Mastering Kinetic Parameter Estimation: A Comprehensive Guide to Global Optimization Methods for Biomedical Research

Accurate kinetic parameters are fundamental to constructing predictive models of biochemical systems, drug-target interactions, and cellular signaling pathways.

Mastering Kinetic Parameter Estimation: A Comprehensive Guide to Global Optimization Methods for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurate kinetic parameters are fundamental to constructing predictive models of biochemical systems, drug-target interactions, and cellular signaling pathways. This article provides a complete methodological guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying global optimization (GO) techniques to estimate these critical parameters. We begin by establishing the core challenges of kinetic modeling and the complex, multimodal nature of the parameter search space. The article then systematically explores major classes of GO algorithms—from stochastic methods like Particle Swarm Optimization to deterministic frameworks and modern machine learning-aided hybrids—detailing their application to biological systems. Practical guidance is offered for algorithm selection, performance tuning, and troubleshooting common issues such as parameter non-identifiability and premature convergence. Finally, we present rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses of algorithm performance across real-world case studies. This integrated resource equips scientists to robustly estimate kinetic parameters, thereby enhancing the reliability of computational models in drug discovery and systems biology.

The Challenge of Kinetic Landscapes: Why Global Optimization is Essential for Parameter Estimation

Kinetic parameters, such as enzyme turnover numbers (kcat), Michaelis constants (Km), and inhibition constants, are the fundamental numerical values that define the rates of biochemical reactions within mechanistic dynamic models [1]. These models, typically formulated as systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), provide an interpretable representation of biological dynamics by explicitly incorporating biochemical principles [2] [1]. The accuracy of these parameters directly determines a model's predictive power for simulating cellular metabolism, signaling pathway dynamics, and pharmacodynamic responses. Consequently, the problem of accurately defining these parameters is a cornerstone of predictive systems biology, metabolic engineering, and drug development.

The central challenge is that these parameters are notoriously difficult to determine. Experimental measurement is time-consuming, costly, and often infeasible for the thousands of reactions in genome-scale networks [3]. This results in a significant knowledge gap; while protein sequence databases contain hundreds of millions of entries, experimentally measured kinetic parameters are available for only a tiny fraction [3]. Furthermore, even when parameters are available, they may be derived from in vitro conditions that poorly reflect the crowded, regulated intracellular environment. The problem is therefore two-fold: a severe data scarcity and the computational optimization challenge of inferring parameter sets that are consistent with often sparse and noisy experimental data, such as metabolite concentration time courses or steady-state fluxes [2] [1].

Inaccurate or poorly constrained parameters lead to models with low predictive and explanatory value. They fail to capture the correct system dynamics, produce unreliable simulations of genetic interventions or drug effects, and ultimately undermine the model-based decision-making process [1]. This article details the frameworks and protocols for addressing this critical problem through advanced global optimization methods, providing researchers with the tools to enhance the accuracy and reliability of their biological models.

The process of finding a set of kinetic parameters that minimizes the difference between model predictions and experimental data is a high-dimensional, non-convex global optimization problem. The search space is vast, riddled with local minima, and computationally expensive to evaluate due to the need for numerical ODE integration [1] [4]. Global optimization (GO) methods are essential for navigating this complex landscape, and they are broadly categorized into stochastic and deterministic strategies [4].

Stochastic Methods incorporate randomness to explore the parameter space broadly and avoid premature convergence to local minima. They are particularly well-suited for the initial exploration of complex, high-dimensional landscapes [4].

- Evolutionary Algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms): Operate on a population of parameter sets, applying selection, crossover, and mutation operators to evolve towards optimal solutions [4].

- Swarm Intelligence (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization - PSO): Inspired by social behavior, particles (parameter sets) move through the search space, influenced by their own best position and the swarm's best position [5] [4]. Recent advances formalize such approaches using kinetic theory, providing robust convergence analysis [5].

- Bayesian Optimization (BO): A sample-efficient sequential strategy ideal for optimizing expensive "black-box" functions. It builds a probabilistic surrogate model (typically a Gaussian Process) of the objective function and uses an acquisition function to decide the next most informative parameter set to evaluate [6]. This is highly effective when experimental iterations are costly and time-consuming.

Deterministic Methods rely on analytical information and follow defined rules. While precise, they can be computationally intensive and may struggle with landscapes containing many minima [4].

- Gradient-Based Methods: Utilize local gradient information to descend to a minimum. They are efficient for local refinement but require good initial guesses and differentiable systems.

- Branch-and-Bound Algorithms: Systematically divide the search space, bounding the objective function to prune suboptimal regions. They can guarantee a global minimum but become intractable for very high dimensions.

In practice, a hybrid approach is often most effective: using a stochastic method for broad global exploration followed by a deterministic method for local refinement of promising candidate solutions [4].

Table 1: Comparison of Global Optimization Methods for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Method Category | Key Algorithms | Advantages for Kinetic Parameter Estimation | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithm (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA) | Excellent at escaping local minima; suitable for non-differentiable problems; requires only objective function evaluation [5] [4]. | May require many function evaluations; convergence can be slow; final solution may not be a precise local minimum. |

| Bayesian | Bayesian Optimization (BO) with Gaussian Processes | Extremely sample-efficient; ideal for expensive experimental campaigns; provides uncertainty estimates for predictions [6]. | Surrogate model complexity grows with data; performance degrades in very high dimensions (>20-30). |

| Deterministic | Gradient Descent, Sequential Quadratic Programming | Fast local convergence; efficient for final refinement. | Requires derivative information; highly sensitive to initial guess; gets trapped in local minima. |

| Hybrid | Global stochastic search + local deterministic refinement | Balances broad exploration with precise exploitation; often the most practical and robust strategy [4]. | Requires tuning of two algorithms; can be computationally complex to implement. |

Current Frameworks for Kinetic Model Construction and Parameterization

The systems biology community has developed several computational frameworks to systematize the construction and parameterization of kinetic models. These tools integrate stoichiometric networks, thermodynamic constraints, and various parameter determination strategies [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Kinetic Modeling Frameworks and Their Parameterization Strategies [2]

| Framework | Core Parameter Determination Strategy | Key Requirements | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKiMpy | Sampling: Generates populations of thermodynamically feasible kinetic parameters consistent with steady-state data. | Steady-state fluxes & concentrations; thermodynamic data. | Efficient, parallelizable; ensures physiologically relevant timescales; automates rate law assignment. | Does not perform explicit fitting to time-resolved data. |

| MASSpy | Sampling (primarily mass-action) integrated with constraint-based modeling. | Steady-state fluxes & concentrations. | Tight integration with COBRA tools; computationally efficient. | Limited to mass-action kinetics by default. |

| KETCHUP | Fitting to perturbation data from wild-type and mutant strains. | Extensive multi-condition flux and concentration data. | Efficient, parallelizable, and scalable parametrization. | Requires large dataset of perturbation experiments. |

| pyPESTO | Multi-method estimation (local/global optimization, Bayesian inference). | Custom objective function and experimental data. | Flexible, allows testing of different optimization techniques on the same model [2] [1]. | Does not provide built-in structural identifiability analysis. |

| Maud | Bayesian statistical inference for parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification. | Various omics datasets. | Quantifies uncertainty in parameter estimates rigorously. | Computationally intensive; not yet applied to genome-scale models. |

Complementing these general frameworks, machine learning is now providing powerful, data-driven methods for direct parameter prediction. The UniKP framework uses pre-trained language models to convert protein sequences and substrate structures into numerical representations, which are then used to predict kcat, Km, and kcat/Km with high accuracy [3]. Its two-layer variant, EF-UniKP, can further incorporate environmental factors like pH and temperature [3]. Similarly, DeePMO employs an iterative deep learning strategy for high-dimensional parameter optimization, successfully applied to complex chemical kinetic models [7]. These tools are rapidly reducing the dependency on scarce experimental data.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Kinetic Model Parameterization

Protocols for Kinetic Parameter Estimation and Model Calibration

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation via Global Optimization with pyPESTO

This protocol outlines steps for estimating parameters using experimental time-course data within a flexible optimization environment [2] [1].

Model and Data Formalization:

- Encode your ODE model in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML).

- Compile experimental data (e.g., metabolite concentrations over time under different perturbations) into a standardized data format. Define measurement and noise models.

Problem Definition in pyPESTO:

- Import the SBML model and data. Define the objective function, typically a log-likelihood or least-squares function measuring the discrepancy between model simulations and data.

- Set plausible lower and upper bounds for all parameters to be estimated.

Multi-Start Optimization:

- Perform a multi-start local optimization. Sample

N(e.g., 100-1000) initial parameter sets uniformly within the defined bounds. - For each start point, run a local gradient-based optimizer (e.g., BFGS) to find a local minimum of the objective function. This strategy helps probe the landscape for the global minimum [1].

- Perform a multi-start local optimization. Sample

Analysis and Selection:

- Cluster the results from all start points based on final parameter values and objective function value.

- Select the parameter set with the lowest objective function value as the best estimate. Analyze the distribution of results to assess problem difficulty and the presence of multiple plausible minima.

Protocol 2: Sample-Efficient Optimization Using Bayesian Optimization (BioKernel)

This protocol is designed for guiding expensive wet-lab experiments, where the "function evaluation" is a real biological assay [6].

Define the Optimization Campaign:

- Inputs (x): Define the tunable biological factors (e.g., inducer concentrations, medium components, enzyme variants). Normalize each to a defined range (e.g., [0, 1]).

- Objective (y): Define the quantitative output to maximize/minimize (e.g., product titer, growth rate, fluorescence).

- Acquisition Policy: Choose an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) and a risk-tuning parameter.

Initial Design and First Batch:

- Perform a small space-filling initial design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) of

kexperiments (e.g.,k= 5 x dimensionality) to seed the model. - Execute these experiments and measure the objective.

- Perform a small space-filling initial design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) of

Iterative Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Model Update: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) surrogate model on all data collected so far. Use a kernel (e.g., Matern) appropriate for biological responses.

- Next Point Selection: The acquisition function uses the GP's mean and variance predictions to calculate the "utility" of each unexplored point. The point maximizing utility is selected as the next experiment.

- Parallel/Batch Selection (Optional): For batch experiments, use a method like

qEIto select a batch of points that are jointly informative. - Experiment & Iterate: Run the new experiment(s), add the data to the training set, and repeat from the model update step until the budget is exhausted or convergence is achieved.

Protocol 3: Incorporating Machine Learning Predictions with UniKP

This protocol integrates ML-predicted parameters as informed priors in a model-building workflow [3].

Parameter Prediction:

- For each reaction in your model, compile the amino acid sequence of the enzyme (UniProt ID) and the SMILES string of the main substrate/product.

- Input the pairs into the UniKP framework (or EF-UniKP if pH/temperature are factors) to obtain predictions for

kcat andKm.

Model Initialization and Refinement:

- Use the predicted values as initial guesses or fixed values in your kinetic model.

- If time-course data is available, use the predictions as a starting point for further local optimization (Protocol 1, Step 3) to refine the parameters within the cellular context.

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify which reactions' parameters have the greatest impact on model outputs. Prioritize obtaining experimental data for these high-sensitivity, high-uncertainty parameters.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Key Application in Kinetic Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling Frameworks | SKiMpy, MASSpy, Tellurium | Provides integrated workflows for building, simulating, and analyzing kinetic models. | Automates model assembly, parameter sampling, and integration with omics data [2]. |

| Optimization Engines | pyPESTO, BioKernel (BO), DeePMO (Deep Learning) | Performs parameter estimation via multi-start local, Bayesian, or deep learning optimization. | Calibrates models to experimental data; efficiently guides design-build-test-learn cycles [6] [7] [1]. |

| Parameter Databases/Predictors | BRENDA, SABIO-RK, UniKP | Databases of measured kinetic parameters; ML tools for in silico prediction. | Provides prior knowledge for parameter values; generates estimates where data is missing [3]. |

| Model Repositories/Standards | BioModels, SBML | Repository of peer-reviewed models; standard model exchange format. | Enables model sharing, reproducibility, and reuse. |

| Identifiability & UQ Tools | Profile Likelihood, MCMC (in Maud/pyPESTO) | Assesses whether parameters can be uniquely estimated and quantifies their uncertainty. | Critical for evaluating model reliability and trustworthiness before making predictions [1]. |

Diagram Title: Global Optimization Strategies for Kinetic Parameters

Application Notes: Optimization Methods for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

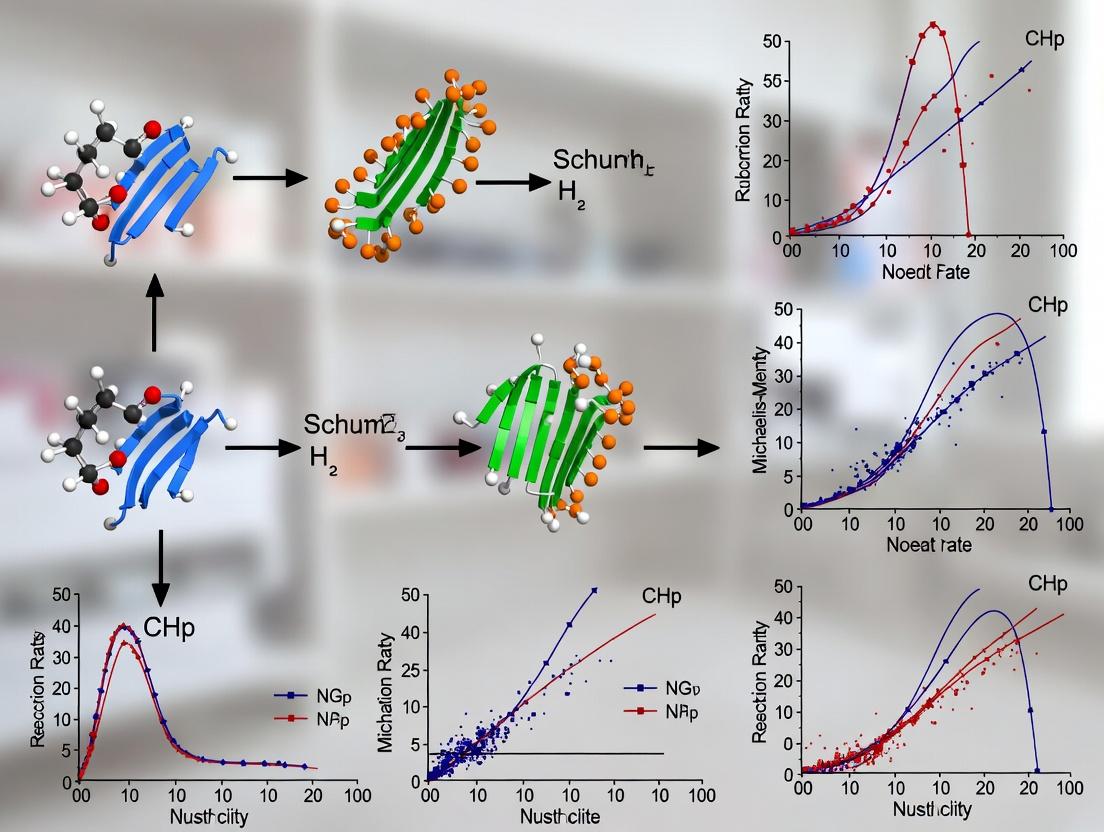

The estimation of kinetic parameters, such as Michaelis constants (Kₘ), is a fundamental bottleneck in building predictive biochemical models for drug discovery. The process involves navigating complex, high-dimensional, and often multimodal search spaces where traditional optimization methods falter [8]. The integration of advanced computational strategies is essential to accelerate research and yield biologically plausible parameters.

Table 1: Comparison of Global Optimization Methods for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Method | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Primary Challenge | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Global Optimization (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) | Direct minimization of error between model simulation and experimental data [8]. | Does not require gradient information; can escape local minima. | Computationally demanding; can yield unrealistic parameter values; suffers from non-identifiability [8]. | Initial parameter estimation for well-defined systems with abundant data. |

| Machine Learning-Aided Global Optimization (MLAGO) | Constrained optimization using ML-predicted parameters as biologically informed priors [8]. | Reduces computational cost, ensures parameter realism, and mitigates non-identifiability [8]. | Accuracy depends on the quality and scope of the ML predictor's training data. | Estimating parameters for enzymes or systems with sparse experimental measurements. |

| Batch Bayesian Optimization (BO) | Uses a probabilistic surrogate model to guide the selection of informative parallel experiments [9]. | Highly sample-efficient; optimal for expensive, noisy, high-dimensional experiments [9]. | Performance sensitive to choice of acquisition function, kernel, and noise handling [9]. | Optimizing experimental conditions (e.g., catalyst composition, process parameters) in high-throughput screening. |

| Direct Model-Based Reconstruction | Integrates the kinetic model directly into the inverse problem solver (e.g., for medical imaging) [10]. | Dramatically reduces dimensionality; enables extreme data compression (e.g., 100x undersampling) [10]. | Requires an accurate forward model; computationally complex per iteration. | Estimating tracer-kinetic parameters (e.g., Ktrans) directly from undersampled medical imaging data [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Machine Learning-Aided Global Optimization (MLAGO) for Michaelis Constant (Kₘ) Estimation

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing the MLAGO method to estimate Michaelis constants within a kinetic model, combining machine learning predictions with constrained global optimization [8].

1. Objective: To uniquely and realistically estimate unknown Kₘ values for a kinetic metabolic model.

2. Materials & Software:

- Kinetic model (SBML file or equivalent ODE system).

- Experimental dataset of metabolite concentrations over time.

- Machine learning-based Kₘ predictor (e.g., web tool from [8]).

- Global optimization software (e.g., RCGAToolbox implementing the REXstar/JGG algorithm [8]).

- Computing environment (Python, MATLAB).

3. Procedure: 1. Model and Data Preparation: Formulate the kinetic model as a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Compile experimental data (concentration time courses) for model calibration [8]. 2. Machine Learning Prediction: For each enzyme in the model requiring a Kₘ value, query the ML predictor using its EC number, substrate KEGG Compound ID, and organism ID. Record the predicted log10(Kₘ) values as the reference vector qML [8]. 3. Define the Optimization Problem: Formulate the constrained problem as defined in MLAGO [8]: * Minimize: RMSE(q, qML) (The root mean squared error between estimated and ML-predicted log-scale parameters). * Subject to: BOF(p) ≤ AE. (The badness-of-fit of the model simulation to experimental data must be less than an acceptable error threshold, AE). * Search Space: pL ≤ p ≤ pU (e.g., 10⁻⁵ to 10³ mM) [8]. 4. Execute Constrained Global Optimization: Configure the genetic algorithm (e.g., REXstar/JGG) with the above constraints. Run the optimization to find the parameter set p that minimizes deviation from ML predictions while achieving an acceptable fit to data. 5. Validation: Simulate the calibrated model and visually/statistically compare outputs to the held-out experimental data. Assess the biological plausibility of the final Kₘ estimates.

4. Diagram: MLAGO Workflow for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

Diagram 1 Title: MLAGO workflow integrating ML prediction with constrained optimization.

Protocol 2: Batch Bayesian Optimization for High-Dimensional Experimental Design

This protocol describes using Batch Bayesian Optimization to efficiently navigate a high-dimensional parameter space in an experimental setting, such as optimizing catalyst synthesis conditions [9].

1. Objective: To find the global optimum of a noisy, expensive-to-evaluate function (e.g., material yield) over a 6-dimensional parameter space using parallel experiments.

2. Materials & Software:

- Automated experimental setup (e.g., liquid handler, parallel reactor).

- Bayesian Optimization software (e.g., Emukit, BoTorch).

- Computer for running the BO loop.

3. Procedure: 1. Initial Experimental Design: Select an initial batch of points (e.g., 10-20) across the parameter domain using a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling). 2. Run Initial Batch: Conduct experiments at these initial conditions and record the objective function value (e.g., yield). 3. BO Loop: For a predetermined number of iterations: a. Surrogate Modeling: Fit a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model to all data collected so far. The Matérn kernel is often a robust default choice [9]. b. Batch Acquisition: Select the next batch of experiment points using an acquisition function suitable for parallel selection: * Use Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) for a balance of exploration and exploitation [9]. * Employ a penalization or exploratory strategy (e.g., local penalty) to ensure the batch points are diverse and informative [9]. c. Run Batch Experiments: Execute the newly selected batch of experiments in parallel. d. Update Data: Append the new results to the dataset. 4. Analysis: After the loop terminates, analyze the GP posterior mean to identify the predicted optimum parameter set. Validate by running a confirmation experiment at this location.

4. Key Considerations:

- Noise: The GP's noise level should be set to reflect experimental uncertainty. High noise can severely degrade optimization for "needle-in-a-haystack" problems (e.g., Ackley function) [9].

- False Maxima: For landscapes with near-degenerate optima (e.g., Hartmann function), BO may converge to a false maximum, especially under noise [9]. Prior knowledge of the landscape is valuable.

5. Diagram: Batch Bayesian Optimization Loop for Experimental Design

Diagram 2 Title: Iterative Batch BO loop for guiding parallel experiments.

Protocol 3: Direct Estimation of Tracer-Kinetic Parameter Maps from Medical Imaging Data

This protocol details a model-based reconstruction method to estimate physiological parameters (Ktrans, vp) directly from highly undersampled DCE-MRI data, bypassing intermediate image reconstruction [10].

1. Objective: To compute accurate tracer-kinetic parameter maps directly from undersampled (k,t)-space MRI data.

2. Materials & Data:

- MRI Scanner with dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) sequence.

- Undersampled (k,t)-space data from a DCE-MRI scan.

- Pre-contrast T1 map and M0 map (e.g., from DESPOT1 sequence) [10].

- Coil sensitivity maps.

- Arterial Input Function (AIF), population-based or measured [10].

3. Procedure:

1. Forward Model Definition: Construct the full non-linear forward model f that maps parameter maps to acquired data [10]:

* Step 1 (Kinetics): Convert parameter maps (Ktrans(r), vp(r)) to contrast agent concentration CA(r,t) using the Patlak model (Eqn. 1) [10].

* Step 2 (Signal): Convert CA(r,t) to dynamic images s(r,t) using the spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) signal equation (Eqn. 2), incorporating pre-contrast T1 and M0 maps [10].

* Step 3 (Acquisition): Apply coil sensitivity maps C(r,c) and the undersampled Fourier transform Fu to simulate acquired k-space data S(k,t,c) (Eqn. 3) [10].

2. Formulate Inverse Problem: Pose the parameter estimation as a non-linear least squares optimization (Eqn. 5) [10]:

argmin || S_acquired - f(Ktrans, vp) ||²

3. Solve Optimization: Use an efficient gradient-based optimizer (e.g., quasi-Newton L-BFGS) to solve for the parameter maps that minimize the difference between modeled and acquired k-space data.

4. Validation (Retrospective): For validation, compute the root mean-squared error (rMSE) of parameter values in tumor regions of interest compared to those derived from fully-sampled data [10].

4. Diagram: Direct Model-Based Reconstruction of Kinetic Parameters

Diagram 3 Title: Forward model and inverse problem for direct kinetic parameter mapping.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Computational and Experimental Reagents for Parameter Landscape Navigation

| Item | Function in Optimization | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Benchmark Functions (Ackley, Hartmann) | Provide controlled, high-dimensional test landscapes with known global optima to evaluate and tune optimization algorithms before costly experiments [9]. | The 6D Ackley function tests "needle-in-a-haystack" search; the 6D Hartmann function tests robustness against near-degenerate false maxima [9]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model | Acts as a probabilistic approximation of the expensive black-box function, providing predictions and uncertainty estimates to guide sample selection [9]. | Kernel choice (e.g., Matérn) and hyperparameters (length scales) encode assumptions about function smoothness. Performance is sensitive to noise modeling [9]. |

| Batch Acquisition Function (e.g., q-UCB) | Evaluates the utility of sampling a batch of points simultaneously, balancing exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of known promising areas [9]. | Critical for sample efficiency in high-throughput experimental settings. Requires strategies (e.g., penalization) to ensure batch diversity [9]. |

| Machine Learning-Based Parameter Predictor | Provides biologically informed prior estimates for kinetic parameters (e.g., Kₘ), constraining the optimization search space to realistic values [8]. | Predictors using minimal identifiers (EC, KEGG ID) enhance usability. Predictions serve as references in the MLAGO framework to prevent overfitting and non-identifiable solutions [8]. |

| Patlak Model & SPGR Signal Equation | Constitutes the forward physiological model that maps tracer-kinetic parameters to observable MRI signals, enabling direct model-based reconstruction [10]. | The accuracy of this combined model is paramount for the validity of direct estimation. Requires separate measurement of baseline T1 and equilibrium magnetization M0 [10]. |

| Global Optimization Algorithm (e.g., REXstar/JGG) | Searches a broad parameter space for a global minimum/maximum without being trapped in local optima, essential for fitting non-convex models [8]. | Used in both conventional and MLAGO frameworks. In MLAGO, it minimizes deviation from ML priors subject to a data-fitting error constraint [8]. |

The estimation of kinetic parameters is a cornerstone of building predictive models in biochemistry, pharmacometrics, and systems biology. The process involves fitting a mathematical model, defined by parameters such as Michaelis constants (Km), turnover numbers (kcat), and inhibition constants (Ki), to experimental data. This fitting is framed as an optimization problem, where an algorithm searches parameter space to minimize a cost function quantifying the mismatch between model simulations and observed data [11] [8].

A fundamental challenge in this landscape is the presence of multiple optima. Traditional local optimization methods can converge to a local optimum—a parameter set that provides the best fit in a confined region of parameter space but may be far from the global optimum, which offers the best possible fit across the entire plausible parameter domain [11]. While global optimization methods like scatter search metaheuristics, particle swarm optimization, and genetic algorithms are designed to overcome this and locate the global optimum, they introduce a critical secondary risk: the identified "best-fit" parameter set may be physiologically implausible [12] [8].

Physiologically implausible parameters are values that, while mathematically optimal for fitting a specific dataset, contradict established biological knowledge. Examples include enzyme Km values that are orders of magnitude outside the range of known cellular substrate concentrations, or drug clearance rates incompatible with human physiology. These implausible sets arise because objective functions based solely on goodness-of-fit lack biological constraints, allowing algorithms to exploit model sloppiness and compensate for errors in one parameter with unrealistic values in another [8].

This document, framed within a thesis on global optimization for kinetic parameters, details the nature of this risk and provides application notes and experimental protocols for modern strategies that integrate global search robustness with physiological plausibility enforcement. These strategies include hybrid machine learning-aided optimization, Bayesian frameworks, and rigorous mechanistic validation [12] [13] [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Approaches for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Approach | Key Principle | Advantage | Primary Risk | Typical Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Optimization | Iterative gradient-based search from a single starting point. | Computationally fast, efficient for convex problems. | High probability of entrapment in a local optimum, missing the global solution. | Preliminary fitting, refinement near a known good parameter set. |

| Naive Global Optimization | Stochastic or heuristic search across the entire parameter space (e.g., Genetic Algorithms, Particle Swarm). | High probability of locating the global optimum of the cost function. | May converge to a physiologically implausible parameter set that fits the data. | Problems with rugged parameter landscapes, no prior knowledge. |

| Constrained/Hybrid Global Optimization | Global search guided by physiological bounds or machine learning priors (e.g., MLAGO). | Balances fit quality with biological realism; reduces non-identifiability. | Requires reliable prior knowledge or reference data; complexity in implementation. | Building predictive models for drug action or metabolic engineering. |

| Bayesian Global Optimization | Treats parameters as probability distributions; seeks to explore parameter uncertainty (e.g., ABC). | Quantifies uncertainty, identifies correlation between parameters. | Computationally intensive; requires careful design of priors and sampling. | Problems with sparse/noisy data, uncertainty quantification is critical. |

Methodologies for Avoiding Implausible Optima

Machine Learning-Aided Global Optimization (MLAGO)

The MLAGO framework directly addresses the trade-off between model fit and physiological plausibility [8]. It leverages machine learning (ML) models trained on databases of known kinetic parameters to generate biologically informed reference values. These predictions are not used as fixed constants but as guides to constrain the global optimization search towards realistic regions of parameter space.

Core Workflow:

- Prediction: For unknown parameters in the target model, an ML predictor (e.g., for Km based on EC number, substrate, and organism) generates reference values (pᵀᴹᴸ).

- Constrained Optimization: The parameter estimation is reformulated as a constrained global optimization problem. The algorithm minimizes the distance between the estimated and ML-predicted parameters (e.g., Root Mean Square Error on a log scale) while enforcing a constraint that the badness-of-fit (BOF) to the experimental data remains below an acceptable error (AE) threshold [8].

- Solution: This yields a parameter set that provides a good enough fit to the data while remaining close to biologically plausible reference values, effectively navigating away from implausible global optima.

MLAGO Workflow for Plausible Parameter Estimation

Pathway Parameter Advising for Topological Plausibility

In network and pathway reconstruction, implausibility relates not to individual parameter values but to the topological structure of the inferred network. The Pathway Parameter Advising algorithm avoids generating unrealistic, oversized, or disconnected networks by comparing the topology of a candidate reconstructed pathway to a database of curated, biologically plausible pathways [14].

Core Workflow:

- Graphlet Decomposition: Both the candidate pathway and reference pathways are decomposed into small, connected non-isomorphic induced subgraphs called graphlets.

- Topological Scoring: A distance metric is computed between the graphlet frequency vectors of the candidate and reference pathways.

- Parameter Ranking: For a given pathway reconstruction algorithm run with multiple parameter settings, the settings that produce networks with the smallest topological distance to known biological pathways are ranked highest. This method-selects parameters that yield networks with "biologically familiar" connectivity patterns [14].

Mechanistic Validation of Global Parameters

For mechanism-based enzyme inactivators (MBEIs) in drug discovery, validating that globally optimized kinetic parameters (kᵢₙₐcₜ, Kᵢ) reflect the true chemical mechanism is essential. A multi-modal validation protocol combining global progress curve analysis with mechanistic studies confirms plausibility [13].

Core Workflow:

- Global Kinetic Analysis: Progress curve analysis under varied inhibitor/substrate concentrations yields best-fit kᵢₙₐcₜ and Kᵢ.

- Mechanistic Interrogation: Independent experiments, such as Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) studies, are performed. A significant KIE on kᵢₙₐcₜ indicates that bond cleavage to the deuterated atom is rate-limiting.

- Computational Chemistry Validation: Quantum mechanical (QM) cluster models of the enzyme active site are used to calculate the energy barrier for the proposed rate-limiting step. The correlation between computed barriers and experimental kᵢₙₐcₜ values across related inhibitors validates that the parameter has a true mechanistic meaning, not just a mathematical optimum [13].

Mechanistic Validation Workflow for Enzyme Inactivation Parameters

Integrated Bayesian Multi-Objective Optimization

A sophisticated framework for environmental engineering kinetics combines single-objective, multi-objective, and Bayesian optimization [12].

- Single-Objective Global Search: Identifies the global optimum and bounds of the parameter space.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Explicitly treats the fit to different observed variables (e.g., biomass, substrate) as separate, competing objectives. This identifies the Pareto frontier of compromise solutions, revealing trade-offs.

- Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC): Targets the compromise solution space identified in step 2, using Bayesian sampling to fully explore parameter uncertainty and correlation. This ensemble of plausible parameter sets provides a more robust and reliable prediction than a single optimal point, inherently mitigating the risk of overfitting to one implausible set [12].

Table 2: Assessment of Parameter Plausibility Across Methods

| Validation Method | What is Assessed | Criteria for Plausibility | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Knowledge Bounds | Individual parameter magnitude. | Parameter lies within a pre-defined physiological range (e.g., Km between 1 µM and 10 mM). | Initial screening of any optimization result. |

| Machine Learning Prediction Proximity [8] | Biological realism of individual parameters. | Estimated value is within an order of magnitude of a database-informed ML prediction. | Constraining Km, kcat estimation in metabolic models. |

| Mechanistic Consistency [13] | Chemical meaning of kinetic constants. | Experimental kᵢₙₐcₜ correlates with KIE and QM-calculated barrier for the same step. | Validation of drug candidate mechanism. |

| Topological Analysis [14] | Structure of a reconstructed network. | Graphlet distribution is similar to curated biological pathways (not too dense/sparse). | Systems biology network inference. |

| Bayesian Posterior Distribution [12] | Overall uncertainty and correlation. | Parameter distributions are tight and consistent with known biological constraints. | Probabilistic modeling in engineering. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Global Optimization Methods for Large Kinetic Models

Adapted from Villaverde et al. (2019) [11].

Objective: To systematically compare the performance of local, global, and hybrid optimization methods in estimating parameters for a large-scale kinetic model, assessing both their robustness in finding good fits and their propensity to converge to implausible solutions.

Materials: A defined kinetic model (ODEs), experimental dataset, high-performance computing cluster, software: AMIGO2 (or similar), MEIGO toolbox, RCGAToolbox.

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation:

- Define the parameter estimation problem: cost function (e.g., weighted sum of squared errors), parameter bounds (use wide, physiologically conservative bounds like 10⁻⁵ to 10³ mM for Km [8]).

- Algorithm Selection:

- Local Multi-Start: Run a gradient-based local optimizer (e.g., interior-point, Levenberg-Marquardt) from 100-1000 random starting points within the bounds.

- Stochastic Metaheuristics: Configure standalone global algorithms: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution (DE).

- Hybrid Methods: Configure hybrid algorithms: e.g., a global scatter search metaheuristic combined with a gradient-based local solver, using adjoint sensitivity analysis for efficiency [11].

- Performance Metrics:

- Success Rate: Proportion of runs converging to a cost function value within a threshold of the best-found optimum.

- Computational Cost: CPU time to convergence.

- Parameter Plausibility: For each best-fit set, calculate the RMSE (log scale) between estimated parameters and known literature or ML-predicted reference values [8].

- Execution & Analysis:

- Run each method 50-100 times to account for stochasticity.

- Record the best, median, and worst performance for each metric.

- Identify if the mathematical global optimum corresponds to a physiologically implausible parameter set.

Protocol 2: Implementing MLAGO for Michaelis Constant (Km) Estimation

Adapted from Maeda (2022) [8].

Objective: To estimate unknown Km values for a kinetic model by integrating machine learning predictions as soft constraints in a global optimization routine.

Materials: Target kinetic model, experimental time-course data, list of enzyme EC numbers and KEGG Compound IDs for substrates, access to the web-based Km predictor or a pre-trained ML model [8].

Procedure:

- Machine Learning Prediction:

- For each unknown Km, input the enzyme's EC number, substrate's KEGG Compound ID, and organism into the ML predictor.

- Record the predicted log10(Kmᴹᴸ) and its uncertainty if available.

- Define the Constrained Optimization Problem:

- Decision Variables: log10(Kmᵢ) for all unknown Km.

- Objective Function: Minimize RMSE( q, qᴹᴸ ), where q is the vector of estimated log10(Km) and qᴹᴸ is the vector of ML-predicted values.

- Constraint: BOF( p ) ≤ AE, where p is the actual (non-log) parameter vector, BOF is defined in Eq. (2) [8], and AE is an acceptable error threshold (e.g., 10-20% normalized error).

- Bounds: Set wide search bounds (e.g., -5 to +3 on log10 scale).

- Optimization Execution:

- Use a constrained global optimizer (e.g., a modified Real-Coded Genetic Algorithm like REXstar/JGG).

- The optimizer will search for parameter sets that satisfy the data-fit constraint while staying as close as possible to the ML-predicted values.

- Validation:

- Simulate the model with the final MLAGO-estimated parameters.

- Compare simulation quality and parameter plausibility against a conventional unconstrained global optimization run.

Protocol 3: Mechanistic Validation of Inactivation Parameters (kᵢₙₐcₜ,Kᵢ)

Adapted from Weerawarna et al. (2021) [13].

Objective: To validate that the globally fitted inactivation parameters for a mechanism-based enzyme inactivator correspond to the true chemical mechanism.

Materials: Purified target enzyme (e.g., GABA-AT), substrate, mechanism-based inactivator (e.g., OV329, CPP-115), deuterated analog of the inactivator, stopped-flow or standard spectrophotometer, computational chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian).

Procedure: Part A: Global Kinetic Analysis

- Acquire progress curves for product formation at multiple initial concentrations of inhibitor ([I]) and substrate ([S]).

- Fit all curves globally to the integrated equation for mechanism-based inhibition using nonlinear regression software to extract best-fit estimates for kᵢₙₐcₜ (inactivation rate constant) and Kᵢ (binding constant).

Part B: Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) Study

- Synthesize or obtain a deuterated version of the inactivator, where deuterium is incorporated at the proposed site of bond cleavage during the rate-limiting step.

- Measure the inactivation kinetics (determine kᵢₙₐcₜ) with both the protiated (H) and deuterated (D) inactivator under identical conditions.

- Calculate the experimental KIE as kᵢₙₐcₜ(ᴴ) / kᵢₙₐcₜ(ᴰ). A primary KIE (>2) confirms that cleavage of that C-H/D bond is rate-limiting for the inactivation step described by kᵢₙₐcₜ.

Part C: Quantum Mechanical (QM) Validation

- Build a QM cluster model of the enzyme active site, including key amino acid residues, cofactor, and the bound inactivator.

- Calculate the transition state energy barrier (ΔG‡) for the proposed rate-limiting step (e.g., deprotonation) for a series of related inactivators.

- Plot experimental log(kᵢₙₐcₜ) against calculated ΔG‡. A strong linear correlation (Bronsted plot) provides theoretical validation that the fitted kᵢₙₐcₜ parameter accurately reflects the chemistry of the rate-limiting step [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Wide-Range Kinetic Assay Buffer | To measure enzyme activity and generate progress curves under varied conditions for global fitting. | Must maintain enzyme stability and linear initial rates. Often includes cofactors (e.g., PLP for transaminases). |

| Deuterated Inactivator/Substrate | To conduct Kinetic Isotope Effect (KIE) studies for mechanistic validation of rate constants. | Requires synthetic chemistry. Deuterium must be placed at the specific bond involved in the proposed rate-limiting step. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | To rapidly mix reagents and monitor very fast kinetic events (e.g., initial binding, rapid burst phases). | Essential for pre-steady-state kinetics and measuring very high kᵢₙₐcₜ values. |

| MEIGO / AMIGO2 Toolboxes | Software suites for robust global optimization and parameter estimation in systems biology. | Provide implementations of scatter search, eSS, and other hybrid algorithms benchmarked for kinetic models [11]. |

| RCGAToolbox | Implements advanced Real-Coded Genetic Algorithms (e.g., REXstar/JGG) for parameter estimation. | Demonstrated effectiveness in constrained optimization problems like MLAGO [8]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | To perform QM cluster calculations for transition state modeling and energy barrier estimation. | Gaussian, ORCA. Used to validate the chemical meaningfulness of fitted parameters [13]. |

| Pathway/Network Curated Databases | Source of topologically plausible reference pathways (e.g., Reactome, NetPath). | Used as the gold standard for the Pathway Parameter Advising algorithm's graphlet comparison [14]. |

| Kinetic Parameter Databases & ML Predictors | Provide prior knowledge and reference values for parameters (e.g., BRENDA, SABIO-RK, MLAGO web tool). | Critical for setting bounds and formulating plausibility constraints in optimization [8]. |

The quantitative characterization of molecular interactions—between enzymes and substrates, drugs and receptors, and within cellular signaling networks—forms the foundational language of biochemistry and pharmacology. Parameters such as the Michaelis constant (Km), maximal velocity (Vmax), and the dissociation constant (KD) are not mere numbers; they are critical predictors of biological function, drug efficacy, and therapeutic safety [15]. However, the accurate determination of these parameters is fraught with challenges, including complex binding behaviors, time-dependent inhibition, and the profound influence of experimental conditions [15] [16].

This document frames these practical challenges within the broader context of a thesis on global optimization methods for kinetic parameter research. Traditional, isolated fitting of data to simple models is often insufficient. Global optimization seeks to find the set of kinetic parameters that best explain all available experimental data across multiple conditions (e.g., varying substrate, inhibitor, and time) simultaneously [16] [17]. This approach increases robustness, reveals mechanisms (e.g., distinguishing 1:1 binding from cooperative interactions), and enables the fine-tuning of molecular properties, such as the residence time of a reversible covalent drug [15] [16]. The following Application Notes and Protocols provide the experimental and computational frameworks necessary to generate high-quality data for such integrative, optimized analysis in drug discovery and systems biology.

Application Note: Determining Enzyme Kinetic Parameters (Km, Vmax)

Objective: To accurately determine the Michaelis-Menten parameters Km (substrate affinity) and Vmax (maximum catalytic rate) for an enzyme, providing essential data for inhibitor screening and mechanistic studies.

Background: Km represents the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax [18]. These parameters are fundamental for understanding enzyme function and are primary targets for global optimization in characterizing enzyme-inhibitor interactions.

Protocol: Microplate-Based Kinetic Assay for Esterases

This protocol adapts a standardized method for hydrolytic enzymes using a p-nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) assay on a microplate reader [18].

I. Reagent Preparation

- Assay Buffer: 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4.

- Substrate Stock: 10 mM p-nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) in DMSO. Prepare fresh daily.

- Enzyme Solution: Dilute the target esterase (e.g., enzyme preparations E1, E2) in assay buffer to an appropriate working concentration [18].

- Product Standard: 10 mM p-nitrophenol (pNP) in assay buffer for generating a standard curve.

II. Experimental Procedure

- Plate Setup: In a clear 96-well plate, pipette 190 µL of assay buffer and 10 µL of enzyme solution per well. Include control wells: blanks (buffer + substrate, no enzyme) and negative controls (buffer + enzyme, no substrate) [18].

- Substrate Injection & Measurement: Using the plate reader's onboard injectors, add 40 µL of pNPA substrate at varying concentrations (e.g., 0.01-1.0 mM final concentration) to initiate the reaction. Immediately begin kinetic measurement of absorbance at 410 nm every second for 90 seconds at 37°C [18].

- Standard Curve: Prepare a dilution series of pNP (0-0.1 µmol per well in 200 µL buffer, plus 40 µL DMSO) and measure absorbance at 410 nm to determine the extinction coefficient under assay conditions [18].

III. Data Analysis & Global Optimization Context

- Initial Rate Calculation: For each substrate concentration, determine the initial linear rate of absorbance increase (ΔOD/min). Convert to reaction velocity (v, µmol/min) using the extinction coefficient from the standard curve [18].

- Parameter Estimation: Plot velocity (v) vs. substrate concentration ([S]). Fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation: v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S]). Modern analysis software (e.g., BMG LABTECH MARS) can perform this fit directly and provide linearized transformations (Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee, Hanes) for validation [18].

- Optimization Insight: A single Michaelis-Menten curve provides preliminary Km and Vmax. In the context of global optimization, this assay becomes a component of a larger dataset. For instance, repeating this protocol at multiple inhibitor concentrations generates a 3D dataset (v, [S], [I]) that must be fit globally to a unified competitive, non-competitive, or mixed inhibition model to derive accurate inhibition constants (Ki), a more robust approach than isolated IC50 determinations [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Km and Vmax for Two Model Esterases (E1, E2) from Different Fitting Methods [18]

| Plot/Fitting Method | Enzyme E1 | Enzyme E2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (µmol) | Vmax (µmol/min) | Km (µmol) | Vmax (µmol/min) | |

| Michaelis-Menten | 0.056 | 44.8 | 0.12 | 16.3 |

| Lineweaver-Burk | 0.073 | 49.2 | 0.08 | 12.5 |

| Eadie-Hofstee | 0.063 | 46.4 | 0.07 | 13.2 |

| Hanes | 0.056 | 44.4 | 0.11 | 15.5 |

Application Note: Characterizing Drug-Receptor Binding Affinity (KD)

Objective: To quantify the binding affinity (KD) between a drug candidate (ligand) and its target receptor, a critical step in lead optimization.

Background: The dissociation constant KD is the ligand concentration at which half the receptor sites are occupied at equilibrium. A lower KD indicates higher affinity [15]. Accurate KD determination requires careful assay design to avoid common pitfalls such as ignoring buffer effects, assuming incorrect binding models, or relying solely on surface-immobilized methods [15].

Protocol: Scintillation Proximity Assay (SPA) for Receptor Binding

This protocol is adapted from HTS guidelines for G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and other membrane targets using a radioligand [19].

I. Reagent Preparation

- Assay Buffer: Typically 20-50 mM HEPES or Tris, pH 7.4, with 5-10 mM MgCl2 and 100-150 mM NaCl. Protease inhibitors are often added [19].

- Receptor Source: Cell membranes expressing the target receptor, diluted in assay buffer.

- Radioligand: A high-affinity, radioisotope-labeled ligand (e.g., ³H or ¹²⁵I) for the target.

- Test Compounds: Unlabeled drug candidates in DMSO.

- SPA Beads: Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA)-coated PVT or YSi beads that bind to cell membranes [19].

- Positive Control: A high concentration of an unlabeled reference compound to define non-specific binding (NSB).

II. Experimental Procedure (Competition Format)

- Plate Setup: In a 96- or 384-well plate, add test compound (in DMSO, final concentration typically ≤1%), a fixed concentration of radioligand (at or below its KD), and receptor membranes [19].

- Initiation: Initiate the binding reaction by adding SPA beads. The order of addition (time-zero or delayed addition of beads) should be optimized to minimize background [19].

- Incubation: Incubate the plate at room temperature with gentle shaking for 60-120 minutes to reach equilibrium.

- Detection: Allow beads to settle, and count the plate in a microplate scintillation counter without a separation step [19].

III. Data Analysis & Global Optimization Context

- Dose-Response Curve: For each test compound, plot the measured counts (specific binding) against the logarithm of compound concentration.

- IC50 Determination: Fit the data to a four-parameter logistic (4PL) model to obtain the IC50 (concentration inhibiting 50% of specific radioligand binding).

- KD Calculation: Convert IC50 to Ki (and thus approximate KD) using the Cheng-Prusoff equation: Ki = IC50 / (1 + [L]/KD_L), where [L] is the radioligand concentration and KD_L is its known KD [19].

- Optimization Insight: The SPA protocol provides a single-point equilibrium measurement. For global optimization, especially with time-dependent inhibitors, kinetic SPA data (binding progress over time) at multiple compound concentrations must be collected. This multidimensional dataset can be fit globally to a kinetic binding model (e.g., a two-step reversible covalent model [16]) to simultaneously extract on-rates (kon), off-rates (koff), and the ultimate KD, providing a much richer profile for compound ranking and mechanism elucidation.

Diagram: Receptor Binding Assay Workflow & Pitfalls

Application Note: Advanced Kinetic Analysis of Reversible Covalent Inhibitors

Objective: To fully characterize the multi-step inhibition kinetics of reversible covalent drugs, moving beyond IC50 to determine the initial non-covalent Ki, the covalent forward (k₅) and reverse (k₆) rate constants, and the overall inhibition constant Kᵢ [16].

Background: Reversible covalent inhibitors (e.g., saxagliptin) form a transient covalent bond with their target, leading to prolonged residence time. Their action is time-dependent, meaning IC50 values shift with pre-incubation or assay duration [16]. Simple IC50 measurements fail to capture this rich kinetic profile, necessitating specialized global fitting methods.

Protocol: Time-Dependent IC50 Analysis using EPIC-CoRe Method

This protocol is based on the 2025 EPIC-CoRe (Evaluation of Pre-Incubation-Corrected Constants for Reversible inhibitors) method for analyzing pre-incubation time-dependent IC50 data [16].

I. Experimental Design

- Enzyme Activity Assay: Establish a standard enzyme activity assay (e.g., fluorescence- or absorbance-based).

- Pre-Incubation Matrix: For each test compound, set up a series of reactions where enzyme and inhibitor are pre-incubated together for varying times (t_pre = 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min) before adding substrate to initiate the reaction.

- Dose-Response at Each Time Point: For each pre-incubation time, run a full inhibitor dose-response curve (e.g., 8-12 concentrations) to determine an IC50(t_pre).

II. Data Fitting with EPIC-CoRe

- Global Nonlinear Regression: Input the matrix of inhibition data (activity vs. [Inhibitor] at each t_pre) into a global fitting software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, using defined equations; custom code in R/Python).

- Model Specification: Fit all data globally to the kinetic model for reversible covalent inhibition defined by the differential equations governing the two-step process (non-covalent binding followed by reversible covalent modification) [16].

- Parameter Output: The global fit directly estimates the fundamental parameters: Ki (initial non-covalent affinity), k₅ (covalent bond formation rate), k₆ (covalent bond breakage rate). The overall inhibitory affinity is calculated as Kᵢ = Ki / (1 + k₅/k₆) [16].

III. Global Optimization Context This protocol is a direct application of global optimization. Instead of fitting each dose-response curve independently to get a series of unrelated IC50 values, the EPIC-CoRe method uses a single, shared kinetic model to explain the entire 3D dataset (activity, [I], t_pre). This ensures parameter consistency, maximizes information use, and reveals the true mechanistic constants essential for fine-tuning drug residence time and selectivity [16].

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Signaling Pathway Modeling & Kinetic Optimization

| Tool Name | Primary Purpose | Key Feature for Optimization | Reference/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaBoSS (UPMaBoSS/PhysiBoSS) | Stochastic Boolean modeling of signaling networks & cell population dynamics. | Simulates emergent behavior from simple rules; allows parameter space exploration (kinetic logic). | [20] |

| GOLD + MOPAC (PM6-ORG) | Computational prediction of protein-ligand binding poses and relative binding energies. | Provides a calculated ΔH_binding as a proxy for ranking IC50/Ki; used for in silico screening. | [17] |

| Global Fitting Software(e.g., Prism, KinTek Explorer) | Simultaneous fitting of complex kinetic models to multi-condition datasets. | Core engine for deriving shared kinetic parameters from global experimental data. | [16] [18] |

Application Note: Modeling Signaling Pathways for Pharmacological Intervention

Objective: To construct and interrogate computational models of stem cell signaling pathways (e.g., Wnt, TGF-β, Notch) to predict outcomes of pharmacological modulation.

Background: Stem cell fate is regulated by interconnected signaling pathways [21]. Pharmacological agents can modulate these pathways to enhance therapy (e.g., direct differentiation, improve survival) [21]. Boolean modeling with tools like MaBoSS provides a flexible framework to simulate network behavior, predict drug effects, and identify optimal intervention points [20].

Protocol: Boolean Network Modeling with MaBoSS

This protocol outlines steps to create and simulate a simplified signaling network model influencing a cell fate decision (e.g., self-renewal vs. differentiation).

I. Network Definition

- Node Identification: Define key proteins/genes from pathways of interest (e.g., for stem cells: Wnt, Notch, TGF-β nodes) [21]. Assign a state of 0 (OFF/inactive) or 1 (ON/active) to each.

- Interaction Rules: Define logical rules for each node. For example:

Node_C = (Node_A AND NOT Node_B) OR Node_D. These rules are derived from literature on pathway crosstalk [21] [20].

II. Model Simulation & Pharmacological Perturbation

- Parameter Assignment: Assign probabilities to initial states and kinetic parameters (transition rates) for stochastic simulation.

- Baseline Simulation: Run MaBoSS to simulate the stochastic time evolution of the network. Outputs show the probability of each node (or cell fate) being ON over time [20].

- Intervention Simulation: Model drug action by fixing the state of a target node (e.g., set a receptor to 0 to mimic an antagonist) or altering its logical rule. Re-run simulations to predict changes in the steady-state probability of desired outcomes (e.g., increased differentiation fate).

III. Integration with Global Optimization Signaling models are parameterized with kinetic or logical constants. Global optimization can be applied to constrain these model parameters using experimental data. For instance, time-course data from flow cytometry measuring phospho-proteins (from pathways in the model) under different drug doses can be used in a reverse-engineering loop to find the set of model parameters (e.g., reaction weights, rates) that best fit all experimental conditions simultaneously. This creates a predictively optimized model for in silico drug screening [21] [20].

Diagram: Stem Cell Signaling Pathway Crosstalk & Pharmacological Modulation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Kinetic & Binding Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in Experiment | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Substrate | p-Nitrophenyl acetate (pNPA) [18] | Chromogenic substrate for hydrolases; releases yellow p-nitrophenol upon cleavage. | Solubility (requires DMSO stock); rate of auto-hydrolysis in blanks. |

| Radioligand | ¹²⁵I-labeled peptide agonist [19] | High-affinity, labeled tracer to quantify receptor occupancy in binding assays. | Specific activity; metabolic stability; matching the pharmacology of the target. |

| SPA Beads | Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA)-coated PVT beads [19] | Binds to membrane preparations, capturing receptor-ligand complexes for proximity scintillation. | Must minimize non-specific binding of radioligand to beads; type (PVT vs. YSi) affects signal [19]. |

| Kinase/Pathway Inhibitor | SB431542 (TGF-βR inhibitor) [21] | Selective small molecule to pharmacologically perturb a specific signaling node in cellular or modeling studies. | Selectivity profile; solubility and working concentration in cell media. |

| Buffers & Additives | HEPES buffer with Mg²⁺/Ca²⁺ [19] | Maintains pH and ionic conditions critical for preserving protein function and binding affinity. | KD is buffer-dependent [15]; cations can be essential for receptor activation [19]. |

| Modeling Software | MaBoSS suite [20] | Translates a network of logical rules into stochastic simulations of signaling and cell fate. | Requires precise definition of node interaction logic based on literature evidence. |

The individual protocols detailed here—for enzyme kinetics, binding affinity, advanced inhibitor kinetics, and signaling modeling—are not isolated tasks. They are complementary engines for data generation within a global optimization research cycle. The overarching thesis posits that the most accurate and biologically insightful kinetic parameters are derived by integrating data across these disparate but related experimental modalities.

For example, a comprehensive profile of a reversible covalent drug candidate would involve: 1) Determining its cellular IC50 shift over time (Protocol 4.1), 2) Measuring its direct target KD and kinetics in a purified system (Protocol 3.1), 3) Observing its effect on downstream signaling phospho-proteins via flow cytometry, and 4) Constraining a MaBoSS model of the target pathway (Protocol 5.1) with this data. A global optimization algorithm would then iteratively adjust the fundamental kinetic constants (Ki, k₅, k₆, etc.) in a unified model until it predicts all the observed experimental results (cellular activity, binding data, signaling outputs) simultaneously. This rigorous, systems-level approach moves beyond descriptive IC50s and single-condition KDs, enabling the true predictive design of therapeutics with optimized kinetic profiles for efficacy and safety.

The concept of a Potential Energy Surface (PES), a cornerstone in theoretical chemistry and physics, describes the energy of a system (traditionally a collection of atoms) as a function of its geometric parameters, such as bond lengths and angles [22] [23]. This "energy landscape" analogy, with its hills, valleys, and passes, provides an intuitive framework for understanding molecular stability, reaction pathways, and transition states [22].

In the context of a broader thesis on global optimization methods for kinetic parameters research, this PES analogy is powerfully extended to high-dimensional parameter spaces. Here, the "coordinates" are no longer atomic positions but the kinetic parameters (e.g., rate constants, activation energies, Michaelis constants) of a complex chemical or biological system [7] [2]. The "energy" or "height" on this abstract landscape corresponds to a cost or objective function, typically quantifying the discrepancy between model predictions and experimental data (e.g., ignition delay times, metabolite concentrations, laminar flame speeds) [7] [2].

Finding the global minimum of this objective function—the parameter set that best explains the observed kinetics—is the central challenge. This task is analogous to locating the lowest valley on a vast, rugged, and often poorly mapped terrain. The landscape may be riddled with local minima (parameter sets that fit some data but are not optimal) and high barriers (representing correlations or constraints between parameters), making global optimization a non-trivial, NP-hard problem in many cases [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this analogy and the associated computational tools is critical for building predictive models of metabolic pathways, drug metabolism, combustion chemistry, and catalytic processes [25] [2].

Key Concepts of the PES Analogy for Parameter Space

- Mathematical Analogy: In a classical PES, energy (E) is a function of nuclear coordinates (\mathbf{r}): (E = V(\mathbf{r})) [22]. In parameter optimization, a cost function (L) (e.g., sum of squared errors) is a function of model parameters (\mathbf{p}): (L = F(\mathbf{p})). The structure of (F(\mathbf{p})) defines the parameter energy landscape [7].

- Topographic Features:

- Local Minima: Stable parameter sets where any small change increases the cost function. These represent locally good, but potentially suboptimal, fits to the data.

- Global Minimum: The parameter set with the lowest possible cost, representing the best possible fit. This is the primary target of optimization [26].

- Saddle Points (Transition States): Points that are a maximum along one parameter direction but a minimum along all others. In parameter space, these can represent critical thresholds between different mechanistic interpretations [22].

- Funnels: Broad, smooth regions of the landscape that funnel into a deep minimum. A landscape with a pronounced funnel topography is generally easier to optimize than one with many isolated, steep minima [27].

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of the PES analogy as it maps from physical atomic coordinates to abstract model parameters.

Diagram Title: Mapping the PES Analogy from Atomic to Parameter Space

Computational Methods for Constructing PES in Parameter Space

Constructing or exploring the parameter energy landscape requires efficient methods to evaluate the objective function (L = F(\mathbf{p})). The choice of method balances computational cost with the required accuracy.

Table 1: Methods for Evaluating the Parameter Energy Landscape

| Method Category | Description | Typical Dimensionality (Number of Parameters) | Computational Cost | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Principles/Quantum Mechanics (QM) [25] | Directly solves electronic structure (e.g., via DFT) to compute elementary rate constants. | Low (1-10s). Scaling is prohibitive (e.g., ~N⁷ for CCSD(T)). | Extremely High | Fundamental kinetic studies of small systems or elementary steps. |

| Classical & Reactive Force Fields [25] | Uses parameterized analytical functions (e.g., harmonic bonds, Lennard-Jones) to compute energies and forces. | Moderate (10-500). Parameters have physical meaning (bond stiffness, etc.). | Low to Moderate | Sampling configurations, MD simulations of large systems (proteins, materials). Not for bond breaking/forming (except reactive FFs). |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF) [25] | Trains a model (e.g., neural network) on QM data to predict energy as a function of structure. | High (1000s). Number depends on network architecture, not system size. | Low (Inference) / High (Training) | High-dimensional PES exploration where QM is too costly but accuracy is needed. |

| Surrogate Models for Direct Parameter Optimization [7] | Trains a model (e.g., deep neural network) to map kinetic parameters directly to simulation outputs (ignition delay, flux, etc.). | High (10s to 100s). | Low (Inference) / High (Training) | Global optimization of kinetic models for combustion, metabolism, etc. |

A modern and efficient protocol for navigating high-dimensional parameter landscapes involves using iterative machine learning to build a surrogate model, as exemplified by the DeePMO framework [7].

Protocol 1: Iterative Sampling-Learning-Inference for Parameter Optimization (DeePMO Framework)

- Objective: To optimize a high-dimensional vector of kinetic parameters (\mathbf{p}) to minimize the difference between simulated outputs (\mathbf{S}(\mathbf{p})) and target data (\mathbf{T}).

- Materials: Initial parameter dataset (from literature or sampling), numerical simulator (e.g., chemical kinetics solver), deep learning framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch).

- Procedure:

- Initial Sampling: Generate an initial set of parameter vectors ({\mathbf{p}i}) using Latin Hypercube Sampling or similar space-filling design. For each (\mathbf{p}i), run the full numerical simulation to compute corresponding outputs (\mathbf{S}_i) [7].

- Hybrid DNN Training: Train a Deep Neural Network (DNN) as a surrogate model. A recommended architecture uses:

- A fully connected network branch to process non-sequential performance metrics (e.g., laminar flame speed).

- A multi-grade network branch (e.g., 1D CNN or RNN) to process sequential data (e.g., ignition delay time profile, temperature-residence time distribution) [7].

- The DNN learns the mapping (\mathbf{p} \rightarrow \mathbf{S}).

- Inference & Candidate Selection: Use the trained DNN to predict outputs for a vast number of candidate parameter sets ({\mathbf{p}j^{candidate}}) at minimal computational cost. Select candidates that minimize the predicted cost function (||\mathbf{S}{DNN} - \mathbf{T}||).

- Validation & Database Update: Run the full, accurate numerical simulation for the top candidate parameters. Add these new (parameter, simulation output) pairs to the training database.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until the cost function converges to a satisfactory minimum or a computational budget is exhausted. The DNN is retrained in each cycle with an enriched dataset [7].

The workflow for this iterative protocol is shown in the following diagram.

Diagram Title: DeePMO Iterative Sampling-Learning-Optimization Workflow

Global Optimization Protocols on the Parameter PES

Once the parameter landscape is defined (via direct simulation or a surrogate model), global optimization algorithms are used to find the global minimum. These protocols must efficiently explore the landscape while avoiding entrapment in local minima.

Table 2: Global Optimization Algorithms for Rugged Parameter Landscapes

| Algorithm | Core Mechanism | Key Control Parameters | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basin-Hopping (BH) [26] [24] | Iterates between random perturbation of coordinates, local minimization, and acceptance/rejection based on Metropolis criterion. | Step size, temperature. | Effectively changes topology to "step between minima". Highly effective for atomic clusters. | Performance sensitive to step size; may struggle with very high dimensions. |

| Genetic / Evolutionary Algorithms (GA/EA) [26] [27] | Maintains a population of candidate solutions. New candidates created via crossover (mating) and mutation of "parent" solutions. Fittest survive. | Population size, mutation rate, crossover rate. | Naturally parallelizable; good at exploring diverse regions of space. | Can require many function evaluations; convergence can be slow. |

| Simulated Annealing (SA) [26] | Random walks accept uphill moves with probability decreasing over time (cooling schedule). | Starting temperature, cooling rate. | Simple to implement; can escape local minima early. | Can be very slow to converge; sensitive to cooling schedule. |

| Parallel Tempering (Replica Exchange) [26] | Multiple simulations run at different temperatures. Periodic exchange of configurations between temperatures. | Temperature ladder, exchange frequency. | Excellent sampling of complex landscapes; efficient escape from traps. | High computational cost (multiple replicas). |

| Complementary Energy (CE) Landscapes [27] | Generates candidates by performing local optimization on a smoothed, machine-learned "complementary" landscape with fewer minima. | Descriptor for atomic environments, choice of attractors. | Can identify new funnels on the true PES; accelerates candidate generation. | Requires construction of an additional ML model. |

Protocol 2: Integrated Global Optimization Workflow for Kinetic Parameters

- Objective: To combine the strengths of surrogate modeling and global search algorithms for efficient parameter discovery.

- Materials: A pre-trained surrogate model (from Protocol 1), global optimization software (e.g., AGOX, in-house code) [27].

- Procedure:

- Landscape Preparation: Use a surrogate DNN model (as in DeePMO) to provide fast, approximate evaluations of the cost function (F(\mathbf{p})) [7].

- Algorithm Initialization: Choose a primary global search algorithm (e.g., Basin-Hopping or an Evolutionary Algorithm). Initialize with a population of randomly generated parameter vectors within physiologically/physically plausible bounds [26].

- Hybrid Candidate Generation:

- For a fraction of steps, generate new candidates using the core mechanism of the primary algorithm (e.g., mutation and crossover for GA) [26].

- For the remaining steps, use a Complementary Energy (CE) generator [27]: a. From the current best structure, define a set of attractors—desired local environments for parameters (conceptualized from known good fits). b. Construct a simple, smooth CE function that penalizes deviations from these attractors. c. Perform a local minimization on this CE landscape to produce a new candidate parameter vector, which is then evaluated on the true surrogate model.

- Selection and Iteration: Evaluate all candidate parameters using the fast surrogate model. Accept or reject them according to the rules of the primary algorithm (e.g., lower cost always accepted, higher cost with a probability). Update the population and the set of attractors for the CE generator based on newly discovered low-cost structures.

- High-Fidelity Verification: Periodically (e.g., every N generations) and for the final best candidates, run the high-fidelity numerical simulation to validate the surrogate model's predictions and prevent convergence to artifacts of the approximate model.

The interaction between these components in a hybrid optimization strategy is visualized below.

Diagram Title: Hybrid Global Optimization Strategy for Parameter Space

Application Notes: Case Studies in Kinetic Parameter Research

Case Study 1: Kinetic Model Optimization for Combustion (DeePMO)

- Context: Optimization of detailed chemical kinetic mechanisms (e.g., for n-heptane, ammonia/hydrogen blends) involving 10s to 100s of parameters [7].

- PES Analogy: The high-dimensional space of Arrhenius pre-exponential factors and activation energies forms a complex landscape. The objective function aggregates errors across multiple experiment types (ignition delay, flame speed) [7].

- Outcome: The iterative deep learning framework (DeePMO) successfully found optimized parameter sets, demonstrating the ability to navigate this challenging landscape more efficiently than traditional trial-and-error or local optimization methods [7].

Case Study 2: Genome-Scale Kinetic Modeling in Metabolism

- Context: Constructing kinetic models for metabolic networks, requiring estimation of thousands of enzyme kinetic parameters (KM, kcat, Hill coefficients) [2].

- PES Analogy: The parameter landscape is vast and underdetermined. Methods like SKiMpy and MASSpy use sampling to generate ensembles of parameter sets that are consistent with steady-state flux data and thermodynamic constraints, effectively characterizing accessible "valleys" in the landscape rather than a single minimum [2].

- Protocol Note: A key step is thermodynamic consistency validation, ensuring sampled parameters obey the second law, which acts as a constraint shaping the feasible region of the parameter landscape [2].

Case Study 3: Global Optimization of Platinum Cluster Structures

- Context: Searching for the most stable (lowest energy) atomic configurations of Pt₆-Pt₁₀ clusters [26].

- PES Analogy: A direct physical PES where coordinates are atomic positions. The study highlights the sensitivity of the landscape topography to the computational method (e.g., choice of DFT functional). The global minimum structure found using one functional (e.g., a planar Pt₆ cluster with PBE) can differ from that found with another (e.g., a 3D structure with PBE0), illustrating that the "map" itself can change [26].

- Takeaway: This underscores a critical point for parameter optimization: the landscape is defined by the objective function. Changing the data, error weighting, or physical constraints can alter the landscape, potentially relocating the global minimum.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Category | Item / Software / Method | Primary Function in PES-based Optimization | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Frameworks | DeePMO | Provides an iterative deep-learning framework for high-dimensional kinetic parameter optimization. | [7] |

| AGOX (Atomistic Global Optimization X) | A Python package for structure optimization implementing various algorithms (BH, EA, CE). | [27] | |

| SKiMpy, MASSpy, Tellurium | Frameworks for constructing, sampling, and analyzing kinetic metabolic models. | [2] | |

| Force Fields & Surrogates | Classical Force Fields (e.g., UFF, AMBER) | Provide fast energy evaluation for PES exploration of large, non-reactive systems. | [25] |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF) | Enable accurate and relatively fast exploration of PES for reactive systems. | [25] | |

| Surrogate Models (e.g., DNN, GPR) | Learn the mapping from parameters to simulation outputs, enabling fast global search. | [7] [27] | |

| Databases | Kinetic Parameter Databases | Provide prior knowledge and bounds for parameters (KM, kcat), initializing the search space. | [2] |

| Algorithms | Basin-Hopping, Genetic Algorithms | Core global optimization engines for navigating rugged landscapes. | [26] [24] |

| Complementary Energy (CE) Methods | Accelerate candidate generation by searching on smoothed alternative landscapes. | [27] |

Algorithm Toolkit: A Guide to Stochastic, Deterministic, and Hybrid Global Optimization Methods