IC50 Estimation in Enzyme Inhibition: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to IC50 estimation, a cornerstone metric for evaluating compound potency in enzymatic assays.

IC50 Estimation in Enzyme Inhibition: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to IC50 estimation, a cornerstone metric for evaluating compound potency in enzymatic assays. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of IC50, including its definition and relationship to binding affinity. The scope extends to detailed methodological protocols for experimental determination and computational prediction, advanced strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing assays, and rigorous frameworks for data validation and cross-study comparison. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy, reliability, and interpretability of IC50 data in pharmacological research and lead optimization.

Understanding IC50: The Fundamental Principles of Enzyme Inhibition Potency

Core Definition and Theoretical Foundation

The Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) is a quantitative measure that indicates how much of a particular inhibitory substance (e.g., a drug) is needed to inhibit a given biological or biochemical process by 50% in vitro [1]. It is a standard measure of the potency of an antagonist drug in pharmacological research [1]. The biological component being inhibited could be an enzyme, a cell, a cell receptor, or a microbe, and IC50 values are typically expressed as molar concentration [1].

The Relationship Between IC50, Ki, and the Cheng-Prusoff Equation

It is critical to understand that the IC50 value is an operational value dependent on assay conditions and is not a direct indicator of the intrinsic affinity of an inhibitor [2]. The absolute measure of affinity is the inhibition constant, Ki, which is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the inhibitor binding to its target [1] [2].

The relationship between IC50 and Ki is formally described by the Cheng-Prusoff equation [1]. For enzymatic reactions, the equation is: [ Ki = \frac{IC{50}}{1 + \frac{[S]}{K_m}} ] where:

- ( K_i ) is the binding affinity of the inhibitor.

- ( IC_{50} ) is the functional strength of the inhibitor.

- ( [S] ) is the fixed substrate concentration.

- ( K_m ) is the Michaelis constant (the concentration of substrate at which the enzyme activity is at half maximal) [1].

A similar equation exists for receptor binding assays, accounting for agonist concentration [1]. Whereas the IC50 value for a compound may vary between experiments depending on experimental conditions, the Ki is an absolute value [1].

pIC50 and its Utility

To facilitate easier comparison of compound potency, IC50 values are often converted to the pIC50 scale [1]. The formula for this conversion is: [ pIC{50} = -log{10}(IC_{50}) ] Due to the minus sign, higher values of pIC50 indicate exponentially more potent inhibitors [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Workflow for IC50 Determination

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for determining IC50, encompassing both traditional and modern approaches.

Detailed Protocol: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for Specific IC50 Determination

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) can be used to obtain IC50 values for individual ligand-receptor pairings with high molecular resolution, differentiating it from whole-cell assays [3].

Materials & Reagents:

- SPR Instrument (e.g., Biacore 2000)

- Sensor Chip (e.g., CM5)

- Running Buffer: HBS-EP/BSA (0.01 M HEPES, 0.5 M NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.005% (v/v) Tween 20, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4)

- Target Protein: Purified receptor-Fc fusion protein (e.g., ActRIIA-Fc, BMPRII-Fc)

- Ligand: The cytokine/growth factor of interest (e.g., BMP-4)

- Inhibitor: The pharmacologic agent being tested (e.g., Cerberus)

- Capture Surface: Anti-human IgG (Fc) antibody, immobilized on the sensor chip via amine-coupling chemistry

- Regeneration solution (e.g., MgCl₂)

Methodology:

- Surface Preparation: Immobilize an anti-Fc antibody onto a CM5 sensor chip using standard amine-coupling chemistry [3].

- Receptor Capture: Dilute the receptor-Fc fusion protein in running buffer and inject it over the experimental flow channel to capture it onto the anti-Fc surface. Aim for a low surface loading (approximately 200-300 Response Units, RU) to minimize steric hindrance and mass transport artifacts [3].

- Binding and Inhibition Assay:

- Pre-incubate a fixed concentration of the ligand (e.g., 60 nM BMP-4) with a range of concentrations of the inhibitor (e.g., Fc-free Cerberus) [3].

- Inject these pre-incubated mixtures over the experimental flow channel (with captured receptor) and a control flow channel.

- Use a high flow rate (e.g., 50 µl/min) to minimize mass transport artifacts.

- Data Analysis:

- Analyze sensorgrams by double referencing to account for nonspecific binding and bulk shifts.

- The reduction in the SPR binding response is proportional to the degree of inhibition.

- The data can be analyzed in two ways [3]:

- Plot the response (at a fixed time, e.g., 150 seconds) against the inhibitor concentration and fit the data to a dose-response curve (e.g., using GraphPad Prism) to determine the IC50.

- Fit the association or dissociation phases of the individual binding curves to obtain kinetic parameters (ka, kd), from which the IC50 can also be derived.

Detailed Protocol: The 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach) for Efficient Estimation

A 2025 study introduced a method that substantially reduces the number of experiments required for precise estimation of inhibition constants [4] [5].

Materials & Reagents:

- Standard enzymatic assay components: purified enzyme, substrate, inhibitor, buffer, and detection system.

- Software for nonlinear regression analysis (e.g., provided MATLAB or R packages for 50-BOA).

Methodology:

- Preliminary IC50 Estimation: First, determine an approximate IC50 value from % control activity data over a range of inhibitor concentrations ((IT)) using a single substrate concentration, typically at ( [S] = KM ) [4] [5].

- Single-Point Experimental Design: Instead of using multiple inhibitor concentrations, perform initial velocity measurements using a single inhibitor concentration that is greater than the preliminary IC50 value ((IT > IC{50})), across a range of substrate concentrations [4].

- Data Fitting with Harmonic Mean Relationship: Fit the initial velocity data to the mixed inhibition model (Equation 1, below), while incorporating the harmonic mean relationship between the IC50 and the inhibition constants ((K{ic}) and (K{iu})). This integration is key to the method's accuracy and is handled by the provided software packages [4] [5].

The general equation for the initial velocity of product formation under inhibition is: [ V0 = \frac{V{max} \cdot [ST]}{KM \left(1 + \frac{[IT]}{K{ic}}\right) + [ST] \left(1 + \frac{[IT]}{K{iu}}\right)} ] where (K{ic}) and (K_{iu}) are the inhibition constants for the enzyme and enzyme-substrate complex, respectively [4] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between IC50 and EC50? A: IC50 measures the potency of an inhibitory substance, indicating the concentration needed to inhibit a process by 50%. In contrast, EC50 (Half Maximal Effective Concentration) measures the potency of an excitatory or activatory substance, representing the concentration that produces 50% of the maximum effect in vivo [1] [6].

Q2: My IC50 value seems to change when I use different substrate concentrations. Is this normal? A: Yes, this is expected behavior for certain types of inhibition, particularly competitive inhibition. According to the Cheng-Prusoff equation, the measured IC50 for a competitive inhibitor will increase with increasing substrate concentrations, while the true Ki remains constant [1] [2]. This is a classic indicator of a competitive inhibition mechanism.

Q3: Why should I use a single high inhibitor concentration as in the 50-BOA method? A: Research has shown that data obtained with low inhibitor concentrations ((IT) much less than (K{ic}) and (K_{iu})) provides little information for precise estimation of inhibition constants and can even introduce bias. Using a single concentration greater than the IC50 provides more informative data for accurate and precise estimation, while also reducing experimental effort by over 75% [4] [5].

Q4: How do I handle time-dependent inhibition in my IC50 experiments? A: Time-dependent inhibition is common with reversible covalent inhibitors. If the IC50 decreases with longer pre-incubation or incubation times, it confirms time-dependence. For rigorous characterization, specialized methods like the EPIC-CoRe numerical model or implicit equations have been developed to fit time-dependent IC50 data and extract individual kinetic parameters (Ki, k₅, k₆) [7]. Simply reporting an IC50 at a single time point can be misleading for these inhibitors.

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Shallow or irregular dose-response curve | - Incorrect substrate concentration- Enzyme instability- Inhibitor solubility issues | - Verify [S] is at or near Km- Check enzyme activity over time- Use appropriate solvent and ensure inhibitor is fully dissolved |

| High variability between replicates | - Liquid handling inaccuracies- Poor cell viability (in cell-based assays)- Edge effects in microplates | - Calibrate pipettes and liquid handlers- Ensure consistent cell passage and health- Use interior wells and account for evaporation |

| IC50 value inconsistent with literature | - Differences in assay conditions (pH, ionic strength)- Different cell lines or enzyme sources- Variability in substrate purity | - Carefully replicate published assay conditions- Use standardized reagents where possible- Confirm substrate identity and quality |

| Poor fit to the logistic model | - The inhibitor does not follow a simple one-site binding model- Significant inhibitor depletion- Presence of allosteric or other complex mechanisms | - Check for stoichiometry; use lower enzyme concentration- Consider alternative models (e.g., for allosteric inhibitors) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting robust IC50 estimation experiments.

| Research Reagent | Function in IC50 Analysis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme / Receptor | The primary target of the inhibitory compound. | Source (recombinant vs. native), purity, and activity (U/mg) are critical for reproducibility. |

| Fluorogenic/Chemogenic Substrate | Allows quantification of enzymatic activity through a detectable signal (e.g., fluorescence, absorbance). | Select for specificity, signal-to-noise ratio, and compatibility with the inhibitor (no spectral overlap). |

| Reference Inhibitor (Control Compound) | A well-characterized inhibitor of the target used as a positive control to validate the assay. | Its known IC50/Ki in the system serves as a benchmark for assay performance. |

| High-Quality Chemical Library | A collection of compounds for screening in drug discovery. | Quality control is vital; inaccuracies in public compound data collections have been reported [6]. |

| SPR Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5) | The surface for immobilizing one interactant (e.g., receptor) in label-free binding studies. | The immobilization chemistry (amine, streptavidin) must be compatible with the target protein. |

| COSMO Solvation Model (in MOPAC) | An implicit solvation model used in computational chemistry to account for solvent effects when predicting protein-ligand interaction energies [8] [9]. | Considered robust and accurate for modelling solvent effects in computational docking studies. |

Advanced Concepts and Limitations

Moving Beyond IC50 in Drug Resistance

While IC50 is a valuable measure of potency, it has limitations in predicting clinical outcomes, especially in complex scenarios like drug resistance. A 2024 computational study on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) treatment contested the use of "fold-IC50" (the ratio of mutant IC50 to wild-type IC50) as the sole guide for treatment selection in resistant disease [10]. The study proposed that a parameter called "inhibitory reduction prowess"—the relative decrease of the product formation rate—could be a better indicator of a drug's efficacy against resistant mutants, as it incorporates more information about the system's dynamics [10].

Limitations of IC50 in High-Throughput Screening

In high-throughput drug discovery, several factors can limit the accuracy of IC50 values [6]:

- Variability in liquid handling can lead to concentration inaccuracies.

- Interactions between reagents and the assay can produce artifacts.

- Assay design and quality significantly influence the data.

- The basic assumption that percent inhibition and IC50 values correlate reasonably can sometimes break down, leaving room for error, especially when using the 4-parameter logistic Hill equation for fitting [6].

Core Concepts: Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between IC50, EC50, Ki, and LD50?

These parameters measure distinct concepts in pharmacology and toxicology. IC50 (Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration) is the concentration of an inhibitor that reduces a biological or biochemical process by 50% [11] [12]. EC50 (Half-Maximal Effective Concentration) is the concentration of a drug or agonist that induces a 50% response [11] [12]. Ki (Inhibition Constant) is an intrinsic measure of the binding affinity between an inhibitor and its enzyme or receptor, representing the dissociation constant [11] [13]. LD50 (Median Lethal Dose) is the dose of a substance that causes death in 50% of a test animal population [14] [15].

When should I use IC50 instead of Ki?

Use IC50 for a functional, operational measure of inhibitor potency under specific assay conditions; it is highly dependent on experimental setup, such as substrate concentration and incubation time [11] [16]. Use Ki to understand the true, intrinsic binding affinity between the inhibitor and the target; it is a more fundamental constant that describes the enzyme-inhibitor dissociation equilibrium [11] [13]. Ki is independent of enzyme concentration, while IC50 is dependent on it [13].

My IC50 value shifted when I changed my substrate concentration. Is this normal?

Yes, this is expected and actually reveals the mechanism of inhibition. The relationship between IC50 and substrate concentration [S] is determined by the inhibitor's mechanism [11]:

- Competitive Inhibition: IC50 increases with increasing [S] [11].

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: IC50 decreases with increasing [S] [11].

- Non-competitive Inhibition: IC50 is independent of [S] [11]. This dependency is why Ki is often a more reliable parameter for comparing inhibitors, as it can be derived from IC50 while accounting for the substrate concentration and inhibition mode [11].

Can IC50 and EC50 values ever be the same?

Yes, but only in the specific case where a drug at high concentrations completely inhibits a biological activity. In this scenario, the EC50 (concentration for 50% of the maximum effect) and IC50 (concentration for 50% inhibition) are identical [11]. However, if a drug only partially inhibits an activity even at high concentrations (partial inhibition), the IC50 may be undefined (if 50% inhibition is never reached), while the EC50 can still be reported to quantify the dose-response [11].

How does LD50 relate to these other parameters? Is it a measure of drug potency?

LD50 is fundamentally different from IC50, EC50, and Ki. While the others measure biochemical or pharmacological activity, LD50 is a measure of acute toxicity [14] [15]. It does not directly measure a drug's desired therapeutic potency but its lethal potential. A more relevant measure for a drug's safety is its therapeutic index, which is the ratio between its toxic dose (e.g., LD50) and its effective dose (ED50) [15].

Experimental Protocols & Troubleshooting

Precise Estimation of IC50 and Ki

Background: Traditional IC50 estimation can be resource-intensive and results may vary between studies. A modern approach, the 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach), substantially reduces the number of experiments required while improving precision [4].

Protocol: 50-BOA Method for Inhibition Constant Estimation [4]

- Preliminary IC50 Estimation: First, estimate the IC50 from % control activity data across a range of inhibitor concentrations using a single substrate concentration, typically at the Km value [4].

- Optimal Experimental Design: Instead of multiple inhibitor concentrations, use a single inhibitor concentration greater than the estimated IC50.

- Velocity Measurement: Measure the initial reaction velocity (V0) at this optimal inhibitor concentration across multiple substrate concentrations.

- Data Fitting: Incorporate the relationship between IC50 and the inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) during the fitting of the data to the velocity equation for mixed inhibition to derive the precise inhibition constants.

Troubleshooting Guide:

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| IC50 value is highly variable between replicates | Enzyme concentration is too high, affecting free inhibitor concentration in "tight binding" inhibition [11]. | Ensure enzyme concentration [E]T is much less than the apparent Ki. Apply a tight-binding correction if necessary [11]. |

| Incomplete inhibition, IC50 is undefined | The compound is a partial inhibitor; it cannot fully suppress activity even at high concentrations [11]. | Report the data using EC50 and the maximum % inhibition (efficacy) instead [11]. |

| IC50 decreases with longer pre-incubation time | The inhibitor is time-dependent (e.g., a slow-binding or reversible covalent inhibitor) [7]. | Characterize the IC50 at multiple time points. Use specialized methods (e.g., EPIC-CoRe modeling) to derive the individual inhibition and rate constants [7]. |

| Poor precision in estimated Ki | Sub-optimal choice of substrate and inhibitor concentrations in experimental design [4]. | Adopt the 50-BOA method, which uses a single, optimal inhibitor concentration to reduce bias and improve precision [4]. |

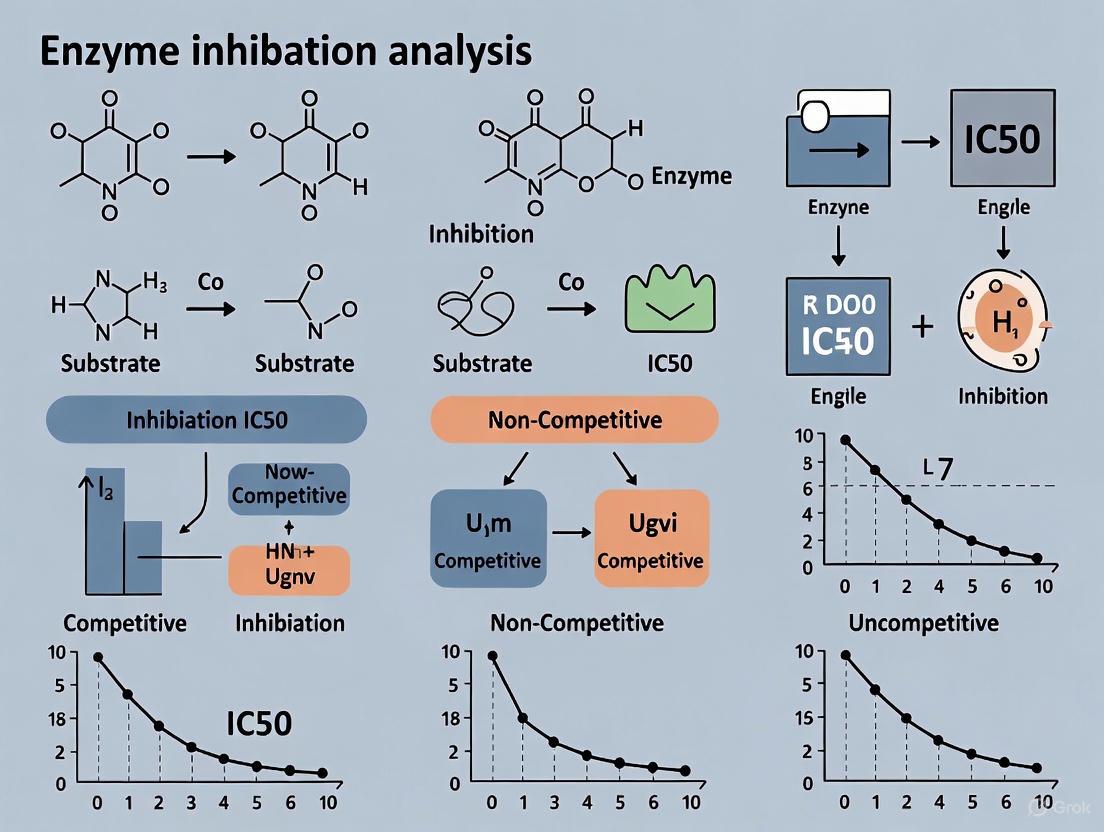

Workflow for Enzyme Inhibition Analysis

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for characterizing enzyme inhibitors, integrating traditional and modern approaches.

Advanced Methodologies in IC50 Estimation

Handling Time-Dependent Inhibition with Reversible Covalent Inhibitors

Many potent inhibitors, particularly reversible covalent inhibitors, show time-dependent behavior because they slowly establish a covalent modification equilibrium. This makes their IC50 values dependent on the incubation time [7].

Protocol for Time-Dependent IC50 Analysis [7]:

- Pre-incubation Time-Course: Pre-incubate the enzyme with a range of inhibitor concentrations for varying time periods (tpre).

- Residual Activity Measurement: Initiate the reaction with substrate and measure the initial velocity of product formation to determine the % activity remaining at each tpre and [I].

- IC50 Shift Analysis: Plot IC50 values against pre-incubation time. A decreasing IC50 with longer tpre confirms time-dependent inhibition.

- Global Fitting: Use a numerical modelling method, such as EPIC-CoRe, to fit the time-dependent IC50 data globally. This fitting estimates the fundamental constants:

- Ki: The initial non-covalent inhibition constant.

- k5/k6: The rate constants for the covalent bond formation and breakage.

- Ki^cov: The overall inhibition constant for the covalent equilibrium (calculated as Ki^cov = K_i / (1 + k5/k6)) [7].

Relationship Between Key Parameters

The table below summarizes the core definitions, interpretations, and dependencies of each key parameter.

| Parameter | Full Name | Definition | Key Interpretation | Primary Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration | Concentration of inhibitor that reduces biological activity by 50% [11] [12]. | Functional potency under specific assay conditions. | Substrate concentration, incubation time, enzyme concentration, assay conditions [11] [7]. |

| EC50 | Half-Maximal Effective Concentration | Concentration of an agonist that induces a 50% of its maximum response [11] [12]. | Functional potency for activators/agonists. | Assay conditions, cell type (for cellular assays). |

| Ki | Inhibition Constant | Dissociation constant for the enzyme-inhibitor complex; measures binding affinity [11] [13]. | Intrinsic binding strength between inhibitor and target. | Temperature, pH, inhibition mechanism (defines relationship to IC50) [11]. |

| LD50 | Median Lethal Dose | Single dose that causes death in 50% of a test animal population [14] [15]. | Acute toxicity, not therapeutic effect. | Route of administration, animal species, duration of observation [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in IC50/Ki Research |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Target | The primary macromolecule for in vitro inhibition studies. Essential for mechanistic studies and deriving Ki [4]. |

| Specific Substrate | The natural or synthetic molecule turned over by the enzyme. Its concentration is critical for determining inhibition modality and converting IC50 to Ki [11]. |

| Fluorescent/Chemiluminescent Probes | Enable continuous, high-throughput monitoring of enzyme activity for robust IC50 determination [16]. |

| Positive Control Inhibitors | Compounds with known potency and mechanism. Used to validate assay performance and as benchmarks [16]. |

| Tight-Binding Correction Equations | Mathematical corrections required when inhibitor affinity is so high that the concentration of enzyme significantly depletes the free inhibitor concentration, which would otherwise lead to inaccurate IC50 values [11]. |

For researchers in drug development, accurately assessing a compound's inhibitory potency is fundamental. The IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) is a frequently determined parameter from experimental binding assays, representing the concentration of an inhibitory ligand that reduces the biological activity of a target by half [17]. However, a significant limitation of the IC50 is its dependence on specific assay conditions, particularly substrate concentration [S], making cross-experiment comparisons problematic [17] [18].

The Cheng-Prusoff equation provides the critical theoretical relationship to convert the experimentally-derived, condition-dependent IC50 into the Ki (inhibitory constant), an absolute measure of binding affinity. The Ki is defined as the equilibrium concentration of an inhibitory ligand required to occupy 50% of the receptor sites in the absence of a competing substrate [17]. Unlike the IC50, the Ki is an intrinsic property of the inhibitor-target interaction, allowing for direct comparison of inhibitor potency across different experimental setups [17] [18].

The fundamental relationship is expressed as: Ki = IC50 / (1 + [S]/Km) [17]

Where:

- Ki: Inhibitory constant (absolute measure of affinity)

- IC50: Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (experimentally measured)

- [S]: Concentration of the substrate used in the binding assay

- Km: Affinity constant of the substrate (Michaelis constant), defined as the equilibrium concentration that results in substrate occupying 50% of the receptor sites in the absence of competition [17]

The equation corrects the apparent IC50 by accounting for the degree of substrate saturation in the assay, thereby revealing the true underlying affinity between the inhibitor and its target.

Figure 1: The experimental workflow for converting a measured IC50 value into a comparable Ki value using the Cheng-Prusoff equation, highlighting the essential assay parameters required for the calculation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between Ki and IC50?

The key difference lies in their dependency and interpretability. The following table summarizes the core distinctions:

| Parameter | Definition | Dependence | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | Operational concentration causing 50% activity inhibition under specific assay conditions [13]. | Depends on substrate concentration ([S]), enzyme concentration ([E]), and assay conditions [17] [13]. | Condition-dependent; cannot be directly compared unless all conditions are identical. |

| Ki | Equilibrium dissociation constant describing the inherent affinity between the inhibitor and the enzyme [13]. | An intrinsic property, independent of substrate and enzyme concentrations (for competitive inhibitors) [17] [13]. | Absolute measure of binding affinity; can be directly compared across different studies and assays. |

A critical operational distinction is that IC50 is always larger than Ki [13]. At 50% inhibition, the total inhibitor concentration ([I]t, i.e., IC50) equals the sum of the free inhibitor ([I]f, i.e., Ki) and the inhibitor bound to the enzyme ([I]b). Therefore, IC50 = [E]/2 + Ki, demonstrating its dependence on enzyme concentration [13].

When is it invalid to use the Cheng-Prusoff equation?

The Cheng-Prusoff relationship is a powerful tool but comes with specific assumptions. Its application is invalid or requires modification in these common scenarios:

- Non-competitive and Uncompetitive Inhibition: The standard equation is derived for competitive inhibition mechanics. Other inhibition types involve different binding sites and mechanisms that alter the relationship between IC50 and Ki.

- Irreversible and Mechanism-Based Inhibition (MBI): For inhibitors that permanently inactivate the enzyme (e.g., many cytochrome P450 inhibitors), the IC50 becomes time-dependent [19] [20]. The Cheng-Prusoff equation does not account for this. For MBIs, the inhibitory potential is more accurately described by the inhibition constant (KI) and the inactivation rate constant (kinact) [19] [20].

- Enzymes with Complex Mechanisms: The equation is designed for simple, single-substrate enzyme kinetics. It cannot be directly applied to bisubstrate enzymes (e.g., histone acetyltransferases like KAT8) without more elaborate kinetic evaluations [18].

- Non-Unity Slope of Agonist Curve: In functional assays, if the concentration-response curve of the agonist has a slope factor (K) significantly different from 1, applying the standard Cheng-Prusoff equation will yield an inaccurate Ki. Modified "power equations" that incorporate the slope function are required for accuracy [21].

Troubleshooting an unexpected Ki value should involve verifying these critical experimental parameters:

- Incorrect Km Value: The Km must be accurately determined under the exact same conditions (pH, temperature, buffer) as the IC50 assay. An inaccurate Km will directly propagate an error into the Ki calculation.

- Inaccurate Substrate Concentration ([S]): The Cheng-Prusoff correction is highly sensitive to [S]. Verify the stock concentration and dilution accuracy of your substrate.

- Misidentified Inhibition Mechanism: Applying the competitive Cheng-Prusoff equation to a non-competitive inhibitor will yield an incorrect Ki. Determine the mechanism of inhibition (e.g., via Dixon plot) before selecting the correct equation.

- Assay Non-Equilibrium: The equation assumes equilibrium conditions. If the inhibitor pre-incubation time is insufficient for the system to reach equilibrium, the measured IC50 will not be valid for Ki conversion.

- High Enzyme Concentration ([E]): The fundamental relationship IC50 = [E]/2 + Ki shows that if the enzyme concentration is too high, the IC50 will significantly overestimate the true Ki, leading to an underestimation of potency [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Pitfalls

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variability in calculated Ki | Inaccurate determination of the substrate Km. | Re-determine Km using a Michaelis-Menten experiment under identical assay conditions (pH, T, buffer). | [17] |

| IC50 decreases with pre-incubation time | Time-dependent inhibition, suggesting irreversible or mechanism-based inhibition. | Do not use Cheng-Prusoff. Characterize time-dependence and derive KI and kinact instead [19]. | [19] [20] |

| Ki values not comparable across different labs | Assay conditions (e.g., [S], pH, temperature) are not standardized. | Report all assay conditions in detail. Use Ki, not IC50, for cross-study comparisons. | [17] [22] |

| Curve slope in analysis is not unity | The agonist concentration-response curve has a Hill coefficient ≠ 1. | Use a modified power equation: KB = IC50 / [1 + (A/EC50)K] to account for the slope (K) [21]. | [21] |

| Inhibitor is potent in assay but weak in cells | The inhibitor may be a bisubstrate competitor; IC50 is misleading. | Perform full kinetic characterization to determine Ki for different enzyme forms (e.g., free vs. acetylated KAT8) [18]. | [18] |

Advanced Applications and Protocols

Protocol: Determining KI and kinact for Mechanism-Based Inhibitors

For time-dependent inhibitors, follow this established methodology [19] [20]:

- Time-Course Experiment: Measure IC50 values at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30 minutes) of pre-incubation of the enzyme with the inhibitor.

- Data Transformation: Plot the observed IC50 values against the pre-incubation time. You will observe a decrease in IC50 over time.

- Model Fitting: Fit the time-dependent IC50 data to a relevant kinetic model derived for mechanism-based inhibition to directly estimate the inactivation constant (KI) and the maximum inactivation rate (kinact).

- Validation: This method allows for the direct estimation of KI and kinact from IC50 values without the need for additional, more complex pre-incubation experiments, streamlining the screening process for irreversible inhibitors [19].

Case Study: Ki Determination for a Bisubstrate Enzyme (KAT8)

Research on KAT8, a histone acetyltransferase, highlights the limitations of IC50 and the necessity of full kinetic characterization for complex systems [18]:

- Fragment Screening: A screen identified 4-amino-1-naphthol as a hit with an IC50 of 9.7 ± 3.0 μM.

- Kinetic Analysis: Further investigation went beyond the IC50 to calculate the Ki values for the inhibitor binding to different enzymatic forms: the free enzyme (Ki1 = 2.6 μM) and the acetylated enzyme intermediate (Ki2 = 0.017 μM).

- Critical Insight: The Ki2 value revealed an exceptionally high potency for the acetylated enzyme that was entirely obscured by the IC50 value. This demonstrates that for bisubstrate enzymes, comprehensive kinetic characterization is crucial to uncover the true binding affinities and mechanism of inhibition, which cannot be captured by IC50 alone [18].

Figure 2: A decision tree for selecting the correct analytical path to convert an IC50 value into a meaningful inhibition constant, accounting for time-dependent inhibition, complex enzyme mechanisms, and non-ideal data slopes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Inhibition Assays | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Target | The biological macromolecule whose activity is being modulated. | Purity, stability, and concentration ([E]) must be precisely known and controlled [13] [22]. |

| Inhibitory Ligand | The test compound whose binding affinity (Ki) is being determined. | Solubility, stability in assay buffer, and absence of chemical reactivity are key. |

| Labeled Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme; often radiolabeled or fluorogenic for detection. | The substrate's Km must be predetermined. The concentration [S] used in the IC50 assay must be accurately known [17]. |

| Appropriate Buffer System | Maintains optimal pH and ionic strength for enzyme activity. | The pH and ionic composition can affect enzyme Km and inhibitor binding; must be standardized [22]. |

In enzyme inhibition analysis and drug discovery, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) is a fundamental metric used to quantify the potency of a substance. It represents the concentration of an inhibitor required to reduce a biological or biochemical process by half [1]. Traditionally reported in molar units (e.g., nM, μM), IC50 values can span several orders of magnitude, presenting challenges for data analysis and interpretation. The pIC50 is defined as the negative logarithm (base 10) of the IC50 molar concentration: pIC50 = -log10(IC50) [23] [1]. This transformation shifts potency measurement from an arithmetic to a logarithmic scale, which more accurately reflects the underlying biological phenomena. Dose-dependent inhibition is inherently a logarithmic process, making pIC50 a more natural and intuitive scale for reporting and analyzing potency data [23] [24]. This technical guide explores the advantages of this transformation and provides practical solutions for common experimental challenges.

Key Advantages and Troubleshooting FAQs

1FAQ: Why should I switch from IC50 to pIC50 for reporting my data?

Answer: Using pIC50 transforms your data to a scale that aligns with the logarithmic nature of concentration-response relationships, leading to clearer data presentation and more robust statistical analysis [23] [24].

- Simplified Communication: pIC50 allows you to represent potency using approximately two significant figures, covering both micromolar and nanomolar ranges efficiently (e.g., pIC50 6.0 for 1 μM, pIC50 9.0 for 1 nM). This eliminates mental gymnastics for your audience and helps them focus on the structure-activity relationships (SAR) [23].

- Intuitive Potency Ranking: On the pIC50 scale, higher values always indicate greater potency. This eliminates the potential confusion with IC50, where lower numerical values indicate higher potency [23] [25].

- Correct Averaging of Replicates: IC50 values should be averaged using the geometric mean, not the arithmetic mean, because they are exponential values. With pIC50, you can simply use the arithmetic mean because the data is already in a logarithmic space [23].

Table: Comparison of IC50 and pIC50 Values for Common Potency Ranges

| Potency | IC50 | pIC50 |

|---|---|---|

| Very High | 1 nM | 9.0 |

| High | 10 nM | 8.0 |

| Moderate | 100 nM | 7.0 |

| Low | 1 μM | 6.0 |

| Very Low | 10 μM | 5.0 |

2FAQ: How do I correctly average replicate IC50 measurements?

Problem: Incorrectly using arithmetic mean for IC50 values, which are log-normally distributed. Solution: Convert IC50 values to pIC50, calculate the arithmetic mean of the pIC50 values, and then convert back if needed [23].

Example: You have three replicate IC50 determinations: 1 nM (10⁻⁹ M), 10 nM (10⁻⁸ M), and 5 nM (~5×10⁻⁹ M).

- Incorrect Method: Arithmetic mean of IC50 = (1 + 10 + 5) / 3 = 5.33 nM

- Correct Method:

- Convert to pIC50: -log10(10⁻⁹) = 9.0, -log10(10⁻⁸) = 8.0, -log10(5×10⁻⁹) ≈ 8.3

- Calculate arithmetic mean: (9.0 + 8.0 + 8.3) / 3 ≈ 8.43

- Convert back to IC50 if needed: 10^(-8.43) ≈ 3.7 nM

Table: Correct vs. Incorrect Averaging of Replicate Data

| Method | Average IC50 | Average pIC50 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic Mean (IC50) | 5.33 nM | ~8.27 | Incorrect, statistically unsound |

| Geometric Mean (IC50) | ~3.7 nM | ~8.43 | Correct but requires complex calculation |

| Arithmetic Mean (pIC50) | ~3.7 nM | ~8.43 | Correct & mathematically simple |

3FAQ: How can logarithmic thinking improve my experimental design?

Problem: Poorly spaced dilution series points leading to clumped data on logarithmic plots. Solution: Design dilution series using logarithmic spacing for optimal data point distribution [23].

A common mistake is using half-decade dilutions like 1,000, 500, 100 nM, which appear evenly spaced on a linear scale but clump together on a logarithmic scale. The number halfway between 1 and 10 on a log scale is approximately 3 (10^0.5). A better dilution series is: 1,000 nM, 300 nM, 100 nM, 30 nM, 10 nM. This approach ensures points are evenly spaced when plotted on a log-scale concentration axis, providing more reliable data from the same number of experimental points [23].

Diagram: Impact of Dilution Series Design on Data Distribution

4FAQ: What are the implications of pIC50 for statistical analysis and data reliability?

Problem: Incorrect interpretation of confidence intervals and standard errors for IC50 values. Solution: Understand that curve-fitting software typically reports 95% confidence intervals for IC50 rather than standard error because standard error of an arithmetic value doesn't make sense with logarithmic data [23].

Attempting to calculate standard error on raw IC50 values can lead to biologically impossible results, such as negative IC50 values, when the error bars extend below zero. This occurs when applying linear statistical methods to exponential data. The pIC50 scale provides a more appropriate foundation for statistical testing and reliability reporting, as the values are normally distributed and conform better to the assumptions of parametric statistics [23].

Practical Implementation Guide

Conversion Formulas and Calculations

Essential conversion formulas:

- IC50 to pIC50: pIC50 = -log10(IC50) where IC50 is in molar concentration [23] [1]

- pIC50 to IC50: IC50 = 10^(-pIC50) [23]

- Handling different units: First convert IC50 to molar units, then apply the formula (e.g., for 10 nM: 10 nM = 10×10⁻⁹ M = 10⁻⁸ M; pIC50 = -log10(10⁻⁸) = 8.0)

Table: pIC50 Conversion Examples for Common Units

| IC50 Value | Units | Molar Concentration | pIC50 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nM | 1 × 10⁻⁹ M | 9.0 |

| 10 | nM | 1 × 10⁻⁸ M | 8.0 |

| 100 | nM | 1 × 10⁻⁷ M | 7.0 |

| 1 | μM | 1 × 10⁻⁶ M | 6.0 |

| 10 | μM | 1 × 10⁻⁵ M | 5.0 |

Data Presentation Guidelines

When presenting pIC50 data in publications or reports:

- Consistent Significant Figures: Report pIC50 values with one digit before and one after the decimal point (e.g., 6.3, 8.1) [23] [26]

- Table Formatting: Express all values with the same number of decimal places in a given table, with the standard error of the mean (SEM) having the same number of decimal places as the mean value [26]

- Context: Always indicate that values represent pIC50 and reference the original IC50 values in supplementary materials if needed for absolute concentration information

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Enzyme Inhibition Analysis

| Resource / Tool | Function / Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GOLD Docking Software | Protein-ligand docking to generate putative binding conformations | Used in computational prediction of enzyme inhibition [9] |

| MOPAC Program | Semiempirical quantum mechanics calculations for geometry optimization and energy prediction | Implements methods like PM6-ORG for protein-ligand interaction energies [9] |

| COSMO Solvent Model | Implicit solvation model accounting for desolvation penalties in binding | Robust and accurate method for modeling solvent effects [9] |

| 50-BOA Framework | Efficient estimation of inhibition constants using single inhibitor concentration >IC50 | Reduces experimental requirements by >75% while maintaining precision [4] |

| pIC50 Calculator | Instant conversion between IC50 and pIC50 values | Online tools available for quick transformations [25] |

Advanced Concepts: Integrating pIC50 in Modern Research

Computational Prediction of Enzyme Inhibition

Modern approaches to enzyme inhibition analysis combine computational and experimental methods. A typical workflow involves:

- Ligand Docking: Using programs like GOLD to generate multiple ligand conformations within the protein binding site [9]

- Geometry Optimization: Refining these structures using semiempirical quantum mechanics methods (e.g., PM6-ORG in MOPAC) [9]

- Energy Calculation: Predicting binding energies that correlate with experimental IC50 values [9]

- Validation: Comparing computational predictions with experimentally determined pIC50 values

Diagram: Computational Prediction of Enzyme Inhibition

Emerging Methodologies

Recent research has introduced innovative approaches to enzyme inhibition analysis:

- 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach): This methodology demonstrates that precise estimation of inhibition constants is possible using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50, substantially reducing experimental requirements while maintaining accuracy [4]

- Harmonic Mean Relationship: Incorporating the relationship between IC50 and inhibition constants into the fitting process improves precision even with reduced datasets [4]

- Error Landscape Analysis: Systematic analysis of estimation error landscapes helps identify optimal experimental designs for different inhibition types [4]

The adoption of pIC50 represents more than a simple unit conversion—it embodies a fundamental shift toward logarithmic thinking that aligns with the nature of dose-response relationships. This transformation enables clearer communication of structure-activity relationships, statistically sound data averaging, improved experimental design, and appropriate interpretation of data reliability. As enzyme inhibition analysis continues to evolve with new computational and experimental methodologies, the pIC50 scale provides a consistent, intuitive framework for reporting and comparing compound potency across studies and disciplines. By integrating pIC50 into routine practice, researchers can enhance the quality, reliability, and impact of their scientific communications in drug discovery and biochemical research.

For researchers in drug discovery and development, accurately determining the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) is a fundamental step in characterizing compound potency. However, the IC₅₀ is not an absolute value; it is highly dependent on the experimental conditions, particularly the mechanism of enzyme inhibition and the substrate concentration present in the assay [16] [27]. Misinterpretation of IC₅₀ data without understanding these relationships can lead to flawed conclusions about a compound's true efficacy and potential. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and foundational knowledge to help scientists navigate the complexities of enzyme inhibition analysis, ensuring more reliable and interpretable results for your research.

The IC₅₀ represents the concentration of an inhibitor required to reduce enzyme activity by 50% under a specific set of assay conditions [2]. It is an operational parameter, whereas the inhibition constant (Ki) is a thermodynamic constant defining the absolute binding affinity between the enzyme and the inhibitor [27]. The core challenge is that the relationship between IC₅₀ and Ki is governed by the inhibitor's mechanism of action.

The table below summarizes how the IC₅₀ is affected for different types of reversible inhibitors as substrate concentration [S] changes.

Table 1: Relationship Between Inhibition Type, Kinetic Parameters, and IC₅₀

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site | Effect on Km (app) | Effect on Vmax (app) | IC₅₀ vs. [S] Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Free Enzyme (E) only [28] | Increases [28] [29] | No change [28] [29] | IC₅₀ increases with increasing [S] [27]. |

| Non-Competitive | E and ES with equal affinity [29] | No change [29] | Decreases [29] | IC₅₀ is independent of [S] [27]. |

| Uncompetitive | Enzyme-Substrate Complex (ES) only [28] | Decreases [28] [29] | Decreases [28] [29] | IC₅₀ decreases with increasing [S] [27]. |

| Mixed | E and ES with different affinity [29] | Increases or Decreases [28] | Decreases [28] | Dependent on which constant (Ki or αKi) dominates; typically decreases with [S] [27]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for determining the mechanism of action based on enzyme kinetics data.

Experimental Protocols & Best Practices

Standard Protocol for IC₅₀ Determination

This protocol outlines the canonical method for determining IC₅₀ and gathering preliminary data on the mechanism of inhibition.

Preliminary IC₅₀ Estimation:

- Run an initial inhibition assay at a single substrate concentration, typically at or below the Km value for that substrate [28].

- Use a wide range of inhibitor concentrations (e.g., from pM to μM) in a dose-response curve.

- Fit the data to a four-parameter logistic model to calculate the initial IC₅₀ value [2].

Expanded Experimental Matrix for Mechanism:

- Design: Establish an experimental design using substrate concentrations at least at 0.2Km, Km, and 5Km [4]. For each substrate concentration, test a range of inhibitor concentrations, typically including 0, ¹/³ IC₅₀, IC₅₀, and 3x IC₅₀ (based on the initial estimate) [4].

- Measurement: For each combination of substrate and inhibitor concentration, measure the initial velocity of the enzymatic reaction [28] [4].

- Data Fitting: Fit the collective initial velocity data to the appropriate inhibition model (e.g., the general equation for mixed inhibition) to estimate the inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) and identify the inhibition type [4].

Advanced & Optimized Protocol (50-BOA)

Recent research suggests a more efficient framework called the IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) for estimating inhibition constants, which requires significantly fewer experiments [4].

Initial IC₅₀: Determine the IC₅₀ value at a single substrate concentration (e.g., [S] = Km) as in the preliminary step above.

Single Inhibitor Concentration Experiment:

- Using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the estimated IC₅₀, measure the initial reaction velocity across a range of substrate concentrations [4].

- Key Innovation: This method incorporates the harmonic mean relationship between IC₅₀ and the inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu) into the fitting process, allowing for precise estimation of these constants from a drastically reduced dataset [4].

Data Analysis: Use provided software packages (available in MATLAB and R) to fit the data from step 2 and directly estimate the inhibition constants and identify the inhibition type [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do I get different IC₅₀ values for the same inhibitor when I use different substrate concentrations in my assay? This is a classic indicator that your inhibitor is likely competitive. As shown in Table 1, for competitive inhibitors, the IC₅₀ increases as you increase the substrate concentration because the substrate and inhibitor are competing for the same binding site. A higher substrate concentration requires more inhibitor to achieve the same level of inhibition [27]. If your IC₅₀ is constant across substrate concentrations, it suggests a non-competitive mechanism.

Q2: My compound is a potent inhibitor in a biochemical assay (low IC₅₀) but shows no activity in a cell-based assay. What could be the reason? This common issue can have several causes, but the mechanism of inhibition can be a key factor. If the inhibitor is competitive with a substrate that is present at high intracellular concentrations, it may show poor cellular activity because the high substrate levels out-compete the inhibitor [28]. Other common reasons include poor cellular permeability, efflux by transporters, or extensive metabolic degradation [28].

Q3: When should I use Ki instead of IC₅₀ to report my results? You should use Ki when your goal is to report the true, intrinsic binding affinity of the inhibitor for the enzyme. The Ki is a constant that is independent of assay conditions [27]. The IC₅₀ is more appropriate when you want to report the functional potency under a specific, defined set of experimental conditions (e.g., "at a substrate concentration of 10 μM") [16] [27]. For publication and accurate comparison between compounds, determining the Ki is considered best practice.

Q4: What are "tight-binding" inhibitors and why are they problematic for IC₅₀ determination? Tight-binding inhibitors are characterized by an apparent affinity (Ki) that is near the concentration of enzyme ([E]T) present in the assay [28]. This leads to significant depletion of the free inhibitor concentration, violating a key assumption of standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics and causing the observed IC₅₀ to be higher than the true value. In these cases, the standard Cheng-Prusoff equation for converting IC₅₀ to Ki is invalid, and tight-binding equations must be applied for accurate analysis [28] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Materials for Enzyme Inhibition Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in Inhibition Analysis |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Target Enzyme | The protein of interest against which inhibitors are screened. Purity and activity are critical. |

| Natural Substrate(s) | Used to characterize the enzyme's natural kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) and for running inhibition assays under physiologically relevant conditions. |

| Inhibitor Compounds | The molecules being tested. Should be dissolved in a compatible solvent (e.g., DMSO) at a stock concentration that does not interfere with the assay. |

| Cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺, NADPH) | Essential for the activity of many enzymes. Their concentration must be optimized and kept constant. |

| Detection Reagents | Used to monitor product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates, coupled enzyme systems, fluorescent probes). |

| Buffers | To maintain a stable pH throughout the experiment. The buffer composition can sometimes affect inhibitor binding. |

Further Analysis

Once you have used IC₅₀ data to hypothesize an inhibition mechanism, the next step is to perform a full steady-state kinetic analysis. This involves measuring initial velocities at multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations and fitting the data to linearized plots (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk) or directly to nonlinear regression models of the Michaelis-Menten equation modified for different inhibition types [28]. This analysis allows for the determination of the true Ki value and confirms the binding mechanism. For more complex cases, such as time-dependent or irreversible inhibition, more specialized experimental designs are required [28].

Methods for IC50 Determination: From Experimental Assays to Computational Prediction

Enzyme inhibition analysis is a cornerstone of drug development, food processing, and fundamental biochemical research. It is essential for predicting drug-drug interactions, understanding metabolic pathways, and designing effective therapeutic agents. This technical support resource, framed within the context of advanced IC50 estimation research, provides scientists with practical troubleshooting guides and detailed methodologies to enhance the robustness and reliability of their enzyme inhibition assays.

Key Variables in Enzyme Inhibition Assays

The accuracy of an enzyme inhibition assay is highly dependent on several critical variables. Precise control and standardization of these parameters are fundamental to obtaining reproducible results.

Table 1: Key Variables and Their Optimal Ranges in Enzyme Inhibition Assays

| Variable | Impact on Assay | Recommended Range / Conditions | Rationale & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Directly affects reaction rate; instability causes high variability. | Typically 25°C or 37°C; must be stable within ±0.1°C. | A 1°C change can alter enzyme activity by 4-8% [30]. 37°C is physiological, but 25°C is often used for experimental convenience [22]. |

| pH | Affects enzyme and substrate charge/shape, impacting binding and catalysis. | Enzyme-specific optimal pH (often near pH 7.5 for mammalian enzymes) [22]. | Alters protonation states of key catalytic residues. Buffer type and ionic strength must be consistently controlled [30]. |

| Enzyme Concentration | Must be within the linear range for accurate velocity measurement. | Must be determined empirically; low enough to not deplete substrate. | High enzyme concentrations can lead to non-linear kinetics and rapid substrate depletion [22]. |

| Substrate Concentration ([S]) | Critical for defining the inhibition mechanism and calculating Ki. | Should span a range above and below the Km value [28]. | Running assays at or below the Km is common in screening, but full mechanistic studies require a wider range [28]. |

| Inhibitor Concentration ([I]) | Determines the dose-response relationship and IC50 calculation. | A single concentration >IC50 can be sufficient for precise Ki estimation [4]. | Traditional methods use multiple concentrations (e.g., 0, 1/3 IC50, IC50, 3 IC50), but new methods show this can introduce bias [4]. |

| Ionic Strength & Buffer | Can influence enzyme stability, activity, and inhibitor binding. | Must be optimized for the specific enzyme and be consistent [31]. | High salt can inhibit certain enzymes; purification methods can leave salts that carry over into the reaction [32]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

This section addresses specific problems researchers may encounter during inhibition assays, their likely causes, and evidence-based solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Enzyme Inhibition Assay Problems

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No or Low Activity | • Incorrect buffer or wrong pH• Enzyme denaturation• Inhibition by contaminants (e.g., salts from spin columns) [32]• Missing essential cofactor | • Verify buffer composition and pH.• Ensure proper enzyme storage and handling.• Clean up DNA/protein to remove contaminants; ensure reaction volume is not >25% DNA solution to dilute salts [32]. |

| Inconsistent Results (High Well-to-Well Variation) | • Temperature instability [30]• "Edge effects" in microplates due to evaporation [30]• Improper or inconsistent pipetting technique | • Use an instrument with superior temperature control.• Use a discrete analyzer with disposable cuvettes to avoid edge effects [30].• Calibrate pipettes and train users. |

| Unexpected Kinetics (Non-Michaelis-Menten) | • Time-dependent inhibition (slow binding) [28]• Tight-binding inhibition (where [I] ≈ [E]) [28]• Enzyme instability during the assay | • Pre-incubate enzyme and inhibitor; analyze progress curves for slow onset [28].• Use lower enzyme concentrations or account for tight-binding in data analysis [28].• Shorten assay duration or add stabilizing agents. |

| Inhibition Pattern Does Not Match Expectations | • Misidentification of inhibition mechanism.• Presence of "star activity" (altered specificity) in restriction enzymes [32].• Substrate depletion at low concentrations. | • Re-run assays with a wider range of [S] and [I]. Use models (e.g., mixed inhibition) that do not require prior mechanistic knowledge [4].• Use High-Fidelity (HF) enzymes; reduce units and incubation time [32].• Ensure initial velocity conditions where <10% substrate is consumed. |

| Extra Bands or Smears in Gel-Based Assays | • Restriction enzyme bound to DNA [32].• Nuclease contamination. | • Lower the number of enzyme units; add SDS (0.1-0.5%) to the loading dye [32].• Use fresh running buffer and agarose gel; clean up DNA [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the fundamental types of reversible enzyme inhibition, and how do I distinguish between them kinetically?

There are three primary types of reversible inhibition, classified by how the inhibitor interacts with the enzyme:

- Competitive Inhibition: The inhibitor (I) binds only to the free enzyme (E) at the active site, competing directly with the substrate (S). This increases the apparent K~M~ without changing V~max~ [28] [33].

- Noncompetitive Inhibition: The inhibitor binds to both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) with equal affinity at a site other than the active site. This decreases the apparent V~max~ without changing the K~M~ [28].

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: The inhibitor binds only to the ES complex. This decreases both the apparent V~max~ and the apparent K~M~ [28].

Mixed inhibition, where the inhibitor binds to both E and ES but with different affinities, is also common. The type of inhibition is distinguished by running a series of reactions with varying substrate concentrations in the presence of different fixed concentrations of inhibitor and analyzing the data on a Lineweaver-Burk (double-reciprocal) plot [34].

2. My compound is a potent inhibitor in a biochemical assay but shows no activity in cells. What could explain this discrepancy?

This common issue can have several causes:

- Cellular Permeability: The inhibitor may not effectively cross the cell membrane to reach its intracellular target [28].

- High Intracellular Substrate Concentration: If the inhibitor is competitive, a high local concentration of the natural substrate inside the cell can outcompete the inhibitor, reducing its apparent potency [28].

- Plasma Protein Binding: The inhibitor may be highly bound to proteins in the culture medium or serum, reducing the free concentration available to enter cells.

- Metabolic Instability: The inhibitor could be rapidly degraded or modified by cellular metabolism before it can act on the target.

3. What is IC50, and how does it relate to the inhibition constant (Ki)?

The IC50 (Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration) is the concentration of an inhibitor required to reduce the enzyme's activity by half under a specific set of experimental conditions (e.g., a fixed substrate concentration). It is an empirical measure of potency. The K~i~ (Inhibition Constant) is a thermodynamic constant representing the dissociation constant of the enzyme-inhibitor complex. It is independent of assay conditions. The relationship between IC50 and Ki depends on the mechanism of inhibition and the substrate concentration. For a competitive inhibitor, IC50 = K~i~ (1 + [S]/K~M~). Therefore, the Ki is always less than or equal to the IC50 [4].

4. New research suggests a simplified method for estimating inhibition constants. How does it work?

A recent advanced method, termed the 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach), demonstrates that precise and accurate estimation of inhibition constants (K~ic~ and K~iu~) for all types of inhibition (including mixed) is possible using data from a single inhibitor concentration that is greater than the IC50 value [4]. This approach incorporates the known relationship between IC50 and the inhibition constants into the fitting process. It can reduce the number of required experiments by over 75% compared to traditional multi-concentration designs, while also avoiding bias introduced by data from low inhibitor concentrations [4].

Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Inhibition Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Enzyme | The biological catalyst whose activity is being measured and inhibited. | Source (recombinant vs. native), purity, stability, and concentration are critical. Must be free of contaminants. |

| Specific Substrate | The molecule converted to product by the enzyme; its transformation is monitored. | Choose a substrate with high specificity for the target enzyme. Concentration must be carefully chosen relative to Km. |

| Inhibitor Compounds | The molecules being tested for their ability to reduce enzyme activity. | Solubility in assay buffer is crucial. DMSO is a common solvent, but final concentration must be kept low to not denature the enzyme. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides the optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for the enzyme. | Buffer type (e.g., phosphate, Tris), pH, and ionic strength must be optimized and controlled for each enzyme [31] [22]. |

| Cofactors / Cations | Essential for the activity of many enzymes (e.g., Mg2+ for kinases). | Required concentration must be determined and included in the assay mixture. |

| Detection Reagents | Used to monitor the reaction, e.g., chromogenic/fluorogenic probes, or reagents for coupled assays. | Must be compatible with the enzyme reaction and not inhibitory. The signal should be linear with product formation. |

Visualizing Inhibition Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Biochemical Mechanisms of Enzyme Inhibition

This diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanisms of reversible enzyme inhibition, showing the interactions between enzyme (E), substrate (S), and inhibitor (I).

Diagram 2: Optimized Experimental Workflow for IC50/Ki Estimation

This workflow outlines the streamlined 50-BOA protocol for efficient estimation of inhibition parameters, reducing experimental burden while maintaining precision [4].

Designing robust enzyme inhibition assays requires meticulous attention to biochemical variables, a deep understanding of inhibition kinetics, and awareness of common pitfalls. By applying the troubleshooting guidelines, optimized protocols, and theoretical frameworks presented here, researchers can significantly improve the quality and reliability of their data. The adoption of advanced methods like the 50-BOA can further streamline the process, accelerating research in drug discovery and biochemical analysis.

Core Concepts and Thesis Context

This guide details the practical application of Functional Antagonist Assays and Competition Binding Assays, two pivotal techniques in modern drug discovery. These assays are fundamental for quantifying compound efficacy and potency, particularly within enzyme inhibition analysis and IC50 estimation research. The accurate determination of a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) is a cornerstone in vitro measurement for advancing pharmacological candidates. Recent research underscores the critical relationship between IC50 values and fundamental inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu), with novel methodologies like the "IC50-Based Optimal Approach" (50-BOA) demonstrating that precise estimation of these constants is achievable with significantly streamlined experimental designs, reducing the required number of experiments by over 75% [4]. This guide integrates these advanced concepts with hands-on troubleshooting to empower researchers in generating robust, reproducible data.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a competitive binding assay and a functional antagonist assay?

- A1: A competitive binding assay directly measures the binding interaction between a ligand and its target, typically using a labeled analyte to compete with an unlabeled test compound for a limited number of binding sites [35]. The amount of bound labeled analyte is inversely proportional to the concentration of the competing unlabeled analyte [35]. In contrast, a functional antagonist assay measures the downstream biological consequence of that binding, such as the inhibition of an enzyme's ability to convert a substrate to a product, which is then used to calculate an IC50 value.

Q2: Why is my IC50 value inconsistent with reported literature values for the same compound?

- A2: Discrepancies in IC50 values often originate from methodological differences. Key factors include:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Differences in the preparation of 1 mM stock solutions are a primary reason for EC50/IC50 variations between labs [36].

- Assay Conditions: Parameters like Mg²⁺ concentration, NaCl concentration, GDP concentration (for GPCR assays), and membrane protein amount per well can drastically affect the signal and calculated potency [37].

- Enzyme Source and Form: The compound may be targeting an inactive form of the kinase in a cell-based assay, whereas a biochemical assay uses the active form [36].

- A2: Discrepancies in IC50 values often originate from methodological differences. Key factors include:

Q3: How does the Z'-factor relate to my assay window, and what is acceptable?

- A3: The Z'-factor is a key statistical parameter that assesses assay quality and robustness by incorporating both the assay window (the difference between the maximum and minimum signals) and the variability (standard deviation) of the data [36]. A large assay window with high noise can have a poorer Z'-factor than a small window with low noise. Assays with a Z'-factor > 0.5 are considered excellent and suitable for screening [37] [36]. The formula is:

Z' = 1 - [3*(SD_max) + 3*(SD_min)] / (Mean_max - Mean_min)[36].

- A3: The Z'-factor is a key statistical parameter that assesses assay quality and robustness by incorporating both the assay window (the difference between the maximum and minimum signals) and the variability (standard deviation) of the data [36]. A large assay window with high noise can have a poorer Z'-factor than a small window with low noise. Assays with a Z'-factor > 0.5 are considered excellent and suitable for screening [37] [36]. The formula is:

Troubleshooting Common Problems

The table below summarizes common issues, their potential causes, and solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Assay Performance Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No or Weak Signal | ||

| High Background Signal | ||

| High Variability Between Replicates | ||

| Poor Dynamic Range / No Assay Window |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Flow Cytometry-Based Functional Assay

This protocol is a general guide for assessing cellular functions like apoptosis, oxidative stress, and phagocytosis [39].

Solutions and Reagents: Phosphate buffer (PBS), staining buffer, blocking buffer, primary and secondary antibodies, antibody dilution buffer, fixative, permeabilizer, and washing buffer [39].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain a homogeneous single-cell suspension from adherent cells, non-adherent cells, or tissue samples. Gently mix the suspension, obtain a cell count, and resuspend cells in staining buffer to the appropriate concentration [39].

- Blocking: Incubate cells with a blocking agent to prevent non-specific antibody binding. No washing is required after this step to maintain blocking throughout the procedure [39].

- Functional Assay Staining: Select specific reagents (e.g., antibodies, fluorescent dyes) for the key cellular process you are investigating. Incubate cells with these reagents under optimized conditions (e.g., 4°C) [39].

- Detection and Analysis: Run samples on a flow cytometer, collect the data, and analyze it using appropriate flow cytometry data analysis software [39].

Protocol 2: GTPγS Binding Assay for GPCR Targets

This functional assay measures G-protein activation, a proximal event to GPCR activation, and is useful for differentiating agonists and antagonists [37].

Materials and Reagents:

- Membranes: Crude homogenates, plasma membrane preparations, or commercially available membranes [37].

- Assay Buffer: Typically contains HEPES or Tris HCl, NaCl, and MgCl₂ [37].

- Key Reagents: GTPγ³⁵S, WGA SPA beads or antibody-coated SPA beads, GDP, and detergents like NP-40 for antibody capture assays [37].

Procedure (Whole Membrane Assay using WGA SPA beads):

- Incubation: In a 96-well plate, incubate membranes, GTPγ³⁵S, and test compounds in a 200 µL reaction volume at room temperature for 30-60 minutes [37].

- Bead Addition: Add 50 µL per well of suspended WGA SPA beads (1 mg/well) [37].

- Capture and Counting: Seal the plates, incubate for one hour at room temperature, centrifuge at 200 x g, and count the plates in a suitable counter (e.g., Wallac microbeta) [37].

Critical Optimization Steps:

- Membrane and GDP: Determine the optimal membrane protein (5-50 µg/well) and GDP concentration (0-300 µM). Gi/o-coupled receptors require higher GDP than Gs or Gq-coupled receptors [37].

- Mg²⁺ and NaCl: Titrate Mg²⁺ (1-10 mM) and NaCl (0-200 mM) to achieve the best signal-to-noise ratio [37].

- Saponin: Explore the effect of saponin (3-100 µg/ml) to increase the signal, but note it may compromise the quality of concentration-response curves [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Functional and Binding Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | High-specificity binding components for detection and capture in immunoassays [35]. | Monoclonal: Offer unlimited, consistent supply and epitope specificity [35]. Polyclonal: A mixture of clones, but supply is limited [35]. |

| Labeled Analogs | Serve as the detectable competitor in competitive binding assays [35]. | Radioisotopes (e.g., I¹²⁵), chemiluminescent, colorimetric, or fluorometric labels. Nonisotopic signals are now common, offering biosafety and simpler automation [35]. |

| SPA Beads | Enable homogeneous, "no-wash" radioisotope-based assays by capturing membrane-bound radioactivity [37]. | Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) beads for whole membranes; Anti-species IgG beads for antibody capture assays [37]. |

| GTPγS | A non-hydrolyzable GTP analog used to measure GPCR activation by quantifying Gα subunit binding [37]. | Resistant to GTPase activity, allowing accumulation of measurable signal. Often used as [³⁵S]GTPγS [37]. |

| Detection Substrates | Generate a measurable signal (color, light, fluorescence) upon enzymatic reaction. | TMB (colorimetric) for ELISA; reagents for TR-FRET, Luminescence, or Fluorescence [36] [38]. |

| Blocking Agents | Reduce non-specific binding by saturating unoccupied sites on plates or cells. | BSA, Casein, Gelatin, or serum (FBS) [39] [38]. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Competitive Binding Assay Workflow

IC50 Estimation & Relationship to Inhibition Constants

G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) Signaling Pathway

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technology for studying biomolecular interactions in real-time. While traditionally used for determining binding affinity (KD) and kinetic parameters (ka and kd), SPR also provides a robust platform for the direct estimation of half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50). This is particularly valuable in pharmacological research and drug development for quantifying the potency of antagonist drugs. IC50 represents the concentration of an inhibitor required to reduce a specific biological or binding activity by half. This technical support center outlines how SPR can be leveraged for direct IC50 determination of individual ligand-receptor pairs, a method that offers molecular resolution superior to traditional whole-cell assay systems [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why use SPR for IC50 determination instead of traditional cell-based assays? Cell-based assays provide excellent potency information in a physiological context but can yield variable IC50 results depending on the experimental cell line used. More importantly, they often cannot differentiate an inhibitor's effect on a specific protein-protein interaction. SPR provides interaction-specific resolution, allowing you to determine the IC50 for a particular ligand-receptor pairing, free from the complexity of entire cell surfaces. This helps identify inhibitors that target specific complexes versus those that broadly inhibit multiple interactions [3].

2. What are the basic components needed for an SPR-based IC50 experiment? A typical setup requires:

- An SPR instrument (e.g., Biacore systems).

- A sensor chip (e.g., CM5 for covalent coupling, SA for streptavidin-biotin capture, NTA for His-tagged proteins).

- Purified ligand and analyte (e.g., a receptor-Fc fusion and its ligand).

- A high-affinity inhibitor.

- Suitable running and regeneration buffers [41] [42].

3. How is the IC50 value derived from SPR data? The IC50 is determined by pre-incubating a fixed concentration of the ligand (e.g., BMP-4) with a series of increasing concentrations of the inhibitor (e.g., Cerberus). These mixtures are then injected over the receptor-coated sensor surface. The reduction in the binding response is plotted against the inhibitor concentration. The resulting dose-response curve is fitted with a nonlinear regression model (e.g., a four-parameter logistic equation) to calculate the IC50, which is the concentration at which the binding signal is reduced by half [3].

4. Can I use a single inhibitor concentration to estimate IC50? Emerging methodologies, such as the "50-BOA" (IC50-Based Optimal Approach), suggest that precise estimation of inhibition constants might be possible using data from a single inhibitor concentration that is greater than the IC50. This can substantially reduce the number of experiments required. However, for a full and traditional IC50 curve, a dilution series of the inhibitor is recommended [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Reproducibility Between Experimental Runs

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent surface regeneration | Baseline does not return to original level; drifting response over multiple cycles. | Scout for optimal regeneration buffer (e.g., 10 mM glycine pH 2.0, 10 mM NaOH). Use short contact times and ensure it is mild enough to preserve ligand activity [41] [43]. |

| Variable ligand activity/immobilization | Fluctuating maximum response (Rmax) for the same analyte concentration. | Use the purest ligand possible. Standardize immobilization protocols. Regularly check ligand activity with a positive control injection [44] [45]. |

| Sample or buffer inconsistencies | High baseline drift or variable bulk shift. | Use high-quality, purified samples. Ensure buffer components are matched exactly between sample and running buffers [45]. |

Inaccurate or Skewed IC50 Values

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Mass transport limitation | Association phase is linear instead of curved; observed rate constant (kobs) changes with flow rate. | Use a high flow rate (e.g., 50-100 µL/min) and a low surface ligand density to enhance analyte diffusion [3] [41]. |

| Non-specific binding (NSB) | Significant binding signal on the reference flow cell; higher signal than theoretically expected. | Include a matched reference surface. Add blocking agents like BSA (0.1%) or mild detergents (e.g., 0.005% Tween 20) to the buffer [41] [43]. |

| Incomplete dissociation or analyte rebinding | Slow or incomplete dissociation, even after injection stop. | Optimize the regeneration step to fully remove bound analyte between cycles [41]. |

| Incorrect analyte concentration | Saturation at low inhibitor concentrations or a shallow response curve. | Ensure the analyte (ligand) concentration is around its Kd for the receptor. The inhibitor concentration series should span values below and above the expected IC50 [3] [4]. |

Low Binding Signal or Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low ligand immobilization level | Overall response (RU) is very low, even with high analyte concentration. | Increase the ligand concentration during immobilization. For covalent coupling, ensure the surface is properly activated [41] [45]. |

| Inactive ligand or analyte | No binding signal despite adequate surface density. | Check protein integrity and functionality. Consider using a different immobilization strategy (e.g., capture coupling) to improve orientation and activity [43]. |

| Suboptimal sensor chip choice | High non-specific binding or low immobilization efficiency. | Select a sensor chip compatible with your molecule. Use CM5 for general use, SA for biotinylated molecules, or NTA for His-tagged proteins [42] [45]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Direct IC50 Determination via In-Solution Competition

This protocol is adapted from research using SPR to determine the IC50 of Cerberus for inhibiting BMP-4 binding to its receptors [3].

Key Steps:

- Immobilize the Receptor: Capture the receptor (e.g., ActRIIA-Fc) onto a sensor chip (e.g., CMS) that has been pre-immobilized with an anti-Fc antibody. Aim for a low surface density (150-300 RU) to minimize mass transport effects and steric hindrance [3].

- Prepare Inhibitor Dilution Series: Serially dilute the inhibitor (e.g., Fc-free Cerberus) in the running buffer. A typical series might include 8-10 concentrations spanning several orders of magnitude.

- Pre-incubate Ligand and Inhibitor: Mix a fixed, known concentration of the ligand (e.g., 60 nM BMP-4) with each concentration of the inhibitor. Allow the mixture to reach equilibrium in solution.

- Inject Mixtures: Inject each pre-incubated mixture over the receptor surface and a reference surface using a high flow rate (e.g., 50 µL/min).

- Regenerate Surface: After each injection, use a regeneration buffer (e.g., MgCl2) to remove all bound material and prepare the surface for the next cycle.