High-Throughput Screening for Enzyme Activity: Modern Strategies for Accelerated Discovery and Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies for enzyme activity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

High-Throughput Screening for Enzyme Activity: Modern Strategies for Accelerated Discovery and Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies for enzyme activity, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of enzyme HTS, detailing advanced assay technologies and their critical applications in enzyme discovery, engineering, and drug development. The content further covers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing screening campaigns, and concludes with rigorous validation frameworks to ensure data reliability and relevance. By integrating the latest advances in automation, computational biology, and miniaturization, this guide serves as a strategic resource for leveraging HTS to develop novel biocatalysts and therapeutics efficiently.

The Fundamentals of High-Throughput Enzyme Screening: Principles and Core Concepts

Defining High-Throughput Screening in an Enzymology Context

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a foundational methodology in modern enzymology, enabling the rapid experimental evaluation of thousands to millions of biochemical samples to identify enzymes with desired functional properties. Within enzyme research, HTS bridges the gap between genomic sequence information and functional characterization by providing quantitative data on enzyme activity, specificity, and stability across diverse variant libraries [1]. The power of HTS lies in its integration of miniaturized assays, automated liquid handling, and sensitive detection systems that together accelerate the pace of enzyme discovery and engineering.

The application of HTS in enzymology has become increasingly crucial with the growing interest in directed evolution and functional genomics. Directed evolution experiments generate diverse mutant libraries that require efficient screening to identify improved variants [2], while functional genomics seeks to understand the relationship between protein sequence and function across entire enzyme families [1]. In both contexts, HTS provides the methodological framework for obtaining the quantitative ground truth data necessary to build predictive models of enzyme function and to advance our fundamental understanding of catalytic mechanisms [1].

Key Concepts and Quantitative Metrics in HTS

Defining HTS Quality Parameters

The reliability of any HTS campaign depends on rigorous quality control metrics that ensure consistent and reproducible results. The statistical assessment of HTS quality involves several key parameters that determine the suitability of a protocol for screening applications:

- Z'-factor: This metric represents the robustness of an HTS assay, accounting for both the dynamic range of the signal and the data variation associated with both positive and negative controls. A Z'-factor value ≥ 0.5 is generally indicative of an excellent assay suitable for HTS applications, while values between 0.5 and 0 indicate a marginal or weak assay [2].

- Signal Window (SW) and Assay Variability Ratio (AVR): These complementary metrics further characterize assay performance by measuring the separation between control populations and the variance within the assay system [2].

The table below summarizes the target values for these critical HTS quality metrics, providing a benchmark for assay development and validation:

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Assessing HTS Assay Quality

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Target Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-factor | 1 - (3σpositive + 3σnegative) / |μpositive - μnegative| | ≥ 0.5 | Excellent assay separation |

| Signal Window (SW) | (μpositive - μnegative) / (σpositive + σnegative) | ≥ 2 | Sufficient signal detection window |

| Assay Variability Ratio (AVR) | (σpositive + σnegative) / (μpositive - μnegative) | ≤ 1 | Acceptable assay variability |

Comparison of HTS Approaches in Enzymology

HTS methodologies in enzymology can be broadly categorized based on their operational throughput, detection principles, and specific applications. The selection of an appropriate HTS format depends on the enzyme class being studied, the available instrumentation, and the specific research objectives.

Table 2: Comparison of HTS Methodologies in Enzymology

| HTS Method | Throughput Range | Key Detection Principle | Typical Application | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microplate-Based Colorimetric | 96 to 1536 wells per run | Color change measured by absorbance [2] | Isomerase activity, hydrolase screens | Simplicity, cost-effectiveness, easy adaptation |

| Fluorescence-Based | 384 to 1536 wells per run | Fluorescence intensity change [3] | Kinase assays, protease screens, inhibitor studies | High sensitivity, suitable for low enzyme concentrations |

| Microfluidic Kinetics (HT-MEK) | ~1500 variants in parallel | Various detection methods integrated [1] | Deep mutational scanning, mechanistic studies | Direct kinetic measurements, minimal reagent use |

| Functional Proteomics | 100s of proteins simultaneously | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry [4] [5] | Comparative secretome analysis, native pathway discovery | Direct product identification, multiplexing capability |

Established HTS Protocols in Enzymology

Protocol 1: Colorimetric HTS for Isomerase Activity

This protocol establishes a robust method for screening isomerase variants, specifically optimized for L-rhamnose isomerase (L-RI) activity, which catalyzes the isomerization of D-allulose to D-allose [2].

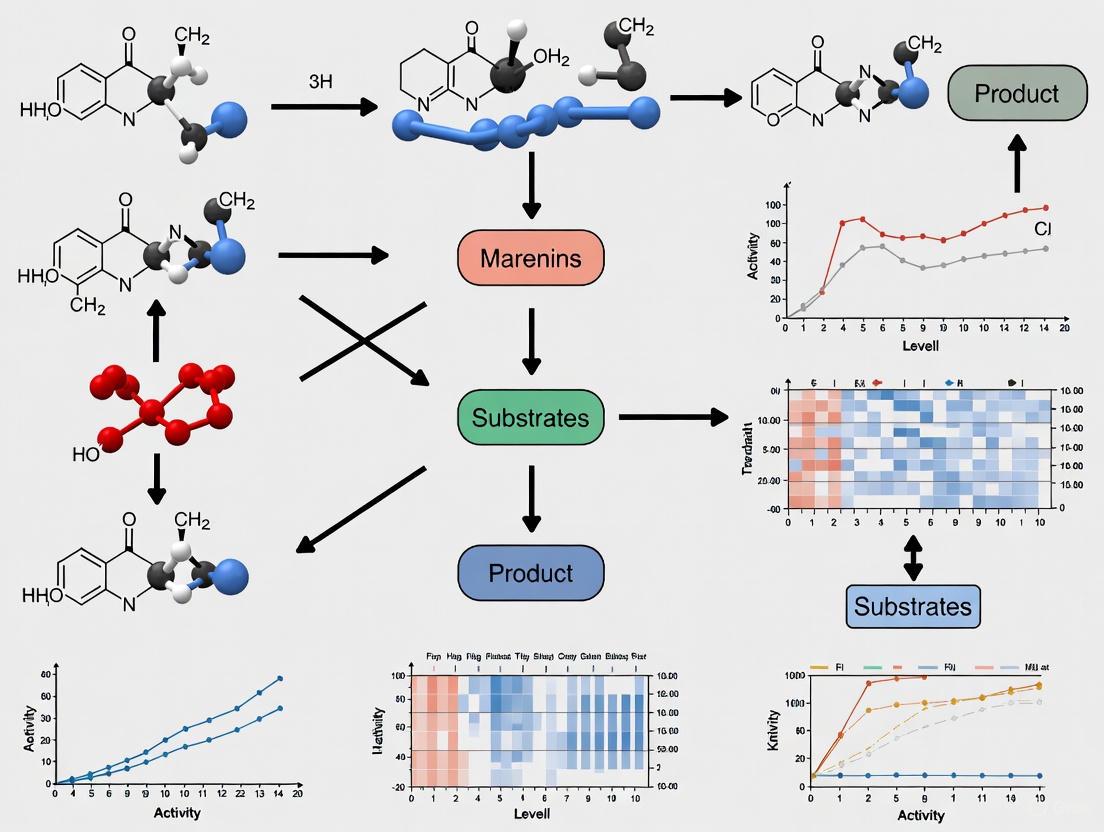

The following diagram illustrates the optimized workflow for colorimetric HTS of isomerase activity in a 96-well plate format:

Step-by-Step Procedure

Protein Expression and Preparation:

- Express isomerase variants in a suitable host system (e.g., E. coli).

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and remove supernatant.

- Implement filtration or purification steps to remove denatured enzymes and reduce assay interference [2].

Microplate Assay Setup:

- Dispense 50-100 μL of each enzyme variant into individual wells of a 96-well plate.

- Add D-allulose substrate to initiate the isomerization reaction.

- Include appropriate positive (wild-type enzyme) and negative (heat-inactivated enzyme) controls in each plate.

Reaction Incubation:

- Incubate the plate at optimal temperature for the specific isomerase (e.g., 37°C for L-RI from Geobacillus sp.) for a defined period to allow partial substrate conversion.

Colorimetric Detection:

- Stop the reaction by adding Seliwanoff's reagent (containing resorcinol in hydrochloric acid).

- Incubate at elevated temperature (70-80°C) to develop color.

- Measure absorbance at appropriate wavelength (typically 480-540 nm) using a plate reader.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate enzyme activity based on D-allulose depletion, quantified by reduced color development compared to controls.

- Validate assay quality by calculating Z'-factor using positive and negative control data [2].

Critical Reagents and Optimization Notes

- Seliwanoff's Reagent: Must be prepared fresh or stored appropriately to maintain stability.

- D-allulose Substrate: Concentration should be optimized around the Km value to ensure linear reaction kinetics.

- Interference Minimization: Cell debris and denatured proteins can cause light scattering; clarification steps are crucial.

- Validation: Correlate results with standard analytical methods like HPLC to verify accuracy [2].

Protocol 2: Fluorescence-Based HTS for Deacetylase Inhibitors

This protocol describes a fluorescence-based approach for identifying inhibitors of Sirtuin 7 (SIRT7), employing fluorescently-labeled peptide substrates to measure enzymatic activity [3].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps for fluorescence-based HTS of SIRT7 inhibitors:

Step-by-Step Procedure

Enzyme Preparation:

- Purify recombinant His-tagged SIRT7 from E. coli using affinity chromatography.

- Determine protein concentration and aliquot for single-use to maintain enzyme stability.

Compound Library Preparation:

- Dispense test compounds into 384-well microplates using automated liquid handling systems.

- Include DMSO controls and reference inhibitors for assay validation.

Reaction Assembly:

- Prepare master mix containing SIRT7 enzyme, fluorescent peptide substrate, and NAD+ cofactor.

- Dispense reaction mixture into compound plates to initiate enzymatic reaction.

Reaction Incubation and Detection:

- Incubate plates at 37°C for a predetermined time to ensure linear reaction kinetics.

- Measure fluorescence using appropriate excitation/emission wavelengths for the specific fluorescent tag.

Data Analysis and Hit Validation:

- Calculate percentage inhibition relative to controls.

- Select primary hits for confirmatory dose-response studies to determine IC50 values [3].

Critical Parameters for Success

- Substrate Concentration: Should be near Km to maximize sensitivity to competitive inhibitors.

- DMSO Tolerance: Test enzyme sensitivity to DMSO concentration; keep consistent across wells (<1%).

- Signal Dynamic Range: Optimize reaction time to avoid signal saturation while maintaining sufficient window for inhibition detection.

- Counter-Screening: Include secondary assays to exclude fluorescent compounds that interfere with detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of HTS in enzymology requires careful selection of reagents and materials that ensure assay robustness and reproducibility. The following table catalogues essential solutions and their specific functions in typical HTS workflows:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Enzymology HTS

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in HTS | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seliwanoff's Reagent | Resorcinol in hydrochloric acid | Ketose-specific color development for isomerase detection | Detection of D-allulose depletion in L-RI screens [2] |

| Fluorescent Peptide Substrates | Target peptide sequence conjugated to fluorophore | Enzyme activity reporting through fluorescence change | SIRT7 deacetylase activity measurement [3] |

| His-tagged Enzyme Systems | Recombinant enzymes with polyhistidine tag | Facilitates uniform purification and immobilization | SIRT7 production and screening [3] |

| CAZyme Classification Reagents | Specific polysaccharide substrates | Functional characterization of carbohydrate-active enzymes | Profiling fungal secretomes on diverse biomass [4] |

| LC-MS Mobile Phases | Buffered acetonitrile/methanol gradients | Compound separation and identification in complex mixtures | Detecting multiple reaction products from Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases [5] |

Data Analysis and Validation Strategies

Hit Confirmation and Data Curation

The initial identification of "hits" in primary HTS represents only the first step in a rigorous validation workflow. Primary screens typically exhibit high false positive rates due to factors such as compound interference, assay artifacts, and non-specific binding [6]. Effective hit confirmation requires a hierarchical approach to data analysis:

- Primary Hit Selection: Apply statistical methods (z-score, SSMD, B-score) to identify compounds showing significant activity above background in the initial screen.

- Confirmatory Screening: Test primary hits in concentration-response experiments to establish dose-dependence and calculate potency values (IC50, EC50).

- Orthogonal Assays: Validate active compounds using alternative assay formats with different detection principles to exclude technology-specific artifacts.

- Counter-Screens: Evaluate compounds against related but distinct targets to assess specificity and exclude pan-assay interference compounds [6].

Advanced Applications: Integrating Proteomics and Computational Approaches

Beyond targeted enzyme screening, HTS methodologies enable comprehensive analysis of complex enzymatic systems through proteomic approaches. Quantitative comparison of fungal secretomes across different biomass substrates demonstrates how HTS data can reveal substrate-specific enzyme expression patterns and identify co-regulated proteins of unknown function [4].

The growing integration of computational approaches with HTS data is creating new opportunities for enzyme discovery and engineering. Machine learning analysis of LC-MS data from Fe(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase screens enables detection of both anticipated and unexpected reaction outcomes, facilitating the discovery of novel enzymatic functions [5]. These computational approaches become particularly valuable when screening enzymes that generate multiple products or exhibit complex reaction kinetics.

The Role of HTS in Building an Efficient Bioeconomy and Reducing Environmental Footprint

The transition towards a sustainable bioeconomy—defined as an economy that uses renewable biological resources to produce goods, energy, and services—is fundamental to addressing global challenges such as climate change and resource scarcity [7] [8]. In this context, High-Throughput Screening (HTS) emerges as a pivotal technology. HTS enables the rapid testing of thousands of compounds to identify those with desirable biological activities, drastically accelerating the discovery of novel enzymes and biocatalysts [9]. These biological tools are essential for developing more efficient industrial processes that rely on biomass instead of fossil-based resources, thereby reducing the environmental footprint of production systems [7]. By facilitating the discovery of highly efficient enzymes, HTS allows industrial biorefineries to operate with lower energy input, reduced reagent consumption, and improved yields, directly contributing to a more sustainable and circular economic model.

HTS-Driven Reduction of Environmental Footprints

The cultivation and processing of biomass is a significant driver of environmental pressure, responsible for over 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90% of global water stress impacts [7]. HTS technologies can mitigate these impacts by optimizing the biological engines behind biobased production.

Environmental Advantages of HTS-Optimized Processes

The primary link between HTS and a reduced environmental footprint lies in the efficiency of the biocatalysts it helps to discover. Enhanced enzyme efficiency translates directly into lower resource consumption during industrial operations. For instance, a high-sensitivity HTS assay can reduce enzyme consumption in a screening campaign by up to tenfold, conserving precious reagents and significantly lowering the cost and material footprint of research and development [10]. This principle extends to full-scale production, where superior enzymes can:

- Reduce energy inputs by operating effectively under milder temperature and pressure conditions.

- Increase product yields from a given quantity of biomass, enhancing the efficiency of the resource base.

- Minimize waste generation by enabling more complete conversion of feedstocks.

A key framework for monitoring these benefits is the use of environmental footprint indicators [7]. The table below summarizes how HTS-derived advancements contribute to improving these critical metrics.

Table 1: HTS Contributions to Key Bioeconomy Footprint Indicators

| Footprint Indicator | Impact of HTS-Optimized Enzymes |

|---|---|

| Agricultural Biomass Footprint | Enables higher-value products from the same biomass quantity; supports use of waste biomass. |

| Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions | Lowers energy consumption in industrial bioprocesses, reducing associated GHG emissions. |

| Agricultural Land Use | Increases efficiency of biomass conversion, potentially reducing land demand for a given output. |

| Water Scarcity Footprint | Could lead to processes with lower water requirements or less water pollution. |

Quantitative Impact of Assay Sensitivity

The environmental and economic efficacy of HTS itself is heavily dependent on assay sensitivity. A highly sensitive assay platform is a cornerstone of resource-efficient screening. The superior sensitivity of platforms like the Transcreener assay demonstrates this by directly reducing material requirements while improving data quality [10].

Table 2: Economic and Environmental Impact of HTS Assay Sensitivity

| Factor | Low-Sensitivity Assay | High-Sensitivity Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Required | 10 mg | 1 mg |

| Reagent Cost | Very High | Up to 10× lower |

| Signal-to-Background Ratio | Marginal | Excellent |

| IC₅₀ Accuracy | Moderate | High |

| Ability to use low [Substrate] | Limited | Fully enabled |

This reduction in enzyme usage is not merely a cost-saving measure; it is a concrete step towards reducing the resource intensity of pharmaceutical and biotech research. For a single 100,000-compound screen, this can translate to a saving of over $20,000 in enzyme production costs alone, which itself has a cascading effect on the associated environmental footprint of producing those reagents [10].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Application Note: Identification of Effective Antiviral 3CLpro Inhibitors

Objective: To identify potent inhibitors of the 3CLpro enzyme, a key viral protease target, using a combination of HTS and in-silico analysis [11]. Background: The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the need for rapid drug discovery approaches. Targeting essential viral enzymes like 3CLpro with HTS allows for the quick identification of lead compounds. Methodology:

- Primary HTS: A diverse chemical library was screened against 3CLpro using a high-sensitivity, biochemical assay designed to run under initial-velocity conditions to ensure kinetic relevance [10].

- Hit Confirmation: Primary hits were re-tested in dose-response to determine preliminary IC₅₀ values.

- In-Silico Docking: Confirmed hits were subjected to molecular docking studies to predict their binding modes and affinity within the 3CLpro active site, informing subsequent medicinal chemistry optimization [11]. Outcome: The integrated approach successfully identified several novel 3CLpro inhibitors with sub-micromolar potency, validating the protocol as a powerful template for rapid antiviral development.

Protocol: HTS for Cellulase Enzymes in Lignocellulosic Biomass Degradation

Objective: To discover novel cellulase enzymes with high specific activity for improved saccharification of agricultural waste biomass. Sample Preparation:

- Enzyme Library: Cellulase enzymes were obtained from a metagenomic library derived from compost samples.

- Substrate: A fluorescently-labeled cellulose derivative was used to allow for homogeneous assay detection.

HTS Experimental Workflow:

- Assay Principle: The release of a fluorescent tracer upon enzymatic hydrolysis of the substrate is measured.

- Reaction Conditions:

- Final Volume: 50 µL

- Buffer: 50 mM Sodium Acetate, pH 5.0

- Substrate: 1 mg/mL (≤ Km concentration)

- Enzyme: 10 nM (enabled by high-sensitivity detection) [10]

- Incubation: 60 minutes at 50°C

- Detection: Fluorescence Intensity (Ex/Emm: 485/530 nm).

- Controls: Include no-enzyme (background) and a reference cellulase (positive control) on every plate.

- Data Analysis: Hits are identified as wells where signal exceeds the mean background by >3 standard deviations. Z'-factor is calculated for each plate to ensure robust assay quality [10].

Validation: Hit enzymes are expressed in larger quantities and characterized for specific activity and thermostability using traditional biochemical methods.

Visualizing the HTS-Bioeconomy Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from high-throughput enzyme discovery to its application in a biobased production system and the subsequent positive impact on environmental footprints.

Diagram 1: HTS to Bioeconomy Impact Workflow (76 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for HTS in Enzyme Discovery

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in HTS |

|---|---|

| Transcreener HTS Assays | A homogeneous, antibody-based assay platform for detecting nucleotide products (e.g., ADP, GDP). Its high sensitivity allows for the use of low enzyme and substrate concentrations, saving reagents and improving data quality [10]. |

| PubChem BioAssay Database | A public repository containing results from millions of biological assays. Researchers can query this database (e.g., using AID numbers) to retrieve HTS data on specific compounds or targets, providing a valuable resource for initial target assessment and data comparison [9]. |

| PUG-REST API | The PubChem Power User Gateway (PUG) using a REST-style interface. It allows for the automated, programmatic retrieval of large HTS datasets from PubChem, which is essential for computational modelers and bioinformaticians [9]. |

| Multi-Mode Microplate Reader | Instrumentation capable of detecting various signals (e.g., Fluorescence Intensity, Polarization, TR-FRET) is crucial for running diverse HTS assays in a high-throughput format [10]. |

| Chemical Identifier Tools (SMILES, InChIKey) | Standardized textual representations of chemical structures. These identifiers are essential for accurately querying and retrieving compound-specific HTS data from public databases like PubChem [9]. |

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) has revolutionized enzyme research and drug discovery by enabling the rapid testing of thousands to millions of biochemical samples in an automated, parallelized manner [12]. In the context of enzyme activity research, HTS workflows are indispensable for efficiently characterizing enzyme function, engineering enzymes with enhanced properties, and identifying enzyme inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents [13] [14]. The power of HTS lies in its integration of three core technological components: robotic liquid handlers for automation, specialized microplates for miniaturized reactions, and sophisticated detection systems for measuring enzymatic activity [15]. This application note details the function, selection criteria, and implementation protocols for each of these components, providing researchers with practical guidance for establishing robust HTS workflows for enzymatic assays. By enabling the comprehensive analysis of enzyme libraries under varied conditions, these integrated systems help accelerate the pace of investigation into enzymatic activities with significant implications for industrial and medical applications [16].

Robotic Handlers for Automated Liquid Handling

System Types and Selection Criteria

Robotic liquid handlers are the workhorses of any HTS workflow, automating the repetitive pipetting tasks that would be impractical to perform manually at such scales. These systems range from low-cost, accessible platforms to highly sophisticated, integrated robotics. The selection of an appropriate system depends on several factors, including throughput requirements, budget, and application specificity.

Table 1: Comparison of Robotic Liquid Handling Platforms

| Platform Type | Example Systems | Throughput | Relative Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Cost/Benchtop | Opentrons OT-2 [16] | 96-384 wells | $20,000-30,000 USD | Academic labs, specific, lower-throughput workflows |

| Dedicated Purification Systems | KingFisher [16] | 96 samples | ~$80,000 USD | Biomolecule purification (e.g., His-tagged enzymes) |

| High-End/Flexible | Hamilton, Tecan [16] | 96-1536 wells | >$150,000 USD | Large-scale, diverse screening campaigns in core facilities |

For enzyme discovery, platforms like the Opentrons OT-2 demonstrate how low-cost automation can be leveraged to create a robot-assisted pipeline for high-throughput protein purification, enabling the parallel processing of 96 enzymes in a well-plate format and scaling to hundreds of proteins purified per week [16]. These systems use open-source Python scripts for protocol control, enhancing their accessibility and adaptability for specific enzymatic assays.

Implementation Protocol: Automated Enzyme Purification

The following protocol, adapted from a high-throughput enzyme discovery pipeline, outlines the steps for using a robotic handler to purify enzymes from E. coli in a 96-well format [16].

Objective: To achieve parallel transformation, inoculation, and purification of 96 enzyme variants. Key Features: Uses magnetic bead-based Ni-affinity purification and protease cleavage to avoid imidazole elution, which can interfere with downstream assays.

Materials and Reagents:

- Competent Cells: E. coli (e.g., Zymo Mix & Go! kit) [16]

- Expression Plasmid: Contains gene of interest with an N-terminal His-SUMO tag (or other affinity tag) [16]

- Media: LB broth with appropriate antibiotic

- Lysis/Binding Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0

- Wash Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0

- Cleavage Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0

- Ni-charged Magnetic Beads

- SUMO Protease (or other specific protease)

- Labware: 96-well deep-well plates, 96-well PCR plates, magnetic plate stand

Procedure:

- Transformation: The robot combines plasmid DNA with competent E. coli cells in a 96-well plate. After incubation on ice and an outgrowth step, antibiotic is added, and the culture is grown to saturation (~40 hours at 30°C). This bypasses the need for plating and colony picking [16].

- Inoculation and Expression: The robot uses the saturated transformation culture to inoculate 2 mL of autoinduction media in a 24-deep-well plate. This plate is then incubated in a shaker-incubator for protein expression.

- Cell Lysis and Binding: The robot resuspends cell pellets in Lysis/Binding Buffer. After cell disruption (e.g., by chemical or enzymatic means), the lysate is transferred to a new plate containing Ni-charged magnetic beads. The plate is mixed to allow binding of the His-tagged enzyme to the beads.

- Bead Washing: The robot places the plate on a magnetic stand to capture the beads and aspirates the supernatant. The beads are then resuspended in Wash Buffer to remove weakly bound proteins. This wash step is typically repeated.

- Protease Elution: The robot aspirates the final wash and resuspends the beads in Cleavage Buffer containing the SUMO protease. The plate is incubated to allow for cleavage, which releases the target enzyme from the bead-bound His-SUMO tag. The plate is returned to the magnetic stand, and the supernatant containing the purified, tag-less enzyme is transferred to a final storage plate.

Diagram: Automated Enzyme Purification Workflow. This robot-assisted protocol enables parallel processing of 96 enzyme variants [16].

Microplates: The Foundation of Miniaturization

Microplate Selection Guide

The microplate is the fundamental unit of HTS, enabling the miniaturization of reactions. The choice of microplate is a critical technical decision that directly impacts assay performance, data quality, and cost [17]. Selection should be based on a hierarchical decision process starting with the assay type and detection mode.

Table 2: Guide to Microplate Selection for Enzymatic HTS

| Selection Factor | Options | Recommendation for Enzyme Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Well Density | 96, 384, 1536 | 96-well: Assay development, low throughput [18]. 384-well: Moderate/high throughput, best balance for many labs [12]. 1536-well: Ultra-HTS for >100,000 compounds; requires specialized automation [15]. |

| Bottom Type | Clear, White, Black | Clear: For colorimetric/absorbance assays [18]. Black: For fluorescence assays (reduces crosstalk) [18]. White: For luminescence & TRF (reflects and amplifies signal) [18]. |

| Material | Polystyrene (PS), Cyclic Olefin Copolymer (COC), Polypropylene (PP) | PS: Standard, cost-effective for most aqueous assays. COC: Superior chemical resistance, low binding, high clarity for imaging [18]. PP: For organic solvent storage/resistance. |

| Surface Treatment | Non-binding, Tissue Culture (TC) treated | Non-binding: For biochemical assays to prevent enzyme/protein adsorption [17]. TC-treated: For cell-based enzymatic assays. |

| Well Geometry | Flat, Round, V-bottom | Flat-bottom: Ideal for spectroscopic readings. Round/V-bottom: For bead-based assays and efficient small-volume mixing. |

The process often begins with deciding between a cell-free (biochemical) or cell-based assay, which dictates subsequent choices for surface treatment and other properties [17]. For biochemical enzyme assays, non-binding surfaces are recommended to prevent the adsorption of the enzyme or substrate to the plastic, which could lower the apparent activity [17].

Implementation Protocol: Microplate Assay for Enzyme Activity

This general protocol describes how to set up a microplate-based activity assay for a hydrolytic enzyme, a common scenario in enzyme engineering and discovery.

Objective: To measure the kinetic activity of an enzyme against a substrate in a 96- or 384-well microplate format. Key Features: Can be adapted for colorimetric, fluorometric, or luminescent detection.

Materials and Reagents:

- Enzyme: Purified enzyme, either commercially sourced or purified via an automated protocol (see Section 2.2).

- Substrate: Specific substrate linked to a detectable signal (e.g., a chromogenic or fluorogenic derivative).

- Assay Buffer: Optimal pH buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, Phosphate). The use of Design of Experiments (DoE) can significantly speed up the optimization of buffer composition, pH, and ionic strength [19].

- Cofactors: Any required cofactors (e.g., metal ions, NADH, ATP).

- Stop Solution: If required (e.g., acid or base to quench the reaction).

- Labware: Appropriate microplate (see Table 2), multichannel pipettes or liquid handler, plate sealers.

Procedure:

- Plate Configuration: Design the plate layout, designating wells for test samples, positive controls (e.g., enzyme with known active substrate), negative controls (e.g., no enzyme, inactive enzyme), and blank (substrate only).

- Dispense Reagents: Using a multichannel pipette or robotic handler, dispense the assay buffer and any cofactors into all wells.

- Add Enzyme: Add the enzyme solution to all wells except the negative control and blank wells. Add buffer or storage buffer to those control wells.

- Initiate Reaction: Add the substrate solution to all wells to start the enzymatic reaction. For kinetic reads, this step is often performed by the liquid handler immediately before the plate is placed into the pre-heated microplate reader.

- Incubate and Detect: Incubate the plate at the desired temperature (often controlled by the reader) and measure the signal (absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) at a single time point (endpoint) or at multiple time points (kinetic mode).

- Data Analysis: Calculate enzyme activity based on the rate of signal change over time, corrected for the background signal from the blank and negative controls.

Detection Systems for Measuring Enzyme Activity

Detection Technologies and Their Applications

Detection systems, primarily microplate readers, are used to quantify the outcome of enzymatic reactions by measuring changes in light absorption, emission, or other physical properties. The choice of detection method is dictated by the assay chemistry and the required sensitivity.

Table 3: Common Detection Methods in Enzymatic HTS

| Detection Method | Principle | Common Enzyme Assay Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Absorbance (UV-Vis) | Measures the amount of light a sample absorbs at a specific wavelength. | Hydrolysis of chromogenic substrates (e.g., p-nitrophenol derivatives), NADH/NADPH-coupled assays [13]. |

| Fluorescence | Measures light emitted by a fluorophore after excitation at a specific wavelength. | Hydrolysis of fluorogenic substrates, protease assays using FRET peptides, GFP-reporter assays [13] [14]. |

| Luminescence | Measures light output from a chemical or biochemical reaction (e.g., luciferase). | ATPase activity, reporter gene assays for metabolizing enzymes [12]. |

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) | Measures the change in rotational speed of a fluorescent molecule upon binding. | Protease activity (cleavage of a large fluorescent substrate), binding assays [12]. |

| Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET) | Measures energy transfer between a long-lifetime donor and an acceptor, with a time delay to reduce background. | Protein-protein interactions, kinase activity [12]. |

Emerging platforms, such as droplet microfluidics, are pushing the boundaries of HTS by compartmentalizing reactions into picoliter droplets, enabling throughputs of tens of thousands of assays per device with drastically reduced reagent consumption [14]. These systems often integrate with detection methods like fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for analysis and sorting of active enzyme variants [13] [14].

Implementation Protocol: A Fluorescence-Based Coupled Enzyme Assay

This protocol provides a specific example of a coupled enzyme assay using fluorescence detection, a highly sensitive and widely applicable method.

Objective: To measure the activity of a primary enzyme (Enzyme A) that produces a product which is a substrate for a second, reporter enzyme (Enzyme B) that generates a fluorescent signal. Key Features: Amplifies the signal from the primary reaction, allowing for sensitive detection.

Materials and Reagents:

- Enzyme A: The target enzyme of interest.

- Substrate A: The native substrate for Enzyme A.

- Enzyme B: The coupling enzyme (e.g., a dehydrogenase, oxidase).

- Detection Reagent: A fluorogenic substrate for the coupling enzyme's product (e.g., Amplex Red for H₂O₂, resorufin derivative for NADH).

- Assay Buffer

- Labware: Black or white 384-well microplate (black reduces crosstalk, white may amplify signal), fluorescent microplate reader.

Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Mix: In a tube, prepare a master mix containing Assay Buffer, Substrate A, Enzyme B, and the detection reagent. The concentrations should be optimized so that the coupling reaction is not rate-limiting.

- Dispense Master Mix: Using a liquid handler, dispense the master mix into all wells of the microplate.

- Add Enzyme A: Add the Enzyme A (or buffer for negative controls) to the respective wells to initiate the coupled reaction.

- Kinetic Read: Immediately transfer the plate to a fluorescence microplate reader pre-heated to the assay temperature. Measure the fluorescence (e.g., Ex/~570 nm, Em/~585 nm for resorufin) every 30-60 seconds for 15-60 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence vs. time. The initial linear rate of fluorescence increase is proportional to the activity of Enzyme A.

Diagram: Signaling Pathway for a Coupled Fluorescence Assay. Product A from the target enzyme is converted by a reporter enzyme into a detectable fluorescent product.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Enzymatic HTS Workflows

| Item | Function/Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Purification Tags | Enables high-throughput, automated purification of recombinant enzymes. | His-SUMO tag for Ni-NTA magnetic bead purification and scarless cleavage [16]. |

| Magnetic Beads | Solid support for automated biomolecule purification in plate formats. | Ni-charged magnetic beads for purifying His-tagged enzymes [16]. |

| Universal Detection Assays | Flexible, mix-and-read assays for multiple enzymes within a target class. | Transcreener ADP² Assay for kinases, ATPases, etc., using FP, FI, or TR-FRET [12]. |

| Chromogenic/Fluorogenic Substrates | Synthetic substrates that yield a detectable signal upon enzyme cleavage. | p-Nitrophenol (pNP) derivatives for absorbance; 4-Methylumbelliferyl (4-MU) for fluorescence [13] [20]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Systems | For rapid protein production without recombinant expression in cells, useful for toxic enzymes. | Used in In Vitro Compartmentalization (IVTC) assays [13]. |

The integration of robotic handlers, specialized microplates, and sensitive detection systems forms the technological triad that enables modern HTS for enzyme research. As detailed in these application notes and protocols, the careful selection and implementation of each component are critical for developing a robust, reproducible, and efficient workflow. The field continues to evolve with emerging trends such as the adoption of even higher-density microplates (3456-well), the integration of AI and machine learning for experimental planning and data analysis [21], and the rise of fully autonomous "self-driving" laboratories [21]. These advancements, coupled with the development of more sensitive and universal assay chemistries, promise to further accelerate the pace of enzyme discovery and engineering, ultimately contributing to breakthroughs in biotechnology, therapeutics, and green chemistry.

High-throughput screening (HTS) has revolutionized biological sciences by enabling the rapid experimentation necessary for modern enzyme discovery and drug development. This paradigm allows researchers to evaluate thousands of experimental conditions in parallel, dramatically accelerating the pace of scientific discovery. In enzyme research, HTS methodologies facilitate the identification of novel biocatalysts from natural diversity and the engineering of improved enzymes tailored for specific industrial applications [22]. Concurrently, in pharmaceutical research, HTS technologies are reshaping approaches to drug discovery by providing efficient methods for identifying compounds that interact with therapeutic targets [23]. The convergence of these fields through shared technological platforms represents a powerful trend in biotechnology, enabling more sustainable industrial processes and more efficient therapeutic development.

The integration of automation, miniaturization, and computational analytics has transformed traditional laboratory workflows into highly parallelized operations. This transition is critical for handling the enormous sequence spaces explored in modern enzyme engineering and the vast chemical libraries screened in drug discovery programs. As genomic databases expand and artificial intelligence tools advance, the demand for efficient characterization of large numbers of proteins and compounds has grown exponentially [16]. This article examines key applications of high-throughput methodologies across enzyme discovery, engineering, and drug target identification, providing detailed protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers working at this intersection.

High-Throughput Enzyme Discovery and Engineering

Automated Enzyme Engineering Pipeline

The development of a generalizable, low-cost pipeline for high-throughput protein purification represents a significant advancement in enzyme engineering capabilities. This robot-assisted workflow enables the parallel processing of hundreds of enzyme variants with minimal human intervention, addressing the critical bottleneck between sequence diversification and functional characterization [16].

Experimental Protocol: Low-Cost, Robot-Assisted Enzyme Expression and Purification

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning: Employ plasmid constructs containing affinity tags (e.g., histidine tag for Ni-affinity purification) and protease cleavage sites (e.g., SUMO site for scarless cleavage). Genes are codon-optimized and synthesized commercially, though this remains the costliest step in the protocol [16].

- Transformation: Use chemically competent E. coli cells transformed via simple incubation without heat shock. This method reduces cost, improves reproducibility, and avoids human intervention. Cells are grown directly as starter cultures, bypassing the need for plating transformations and picking colonies. Growth occurs for approximately 40 hours at 30°C to achieve saturation [16].

- Inoculation and Expression: Employ 24-deep-well plates with 2 mL cultures for improved aeration. Utilize autoinduction media to eliminate the need to monitor cell density for induction timing. This approach enables standard shaker-incubators with larger orbits (19 mm) rather than specialized plate shakers [16].

- Purification: Utilize nickel-charged magnetic beads for affinity purification. Instead of imidazole elution (which can interfere with downstream analyses), employ protease cleavage to release the target protein. This "tagless" elution avoids the need for buffer exchange, which remains challenging for small-volume samples in plate format [16].

- Analysis: The resulting purified enzymes demonstrate sufficient yield (up to 400 µg) and purity for comprehensive analyses of thermostability and activity, generating standardized benchmark datasets for comparative enzyme evaluation [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| pCDB179 Plasmid | Vector with His-tag and SUMO site for affinity purification and scarless cleavage |

| Zymo Mix & Go! Transformation Kit | Enables chemical transformation without heat shock, improving reproducibility |

| Nickel-charged Magnetic Beads | Affinity purification matrix for capturing His-tagged fusion proteins |

| SUMO Protease | Cleaves fusion protein to release untagged target enzyme |

| Autoinduction Media | Eliminates need for monitoring cell density and manual induction |

| 24-Deep-Well Plates | Enables adequate aeration for protein expression in small volumes |

Quantitative Analysis of Enzyme Market and Applications

The growing importance of enzymes across multiple industries is reflected in market data, which shows consistent expansion driven by technological advancements and increasing adoption in industrial processes.

Table 1: Global Enzymes Market Outlook (2025-2035) [24]

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Market Value (2025) | USD 15.4 billion |

| Projected Market Value (2035) | USD 29.7 billion |

| Forecast CAGR (2025-2035) | 6.8% |

| Leading Product Segment (2025) | Proteases (32.8% market share) |

| Leading Application Segment (2025) | Food & Beverage (27.4% market share) |

Table 2: Specialty Enzymes Market Forecast by Application (2025-2029) [25]

| Application Segment | Key Applications | Market Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Research and Biotechnology | DNA modification, sequencing, molecular biology, gene therapy | Valued at USD 2.49 billion in 2019; shows continued growth |

| Diagnostics | Medical diagnostics, disease detection | Driven by healthcare expenditure and aging population |

| Pharmaceuticals | Chronic disease treatment, biosimilar development | Applications in cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes therapies |

| Industrial Applications | Food production, biofuels, detergents | Enzymes improve efficiency and sustainability of processes |

The specialty enzymes market is forecast to increase by USD 2.51 billion at a CAGR of 7.5% between 2024 and 2029, with North America estimated to contribute 33% to the global market growth during this period [25]. This growth is being shaped by rising applications across food processing, pharmaceuticals, biofuels, and industrial sectors, with enzymes valued for their catalytic efficiency, ability to accelerate reactions under mild conditions, and reduced energy requirements [24].

Workflow Visualization: High-Throughput Enzyme Screening

Diagram 1: HTS Enzyme Engineering Workflow. This automated pipeline enables parallel processing of hundreds of enzyme variants from gene to functional characterization.

High-Throughput Approaches in Drug Target Identification

Structural Dynamics Response (SDR) Assay for Drug Discovery

The Structural Dynamics Response (SDR) assay represents an innovative approach to drug target identification that addresses key challenges in conventional drug screening methods. Developed by NIH scientists, this relatively straightforward test is based on the natural vibrations of proteins and can determine if and how well drug candidates bind to target proteins without requiring target-specific reagents or specialized instruments [23].

Experimental Protocol: SDR Assay Implementation

- Principle: SDR measures changes between the motion of a protein's ligand-free and ligand-bound states by altering the light output of a sensor protein. Ligand binding changes protein structure, ranging from geometric rearrangements to subtle reductions in protein vibrations [23].

- Sensor System: Utilize NanoLuc luciferase (NLuc) as a sensor protein because the intensity of light it emits is readily modulated by the attached target protein's ligand-influenced motions. For increased light output, employ a "split" version where a small piece of NLuc is attached to the target protein [23].

- Assay Assembly: When the NLuc is reformed by adding back the missing larger NLuc fragment, SDR is measured as a change in light intensity generated from the intact sensor protein. By observing the amount of light produced by ligand-protein complexes, researchers can determine whether and how strongly drug ligands interact with target proteins [23].

- Application: The assay requires only a fraction of the protein needed for standard tests and works across a wide range of proteins. Unlike standard methods that typically work only for specific protein types, SDR functions without needing knowledge of protein function or specialized techniques, substrates, or cofactors [23].

- Validation: In experimental comparisons, SDR identified ABL1 kinase inhibitors as well as or better than standard enzyme assays. Importantly, SDR could detect compounds binding at remote allosteric sites on ABL1, which standard kinase activity assays failed to identify [23].

DTIAM: A Unified Framework for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

Computational approaches complement experimental methods in high-throughput drug target identification. DTIAM represents a unified framework for predicting drug-target interactions (DTIs), binding affinities, and mechanisms of action (MoA) based on self-supervised learning [26].

Experimental Protocol: DTIAM Implementation for Drug-Target Prediction

- Architecture Overview: DTIAM consists of three modules: (1) a drug molecular pre-training module based on multi-task self-supervised learning for extracting features from molecular graphs; (2) a target protein pre-training module using Transformer attention maps for extracting features from protein sequences; and (3) a unified drug-target prediction module for predicting DTI, binding affinity, and MoA [26].

- Drug Representation Learning: The drug molecule pre-training module takes molecular graphs as input, segments them into substructures, and learns representations through three self-supervised tasks: Masked Language Modeling, Molecular Descriptor Prediction, and Molecular Functional Group Prediction. This approach leverages attention mechanisms to prioritize relevant substructures and relationships [26].

- Target Representation Learning: The target protein pre-training module uses Transformer attention maps to learn representations and contacts of proteins based on unsupervised language modeling from large amounts of protein sequence data [26].

- Interaction Prediction: The drug-target prediction module integrates information from both drug and target representations to capture complex interactions. It employs various machine learning models within an automated framework utilizing multi-layer stacking and bagging techniques [26].

- Performance: DTIAM achieves substantial performance improvements over state-of-the-art methods across all tasks, particularly in cold-start scenarios where new drugs or targets are introduced. The framework successfully identifies effective inhibitors validated by whole-cell patch clamp experiments and demonstrates strong generalization ability in independent validation [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| NanoLuc Luciferase (NLuc) | Sensor protein whose light output changes with target protein dynamics |

| Split NLuc Fragments | Enhanced system for increased light output in SDR assays |

| Target Proteins | Therapeutic proteins of interest for drug screening |

| Compound Libraries | Collections of drug candidates for high-throughput screening |

| Molecular Graph Data | Structured representation of drug compounds for computational analysis |

| Protein Sequence Databases | Comprehensive collections of target protein sequences for machine learning |

Workflow Visualization: Drug Target Identification

Diagram 2: Drug Target Identification Pathways. Complementary experimental and computational approaches converge to identify and validate therapeutic targets and compounds.

Integrated Applications and Future Perspectives

The convergence of high-throughput methodologies in enzyme engineering and drug discovery creates powerful synergies for biotechnology and pharmaceutical applications. Enzymes engineered through HTS approaches are themselves becoming important therapeutic agents, with applications ranging from enzyme replacement therapies to targeted degradation of disease-associated proteins [24] [25]. Similarly, drug discovery platforms are increasingly incorporating enzymatic assays for high-content screening of compound libraries.

The ongoing development of automated, low-cost platforms for protein production and characterization is democratizing access to high-throughput capabilities [16]. As these technologies become more accessible and computational methods like DTIAM continue to advance [26], the pace of discovery in both enzyme engineering and drug development is expected to accelerate. Furthermore, innovative assay technologies like SDR [23] provide versatile tools that bridge both fields by enabling rapid characterization of molecular interactions without requiring specialized reagents or prior knowledge of protein function.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating experimental and computational approaches more seamlessly, enabling iterative design-build-test-learn cycles that leverage both artificial intelligence and robotic automation. These advances will continue to blur the traditional boundaries between enzyme discovery, protein engineering, and pharmaceutical development, creating new opportunities for interdisciplinary research and application.

Advanced HTS Assay Technologies and Their Industrial Applications

In the field of drug discovery and enzyme research, high-throughput screening (HTS) is indispensable for rapidly evaluating thousands of compounds. Modern enzyme activity assays provide the sensitivity, specificity, and robustness required for these campaigns, enabling researchers to identify and characterize potential drug candidates that modulate disease-associated enzymes. By accurately measuring a compound's effect on enzyme activity, these assays offer crucial insights for therapeutic intervention, bridging the gap between early discovery and translational medicine. Fluorescence, Time-Resolved Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (TR-FRET), and Bioluminescence have emerged as three pivotal technologies driving innovation in this space. This article details the principles, applications, and practical protocols for these key assay formats, providing a structured resource for scientists engaged in enzyme activity research.

Fluorescence-Based Enzyme Assays

Principles and Applications

Fluorometric assays measure enzyme activity by detecting changes in fluorescence intensity, polarization, or lifetime. They offer high sensitivity, real-time monitoring capabilities, and are adaptable to high-throughput formats. The assays typically utilize substrates that are either inherently fluorescent or become fluorescent upon enzymatic reaction (e.g., using quenched substrates or those that generate fluorescent products) [27]. Their versatility makes them essential for studying enzyme kinetics, inhibitor screening, and mechanistic studies.

A primary application in drug discovery is target identification and validation, where researchers use enzyme assays to evaluate the biological role of enzymes linked to diseases like cancer, autoimmune, and neurodegenerative disorders [28]. Furthermore, fluorescence-based assays are fundamental for dose-response studies, determining compound potency (IC₅₀ or EC₅₀), and for kinetic and mechanistic analyses to elucidate inhibition modes (e.g., competitive, non-competitive, allosteric) [28].

Protocol: Fluorometric Assay for Hydrolase Enzymes

This protocol is adapted for high-throughput screening of hydrolytic enzymes involved in the endocannabinoid system, such as Monoacylglycerol Lipase (MAGL) or Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase (FAAH) [27].

Key Reagents

- Fluorogenic Substrate: A substrate specific to the target hydrolase (e.g., a monoacylglycerol or fatty acid amide analogue conjugated to a fluorophore like 7-hydroxy-9H-(1,3-dichloro-9,9-dimethylacridin-2-one) (DDAO)) [27].

- Assay Buffer: A suitable buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl or phosphate buffer), often supplemented with detergents like Brij-35 to prevent enzyme aggregation [27].

- Enzyme Solution: Purified recombinant or native enzyme.

- Control Inhibitor: A known, potent inhibitor for the enzyme (e.g., JZL184 for MAGL) for assay validation.

- Test Compounds: Library compounds dissolved in DMSO.

Procedure

- Prepare Reaction Mixture: In a black, low-volume 384-well microplate, add assay buffer, the fluorogenic substrate (at a concentration near its Km for initial velocity conditions), and the test compound or control inhibitor.

- Initiate Reaction: Start the enzymatic reaction by adding the enzyme solution. The final reaction volume is typically 10-50 µL.

- Incubate: Incubate the plate at room temperature or 37°C for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) to remain within the linear range of the reaction.

- Measure Fluorescence: Read the plate using a fluorescence microplate reader. The excitation and emission wavelengths are set according to the fluorophore used (e.g., for DDAO, Ex ~600 nm, Em ~650 nm).

Data Analysis

- Enzyme activity is proportional to the increase in fluorescence intensity over time.

- For inhibitor screening, percent inhibition is calculated relative to control wells containing no inhibitor (100% activity) and no enzyme (0% activity).

- Dose-response curves are generated from percent inhibition data to determine IC₅₀ values.

TR-FRET Enzyme Assays

Principles and Applications

TR-FRET combines the sensitivity of fluorescence with time-gated detection to minimize background interference. It relies on energy transfer from a long-lifetime donor (e.g., a terbium (Tb) chelate) to an acceptor fluorophore when they are in close proximity (1-10 nm) [29] [30]. The time-resolved measurement allows for the elimination of short-lived background fluorescence, resulting in a superior signal-to-noise ratio [29]. This ratiometric method (measuring the acceptor/donor emission ratio) also reduces well-to-well variability [30].

TR-FRET is widely used for studying kinase and protein kinase C (PKC) activity [30]. It is also a powerful tool for target engagement studies, determining if a compound binds to its intended target in both biochemical and cellular settings [29]. A significant advantage is the development of universal assays, such as those detecting common products like S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) for methyltransferases, which work across entire enzyme families without requiring customized substrates [31].

Protocol: AptaFluor SAH Methyltransferase TR-FRET Assay

This protocol describes a universal, mix-and-read TR-FRET assay for histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) [31].

Key Reagents

- SAM: S-adenosylmethionine, the methyl donor substrate.

- SAH Detection Mix: Contains a split RNA aptamer specific for SAH; one half is labeled with a Tb-chelate donor and the other with a DyLight 650 acceptor. SAH binding brings the two halves together, generating a FRET signal [31].

- Enzyme Stop Reagent: A 10X solution containing SDS to quench the methyltransferase reaction.

- SAH Detection Buffer: A 10X buffer providing optimal conditions for aptamer assembly.

- Methyltransferase Enzyme: Purified HMT or DNMT.

- Acceptor Substrate: The methyl group acceptor (e.g., peptide, histone, nucleosome, or oligonucleotide).

Procedure

- Enzyme Reaction: In a white, low-volume 384-well plate, mix the methyltransferase enzyme with SAM, the acceptor substrate, and test compounds in an appropriate reaction buffer. Incubate to allow the conversion of SAM to SAH.

- Quench Reaction: Add the Enzyme Stop Mix (a 1X dilution of the stop reagent in SAH Detection Buffer) to terminate the reaction and denature the enzyme.

- SAH Detection: Add the prepared SAH Detection Mix to the quenched reaction.

- Incubate and Read: Incubate the plate for signal equilibration (e.g., 60 minutes), then read on a TR-FRET capable microplate reader. Standard settings include an excitation filter around ~337 nm, and emission filters for Tb (~490 nm) and DyLight 650 (~650 nm) [31].

Data Analysis

- The TR-FRET signal is calculated as the ratio of acceptor emission (665 nm) to donor emission (490 nm), multiplied by 10,000 to give a milliratio [31].

- The signal is directly proportional to the amount of SAH produced, allowing for the quantification of enzyme activity.

- Z'-factor values, a measure of assay quality and robustness, are often >0.5, making it suitable for HTS [29] [30].

Bioluminescence-Based Enzyme Assays

Principles and Applications

Bioluminescence assays utilize light emitted from an enzymatic reaction, typically catalyzed by a luciferase. Unlike fluorescence, the excitation energy is supplied chemically by the luciferase substrate (e.g., luciferin or coelenterazine) rather than by a light source [32]. This eliminates issues of photobleaching and autofluorescence, resulting in an ultrasensitive detection method with a wide dynamic range [32].

A common application is the luciferase reporter assay, used to study gene expression and regulation by fusing regulatory genetic elements to a luciferase gene [32]. Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) and its variant NanoBRET are powerful for monitoring protein-protein interactions and target engagement in live cells under physiologically relevant conditions [29]. Cell viability and proliferation assays also heavily rely on bioluminescence to quantitate cellular ATP levels, which correlate with the number of metabolically active cells [32].

Protocol: NanoBRET Target Engagement Assay

This protocol measures the engagement of a small molecule with its protein target in a cellular context, using NanoLuc luciferase as the donor and a fluorescent tracer as the acceptor [29].

Key Reagents

- Cells Expressing NanoLuc-Fusion Protein: Cells transfected with a construct where the target protein is fused to the small, bright NanoLuc luciferase.

- Fluorescent Tracer: A high-affinity, cell-permeable ligand for the target protein, labeled with a red-shifted fluorophore compatible with NanoLuc emission (e.g., BODIPY 576/589, also known as NanoBRET 590) [29].

- NanoLuc Substrate (Furimazine): The cell-permeable substrate for NanoLuc.

- Test Compounds: Unlabeled compounds to compete with the tracer.

Procedure

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Seed cells expressing the NanoLuc-fusion protein into a multi-well plate. Allow cells to adhere.

- Add Compounds and Tracer: Treat cells with the test compounds and the fluorescent tracer. Incubate to allow equilibrium binding.

- Add Substrate and Measure: Add furimazine to the culture medium. Immediately measure the emission signals using a plate reader capable of detecting both luminescence (donor signal) and fluorescence (acceptor signal). A 610 nm long-pass filter is often used to collect the BRET signal [29].

Data Analysis

- The BRET ratio is calculated as the emission of the acceptor fluorophore divided by the emission of the NanoLuc donor.

- A decrease in the BRET ratio upon addition of a test compound indicates displacement of the tracer and successful target engagement.

- Competition binding curves are generated to calculate binding constants (Kd), which should be consistent with those obtained from biochemical assays like TR-FRET, confirming biological relevance [29].

Comparative Analysis of Assay Formats

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three enzyme assay formats to guide selection for specific research applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern Enzyme Assay Technologies

| Parameter | Fluorescence | TR-FRET | Bioluminescence (NanoBRET) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readout | Fluorescence intensity, polarization | Ratiometric (Acceptor/Donor emission) | Ratiometric (Acceptor/Donor emission) |

| Excitation Source | Light (e.g., laser, lamp) | Light (time-gated) | Chemical reaction (enzyme-substrate) |

| Key Advantage | Real-time kinetics, high sensitivity | Low background, reduced compound interference | Ultra-high sensitivity, minimal background in cells |

| Primary Limitation | Autofluorescence, photobleaching | Requires specific antibody/proximity pair | Requires genetic engineering (luciferase fusion) |

| Throughput | High | High | High |

| Typical Z' Factor | Varies; can be high | 0.5 - 0.94 (Excellent for HTS) [29] [30] | Up to 0.80 (Excellent for HTS) [29] |

| Context | Biochemical, purified systems | Biochemical & cellular target engagement [29] | Live-cell, physiologically relevant [29] |

| Example Kd (nM) | Varies by assay | 443 - 608 (RIPK1 Tracers) [29] | Consistent with TR-FRET data [29] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these advanced assay formats requires specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details key solutions for the protocols described in this article.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates | Enzyme-specific substrates that generate a fluorescent signal upon cleavage or modification. | Hydrolytic enzyme activity assays (e.g., for MAGL, FAAH) [27]. |

| TR-FRET Tracers (e.g., T2-BODIPY-FL/589) | High-affinity, fluorescently labeled ligands that bind to the target protein, enabling competition studies. | Cross-platform target engagement assays for RIPK1 [29]. |

| Lanthanide-Labeled Donors (e.g., Tb-chelate) | Long-lifetime fluorescent donors for TR-FRET, enabling time-gated detection. | TR-FRET kinase & methyltransferase assays [30] [31]. |

| Split Aptamer Detection Systems | Bimolecular probes that assemble in the presence of a product (e.g., SAH), generating a FRET signal. | Universal methyltransferase activity assays [31]. |

| NanoLuc Luciferase | A small, bright luciferase enzyme used as a BRET donor in fusion proteins. | NanoBRET cellular target engagement assays [29]. |

| Furimazine | A synthetic, cell-permeable substrate for NanoLuc luciferase with a bright, stable glow-type output. | Providing the light source for NanoBRET and other NanoLuc-based assays [29]. |

| White, Low-Volume, Non-Binding Microplates | Maximize signal collection and minimize reagent usage and non-specific binding. | All plate-based assays, especially TR-FRET and bioluminescence [31]. |

The strategic selection of enzyme assay formats is a critical determinant of success in high-throughput screening and drug discovery. Fluorescence, TR-FRET, and bioluminescence each offer a unique set of advantages, from the kinetic simplicity of fluorescence to the low-background precision of TR-FRET and the physiological relevance of bioluminescent NanoBRET. As demonstrated, these technologies are not mutually exclusive; the emerging capability of using single tracers across TR-FRET and NanoBRET platforms enhances data consistency between biochemical and cellular contexts [29]. By leveraging the detailed protocols and comparative analysis provided herein, researchers can effectively apply these powerful tools to accelerate the discovery and characterization of novel therapeutic agents.

Label-free detection strategies have emerged as transformative tools in high-throughput screening (HTS) for enzyme activity research, enabling researchers to monitor biological interactions in their native states without fluorescent or radioactive labels. These approaches measure intrinsic molecular properties—such as mass, refractive index, or electrical impedance—to provide real-time kinetic data on enzyme function and inhibition. By eliminating the need for molecular tags that can sterically hinder enzyme activity or produce false positives, label-free methods deliver more physiologically relevant data and streamline assay development. Within the pharmaceutical industry, these technologies are accelerating drug discovery by providing direct insights into enzyme kinetics, mechanism of action, and compound profiling during early screening phases.

The adoption of label-free biosensors is gaining significant traction across various sectors, from academic research to biomanufacturing, due to their efficiency and reliability [33]. These systems are particularly valuable in enzyme research where understanding authentic biomolecular interactions is crucial for identifying promising drug candidates or engineered enzymes with enhanced properties. This application note details the implementation of label-free substrates and sensor systems within HTS workflows, providing structured protocols and analytical frameworks for researchers engaged in enzyme activity research and drug development.

Label-Free Biosensor Technologies: Principles and Comparison

Label-free biosensors function by transducing intrinsic biomolecular interactions—such as substrate binding or catalytic turnover—into quantifiable physical signals. Unlike label-dependent methods that rely on reporter molecules, these systems monitor changes in mass, refractive index, or electrical properties at sensor surfaces in real time. This capability provides direct insight into enzyme kinetics, affinity, and concentration without potential artifacts introduced by labeling.

Several sensing principles form the foundation of modern label-free platforms. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) utilize optical phenomena to detect changes in surface mass concentration when molecules bind to an immobilized substrate [33]. Field-effect transistor (FET)-based biosensors detect electrical charge changes induced by biomolecular interactions at the gate electrode surface [34]. Emerging techniques like second-harmonic generation (SHG) imaging provide nanometer-scale spatial resolution to observe interfacial molecular adsorption and desorption dynamics in a label-free manner [34]. Additionally, electrochemical biosensors monitor electron transfer events during enzymatic reactions, with recent advancements utilizing novel materials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to enhance electron transfer efficiency between enzymes and electrodes [35].

The table below compares the key operational characteristics of major label-free biosensor technologies used in enzyme research:

Table 1: Comparison of Label-Free Biosensor Technologies for Enzyme Screening

| Technology | Detection Principle | Throughput Capacity | Key Applications in Enzyme Research | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Optical measurement of refractive index changes at a metal surface | Medium to High | Binding kinetics, inhibitor screening, substrate specificity | Affinity (KD), association/dissociation rates (kon, koff) |

| Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) | Spectral shift interference pattern from sensor tip surface | Medium to High | Rapid kinetic screening, antibody characterization, protein-protein interactions | Real-time binding kinetics and quantification |

| Field-Effect Transistor (FET) | Electrical detection of surface charge changes | High (with multiplexing) | Real-time enzyme activity monitoring, biomarker detection | Concentration, reaction rate |

| Electrochemical | Electron transfer measurement during redox reactions | High | Metabolite detection, oxidase/dehydrogenase activity, continuous monitoring | Enzyme activity, substrate concentration, inhibition potency |

| Interferometric Scattering | Light scattering from unlabeled biomolecules | Low to Medium (imaging) | Single-molecule enzyme kinetics, heterogeneous populations | Molecular count, binding events, conformational changes |

Application Notes: Implementing Label-Free Strategies in HTS Workflows

Strategic Integration into Screening Cascades

Implementing label-free detection within a high-throughput screening cascade requires careful planning to leverage its strengths while maintaining efficiency. A typical HTS campaign progresses through several stages: primary screening, confirmation, and validation [36]. Label-free methods are particularly valuable in the confirmation and validation phases where detailed kinetic profiling is essential for prioritizing lead compounds. For instance, after an initial primary screen of 1-1.5 million compounds using conventional methods, label-free technologies can be applied to the 5,000-50,000 confirmed hits for detailed mechanism-of-action studies [36].

The strategic advantage of label-free biosensors lies in their ability to provide rich kinetic data that informs structure-activity relationships early in the discovery process. In enzyme inhibitor screening, this approach can distinguish between competitive, non-competitive, and allosteric inhibition mechanisms based on real-time kinetic signatures, enabling medicinal chemists to make informed decisions about compound optimization. Furthermore, the direct nature of these assays reduces false positives common in labeled systems where compound interference with detection methods frequently occurs.

Quantitative Analysis of Screening Data

The quantitative data derived from label-free biosensors must be analyzed using appropriate statistical methods to ensure robust hit identification. Key parameters for analysis include Z'-factor for assay quality assessment, signal-to-background ratios, and coefficient of variation [36]. For enzyme kinetic studies, the following table summarizes critical parameters obtained from label-free biosensors:

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters from Label-Free Enzyme Screening

| Parameter | Description | Significance in Enzyme Research |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Response (RU) | Resonance units or response units measured in real-time | Direct measure of molecular binding events at the sensor surface |

| Association Rate (kon) | Rate constant for enzyme-substrate/inhibitor complex formation | Determines how quickly enzyme interacts with substrate/inhibitor |

| Dissociation Rate (koff) | Rate constant for complex breakdown | Measures stability of enzyme-substrate/inhibitor complex |

| Affinity (KD) | Equilibrium dissociation constant (koff/kon) | Overall measure of binding strength between enzyme and ligand |

| Maximum Response (Rmax) | Theoretical maximum binding response | Used to determine stoichiometry and active enzyme concentration |

| IC50/EC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory/effective concentration | Potency measure for enzyme inhibitors/activators |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enzyme Kinetic Profiling Using SPR Biosensors

This protocol describes the procedure for characterizing enzyme kinetics and inhibitor interactions using Surface Plasmon Resonance technology.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SPR-Based Enzyme Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SPR Instrument | Optical biosensor with fluidics system | Biacore series (Cytiva) or equivalent |

| Sensor Chip | Surface for immobilization | CM5 dextran chip for covalent immobilization |

| Running Buffer | Continuous phase for binding experiments | HEPES-buffered saline (HBS-EP: 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% surfactant P20, pH 7.4) |

| Activation Reagents | Covalent coupling chemistry | 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) |

| Quenching Solution | Blocking reactive groups | Ethanolamine HCl (1.0 M, pH 8.5) |

| Enzyme Solution | Target enzyme for immobilization | Purified enzyme in appropriate storage buffer, >90% purity |

| Analyte Compounds | Substrates/inhibitors for screening | Dissolved in DMSO stocks, diluted in running buffer |

Experimental Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sensor Surface Preparation

- Dock a new sensor chip according to instrument manufacturer's instructions.

- Prime the instrument system with running buffer (HBS-EP recommended) at a flow rate of 10-100 μL/min.

- Ensure all solutions are filtered (0.22 μm) and degassed before use.

Enzyme Immobilization

- Activate the carboxylated dextran surface by injecting a 1:1 mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS for 7 minutes.

- Dilute the enzyme to 5-50 μg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer at optimal pH (typically pH 4.0-5.5).

- Inject the enzyme solution for 5-15 minutes to achieve desired immobilization level (typically 5-15 kRU).

- Block remaining reactive esters by injecting 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 7 minutes.

Kinetic Measurements

- Dilute analyte compounds (substrates/inhibitors) in running buffer with DMSO concentration ≤1%.

- Establish a stable baseline with running buffer flowing at 30 μL/min.

- Inject analytes for 60-180 seconds (association phase) followed by running buffer for 120-300 seconds (dissociation phase).

- Use a multi-cycle method with randomized injection order to minimize systematic bias.

- Regenerate the enzyme surface between cycles with a 30-second pulse of appropriate regeneration solution (e.g., 10 mM glycine-HCl, pH 2.0-3.0).

Data Analysis

- Reference-subtract sensorgrams using a blank flow cell or buffer injections.

- Fit processed data to appropriate binding models (1:1 Langmuir, steady-state affinity, or more complex interaction models).

- Calculate kinetic parameters (kon, koff, KD) using the instrument's evaluation software.

Protocol 2: Real-Time Enzyme Activity Monitoring Using Electrochemical Biosensors

This protocol describes the procedure for monitoring enzyme activity in real-time using electrochemical biosensors with redox-active metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to enhance electron transfer efficiency.

Materials and Reagents

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Electrochemical Enzyme Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Workstation | Potentiostat for measurement | Three-electrode configuration with Ag/AgCl reference, Pt counter, and working electrode |

| MOF-Modified Electrode | Enzyme immobilization platform | Redox-active metal-organic framework (e.g., Zn-ZIF-8 with redox mediators) |

| Enzyme Solution | Target enzyme for immobilization | Purified enzyme in appropriate storage buffer |

| Substrate Solution | Enzyme substrate | Prepared in reaction buffer at appropriate concentration |

| Reaction Buffer | Electrochemical measurement medium | Phosphate-buffered saline (0.1 M, pH 7.4) with supporting electrolyte |

| Crosslinking Agent | Enzyme immobilization | Glutaraldehyde (0.1-2.5%) or EDC/NHS chemistry |

Experimental Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrode Modification with Redox-Active MOFs

- Polish the working electrode (typically glassy carbon, 3 mm diameter) with 0.05 μm alumina slurry and rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- Prepare redox-active MOF suspension (1-5 mg/mL) in appropriate solvent (typically ethanol or water).

- Deposit 5-10 μL of MOF suspension onto the electrode surface and allow to dry under ambient conditions.

- Alternatively, use electrophoretic deposition by applying potential to achieve uniform MOF coating.

Enzyme Immobilization

- Prepare enzyme solution at concentration of 1-10 mg/mL in appropriate buffer.

- Apply 5-10 μL enzyme solution to MOF-modified electrode and incubate for 1-2 hours at 4°C.

- For crosslinking, prepare 0.1-2.5% glutaraldehyde solution and apply to enzyme-coated electrode for 30 minutes.

- Rinse gently with reaction buffer to remove unimmobilized enzyme.

Electrochemical Measurements

- Assemble three-electrode system in electrochemical cell with modified working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and platinum counter electrode.

- Add 10-20 mL reaction buffer with supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl) to the electrochemical cell.

- For amperometric measurements, apply constant potential (enzyme-dependent, typically +0.3 to +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl) and allow current to stabilize.