Mastering Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation: From Classic Methods to Modern Computational Tools

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the fundamental principles and advanced practices of enzyme kinetic parameter estimation.

Mastering Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation: From Classic Methods to Modern Computational Tools

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the fundamental principles and advanced practices of enzyme kinetic parameter estimation. It begins by establishing the core concepts of k_cat and K_M within the Michaelis-Menten framework and its essential assumptions. The guide then details practical methodological approaches, including initial rate and progress curve assays, and introduces modern software and computational tools for data fitting. A dedicated section addresses common experimental and analytical challenges, such as parameter identifiability and substrate competition, offering optimization strategies and troubleshooting advice. Finally, the article covers critical validation techniques and provides a comparative analysis of classical versus modern estimation methods. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with current best practices—highlighting innovations like the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) model, Bayesian inference, and machine learning frameworks like UniKP—this resource aims to empower professionals to obtain accurate, reliable kinetic parameters essential for drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and biomedical research.

The Cornerstones of Catalysis: Understanding k_cat, K_M, and the Michaelis-Menten Framework

Within the broader thesis on enzyme kinetic parameter estimation, the Michaelis-Menten parameters kcat (the catalytic constant), KM (the Michaelis constant), and their derived ratio kcat/KM (catalytic efficiency) form the indispensable quantitative foundation for understanding enzyme function [1]. These are not universal constants but condition-dependent parameters that provide deep insight into catalytic power, substrate affinity, and evolutionary optimization [1]. Their accurate determination is critical for applications ranging from metabolic modeling and systems biology to rational drug design and industrial biocatalyst engineering [1] [2]. This guide details their biological significance, methodologies for reliable estimation, and their practical application in research and development.

Defining the Core Parameters: Biological and Mathematical Foundations

The three core parameters describe different facets of an enzyme's interaction with its substrate.

kcat (Turnover Number): This parameter, defined as Vmax/[E]total, represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time. It is a direct measure of the intrinsic catalytic power of the enzyme-substrate complex once formed. A high kcat indicates a fast catalytic cycle, often reflecting efficient chemical steps (e.g., proton transfer, bond breaking/forming) within the active site.

KM (Michaelis Constant): Operationally defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax, KM is an approximate inverse measure of the enzyme's apparent affinity for its substrate. Mathematically, for the simplest reaction scheme (E + S ⇌ ES → E + P), KM = (k(-1) + kcat)/k1 [3]. A low KM typically indicates that the enzyme requires a low substrate concentration to become saturated, suggesting tight binding. However, it is crucial to remember that K_M is a kinetic parameter influenced by both binding (dissociation) and catalytic events, not a pure equilibrium dissociation constant.

Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM): This ratio is the second-order rate constant for the reaction of free enzyme with free substrate to yield product. It describes the enzyme's overall effectiveness at low substrate concentrations ([S] << KM), where the reaction rate is proportional to kcat/KM * [E][S]. It represents the ultimate measure of an enzyme's proficiency, as it incorporates both substrate recognition/binding (reflected in KM) and catalytic power (k_cat) [3] [2]. Evolution often acts to maximize this parameter for an enzyme's primary physiological substrate.

Table 1: Summary of Core Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Biological Significance | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Constant | k_cat | V_max / [Total Active Enzyme] | Intrinsic catalytic speed; turnover number. | s⁻¹ |

| Michaelis Constant | K_M | [S] at which v = V_max/2 | Apparent affinity for substrate; [S] for half-saturation. | M (mol/L) |

| Catalytic Efficiency | kcat / KM | Second-order rate constant for productive encounter. | Overall enzyme effectiveness at low [S]. | M⁻¹s⁻¹ |

Experimental Methodologies for Parameter Estimation

Reliable parameter estimation hinges on robust experimental design and appropriate data analysis.

Foundational Principles and Assay Conditions

The validity of the Michaelis-Menten equation rests on several assumptions: the concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex is steady, the reaction is irreversible or initial rates are measured, and only a small fraction of substrate is consumed. Therefore, initial rate (v_0) measurements are standard, where product formation is linear with time [4]. Key considerations for assay design include:

- Enzyme Concentration: Must be significantly lower than substrate ([E] << [S]) to maintain the steady-state assumption.

- Substrate Range: Should bracket the KM value, typically from ~0.2 to 5 KM, to define the hyperbolic curve accurately.

- Buffer and Conditions: pH, temperature, and ionic strength must be carefully controlled and physiologically relevant, as they profoundly affect kinetic parameters [1]. For example, non-physiological pH can misrepresent an enzyme's natural function [1].

- Continuous vs. Discontinuous Assays: Continuous spectrophotometric or fluorometric assays are preferred for ease of initial rate measurement. Discontinuous assays (e.g., HPLC) require careful sampling during the linear phase.

The Classical Initial Rate Method

The standard protocol involves measuring initial velocities (v0) across a range of substrate concentrations ([S]) and fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation: v0 = (Vmax [S]) / (KM + [S]).

- Protocol:

- Prepare a master solution of purified enzyme in appropriate assay buffer.

- Prepare a serial dilution of substrate in buffer to generate 8-10 concentrations spanning the expected KM.

- In a cuvette or microplate well, mix substrate and buffer to the final desired volume.

- Initiate the reaction by adding enzyme, mixing rapidly.

- Immediately record the change in signal (e.g., absorbance) over time, ensuring the recording captures only the linear phase (typically <10% substrate conversion).

- Calculate v0 for each [S] as the slope of the linear product-versus-time plot.

- Fit the ([S], v0) data pairs to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression to obtain best-fit estimates for KM and Vmax (and thus kcat).

- Advantages: Direct, theoretically sound, and the most common method.

- Challenges: Requires rapid, precise measurement of initial linear phases; can be difficult with slow reactions or inconvenient detection methods.

The Integrated Rate Equation Method

An alternative approach uses the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation, which describes the time course of product formation: [P] = Vmax * t - KM * ln(1 - [P]/[S]_0). This method is advantageous when continuous monitoring is difficult [4].

- Protocol:

- Set up a single reaction mixture with known [E] and [S]_0.

- At multiple time points (or even a single well-chosen time point), stop the reaction and quantify the amount of product [P] formed.

- Fit the ([P], t) data directly to the integrated equation using non-linear regression to solve for Vmax and KM.

- Advantages: Does not require measurement of initial slopes; can yield reliable parameters from a single reaction progress curve, even with significant substrate depletion (up to ~70% conversion) [4]. Particularly useful for discontinuous assays.

- Challenges: Assumes enzyme stability and absence of product inhibition over the longer time course. More sensitive to deviations from ideal kinetic behavior.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Experimental Methods for k_cat and K_M Estimation

| Method | Key Principle | Data Required | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Initial Rate | Direct fit of v_0 vs. [S] to Michaelis-Menten equation. | Initial velocity (v_0) at multiple [S]. | Standard, well-characterized enzymes; continuous assays. | Requires accurate linear rate measurement; sensitive to substrate depletion. |

| Integrated Rate Equation | Fit of reaction progress curve to integrated rate law. | [Product] at multiple time points (t) for a given [S]_0. | Discontinuous assays; slow reactions; scarce substrates [4]. | Assumes enzyme stability; product inhibition can complicate analysis. |

| Fed-Batch Experimental Design | Optimal substrate feeding to maximize information content for parameter estimation. | Time-course data from a dynamically controlled reaction. | High-precision estimation for systems modeling; valuable enzymes/substrates [5]. | Requires sophisticated control and prior parameter estimates. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Item | Function & Importance | Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biocatalyst of interest. Source (species, tissue), purity, and specific activity must be known and consistent. | High purity (>95%); well-defined storage conditions; verified absence of interfering activities. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. Chemical purity and stability are critical. | Highest available purity; prepare fresh solutions or verify stability; use physiologically relevant substrates where possible [1]. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength. Can influence enzyme conformation and kinetics [1]. | Choose a buffer with appropriate pKa for target pH; ensure no chelating or inhibitory effects (e.g., Tris inhibits some enzymes) [1]. |

| Cofactors / Cations | Essential for activity of many enzymes (e.g., NAD(P)H, Mg²⁺, ATP). | Required concentration must be saturating and non-inhibitory. |

| Detection Reagents | Enable quantification of product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., chromogenic/fluorogenic couples, coupled enzymes). | Must be efficient, specific, and not rate-limiting; generate a strong, stable signal. |

| Microplates / Cuvettes | Reaction vessels. Material must not adsorb enzyme or substrate. | Clear for absorbance; low-binding for precious enzymes; compatible with detector. |

| Plate Reader / Spectrophotometer | Instrument for detecting signal change over time. Precision and temperature control are vital. | High sensitivity; fast kinetic reading capability; accurate temperature control (e.g., 30°C or 37°C) [1]. |

Data Analysis, Reliability, and Advanced Considerations

Non-linear least squares regression (e.g., in GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot) is the preferred method for fitting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation or its integrated form. It provides best-fit estimates and standard errors for parameters. Key sources of error include:

- Poor Experimental Design: Substrate concentrations that do not adequately bracket K_M.

- Non-Initial Rates: Using data where substrate depletion is significant, violating the model's assumption. This can be checked with Selwyn's test for enzyme stability [4].

- Ignoring Inhibitors: Unrecognized product inhibition or contamination.

- Incorrect Enzyme Concentration: Leads to systematic errors in calculating k_cat.

Parameter Reliability and Reproducibility

Reported kinetic parameters can vary widely due to differences in assay conditions (pH, temperature, buffer), enzyme source, and purity [1]. Researchers must critically evaluate literature values. Databases like BRENDA and SABIO-RK are valuable resources but require scrutiny of original experimental conditions [1]. The STRENDA (STandards for Reporting ENzymology DAta) guidelines promote reproducibility by mandating complete reporting of experimental details [1].

Beyond the Basics: Catalytic Efficiency in Context

While kcat/KM is a vital benchmark, it has limitations for selecting industrial biocatalysts, as it neglects factors like substrate concentration, product inhibition, and reaction reversibility in actual process conditions [2]. More sophisticated metrics like the efficiency function or catalytic effectiveness have been developed to incorporate these real-world factors [2]. For multi-enzyme systems and metabolic modeling, accurate parameters for each step are essential to avoid "garbage-in, garbage-out" simulations [1].

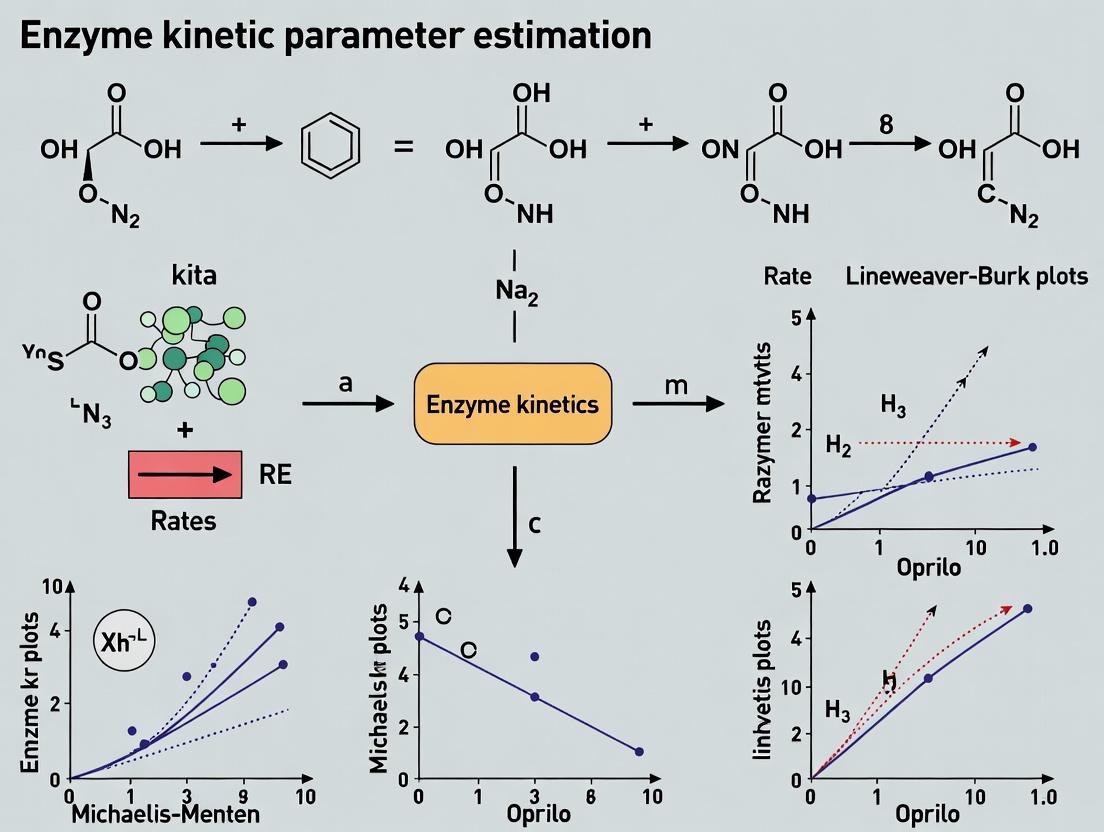

Diagram 1: Workflow for Determining Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

Computational Prediction and Emerging Frontiers

Experimental determination of kinetic parameters remains the gold standard but is resource-intensive. Computational prediction is an emerging frontier to address this bottleneck.

- The UniKP Framework: A unified machine learning framework predicts kcat, KM, and kcat/KM directly from enzyme protein sequences and substrate molecular structures (in SMILES format) [6]. It uses pre-trained language models (ProtT5 for proteins, a SMILES transformer) to generate feature vectors, which are then processed by an ensemble model (Extra Trees) for prediction [6].

- Performance and Utility: UniKP demonstrates high accuracy (R² ~0.68 for k_cat prediction) and can be fine-tuned to consider environmental factors like pH and temperature (EF-UniKP) [6]. It has been applied successfully to guide enzyme discovery and directed evolution, identifying mutants with improved catalytic efficiency [6].

- Limitations: Predictions are based on patterns in existing datasets (e.g., BRENDA) and may be less reliable for novel enzyme folds or substrates far from the training data distribution.

Diagram 2: Computational Prediction of Parameters via the UniKP Framework [6]

Application in Drug Development and Biotechnology

These core parameters are directly applied in industrial and pharmaceutical contexts.

- Drug Discovery (Enzyme Inhibitors): KM is crucial for characterizing target enzymes and designing substrate-competitive inhibitors. The kcat/K_M value helps assess the physiological relevance of a target under cellular substrate concentrations. Inhibitor potency is quantified by IC₅₀ or Kᵢ values, which are interpreted in the context of the enzyme's natural kinetics.

- Biocatalyst Engineering: In industrial enzymology, the goal is often to engineer enzymes for a higher kcat (productivity), a lower KM (efficient at low substrate cost), or, most importantly, an improved kcat/KM for the desired substrate. Parameters are used to screen mutant libraries and compare enzyme variants [2] [6].

- Systems & Synthetic Biology: Kinetic parameters are essential inputs for constructing predictive computational models of metabolism. Accurate KM and Vmax values for each enzyme in a pathway allow modeling of flux control, predicting the outcome of metabolic engineering, and identifying rate-limiting steps [1].

Diagram 3: Key Applications of Kinetic Parameters in R&D

The parameters kcat, KM, and kcat/KM are fundamental descriptors of enzyme function, providing a quantitative link between molecular structure and biological activity. Their careful experimental determination, guided by robust methodological principles and critical evaluation of conditions, is a cornerstone of rigorous enzymology. While challenges in reproducibility and condition-dependence persist, adherence to reporting standards and the innovative use of computational prediction tools like UniKP are enhancing the field. A deep understanding of these core parameters and their biological significance remains essential for advancing research across biochemistry, drug development, and biotechnology, enabling the rational design of experiments, inhibitors, and novel biocatalysts.

Abstract The Michaelis-Menten equation is the foundational mathematical model for characterizing enzyme kinetics, relating reaction velocity to substrate concentration through the parameters Vmax and Km. This technical guide details its derivation from the steady-state assumption, enumerates its critical assumptions, and evaluates classic linear transforms like the Lineweaver-Burk plot. Framed within a thesis on enzyme kinetic parameter estimation, the article integrates contemporary advances—including single-molecule kinetics and machine learning prediction frameworks—with established experimental protocols. It provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to accurately determine and interpret kinetic parameters, which are essential for elucidating catalytic mechanisms, designing inhibitors, and engineering enzymes.

Foundational Concepts and Historical Context

The quantitative study of enzyme catalysis was revolutionized in 1913 by Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten, who proposed a kinetic model to explain the hyperbolic relationship observed between substrate concentration and reaction velocity [7] [8]. Their work built upon Victor Henri's earlier suggestion of an enzyme-substrate complex, moving enzymology from qualitative observation to a rigorous mathematical framework [7]. The resulting Michaelis-Menten equation remains the cornerstone for analyzing enzyme activity, inhibitor design, and metabolic flux.

The classical model describes a single-substrate, irreversible reaction through a two-step mechanism. First, the enzyme (E) reversibly binds the substrate (S) to form an enzyme-substrate complex (ES). Second, this complex undergoes an irreversible catalytic conversion to release the product (P) and regenerate the free enzyme [9] [7]. This sequence is represented as: ( E + S \xrightleftharpoons[k{-1}]{k1} ES \xrightarrow{k2} E + P ) where (k1) and (k{-1}) are the rate constants for the formation and dissociation of the ES complex, and (k2) (often denoted (k_{cat})) is the catalytic rate constant for product formation [10] [7]. The central goal of Michaelis-Menten kinetics is to derive a rate law for this mechanism that yields the characteristic hyperbolic saturation curve.

Derivation and Core Mathematical Assumptions

The derivation of the Michaelis-Menten equation relies on several simplifying assumptions that make the system tractable for analysis. Violations of these assumptions can lead to significant errors in parameter estimation, making their understanding critical.

Explicit Statement of Assumptions

Five key assumptions underpin the standard derivation [9] [10] [8]:

- Steady-State Assumption: The concentration of the ES complex remains constant over the measured period of the reaction. The rate of its formation equals the rate of its breakdown ((d[ES]/dt = 0)) [10] [8].

- Initial Velocity Assumption: Measurements are made at the start of the reaction when the product concentration is negligible. This allows the reverse reaction of product rebinding ((E + P \rightarrow ES)) to be ignored [9] [10].

- Substrate Concentration Assumption: The total substrate concentration ([S]T) is in vast excess over the total enzyme concentration ([E]T). Thus, the amount of substrate bound in the ES complex is insignificant, and ([S]{free} \approx [S]T) [10] [8].

- Single Reaction Pathway: The model assumes a single, defined ES complex leading to product.

- Free and Complexed Enzyme States: The enzyme exists either as free enzyme (E) or as the enzyme-substrate complex (ES); therefore, ([E]_T = [E] + [ES]) [10].

Mathematical Derivation from the Steady-State

The derivation begins by applying the steady-state condition to the ES complex. The rate of ES formation is given by (k1[E][S]). The rate of ES breakdown is the sum of dissociation and product formation: (k{-1}[ES] + k2[ES]). At steady state: (k1[E][S] = (k{-1} + k2)[ES]) (Equation 1)

Using the enzyme conservation equation (([E] = [E]T - [ES])) and substituting into Equation 1: (k1([E]T - [ES])[S] = (k{-1} + k_2)[ES])

Rearranging to solve for ([ES]): ([ES] = \frac{[E]T [S]}{(k{-1} + k2)/k1 + [S]})

The Michaelis constant (Km) is defined as ((k{-1} + k2)/k1). Substituting gives: ([ES] = \frac{[E]T [S]}{Km + [S]}) (Equation 2)

The observed reaction velocity (v) is the rate of product formation: (v = k_2[ES]) (Equation 3)

Substituting Equation 2 into Equation 3 yields: (v = \frac{k2 [E]T [S]}{K_m + [S]})

The maximum velocity (V{max}) is achieved when all enzyme is saturated as ES complex (([ES] = [E]T)), making (V{max} = k2[E]T). The final Michaelis-Menten equation is: (v = \frac{V{max} [S]}{K_m + [S]}) (Equation 4)

This equation describes a rectangular hyperbola where (v) approaches (V{max}) asymptotically as ([S]) increases. The constant (Km) has units of concentration and equals the substrate concentration at which (v = V{max}/2) [11] [7]. It is crucial to note that (Km) is not a simple dissociation constant for the ES complex (which would be (k{-1}/k1)), except in the specific case where (k2 \ll k{-1}) [11] [7].

Experimental Methodology for Parameter Estimation

Accurate determination of (V{max}) and (Km) requires careful experimental design and data analysis, adhering to the model's assumptions.

Standard Experimental Protocol

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a fixed, low concentration of purified enzyme (typically nM to µM range) in an appropriate buffer (controlling pH, temperature, ionic strength). A series of reaction mixtures is created with substrate concentrations spanning values both below and above the anticipated (Km) (e.g., from (0.2 \times Km) to (5 \times K_m)) [11].

- Initial Rate Measurement: Initiate the reaction, commonly by adding enzyme or substrate. The product formation or substrate depletion is monitored continuously (e.g., via spectrophotometry) for a short initial period (usually <5% of substrate conversion). The slope of this linear phase is the initial velocity (v) [9] [10].

- Data Collection: Record the initial velocity (v) at each substrate concentration ([S]).

Data Analysis: From Linear Transforms to Nonlinear Regression

Classic Linear Transforms: Before ubiquitous computing, linear transformations of Equation 4 were used to extract parameters.

- Lineweaver-Burk (Double-Reciprocal) Plot: The most common transform. Taking the reciprocal of both sides of Equation 4 gives: (\frac{1}{v} = \frac{Km}{V{max}} \cdot \frac{1}{[S]} + \frac{1}{V{max}}) A plot of (1/v) vs. (1/[S]) yields a straight line with a slope of (Km/V{max}) and a y-intercept of (1/V{max}) [11] [12]. While instructive, this plot heavily weights data points at low ([S]) (high (1/[S])), potentially distorting error analysis and leading to biased parameter estimates [11].

- Other Historical Transforms: The Eadie-Hofstee ((v) vs. (v/[S])) and Hanes-Woolf (([S]/v) vs. ([S])) plots offer alternative linearizations with different error-weighting properties.

Modern Best Practice: Nonlinear Regression Direct nonlinear fitting of the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation (Equation 4) to the untransformed ([S]) and (v) data is now the standard and most accurate method. Software like GraphPad Prism, Origin, or even Excel (with the Solver add-in) can perform this regression, providing statistically robust estimates of (V{max}) and (Km) along with their confidence intervals [11]. The workflow is: plot (v) vs. ([S]), then fit the data using Equation 4 as the model. The Lineweaver-Burk plot retains utility for visualizing data and diagnosing inhibitor modes but should not be used for primary parameter estimation [11] [12].

The following diagram illustrates the core chemical mechanism of enzyme catalysis that forms the basis of the Michaelis-Menten model.

Contemporary Advances in Kinetic Analysis

Recent technological and computational innovations are expanding the scope and precision of enzyme kinetic parameter estimation beyond the classical ensemble approach.

Single-Molecule Kinetics and High-Order Analysis

Single-molecule techniques allow observation of individual enzyme turnovers, revealing kinetic heterogeneity and dynamics masked in ensemble averages. A 2025 study derived a set of high-order Michaelis-Menten equations that relate higher statistical moments of the turnover time distribution (e.g., variance, skewness) to the reciprocal of substrate concentration [13]. This generalization enables the extraction of previously inaccessible "hidden" kinetic parameters from single-molecule data, such as:

- The mean lifetime of the enzyme-substrate complex.

- The probability that a binding event leads to catalysis (rather than dissociation).

- The binding rate constant. These parameters provide a more complete mechanistic picture of the catalytic cycle [13].

Computational Prediction and Data Extraction

The experimental measurement of (k{cat}) and (Km) remains resource-intensive. Machine learning models are now being developed to predict these parameters from protein sequence and substrate structure.

- UniKP Framework: A unified deep learning framework uses pretrained language models to convert enzyme sequences and substrate structures (as SMILES strings) into feature vectors. An ensemble model (e.g., Extra Trees) then predicts (k{cat}), (Km), and catalytic efficiency ((k{cat}/Km)) with significant accuracy (R² ~ 0.65-0.68 for (k_{cat})), aiding in enzyme discovery and engineering [6].

- Automated Data Mining: Tools like EnzyExtract (2025) use large language models (LLMs) to automatically extract kinetic parameters and experimental conditions from hundreds of thousands of published PDFs, moving data from the "dark matter" of literature into structured, usable databases. This dramatically expands the training data available for predictive models [14].

Successful execution and analysis of Michaelis-Menten kinetics requires both wet-lab reagents and computational tools.

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Michaelis-Menten Experiments

| Item | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. | Purity is essential to avoid confounding activities. Concentration must be known accurately and kept low relative to substrate [10]. |

| Substrate | The molecule transformed in the reaction. | Must be available in high purity. A stock solution is used to create a dilution series spanning a range around the expected Km [11]. |

| Assay Buffer | Provides stable pH and ionic environment. | Buffer composition (pH, salts, cofactors) must maintain enzyme activity and not interfere with detection. |

| Detection System | Quantifies reaction progress. | Common methods: spectrophotometry (measures chromogenic change), fluorometry, or coupled assays. Must have sufficient temporal resolution for initial rates [12]. |

| Data Analysis Software | Fits model to data, estimates parameters. | GraphPad Prism, OriginLab, R, or Python/SciPy. Non-linear regression of the hyperbolic equation is preferred [11]. |

Table 2: Parameters for Representative Enzymes and Prediction Performance

| Enzyme | Km (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Source/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 | Example of moderate affinity, slow turnover [7]. |

| Carbonic Anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ | Example of extremely high catalytic efficiency (diffusion-limited) [7]. |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ | Example of very high substrate affinity (low Km) [7]. |

| UniKP Model Prediction | N/A | N/A | N/A | Prediction R² for kcat: 0.68; for Km/kcat/Km: ~0.65 [6]. |

| EnzyExtractDB Scope | N/A | N/A | N/A >218,000 kcat/Km entries extracted from literature (2025) [14]. |

The following diagram outlines the integrated workflow for enzyme kinetic parameter estimation, from traditional methods to modern computational approaches.

Critical Evaluation and Limitations

The Michaelis-Menten model is a powerful but simplified representation. Key limitations include:

- Multi-Substrate Reactions: The classic equation applies only to single-substrate reactions. Bisubstrate reactions require more complex models (e.g., Ping-Pong, Sequential).

- Violation of Assumptions: Significant product inhibition, substrate depletion, or enzyme instability during the assay invalidate the initial-rate and steady-state assumptions.

- Allostery and Cooperativity: Enzymes with multiple interacting subunits exhibit sigmoidal kinetics, described by the Hill equation rather than the Michaelis-Menten model.

- Time-Dependent Processes: The model assumes time-invariant rate constants. Processes like slow conformational changes or irreversible enzyme inactivation necessitate more complex kinetic schemes.

Progress curve analysis, which models the entire time course of product formation, is an advanced alternative that can extract kinetic parameters from a single reaction trace, improving efficiency [15]. Furthermore, tools like EnzyExtract highlight a paradigm shift toward AI-driven integration of legacy data, creating larger, more diverse datasets to fuel the next generation of predictive models in enzymology and drug discovery [14].

The Michaelis-Menten equation provides an indispensable framework for quantifying enzyme activity. Mastery of its derivation, underlying assumptions, and the practicalities of parameter estimation—via both traditional hyperbolic fitting and modern computational tools—is fundamental for research in biochemistry, drug discovery, and enzyme engineering. As this guide outlines, the field is evolving from purely empirical determination towards an integrated approach combining high-precision single-molecule experiments, automated data extraction from literature, and machine learning prediction. Within the broader thesis of kinetic parameter estimation, understanding this core model is the first critical step toward analyzing more complex enzymatic behaviors, designing effective inhibitors, and rationally engineering biocatalysts with desired properties.

The Michaelis-Menten framework serves as the foundational standard model for enzyme kinetics, enabling the estimation of critical parameters such as K_m and V_max. However, its simplifying assumptions—including low enzyme concentration, irreversibility, and the quasi-steady-state—often break down under physiologically relevant or complex experimental conditions, leading to significant inaccuracies in parameter estimation [16]. This whitepaper details the intrinsic limitations of the standard model, explores advanced kinetic frameworks like the total and differential Quasi-Steady-State Assumptions (tQSSA, dQSSA), and presents rigorous experimental and computational protocols designed to generate reliable, fit-for-purpose kinetic parameters essential for drug development and systems biology [1] [5] [16]. The integration of systematic experimental design and modern predictive computational tools is emphasized as a pathway to transcend these classical limitations.

In enzyme kinetics research, the parameters K_m (Michaelis constant) and V_max (maximum velocity) are not merely descriptive numbers; they are fundamental determinants of enzyme function. They are crucial for designing assays, modeling metabolic pathways, understanding inhibition mechanisms, and calculating in vivo flux rates [1]. The standard Michaelis-Menten model provides an elegant method for estimating these parameters but rests on a set of simplifying assumptions that are frequently violated in practice.

The reliability of any downstream application—from deterministic systems modeling of metabolic networks to the design of enzyme-targeting drugs—is entirely contingent on the accuracy of these foundational parameters [1]. This creates a "garbage-in, garbage-out" paradigm, where errors in initial parameter estimation propagate and compromise the predictive power of complex biological models [1]. Therefore, recognizing the limits of the standard model is not an academic exercise but a practical necessity for researchers and drug development professionals who depend on these values to make consequential decisions.

Core Limitations of the Standard Michaelis-Menten Model

The classic model, while powerful, is an approximation. Its systematic failures in specific contexts highlight the need for more robust frameworks.

Table 1: Key Simplifying Assumptions of the Michaelis-Menten Model and Their Practical Limitations

| Assumption | Theoretical Basis | Common Violations & Practical Consequences | Supporting References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Enzyme Concentration | [E] << [S], ensuring minimal substrate depletion by complex formation. | In vivo conditions or high-activity assays where [E] is significant relative to [S]. Leads to underestimation of K_m and inaccurate velocity predictions. | [16] |

| Irreversible Reaction | Product concentration [P] ≈ 0, preventing the reverse reaction. | Most enzymatic reactions are reversible. Product accumulation leads to product inhibition and false saturation kinetics, skewing both K_m and V_max. | [1] [16] |

| Rapid Equilibrium / Steady-State | [ES] complex forms and breaks down rapidly, reaching a steady state. | May fail for enzymes with slow catalytic steps or tight-binding inhibitors. Results in a breakdown of the hyperbolic rate equation. | [16] |

| Single-Substrate Reaction | Reaction kinetics depend on one varying substrate. | Most enzymes have multiple substrates (e.g., oxidoreductases, transferases). Requires more complex bisubstrate or ternary complex models. | [1] |

| No Allosteric Regulation | Enzyme possesses a single, independent active site. | Many metabolic enzymes are allosterically regulated by effectors, leading to cooperative kinetics not described by the standard model. | [1] |

| Idealized Assay Conditions | Parameters are constants under fixed pH, temperature, and ionic strength. | K_m and V_max are highly condition-dependent parameters. Non-physiological assay conditions (e.g., pH, buffer ions) yield non-representative values. | [1] |

A critical, often overlooked issue is the condition-dependent nature of kinetic parameters. K_m and V_max are not immutable constants but are sensitive functions of pH, temperature, ionic strength, and specific buffer components [1]. For instance, studies on glutamate dehydrogenase show it is stable in phosphate buffer but unstable in Tris buffer, while Tris and HEPES can inhibit carbamoyl-phosphate synthase [1]. Using parameters derived from non-physiological, optimized assay conditions (e.g., high pH for favorable equilibrium) in models of in vivo metabolism is a major source of error and limits the translational relevance of the data [1].

Advanced Kinetic Frameworks Beyond the Standard Model

To address these limitations, several advanced modeling frameworks have been developed.

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Enzyme Kinetic Models

| Model | Core Innovation | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Mass Action | Models all elementary steps (association, dissociation, catalysis) for forward and reverse reactions. | Most physically accurate. No simplifying assumptions. Can explicitly model all intermediates. | High parameter dimensionality (6+ parameters). Difficult to fit. Computationally expensive for networks. | Detailed mechanistic studies of a single enzyme. |

| Total QSSA (tQSSA) | Uses total substrate concentration ([S]_total) instead of free [S], relaxing the low-[E] assumption. | Accurate at high enzyme concentrations. More valid for in vivo modeling. | Mathematically complex. Requires re-derived equations for different network topologies. | Modeling enzyme cascades where enzyme levels are significant. |

| Differential QSSA (dQSSA) | Expresses the differential equations as a linear algebraic system, avoiding reactant stationary assumptions. | Retains simplicity of MM (low parameter count). Accurate for reversible reactions and complex topologies. | Does not account for all intermediate states in detail. | Systems biology models of metabolic or signaling pathways with multiple enzymes. |

| UniKP (AI/ML Framework) | Uses pretrained language models to predict k_cat, K_m, and k_cat/K_m from protein sequence and substrate structure. | High-throughput prediction. Can account for environmental factors (pH, temp). Useful for enzyme engineering. | Predictive only; requires experimental validation. Performance depends on training data. | Prioritizing enzyme candidates for directed evolution or mining novel enzyme functions. |

The dQSSA model is particularly notable for its balance of accuracy and simplicity. It has been validated in silico and in vitro, successfully predicting coenzyme inhibition in lactate dehydrogenase—a behavior the standard Michaelis-Menten model failed to capture [16]. For modeling complex biochemical networks, this reduction in parameter dimensionality without sacrificing critical kinetic features is a significant advancement [16].

Diagram: Evolution from Standard to Advanced Kinetic Models (Max Width: 760px)

Foundational Protocols for Robust Parameter Estimation

Overcoming model limitations begins with rigorous experimental design. The goal is to maximize the information content of the data collected for parameter fitting.

Optimal Experimental Design via Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) Analysis

A systematic approach to design minimizes the uncertainty in estimated parameters. The core methodology involves:

- Define a Preliminary Model: Start with the Michaelis-Menten equation or a suitable advanced model (e.g., reversible, with inhibition).

- Formulate the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM): The FIM quantifies the amount of information an observable random variable (e.g., reaction velocity) carries about an unknown parameter (K_m, V_max). For a model with parameters p, the FIM is calculated from the sensitivities of the model outputs to changes in p [5].

- Optimize an Experimental Design Criterion (D-optimality): The most common criterion is to maximize the determinant of the FIM. This minimizes the generalized variance of the parameter estimates, effectively designing an experiment where the parameters are most easily identifiable and have the smallest possible confidence intervals [5].

- Solve for Optimal Inputs: Using the preliminary parameter estimates, this optimization determines the optimal substrate feeding strategy (batch vs. fed-batch), the optimal sampling time points, and the optimal initial substrate concentrations [5].

Table 3: Experimental Design Strategy Based on FIM Analysis

| Design Factor | Optimal Strategy from FIM Analysis | Practical Improvement & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Reactor Type | Fed-batch with controlled substrate feed is superior to pure batch. | Improves parameter precision by maintaining informative substrate levels. Reduces variance of K_m estimate by up to 40% and V_max by 18% compared to batch [5]. |

| Substrate Feed Rate | Small, continuous volume flow is favorable. | Prevents substrate depletion or inhibition, keeping the reaction in a sensitive, informative kinetic regime for longer. |

| Sampling Points | Concentrated at high substrate concentration and near K_m, not uniformly spaced. | Maximizes information on both the saturation and linear phases of the kinetics. Avoids wasted measurements in uninformative regions. |

| Enzyme Addition | Adding enzyme during the experiment does not improve estimation. | The key dynamic information comes from substrate consumption and product formation, not from enzyme concentration changes. |

Protocol: Executing a Fed-Batch Experiment for Parameter Estimation

Objective: To accurately estimate K_m and V_max for an irreversible enzyme reaction using an optimal fed-batch design. Materials: Purified enzyme, substrate, assay reagents (e.g., coupling enzymes, chromogens), buffered solution at physiological pH, spectrophotometer or plate reader, precision pump for fed-batch operation. Procedure:

- Preliminary Batch Experiment: Conduct a small-scale batch experiment with a wide range of initial substrate concentrations ([S]₀) to obtain rough estimates of K_m and V_max. Fit the initial rate data to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

- Design Optimization: Input the rough parameter estimates into an FIM-based design tool (custom script or commercial software). Define constraints: total experiment duration, maximum substrate/enzyme volume, and number of allowed samples (e.g., 15-20).

- Calculate Optimal Feed Profile: The software will output an optimal substrate feed rate profile, F(t), and a set of optimal sampling times, t_i.

- Execute Fed-Batch Experiment: a. Initialize the reactor with a low starting substrate concentration (near or below K_m) in the appropriate buffer. b. Add the enzyme to initiate the reaction. c. Immediately start the substrate feed pump according to the optimal profile F(t). d. At each predetermined time t_i, withdraw a small aliquot and quench the reaction (e.g., with acid, heat, or inhibitor). e. Measure the product concentration in each quenched sample.

- Data Fitting & Validation: Fit the full time-course data of [P] vs. t to the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation (or the appropriate advanced model) using nonlinear regression (e.g., in KinTek Explorer, Python SciPy). The use of integrated rates avoids the errors associated with approximate initial rate measurements [5]. Report parameter estimates with 95% confidence intervals.

Diagram: Optimal Fed-Batch Parameter Estimation Workflow (Max Width: 760px)

Moving beyond simplifying assumptions requires leveraging a suite of modern databases, standards, and software tools.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Resources

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function & Relevance | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA | Comprehensive Enzyme Database | Repository of millions of experimentally derived kinetic parameters, organized by EC number [1]. | Primary source for literature parameter values. Essential for initial estimates and comparative analysis. |

| SABIO-RK | Kinetic Reaction Database | Curated database of biochemical reaction kinetics, including systems biology parameters [1]. | Provides contextualized kinetic data suitable for pathway modeling. |

| STRENDA Guidelines | Reporting Standards | A checklist ensuring complete reporting of experimental conditions (pH, temp, buffer, assay method) in publications [1]. | Critical for assessing data fitness-for-purpose. Promotes reproducibility and reliability of published parameters. |

| IUBMB ExplorEnz | Enzyme Nomenclature Database | Definitive source for EC numbers and official enzyme names, including synonyms [1]. | Prevents misidentification of enzymes, a common source of error when sourcing parameters. |

| KinTek Explorer | Simulation & Fitting Software | Advanced software for fitting kinetic time-course data to complex mechanistic models [17]. | Allows fitting to integrated rate laws and complex multi-step mechanisms, moving beyond initial rate approximations. |

| UniKP Framework | AI/ML Prediction Tool | Unified deep learning model to predict k_cat, K_m, and k_cat/K_m from protein sequence and substrate structure [6]. | Accelerates enzyme discovery and engineering by providing high-quality prior estimates, guiding experimental focus. |

The standard Michaelis-Menten model remains an indispensable tool, but its blind application is a significant source of error in biochemical research and translation. Recognizing its limits is the first step toward robust and predictive enzyme kinetics. This involves a tripartite strategy: (1) adopting advanced kinetic frameworks like dQSSA for systems modeling where standard assumptions fail; (2) implementing rigorous, optimally designed experiments that maximize information yield, such as fed-batch protocols analyzed via FIM; and (3) leveraging curated databases, reporting standards, and modern software for data validation, fitting, and prediction.

For researchers and drug developers, this transition is imperative. Accurate kinetic parameters are the bedrock for understanding metabolic flux, designing effective inhibitors, and engineering enzymes. By moving beyond simplifying assumptions, the field can generate data that truly reflects biological complexity, thereby enabling more reliable models, more predictive drug discovery, and more successful biotechnological applications.

From Theory to Bench: A Practical Guide to Initial Rate and Progress Curve Assays

The accurate estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat and Km) is a foundational task in biochemistry, metabolic engineering, and drug discovery [18]. For decades, the determination of initial velocity under steady-state conditions has been the textbook-prescribed standard. This approach relies on measuring the linear, early phase of a reaction where substrate depletion is minimal (typically <10%) and product accumulation is negligible [4]. However, this method imposes stringent practical limitations, including the need for sensitive continuous assays, precise determination of linearity, and sometimes wasteful use of substrate at high concentrations.

In parallel, the analysis of full time-course or progress curve data offers a complementary paradigm. This methodology utilizes the entire reaction trajectory, from initiation to completion or equilibrium, by applying integrated forms of kinetic equations [19] [4]. While historically underutilized due to computational complexity, modern non-linear regression software has revived interest in this approach. Its principal advantage lies in extracting maximal information from a single experiment, which is particularly valuable when substrate is limited, assays are discontinuous (e.g., HPLC-based), or when investigating complex kinetic phenomena [20].

This guide, framed within broader research on enzyme kinetic parameter estimation, provides a technical framework for researchers to make an informed choice between these two fundamental methodologies. The decision is not merely procedural but deeply influences the accuracy, efficiency, and biological relevance of the derived kinetic constants.

Theoretical and Practical Comparison of the Two Methodologies

The choice between initial velocity and progress curve assays is guided by the underlying reaction mechanism, the presence of interfering factors, and practical experimental constraints. The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each approach.

Table 1: Core Comparison of Initial Velocity and Progress Curve Assay Methodologies

| Aspect | Initial Velocity Assays | Full Time-Course (Progress Curve) Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Measures slope (d[P]/dt) at time zero, under steady-state conditions where [S] ≈ [S]0 [4]. | Fits the entire [P] vs. time trace to an integrated rate equation (e.g., Integrated Michaelis-Menten Equation) [19] [4]. |

| Key Assumption | Product formation is linear with time; [S] is essentially constant. No significant inhibition by product or substrate [19]. | The kinetic model (including inhibition terms) is correctly specified. Enzyme is stable over the full time course (verified via Selwyn's test) [4]. |

| Data Requirement | One initial rate value per substrate concentration. Requires multiple reactions at different [S] to construct a Michaelis-Menten plot. | One progress curve per substrate concentration can, in principle, yield both Vmax and Km [4]. |

| Optimal Substrate Conversion | Typically limited to ≤10% of total substrate to ensure linearity. | Can analyze data up to high conversion (e.g., 70%), explicitly accounting for [S] depletion [4]. |

| Handling Product Inhibition | Problematic. Inhibitor (product) concentration changes during assay, making steady-state measurements inaccurate. Requires very early time points [19]. | Superior. Integrated equations can directly incorporate product inhibition terms (competitive, uncompetitive, mixed), yielding accurate constants [19]. |

| Detecting Kinetic Complexity | May miss transient phases (burst/lag). Assumes immediate steady-state [20]. | Essential for detection. Reveals hysteretic behavior, slow transitions, and enzyme inactivation that distort initial rate measurements [20]. |

| Practical Efficiency | High throughput possible with continuous readers. Can be wasteful of substrate at high [S]. | Efficient with scarce or valuable substrate. Discontinuous assays (e.g., HPLC) are less labor-intensive per data point [4]. |

| Computational Analysis | Simple linear regression for initial slopes, followed by non-linear fit of v vs. [S]. | Requires direct non-linear regression of time-series data using integrated equations. More complex but feasible with modern software [19]. |

Identifying and Managing Kinetic Complexities

A critical advantage of progress curve analysis is its ability to detect and diagnose atypical kinetic behaviors that invalidate standard initial velocity assumptions.

Hysteretic Enzymes: These enzymes exhibit a slow transition between conformational states upon mixing with substrate, leading to time-dependent activity. A burst phase (initial velocity Vi > steady-state velocity Vss) or a lag phase (Vi < Vss) is observed [20]. Initial rate measurements taken during these transitions are not representative of the enzyme's functional state. Full progress curve analysis quantifies the transition rate constant (k) and amplitude, providing mechanistic insight [20].

Product Inhibition: It is estimated that a large majority of enzymes are inhibited by their own product [19]. In initial velocity assays, even minimal product accumulation can distort measurements. The integrated Michaelis-Menten equation (IMME) with inhibition terms allows for the accurate simultaneous determination of Km, Vmax, and the inhibition constant (Kic or Kiu) [19]. Studies show that when product inhibition is present, fitting initial velocity data to a standard model can misidentify the inhibition mechanism (e.g., suggesting uncompetitive inhibition), whereas IMME correctly identifies it as competitive [19].

Table 2: Protocol for Diagnosing Kinetic Complexities via Progress Curve Analysis

| Step | Action | Rationale & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Collection | Record continuous product formation for a duration sufficient to reach at least 50-70% substrate conversion, at a substrate concentration near the estimated Km. | A single progress curve at an intermediate [S] is most sensitive to deviations from ideal hyperbolic kinetics [20]. |

| 2. Visual Inspection | Plot [P] vs. time. Look for obvious curvature in the initial phase (non-linear product formation). | A concave-down curve suggests a burst; concave-up suggests a lag. A purely hyperbolic curve is ideal [20]. |

| 3. Derivative Analysis | Calculate and plot the instantaneous reaction rate (d[P]/dt) vs. time or vs. [P]. | A constant rate indicates ideal behavior. A rate that changes systematically early in the reaction indicates hysteresis. A rate that decreases faster than predicted by [S] depletion alone suggests product inhibition [20]. |

| 4. Model Fitting | Fit the progress curve to a series of nested integrated models using non-linear regression (e.g., in GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot, or custom Python/R scripts). | 1. Model A: Standard IMME (no inhibition). 2. Model B: IMME with competitive product inhibition. 3. Model C: IMME with burst or lag phase equation [20] [19]. |

| 5. Model Discrimination | Use statistical criteria (Akaike Information Criterion - AIC, F-test) to select the best-fitting model [19]. | The model with the lowest AIC is preferred. A significant improvement from Model A to B confirms product inhibition. A preference for Model C confirms hysteretic behavior. |

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Workflow for Kinetic Behavior

Experimental Protocol for Robust Progress Curve Analysis

This protocol outlines a generalized method for acquiring and analyzing progress curve data suitable for estimating kcat and Km, even in the presence of product inhibition.

Reagent and Instrument Preparation

- Enzyme Solution: Prepare in appropriate reaction buffer. Determine a concentration that yields a complete reaction over a practically measurable timeframe (minutes to hours). Perform a Selwyn test (progress curves at two different enzyme concentrations should overlay when plotted as [P] vs. time × [E]) to confirm enzyme stability [4].

- Substrate Solutions: Prepare a minimum of 6-8 concentrations spanning 0.2Km to 5Km (estimated from literature or preliminary experiments). Use the same stock to ensure consistency.

- Detection System: Calibrate spectrophotometer, fluorometer, or HPLC to ensure linear response over the expected product concentration range. For discontinuous assays, plan precise quenching times.

Reaction Execution and Data Collection

- Pre-incubate all reaction components (except initiating agent) at the assay temperature.

- Initiate the reaction by adding enzyme or substrate. For discontinuous assays, initiate multiple identical reactions staggered in time.

- For continuous assays: Record signal (e.g., absorbance) at high frequency (e.g., 1-2 sec intervals) for the initial phase, decreasing frequency as the reaction slows.

- For discontinuous assays: Quench reaction aliquots at precisely timed intervals (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 300, 600, 1800 sec) to capture the full curve shape. Analyze quenched samples for product/substrate concentration.

- Convert raw signal (e.g., absorbance) to product concentration [P] using a calibration curve.

- Repeat for all substrate concentrations. Include a no-enzyme control for each [S] to account for non-enzymatic background.

Data Analysis via Non-Linear Regression

The core step is fitting the [P] vs. t data to the Integrated Michaelis-Menten Equation (IMME). For the simplest case with no inhibition:

[P] = V_max * t - K_m * ln(1 - ([P]/[S]_0))

However, if product inhibition is suspected (a common case), the appropriate model must be used. For competitive product inhibition, the IMME becomes:

t = (K_m/V_max) * (1 + [P]/K_ic) * ln([S]_0/([S]_0-[P])) + [P]/V_max

Where Kic is the competitive inhibition constant for the product.

Procedure:

- Input data into analysis software (e.g., GraphPad Prism "nonlinear regression").

- Input the appropriate equation as the user-defined model.

- Fit each progress curve (at a single [S]0) individually. The fit should yield values for Vmax and Km (and Kic if using the inhibition model).

[S]_0is a known constant. - The derived Vmax should be proportional to enzyme concentration. The Km (and Kic) should be consistent across curves from different [S]0.

- Perform global fitting if higher precision is desired: Fit all progress curves (all [S]0) simultaneously to a shared model, sharing the parameters Km and Kic, while allowing Vmax to be shared or scaled with [E] [19].

Diagram 2: Progress Curve Data Analysis Pathway

Integration with Modern Computational and High-Throughput Approaches

The field of enzyme kinetics is being transformed by artificial intelligence and large-scale data integration, which impacts experimental design choices.

Predictive Modeling: Deep learning frameworks like CataPro and UniKP predict kcat, Km, and kcat/K*m from enzyme sequences and substrate structures [21] [6]. These models are trained on large, curated datasets extracted from literature. Their performance, however, is contingent on the quality and relevance of the underlying experimental kinetic data. Progress curve-derived parameters, which more accurately reflect true mechanistic constants (especially in the presence of product inhibition), provide a superior foundation for training such models [19] [14].

Data Mining: Tools like EnzyExtract use large language models to automatically extract kinetic parameters and experimental conditions from millions of publications, moving beyond structured databases like BRENDA [14]. This creates vast, unbiased datasets for training next-generation predictors. Researchers generating new kinetic data should consider that well-documented progress curve analyses, which capture more complex kinetics, will be more valuable for these community resources.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS): In drug discovery, initial velocity assays dominate primary HTS due to their speed and simplicity in 384- or 1536-well formats [18]. Universal fluorescent detection platforms (e.g., Transcreener) that measure common products like ADP are popular for their robustness [18]. However, for mechanism-of-action studies on confirmed hits, progress curve analysis becomes critical to identify time-dependent inhibition, slow-binding kinetics, or enzyme inactivation—phenomena that are invisible in single-timepoint HTS data [20] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetic Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function & Specification | Consideration for Initial Velocity vs. Progress Curve |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | Biological catalyst. Should be >95% pure, with accurately determined concentration (A280 or activity-based). | Progress Curve: Stability over the longer assay duration is paramount (validate with Selwyn's test). |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. High purity, solubilized in assay buffer or DMSO (<1% final). | Progress Curve: More efficient with scarce/expensive substrate, as one curve uses one aliquot. |

| Detection Probe | Molecule that enables monitoring of reaction. E.g., chromogenic/fluorogenic substrate analog, coupled enzyme system, or labeled antibody for ELISA. | Initial Velocity: Probes must give linear signal over short time window. Progress Curve: Probe signal must remain linear over the full concentration range and time course. Coupled systems must not become rate-limiting. |

| Assay Buffer | Aqueous solution maintaining pH, ionic strength, and cofactors. Common: Tris, HEPES, PBS. Includes essential Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺, DTT, etc. | Both: Must be optimized for enzyme activity. Use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach for efficient optimization [22]. pH and temperature control are critical [23]. |

| Quenching Solution | For discontinuous assays. Stops reaction instantly (e.g., strong acid, base, denaturant, or chelating agent). | Progress Curve: Quenching must be immediate and complete at all time points to accurately define the reaction trajectory. |

| Microplate / Cuvettes | Reaction vessel. Clear or black-walled plates for absorbance/fluorescence. | Initial Velocity: 384-well plates common for HTS. Edge effects and evaporation must be controlled [23]. Progress Curve: Temperature uniformity across the plate for the entire run is critical. |

| Detection Instrument | Spectrophotometer, fluorometer, luminometer, or HPLC/MS system. | Initial Velocity: Requires fast kinetic reading capability. Progress Curve: Requires stable, long-term reading or precise automation for discontinuous sampling. |

The selection between initial velocity and progress curve methodologies should be a deliberate, hypothesis-driven choice. The following framework can guide researchers:

Use Initial Velocity Assays when:

- The enzyme is well-characterized with simple Michaelis-Menten kinetics and no known product inhibition.

- The primary goal is high-throughput screening (e.g., drug discovery).

- You have a robust, continuous, and linear detection system.

- Substrate is inexpensive and abundant.

Default to Progress Curve Analysis when:

- Investigating a new or poorly characterized enzyme.

- Product inhibition is suspected or likely (which is most cases) [19].

- Substrate is limiting, expensive, or the assay is discontinuous (HPLC/MS).

- There is a suspicion of time-dependent phenomena (burst, lag, hysteresis, or slow-onset inhibition) [20].

- The goal is to generate highly accurate, mechanism-rich kinetic constants for predictive model training or publication.

The future of enzyme kinetics lies in the convergence of rigorous experimental design—often leveraging the rich information content of progress curves—with powerful computational predictions fueled by large-scale data extraction. By choosing the appropriate methodology, researchers ensure that the foundational kinetic parameters they measure are not just numbers, but true reflections of catalytic mechanism.

The accurate estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters, principally the Michaelis constant (Kₘ) and the maximum reaction velocity (Vₘₐₓ), is a fundamental pursuit in biochemistry with critical applications in basic research, drug discovery, and systems biology [1]. This technical guide examines the evolution of analytical methodologies from traditional linear transformations, epitomized by the Lineweaver-Burk plot, to modern direct nonlinear regression and progress curve analysis. Framed within a thesis on the fundamentals of parameter estimation, we demonstrate through comparative simulation studies that nonlinear methods provide superior accuracy and precision, particularly under realistic experimental error structures [24] [15]. The discussion extends to optimal experimental design, parameter reliability, and the practical implementation of these techniques, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select and apply the most robust analytical framework for their enzyme kinetic studies [5] [1].

Enzyme kinetics provides the quantitative framework for understanding catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity, and regulatory mechanisms. The parameters derived from kinetic analysis—Kₘ, a measure of substrate affinity, and Vₘₐₓ, the theoretical maximum rate—are not mere constants but conditional descriptors essential for modeling metabolic pathways, designing assays, evaluating enzyme inhibitors (a cornerstone of pharmaceutical development), and integrating enzymatic data into systems biology models [1]. The seminal Michaelis-Menten equation, v = (Vₘₐₓ * [S]) / (Kₘ + [S]), where v is the initial velocity and [S] is the substrate concentration, describes the hyperbolic relationship underlying this analysis [25].

The historical challenge has been the accurate extraction of these parameters from experimental data. For decades, linearization methods, which transform the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation into a straight-line plot, were the standard due to their computational simplicity and visual accessibility in an era before ubiquitous computing power [26]. The most famous of these, the Lineweaver-Burk (double reciprocal) plot, represented a major step forward in 1934 [26]. However, the pursuit of accuracy and statistical rigor has driven a paradigm shift toward direct nonlinear regression, which fits the untransformed data directly to the Michaelis-Menten model [24] [27]. This guide traces this methodological evolution, critically evaluates each approach, and provides a contemporary protocol for reliable kinetic parameter estimation.

Historical Foundation: The Lineweaver-Burk Plot and Linearization Methods

The Lineweaver-Burk plot is generated by taking the reciprocal of both sides of the Michaelis-Menten equation, yielding the linear form: 1/v = (Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ)*(1/[S]) + 1/Vₘₐₓ [26] [28]. A plot of 1/v versus 1/[S] yields a straight line with:

- Slope = Kₘ / Vₘₐₓ

- Y-intercept = 1 / Vₘₐₓ

- X-intercept = -1 / Kₘ

This transformation made graphical determination of Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ straightforward and became a ubiquitous pedagogical tool. Its utility extended to the diagnostic analysis of enzyme inhibition [29] [28]:

- Competitive Inhibition: Lines intersect on the y-axis (1/Vₘₐₓ unchanged), with slopes increasing.

- Non-Competitive Inhibition: Lines intersect on the x-axis (Kₘ unchanged), with y-intercepts increasing.

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: Parallel lines, with both intercepts changed.

Other linear transformations were developed to mitigate some limitations, notably the Eadie-Hofstee plot (v vs. v/[S]) and the Hanes-Woolf plot ([S]/v vs. [S]) [24] [30].

Inherent Limitations and Statistical Shortcomings

Despite their historical role, linear transformations introduce significant statistical distortions that compromise parameter reliability [24] [26]:

- Error Distortion: Experimental errors in the initial velocity (

v) are non-uniformly amplified by reciprocal transformation. A constant absolute error invbecomes a large relative error in1/vat low velocities (high1/vvalues), giving undue weight to data points collected at low substrate concentrations and distorting the regression [26]. - Violation of Regression Assumptions: Ordinary linear regression assumes constant variance (homoscedasticity) and normally distributed errors in the dependent variable (

1/v). The transformation invalidates these assumptions, making standard error estimates for Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ unreliable [24]. - Data Exclusion: The method typically relies on initial velocity measurements from multiple independent reaction time courses at different

[S], which can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Linear Transformation Methods

| Method (Plot) | Linear Form | X-axis | Y-axis | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk | 1/v = (Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ)*(1/[S]) + 1/Vₘₐₓ | 1/[S] | 1/v | Severely distorts error structure, overweights low [S] data [26]. |

| Eadie-Hofstee | v = Vₘₐₓ - Kₘ*(v/[S]) | v/[S] | v | Both variables (v and v/[S]) are subject to error, violating regression assumptions. |

| Hanes-Woolf | [S]/v = (1/Vₘₐₓ)[S] + Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ | [S] | [S]/v | Minimizes, but does not eliminate, error distortion [30]. |

Diagram 1: Workflow of traditional linearization methods for parameter estimation.

The Modern Standard: Direct Nonlinear Regression

Direct nonlinear regression (NLR) fits the untransformed experimental data (v vs. [S]) directly to the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten model using an iterative algorithm that minimizes the sum of squared residuals (the difference between observed and predicted v) [27]. This approach is now considered the gold standard for routine parameter estimation [24] [1].

Advantages Over Linearization

- Statistical Integrity: NLR operates on the primary data, preserving the true error structure. It provides accurate confidence intervals for the parameters.

- Accuracy and Precision: Simulation studies conclusively show NLR yields more accurate and precise estimates of Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ compared to any linear transformation method [24].

- Generalizability: The same computational framework can fit more complex models (e.g., with inhibition, cooperativity) without the need for new linear transformations [27].

Practical Implementation

NLR requires initial parameter estimates to begin the iterative fitting process. Preliminary estimates can be obtained from a simple linear plot or known literature values. The process is computationally intensive but is seamlessly handled by modern software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, R, Python/SciPy, NONMEM) [24] [27].

Advanced Paradigm: Progress Curve and Full Time-Course Analysis

A powerful extension beyond initial velocity analysis is the fitting of the entire reaction progress curve (substrate or product concentration vs. time) [15]. This method uses the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation or numerically solves the differential equation to model the temporal trajectory of a single reaction.

Methodology and Benefits

Instead of measuring initial rates from multiple reaction vessels at a single time point, this method monitors one reaction to completion. Data fitting involves solving -d[S]/dt = (Vₘₐₓ * [S]) / (Kₘ + [S]) [24]. A 2025 study highlights approaches like spline interpolation of progress curves coupled with nonlinear optimization, which shows low dependence on initial parameter guesses and high robustness [15].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Estimation Methods (Simulation Data) [24]

| Estimation Method | Description | Data Used | Relative Accuracy & Precision | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB (Lineweaver-Burk) | Linear fit to 1/v vs. 1/[S] | Initial Velocities (vᵢ) | Lowest | Highly inaccurate with combined error models. |

| EH (Eadie-Hofstee) | Linear fit to v vs. v/[S] | Initial Velocities (vᵢ) | Low | Poor performance due to error in both variables. |

| NL (Nonlinear Regression) | Nonlinear fit to v vs. [S] | Initial Velocities (vᵢ) | High | Superior to linear methods for initial rate data. |

| NM (Full Time-Course) | Nonlinear fit to [S] vs. time | Full Progress Curve | Highest | Most accurate and precise, optimal use of all data. |

Key Simulation Result: A 2018 Monte Carlo simulation (1000 replicates) comparing five methods found that nonlinear regression of full time-course data (NM) provided the most accurate and precise parameter estimates. The superiority was most pronounced under a combined (additive + proportional) error model, which reflects real experimental conditions more accurately than a simple additive error model [24].

Experimental Design for Optimal Estimation

The precision of estimated parameters depends critically on experimental design. Optimal design theory, analyzing the Fisher Information Matrix, provides guidelines to maximize information content [5]:

- Substrate Concentration Range: Data should adequately define the hyperbolic curve. Optimal designs often include replicates near the expected Kₘ, at very low [S], and at saturating [S] to define the asymptote (Vₘₐₓ) [5].

- Fed-Batch Experiments: For progress curve analysis, a fed-batch design with controlled substrate feeding can improve parameter identifiability compared to a simple batch experiment [5].

- Error Consideration: When relative error is constant, measurements at the highest and lowest feasible substrate concentrations are favorable [5].

Diagram 2: Decision workflow for selecting modern kinetic analysis methods.

Practical Protocols for Reliable Parameter Estimation

Protocol A: Initial Velocity Analysis with Nonlinear Regression

- Assay Development: Establish a linear assay for product formation or substrate depletion under fixed temperature, pH, and enzyme concentration [1].

- Substrate Range: Use at least 8-10 substrate concentrations, spaced geometrically (e.g., 0.2Kₘ, 0.5Kₘ, 1Kₘ, 2Kₘ, 5Kₘ, 10Kₘ) to adequately define the curve. Include replicates.

- Initial Rate Measurement: For each [S], measure the linear change in signal over time, ensuring ≤10% substrate depletion to maintain constant velocity.

- Data Fitting:

- Input data pairs ([S], v) into statistical software.

- Use the Michaelis-Menten model:

v = (Vₘₐₓ * [S]) / (Kₘ + [S]). - Provide sensible initial estimates (e.g., from a quick Eadie-Hofstee plot).

- Perform weighted nonlinear regression if error variance is not constant.

- Report best-fit parameters with 95% confidence intervals.

Protocol B: Progress Curve Analysis

- Reaction Initiation: In a single vessel, initiate reaction at a substrate concentration near or above the expected Kₘ.

- Continuous Monitoring: Use a continuous assay (e.g., spectrophotometric) to record product formation or substrate depletion at frequent time intervals until the reaction approaches completion.

- Data Fitting:

- Input time-course data (t, [S] or [P]).

- Fit to the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation or numerically solve the differential equation.

- For more robust fitting, especially with noisy data, consider using a spline interpolation approach as described by recent methodologies [15].

- Estimate Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ simultaneously.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Item / Software | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Reagents | Purified Enzyme Preparation | The catalyst of interest; source and purity critically affect parameters [1]. |

| Characterized Substrate | Reactant molecule; use physiologically relevant forms where possible [1]. | |

| Appropriate Assay Buffer | Maintains pH, ionic strength, and cofactor conditions; choice can influence kinetics [1]. | |

| Stopping Reagent (for endpoint assays) | Halts reaction at precise time for product quantification. | |

| Computational Tools | GraphPad Prism | User-friendly desktop software with robust nonlinear regression and enzyme kinetics modules. |

R with nls/drc packages |

Open-source environment for advanced fitting, simulation, and custom analysis [24]. | |

| Python (SciPy, NumPy) | Flexible programming platform for data fitting and modeling. | |

| NONMEM | Advanced tool for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling, used in complex kinetic/pharmacokinetic studies [24]. | |

| Data Resources | BRENDA Database | Comprehensive repository of enzyme functional data, including kinetic parameters [1]. |

| STRENDA Guidelines | Standards for Reporting Enzymology Data; ensure reported parameters are reliable and reproducible [1]. |

The journey from the Lineweaver-Burk plot to direct nonlinear regression represents a triumph of statistical rigor over convenience. While linear plots retain didactic value for illustrating inhibition patterns, they are obsolete for primary parameter estimation in research. The current standard—nonlinear regression of initial velocity data—should be the default method for most studies. For maximal efficiency and accuracy, particularly with unstable enzymes or scarce substrates, progress curve analysis coupled with modern fitting algorithms represents the cutting edge [15].

Future directions in enzyme kinetic parameter estimation will involve tighter integration with systems biology modeling, requiring parameters determined under physiologically relevant conditions [1]. The adoption of standardized reporting guidelines (STRENDA) is crucial to building reliable kinetic databases for in silico modeling [1]. As computational power increases and robust algorithms become more accessible, the direct, model-based analysis of kinetic data will continue to solidify its role as the indispensable foundation for quantitative enzymology and its applications in biotechnology and drug discovery.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to modern software tools for simulation and global fitting, specifically within the context of enzyme kinetic parameter estimation. Accurate determination of kinetic parameters ((Km), (k{cat}), (k{on}), (k{off}), etc.) is foundational to mechanistic enzymology and drug development, where understanding target engagement and inhibition is critical. Traditional linearization methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk) are often inadequate for complex, multi-step mechanisms, leading to biased estimates. This document explores the paradigm shift towards computational approaches that directly fit numerical integration of differential equations to full progress curve data across multiple experimental conditions—a process known as global fitting. This methodology, central to a broader thesis on enzyme kinetic basics, provides robust, mechanism-based parameter estimation essential for modern research and pharmaceutical sciences.

Core Methodology: Global Kinetic Analysis

Conceptual Foundation

Global fitting refines a single set of kinetic parameters by minimizing the difference between simulated and observed data from all experiments simultaneously. This contrasts with local fitting of individual datasets. The residuals ((\chi^2)) are calculated across the entire experimental matrix:

[ \chi^2 = \sum{i=1}^{n} \sum{j=1}^{m} \frac{[Y{obs}(t{i,j}) - Y{sim}(t{i,j}, \mathbf{p})]^2}{\sigma_{i,j}^2} ]

where (Y{obs}) and (Y{sim}) are observed and simulated data points, (\mathbf{p}) is the vector of fitted parameters, and (\sigma) is the measurement error. The software solves the system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) describing the proposed kinetic mechanism for each experimental condition.

Experimental Protocol for Global Analysis

The following protocol is essential for generating data suitable for global fitting analysis:

Experimental Design:

- Define the putative kinetic mechanism (e.g., ordered ternary-complex, ping-pong, allosteric).

- Design a matrix of progress curve experiments varying multiple factors: substrate concentration(s), inhibitor concentration, enzyme concentration, and reaction time.

- Include single-turnover (enzyme in excess) and multiple-turnover (substrate in excess) conditions to delineate individual rate constants.

Data Collection:

- Use a continuous assay (e.g., fluorescence, absorbance) to collect dense time-course data (progress curves).

- Perform replicates at each condition to estimate experimental variance ((\sigma)).

- Record essential control curves (no enzyme, no substrate, etc.).

Data Preprocessing:

- Correct progress curves for background signal and instrument drift.

- Normalize data if using spectroscopic methods with path length or quenching variations.

- Assemble all data curves and their associated experimental conditions (ligand concentrations, etc.) into the software's required input format.

Computational Fitting:

- Input the proposed kinetic model as a set of chemical equations or ODEs.

- Load the preprocessed experimental data matrix.

- Set initial parameter estimates (often from literature or preliminary analysis).

- Define which parameters are to be globally fitted and which may vary locally per dataset.

- Execute the fitting algorithm to minimize global (\chi^2).

Model Evaluation: