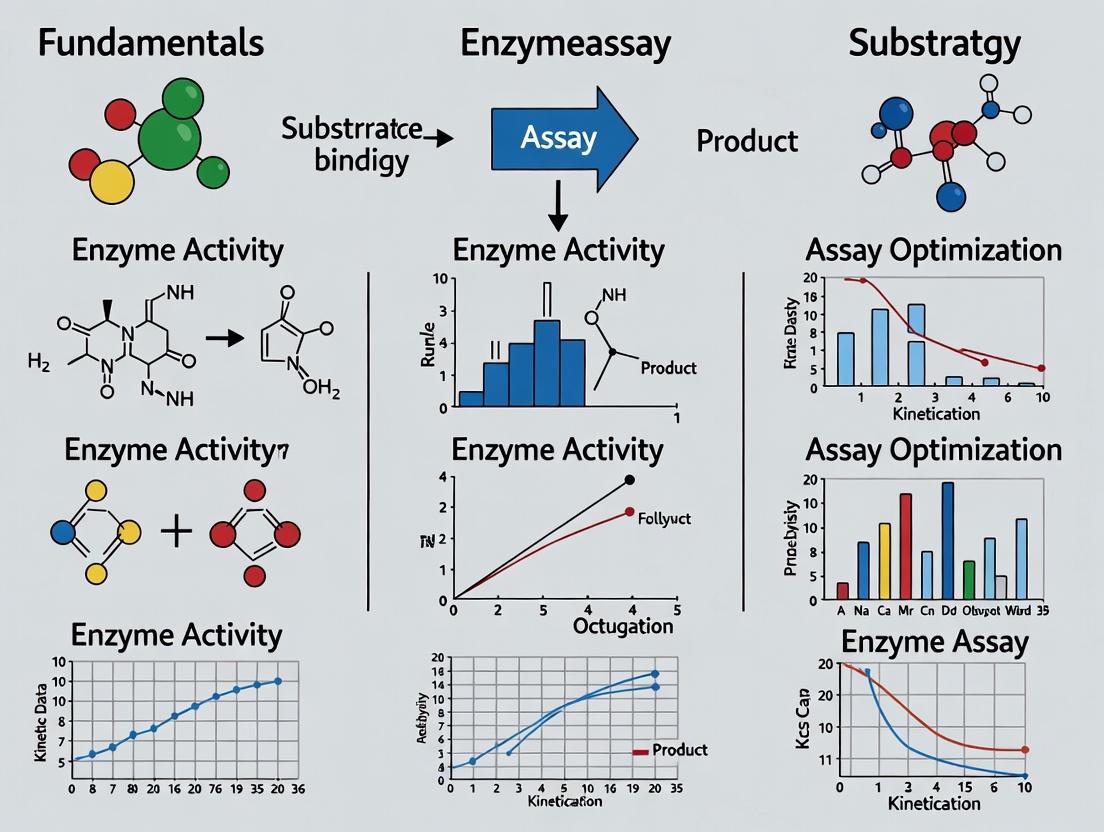

Mastering Enzyme Assay Design: Principles, Methods, and Optimization for Robust Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to enzyme assay design for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mastering Enzyme Assay Design: Principles, Methods, and Optimization for Robust Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to enzyme assay design for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of enzyme kinetics, the selection and application of modern assay methodologies, systematic troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and rigorous validation protocols. The content synthesizes current best practices to enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and reliability of enzymatic assays in drug discovery and biomedical research.

Building a Solid Foundation: Core Principles of Enzyme Kinetics and Assay Fundamentals

Fundamentals of Enzyme Catalysis

Enzymes are protein-based biological catalysts that dramatically accelerate chemical reactions essential for life by providing an alternative pathway with lower activation energy (Ea) [1]. They achieve this through precise molecular interactions within a specialized region called the active site, where substrate binding and conversion occur. The formation of an enzyme-substrate complex (ES) is a critical intermediate step [1]. Modern perspectives, supported by advanced computational models, emphasize that enzymes stabilize the high-energy transition state of a reaction, thereby reducing the energy barrier and increasing the reaction rate [2] [1].

Two primary models describe substrate binding: the lock and key model, which posits a rigid, pre-formed complementary fit, and the more widely accepted induced fit model, where the active site undergoes conformational changes upon substrate binding to optimize interactions [1]. Enzyme function is highly sensitive to environmental conditions; each enzyme has an optimal temperature and pH. Deviations can lead to denaturation, an irreversible loss of structure and function [1].

The Michaelis-Menten Kinetic Model

The Michaelis-Menten model provides a quantitative framework for understanding enzyme reaction rates under steady-state conditions [1] [3]. It describes how the initial reaction velocity (V₀) depends on substrate concentration ([S]).

The Kinetic Scheme and Equation

The basic model involves a reversible substrate binding step followed by an irreversible catalytic step [4]:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P

From this scheme, the fundamental Michaelis-Menten equation is derived:

V₀ = (Vₐₘₐₓ * [S]) / (Kₘ + [S])

Where:

- V₀: Initial reaction velocity.

- Vₘₐₓ: Maximum reaction velocity, achieved when all enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate.

- [S]: Substrate concentration.

- Kₘ: The Michaelis constant.

Key Parameters and Their Significance

- Vₘₐₓ: Represents the turnover capacity of the enzyme. It is directly proportional to the total enzyme concentration ([Eₜₒₜₐₗ]); doubling [Eₜₒₜₐₗ] doubles Vₘₐₓ [4].

- Kₘ: Defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vₘₐₓ. It is a composite constant:

Kₘ = (k꜀ₐₜ + kₒ꜀꜀) / kₒₙ, where kₒₙ and kₒ꜀꜀ are the rate constants for ES formation and dissociation, and k꜀ₐₜ is the catalytic rate constant [3] [4]. A lower Kₘ indicates higher apparent affinity of the enzyme for the substrate. - k꜀ₐₜ: The catalytic rate constant, also known as the turnover number. It indicates the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per active site per unit time [4].

- Catalytic Efficiency: Defined as the ratio

k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ. This single value describes how efficiently an enzyme operates at low substrate concentrations, combining both binding affinity (Kₘ) and catalytic power (k꜀ₐₜ) [4].

Table 1: Core Parameters of Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Velocity | Vₘₐₓ | The rate when all enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate. | Measures the enzyme's capacity for turnover. |

| Michaelis Constant | Kₘ | [S] at which V₀ = ½Vₘₐₓ. Kₘ = (k꜀ₐₜ + kₒ꜀꜀)/kₒₙ | Lower value indicates higher apparent substrate affinity. |

| Catalytic Rate Constant | k꜀ₐₜ | Rate constant for the product-forming step (ES → E + P). | Turnover number; measures catalytic speed. |

| Catalytic Efficiency | k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ | Ratio of the catalytic and Michaelis constants. | Higher value indicates a more efficient enzyme at low [S]. |

Graphical Analysis and Steady-State Assumptions

Plotting V₀ against [S] yields a rectangular hyperbola. The curve has two key regions: at low [S], velocity increases linearly (first-order kinetics); at high [S], velocity plateaus at Vₘₐₓ (zero-order kinetics) [1]. The Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/V₀ vs. 1/[S]) linearizes the relationship, allowing easier graphical determination of Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ and facilitating analysis of enzyme inhibition [1].

The model relies on several critical steady-state assumptions: 1) [S] >> [E], so free [S] ≈ total [S]; 2) The concentration of the ES complex is constant during the measured period; 3) The initial velocity is measured, where [P] ≈ 0 and the reverse reaction is negligible [4].

Enzyme Assay Design: A Practical Framework for Research

The determination of kinetic parameters (Kₘ, Vₘₐₓ, k꜀ₐₜ) is a cornerstone of enzyme assay design, providing critical data for characterizing natural enzymes, diagnosing diseases, and engineering novel biocatalysts [2] [1].

Core Principles of Kinetic Assays

A well-designed assay must ensure initial rate conditions are met. This involves using a short measurement time to minimize substrate depletion and product accumulation, which could trigger feedback inhibition or reverse reactions [4]. The assay must also maintain constant environmental factors (pH, temperature, ionic strength) and include appropriate controls to account for non-enzymatic background reactions.

Clinical and Diagnostic Applications

Plasma enzyme assays are vital diagnostic tools. Elevated or depressed levels of specific enzymes in the blood often indicate tissue damage or disease [1]. The kinetic parameters of these enzymes, including their sensitivity to inhibitors, form the basis for clinical tests.

Table 2: Examples of Diagnostic Enzymes and Clinical Relevance

| Enzyme | Primary Tissue Source | Clinical Significance of Elevated Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) | Heart, Liver, Erythrocytes | Myocardial infarction, liver disease, hemolysis [1]. |

| Alanine Transaminase (ALT) | Liver | Specific marker for hepatocellular injury (e.g., hepatitis) [1]. |

| Aspartate Transaminase (AST) | Liver, Heart, Muscle | Liver disease, myocardial infarction, muscle damage [1]. |

| Creatine Kinase (CK) | Heart (CK-MB), Muscle (CK-MM) | Myocardial infarction (CK-MB), muscular dystrophy [1]. |

| Amylase/Lipase | Pancreas | Acute pancreatitis [1]. |

Modern Frontiers: Computational Design and AI in Enzyme Engineering

Recent advances have fundamentally expanded the scope of enzyme assay design from mere characterization to the de novo creation of novel biocatalysts. This represents a paradigm shift within the field, driven by computational methods and artificial intelligence (AI) [2] [5].

From Directed Evolution to Generative AI

Directed evolution, a method of iteratively mutating and screening enzyme variants, has been highly successful for decades but is inherently limited to exploring local sequence space and is resource-intensive [2]. AI and machine learning (ML) are now revolutionizing the field by learning the "language" of protein structure and function from vast biological datasets, enabling the prediction and generation of novel, stable, and functional enzyme sequences [2] [6].

Breakthroughs in Computational Enzyme Design

A landmark 2025 study demonstrated a fully computational workflow to design enzymes for the Kemp elimination, a non-natural model reaction [7] [8]. The process involved assembling stable protein backbones from natural fragments, computationally optimizing active sites, and selecting designs for synthesis.

- Results: The best-performing design, with over 140 mutations from any known natural protein, achieved a catalytic efficiency (k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ) exceeding 10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹ and a k꜀ₐₜ of 30 s⁻¹, matching the performance of natural enzymes without iterative laboratory screening [7] [8].

- Significance: This proves that computational methods can now directly generate highly efficient, novel enzymes, bypassing traditional bottlenecks and allowing researchers to program catalysis for virtually any chemistry of interest [2] [7].

Table 3: Comparison of Enzyme Engineering Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Directed Evolution | Modern Computational/AI Design |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Mimic natural evolution: mutate, screen, select best variant [2]. | Generate and optimize enzyme structure in silico using physics & ML models [2] [6]. |

| Sequence Exploration | Local search around a parent sequence [2]. | Global search of vast sequence and fold space; can create entirely novel scaffolds [7] [6]. |

| Throughput & Resources | High-throughput screening required; labor and resource-intensive [2]. | Major design effort is computational; minimal experimental validation needed for top designs [7]. |

| Outcome | Improved variants of existing enzymes. | De novo enzymes for both natural and non-natural reactions [7] [6]. |

Essential Research Toolkit for Enzyme Kinetics and Assay Design

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

| Category / Item | Function in Enzyme Assay/Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biocatalyst of interest. Source can be native, recombinant, or computationally designed [7] [6]. | Purity, concentration ([Eₜₒₜₐₗ]), storage buffer, and stability are critical for reproducible kinetics. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) acted upon by the enzyme. | Purity, solubility, and preparation of a range of concentrations to span the kinetic curve (from < |

| Detection System | Measures the disappearance of substrate or appearance of product over time. | Must be specific, sensitive, and have a linear range suitable for initial rate measurement (e.g., spectrophotometry, fluorimetry, HPLC). |

| Buffer Components | Maintain constant pH and ionic strength. | Choose a buffer with appropriate pKa for the assay pH; ensure no inhibitory or activating effects on the enzyme. |

| Cofactors / Cations | Required for activity of many enzymes (e.g., NADH, Mg²⁺, ATP). | Must be added at saturating concentrations unless their kinetics are being specifically studied. |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Validate assay functionality. | Positive: enzyme + substrate. Negative: substrate only (no enzyme) or enzyme + inhibitor. |

| Computational Tools | For modern design & analysis (e.g., Rosetta, AlphaFold, MD simulations) [9] [6]. | Used for in silico enzyme design, stability prediction, and modeling reaction mechanisms prior to synthesis [7]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Setup | For directed evolution or testing design libraries [2]. | Microplates, liquid handlers, and plate readers to rapidly assay thousands of variants. |

The Michaelis-Menten model remains the essential quantitative foundation for understanding and characterizing enzyme catalysis. Its parameters (Kₘ, Vₘₐₓ, k꜀ₐₜ) are indispensable for diagnostic assay development and biocatalyst evaluation. Today, the field of enzyme assay design is intrinsically linked to a transformative new frontier: the computational and AI-driven creation of novel enzymes. The ability to design highly efficient, stable catalysts from scratch—validated through rigorous kinetic assays—opens unprecedented avenues in sustainable chemistry, drug discovery, and environmental remediation [2] [10] [6]. This synergy between foundational kinetic theory and cutting-edge computational power defines the modern paradigm of enzyme research and engineering.

Defining and Measuring Initial Velocity for Accurate Activity Assessment

Within the framework of a comprehensive thesis on the fundamentals of enzyme assay design research, the accurate definition and measurement of initial velocity (v₀) emerges as the foundational pillar. Enzymes, as biological catalysts, are paramount drug targets, with many therapeutics functioning through specific inhibition [11]. The development of robust, high-throughput screening (HTS) assays for drug discovery is entirely contingent upon precise kinetic characterization, which begins with v₀ [11]. This velocity represents the rate of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction measured under conditions where less than 10% of the substrate has been converted to product [11]. At this early stage, the substrate concentration is essentially constant, product inhibition is negligible, and the reverse reaction does not contribute to the measured rate [11] [12]. Consequently, v₀ provides the most accurate snapshot of an enzyme's inherent catalytic capacity, approximating its maximum potential velocity (Vmax) under the specified conditions [12]. Failure to establish and work within true initial velocity conditions invalidates steady-state kinetic assumptions, leading to erroneous calculations of key parameters like Km and V_max, and ultimately compromising the identification and characterization of inhibitors during structure-activity relationship (SAR) campaigns [11]. This guide details the theoretical principles, practical methodologies, and analytical frameworks for defining and measuring v₀, ensuring accurate and reproducible activity assessment in both basic research and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: The Kinetic Imperative for Initial Velocity

The mathematical treatment of enzyme kinetics, most commonly via the Michaelis-Menten model, is rigorously valid only under steady-state assumptions. A core tenet of this model is that the concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex remains constant over the measurement period. This condition holds true only when the reaction velocity is measured before significant changes in substrate and product concentrations occur.

The 10% Rule: The operational definition of v₀ is the linear rate observed when ≤10% of the initial substrate has been depleted [11]. This threshold minimizes confounding factors:

- Product Inhibition: Accumulating product can bind the enzyme, artificially slowing the observed rate.

- Substrate Depletion: As substrate is consumed, the driving force for the reaction decreases, causing the rate to fall non-linearly over time.

- Significant Reverse Reaction: With sufficient product, the reverse reaction (P → S) becomes measurable, reducing the net forward rate.

Consequences of Non-Linearity: Measuring outside the initial velocity regime has severe repercussions [11]:

- The reaction progress curve becomes non-linear with respect to enzyme concentration.

- The actual substrate concentration during the measurement period is unknown and decreasing.

- The derived kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) are incorrect and cannot be used for reliable comparison or inhibitor analysis.

- The assay sensitivity to detect inhibitors, particularly competitive ones, is dramatically reduced.

Table 1: Critical Parameters in Defining Initial Velocity

| Parameter | Definition & Ideal Condition | Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Depletion | ≤ 10% of initial [S] converted [11]. | Non-linear progress curves; invalid steady-state assumptions. |

| Enzyme Concentration | Must be low enough to maintain linearity over assay time course [11]. | Velocity is not proportional to [E]; substrate depletion is accelerated. |

| Detection System Linearity | Signal must be linear with product formation over the measured range [11]. | Under- or over-estimation of the true rate. |

| Time Course | Multiple early time points to establish a linear slope. | Risk of measuring an average rate instead of an instantaneous initial rate. |

Experimental Protocol: A Stepwise Guide to Establishing v₀

The following generalized protocol is essential for any enzyme assay development project aimed at generating reliable kinetic data.

3.1 Preliminary Reagent and Condition Optimization Before measuring v₀, ensure reagent quality and define optimal static conditions [11].

- Enzyme: Verify purity, specific activity, and stability under assay conditions (temperature, buffer). Establish lot-to-lot consistency [11].

- Substrate: Use natural or validated surrogate substrates. Determine solubility and stability in the assay buffer [11].

- Buffer & Cofactors: Optimize pH, ionic strength, and essential cofactor concentrations to maximize activity and stability. Include necessary additives (e.g., DTT, BSA).

- Detection System Validation: Perform a signal calibration curve using known concentrations of product (or depleted substrate). Critically, define the linear dynamic range of the detection instrument [11]. The assay signal for the 10% conversion point must fall within this linear range.

3.2 Defining the Initial Velocity Time Window This is an iterative, empirical process.

- Prepare a master reaction mix containing buffer, cofactors, and substrate at the desired concentration (typically near or below the anticipated K_m).

- Initiate multiple identical reactions by adding a fixed concentration of enzyme.

- Measure the signal (product formation or substrate loss) at multiple early time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 300 seconds).

- Plot signal versus time. The initial linear portion of the curve defines the v₀ time window.

- Enzyme Titration: If the progress curve curves downward too quickly (e.g., >10% depletion within the first few points), repeat the experiment with a lower enzyme concentration [11]. The goal is to identify an enzyme concentration that yields a linear signal increase for a practical assay duration.

3.3 Protocol for a Standard v₀ Determination Experiment

- Objective: To measure the initial velocity at a single substrate concentration.

- Controls:

- Negative Control 1: All components except enzyme (to measure background signal from substrate).

- Negative Control 2: All components except substrate (to measure background signal from enzyme/contaminants).

- Positive Control: A known active inhibitor or a reaction with saturating substrate, if known.

- Procedure:

- In a microplate or cuvette, add assay buffer, cofactors, and substrate.

- Equilibrate all components to the assay temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C).

- Initiate the reaction by adding enzyme and mix rapidly and thoroughly.

- Immediately begin monitoring the signal (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence) kinetically.

- Record data points at intervals spanning the pre-determined linear time window.

- For each reaction, calculate v₀ as the slope of the linear regression fit to the time course data within the linear window, subtracting the appropriate background control signal.

Diagram 1: Workflow for establishing the initial velocity time window.

Data Analysis: From v₀ to Kinetic Constants

Once a reliable v₀ measurement is established at a single substrate concentration, the next critical phase is to determine the Michaelis constant (Km) and maximum velocity (Vmax) by measuring v₀ across a range of substrate concentrations.

4.1 Saturation Curve Experiment

- Prepare a dilution series of substrate, typically spanning 0.2 to 5.0 times the estimated K_m (e.g., 8 or more concentrations) [11].

- For each substrate concentration [S], perform the v₀ assay as defined in Section 3.3.

- Plot v₀ (y-axis) versus [S] (x-axis). This yields a rectangular hyperbola described by the Michaelis-Menten equation: v₀ = (Vmax [S]) / (Km + [S]).

4.2 Determining Km and Vmax Non-linear regression fitting of the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation is the most accurate method. For competitive inhibitor screening, it is essential to run subsequent inhibition assays with the substrate concentration set at or below its Km value [11]. Using [S] >> Km makes identifying competitive inhibitors difficult.

Table 2: Key Outputs from Initial Velocity Analysis and Their Utility

| Output | Description | Application in Assay Design & Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Velocity (v₀) | Linear reaction rate under defined conditions. | Primary readout for all enzyme activity assessments. |

| Michaelis Constant (K_m) | Substrate concentration at half V_max. Reflects enzyme affinity for substrate. | Used to set the substrate concentration for inhibitor screens (at or below K_m) [11]. |

| Maximum Velocity (V_max) | Theoretical maximum rate when enzyme is fully saturated. | Defines the assay window; used to calculate enzyme turnover number (k_cat). |

| Linear Time Window | Duration over which product formation is linear. | Defines the allowed measurement period for HTS and SAR assays. |

| Optimal [Enzyme] | Enzyme concentration yielding linear progress. | Standardized parameter for all subsequent assays to ensure proportionality. |

Diagram 2: Pathway from initial velocity data to kinetic constants.

Advanced Considerations and the Scientist's Toolkit

5.1 Special Cases: Multi-Substrate Reactions For kinases, ATPases, and other multi-substrate enzymes, determining v₀ requires careful design. The recommended approach is to determine the K_m for one substrate (e.g., ATP) while holding the other(s) (e.g., peptide/protein) at a saturating concentration [11]. Ideally, kinetic parameters for all substrates should be determined interactively to identify any cooperativity.

5.2 Common Pitfalls and Troubleshooting

- Loss of Linearity: If linearity is lost during an established assay, test enzyme stability and reagent integrity. The enzyme may be denaturing over the course of the reaction [11].

- "Unphysiological" Km: A Km value vastly higher than in vivo concentrations may indicate missing cellular activators or suboptimal in vitro assay conditions [11].

- Signal-to-Noise: Ensure the signal from 10% substrate conversion is significantly above the background noise of the detection system.

5.3 The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Initial Velocity Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function & Criticality | Notes for Quality Assurance |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Enzyme | The biological catalyst. Source, purity, and specific activity are paramount [11]. | Verify absence of contaminating activities. Aliquot and store stably. Determine specific activity for each lot. |

| Native or Surrogate Substrate | The molecule transformed in the reaction. Must be recognized by the enzyme [11]. | Confirm chemical/sequence purity. Ensure adequate solubility in assay buffer. |

| Cofactors / Essential Ions | Required for enzymatic activity (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases, NADH for dehydrogenases). | Titrate to determine optimal concentration. Include in all reaction mixes. |

| Optimized Assay Buffer | Provides stable pH and ionic environment. May contain stabilizing agents (BSA, DTT). | Pre-test enzyme stability in buffer. Use a buffer with adequate capacity. |

| Control Inhibitors | Known active compounds for assay validation. | Used to confirm assay sensitivity and dynamic range for inhibition. |

| Detection Reagents/Probes | Enable measurement of product formation/substrate loss (e.g., fluorescent dye, coupled enzyme). | Must be validated for linearity and lack of interference with the primary reaction [11]. |

| Inactive Enzyme Mutant | A catalytically dead variant purified identically to the wild-type [11]. | Serves as a critical control for non-specific signal or background binding events. |

Diagram 3: Logical impact of accurate v₀ measurement on drug discovery.

The rigorous measurement of initial velocity is not merely a preliminary step but the core kinetic constraint that governs all subsequent stages of enzyme assay design. It is the critical link between the biochemical reality of the enzyme's mechanism and the mathematical models used to quantify its activity and inhibition. A thesis on assay design fundamentals must, therefore, position v₀ determination as a non-negotiable, iterative experimental phase. The protocols and considerations outlined here provide a blueprint for researchers to generate kinetically valid, reproducible, and physiologically relevant data. By anchoring assay development in true initial velocity measurements, scientists ensure that high-throughput screens for drug discovery are built on a solid kinetic foundation, maximizing the probability of identifying genuine, potent, and mechanistically well-characterized therapeutic inhibitors. This disciplined approach transforms enzyme assays from simple activity readouts into powerful engines for quantitative biology and rational drug design.

The rigorous characterization of enzyme kinetic parameters—the Michaelis constant (Kₘ), maximum velocity (Vmax), and catalytic turnover number (kcat)—forms the quantitative bedrock of modern enzymology and its applications in drug discovery, diagnostics, and fundamental biochemistry [13] [14]. This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on the fundamentals of enzyme assay design research, provides an in-depth technical guide for determining these core parameters. The precision of these measurements dictates the success of downstream applications, from high-throughput screening (HTS) for novel therapeutics to ensuring the accuracy of point-of-care biosensors [15] [16]. A well-designed kinetic assay transcends mere activity measurement; it yields validated, reproducible parameters that describe substrate affinity, catalytic proficiency, and intrinsic efficiency, enabling robust comparisons between enzyme variants, substrates, and inhibitor modalities [17] [14].

Theoretical Foundations: Michaelis-Menten Kinetics and Parameter Definitions

The Michaelis-Menten model provides the fundamental framework for understanding the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity [13] [1]. It describes a reversible enzyme-substrate (ES) complex formation followed by an irreversible catalytic step to yield product (P) and free enzyme (E) [14].

Core Kinetic Parameters:

- Vmax (Maximum Velocity): The theoretical maximum rate of the reaction when all enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate [13] [18]. It is a function of the total concentration of active enzyme ([E₀]) and the intrinsic turnover rate.

- Kₘ (Michaelis Constant): The substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax [13] [1]. Operationally, it reflects the affinity between the enzyme and substrate: a lower Kₘ indicates a higher apparent affinity, meaning the enzyme achieves half its maximum velocity at a lower substrate concentration [13].

- kcat (Turnover Number): The number of substrate molecules converted to product per active site per unit time under saturating substrate conditions [18]. It is calculated as kcat = Vmax / [E₀], where [E₀] is the molar concentration of active enzyme sites [19]. It defines the catalytic rate constant of the rate-limiting step.

- Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Kₘ): The specificity constant, which describes an enzyme's overall proficiency for a substrate [13] [18]. This ratio accounts for both binding affinity (Kₘ) and catalytic rate (kcat). Its upper limit (≈10⁸ – 10⁹ M⁻¹s⁻¹) is set by the diffusion rate of the substrate to the enzyme [18].

Experimental Determination: A Stepwise Protocol

Accurate determination of Kₘ and Vmax requires meticulous assay development to ensure measurements reflect the true initial velocity of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction [14].

Phase 1: Establishing Initial Velocity Conditions

The critical first step is to define the time window and enzyme concentration where product formation is linear with time, ensuring less than ~10% substrate depletion [14]. Non-linearity can arise from substrate depletion, product inhibition, or enzyme instability [20] [14].

- Procedure: Using a single, intermediate substrate concentration, run the reaction with 3-4 different enzyme concentrations. Measure product formation at multiple time points (e.g., every 30 seconds for 10-15 minutes) [17] [14].

- Analysis: Plot product concentration versus time for each enzyme level. Identify the linear phase where the slope (velocity) is constant. The selected assay duration must fall within this linear window for all subsequent experiments. Doubling the enzyme concentration should double the initial velocity (V₀), confirming the assay is enzyme-limited [17].

Phase 2: Generating the Saturation Curve

With linear conditions defined, the dependence of initial velocity on substrate concentration is measured.

- Procedure: Prepare a series of substrate concentrations, typically spanning a range from 0.2 to 5 times the estimated Kₘ [14]. Use at least 8 different concentrations in triplicate for reliable fitting [14]. Maintain a constant, optimized enzyme concentration within the linear range determined in Phase 1.

- Controls: Include a negative control (no enzyme) to subtract background signal and a positive control if available [17].

- Measurement: For each substrate concentration, measure the initial rate of product formation (V₀) using the predetermined linear time window.

Data Analysis and Parameter Extraction

The initial velocity (V₀) data versus substrate concentration ([S]) is fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to extract Kₘ and Vmax. Non-linear regression is the preferred, most accurate method [19]. Historically, linear transformations were used but can distort error distribution [18].

- Non-Linear Regression: Directly fit the data to the equation: V₀ = (Vmax * [S]) / (Kₘ + [S]). Software like GraphPad Prism performs this fitting, providing best-fit values and confidence intervals for Kₘ and Vmax [19].

- Calculating kcat: Determine the molar concentration of active enzyme ([E₀]) in the assay using methods like quantitative amino acid analysis or active site titration. Then calculate: kcat (s⁻¹) = Vmax (M s⁻¹) / [E₀] (M) [19]. If [E₀] is unknown, only Vmax can be reported.

- Linear Transformations (for validation):

Optimized Assay Formats and the Scientist's Toolkit

The choice of detection technology is paramount for a robust, sensitive, and reproducible assay [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Enzyme Assay Formats

Assay Format Readout Principle Advantages Disadvantages Best Use Case Fluorescence Fluorescent probe intensity, polarization (FP), or TR-FRET High sensitivity, HTS-compatible, homogeneous (mix-and-read) formats available [16]. Potential interference from fluorescent compounds [16]. Primary HTS, kinetic studies for many enzyme classes [16]. Luminescence Light emission (e.g., luciferase-coupled) Very high sensitivity, broad dynamic range [16]. Susceptible to interference from luciferase inhibitors; coupling can introduce artifacts [16]. ATP/NAD(P)H-dependent enzymes, kinases [16]. Absorbance (Colorimetric) Change in optical density (color) Simple, inexpensive, robust [16]. Lower sensitivity, not ideal for miniaturized HTS [16]. Preliminary validation, educational assays, endpoint analysis [16]. Label-Free (e.g., SPR, ITC) Mass or heat change No labeling required; provides direct binding/thermodynamic data [16]. Low throughput; requires specialized instrumentation [16]. Mechanistic studies, binding constant determination [16]. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Item Function & Importance High-Purity, Characterized Enzyme The target protein. Purity (>95%) and verified activity (specific activity, U/mg) are critical for accurate [E₀] and kcat calculation [14]. Native or Surrogate Substrate The molecule converted by the enzyme. Chemical purity and a reliable supply are essential. The Kₘ can differ between natural and artificial substrates [14]. Optimized Assay Buffer Maintains pH, ionic strength, and provides necessary cofactors (Mg²⁺, ATP, etc.). Buffer components can significantly affect enzyme activity and stability [14] [21]. Detection Reagents/Probes Molecules that enable quantification of product or substrate. Examples include fluorogenic substrates, luciferase/luciferin systems, or chromogenic agents. Must have a linear response in the detection range [20] [14]. Reference Inhibitor/Control A known modulator of enzyme activity (e.g., a well-characterized competitive inhibitor). Serves as a critical positive control to validate assay performance and sensitivity [14]. Microplates & Detection Instrument Assay vessel (96-, 384-well) and compatible reader (plate reader, potentiostat). The instrument's linear detection range must be established to avoid signal saturation [20] [14].

Advanced Considerations and Applications

Applying Parameters in Drug Discovery

In inhibitor screening, the Kₘ value dictates the optimal substrate concentration. To sensitively identify competitive inhibitors, assays are run with [S] at or below the Kₘ [14]. Under these conditions, a competitive inhibitor will cause a pronounced decrease in reaction velocity. Vmax and kcat remain unchanged for a pure competitive inhibitor, while Kₘ appears to increase [1].

Applying Parameters in Diagnostic Biosensor Design

Kinetic parameters directly dictate the performance of enzyme-based biosensors, such as glucose monitors. The enzyme's Kₘ must be matched to the expected analyte concentration range in the sample [15]. An enzyme with a Kₘ far below the physiological range will saturate quickly, leading to a compressed, non-linear response at high analyte levels and inaccurate readings [15]. Conversely, kcat influences the response time and signal strength [15].

The precise determination of Kₘ, Vmax, and kcat is a cornerstone of quantitative enzymology. It demands a methodical, two-phase experimental approach: first, rigorously establishing initial velocity conditions, and second, generating a high-quality substrate saturation curve. Subsequent analysis via non-linear regression yields the fundamental parameters that describe enzyme function. These values are not merely academic; they are critical design inputs for developing robust high-throughput screening assays in drug discovery and for engineering accurate, reliable diagnostic devices. Mastery of these principles and protocols is therefore essential for researchers advancing the frontiers of biotechnology, therapeutic development, and biochemical analysis.

Visual Summaries

Workflow for Determining Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

Methods for Analyzing Kinetic Data to Extract Parameters

Applying Kinetic Parameters in Research & Development

The Critical Role of Enzyme and Substrate Concentration in Assay Design

Within the fundamental framework of enzyme assay design research, the precise control and understanding of enzyme and substrate concentrations are not merely technical details but foundational pillars that dictate the validity, reproducibility, and biological relevance of kinetic data. Enzymes, as potent and specific biological catalysts, are central targets in drug discovery, with many therapeutics functioning as inhibitors [14] [22]. The development of robust assays for high-throughput screening (HTS) and mechanistic study, therefore, hinges on a rigorous application of kinetic principles. This guide details how the deliberate manipulation of enzyme and substrate concentrations establishes the essential conditions for meaningful measurement—specifically, the initial velocity conditions under which the Michaelis-Menten model holds [14]. Failure to optimize these parameters risks generating data obscured by artifacts such as substrate depletion, product inhibition, or instrument nonlinearity, ultimately compromising the identification and characterization of potential drug candidates [14] [20].

Foundational Kinetic Principles Governing Concentration

The relationship between reaction velocity (v), substrate concentration ([S]), and enzyme concentration ([E]) is quantitatively described by the Michaelis-Menten equation. This model establishes the critical kinetic parameters that guide assay design [14]:

- Vmax: The maximum reaction velocity, achieved when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate. It is directly proportional to the total concentration of active enzyme (*Vmax = kcat [E]total*).

- Km (Michaelis Constant): The substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of *Vmax. It represents the enzyme's apparent affinity for the substrate; a lower *K_m indicates higher affinity.

For an assay to accurately reflect the enzyme's inherent properties, it must be conducted under initial velocity conditions, where less than 10% of the substrate has been converted to product. Under these conditions, [S] is essentially constant, and complicating factors like reverse reaction or product inhibition are negligible [14]. The kinetic order of the reaction relative to substrate and enzyme is paramount:

- Zero-Order Kinetics (with respect to substrate): When [S] >> K_m, the enzyme active sites are saturated, and the reaction velocity is maximal and independent of [S]. The velocity depends solely and linearly on [E]. This is the ideal condition for measuring enzyme concentration or activity [23].

- First-Order Kinetics (with respect to substrate): When [S] << K_m, velocity is directly proportional to [S]. The reaction is highly sensitive to changes in substrate concentration [14].

The catalytic power of an enzyme is defined by its turnover number (k_cat), the number of substrate molecules converted to product per active site per unit time. This value varies enormously between enzymes [22].

Table 1: Turnover Numbers of Representative Enzymes [22]

| Enzyme | Turnover Number (k_cat) (s⁻¹) | Catalytic Proficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Carbonic anhydrase | 600,000 | Extremely high |

| Catalase | 93,000 | Very high |

| β-Galactosidase | 200 | Moderate |

| Chymotrypsin | 100 | Moderate |

| Tyrosinase | 1 | Low |

The Strategic Role of Substrate Concentration ([S])

The choice of substrate concentration is a strategic decision that determines the assay's sensitivity to different types of inhibitors and its faithfulness to physiological conditions.

- For Inhibitor Identification & Characterization: To sensitively detect competitive inhibitors, which compete with the substrate for the active site, assays must be run with [S] at or below the K_m value. At this concentration, the enzyme is not saturated, and the velocity is sensitive to changes in available active sites. Using [S] >> K_m makes the assay insensitive to competitive inhibition, potentially causing false negatives in screening campaigns [14]. For kinases, this principle applies to both the peptide/protein substrate and the co-substrate ATP, necessitating separate K_m determinations for each [14].

- For Activity Measurement & High-Throughput Screening (HTS): While [S] near K_m is ideal for inhibition studies, HTS assays often prioritize robustness and signal magnitude. Therefore, a substrate concentration that provides a strong, stable signal (often higher than K_m) may be used, with the critical caveat that hits must be later retested under more sensitive ([S]~K_m) conditions to identify mechanism [14].

- Practical Determination of K_m and V_max: These parameters are determined empirically by measuring initial velocities across a wide range of substrate concentrations (typically 0.2–5.0 x K_m). The data is fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation or its linear transformations (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk) [14].

Table 2: Strategic Implications of Substrate Concentration in Assay Design

| [S] relative to K_m | Reaction Order | Utility in Assay Design | Primary Limiting Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| [S] >> K_m (e.g., 10x K_m) | Zero-order in [S] | Measuring total active enzyme concentration; HTS for signal strength. | Enzyme concentration ([E]) |

| [S] = K_m | Mixed-order | Ideal for measuring competitive inhibitor potency (IC₅₀, K_i). | Both [E] and [S] |

| [S] << K_m | First-order in [S] | Studying enzyme affinity; very sensitive to [S] changes. | Substrate concentration ([S]) |

The Strategic Role of Enzyme Concentration ([E])

The amount of enzyme used dictates the assay's linear range, duration, and susceptibility to interference.

- Establishing the Linear Range: The core requirement is that the measured initial velocity must be directly proportional to the amount of enzyme added. This linear relationship holds only under zero-order conditions (with respect to substrate) and before significant substrate depletion occurs [23] [20]. To establish this, a progress curve experiment is essential: product formation is monitored over time using 3-4 different enzyme concentrations. The goal is to identify an enzyme concentration that yields a linear progress curve for the desired assay duration [14].

- Controlling Assay Time and Signal: The enzyme concentration directly sets the rate of product formation. For a fixed assay time, too much enzyme will deplete the substrate prematurely, causing the signal to plateau and introducing nonlinearity. Too little enzyme will produce a signal too weak to measure accurately above background [14] [20]. The enzyme must also be stable over the course of the reaction; loss of activity will cause progress curves to plateau at different maximum product levels for different starting [E] [14].

- Quantifying Enzyme Activity: Enzyme quantity is expressed in Units (U), where 1 U is typically defined as the amount that catalyzes the conversion of 1 μmol of substrate per minute under standard conditions. Specific activity (U/mg of protein) is a critical metric for assessing enzyme purity and lot-to-lot consistency [20] [24].

Diagram 1: Assay Optimization Workflow

Advanced Considerations and Modern Methodologies

Beyond foundational kinetics, modern assay design incorporates advanced detection methods and next-generation engineering.

- Detection Methodologies and Linearity: The choice of detection system (spectrophotometric, fluorometric, luminescent) must align with the assay's kinetic requirements. Crucially, the detection system's linear range must exceed the range of product generated during the initial velocity period. A system that saturates will distort the kinetic measurements [14]. Coupled assays, where the product of the primary reaction is converted by a second enzyme to a detectable signal, are common but require the coupling system to be non-rate-limiting [24].

- Contemporary Trends in Enzyme Engineering: Recent advances focus on regulating enzyme activity through computational design and directed evolution. Machine learning-driven protein engineering, combined with high-throughput kinetic assays, enables the rational tuning of enzyme properties—including stability, specificity, and kinetic parameters (K_m, k_cat). This is particularly relevant for developing specialized enzymes for diagnostic and therapeutic applications, a market driven by demand for precision medicine [25] [26].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Initial Velocity Conditions and Linear [E] Range [14]

- Prepare Reagents: In a suitable buffer, prepare a substrate concentration at a suspected K_m value. Prepare a stock enzyme solution and serial dilutions (e.g., 0.5x, 1x, 2x relative concentration).

- Run Progress Curves: In separate reactions, mix each enzyme dilution with the substrate. Use a continuous (e.g., spectrophotometric) or discontinuous method to measure product formation at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30 min).

- Analyze Data: Plot product concentration versus time for each [E]. Identify the enzyme dilution that yields a linear progress curve for the longest duration without substrate depletion (typically <10% conversion). This defines the maximum usable [E] and assay time.

- Verify Linearity: Confirm that the initial slope (velocity) of the linear portion is directly proportional to the enzyme dilution factor.

Protocol 2: Qualitative and Quantitative Activity Screening (Microslide & Dye-Release Assays) [27] This dual-protocol is used for screening hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., antimicrobial lysins).

- A. Qualitative Microslide Diffusion Assay:

- Embed heat-killed bacterial cells or purified peptidoglycan in a soft agarose matrix on a microscope slide.

- Punch wells and add serial dilutions of the test enzyme.

- Incubate in a humidity chamber. Enzymatic activity appears as a clear zone of lysis around the well. The diameter provides a qualitative estimate of activity and potency.

- B. Quantitative Dye-Release Assay:

- Covalently label the same substrate (cells or peptidoglycan) with Remazol Brilliant Blue R (RBB) dye.

- Incubate the labeled substrate with the enzyme.

- Stop the reaction, centrifuge, and measure the absorbance of the supernatant (containing released dye-labeled fragments). The signal is proportional to the degree of hydrolysis, allowing precise kinetic measurements and K_m determination.

Diagram 2: Enzyme-Substrate Kinetic Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance in Assay Design | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Source, purity, and specific activity are critical for reproducibility [14]. | Determine specific activity (U/mg); check for contaminating activities; ensure lot-to-lot consistency. |

| Native or Surrogate Substrate | The molecule transformed by the enzyme. Defines the reaction being measured [14]. | Chemical purity is essential. Surrogates (e.g., fluorogenic peptides) must mimic natural kinetics. Know its K_m. |

| Cofactors / Cations | Required for activity of many enzymes (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases, NADH for dehydrogenases) [22]. | Identity and optimal concentration must be established empirically; omission is a key negative control. |

| Buffer System | Maintains optimal pH and ionic strength for enzyme activity and stability [14]. | Avoid components that inhibit or chelate. Buffer capacity must be sufficient for reaction duration. |

| Positive Control Inhibitor | A known inhibitor of the enzyme (e.g., a reference compound) [14]. | Critical for assay validation; confirms the system responds correctly to inhibition. |

| Detection Reagents | Enable measurement of product formation/substrate depletion (e.g., chromogens, fluorophores, coupled enzymes) [24]. | Must be stable, non-inhibitory, and have a linear response range exceeding product generated. |

| Labeled Substrates (e.g., RBB-Dyed) | For specialized quantitative endpoint assays like the dye-release protocol [27]. | Labeling must be covalent and not block enzyme access to the cleavage site. |

Within the systematic framework of enzyme assay design research, the selection and optimization of core biochemical reagents are not mere procedural steps but fundamental determinants of experimental success and data reliability [22]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of two pivotal classes of reagents—buffer systems and enzyme cofactors—focusing on their roles, stability profiles, and integration into robust assay development. The stability of these components directly underpins the reproducibility and accuracy of kinetic measurements, binding studies, and high-throughput screening campaigns that drive drug discovery and fundamental enzymology [28] [29].

The Critical Role of Buffers in Enzyme Assay Design

Buffer solutions maintain a stable pH, creating a consistent chemical environment that preserves enzyme conformation, activity, and interaction with substrates [29]. An ideal buffer is chemically inert, has a pKa within 1 unit of the desired assay pH, demonstrates minimal temperature sensitivity, and does not absorb light at wavelengths used for detection [29].

Quantitative Stability Profiles of Common Buffer Systems

The long-term stability of assay components varies significantly with buffer choice. A 2024 study systematically quantified the degradation of nicotinamide cofactors in three common buffers at pH 8.5, revealing critical differences for assay planning [28].

Table 1: NADH Degradation Rates in Different Buffer Systems (Initial [NADH] = 2 mM) [28]

| Buffer (50 mM) | Degradation Rate at 19°C (µM/day) | Remaining after 43 days at 19°C | Degradation Rate at 25°C (µM/day) | Remaining after 43 days at 25°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tris | 4 | >90% | 11 | ~75% |

| HEPES | 18 | Not specified | 51 | Not specified |

| Sodium Phosphate | 23 | Not specified | 34 | Not specified |

Key Findings: Tris buffer demonstrated superior stability for NADH, with degradation rates 4.5 to 5.8 times slower than HEPES and phosphate buffers at 19°C [28]. A mild temperature increase from 19°C to 25°C accelerated degradation in all buffers, most markedly in HEPES, underscoring the need for strict temperature control in long-term or coupled assays [28].

Strategic Buffer Selection: A Systematic Workflow

Selecting a buffer requires balancing enzyme compatibility, cofactor stability, and detection methodology. The following workflow outlines a systematic decision process.

Cofactors: Essential Partners in Catalysis

Cofactors are non-protein molecules essential for the catalytic activity of many enzymes. They can be organic coenzymes (e.g., NADH, ATP) or inorganic metal ions (e.g., Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺). The inactive protein without its cofactor is the apoenzyme, and the active complex is the holoenzyme [22].

Stability Kinetics of Nicotinamide Cofactors

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD⁺/NADH) is a crucial redox cofactor. Its stability is pH-dependent and buffer-specific [28].

- NADH Degradation: Follows acid-catalyzed pathways. The observed rate constant (kobs) is: *k*obs = kw + *k*H+ + kHA, where *k*w is general degradation, kH+ is general acid catalysis, and *k*HA is specific acid catalysis by the buffer's conjugate acid [28]. Buffers with higher pKa yield a lower concentration of protonated acid (HA), reducing k_HA and enhancing NADH stability [28].

- NAD⁺ Degradation: Follows base-catalyzed pathways [28].

- Optimal pH: The stability of both NADH and NAD⁺ is maximized near pH 8.5, representing a compromise between the opposing acid- and base-catalyzed degradation mechanisms [28].

Table 2: Qualitative Stability of NAD⁺ in Different Buffers Over 43 Days [28]

| Buffer (50 mM, pH 8.5) | Observed NAD⁺ Stability | Key Spectral Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Phosphate | Degraded at a rate similar to NADH | Reduction in 260 nm peak absorbance |

| HEPES | Nearly complete degradation | Strong reduction in 260 nm peak; noticeable red shift |

| Tris | Most stable formulation | Minimal change in absorbance spectrum |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Cofactor Stability via UV-Vis Spectroscopy

This protocol is adapted from methods used to generate the data in Table 1 [28].

Objective: To quantify the degradation rate of reduced nicotinamide cofactors (NADH) in different buffer systems over time.

Materials:

- NADH stock solution (e.g., 100 mM in water, aliquoted and stored at -80°C)

- Buffer stocks (e.g., 1 M Tris, HEPES, Sodium Phosphate, pH-adjusted to 8.5 at assay temperature)

- Ultrapure water

- UV-transparent microplates or cuvettes

- Plate reader or spectrophotometer with temperature control

- Sealing film for plates or parafilm for cuvettes

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare 10 mL of 2 mM NADH in each 50 mM test buffer (Tris, HEPES, Sodium Phosphate, all at pH 8.5). Filter-sterilize (0.2 µm) if the assay will extend beyond 24 hours.

- Aliquoting: Dispense 200 µL of each NADH-buffer solution into multiple wells of a 96-well plate or into individual micro cuvettes. Prepare enough replicates for all time points in duplicate or triplicate.

- Incubation: Seal the plate or cover cuvettes to prevent evaporation. Place samples in controlled-temperature environments (e.g., 19°C and 25°C).

- Kinetic Measurement: At predetermined time points (e.g., daily for the first week, then weekly), measure the absorbance of each sample at 340 nm (A₃₄₀, λ_max for NADH) and 260 nm (A₂₆₀, for total nucleotides). Use a blank of the corresponding buffer without NADDH for background subtraction.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate NADH concentration at each time point using the extinction coefficient (ε₃₄₀ = 6220 M⁻¹cm⁻¹).

- Plot concentration versus time for each buffer and temperature condition.

- Fit the linear portion of the degradation curve to obtain the degradation rate (µM/day).

- The ratio A₃₄₀/A₂₆₀ can provide insight into the specificity of degradation; a decreasing ratio indicates selective loss of the dihydropyridine ring characteristic of NADH [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

This table catalogs key reagents, their functions, and stability considerations for robust enzyme assay design.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Assays

| Reagent Category & Example | Primary Function in Assay | Key Stability Considerations & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Buffers | ||

| Tris (pKa ~8.1) | Maintains pH in neutral to slightly alkaline range (7-9) [29]. | pH is temperature-sensitive (ΔpKa ≈ -0.031/°C). Pre-equilibrate to assay temperature before pH adjustment. Shows superior long-term stability for NADH [28]. |

| HEPES (pKa ~7.5) | "Good's Buffer" for physiological pH (6.8-8.2) [29]. | Low temperature sensitivity. Can form reactive radicals under photo-oxidation; protect from light [29]. |

| Phosphate (PBS) (pKa₂ ~7.2) | Maintains neutral pH and ionic strength [29]. | Can chelate essential metal ions (e.g., Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) and precipitate multivalent cations. Promotes rapid NADH degradation [28]. |

| Redox Cofactors | ||

| NADH / NADPH | Electron donor for oxidoreductases (dehydrogenases, reductases). | Highly susceptible to acid-catalyzed degradation [28]. Prepare fresh solutions daily in Tris buffer (pH ≥7.5) and keep on ice. Monitor purity via A₃₄₀/A₂₆₀ ratio (~0.45 for pure NAD(P)H). |

| NAD⁺ / NADP⁺ | Electron acceptor for oxidoreductases. | Susceptible to base-catalyzed degradation [28]. Stable in slightly acidic conditions but must be compatible with enzyme pH optimum. |

| Metal Cofactors | ||

| MgCl₂ / MgSO₄ | Common activator for kinases, polymerases, and ATP-dependent enzymes. | Prone to hydrolysis and precipitation at high pH/phosphate buffers. Add separately from phosphate stock to avoid precipitation. Use chloride salts for higher solubility. |

| ZnCl₂ / ZnSO₄ | Structural and catalytic component for metalloproteases, phosphatases. | Easily precipitates as hydroxide above pH 6.5. Often added at low micromolar concentrations from a concentrated, acidic stock solution. |

| Stability Additives | ||

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Stabilizes dilute enzyme solutions, reduces surface adsorption. | Use protease-free, low-fatty acid grade. Can bind small molecule substrates/cofactors; requires empirical testing. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reduces disulfide bonds, maintains cysteine residues in reduced state. | Unstable in aqueous solution (oxidized by air). Prepare fresh stock solutions daily. Use at 0.5-1 mM typically. |

| Glycerol / Sucrose | Protein stabilizers, reduce freezing damage, stabilize enzyme conformation. | High viscosity can slow reaction kinetics. Use at 5-20% (v/v) glycerol or 0.2-0.5 M sucrose. |

Selecting the Right Toolbox: Advanced Enzymatic Assay Methods and Their Applications in Drug Discovery

Fluorescence-based assays, with Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) as a premier example, constitute a transformative methodology in enzyme assay design. By enabling the direct, continuous, and label-free monitoring of biochemical reactions, these techniques provide unparalleled access to real-time kinetic parameters and exhibit exceptional sensitivity down to the single-molecule level [30] [31]. This whitepaper details the core principles of FRET, presents validated experimental protocols for kinetic characterization, and quantitatively demonstrates its advantages over traditional methods. Framed within the broader thesis of fundamentals of enzyme assay design, this guide underscores how fluorescence-based approaches address critical needs in modern research and drug discovery for high-throughput, quantitative, and physiologically relevant data [32] [33].

The design of robust, informative enzyme assays is a cornerstone of mechanistic biochemistry and drug discovery. The ideal assay provides a direct, quantitative, and continuous readout of activity with minimal perturbation to the native enzymatic process [32]. For decades, researchers were constrained by discontinuous, low-throughput, or hazardous methods like radiometric assays [30]. Fluorescence-based detection, particularly techniques harnessing FRET, has emerged as a dominant solution, offering a powerful combination of real-time kinetics, high sensitivity, and adaptability to high-throughput screening (HTS) formats [34] [33].

FRET operates as a "spectroscopic ruler," where energy is non-radiatively transferred from an excited donor fluorophore to a proximal acceptor molecule over distances typically between 2-10 nm [35] [31]. This transfer efficiency is exquisitely sensitive to the inverse sixth power of the distance separating the dyes, making FRET an ideal reporter for conformational changes, binding events, and catalytic cleavage [35] [36]. The integration of FRET and other fluorescence modalities into enzyme assay design represents a paradigm shift, allowing researchers to move from endpoint measurements to dynamic, time-resolved observations of biological function.

Core Principles: FRET Theory and Key Advantages

2.1 The FRET Mechanism and Quantitative Relationship FRET is a distance-dependent photophysical process mediated through dipole-dipole coupling. Its efficiency (E) is governed by the Förster equation:

E = 1 / [1 + (r/R₀)⁶]

where r is the donor-acceptor distance and R₀ is the Förster radius (the distance at which efficiency is 50%) [35]. The R₀ is determined by the spectral overlap of donor emission and acceptor absorption, the donor's quantum yield, and the relative orientation of the dipoles [37]. This fundamental relationship enables the translation of fluorescence signals into quantitative spatial information, forming the basis for kinetic measurements.

2.2 Advantages for Enzyme Kinetics and High-Throughput Screening The practical benefits of FRET and fluorescence-based assays for enzyme assay design are manifold:

- Real-Time, Continuous Monitoring: Reactions can be followed in real time without the need for quenching or separation, enabling the direct determination of pre-steady-state and steady-state kinetic parameters (e.g., kₚₒₗ, Kₐ, Kᵢ) from a single experiment [30].

- Exceptional Sensitivity and Single-Molecule Resolution: Fluorescence detection offers very low background and high signal-to-noise, facilitating studies at nanomolar enzyme concentrations [34]. Single-molecule FRET (smFRET) extends this to observing heterogeneous populations and rare enzymatic events in equilibrium without synchronization [31] [38].

- Homogeneous, "Mix-and-Read" Formats: FRET-based substrates, such as quenched fluorescent peptides, yield a fluorescent signal only upon enzymatic cleavage, eliminating wash steps and enabling true HTS in 384- or 1536-well plates [36] [33].

- Versatility and Universal Detection: Assays can be designed around specific fluorogenic substrates or universal detection of common products (e.g., ADP, AMP), making the platform applicable to diverse enzyme classes like kinases, proteases, and polymerases [30] [33].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Assay Formats [33]

| Assay Type | Primary Readout | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiometric | Radioisotope decay | Direct, quantitative measurement | Radioactive hazard; low throughput; waste disposal | Historical benchmark; specific binding studies |

| Fluorescence/FRET | Fluorescence intensity, polarization, or lifetime | High sensitivity; real-time kinetics; HTS compatible | Potential for compound interference (auto-quenching) | Primary HTS, mechanistic kinetic studies |

| Luminescence | Photon emission (e.g., luciferase) | Extremely high sensitivity; broad dynamic range | Susceptible to luciferase inhibitors; requires coupling enzymes | ATPase, kinase activity; reporter gene assays |

| Absorbance | Optical density (color change) | Simple, inexpensive, robust | Low sensitivity; not suitable for miniaturized HTS | Educational labs; initial validation |

| Label-Free (SPR, ITC) | Mass, refractive index, or heat change | No labeling required; provides thermodynamic data | Very low throughput; high cost; specialized equipment | Biophysical characterization; binding affinity |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Characterization

This section provides detailed methodologies for two foundational fluorescence-based assays: one using an environmentally sensitive fluorophore for polymerase kinetics, and another using a FRET-quenched peptide for protease activity.

3.1 Protocol A: Real-Time Single-Nucleotide Addition Kinetics Using 2-Aminopurine (2-AP) This stopped-flow fluorescence assay measures the microscopic rate constants of nucleotide incorporation by RNA/DNA polymerases [30].

1. Substrate Design and Preparation:

- Fluorescent Elongation Complex: Design a promoter-free nucleic acid scaffold containing a short RNA primer annealed to a DNA template. Incorporate the fluorescent adenine analog 2-aminopurine (2-AP) at a specific position in the template strand (e.g., at the n+1 site relative to the primer terminus). The 2-AP fluorescence is quenched by base stacking and increases upon local structural change during catalysis [30].

- Complex Formation: Pre-incubate the 2-AP-labeled nucleic acid scaffold with the polymerase (e.g., T7 RNA polymerase) to form a stable elongation complex.

2. Stopped-Flow Kinetic Experiment:

- Instrument Setup: Use a stopped-flow fluorimeter equipped with a thermostat (e.g., 25°C). Set the excitation wavelength to 310 nm (for 2-AP) and monitor emission through a 370 nm bandpass filter.

- Rapid Mixing: One syringe contains the pre-formed enzyme-substrate complex (e.g., 200 nM). The other syringe contains a range of concentrations of the correct incoming nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) (e.g., 1 – 400 µM).

- Data Acquisition: Upon rapid mixing, record the fluorescence increase over time (e.g., from 2 ms to 60 s) for each NTP concentration. Perform a minimum of 3-5 technical replicates per condition.

3. Data Analysis:

- Fit each fluorescence time trace to a single-exponential equation to obtain the observed rate constant (kₒbₛ) at each NTP concentration.

- Plot kₒbₛ vs. [NTP] and fit the hyperbolic dependence to the equation: kₒbₛ = (kₚₒₗ × [NTP]) / (Kₐ + [NTP]).

- The fit yields the maximum incorporation rate constant (kₚₒₗ) and the apparent ground-state NTP dissociation constant (Kₐ) [30].

Table 2: Example Kinetic Parameters for T7 RNA Polymerase Determined by 2-AP Stopped-Flow Assay [30]

| Template Base | Incoming NTP | kₚₒₗ (s⁻¹) | Kₐ (µM) | kₚₒₗ / Kₐ (µM⁻¹ s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dC | GTP | 190 ± 10 | 70 ± 10 | 2.7 |

| dT | ATP | 145 ± 5 | 71 ± 11 | 2.0 |

| dG | CTP | 209 ± 27 | 30 ± 13 | 7.5 |

3.2 Protocol B: Continuous Protease Activity Assay Using FRET-Quenched Peptides This homogeneous assay is ideal for high-throughput screening and kinetic characterization of proteolytic enzymes [34] [36].

1. FRET Substrate Design:

- Peptide Synthesis: Synthesize a peptide sequence containing the target enzyme's cleavage site. Conjugate a donor fluorophore (e.g., EDANS, Cy3, Alexa Fluor 488) to one side of the scissile bond and an acceptor quencher (e.g., Dabcyl, QSY-7, BHQ-1) to the other. In the intact substrate, FRET quenches the donor fluorescence.

- Substrate Selection: Validate substrate kinetics to ensure Km is suitable for the assay ([S] ≈ Km for competitive inhibition studies).

2. Microplate-Based Kinetic Assay:

- Reaction Setup: In a black 384-well plate, mix the assay buffer, enzyme (at a concentration where product formation is linear with time), and the test compound (inhibitor/activator). Initiate the reaction by adding the FRET peptide substrate.

- Real-Time Detection: Immediately place the plate in a pre-heated plate reader. Continuously monitor the increase in donor fluorescence (e.g., excitation/emission for EDANS: 340 nm/490 nm) every 10-30 seconds for 15-60 minutes.

- Controls: Include positive control wells (enzyme + substrate, no inhibitor), negative control wells (substrate only, no enzyme), and blank wells (buffer only).

3. Data Processing and Analysis:

- Subtract the average signal from the negative control wells from all other wells.

- For each well, plot fluorescence vs. time. The initial linear slope represents the initial velocity (v₀).

- For inhibitor characterization, plot v₀ vs. [inhibitor] to determine the IC₅₀. For mechanistic studies, measure v₀ at varying substrate and inhibitor concentrations and fit data to the appropriate Michaelis-Menten inhibition models (competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Instrumentation

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Fluorescence-Based Enzyme Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Considerations for Assay Design |

|---|---|---|

| Environment-Sensitive Fluorophores (e.g., 2-AP) | Incorporated into nucleic acids or proteins; fluorescence increases/decreases upon binding or catalysis [30]. | Minimal structural perturbation; large dynamic range in signal change. |

| FRET Donor-Acceptor Pairs (e.g., CFP/YFP, Alexa Fluor 488/555) | Genetically encoded or chemically conjugated pairs for distance sensing [35] [31]. | High spectral overlap (J); photostability; well-separated emission for crosstalk correction. |

| Quenched Fluorescent (FRET) Peptides | Custom peptides with flanking fluorophore/quencher; cleavage yields fluorescence [36]. | Specificity for target enzyme; optimal solubility; low background (high quenching efficiency). |

| Universal Detection Reagents (e.g., Transcreener) | Antibodies or binders specific to common products (ADP, AMP) coupled to FRET or polarization readouts [33]. | Versatile across enzyme families; reduces assay development time; avoids coupled enzymes. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrofluorimeter | Instrument for rapid mixing (ms) and recording of fast kinetic fluorescence traces [30]. | Dead time, temperature control, and detector sensitivity are critical for pre-steady-state kinetics. |

| Microplate Reader with Kinetic Capability | Instrument for continuous fluorescence monitoring in multi-well plates for HTS [33]. | Sensitivity, speed of reading, temperature control, and compatibility with automation. |

| Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET) Setup | Custom microscopes (confocal or TIRF) for observing individual biomolecules [31] [38]. | Requires advanced instrumentation and expertise for sample immobilization, data acquisition, and complex analysis. |

Data Analysis and Advanced Applications

5.1 Analyzing smFRET Data for Conformational Dynamics smFRET trajectories reveal state transitions and dynamics. A major challenge is inferring accurate kinetic rates from noisy data. A 2022 blind benchmark of analysis tools (e.g., hidden Markov modeling, Bayesian inference) provides critical guidance [38]. For a simple two-state system, most tools inferred rate constants within ~12% of ground truth, but reported uncertainties varied widely. The study recommends using multiple analysis tools and rigorous uncertainty estimation for robust conclusions [38].

5.2 FRET in Dynamic Structural Biology Beyond simple activity assays, FRET is pivotal in "dynamic structural biology" for mapping conformational landscapes of enzymes. smFRET can resolve heterogeneities, detect rare intermediates, and measure dynamics over microseconds to hours, integrating seamlessly with other structural techniques [31].

Diagram 1: FRET Mechanism as a Reporter for Enzymatic Events. The efficiency (E) of non-radiative energy transfer from a donor to an acceptor fluorophore is exquisitely sensitive to their nanoscale separation (r). An enzymatic process (e.g., substrate cleavage, protein hinge motion) alters this distance, resulting in a quantifiable change in fluorescence signal [35] [36].

Diagram 2: Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET) Workflow for Enzyme Dynamics. This pipeline transforms a biochemically labeled sample into quantitative kinetic parameters. A critical final step involves using specialized analysis tools to infer rate constants from noisy FRET trajectories, a process recently benchmarked to guide best practices [31] [38].

Fluorescence-based assays, particularly those utilizing FRET, are indispensable tools in the modern enzyme assay design portfolio. They successfully address the core demands of contemporary research: the need for real-time kinetic resolution, exceptional sensitivity, and robust compatibility with high-throughput workflows. From elucidating the fundamental catalytic steps of a polymerase using stopped-flow kinetics to screening thousands of compounds for protease inhibition in microplates, these methods provide a direct window into enzymatic function.

As the field progresses, the convergence of advanced fluorescence techniques like smFRET, standardized analysis frameworks [38], and open-science practices [31] promises to further solidify their role. For any thesis focused on the fundamentals of enzyme assay design, mastering fluorescence-based methodologies is not merely an option—it is essential for generating the high-quality, quantitative, and mechanistically insightful data that drives scientific discovery and therapeutic innovation forward.

Within the broader thesis on the fundamentals of enzyme assay design, the selection of an optimal detection technology is a cornerstone decision that dictates the sensitivity, robustness, and ultimate success of quantitative research. Luminescence assays, defined by the emission of light from a chemical or enzymatic reaction, have emerged as a preeminent technology for studying low-abundance biological targets, particularly in drug discovery and diagnostic development [39]. Their principal advantage lies in the intrinsic generation of signal without the requirement for an external excitation light source. This fundamental distinction from fluorescence and absorbance methods results in exceptionally low background interference, creating a high signal-to-noise ratio that is paramount for detecting targets at femtomolar concentrations [40] [41].

Maximizing the dynamic range—the span of concentrations over which an assay provides a linear and quantifiable signal—is critical for applications where analyte abundance can vary over several orders of magnitude, such as in biomarker detection, viral load quantification, or gene expression analysis. Luminescence assays inherently offer a wide dynamic range, often cited as 6-7 orders of magnitude, which is substantially broader than the 2-3 orders typical for absorbance assays [40]. This expansive range allows researchers to accurately quantify both trace-level and abundant targets within a single assay format, reducing the need for sample dilution and re-analysis.

This technical guide details the principles, optimization strategies, and advanced methodologies for leveraging luminescence assays to achieve maximal dynamic range and sensitivity for low-abundance targets, framed within the rigorous context of enzymatic assay design.

Core Principles: Luminescence vs. Alternative Modalities

The performance characteristics of any detection modality are rooted in its underlying physical principle. A comparative understanding is essential for informed assay design.

Luminescence relies on the direct production of photons via an exergonic chemical reaction. In biological contexts, this is typically catalyzed by an enzyme such as luciferase oxidizing its substrate (luciferin or derivatives). Since no external light is needed for excitation, issues of sample autofluorescence, light scatter, and photobleaching are minimized, leading to a superior signal-to-background ratio [41] [39].

In contrast, absorbance (or colorimetric) assays measure the attenuation of light passing through a sample. According to the Beer-Lambert law, absorbance is proportional to analyte concentration. However, this method is susceptible to interference from colored compounds, turbidity, and bubbles, which limit its sensitivity and dynamic range [40]. Fluorescence assays involve the excitation of a fluorophore with specific-wavelength light and the detection of emitted light at a longer wavelength. While sensitive and excellent for multiplexing, fluorescence assays can suffer from background autofluorescence, photobleaching, and inner-filter effects [39].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Detection Modalities for Enzyme Assays [40] [39] [42]

| Parameter | Luminescence | Fluorescence | Absorbance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Generation | Chemical/Enzymatic reaction emits light. | External light excites fluorophore, which emits light. | Measurement of light absorbed by chromophore. |

| Excitation Source | None (intrinsic). | Required (lamp, laser). | Required (broad spectrum). |

| Typical Sensitivity | Very High (femtomole to attomole). | High (picomole to femtomole). | Moderate (nanomole to picomole). |

| Typical Dynamic Range | 6 – 8 orders of magnitude [40]. | 3 – 5 orders of magnitude. | 2 – 3 orders of magnitude. |

| Background Signal | Very low (no excitation light). | Moderate (from autofluorescence, scatter). | Can be high (from turbidity, impurities). |

| Susceptibility to Interference | Low. | Moderate (inner-filter effect, quenching). | High (any light-absorbing material). |

| Key Advantage for Low-Abundance Targets | Ultimate sensitivity and wide linear range. | Spatial resolution & multiplexing. | Simplicity and low cost. |

For enzyme assays, operating within the initial velocity phase—where less than 10% of substrate is converted—is a fundamental tenet to ensure reaction rate is linear with time and enzyme concentration [20] [14]. Luminescence excels in this context by providing a stable, quantifiable signal directly proportional to product formation (e.g., ATP, NADH) or reporter enzyme activity over this critical period, even at minute levels of conversion.

Quantitative Performance and Key Optimization Parameters

The exceptional dynamic range of luminescence is not merely theoretical but is demonstrable and can be systematically optimized. Key assay parameters must be tuned to push the limits of detection (LOD) while maintaining linearity.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Common Luminescence Reporter Systems [41] [39]

| Luciferase Reporter | Source Organism | Primary Substrate | Peak Emission (nm) | ATP-Dependent? | Key Feature for Dynamic Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firefly Luciferase (FLuc) | Photinus pyralis | D-luciferin | 550-570 | Yes | Classic, high-activity system; wide linear range (~7 logs). |

| NanoLuc (NLuc) | Engineered from Oplophorus gracilirostris | Furimazine | ~460 | No | Very high specific activity & stability; excellent for demanding HTS. |

| Renilla Luciferase (RLuc) | Renilla reniformis | Coelenterazine | ~480 | No | Co-factor independent; often used in dual-reporter systems. |

| Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) | Gaussia princeps | Coelenterazine | ~460 | No | Secreted, small (20 kDa), very bright signal. |

Optimization Strategies to Maximize Dynamic Range:

- Substrate Kinetics and Concentration: Use substrate concentrations at or above the Km value to ensure zero-order kinetics with respect to substrate, making the signal depend solely on enzyme activity [14]. For glow-type assays, use saturating substrate concentrations to produce a stable, prolonged signal.

- Enzyme/Reporter Concentration: Titrate the amount of reporter enzyme (in a coupled assay) or the expression level (in cell-based assays) to ensure the signal remains in the linear response zone of the detector, avoiding saturation at high target levels [20].

- Instrument Calibration and Acquisition: Adjust the detector's integration time and gain to span a wide irradiance range. Shorter times/high gain capture bright signals without saturation, while longer times can pull weak signals above noise [43].

- Reaction Environment: Optimize buffer composition, pH, and co-factors (e.g., Mg2+ for FLuc) to maximize enzyme stability and catalytic efficiency, ensuring consistent signal across the entire plate and assay duration [39].

- Assay Format and Plate Selection: Use homogeneous, "add-and-read" formats to simplify workflows and reduce variability. White or opaque microplates are critical as they reflect emitted light to the detector, enhancing signal capture and reducing well-to-well crosstalk [40] [39].

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Pushing dynamic range to its theoretical limits for ultra-low abundance targets often requires moving beyond standard glow or flash assays to advanced signal amplification and digital detection strategies.

Protocol: Coupled Enzymatic Assay for Ultra-Sensitive ATP Detection (Cell Viability)

This protocol leverages the wide dynamic range of firefly luciferase to quantify ATP, a direct correlate of metabolically active cells, down to single-cell sensitivity.

Principle: ATP + D-luciferin + O₂ → (FLuc, Mg²⁺) → Oxyluciferin + AMP + PPi + CO₂ + Light [41] [39].