable extremozymes to maintain structural integrity and catalytic functionality under conditions that would rapidly inactivate conventional enzymes, making them particularly valuable for industrial and pharmaceutical applications [1] [3].

Experimental Methodologies for Extremophile Enzyme Discovery

Sampling, Isolation, and Cultivation Techniques

The discovery of novel enzymes from extremophiles begins with the careful collection of samples from extreme environments. Specific methodologies vary depending on the habitat.

Table 3: Sampling Protocols for Extreme Environments

| Environment | Sampling Method | Preservation & Transport | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Springs & Geothermal Vents | Sterilized temperature-resistant samplers; in situ temperature and pH measurement [4] | Anaerobic chambers; maintenance of source temperature [4] | Rapid processing to prevent oxygen exposure for anaerobes |

| Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents | Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) with specialized samplers; pressure-retaining vessels [4] | Pressurized containers to simulate in situ hydrostatic pressure [4] | Mimicking deep-sea pressure (piezophily) is critical for viability |

| Polar Regions & Sea Ice | Ice corers; sterile collection of cryoconite [4] [8] | Maintenance at sub-zero temperatures; avoidance of freeze-thaw cycles [4] | Low-nutrient conditions require specific cultivation strategies |

| Hypersaline Lakes | Filtration and concentration of water samples; sediment cores [1] | Avoidance of dilution shock for extreme halophiles | |

| Acidic Mine Drainage | Filtration of water; collection of biofilms [3] | pH stabilization during transport |

Following sample collection, cultivation-dependent methods are employed to isolate extremophiles. These techniques are crucial for studying microbial physiology, metabolic pathways, and environmental interactions under controlled conditions [4]. However, it is estimated that >99% of microorganisms cannot be cultivated with standard techniques, necessitating the development of specialized culturing approaches such as:

- Simulated Natural Environments: Media and incubation conditions that closely mimic the chemical and physical parameters of the source environment (e.g., high salt, temperature, pressure) [4].

- Co-culture Systems: Recognizing that some extremophiles require symbiotic relationships or signals from other organisms [3].

- Long-Term Incubation: Extended incubation periods to accommodate potentially very slow growth rates under nutrient limitation [4].

Culture-Independent Metagenomic Approaches

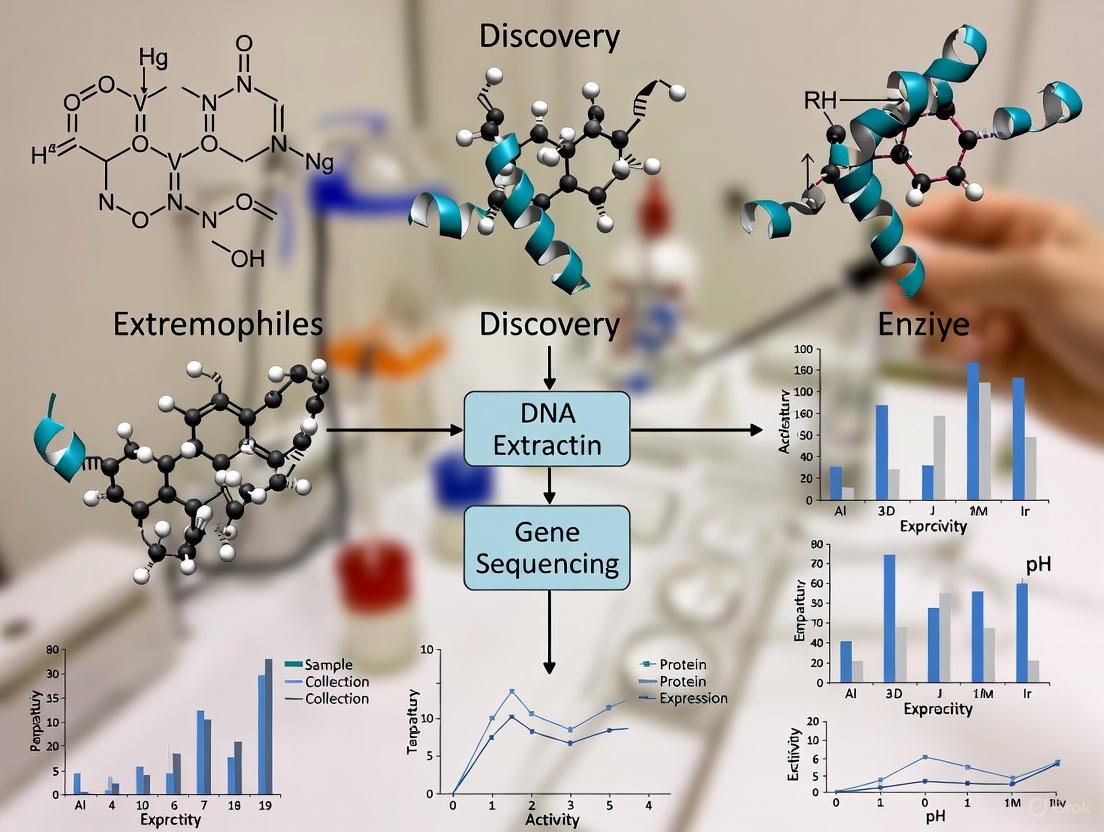

Given the challenges of cultivation, culture-independent metagenomic techniques have become cornerstone methodologies for exploring the genetic potential of extremophile communities [3] [4]. The standard workflow for metagenome-guided enzyme discovery is depicted below.

Key Steps in Metagenomic Analysis:

DNA Extraction: Direct lysis of cells in the environmental sample, followed by purification of high-molecular-weight DNA. This step is critical for capturing genetic material from the entire microbial community, including uncultivable members [4].

Sequencing and Assembly: Next-generation sequencing (e.g., Illumina, PacBio) generates vast numbers of short reads, which are computationally assembled into longer contiguous sequences (contigs) and binned into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) [7] [4].

Gene Prediction and Annotation: Computational tools (e.g., Prokka, MG-RAST) identify open reading frames (ORFs) within contigs and MAGs. Predicted genes are functionally annotated by comparing their sequences to curated databases (e.g., Pfam, CAZy, KEGG) to identify putative enzymes [3] [6].

Target Gene Identification: Genes of biotechnological interest (e.g., polymerases, proteases, lipases) are prioritized based on sequence homology, phylogenetic origin, and the presence of specific protein domains associated with stability or function under extreme conditions [3].

Functional Screening and Heterologous Expression

The identification of putative enzyme genes is followed by functional validation. Two primary approaches are used:

Function-Based Screening: Environmental DNA is cloned into expression vectors to create metagenomic libraries, which are then introduced into a cultivable host bacterium (e.g., Escherichia coli). These libraries are screened under selective conditions (e.g., high temperature, specific pH, or the presence of a target substrate) to identify clones exhibiting the desired enzymatic activity [8].

Sequence-Based Screening: Putative enzyme genes identified through metagenomic annotation are synthesized or PCR-amplified and cloned into expression vectors for heterologous production [3] [8]. This approach was successfully used for a novel type II L-asparaginase from a halotolerant Bacillus subtilis strain, which was expressed in E. coli and shown to have remarkable thermal stability (optimal activity at pH 9.0 and 60°C) [8].

For both approaches, the choice of heterologous host is critical. Standard hosts like E. coli may lack the cellular machinery to correctly fold or post-translationally modify enzymes from distantly related extremophiles. As alternatives, alternative mesophilic hosts (e.g., Bacillus subtilis) or engineered extremophilic hosts are increasingly being developed [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental workflows in extremophile research rely on specialized reagents and materials. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Extremophile Enzyme Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Growth Media | Cultivation of extremophiles under simulated natural conditions. | Anaerobic media for deep-sea vent organisms; high-salt media for halophiles; low-nutrient media for oligotrophs [4]. |

| Pressure-Retaining Vessels | Cultivation and sampling of piezophiles from deep-sea environments. | Critical for maintaining organism viability and enzyme activity post-sampling [4]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits (Environmental) | Lysis and purification of high-quality metagenomic DNA from complex samples. | Must be effective for diverse cell wall types (e.g., Gram-positive, Archaea) and resistant to inhibitors [4]. |

| PCR Reagents & Thermostable Polymerases | Amplification of target genes from metagenomic DNA or isolates. | Taq polymerase (from Thermus aquaticus) [5] and Pfu polymerase (from Pyrococcus furiosus) [5] are themselves extremozymes that revolutionized molecular biology. |

| Cloning & Expression Systems | Heterologous production of target extremozymes. | Vectors with strong, inducible promoters (e.g., pET system for E. coli); specialized hosts for difficult-to-express proteins [3] [8]. |

| Activity Assay Reagents | Functional characterization of purified enzymes under various conditions. | Chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates; pH buffers for a broad range (e.g., pH 0-11); additives for testing stability (e.g., salts, detergents, organic solvents) [8]. |

The systematic taxonomy of extremophiles provides an essential framework for targeting the discovery of novel enzymes with exceptional stability and activity. The convergence of traditional microbiology with advanced genomic, metagenomic, and synthetic biology tools is rapidly accelerating the pace of discovery from these resilient organisms [3] [6]. The continued exploration of Earth's most extreme environments, coupled with increasingly sophisticated bioinformatic and functional screening platforms, promises to unlock a wealth of novel extremozymes. These enzymes hold immense potential to address global challenges, driving innovation in industrial biocatalysis, pharmaceutical development, and the transition toward a sustainable bio-based economy [1] [3] [6].

Extremozymes are enzymes produced by extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme environments—exhibiting exceptional stability and catalytic efficiency under harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, pH, salinity, and pressure. These enzymes have redefined our understanding of life's resilience and have become a major focus of research due to their profound applications in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and industrial processes. Through unique structural adaptations, including specialized amino acid compositions, charged surfaces, and robust molecular interactions, extremozymes maintain structural integrity and functionality where conventional enzymes fail. This whitepaper explores the molecular mechanisms underlying extremozyme stability, details advanced methodologies for their discovery and engineering, and frames their significance within the broader context of discovering novel enzymes from extremophile research, highlighting their potential to drive innovations in drug development and sustainable technologies.

Extremophiles are remarkable organisms capable of growing and developing in extreme environments that were once considered incompatible with life, including volcanic areas, polar regions, deep seas, salt and acidic lakes, and deserts [1]. The study of these organisms has revolutionized our understanding of life's limits and has become a major focus of research due to their unique lifestyles and adaptation capabilities [1]. These environments closely resemble early Earth's conditions, and studies suggest that extremophiles, particularly hyperthermophiles, cluster near the universal ancestors on the tree of life, making them crucial for understanding life's origins [1] [3].

The adaptive strengths of extremophiles are manifested through specialized proteins and enzymes known as extremozymes [1]. These enzymes are characterized by their high stability and functionality under extreme conditions, making them valuable for in vitro molecular processes requiring high temperatures or other challenging parameters [1]. The discovery of thermoresistant enzymes from extremophiles, such as Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus, has been instrumental in developing fundamental techniques like PCR, showcasing their transformative potential in molecular biology and diagnostics [1] [3]. Extremophiles span both prokaryotic and eukaryotic domains of life, with prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) representing the most common and diverse group due to their simpler cellular structure, genetic flexibility, and adaptability [1].

Molecular Adaptation Mechanisms of Extremozymes

Extremozymes have evolved sophisticated structural and mechanistic adaptations to maintain stability and activity under physicochemical extremes that would typically denature proteins and disrupt cellular functions in mesophilic organisms. These adaptations are often convergent, arising across different taxonomic groups facing similar environmental challenges [7].

Structural Stabilization Strategies

The structural integrity of extremozymes under extreme conditions is maintained through a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors:

- Amino Acid Composition and Protein Folding: Thermophilic and hyperthermophilic enzymes exhibit a higher prevalence of charged residues (e.g., lysine and arginine) and a lower frequency of thermolabile residues like cysteine and asparagine. This promotes the formation of intramolecular ion pairs (salt bridges) and dense hydrophobic cores, conferring rigidity and resistance to thermal unfolding [1] [7]. Psychrophilic (cold-adapted) enzymes, in contrast, display greater structural flexibility achieved through a reduction in proline and arginine residues in loops, fewer salt bridges, and a less hydrophobic core, allowing catalytic function at low thermal energy levels [1].

- Surface Charge and Solvation: Halophilic (salt-loving) enzymes possess a high surface density of acidic residues (aspartate and glutamate), which facilitates coordinated hydration shell formation in high-salt environments, preventing aggregation and precipitation through self-repulsion of the negatively charged surfaces [3].

- Oligomerization and Complex Formation: Many extremozymes form stable oligomeric complexes and higher-order structures. This subunit interaction provides increased structural stability, particularly for enzymes operating under high pressure (piezophiles) or high temperatures [1].

Genomic and Proteomic Signatures

Recent machine learning analyses of extremophile genomes have identified a discernible environmental component in their genomic signatures, in addition to the strong phylogenetic signal [7]. For instance, adaptations to extreme temperatures and pH imprint specific patterns in k-mer frequency profiles (short DNA sequences of length k) within genomic DNA. Studies using supervised learning achieved medium to high accuracy in classifying microbial genomes based on environmental categories (e.g., thermophile vs. psychrophile) using k-mer frequencies for values of 3 ≤ k ≤ 6 [7]. This suggests that the selective pressures of extreme environments have led to convergent evolution at the nucleotide level, influencing codon usage patterns and amino acid compositional biases that are reflected in the resulting extremozyme structures [7].

Table 1: Key Structural Adaptations in Different Extremozyme Classes

| Extremozyme Class | Primary Environmental Challenge | Core Structural Adaptations | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermozymes (Thermophiles/Hyperthermophiles) | High temperature (>45-80°C; >80°C) [7] | Increased intramolecular ion pairs (salt bridges); dense hydrophobic packing; reduced thermolabile residues; higher G+C content in coding DNA [1] [7] | Resistance to thermal denaturation and unfolding; high melting temperature (Tm) |

| Psychrozymes (Psychrophiles) | Low temperature (<20°C) [7] | Reduced proline/arginine in loops; fewer salt bridges/aromatic interactions; increased surface hydrophilicity [1] | Enhanced molecular flexibility and catalytic efficiency at low kinetic energy |

| Halozymes (Halophiles) | High salinity (>3.5% NaCl) [1] | Abundant acidic surface residues (Asp, Glu); low lysine content; coordinated hydration shells [3] | Solubility and prevention of aggregation in high ionic strength milieus |

| Piezozymes (Piezophiles) | High pressure (e.g., deep sea) | Stabilized oligomeric interfaces; specific volume-reducing substitutions [1] | Resistance to pressure-induced denaturation and volume changes |

| Acidozymes/Alkalizymes (Acidophiles/Alkaliphiles) | Extreme pH (<5 / >9) [7] | Stable active site protonation states; charged surface adaptations; acid-/base-stable bonds [1] | Maintenance of active site chemistry and global structure at extreme pH |

Methodologies for Discovering and Engineering Novel Extremozymes

The exploration of extremophiles has gained significant momentum due to advancements in genetic sequencing, DNA analysis techniques, and bioinformatics [1] [9]. The following experimental and computational workflows are central to the discovery and optimization of novel extremozymes.

Discovery Workflows: From Metagenomics to Function

Much of the microbial diversity in extreme environments remains unculturable in laboratory settings. Therefore, metagenomics—the direct analysis of genetic material recovered from environmental samples—has become a cornerstone of extremozyme discovery [9] [3].

Diagram 1: Metagenomic discovery pipeline for novel extremozymes.

The process involves several critical steps:

- Sample Collection and DNA Extraction: Environmental samples are collected from extreme habitats (e.g., hot springs, deep-sea vents, acidic mines). Total community DNA is extracted, bypassing the need for cultivation [3].

- Sequencing and Assembly: Shotgun sequencing generates millions of DNA fragments, which are computationally assembled into contigs and scaffolds to reconstruct genomic fragments from the microbial community [9].

- Gene Mining and Annotation: Assembled sequences are scanned for open reading frames (ORFs) and compared against databases to identify putative enzyme-encoding genes. A significant challenge is that 20-40% of predicted genes from metagenomes cannot be annotated and are of unknown function, representing a vast reservoir of potential novelty [9].

- Heterologous Expression and Screening: Putative extremozyme genes are cloned and expressed in suitable laboratory hosts (e.g., E. coli, Thermus thermophilus for thermozymes). The expressed proteins are then screened for activity under simulated extreme conditions using chromogenic substrates or other functional assays [9].

Engineering and Optimization with Deep Learning

Wild-type extremozymes often require optimization for industrial or therapeutic applications. Directed evolution has been a successful laboratory method, but it is time-consuming and costly [10]. Computational rational design offers a complementary approach, and deep learning (DL) models are now revolutionizing the field.

Diagram 2: Deep learning workflow for enzyme engineering.

DL models like CataPro predict enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km, kcat/Km) by using embeddings from pre-trained protein language models (e.g., ProtT5) for enzyme sequences and molecular fingerprints for substrates [10]. This approach demonstrates superior accuracy and generalization ability compared to previous models. In a representative study, combining CataPro with traditional methods identified an enzyme (SsCSO) with 19.53 times increased activity compared to an initial enzyme, and subsequent engineering improved its activity by a further 3.34 times [10]. This highlights the high potential of DL as an effective tool for future extremozyme discovery and modification.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Extremozyme Discovery

| Reagent / Tool / Method | Function in R&D | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic Libraries (plasmid, fosmid, cosmid) | Cloning and maintaining environmental DNA from unculturable extremophiles for functional screening [9] | Discovery of novel lipases and proteases from deep-sea vent microbiomes [9] |

| Specialized Expression Hosts (e.g., Thermus thermophilus) | Overproduction of thermostable proteins that cannot be expressed in mesophilic systems like E. coli [9] | High-yield production of hyperthermostable polymerases [9] |

| Chromogenic Hydrolase Substrates | Enable high-throughput functional screening of metagenomic libraries for enzyme activity (e.g., proteases, esterases) [9] | Identification of active clones based on color change in agar plates |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models (e.g., ProtT5) | Generate informative numerical representations (embeddings) of enzyme sequences for deep learning models [10] | Used as input features in CataPro for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat/Km) [10] |

| Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys) | Numerical representation of substrate chemical structure for computational analysis [10] | Used alongside enzyme embeddings in CataPro to model enzyme-substrate interactions [10] |

Applications and Future Directions in Drug Development and Biotechnology

Extremozymes offer immense potential across numerous industries due to their robustness and novel mechanisms of action. In the pharmaceutical sector, their unique properties are being leveraged to overcome limitations of conventional enzymes.

- Therapeutics and Drug Synthesis: Extremozymes are used as therapeutic agents and catalysts for synthesizing chiral pharmaceutical intermediates. For example, L-asparaginase from halotolerant bacteria is used in cancer treatment, while thermostable transaminases are employed in the biosynthesis of chiral amines with high enantioselectivity, which is crucial for drug safety and efficacy [3] [10].

- Combatting Antibiotic Resistance: Extremophiles are a promising source of novel antimicrobial peptides (e.g., Halocins) that exhibit potent activity against drug-resistant pathogens through novel mechanisms, such as pore-forming mechanisms or targeting lipid II in cell wall synthesis, potentially bypassing existing resistance mechanisms [3].

- Diagnostics and Molecular Biology: Thermostable DNA polymerases like Taq polymerase are indispensable for PCR-based diagnostics. Other extremozymes, such as nucleases and ligases with unique fidelity and stability profiles, are continually being developed for advanced molecular diagnostics and biosensing [1] [3].

The future of extremophile research is intrinsically linked to overcoming current challenges, such as the difficulty of cultivating many extremophiles and scaling up extremozyme production [9] [3]. The integration of multi-omics approaches, advanced cultivation methods, and powerful AI-driven tools like CataPro will accelerate the discovery and engineering of next-generation extremozymes. These innovations promise to provide innovative solutions to global challenges in healthcare, including the development of new antibiotics, more efficient biocatalysts for green chemistry, and stable enzymatic therapeutics [9] [3] [10].

The pursuit of novel enzymes from extremophiles represents a frontier in biotechnology, driven by the need for more robust and efficient industrial biocatalysts. Extremozymes, enzymes derived from microorganisms that thrive in extreme environments, have emerged as cornerstones for biocatalysis under conditions where conventional mesophilic enzymes fail [11] [12]. These enzymes are not merely stable but are optimally active under extreme temperatures, pH, salinity, and pressure, offering unique catalytic properties that are often unattainable through protein engineering of mesophilic counterparts alone [13] [14]. The global enzymes market, expected to reach $14.5 billion by 2027, underscores the economic and industrial significance of these biological catalysts [14]. Framed within the broader context of novel enzyme discovery, this review details the major classes of industrially relevant extremozymes, their functional adaptations, and the advanced methodologies employed to harness their potential for transformative biotechnological applications.

Major Classes of Industrially Relevant Extremozymes

Extremophiles produce a diverse array of enzymes tailored to their specific environmental niches. The table below summarizes the key classes, their sources, and industrial applications.

Table 1: Major Classes of Industrially Relevant Extremozymes

| Extremozyme Class | Extremophile Source | Key Industrial Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Amylases [11] [15] | Thermophiles, Psychrophiles, Acidophiles, Alkaliphiles [11] | Starch processing, sugar syrups production, gluten-free and low-acrylamide foods [11] |

| Proteases [11] [15] | Thermophiles, Halophiles, Alkaliphiles [11] | Detergents, dairy processing, predigested foods (e.g., baby formulae) [11] |

| Lipases [11] [15] | Thermophiles, Psychrophiles, Halophiles [11] | Detergents, dairy flavoring, trans-fat reduction [11] |

| Laccases [11] [14] | Thermoalkaliphiles [14] | Cellulose pulp bleaching, textile dye decolorization, bioremediation [11] [13] |

| β-Galactosidases [16] | Thermophiles (e.g., from hydrothermal vents) [16] | Lactose-free dairy products [11] |

| Cellulases [13] [15] | Thermophiles, Acidophiles [11] | Biomass conversion, biofuel production [13] |

| Xylanases [11] [13] | Thermophiles [11] | Pulp bleaching in paper industry, bread quality improvement [11] [13] |

| Pullulanases [11] [15] | Thermophiles [11] | Starch saccharification, production of sweeteners [11] |

The unique properties of extremozymes are a direct result of structural adaptations to their hostile habitats. Psychrophilic enzymes, for instance, exhibit increased structural flexibility that allows for high catalytic efficiency at low temperatures, often accompanied by thermal lability [12]. In contrast, thermophilic enzymes display superior rigidity through increased ionic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and more hydrophobic cores, which prevent unfolding at high temperatures [13] [12]. Halophilic enzymes possess a high surface density of acidic amino acids, which facilitates solvation and function in low-water-activity, high-salt environments [17]. These intrinsic properties make extremozymes ideal for industrial processes that involve harsh conditions, thereby enhancing reaction rates, reducing contamination risk, and minimizing the need for costly cooling or heating steps [12].

Discovery and Development Workflow for Novel Extremozymes

The journey from an environmental sample to a commercially viable extremozyme involves a multi-stage pipeline, integrating both culture-dependent and culture-independent strategies.

Diagram 1: Roadmap for novel extremozyme discovery and production, integrating culture-dependent and independent approaches.

Phase 1: Discovery and Screening

The initial discovery phase relies on two complementary approaches to access the vast enzymatic potential of extremophiles.

3.1.1 Culture-Dependent Functional Screening This traditional method involves cultivating extremophiles from environmental samples under selective pressures that mimic the target industrial condition [14]. Key steps include:

- Sample Collection: Sourcing from extreme environments like hot springs, deep-sea vents, polar regions, and acidic mines [11] [3].

- Selective Enrichment: Inoculating samples in culture media with defined parameters (e.g., high temperature, extreme pH, high salinity) to favor the growth of desired extremophiles [14].

- Activity-Based Screening: Isolating pure strains and screening for enzyme activity using plate-based assays. Examples include:

- Laccase Screening: Using guaiacol-containing agar plates, where positive colonies produce a brown halo [14].

- Catalase Screening: Enriching for antioxidant producers (e.g., from Antarctica) via exposure to UV-C radiation [14].

- Amine-Transaminase Screening: Using media supplemented with α-methylbenzylamine (MBA) as an enzyme inducer [14].

3.1.2 Culture-Independent Metagenomic Screening Given that an estimated 99% of microorganisms are uncultivable in the laboratory, this approach bypasses the need for cultivation, providing access to the "microbial dark matter" [13].

- Metagenomic Library Construction: Direct extraction and cloning of total environmental DNA into a cultivable host [11] [16].

- Sequence-Based Screening: Identification of target genes using conserved sequence motifs, hybridization with specific probes, or PCR with degenerate primers [11].

- Function-Based Screening: Expression of metagenomic DNA in a host like E. coli and screening for desired enzymatic activity, allowing discovery of completely novel sequences [11] [13].

Phase 2: Development and Production

Once a promising enzyme is identified, the focus shifts to its scalable production.

- Gene Cloning and Recombinant Expression: The target gene is cloned and expressed in a suitable heterologous host, typically E. coli [14]. Strategies include codon optimization and co-expression of molecular chaperones to improve the yield and solubility of recombinant extremozymes [13].

- Biochemical Characterization: The purified recombinant enzyme is rigorously tested to determine its optimal pH, temperature, stability, kinetic parameters, and tolerance to solvents and inhibitors [14].

- Scale-Up and Downstream Processing: The fermentation and purification processes are optimized for large-scale production, culminating in a standardized, commercial enzyme product [14].

Experimental Protocols for Key Extremozymes

Detailed methodologies are critical for the reproducible discovery and characterization of novel extremozymes. The following table outlines specific experimental protocols.

Table 2: Detailed Experimental Protocols for Extremozyme Discovery and Characterization

| Experimental Objective | Detailed Protocol & Conditions | Key Reagents & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Screening for Psychrotolerant Catalase [14] | 1. Sample Source: Elephant Island, Antarctica.2. Enrichment: Cultivate at 8°C, pH 6.5 for up to 2 weeks.3. Selective Pressure: Expose cultures to UV-C radiation for 2 hours to enrich microorganisms with robust antioxidant defenses.4. Isolation: Serial dilution and spread-plating until pure isolates are obtained. | - Culture media for psychrotrophs- UV-C lamp- Antioxidant assay kits |

| Screening for Thermoalkaliphilic Laccase [14] | 1. Sample Source: Geothermal site.2. Enrichment: Cultivate at 50°C, pH 8.0 with lignin as an enzyme inducer.3. Activity Screening: Plate on agar containing 0.5 mM guaiacol. Positive colonies develop a brown color due to guaiacol oxidation.4. Identification: Select and purify brown-haloed colonies. | - Lignin- Guaiacol- Thermostable alkaline buffers |

| Screening for Thermophilic Amine-Transaminase [14] | 1. Sample Source: Fumaroles in Whalers Bay, Antarctica.2. Enrichment: Cultivate at 50°C, pH 7.6 for 24 hours.3. Enzyme Induction: Supplement media with 10 mM α-methylbenzylamine (MBA).4. Isolation: Use serial dilution-to-extinction techniques for purification. | - α-Methylbenzylamine (MBA)- Specific amine assay reagents |

| Metagenomic Screening for β-Galactosidase [16] | 1. DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA directly from environmental samples (e.g., deep-sea hydrothermal vents).2. Computational Pipeline: Apply a bioinformatic pipeline for sustainable enzyme discovery that integrates sequence analysis and structural prediction.3. Gene Synthesis: Candidates are codon-optimized and synthesized de novo.4. Heterologous Expression & Validation: Express in E. coli and test for activity in vitro. | - Metagenomic DNA extraction kits- Bioinformatics software (e.g., for structural prediction)- Synthetic gene services |

| Biochemical Characterization of a Recombinant Enzyme [14] | 1. Expression: Heterologous expression in E. coli with IPTG induction.2. Cell Lysis: Sonication (e.g., ten 15-second bursts).3. Purification: Heat treatment (for thermophilic enzymes) followed by column chromatography.4. Activity Assays: Measure enzyme activity across a range of temperatures, pH, and in the presence of metal ions/reducing agents. | - IPTG- Sonication equipment- Chromatography systems (e.g., FPLC)- Spectrophotometer for activity assays |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental workflow for extremozyme research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Extremozyme Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Culture Media | Enriches for specific extremophiles from environmental samples by simulating extreme conditions. | Media for thermophiles (50-80°C), psychrophiles (≤15°C), alkaliphiles (pH >9), acidophiles (pH <5), halophiles (high NaCl) [14]. |

| Enzyme Activity Indicators | Allows visual or spectroscopic detection of specific enzyme activities in functional screenings. | Guaiacol (for laccases), starch-iodine test (for amylases), chromogenic substrates (for proteases, lipases) [11] [14]. |

| Heterologous Expression System | Enables high-yield production of recombinant extremozymes for characterization and application. | Host: E. coli BL21(DE3) is common.Vector: IPTG-inducible expression vectors (e.g., pET series).Consideration: Avoid patented vectors/tags for commercial freedom [14]. |

| Metagenomic Sequencing & Bioinformatics Tools | For culture-independent discovery and analysis of novel enzyme genes from environmental DNA. | Sequencing: Illumina MiSeq platform.Bioinformatics: Specialized pipelines for gene identification, annotation, and structural prediction [16] [14]. |

| Chromatography Systems | Purifies recombinant enzymes from cell lysates or culture supernatants for biochemical studies. | Affinity, ion-exchange, and size-exclusion chromatography are standard. Heat treatment is a simple first step for thermostable enzymes [14]. |

The systematic exploration of extremophiles and their enzymes is pivotal to the ongoing discovery of novel biocatalysts. Extremozymes such as amylases, proteases, lipases, and laccases, with their exceptional stability and activity under non-conventional conditions, are already reshaping industrial bioprocesses. The continued integration of culture-dependent functional screening with powerful culture-independent metagenomic and computational approaches promises to unlock the vast potential of the uncultured microbial majority [11] [13] [16]. As genomics, protein engineering, and fermentation technologies advance, the pipeline from the isolation of a novel extremophile to the commercialization of a robust extremozyme will become increasingly efficient. This journey not only fuels industrial innovation but also deepens our fundamental understanding of life's remarkable adaptability.

Extremophile Habitats as Unexplored Reservoirs of Biodiversity

The study of extremophiles—organisms that thrive in conditions once considered incompatible with life—has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of the limits of biology and evolution [3]. These resilient organisms, encompassing archaea, bacteria, and microbial eukaryotes, inhabit Earth's most inhospitable environments, from scorching hydrothermal vents and hyperacidic lakes to polar ice sheets and hypersaline basins [3] [18]. Their existence challenges conventional biogeochemical paradigms and positions extreme environments as significant reservoirs of undiscovered biodiversity [19].

For researchers in enzyme discovery and drug development, extremophiles represent a frontier for bioprospecting. The unique evolutionary pressures of extreme environments have selected for novel biochemical pathways, resulting in the production of stable, bioactive compounds and robust enzymes (extremozymes) with exceptional properties [3] [20]. These molecules often exhibit thermostability, acid/alkali tolerance, and unique mechanistic actions that are highly desirable for industrial biocatalysis and pharmaceutical development [20]. This whitepaper synthesizes current methodologies and discoveries to guide ongoing research into these unparalleled biological resources.

Classification of Extremophile Habitats and Microbial Diversity

Extremophiles are systematically classified based on the specific physicochemical parameters of their habitats. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of major extremophile types, their habitats, and key survival adaptations.

Table 1: Classification of Extremophiles, Their Habitats, and Adaptive Mechanisms

| Extremophile Type | Defining Environmental Condition | Representative Habitats | Key Survival Adaptations | Notable Microbial Taxa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophile | High temperature (45-122°C) [21] [20] | Hydrothermal vents, geothermal springs [21] | Thermostable enzymes (extremozymes), heat-shock proteins [3] | Methanopyrus kandleri, Pyrolobus fumarii, Sulfolobus solfataricus [21] [20] |

| Psychrophile | Freezing temperatures (down to -20°C) [18] | Polar ice sheets, sea ice, permafrost [19] | Antifreeze proteins, cold-active enzymes, fluid cell membranes [3] | Fragilariopsis cylindrus, Cladosporium herbarum [18] |

| Acidophile | Low pH (<3) [18] | Acid mine drainage, volcanic springs | Proton-pumping mechanisms, acid-stable membrane lipids [3] | Galdieria sulphuraria (alga) [18] |

| Alkaliphile | High pH (>9) [20] | Soda lakes, alkaline soils | Reverse transmembrane potential, alkaliphilic enzymes [20] | Bacillus subtilis CH11 [19] |

| Halophile | High salinity (up to saturation) [3] | Salt flats, salterns, hypersaline lakes | Osmoprotectants (e.g., compatible solutes), halophilic proteins [3] | Halotolerant Bacillus species [19] |

| Piezophile | High pressure (up to 110 MPa) [3] | Deep-sea trenches, oceanic sediments | Pressure-resistant membrane fluidity, specialized molecular chaperones [3] | Uncultured microbial "dark matter" [3] |

| Radioresistant | High ionizing radiation [3] | Nuclear waste sites, deserts | Efficient DNA repair mechanisms, melanin production [3] | Deinococcus radiodurans, Cladosporium chernobylensis [3] |

The exploration of these habitats has revealed remarkable examples of microbial ingenuity. In deep-sea hydrothermal vents, microorganisms such as Methanopyrus kandleri thrive on chimney walls at temperatures up to 122°C, harvesting energy from hydrogen gas and releasing methane via methanogenesis [21]. Conversely, in the cryosphere, the diatom Fragilariopsis cylindrus can grow at temperatures as low as -20°C [18]. Beyond prokaryotes, microbial eukaryotes (protists) demonstrate significant adaptability, with lineages like Echinamoebida and Heterolobosea displaying impressive thermophily, and algae such as Cyanidioschyzon merolae tolerating temperatures up to 60°C [18].

Methodological Framework for Discovery and Characterization

Sampling and Cultivation Strategies

Accessing and studying extremophile communities requires specialized techniques to preserve their delicate integrity and enable laboratory analysis.

- Sampling Protocols: The initial step involves collecting biomass or environmental samples (water, sediment, rock) while maintaining in situ conditions. For deep-sea hydrothermal vents, this requires remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to collect plume fluids and chimney structures [21]. For subsurface or cave environments, sterile coring devices are essential to avoid contamination [19]. A critical consideration is the rapid stabilization of parameters like pressure and temperature post-sampling to prevent cellular stress or death [18].

- Cultivation Techniques: Many extremophiles are uncultivable using standard laboratory media, necessitating specialized approaches. These include:

- Simulated In Situ Conditions: Replicating the native physicochemical environment (pH, temperature, pressure, salinity) in bioreactors [19].

- Co-culture Systems: Cultivating interdependent microbial communities together, as many extremophiles exist in syntrophic relationships [3].

- Diffusion Chambers: Using semi-permeable membranes to grow microbes in their natural environment while containing them for study [3].

- Long-term Enrichment: Incubating samples for extended periods under selective conditions to encourage the growth of slow-growing or rare taxa [19].

'Omics-Driven Biodiscovery

Culture-independent methods have revolutionized the field, allowing researchers to tap into the vast "microbial dark matter" that remains uncultured [3] [22].

- Metagenomics: This involves sequencing the total DNA extracted directly from an environmental sample. The resulting data allows for the assembly of Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) and the identification of genes encoding novel biocatalysts without the need for cultivation [3] [22]. This is particularly powerful for discovering Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR) bacteria and other elusive lineages in acidic mine drainage and other extremes [3].

- Functional Metagenomics: Cloning large fragments of environmental DNA into a cultivable host (e.g., E. coli) and screening libraries for desired enzymatic activities (e.g., esterase, lactamase) under extreme conditions [20]. This links gene sequence directly to function.

- Single-Cell Genomics: Isolating single microbial cells from an environmental sample, amplifying their genome, and sequencing it. This provides genomic context for organisms that cannot be cultured or assembled from metagenomes [3].

- Metatranscriptomics & Metaproteomics: Analyzing the total RNA and proteins expressed by a microbial community under specific conditions. These approaches reveal the actively used metabolic pathways and functional responses to environmental stimuli, guiding the identification of physiologically relevant enzymes [22].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from sampling to enzyme characterization.

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for discovering and characterizing novel enzymes from extremophiles, from environmental sampling to industrial application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The experimental workflows in extremophile research rely on specialized reagents and materials. Table 2 details essential research solutions for enzyme discovery and characterization.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Extremophile Enzyme Discovery

| Reagent / Material | Core Function | Application Example in Extremophile Research |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Growth Media | To replicate the chemical composition and physicochemical conditions (pH, salinity) of the native habitat for cultivation. | Culturing halophiles requires media with high molarity of NaCl or other salts; acidophiles need buffered low-pH media [19]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerases | Enzymes that catalyze DNA amplification via PCR at high temperatures, crucial for genetic manipulation. | Pfu polymerase from Pyrococcus furiosus offers high fidelity in PCR of GC-rich extremophile DNA [20]. |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Genetically engineered hosts (e.g., E. coli, yeast) used to produce proteins from cloned extremophile genes. | Production of Sulfolobus solfataricus γ-lactamase in E. coli for biocatalyst development [20]. |

| Immobilization Matrices | Solid supports (e.g., sepharose, polymer resins) for attaching enzymes to enhance stability and reusability. | Cross-linked enzyme aggregates of thermophilic γ-lactamase for use in continuous-flow microreactors [20]. |

| Activity-Based Probes | Chemical reagents that bind covalently to enzymes based on their catalytic mechanism, enabling detection and identification. | Fluorophosphonate probes for identifying serine-hydrolase family enzymes in complex metaproteomic samples [20]. |

| Ninhydrin Stain | A chromogenic agent that reacts with primary amines, visualizing amino acid production in screening assays. | Identifying active colonies in library screens for amidase or lactamase activity on agar plates [20]. |

Case Studies in Novel Enzyme Discovery

γ-Lactamase fromSulfolobus solfataricus

- Background: The bicyclic synthon (rac)-γ-lactam is a key intermediate for the synthesis of Abacavir, a potent anti-HIV drug [20]. The challenge is to kinetically resolve the racemic mixture to obtain a single enantiomerically pure product.

- Discovery & Protocol: A genomic library of the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus MT4 was constructed and expressed in E. coli. Colonies were screened by overlaying with filter paper soaked in the racemic γ-lactam substrate and ninhydrin stain. Active colonies that produced the amino acid product turned brown, allowing for identification of the (+)-γ-lactamase gene [20].

- Biochemical Characterization: The purified enzyme is a homodimer with optimal activity at high temperatures. It belongs to the signature amidase family but exhibits a unique mechanism, being activated by thiol reagents and inhibited by heavy metals [20].

- Industrial Application: The thermostable γ-lactamase was immobilized as a cross-linked enzyme preparation and packed into microreactors. The immobilized enzyme retained 100% activity after 6 hours at 80°C, demonstrating superior stability for continuous bioprocessing compared to the free enzyme [20].

L-Asparaginase from HalotolerantBacillus subtilis

- Background: L-asparaginase is a critical therapeutic enzyme used in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and in the food industry to reduce acrylamide formation [19]. Discovering stable and efficient variants is a key goal.

- Discovery & Protocol: A halotolerant strain, Bacillus subtilis CH11, was isolated from the hypersaline Chilca salterns in Peru [19]. The gene encoding a novel type II L-asparaginase was identified, cloned, and heterologously expressed in E. coli.

- Biochemical Characterization: The enzyme showed optimal activity at pH 9.0 and 60°C, with a half-life of nearly 4 hours at this temperature. Its activity was significantly enhanced by ions like K⁺ and Ca²⁺, which is characteristic of enzymes adapted to saline environments. Kinetic studies confirmed its efficiency and substrate affinity [19].

- Application Potential: Its alkaliphilic and thermotolerant nature, combined with halotolerance, makes it a promising candidate for industrial processes that occur under harsh conditions, offering potential improvements over existing mesophilic enzymes [19].

L-Aminoacylase fromThermococcus litoralis

- Background: Optically pure unnatural amino acids, like l-tert-leucine, are essential precursors to numerous pharmaceuticals, including antitumor compounds [20].

- Discovery & Protocol: An l-aminoacylase gene was identified from a DNA expression library of the thermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis, initially screened for esterase activity [20].

- Biochemical Characterization: The enzyme is highly thermostable, with a half-life of 25 hours at 70°C and optimal activity at 85°C. It exhibits broad substrate specificity, showing high activity toward N-acetylated aromatic and aliphatic amino acids [20].

- Industrial Application: The recombinant enzyme was immobilized on Sepharose beads to create a column bioreactor. This system showed no loss of activity after 5 days of continuous operation at 60°C, demonstrating exceptional operational stability for the production of chiral amino acids [20].

Current Research Landscape and Future Directions

The field of extremophile research is experiencing rapid growth, with the number of related scientific documents tripling over the past 25 years and yearly patent filings increasing four-fold since 2000 [3]. This reflects a rising recognition of the commercial and scientific value of these organisms.

Future advancements will be driven by several key frontiers:

- Astrobiology and the Origin of Life: Extremophiles serve as analogs for potential extraterrestrial life. Subsurface methanogens in permafrost and sulfur-metabolizing archaea in hydrothermal vents provide clues about how life might persist on Mars, Europa, or Enceladus [3] [21]. Studying their adaptations helps define the universal constraints on life.

- Addressing Antibiotic Resistance: Extremophiles are a rich source of novel antimicrobial peptides with unique structures, such as hyperthermostable peptides from deep-sea thermophiles that disrupt bacterial membranes through pore-forming mechanisms, potentially bypassing existing resistance pathways [3].

- Environmental Sustainability and Green Chemistry: Extremozymes are pivotal for developing environmentally friendly industrial processes. Their use in biocatalysis avoids the toxic waste associated with traditional chemistry [20]. Furthermore, their application in bioremediation—such as using bacteria from disused copper mines to break down pollutants in hypersaline, sulfidic environments—offers solutions for cleaning contaminated sites [19].

- Overcoming Discovery Challenges: The main hurdles remain the cultivation of the majority of extremophiles and the scalability of compound production [3] [22]. Future research must leverage synthetic biology and CRISPR-based pathway engineering to express entire biosynthetic gene clusters in tractable hosts [3]. There is also a pressing need to integrate toxicity and efficacy validation into standard biodiscovery pipelines to accelerate the translation of novel compounds from the lab to the market [22].

In conclusion, extremophile habitats constitute a vast and still underexplored reservoir of biodiversity. The unique evolutionary innovations encoded within these ecosystems offer unparalleled opportunities for the discovery of novel enzymes and bioactive compounds. As exploration and analytical technologies continue to advance, research into life at the edge will undoubtedly yield transformative solutions for medicine, industry, and environmental stewardship.

Extremozymes, enzymes derived from microorganisms that thrive in extreme environments, are rapidly transitioning from scientific curiosities to central pillars of modern industrial biotechnology. Their inherent stability and catalytic efficiency under harsh conditions—where conventional enzymes fail—make them uniquely suited to revolutionize industries ranging from pharmaceuticals to biofuels. This whitepaper delineates the compelling commercial rationale behind the multibillion-dollar valuation of the extremozymes market, frames their discovery within the context of novel enzyme research, and provides a detailed technical guide for their procurement and characterization. Supported by quantitative market analysis and explicit experimental methodologies, we posit that extremozymes are not merely a niche segment but a fundamental commercial imperative for sustainable industrial innovation.

The global industrial enzymes market is a robust, high-growth sector, with the broader market projected to expand from approximately USD 8.76 billion in 2025 to USD 16.04 billion by 2034, growing at a CAGR of 6.95% [23]. Within this landscape, extremozymes represent a critical and rapidly accelerating segment. Recent market intelligence specifically values the global extremophile enzymes market at USD 1.24 billion to USD 1.59 billion in 2024 [24] [25]. This niche is forecasted to grow at a remarkable CAGR of 7.8% to 9.4%, reaching a projected value of USD 2.81 billion to USD 3.16 billion by 2033 [24] [25], significantly outpacing the growth of the general industrial enzymes market.

The table below summarizes key market data and growth projections for the extremozyme sector.

Table 1: Extremozymes Market Size and Forecast

| Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2033/2034 Forecast | CAGR (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremophile Enzymes Market Size | USD 1.24 - 1.59 Billion | USD 2.81 - 3.16 Billion | 7.8 - 9.4 | [24] [25] |

| Broader Industrial Enzymes Market Size | USD 8.76 Billion (2025) | USD 16.04 Billion (2034) | 6.95 | [23] |

| North America Market Share (2024) | ~38% | - | - | [24] |

| Leading Product Segment | Thermophilic Enzymes (~33% share) | - | - | [24] |

| Dominant Source Segment | Bacterial Sources (~45% share) | - | - | [24] |

This growth is fundamentally driven by the escalating demand for sustainable and efficient biocatalysts across myriad industries. Extremozymes offer unparalleled advantages, including improved process efficiency, increased specificity, and a reduced environmental footprint compared to traditional chemical catalysts [23]. Their ability to function under extreme temperatures, pH, salinity, and pressure aligns perfectly with the harsh conditions of industrial processes, making them indispensable for green chemistry initiatives and cost-effective manufacturing [12] [25].

Scientific and Industrial Rationale

Defining Extremophile Adaptations and Extremozyme Properties

Extremophiles are organisms belonging to the domains Archaea and Bacteria that colonize ecological niches considered inhospitable to most life, including hot springs, deep-sea vents, polar ice, and hypersaline lakes [4] [3]. Their enzymes, extremozymes, have evolved distinct structural and mechanistic adaptations that confer exceptional stability and activity under these extremes [12] [13].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between extreme environments, the adaptive features of extremozymes, and their resulting industrial advantages.

Diagram: The logical pathway from extreme environments to industrial value, showcasing how specific environmental pressures select for unique enzymatic adaptations that translate into commercial benefits.

For instance, thermophilic enzymes exhibit enhanced protein rigidity through increased hydrophobic interactions, salt bridges, and a higher proportion of charged amino acids, enabling function at elevated temperatures [4] [12]. In contrast, psychrophilic enzymes maintain high flexibility and increased entropy at low temperatures via a higher content of small, less bulky amino acids like glycine and a reduction in stabilizing salt bridges [4] [12]. These intrinsic properties are the foundation of their commercial utility.

Key Industrial Applications and Market Drivers

The application spectrum of extremozymes is vast and expanding, directly fueling market growth.

- Pharmaceuticals and Biotechnology: This is a dominant application segment [24] [25]. Extremozymes are crucial for drug synthesis, biotransformation, and the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [25]. Their high specificity and stability under extreme conditions enable greener pharmaceutical manufacturing. Furthermore, enzymes like Taq polymerase (from Thermus aquaticus) have revolutionized molecular biology through PCR, and L-asparaginase from halotolerant bacteria is used in cancer treatment [4] [3].

- Biofuels: The biofuel segment is expected to grow at a significant rate [26]. Thermophilic carbohydrases (e.g., cellulases, xylanases) are indispensable for the efficient breakdown of lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars at industrially relevant high temperatures, improving yield and reducing contamination risk [23] [25].

- Food & Beverages: The demand for clean-label and natural ingredients is driving the adoption of extremozymes in food processing [26] [25]. Psychrophilic enzymes are used for low-temperature processes, preserving heat-sensitive substrates and saving energy, while proteases and carbohydrases enhance flavor, texture, and shelf life [23] [25].

- Detergents and Household Care: Alkaliphilic proteases and lipases are workhorses in detergent formulations, maintaining activity in the high-pH, surfactant-rich environments of modern washing machines [12].

- Agriculture and Environmental Remediation: Extremozymes are used for soil remediation, crop protection, and waste management [25]. Their ability to function in contaminated or extreme environments makes them ideal for bioremediation of pollutants and treatment of industrial effluents [4] [3].

The primary market drivers include the shift towards sustainable and green industrial processes, technological advancements in enzyme engineering, and stringent environmental regulations [23] [24] [25].

Discovery and Development Workflow

The pipeline from sampling to a commercially viable extremozyme is complex and requires interdisciplinary expertise. The following section details the experimental protocols and workflows central to this process.

Sample Collection and Microbial Isolation

Protocol 1: Sampling from Extreme Environments

- Objective: To aseptically collect environmental samples rich in extremophilic microorganisms.

- Materials: Sterile sampling containers (e.g., Niskin bottles for deep-sea vents, corers for geothermal soils), temperature and pH probes, portable freezer for psychrophilic samples, anaerobic jars for anoxic sites.

- Methodology:

- Site Selection: Prioritize underexplored extreme biomes (e.g., deep-sea hydrothermal vents, hyperacidic lakes, polar permafrost) [4].

- In-situ Characterization: Measure and record physical parameters (temperature, pH, salinity) at the collection point.

- Sample Collection: Use sterile techniques to avoid contamination. For subsurface samples, drilling or coring may be necessary. Preserve sample integrity by mimicking in-situ conditions during transport (e.g., using pressure vessels for piezophiles) [4] [13].

Protocol 2: Cultivation-Dependent Isolation

- Objective: To isolate pure extremophilic cultures from environmental samples.

- Materials: Specific culture media designed to mimic the chemical and physical conditions of the source environment (e.g., thermophilic media incubated at 70-100°C, halophilic media with 2-5M NaCl), anaerobic chambers, shaker incubators.

- Methodology:

- Enrichment Culture: Inoculate sample into selective liquid media and incubate under extreme conditions to enrich for target extremophiles.

- Pure Culture Isolation: Streak enriched culture onto solid agar plates of the same medium. Isolate individual colonies and re-streak until purity is confirmed via microscopy and 16S rRNA gene sequencing [4].

- Challenge: An estimated 99% of microorganisms are unculturable with standard techniques, representing a significant bottleneck known as "microbial dark matter" [13].

Culture-Independent Metagenomic Discovery

To bypass cultivation limitations, metagenomic approaches are now standard.

Protocol 3: Metagenomic Library Construction and Screening

- Objective: To access the genetic potential of the entire microbial community without cultivation.

- Materials: DNA extraction kits optimized for complex matrices (e.g., soil, sediment), fosmid or bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vectors, competent E. coli cells for library hosting, substrates for functional screening (e.g., cellulose azure for cellulases).

- Methodology:

- Total DNA Extraction: Directly extract high-molecular-weight DNA from the environmental sample [4] [13].

- Library Construction: Fragment the DNA and clone it into a suitable vector, which is then transformed into a surrogate host (typically E. coli) to create a metagenomic library representing the collective genome of the sample [13].

- Screening:

- Function-Based Screening: Plate library clones on media containing a substrate for the target enzyme activity (e.g., skim milk for proteases, tributyrin for lipases). Positive clones form a halo zone indicating substrate degradation [13].

- Sequence-Based Screening: Use degenerate primers to PCR-amplify conserved enzyme genes from the metagenomic DNA, followed by sequencing and heterologous expression of full-length genes [13].

The following workflow diagram integrates both cultivation-dependent and independent pathways for extremozyme discovery.

Diagram: A unified workflow for extremozyme discovery, showing parallel cultivation-dependent and metagenomic pathways converging on enzyme characterization.

Key Reagents for Extremozyme Research

The following table details essential reagents and their functions in extremozyme discovery and characterization.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Extremozyme Discovery

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Specialized Culture Media | Mimics the chemical (pH, salinity, specific electron donors/acceptors) and physical (gelling agents for high temp) parameters of the source environment to facilitate cultivation of fastidious extremophiles [4] [13]. |

| Fosmid / BAC Vectors | Used in metagenomic library construction for cloning large (30-40 kb) fragments of environmental DNA, helping to capture large gene clusters and operons [13]. |

| Surrogate Expression Hosts | Model organisms like E. coli or Bacillus subtilis are used for the heterologous expression of cloned extremozyme genes. Requires optimization, sometimes including co-expression of molecular chaperones, to correctly fold complex proteins [13]. |

| Chromogenic/ Fluorogenic Substrates | Synthetic substrates (e.g., p-nitrophenyl derivatives) that release a colored or fluorescent product upon enzymatic hydrolysis. Enable high-throughput functional screening of metagenomic libraries or characterization of enzyme kinetics [13]. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Tags (e.g., His-tag) are engineered into recombinant extremozymes, allowing for single-step purification using resins like Ni-NTA, which is crucial for obtaining pure protein for biochemical and structural studies [13]. |

Technological Advancements and Future Outlook

The field is being transformed by several key technologies that address current challenges and unlock new potential.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI and deep neural network models are accelerating enzyme discovery and engineering by predicting enzyme structures, functions, and stability from sequence data. This guides the rational design of extremozymes with enhanced properties like thermal stability, activity, and selectivity for specific industrial processes [23] [27].

- Advances in Enzyme Engineering: Directed evolution and rational protein design are being used to tailor the properties of naturally discovered extremozymes to meet even more stringent industrial requirements [13] [25]. This includes improving catalytic efficiency, altering substrate specificity, and enhancing stability in organic solvents.

- Overcoming Production Challenges: A major hurdle in the commercial development of extremozymes is low biomass yield and slow growth of native extremophilic producers [13]. Strategies to overcome this include optimized fermentation processes, codon optimization of genes for heterologous expression, and the co-expression of chaperone proteins in surrogate hosts to aid in the correct folding of complex extremozymes [13].

The future of this market is intrinsically linked to the continued development and application of these technologies. As the demand for sustainable industrial solutions grows, extremozymes are poised to play an increasingly critical role in enabling the biocatalytic processes of the future, solidifying their status as a multibillion-dollar commercial imperative.

From Sample to Solution: Modern Methods for Extremozyme Discovery and Their Applications

Within the broader context of discovering novel enzymes from extremophiles, culture-dependent approaches remain a cornerstone methodology for accessing the functional potential of resilient microorganisms. While metagenomic techniques provide unprecedented insights into genetic blueprints, cultivating microbial isolates is indispensable for directly linking genotype to phenotype, enabling researchers to study functional characteristics, metabolic pathways, and enzyme production under controlled laboratory conditions [28]. The primary challenge in this field is the "great plate count anomaly," where traditionally only a small percentage of microorganisms from any environment were believed to be culturable [28]. However, recent advances have demonstrated that a higher proportion of marine bacteria, and by extension extremophiles, can be cultured than previously thought when appropriate techniques are employed [28].

Extremophiles thrive in environments characterized by extreme temperature, pH, salinity, pressure, or radiation, and have evolved unique biochemical adaptations to survive these conditions [3]. These adaptations include specialized enzymes known as extremozymes, which exhibit remarkable stability and functionality under harsh conditions that would denature most proteins [3]. For researchers focused on drug development and industrial applications, culture-dependent approaches provide direct access to these extremozymes, which hold immense potential for pharmaceutical processes, biotechnology, and therapeutic interventions [29] [3]. This technical guide details the methodologies for isolating, cultivating, and screening microbial isolates from extreme niches specifically for novel enzyme discovery.

Strategic Isolation Approaches from Diverse Extreme Niches

Successful isolation of extremophiles requires careful consideration of the source environment and replication of those specific conditions in the laboratory. The table below summarizes target organisms and strategic considerations for sampling from various extreme environments.

Table 1: Strategic Isolation Approaches for Different Extreme Environments

| Extreme Environment | Target Microorganisms | Sampling & Isolation Considerations | Potential Enzyme Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Temperature (e.g., hot springs, hydrothermal vents) | Thermophiles, Hyperthermophiles (e.g., Thermus aquaticus, Sulfolobus species) | Use heat-resistant materials; maintain anaerobic conditions for subsurface samples; simulate vent pressure if possible [28] [3] | Thermostable DNA polymerases, proteases, lipases [3] |

| Low Temperature (e.g., polar ice, deep sea) | Psychrophiles (e.g., Psychrobacter, Polaromonas) | Prevent temperature fluctuation during transport; use low-temperature pre-reduced media [28] [18] | Cold-active enzymes (proteases, lipases) for detergents, food processing [29] |

| High Salinity (e.g., salt lakes, salterns) | Halophiles (e.g., Halobacterium, Salinibacter) | Include compatible solutes (e.g., betaine) in media; adjust ionic strength to match environment [28] [3] | Halotolerant enzymes for industrial catalysis in non-aqueous media [3] |

| Extreme pH (Acidic: acid mine drainage; Alkaline: soda lakes) | Acidophiles (e.g., Acidithiobacillus), Alkaliphiles (e.g., Bacillus alkaliphilus) | Buffer media strongly at target pH; consider element solubility changes at extreme pH [3] [30] | Acid-stable cellulases, alkaliphilic proteases for detergents [29] [3] |

| High Pressure (e.g., deep-sea sediments, trenches) | Piezophiles (Barophiles) | Utilize pressurized vessels; simulate in-situ temperature and chemical composition [28] | Pressure-resistant enzymes for high-pressure bioreactors |

Cultivation Techniques and Media Formulation

Mimicking Natural Habitat Conditions

The fundamental principle in cultivating extremophiles is replicating the chemical, physical, and biological conditions of their native environment. This requires careful attention to:

- Physicochemical Parameters: Precisely control temperature, pH, pressure, and oxygen concentration throughout the cultivation process [28]. For example, thermophiles require incubation at elevated temperatures (45-122°C), while psychrophiles need temperatures below 15°C [18].

- Media Composition: Formulate growth media with ionic strength and nutrient composition reflecting the source environment. For halophiles, this means high concentrations of specific salts (e.g., 1.5-4.0 M NaCl); for acidophiles, strongly buffered acidic media [3].

- Nutrient Specificity: Many extremophiles have fastidious growth requirements that are difficult to replicate in the laboratory [28]. Some may require specific growth factors, trace elements, or unique energy sources available only in their native habitat.

- Solid vs. Liquid Media: Utilize both solid and liquid media formats to increase cultivation success. Gellan gum is often preferred over agar for solid media, especially for acidophiles, as it remains stable at extreme pH and does not inhibit growth like agar can at high temperatures [28].

Addressing the "Unculturable" Challenge

Several innovative strategies have emerged to improve cultivation success for previously uncultivated extremophiles:

- Diffusion Chambers: Cultivate microorganisms in their natural environment by using diffusion chambers that allow chemical exchange with the native habitat while containing the cells [28].

- Co-culture Approaches: Simulate microbial interactions by cultivating target organisms with their natural symbiotic partners, as many microorganisms depend on metabolic cooperation [28].

- High-Throughput Cultivation: Utilize microcultivation techniques in 96-well plates with diluted inocula to isolate slow-growing species that would be outcompeted in standard plates [28].

- Long Incubation Periods: Extend incubation times significantly (weeks to months) to accommodate extremely slow-growing organisms with generation times much longer than typical laboratory strains [28].

Quantitative Growth Parameters for Extremophiles

Designing appropriate cultivation conditions requires understanding the growth limits and optima for different classes of extremophiles. The following table summarizes key parameters for major extremophile groups, providing targets for media development and incubation conditions.

Table 2: Growth Parameters for Major Extremophile Classes

| Extremophile Type | Growth Temperature (°C) | Growth pH Range | Salinity Tolerance | Notable Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychrophiles | -20 to 15 [18] | Neutral (varies) | Low to moderate | Flexible enzymes, antifreeze proteins [28] |

| Thermophiles | 45-80 [28] [3] | Neutral (varies) | Low to moderate | Thermostable enzymes, specialized membranes [3] |

| Hyperthermophiles | 80-122 [28] [3] | Neutral to acidic | Low | Reverse DNA gyrase, ether-linked lipids [3] |

| Acidophiles | Variable | 0.5-5.5 [3] | Low to moderate | Proton pumps, acid-stable proteins [3] |

| Alkaliphiles | Variable | 8.5-11.5 [3] | Low to high | Sodium motive force, alkaline-stable proteins [3] |

| Halophiles | Variable | Neutral to alkaline | 1.5-4.0 M NaCl [3] | Compatible solutes, salt-in strategy [3] |

Screening for Enzyme Activity

Primary Screening Methodologies

Once isolated, extremophilic microorganisms must be screened for enzyme production using targeted approaches:

- Substrate-Based Assays: Incorporate specific substrates directly into growth media to detect enzyme activity. For example, cellulose or xylan for hydrolytic enzymes, skim milk for proteases, or tributyrin for lipases [31]. These assays typically produce visible zones of hydrolysis around active colonies.

- Chromogenic and Fluorogenic Substrates: Use synthetic substrates that release colored or fluorescent products upon enzymatic hydrolysis, enabling sensitive detection and semi-quantification of activity directly on agar plates [31].

- pH-Based Screening: For activities that alter pH (e.g., esterases, lipases), incorporate pH indicators like phenol red or bromothymol blue to detect acid production from substrate hydrolysis [31].

High-Throughput Screening Approaches

To efficiently process numerous isolates, implement high-throughput screening methods:

- Microtiter Plate Assays: Grow isolates in 96- or 384-well plates and assay enzyme activity using small-volume reactions with spectrophotometric, fluorometric, or luminescent detection [31].

- Robotic Screening Systems: Employ automated systems capable of processing thousands of clones daily, significantly increasing screening throughput [31].

- Multi-Substrate Profiling: Screen each isolate against multiple substrates to identify enzymes with broad specificity or unexpected activities [31].

Experimental Workflow: From Sampling to Enzyme Characterization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for culture-dependent discovery of novel enzymes from extreme environments, integrating both standard and advanced approaches to maximize discovery potential.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful cultivation and screening of extremophiles requires specialized reagents and materials tailored to their unique growth requirements. The following table details essential components for establishing a comprehensive extremophile research program.