From Uncertainty to Insight: Navigating Non-Identifiable Parameters in Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

This article addresses the pervasive challenge of non-identifiable parameters in enzyme kinetics, a critical bottleneck for predictive modeling in biochemistry and drug development.

From Uncertainty to Insight: Navigating Non-Identifiable Parameters in Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

Abstract

This article addresses the pervasive challenge of non-identifiable parameters in enzyme kinetics, a critical bottleneck for predictive modeling in biochemistry and drug development. We explore the 'dark matter' of enzymology—kinetic data trapped in unstructured literature—and its contribution to parameter uncertainty [citation:1]. The scope progresses from foundational concepts and biological origins of non-identifiability to modern computational extraction and prediction methodologies like EnzyExtract and UniKP [citation:1][citation:2]. We provide practical guidance for troubleshooting experimental and analytical issues and establish a framework for validating parameters through structured datasets and comparative benchmarking. This integrated guide equips researchers and drug development professionals with strategies to enhance the reliability and applicability of kinetic parameters in biomedical research.

Unraveling the Core Challenge: What Makes Enzyme Kinetic Parameters Non-Identifiable?

In enzymology and systems biology research, a vast reservoir of untapped information exists within unstructured and unanalyzed kinetic datasets—this is the field's "dark data." Similar to the broader concept where organizations collect but fail to utilize information assets, enzymatic dark data comprises the unprocessed time-course measurements, incomplete reaction profiles, and uncharacterized parameter sets that accumulate in labs [1] [2]. This data often becomes dark due to non-identifiability, where multiple parameter combinations fit the experimental observations equally well, making results unreliable and obscuring true mechanistic understanding [3] [4]. This technical support center provides a framework for diagnosing, troubleshooting, and extracting value from these non-identifiable systems, turning obscurity into opportunity [2].

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My kinetic model fits the data well, but the returned parameter values change dramatically with each optimization run. What is happening? A: This is a classic symptom of practical non-identifiability [4]. Your model is "sloppy," meaning the data you have collected is insufficient to constrain all parameters uniquely. Different parameter combinations can produce nearly identical model outputs, especially in the presence of experimental noise. You need to perform an identifiability analysis to diagnose which parameters are non-identifiable and then follow a structured protocol to resolve it [3].

Q2: What is the difference between "structured" and "unstructured" dark data in enzymology?

A: Structured dark data resides in defined but unexplored formats, such as SQL databases of initial reaction velocities (V0) under varied conditions or organized but unanalyzed plate reader outputs. Unstructured dark data includes information not easily parsed by standard tools, like lab notebook text entries, non-standardized instrument log files, or unannotated time-series data from discontinued projects [1] [5]. Both types contribute to the "dark matter" of the field when their potential insights remain untapped.

Q3: How can I assess if my model is non-identifiable before investing in complex experiments? A: Implement a profile likelihood analysis or a principal component analysis (PCA) on the parameter covariance matrix. These techniques, part of a formal Identifiability Analysis (IA) module, will classify parameters as identifiable, structurally non-identifiable (due to model redundancy), or practically non-identifiable (due to poor-quality or insufficient data) [3] [4]. The table below summarizes key characteristics of enzymatic dark data that lead to these issues.

Table 1: Characteristics and Sources of Enzymatic Dark Data Leading to Non-Identifiability

| Data Characteristic | Common Source in Enzymology | Primary Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Unstructured Format | Handwritten lab notes, non-standardized instrument logs | Data cannot be integrated or analyzed computationally [2]. |

| High Noise-to-Signal | Low-concentration fluorescence assays, single-turnover experiments | Obscures true kinetic parameters, causing practical non-identifiability [4]. |

| Sparse Time-Courses | Stopped-flow experiments with limited time points, single-endpoint assays | Provides insufficient information to define dynamic model parameters uniquely [3]. |

| Siloed Datasets | Previous student's raw data, unpublished negative results | Critical contextual metadata is lost, rendering data unusable [1]. |

| Correlated Parameters | Linked rate constants in multi-step mechanisms (e.g., kcat and Kd) |

Creates structural non-identifiability; only parameter combinations can be determined [3]. |

Q4: My model is non-identifiable, but new experiments are costly. Can I still use it for predictions? A: Yes. A Bayesian approach with informed priors can allow for unique parameter estimation even with non-identifiable models [3]. Furthermore, research shows that models trained on limited data can still have predictive power for specific variables or perturbations. For example, a signaling cascade model trained only on the final output variable can accurately predict that variable's response to new stimuli, even while intermediate species remain unpredictable [4].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Km and Vmax estimates from replicate experiments.

- Diagnosis: Likely practical non-identifiability exacerbated by high measurement noise or an insufficient range of substrate concentrations [4].

- Solution:

- Visually inspect a Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot. Significant scatter or non-linearity at low substrate concentrations indicates data quality issues [6].

- Ensure your substrate concentration range brackets the suspected

Kmvalue (ideally from0.2Kmto5Km). - Increase the number of replicate measurements at limiting substrate concentrations to reduce the impact of noise.

- Switch to a more robust fitting algorithm (e.g., non-linear regression fitting the direct Michaelis-Menten equation instead of the linearized form).

Problem: Adding more data points does not improve parameter confidence intervals.

- Diagnosis: Possible structural non-identifiability. The model itself may have redundant parameters. For example, in a two-step reaction

E + S <-> ES -> E + P, only the combinationkcat/Kmmay be identifiable from initial velocity data alone. - Solution:

- Perform a structural identifiability analysis (e.g., using a tool like

STRIKE-GOLDD) on your model's equations [3]. - If structural non-identifiability is confirmed, re parameterize your model. Combine non-identifiable parameters into a composite, identifiable parameter (e.g., use

kcat/Kminstead of separatekcatandKdvalues). - Design an experiment to measure a new observable that breaks the symmetry (e.g., pre-steady-state burst kinetics to isolate the

kcatstep).

- Perform a structural identifiability analysis (e.g., using a tool like

Problem: Computational fitting algorithms fail to converge or get stuck in local minima.

- Diagnosis: The parameter estimation problem is highly non-linear and multimodal [3].

- Solution:

- Implement a global optimization strategy, such as a particle swarm or genetic algorithm, to explore the parameter space broadly before refinement.

- Use a sequential Bayesian method like the Constrained Square-Root Unscented Kalman Filter (CSUKF). This method handles noise well and can incorporate prior knowledge as constraints to guide the estimation [3].

- Start fits with multiple, widely spaced initial parameter guesses to check for consistency in the final solution.

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Unified Framework for Parameter Estimation with Non-Identifiable Systems

This protocol, based on a unified computational framework [3], is designed to obtain reliable parameter estimates even when faced with non-identifiability.

1. Model Formulation:

- Express your kinetic model as a set of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) representing the dynamics of species concentrations.

- Formulate the ODEs into a non-linear state-space model. The state vector (

x) contains the time-dependent species concentrations. The parameters (θ) to be estimated are treated as constant augmented states [3]. - Define the observation function (

H) that maps states to measurable outputs (e.g.,y = [ES] + [P]for a total product signal).

2. Identifiability Analysis (IA) Module:

- Perform a structural identifiability analysis using a symbolic tool to determine if the model structure permits unique parameters.

- Perform a practical identifiability analysis using your actual (noisy) dataset. Techniques like profile likelihood are recommended [3].

- Classify parameters as: (i) identifiable, (ii) structurally non-identifiable, or (iii) practically non-identifiable.

3. Resolution Attempt:

- For structurally non-identifiable parameters, seek to reparameterize the model or add new measurement types.

- For practically non-identifiable parameters, check if experimental redesign (e.g., different stimulus protocol, wider concentration range) can generate more informative data [4].

4. Constrained Estimation with Informed Priors:

- If non-identifiability cannot be fully resolved, use the Constrained Square-Root Unscented Kalman Filter (CSUKF) for estimation [3].

- Translate known biochemical constraints (e.g.,

km > 0,kcat < 10^6 s⁻¹) into formal bounds for the CSUKF. - Use literature values or related experimental results to formulate an "informed prior" probability distribution for the parameters. The CSUKF uses this prior to converge to a unique, biologically plausible solution from a non-identifiable starting point [3].

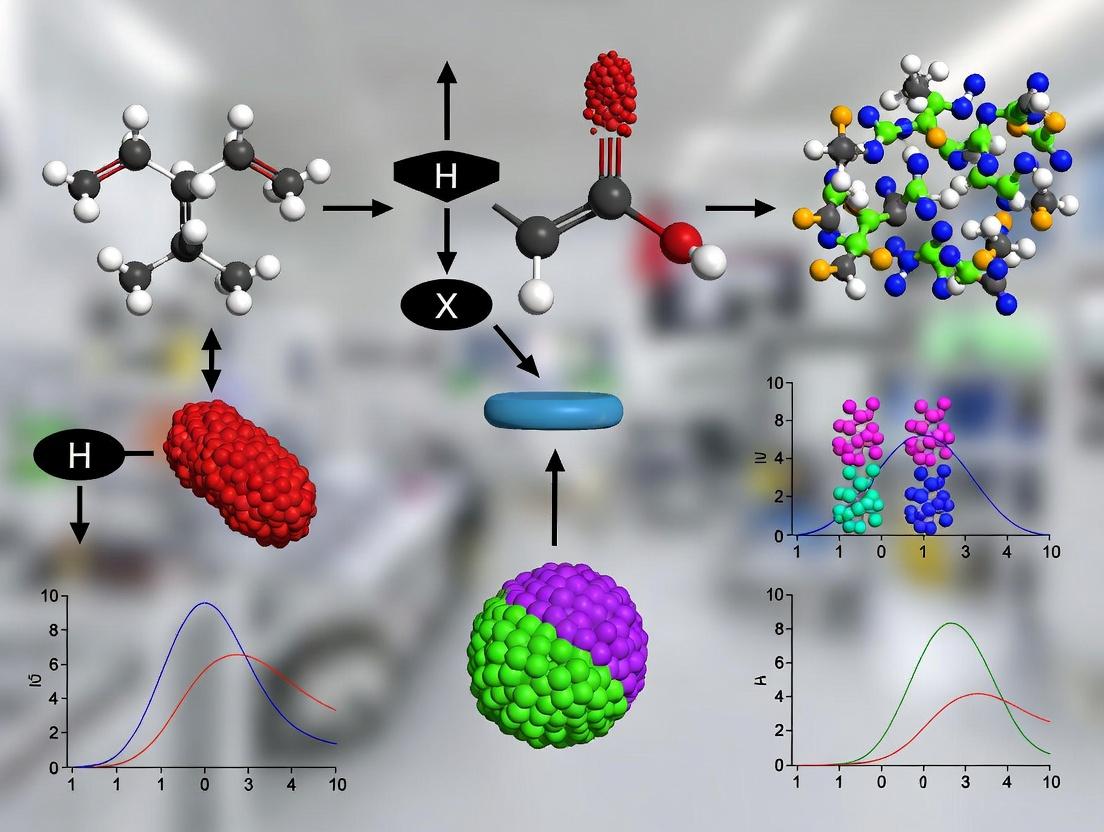

Diagram: Unified parameter estimation workflow for non-identifiable systems.

Protocol 2: Sequential Model Training for Predictive Power

This protocol, adapted from studies on predictive non-identifiable models [4], allows you to build predictive capability iteratively.

1. Initial Simple Experiment:

- Choose a single, reliable readout (e.g., final product concentration

[P]). - Apply a well-defined, time-varying stimulus

S(t)(e.g., substrate pulse, inhibitor wash-in). - Measure the trajectory of your chosen readout with replicates to estimate noise.

2. Train Model on Single Variable:

- Use a Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method to sample the "plausible parameter space" that fits the single-variable dataset [4].

- Assess prediction: Use the ensemble of plausible parameters to predict the same variable's trajectory under a different stimulation protocol. If successful, the model has predictive power despite non-identifiability.

3. Iterative Expansion:

- Design a second experiment to measure an additional variable (e.g., an intermediate complex

[ES]). - Retrain the model on the combined dataset (Variable 1 + Variable 2).

- The dimensionality of the plausible parameter space will reduce, increasing predictive power for both variables [4].

- Repeat until the model's predictions meet required confidence levels for all variables of interest.

Table 2: Example of Sequential Training on a Signaling Cascade Model [4]

| Training Dataset | Prediction Accuracy for K4 | Prediction Accuracy for K2 | Effective Parameter Space Dimensionality | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K4 only | High (for new stimuli) | Very Low | Reduced by 1 dimension | Model is useful for predicting final output only. |

| K4 + K2 | High | High | Reduced by 2 dimensions | Predictive power expanded to include an intermediate node. |

| K4 + K2 + K1 + K3 | High | High | Reduced by 4 dimensions | Model is "well-trained"; most stiff directions identified. |

Diagram: Sequential training workflow to build model predictive power.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational & Experimental Reagents for Kinetic Dark Data Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in This Context |

|---|---|---|

| Constrained Square-Root Unscented Kalman Filter (CSUKF) | A stable, nonlinear Bayesian filtering algorithm for state and parameter estimation. | Core estimator in the unified framework; uniquely estimates parameters with informed priors under non-identifiability [3]. |

| Profile Likelihood Analysis | A practical identifiability method that profiles the likelihood function for each parameter. | Diagnoses practical non-identifiability and assesses the certainty of parameter estimates [3] [4]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampler | A computational algorithm for sampling from a probability distribution. | Used in sequential training to explore the "plausible parameter space" consistent with experimental data [4]. |

| Optogenetic Stimulation System | Allows precise, complex temporal control of biological activation. | Enables the application of sophisticated stimulation protocols S(t) critical for training and testing model predictions [4]. |

| Lineweaver-Burk Plot | A linear transformation of the Michaelis-Menten equation (1/v vs. 1/[S]). |

A classic diagnostic tool for identifying data quality issues, inhibition type, and initial parameter guesses [6]. |

| Data Governance Policy | A framework for managing data availability, usability, integrity, and security. | Prevents the creation of new dark data by standardizing metadata, formats, and archiving practices for kinetic datasets [1]. |

A central thesis in modern enzyme kinetics and drug development is the systematic handling of non-identifiable parameters—those key values that cannot be uniquely determined from experimental data due to inherent biological complexity and methodological limitations. The primary sources of this challenge are the significant gaps between controlled in vitro assays and complex in vivo systems, and the statistical issue of multicollinearity, where correlated predictor variables obscure the individual effect of each parameter during estimation [7].

This technical support center is designed to help researchers navigate these obstacles. It provides targeted troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols focused on bridging the in vitro-in vivo gap and achieving robust parameter estimation, which is critical for building predictive metabolic models and advancing therapeutic discovery [7] [8].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my estimated in vivo kinetic constants (e.g., kcat, KM) differ drastically from published in vitro database values?

- A: This is a fundamental manifestation of the in vitro-in vivo gap. In vitro measurements are performed under optimized, isolated conditions, while in vivo constants are influenced by cellular context, including macromolecular crowding, post-translational modifications, and competition for substrates. The Model Balancing approach is designed to reconcile these by integrating omics data (fluxes, metabolite concentrations) to infer context-specific constants [7].

Q2: My parameter estimation algorithm fails to converge or returns widely varying values with each run. What is the cause?

- A: This is a classic symptom of a non-identifiable parameter set or a poorly conditioned estimation problem, often exacerbated by multicollinearity. When model parameters are highly correlated, multiple combinations can fit the data equally well, leading to numerical instability. Solutions include: 1) Incorporating thermodynamic constraints (e.g., Haldane relationships) to reduce the feasible parameter space [7], 2) Using ensemble modeling approaches to characterize the distribution of plausible parameters [7], and 3) Applying regularization techniques in your cost function to penalize unrealistic values.

Q3: How can I determine if my in vitro angiogenesis assay results will translate to an in vivo model?

- A: Translation failure often stems from assay simplification. In vitro assays (e.g., endothelial cell tube formation) isolate specific behaviors but lack systemic factors. To mitigate this gap: 1) Choose relevant cell types (e.g., organ-specific microvascular endothelial cells over generic HUVECs) [8], 2) Employ co-culture systems that include supportive cells like pericytes [8], and 3) Use a tiered experimental strategy where key findings from in vitro assays are sequentially validated in increasingly complex ex vivo and in vivo models [8].

Q4: What does "model balancing" mean, and how does it differ from standard parameter fitting?

- A: Model Balancing is a specific method for estimating a consistent and thermodynamically feasible set of kinetic constants, metabolite concentrations, and enzyme concentrations simultaneously, given a known metabolic flux distribution [7]. Unlike fitting parameters for individual reactions in isolation, it solves a network-wide convex optimality problem that respects the physical interdependence of all parameters, thereby avoiding violations of thermodynamic laws that can occur with piecemeal fitting [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Pitfalls

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor reproducibility in enzyme activity assays. | Unstable enzyme preparation, inappropriate buffer conditions, or outdated substrate stock. | Aliquot and store enzymes at recommended temperatures; prepare substrate solutions fresh; include positive controls with a known substrate in every run. |

| High residual error in Lineweaver-Burk plots for inhibition studies. | Inappropriate inhibitor concentration range or failure to reach steady-state kinetics. | Ensure inhibitor concentration spans values above and below expected KI; verify that pre-incubation time of enzyme with inhibitor is sufficient [6]. |

| Inability to distinguish between competitive and non-competitive inhibition patterns. | Noisy data or too narrow a substrate concentration range. | Widen the substrate concentration tested (from 0.2-5 x KM); use nonlinear regression in addition to linear plots for analysis [6]. |

| Discrepancy between computed kcat from in vitro data and apparent in vivo catalytic rate. | Cellular conditions limit enzyme saturation or activity. | Use kinetic profiling: compute apparent kcat (v/[E]) across multiple metabolic states; the maximum observed value is a lower-bound estimate for the true in vivo kcat [7]. |

| Failed validation of a pro-angiogenic compound in vivo after positive in vitro results. | The in vitro assay lacked key physiological components (flow, immune cells, correct ECM). | Prior to in vivo testing, validate hits in a more complex ex vivo model (e.g., aortic ring assay) that preserves tissue microenvironment [8]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Model Balancing for EstimatingIn VivoKinetic Constants

Objective: To estimate a thermodynamically consistent set of in vivo kinetic parameters from omics data [7].

Principles: The method solves for unknown parameters by minimizing the discrepancy between modeled and observed data while adhering to thermodynamic constraints and predefined flux distributions [7].

Procedure:

- Input Data Preparation:

- Gather the metabolic network stoichiometry (S).

- Obtain measured or calculated flux distributions (v) for the metabolic states of interest.

- Compile available data on enzyme concentrations ([E]), metabolite concentrations ([c]), and any known in vitro kinetic constants (KM, kcat).

- Define appropriate priors (expected distributions) for unknown parameters.

- Problem Formulation:

- Define a posterior probability function that includes terms for: (i) deviation of model predictions from data, (ii) deviation of parameters from their priors, and (iii) a penalty for thermodynamically infeasible loops (Wegscheider conditions).

- For convex optimization, a simplified version that omits the penalty term for low enzyme concentrations can be used to guarantee a unique solution [7].

- Convex Optimization:

- Use a convex optimization solver to find the parameter set that minimizes the posterior function. This yields point estimates for all unknown kinetic constants, ensuring they are consistent with the flux data and each other.

- Validation & Analysis:

- Check the consistency of the estimated parameters (e.g., all kcat, KM > 0).

- Perform a sensitivity analysis to see which parameters are well-constrained by the data and which remain non-identifiable.

Applications: Completing kinetic models, reconciling heterogeneous omics datasets, predicting plausible metabolic states [7].

Protocol: Distinguishing Reversible Inhibition Mechanisms

Objective: To determine the type (competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive) and affinity (KI) of a reversible enzyme inhibitor [6].

Principles: Different inhibition mechanisms produce characteristic changes in the apparent Michaelis-Menten parameters Vmax and KM.

Procedure:

- Experimental Setup:

- Conduct a series of initial velocity (V0) measurements.

- Vary substrate concentration [S] across a range (typically 0.2-5 x KM) at several fixed concentrations of inhibitor [I] (including [I]=0).

- Maintain constant enzyme concentration and conditions.

- Data Analysis:

- For each [I], plot 1/V0 vs. 1/[S] (Lineweaver-Burk plot).

- Fit lines to determine the apparent Vmax and KM for each inhibitor condition.

- Mechanism Diagnosis:

- Competitive Inhibition: Apparent KM increases with [I]; apparent Vmax is unchanged. Lines intersect on the y-axis [6].

- Non-competitive Inhibition: Apparent Vmax decreases with [I]; apparent KM is unchanged. Lines intersect on the x-axis.

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: Both apparent Vmax and apparent KM decrease. Parallel lines are produced.

- Calculation of KI:

- For competitive inhibition: KI = [I] / ((KM(app)/KM) - 1), where KM(app) is the apparent KM in the presence of inhibitor [6].

- Use analogous formulas for other mechanisms based on changes in Vmax or both parameters.

Protocol: Tiered Angiogenesis Assessment fromIn VitrotoEx Vivo

Objective: To improve the translational predictive value of angiogenesis drug discovery by employing a cascade of assays of increasing physiological complexity [8].

Principles: Simple in vitro assays are used for high-throughput screening, followed by validation in more integrated ex vivo tissue models that preserve key aspects of the microenvironment [8].

Procedure:

- Primary In Vitro Screen (Endothelial Cell Proliferation/Migration):

- Use relevant human microvascular endothelial cells (e.g., dermal, cardiac).

- Serum-starve cells to induce quiescence. Treat with test compounds and measure proliferation (via BrdU or MTT) or migration (via Boyden chamber) relative to controls [8].

- Secondary In Vitro Assay (Tube Formation):

- Plate endothelial cells on a basement membrane matrix (e.g., Matrigel).

- Treat with hits from the primary screen. Quantify network formation after 4-18 hours by measuring total tube length, number of branches, or mesh area using image analysis software.

- Tertiary Ex Vivo Validation (Aortic Ring Assay):

- Isbrate the aorta from a rodent (e.g., mouse), cut into ~1 mm rings, and embed in a collagen gel.

- Culture rings with test compounds. Over 5-7 days, microvessels will sprout from the ring.

- Quantify sprouting area, number, and length. This model includes intact endothelial cells, pericytes, and fibroblasts, providing a robust pre-in vivo checkpoint [8].

Diagrams and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Organ-Specific Microvascular Endothelial Cells | Primary cells that better reflect the phenotype of the target vascular bed (e.g., brain, dermis) than generic HUVECs, improving translational relevance [8]. | Early passage (P3-P6) use is critical to maintain organ-specific markers and avoid phenotypic drift [8]. |

| Reconstituted Basement Membrane Matrix (e.g., Matrigel) | A gelatinous protein mixture simulating the extracellular matrix; used for endothelial cell tube formation assays to study differentiation and morphogenesis [8]. | Lot-to-lot variability can affect results; always include internal controls. Keep on ice during handling. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase (for PCR) | Enzyme for amplifying DNA segments. Its consistent kinetics at high temperatures are vital for reproducible quantitative PCR, a common readout in molecular biology. | Specific buffer composition and Mg2+ concentration are non-identifiable parameters that must be optimized for each primer-template system. |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to cell lysis buffers to preserve the in vivo post-translational modification state of proteins (e.g., phosphorylation) during in vitro analysis. | Prevents artefactual changes in enzyme activity and protein-protein interactions after cell disruption. |

| Isotopically Labeled Substrates (13C, 15N) | Enable tracking of metabolic flux in living systems via techniques like Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA), providing the crucial flux (v) data needed for model balancing [7]. | Choice of labelling pattern (e.g., [U-13C]-glucose) depends on the metabolic network being probed. |

| Convex Optimization Software (e.g., CVX, COBRA Toolbox) | Computational tools essential for solving the model balancing problem and finding unique, consistent parameter sets from large, heterogeneous data [7]. | Requires correct formulation of the optimization problem (objective function + constraints) to yield biologically meaningful solutions. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

This center provides targeted solutions for researchers encountering unreliable or inconsistent kinetic parameters in enzyme kinetics and systems biology modeling.

Q1: My computational model of a metabolic pathway produces biologically implausible outputs. I suspect the enzyme kinetic parameters I sourced from literature are unreliable. How do I systematically diagnose this "fitness-for-purpose" problem? [9]

A1: A systematic diagnostic workflow is essential. Follow this step-by-step guide to identify the root cause.

- Step 1: Verify Parameter Source & Identity. Confirm you used the correct Enzyme Commission (EC) number for your specific enzyme, organism, and cellular compartment [9]. Cross-check the parameter's original publication for details often lost in databases.

- Step 2: Audit Assay Conditions. Compare the experimental conditions (pH, temperature, buffer composition, presence of activators/inhibitors) under which the parameter was derived to your model's physiological context. A parameter measured at pH 8.6 is likely unfit for a model of cytosolic conditions at pH 7.2 [9].

- Step 3: Check for Initial-Rate Validation. Ensure the cited study explicitly states that parameters were derived from initial-rate measurements. Parameters from endpoint assays can be distorted by product inhibition or enzyme instability [9].

- Step 4: Evaluate Parameter Identifiability. Your model may be non-identifiable, meaning different parameter combinations yield identical model outputs, making unique estimation impossible [10]. Use profiling or subset selection to test this.

- Step 5: Conduct Sensitivity Analysis. Perform a local or global sensitivity analysis on your model. This quantifies how much each parameter influences the model output. Parameters with high sensitivity indices that are also of questionable reliability are prime candidates for the error source.

Q2: I have found multiple reported values for my enzyme's Km (Michaelis constant) that vary by an order of magnitude. Which one should I use, and how can I assess their quality? [9]

A2: Do not simply average the values. You must perform a critical fitness-for-purpose assessment based on the following criteria:

Table 1: Criteria for Assessing Fitness-for-Purpose of Reported Kinetic Parameters

| Assessment Criterion | Key Questions to Ask | Action if Criterion Fails |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance [9] | Were the assay conditions (pH, temp, buffer ions) close to the enzyme's natural environment? Was a physiological substrate used? | Prioritize values from studies using conditions closest to your modeled system. |

| Methodological Rigor [9] | Were initial rates properly established? Was the enzyme well-characterized and stable? Was the fitting method appropriate? | Scrutinize the methods section. Values from studies with unclear methods should be downgraded. |

| Parameter Identifiability [10] | Could the reported value be part of a non-identifiable parameter set in the original study's own analysis? | If the original data or error estimates are available, check for large confidence intervals, suggesting practical non-identifiability. |

| Source Reputation | Is the data from a peer-reviewed source adhering to standards like STRENDA (Standards for Reporting ENzymology Data) [9]? Is it curated in a reputable database like BRENDA? | Prefer values from STRENDA-compliant studies and well-curated database entries with clear provenance. |

Q3: My parameter estimation for a complex enzyme model yields very large confidence intervals, or the optimization algorithm fails to converge. What does this mean, and what can I do? [10]

A3: This typically indicates a parameter identifiability problem. Your model may be:

- Structurally non-identifiable: The model structure makes it impossible to uniquely estimate parameters, regardless of data quality (e.g., two parameters always appear as a product).

- Practically non-identifiable: The available data is insufficiently informative to pinpoint the parameter values, leading to flat likelihood profiles and large confidence intervals [10].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Simplify the Model: Use a model reduction technique. Fix poorly identifiable parameters to literature values (if trustworthy) or combine related parameters into a single, identifiable composite parameter [10].

- Reparameterize: Reformulate your model to use identifiable parameter combinations (e.g., use

Vmax/Kminstead of separateVmaxandKmif they are correlated). - Design a Better Experiment: If possible, design new experiments that provide information specifically targeting the unidentifiable parameters (e.g., measuring multiple reaction progress curves under different conditions).

Q4: How can I ensure the kinetic data I generate and report will be "fit for purpose" for other researchers in the future? [9]

A4: Adhere to community standards and report with maximal transparency.

- Follow the STRENDA Guidelines: Implement the STandards for Reporting ENzymology DAta in your work and submit to the STRENDA database [9]. This ensures all necessary metadata (assay conditions, enzyme source, analysis methods) is preserved.

- Report Full Context: Always report the exact enzyme source (organism, tissue, recombinant form), purification steps, full assay composition (buffer, salts, cofactors), temperature, pH, and the raw data or a clear visualization thereof.

- Quantify Uncertainty: Provide confidence intervals or standard errors for all fitted parameters. Report the results of residual analysis to demonstrate the goodness of fit.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol 1: Validating the Linear Range for Initial-Rate Measurements

Purpose: To establish the time window during which the reaction velocity is constant, ensuring subsequent kinetic analysis adheres to the fundamental assumption of the Michaelis-Menten equation [9].

Methodology:

- Prepare a reaction mixture with substrate concentration at approximately the expected Km value.

- Initiate the reaction and monitor product formation or substrate depletion continuously (e.g., via spectrophotometry) with high time resolution.

- Plot the progress curve (product concentration vs. time).

- Fit a linear regression to successively shorter segments of the initial part of the progress curve. The maximum time period for which the regression coefficient (R²) remains >0.995 defines the valid initial-rate period for that substrate concentration.

- Repeat at high and low substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.2Km and 5Km). The shortest initial-rate period identified across concentrations should be used for all subsequent assays.

Protocol 2: Assessing Parameter Practical Identifiability via Profile Likelihood

Purpose: To diagnose which parameters in your model are poorly constrained by your specific dataset [10].

Methodology:

- After fitting your model to the data, obtain the maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) for each parameter.

- For a target parameter θ, fix its value at a series of points around the MLE (e.g., ± 2 orders of magnitude).

- At each fixed value of θ, re-optimize the model by letting all other parameters vary freely to find the best possible fit.

- Plot the optimized likelihood (or sum of squared residuals) against the fixed values of θ. This is the profile likelihood.

- Interpretation: A flat profile indicates practical non-identifiability—the data does not contain information to estimate θ. A sharply defined minimum indicates good identifiability. Confidence intervals can be derived from the points where the profile crosses a threshold above the minimum.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Resource Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Reliable Enzyme Kinetics & Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function & Relevance to Fitness-for-Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| STRENDA Database & Guidelines [9] | Reporting Standard | Provides a checklist and portal to report enzymology data with all necessary metadata, ensuring future reusability and assessment. |

| BRENDA Enzyme Database [9] | Data Repository | The most comprehensive enzyme information system. Use to find reported parameters but critically cross-check original sources for context. |

| SABIO-RK [9] | Data Repository | A curated database of biochemical reaction kinetics with a focus on systems biology models. Often includes cellular context. |

| IUBMB ExplorEnz [9] | Nomenclature Reference | The definitive source for EC numbers and enzyme nomenclature. Critical for correctly identifying the target enzyme. |

| Model Reduction Code (GitHub) [10] | Software Tool | Open-source Julia implementation for diagnosing and addressing non-identifiable models via reparameterization [10]. |

| Physiological Assay Buffers (e.g., KPI, HEPES, tailored "intracellular" mixes) [9] | Research Reagent | Using buffers that mimic the target physiological environment (ionic strength, activator ions like K⁺ or Mg²⁺) yields more relevant parameters. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting AI-Driven Enzyme Kinetics Research

This support center addresses common computational and experimental challenges faced when integrating artificial intelligence (AI) with enzyme kinetics and systems biology. The guidance is framed within the critical context of handling non-identifiable parameters—where different combinations of model parameters fit experimental data equally well, leading to unreliable biological conclusions [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. My AI model for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat, Km) performs well on test data but fails in real-world enzyme discovery. What is the primary cause? The most likely cause is data leakage and overfitting due to non-rigorous dataset splitting. If proteins in your training and test sets share high sequence similarity, the model may memorize patterns instead of learning generalizable principles [12]. A standard random split often leads to this optimistic bias.

- Solution: Implement cluster-based splitting. Use tools like CD-HIT to cluster enzyme sequences by similarity (e.g., 40% identity). Ensure all sequences from one cluster reside exclusively in either the training or test set. This "unbiased" partitioning rigorously tests the model's ability to generalize to novel enzyme families [12].

2. How can I assess if the kinetic parameters estimated from my experimental data are reliable and not misleading due to non-identifiability? Non-identifiability is a fundamental pitfall in kinetic modeling, where vastly different parameter sets produce identical fits to data [11].

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Perform a profile likelihood or Bayesian analysis. Instead of accepting a single "best-fit" parameter set, use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to explore the full parameter space [11].

- Analyze the resulting posterior distributions. Well-identified parameters will have narrow, peaked distributions. Non-identifiable parameters will show broad, flat distributions or strong correlations with other parameters, indicating that the data cannot uniquely determine their values [11] [13].

- Action: If parameters are non-identifiable, simplify your model or design new experiments (e.g., measuring additional observables) to provide stronger constraints.

3. What is the most effective way to leverage historical literature data to improve my predictive AI models? Most published enzyme kinetic data remains unstructured "dark matter" in PDFs, inaccessible for training [14].

- Solution: Utilize emerging Large Language Model (LLM)-powered extraction tools. Pipelines like EnzyExtract can process hundreds of thousands of publications to automatically extract and structure kinetic parameters, substrate identities, and experimental conditions [14]. Retraining models (e.g., DLKcat, UniKP) on such expanded, high-quality datasets has been shown to significantly boost predictive performance (e.g., reduced RMSE, increased R²) [14].

4. Can I trust AI-predicted enzyme functions for proteins with no known homologs? Current machine learning models, including advanced protein language models, are primarily powerful at interpolating within known function space. They largely fail at extrapolating to predict genuinely novel enzymatic functions not represented in their training data [15]. Models can also make "hallucinatory" logic errors that a human expert would avoid [15].

- Recommendation: Treat AI predictions for unknown proteins (the "unknome") as high-quality hypotheses. Always prioritize predictions supported by additional evidence (e.g., genomic context, structural features of the active site) and plan for experimental validation [15].

5. How do regulatory considerations for AI in drug development impact my research on predictive models? Regulatory frameworks are evolving and differ by region. The EMA (Europe) employs a structured, risk-tiered approach, requiring frozen AI models and pre-specified validation for clinical trials [16]. The FDA (U.S.) currently uses a more flexible, case-by-case model [16]. This divergence can create uncertainty.

- Best Practice: For research aimed at eventual regulatory submission, engage early with agencies via scientific advice procedures. Adopt FAIR data principles and rigorous model documentation practices, detailing training data, performance limits, and uncertainty measures to meet emerging standards [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent or conflicting kinetic parameters from different data sources hinder model building. Root Cause: Historical data from various assays and conditions often disagree. A simple "bottom-up" assembly of parameters from diverse sources leads to non-functional, inconsistent models [13]. Resolution Workflow:

- Gather & Consolidate: Collect all available in vitro and in vivo data for the target enzyme(s) [13].

- Systematic Fitting: Use a robust parameter estimation tool (e.g., MASSef) that can reconcile inconsistencies by fitting a detailed mass-action model simultaneously to all available data sets [13].

- Quantify Uncertainty: The tool should employ randomized initialization and parameter sampling to provide confidence intervals for every estimated rate constant, highlighting which parameters are well-constrained [13].

- Validate with Physiology: The final parameterized model must be validated against relevant in vivo physiological behavior, such as metabolic flux data [13] [17].

Issue: My genome-scale metabolic model with enzyme kinetics is too complex for traditional sensitivity analysis. Root Cause: Constraint-based models (like ecFBA) are formulated as optimization problems, making classic Metabolic Control Analysis (MCA) difficult to apply directly [17]. Resolution Method:

- Apply differentiable constraint-based modeling. This advanced technique uses implicit differentiation of the optimization problem to compute exact, mathematically precise sensitivities of model outputs (e.g., growth rate, fluxes) to changes in kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat values) [17].

- This allows you to efficiently perform genome-wide parameter estimation (e.g., refining kcat estimates) and identify key rate-limiting enzymes with quantified control coefficients, moving beyond heuristic finite-difference approximations [17].

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Generalizable AI Model for Kinetic Parameter Prediction This protocol is based on frameworks like UniKP and CataPro [18] [12].

- Data Curation: Collect enzyme sequences (UniProt IDs) and substrate structures (SMILES) linked to kinetic values (kcat, Km) from BRENDA/SABIO-RK or via EnzyExtract [12] [14].

- Unbiased Dataset Creation: Cluster enzyme sequences at 40% identity using CD-HIT. Perform cluster-wise splitting (e.g., 9:1) to create training and test sets, ensuring no cluster is in both [12].

- Feature Representation:

- Model Training & Selection: Concatenate the feature vectors. Train and compare multiple algorithms (e.g., Extra Trees, Random Forest, neural networks). Ensemble methods like Extra Trees often perform best on this high-dimensional data [18].

- Validation: Evaluate on the held-out test clusters. Report R², RMSE, and Pearson correlation. For true generalization, test on enzymes catalyzing reactions not present in the training data [18] [12].

Protocol 2: Bayesian Workflow for Diagnosing Parameter Non-Identifiability This protocol addresses a core thesis challenge [11].

- Model Definition: Formulate your kinetic model (e.g., a system of ODEs for a multi-step enzyme mechanism).

- MCMC Sampling: Use software like PyMC or Stan to perform Bayesian inference. Define likelihood functions based on your experimental data and set broad, non-informative priors for parameters.

- Run Sampling: Generate a large number of samples from the posterior distribution of the parameters.

- Analyze Diagnostics:

- Trace Plots: Check for stable convergence of sampling chains.

- Posterior Distributions: Plot marginal distributions for each parameter. Broad, uniform-like distributions indicate non-identifiability.

- Pairwise Correlation Plots: Strong correlations between parameters (e.g., a linear relationship between Km and kcat) are a hallmark of practical non-identifiability [11].

- Reporting: Report the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate along with the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) interval for each parameter. Wide HPD intervals explicitly communicate estimation uncertainty to the audience.

The table below compares the performance of recent AI models for predicting enzyme kinetic parameters, highlighting the importance of unbiased evaluation.

| Model Name | Key Architecture | Predicted Parameters | Reported Performance (Test Set) | Critical Assessment Note | Primary Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniKP | ProtT5 + SMILES Transformer; Extra Trees regressor | kcat, Km, kcat/Km | R² = 0.68 (on DLKcat dataset) | Demonstrates value of advanced protein/substrate embeddings. | [18] |

| CataPro | ProtT5 + MolT5 + Fingerprints; Neural Network | kcat, Km, kcat/Km | Superior accuracy on unbiased cluster-split benchmark. | Emphasizes rigorous, generalizable evaluation to prevent overfitting. | [12] |

| Retrained Models with EnzyExtractDB | Various (DLKcat, MESI, TurNuP) | Primarily kcat | Improved RMSE/MAE after retraining. | Shows that expanding training data with literature mining directly enhances model accuracy. | [14] |

| Classical ML (E. coli focus) | Feature-based ML (biochemistry, structure) | kcat (in vivo) | Useful for organism-specific predictions. | Scope is limited; not a general enzyme discovery tool. | [18] |

Research Reagent Solutions (The Scientist's Toolkit)

| Item Name | Category | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProtT5-XL-UniRef50 | Software/Model | Pre-trained protein language model. Converts an amino acid sequence into a numerical embedding that captures evolutionary and structural information, serving as optimal input for downstream ML tasks [18] [12]. | Standard for state-of-the-art performance; requires computational resources for inference. |

| EnzyExtractDB / BRENDA | Database | Structured repositories of enzyme kinetic data. BRENDA is manually curated; EnzyExtractDB is AI-extracted from literature, vastly expanding available data points for training [14]. | Always check data provenance and confidence flags. Cross-reference sources when possible. |

| MASSef Package | Software/Tool | A computational workflow for robust kinetic parameter estimation. It reconciles inconsistent data and quantifies parameter uncertainty, crucial for building reliable models [13]. | Essential for moving beyond single-point parameter estimates and handling non-identifiability. |

| Cluster-Based Splitting Script | Code/Protocol | Ensures unbiased evaluation of predictive models by preventing data leakage between training and test sets based on sequence similarity [12]. | Critical for assessing true generalizability. Should be a standard step in any modeling pipeline. |

| Differentiable Modeling Library (e.g., JAX, PyTorch) | Software/Framework | Enables gradient-based sensitivity analysis and parameter estimation in complex constraint-based metabolic models [17]. | Requires reformulating models within an automatic differentiation framework. Powerful for systems biology. |

Visualizations

AI-Driven Enzyme Kinetics Prediction Workflow

Diagnosing Parameter Non-Identifiability in Kinetic Models

Bridging the Data Gap: Modern Methods for Extraction, Prediction, and Application

This technical support center is designed for researchers and drug development professionals working with non-identifiable parameters in enzyme kinetics. It provides targeted guidance for integrating AI-powered data extraction and computational modeling to overcome parameter identifiability challenges.

The following table categorizes frequent issues encountered when working with non-identifiable enzyme kinetic models and AI data-mining tools, along with their recommended solution pathways.

| Problem Category | Typical Symptoms | Primary Solution Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sourcing & Curation | Sparse, inconsistent, or unstructured kinetic data; missing sequence mappings. | Use EnzyExtract for automated literature mining and dataset expansion [19]. |

| Model Non-Identifiability | Widely varying parameter estimates from fitting; failure to converge; parameters lacking biochemical interpretation [4]. | Apply Bayesian inference for plausible parameter sets and assess predictive power [4] [20]. |

| Prediction & Generalization | Poor model performance on new enzymes or substrates; lack of confidence metrics for predictions. | Implement frameworks like CatPred with uncertainty quantification and use out-of-distribution testing [21]. |

| Workflow Integration | Disconnect between extracted data, model training, and experimental validation. | Establish iterative cycles of prediction, experiment, and model updating [4] [10]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Scarcity with Automated Literature Mining

Problem: The available structured data for enzyme kinetics (e.g., in BRENDA) is limited, leaving a vast "dark matter" of unpublished or unstructured data, which hinders training robust AI models [19].

Diagnosis Protocol:

- Audit Your Dataset: Quantify the number of unique Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers and substrate pairs in your dataset. Compare its scope to known databases (e.g., BRENDA covers >3,000 enzyme types) [21].

- Identify Gaps: Check for missing annotations, such as enzyme sequences (UniProt IDs) or substrate structures (SMILES strings), which are critical for model input [21].

- Run EnzyExtract Benchmark: Use the tool on a small set of known literature to verify extraction accuracy of

kcatandKmvalues against manual curation [19].

Resolution Protocol:

- Deploy EnzyExtract: Process your target literature corpus (PDF/XML) using the available pipeline to extract and structure kinetic entries [19].

- Data Harmonization: Map extracted enzyme names to UniProt IDs and substrate names to canonical SMILES from PubChem to create a model-ready dataset [21] [19].

- Validation and Integration: Merge high-confidence extracted data with existing databases. Retrain your predictive model (e.g.,

kcatpredictor) and evaluate performance improvement on a held-out test set [19].

Guide 2: Handling a Non-Identifiable or Sloppy Kinetic Model

Problem: Your model fitting yields a wide, flat likelihood region, meaning many different parameter combinations fit the data equally well (practical non-identifiability), making parameters uninterpretable [4] [20].

Diagnosis Protocol:

- Profile Likelihood Analysis: Fix a parameter of interest and optimize over all others. A flat profile indicates non-identifiability [20].

- Eigenvalue Analysis: Compute the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) for your model and data. Eigenvalues close to zero indicate sloppy directions in parameter space [20].

- Check Predictions: Confirm if the non-identifiable model can still generate accurate predictions for a measured variable under new conditions (e.g., a different stimulation protocol) [4].

Resolution Protocol - Bayesian Approach:

- Define Priors: Set broad, physiologically plausible prior distributions (e.g., log-normal) for all parameters [4].

- Sample the Posterior: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling (e.g., Metropolis-Hastings algorithm) to obtain the full set of plausible parameters consistent with your data, rather than a single optimal point [4] [20].

- Analyze Parameter Space: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the logarithms of the plausible parameters. A reduction in dimensionality (e.g., from 9 to 8 stiff directions) confirms the model has been constrained, even without full identifiability [4].

- Make Predictive Sets: Use the ensemble of plausible parameters to generate prediction bands for experimental outcomes. A model is useful if these bands are narrow for the predictions of interest [4].

Guide 3: Implementing an Iterative Model-Refinement Loop

Problem: You have an initial, poorly identifiable model and limited resources for new experiments. You need a strategic protocol to design experiments that most efficiently constrain the model.

Diagnosis Protocol:

- Determine Current Stiffness: From your Bayesian posterior, identify the parameter combinations (principal components) with the largest variances—these are the sloppiest, most uncertain directions [4].

- Model Variable Prediction: Test if your current model, trained on existing data (e.g., only final product concentration), can accurately predict other unmeasured variables (e.g., intermediate concentrations). Broad prediction bands indicate no knowledge [4].

Resolution Protocol - Sequential Training:

- Initial Training: Train the model on the most easily measurable variable (e.g.,

K4in a cascade). - Design Next Experiment: Simulate which additional variable measurement (e.g.,

K2) would most reduce the variance in the sloppiest parameter directions. - Iterate: Conduct the experiment, add the new data to the training set, and retrain the model. Each iteration reduces the dimensionality of the plausible parameter space and expands the model's predictive power [4].

- Use a Relaxed Model: If network wiring is uncertain, train a model with more potential interactions (e.g., multiple feedback loops). The posterior distribution will show negligible strength for non-existent interactions, correctly suggesting the true network structure [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is EnzyExtract and how does it specifically help with enzyme kinetics research?

A1: EnzyExtract is a Large Language Model (LLM)-powered pipeline that automatically extracts, verifies, and structures enzyme kinetic data (kcat, Km, assay conditions) from scientific literature PDFs and XML files [19]. It directly addresses data scarcity by unlocking the "dark matter" of enzymology, having curated over 218,000 kinetic entries, with nearly 90,000 being new compared to major databases [19]. This expanded, high-quality dataset is critical for training more accurate and generalizable predictive AI models for enzyme engineering.

Q2: What's the practical difference between a "non-identifiable" and a "sloppy" model? A2: These concepts are closely related. Non-identifiability means different parameter sets produce identical model outputs, making unique parameter estimation impossible [4] [20]. Sloppiness describes a model where predictions are highly sensitive to changes in some parameter combinations (stiff directions) but insensitive to others (sloppy directions) [4]. A model can be identifiable but still sloppy, with many parameters poorly constrained by data. The key insight is that a sloppy, non-identifiable model can still have predictive power for specific outputs, which can be leveraged [4].

Q3: Why should I use Bayesian inference instead of traditional fitting for my kinetic model? A3: Traditional maximum likelihood methods seek a single best-fit parameter set, which fails and becomes unstable with non-identifiable models [20]. Bayesian inference, through MCMC sampling, maps out the entire landscape of plausible parameters consistent with your data and prior knowledge [4] [20]. This allows you to:

- Quantify uncertainty in parameters and predictions.

- Make robust predictions using the ensemble of all plausible parameters.

- Strategically design experiments to reduce the uncertainty in the most sloppy directions.

Q4: How do AI predictors like CatPred handle uncertainty in their kinetic parameter forecasts? A4: Advanced frameworks like CatPred move beyond single-point predictions. They use probabilistic regression to estimate two types of uncertainty [21]:

- Aleatoric Uncertainty: Noise inherent in the experimental training data.

- Epistemic Uncertainty: Model uncertainty due to a lack of similar training examples. They provide predictions as distributions (e.g., mean and variance), where a lower predicted variance often correlates with higher accuracy. This tells a researcher how much to "trust" a prediction for a novel enzyme-substrate pair [21].

Q5: My model is structurally correct but non-identifiable with my data. Should I simplify it? A5: Premature simplification can be detrimental. Composite parameters in a reduced model may lose biochemical meaning [4]. Instead, consider these steps:

- Accept Non-Identifiability: Use Bayesian methods to work with the full model and its plausible parameter sets [20].

- Assess Predictive Power: Check if the non-identifiable model can still predict key outcomes of interest [4].

- Iterative Data Collection: Use the model to design a minimal set of new experiments (e.g., measuring an additional variable) that will most effectively constrain it [4].

- Data-Informed Reduction: Only after step 3, use techniques like likelihood reparameterization to reduce the model in a way informed by the available data, preserving predictive accuracy [10].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for the AI-Enhanced Kinetics Pipeline

| Item | Function & Relevance to Non-Identifiable Parameters |

|---|---|

| EnzyExtractDB | A database created by the EnzyExtract LLM pipeline containing >218,000 structured kinetic entries [19]. Function: Provides the large-scale, diverse data needed to train robust AI predictors that can generalize to novel enzymes, helping to constrain model parameters. |

| CatPred Framework | A deep learning framework for predicting kcat, Km, and Ki [21]. Function: Generates initial, approximate kinetic parameters with uncertainty quantification. These estimates serve as valuable priors or constraints for fitting mechanistic models, reducing the sloppy parameter space. |

| Bayesian Inference Software (e.g., Pumas) | Software tools implementing MCMC sampling for parameter estimation [20]. Function: The primary method for fitting non-identifiable models. It outputs ensembles of plausible parameters, enabling uncertainty analysis and prediction without requiring a single "true" parameter set. |

| Optogenetic Stimulation Protocols | Techniques for applying precise, complex temporal signals to biological systems [4]. Function: Enables the design of informative experiments (e.g., oscillatory inputs) that can excite a system's dynamics to better reveal and constrain hidden parameters in a signaling cascade model [4]. |

| Profile Likelihood / FIM Analysis Code | Computational scripts to calculate profile likelihoods or the Fisher Information Matrix [20]. Function: Diagnostic tools to formally detect and visualize non-identifiable and sloppy parameter directions in a model before proceeding to Bayesian fitting or experimental design. |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: EnzyExtract LLM Workflow for Kinetic Data Mining

This diagram illustrates the automated pipeline for extracting and structuring enzyme kinetic data from scientific literature, creating a foundational dataset for AI model training.

Diagram 2: Iterative Bayesian Workflow for Non-Identifiable Models

This diagram outlines the sequential process of using Bayesian inference and strategic experimentation to build predictive power from a non-identifiable enzyme kinetic model.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center addresses common challenges researchers face when using unified prediction frameworks like UniKP and CatPred for enzyme kinetic parameters. The guidance is framed within the thesis context of handling non-identifiable parameters in enzyme kinetics research, where computational prediction serves as a critical tool for generating initial estimates and constraining complex models [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between UniKP and earlier prediction tools like DLKcat, and why should I use a unified framework? A1: Earlier tools often predicted single parameters (e.g., only kcat) and struggled with accurately deriving catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) from separate predictions [23]. UniKP introduces a unified framework that concurrently learns from protein sequences and substrate structures to predict kcat, Km, and kcat/Km with higher accuracy. Its key advantage is a 20% improvement in R² for kcat prediction compared to DLKcat and a demonstrated ability to identify high-activity enzyme mutants in directed evolution projects [23]. For research dealing with non-identifiable parameters, a unified model providing internally consistent predictions for all three parameters is essential for building reliable kinetic models.

Q2: How do I format my enzyme and substrate data as input for UniKP? A2: UniKP requires two primary inputs:

- Enzyme: The protein amino acid sequence as a standard string (e.g., "MLELLPTAV...").

- Substrate: The substrate structure in SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System) notation [23]. The framework internally processes the enzyme sequence with the ProtT5-XL-UniRef50 language model and the SMILES string with a pretrained SMILES transformer to create numerical feature vectors [23].

Q3: Can UniKP account for the effect of environmental conditions like pH and temperature on kinetics? A3: Yes, but through a specialized variant. The standard UniKP model predicts parameters under "optimal" or specified assay conditions. For explicit environmental factoring, the developers created EF-UniKP, a two-layer framework that incorporates pH and temperature data to provide robust kcat predictions under varying conditions [23]. This is particularly valuable for industrial applications where enzymes operate in non-standard environments.

Q4: My research involves enzymes with very high kcat values. Are predictions reliable in the high-value range? A4: Imbalanced datasets with scarce high-value samples are a known challenge. UniKP systematically addressed this by exploring four re-weighting methods during training, which successfully reduced prediction error for high-value kcat tasks [23]. You should consult the model documentation to see if a re-weighted version is available for your use case.

Q5: What does "non-identifiable parameters" mean in enzyme kinetics, and how can CatPred help? A5: In kinetic modeling, parameters are non-identifiable if multiple different parameter sets can fit the experimental data equally well, making unique determination impossible [22]. This often arises from insufficient or noisy data. Frameworks like CatPred help by providing accurate, sequence-based prior estimates for kcat, Km, and Ki (inhibition constant). These computationally predicted values can constrain the parameter space during model fitting, guiding solutions toward biologically realistic values and improving identifiability [22].

Q6: How reliable are predictions for an enzyme sequence that is very different from those in the training database? A6: This is known as a "distribution-out" challenge. Both UniKP and CatPred leverage pretrained protein language models (pLMs) that learn general evolutionary and biophysical patterns from millions of sequences. CatPred reports that its pLM features significantly enhance performance on such out-of-distribution samples [22]. For UniKP, the use of ProtT5 contributes to its strong performance on stringent tests where either the enzyme or substrate was absent from training [23].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Scenario | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor prediction accuracy for your specific enzyme family. | 1. Underrepresentation of your enzyme class in the model's training data.2. Incorrect or non-canonical SMILES string for the substrate. | 1. Check the coverage statistics of the model's training set (e.g., CatPred-DB covers all EC classes [22]).2. Validate and canonicalize your substrate SMILES string using a chemical toolkit (e.g., RDKit). |

| Inconsistent predictions between kcat, Km, and kcat/Km. | Using predictions from different, non-unified models that were not trained jointly. | Use a unified framework like UniKP that predicts all parameters jointly, ensuring internal consistency [23]. |

| Uncertainty in how to apply predictions to your kinetic model. | Lack of clarity on the prediction context (e.g., assay conditions, organism). | 1. Note the experimental context (pH, temp) of the predicted value. Use EF-UniKP for environmental specificity [23].2. Use the prediction as an informative prior or starting point for fitting your experimental data, especially when parameters are non-identifiable [22]. |

| High-value predictions seem unreliable. | Model bias towards more common, lower-value data points. | Seek out or retrain a model that employs re-weighting techniques to balance the loss function, giving more weight to rare, high-value examples during training [23]. |

| Need a measure of prediction confidence. | Many models output only a point estimate without uncertainty. | Use a framework like CatPred, which provides a probability distribution for each prediction (mean and variance) and quantifies uncertainty through an ensemble of models [22]. |

The following table summarizes the performance and key features of the discussed unified frameworks, highlighting their application in addressing kinetic parameter challenges.

Table 1: Comparison of Unified Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Prediction Frameworks

| Framework | Core Innovation | Reported Performance (R²/Improvement) | Handles Environmental Factors? | Uncertainty Quantification? | Primary Application Shown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniKP [23] | Unified pretrained language model (ProtT5 & SMILES) with an Extra Trees regressor. | kcat prediction R²=0.68 (20% improvement over DLKcat). PCC=0.85 on test set. | Yes, via the separate EF-UniKP two-layer model. | Not explicitly stated. | Enzyme discovery & directed evolution of tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL). |

| CatPred [22] | Integrates sequence, pLM, and 3D structure features with D-MPNN for substrates; probabilistic output. | Competitive performance with existing methods. Enhanced out-of-distribution performance via pLM features. | Not explicitly stated. | Yes. Provides per-prediction variance and model ensemble uncertainty. | Generating priors for kinetic modeling, pathway design, and metabolic engineering. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: In Silico Enzyme Screening Using UniKP

This protocol outlines how to use a framework like UniKP to prioritize enzymes for experimental characterization.

- Define Target Reaction: Identify the substrate and desired catalytic transformation.

- Curate Input Sequences: Compile a list of candidate enzyme amino acid sequences from databases (e.g., UniProt).

- Prepare Substrate Structure: Obtain or draw the 2D structure of the substrate and convert it to a canonical SMILES string.

- Run Predictions: Input the (Sequence, SMILES) pairs into the UniKP model to obtain predicted kcat, Km, and kcat/Km for each candidate.

- Rank and Analyze: Rank enzymes based on predicted catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km). The unified prediction ensures consistency. For industrial contexts, consider using EF-UniKP with your process pH and temperature.

- Experimental Validation: Select top candidates for wet-lab kinetic assays to confirm activity.

Protocol 2: Constraining Non-Identifiable Kinetic Models with CatPred Predictions

This protocol uses computational predictions to inform the fitting of complex, non-identifiable kinetic models [22].

- Build Initial Kinetic Model: Formulate your ODE-based kinetic model, which may include many unknown parameters.

- Obtain Computational Priors: For each enzyme in the model, use CatPred with its sequence and substrate SMILES to obtain a predicted value (mean) and uncertainty (variance) for relevant parameters (kcat, Km, Ki).

- Formulate Bayesian Objective Function: Incorporate the predictions as Bayesian priors in your parameter estimation. For example, add a penalty term to the least-squares objective:

(θ_estimated - θ_predicted)² / variance_predicted. - Fit the Model: Perform parameter estimation using the regularized objective function. The priors will guide the fit toward biologically plausible values, reducing the problem of non-identifiability.

- Evaluate Identifiability: Use profile likelihood or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to assess whether parameters are now identifiable given the regularized model.

Framework Architecture & Decision Pathways

Diagram 1: The UniKP Unified Prediction Framework Workflow (31 chars)

Diagram 2: Decision Path for Selecting a Prediction Tool (45 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Digital Reagents & Databases for Kinetic Parameter Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Prediction Workflow | Key Feature for Non-Identifiable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniKP Framework [23] | Software Tool | End-to-end unified prediction of kcat, Km, kcat/Km from sequence and SMILES. | Provides jointly predicted, internally consistent parameter sets to constrain kinetic models. |

| CatPred Framework & CatPred-DB [22] | Software Tool & Benchmark Dataset | Predicts parameters with uncertainty estimates; provides a large, standardized dataset for training/evaluation. | Uncertainty quantification informs confidence in priors used for model regularization. |

| ProtT5-XL-UniRef50 [23] | Protein Language Model (pLM) | Converts amino acid sequences into informative numerical feature vectors. | Captures deep evolutionary & structural patterns, improving predictions for novel/divergent sequences. |

| SMILES Transformer [23] | Chemical Language Model | Converts substrate SMILES strings into numerical feature vectors. | Enables model to understand substrate structure, crucial for generalizing across chemistries. |

| BRENDA / SABIO-RK [23] [22] | Kinetic Parameter Databases | Primary sources of curated experimental data for model training and validation. | Ground truth for benchmarking; highlights the vast sequence-parameter gap computational tools must bridge. |

| Extra Trees Regressor [23] | Machine Learning Algorithm | The ensemble model used by UniKP to make final predictions from concatenated features. | Effective with high-dimensional features and limited data, providing robust baseline predictions. |

| D-MPNN [22] | Graph Neural Network | Used by CatPred to learn features from the 2D molecular graph of the substrate. | Directly learns from atomic connectivity, potentially capturing steric and electronic effects on Km/Ki. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q1: My model fitting with integrated structural constraints (e.g., from SKiD) fails to converge or yields unrealistic parameter estimates. What are the primary causes? A: This is often a symptom of non-identifiable parameters within your kinetic model. Common causes include:

- Over-parameterization: The model has more parameters than the available data can constrain, especially when adding structural terms.

- Correlated Parameters: Two or more parameters (e.g.,

k_catand a catalytic residue distance) have a highly correlated effect on the model output. - Insufficient Experimental Data Gradient: Data does not cover enough of the enzyme's operational range (e.g., substrate concentration, pH, mutant variants) to inform all parameters.

- Incorrect Weighting of Structural Priors: The Bayesian weight given to the 3D structural constraint (e.g., a distance restraint) is either too strong (overwhelming kinetic data) or too weak (having no effect).

Q2: How can I diagnose non-identifiable parameters when using hybrid structural-kinetic models? A: Perform a practical identifiability analysis:

- Profile Likelihood Analysis: For each parameter, fix its value across a range and re-optimize all other parameters. Plot the resulting cost function (e.g., sum of squared residuals) against the fixed parameter value. A flat profile indicates non-identifiability.

- Hessian Matrix Inspection: Compute the Hessian (matrix of second-order partial derivatives of the cost function) at the optimum. Singular or ill-conditioned Hessians with very small eigenvalues indicate unidentifiable parameter combinations.

- Ensemble Fitting: Run the fitting procedure from many different initial parameter guesses. If you obtain a wide scatter of equally good fits, parameters are not uniquely identifiable.

Q3: The SKiD dataset provides k_cat/K_M for many mutants. Can I extract individual kinetic constants (k_cat, K_M) from it for my mechanistic model?

A: Not directly for single mutants under Michaelis-Menten assumptions. k_cat/K_M is a single composite parameter. To disentangle them, you need:

- Additional Experimental Data: Direct measurements of

k_catorK_Mfor key mutants. - Global Fitting Across Mutants: Assume a specific structural-kinetic model (e.g., a linear free energy relationship linking

log(k_cat)to an electrostatic feature). Fit this model globally to thek_cat/K_Mdata for all mutants in a family to estimate underlying parameters that can predict individual constants. - Use of Complementary Datasets: Integrate with other databases that provide individual kinetic parameters where available.

Q4: How do I appropriately format 3D structural features (e.g., distances, angles, SASA) for integration into kinetic parameter estimation algorithms? A: Structural features must be transformed into quantitative terms that can be part of a model's objective function. A common method is as a Bayesian prior:

- Restraint Term: For a known critical distance

dfrom a structure, add a penalty term to the cost function:λ * (d_model - d_crystal)^2, whereλis a weighting factor. - Linear Free Energy Relationship (LFER): For features like electrostatic potential or hydrophobicity, use:

log(k) = ρ * Feature + C. The feature value is calculated from the 3D structure (e.g., using Poisson-Boltzmann solver). - Data Format: Store features in a clean table (CSV) linking each enzyme variant (WT or mutant PDB ID/chain) to its calculated feature values.

Q5: What are the best practices for validating a model that integrates kinetic and structural data? A:

- Cross-Validation: Hold out a subset of mutant kinetic data or structural perturbations during fitting. Predict their kinetics and compare to actual values.

- Predict New Mutants: Use the fitted model to predict kinetics for mutants not in the training set (e.g., double mutants), then test them experimentally.

- Check Physical Plausibility: Ensure all estimated parameters (e.g., energies, rates) fall within physically reasonable ranges.

- Comparison to Null Model: Statistically compare your integrated model's fit to a simpler model without structural terms (using F-test or AIC/BIC).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Global Fitting of Kinetic Parameters with Structural Restraints

Objective: To estimate identifiable kinetic parameters for an enzyme family by simultaneously fitting a model to kinetic data from multiple mutants, incorporating 3D structural features as restraints.

Materials: Kinetic dataset (e.g., k_cat/K_M for wild-type and mutants), structural models (PDB files for representative states), computational software (Python/R with SciPy/COPASI, PyMol).

Methodology:

- Define the Core Kinetic Model: Establish a minimal mechanistic scheme (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, pre-steady-state).

- Define Structural-Kinetic Relationship: Formulate how a structural feature (F) influences a kinetic parameter. Example:

log(k_cat_i) = log(k_cat_WT) + β * (F_i - F_WT), whereiindexes mutants. - Set Up Objective Function:

Cost = Σ (Data_i - Model_Prediction_i)^2 / σ_i^2 + λ * Σ (Structural_Deviation_j)^2. The first term is the data misfit, the second is the structural restraint penalty. - Perform Practical Identifiability Analysis: Conduct profile likelihood analysis (see FAQ A2) on the hybrid model.

- Global Optimization: Use a global optimization algorithm (e.g., differential evolution, particle swarm) to minimize the cost function across all mutant data simultaneously.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Calculate parameter confidence intervals from the profile likelihoods or via Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling.

Protocol 2: Calculating Structure-Based Features for Kinetic Modeling

Objective: To compute quantitative descriptors from enzyme 3D structures that can be correlated with kinetic parameters.

Materials: High-quality PDB file(s), software for molecular analysis (e.g., PyMol, Rosetta, FoldX, APBS).

Methodology:

- Structure Preparation: Use a tool like

pdb_toolsor PyMol to remove heteroatoms, add missing hydrogens, and select relevant chains. Ensure the catalytic residue protonation states are correct. - Feature Calculation:

- Distances: Calculate key atomic distances (e.g., between catalytic atoms, or substrate binding atoms) using PyMol's

distancecommand. - Electrostatics: Use APBS to solve the Poisson-Boltzmann equation and calculate the electrostatic potential at key locations.

- Stability (ΔΔG): Use FoldX or Rosetta

ddg_monomerto estimate the change in folding stability upon mutation. - Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Compute SASA of the active site or substrate using PyMol or MDTraj.

- Distances: Calculate key atomic distances (e.g., between catalytic atoms, or substrate binding atoms) using PyMol's

- Tabulation: Create a feature matrix where rows are enzyme variants and columns are the calculated features. Normalize features if necessary.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Example SKiD Dataset Extract for a Model Enzyme (Hypothetical Data)

| Variant (PDB ID/Mutation) | k_cat/K_M (M^-1 s^-1) |

Reported in SKiD | Catalytic Distance (Å) | Active Site Electrostatic Potential (kT/e) | Calculated ΔΔG (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (1ABC) | 1.2 x 10^6 | Yes | 3.5 | -5.2 | 0.0 |

| D120A (Modeled) | 5.4 x 10^3 | Yes | 5.8 | -1.1 | +2.5 |

| H195Q (1ABD) | 8.9 x 10^4 | Yes | 3.7 | -3.8 | +0.7 |

| K73R (Modeled) | 9.8 x 10^5 | Yes | 3.4 | -4.9 | -0.3 |

Table 2: Identifiability Diagnostics for a Hybrid Model Fit

| Parameter | Best-Fit Value | Profile Likelihood Identifiable? (Y/N) | 95% Confidence Interval | Correlation with k_cat_WT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

k_cat_WT |

450 s^-1 | Yes | [420, 485] | 1.00 |

K_M_WT |

15 µM | No | [5, 100] | -0.85 |

β_distance |

-1.2 Å^-1 | Yes | [-1.5, -0.9] | 0.10 |

λ_restraint |

0.5 | No | [0.01, 5.0] | -0.05 |

The Scientist's Toolkit