From Discovery to Clinic: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinically Validating Novel Enzyme Biomarkers

This article provides a systematic roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complex process of clinically validating novel enzyme biomarkers.

From Discovery to Clinic: A Comprehensive Guide to Clinically Validating Novel Enzyme Biomarkers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating the complex process of clinically validating novel enzyme biomarkers. It covers the journey from foundational discovery and biological rationale to advanced methodological applications, tackling common troubleshooting challenges, and navigating the evolving regulatory landscape for qualification. By synthesizing current best practices, technological advancements, and statistical considerations, this guide aims to bridge the gap between promising experimental findings and the robust clinical evidence required for biomarker integration into diagnostic and therapeutic development, ultimately accelerating the path to personalized medicine.

Laying the Groundwork: Defining Novel Enzyme Biomarkers and Their Clinical Potential

What Makes an Enzyme a 'Novel' Biomarker? Definition and Key Characteristics

In the rapidly evolving field of clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development, a novel enzyme biomarker is defined as a recently discovered or applied enzymatic molecule that provides a specific, measurable indicator of biological processes, pathogenic states, or pharmacological responses to therapeutic intervention. The "novel" designation encompasses not only newly discovered enzymes but also established enzymes being applied to new clinical contexts, offering enhanced diagnostic or prognostic capabilities compared to existing biomarkers. These biomarkers are characterized by improved specificity, sensitivity, and clinical utility for early disease detection, accurate prognosis, and precise monitoring of therapeutic responses, particularly in areas of unmet medical need where traditional biomarkers demonstrate limitations [1] [2].

The validation pathway for novel enzyme biomarkers requires rigorous analytical validation, clinical qualification, and context-specific utilization to meet regulatory standards and achieve clinical adoption. The emergence of novel enzymes as biomarkers is being driven by advancements in 'omics' technologies, multiplexed assay platforms, and a growing understanding of enzymatic roles in disease pathophysiology, positioning them as critical tools in the advancement of precision medicine [1] [3] [4].

Enzymes have served as fundamental biomarkers in clinical chemistry for decades, with historically established examples including alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for liver function, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) for cardiac damage, and amylase for pancreatitis [2] [5]. However, significant limitations in these conventional biomarkers—including lack of tissue specificity, suboptimal sensitivity for early detection, and interference from non-pathological conditions—have driven the search for novel enzymatic indicators with enhanced performance characteristics [2] [6].

The definition of "novel" in this context extends beyond mere discovery chronology to encompass several key dimensions:

- Application Novelty: Known enzymes applied to new disease indications or clinical contexts

- Methodological Novelty: Enzymes measurable through new technological platforms with superior performance

- Informational Novelty: Enzymes that provide fundamentally new insights into disease mechanisms or treatment responses

- Regulatory Novelty: Enzymes that have recently received regulatory qualification for specific contexts of use [2] [6]

This evolution reflects a paradigm shift from traditional, single-marker approaches toward multiplexed, context-specific biomarker strategies that offer greater precision in clinical decision-making and therapeutic development [1] [7].

Defining Characteristics of Novel Enzyme Biomarkers

Enhanced Specificity and Sensitivity

Novel enzyme biomarkers demonstrate significantly improved tissue and pathway specificity compared to traditional markers, enabling more accurate differentiation between disease states and reducing false positives. For example, glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH) has recently been qualified by the FDA as a specific biomarker for drug-induced liver injury in patients with muscle disease, where traditional markers like ALT and AST are confounded by concurrent muscle damage [6]. This enhanced specificity directly addresses a long-standing challenge in safety monitoring for clinical trials involving patients with neuromuscular disorders.

Clinical Utility in Early Detection and Monitoring

A defining characteristic of novel enzyme biomarkers is their ability to facilitate earlier disease detection and more precise therapy monitoring than established alternatives. Thymidine kinase 1 (TK1), for instance, has emerged as a sensitive serum biomarker for early diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy monitoring in breast cancer, often detecting disease recurrence or treatment response before clinical manifestations become apparent [2]. Similarly, glycogen phosphorylase BB (GPBB) demonstrates superior performance in detecting myocardial infarction within 4 hours of symptom onset, providing a critical diagnostic window for intervention [5].

Mechanistic Link to Disease Pathways

Unlike traditional biomarkers that may represent general indicators of tissue damage, novel enzyme biomarkers often have a direct pathophysiological connection to specific disease mechanisms. Enzymes such as cathepsins (B, D, and L) are not merely leakage markers but actively participate in tumor angiogenesis and proliferation processes in ovarian, pancreatic, colorectal, breast, and lung cancers [5]. This mechanistic relationship enhances their biological plausibility and strengthens their correlation with disease progression and therapeutic response.

Qualification Through Rigorous Validation Frameworks

Novel enzyme biomarkers undergo systematic validation through established regulatory frameworks such as the FDA-NIH Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) resource, which defines specific biomarker categories including diagnostic, monitoring, pharmacodynamic/response, predictive, prognostic, safety, and susceptibility/risk biomarkers [1]. The successful qualification of GLDH through the FDA's Biomarker Qualification Program exemplifies the rigorous evidentiary standards required for novel biomarker adoption in clinical trials and practice [6].

Classification and Regulatory Context

Biomarker Categories and Definitions

The BEST resource establishes precise definitions for biomarker categories that are essential for understanding the application of novel enzymes:

| Biomarker Category | Definition | Example Novel Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Biomarker | Detects or confirms presence of a disease or identifies individuals with a disease subtype | Carbonic anhydrase XII (pleural fluid for lung cancer) [2] |

| Monitoring Biomarker | Measured serially to assess disease status or evidence of exposure/effect | Thioredoxin reductase (plasma/serum for liver cancer therapy monitoring) [2] |

| Prognostic Biomarker | Predicts disease recurrence, progression, or other clinical outcomes | Caspase-3/7 (serum for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma) [2] |

| Predictive Biomarker | Identifies individuals more likely to respond to a specific therapeutic | Separase (peripheral blood for chronic myeloid leukemia) [2] |

| Safety Biomarker | Measured to indicate likelihood of adverse events | GLDH (serum for drug-induced liver injury) [6] |

| Pharmacodynamic/Response Biomarker | Shows biological response to therapeutic intervention | Ecto-5'-nucleotidase (plasma for breast cancer treatment response) [2] |

Regulatory Validation Pathway

The pathway from discovery to clinical implementation for novel enzyme biomarkers involves multiple validation stages:

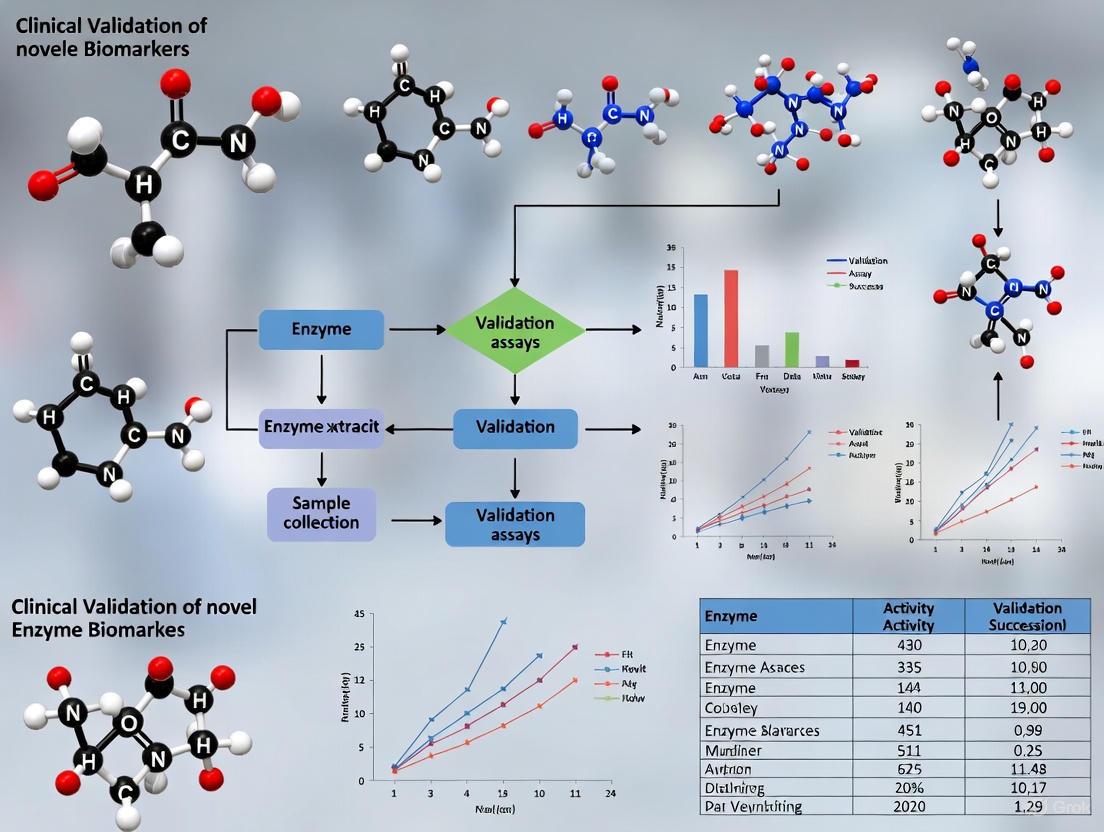

Biomarker Validation Pathway

This validation pathway requires extensive evidence generation, with approximately 77% of biomarker qualification challenges linked to assay validity issues, highlighting the critical importance of methodological rigor [8].

Comparative Analysis: Novel vs. Traditional Enzyme Biomarkers

Performance Characteristics Comparison

| Characteristic | Traditional Enzyme Biomarkers | Novel Enzyme Biomarkers | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Often limited tissue specificity (e.g., ALT elevated in both liver and muscle damage) [6] | Enhanced tissue specificity (e.g., GLDH primarily hepatic) [6] | Reduced false positives, accurate differential diagnosis |

| Sensitivity | Moderate sensitivity for established disease | Higher sensitivity for early-stage detection (e.g., TK1 in breast cancer) [2] | Earlier intervention, improved outcomes |

| Mechanistic Link | Frequently correlates with tissue damage without direct disease mechanism involvement | Direct involvement in disease pathways (e.g., cathepsins in tumor angiogenesis) [5] | Better correlation with disease progression, superior therapeutic monitoring |

| Dynamic Range | Often limited analytical range | Broader dynamic range enabled by advanced detection platforms [8] | Accurate quantification across disease stages |

| Multiplexing Capability | Typically measured individually | Compatible with multiplexed panels (e.g., U-PLEX platform) [8] | Comprehensive biomarker signatures, improved diagnostic accuracy |

Clinical Application Comparison

| Disease Area | Traditional Enzyme Biomarkers | Novel Enzyme Biomarkers | Advancement Represented |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Safety Monitoring | ALT, AST (confounded by muscle disease) [6] | GLDH (liver-specific) [6] | Specific biomarker for patients with comorbid muscle conditions |

| Cancer Diagnostics | PSA, CA-125 (limited specificity) | TK1, cathepsins, carbonic anhydrase XII [2] [5] | Earlier detection, molecular subtyping, therapy monitoring |

| Cardiac Injury | CK-MB, myoglobin | GPBB (detectable within 4 hours) [5] | Earlier diagnosis of myocardial infarction |

| Bone Disorders | ALP (limited specificity) | TRAP (specific to osteoclast activity) [5] | Distinction between different bone pathologies |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Analytical Validation Framework

Robust analytical validation is fundamental to establishing novel enzyme biomarkers. Key methodological approaches include:

Multiplexed Immunoassays: Platforms such as Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) employ electrochemiluminescence detection, offering up to 100-fold greater sensitivity than traditional ELISA with broader dynamic range [8]. These systems enable simultaneous quantification of multiple enzyme biomarkers in small sample volumes (25-50 μL), enhancing efficiency while reducing costs by approximately 70% compared to individual ELISAs [8].

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): This technology provides exceptional specificity and sensitivity for low-abundance enzyme detection, enabling analysis of hundreds to thousands of proteins in single runs while avoiding antibody-dependent limitations of immunoassays [8].

Activity-Based Detection Methods: Many novel enzymes are quantified through functional assays measuring catalytic activity. For example, G6PD activity measurement serves as a biomarker for gastric cancer progression and leukemias, while acetylcholinesterase activity assays are utilized in neurodegenerative disease diagnostics [5].

Clinical Validation Study Designs

Clinical validation of novel enzyme biomarkers requires carefully structured approaches:

Case-Control Studies: Initial clinical validation typically employs case-control designs comparing biomarker levels between well-characterized patient groups and matched controls. For example, studies of carbonic anhydrase XII in pleural fluid for lung cancer diagnosis demonstrated significantly elevated levels in malignant versus benign effusions [2].

Longitudinal Monitoring Studies: Serial assessment of biomarker levels throughout disease progression and treatment response establishes monitoring utility. Research on separase in chronic myeloid leukemia employed flow cytometry to track enzyme levels over time, correlating changes with treatment response and disease progression [2].

Blinded Validation Cohorts: Independent validation in prospectively collected sample sets using predefined cutoff values is essential to minimize overfitting and establish generalizable performance characteristics.

Research Reagent Solutions for Novel Enzyme Biomarker Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Applications in Novel Enzyme Biomarker Research |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Substrates | AquaSpark alkaline phosphatase substrate, methylumbelliferyl phosphate [5] | Chemiluminescent and fluorogenic detection of enzyme activity in biological samples |

| Assay Platforms | MSD U-PLEX multiplex panels, LC-MS/MS systems [8] | Simultaneous quantification of multiple enzyme biomarkers with enhanced sensitivity |

| Specific Antibodies | Anti-CK-MB monoclonal antibodies, anti-TK1 antibodies [2] [5] | Immunoassay development for enzyme quantification and localization |

| Activity Assay Kits | Acetylcholinesterase assay kits, acid phosphatase assay kits [5] | Functional assessment of enzyme activity in clinical samples |

| Sample Preparation Reagents | Cell lysis buffers, protease inhibitors, protein stabilizers | Preservation of enzyme integrity in biological specimens during processing |

Technological Advances Driving Novel Enzyme Biomarker Discovery

Advanced Detection Platforms

The evolution beyond traditional ELISA methodologies to advanced platforms has significantly accelerated novel enzyme biomarker development:

Electrochemiluminescence Detection: MSD technology utilizes electrochemical stimulation of labels to emit light, providing substantially improved sensitivity and dynamic range compared to colorimetric detection [8].

Digital PCR Platforms: Enable absolute quantification of enzyme biomarkers at extremely low concentrations, particularly valuable for monitoring minimal residual disease in oncology applications [9].

Microarray Technologies: Allow parallel assessment of multiple molecular markers, transitioning from single biomarker testing to comprehensive biomarker signatures for clinical guidance [10].

Omics Technologies

High-throughput omics approaches have revolutionized enzyme biomarker discovery:

Proteomic Profiling: Mass spectrometry-based proteomics enables identification of differentially expressed enzymatic proteins across disease states [7].

Transcriptomic Analysis: RNA sequencing technologies facilitate discovery of enzyme expression patterns associated with specific pathologies [7].

Metabolomic Approaches: Measurement of metabolic fluxes provides functional readouts of enzymatic activities in physiological and disease states [7].

The field of novel enzyme biomarkers represents a dynamic interface between basic science, clinical medicine, and technological innovation. The defining characteristics of these biomarkers—enhanced specificity, mechanistic relevance, and demonstrated clinical utility—position them as powerful tools for advancing precision medicine across therapeutic areas. The rigorous validation pathway from discovery to regulatory qualification and clinical implementation ensures that truly valuable novel enzyme biomarkers meet the stringent standards required for informed clinical decision-making.

Future directions in this field include the development of increasingly multiplexed biomarker panels, integration of artificial intelligence for pattern recognition in complex enzymatic data, and the application of liquid biopsy approaches for minimally invasive disease monitoring. As detection technologies continue to evolve and our understanding of disease pathophysiology deepens, novel enzyme biomarkers will play an increasingly central role in enabling earlier diagnosis, more accurate prognosis, and personalized therapeutic strategies across a broad spectrum of human diseases.

Enzyme markers represent a cornerstone of modern clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development, serving as quantifiable indicators of biological processes, pathological states, or pharmacological responses to therapeutic intervention. These specialized biomarkers, which include specific enzymes such as 5'-nucleotidase, acetatedehydehydrogenase, neutral alpha-glucosidase, catalase, and N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase, provide invaluable insights into cellular function and dysfunction across a spectrum of diseases [11]. The global enzyme markers market reflects their critical importance, projected to reach approximately USD 8.5 to 25,500 million by 2032-2033, with a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.8% to 12.5%, fueled by increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, advancements in diagnostic technologies, and the growing emphasis on personalized medicine [11] [12].

Within the context of clinical validation research for novel biomarkers, enzymes present a compelling case for widespread adoption and continued investigation. Their unique biochemical properties—including catalytic activity, substrate specificity, and regulatable expression—position them as exceptionally sensitive and dynamic indicators of physiological homeostasis and pathological disruption. Unlike static biomarkers that provide snapshot information, enzyme biomarkers often reflect real-time functional changes within tissues and biological systems, enabling clinicians and researchers to monitor disease progression, assess therapeutic efficacy, and make informed decisions about treatment strategies [11] [7]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of enzyme biomarkers against alternative biomarker classes, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies relevant to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in biomarker validation.

Comparative Analysis: Enzyme Biomarkers Versus Alternative Modalities

The selection of appropriate biomarkers is critical for successful clinical validation and eventual translation to diagnostic applications. The table below provides a systematic comparison of enzyme biomarkers against other prevalent biomarker classes, highlighting key performance characteristics and practical considerations for research and development.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Biomarker Classes for Clinical Validation Research

| Biomarker Characteristic | Enzyme Biomarkers | Genetic/DNA Methylation Biomarkers | Proteomic Biomarkers | Metabolomic Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representative Examples | 5'-nucleotidase, Catalase, N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase [11] | Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes [9] | PSA, C-reactive protein | Glucose, Lactate, Cholesterol |

| Primary Biological Media | Blood, Urine, Tissue samples [11] | ctDNA from blood plasma, urine, CSF [9] | Serum, Plasma, Tissue | Serum, Plasma, Urine |

| Stability During Processing | Moderate to High (dependent on preservation conditions) | High (DNA methylation patterns remain stable) [9] | Variable (prone to degradation) | Low to Moderate (requires immediate processing) |

| Detection Methodology | Activity assays, ELISA, Spectrophotometry [12] | Bisulfite sequencing, PCR-based methods, Microarrays [9] | Immunoassays, Mass spectrometry | Mass spectrometry, NMR |

| Dynamic Range | High (catalytic amplification) | Limited to copy number | Moderate (no inherent amplification) | High (reflects metabolic flux) |

| Functional Information | Direct functional readout (catalytic activity) | Information on regulation (epigenetic control) [9] | Protein abundance | Metabolic pathway activity |

| Temporal Resolution | High (rapid response to physiological changes) | Low (represents cumulative changes) [9] | Moderate | Very High (near real-time) |

| Technical Reproducibility | High (established standardized assays) | Moderate to High (standardization improving) | Variable (antibody-dependent) | Moderate (instrument-sensitive) |

| Cost per Sample Analysis | $ | $$-$$$ | $$-$$$ | $$$ |

| Clinical Translation Potential | High (well-established in diagnostics) | Emerging (several in validation) [9] | High (widely used) | Emerging |

Enzyme biomarkers demonstrate distinct advantages in providing direct functional information through their catalytic activity, offering high temporal resolution to monitor dynamic physiological changes. Their detection often leverages catalytic amplification, enabling sensitive measurement even at low concentrations. While DNA methylation biomarkers provide valuable epigenetic information with high stability [9], and metabolomic biomarkers offer near real-time metabolic insights, enzymes strike a favorable balance between functional insight, detectability, and established clinical utility.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Enzyme Biomarkers in Key Disease Areas

| Disease Area | Representative Enzyme Marker(s) | Sensitivity Range | Specificity Range | Key Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Disease | 5'-nucleotidase, Alanine Aminotransferase | 70-90% | 85-95% | Hepatocellular damage assessment, disease monitoring |

| Cardiovascular Diseases | Creatine Kinase-MB, Troponin (protein biomarker for comparison) | 85-95% | 80-90% | Myocardial infarction diagnosis, reperfusion assessment |

| Cancer | N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase, Catalase [11] | 65-85% | 75-95% | Tumor subtyping, treatment response monitoring [11] |

| Neurological Disorders | Acetylcholinesterase, Neutral alpha-glucosidase [11] | 60-80% | 70-90% | Disease progression monitoring, therapeutic target |

| Metabolic Disorders | Acetate dehydrogenase [11] | 75-90% | 80-95% | Metabolic pathway assessment, treatment efficacy |

The experimental data compiled in Table 2 demonstrates that enzyme biomarkers consistently provide reliable sensitivity and specificity profiles across diverse disease areas, with particularly strong performance in metabolic and liver disorders. Their established role in clinical diagnostics underscores their reliability and translational potential compared to emerging biomarker classes that may still require extensive validation.

Experimental Protocols for Enzyme Biomarker Validation

Protocol 1: Enzyme Activity Assay for Clinical Validation

Objective: To quantitatively measure enzyme activity in biological samples for correlation with pathological states.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological samples (serum, plasma, tissue homogenates)

- Enzyme-specific substrate solutions

- Reaction buffers (pH-optimized)

- Cofactors (NAD+, ATP, metal ions as required)

- Standard enzyme preparations (for calibration curves)

- Protein assay reagents for normalization

- Stop solution (acid, base, or inhibitor as appropriate)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize tissue samples in ice-cold isotonic buffer (1:5 w/v ratio). Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Collect supernatant for analysis. For serum/plasma, use fresh or properly stored (-80°C) samples with minimal freeze-thaw cycles.

- Reaction Mixture Assembly: In a spectrophotometric cuvette or microplate well, combine:

- 50-100 μL sample (diluted appropriately)

- 200-800 μL reaction buffer (optimal pH and ionic strength)

- 10-100 μL substrate solution (saturating concentration)

- Cofactors/inhibitors as required

- Kinetic Measurement: Incubate at 37°C while continuously monitoring absorbance/fluorescence change at appropriate wavelength for 10-30 minutes. Ensure linear reaction kinetics by verifying correlation coefficient (R² > 0.95) for product formation versus time.

- Data Analysis: Calculate enzyme activity using the molar extinction coefficient of the product. Express activity as units/mg protein or units/L sample, where one unit represents conversion of 1 μmol substrate per minute under assay conditions.

- Validation Parameters: Determine linear range, intra-assay and inter-assay precision (CV < 10%), limit of detection, and recovery efficiency (85-115%).

This standardized protocol enables reliable quantification of enzyme activity, facilitating correlation with clinical parameters and comparison across patient cohorts in validation studies.

Protocol 2: Multiplex Enzyme Analysis for Biomarker Panels

Objective: To simultaneously measure multiple enzyme activities from limited sample volumes, enabling comprehensive biomarker profiling.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multiplex assay platform (Luminex, MSD, or similar)

- Enzyme-specific capture antibodies or substrates

- Detection reagents (fluorescent, chemiluminescent, or electrochemical)

- Assay buffers and wash solutions

- Standard curves for each enzyme

- Quality control samples

Methodology:

- Plate Preparation: Coat solid phase with capture molecules specific to target enzymes or their products. Block non-specific binding sites with appropriate blocking buffer (BSA, casein, or commercial blockers).

- Sample Incubation: Add samples and standards to designated wells. Incubate with shaking (2 hours, room temperature) to facilitate binding.

- Detection Step: Add detection reagents (enzyme-specific substrates with appropriate signal-generating systems). For activity-based detection, use fluorogenic or chromogenic substrates compatible with multiplex readout.

- Signal Measurement: Read plates using appropriate instrumentation (luminescence reader, fluorescence scanner, or electrochemical detector). Ensure spectral separation for multiplex detection.

- Data Analysis: Generate standard curves for each enzyme. Calculate activities from sample signals using curve-fitting algorithms. Normalize to sample protein content or internal standards.

Multiplex approaches significantly enhance the efficiency of enzyme biomarker validation by enabling parallel assessment of multiple candidates, conserving precious clinical samples, and providing comprehensive enzymatic profiles for disease stratification.

Visualizing Enzyme Biomarker Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Enzyme Biomarker Discovery and Validation Workflow

Diagram 1: Enzyme biomarker development workflow.

Enzyme-Centric Signaling Pathway Integration

Diagram 2: Enzyme biomarker pathway integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Biomarker Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Substrates | Chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates, Natural substrates with detection systems | Enzyme activity quantification | Selectivity, Km values, signal-to-noise ratio |

| Activity Assay Kits | Commercial enzyme activity kits (e.g., Catalase, Dehydrogenase) [12] | Standardized activity measurement | Optimization for sample matrix, linear range |

| Inhibitors/Activators | Specific chemical inhibitors, Monoclonal antibodies, Allosteric modulators | Mechanism of action studies | Specificity, concentration range, cellular toxicity |

| Detection Reagents | Antibodies, Fluorescent probes, Chemiluminescent substrates | Signal generation and amplification | Sensitivity, compatibility with instrumentation |

| Sample Preservation Solutions | Protease inhibitors, Stabilization buffers, Cryoprotectants | Pre-analytical sample integrity | Compatibility with downstream applications |

| Reference Standards | Recombinant enzymes, Calibrators, Quality control materials | Assay standardization and normalization | Purity, activity confirmation, stability |

| Solid Supports | ELISA plates, Bead-based arrays, Sensor surfaces | Immobilization and multiplexing | Binding capacity, non-specific binding |

| Signal Detection Systems | Spectrophotometers, Fluorometers, Luminescence readers [12] | Quantitative signal measurement | Dynamic range, detection limits, multiplex capability |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for successful enzyme biomarker validation. Commercial assay kits provide standardized protocols and consistency across experiments [12], while custom reagent systems offer flexibility for novel enzyme targets. The trend toward immobilized enzyme reactors represents a significant technological advancement, enhancing processing efficiency and enzyme stability for repeated analyses [12].

Enzyme biomarkers present a compelling rationale for continued investigation and application in clinical validation research, offering distinct advantages as sensitive and dynamic indicators of disease states. Their capacity to provide direct functional information through catalytic activity, coupled with established detection methodologies and favorable kinetic properties, positions them as valuable tools for diagnostic development and therapeutic monitoring. The integration of enzyme biomarkers with emerging technologies—including immobilized enzyme reactors [12], advanced machine learning approaches for specificity prediction [13], and multi-omics integration strategies [7]—promises to further enhance their utility in personalized medicine and precision diagnostics.

For researchers and drug development professionals engaged in biomarker validation, enzymes represent a class of biomarkers with strong translational potential, supported by extensive clinical precedent and continuously evolving methodological refinements. Their unique combination of dynamic responsiveness, functional relevance, and detectability makes them particularly well-suited for assessing therapeutic efficacy, monitoring disease progression, and guiding treatment decisions across diverse clinical contexts. As biomarker discovery and validation methodologies continue to advance, enzyme biomarkers will undoubtedly remain essential components of the clinical diagnostics arsenal, providing critical insights into physiological and pathological processes at the molecular level.

The field of enzymology is undergoing a transformative revolution, driven by converging advances in computational biology, high-throughput screening, and bioinformatics. novel enzyme discoveries are not only expanding our understanding of biological catalysis but are also paving the way for groundbreaking applications in therapeutics, diagnostics, and industrial biotechnology. This systematic review explores the current landscape of novel enzyme discovery, focusing on the sophisticated methodologies being employed to identify and validate these biological catalysts. Within the broader thesis of clinical validation, we examine how newly discovered enzymes are progressing from initial characterization to validated biomarkers and therapeutic targets, addressing the critical pathway from discovery to clinical implementation. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these emerging trends is essential for leveraging novel enzymes in diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

The significance of this field stems from the crucial roles enzymes play in health and disease. Enzymes represent a distinct class of proteins that exert specific catalytic functions within organisms, facilitating the acceleration of cellular chemical reactions and playing integral roles in biological processes including metabolism, digestion, DNA replication, and signal transduction [14]. The intricate balance of enzyme activity is vital for maintaining physiological homeostasis, and dysregulation of this balance has been implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases [14]. Consequently, enzyme inhibitors have emerged as important therapeutic drugs in clinical trials, with growing research interest from fields including endocrinology, pharmacology, and toxicology [14].

Natural Products as a Primary Source

Natural products continue to serve as a rich source for novel enzyme discoveries, with distinct structural classes emerging from various organisms. A comprehensive analysis of 226 novel enzyme inhibitors isolated between 2022-2024 reveals interesting patterns in structural distribution and bioactivity prevalence [14].

Table 1: Structural Classification of Novel Enzyme Inhibitors from Natural Products (2022-2024)

| Structural Class | Percentage (%) | Representative Enzymes Targeted | Noteworthy Bioactivities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | 31.0 | α-Glucosidase, α-amylase, protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B | Most prevalent class; diverse skeletons |

| Flavonoids | 18.0 | α-Glucosidase, cholinesterases | Significant antioxidant properties |

| Phenylpropanoids | 14.0 | Diacylglycerol acyltransferase 1 | Includes novel sesquineolignans |

| Alkaloids | 13.0 | α-Amylase, α-glucosidase | Indole alkaloids with potent inhibition |

| Polyketides | 5.0 | Tyrosinase | Neuropyrones A-C with strong activity |

| Peptides | 4.0 | Elastase, chymotrypsin, SARS-CoV-2 3CLPro | Thiazole-containing cyclic peptides |

| Others | 15.0 | Various enzymes | Quinonoids, phenols, heptanoids |

Among these structural classes, natural products exhibiting α-glucosidase inhibitory activity are the most prevalent, accounting for 27.9% of reported compounds, followed by inhibitors targeting α-amylase and protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B [14]. This distribution reflects the ongoing search for therapeutic interventions for metabolic disorders including diabetes and obesity.

Novel Enzymes from Gut Microbiota

The human gut microbiome has emerged as a fertile ground for novel enzyme discovery. A recent groundbreaking study identified a novel β-galactosidase enzyme (Bxy_22780) in the gut bacterium Bacteroides xylanisolvens that specifically targets unique galactose-containing glycans with potential prebiotic properties [15]. Unlike typical β-galactosidases, this enzyme exclusively targets galactooligosaccharides with β-1,2-galactosidic linkages, a specificity conferred by its unique structural architecture that perfectly positions substrates for breaking down these particular sugar chains [15]. This discovery highlights the potential for novel enzymes from gut microbiota to contribute to improved human gut health and the development of new therapeutic applications.

Computational and High-Throughput Approaches

Generative Models for Enzyme Design

The field of enzyme discovery has been revolutionized by computational approaches that generate novel enzyme sequences. Three contrasting generative models have shown particular promise:

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR): A phylogeny-based statistical model that traverses backward in evolution, often resulting in stabilized enzyme variants [16].

- Generative Adversarial Networks (ProteinGAN): A convolutional neural network with attention trained to generate novel functional sequences [16].

- Protein Language Models (ESM-MSA): Transformer-based models that generate new sequences via iterative masking and sampling from multiple sequence alignments [16].

Experimental validation of these computational approaches has revealed important insights. In a landmark study evaluating over 500 natural and generated sequences, researchers found that initial "naive" generation resulted in mostly inactive sequences, with only 19% of tested sequences showing activity above background levels [16]. However, ASR demonstrated superior performance, generating 9 of 18 active enzymes for copper superoxide dismutase and 10 of 18 for malate dehydrogenase [16]. This highlights both the promise and current limitations of computational enzyme design.

Diagram 1: Computational enzyme discovery and validation workflow. The COMPSS computational filter improved experimental success rates by 50-150% by evaluating sequences using alignment-based, alignment-free, and structure-based metrics [16].

Deep Learning for Kinetic Parameter Prediction

Accurate prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters is crucial for efficient enzyme exploration and modification. The CataPro deep learning model represents a significant advancement in predicting turnover number (k~cat~), Michaelis constant (K~m~), and catalytic efficiency (k~cat~/K~m~) [17]. This framework utilizes embeddings from pretrained protein language models (ProtT5) and molecular fingerprints (MolT5 embeddings and MACCS keys) to create robust predictions with enhanced accuracy and generalization capability compared to previous models [17].

The practical application of CataPro was demonstrated in an enzyme mining project where researchers identified an enzyme (SsCSO) with 19.53 times increased activity compared to the initial enzyme, subsequently engineering it to improve activity by an additional 3.34-fold [17]. This success highlights the transformative potential of deep learning approaches in accelerating both enzyme discovery and optimization.

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

Benchmarking Enzyme Activity

Rigorous experimental validation remains the cornerstone of novel enzyme discovery. Standardized protocols have been developed to assess the functionality of computationally generated enzymes:

Expression and Purification Protocol:

- Gene Cloning: Genes encoding novel enzyme variants are cloned into expression vectors optimized for industrial organisms like Escherichia coli [16].

- Protein Expression: Sequences are expressed in heterologous systems, with careful attention to potential issues including codon usage hindering expression [16].

- Purification: Recombinant proteins are purified using affinity chromatography techniques [16].

Activity Assay Conditions:

- Multimeric Enzymes: For complex proteins active as multimers (e.g., malate dehydrogenase and copper superoxide dismutase), activity is assessed using spectrophotometric readouts [16].

- Success Criteria: A protein is considered experimentally successful if it can be expressed and folded in E. coli and demonstrates activity above background in in vitro assays [16].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Novel Enzyme Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | Escherichia coli | Heterologous protein production | Codon optimization; avoidance of signal peptides |

| Activity Assays | Spectrophotometric enzyme assays | Quantifying catalytic function | Validation against background signals |

| Antibody Reagents | Polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies | ELISA development for biomarker validation | Epitope selection for native protein recognition |

| Analytical Platforms | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) | Detecting enzymatic reaction products | Essential for complex reaction monitoring |

| Stability Reagents | Protease inhibitors, stabilizers | Preserving biomarker integrity during storage | Critical for clinical translation |

Biomarker Validation Workflows

The clinical validation of novel enzyme biomarkers requires carefully orchestrated workflows, particularly when developing new immunoassays. A comprehensive workflow for ELISA development encompasses four critical phases [18]:

- Antibody Production: Including careful epitope selection and specificity testing

- ELISA Development: Optimizing antibody pairs and assay conditions

- ELISA Validation: Following established guidelines (e.g., JPND-BIOMARKAPD)

- Biomarker Clinical Assessment: Large cohort analysis and multi-center studies

This structured approach is essential for overcoming the significant challenge that while global protein profiling by mass spectrometry-based proteomics has identified an enormous number of biomarker candidates, most have not been validated, hampering their implementation in clinical practice [18].

Diagram 2: Biomarker validation workflow from discovery to clinical implementation. The process involves coordinated stages from initial discovery through assay development and final clinical validation [18].

Clinical Translation of Novel Enzyme Biomarkers

Emerging Enzyme Biomarkers in Clinical Trials

The translation of novel enzyme discoveries into clinically useful biomarkers represents a critical frontier in diagnostic medicine. A systematic review of studies from 2012-2023 identified 42 eligible articles reporting novel enzymes as potential biomarkers for various conditions [2]. These emerging biomarkers can be categorized into three primary applications:

- Tumor/Cancer Biomarkers: Including carbonic anhydrase XII for small cell lung cancer, focal adhesion kinase for acute myeloid leukemia, and thymidine kinase 1 for breast cancer [2].

- Tissue and Organ Function Assessment: Such as neutrophil elastase for microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes and matrix metalloproteinase 9 for intracerebral hemorrhage prognosis [2].

- Other Disease Conditions: Enzymes that assess medical conditions not confined to specific organs [2].

Most of these novel enzyme biomarkers belong to the hydrolase class and are measured primarily by methods that incorporate immunoassay principles, reflecting the need for standardized, reproducible detection methods suitable for clinical settings [2].

Validation Challenges and Considerations

The path from novel enzyme discovery to clinically validated biomarker is fraught with challenges that must be systematically addressed:

Analytical Validation Requirements:

- Assay Imprecision and Bias: Documentation of three types of imprecision—within-run, between-run, and total imprecision—is essential for interpreting results accurately [19].

- Blood Collection Considerations: Detection of circulating biomarkers begins with appropriate blood collection tubes and processing methods, as different anticoagulants (heparin, EDTA, citrate) can significantly affect results [19].

- Standardization and Harmonization: Development of reference methods and accepted reference materials enables results from different tests to be comparable across laboratories and over time [19].

Clinical Trial Design: Two principal objectives guide clinical trials of in vitro diagnostic devices: FDA clearance and documentation of the test's value in clinical practice. Trials aimed at regulatory approval typically follow the 510(k) route requiring demonstration of "non-inferiority" compared to existing tests [19]. Appropriate patient population selection is crucial, as enrolling individuals who are too healthy or too sick can compromise the trial's ability to demonstrate clinical value [19].

The landscape of novel enzyme discovery is rapidly evolving, propelled by synergistic advances in computational design, structural biology, and high-throughput experimentation. The integration of deep learning models like CataPro for kinetic parameter prediction with traditional experimental methods represents a powerful paradigm for accelerating both enzyme discovery and engineering [17]. Similarly, the development of computational filters such as COMPSS that improve experimental success rates by 50-150% demonstrates the growing sophistication of in silico prediction tools [16].

For clinical applications, the continued identification and validation of enzyme biomarkers holds promise for addressing unmet diagnostic needs across a spectrum of diseases. As the field progresses, several key trends are likely to shape future research:

- Multimarker Strategies: Combining multiple enzyme biomarkers to improve diagnostic and prognostic accuracy for complex diseases.

- Point-of-Care Applications: Development of rapid, simplified detection methods for novel enzyme biomarkers to enable decentralized testing.

- Personalized Medicine Approaches: Leveraging enzyme polymorphisms and individual metabolic variations to tailor therapeutic interventions.

In conclusion, the systematic exploration of novel enzymes through integrated computational and experimental approaches is yielding unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic development, diagnostic advancement, and industrial application. As validation methodologies become more sophisticated and computational predictions more accurate, the translation of these discoveries into clinically impactful tools is expected to accelerate, ultimately enhancing our ability to diagnose, monitor, and treat human diseases with greater precision and efficacy. The ongoing collaboration among researchers, clinicians, and industry stakeholders will be crucial for realizing the full potential of these novel enzyme discoveries in improving human health.

In the realm of drug development and clinical diagnostics, biomarkers serve as indispensable tools that provide a measurable window into biological processes, pathological states, or pharmacological responses to therapeutic interventions. As defined by the National Institutes of Health, a biomarker is "a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention" [4]. The clinical validation of novel enzyme biomarkers represents a critical pathway for advancing precision medicine, enabling earlier disease detection, more accurate prognosis, and improved therapeutic monitoring across diverse medical conditions.

The journey from understanding a biological mechanism to establishing a validated clinical marker requires rigorous scientific framework. This process begins with comprehending the fundamental role of enzymes in physiological and pathological processes, then systematically validating their measurement in accessible biological fluids, and ultimately demonstrating clinical utility for specific contexts of use. Enzymes, as biological catalysts with high substrate specificity, are particularly valuable as biomarkers since their activity in biological fluids can provide crucial information about the source and severity of cell and tissue damage [2]. This guide objectively compares emerging enzyme biomarkers against established alternatives, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and methodological frameworks to advance the field of clinical enzymology.

Biomarker Classification and Regulatory Framework

Categorical Distinctions of Clinical Biomarkers

Biomarkers are systematically categorized based on their clinical applications, with each category serving distinct purposes in the diagnostic and therapeutic pipeline. According to established clinical frameworks, biomarkers are classified into five primary types: (i) antecedent biomarkers that identify disease risk susceptibility; (ii) screening biomarkers for detecting subclinical disorders; (iii) diagnostic biomarkers for confirming manifest diseases; (iv) staging biomarkers for categorizing disease severity; and (v) prognostic biomarkers for predicting disease course, including recurrence and therapeutic response [4]. This classification system provides a structured approach for biomarker development and validation, ensuring that each biomarker is appropriately evaluated for its intended use context.

The clinical validity and utility of a biomarker depend fundamentally on its sensitivity, specificity, predictive values, and the precision with which it can be quantified [4]. For a biomarker to achieve regulatory acceptance and clinical adoption, it must demonstrate reliability, reproducibility, and feasibility across diverse patient populations. The validation process requires careful consideration of the biomarker's biological rationale, analytical performance, and clinical correlation, with regulatory guidelines continually evolving to ensure robust evidence-based evaluation.

Regulatory Pathways for Biomarker Qualification

The qualification of novel biomarkers for specific contexts of use represents a critical milestone in translational research. Regulatory agencies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have established formal biomarker qualification programs to evaluate and endorse biomarkers for defined applications in drug development [6]. This regulatory pathway typically requires extensive validation across multiple sites, demonstration of analytical robustness, and compelling evidence of clinical utility for the proposed context of use.

The recent qualification of glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH) as a biomarker for detecting drug-induced liver injury (DILI) in clinical trials exemplifies this process. After more than a decade of collaborative research led by the Predictive Safety Testing Consortium (PSTC), the FDA qualified GLDH specifically for detecting liver injury in patients with muscle disease or suspected muscle degeneration—a population where traditional liver enzymes like ALT and AST are confounded by muscle-specific expression [6]. This achievement highlights the importance of strategic collaboration among academia, industry, and regulatory agencies in advancing biomarker science.

Figure 1: Clinical Biomarker Validation Pathway from Biological Rationale to Adoption

Established vs. Novel Enzyme Biomarkers: Comparative Analysis

Limitations of Conventional Enzyme Biomarkers

Traditional enzyme biomarkers, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and creatine kinase (CK), have formed the cornerstone of clinical diagnostics for decades. These enzymes are routinely measured for assessing tissue damage in specific organ systems—ALT and AST for hepatic injury, and CK for muscle damage [2]. However, significant limitations have emerged with these conventional biomarkers, particularly regarding tissue specificity and diagnostic accuracy in complex clinical scenarios.

The case of ALT illustrates these limitations effectively. While ALT has served as the standard biomarker for detecting liver injury for decades, its specificity is compromised by its presence in muscle tissue. This limitation becomes particularly problematic in patient populations with concurrent muscle disease, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, where elevated ALT levels may reflect muscle damage rather than hepatotoxicity [6]. This lack of specificity can lead to misinterpretation of drug safety data in clinical trials and potentially inappropriate clinical management decisions. Similar limitations exist for other established enzyme biomarkers, creating a compelling need for more specific alternatives.

Emerging Novel Enzyme Biomarkers

Recent advances in enzymology and analytical technologies have enabled the discovery and validation of novel enzyme biomarkers with improved specificity and clinical utility. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of established enzyme biomarkers alongside their novel counterparts, highlighting key advantages and validation status.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Established vs. Novel Enzyme Biomarkers

| Organ System | Established Biomarker | Limitations | Novel Biomarker | Advantages | Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | ALT (Alanine Aminotransferase) | Non-specific; elevated in muscle disease [6] | GLDH (Glutamate Dehydrogenase) | Liver-specific; not confounded by muscle injury [6] | FDA-qualified for DILI detection in muscle disease patients [6] |

| Cancer | PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) | Limited specificity; false positives [4] | Thymidine Kinase 1 | Cellular proliferation marker; prognosis and therapy monitoring [2] | Clinical trials for breast cancer diagnosis, prognosis, therapy monitoring [2] |

| Neurological | Amyloid-β (Aβ42/40) | Requires PET or CSF; costly and invasive [20] | ptau-217 + Aβ42/40 combination | Blood-based; high accuracy for Alzheimer's pathology [20] | Clinical validation; predicts amyloid PET status with 91% sensitivity/specificity [20] |

| Hematological Malignancies | Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) | Non-specific; elevated in various conditions [4] | Separase | Chromosome segregation enzyme; disease progression marker in CML [2] | Flow cytometry method; prognostic applications in chronic myeloid leukemia [2] |

| Cardiovascular | Creatine Kinase (CK) | Non-specific; muscle origin [2] | Not specified in search results | Information limited | Under investigation |

The comparative data reveals a consistent pattern across organ systems: novel enzyme biomarkers address specific limitations of established markers, particularly through enhanced tissue specificity and improved correlation with pathological processes. The integration of biomarker combinations, such as the Aβ42/40 ratio with ptau-217 for Alzheimer's disease, demonstrates how multi-marker approaches can achieve diagnostic performance comparable to gold-standard methods while offering advantages in accessibility and scalability [20].

Methodological Approaches in Enzyme Biomarker Research

Analytical Techniques for Enzyme Biomarker Detection

The quantification of enzyme biomarkers employs diverse methodological approaches, each with distinct advantages for specific research and clinical applications. The selection of an appropriate analytical technique depends on factors including the enzyme's biochemical properties, required sensitivity and specificity, sample matrix, and intended throughput for clinical implementation.

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Enzyme Biomarker Detection and Validation

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Measured Parameter | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoassays | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) | Enzyme concentration or specific isoforms [2] | Quantification of carbonic anhydrase XII, focal adhesion kinase, thymidine kinase 1 [2] | High specificity; suitable for low-abundance enzymes | Measures mass rather than activity; antibody-dependent |

| Spectrophotometric Assays | Kinetic absorbance measurements | Enzyme activity via substrate conversion [2] | GLDH, γ-glutamyltransferase, thioredoxin reductase activity [2] | Direct activity measurement; continuous monitoring | Interference from sample components; substrate specificity critical |

| Separation-Based Methods | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Analytic ratio (Aβ42/40) with high precision [20] | Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio for Alzheimer's pathology [20] | High specificity and multiplexing capability | Technically demanding; expensive instrumentation |

| Fluorometric Assays | Fluorescence-based activity probes | Enzyme activity via fluorescent signals [2] | Caspase-3/7 activity in serum [2] | High sensitivity; suitable for low activity levels | Fluorescence interference; probe availability |

| Flow Cytometry | Cell-based analysis with fluorescent tags | Intracellular enzyme levels in specific cell populations [2] | Separase measurement in peripheral blood for CML [2] | Single-cell resolution; multiparameter analysis | Limited to cellular enzymes; complex sample processing |

The methodological landscape for enzyme biomarker analysis continues to evolve, with recent emphasis on high-throughput platforms that enable scalable clinical implementation. Mass spectrometry-based approaches, particularly liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), have gained prominence for their ability to precisely quantify multiple biomarkers simultaneously, as demonstrated in the combined measurement of Aβ42/40 ratio for Alzheimer's disease assessment [20]. Similarly, advanced immunoassay platforms now enable robust quantification of low-abundance enzyme biomarkers with the precision required for clinical decision-making.

Experimental Workflows for Biomarker Validation

The validation of novel enzyme biomarkers follows a structured experimental pathway that progresses from analytical validation to clinical confirmation. The workflow typically begins with assay development and optimization, followed by analytical validation to establish precision, accuracy, linearity, and reference ranges. This critical phase ensures that the measurement technique itself is reliable and reproducible before proceeding to clinical studies.

The subsequent clinical validation phase examines the biomarker's performance in well-characterized patient cohorts, establishing diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, prognostic value, or utility for therapy monitoring. For example, the validation of GLDH as a specific liver injury biomarker involved comparative studies in patients with and without muscle disease, demonstrating its superiority to ALT in distinguishing hepatic from muscular injury [6]. Similarly, the combination of plasma Aβ42/40, ptau-217, and APOE4 genotype was validated against amyloid PET imaging as the reference standard in a diverse cohort including patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease [20].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Enzyme Biomarker Analysis and Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research and development of enzyme biomarkers requires carefully selected reagents and materials that ensure analytical reliability and reproducibility. The following table summarizes essential components of the biomarker researcher's toolkit, with specific examples from recent studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Biomarker Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Samples | Serum, plasma, saliva, pleural fluid [2] | Matrix for enzyme measurement; different sample types for different applications | Serum for GLDH measurement [6]; plasma for ptau-217 [20]; pleural fluid for carbonic anhydrase XII [2] |

| Antibodies | Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies | Specific recognition and capture of target enzymes in immunoassays | ELISA for thymidine kinase 1, focal adhesion kinase [2] |

| Enzyme Substrates | Synthetic chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates | Enzyme activity measurement through product formation | Spectrophotometric substrates for GLDH, γ-glutamyltransferase [2] |

| Reference Standards | Recombinant enzymes, purified protein standards | Calibration and quantification reference | Mass spectrometry reference materials for Aβ42/40 ratio [20] |

| Sample Preparation Reagents | Protease inhibitors, stabilizers, extraction buffers | Preserve enzyme activity and structure during processing | Citrate-based anticoagulants for neutrophil elastase measurement [2] |

| Detection Reagents | Fluorescent probes, enzyme conjugates, detection antibodies | Signal generation and amplification in detection systems | Fluorometric caspase-3/7 substrates [2] |

| Separation Materials | LC columns, solid-phase extraction cartridges | Analytic separation and purification before detection | LC-MS/MS columns for Aβ42/40 measurement [20] |

The selection of appropriate reagents must align with the specific analytical platform and intended application. For example, mass spectrometry-based approaches require stable isotope-labeled internal standards for precise quantification, while immunoassays depend on high-specificity antibody pairs with minimal cross-reactivity. Similarly, sample collection materials must be carefully selected to preserve enzyme activity—certain anticoagulants can interfere with specific enzyme measurements, making standardized sample processing protocols essential for reproducible results.

The field of clinical enzymology continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in analytical technologies, improved understanding of disease mechanisms, and growing recognition of the need for more specific biomarkers. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates a clear trend toward tissue-specific enzymes that provide more accurate diagnostic and prognostic information compared to conventional markers. The successful regulatory qualification of GLDH for specific contexts of use establishes an important precedent for future biomarker development and highlights the value of collaborative consortia in advancing the field.

Future directions in enzyme biomarker research will likely focus on several key areas: First, the development of multi-marker algorithms that combine multiple enzymes or integrate enzymes with other biomarker classes (e.g., proteins, genetic markers) to achieve superior diagnostic performance, as exemplified by the combination of Aβ42/40, ptau-217, and APOE genotype for Alzheimer's disease [20]. Second, the continued refinement of high-throughput analytical platforms that enable cost-effective, scalable implementation in clinical practice. Third, the exploration of novel enzyme classes beyond traditional hydrolases and transferases, potentially including specialized enzymes from specific pathological processes.

As the biomarker landscape evolves, researchers and drug development professionals must maintain rigorous standards for analytical validation and clinical demonstration of utility. Through continued collaboration across academia, industry, and regulatory agencies, the translation of novel enzyme biomarkers from mechanistic insights to clinically valuable tools will accelerate, ultimately enabling more precise diagnosis, effective therapy selection, and improved patient outcomes across diverse disease areas.

In the era of precision medicine, biomarkers serve as critical measurable indicators for understanding biological processes, pathological states, and responses to therapeutic interventions [21]. Enzyme biomarkers, as biological catalysts, are particularly valuable due to their substrate specificity and the ability to relate their activity to concentration in biological fluids, providing vital information on the source and severity of cell and tissue damage [2]. The clinical utility of these biomarkers is defined by their specific intent: diagnostic biomarkers identify the presence of a disease, prognostic biomarkers forecast the natural course of a disease, predictive biomarkers estimate the likelihood of response to a specific treatment, and monitoring biomarkers are used to track disease status or treatment response over time [21]. This guide objectively compares the performance of novel and established enzyme biomarkers across these clinical intents, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a data-driven resource for clinical validation.

Comparison of Enzyme Biomarker Applications

The table below summarizes the clinical performance of various enzyme biomarkers, highlighting their specific applications and key performance metrics.

Table 1: Clinical Applications and Performance of Select Enzyme Biomarkers

| Enzyme Biomarker | Clinical Intent | Associated Disease/Condition | Specimen | Key Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thymidine Kinase 1 [2] | Diagnosis, Prognosis, Monitoring | Breast Cancer | Serum | Used for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy monitoring (Method: ELISA) |

| Caspase-3/7 [2] | Prognosis, Monitoring | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Serum | Prognosis and therapy monitoring (Method: Fluorometry) |

| γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) [2] | Prognosis | Advanced Urothelial Cancer | Serum | Serves as a prognostic indicator (Method: Spectrophotometry) |

| Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK), Src, PKC [2] | Diagnosis, Prognosis | Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | Serum | Used for diagnosis and prognosis (Method: ELISA) |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) [22] [2] | Diagnosis, Prognosis | Brainstem Glioma (BSG), Various Cancers | Serum, Saliva | Diagnostic model for BSG achieved an AUC of 0.933 in an independent blind test [22] |

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG) [23] | Predictive (Therapy Candidate) | Cancer (Glycolysis Inhibition) | N/A (Research Compound) | Used in enzyme kinetics studies to inhibit cancer cell metabolism; evaluated as an adjunct therapy |

| Neutrophil Elastase [2] | Prognosis | Type 2 Diabetes Microvascular Complications | Citrated Plasma | Serves as a prognostic indicator for complications (Method: ELISA) |

| Alanine Transaminase (ALT) [24] | Monitoring | Post-COVID-19 Liver Function | Serum | Levels showed a significant difference (p=0.002) between mild and severe post-COVID-19 cases |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Evaluation

Protocol for Serum-Based Metabolic Profiling in Brainstem Glioma

This protocol, used to identify diagnostic and prognostic metabolic enzyme biomarkers, is based on a study of brainstem gliomas (BSG) [22].

- Objective: To distinguish BSG patients from healthy donors (HDs) and predict patient survival using static and dynamic serum metabolic snapshots.

- Specimen Collection: Collect serum from a well-characterized patient cohort (e.g., 106 BSG patients and HDs). For dynamic monitoring, perform high-density, three-weekly blood draws prior to and during radiotherapy.

- Metabolite Profiling:

- Technology: Employ Nanoparticle-Enhanced Laser Desorption/Ionization Mass Spectrometry (NPELDI-MS).

- Procedure: Use ferric nanoparticles to enrich metabolites from native serum inputs (as small as 0.1 μL) without pretreatment. Analyze samples with a laser pulse frequency of 1000 Hz (approx. 2 seconds per sample).

- Data Analysis:

- Process raw MS spectra (e.g., 120,000 data points per sample) and filter features via quality control.

- Apply machine learning algorithms for diagnostic model building. Use a discovery set (e.g., n=99) for model training.

- Use shrinkage methods like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkation and Selection Operator) and Ridge for feature selection to identify top metabolite biomarkers (e.g., lactic acid, valine, leucine).

- Validate the classification model's performance (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, Area Under the Curve - AUC) on an independent validation set (e.g., n=34).

Protocol for Evaluating Computer-Generated Enzyme Sequences

This protocol is designed for the experimental validation of novel enzymes generated by computational models, a key step in biomarker and therapeutic development [16].

- Objective: To assess whether in silico-generated enzyme sequences are expressed, fold correctly, and are functionally active.

- Sequence Generation & Selection:

- Generate novel sequences using diverse computational models (e.g., Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction - ASR, Generative Adversarial Networks - GANs, Protein Language Models).

- Apply computational filters (e.g., the COMPSS framework) to select phylogenetically diverse sequences with a high probability of being functional.

- Expression and Purification:

- Clone the selected genes into an industrial expression system like Escherichia coli.

- Express and purify the proteins using standard recombinant DNA techniques (e.g., affinity chromatography).

- Functional Activity Assay:

- Perform in vitro activity assays with a spectrophotometric readout.

- For malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and copper superoxide dismutase (CuSOD), specific biochemical assays are used to measure catalytic activity.

- Success Criterion: Define an experimentally successful protein as one that is expressed and folded in E. coli and demonstrates activity significantly above background in the in vitro assay.

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Biomarker Clinical Translation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage pathway for translating a novel biomarker from discovery to clinical application, integrating key challenges and processes.

Experimental Validation Workflow

This flowchart details the key steps and decision points in the experimental protocol for validating novel enzyme biomarkers or generated enzyme sequences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and technologies used in the development and validation of enzyme biomarkers, as featured in the cited experimental protocols.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Technologies for Enzyme Biomarker Research

| Research Reagent / Technology | Primary Function in Research | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| U-PLEX Multiplexed Immunoassay Platform (MSD) [8] | Simultaneously measure multiple enzyme/protein biomarkers from a single, small-volume sample. | Used for efficient biomarker validation; offers superior sensitivity and a broader dynamic range compared to traditional ELISA. |

| NPELDI-MS(Nanoparticle-Enhanced LDI-MS) [22] | Pretreatment-free mass spectrometry for high-speed, high-throughput metabolic profiling using trace serum samples. | Employed to acquire comprehensive static and dynamic metabolic snapshots for diagnostic and prognostic model building. |

| LASSO & Ridge Regression [22] [21] | Machine learning-based feature selection methods to identify the most relevant biomarker combinations from high-dimensional data. | Critical for selecting optimal metabolic features (e.g., lactic acid, valine) to build parsimonious and effective diagnostic models. |

| COMPSS Framework(Composite Metrics for Protein Sequence Selection) [16] | A computational filter combining multiple metrics to predict the in vitro activity of computer-generated enzyme sequences. | Used to select phylogenetically diverse, functional enzyme sequences for experimental testing, improving success rates by 50-150%. |

| ESM-MSA, ProteinGAN, ASR Models [16] | Diverse generative models (Language Model, GAN, Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction) to create novel enzyme sequences. | Utilized to explore functional sequence diversity beyond natural proteins for novel biocatalyst and biomarker development. |

Advanced Assay Development and Strategic Application in Clinical Trials

The clinical validation of novel enzyme biomarkers demands analytical platforms that deliver uncompromising sensitivity, specificity, and precision. For decades, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) has been the workhorse technique in biomolecular analysis, valued for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and versatility in detecting specific proteins [25]. However, the emergence of precision medicine and the need to detect lower abundance biomarkers in complex matrices have revealed ELISA's limitations, including antibody cross-reactivity, limited dynamic range, and insufficient sensitivity for trace-level detection [25] [8].

Advanced platforms such as Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) are increasingly becoming the preferred choices for rigorous biomarker validation. These technologies offer transformative improvements in sensitivity, specificity, and multiplexing capabilities, enabling researchers to obtain more reliable and actionable data from precious clinical samples [8] [26]. This shift is further supported by evolving regulatory standards that emphasize more comprehensive validation data, including enhanced analytical validity and cross-validation techniques [27] [26]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these advanced platforms against traditional ELISA to inform method selection for enzyme biomarker research.

Technology Platform Comparisons

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) operates on the principle of antibody-antigen interaction, where the detection of a target molecule is achieved through an enzymatic reaction that produces a colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent signal. Its performance is heavily dependent on the quality and specificity of the antibody reagents used [25] [8].

LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) combines two powerful analytical techniques. Liquid chromatography first separates the components of a complex biological sample, which are then ionized and introduced into the mass spectrometer. The tandem mass spectrometer then precisely identifies and quantifies molecules based on their mass-to-charge ratio and characteristic fragmentation patterns [25] [28]. This method provides direct, molecule-by-molecule analysis, enabling the identification and quantification of biomolecules with high specificity.

MSD (Meso Scale Discovery) technology is an electrochemiluminescence-based detection method that shares similarities with ELISA in its use of antibody-antigen interactions. However, instead of colorimetric detection, MSD uses sulfo-tag labels that emit light upon electrochemical stimulation at the surface of electrodes embedded in the plate wells [29] [30]. This fundamental difference in detection methodology confers significant advantages in sensitivity and dynamic range.

Comparative Technical Specifications

Table 1: Technical comparison between ELISA, LC-MS/MS, and MSD platforms

| Feature | ELISA | LC-MS/MS | MSD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Antibody-antigen interaction with colorimetric detection | Separation by chromatography and mass-based detection | Antibody-antigen interaction with electrochemiluminescence detection |

| Sensitivity | Good for moderate concentrations | Excellent for trace-level detection (e.g., LOQ of 0.1 ng/mL for cotinine) [28] | High sensitivity (up to 100x greater than ELISA) [8] |

| Dynamic Range | 1-2 logs [29] | 3-4+ logs [25] | 3-4+ logs [29] [30] |

| Sample Volume Requirement | 50-100 μL (per analyte) [29] | Varies with method, typically low | 10-25 μL (for up to 10 analytes) [29] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited to single-plex | Moderate (requires method development) | High (up to 10 analytes simultaneously) [29] |

| Specificity | Can be affected by cross-reactivity [25] | Highly specific, distinguishes molecular isoforms [25] | High, with reduced cross-reactivity |

| Throughput | Moderate | Lower (multistep process) | High (fast read times: 1-3 minutes per plate) [29] |

| Matrix Effects | Susceptible to interference | Minimized through separation | Greatly reduced [29] [30] |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Quantitative Performance in Biomarker Detection

Direct comparative studies demonstrate the superior performance of advanced platforms in actual biomarker measurement applications:

Table 2: Experimental performance data comparing ELISA and LC-MS/MS for cotinine detection in children's saliva [28]

| Parameter | LC-MS/MS | ELISA |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | 0.1 ng/mL | 0.15 ng/mL |

| Geometric Mean (GeoM) of Cotinine | 4.1 ng/mL | 5.7 ng/mL |

| Range | ||

| Samples |

3% | 5% |

| Revealed Significant Associations | With sex and race/ethnicity | No significant associations with sex or race/ethnicity |

The study demonstrated that utilizing LC-MS/MS-based cotinine measurement revealed associations with sex and race/ethnicity of children that were not detectable using ELISA-based cotinine, highlighting the benefits of utilizing more sensitive assays when detecting low levels of exposure [28].

Correlation Between Methods

A 2025 study comparing isotope-dilution LC-MS/MS and a newly established ELISA for desmosine (an elastin degradation biomarker) found that while both methods exhibited a high correlation coefficient (0.9941), the ELISA measurements ranged from 0.83 to 1.06 times the theoretical values, whereas LC-MS/MS measurements initially showed approximately 2-fold deviations [31]. After recalibration using a corrected molar extinction coefficient, the LC-MS/MS measurements ranged from 0.68 to 0.99 times the theoretical values, demonstrating that both methods can achieve high accuracy with proper standardization [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

LC-MS/MS Methodology for Biomarker Quantification

The following workflow details a standardized approach for LC-MS/MS analysis of enzyme biomarkers, based on protocols used in comparative studies:

LC-MS/MS Workflow for Biomarker Analysis

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Internal Standard Addition: Add a known quantity of isotopically-labeled internal standard (e.g., 10 μL of 100 ppm isodesmosine-13C3,15N1) to 0.2 mL of sample to correct for variability in sample preparation and analysis [31].

- Protein Precipitation: Add organic solvents (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) to remove proteins and other interfering compounds.

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): Pass samples through conditioned SPE cartridges to concentrate analytes and remove additional matrix components [28].

Hydrolysis and Cleanup (for protein-bound biomarkers):

- Acid Hydrolysis: Heat samples with 6M HCl at 110°C for 16-24 hours to release protein-bound biomarkers [31].

- Cellulose Column Purification: Remove impurities using a cellulose column after hydrolysis. Wash with 3 mL of 1-butanol/acetic acid/H2O (4:1:1) three times, then elute target analytes with 3 mL of H2O [31].

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Chromatographic Separation: Use a C18 column (e.g., Luna C18) with gradient elution (typically water/acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) to separate analytes prior to mass spectrometry [28].

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Operate in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode, selecting specific precursor-to-product ion transitions for each biomarker and its internal standard.

- Quantitation: Generate calibration curves using the area ratio of analyte to internal standard, ensuring linearity with R² values >0.99 [31].

MSD Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay Protocol

MSD Assay Workflow

Assay Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Use MSD MULTI-ARRAY plates containing carbon electrode surfaces. Coat plates with capture antibody specific to the target biomarker (1-10 μg/mL in PBS overnight at 4°C) [30].

- Blocking: Block plates with 150 μL of blocking buffer (e.g., 3% BSA in PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) for 1-2 hours at room temperature with shaking.

- Sample Incubation: Add samples and standards (10-25 μL volume) to wells and incubate for 2 hours with shaking. MSD requires significantly less sample volume than ELISA - typically 10-25 μL for up to 10 analytes compared to 50-100 μL per analyte for ELISA [29].

- Detection Antibody Incubation: Add sulfo-tag labeled detection antibody and incubate for 1-2 hours with shaking.