Harnessing Uncertainty: A Practical Guide to Bayesian Parameter Estimation in Enzyme Kinetics

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Bayesian parameter estimation in enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Harnessing Uncertainty: A Practical Guide to Bayesian Parameter Estimation in Enzyme Kinetics

Abstract

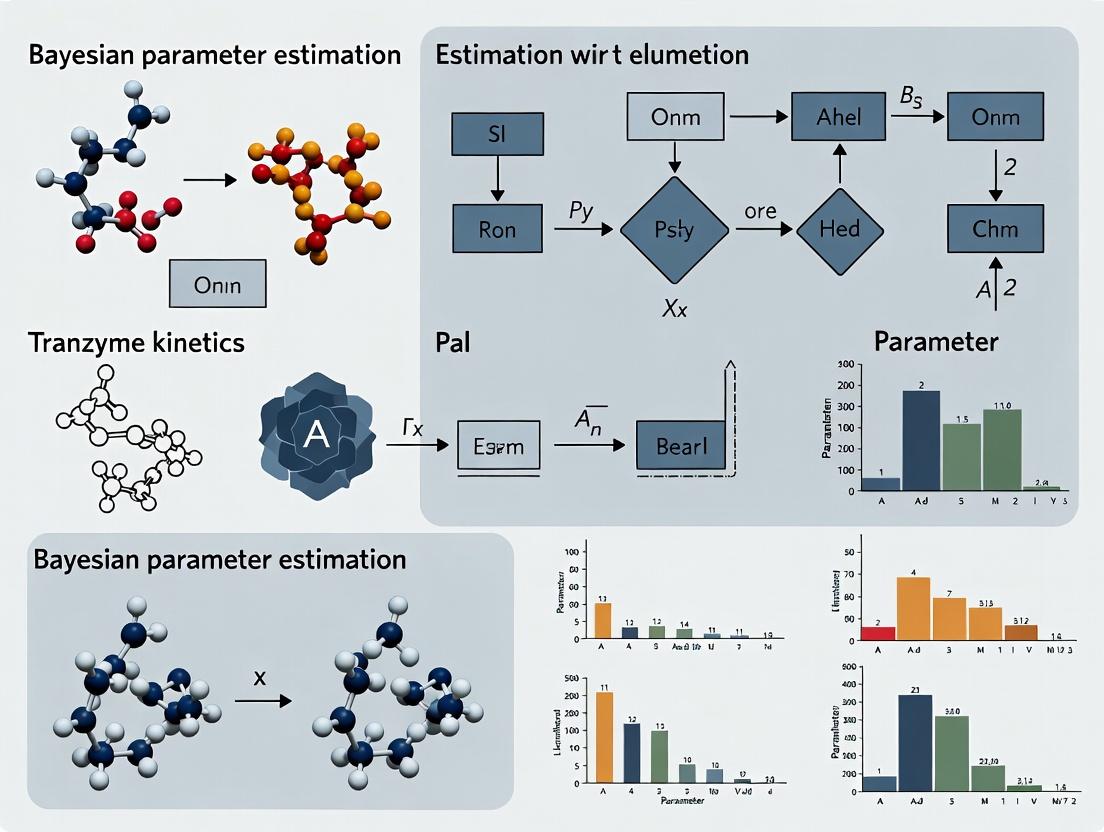

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Bayesian parameter estimation in enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the foundational advantages of the Bayesian framework over classical methods for quantifying uncertainty in key parameters like kcat and Km. The guide then details modern methodological workflows, from designing efficient experiments using Bayesian principles to implementing computational frameworks like Maud for inference. It addresses common troubleshooting challenges in model selection, parameter identifiability, and computational efficiency. Finally, it validates the approach by comparing its performance against traditional and machine-learning methods, and explores its transformative applications in high-throughput studies, dynamic metabolic modeling, and therapeutic drug monitoring. The synthesis demonstrates how Bayesian methods provide robust, probabilistic estimates essential for reliable modeling and decision-making in biomedical research.

Why Bayesian? Quantifying Uncertainty in Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

The Limitations of Classical Point Estimation for kcat and Km

The determination of the Michaelis constant (Km) and the catalytic turnover number (kcat) forms the cornerstone of quantitative enzymology, underpinning efforts in drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and systems biology [1]. Classical point estimation methods, which rely on fitting initial velocity data to the Michaelis-Menten equation, provide single-value parameter estimates [2]. However, within the broader thesis of advancing Bayesian parameter estimation in enzyme kinetics research, these classical approaches reveal significant and often overlooked limitations. They typically fail to account for parameter uncertainty, time-dependent kinetic complexities, and the context-dependent nature of kinetic constants, potentially leading to unreliable models and misleading conclusions in research and development [1] [3]. This application note details these limitations and provides protocols for modern methodologies that address these shortcomings through full progress curve analysis and Bayesian inference.

Core Limitations of Classical Point Estimation

Classical point estimation methods are predicated on several assumptions that are frequently violated in experimental practice. The table below summarizes the key limitations, their underlying causes, and their consequences for research and development.

Table: Key Limitations of Classical Point Estimation for kcat and Km

| Limitation | Primary Cause | Consequence for Research/Development |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring Parameter Uncertainty | Provides only a single best-fit value without confidence intervals or distributions [1]. | Poor reproducibility; inability to propagate error in systems models (garbage-in, garbage-out) [1]. |

| Susceptibility to Assay Artifacts | Reliance on initial velocity measurements, which can be distorted by hysteretic behavior (lag/burst phases) [3], product inhibition [4], or enzyme instability [4]. | Inaccurate parameters that misrepresent true enzyme function and inhibitor potency. |

| Context-Dependent Parameter Values | Km and kcat are not true constants but vary with pH, temperature, ionic strength, and buffer composition [1]. | Data collected under non-physiological assay conditions poorly predict in vivo behavior [1]. |

| Inadequate for Complex Kinetics | Assumes simple Michaelis-Menten behavior, failing to capture cooperativity, multi-substrate mechanisms, or allostery without specialized models [1]. | Mischaracterization of enzyme mechanism and regulation. |

| Data Quality and Reporting Issues | Use of historical data from sources like BRENDA where assay conditions (temperature, pH) may be non-physiological or poorly documented [1]. | Integration of incompatible data into models reduces predictive accuracy. |

Detailed Protocol: Full Progress Curve Analysis for Detecting Kinetic Complexities

A critical flaw in classical analysis is its reliance on initial velocities, which can mask time-dependent phenomena. This protocol outlines a robust method for acquiring and analyzing full reaction progress curves to uncover such complexities and extract more reliable parameters [3] [4].

Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: Full Progress Curve Analysis Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Assay Configuration for Continuous Monitoring Configure a spectrophotometric, fluorometric, or other continuous assay to monitor product formation or substrate depletion in real-time. For a typical 1 mL reaction in a cuvette, use a total enzyme concentration ([E]₀) that is at least 100-fold lower than the anticipated Km to maintain steady-state assumptions. Initiate the reaction by the addition of enzyme [3].

Step 2: High-Resolution Data Acquisition Record the signal (e.g., absorbance) at frequent intervals (e.g., every 0.5-1 second) for a duration sufficient to capture the approach to equilibrium or significant substrate depletion (>50%). Perform replicates across a wide range of substrate concentrations, spanning from 0.2Km to 5Km at minimum [4].

Step 3: Data Pre-processing and Derivative Calculation Convert the raw signal to product concentration ([P]) using an appropriate calibration curve. Smooth the [P] vs. time data using a Savitzky-Golay filter or similar to reduce noise. Calculate the instantaneous reaction velocity (v) at each time point as the first derivative (d[P]/dt) [3].

Step 4: Identification of Atypical Kinetics Visually inspect the progress curves and their first derivatives. Key indicators of complexity include:

- Hysteretic Lag Phase: Velocity increases over time from an initial value (Vi) to a steady-state velocity (Vss) [3].

- Hysteretic Burst Phase: Velocity decreases over time from a high initial burst to a lower Vss [3].

- Rapid Deceleration: A velocity decline faster than predicted by substrate depletion alone, suggesting significant product inhibition or enzyme inactivation [4].

Step 5: Model Fitting and Parameter Estimation

- For Classical Michaelis-Menten Behavior: Fit the initial velocity (v₀) data from the linear portion of multiple progress curves directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression to obtain point estimates for Vmax and Km [2].

- For Complex Time-Dependent Behavior: Fit the entire progress curve data to an integrated rate equation that accounts for the observed phenomenon. For example, for a hysteretic enzyme with a lag phase, fit to the equation:

[P] = Vss*t - ((Vss - Vi)/k)*(1 - exp(-k*t))where k is the rate constant for the slow transition between enzyme conformations [3]. Numerical integration of differential equations (including terms for substrate depletion, product inhibition, or enzyme inactivation) is performed using software like Tellurium, COPASI, or MATLAB [4] [5].

Protocol: Implementing a Bayesian Estimation Framework

Bayesian methods address the core limitation of uncertainty quantification by treating parameters as probability distributions. This protocol outlines a hybrid machine learning-Bayesian inversion framework for robust parameter estimation, as demonstrated with graphene field-effect transistor (GFET) data [6].

Bayesian Workflow Process

Diagram Title: Bayesian Parameter Estimation Process

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Establish Prior Distributions Quantify prior knowledge about the parameters (Km, kcat). If literature values exist, define a prior distribution (e.g., a log-normal distribution) where the mean is the literature value and the standard deviation reflects confidence. For unexplored enzymes, use weakly informative priors (e.g., broad uniform distributions over a plausible biochemical range) [7].

Step 2: Acquire High-Quality Experimental Data Follow the protocol in Section 2 to generate high-resolution progress curve data. This data forms the likelihood function, P(Data | Parameters). The use of full progress curves, rather than just initial velocities, provides a much richer dataset to constrain parameter estimates [3].

Step 3: Develop a Computational Surrogate Model For complex or computationally expensive kinetic models (e.g., integrated rate laws with multiple parameters), train a deep neural network (DNN), such as a multilayer perceptron (MLP), to act as a fast surrogate (emulator). Train the DNN on simulated progress curves generated from a wide range of parameter values. This DNN will predict the progress curve given any input parameter set, dramatically speeding up the Bayesian inference process [6].

Step 4: Perform Bayesian Inference Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling (e.g., using PyMC3, Stan, or the Maud tool [5]) to compute the posterior distribution. The sampling algorithm iteratively evaluates the likelihood of the observed data given proposed parameter values (using the DNN surrogate), weighted by the prior, to build the posterior distribution: P(Parameters | Data) ∝ P(Data | Parameters) × P(Parameters).

Step 5: Analyze Posterior and Inform Design The result is a joint probability distribution for Km and kcat, fully quantifying estimation uncertainty and correlation between parameters. Use this posterior to calculate credible intervals (e.g., 95% highest density interval). Furthermore, apply Bayesian optimal experimental design principles: use the current posterior to simulate which new experimental conditions (e.g., substrate concentrations) would maximize the reduction in parameter uncertainty in the next experiment, creating an efficient, iterative research loop [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Tools for Advanced Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Item | Function & Importance | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Continuous Assay Detection System | Enables real-time monitoring of progress curves, essential for detecting kinetic complexities [3]. | Spectrophotometer with rapid kinetic capability; Fluorometer; Graphene Field-Effect Transistor (GFET) biosensors for label-free, real-time detection [6]. |

| Hysteretic / Allosteric Enzyme Standards | Positive controls for validating protocols for detecting time-dependent kinetics. | Commercially available hysteretic enzymes (e.g., certain phosphofructokinases). |

| Bayesian Inference Software | Core platform for parameter estimation with uncertainty quantification. | Maud (specialized for kinetic models) [5], PyMC3, Stan, Tellurium [5]. |

| Kinetic Modeling & Simulation Suite | For numerical integration of ODEs, fitting complex models, and simulating experiments. | COPASI, Tellurium [5], MATLAB with SimBiology, Python (SciPy). |

| Curated Kinetic Parameter Database | Source of prior knowledge for Bayesian analysis and model building. | STRENDA DB (emphasizes standardized reporting) [1], SABIO-RK [1]. |

| High-Throughput Model Construction Tool | Accelerates building large-scale kinetic models for systems biology. | SKiMpy (semi-automated workflow for genome-scale models) [5]. |

Within the context of enzyme kinetics research, Bayesian parameter estimation provides a coherent probabilistic framework for integrating prior knowledge with experimental data to quantify uncertainty in kinetic constants [8]. This approach is increasingly vital for drug development, where accurate predictions of enzyme behavior underpin inhibitor design and therapeutic efficacy [9]. Unlike classical methods that produce single-point estimates, Bayesian inference yields full posterior probability distributions for parameters such as (Km) and (V{max}), explicitly representing uncertainty and enabling robust predictions of metabolic flux responses to perturbations [10] [11].

The core of the method is Bayes' theorem: (P(\phi|y) = \frac{P(y|\phi) P(\phi)}{P(y)}). Here, (P(\phi|y)) is the posterior distribution of parameters (\phi) given data (y), (P(y|\phi)) is the likelihood, (P(\phi)) is the prior distribution, and (P(y)) is the marginal likelihood [10] [8]. In enzymology, the prior can incorporate literature values or expert knowledge, the likelihood is defined by the kinetic model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten), and the posterior provides updated, probabilistic parameter estimates [12] [13]. This framework is particularly powerful for analyzing complex, compartmentalized enzymatic systems and for designing experiments that efficiently reduce parameter uncertainty [10] [9].

Comparative Analysis: Classical vs. Bayesian Approaches in Enzyme Kinetics

Table 1: Comparison of classical and Bayesian approaches for enzyme kinetic parameter estimation.

| Aspect | Classical (Frequentist) Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Output | Single-point estimate (e.g., least-squares fit). | Full posterior probability distribution. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Confidence intervals based on hypothetical repeated experiments. | Credible intervals representing direct probability statements about parameters. |

| Incorporation of Prior Knowledge | Not formally integrated; separate from analysis. | Formally integrated via prior distributions (P(\phi)). |

| Handling of Complex Models | Can be difficult, prone to overfitting with limited data [10]. | Priors and hierarchical models naturally regularize and stabilize estimation [8] [12]. |

| Experimental Design | Often relies on established substrate ranges and replicates [9]. | Enables optimal design by maximizing expected information gain from the posterior [9] [13]. |

| Computational Demand | Typically lower (optimization). | Higher (sampling from posterior via MCMC or variational inference) [8] [5]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Inference for Compartmentalized Enzyme Systems

This protocol details the process of generating experimental data from enzyme-loaded hydrogel beads in a flow reactor, suitable for subsequent Bayesian kinetic analysis [10].

Materials and Reagent Preparation

- Enzyme Solution: Purified enzyme of interest in suitable buffer.

- Monomer Solution: 19% (w/v) acrylamide, 1% (w/v) N,N′-methylenebis(acrylamide) in 1x PBS.

- Functionalization Reagents: For enzyme-first method: 6-acrylaminohexanoic acid succinate (AAH-Suc) linker, NHS/EDC coupling reagents [10].

- Photoinitiator: 2,2′-Azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride or equivalent.

- Oil Phase: HFE-7500 fluorinated oil with 2% (w/w) PEG-PFPE amphiphilic block copolymer surfactant.

- Flow Reactor System: Continuously Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR), syringe pumps (e.g., Cetoni neMESYS), polycarbonate membrane (5 µm pore) to retain beads [10].

Stepwise Procedure

Part A: Enzyme Immobilization in Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Beads

- Method 1 (Enzyme-First Functionalization):

- React enzyme solution with AAH-Suc linker via NHS chemistry to introduce polymerizable acrylamide groups.

- Mix functionalized enzyme with monomer solution and photoinitiator.

- Generate monodisperse water-in-oil droplets using a microfluidic droplet generator.

- Polymerize droplets via UV exposure (365 nm, 5-10 mW/cm² for 60 s) to form Polyacrylamide-Enzyme Beads (PEBs) [10].

- Method 2 (Bead-First Functionalization):

- Produce empty hydrogel beads via microfluidics using a monomer mix containing acrylic acid.

- After polymerization, activate carboxyl groups on beads with EDC/NHS.

- Incubate activated beads with enzyme solution for covalent coupling via lysine amines [10].

Part B: Flow Reactor Experimentation & Data Collection

- Reactor Setup: Load a defined volume of PEBs into the CSTR. Seal reactor outlets with polycarbonate membranes.

- Substrate Perfusion: Using high-precision syringe pumps, perfuse the CSTR with substrate solutions at a range of controlled inflow concentrations (([S]{in})) and flow rates (determining dilution rate (kf)).

- Steady-State Achievement: For each condition (([S]{in}), (kf)), perfuse until product concentration in the outflow stabilizes (typically 5-10 reactor volumes).

- Product Measurement:

- Data Output: Record steady-state product concentration ([P]{ss}) for each experimental condition defined by the control parameters (\theta = ([S]{in}, kf)). This dataset (y = {[P]{ss}}) is the input for Bayesian inference.

Computational Workflow and Implementation

Model Specification

The kinetic-dynamic model for a single-enzyme, single-substrate reaction in a CSTR is described by Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) [10]: [ \frac{d[S]}{dt} = kf([S]{in} - [S]) - \frac{V{max}[S]}{KM + [S]} ] [ \frac{d[P]}{dt} = \frac{V{max}[S]}{KM + [S]} - kf[P] ] where (V{max} = k{cat} \cdot [E]total) and (KM) are the kinetic parameters (\phi) to be inferred. The steady-state solution ([P]{ss} = g(\phi, \theta)) is used in the likelihood function [10].

Prior and Likelihood Formulation

- Priors ((P(\phi))): Specify distributions for (k{cat}), (KM), and the observation error (\sigma). Use weakly informative priors (e.g., Half-Normal for scale parameters) if knowledge is limited, or informative priors from literature to constrain estimates [12] [13].

- Likelihood ((P(y|\phi))): Assume observed data is normally distributed around the model prediction: ([P]{obs} \sim \mathcal{N}([P]{ss}(\phi, \theta), \sigma^2)). The error (\sigma) accounts for experimental and measurement noise [10].

Posterior Inference and Analysis

Sampling from the posterior distribution (P(\phi|y)) is performed using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms.

- Tool Recommendation: Use PyMC3 or Stan, which provide high-level interfaces for model specification and implement efficient samplers like the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) [10] [8].

- Workflow:

- Code the model, priors, and likelihood.

- Run multiple MCMC chains (typically 4) to ensure convergence.

- Diagnose convergence using statistics like (\hat{R}) (Gelman-Rubin statistic) and visualize trace plots.

- Analyze the posterior: plot marginal distributions for (k{cat}) and (KM), report posterior medians and 95% credible intervals, and examine pairwise correlations between parameters [12].

Diagram: The Bayesian Inference Workflow for Enzyme Kinetics. The process integrates prior knowledge and experimental data into a probabilistic model. Computational sampling yields a posterior distribution, which is analyzed for parameter estimates and predictions.

Advanced Applications in Metabolic Network Analysis

Bayesian methods extend beyond single-enzyme studies to system-level metabolic networks. The BayesianSSA framework combines Structural Sensitivity Analysis (SSA) with Bayesian inference to predict metabolic flux responses to enzyme perturbations (e.g., up/down-regulation) [11].

- Mechanism: SSA predicts qualitative flux changes based solely on network topology. BayesianSSA treats the undefined sensitivity variables in SSA as stochastic, learning their posterior distributions from limited perturbation data [11].

- Advantage: It requires far fewer parameters than full kinetic modeling (e.g., one variable per reaction vs. multiple kinetic constants) and provides probabilistic predictions (e.g., "90% confidence that flux will increase") [11].

- Utility in Drug Development: This approach efficiently identifies high-confidence metabolic engineering targets or off-target effects of enzyme inhibitors within complex pathways like central carbon metabolism [11].

Table 2: Key Computational Frameworks for Bayesian Kinetic Modeling.

| Framework/Tool | Primary Language | Key Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyMC3/Stan | Python/Stan | General-purpose probabilistic programming; NUTS sampler; extensive community [10] [8]. | General Bayesian modeling, including custom enzyme kinetic models. |

| Maud | Python | Dedicated to Bayesian statistical inference of kinetic models using various omics data [5]. | Parameter estimation with uncertainty for medium-scale metabolic models. |

| BayesianSSA | N/A (Methodology) | Integrates network structure with perturbation data for flux response prediction [11]. | Predicting qualitative effects of enzyme perturbations in large networks. |

| SKiMpy | Python | Semi-automated construction & sampling of large-scale kinetic models [5]. | Building and analyzing genome-scale kinetic models. |

- Microfluidic Droplet Generator & UV Light Source: For producing monodisperse polyacrylamide beads containing enzymes [10].

- Continuously Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR) with Sealed Outflow: Provides a controlled environment for steady-state kinetic measurements of immobilized enzymes [10].

- High-Precision Syringe Pump System (e.g., neMESYS): Ensures accurate and reproducible control of substrate inflow rates, a critical experimental parameter [10].

- Online Spectrophotometer or HPLC: For accurate quantification of substrate consumption or product formation over time [10].

- Probabilistic Programming Software (PyMC3, Stan): Essential platforms for specifying Bayesian models and performing MCMC sampling [10] [12].

- Kinetic Parameter Databases (e.g., BRENDA, SABIO-RK): Sources for constructing informative prior distributions for common enzymes [5].

Diagram: Computational Pipeline for Bayesian Kinetic Parameter Estimation. The workflow is iterative; if MCMC chains fail to converge, model specification or sampling parameters must be adjusted.

Bayesian inference transforms enzyme kinetics from a deterministic curve-fitting exercise into a probabilistic knowledge-updating process. By formally integrating prior information and explicitly quantifying uncertainty in parameters like (Km) and (k{cat}), it provides a more robust foundation for predictive modeling in drug discovery and metabolic engineering [9] [13]. The integration of Bayesian methods with high-throughput experimental platforms and large-scale metabolic modeling frameworks represents the future of quantitative systems biology, enabling the rational design of enzymes and pathways with predictable behaviors [10] [5].

In enzyme kinetics research and drug development, accurately estimating parameters such as reaction rates, binding affinities, and enzyme turnover numbers is paramount. Traditional frequentist approaches provide point estimates but often lack a quantitative measure of the uncertainty associated with these estimates. Bayesian parameter estimation addresses this gap by framing unknowns as probability distributions, allowing researchers to integrate prior knowledge with experimental data systematically [14].

At the heart of this framework lies Bayes' theorem, which mathematically describes how prior beliefs are updated with new evidence to form a posterior understanding. For kinetic parameter estimation, this translates to combining a prior distribution of the parameters (based on historical data or expert knowledge) with a likelihood function (derived from new experimental data) to obtain a posterior distribution [15]. The posterior distribution fully characterizes the updated knowledge and uncertainty about the kinetic parameters given all available information.

This paradigm is especially powerful in kinetics because it can handle complex, nonlinear models common in enzyme dynamics, incorporate constraints from physical laws, and propagate measurement noise through to parameter uncertainty [16]. It provides a coherent probabilistic framework for tasks ranging from single-molecule binding analysis to the optimization of biocatalytic processes [17] [18].

Core Conceptual Foundations

The Bayesian Triad: Prior, Likelihood, and Posterior

The mechanism of Bayesian inference is governed by the continuous interplay of three core components, as formalized by Bayes' theorem [14]:

P(θ|X) = [ P(X|θ) • P(θ) ] / P(X)

- Prior Distribution (P(θ)): This represents the initial belief about the kinetic parameters (θ) before observing the new experimental data. It can be formulated from historical results, literature values, or physical constraints (e.g., a reaction rate constant must be positive). The choice of prior can be informative, weakly informative, or non-informative [19].

- Likelihood Function (P(X|θ)): This quantifies the probability of observing the acquired experimental data (X) given a specific set of parameters (θ). It is a function of the parameters and encapsulates the stochastic model of the experiment (e.g., Gaussian noise in a fluorescence signal) [15].

- Posterior Distribution (P(θ|X)): This is the ultimate goal of Bayesian analysis. It represents the updated probability distribution of the parameters after assimilating the evidence from the new data. It is proportional to the product of the prior and the likelihood [20].

The denominator, P(X) (the evidence or marginal likelihood), serves as a normalizing constant ensuring the posterior distribution integrates to one. It is crucial for model comparison but can often be omitted when focusing on parameter estimation for a single model [14].

Contrasting Frequentist and Bayesian Perspectives

The philosophical and practical differences between the classical frequentist approach and the Bayesian approach are significant, particularly in parameter estimation [14] [15].

- Frequentist (Maximum Likelihood Estimation - MLE): Treats parameters (θ) as fixed, unknown constants. The best estimate, ( \theta{MLE} ), is found by maximizing the likelihood function: ( \theta{MLE} = argmax_{\theta} P(X|\theta) ). It provides a single point estimate, and uncertainty is typically expressed via confidence intervals derived from the theoretical sampling distribution of the estimator [15].

- Bayesian: Treats parameters (θ) as random variables with their own probability distributions. Inference is based on the posterior distribution, ( P(θ|X) ). A point estimate can be obtained by taking the mean, median, or mode (Maximum a Posteriori - MAP) of the posterior. Crucially, uncertainty is directly described by the spread and shape of the posterior distribution, yielding credible intervals that have a more intuitive probabilistic interpretation [15].

A key advantage of the Bayesian framework in kinetics is its ability to naturally incorporate prior knowledge. For instance, when estimating a dissociation constant (Kd), a researcher can use a prior based on values reported for similar enzyme-substrate pairs, thereby stabilizing estimates from noisy or sparse data [19].

Application in Enzyme Kinetics Research

The Bayesian framework is broadly applicable across various scales of kinetic analysis, from ensemble enzyme assays to single-molecule observations.

Estimating Michaelis-Menten Parameters

The Michaelis-Menten model, fundamental to enzyme kinetics, describes the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity. Bayesian inference can robustly estimate its parameters, the Michaelis constant (Km) and the maximum velocity (Vmax). A common challenge is the heteroscedastic noise in velocity measurements. A Bayesian model can explicitly account for this by defining a likelihood where the error variance scales with the predicted velocity. Informative priors for Km and Vmax, perhaps based on the enzyme class or preliminary experiments, can be applied to regularize the estimation, preventing biologically implausible values and improving convergence in numerical methods [6].

Analyzing Single-Molecule Binding Kinetics

Single-molecule techniques, like Co-localization Single-Molecule Spectroscopy (CoSMoS), generate rich data on binding events but present analytical challenges due to low signal-to-noise ratios and the need to distinguish specific from non-specific binding [17]. An automated Bayesian pipeline has been developed to address these issues [17]. It employs a Variational Bayesian approach to fit a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) to the fluorescence time traces. This allows for the probabilistic identification of different molecular binding states (e.g., unbound, singly bound, doubly bound) and the direct estimation of association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants along with their uncertainties. The prior distributions here can enforce physical constraints, such as positive rate constants.

Optimizing Bioprocess and Experimental Design

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful strategy for efficiently optimizing expensive-to-evaluate functions, such as the yield of a biocatalytic process that depends on multiple conditions (pH, temperature, substrate concentration) [21]. BO treats the unknown objective function (e.g., reaction yield) as a random function, typically modeled by a Gaussian Process (GP). It uses an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement), which balances exploration and exploitation based on the posterior predictive distribution of the GP, to sequentially select the next most informative experimental conditions to test. This results in finding optimal process parameters in far fewer experiments compared to traditional grid or factorial searches [21].

Table 1: Common Prior Distributions in Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Parameter Type | Typical Prior Choice | Rationale | Example in Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Rate Constant | Log-Normal, Gamma | Ensures values are strictly >0; log-normal can capture order-of-magnitude uncertainty. | Association rate (kon), catalytic constant (kcat). |

| Parameter on (0,1) Interval | Beta | Naturally bounded between 0 and 1; flexible shape. | Fraction of active enzyme, efficiency. |

| Uninformed Scale Parameter | Half-Cauchy, Inverse Gamma | Weakly informative, allows for heavy tails while penalizing extremely large values. | Standard deviation of measurement noise. |

| Location Parameter | Normal (with wide variance) | Uninformative over a broad but plausible range. | Mid-point of a pH activity profile. |

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Methods for Posterior Estimation

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Use Case in Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | Draws correlated samples from the posterior via a random walk. | Asymptotically exact; provides gold-standard inference. | Computationally intensive; requires convergence diagnostics. | Detailed analysis of well-defined kinetic models with moderate complexity [16]. |

| Variational Inference (VI) | Approximates the posterior with a simpler, tractable distribution. | Often much faster than MCMC; scales well. | Approximation may be biased; limited by choice of variational family. | Real-time or high-throughput analysis of single-molecule data [17]. |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) | Accepts parameter samples that produce simulated data close to real data. | Doesn't require explicit likelihood; useful for complex stochastic models. | Can be inefficient; approximation error hard to quantify. | Inference for stochastic simulation models of metabolic networks [18]. |

| Deep Learning-Based | Trains a neural network to directly map data to posterior estimates. | Extremely fast after training; can learn complex features. | Requires large training datasets; "black-box" nature. | Rapid analysis of high-dimensional data like dynamic PET imaging for tracer kinetics [16]. |

Bayesian Inference Workflow in Kinetics

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bayesian Estimation of Enzyme Kinetics via Microplate Assay

Objective: To determine the posterior distributions for Km and Vmax of an enzyme using a fluorescence-based activity assay.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme.

- Fluorogenic substrate.

- Assay buffer.

- 96-well or 384-well microplate.

- Plate reader with kinetic fluorescence capability.

- Software: Python (with PyMC, NumPy, SciPy) or R (with rstan, brms).

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Prepare a serial dilution of the substrate across a range spanning the expected Km (e.g., 0.1x to 10x Km). Include replicates (n≥3) for each concentration and negative controls (no enzyme).

- Data Acquisition: Initiate reactions in the plate reader. Record fluorescence intensity (relative fluorescence units, RFU) over time (e.g., every 30 seconds for 30 minutes).

- Data Preprocessing: For each substrate concentration [S], calculate the initial velocity (v0) by performing a linear regression on the early, linear phase of the RFU vs. time plot. Convert RFU to product concentration using a calibration curve if absolute rates are required.

- Define the Bayesian Model:

- Likelihood: Assume observed velocities (vobs) are normally distributed around the Michaelis-Menten prediction: vobs ~ Normal(vpred, σ). Model heteroscedasticity by letting σ scale with vpred (e.g., σ = vpred * ε).

- Priors: Place weakly informative priors: Km ~ LogNormal(log(estimatedKm), 0.5); Vmax ~ LogNormal(log(estimatedVmax), 0.5); ε ~ HalfNormal(0.1).

- Model Specification: vpred = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S]).

- Posterior Computation: Use MCMC sampling (e.g., No-U-Turn Sampler in PyMC) to draw samples from the joint posterior of {Km, Vmax, ε}. Run multiple chains and check convergence diagnostics (R-hat ≈ 1.0, effective sample size).

- Analysis: Report the posterior median and 95% credible interval for Km and Vmax. Visualize the posterior predictive checks by plotting the observed data with a cloud of predicted Michaelis-Menten curves generated from posterior samples.

Protocol 2: Automated Bayesian Analysis of Single-Molecule Binding Data

Objective: To automatically extract association and dissociation rate constants from CoSMoS imaging data [17].

Materials:

- Surface-immobilized target molecules.

- Fluorescently labeled ligand/mobile component.

- Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscope.

- Automated analysis pipeline software (e.g., custom software as described in [17]).

Procedure:

- Image Acquisition: Record a time-lapse movie with two channels: one for the immobilized target (e.g., Cy3) and one for the diffusing ligand (e.g., Cy5).

- Preprocessing (Automated):

- Gain Calibration: Estimate camera gain and offset using calibration data to work in photon units.

- Channel Alignment: Use images of multicolor fluorescent beads to compute an affine transformation matrix to align the two camera channels.

- Drift Correction: Calculate and correct for stage drift by correlating features across consecutive frames.

- Spot Detection & Localization (Automated):

- Identify target molecule positions using statistical detection that controls false positives.

- For each target, detect co-localization events by analyzing the ligand channel signal. Apply criteria: distance-to-target, spot width consistent with point-spread-function, and signal-to-background ratio.

- Kinetic Analysis via Bayesian HMM:

- For each validated binding event time trace, model it as a two-state (bound/unbound) HMM.

- Likelihood: The observed fluorescence intensity in each frame is modeled with a Gaussian distribution whose mean depends on the hidden state (unbound = background level, bound = background + signal).

- Priors: Place priors on the transition probabilities (related to kon and koff) and emission parameters.

- Posterior Inference: Use a Variational Bayesian algorithm to approximate the posterior distributions of the HMM parameters and the most likely sequence of hidden states.

- Population-Level Estimation: Pool state transition data from all analyzed molecules to compute final posterior distributions for the association rate (kon) and dissociation rate (koff).

Single-Molecule Data Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function in Bayesian Kinetic Studies | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Enzyme Substrates | Generate a time-dependent fluorescent signal proportional to product formation, providing the raw data (X) for likelihood computation. | Select for high turnover, photostability, and a linear relationship between fluorescence and product concentration over the assay range. |

| Quartz Cuvettes / Low-Binding Microplates | Minimize non-specific binding and background signal, which reduces noise and simplifies the error model in the likelihood function. | Essential for obtaining high-quality, reproducible data where the signal model (e.g., Gaussian noise) is valid. |

| Neutralvidin-Coated Surfaces / PEG-Passivated Coverslips | For single-molecule studies, these provide specific immobilization of biotinylated targets while minimizing non-specific adsorption of ligands. | Critical for reducing false-positive binding events, ensuring the HMM analyzes primarily specific interactions [17]. |

| Precision Syringe Pumps & Flow Cells | Enable rapid and precise changes in reactant concentration for measuring association/dissociation kinetics under continuous flow. | Provides the controlled experimental perturbation needed to inform the dynamic parameters in the kinetic model. |

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for Bayesian Kinetic Analysis

| Software / Package | Primary Use | Applicable Kinetic Problem | Source / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyMC / Stan (PyStan, cmdstanr) | General-purpose probabilistic programming for defining custom Bayesian models and performing MCMC/VI sampling. | Estimating parameters for custom enzyme mechanisms, pharmacodynamic models, or complex bioprocess models. | [21] [22] |

| Custom CoSMoS Pipeline | Automated end-to-end analysis of single-molecule binding movies, including Bayesian HMM analysis. | Extracting association/dissociation rates from single-molecule co-localization data. | [17] |

| Bayesian Optimization Libraries (BoTorch, GPyOpt) | Implementing Bayesian Optimization loops for experimental design. | Optimizing yield/titer in biocatalysis or fermentation by sequentially selecting culture conditions. | [21] |

| Improved Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (iDDPM) | Deep learning-based method for rapid posterior estimation in high-dimensional problems. | Estimating kinetic parameter maps from dynamic medical imaging data (e.g., PET) [16]. | [16] |

| MSIQ | Joint modeling of multiple RNA-seq samples under a Bayesian framework for isoform quantification. | Inferring kinetic parameters of RNA processing from transcriptomic time-series data. | [22] |

Quantitative knowledge of enzyme kinetic parameters, particularly the Michaelis constant ((Km)) and the turnover number ((k{cat})), is foundational for modeling metabolic networks, predicting cellular behavior, and guiding drug discovery [1]. However, these parameters are not fixed constants; they are conditional on the experimental environment and subject to significant uncertainty from measurement error, biological variability, and gaps in data [23] [1]. Traditional point estimates provide a false sense of precision, obscuring the reliability of model predictions and downstream engineering decisions.

Bayesian parameter estimation addresses this critical gap by explicitly quantifying uncertainty through credible intervals. Unlike frequentist confidence intervals, a 95% credible interval represents a 95% probability that the true parameter value lies within that range, given the observed data and prior knowledge [24]. This probabilistic interpretation is intuitive and directly actionable for risk assessment. Within a broader thesis on Bayesian methods in enzyme kinetics, this document provides the essential application notes and protocols for researchers to implement these techniques, correctly interpret parameter uncertainty, and leverage the full critical advantage of credible intervals in metabolic research and drug development.

Core Quantitative Comparisons of Bayesian Kinetic Methods

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics of contemporary Bayesian approaches to enzyme kinetic parameter estimation, enabling researchers to select appropriate methods for their specific applications.

Table 1: Performance of Bayesian Predictive Models for (Km) and (k{cat}) Data derived from the evaluation of Bayesian Multilevel Models (BMMs) as implemented in the ENKIE tool [23].

| Metric | Parameter | Model Performance | Comparison to Gradient Boosting (GB) | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Accuracy (R²) | (K_m) (Affinity) | 0.46 [23] | Slightly lower than GB (0.53) [23] | BMMs achieve competitive accuracy using only categorical data (EC numbers, identifiers) versus sequence/structure features used by deep learning. |

| (k_{cat}) (Turnover) | 0.36 [23] | Slightly lower than GB (0.44) [23] | ||

| Uncertainty Calibration | (Km) & (k{cat}) | Predicted RMSE matches effective RMSE across uncertainty bins [23]. | Standard test RMSE frequently over- or under-estimates error [23]. | Bayesian-predicted uncertainties are well-calibrated, providing a reliable measure of prediction trustworthiness for individual parameters. |

| Key Determinants (Largest Group-Level Effects) | (K_m) | Substrate [23] | N/A | Substrate identity is most informative for affinity; specific enzyme reaction is most informative for turnover rate. |

| (k_{cat}) | Reaction Identifier [23] | N/A | ||

| Variance Explained by Organism (Protein) Effect | (K_m) | 13.2% [23] | N/A | (Km) is more conserved across organisms than (k{cat}), making predictions for uncharacterized organisms more reliable for affinity. |

| (k_{cat}) | 23.9% [23] | N/A |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Bayesian Frameworks for Kinetic Modeling Synthesis of methodological approaches for different data types and scales.

| Framework / Tool | Primary Application | Core Methodology | Key Advantage | Reported Scale / Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENKIE (ENzyme KInetics Estimator) [23] | Prediction of (Km) & (k{cat}) for uncharacterized enzymes. | Bayesian Multilevel Models (BMMs) with hierarchical priors on enzyme classes. | Provides calibrated uncertainty estimates for predictions; uses only widely available identifiers (EC, MetaNetX). | Database prediction (BRENDA, SABIO-RK); genome-scale prior construction. |

| Linlog Kinetics with Bayesian Inference [25] | Inference of in vivo kinetic parameters from multi-omics data (fluxes, metabolomics, proteomics). | Linear-logarithmic kinetics enable efficient sampling of posterior elasticity parameter distributions via MCMC. | Scales to genome-sized metabolic models with thousands of data points; identifies flux control coefficients. | Genome-scale model of yeast metabolism integrated with multi-omics datasets [25]. |

| Bayesian Framework for SIRM Data [26] | Non-steady-state kinetic modeling of Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM) data. | ODE-based kinetic models with adaptive MCMC sampling (delayed rejection, adaptive Metropolis). | Robust parameter estimation from limited replicates; enables rigorous hypothesis testing between experimental groups via credible intervals. | Characterization of purine synthesis dysregulation in lung cancer tissues [26]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bayesian Prediction of Kinetic Parameters Using Database Priors (ENKIE Workflow)

This protocol details the use of Bayesian Multilevel Models to predict unknown parameters and their credible intervals by leveraging hierarchical structure in public databases [23].

1. Input Preparation & Standardization

- Objective: Standardize diverse biological identifiers for model input.

- Steps:

- Compile a list of target enzymatic reactions. For each, gather:

- Reaction stoichiometry.

- Metabolite identifiers (e.g., ChEBI, KEGG Compound).

- Enzyme Commission (EC) number.

- Protein identifier (Uniprot ID), if known.

- Submit identifiers to MetaNetX for mapping and standardization to a consistent namespace [23].

- (Optional) Use eQuilibrator via the ENKIE API to obtain standard Gibbs free energy changes for reactions to enable thermodynamic balancing [23].

- Compile a list of target enzymatic reactions. For each, gather:

- Output: A standardized table of reactions ready for prediction.

2. Model Query & Execution via ENKIE

- Objective: Generate posterior distributions for (Km) and (k{cat}).

- Steps:

- Install the

enkiePython package (pip install enkie). - In a Python script, load the standardized reaction table.

- Call the

enkie.predict()function, passing the table and specifying the desired parameters (km,kcat). - The tool internally uses the

brmsR package viarpy2to execute the pre-trained BMMs [23]. The models apply nested group-level effects (e.g., substrate → EC-reaction pair → protein family) to compute a posterior distribution for each query.

- Install the

- Output: For each reaction and parameter, a predicted (log-normal) distribution, summarized by its mean (or median) and standard deviation.

3. Interpretation & Downstream Application

- Objective: Extract credible intervals and apply predictions.

- Steps:

- For each parameter, calculate the 95% credible interval from the posterior sample (e.g., 2.5th to 97.5th percentile).

- Interpretation: There is a 95% probability the true parameter value lies within this interval, given the model and database prior.

- For metabolic modeling, sample multiple parameter sets from the joint posterior distributions to propagate uncertainty into network simulations [23].

- Critical Reporting: Document the predicted mean, standard deviation, and credible interval. Note the sources of the hierarchical prior (e.g., "prediction based on enzyme class EC 1.1.1.1") [27].

ENKIE Predictive Workflow for Kinetic Parameters

Protocol 2: Bayesian Inference of Kinetic Parameters from Experimental Data

This protocol outlines the process of estimating parameters and credible intervals from novel experimental data, such as reaction rates or multi-omics profiles [25] [26].

1. Experimental Design & Data Collection

- Objective: Generate data informative for parameter estimation.

- Steps:

- System Perturbation: Design experiments that perturb the system (e.g., vary substrate concentrations, inhibit enzymes, alter gene expression levels).

- Measured Outputs: Collect corresponding response data. This can be:

- Replication: Include biological and technical replicates to estimate measurement error variance, a critical component for the likelihood function.

2. Model & Prior Specification

- Objective: Define the mathematical and statistical model.

- Steps:

- Kinetic Model: Formulate the governing equations (e.g., Michaelis-Menten ODEs, linlog rate laws) [25] [26].

- Likelihood: Define the probability of observing the data given the parameters. Assume a normal distribution for log-transformed data is often appropriate [26].

- Prior Distribution Elicitation:

- Use informative priors from literature or database predictions (see Protocol 1) to constrain plausible values [23] [24].

- For variance parameters ((\sigma^2)), use weakly informative or shrinkage priors (e.g., half-Cauchy) to stabilize estimation with limited replicates [26].

- Justify all prior choices, as per Bayesian Analysis Reporting Guidelines (BARG) [27].

3. Posterior Sampling & Diagnostics

- Objective: Obtain the posterior distribution of parameters.

- Steps:

- Implement the model in a probabilistic programming framework (e.g., PyMC3, Stan).

- Use advanced Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) samplers, such as the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) or the Component-wise Adaptive Metropolis with Delayed Rejection algorithm for high-dimensional problems [25] [26].

- Run multiple, independent MCMC chains.

- Convergence Diagnostics: Verify chains have converged by ensuring the potential scale reduction factor (\hat{R} \leq 1.01) for all parameters and examining trace plots [23] [27].

- Effective Sample Size (ESS): Confirm ESS is sufficiently large (e.g., >400) for reliable estimates of posterior summaries [27].

4. Analysis & Reporting of Posterior Distributions

- Objective: Interpret parameters and their uncertainty.

- Steps:

- For each parameter, compute the posterior median (or mean) and the 95% Highest Density Credible Interval (HDPI), which is the shortest interval containing 95% of the posterior probability.

- Hypothesis Testing: To compare parameters between groups (e.g., wild-type vs. mutant), directly compute the posterior distribution of the difference ((\theta1 - \theta2)). If the 95% HDPI for this difference excludes 0, there is significant evidence for a difference [26].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Re-run inference with alternative, reasonable prior distributions to assess the robustness of conclusions [27].

- Full Reporting: Adhere to BARG [27]: report model specification, priors, software, convergence diagnostics, posterior summaries (with credible intervals), and results of sensitivity analyses.

Bayesian Inference Workflow from Experimental Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Bayesian Enzyme Kinetics

| Category | Item / Resource | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | ENKIE (Python package) [23] | Predicts (Km)/(k{cat}) and calibrated uncertainties using Bayesian Multilevel Models. Ideal for constructing informed priors. | Input requires standardized identifiers (via MetaNetX). Integrates with eQuilibrator for thermodynamics. |

| PyMC3 / Stan (Probabilistic Programming) [25] | Flexible frameworks for specifying custom Bayesian models (kinetic ODEs, likelihoods, priors) and performing MCMC inference. | Steeper learning curve. Requires explicit model formulation. | |

| brms (R package) [23] | Efficiently fits advanced Bayesian (multilevel) regression models. Used as the engine within ENKIE. | Accessible via R or Python (rpy2). Excellent for generalized linear modeling contexts. |

|

| Data & Knowledge Bases | BRENDA & SABIO-RK [23] [1] | Primary source databases for experimental enzyme kinetic parameters. Used for training predictive models and literature reference. | Data heterogeneity is high; quality and experimental conditions vary widely. |

| MetaNetX [23] | Platform for reconciling biochemical network data, standardizing metabolite and reaction identifiers across namespaces. | Critical pre-processing step for ensuring clean input to tools like ENKIE. | |

| STRENDA Guidelines [1] | Reporting standards for enzymology data. Journals requiring STRENDA compliance provide more reliable, reproducible data for priors. | Prioritize data from STRENDA-compliant studies when building priors. | |

| Methodological Standards | Bayesian Analysis Reporting Guidelines (BARG) [27] | A comprehensive checklist for transparent and reproducible reporting of Bayesian analyses. | Adherence is critical for publication and scientific integrity. Covers priors, diagnostics, sensitivity. |

| Experimental Design | Stable Isotope Tracers (e.g., ¹³C₆-Glucose) [26] | Enables Stable Isotope Resolved Metabolomics (SIRM) to trace pathway fluxes and isotopomer dynamics for rich, time-course data. | Essential for fitting complex, non-steady-state kinetic models and inferring in vivo fluxes. |

| Controlled Perturbation Set | A suite of genetic (ko, overexpression) or environmental (substrate titration, inhibitors) perturbations. | Generates the multi-condition data necessary to constrain parameters in genome-scale models [25]. |

From Data to Distribution: A Bayesian Workflow for Enzyme Kinetics

Bayesian Experimental Design (BED) provides a foundational, principled framework for maximizing the informational yield of each experiment, a critical advantage in resource-intensive fields like enzyme kinetics and drug development. By treating unknown parameters as probability distributions and using metrics like the Expected Information Gain (EIG), BED algorithms sequentially identify the most informative experimental conditions to perform next [28] [29]. This approach is particularly powerful for estimating precise Michaelis-Menten parameters (𝑘𝑐𝑎𝑡, 𝐾𝑀) from limited data, directly supporting robust Bayesian parameter estimation. Contemporary advances, including amortized design policies and hybrid machine-learning frameworks, are transitioning BED from a theoretical tool to a practical component of the experimental workflow, enabling real-time, adaptive decision-making that dramatically accelerates research cycles [6] [30] [31].

Within the broader thesis on Bayesian parameter estimation for enzyme kinetics, BED constitutes the essential first step for intelligent, efficient data collection. Traditional enzyme characterization methods, such as initial rate measurements across substrate concentrations, often rely on predetermined, static grids. These methods can be woefully inefficient, potentially missing informative regions of the experimental space or wasting replicates on uninformative conditions [32]. In contrast, BED formulates experiment selection as an optimization problem, where the goal is to choose conditions (e.g., substrate concentration, pH, temperature, flow rate) that maximize the reduction in uncertainty about the kinetic parameters of interest [10]. This is inherently aligned with the Bayesian philosophy, where prior knowledge (from literature or earlier experiments) is updated with new data to form a posterior distribution. BED simply ensures that the new data collected is optimally valuable for this updating process. For drug development professionals, this translates to faster, more reliable characterization of enzyme targets and inhibitors, reducing the time and material cost of early-stage research [33].

Theoretical and Computational Framework

Bayesian Optimal Experimental Design (BOED) formalizes the search for the most informative experiment. For a proposed experimental design d and anticipated data y, the utility is typically the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the posterior p(θ|y,d) and prior p(θ) distributions of parameters θ. This divergence measures the information gain. The optimal design d* is found by maximizing the Expected Information Gain (EIG) over all possible designs [28] [29]: d∗ = argmax d E{y|d} [ D_KL ( p(θ|y,d) || p(θ) ) ]* This computation is notoriously challenging, as it involves nested integration over the parameter and data spaces. Recent methodological breakthroughs have focused on making this tractable for complex, high-dimensional problems common in systems biology. Key comparative approaches are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Bayesian Experimental Design Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Ideal Use Case in Enzyme Kinetics | Computational Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Sequential BOED [28] [29] | Direct, step-wise maximization of EIG. | Principled, theoretically optimal. | Low-dimensional designs (e.g., varying [S] and [I]). | Computationally expensive per step; not real-time. |

| Amortized Design (e.g., DAD) [31] | Train a neural network (design policy) offline to predict optimal designs. | Ultra-fast (<1s) online decision-making. | High-throughput screening; real-time flow reactor control. | High upfront training cost; less flexible to new priors. |

| Semi-Amortized Design (e.g., Step-DAD) [30] | Combines a pre-trained policy with periodic online updates. | Balances speed with adaptability and robustness. | Long, costly experimental campaigns with shifting dynamics. | Moderate online computation for policy refinement. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [32] [34] [33] | Uses a Gaussian Process surrogate to optimize a performance objective (e.g., product yield). | Excellent for black-box optimization; handles noise well. | Optimizing enzyme expression or multi-enzyme pathway output. | Focuses on performance, not direct parameter uncertainty reduction. |

| Hybrid ML-Bayesian Inversion [6] | Deep neural network predicts system behavior, integrated with Bayesian inference. | Handles complex, high-dimensional data (e.g., from biosensors). | Interpreting real-time sensor data (GFET, spectroscopy) for kinetics. | Requires large training dataset; integrates sensing & inference. |

The selection of a BED method depends on the experimental context. For foundational parameter estimation, sequential or semi-amortized BOED is most direct [30] [10]. For upstream process development like media optimization, Bayesian Optimization has proven highly effective [33].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The following protocols illustrate the implementation of BED for enzyme kinetics in different experimental setups.

Protocol 1: GFET-Based Enzyme Characterization with Hybrid ML-Bayesian Inference

This protocol details the use of Graphene Field-Effect Transistors (GFETs) for sensitive detection combined with a Bayesian inversion framework to estimate kinetic parameters, as demonstrated for horseradish peroxidase (HRP) [6].

Research Objective: To determine the Michaelis-Menten parameters (𝑘𝑐𝑎𝑡, 𝐾𝑀) for a peroxidase enzyme via real-time electrical monitoring of its reaction.

Key Reagents & Equipment:

- GFET Biosensor: Functionalized for target enzyme or reaction product binding.

- Enzyme Solution: Purified enzyme (e.g., HRP) at known concentration.

- Substrate Solution: Varying concentrations of target substrate (e.g., H₂O₂ for HRP) in appropriate buffer.

- Data Acquisition System: For continuous monitoring of GFET drain current (Ids) vs. gate voltage (Vgs) shifts.

- Microfluidic Flow Cell (Optional): For controlled reagent delivery.

Experimental Workflow:

- Prior Definition: Define prior distributions for log(𝑘𝑐𝑎𝑡) and log(𝐾𝑀) based on literature or related enzymes. Use broad, uninformative priors (e.g., LogNormal(μ, σ)) if no prior knowledge exists.

- Initial Design & Experiment:

- The BED algorithm selects the first substrate concentration [S]₁ predicted to maximize EIG.

- Inject the chosen [S]₁ into the GFET chamber containing the enzyme and record the time-dependent electrical response.

- Process the raw Ids/Vgs data to extract a reaction rate (e.g., initial rate of signal change), denoted as v_exp₁.

- Bayesian Update:

- Construct a likelihood function linking the kinetic parameters to the predicted rate. For example: vpred([S]ᵢ, 𝑘𝑐𝑎𝑡, 𝐾𝑀) = (𝑘𝑐𝑎𝑡 * [E] * [S]ᵢ) / (𝐾𝑀 + [S]ᵢ).

- Assume observational noise: vexpᵢ ~ Normal(vpred, σ), where σ is also estimated.

- Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling (e.g., with PyMC3/4) to update the joint posterior distribution of (𝑘𝑐𝑎𝑡, 𝐾𝑀, σ) given the new data point ([S]₁, vexp₁) [10].

- Iterative Loop:

- Use the current posterior as the new prior for the next design step.

- The BED algorithm selects the next optimal [S]₂ based on all accumulated data.

- Repeat steps 2-4 until the posterior distributions are sufficiently precise (e.g., coefficient of variation < 10%) or the experimental budget is exhausted.

- Validation: Compare final parameter estimates and uncertainties with values obtained from traditional, dense grid experiments.

Protocol 2: Kinetic Estimation in a Flow Reactor with Compartmentalized Enzymes

This protocol adapts BED for steady-state kinetic analysis of enzymes immobilized in hydrogel beads within a Continuously Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR) [10].

Research Objective: To infer kinetic parameters and discriminate between rival reaction mechanisms for an enzyme compartmentalized in a flow system.

Key Reagents & Equipment:

- Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Beads (PEBs): Containing immobilized enzyme, synthesized via microfluidic droplet generation [10].

- CSTR System: Equipped with inlet pumps, stirring, and a membrane to retain beads.

- Precision Syringe Pumps: For controlled substrate inflow.

- Online Detector: UV-Vis spectrophotometer or HPLC for measuring product concentration in the outflow.

Experimental Workflow:

- System Modeling: Define the ODE model for the CSTR, incorporating Michaelis-Menten kinetics and flow terms: d[S]/dt = 𝑘_𝑓([S]_in − [S]) − (V_max [S])/(𝐾𝑀 + [S]), where 𝑘_𝑓 is the flow rate constant [10].

- Prior & Design Space: Define priors for 𝑘𝑐𝑎𝑡, 𝐾𝑀, and observational noise σ. The design space d = ([S]in, 𝑘𝑓) consists of the substrate inlet concentration and the flow rate.

- Sequential BED Execution:

- For the current posterior, calculate the EIG for many candidate pairs ([S]in, 𝑘𝑓).

- Select and run the experiment with the highest EIG. Allow the system to reach steady state.

- Measure the steady-state product concentration [P]ss.

- Update the posterior using Bayes' theorem. The likelihood is based on the difference between observed and model-predicted [P]ss.

- Model Discrimination: To select between mechanisms (e.g., Michaelis-Menten vs. models with inhibition), calculate the Bayes Factor by comparing the marginal likelihoods (evidence) of the data under each model, using the sequentially collected data.

Protocol 3: Implementing an Adaptive Design Policy with Step-DAD

This protocol outlines the application of a state-of-the-art semi-amortized BED method for adaptive experimentation [30].

Research Objective: To conduct a resource-efficient experimental campaign for characterizing a novel enzyme using an adaptive policy that learns from ongoing results.

Key Components:

- Experimental Setup: Any standard kinetic assay platform (e.g., plate reader, quenched-flow apparatus).

- Computational Environment: Python with libraries for deep learning (PyTorch/TensorFlow) and probabilistic programming (Pyro, PyMC).

Implementation Workflow:

- Policy Pre-Training (Amortization Phase):

- Simulate a wide range of possible enzyme kinetics parameters from the prior.

- For each simulated "virtual enzyme," run a full, simulated sequential BED process.

- Train a neural network (the design policy) to map historical experimental data to the next optimal design. This is a costly one-time computation.

- Live Experimentation with Online Adaptation:

- Initialize the real experiment with the pre-trained policy and a small batch of random initial designs.

- For each subsequent experimental step: The policy network takes the history of conditions and results as input and, in milliseconds, outputs the recommended next design [31].

- Run the wet-lab experiment with this design and record the outcome.

- Periodically (e.g., every 5-10 experiments), perform a policy update: refine the neural network weights using the data collected so far in the actual campaign, adapting the policy to the specific enzyme under study [30].

- Termination: Proceed until parameter precision targets are met. The final posterior distribution provides the kinetic parameter estimates with full uncertainty quantification.

Diagram 1: General Workflow of Sequential Bayesian Experimental Design (Max Width: 760px)

Diagram 2: Step-DAD Semi-Amortized BED Workflow [30] (Max Width: 760px)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BED in Enzyme Kinetics

| Category | Item / Reagent | Primary Function in BED Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosensing & Detection | Functionalized GFET Chips [6] | Transduces enzymatic reaction events into quantifiable electrical signals for real-time, data-rich monitoring. | Surface chemistry must be tailored for specific enzyme-product binding. Enables continuous data streams ideal for sequential design. |

| Enzyme Immobilization | Polyacrylamide Hydrogel Beads (PEBs) [10] | Encapsulates enzymes, enabling their use in flow reactors (CSTRs) for steady-state studies and reuse across multiple design points. | Polymerization conditions (e.g., use of AAH-Suc linker) must preserve enzyme activity. Bead monodispersity ensures reproducible kinetics [10]. |

| Precision Fluidics | Cetoni neMESYS Syringe Pumps [10] | Provides precise, programmable control of substrate inflow rates (a key design variable 𝑘_𝑓) in flow reactor experiments. | High precision is critical for accurate implementation of the designed experimental condition. |

| Assay & Analytics | Avantes Fiber Optic Spectrometer [10] | Enables online, real-time measurement of product concentration (e.g., via NADH absorbance) for immediate data feedback. | Essential for closing the BED loop quickly; offline HPLC analysis introduces delay [10]. |

| Computational Core | BioKernel Software / Custom PyMC3/4 Scripts [10] [34] | BioKernel: Provides a no-code interface for Bayesian Optimization of biological outputs. PyMC3/4: Industry-standard probabilistic programming for custom MCMC sampling and posterior analysis. | Choice depends on goal: BioKernel for performance optimization [34], custom scripts for direct parameter estimation and BED [10]. |

Integrating Bayesian Experimental Design as the first step in a parameter estimation thesis fundamentally transforms the data collection paradigm in enzyme kinetics. Moving from static, guesswork-based designs to dynamic, information-theoretic optimization confers a decisive efficiency advantage, often requiring 3-30 times fewer experiments to achieve precise estimates compared to traditional Design of Experiments [33]. As demonstrated, BED is versatile, applicable from foundational parameter estimation using GFETs or flow reactors to applied strain and media optimization [6] [10] [33]. The ongoing development of amortized and semi-amortized methods like DAD and Step-DAD is solving the critical challenge of computational speed, making adaptive, real-time experimental guidance a practical reality for the laboratory [30] [31]. For researchers and drug developers, mastering BED is no longer a niche computational skill but a core competency for conducting rigorous, resource-efficient, and accelerated science in the face of complex biological uncertainty.

Foundational Mechanistic Models in Enzyme Kinetics

The accurate definition of a mechanistic model is the critical first step in Bayesian parameter estimation. This model mathematically encodes the hypothesized biochemical process, serving as the function through which parameters are related to observable data. For most enzymatic reactions, the Michaelis-Menten model provides the foundational framework, describing the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity at steady state [10].

The classic Michaelis-Menten equation for a single-substrate, irreversible reaction is:

v = (V_max * [S]) / (K_M + [S])

where v is the reaction velocity, V_max is the maximum velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, and K_M is the Michaelis constant, equal to the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity [35].

In the context of flow reactor experiments—a common setup for generating data for Bayesian analysis—this model is extended with mass balance terms to account for continuous inflow and outflow. The resulting system of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) for a substrate S and product P is [10]:

Here, k_f is the flow constant and [S]_in is the inflowing substrate concentration, both considered known control parameters θ. The kinetic parameters to be estimated are ϕ = {k_cat, K_M}, where V_max = k_cat * [E]_total [10].

For more complex scenarios, other mechanistic models may be required. The delayed Chick-Watson model, for instance, is used in disinfection kinetics to account for a lag phase (shoulder) followed by first-order inactivation. It is defined as [36]:

where N/N_0 is the survival ratio, CT is the disinfectant concentration multiplied by contact time, CT_lag is the lag phase duration, and k is the first-order inactivation rate constant.

Table 1: Core Kinetic Parameters of Mechanistic Models

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover Number | k_cat | Maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time. | s⁻¹ |

| Michaelis Constant | K_M | Substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of V_max. A measure of enzyme-substrate affinity. | M (mol/L) |

| Inhibition Constant | K_i | Dissociation constant for an enzyme-inhibitor complex. | M (mol/L) |

| Maximum Velocity | V_max | Maximum achievable reaction rate (kcat * [E]total). | M/s |

| Lag Phase Parameter | CT_lag | Critical exposure (Concentration * Time) before first-order inactivation begins. | mg·min/L |

Bayesian Mathematical Framework and Prior Formulation

Bayesian statistics provides a coherent probabilistic framework for updating beliefs about unknown parameters (ϕ) in light of experimental data (y). The core theorem is expressed as [10]:

P(ϕ | y) ∝ P(y | ϕ) * P(ϕ)

- Posterior (

P(ϕ | y)): The probability distribution of the parameters given the observed data. This is the final output of the analysis, representing updated knowledge. - Likelihood (

P(y | ϕ)): The probability of observing the data given a specific set of parameters. It encodes the mechanistic model and measurement noise. - Prior (

P(ϕ)): The probability distribution representing belief about the parameters before observing the new data. It incorporates previous knowledge from literature or pilot experiments.

Constructing the Likelihood Function

The likelihood function links the mechanistic model to the data. Assuming experimental measurements of product concentration [P]_obs are normally distributed around the model-predicted steady-state value [P]_ss with an unknown standard deviation σ, the likelihood for a single data point is [10]:

P([P]_obs | ϕ, θ) = N([P]_ss, σ), where [P]_ss = g(ϕ, θ) is the solution to the steady-state ODEs.

For n independent data points, the total likelihood is the product of individual probabilities. The standard deviation σ is often treated as an additional nuisance parameter to be estimated simultaneously with the kinetic parameters, thereby quantifying experimental uncertainty [10].

Defining Informative Prior Distributions

The choice of prior is a critical step that regularizes the inference and incorporates existing knowledge. Prior selection should be justified based on the parameter's physical and biochemical properties.

- k_cat (Turnover Number): As a positive rate constant, it is typically modeled with a log-Normal or Gamma distribution. The prior's scale can be informed by the known range for similar enzyme classes (e.g., 0.1 - 10³ s⁻¹) [35].

- KM (Michaelis Constant): Also a positive quantity. A log-Normal prior is appropriate as KM values often span orders of magnitude across different enzyme-substrate pairs [35].

- Weakly Informative Priors: In the absence of specific knowledge, broad distributions like

Half-Normal(0, large_scale)orGamma(α=2, β=1/expected_value)can be used to constrain parameters to plausible physiological ranges while letting the data dominate. - Informed Priors from Literature: Data from resources like BRENDA or previous studies can be used to construct a prior. For example, if literature suggests a K_M of 1.0 ± 0.5 mM, a Normal(mean=1.0, sd=0.5) prior truncated at zero could be used [35].

Table 2: Common Prior Distributions for Kinetic Parameters

| Parameter | Recommended Prior Distribution | Justification & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| k_cat | LogNormal(ln(μ), σ) or Gamma(α, β) | Positive, right-skewed values spanning orders of magnitude. |

| K_M | LogNormal(ln(μ), σ) | Positive, right-skewed; substrate affinity varies widely. |

| K_i | LogNormal(ln(μ), σ) | Positive; similar justification to K_M. |

| CT_lag (Lag Phase) | Gamma(α, β) or Uniform(min, max) | Positive duration; bounds often known from experimental design. |

| Measurement Noise (σ) | Half-Normal(0, S) or Exponential(λ) | Standard deviation must be positive; scale S based on instrument precision. |

Computational Implementation Protocol

Workflow for Bayesian Parameter Estimation

The following protocol outlines the steps for implementing Bayesian inference for enzyme kinetics, from model definition to posterior analysis [10] [36].

Software Requirements: Python (with PyMC3, PyMC4, or TensorFlow Probability) or Stan/BUGS. A Jupyter or Colab notebook environment is recommended for interactive analysis [10].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Define the Mechanistic ODE Model: Code the system of differential equations (e.g., Michaelis-Menten with flow terms) as a callable function.

- Solve for Steady States: For steady-state data, calculate

[P]_ssby either:- Analytically solving

d[P]/dt = 0. - Using numerical root-finding (e.g., SciPy's

fsolve) for more complex models.

- Analytically solving

- Construct the Probabilistic Model:

- Specify prior distributions for all unknown parameters (

k_cat,K_M,σ). - Define the deterministic variable

[P]_ssusing the steady-state solution and the current parameter values. - Specify the likelihood function, linking

[P]_ssto the observed data (e.g.,Normal([P]_ss, σ)).

- Specify prior distributions for all unknown parameters (

- Sample from the Posterior: Use a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampler like the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS). Run multiple chains (e.g., 4) with a sufficient number of draws (e.g., 5000) and tune steps (e.g., 1000) [10].

- Diagnose Convergence: Check MCMC diagnostics:

- Trace Plots: Visualize chains; they should resemble "fuzzy caterpillars."

- Gelman-Rubin Statistic (R-hat): Values should be < 1.01 for all parameters.

- Effective Sample Size (ESS): Should be > 400 per chain to ensure reliable statistics.

- Analyze and Report Posteriors:

- Plot marginal posterior distributions (histograms or kernel density estimates).

- Report posterior summaries: median or mean, and 94% Highest Density Interval (HDI) as the credible interval.

- Perform posterior predictive checks: simulate new data using sampled parameters and compare visually to actual data.

Bayesian Inference Workflow for Enzyme Kinetics

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation

High-quality, reproducible experimental data is essential for reliable Bayesian inference. Below are detailed protocols for generating kinetic data using immobilized enzyme systems and flow reactors, as referenced in recent literature [10].

Protocol A: Production of Polyacrylamide-Enzyme Beads (PEBs)

This protocol describes enzyme immobilization via encapsulation in hydrogel beads, useful for creating stable, reusable biocatalysts for continuous flow experiments [10].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Enzyme of interest: Purified enzyme in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate, HEPES).

- 6-acrylaminohexanoic acid succinate (AAH-Suc) linker: For enzyme functionalization.

- NHS/EDC coupling reagents: For activating carboxyl groups.

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide solution (40%, 19:1): Monomer stock for hydrogel formation.

- Photoinitiator (e.g., 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone): For UV-induced polymerization.

- Mineral oil with surfactant (e.g., 2% Span 80): Continuous phase for droplet generation.

- Droplet-based microfluidic device: For generating monodisperse water-in-oil emulsions.

- UV curing lamp (365 nm): For polymerizing droplets into solid beads.

Procedure:

- Enzyme Functionalization: Conjugate the enzyme with the AAH-Suc linker via NHS chemistry targeting lysine amine groups. Purify the functionalized enzyme via desalting column [10].

- Prepare Aqueous Monomer Phase: Mix the functionalized enzyme, acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, and photoinitiator in an aqueous buffer to final concentrations of ~10-20% total monomer.

- Generate Droplets: Load the aqueous phase and the surfactant-containing oil phase into syringes. Pump them through a microfluidic droplet generator (flow-focusing geometry) to create monodisperse water-in-oil droplets (~50-200 μm diameter) [10].

- UV Polymerization: Collect droplets in a UV-transparent tube. Expose to 365 nm UV light for 1-5 minutes to initiate free-radical polymerization, forming solid hydrogel beads.

- Washing and Storage: Break the emulsion by adding a destabilizing solvent (e.g., perfluoro-octanol). Wash beads thoroughly with buffer and store at 4°C.

Protocol B: Flow Reactor Experiment for Steady-State Kinetics

This protocol outlines the operation of a Continuously Stirred Tank Reactor (CSTR) containing immobilized enzymes to generate steady-state product formation data across a range of substrate inflows [10].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Polyacrylamide-Enzyme Beads (PEBs): From Protocol A.

- Substrate stock solutions: Prepared in reaction buffer at varying concentrations.

- CSTR vessel: A temperature-controlled, magnetically stirred reactor chamber.

- Syringe pumps (low-pressure, high-precision): For controlled inflow of substrate and buffer.

- Polycarbonate membrane (5 μm pore size): Seals reactor outlets to retain beads.

- Online spectrophotometer or fraction collector: For real-time or offline product quantification (e.g., measuring NADH at 340 nm).

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Load a known volume and enzyme activity of PEBs into the CSTR. Seal the outlet with the polycarbonate membrane. Equilibrate with reaction buffer at the desired temperature and flow rate [10].

- Experimental Run: Program the syringe pumps to switch the inflow from pure buffer to a substrate solution at concentration

[S]_in,1and a fixed flow ratek_f,1. Allow the system to reach steady state (typically 3-5 residence times). - Data Collection: At steady state, record the product concentration