From Experiment to Application: A Complete Guide to Determining the Michaelis Constant (Km)

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed roadmap for accurately determining the Michaelis constant (Km).

From Experiment to Application: A Complete Guide to Determining the Michaelis Constant (Km)

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed roadmap for accurately determining the Michaelis constant (Km). Spanning foundational theory, modern methodological approaches, practical troubleshooting, and advanced validation, the article synthesizes current best practices. It covers the derivation and interpretation of Km, evaluates traditional (Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee) and superior nonlinear estimation methods, addresses common experimental pitfalls, and explores the mechanistic interpretation of kinetic parameters in complex systems like drug transporters. The guide emphasizes the critical role of precise Km determination in characterizing enzyme-substrate affinity, interpreting inhibition mechanisms, and informing drug design and diagnostic development.

Decoding the Michaelis Constant: Definition, Derivation, and Core Significance

The Michaelis-Menten equation stands as the cornerstone of enzyme kinetics, providing an essential mathematical framework that describes the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity. At the heart of this model lies the Michaelis constant (Km), a parameter of profound theoretical and practical significance. Km quantifies the affinity between an enzyme and its substrate, defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity reaches half of its maximum value (Vmax) [1]. Its determination is critical for comparing enzyme variants, screening inhibitors, setting biologically relevant assay conditions, and parameterizing metabolic flux models in systems biology and synthetic biology [2] [3].

Accurate determination of Km is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for reliable research and development in biotechnology, drug discovery, and metabolic engineering. This technical guide examines the foundational model, explores traditional and innovative experimental methods for Km determination, and addresses the critical challenge of accuracy assessment in the context of modern enzyme research.

Theoretical Foundations: Derivation and Significance of the Michaelis-Menten Equation

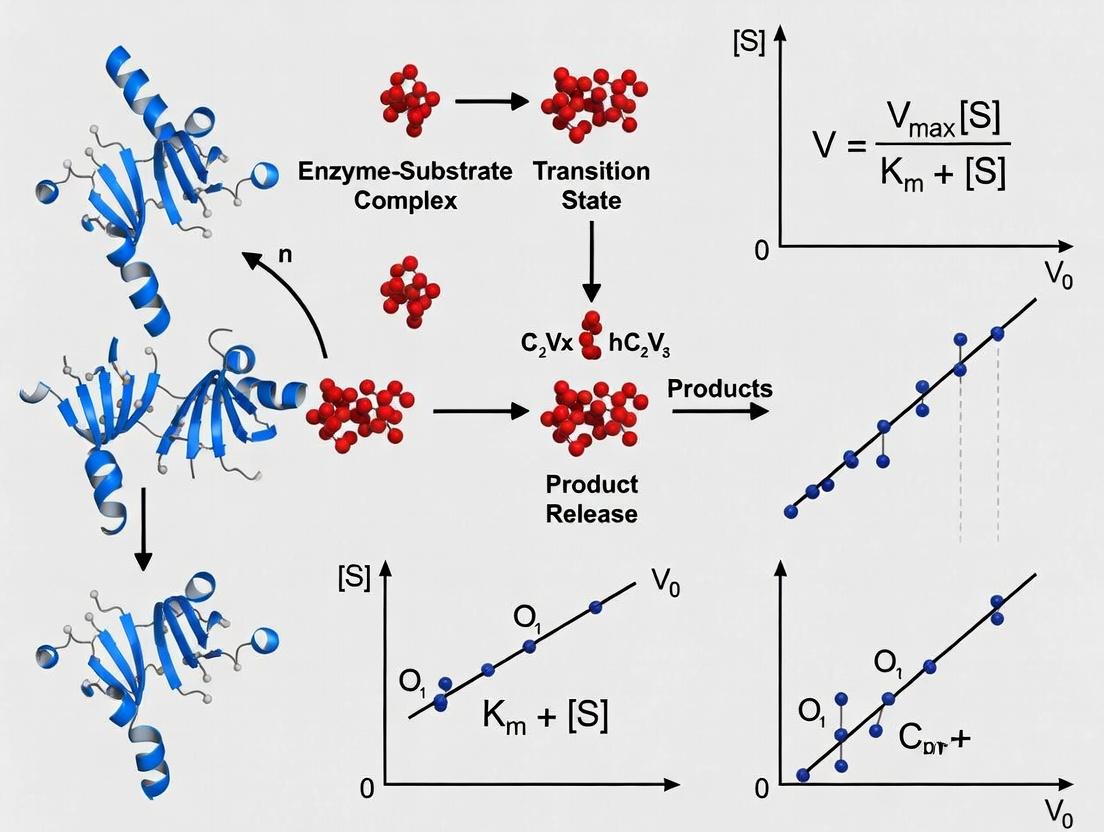

The standard Michaelis-Menten model is derived from a simplified scheme for enzyme-catalyzed reactions, involving the formation of an enzyme-substrate (ES) complex and its subsequent conversion to product.

Diagram 1: Michaelis-Menten enzyme catalysis mechanism.

The derivation applies the steady-state approximation, assuming the concentration of the ES complex remains constant over time. This leads to the classic Michaelis-Menten equation:

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])

Where:

- v is the initial reaction velocity.

- [S] is the substrate concentration.

- Vmax is the maximum reaction velocity, equal to kcat * [Etotal].

- Km is the Michaelis constant, equal to (k₋₁ + k_cat) / k₁.

Km serves multiple interpretative functions: it approximates the dissociation constant of the ES complex (when k_cat is much smaller than k₋₁), reflects enzyme-substrate affinity, and identifies the enzyme's optimal natural substrate from among several possibilities [1]. In metabolic pathways, the enzyme with the largest Km relative to prevailing substrate concentrations is often considered a rate-limiting step [1].

Experimental Determination of Km: Methodologies and Protocols

The direct experimental approach to determining Km involves measuring initial reaction velocities (v) across a wide range of substrate concentrations ([S]) and fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

3.1 Standard Kinetic Assay Protocol A generalized workflow for a spectrophotometric assay, a common method for reactions involving absorbance changes, is as follows [4] [1]:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the purified enzyme and serial dilutions of the substrate in an appropriate assay buffer (containing necessary cofactors, at optimal pH and temperature).

- Initial Rate Measurement: For each substrate concentration, initiate the reaction by adding a small, fixed volume of enzyme to the substrate-buffer mixture. The final enzyme concentration in the assay should be significantly lower than the Km to validly apply the steady-state assumption [5].

- Signal Monitoring: Immediately monitor the formation of product or disappearance of substrate over time (e.g., by absorbance, fluorescence) for a short initial period where the relationship is linear.

- Data Calculation: Calculate the initial velocity (v) for each [S] from the slope of the linear change in signal, converted to concentration units using an appropriate extinction coefficient or standard curve [4].

- Curve Fitting: Plot v against [S] and fit the data using non-linear regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain estimates for Vmax and Km. The Lineweaver-Burk double-reciprocal plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) is a linear transformation used historically but is prone to error propagation and is no longer recommended for fitting primary data [6].

3.2 Innovative Experimental Method: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Beyond optical methods, techniques like Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) offer label-free alternatives. A 2025 study demonstrated ITC for determining the specificity constant (Γ) of RUBISCO, which is related to the relative Km values for CO₂ versus O₂ [7].

- Protocol: The method involves titrating a CO₂/NaHCO₃ solution into a reaction cell containing RUBISCO, RuBP (substrate), and a fixed O₂ concentration. The heat flow (ΔrH) is measured for each injection.

- Data Analysis: The total measured enthalpy change varies with the substrate ratio ρ ([CO₂]/[O₂]) because the carboxylation and oxygenation reactions have distinct ΔrH values (-62.3 kJ/mol and -401 kJ/mol, respectively). By modeling ΔrH as a weighted sum of these two reaction enthalpies, where the weighting factor is a function of Γ and ρ, the value of Γ can be extracted through non-linear fitting [7].

- Advantage: This method avoids radioactive isotopes and provides a safe, high-throughput alternative for screening engineered RUBISCO variants [7].

The Critical Challenge: Assessing the Accuracy of Determined Km Values

A pivotal issue in modern kinetics is that a Km value obtained via standard nonlinear regression, while precise (with a small reported standard error, SE), can be substantially inaccurate. This inaccuracy arises primarily from systematic errors in the nominal concentrations of enzyme ([E₀]) and substrate ([S₀]) used in the assay, which are not accounted for in routine fitting procedures [2] [3].

4.1 The Accuracy Confidence Interval for Km (ACI-Km) Recent research has introduced the Accuracy Confidence Interval for Km (ACI-Km) framework to address this gap [2] [3]. This method treats the velocity-substrate relationship analogously to a binding isotherm. It propagates user-estimated uncertainties in [E₀] and [S₀] (e.g., from pipetting tolerances, stock solution calibration, or protein quantification methods) through the fitting process to generate a statistically robust interval that has a high probability of containing the true Km value.

- Workflow: Researchers input their kinetic data ([S] and v) and provide confidence intervals for the accuracy of their stock concentrations. The ACI-Km algorithm then calculates the probability distribution of plausible Km values arising from these concentration uncertainties.

- Output: The result is an accuracy confidence interval (e.g., 95% ACI) that quantifies the impact of systematic concentration errors on Km. A free web application (https://aci.sci.yorku.ca) automates this analysis [2].

Diagram 2: Workflow for accuracy assessment of Km (ACI-Km framework).

4.2 Traditional Precision vs. Modern Accuracy Assessment The following table contrasts the traditional and ACI-Km approaches to Km uncertainty.

Table 1: Comparison of Km Uncertainty Assessment Methods

| Aspect | Traditional Nonlinear Regression (Km ± SE) | ACI-Km Framework |

|---|---|---|

| What it Quantifies | Precision (Random Error): The reproducibility of the fit to the noisy velocity data. | Accuracy (Systematic Error): The propagation of systematic concentration uncertainties into the Km estimate. |

| Source of Uncertainty | Random noise in the measured reaction velocity (v) signals. | Systematic inaccuracies in the nominal enzyme ([E₀]) and substrate ([S₀]) concentrations. |

| Typical Software Output | Yes (Standard Error, SE, or confidence interval). | No. Requires specialized framework (e.g., ACI web app) [2]. |

| Primary Utility | Indicates data quality and fit reliability under the model. | Alerts researchers to when concentration calibration must be improved and provides a reliable Km range for downstream applications [3]. |

Computational Prediction of Km: The Rise of Deep Learning Models

To circumvent the expense and time of experimental kinetics, significant advances have been made in predicting Km values from sequence and structural data using deep learning (DL).

5.1 Model Architectures and Frameworks Models like UniKP and DLERKm represent the state of the art [8] [6]. These frameworks use multi-modal inputs:

- Enzyme Information: Amino acid sequence, processed by protein language models (e.g., ESM-2, ProtT5).

- Substrate/Product Information: Molecular structures represented as SMILES strings or fingerprints, processed by chemical language models (e.g., RXNFP) or graph neural networks.

- Contextual Data: Environmental factors like pH and temperature can be incorporated (e.g., in EF-UniKP) [8].

The models integrate these features using attention mechanisms and ensemble learners to output predictions for kcat, Km, and kcat/Km [8] [6].

Diagram 3: Deep learning framework for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters.

5.2 Performance and Application These models are trained on databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK. UniKP demonstrated the ability to distinguish wild-type enzymes from mutants and guide the discovery of high-activity tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) variants, with some showing a 3.5-fold higher catalytic efficiency than wild-type [8]. DLERKm, which incorporates product information, reported superior performance over previous models, highlighting the importance of full reaction information for accurate prediction [6].

Table 2: Representative Deep Learning Models for Km Prediction

| Model Name | Key Input Features | Architectural Highlights | Reported Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniKP [8] | Enzyme sequence, Substrate structure (SMILES), pH, Temp. | Pre-trained language models (ProtT5); Ensemble model (Random Forest/Extreme Trees). | Effectively identified high-activity TAL enzymes; EF-UniKP variant incorporates environmental factors. |

| DLERKm [6] | Enzyme sequence, Substrate & Product structures. | ESM-2 (enzyme), RXNFP (reaction), molecular fingerprints, channel attention. | Incorporating product information improved prediction metrics (e.g., R²) versus enzyme-substrate only models. |

| MPEK [6] | Enzyme sequence, Substrate structure, pH, Temp, Organism. | ProtT5 (enzyme), Mole-BERT (molecule), gating network. | Integrates multiple contextual factors for prediction. |

Integrated Discussion: From Foundational Model to Robust Parameterization

The journey from the classical Michaelis-Menten equation to reliable Km determination embodies the evolution of biochemical research. The equation's enduring strength is its conceptual clarity and practical utility. However, its effective application hinges on recognizing and addressing two modern realities.

First, experimental accuracy is paramount. The ACI-Km framework provides a crucial diagnostic tool, shifting the focus from purely statistical precision to a comprehensive assessment of accuracy. It alerts researchers when their workflow's concentration uncertainties unacceptably blur the biological signal, guiding investment in better calibration or experimental design [2] [3]. This is essential for making confident decisions in enzyme engineering or drug discovery.

Second, computational prediction is a transformative complement. Deep learning models like UniKP and DLERKm are overcoming historical data scarcity to provide fast, in silico estimates of Km [8] [6]. Their primary value lies in prioritization – screening vast protein sequence spaces or mutant libraries to identify the most promising candidates for wet-lab validation, drastically accelerating the design-build-test cycle in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology.

Therefore, a robust thesis on determining Km must advocate for a triangulated approach: using predictive models to generate intelligent hypotheses, executing carefully controlled kinetic experiments to test them, and applying accuracy assessment frameworks like ACI-Km to validate the reliability of the obtained parameters before they feed into higher-order biological models or industrial decisions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

| Item | Function & Specification | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Must be highly purified to avoid interfering activities and accurately quantify [E₀]. | Source (recombinant/native), purity (≥95% by SDS-PAGE), storage buffer, and documented specific activity. |

| Substrate | The molecule upon which the enzyme acts. A range of high-purity stock solutions is required. | Solubility in assay buffer, stability during assay, absence of inhibitory contaminants. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength). Includes necessary cofactors (Mg²⁺, NADH, etc.). | pH optimum, buffer capacity, chelating agents if needed, compatibility with detection method. |

| Detection System | Measures the time-dependent formation of product or disappearance of substrate. | Spectrophotometer/Fluorimeter: Requires a chromophore/fluorophore change [4]. Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (ITC): Measures heat change; label-free [7]. |

| Positive Control | A known enzyme with established Km for a standard substrate. | Validates the entire experimental and analytical workflow. |

| Inhibitor (for studies) | A molecule that reduces enzymatic activity, used to characterize enzyme mechanism. | Known type (competitive/non-competitive) and potency (Ki) [1]. |

| Software | For non-linear regression and advanced analysis (e.g., ACI-Km). | GraphPad Prism, Origin, or specialized tools like the ACI web application [2] [3]. |

The Michaelis constant (Kₘ) is a fundamental parameter in enzyme kinetics, quantitatively defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of the maximum velocity (Vₘₐₓ) [9]. This whitepaper frames the precise determination of Kₘ within the broader thesis of robust and reproducible enzyme characterization. Accurate Kₘ values are not mere academic exercises; they are critical for comparing enzyme variants, screening inhibitors, setting physiologically relevant assay conditions, and informing metabolic flux models in systems biology [3]. However, standard experimental and analytical practices can yield values that are precise (indicated by small standard errors) yet inaccurate, leading to potentially costly errors in drug development and bioprocess engineering [3]. This guide synthesizes the mathematical underpinnings, standard and advanced experimental protocols, and modern analytical frameworks essential for rigorous Kₘ determination.

Mathematical Definition and Derivation

The definition of Kₘ emerges from the Michaelis-Menten model of enzyme kinetics. The model is based on the fundamental reaction scheme where an enzyme (E) binds to its substrate (S) to form a complex (ES), which then yields product (P) and regenerates the free enzyme [10].

Core Assumptions for Derivation: Several steady-state assumptions are required: the concentration of the ES complex remains constant during the measured reaction period; the initial substrate concentration [S] vastly exceeds the total enzyme concentration [E]ₜ; and only the initial velocity (v), measured when product accumulation is negligible, is considered [11].

Derivation to the Michaelis-Menten Equation:

The rate of ES complex formation is given by k₁[E][S]. The rate of its breakdown is (k₋₁ + k₂)[ES]. Applying the steady-state assumption (rate of formation = rate of breakdown) gives:

k₁[E][S] = (k₋₁ + k₂)[ES]

Since the total enzyme is partitioned between free and bound states ([E]ₜ = [E] + [ES]), [E] can be substituted with ([E]ₜ - [ES]). Solving for [ES] yields:

[ES] = ([E]ₜ [S]) / ( (k₋₁+k₂)/k₁ + [S] )

The Michaelis constant Kₘ is defined as the composite rate constant (k₋₁ + k₂)/k₁ [11]. The observed reaction velocity v is proportional to [ES] (v = k₂[ES]), and the maximum velocity Vₘₐₓ occurs when all enzyme is saturated (Vₘₐₓ = k₂[E]ₜ). Substituting these relationships produces the Michaelis-Menten equation:

v = (Vₘₐₓ [S]) / (Kₘ + [S]) [10] [12]

Operational Definition of Kₘ:

When the reaction velocity v is half of Vₘₐₓ (v = Vₘₐₓ/2), the equation simplifies to:

Vₘₐₓ/2 = (Vₘₐₓ [S]) / (Kₘ + [S])

Solving for [S] confirms that Kₘ = [S] when v = Vₘₐₓ/2. Thus, Kₘ is the substrate concentration required for half-maximal enzymatic activity [9]. Graphically, it is the x-axis coordinate of the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten curve at the half-saturation point.

Diagram 1: Fundamental Enzyme Kinetic Pathway. This scheme shows the reversible formation of the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) and its irreversible catalysis to product, governed by rate constants k₁, k₋₁, and k₂.

Experimental Determination of Kₘ

Standard Initial Rate Method

The classical method involves measuring initial reaction velocities (v) at a minimum of six to eight different substrate concentrations spanning a range from approximately 0.2Kₘ to 5Kₘ [9].

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a master mix containing buffer, cofactors, and any fixed substrates. Maintain a constant, catalytically relevant temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C).

- Substrate Variation: Dispense aliquots of the master mix. Add a different concentration of the target substrate (the one for which Kₘ is being determined) to each reaction vessel. The highest concentration should aim to saturate the enzyme.

- Reaction Initiation: Start all reactions by adding a fixed, low concentration of enzyme. The enzyme must be the final component added to ensure accurate timing.

- Initial Velocity Measurement: Immediately monitor the appearance of product or disappearance of substrate for a short, linear period (typically ≤5% substrate conversion). Use a method appropriate for the reaction (e.g., spectrophotometry for NADH oxidation at 340 nm, fluorometry, or chromatography) [9].

- Data Collection: Record the slope of the linear progress curve for each [S] as the initial velocity (v), expressed in units like µM·s⁻¹.

Optimal Experimental Design: Research indicates that for progress curve analysis (a related method), the most precise estimate of Kₘ is obtained when the initial substrate concentration [S]₀ is chosen to be approximately 2 to 3 times the expected Kₘ value [13].

Data Analysis and Linear Transformations

The hyperbolic v vs. [S] data is fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression (preferred), often via software like GraphPad Prism or KaleidaGraph [9]. Historically, linear transformations are used for visualization and preliminary estimation.

Lineweaver-Burk Plot: The double-reciprocal plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) is the most common linear form. The y-intercept is 1/Vₘₐₓ, the x-intercept is -1/Kₘ, and the slope is Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ [14]. It is prone to distortion at low [S]. Eadie-Hofstee Plot: Plotting v vs. v/[S] yields a slope of -Kₘ and a y-intercept of Vₘₐₓ. This method spreads data more evenly but can be sensitive to experimental error. Hanes-Woolf Plot: Plotting [S]/v vs. [S] gives a slope of 1/Vₘₐₓ and an x-intercept of -Kₘ. It offers a better error structure than the Lineweaver-Burk plot.

Table 1: Comparison of Linear Transformations for Michaelis-Menten Analysis

| Plot Type | Axes | Slope | Y-Intercept | X-Intercept | Primary Advantage | Primary Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk | 1/v vs. 1/[S] | Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ | 1/Vₘₐₓ | -1/Kₘ | Intuitive, widely used. | Compresses data at high [S]; exaggerates error at low [S]. |

| Eadie-Hofstee | v vs. v/[S] | -Kₘ | Vₘₐₓ | Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ | Errors are not transformed, spreading data evenly. | Both variables depend on v, correlating errors. |

| Hanes-Woolf | [S]/v vs. [S] | 1/Vₘₐₓ | Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ | -Kₘ | Better error distribution than Lineweaver-Burk. | Less intuitive for direct parameter estimation. |

Advanced Method: Integrated Rate Equation (Progress Curve) Analysis

Instead of measuring multiple initial rates, this method fits a single progress curve (product vs. time) to the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation. One design proposes using an initial [S]₀ of 2-3Kₘ for optimal Kₘ estimation precision [13]. This method uses all data points from a single reaction but requires accounting for product inhibition and substrate depletion.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Determining Michaelis Constant (Kₘ). The process highlights two primary methodological paths converging on non-linear regression and modern accuracy assessment.

Quantitative Interpretation and Benchmarking

Kₘ values are expressed in molarity (M) and provide a measure of enzyme-substrate affinity. A lower Kₘ indicates higher apparent affinity, as less substrate is needed to achieve half-saturation. It is critical to note that Kₘ is not a direct dissociation constant (Kd) unless k₂ << k₋₁ (the rapid equilibrium assumption). In the standard steady-state derivation, Kₘ = (k₋₁ + k₂)/k₁, so it is always ≥ Kd [11].

Table 2: Representative Kₘ Values for Selected Enzymes and Substrates

| Enzyme | Substrate | Approximate Kₘ | Biological/Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexokinase IV (Glucokinase) | Glucose | 8-10 mM [9] | High Kₘ in liver allows sensing of blood glucose levels over a wide range. |

| Hexokinase I | Glucose | 0.05 mM [9] | Low Kₘ in muscle ensures efficient uptake/utilization even at low glucose. |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (Heart, LDH-B) | NADH (with pyruvate saturating) | ~5-15 µM (varies by isoform) [9] | Isozyme-specific Kₘ aids in tissue-specific metabolic control. |

| Carbonic Anhydrase | CO₂ | ~12 mM | High turnover number (k_cat) compensates for low apparent affinity. |

| β-Galactosidase | Lactose | ~0.8 mM | Reflects physiological concentration of its substrate. |

| Acetylcholinesterase | Acetylcholine | ~0.1 mM | Efficient clearance of neurotransmitter at the synapse. |

Practical Implications and Advanced Considerations

Inhibition Kinetics

Kₘ is a key diagnostic parameter in characterizing enzyme inhibitors [9]:

- Competitive Inhibition: Inhibitor competes with substrate for the active site. Apparent Kₘ increases, Vₘₐₓ remains unchanged.

- Non-Competitive Inhibition: Inhibitor binds elsewhere, reducing effective enzyme concentration. Apparent Vₘₐₓ decreases, Kₘ remains unchanged.

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: Inhibitor binds only to the ES complex. Both apparent Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ decrease.

The Critical Challenge of Accuracy vs. Precision

A pivotal 2025 study highlights a major gap in standard practice: traditional non-linear regression reports the precision of Kₘ (standard error, SE) but not its accuracy—the closeness to the true value. Systematic errors in the nominal concentrations of enzyme ([E]₀) and substrate ([S]₀) can lead to Kₘ estimates that are precise but highly inaccurate [3].

Solution: The Accuracy Confidence Interval (ACI) Framework: This modern framework treats Kₘ determination analogously to a binding-isotherm regression. It propagates user-estimated uncertainties in [E]₀ and [S]₀ (e.g., from pipetting, stock solution preparation) to calculate an ACI that is expected to contain the true Kₘ value with a specified confidence level [3]. This is crucial for valid comparisons (e.g., between enzyme mutants) and reliable decision-making in drug discovery. A free web application automates this analysis [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Kₘ Determination Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function in Kₘ Assay | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst under study. Its concentration must be known accurately and kept constant across all [S] conditions. | Purity and activity must be validated. Stock concentration error is a major source of inaccuracy in Kₘ [3]. |

| Target Substrate | The reactant whose concentration is varied to determine Kₘ. | High-purity stock with accurately known concentration is essential. Serial dilutions must be prepared precisely. |

| Cofactors (e.g., NADH, Mg²⁺) | Essential for the catalytic activity of many enzymes. | Must be included at saturating, non-limiting concentrations when not the variable substrate [9]. |

| Reaction Buffer | Maintains optimal and constant pH, ionic strength, and chemical environment. | Buffer composition and pH can significantly affect enzyme kinetics and must be controlled. |

| Coupled Assay Enzymes (if used) | Used in indirect assays to continuously monitor product formation (e.g., linking ATP production to NADH oxidation). | Must be in excess to ensure the measured rate is limited only by the primary enzyme. |

| Spectrophotometer/Fluorometer | Instrument for monitoring the reaction progress (e.g., absorbance change of NADH at 340 nm). | Must have stable temperature control and precise timers for initial rate measurements. |

| Microplate Reader or Cuvettes | Reaction vessels. | Ensure path length is known and consistent for accurate concentration calculations from absorbance. |

The rigorous determination of the Michaelis constant (Kₘ) is a cornerstone of quantitative enzymology with profound implications for basic research and applied biotechnology. While its mathematical definition as [S] at half-Vₘₐₓ is elegantly simple, obtaining an accurate and meaningful value demands careful experimental design, appropriate data analysis, and—as underscored by the latest research—an awareness of the distinction between precision and true accuracy [3].

Future research in this field, as part of a comprehensive thesis on Michaelis constant determination, should focus on the widespread adoption of accuracy-assessment frameworks like ACI, the development of standardized reporting guidelines that include uncertainty budgets for [E]₀ and [S]₀, and the integration of these robust kinetic parameters into predictive computational models of cellular metabolism. By moving beyond reporting only a Kₘ value with a standard error to reporting a value with a validated Accuracy Confidence Interval, researchers can ensure their findings are reliable, reproducible, and truly informative for downstream applications in drug development and systems biology.

Within the framework of a broader thesis on determining the Michaelis constant (Km), this guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the two principal theoretical approaches used to derive this fundamental kinetic parameter. The Michaelis constant is a cornerstone of enzymology, quantitatively describing the relationship between an enzyme's catalytic rate and substrate concentration [15]. Its accurate determination is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to characterize enzyme mechanisms, understand metabolic pathways, and design effective inhibitors [16] [17].

The canonical Michaelis-Menten equation, v₀ = (Vmax[S])/(Km + [S]), describes a hyperbolic relationship where v₀ is the initial velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, and Vmax is the maximum velocity [10] [18]. The parameter Km, the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax, can be interpreted differently based on the underlying mathematical assumptions used in its derivation [19]. The two classical derivations—the Rapid Equilibrium Approximation and the Steady-State (or Briggs-Haldane) Approximation—rest on different premises about the behavior of the enzyme-substrate complex (ES). These derivations yield identical mathematical forms for the rate equation but assign distinct biochemical meanings to Km [20] [19]. This whitepaper will dissect these methodologies, detail associated experimental protocols, and explore advanced modern approaches for robust Km determination.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Derivations

The basic reaction scheme for a single-substrate, irreversible enzyme-catalyzed reaction is:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P

where E is the free enzyme, S is the substrate, ES is the enzyme-substrate complex, and P is the product. The rate constants are defined as k₁ (forward binding), k₋₁ (dissociation of ES), and kcat (or k₂, the catalytic rate constant for product formation) [10] [18].

The Rapid Equilibrium (Michaelis-Menten) Derivation

The rapid equilibrium approximation assumes that the binding step (E + S ⇌ ES) is significantly faster than the catalytic step (ES → E + P). Consequently, the enzyme, substrate, and complex are considered to be in instantaneous equilibrium [20] [18]. The equilibrium dissociation constant for the ES complex, Ks (often synonymous with Kd), is defined as:

Ks = [E][S]/[ES] = k₋₁/k₁

By applying the enzyme conservation equation ([E]₀ = [E] + [ES]) and recognizing that the initial velocity v₀ = kcat[ES], algebraic substitution leads to the familiar Michaelis-Menten equation:

v₀ = (kcat[E]₀[S]) / (Ks + [S])

In this derivation, the Michaelis constant Km is explicitly equal to the dissociation constant Ks (or Kd). Therefore, Km is a true thermodynamic equilibrium constant, inversely related to the enzyme's affinity for the substrate: a lower Km indicates tighter binding [19] [21].

The Steady-State (Briggs-Haldane) Derivation

The steady-state approximation, formulated by Briggs and Haldane, is a more general condition. It assumes that over the measurable course of the reaction, the concentration of the ES complex remains constant because its rate of formation equals its rate of consumption [22]. This does not require the binding step to be at equilibrium. The steady-state condition is expressed as: d[ES]/dt = 0 = k₁[E][S] – (k₋₁ + kcat)[ES]. Again, using the enzyme conservation law and v₀ = kcat[ES], solving for [ES] yields: v₀ = (kcat[E]₀[S]) / ([(k₋₁ + kcat)/k₁] + [S]) The equation is identical in form to the rapid equilibrium result, but the Michaelis constant is now defined as: Km = (k₋₁ + kcat) / k₁ In this framework, Km is a kinetic parameter, not a pure equilibrium constant. It represents the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax, but its relationship to binding affinity (Kd = k₋₁/k₁) is modulated by the catalytic rate kcat [19].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Derivation Assumptions and Outcomes

| Aspect | Rapid Equilibrium Approximation | Steady-State Approximation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Assumption | The enzyme-substrate binding step is at instantaneous equilibrium. | The concentration of the ES complex is constant over time (formation rate = breakdown rate). |

| Condition | k₋₁ >> kcat. Substrate dissociation is much faster than catalysis. | No specific requirement on the relative magnitudes of k₋₁ and kcat. More general. |

| Definition of Km | Km = Ks = k₋₁/k₁ | Km = (k₋₁ + kcat)/k₁ |

| Relationship to Kd | Km is identical to the dissociation constant Kd. | Km ≥ Kd. They are equal only if kcat << k₋₁. |

| Physical Meaning | A pure thermodynamic binding constant. Measure of substrate affinity. | A kinetic constant representing [S] at ½Vmax. Governed by both binding and catalysis. |

| Primary Citation | Michaelis & Menten (1913) [18] | Briggs & Haldane (1925) [22] [17] |

Table 2: Quantitative Implications of the Relationship Between Km and Kd

| Condition | Mathematical Relationship | Practical Implication for Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| kcat << k₋₁ (Slow Catalysis) | Km ≈ Kd | Km reliably reflects substrate binding affinity. Rapid equilibrium assumption is valid. |

| kcat ≈ k₋₁ | Km > Kd | Km overestimates the true binding affinity (Kd). |

| kcat >> k₋₁ (Fast Catalysis) | Km >> Kd | Km is a poor indicator of binding affinity. Steady-state assumption is essential. |

| General Case | Km / Kd = 1 + (kcat/k₋₁) | The ratio quantifies the deviation; Km is always greater than or equal to Kd [19]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Determining Km

Accurate determination of Km relies on measuring initial reaction velocities (v₀) across a range of substrate concentrations while maintaining a constant, low enzyme concentration to meet the model's assumptions [15] [17].

Initial Velocity (Progress Curve) Assays

The classical method involves measuring the initial linear phase of product formation or substrate depletion for multiple reactions, each with a different initial [S]₀. Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Mixture: Prepare a master mix containing all non-varying components (buffer, cofactors, salts, enzyme). The buffer must control pH, as it significantly affects enzyme activity and Km [23].

- Initiation: Dispense aliquots of the master mix into vessels containing varying concentrations of substrate. Start the reaction by adding enzyme or substrate, ensuring rapid mixing.

- Continuous Monitoring: Use a spectrophotometer, fluorometer, or other detector to monitor the change in signal (e.g., absorbance of product) over time, typically for the first 5-10% of substrate conversion.

- Initial Rate Calculation: Determine the slope of the linear portion of the progress curve for each [S]₀. This slope is v₀, expressed in concentration/time (e.g., µM/s) [15].

- Data Fitting: Plot v₀ vs. [S]₀ and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression, which is the preferred and most accurate method. Alternatively, linear transformations like the Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) can be used but are sensitive to experimental error [10] [23].

Advanced & Computational Approaches

Modern methods address limitations of the classic assay, such as the requirement for high substrate concentrations or prior knowledge of Km.

- Total Quasi-Steady-State Approximation (tQSSA): For conditions where the standard assumption ([E]₀ << [S]₀ + Km) is violated (e.g., in vivo or high-enzyme conditions), the tQSSA model provides a more robust framework for analyzing full progress curves without being restricted to initial rates [17].

- Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC): A likelihood-free statistical method that can estimate Km and kcat from a single progress curve, reducing reagent use and time. It is particularly useful when enzyme or substrate is limiting [16].

- Response Surface Methodology (RSM): A statistical technique that models Km and Vmax as functions of multiple interacting environmental variables (e.g., pH, temperature, inhibitor concentration) simultaneously, providing a more comprehensive understanding of enzyme behavior under different conditions [23].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Experimental Determination of Km

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Km Determination Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function & Purpose | Critical Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst under investigation. Source (recombinant, tissue) and purity are critical for reproducible kinetics. | Maintain activity: store in appropriate buffer, often at -80°C with stabilizers (e.g., glycerol, BSA). Aliquot to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme. Must be highly pure and compatible with the detection method. | Solubility at high concentrations can be limiting. Prepare fresh stock solutions to avoid hydrolysis/oxidation. Use kinetic, not thermodynamic, solubility. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength, providing optimal and stable enzyme activity. | Choice of buffer (e.g., Tris, phosphate, HEPES) depends on enzyme and pKa. Include essential cations (Mg²⁺, etc.) and DTT to prevent oxidation. |

| Detection System | Quantifies the formation of product or depletion of substrate over time. | Spectrophotometric: Requires a chromogenic change (NADH at 340 nm is common). Fluorometric: Higher sensitivity (e.g., fluorogenic substrates). Coupled Assay: Uses a second enzyme to generate a detectable signal [15] [23]. |

| Positive Control | Validates the functionality of the assay system. | A known substrate or an enzyme batch with previously characterized Km. |

| Inhibitor/Negative Control | Confirms signal specificity. | A reaction lacking enzyme or containing a known specific inhibitor to measure non-enzymatic background. |

| Microplate Reader / Spectrophotometer | Instrument for high-throughput or cuvette-based kinetic measurements. | Must have precise temperature control (e.g., Peltier) and rapid mixing capabilities. Software for initial rate calculation is essential. |

| Data Analysis Software | For non-linear regression and statistical analysis of kinetic data. | Tools like GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot, or dedicated packages for Bayesian (ABC) or tQSSA analysis [16] [17] [23]. |

Advanced Kinetic Models and Future Directions

The standard Michaelis-Menten model, while foundational, has limitations. Advanced models extend its utility:

- Total Quasi-Steady-State Approximation (tQSSA): As implemented in modern Bayesian approaches, this model remains accurate even when enzyme concentration is not negligible compared to substrate and Km, a common scenario in cellular environments. It allows for the pooling of data from experiments with different enzyme concentrations, leading to more robust parameter estimation [17].

- Single-Molecule Kinetics: Moves beyond ensemble averages to observe the stochastic behavior of individual enzyme molecules, revealing heterogeneities and transient states masked in traditional assays.

- Machine Learning Integration: Emerging techniques use large kinetic datasets to predict Km values or identify novel modulators, accelerating drug discovery and enzyme engineering.

Diagram 2: Evolution of Kinetic Models Beyond Classic Michaelis-Menten

The derivation of Km via the steady-state or rapid equilibrium approximation is not merely a historical or academic distinction; it has profound implications for the interpretation of this ubiquitous parameter. The rapid equilibrium derivation posits Km as a direct measure of substrate binding affinity (Kd). In contrast, the more general steady-state derivation defines Km as a kinetic constant that incorporates both binding (k₁, k₋₁) and catalytic (kcat) efficiency. For the practicing scientist, the choice of experimental design and data analysis model—from classic initial velocity assays to modern tQSSA and Bayesian methods—should be informed by the system's biochemistry and the specific conditions of the experiment. Accurate Km determination remains a vital endeavor, providing indispensable insights for basic enzymology, drug discovery, and understanding the kinetic constraints of biological networks.

The Michaelis constant (Km) is far more than a simple curve-fitting parameter extracted from a hyperbolic plot. It is a fundamental descriptor of enzyme function that sits at the intersection of biochemistry, cellular physiology, and quantitative systems biology [15]. Its accurate interpretation is critical for tasks ranging from designing basic enzyme assays to constructing predictive metabolic models and designing targeted therapeutics [24]. Misinterpretation of Km can lead to flawed biological conclusions or inefficient biotechnological processes. This guide frames the multidimensional interpretation of Km within the broader thesis of rigorous Michaelis constant research, emphasizing that understanding what Km means is inextricably linked to understanding how it is reliably determined and the conditions under which it is measured [2] [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a nuanced grasp of Km is essential for selecting enzyme variants, screening inhibitors, and predicting in vivo enzyme behavior from in vitro data [6].

Theoretical Foundations: The Dual Interpretations of Km

The Km value, defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax, admits two primary interpretations, each valid under specific mechanistic assumptions [15] [25].

The Operational Definition: A Measure of Apparent Affinity

The most common and robust interpretation is operational. A lower Km value indicates that an enzyme achieves half its maximum velocity at a lower substrate concentration. This is widely described as the enzyme having a higher apparent affinity for its substrate [26] [27]. Conversely, a higher Km suggests lower apparent affinity. This interpretation is always valid when using the Michaelis-Menten equation to describe steady-state kinetics, regardless of the underlying reaction mechanism [28]. It is immensely useful for comparing different enzymes or the same enzyme under different conditions (pH, temperature, presence of inhibitors).

The Mechanistic Definition: Relating to Rate Constants

Under a specific and common mechanistic condition—where the dissociation of the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) back to enzyme and substrate is much faster than the formation of product (i.e., k₋₁ >> k₂)—Km simplifies to k₋₁/k₁ [25] [28]. In this scenario, Km approximates the dissociation constant (Kd) of the ES complex. This equates Km directly with binding affinity: a lower Km reflects a tighter, more stable ES complex. It is crucial to recognize that this is a special case. In the full Michaelis-Menten derivation (Km = (k₋₁ + k₂)/k₁), Km is a function of both binding (k₁, k₋₁) and catalytic (k₂) rate constants. Therefore, while Km often correlates with affinity, it is more accurately a "specificity constant" that reflects an enzyme's efficiency at low substrate concentrations [29].

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Km Interpretations

| Interpretation | Definition | Key Assumption | Primary Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational (Apparent Affinity) | [S] at which v₀ = Vmax/2 [15] | Steady-state conditions | Comparing enzymes & conditions; assay design |

| Mechanistic (Dissociation Constant) | Km ≈ k₋₁/k₁ [25] | k₋₁ >> k₂ (rapid equilibrium) | Relating kinetics to binding thermodynamics |

| Efficiency (Specificity Constant) | Inverse related to kcat/Km [29] | Low [S] conditions | Gauging catalytic perfection & in vivo relevance |

Km in Research and Applied Contexts

Diagnostic Tool in Enzyme Inhibition Studies

Changes in Km are a primary diagnostic for determining the mechanism of enzyme inhibition, which is fundamental to pharmacology and drug discovery [27].

- Competitive Inhibition: The inhibitor competes with the substrate for the active site. This increases the apparent Km (more substrate is needed to reach half-saturation), while Vmax remains unchanged [26] [27].

- Non-Competitive & Mixed Inhibition: The inhibitor binds at an allosteric site. Vmax is decreased, while Km may remain unchanged (pure non-competitive) or either increase or decrease (mixed) [27].

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: The inhibitor binds only to the ES complex. This paradoxically decreases the apparent Km (stabilizes ES binding) while also decreasing Vmax [27].

Table 2: Effect of Inhibitor Types on Kinetic Parameters

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site | Effect on Vmax | Effect on Apparent Km | Diagnostic Clue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Active Site | Unchanged | Increases [27] | Reversible by high [S] |

| Non-Competitive | Allosteric Site | Decreases | Unchanged [27] | Not reversed by high [S] |

| Uncompetitive | ES Complex | Decreases | Decreases [27] | Rare; common in multi-substrate rxn |

| Mixed | Allosteric Site | Decreases | Increases or Decreases [27] | Complex kinetics |

Physiological Relevance and the Critical Link to In Vivo Conditions

A Km value's most significant biological meaning lies in its relationship to physiological substrate concentrations [24]. An enzyme's Km relative to the in vivo concentration of its substrate ([S]_physio) dictates its operational point on the activity curve and its sensitivity to substrate fluctuations.

- If [S]_physio << Km: The enzyme operates in the first-order range, where velocity is highly sensitive to changes in substrate concentration. This is typical for regulated enzymes controlling metabolic flux.

- If [S]_physio ≈ Km: The enzyme operates at half its capacity, allowing for potent regulation by factors that modestly alter Km or [S].

- If [S]_physio >> Km: The enzyme is nearly saturated and operates at near-maximal velocity (zero-order kinetics), buffering its activity against substrate changes.

Therefore, interpreting a Km value in isolation is of limited use. Its true physiological meaning emerges from comparison with actual cellular substrate levels. This underscores a major challenge in enzyme kinetics: many reported Km values are derived from assays under non-physiological conditions of pH, temperature, buffer, and ionic strength, which can alter Km significantly and limit their biological predictive power [24].

Methodological Framework: Determining Accurate and Meaningful Km Values

Core Experimental Protocol for Reliable Km Determination

The following detailed protocol is based on standard steady-state kinetics and highlights critical steps for generating reliable data.

1. Initial Rate Assay Establishment:

- Principle: Km and Vmax are defined using initial velocities (v₀), measured when [S] >> [E] and product accumulation is minimal (<5% of [S]), ensuring [S] is constant and reverse reactions/product inhibition are negligible [24] [28].

- Procedure: For each substrate concentration, prepare a reaction mixture with all components except the initiating reagent (e.g., enzyme or cofactor). Pre-incubate at the assay temperature. Initiate the reaction and monitor product formation or substrate depletion continuously (via spectrophotometry, fluorometry) or at multiple early time points. Plot signal vs. time; the linear slope is v₀.

2. Substrate Concentration Range Selection:

- Use a minimum of 8-10 different substrate concentrations, spaced appropriately to define the hyperbolic curve. The range should ideally span 0.2-5.0 times the estimated Km to capture both the first-order and zero-order regions [15].

3. Data Analysis and Curve Fitting:

- Plot v₀ versus [S]. Fit the data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v₀ = (Vmax*[S])/(Km + [S])) using non-linear regression [2].

- Critical Consideration: While the Lineweaver-Burk double-reciprocal plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) linearizes the data, it disproportionately weights data points at low [S], which often have the highest error. It should be used for visualization and inhibitor diagnosis, not as the primary fitting method [15].

4. Accuracy Assessment (ACI-Km Framework):

- Recent advancements stress that a small standard error (SE) from regression does not guarantee accuracy. Systematic errors in enzyme or substrate concentration ([E]₀, [S]₀) propagate into Km [2].

- Apply the Accuracy Confidence Interval for Km (ACI-Km) [2]. This method uses estimated intervals for [E]₀ and [S]₀ accuracy (from calibration, reagent specs) to calculate a probabilistic interval for Km, providing a more reliable bound for decision-making. A free web application (https://aci.sci.yorku.ca) implements this.

Advanced & Emerging Methodologies

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): Directly measures binding affinity (Kd) and thermodynamics, providing a complementary view to kinetic Km.

- Computational Prediction (Deep Learning): Models like DLERKm now predict Km values from enzyme sequence and substrate/product structures, useful for high-throughput screening and metabolic engineering [6]. These models use pre-trained language models (e.g., ESM-2 for proteins) and reaction fingerprints as inputs.

Table 3: Overview of Computational Km Prediction Methods

| Model Name | Core Architecture | Key Input Features | Reported Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| DLERKm [6] | ESM-2, RXNFP, Attention | Enzyme seq, Substrate, Product | Incorporates product info for first time |

| UniKP [6] | ProtT5, SMILES Transformer | Enzyme seq, Substrate | Ensemble model for robustness |

| MPEK [6] | ProtT5, Mole-BERT | Enzyme seq, Substrate, pH, Temp | Includes environmental factors |

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Km Determination

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance | Considerations for Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Source (recombinant, purified native) and purity affect specific activity and stability. | Accurate quantification of active site concentration ([E]₀) is critical but challenging. Use activity titrations where possible [2]. |

| Characterized Substrate | The molecule whose transformation is studied. Purity and stability are paramount. | Accurate preparation of stock concentrations ([S]₀) is a major source of systematic error. Use certified standards and precise gravimetry [2]. |

| Physiomimetic Assay Buffer | Maintains pH, ionic strength, and provides necessary cofactors. | Buffer composition (e.g., phosphate vs. Tris) can activate or inhibit enzymes [24]. Strive for physiological relevance (pH, ions, temperature). |

| Detection System | Measures product formation/substrate depletion (e.g., spectrophotometer, fluorometer, HPLC). | Must have sufficient sensitivity and a linear range suitable for measuring low initial velocities. |

| Reference Databases | Sources for literature values and metadata (e.g., BRENDA, SABIO-RK, STRENDA) [24]. | Essential for comparison. STRENDA guidelines promote reporting standards for reproducibility [24]. Always note EC number and organism [29]. |

Interpreting Km requires a multidimensional perspective that integrates its operational definition as an apparent affinity constant, its mechanistic relationship to rate constants, and, most importantly, its physiological context relative to in vivo substrate concentrations. Robust Km determination hinges on meticulous initial-rate experiments, awareness of systematic errors in concentration measurements, and the application of modern accuracy assessment frameworks like ACI-Km [2].

Future research in this field will increasingly bridge high-accuracy experimental determination with computational prediction and machine learning models [6]. The ultimate goal is to generate Km values that are not just precise numbers from an in vitro assay, but accurate parameters that can reliably predict enzyme behavior in the complex, crowded, and regulated environment of the living cell, thereby accelerating rational drug design and metabolic engineering.

Key Assumptions of the Model and Their Experimental Implications

The determination of the Michaelis constant (Km) is a cornerstone of quantitative enzymology, providing critical insights into enzyme-substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency. This parameter, defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of its maximum (Vmax), is not a direct physical measurement but an estimated constant derived from a kinetic model [18] [9]. The foundational model for this estimation is described by the Michaelis-Menten equation, v = (Vmax[S])/(Km + [S]), which relates the initial velocity (v) of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction to the substrate concentration ([S]) [18] [30].

The practical and accurate determination of Km is entirely contingent upon experimental conditions that satisfy the key assumptions underpinning this model. Violations of these assumptions lead to systematic errors, misestimation of kinetic parameters, and flawed conclusions about enzyme mechanism or inhibitor potency [31] [32]. Therefore, a rigorous understanding of these assumptions—their theoretical basis, their practical limitations, and the experimental protocols designed to uphold them—is essential for any researcher engaged in characterizing enzymes, designing drugs, or interpreting kinetic data. This guide details these core assumptions, their modern interpretations, and the consequent experimental imperatives for valid Km determination.

The Core Assumptions: Derivation and Modern Interpretation

The canonical Michaelis-Menten model for a single-substrate, irreversible reaction is represented by the mechanism: E + S ⇌ ES → E + P, where k1 and k-1 are the rate constants for complex formation and dissociation, and kcat (or k2) is the catalytic rate constant [18] [10].

Table 1: Foundational Assumptions of the Michaelis-Menten Model

| Assumption | Mathematical Statement | Theoretical Implication | Historical vs. Modern View |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial Velocity (v₀) | Measurement at t≈0, [P]≈0 | Negligible product inhibition or reverse reaction [30]. | Originally used to circumvent product inhibition [33]; remains absolute. |

| 2. Steady-State (Briggs-Haldane) | d[ES]/dt = 0 | [ES] remains constant over measurement period [30]. | More general than rapid equilibrium; widely applied [18]. |

| 3. Free Ligand Approximation | [S]₀ ≈ [S]₀total | Total substrate far exceeds bound substrate ([S]₀ >> [E]₀). | Common but not strictly necessary for equation form [32]. |

| 4. Single Catalytic Pathway | One ES complex forms one product | Model excludes multiple intermediates or substrates. | Simplification; deviations require more complex models. |

The derivation of the rate equation employs the steady-state assumption for the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) [30]. Contrary to common teaching, recent analysis clarifies that the valid application of the Michaelis-Menten equation for parameter estimation requires not just the steady-state condition, but the more specific reactant stationary assumption (RSA). The RSA posits that during the initial transient phase where [ES] builds up, the substrate concentration remains approximately constant and equal to its initial value [S]₀ [32]. This is distinct from and a prerequisite for the steady-state condition in practical experiments.

A critical modern refinement concerns the relationship between enzyme concentration ([E]₀) and Km. Traditional teaching emphasizes [S]₀ >> [E]₀. However, computational and theoretical work defines a more precise validity boundary: the Michaelis-Menten equation yields accurate estimates of Km and Vmax only when [E]₀ is ≤ 0.01 Km [31]. At higher enzyme concentrations (0.01Km < [E]₀ < Km), the system still follows a hyperbolic relationship, but with a different equation, and estimates from the standard plot become inaccurate [31].

Diagram: The Michaelis-Menten Reaction Mechanism. The central, reversible formation of the ES complex is key to the model's assumptions.

Experimental Implications & Validity Criteria

The theoretical assumptions impose strict, testable criteria on experimental design. Failure to meet these criteria is a major source of error in reported kinetic parameters.

Table 2: Experimental Implications of Model Assumptions

| Assumption | Experimental Implication | Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Velocity (v₀) | Measure velocity at earliest possible time (typically <5% substrate conversion). Use continuous or rapid-quench methods. | Product inhibition, curvature in progress curves, underestimation of true Vmax and inaccurate Km [33]. |

| Reactant Stationary (RSA) | Ensure measurement period is short relative to ES complex buildup time. This often implicitly requires [S]₀ >> [E]₀. | The derived hyperbolic equation does not accurately describe v₀ vs. [S]₀ data, leading to biased parameter fits [32]. |

| [E]₀ ≤ 0.01Km | Use enzyme concentration sufficiently low relative to the unknown Km. May require iterative pilot experiments. | Significant systematic error in estimated Km and Vmax. The error increases as [E]₀/Km ratio increases [31]. |

| Constant [E]₀ | Enzyme must be stable and fully active throughout assay. Include stability controls. | Apparent activity loss over time, leading to non-linear progress curves and underestimation of rate. |

| No Inhibitors/Activators | Purify substrate, use high-purity buffers, account for solvent effects. | Altered apparent Km and Vmax, potentially misinterpreted as allosterism or alternate mechanism. |

The most quantitatively defined criterion is the [E]₀ to Km ratio. Research demonstrates that to keep the estimation error for Km and Vmax below ~10% using standard initial rate experiments, the total enzyme concentration must be ≤ 1% of the Km value [31]. This is a more stringent condition than often applied in practice. For an enzyme with a Km of 10 µM, [E]₀ should be 100 nM or lower. This constraint can conflict with the need for a detectable signal, necessitating sensitive detection methods.

Diagram: Workflow for Valid Km Determination. The iterative check on enzyme concentration is critical for parameter accuracy.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Km Determination

Standard Initial Velocity Method

This is the most common method, directly applying the model's assumptions [9].

Protocol:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a master mix containing buffer, cofactors, and any essential salts. Prepare a dilution series of substrate (typically 6-8 concentrations spanning 0.2Km to 5Km). Prepare enzyme stock at a concentration such that the final [E]₀ in the assay is ≤ 0.01 × the suspected Km [31].

- Assay Initiation: Aliquot substrate solutions into cuvettes or microplate wells. Add master mix. Initiate reactions by adding a small volume of enzyme stock with rapid mixing.

- Initial Rate Measurement: Immediately begin monitoring product formation (e.g., via absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) for a short period (typically 30-120 seconds). Ensure ≤ 5% of substrate is consumed during this period to maintain the initial velocity condition [33].

- Data Analysis: Plot initial velocity (v₀) against substrate concentration ([S]₀). Fit the data directly to the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation (v₀ = (Vmax[S]₀)/(Km + [S]₀)) using non-linear regression software. Avoid using linearized plots (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk) for primary analysis, as they distort error structure [33].

Fixed-Point (Time-Point) Method

This method is useful when continuous monitoring is impractical or when substrate depletion is problematic for initial rate measurement [34].

Protocol:

- Reagent Preparation: As in Section 4.1.

- Reaction Incubation: Initiate multiple, identical reactions at different [S]₀. Instead of monitoring continuously, stop each reaction at a fixed, precise time (t) after initiation (e.g., via acid quench, heat denaturation, or inhibitor).

- Product Quantification: Measure the total amount of product [P] formed in each quenched reaction.

- Data Transformation & Analysis: The measured [P] is related to initial velocity by v₀ ≈ [P]/t, provided t is short. However, a more robust approach is to use the equation: t = (Km/Vmax) * ln([S]₀/([S]₀-[P])) + [P]/Vmax. By measuring [P] at a fixed t for various [S]₀, Km and Vmax can be estimated by fitting to this integrated form, which accounts for substrate depletion [34] [33].

Protocol for Validating the [E]₀ Criterion

Given the critical importance of the [E]₀ ≤ 0.01Km rule [31], the following validation step is recommended.

Protocol:

- Perform an initial parameter estimate using the standard method (Section 4.1) with the lowest feasible [E]₀.

- Using the estimated Km(est), calculate 0.01 * Km(est).

- If your assay [E]₀ was greater than this value, repeat the experiment with a lower enzyme concentration. If signal-to-noise becomes too low, a more sensitive detection method is required.

- Confirm that the final estimated Km is stable and does not systematically shift when [E]₀ is further reduced.

Table 3: Common Methods for Estimating Km and Vmax

| Method | Procedure | Primary Data Plot | Advantages | Disadvantages & Assumption Checks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Linear Regression (Direct) | Fit v₀ vs. [S]₀ to hyperbolic function. | v₀ vs. [S]₀ (Hyperbolic) | Most accurate; proper error weighting. | Requires good initial parameter guesses. Must verify [E]₀ ≤ 0.01Km [31]. |

| Lineweaver-Burk (1/v vs. 1/[S]) | Linear transformation of MM equation. | Double-reciprocal plot (Linear) | Easy visualization; reveals inhibition type. | Poor statistical practice: compresses low [S] data, magnifies error. Use for visualization only [33]. |

| Eadie-Hofstee (v vs. v/[S]) | Alternative linear transformation. | v vs. v/[S] (Linear) | Error distribution better than L-B. | Still less reliable than direct fit. Sensitive to experimental scatter. |

| Integrated Rate Equation Fit | Fit full time-course data for single [S]₀ or fit [P] at fixed t for multiple [S]₀. | [P] vs. time (Progress Curve) | Uses all data points; accounts for depletion. | Computationally complex; assumes no product inhibition or enzyme instability [33]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Michaelis Constant Determination

| Reagent/Material | Function & Purpose | Critical Considerations for Valid Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Highly Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Concentration must be known (active concentration is ideal). | Stability is key. Must remain fully active during assay to satisfy constant [E]₀ assumption. Use fresh aliquots and activity controls. |

| Substrate Stock Solutions | The reactant. Prepared at high concentration for dilution series. | Purity is essential to avoid inhibitors. Concentration must be accurately determined. Solubility must allow for [S]₀ >> [E]₀ condition. |

| Appropriate Assay Buffer | Maintains constant pH, ionic strength, and provides necessary cofactors (Mg²⁺, etc.). | Must not contain inhibitors. Must optimize pH for activity. Buffering capacity must be high enough to withstand reaction byproducts. |

| Detection System Reagents | Enables quantification of product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., NADH, chromogenic/fluorogenic probes, coupling enzymes). | Must be in excess to not be rate-limiting. Coupling enzymes must have high activity to avoid lag phases, violating initial rate condition. |

| Positive Control Inhibitor (Optional) | A known inhibitor (e.g., a transition-state analog) for assay validation. | Verifies that measured activity is specific to the enzyme's active site. Useful for troubleshooting. |

| Sensitive Detection Instrument | Spectrophotometer, fluorometer, or luminescence plate reader capable of rapid, precise measurement. | Sensitivity is paramount to allow work at very low [E]₀ (≤ 0.01Km) [31]. Rapid sampling is needed for true initial rate. |

The process of determining the Michaelis constant is not a simple curve-fitting exercise but a rigorous test of whether an enzyme's behavior conforms to a fundamental physical model under specified conditions. The key assumptions—particularly the reactant stationary assumption and the stringent limit on enzyme concentration relative to Km—are not mere historical footnotes but active constraints that dictate modern experimental design [31] [32].

For researchers in drug discovery, violating these constraints can lead to mischaracterizing inhibitor mechanisms (e.g., misclassifying competitive vs. non-competitive) or incorrectly calculating inhibitor potency (Ki). For enzymologists, accurate Km and kcat values are essential for understanding evolutionary optimization, as the specificity constant (kcat/Km) is the fundamental measure of catalytic efficiency [18].

Therefore, robust Km determination requires: 1) A priori planning to ensure ultra-low enzyme concentrations, 2) Validation that progress curves are linear at all substrate concentrations, and 3) Analysis using direct nonlinear fitting of the hyperbolic equation. Adherence to these principles, rooted in the model's core assumptions, ensures that the extracted Michaelis constant is a true reflection of enzyme biochemistry rather than an artifact of flawed kinetics.

Km Determination in Practice: From Classic Plots to Modern Nonlinear Regression

The determination of the Michaelis constant (Km) is a cornerstone of quantitative enzymology, providing critical insights into enzyme-substrate affinity, catalytic mechanism, and cellular metabolic regulation [35]. Within the broader context of thesis research focused on Km determination, the accurate measurement of the initial reaction velocity (v) and the strategic planning of the substrate concentration range ([S]) are not merely preliminary steps but the foundational pillars upon which reliable kinetic parameters are built. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for designing these core experiments, emphasizing principles essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to characterize enzymes, identify inhibitors, or engineer biocatalysts [36] [37].

The widely accepted Michaelis-Menten model describes the hyperbolic relationship between v and [S], defined by the equation v = (Vmax [S]) / (Km + [S]), where Vmax is the maximum velocity [10] [35]. The Km value, defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax, is a key parameter for comparing enzymes from different sources and understanding their physiological context [36]. For competitive inhibitor screening—a primary goal in drug discovery—assays must be conducted with substrate concentrations at or below the Km to ensure sensitivity to inhibition [36]. Consequently, a well-founded experimental design to measure v and establish a valid [S] range is indispensable for generating robust, publication-quality kinetic data that can inform downstream applications in biotechnology and therapeutics.

Theoretical Foundations: Defining Initial Velocity and Its Imperative

The Concept and Critical Importance of Initial Velocity

The initial velocity (v) of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction is defined as the rate measured during the very early phase of the reaction, specifically when less than 10% of the substrate has been converted to product [36]. Under these conditions, several critical assumptions of the Michaelis-Menten model hold true: the substrate concentration ([S]) remains essentially constant, the accumulation of product (and thus any potential product inhibition or contribution of the reverse reaction) is negligible, and the enzyme-substrate complex [ES] is in a steady state [36] [35].

Adherence to initial velocity conditions is non-negotiable for valid steady-state kinetic analysis. Failure to do so leads to significant artifacts and erroneous parameter estimation [36]:

- Non-linearity with Enzyme Concentration: The reaction rate ceases to be directly proportional to the amount of active enzyme present.

- Uncertain Actual Substrate Concentration: The depletion of substrate makes the starting [S] an inaccurate representation of the conditions during measurement.

- Invalid Kinetic Treatment: The fundamental mathematical derivations of the Michaelis-Menten equation break down, rendering fitted Km and Vmax values unreliable.

The Integrated Rate Equation: An Alternative Approach

While the measurement of initial velocities from the linear portion of progress curves is the classical and most common method, a robust alternative exists. The integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation (Eq. 2: t = [P]/Vmax + (Km/Vmax) · ln([S]0/([S]0 - [P]))) allows for the determination of Km and Vmax by analyzing the complete time course of a single reaction, even when a substantial fraction (theoretically up to 70%) of the substrate is consumed [38]. This method is particularly advantageous when experimental constraints make frequent early time-point sampling difficult, such as with discontinuous assays using HPLC or electrophoretic methods [38]. It is crucial to verify that the enzyme remains stable and that no inhibition (by product or excess substrate) occurs during the extended reaction time when using this approach [38].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Establishing Initial Velocity Conditions: The Reaction Progress Curve Experiment

The first practical experiment in any kinetic characterization is to define the time window over which initial velocity conditions are met for a specific enzyme under specific assay conditions.

Detailed Protocol:

- Prepare Reaction Mixtures: Set up a series of reactions with a fixed, saturating substrate concentration (e.g., [S] > 5 Km, if a literature value exists) and at least three different enzyme concentrations (e.g., a 2-fold serial dilution series) [36].

- Initiate and Monitor Reaction: Start the reaction by adding enzyme and immediately begin continuous monitoring of product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., via spectrophotometry, fluorimetry).

- Generate Progress Curves: Record the signal over time until the reaction clearly reaches a plateau (substrate exhaustion).

- Analyze for Linearity: Plot the concentration of product (or change in signal) versus time for each enzyme concentration. Identify the early time segment where the progress curve is linear for all enzyme concentrations tested.

- Define the Valid Time Window: The initial velocity (v) for subsequent experiments is the slope of this linear region. The duration of this linear phase dictates the maximum allowable reaction time for all future assays [36]. As shown in foundational texts, reducing the enzyme concentration can extend the period of linearity by slowing substrate depletion [36].

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for Initial Velocity Determination

| Parameter | Recommended Design | Rationale & Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Conversion | < 10% [36] | Maintains constant [S]; prevents product inhibition; validates steady-state assumption. |

| Enzyme Concentration | Varied (e.g., 3-4 levels) [36] | Identifies a linear time window common to all [E]; ensures v is proportional to [E]. |

| Reaction Time Course | Continuous monitoring preferred [39] | Allows accurate identification of the linear phase; detects lag/burst phases or instability. |

| Control for Background | Include "no enzyme" and/or "no substrate" controls [36] | Corrects for non-enzymatic substrate decay or signal background. |

Planning the Substrate Concentration Range forKmDetermination

Once the linear time window is established, the next step is to design the substrate matrix to generate a saturation curve for fitting Km and Vmax.

Detailed Protocol:

- Determine the Approximate Range: Ideally, use a literature-reported Km as a guide. In its absence, run a preliminary experiment with 6 substrate concentrations spanning a broad range (e.g., 0.1 µM to 1000 µM) to get an initial estimate [36].

- Design the Final Concentration Series: Based on the preliminary estimate, prepare a minimum of 8 substrate concentrations spaced unevenly to provide more data points near the Km. The range should typically bracket the Km, from 0.2 × Km to 5.0 × Km [36]. For a more optimized design that minimizes error in the Km estimate, research suggests using an initial substrate concentration of approximately 2 to 3 times the Km value when employing integrated progress curve analysis [40].

- Run the Saturation Experiment: For each [S], run the reaction in triplicate within the pre-determined linear time window. Measure the initial velocity (v).

- Ensure Excess Substrate: The total enzyme concentration [E]0 must be significantly less than the lowest [S] tested (typically [S]/[E] > 100) to satisfy the steady-state assumption [36].

Table 2: Substrate Concentration Range Design for Kinetic Analysis

| Analysis Goal | Recommended [S] Range | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Km/Vmax Estimate | 6 concentrations, broad log-scale (e.g., 0.1-100 µM) [36] | Captures the full transition from first-order to zero-order kinetics. |

| Accurate Km/Vmax Fit | 8+ concentrations from ~0.2Km to ~5Km [36] | Provides high-density data in the most sensitive part of the hyperbola. |

| Competitive Inhibitor Screening | [S] ≤ Km (typically [S] = Km) [36] | Maximizes assay sensitivity to inhibitor competition; using [S] >> Km masks inhibitor potency. |

| Progress Curve Analysis | Initial [S]₀ ≈ 2-3 Km [40] | An experimentally efficient design for extracting parameters from a single time course. |

The Critical Role of Enzyme Concentration

A frequently overlooked but critical factor is the absolute concentration of enzyme used. The classic Michaelis-Menten equation assumes [E]₀ << [S]₀ and [E]₀ << Km. Recent rigorous analysis provides a quantitative boundary: for initial rate experiments to yield accurate Km and Vmax through the standard Michaelis-Menten equation, the enzyme concentration should be ≤ 1% of the Km value (i.e., [E]₀ ≤ 0.01 Km) [31]. At higher enzyme concentrations (0.01 Km < [E]₀ < Km), the kinetics deviate and require a more complex equation for description [31]. This constraint is essential for planning experiments, especially with high-activity enzymes or when using precious substrates at concentrations near their Km.

Validating the Assay: Controls and Best Practices

A robust experimental design includes validation steps:

- Linearity of Detection: Before kinetic experiments, establish that the detection system (e.g., spectrophotometer) responds linearly to product concentration across the expected range [36].

- Enzyme Stability (Selwyn's Test): Verify that the product plateau level in progress curves is proportional to the enzyme concentration. Non-proportionality indicates enzyme instability during the assay [36] [38].

- Positive Control Inhibitor: For inhibitor screening assays, include a well-characterized competitive inhibitor to confirm the assay yields the expected potency (IC₅₀ or Kᵢ).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Fitting Kinetic Data

The preferred method for determining Km and Vmax is non-linear regression of the untransformed data (v vs. [S]) to the Michaelis-Menten equation [35]. While linear transformations like Lineweaver-Burk plots are historically noted, they distort error distribution and are less reliable for parameter estimation. Modern software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot) performs this non-linear fitting efficiently, providing estimates with standard errors.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Poor Fit to Hyperbola: May indicate substrate inhibition at high [S], cooperativity, or the presence of an isozyme mixture.

- Abnormally High Km: Could suggest suboptimal assay conditions (pH, missing cofactor/activator) or that a surrogate, rather than the natural, substrate is being used [36].

- Irreproducible Km: Check enzyme purity and stability, and ensure lot-to-lot consistency of all reagents [36].

Advanced and Computational Approaches

The experimental determination of Km can be resource-intensive. The field is now augmented by computational prediction tools powered by deep learning. These models use enzyme sequence and substrate structure (often encoded as SMILES strings) to predict kinetic parameters [6] [37]. Frameworks like UniKP employ pre-trained language models for proteins (e.g., ProtT5) and substrates to create feature vectors, which are then processed by ensemble machine learning models (e.g., extra trees) to predict Km, kcat, and kcat/Km with significant accuracy [37]. More recent models like DLERKm further incorporate product information into the feature set, improving prediction performance by better representing the complete enzymatic reaction [6]. These tools are valuable for hypothesis generation, guiding experimental design, and prioritizing enzyme targets or variants for experimental characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function & Specification | Critical Notes for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Target | Biological catalyst of known sequence, purity, and specific activity [36]. | Determine stability under assay conditions. Use consistent lots; confirm absence of contaminating activities. |

| Native or Surrogate Substrate | Molecule transformed by the enzyme. Mimics natural substrate for assay feasibility [36]. | Chemical purity is essential. Ensure an adequate, sustainable supply for full project scope. |

| Assay Buffer System | Maintains optimal pH, ionic strength, and chemical environment for enzyme activity [36]. | Include necessary cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases, NADPH for reductases). Avoid components that inhibit or chelate. |

| Detection System Components | Enables quantification of reaction progress (e.g., NADH, chromogenic/fluorogenic probes, coupled enzymes) [39]. | Must be linear over the expected product range. Coupling enzymes must be in excess and not rate-limiting. |

| Reference Inhibitor | Known potent inhibitor of the target enzyme (e.g., EDTA for metalloproteases). | Serves as a positive control for assay validation and as a benchmark for screening campaigns. |

| Inactive Enzyme Mutant | Catalytically dead mutant purified identically to wild-type [36]. | Critical control for distinguishing specific enzymatic signal from non-specific background in complex systems. |