Mastering Michaelis-Menten Kinetics with NONMEM: A Comprehensive Guide to Parameter Estimation for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on estimating Michaelis-Menten pharmacokinetic parameters using NONMEM, the industry-standard nonlinear mixed-effects modeling software [citation:7].

Mastering Michaelis-Menten Kinetics with NONMEM: A Comprehensive Guide to Parameter Estimation for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on estimating Michaelis-Menten pharmacokinetic parameters using NONMEM, the industry-standard nonlinear mixed-effects modeling software [citation:7]. It covers the full scope from foundational concepts of saturable elimination to advanced application, troubleshooting model instability [citation:1], and comparative analysis with emerging AI-based methodologies [citation:2]. The content details practical workflows for model implementation, addresses common convergence challenges, explores strategies for generating robust initial estimates [citation:3], and demonstrates application in therapeutic dose optimization [citation:4]. This guide synthesizes traditional best practices with the latest advancements in automated modeling pipelines to equip scientists with the knowledge to reliably characterize nonlinear pharmacokinetics.

Understanding Michaelis-Menten Kinetics and NONMEM's Role in Population PK/PD Analysis

Theoretical Foundations of Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

The Michaelis-Menten equation describes the rate of enzymatic reactions, where the velocity (v) of product formation depends on the substrate concentration ([S]) [1]. The fundamental form of the equation is: v = (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S]) [1] [2] [3].

The two critical parameters are:

- V_max (Maximum Reaction Velocity): The theoretical maximum rate of the reaction, achieved when all enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate [1]. In pharmacokinetics, it represents the maximum capacity of an enzyme system to metabolize a drug.

- Km (Michaelis Constant): Defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax [1] [2]. It is an inverse measure of the enzyme's affinity for the substrate; a lower K_m indicates higher affinity [4].

The model is derived from the foundational enzymatic mechanism: E + S ⇌ ES → E + P where E is the free enzyme, S is the substrate, ES is the enzyme-substrate complex, and P is the product [1] [3]. The derivation assumes steady-state conditions for the ES complex or rapid equilibrium binding [1] [3].

In pharmacokinetics (PK), this model is adapted to describe nonlinear drug elimination, commonly observed with drugs like phenytoin, voriconazole, and ethanol [5]. Here, the rate of drug metabolism (or elimination) is saturable. The PK analogue of the Michaelis-Menten equation is: -dC/dt = (Vmax × C) / (Km + C) where C is the plasma drug concentration [5] [2].

Pharmacokinetic Translation and Clinical Significance

The translation of in vitro enzyme kinetics to in vivo pharmacokinetics is central to predicting drug behavior. Key derived PK equations include [5]:

- Clearance (CL): At steady state, clearance becomes concentration-dependent: CL = Vmax / (Km + C_ss).

- Dosing Rate (DR): For drugs with nonlinear kinetics, the maintenance dose rate to achieve a target steady-state concentration (Css) is: DR = (Vmax × Css) / (Km + C_ss).

When drug concentration C is much lower than Km (C << Km), the elimination approximates first-order kinetics (linear pharmacokinetics). When C is much greater than Km (C >> Km), the elimination rate approaches the constant V_max, demonstrating zero-order kinetics [1] [5]. This transition underpins the nonlinear, dose-dependent pharmacokinetics critical for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index.

The specificity constant (kcat/Km), representing the enzyme's catalytic efficiency, is crucial for understanding in vivo drug metabolism and interactions [1]. Drugs can act as enzyme inducers (increasing Vmax) or inhibitors (decreasing Vmax or increasing apparent K_m), altering their own kinetics or that of co-administered drugs [5].

Table 1: Representative Drugs Exhibiting Michaelis-Menten Pharmacokinetics

| Drug/Therapeutic Area | Primary Metabolizing Enzyme | Clinical PK Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Phenytoin (Anticonvulsant) | CYP2C9 | Dose-dependent elimination; small dose increases can lead to large rises in concentration [5]. |

| Voriconazole (Antifungal) | CYP2C19 | Nonlinear PK; therapeutic drug monitoring required [5]. |

| Ethanol | Alcohol dehydrogenase | Zero-order elimination at high concentrations [5]. |

| Theophylline (Bronchodilator) | CYP1A2 | Concentration-dependent clearance; narrow therapeutic window [5]. |

Parameter Estimation Methods & The Role of NONMEM

Accurate estimation of Vmax and Km from experimental data is paramount. Methods range from traditional linearizations to modern nonlinear mixed-effects modeling.

- Linear Transformation Methods: Historically, plots like Lineweaver-Burk (1/v vs. 1/[S]) and Eadie-Hofstee (v vs. v/[S]) were used to graphically estimate parameters [4]. These methods are simple but can distort error structures and are statistically inferior for parameter estimation [4] [6].

- Direct Nonlinear Regression: Fitting the untransformed velocity vs. concentration data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear least squares regression is more robust and avoids the biases of linear transformations [4] [6].

In clinical pharmacology, population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) modeling with nonlinear mixed-effects models (NONMEM) is the gold standard for estimating Vmax and Km from sparse clinical data. It distinguishes between:

- Fixed Effects: The typical population values of Vmax and Km.

- Random Effects: Inter-individual variability (IIV) around these parameters and residual unexplained variability [7].

A major challenge in nonlinear modeling is obtaining good initial parameter estimates for the optimization algorithm. Poor initial estimates can lead to model convergence failures [7]. Strategies to generate initial estimates include [7]:

- Adaptive Single-Point Method: Using concentrations from specific time points (e.g., after first dose or at steady-state) with known dosing information to approximate clearance and volume.

- Graphical Methods: Visual inspection of concentration-time profiles.

- Naïve Pooled Data Analysis: Treating all data as if from a single individual for initial approximations.

- Parameter Sweeping: Testing a range of candidate values and selecting those with the best predictive performance [7].

Recent research has focused on developing automated pipelines that integrate these data-driven methods to generate robust initial estimates without user input, facilitating large-scale and automated PopPK analyses [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Parameter Estimation Methods for Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk Plot | Linear transform: Plot 1/v vs. 1/[S]. Vmax = 1/y-intercept; Km = slope/y-intercept [4]. | Simple visualization. | Prone to error propagation; gives undue weight to low-concentration data points; statistically unreliable [4]. |

| Direct Nonlinear Regression (NONMEM) | Fits [S] vs. time data directly to the differential form of the MM equation [4]. | Most accurate and precise; handles error structure correctly; suitable for sparse, population data [4]. | Requires specialized software; computationally intensive; needs good initial estimates. |

| Eadie-Hofstee Plot | Linear transform: Plot v vs. v/[S]. Vmax = y-intercept; Km = -slope [4]. | Visualizes data spread. | Less distortion than Lineweaver-Burk but still suboptimal vs. nonlinear methods [4]. |

| Automated Pipeline (e.g., R-based) | Combines single-point, graphical, and NCA methods to generate initial estimates for PopPK [7]. | Automated, robust, applicable to rich and sparse data; reduces modeler burden [7]. | Relatively new approach; may require validation for specific model structures. |

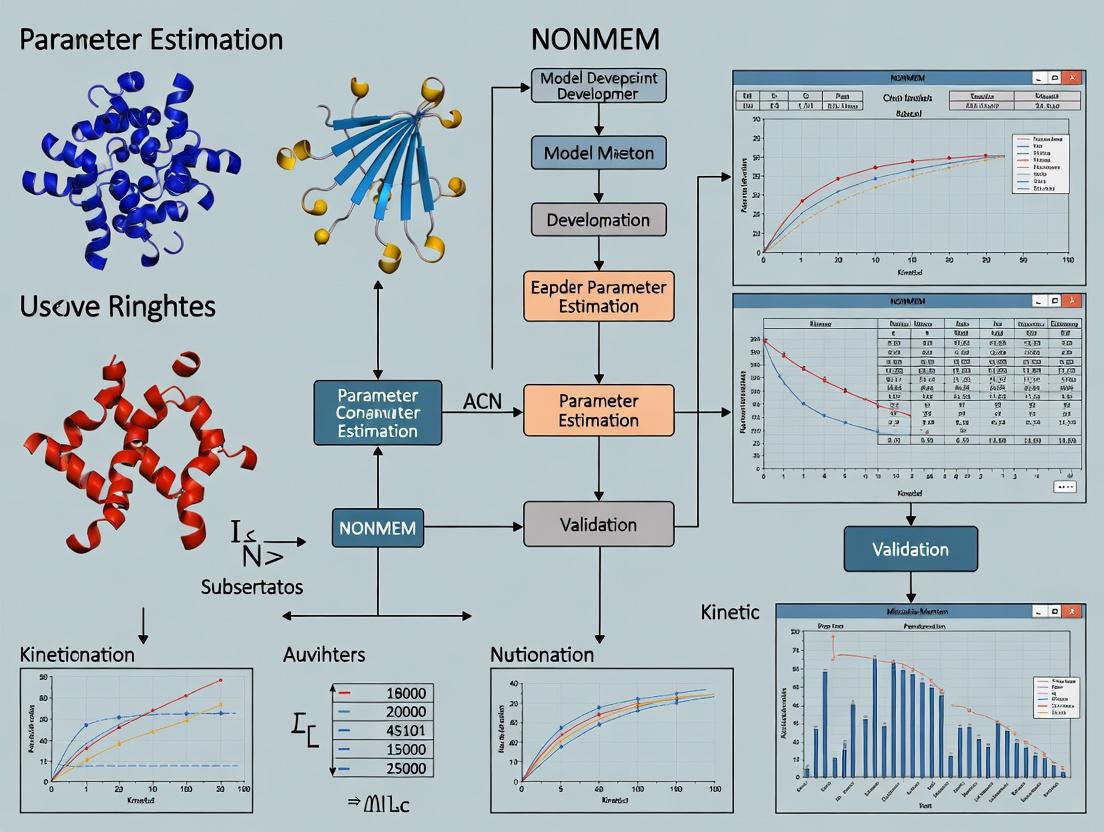

Diagram: Workflow for Michaelis-Menten Parameter Estimation in Pharmacokinetics

Advanced Protocols: NONMEM Implementation for MM Parameters

Protocol 1: Implementing a Basic Michaelis-Menten Elimination Model in NONMEM

This protocol outlines the steps to code a one-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination in a NONMEM control stream ($PROBLEM, $INPUT, etc.).

- $SUBROUTINE: Select

ADVAN6orADVAN13for general differential equation solutions, orADVAN10for analytical solutions to specific nonlinear models. DefineTOLappropriately for stiff equations. - $MODEL: Define compartments (e.g.,

DEPOT,CENTRAL). $PK:

$DES (Differential Equations for

ADVAN6):$ERROR: Define an appropriate residual error model (e.g., additive, proportional, or combined).

$ESTIMATION: Use a method like

FOCE INTERACTIONfor reliable estimation of nonlinear models with random effects [8].- $COVARIANCE: Request covariance step to obtain standard errors of parameter estimates.

Protocol 2: Generating Initial Estimates for PopPK Analysis [7]

An automated R-based pipeline can generate initial estimates for THETA:

- Data Preparation: Pool data across individuals based on time after dose (TAD), calculating median concentrations in time bins.

- Estimate Half-life: Perform linear regression on the terminal phase of the pooled log-concentration vs. time data.

- Calculate Parameters:

- For intravenous data, use an early post-first-dose point (within 0.2 half-lives) to estimate volume: Vd ≈ Dose / C₁.

- Use steady-state maximum (Css,max) and minimum (Css,min) concentrations to estimate clearance: CL ≈ Dose * ln(Css,max/Css,min) / [τ * (Css,max - Css,min)], where τ is the dosing interval.

- Approximate

V_maxandK_mfrom a range of doses and steady-state concentrations using the linearized form: 1/DR = (Km/Vmax) * (1/Css) + 1/Vmax.

- Parameter Sweeping: If analytical methods are insufficient, simulate concentration-time profiles for a grid of candidate (Vmax, Km) pairs and select the pair minimizing the relative root mean squared error (rRMSE) between observed and predicted data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents & Software for MM Parameter Estimation Research

| Item/Software | Function in MM/PK Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM | Industry-standard software for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling of PK/PD data. Used for population estimation of Vmax, Km, and their variability [4] [8]. | ICON Development Solutions. Required for implementing protocols in Sections 3 & 4. |

| R or Python | Open-source programming environments for data simulation, exploratory analysis, running automated estimation pipelines [7], and creating diagnostic plots. | Packages: nlmixr2, mrgsolve (R), PyDarwin, Pharmpy (Python). |

| ADP-Glo Kinase Assay | A luminescent method to measure kinase activity by quantifying ADP production. Used to generate initial velocity (v) vs. substrate concentration ([S]) data for in vitro enzyme kinetic studies [6]. | Example from c-Src kinase inhibition studies [6]. |

| High-Throughput Microplate Reader | Instrument to measure absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence in 96- or 384-well plates. Essential for rapidly collecting the dense [S]-v data required for robust in vitro MM parameter fitting [6]. | GloMax Discover (Promega) [6]. |

| GraphPad Prism | Commercial software for scientific graphing and basic nonlinear regression. Useful for initial exploratory fitting of in vitro MM kinetics and inhibitor IC₅₀/Kᵢ calculations [6]. | Commonly used before advanced PopPK analysis in NONMEM. |

| SigmaPlot/Solver (Excel) | Software for nonlinear curve fitting. Can be used to fit data directly to the MM equation to obtain preliminary Vmax and Km estimates [5] [6]. | An accessible tool for direct nonlinear regression [6]. |

Saturable elimination, also known as zero-order or capacity-limited elimination, is a critical pharmacokinetic (PK) phenomenon where drug clearance pathways become saturated at higher concentrations, leading to non-proportional increases in systemic exposure with dose escalation [9]. This occurs when the enzymes responsible for metabolism (e.g., cytochrome P450 isoforms) or active transport processes reach their maximum catalytic capacity (Vmax) [10]. In contrast, first-order elimination, which governs most drugs at therapeutic doses, describes a process where a constant fraction of drug is eliminated per unit time [9].

The transition from first-order to zero-order kinetics has profound implications for drug safety and efficacy. When elimination is saturated, small increases in dose can lead to disproportionately large increases in drug exposure (area under the curve, AUC), dramatically elevating the risk of toxicity [9]. This is a cornerstone of nonlinear pharmacokinetics and is classically described by the Michaelis-Menten (M-M) equation [10].

Understanding and characterizing saturable elimination is therefore essential across all drug modalities. For small molecules, saturation often involves metabolic enzymes like CYP2C9, CYP2D6, or CYP3A4. For biologics such as monoclonal antibodies, saturation can occur via target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD), where the high-affinity binding to a pharmacological target acts as a saturable elimination pathway [11]. Accurately estimating the parameters of the M-M equation (Vmax and Km) is thus a fundamental task in model-informed drug development (MIDD), enabling the prediction of safe and effective dosing regimens across populations [11].

This application note details the principles, experimental strategies, and advanced analytical methodologies—particularly using NONMEM for parameter estimation—to study saturable elimination throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Quantitative Characterization of Elimination Kinetics

The fundamental difference between linear and saturable elimination is quantitatively distinct, impacting all key pharmacokinetic parameters. The following table contrasts the characteristics of both kinetic processes [12] [9].

Table 1: Characteristics of First-Order vs. Zero-Order (Saturable) Elimination Kinetics

| Pharmacokinetic Parameter | First-Order (Linear) Elimination | Zero-Order (Saturable) Elimination |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Principle | A constant fraction of drug is eliminated per unit time. | A constant amount of drug is eliminated per unit time. |

| Rate of Elimination | Proportional to drug concentration (Rate = ke × [C]). | Constant, independent of drug concentration (Rate = Vmax). |

| Mathematical Description | dC/dt = -ke × C | dC/dt = -Vmax |

| Plasma Concentration-Time Profile | Exponential decay. Linear on a semi-log plot. | Linear decay. |

| Half-life (t½) | Constant, independent of dose. | Increases with increasing dose/concentration. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Increases proportionally with dose. | Increases more than proportionally with dose. |

| Time to Eliminate Drug | Independent of dose (~4-5 half-lives). | Dependent on dose; longer with higher doses. |

| Clinical Dose Predictability | Highly predictable; doubling dose doubles exposure. | Unpredictable; small dose increases can cause large exposure spikes. |

| Common Examples | Most drugs at therapeutic doses (e.g., amoxicillin, lorazepam). | Phenytoin, salicylates (high dose), ethanol, paclitaxel [9]. |

The Michaelis-Menten equation bridges these concepts, describing the velocity (V) of an enzymatic reaction or saturable process as a function of substrate concentration ([S]) [10]:

V = (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S])

Where:

- Vmax is the maximum elimination rate (capacity).

- Km (Michaelis constant) is the substrate concentration at half of Vmax, representing the affinity of the enzyme/transporter for the substrate.

At very low concentrations ([S] << Km), the equation simplifies to V ≈ (Vmax/Km) × [S], exhibiting first-order kinetics. At high concentrations ([S] >> Km), V ≈ Vmax, and elimination becomes zero-order and saturable [10] [9].

Protocols for Characterizing Saturable Elimination

Protocol for In Vitro Michaelis-Menten Parameter Estimation Using NONMEM

Adapted from the simulation study by Cho & Lim (2018) [10] [13].

Objective: To determine the most accurate and precise method for estimating Vmax and Km from in vitro enzyme kinetic data, comparing traditional linearization methods with nonlinear estimation in NONMEM.

Materials & Software:

- R Statistical Software (with

deSolvepackage) - NONMEM (Version 7.3 or higher)

- Simulated or experimental time-course substrate concentration data.

Procedure:

Data Generation/Collection:

- For simulation studies: Generate substrate depletion time-course data for multiple initial substrate concentrations (e.g., 20.8, 41.6, 83, 166.7, 333 mM) using the M-M differential equation:

d[S]/dt = - (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S]). Incorporate realistic residual error models (additive, proportional, or combined) [10]. - For experimental data: Conduct in vitro metabolic stability assays with human liver microsomes or recombinant enzymes, measuring substrate loss over time at 5-6 different starting concentrations.

- For simulation studies: Generate substrate depletion time-course data for multiple initial substrate concentrations (e.g., 20.8, 41.6, 83, 166.7, 333 mM) using the M-M differential equation:

Data Preparation for Different Estimation Methods:

- NM (NONMEM Nonlinear): Use the raw [S]-time data directly.

- LB (Lineweaver-Burk) & EH (Eadie-Hofstee): Calculate initial velocity (Vi) for each concentration from the linear slope of the early time points. Transform data: LB uses

1/Vi vs. 1/[S]; EH usesVi vs. Vi/[S][13]. - NL (Nonlinear Vi-[S]): Use the calculated Vi and corresponding [S] pair.

- ND (Nonlinear Delta): Calculate the average rate between adjacent time points (VND) and the midpoint concentration ([S]ND) [13].

Parameter Estimation in NONMEM:

- Code the appropriate structural model for each method in NONMEM control files.

- For method NM, implement the differential equation directly.

- For methods LB and EH, use linear models on the transformed data. For NL and ND, use the M-M algebraic equation.

- Use the First-Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE) method with interaction.

- Perform estimation for all datasets (simulated replicates or experimental runs).

Analysis & Comparison:

- For each method, compile the estimated Vmax and Km values.

- Calculate measures of accuracy (e.g., median relative error) and precision (e.g., 90% confidence interval width) relative to the known true values (simulation) or the most robust estimate.

- Expected Outcome: As demonstrated by Cho & Lim, nonlinear regression fitting the full [S]-time data (NM method) typically provides the most accurate and precise parameter estimates, especially with complex error structures, outperforming traditional linearization methods (LB, EH) [10].

Protocol for Identifying Saturable Elimination in Phase I Clinical Data Using Machine Learning

Informed by Certara's application of machine learning for PK/PD modeling [14].

Objective: To efficiently identify the structural PK model—including the potential for saturable (Michaelis-Menten) elimination—that best describes complex Phase I clinical trial data.

Materials & Software:

- Phase I rich concentration-time data.

- Machine learning-enabled pharmacometric software (e.g., containing genetic algorithm capabilities).

- Standard NONMEM/Pirana for final model refinement.

Procedure:

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA):

- Plot individual patient concentration-time profiles.

- Plot AUC vs. Dose. A greater-than-proportional increase suggests saturable elimination or absorption [15].

- Plot clearance (CL) vs. concentration. A decreasing trend with higher concentrations suggests saturable elimination.

Define the Model Space:

- Define a set of plausible structural models to be tested. This is a critical step driven by the scientist.

- Absorption: First-order with/without lag time, sequential zero-first order, distributed delay function.

- Distribution: 1-, 2-, or 3-compartment models.

- Elimination: Linear (first-order) clearance vs. Michaelis-Menten (saturable) clearance.

- Covariates: Include potential relationships (e.g., weight on volume, age on clearance).

Machine Learning Model Search:

- Configure a genetic algorithm or other global search algorithm to explore the defined model space.

- The algorithm will automatically run hundreds to thousands of model configurations, evaluating each based on a fitness score (e.g., objective function value penalized for number of parameters) [14].

- The search is non-sequential, evaluating combinations of features (e.g., dual-compartment with saturable elimination) that might be missed in manual stepwise building.

Model Evaluation and Selection:

- Review the top-performing models identified by the ML algorithm.

- Perform standard pharmacometric diagnostics on the leading candidates: goodness-of-fit plots, visual predictive checks, precision of parameter estimates.

- Final Selection: The scientist makes the final decision based on statistical fit, parsimony, and biological plausibility. The ML tool provides robust, data-driven candidates [14].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Identifying Saturable Kinetics in Clinical Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Saturable Elimination

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Saturable Elimination Research |

|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Metabolism Systems | Human liver microsomes (HLM), recombinant CYP enzymes, hepatocytes. | Provide the biological enzymes to conduct in vitro kinetic studies for estimating initial Vmax and Km values for small molecules. |

| Transport Assay Systems | Transfected cell lines (e.g., MDCK, HEK293) overexpressing specific transporters (OATP1B1, P-gp). | Characterize saturable active transport processes that may contribute to uptake or elimination. |

| Target Proteins (for Biologics) | Soluble recombinant target antigens, cell lines expressing membrane-bound targets. | Essential for characterizing the target-binding affinity (KD) and capacity (Rmax) in TMDD assays, a key saturable pathway for biologics. |

| Simulation & Modeling Software | R (with deSolve, nlmixr), NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix NLME. |

The primary platform for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling, enabling population estimation of M-M parameters from clinical data. |

| Global Optimization Algorithms | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithms (GA). | Address challenges in nonlinear model fitting, such as parameter identifiability and convergence, by searching the global parameter space [16]. |

| Specialized NONMEM Extensions | P-NONMEM [16], Fractional Differential Equation (FDE) subroutines [17]. | Extend NONMEM's capability for complex models: PSO integration for robust estimation [16]; FDEs for modeling anomalous "power-law" kinetics sometimes linked to nonlinear elimination [17]. |

| Machine Learning Platforms for MIDD | Certara's ML tools, custom Python/R scripts using TensorFlow/Scikit-learn. | Automate the exploration of complex PK model spaces to efficiently identify the inclusion of saturable elimination mechanisms [14]. |

Advanced Analytical Considerations & NONMEM Workflow

Addressing Parameter Identifiability in Nonlinear Models

A major challenge in estimating M-M parameters (Vmax, Km) from in vivo data is statistical non-identifiability, where multiple parameter combinations yield an equally good fit to the data [16]. This often leads to estimation failures or unstable results in NONMEM.

Protocol Mitigation Strategies:

- Informative Prior Design: Collect rich data across a wide dose range, especially with doses designed to produce concentrations near and above the estimated Km.

- Use of Global Optimizers: Implement hybrid algorithms like LPSO (Particle Swarm Optimization coupled with local search) within or alongside NONMEM. As derivative-free methods, they are less prone to failure from singularity issues and can better navigate complex objective function landscapes to find global solutions [16].

- Model Simplification: If Vmax and Km are not jointly identifiable, consider fixing one parameter to a literature value from in vitro studies (e.g., Km) and estimating the other (Vmax in vivo).

NONMEM Workflow for Population M-M Parameter Estimation

Diagram 2: NONMEM Workflow for Population Michaelis-Menten Analysis

Application Across Modalities: Small Molecules vs. Biologics

The manifestation and analysis of saturable elimination differ between drug classes:

Small Molecules: Saturable elimination is primarily metabolism-driven. The focus is on characterizing the specific enzymes involved (e.g., via chemical inhibition assays in vitro) and applying the standard M-M framework. Phenytoin and high-dose aspirin are classic examples [9]. The NONMEM model typically adds a Michaelis-Menten clearance term:

CL = (Vmax / (Km + C)).Biologics (e.g., mAbs): Saturable elimination is often target-mediated (TMDD). At low doses, the drug binds with high affinity to its target, and the drug-target complex is internalized and degraded, creating a high-capacity, saturable elimination pathway. At higher doses, the target is saturated, and linear, non-specific clearance pathways dominate [11]. Modeling is more complex, often requiring a quasi-equilibrium or quasi-steady-state approximation of the full TMDD model within NONMEM, which still relies on estimating a saturation constant (Km) related to target affinity and turnover.

In both cases, the accurate estimation of saturation parameters is critical for first-in-human dose prediction, optimizing dosing regimens for Phase II/III, and predicting drug-drug interaction potential (for small molecules) [11].

NONMEM (Nonlinear Mixed Effects Model) is a computer program written in FORTRAN 90/95, designed for fitting general nonlinear regression models to data, with specialized application in population pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) [18] [19]. Developed by Lewis Sheiner and Stuart Beal at the University of California, San Francisco, it has become the industry-standard software for population PK/PD analysis for over 30 years [20] [21]. The software is particularly powerful for analyzing data with sparse sampling or variable designs across individuals, as it accounts for both inter-individual (random effects) and intra-individual variability, as well as measured covariates (fixed effects) [18] [19].

The NONMEM system comprises three core components [20] [18]:

- NONMEM: The foundational, general nonlinear regression program.

- PREDPP (PRED for Population Pharmacokinetics): A specialized subroutine library that handles standard and complex kinetic models, freeing users from coding common differential equations. It includes a suite of

ADVANmodel subroutines [19]. - NM-TRAN (NONMEM Translator): A preprocessor that translates user-friendly control streams and data files into the formats required by NONMEM [20] [18].

The current version, NONMEM 7.6, includes advanced estimation methods such as Stochastic Approximation Expectation-Maximization (SAEM) and Markov-Chain Monte Carlo Bayesian Analysis (BAYES, NUTS), along with support for complex mathematical constructs like delay differential equations (ADVAN16, ADVAN17) and distributed delay convolutions [20]. It also supports parallel computing to reduce run times for large problems [20].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and relationship between these core components and the user's inputs.

NONMEM System Architecture and Workflow

Core Components and Model Library

NONMEM's power for pharmacometric analysis is largely enabled by the PREDPP library. Users select a pre-defined model type via ADVAN subroutines in their control stream. For research focused on Michaelis-Menten kinetics, ADVAN10 is directly applicable as it implements a one-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination [19]. Other ADVAN subroutines support a wide range of linear and nonlinear PK/PD models.

Table: Selected PREDPP (ADVAN) Model Subroutines [19]

| Model Subroutine | Compartments | Basic Parameters | Model Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADVAN1 | 1 Central, 1 Output | K, V | One-compartment linear model. |

| ADVAN2 | 1 Depot, 1 Central, 1 Output | KA, K, V | One-compartment model with first-order absorption. |

| ADVAN3 | 1 Central, 1 Peripheral, 1 Output | K, K12, K21 | Two-compartment linear mammillary model. |

| ADVAN4 | 1 Depot, 1 Central, 1 Peripheral, 1 Output | KA, K, K23, K32 | Two-compartment model with first-order absorption. |

| ADVAN10 | 1 Central, 1 Output | VM, KM | One-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination. |

| ADVAN13 | General Nonlinear | User-defined | General nonlinear model with stiff/non-stiff ODE solver (LSODA). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For conducting NONMEM-based Michaelis-Menten research, the following components are essential.

Table: Essential Toolkit for NONMEM-based Research

| Item | Function / Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM Software | The core estimation engine for performing nonlinear mixed-effects modeling [20]. | Licensed annually from ICON plc. Version 7.6 is the latest [20]. |

| Fortran Compiler | Required to compile NONMEM's source code into an executable program [20] [22]. | Intel Fortran Compiler 9.0+ or gFortran for Windows/Linux are common [20]. |

| Control Stream File (.ctl) | A user-written text file containing all modeling instructions, commands, and model code for NM-TRAN [19] [22]. | Defines the structural model ($SUB, $PK), error model ($ERROR), estimation method ($EST), and requested output ($TABLE). |

| Data File (.csv or .prn) | A text file containing the experimental or clinical data for analysis [19] [22]. | Must include required data items (e.g., ID, TIME, DV, AMT) in a space- or comma-delimited format. |

| Interface/Manager | Third-party tools that facilitate project management, run execution, and graphical diagnostics [19]. | Examples include Pirana, Wings for NONMEM (WFN), and Perl Speaks NONMEM (PsN). |

| Graphical Diagnostic Tool | Software for generating diagnostic plots (e.g., goodness-of-fit, VPC) from NONMEM output tables [23]. | R (with packages like xpose), Xpose, or custom scripts in Python/MATLAB. |

Application to Michaelis-Menten Parameter Estimation

The Michaelis-Menten equation (V = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])) is fundamental for characterizing enzyme kinetics and saturable elimination processes in drug metabolism [24]. Accurate estimation of its parameters, the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) and the Michaelis constant (Km), is critical for in vitro to in vivo extrapolation and predicting nonlinear PK.

Traditional linearization methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee) are prone to statistical bias because they distort the error structure of the data. Nonlinear mixed-effects modeling with NONMEM provides a more robust framework by directly fitting the nonlinear model to the data, properly handling both fixed effects (typical parameter values) and random effects (inter-experiment/inter-individual variability) [24].

Comparative Performance of Estimation Methods

A key simulation study directly compared the performance of various estimation methods for Michaelis-Menten parameters [24]. The results unequivocally support the use of nonlinear methods in NONMEM.

Table: Performance Comparison of Michaelis-Menten Parameter Estimation Methods [24]

| Estimation Method | Category | Relative Accuracy & Precision for Vmax and Km | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Method (NM) in NONMEM | Nonlinear, Mixed-Effects | Most accurate and precise | Provides the most reliable parameter estimates by correctly specifying the error model. |

| Traditional Linearization Methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk) | Linear, Transform-based | Less accurate and precise | Amplifies error and distorts variance, leading to biased parameter estimates. |

| Iterative Two-Stage (ITS) | Hybrid, Nonlinear | Intermediate performance | More robust than linearization but generally less efficient than full population methods like FOCE or SAEM. |

The study found that the superiority of NONMEM's nonlinear estimation was particularly evident when data followed a combined (proportional plus additive) error model, which is common in real-world biological data [24]. This makes NONMEM the preferred tool for reliable Michaelis-Menten parameter estimation in pharmacological research.

Experimental Protocols for Michaelis-Menten Analysis

This section provides detailed, actionable protocols for setting up and executing a NONMEM analysis aimed at estimating Michaelis-Menten parameters, as informed by simulation studies and tutorial guides [24] [23].

Protocol 1: Simulation-Based Validation of Method Performance

Objective: To validate and compare the accuracy of different estimation methods for Vmax and Km using simulated in vitro elimination kinetic data [24].

Define True Parameters & Model:

- Set population values for

Vmax(e.g., 100 nmol/min/mg) andKm(e.g., 10 µM). - Define an error model: combined additive (

σ_add) and proportional (σ_prop) error is recommended (e.g.,DV = IPRED * (1 + ε₁) + ε₂, whereε₁andε₂are normally distributed with mean 0 and variancesσ_prop²andσ_add²).

- Set population values for

Generate Simulation Dataset:

- Using software like R, generate substrate concentrations (

[S]) over a range (e.g., 0.2Km to 5Km). - For each

[S], calculate the true reaction velocity (V) using the Michaelis-Menten equation. - Add random noise to

Vbased on the defined error model to create observed values (DV). - Replicate this process to create

N(e.g., 1000) simulated datasets [24].

- Using software like R, generate substrate concentrations (

Prepare NONMEM Data File:

- Structure a .csv file with columns:

SIM,ID,TIME,DV,CONC. UseTIMEas a placeholder if not time-course data;CONCholds the substrate concentration ([S]).

- Structure a .csv file with columns:

Develop NONMEM Control Stream:

- Use

$SUBROUTINE ADVAN10 TOL=6for Michaelis-Menten kinetics. - In

$PK: DefineVM = THETA(1) * EXP(ETA(1))andKM = THETA(2) * EXP(ETA(2)). Set initialTHETAvalues close to the true simulated values. - In

$ERROR: DefineIPREDusing the Michaelis-Menten equation with model parameters, and defineY = IPRED + IPRED*EPS(1) + EPS(2)for a combined error model. - Use an estimation method like

FOCEwithINTERACTIONin$ESTIMATION.

- Use

Execute and Analyze:

- Run NONMEM for each simulated dataset or use the

$SIMULATIONfunctionality. - For each run, record the estimated

VmaxandKm. - Calculate performance metrics (e.g., relative bias, precision) across all simulations to compare with other methods [24].

- Run NONMEM for each simulated dataset or use the

Protocol 2: Population Analysis of Enzyme Kinetic Data

Objective: To estimate typical population values and inter-assay variability of Vmax and Km from a real in vitro experiment conducted with multiple enzyme preparations (e.g., different hepatocyte lots) [23].

Data Assembly and Exploration:

- Compile data from all experiments. Essential data items:

ID(experiment/lot number), substrate concentration (CONCorSSas a steady-state indicator), and observed reaction velocity (DV). - Perform exploratory graphical analysis (velocity vs. concentration) to check for saturable kinetics and outliers.

- Compile data from all experiments. Essential data items:

Create NONMEM Data File:

- Format data as a space- or comma-delimited text file. Map columns using

$INPUTin the control stream (e.g.,$INPUT ID TIME DV CONC AMT). UseAMT=0for observation records.

- Format data as a space- or comma-delimited text file. Map columns using

Base Model Development:

- Control Stream Setup:

$PROBLEMPopulation Michaelis-Menten Kinetics$DATAyour_data.csvIGNORE=@$SUBROUTINE ADVAN10 TOL=6$ABBR(Optional, for advanced reparameterization)

- Parameter Definition (

$PK):- Define typical population parameters:

TVVM = THETA(1)andTVKM = THETA(2). - Define inter-individual variability (IIV) using exponential error models:

VM = TVVM * EXP(ETA(1))andKM = TVKM * EXP(ETA(2)). - Initial

THETAestimates can come from prior literature or graphical estimates.

- Define typical population parameters:

- Error Model (

$ERROR):- Define the individual prediction:

IPRED = (VM * CONC) / (KM + CONC). - Choose a residual error model. A proportional error is often suitable:

Y = IPRED + IPRED*EPS(1).

- Define the individual prediction:

- Estimation and Output:

$ESTIMATION METHOD=FOCE INTERACTION MAXEVAL=9999 SIGDIGITS=3$TABLE ID TIME IPRED PRED RES WRES CWRES NOPRINT ONEHEADER FILE=sdtab1$TABLE ID ETA1 ETA2 NOPRINT ONEHEADER FILE=patab1

- Control Stream Setup:

Model Evaluation:

- Run the model and assess convergence (successful covariance step).

- Generate diagnostic plots (e.g., PRED vs. DV, CWRES vs. PRED) using the output tables to evaluate goodness-of-fit [23].

Covariate Model Building (Optional):

- If experiment metadata is available (e.g., protein content, donor age), test for covariate relationships on

VmaxorKmin the$PKblock using linear or power functions (e.g.,TVVM = THETA(1) * (PROT/MEANPROT)THETA(3)). - Use objective function value (OFV) changes and diagnostic plots to guide model selection.

- If experiment metadata is available (e.g., protein content, donor age), test for covariate relationships on

The logical process for developing and refining a population Michaelis-Menten model is summarized in the diagram below.

Population Michaelis-Menten Model Development Workflow

Advanced Features and Future Directions

NONMEM 7.6 includes sophisticated features that extend its utility beyond standard PK/PD modeling, several of which are relevant for complex kinetic analyses [20] [25].

- Delay Differential Equations (DDEs): Modeled via

ADVAN16andADVAN17, these are essential for capturing physiological delays (e.g., in cell proliferation or indirect response models) [20] [25]. - Nonparametric and Bayesian Methods: The software supports nonparametric estimation of parameter distributions, which is valuable when random effects are non-normal [26]. Bayesian analysis (

BAYESandNUTSsampling) allows for formal incorporation of prior knowledge [20]. - Cutting-Edge Research: Recent extensions demonstrate NONMEM's adaptability, such as the implementation of fractional differential equation (FDE) models to describe anomalous kinetics or power-law behavior, which can offer more parsimonious models for complex data [17].

NONMEM remains the definitive software for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling in drug development and basic pharmacological research. Its rigorous framework for population parameter estimation, exemplified by its superior performance in estimating Michaelis-Menten constants compared to linearization methods, provides scientists with reliable and interpretable results [24]. The structured protocols for simulation and analysis, combined with its advanced capabilities for handling complex biological processes, ensure that NONMEM will continue to be an indispensable tool for quantifying and predicting nonlinear kinetics in therapeutic research.

Abstract Integrating Michaelis-Menten (MM) kinetics into a Nonlinear Mixed Effects (NLME) modeling framework is essential for accurately characterizing the saturable, non-linear elimination of numerous drugs. This integration involves defining a structural pharmacokinetic (PK) model with MM parameters (Vmax, Km), distinguishing population-level fixed effects from inter-individual random effects, and quantifying residual unexplained variability. Within software like NONMEM, this allows for the analysis of sparse, real-world clinical data to estimate typical population parameters, identify influential covariates, and quantify variability, thereby informing optimized dosing strategies. This application note provides detailed protocols and methodologies for the successful implementation and evaluation of population PK models incorporating MM elimination, framed within a broader thesis on advanced parameter estimation using NONMEM.

1. Introduction: Thesis Context and Rationale This work is situated within a broader thesis investigating robust methodologies for parameter estimation in NONMEM, with a focus on complex, non-linear kinetics. Michaelis-Menten elimination is a fundamental non-linear process where the elimination rate approaches a maximum velocity (Vmax) as concentration increases, with Km representing the concentration at half Vmax. In population modeling, the goal is to estimate the typical values (fixed effects) of Vmax and Km for a population, understand how they vary between individuals (random effects), and account for residual error [27]. This is formally executed within an NLME framework, which simultaneously analyzes data from all individuals, making it uniquely powerful for sparse clinical data [28]. Accurately defining and diagnosing these components—fixed effects, random effects (hierarchically modeled as inter-individual, inter-occasion), and residual error—is critical for developing a model that is both biologically plausible and statistically sound, ultimately supporting drug development decisions from first-in-human studies through to personalized dosing [28] [29].

2. Foundational Components of the NLME-MM Framework A population PK model integrating MM kinetics is composed of interconnected structural, statistical, and covariate sub-models.

- 2.1. Structural (PK) Model: The core kinetic model describes the typical concentration-time profile. For a one-compartment model with intravenous bolus administration and MM elimination, the differential equation is: dA/dt = - (Vmax * C) / (Km + C), where A is amount and C is concentration (C = A/V). Vmax and Km are the key structural parameters to be estimated [30] [31].

- 2.2. Statistical Model: This defines the variability components.

- Fixed Effects (θ): The typical population values for parameters (e.g., TVVmax, TVKm).

- Random Effects:

- Inter-individual Variability (IIV): Modeled using a log-normal distribution to ensure positivity. For example,

Vmaxᵢ = TVVmax * exp(ηᵢ_Vmax), where ηᵢVmax is a random variable from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance ω²Vmax [27] [30]. - Inter-occasion Variability (IOV): Accounts for variability within an individual across different dosing occasions [32].

- Residual Unexplained Variability (RUV): Discrepancy between individual model predictions and observed concentrations. Common models include additive (

Cobs = Cpred + ε), proportional (Cobs = Cpred * (1 + ε)), or combined error structures [27].

- Inter-individual Variability (IIV): Modeled using a log-normal distribution to ensure positivity. For example,

- 2.3. Covariate Model: Explains IIV by relating parameters to patient characteristics (e.g., weight, genotype, renal function). A covariate relationship on Vmax, for instance, can be linear (

TVVmax = θ₁ + θ₂*(WT/70)) or allometric (TVVmax = θ₁ * (WT/70)^θ₂) [30]. The inclusion of the ALDH2 genotype on volume of distribution in an alcohol PK model is a specific example of a genetic covariate [31].

3. Protocol: Implementing a Population MM Model in NONMEM

- 3.1. Data Assembly and Preparation

- Dataset Structure: Prepare a NONMEM-compliant dataset with required columns:

ID,TIME,AMT,DV(dependent variable, e.g., concentration),CMT(compartment number),EVID(event identifier), and covariates (e.g.,WT,AGE,GENO). Ensure accurate handling of dosing records and observations [33]. - Data Quality: Perform graphical exploratory data analysis. Identify and document records below the limit of quantification (BLQ). Modern methods (e.g., M3 method) that incorporate the likelihood of BLQ observations are preferred over simple imputation (e.g., LLOQ/2) [27] [32].

- Dataset Structure: Prepare a NONMEM-compliant dataset with required columns:

- 3.2. Model Development and Estimation Strategy

- Base Model Building:

- Start with a structural PK model (e.g., 1- or 2-compartment) with linear elimination to establish a baseline.

- Introduce MM elimination in place of linear clearance. This often requires switching to an ADVAN13 (general differential equation) subroutine in NONMEM unless a built-in MM option is available.

- Add IIV to key parameters (typically on Vmax and Km). Use an exponential error model. Estimate the OMEGA variance-covariance matrix.

- Test different residual error models (additive, proportional, combined).

- Parameter Estimation: Choose an appropriate estimation method. The First Order Conditional Estimation with interaction (FOCEI) is often a robust starting point. For complex MM models or datasets with high IIV/RUV, more advanced methods like Stochastic Approximation Expectation Maximization (SAEM) or Importance Sampling (IMP) may be required for stability and accuracy [32]. Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are also applicable, especially with informative priors [31].

- Covariate Analysis:

- Stepwise Forward Inclusion: Test plausible covariate-parameter relationships (e.g., weight on Vmax, creatinine clearance on Km) using likelihood ratio tests (LRT). A drop in objective function value (OFV) > 3.84 (χ², p<0.05, 1 d.f.) suggests significance.

- Backward Elimination: Refine the full model by removing non-significant covariates (increase in OFV < 6.63, p<0.01, 1 d.f.) to develop a final parsimonious model [27].

- Base Model Building:

- 3.3. Model Evaluation and Validation

- Goodness-of-Fit (GOF): Assess basic GOF plots: Observations (DV) vs. Population Predictions (PRED), DV vs. Individual Predictions (IPRED), and Conditional Weighted Residuals (CWRES) vs. TIME or PRED [32].

- Visual Predictive Check (VPC): The gold standard for model evaluation. Simulate 1000 datasets using the final model parameter estimates and overlay the observed data percentiles with the simulated prediction intervals. This assesses the model's predictive performance across the entire concentration-time profile [17].

- Numerical Predictive Check (NPC): Provides a quantitative summary of the VPC.

- Bootstrap: Perform a non-parametric bootstrap (e.g., 1000 samples) to assess the robustness and precision of the final parameter estimates and generate confidence intervals.

4. Data Presentation: Key Parameter Estimates and Model Diagnostics Table 1: Comparison of NONMEM Estimation Methods for NLME-MM Models

| Estimation Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Suitability for MM Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FO (First Order) | Linearizes the random effects model. | Fast, stable. | Can produce biased estimates with high IIV or RUV. | Poor; not recommended for final MM models. |

| FOCE/I | Conditional estimation; linearizes residual error. | Generally robust, accurate for many problems. | May struggle with highly non-linear models or sparse data. | Good standard choice. |

| SAEM | Stochastic sampling of the random effects space. | Accurate for complex, highly non-linear models. | Computationally intensive, results have stochastic variability. | Very good for complex MM models. |

| Bayesian (MCMC) | Uses prior distributions combined with data likelihood. | Incorporates prior knowledge; useful for sparse data. | Choice of priors influences results; computationally intensive. | Excellent when informative priors exist (e.g., from in vitro Vmax/Km) [32] [31]. |

Table 2: Example Covariate Relationships in a Structural Parameter Model

| Parameter (P) | Covariate Model Form | NONMEM Code Snippet (Example) | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax | Allometric scaling by weight | TVVMAX = THETA(1) * (WT/70)THETA(2) |

Metabolic capacity scales with body size. |

| Km | Linear influence of age | TVKM = THETA(3) + THETA(4)*(AGE-40) |

Affinity of the enzyme may change with age. |

| Vd | Influence of genotype (indicator variable) | TVV = THETA(5) * (1 + THETA(6)*GENO) |

GENO=1 for variant allele, affecting distribution [31]. |

Table 3: Example Final Parameter Estimates from a Population MM Analysis (Hypothetical Data)

| Parameter | Description | Population Estimate (RSE%) | Inter-Individual Variability (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TVVmax (mg/h) | Typical max elimination rate | 10.5 (5) | 30% |

| TVKm (mg/L) | Typical Michaelis constant | 2.1 (12) | 45% |

| TVV (L) | Typical volume of distribution | 35.0 (4) | 25% |

| θₐₗₗₒₘ | Allometric exponent on Vmax | 0.75 (Fixed) | - |

| Prop. Err (%) | Proportional residual error | 15 (10) | - |

5. Experimental Protocol: Case Study on Alcohol PK with MM Elimination

- 5.1. Aim: To develop a population PK model for alcohol incorporating Michaelis-Menten elimination and to identify significant covariates (e.g., body weight, ALDH2 genotype) [31].

- 5.2. Background: Alcohol exhibits capacity-limited metabolism via alcohol dehydrogenase. Data from 34 healthy Japanese subjects with sparse sampling times were available.

- 5.3. Experimental Methodology:

- Data: Collected blood alcohol concentration-time data after controlled administration. Covariates included demographic data and ALDH2 genotype.

- Software: Analysis performed using NONMEM 7.3 with MCMC Bayesian estimation.

- Model Building: a. Structural Model: A one-compartment model with zero-order input (absorption) and Michaelis-Menten elimination was selected. b. Statistical Model: IIV was added to Vmax, Km, and Vd using exponential models. An informative prior distribution for Km was incorporated from an external study to stabilize estimation due to limited data in the later elimination phase. c. Covariate Model: Covariates (weight, age, genotype) were tested on all parameters using a Bayesian framework, evaluating changes in posterior distributions.

- Model Evaluation: Conducted via posterior predictive checks and examination of Bayesian diagnostics (e.g., trace plots for convergence).

- 5.4. Key Findings: The final model estimated a typical Vd of 49.3 L. A significant covariate effect was found, with ALDH21/2 genotype associated with a 20.4 L lower Vd compared to the ALDH21/1 genotype. The use of Bayesian priors allowed for stable parameter estimation despite data limitations [31].

6. Visualizing the Framework and Workflow

Diagram 1: Workflow for Developing a Population PK Model with MM Kinetics.

Diagram 2: Hierarchical Relationship in an NLME-MM Model.

7. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Resources for NLME-MM Analysis Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Population MM Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM Software | Industry-standard software for NLME modeling. Implements estimation algorithms (FO, FOCE, SAEM, MCMC). | Required for executing the modeling protocols described herein [32] [29]. |

| PDx-Pop / Pirana | Interface and workflow manager for NONMEM. Facilitates model run management, covariate screening, and basic graphics. | Greatly improves efficiency and reproducibility of modeling projects. |

| R / RStudio with Packages | Statistical computing environment for data preparation, advanced graphics (ggplot2), model diagnostics (xpose), and simulation. | Essential for creating VPCs, custom GOF plots, and conducting bootstraps [17]. |

| Perl Speaks NONMEM (PsN) | Perl-based toolkit for NONMEM. Automates key tasks like VPC, bootstrap, and stepwise covariate modeling (SCM). | Critical for robust model evaluation and automated workflows. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Parallel processing resource. | Significantly reduces runtime for intensive methods like SAEM, IMP, or large bootstraps. |

| Curated PK/PD Dataset | Clean, well-structured dataset compliant with NONMEM format. | Must include accurate dosing records, concentration data, and covariates. The foundation of any analysis [27] [33]. |

| In Vitro Enzyme Kinetic Data | Prior estimates of Vmax and Km from preclinical studies. | Can be used to inform Bayesian prior distributions in clinical model development, stabilizing estimation [31]. |

This document details the essential prerequisites and methodologies for conducting robust Michaelis-Menten (MM) pharmacokinetic analysis using the NONlinear Mixed Effects Modeling (NONMEM) software. Within the broader thesis investigating advanced parameter estimation for saturable elimination processes, this guide provides the foundational application notes and protocols. Accurate estimation of Vmax (maximum elimination rate) and Km (substrate concentration at half Vmax) is critical for predicting nonlinear pharmacokinetics, informing dosing regimens, and understanding drug-drug interactions [10]. NONMEM, the industry-standard tool for population analysis, is particularly suited for this task as it employs nonlinear mixed-effects modeling to simultaneously analyze sparse or heterogeneous data from all individuals, providing superior accuracy and precision compared to traditional linearization methods [19] [10].

Prerequisites: Data Structure and Software Environment

Successful MM analysis in NONMEM requires correctly formatted data and an appropriate software ecosystem.

2.1 Data File Structure and Requirements The data file is a comma- or space-delimited text file where each row represents a record (dosing or observation) for an individual [19]. For MM analysis, specific data items are mandatory. The core structure is outlined below:

Table 1: Essential Data Items for NONMEM Analysis using PREDPP

| DATA ITEM | DESCRIPTION | REQUIREMENT for MM Analysis | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|---|

ID |

Unique subject identifier | Mandatory | 1, 2, 3 |

TIME |

Elapsed time since start of analysis | Mandatory | 0, 2.5, 5.0 |

AMT |

Dose amount (for dosing records) | Mandatory for dosing events | 1000, 0 |

CMT |

Compartment number | Required if using ADVAN subroutines | 1, 2 |

EVID |

Event identifier (0=obs., 1=dose, etc.) | Mandatory | 0, 1, 4 |

DV |

Dependent variable (observed concentration) | Mandatory for observation records | 45.2, 12.7 |

MDV |

Missing dependent variable indicator | Recommended (1=missing, 0=present) | 0, 1 |

RATE |

Infusion rate (if applicable) | Optional for zero-order inputs | -2 (for modeled rate) |

For a typical single-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination (ADVAN10), the central compartment is designated as CMT=1 and the output compartment as CMT=2 [19]. Accurate EVID and MDV coding is crucial for NONMEM to correctly process the data stream [19].

2.2 Software and System Requirements NONMEM is written in ANSI Fortran 95 and requires a compatible compiler (e.g., Intel Fortran, gFortran) [20]. As model estimation can be computationally intensive, a fast machine with at least 1-2 GB of dedicated memory is recommended [20]. The software is licensed annually through ICON plc [20]. Effective analysis is facilitated by a suite of supporting tools:

Table 2: Supporting Software Ecosystem for NONMEM Workflow

| Tool Category | Example Software | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Graphical User Interface (GUI) | Pirana, Census 2 [34] | Provides an environment to run, manage, and edit models, and interpret output. |

| Scripting & Automation | Perl Speaks NONMEM (PsN) [19] [34] | Aids in model development through tools for validation (bootstrap, VPC), covariate screening, and data handling. |

| Statistical & Graphical Analysis | R (with packages like xpose, IQRtools) [35] [34] |

Used for data preparation, exploratory analysis, generation of diagnostic plots, and custom post-processing. |

| Code Editor | Notepad++ (with NONMEM syntax highlighting) [35] | Facilitates writing and debugging control stream files. |

Core Experimental Protocol for MM Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps to implement and estimate a Michaelis-Menten model in NONMEM, based on best practices and simulation studies [10].

3.1 Control Stream Configuration for MM Kinetics

The control stream (filename.ctl) directs all modeling actions. Key code blocks for a basic MM model are:

$PROB: Define the problem title.$INPUT: List the data items (ID, TIME, AMT, DV, CMT, EVID, ...) in the exact order they appear in the data file.$DATA: Specify the data file name and options (e.g.,IGNORE=@to ignore header lines).$SUBROUTINE: SelectADVAN10for a one-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination andTRANS1[19]. This directly provides the parameters VM (Vmax) and KM (Km).$PK: Define the population (typical) parameters and inter-individual variability (IIV).

$ERROR: Define the residual error model. For MM analysis, a combined additive and proportional error model is often appropriate [10]:

$THETA,$OMEGA,$SIGMA: Provide initial estimates for fixed effects (THETAs), variances of IIV (OMEGAs), and residual error (SIGMA).$ESTIMATION: Choose the estimation method. For MM models, First Order Conditional Estimation with interaction (FOCEI) or the more advanced Stochastic Approximation Expectation-Maximization (SAEM) are recommended [32] [10].

3.2 Workflow Diagram: From Data to Validated Model The following diagram illustrates the iterative, cyclical workflow for population PK/PD model development in NONMEM, from data preparation to final model validation [35].

Diagram: Iterative Workflow for Population PK/PD Model Development

3.3 Selection of Estimation Method The choice of estimation algorithm is critical for accurate MM parameter estimation. A simulation study demonstrated that nonlinear methods in NONMEM outperform traditional linearization techniques (Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee) [10].

Table 3: Comparison of Estimation Methods for MM Parameters [32] [10]

| Method | Description | Key Characteristic | Suitability for MM |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Order (FO) | Linearizes inter- and intra-individual variability. | Fast but approximate; biased with high variability/sparse data. | Low - Not recommended for final estimation. |

| FOCE with Interaction | Conditional estimation linearizing residual error. | More accurate than FO for most problems. | High - Standard reliable choice. |

| Laplace | Similar to FOCE but uses second-order approximation. | Used for highly nonlinear models or non-normal data. | Medium - Can be tried if FOCE fails. |

| Stochastic Approximation EM (SAEM) | Monte Carlo method using Markov Chain sampling. | Accurate for complex models; handles sparse data well. | Very High - Often optimal for MM kinetics [32] [10]. |

| Importance Sampling (IMP) | Monte Carlo EM method sampling around the mode. | Provides precise objective function value. | High - Good for final evaluation after SAEM. |

| Iterative Two Stage (ITS) | Approximate EM method using conditional modes. | Faster than FOCE but less accurate for sparse data. | Medium - Useful for initial exploratory runs. |

Based on the comparative study, the SAEM method (available in NONMEM 7.6) followed by a final IMP evaluation is highly recommended for MM analysis as it provides the most accurate and precise estimates, especially with realistic combined error structures [32] [10].

3.4 Model Components and Parameter Relationships A clear understanding of the model components and their mathematical relationships is fundamental. The following diagram depicts the structure of a one-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination and the flow of parameters through the modeling process.

Diagram: Components and Relationships in a Michaelis-Menten PK Model

Validation and Diagnostic Protocol

4.1 Standard Model Evaluation Metrics A robust MM model must pass several diagnostic checks [35]:

- Successful Estimation: Minimum of the objective function found, with successful covariance step.

- Parameter Precision: Relative standard errors (RSE%) for fixed and random effects typically <30-50%.

- Diagnostic Plots: Observations vs. Population (PRED) and Individual (IPRED) predictions should be scattered evenly around the line of identity. Conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) vs. PRED or TIME should be randomly scattered around zero.

- Visual Predictive Check (VPC): A simulation-based check where the majority of observed data falls within the prediction intervals of simulated data, confirming the model adequately describes central tendency and variability.

4.2 Simulation-Based Validation (Bootstrap) Internal validation is performed using the nonparametric bootstrap [35]:

- Resample: Generate 500-1000 bootstrap datasets by randomly sampling subjects with replacement from the original dataset.

- Refit: Re-estimate the final model on each bootstrap dataset.

- Analyze: Calculate the median and 95% confidence interval of the parameter estimates from all successful runs. Compare these intervals with the original parameter estimates; close agreement indicates model stability.

4.3 Quantitative Validation from Comparative Studies A simulation study provides quantitative benchmarks for expected performance. When estimating MM parameters from in vitro-like elimination kinetic data, NONMEM's nonlinear methods (NM in the study) showed superior accuracy and precision [10].

Table 4: Validation Metrics from Simulation Study [10]

| Estimation Method | Accuracy (Median Bias) | Precision (90% CI Width) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| NONMEM (NM) | Lowest bias | Narrowest CI | Most reliable and accurate method. |

| Traditional Linearization (LB, EH) | Higher bias | Wider CI | Performance worsens with combined error models. |

| Other Nonlinear Regression (NL, ND) | Moderate bias | Moderate CI | Better than linearization but inferior to NM. |

This evidence strongly supports the use of NONMEM's full time-course nonlinear estimation over methods relying on initial velocity calculations or linear transformations for MM analysis [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit for MM Analysis

Table 5: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Tool/Resource | Category | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM 7.6+ | Core Software | Industry-standard engine for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling. Essential for population MM parameter estimation [20] [32]. |

| Pirana | Workflow GUI | Manages run execution, output comparison, and integrates with PsN/R. Critical for organizing complex modeling projects [34]. |

| Perl Speaks NONMEM (PsN) | Automation Toolkit | Executes essential validation techniques like bootstrap and VPC. Required for rigorous model qualification [35] [34]. |

R with xpose/ggplot2 |

Diagnostic Graphics | Creates standardized diagnostic plots (e.g., OV vs. PRED, CWRES) for model evaluation and publication [35]. |

| Simulated MM Datasets | Validation Reagent | Used for method qualification and troubleshooting. The study by Cho et al. (2018) provides an excellent template for generating validation data [10]. |

| SAEM Estimation Method | Algorithm | The preferred estimation method in NONMEM for MM models due to its accuracy in handling nonlinear kinetics and combined error structures [32] [10]. |

| Fractional Differential Equation Subroutine | Advanced Tool | For modeling anomalous kinetics (power-law behavior). Useful for extending MM analysis to complex systems where standard ODEs fail [17]. |

| Nonparametric Estimation (NONP) | Diagnostic Tool | Evaluates the shape of parameter distributions. Helps diagnose and correct for bias when inter-individual variability is non-normal [26]. |

Implementing the Michaelis-Menten Model in NONMEM: Code, Estimation, and Application

Within the specialized field of pharmacometrics, the accurate estimation of Michaelis-Menten (MM) parameters (VM and KM) is critical for characterizing the nonlinear, saturable elimination kinetics exhibited by numerous therapeutic agents. This application note is framed within a broader thesis investigating advanced methodologies for MM parameter estimation using NONMEM (NONlinear Mixed Effects Modeling), the industry-standard software for population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) analysis [19]. While NONMEM's PREDPP library provides a dedicated, analytically solved one-compartment MM model (ADVAN10), complex real-world scenarios—such as multi-compartment distribution with MM elimination or intricate absorption models—necessitate a more flexible approach [36] [37]. This document details the implementation of these complex MM structures using PREDPP's general differential equation solvers (ADVAN6, ADVAN8, ADVAN13, etc.) and the $DES subroutine, bridging a gap between standard functionality and advanced research needs [38] [39]. The protocols herein are designed for researchers and drug development professionals requiring robust, customizable models for precise parameter estimation.

Core Components: PREDPP, ADVAN, and $DES

The NONMEM system consists of three primary components: the estimation engine (NONMEM), the translator (NM-TRAN), and the pharmacokinetic prediction suite (PREDPP) [18]. PREDPP contains a library of ADVAN (ADVANCE) subroutines, each representing a specific PK model or class of models [40] [41]. The user selects an ADVAN via the $SUBROUTINES record in the control stream.

Table 1: Key PREDPP ADVAN Subroutines for Linear and Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

| ADVAN | Model Description | Solution Type | Basic Parameters (TRANS1) | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADVAN1 | One-compartment linear | Analytical | K, V | Simple IV bolus kinetics [40] [19] |

| ADVAN2 | One-compartment with 1st-order absorption | Analytical | KA, K | Oral dosing [40] [19] |

| ADVAN3 | Two-compartment linear | Analytical | K, K12, K21 | IV bolus with distribution [40] [19] |

| ADVAN10 | One-compartment with Michaelis-Menten elimination | Analytical | VM, KM | Standard saturable elimination [40] [37] |

| ADVAN5/7 | General linear model (up to 999 comps) | Matrix Exponential | User-defined | Complex linear compartmental structures [36] [38] |

| ADVAN6/8/13 | General nonlinear model | ODE Solution | User-defined | Custom MM models, complex kinetics [38] [37] |

For models beyond the predefined set (ADVAN1-4, 10-12), PREDPP offers general subroutines. ADVAN6, ADVAN8, and ADVAN13 are used for models defined by ordinary differential equations (ODEs) [38] [37]. When using these, the user must provide a $DES block in the control stream (or a separate DES Fortran subroutine). This block contains the code that defines the right-hand side of the differential equations governing drug movement between compartments [39]. This is the essential mechanism for coding custom MM elimination within a multi-compartment structure or alongside other nonlinear processes.

Workflow for Selecting ADVAN Subroutines for Michaelis-Menten Models

Methodology: Coding MM Elimination with $DES

The implementation of a user-defined MM model involves a sequential configuration of NM-TRAN records. The following protocol outlines the steps for coding a two-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination from the central compartment.

Step 1: Define the Model Structure with $MODEL

The $MODEL block declares the number and type of compartments. For a two-compartment mammillary model with a peripheral tissue compartment and an optional output compartment, the code is:

Step 2: Select a General Nonlinear ADVAN

The $SUBROUTINES record specifies the ODE solver. ADVAN13 (using LSODA) is often preferred for its ability to handle both stiff and non-stiff equations efficiently [37].

The TOL value controls the numerical integration precision [38].

Step 3: Declare and Assign Parameters in $PK

The $PK block is used to define the model's parameters, including fixed effects, random effects (ETAs), and covariate relationships. Typical parameters for this model include central volume (V1), inter-compartmental clearance (Q), peripheral volume (V2), and the MM parameters (VM, KM).

Step 4: Code the Differential Equations in $DES

This is the core of the custom model. The $DES block calculates the derivative (DADT) for each compartment amount (A). For the two-compartment MM model:

The equation MM_RATE implements the standard Michaelis-Menten velocity equation, where the rate of elimination is a function of the amount A(1) in the central compartment [17] [39].

Step 5: Define the Observation Model in $ERROR

Finally, the $ERROR block links the model predictions to the observed data, typically defining a residual error model.

Two-Compartment Model with Michaelis-Menten Elimination Pathway

Application Protocols and Parameter Estimation

Protocol for a Complex Absorption MM Model

Chatelut et al. (1999) modeled the absorption of alpha interferon using simultaneous first-order and zero-order processes into a one-compartment body with linear elimination [38]. Adapting this for MM elimination demonstrates the flexibility of the $DES approach.

Experimental Methodology & NM-TRAN Implementation:

- Model Schematic: Two parallel depot compartments (DEPOT1 for first-order, DEPOT2 for zero-order absorption) feed into a central compartment with MM elimination.

- $MODEL: Define three compartments:

DEPOT1,DEPOT2,CENTRAL. - $PK: Declare parameters:

KA(first-order absorption rate),D2(zero-order absorption duration),FZ(fraction absorbed via first-order),VM,KM,V. - $DES Code:

- Data File: Requires two dosing records per dose: one to

CMT=1(amount = FZDOSE) and one toCMT=2(amount = (1-FZ)DOSE).

Protocol for MM Parameter Estimation Methods

Accurate estimation of VM and KM is computationally challenging due to the nonlinearity. The choice of estimation algorithm in NONMEM is critical.

Table 2: Comparison of NONMEM Estimation Methods for Michaelis-Menten Models

| Method | Principle | Advantages for MM | Disadvantages for MM | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Order (FO) | Linearizes random effects around zero [32]. | Fastest computation. | High bias with large inter-individual variability or sparse data [32]. | Initial model exploration only. |

| First Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE) | Linearizes around conditional estimates of ETAs [32]. | More accurate than FO, standard for nonlinear PK. | May fail with high residual error or severe nonlinearity. | Standard choice for most MM models with rich data. |

| FOCE with INTERACTION | Accounts for interaction between inter- and intra-individual error [32]. | Improved accuracy when residual error is large. | Slightly slower than FOCE. | Default choice for final MM model estimation. |

| Importance Sampling (IMP) / SAEM | Monte Carlo methods for exact likelihood evaluation [32]. | Most accurate for complex nonlinearities and sparse data. | Computationally intensive, stochastic variability in estimates. | Complex models, problematic convergence with FOCE. |

Recommended Estimation Protocol:

- Initialization: Use literature or naive pooled estimates for

THETAinitial values. SetOMEGAdiagonal elements to moderate values (e.g., 0.09 for 30% CV). - Step 1 - Preliminary Exploration: Run FO estimation to check data structure and identify obvious problems.

- Step 2 - Base Model Estimation: Switch to FOCE with INTERACTION. Ensure successful termination and examine gradient messages.

- Step 3 - Covariate Modeling: Continue with FOCE-INTERACTION to test significant covariates on parameters like

VM. - Step 4 - Final Validation: If convergence is difficult or data are sparse, confirm final parameter estimates using a Monte Carlo method (IMP or SAEM) [32].

Advanced Applications and the Scientist's Toolkit

Incorporating Fractional Differential Equations (FDEs)

Recent research extends nonlinear mixed-effects modeling to systems defined by Fractional Differential Equations (FDEs), which describe anomalous kinetics and memory effects [17]. A one-compartment model with MM elimination can be reformulated as a fractional FDE:

where ^C_0D^α_t is the Caputo fractional derivative of order α (0<α<1) [17]. Implementing this in NONMEM requires a user-supplied subroutine that replaces the $DES block with a numerical solver for FDEs, demonstrating the extensibility of the platform for cutting-edge MM research [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MM Modeling with $DES

| Tool/Component | Function in MM Model Development | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PREDPP Library (ADVAN10) | Provides a pre-built, analytically solved one-compartment MM model for validation and comparison [40] [37]. | Serves as a benchmark for custom $DES models. |

| General Nonlinear ADVAN (6,8,13) | Provides the ODE solver framework necessary for implementing custom MM structures [38] [37]. | Choice depends on model stiffness; ADVAN13 (LSODA) is often robust. |

$DES Block |

The core "reagent" for coding the differential equations that define the custom MM kinetic process [39]. | Must correctly calculate derivatives DADT. Use compact array format for large models. |

| TOL Option | Sets the tolerance for the numerical ODE solver, controlling precision and stability [38] [37]. | A value of 4-6 is typical. Adjust if runs fail due to integration error. |

| MU Referencing | A coding technique (using MU_ prefix) that improves estimation efficiency, especially with EM methods [32]. |

Highly recommended for complex models to speed up convergence. |

| PDx-Pop, Pirana, PsN | Third-party modeling environments that provide workflow management, visualization, and automated tools (e.g., VPC, bootstrap) [19]. | Essential for efficient, reproducible, and robust model development. |

Implementing Michaelis-Menten pharmacokinetics using the $DES subroutine and general ADVANs in PREDPP unlocks a powerful paradigm for pharmacometric research. This approach transcends the limitations of precompiled solutions, allowing researchers to construct and estimate parameters for sophisticated, mechanism-based models that accurately reflect complex biological processes—from multi-compartment saturation kinetics to parallel absorption pathways. Mastery of this technique, combined with a strategic understanding of estimation algorithms and diagnostic tools, positions scientists to tackle challenging nonlinear PK problems, ultimately contributing to more informed drug development decisions and optimized therapeutic regimens. The methodologies outlined here provide a foundational protocol that can be adapted and extended as part of an advanced thesis in modern pharmacometric analysis.

Within the broader thesis on advanced pharmacometric modeling using NONMEM, the generation of robust initial estimates for Michaelis-Menten parameters—the maximum elimination rate (Vmax) and the substrate concentration at half Vmax (Km)—is not a mere preliminary step but a critical determinant of research success. Nonlinear mixed-effects models, which are fundamental to population pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis, are inherently dependent on adequate initial parameter estimates for efficient and correct convergence of the estimation algorithm [42]. Poor initial estimates can lead to failed minimization, termination at local minima yielding biologically implausible parameter values, or protracted model-building cycles plagued by instability [43].

This challenge is particularly acute for Michaelis-Menten kinetics, a cornerstone model for characterizing saturable enzymatic elimination. The parameters Vmax and Km are often correlated, and their estimation can be sensitive to the design and quality of the data [13]. Framed within a thesis exploring NONMEM's full potential, this document provides detailed application notes and protocols. It moves beyond simplistic rule-of-thumb guesses, presenting a systematic, multi-strategy toolkit for generating scientifically defensible initial estimates. These strategies are designed to enhance model reliability, reduce development time, and form the foundation for robust covariate analysis and clinical simulations in model-informed drug development [43] [44].

Computational Foundations: NONMEM and Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

2.1 NONMEM Architecture for PK Modeling

NONMEM (NONlinear Mixed Effects Modeling) is a software program that fits PK/PD models to data while accounting for inter-individual and intra-individual variability [19]. Its workflow involves a control stream (.ctl file), a data file, and output files. The control stream specifies the model, parameters, and estimation methods. A key component is PREDPP, a library of pre-compiled PK models accessed via the $SUBROUTINES record using ADVAN and TRANS subroutines [19].

2.2 Implementing Michaelis-Menten Elimination in NONMEM