Mastering Nonlinear Least Squares for Accurate Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to nonlinear least squares (NLLS) parameter estimation for enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mastering Nonlinear Least Squares for Accurate Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to nonlinear least squares (NLLS) parameter estimation for enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, contrasting NLLS with problematic linearization methods, and explores advanced applications including the novel 50-BOA for efficient inhibition analysis and progress curve modeling. The guide addresses critical challenges such as parameter identifiability and optimal experimental design, while comparing the performance of NLLS against alternative machine learning approaches. It synthesizes best practices for obtaining reliable, publication-ready kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km, Ki) essential for robust in vitro-in vivo extrapolation and confident drug interaction predictions.

From Michaelis-Menten to Modern Fitting: Foundations of Nonlinear Least Squares in Enzyme Kinetics

Nonlinear Least Squares (NLLS) is a fundamental parameter estimation method used to fit a mathematical model to experimental data by minimizing the sum of squared differences between observed and model-predicted values [1]. In the context of enzyme kinetics research, which is central to drug development and systems biology, these models are inherently nonlinear, such as the Michaelis-Menten equation or complex multi-enzyme cascade models. The objective is to find the kinetic parameters (e.g., V_max, K_m, rate constants) that best explain the observed reaction velocity or time-course data [2] [3]. Unlike linear regression, NLLS requires iterative optimization algorithms to navigate the parameter space, as no closed-form analytical solution exists for the parameters of a nonlinear model [4].

Mathematical Formulation and Objective Function

The core objective of NLLS is to minimize an objective function, typically the Sum of Squared Residuals (SSR). For a set of m observations and a model function f that depends on independent variables x_i and a vector of n unknown parameters β, the problem is formally defined [1]:

- Residuals: r_i = y_i - f(x_i, β) for i = 1, ..., m.

- Objective Function (SSR): S(β) = Σ_{i=1}^{m} r_i^2 = Σ_{i=1}^{m} [y_i - f(x_i, β)]^2.

The goal is to find the parameter vector β̂ that minimizes S(β): β̂ = argmin_β S(β).

The minimization occurs in an iterative fashion. Starting from initial parameter guesses (β⁰), the algorithm linearizes the model around the current estimate and solves a sequence of linear least-squares problems to find a parameter update (Δβ) [1] [5]. A common foundation for these algorithms is the Gauss-Newton method, which solves the normal equations [1]: (JᵀJ) Δβ = Jᵀ Δy. Here, J is the m × n Jacobian matrix, where element J_ij = ∂f(x_i, β)/∂β_j, and Δy is the vector of differences between observations and current predictions [1]. For data with non-uniform reliability, a weighted least squares formulation can be used, incorporating a diagonal weight matrix W into the normal equations: (JᵀWJ) Δβ = JᵀW Δy [1] [3].

Quantitative Comparison of Kinetic Models and Fitting Methods

Table 1: Common Nonlinear Kinetic Models in Enzyme Research

| Model Name | Functional Form | Typical Parameters | Application in Enzyme Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis-Menten | v = (V_max * [S]) / (K_m + [S]) | V_max, K_m | Standard model for initial velocity of single-substrate reactions [2]. |

| Hill Equation | v = (V_max * [S]^n) / (K_{0.5}^n + [S]^n) | V_max, K_{0.5}, n | Models cooperativity in multi-subunit or regulated enzymes [2]. |

| First-Order Decay | [P] = [P]_∞ (1 - exp(-k * t)) | [P]_∞, k | Models irreversible product formation or protein denaturation over time [3]. |

| Mass Action System | ODEs: d[S]/dt = -k_f[E][S] + k_r[ES] etc. | k_f, k_r, k_cat | Detailed mechanistic models of multi-step enzymatic reactions [2]. |

Table 2: Performance of Different Parameter Estimation Methods [3]

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages / Biases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Least Squares (NLS) | Minimizes sum of squared residuals. | Well-established theory; efficient use of data [4]. | Can produce biased estimates if residual variance is not constant (heteroscedasticity) [3]. |

| Weighted Least Squares (WLS) | Minimizes weighted sum of squares; weights = 1/error_variance [1]. | Can eliminate bias from heteroscedastic data; produced lowest errors in case study [3]. | Requires good initial guesses and prior knowledge of error structure [3]. |

| Two-Step Linearized Method | Transforms nonlinear model to linear form for initial estimate. | Provides excellent initial guesses for NLS/WLS; has analytical solution [3]. | Can distort error structure, leading to less accurate final predictions [3]. |

| Bayesian Inference | Estimates parameter probability distributions using prior knowledge and data [2]. | Quantifies full parameter uncertainty; allows for model selection [2]. | Computationally intensive; requires specification of prior distributions. |

Detailed Experimental and Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: NLLS Workflow for Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation

- Experimental Design & Data Acquisition:

- Conduct assays to measure reaction velocity (v) across a range of substrate concentrations ([S]) or product formation over time.

- Include sufficient replicates to estimate experimental error. Use a negative control.

- Record data as ([S]i, vi) pairs or (timei, [Product]i) pairs.

- Model Selection:

- Based on mechanistic understanding, select an appropriate nonlinear model (e.g., from Table 1).

- Parameter Initialization:

- Provide initial guesses for all parameters. Use linear transformation (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plot), literature values, or estimates from a two-step method [3].

- Algorithm Execution & Convergence:

- Validation & Uncertainty Quantification:

- Examine residuals: they should be randomly scattered around zero. Non-random patterns suggest a poor model fit.

- Calculate confidence intervals for parameters. For NLLS, these are often derived from the approximate covariance matrix σ²(JᵀJ)⁻¹, where σ² is the estimated error variance [8].

- Report the final parameter estimates ± standard error or confidence intervals.

Protocol 2: Bayesian Parameter Estimation for Model Selection [2]

- Define a Suite of Models: Develop a set of candidate models that embed different mechanistic hypotheses (e.g., different kinetic formulations or regulatory mechanisms).

- Specify Priors: For each model parameter, define a prior probability distribution based on literature or plausible physical ranges.

- Perform Bayesian Inference: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to compute the posterior probability distribution of parameters for each model, given the experimental data.

- Model Selection: Compute metrics like the Expected Log Pointwise Predictive Density (ELPD) to identify the model that best predicts the data without overfitting [2].

- Prediction with Uncertainty: Use the posterior distributions to generate model predictions that inherently include the propagated parameter uncertainty.

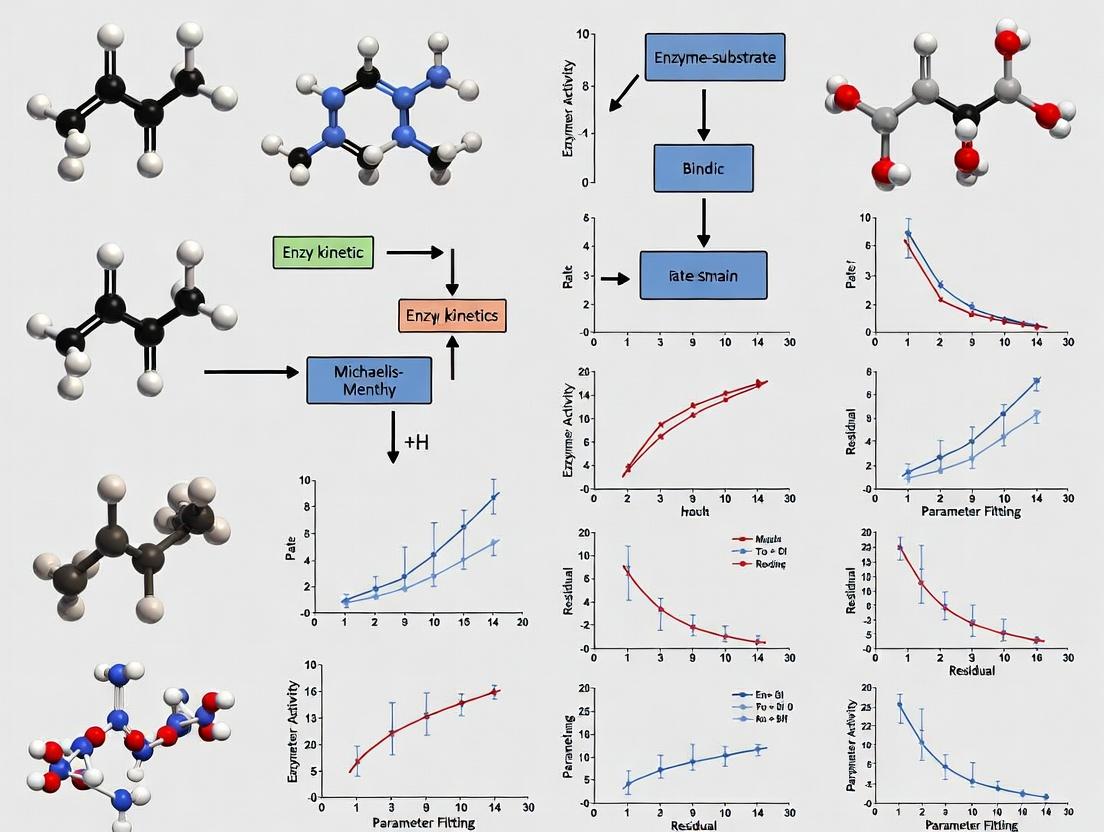

Visualizing the NLLS Framework and Workflow

NLLS Parameter Estimation Iterative Cycle

Data-Informed Model Development Workflow [2]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Considerations for NLLS Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst whose parameters (k_cat, K_m) are being estimated. | Source, purity, and specific activity must be consistent; concentration must be known accurately for mechanistic models. |

| Substrate(s) | The molecule(s) transformed by the enzyme. | High purity; prepare a concentration series spanning ~0.2-5× K_m for robust estimation. Stability over assay time is critical. |

| Cofactors & Buffers | Provide necessary chemical environment (pH, ions, coenzymes like ATP/NADH). | Buffer must maintain pH throughout reaction; cofactor concentration may be a fixed parameter or variable in the model. |

| Detection System | Measures reaction progress (e.g., spectrophotometer, fluorimeter, HPLC). | Defines the observable (y_i). Signal-to-noise ratio and linear range directly impact data quality and residual structure. |

| Stopping Reagents/Quenchers | Halts the reaction at precise times for endpoint assays. | Ensures accurate measurement of time (x_i), a critical independent variable in progress curve models. |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Validates assay function and defines background signal. | Essential for correctly defining the baseline (zero) for the observed signal, impacting all calculated y_i values [3]. |

| Calibration Data File | Links raw instrument output to concentration units. | Must be acquired and applied consistently. Errors here create systematic bias in all observations. |

| Software (e.g., R, MATLAB, Dakota) | Implements the NLLS optimization algorithm and statistical analysis. | Choice affects available algorithms (Gauss-Newton, Levenberg-Marquardt, NL2SOL [8]), weighting options, and uncertainty calculations. |

The quantitative analysis of enzyme kinetics provides a fundamental framework for understanding biological catalysis, designing therapeutic inhibitors, and optimizing industrial biocatalysts. Central to this analysis are the Michaelis-Menten equation and its extensions for various inhibition modes, which are inherently nonlinear functions of substrate and inhibitor concentrations [9] [10]. This article details application notes and experimental protocols for determining the kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km, kcat) that define these models.

This work is situated within a broader thesis on nonlinear least squares (NLLS) parameter estimation. Traditional linear transformations (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plots) are prone to error propagation and can obscure the true kinetic mechanism [11]. Direct nonlinear regression of the untransformed rate data to the appropriate model is statistically superior, providing more accurate and precise parameter estimates with reliable confidence intervals [11] [12]. The protocols herein emphasize this modern computational approach, bridging foundational biochemical theory with robust data analysis practice for researchers and drug development professionals.

Foundational Kinetic Models: Equations and Parameters

The classical model describes a single-substrate, irreversible reaction where the enzyme (E) binds substrate (S) to form a complex (ES), which then yields product (P) and free enzyme [9].

Under steady-state assumptions, the initial reaction velocity (v) is given by the Michaelis-Menten equation:

where Vmax is the maximum reaction velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, and Km (the Michaelis constant) is the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity [9] [10]. Vmax is the product of the catalytic constant (kcat) and the total enzyme concentration ([E]0). The specificity constant, kcat/Km, measures catalytic efficiency [9].

Inhibition Models: Inhibitors (I) modulate enzyme activity by binding to the free enzyme, the enzyme-substrate complex, or both. The governing equations are nonlinear functions of both [S] and [I] [13].

- Competitive Inhibition: Inhibitor competes with substrate for the active site. Apparent Km increases; Vmax is unchanged.

- Non-Competitive Inhibition: Inhibitor binds at a site distinct from the active site, affecting catalysis. Vmax decreases; Km is unchanged.

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: Inhibitor binds only to the ES complex. Both apparent Vmax and Km decrease.

- Mixed Inhibition: Inhibitor binds to both E and ES with different dissociation constants (Ki and αKi). Both Vmax and apparent Km are altered [13] [14].

Table 1: Characteristic Parameters of Representative Enzymes [9]

| Enzyme | Km (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ |

Table 2: Summary of Reversible Inhibition Models

| Inhibition Type | Binding Site | Effect on Vmax | Effect on Apparent Km | Rate Equation v = |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Active site | Unchanged | Increases | V_max [S] / ( [S] + K_m(1 + [I]/K_i) ) |

| Non-Competitive | Allosteric site | Decreases | Unchanged | (V_max [S]) / ( (K_m + [S])(1 + [I]/K_i) ) |

| Uncompetitive | ES complex only | Decreases | Decreases | V_max [S] / ( K_m + S ) |

| Mixed | Allosteric site | Decreases | Increases or Decreases | V_max [S] / ( K_m(1 + [I]/K_i) + S ) |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Michaelis-Menten Parameters

This protocol outlines the procedure for obtaining initial velocity data and analyzing it via nonlinear least squares regression to determine Vmax and Km.

A. Reagent Preparation

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the purified enzyme in an appropriate stabilization buffer. Keep on ice.

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the substrate. Ensure it is soluble and stable under assay conditions.

- Prepare the assay buffer, typically containing required cofactors, metal ions, and maintaining optimal pH and ionic strength.

B. Initial Velocity Assay

- Design a substrate concentration series, typically spanning from ~0.2Km to 5Km (a preliminary experiment may be needed to estimate this range). Use at least 8-10 different [S] in duplicate or triplicate.

- For each reaction tube/well, first add assay buffer and substrate stock to achieve the desired final [S] in a total volume slightly less than the final reaction volume.

- Pre-incubate all components (except enzyme) at the assay temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C) for several minutes.

- Initiate the reaction by adding a small, fixed volume of enzyme stock. The enzyme concentration should be chosen so that ≤5% of the substrate is consumed during the measurement period to ensure initial rate conditions [15] [10].

- Monitor product formation or substrate depletion continuously (e.g., spectrophotometrically, fluorometrically) for a defined time, or quench the reaction at a precise time point (e.g., 30, 60, 90 seconds) for endpoint analysis.

- Convert the raw signal (e.g., absorbance) to concentration of product formed using an appropriate standard curve or molar extinction coefficient.

C. Data Analysis via Nonlinear Least Squares

- For each [S], calculate the initial velocity (v = Δ[P]/Δtime).

- Input the data pairs ([S], v) into a curve-fitting software package (e.g., BestCurvFit, Kintecus, GraphPad Prism) [16] [14].

- Select the Michaelis-Menten model (v = V_max[S] / (K_m + [S])).

- Perform unweighted or weighted nonlinear regression. The software iteratively adjusts Vmax and Km to minimize the sum of squared residuals between the observed v and the curve predicted by the model [11] [12].

- Report the best-fit parameters with their standard errors or 95% confidence intervals, and the goodness-of-fit metrics (e.g., R², residual plot). A residual plot showing random scatter confirms a good fit [14].

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing Enzyme Inhibition

This protocol extends the basic assay to diagnose inhibition type and determine the inhibition constant (Ki).

A. Assay Design for Inhibitor Titration

- Perform the standard Michaelis-Menten experiment (Section 3) in the absence of inhibitor (control).

- Repeat the full [S] series in the presence of at least three different, fixed concentrations of inhibitor [I], plus a condition with [I]=0. Choose [I] values expected to bracket the Ki.

B. Data Analysis and Mechanism Diagnosis

- Fit each dataset (at a given [I]) independently to the Michaelis-Menten equation to observe trends in the apparent Vmax and Km.

- Global Nonlinear Regression: For definitive analysis, fit all data simultaneously to the complete rate equation for a putative inhibition model (see Table 2) [11].

- Competitive Model: v = Vmax [S] / ( [S] + Km(1 + [I]/Ki) )

- Mixed Inhibition Model: v = Vmax [S] / ( Km(1 + [I]/Ki) + S )

- The shared parameters (Vmax, Km, Ki, α) are optimized across all data curves. Statistical comparison (e.g., via F-test) of the residual sum of squares for different models identifies the mechanism that best describes the data [11].

- Software like BestCurvFit can perform this global fitting and includes models for partial and hyperbolic inhibition [14].

Advanced Computational Framework: Nonlinear Parameter Estimation

Direct nonlinear fitting is superior to linearized methods. The core problem is to minimize the objective function (S), which is the sum of weighted squared residuals [12]:

where vobs,i is the observed velocity, vmodel,i is the velocity predicted by the nonlinear model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten or an inhibition equation) for a given set of parameters, and σi is the standard error of the observation.

Implementation: Algorithms such as the Levenberg-Marquardt method solve this iteratively [12]. This algorithm adaptively blends the inverse-Hessian (Newton) method and the gradient descent method for robust convergence. Modern software automates this process, providing parameter estimates, covariance matrices, and confidence intervals [16] [14].

Emerging Approaches: Recent research employs Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), particularly those trained with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, to model complex biochemical kinetics and estimate parameters, showing high accuracy compared to traditional numerical solvers [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Must be stable and active in the chosen assay buffer. Purity reduces confounding side-reactions. |

| Substrate Stock | High-purity solution of the target molecule. Concentration must be accurately known for Km determination. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains optimal pH, ionic strength, and provides necessary cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases) to support enzyme activity. |

| Inhibitor Compound | For inhibition studies. Typically prepared as a concentrated stock in DMSO or buffer. Control for solvent effects is critical. |

| Detection Reagents | Enable quantitation of product/substrate (e.g., NADH for dehydrogenases, chromogenic substrates, fluorescent probes). |

| 96/384-Well Plates | For high-throughput assay formats, enabling replication and multiple [S] and [I] conditions. |

| Microplate Reader | Instrument for high-throughput absorbance, fluorescence, or luminescence readings over time. |

Table 4: Software for Kinetic Analysis & Nonlinear Fitting

| Software | Primary Function | Key Feature for NLLS |

|---|---|---|

| BestCurvFit [14] | Nonlinear regression curve-fitting. | Internal library of 46 kinetic models; performs global fitting; statistical analysis of residuals. |

| Kintecus [16] | Chemical kinetic simulation & regression. | Fits parameters at exact measurement times; supports global data regression across multiple datasets. |

| GraphPad Prism | General scientific data analysis. | User-friendly interface for direct and global fitting of enzyme kinetic models with detailed diagnostics. |

| Custom Code (Python/R) | Flexible, script-based analysis. | Using libraries (e.g., lmfit in Python, nls in R) allows for complete control over model definition and fitting procedure. |

Visual Synthesis of Kinetic Mechanisms and Workflows

Michaelis-Menten Reaction Mechanism [9]

General Modifier Mechanism for Reversible Inhibition [13] [14]

Nonlinear Least Squares Parameter Estimation Workflow [11] [12]

The determination of accurate kinetic parameters—the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) and the Michaelis constant (Km)—is foundational to understanding enzyme function, designing inhibitors, and modeling metabolic pathways [18]. For decades, linear transformations of the Michaelis-Menten equation, primarily the Lineweaver-Burk (double reciprocal) and Eadie-Hofstee plots, have been standard tools for this purpose due to their graphical simplicity [19]. However, within the context of advanced research on nonlinear least squares (NLS) enzyme parameter estimation, these linearization methods are fundamentally flawed. They distort the error structure of experimental data, violate the assumptions of linear regression, and yield biased, imprecise parameter estimates [19] [20]. This application note details the mathematical and statistical pitfalls of these linear transformations, provides protocols for robust nonlinear alternatives, and frames the discussion within the imperative for reliable parameter estimation in systems biology and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and the Error Propagation Problem

The Michaelis-Menten Equation and Its Linear Transforms

The hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration [S] and reaction velocity v is described by the Michaelis-Menten equation:

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])

To extract Vmax and Km graphically, three primary linear transformations were historically employed [19] [21]:

Table 1: Linear Transformations of the Michaelis-Menten Equation

| Plot Type | Linear Form | x-axis | y-axis | Slope | y-intercept | x-intercept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (Double Reciprocal) | 1/v = (Km/Vmax)*(1/[S]) + 1/Vmax |

1/[S] |

1/v |

Km/Vmax |

1/Vmax |

-1/Km |

| Eadie-Hofstee | v = Vmax - Km*(v/[S]) |

v/[S] |

v |

-Km |

Vmax |

Vmax/Km |

| Hanes-Woolf | [S]/v = (1/Vmax)*[S] + Km/Vmax |

[S] |

[S]/v |

1/Vmax |

Km/Vmax |

-Km |

Fundamental Statistical Pitfalls: Error Structure Distortion

The central failure of linearization lies in its transformation of the experimental error. Assays typically exhibit a constant absolute error in the measured velocity v (homoscedastic variance) [20] [22]. Linear transformations distort this native error structure.

Lineweaver-Burk is the most egregious. Taking the reciprocal dramatically amplifies the relative error of low-velocity measurements, which occur at low substrate concentrations [19]. As noted, if v = 1 ± 0.1, then 1/v = 1 ± 0.1. However, if v = 10 ± 0.1, then 1/v = 0.1 ± 0.001. Low-velocity points are given disproportionate weight in the regression, biasing the fit [19].

Eadie-Hofstee is self-constrained, with the variable v appearing on both axes. This creates a spurious negative correlation between the plotted variables, violates the assumption of independent measurement errors for regression, and complicates error analysis [20].

All linear methods assume the transformed data meets the criteria for ordinary least-squares regression: normally distributed, homoscedastic errors on the y-axis and error-free x-values. These assumptions are invariably broken, leading to incorrect confidence intervals and compromised parameter reliability [20] [22].

Diagram: Error Propagation Pathway in Linearization. Linear transformations distort the native homoscedastic error of velocity measurements, leading to statistically invalid regression and biased parameters.

Quantitative Comparison of Estimation Methods

Simulation studies provide unequivocal evidence of the superiority of nonlinear regression. A 2018 study compared five estimation methods using 1,000 replicates of simulated Michaelis-Menten data with defined error models [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation Methods [20]

| Estimation Method | Key Characteristic | Relative Accuracy (Vmax/Km) | Relative Precision (Vmax/Km) | Robustness to Error Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | Linear fit of 1/v vs. 1/[S] | Low / Very Low | Low / Low | Poor (fails with combined error) |

| Eadie-Hofstee (EH) | Linear fit of v vs. v/[S] | Low / Low | Low / Low | Poor |

| Nonlinear (NL) | NLS fit of v vs. [S] | High / High | High / High | Good |

| Nonlinear Derivative (ND) | NLS fit of Δ[S]/Δt vs. [S] | Medium / Medium | Medium / Medium | Moderate |

| Nonlinear Modeling (NM) | NLS fit of full [S]-time course | Highest / Highest | Highest / Highest | Excellent |

Key Findings: The nonlinear modeling (NM) method, which fits the integrated rate equation to the full time-course data, provided the most accurate and precise estimates. Its superiority was most pronounced under a combined error model (additive + proportional), a realistic representation of experimental noise. Linear methods (LB, EH) consistently performed worst [20].

Protocols for Robust Nonlinear Parameter Estimation

Protocol 1: Direct Nonlinear Least Squares (NLS) Fit to Initial Velocity Data

This is the standard and recommended alternative to linear plots [20] [23].

Principle: Fit the untransformed Michaelis-Menten equation directly to initial velocity (v0) versus substrate concentration ([S]) data using an iterative NLS algorithm.

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Measure initial reaction velocities (

v0) across a minimum of 8-10 substrate concentrations, spaced geometrically (e.g., 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 x estimated Km). Ensure measurements are in the linear product formation phase. - Initial Parameter Guesses:

Vmax_guess≈ highest observedv0.Km_guess≈ substrate concentration at half ofVmax_guess.

- Software Implementation (e.g., R):

- Validation: Inspect the residuals plot (residuals vs. fitted

v0or vs.[S]) to check for homoscedasticity and lack of systematic trend. Use the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for model comparison if inhibition is suspected [24].

Protocol 2: Integrated Michaelis-Menten (IMM) Analysis for Product-Inhibited Reactions

When the reaction product is an inhibitor, conventional initial velocity measurements are inherently inaccurate, as the inhibitor is present from time zero [24]. The IMM method analyzes the full progress curve.

Principle: Fit a differential or integrated equation that incorporates product inhibition terms to the time-course of substrate depletion or product formation [24].

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Initiate reactions at multiple initial substrate concentrations (

[S]0). Monitor[S]or[P]continuously (e.g., via spectrophotometry) or with high time resolution. - Model Selection: For competitive product inhibition, the integrated rate equation is:

[P] - K' * ln(1 - [P]/[S]0) = Vmax * twhereK' = Km * (1 + [P]/Kic)andKicis the competitive inhibition constant of the product. More complex models exist for other inhibition types (uncompetitive, mixed) [24]. - Fitting: Use advanced modeling software (e.g., NONMEM, ADAPT, or dedicated packages in R/Python) capable of fitting differential equations.

- Discrimination: Use AIC to discriminate between rival inhibition models (e.g., competitive vs. mixed inhibition) [24].

Diagram: Workflow for Robust Kinetic Analysis with Model Discrimination. The process involves proposing mechanisms, fitting via NLS, and using statistical criteria like AIC to select the most appropriate model.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Source (species, tissue), isoenzyme form, and purification method must be documented [18]. | Stability under assay conditions; specific activity. Use EC number for unambiguous identification [18]. |

| Physiological Assay Buffer | Maintains pH, ionic strength, and cofactor conditions optimal for in vivo-like function [18]. | Avoid non-physiological pH or buffers that act as inhibitors/activators (e.g., phosphate, Tris effects) [18]. |

| Substrate Stock Solutions | Prepared at high concentration in assay-compatible solvent. | Verify solubility and stability. Use concentrations spanning 0.2-5x Km for a reliable fit. |

| Stop Solution (for endpoint) | Rapidly halts the enzymatic reaction at precise time points. | Must be 100% effective and compatible with detection method (e.g., acid, base, denaturant). |

| Internal Standards & Controls | For LC-MS or complex detection methods. | Corrects for sample preparation losses and instrument variability. |

| Software for NLS Regression | Performs parameter estimation and error analysis (e.g., R, Python SciPy, GraphPad Prism, NONMEM). | Must implement Levenberg-Marquardt or similar robust algorithm. Ability to fit user-defined models is essential [20] [24]. |

| Validated Kinetic Database | Source for literature parameters and experimental context (e.g., BRENDA, SABIO-RK) [18]. | Crucial: Check STRENDA (Standards for Reporting Enzymology Data) compliance for reliability assessment [18]. |

Linear transformations like the Lineweaver-Burk and Eadie-Hofstee plots are obsolete for quantitative parameter estimation in serious enzyme kinetics research. Their inherent distortion of error structure renders them statistically invalid and a source of significant inaccuracy [19] [20].

Recommendations for Researchers:

- Always use nonlinear least squares (NLS) regression to fit the untransformed Michaelis-Menten equation or its extended forms directly to data [20] [23].

- For reactions susceptible to product inhibition, employ integrated Michaelis-Menten (IMM) analysis of full time-course data to obtain accurate inhibition constants and avoid the pitfalls of initial velocity methods [24].

- Report data comprehensively, adhering to STRENDA guidelines. Provide the untransformed primary data (

[S],vor time-course), the fitted parameters with confidence intervals, and details of the error model and weighting scheme used in the NLS fit [18]. - In the broader thesis of NLS enzyme parameter estimation, focus must extend beyond mere fitting to include experimental design optimization, rigorous error structure analysis [22], and model discrimination to ensure that derived parameters are both statistically sound and biologically meaningful.

1. Introduction Within the broader thesis on nonlinear least squares for enzyme kinetic parameter estimation, the selection and configuration of the iterative optimization algorithm are critical. The Gauss-Newton (GN) and Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithms form the computational core for solving the nonlinear least-squares problem, minimizing the sum of squared residuals between observed reaction velocities and model-predicted values (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, competitive inhibition). These algorithms efficiently navigate the parameter space (e.g., V_max, K_m, K_i) to find the values that best fit the experimental data, a foundational step in quantitative pharmacology and drug discovery.

2. Comparative Algorithm Performance Metrics The following table summarizes key performance characteristics of the GN and LM algorithms based on current computational literature and their application to enzyme kinetic fitting.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Gauss-Newton and Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithms

| Characteristic | Gauss-Newton (GN) | Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Approximates Hessian using Jacobian (JᵀJ). | Damped hybrid of GN and gradient descent. |

| Update Rule | Δp = - (JᵀJ)⁻¹ Jᵀ r | Δp = - (JᵀJ + λI)⁻¹ Jᵀ r |

| Parameter λ (Lambda) | Not applicable. | Adaptive damping parameter. |

| Convergence Speed | Fast (quadratic) near optimum. | Slower than GN near optimum. |

| Robustness | Poor with poor initial guesses or ill-conditioned JᵀJ. | High; handles ill-conditioning well. |

| Primary Use Case | Well-specified models with good initial estimates. | Default choice for nonlinear least squares; robust. |

| Failure Modes | Singular or near-singular JᵀJ matrix. | Rare; may converge slowly if λ strategy is poor. |

3. Protocol: Implementing LM for Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation This protocol details the steps to estimate parameters for a Michaelis-Menten model with competitive inhibition using the LM algorithm.

3.1. Pre-Computational Experimental Phase

- Data Acquisition: Perform enzyme assays measuring initial velocity (v) across a matrix of substrate [S] and inhibitor [I] concentrations. Use technical replicates (n≥3).

- Data Curation: Average replicates, remove statistical outliers (e.g., Grubbs' test), and prepare a data matrix: [ [S]₁, [I]₁, v₁ ], ... , [ [S]ₙ, [I]ₙ, vₙ ].

- Model Definition: Define the nonlinear function f(p; [S], [I]) = (V_max · [S]) / ( K_m · (1 + [I]/ K_i) + [S] ).

- Parameter Vector Initialization (Critical): Provide initial guesses p₀ = [V_max, K_m, K_i]. Use linear transformations (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee) for V_max and K_m. Estimate K_i from preliminary IC₅₀ data.

3.2. Computational Estimation Phase (LM Algorithm Workflow)

- Set Hyperparameters: Configure convergence tolerances: TolFun (change in residuals) = 1e-9, TolX (change in parameters) = 1e-9, MaxIter = 400.

- Initialize: Set p = p₀, λ = 0.001. Compute initial residual vector r (observed - predicted).

- Iteration Loop: a. Compute Jacobian matrix J numerically (forward differences) or analytically. b. Compute proposed parameter update: Δp = - (JᵀJ + λ·diag(JᵀJ))⁻¹ Jᵀ r. c. Compute residuals r_new for candidate parameters p + Δp. d. Evaluate ρ = ( ||r||² - ||r_new||² ) / ( Δpᵀ (λ·diag(JᵀJ)·Δp + Jᵀ r) ). e. If ρ > 0 (update good): Accept update p = p + Δp. Decrease λ (e.g., λ = λ / 10). f. If ρ ≤ 0 (update poor): Reject update. Increase λ (e.g., λ = λ * 10). Recompute step.

- Check Convergence: Loop repeats until ||Jᵀ r||∞ < TolFun, ||Δp|| < TolX, or MaxIter is reached.

- Output: Final parameter estimates p_opt and covariance matrix C = σ² (JᵀJ)⁻¹ for error analysis.

3.3. Post-Estimation Analysis

- Goodness-of-Fit: Calculate R², reduced χ².

- Parameter Uncertainty: Compute confidence intervals from covariance matrix C (e.g., 95% CI = 1.96 * sqrt(diag(C))).

- Residual Analysis: Plot residuals vs. [S] and [I] to detect systematic bias.

- Model Validation: Perform cross-validation or use an independent dataset.

4. Visualization: LM Algorithm Logic and Estimation Workflow

Title: LM Algorithm Parameter Update Logic

Title: Enzyme Parameter Estimation Full Workflow

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Computational Resources

Table 2: Essential Tools for Computational Enzyme Parameter Estimation

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Purified Recombinant Enzyme | Target protein for kinetic characterization. Must be >95% pure, with known concentration. |

| Varied Substrate & Inhibitor Stocks | To generate the necessary concentration matrix for model fitting. |

| High-Throughput Microplate Reader | For efficient acquisition of initial velocity data under multiple conditions. |

| Numerical Computing Environment (e.g., Python/SciPy, MATLAB, R) | Platform for implementing LM algorithm and statistical analysis. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Script | To assess identifiability of parameters (e.g., K_i) and guide experimental design. |

| Bootstrapping/Jackknifing Code | For non-parametric estimation of parameter confidence intervals, complementing covariance matrix analysis. |

| Model Selection Criterion (AICc/BIC) | To objectively compare the fit of rival kinetic models (e.g., competitive vs. non-competitive inhibition). |

核心统计假设与理论基础

在酶动力学的非线性参数估计研究中,使用非线性最小二乘法拟合数据时,其数学基础依赖于几个关键的统计假设。这些假设确保了参数估计的一致性、无偏性和有效性,是后续统计推断和模型应用的根基 [25]。

非线性回归模型的一般形式为: y = f(x; θ) + ε 其中 y 是因变量(如反应速率),x 是自变量(如底物浓度),f 是关于参数向量 θ (如 Vₘₐₓ、 Kₘ)的非线性函数,ε 是随机误差项 [25]。

拟合过程的核心目标是找到参数 θ,使残差平方和最小化:SSE = Σ(yᵢ - ŷᵢ)² [25]。此优化过程的可靠性完全建立在以下关于误差项 ε 的假设之上:

表1:非线性回归的核心假设及其影响

| 假设 | 数学表述 | 对参数估计的影响 | 在酶动力学中的常见违反情况 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 独立性 | Cov(εᵢ, εⱼ) = 0, ∀ i ≠ j | 违反时导致标准误低估,显著性检验失效 | 连续时间点测量的自相关;批次效应;技术重复的非独立性 |

| 同方差性 | Var(εᵢ) = σ² (恒定) | 违反时估计值仍无偏,但效率降低,置信区间不准确 | 测量误差随信号强度增大(如高速率区吸光度读数误差增大) |

| 正态性 | ε ~ N(0, σ²) | 大样本下影响较小;小样本时影响置信区间和假设检验 | 反应速率存在下限(≥0)或存在异常值导致的偏态分布 |

| 误差结构 | ε 与 f(x; θ) 关系正确 | 模型误设导致所有估计有偏 | 使用不正确的动力学模型(如米氏方程拟合协同体系) |

假设验证的实验协议与诊断方法

协议:残差分析与诊断图生成

目的:系统性检验回归模型的残差是否满足独立性、同方差性和正态性假设。 适用范围:已完成初始非线性拟合(如基于米氏方程、Hill方程等)的酶动力学数据集。

材料与软件:

- 原始动力学数据([底物浓度],反应速率)

- 统计软件(如R语言、MATLAB、Python with SciPy)

- MATLAB中可使用

nlinfit、lsqcurvefit进行拟合,并用plotResiduals进行诊断 [25]。

实验步骤:

初始模型拟合:

- 使用适当的非线性拟合算法(如Levenberg-Marquardt)估计模型参数。

- 保存拟合值(ŷ)和原始观测值(y)。

计算与绘制残差:

- 计算普通残差:eᵢ = yᵢ - ŷᵢ。

- 计算标准化残差或学生化残差以方便识别异常值。

- 创建以下诊断图 [26]: a. 残差 vs. 拟合值图:检验同方差性。随机散点预示同方差;漏斗形预示异方差。 b. 残差 vs. 自变量图:检验模型形式误设(如未发现的非线性)。 c. 残差顺序图(索引图):检验独立性。随机波动预示独立;趋势或周期预示自相关。 d. 正态Q-Q图:检验正态性。点近似在45度直线上预示正态性良好。

统计检验:

- 同方差性检验:Breusch-Pagan检验或White检验。

- 独立性检验:Durbin-Watson检验(针对时间序列数据)。

- 正态性检验:Shapiro-Wilk检验或对残差绘制直方图。

数据分析:

- 若残差图显示随机散布,无明显模式,则假设得到支持。

- 若残差vs拟合值图显示漏斗形,表明可能存在异方差性,即误差方差随反应速率增大而改变 [26]。

- 若残差vs自变量图显示U型或弯曲趋势,表明模型可能缺失重要项或函数形式错误 [26]。

协议:误差结构识别与模型修正

目的:当诊断发现异方差或非正态性时,识别潜在的误差结构并实施加权回归或变量变换。

步骤:

探索误差方差与拟合值的关系:

- 将残差的绝对值(或平方)对拟合值作散点图或局部平滑回归(如LOESS)。

- 观察趋势:常见关系包括方差与拟合值成正比(Var(ε) ∝ ŷ)或与拟合值的平方成正比(Var(ε) ∝ ŷ²)。

选择并应用加权最小二乘法(WLS):

- 根据探索的关系指定权重。例如,若方差与 ŷ 成正比,则权重为 wᵢ = 1/ŷᵢ。

- 使用加权非线性最小二乘法重新拟合模型,最小化目标函数:Σ wᵢ(yᵢ - ŷᵢ)²。

考虑变量变换:

- 对于乘法误差或明显的异方差,可考虑对因变量进行变换(如对数变换、平方根变换)。

- 注意:变换会改变误差结构假设和模型的生物学解释。例如,对数变换可将乘法误差转为加法误差 [25]。

重新诊断:

- 对加权拟合或变换后数据拟合的新模型,重复2.1节的残差诊断步骤。

- 确认修正措施有效改善了同方差性和正态性。

先进建模技术与方案选择

当标准非线性回归假设持续被违反时,需考虑更先进的建模策略。

表2:常见问题与高级建模方案

| 违反类型 | 诊断特征 | 推荐的高级建模方案 | 关键注意事项 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 复杂异方差 | 残差方差与多个变量相关 | 广义最小二乘法(GLS):对方差-协方差矩阵建模 | 需要足够的重复观测来估计方差结构参数 |

| 显著非正态误差 | Q-Q图严重偏离直线,存在极端离群值 | 稳健回归方法:减少离群值影响的损失函数(如Huber损失) | 估计效率可能低于最小二乘法,但更稳定 |

| 嵌套/层次数据 | 数据来自不同批次、酶制剂或实验日期 | 非线性混合效应模型:区分固定效应(平均动力学)与随机效应(变异来源) | 计算复杂,需要专业软件(如R的nlme包) |

| 模型结构不确定性 | 多个竞争模型拟合度相近 | 模型平均:基于信息准则(如AICc)对多个模型进行加权平均预测 | 侧重于预测而非单一模型解释 |

研究试剂与关键工具

表3:酶动力学参数估计研究的关键试剂与工具

| 类别 | 名称/示例 | 功能描述 | 在验证假设中的作用 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 统计分析软件 | MATLAB Statistics & Machine Learning Toolbox | 提供nlinfit、lsqcurvefit等非线性拟合函数,以及残差诊断工具 [25]。 |

核心拟合与诊断平台。可编程实现完整的诊断流程。 |

| 专业统计环境 | R with nls, nlme, car packages |

提供灵活的非线性建模、混合效应模型扩展及全面的回归诊断功能。 | 实现高级建模方案(如GLS、混合模型)和统计检验。 |

| 动力学分析套件 | GraphPad Prism | 提供直观的酶动力学模型拟合界面和基础的残差图。 | 快速初步拟合和可视化,适合实验科学家快速验证。 |

| 数据模拟工具 | 自定义脚本(Python/R/MATLAB) | 根据预设参数和误差结构生成模拟动力学数据。 | 进行方法学验证,理解不同违反假设对估计结果的影响。 |

| 基准测试数据集 | 具有重复测量和已知干扰的公共数据集 | 提供现实世界中有挑战性的数据,用于测试和比较分析流程的稳健性。 | 评估诊断方案和修正方法在真实复杂情况下的有效性。 |

综合工作流与决策路径

以下流程图描述了将上述协议整合到酶动力学参数估计研究中的完整工作流和决策路径。

酶动力学数据分析与诊断工作流

以下决策图提供了一个基于残差图模式的快速诊断路径。

基于残差模式的诊断与行动路径

Advanced NLLS Workflows: From Progress Curves to Novel Inhibition Analysis

The accurate determination of the Michaelis constant (Kₘ) and the maximum reaction velocity (Vₘₐₓ) from initial velocity data constitutes a foundational task in enzymology, with direct implications for drug discovery, diagnostic assay development, and systems biology modeling [20]. Within the broader thesis of nonlinear least squares (NLLS) enzyme parameter estimation research, this workflow represents the critical interface between experimental data collection and robust parameter inference. The canonical Michaelis-Menten equation (v = (Vₘₐₓ × [S])/(Kₘ + [S])) provides a nonlinear relationship between substrate concentration ([S]) and initial velocity (v), making its fitting a classic problem in NLLS optimization [9]. While traditional linearization methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee plots) persist in educational settings, contemporary research unequivocally demonstrates the superiority of direct nonlinear regression for yielding accurate, unbiased parameter estimates, as these methods properly weight data and avoid the statistical distortions inherent in transformed plots [20]. This document details a standardized, rigorous workflow for obtaining Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ, emphasizing protocols that ensure reproducibility, validate model assumptions, and integrate with advanced computational tools for NLLS estimation.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Methodologies

The estimation of Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ is predicated on the validity of the Michaelis-Menten kinetic model, which describes a single-substrate, irreversible, enzyme-catalyzed reaction under steady-state assumptions [9]. The core model is defined by two parameters: Vₘₐₓ, the theoretical maximum rate achieved when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate, and Kₘ, the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vₘₐₓ [20]. A critical, often overlooked, validity condition for applying the standard model is that the total enzyme concentration ([E]ₜ) must be significantly lower than the sum of Kₘ and the initial substrate concentration ([S]₀) [27]. Violation of this condition, common in in vivo contexts or high-concentration assays, necessitates the use of more general models like the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) [27].

The choice of estimation methodology profoundly impacts the accuracy and precision of the derived parameters. A comparative simulation study evaluating five common methods revealed clear hierarchies in performance [20].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ Estimation Methods from Simulation Data [20]

| Estimation Method | Description | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | Linear fit of 1/v vs. 1/[S]. | Simple visualization. | Severely distorts error structure; poor accuracy/precision. | Educational demonstration only. |

| Eadie-Hofstee (EH) | Linear fit of v vs. v/[S]. | Less error distortion than LB. | Still prone to error bias; suboptimal precision. | Legacy data analysis. |

| Nonlinear Regression (NL) | Direct NLLS fit of v vs. [S] to the M-M equation. | Correct error weighting; high accuracy. | Requires initial parameter guesses. | Standard in vitro analysis. |

| Averaged Point Nonlinear (ND) | NLLS fit using velocities from adjacent time points. | Uses more time-course data. | Sensitive to non-ideal early time points. | When initial rate linear phase is ambiguous. |

| Full Time-Course Nonlinear (NM) | NLLS fit of the integrated rate equation to [S]-vs-time data. | Most accurate & precise; uses all data. | Computationally intensive; requires robust solver. | High-value data; validating other methods. |

The simulation concluded that nonlinear methods (NL and NM) provided the most accurate and precise parameter estimates, with the NM (full time-course) method being superior, especially under realistic combined (additive + proportional) error models [20]. This supports the core thesis that direct NLLS fitting, avoiding linear transformations, is essential for rigorous parameter estimation.

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting the appropriate estimation model based on experimental conditions.

Standard Experimental Protocol for Initial Velocity Measurement

This protocol details the generation of a robust initial velocity dataset suitable for NLLS analysis.

Reagents and Instrumentation

- Enzyme Solution: Purified enzyme at a concentration accurately determined (e.g., via absorbance at 280 nm). Prepare in an appropriate reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl₂) to maintain stability and activity. Aliquot and store at recommended temperatures [28].

- Substrate Stock Solution: High-purity substrate prepared in reaction buffer or a compatible solvent (e.g., DMSO < 1% final). Concentration must be verified (e.g., spectrophotometrically).

- Positive/Negative Controls: A known inhibitor for a negative control; a reaction with all components for a positive control.

- Instrumentation: A plate reader or spectrophotometer capable of kinetic measurements (continuous absorbance/fluorescence) at the relevant wavelength, maintained at a constant temperature (e.g., 30°C).

Assay Procedure

- Substrate Titration Series: Prepare 8-12 substrate concentrations in reaction buffer, typically spanning a range from 0.2× to 5× the estimated Kₘ. A logarithmic spacing is often more informative than linear. Include a zero-substrate (blank) control [27].

- Reaction Initiation: In a multiwell plate or cuvette, first add the appropriate volume of substrate solution and buffer to achieve the final desired concentration in the working volume (e.g., 100 µL). Pre-incubate at the assay temperature for 5 minutes.

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the reaction by rapid addition of a small volume of enzyme solution (e.g., 5 µL of 20x concentrated stock) to achieve the final working concentration. Mix immediately and thoroughly. Begin continuous measurement of the signal (e.g., absorbance at 340 nm for NADH) immediately. Record data points every 5-10 seconds for a period covering the initial linear phase (typically 5-10% of substrate conversion) [29].

- Replicates: Perform each substrate concentration in triplicate to assess technical variability.

Initial Rate (Velocity) Calculation

For each substrate concentration trace:

- Plot signal (y) vs. time (t). Visually inspect for a linear initial period.

- Using analysis software (e.g., ICEKAT, GraphPad Prism), fit a straight line to the early, linear portion of the curve. The slope of this line (Δy/Δt) is proportional to the initial velocity.

- Background Correction: Subtract the slope (rate) of the zero-substrate control from all sample slopes.

- Unit Conversion: Convert the slope (in signal units/time) to velocity (v, in concentration/time, e.g., µM/s) using the molar extinction coefficient (ε) and path length (l): v = (Slope) / (ε × l).

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit for Initial Velocity Experiments

| Category | Item/Reagent | Specification/Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | Purified Target Enzyme | Catalytic agent; concentration must be precisely known. | Aliquot to avoid freeze-thaw cycles; verify activity with a reference substrate. |

| Substrate | High-Purity Chemical Substrate | Reactant converted to measurable product. | Solubility and stability in assay buffer are key; use fresh stock solutions. |

| Buffer System | e.g., Tris-HCl, HEPES, Phosphate | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength. | Include necessary cofactors (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) or stabilizing agents (BSA, DTT). |

| Detection Reagent | Chromogenic/Fluorogenic Probe (e.g., NADH, pNPP) | Generates a measurable signal proportional to product formation. | Match ε and λₘₐₓ to instrument capabilities; ensure signal is in linear range. |

| Software | ICEKAT (Web Tool) [28], GraphPad Prism, R with nls() |

Data fitting, initial rate calculation, and NLLS regression. | ICEKAT is specialized for interactive, semi-automated initial rate determination [29]. |

| Hardware | Temperature-Controlled Microplate Reader | Provides continuous kinetic measurement in a high-throughput format. | Ensure temperature equilibration before starting; calibrate path length if needed. |

Computational Protocol for Nonlinear Least Squares Estimation

This protocol outlines the steps for fitting the initial velocity ([S]) dataset to the Michaelis-Menten model using NLLS.

Data Preparation and Software Setup

- Format data into a three-column table:

[Substrate] (µM),Velocity (µM/s),Error (µM/s). The error column can contain standard deviations from replicates or be estimated. - Choose software: GraphPad Prism (commercial, GUI), R (open source, scriptable), or Python/SciPy (open source, scriptable).

Model Fitting Procedure (using R as an example)

Define the Model Function:

Provide Initial Parameter Estimates: Visually estimate from the v vs. [S] plot. Vₘₐₓ ≈ plateau velocity. Kₘ ≈ [S] at half the plateau.

Perform NLLS Fit using the

nls()function:Extract and Report Results:

Model Diagnostics and Validation

- Visual Inspection: Plot the observed data points with the fitted model curve overlaid. Assess goodness-of-fit.

- Residual Analysis: Plot residuals (observed - predicted) vs. [S] and vs. predicted velocity. The residuals should be randomly scattered around zero without systematic patterns, validating the homoscedasticity assumption [20].

- Parameter Uncertainty: Report parameter estimates with 95% confidence intervals (from

confintin R), not just standard errors. Confidence intervals derived from profile likelihood are more reliable than those from simple linear approximation [30]. - Advanced Validation (Bootstrapping): For small datasets, use a nonparametric bootstrap (resampling residuals with replacement) to generate robust empirical confidence intervals for Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ.

Advanced Protocol: Bayesian Inference and the tQSSA Model

When the standard model's validity condition is questionable ([E]ₜ is not negligible), or when prior knowledge exists, a Bayesian framework with the tQSSA model is superior [27].

The tQSSA Model

The tQSSA model is more accurate than the standard model under general conditions, especially when enzyme concentration is high [27]. The differential form is:

dP/dt = k_cat * ( [E]ₜ + Kₘ + [S]ₜ - P - sqrt( ([E]ₜ + Kₘ + [S]ₜ - P)² - 4[E]ₜ([S]ₜ - P) ) ) / 2

where P is product concentration, and [S]ₜ is total substrate. Fitting this model directly to progress curve data ([P] vs. time) yields estimates for kcat and Kₘ (Vₘₐₓ = kcat × [E]ₜ).

Bayesian Estimation Workflow

- Define the Probability Model: Specify the likelihood function (e.g., normal distribution of data around the tQSSA model prediction) and prior distributions for parameters (e.g., weakly informative log-normal priors for k_cat and Kₘ) [27].

- Sample from the Posterior Distribution: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling (e.g., with Stan, PyMC3, or JAGS) to obtain the joint posterior distribution of k_cat and Kₘ.

- Analyze Output: The posterior distributions provide full parameter estimates (e.g., median), credible intervals (e.g., 95% highest posterior density interval), and reveal parameter correlations.

Diagram 2: The Bayesian inference process for kinetic parameter estimation, incorporating prior knowledge via Bayes' Theorem.

Optimal Experimental Design

A key advantage of the Bayesian/tQSSA approach is the facilitation of optimal experimental design. By analyzing preliminary posterior distributions, one can identify which new experimental condition (e.g., a specific [S]₀ or [E]ₜ) would most effectively reduce parameter uncertainty [27].

- Run a preliminary experiment with a single condition.

- Compute the posterior. If the posterior is wide (uncertain), use it to simulate data from proposed new conditions.

- Select the condition that maximizes the expected reduction in posterior variance (e.g., maximizes information gain). This allows precise estimation with minimal experimental effort.

Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Reporting Standards

Key Output Parameters and Their Meaning

- Vₘₐₓ: A measure of the total functional enzyme concentration and its intrinsic turnover rate. Report as mean ± 95% CI (e.g., 120 ± 15 µM/s).

- Kₘ: An inverse measure of the enzyme's apparent affinity for the substrate under steady-state conditions. Report as mean ± 95% CI (e.g., 25 ± 5 µM).

- k_cat (= Vₘₐₓ / [E]ₜ): The turnover number, representing the maximum number of substrate molecules converted per enzyme active site per second.

- k_cat/Kₘ: The specificity constant, a measure of catalytic efficiency. This is the apparent second-order rate constant for the reaction at low substrate concentrations [9].

Table 3: Example Kinetic Parameters for Various Enzymes [9]

| Enzyme | Kₘ (M) | k_cat (s⁻¹) | k_cat/Kₘ (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Catalytic Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 | Low |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ | Moderate |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ | High |

| Carbonic Anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ | Very High |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ | Diffusion-Limited |

Comprehensive Reporting Checklist

For reproducibility, report:

- Experimental Conditions: Buffer (pH, ionic strength), temperature, [E]ₜ for each assay.

- Raw Data Access: State how raw kinetic traces are available.

- Initial Rate Determination: Specify the method (e.g., "linear fit of first 90s using ICEKAT's Maximize Slope Magnitude mode") [29].

- Fitting Procedure: Software, algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt), weighting scheme, initial guesses.

- Final Estimates: Vₘₐₓ, Kₘ, kcat, and kcat/Kₘ with confidence/credible intervals.

- Goodness-of-Fit Metrics: R² (for nonlinear fit), sum of squares, and visual assessment of residual plots.

- Model Assumptions: Explicitly state the validation of the steady-state condition ([E]ₜ << Kₘ + [S]₀) or justification for using the tQSSA model.

The standard workflow for estimating Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ has evolved from graphical linearizations to computationally-driven nonlinear least squares and Bayesian inference methods. This evolution directly reflects the core themes of the broader thesis on NLLS enzyme parameter estimation: the necessity of using statistically appropriate models that respect data structure, the power of computational tools to extract robust parameters from complex nonlinear equations, and the importance of quantifying uncertainty through confidence intervals or posterior distributions. The adoption of the protocols detailed herein—particularly the use of direct NLLS fitting of untransformed data, diagnostic validation, and the consideration of advanced models like tQSSA for non-ideal conditions—ensures that derived kinetic parameters are reliable, reproducible, and form a solid foundation for downstream applications in drug development, enzyme engineering, and systems biology modeling.

Diagram 3: The complete workflow integrated into the broader nonlinear least squares parameter estimation research thesis.

The rigorous estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters constitutes a cornerstone of quantitative biochemistry, metabolic modeling, and mechanistic drug discovery. Within the broader thesis on nonlinear least squares enzyme parameter estimation, progress curve analysis emerges as a superior, information-rich alternative to traditional initial rate methods. While classical Michaelis-Menten analysis derived from initial velocity measurements has been the standard for over a century [31], it inherently discards the vast majority of data collected during a time-course experiment. In contrast, progress curve analysis utilizes the complete temporal dataset of product formation or substrate depletion, enabling more robust parameter estimation from fewer experiments and providing a direct window into complex enzyme kinetics [32] [31].

This approach is particularly vital when investigating non-classical kinetic behaviors such as hysteresis, burst kinetics, or time-dependent inhibition, which are often obscured in initial rate studies [32]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the ability to accurately fit progress curves using nonlinear least squares regression is not merely a technical skill but a fundamental competency for elucidating mechanism of action, validating targets, and deriving precise inhibitory constants (Ki) for lead compounds. The following application notes and protocols are designed to integrate the theoretical underpinnings of progress curve analysis with practical, executable methodologies, framed within the advanced context of modern parameter estimation research.

Theoretical Foundations: From Michaelis-Menten to Total Quasi-Steady-State Analysis

The canonical framework for analyzing enzyme kinetics is the Michaelis-Menten equation, derived under the standard quasi-steady-state assumption (sQSSA). This model describes the velocity (v) of a reaction as a function of substrate concentration [S], the maximum velocity (Vmax), and the Michaelis constant (Km):

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S]) [33].

The sQSSA is valid only under the condition that the total enzyme concentration [E]T is significantly lower than the sum of [S] and Km ([E]T << Km + [S]) [31]. While often applicable for in vitro assays with diluted enzyme, this condition frequently fails in in vivo contexts or in concentrated assay systems, leading to significant bias in parameter estimates [31].

To overcome this limitation, the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) provides a more robust analytical framework. The tQSSA model, while mathematically more complex, remains accurate over a much wider range of enzyme and substrate concentrations, including scenarios where [E]T is comparable to or even exceeds [S] [31]. Its validity condition is generally satisfied, making it the preferred model for progress curve analysis when applying nonlinear least squares fitting, as it prevents systematic error in estimated kcat and Km values.

A critical consideration is the identification of time-dependent kinetic complexities. Full progress curve analysis can reveal atypical behaviors such as:

- Hysteresis (Lag/Burst Phase): A slow transient phase before a steady-state rate is established, indicating a slow conformational change in the enzyme [32].

- Product Inhibition: Accumulating product reversibly binding to the enzyme and slowing the reaction as the curve progresses [33] [32].

- Enzyme Instability: A gradual loss of activity over time, leading to progress curves that plateau below the expected endpoint [33].

Fitting the full curve with appropriate models (e.g., integrated rate equations incorporating product inhibition) is essential to disentangle these effects and obtain true intrinsic kinetic parameters [32] [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Kinetic Analysis Frameworks for Progress Curve Fitting

| Framework | Core Model | Validity Condition | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard QSSA (sQSSA) | Michaelis-Menten Equation | [E]T << Km + [S] [31] |

Simplicity; wide historical usage. | Biased estimates when enzyme concentration is high [31]. |

| Total QSSA (tQSSA) | Total QSSA Equation [31] | Generally valid for a wider range of conditions [31]. | Accurate even when [E]T is high; superior for in vivo extrapolation. |

More complex equation for non-linear regression. |

| Integrated Rate Law (with Product Inhibition) | [P] = f(t, Vmax, Km, Ki) |

Requires accurate initial substrate concentration. | Directly accounts for curvature from product inhibition. | Requires knowledge/estimation of Ki; more parameters to fit. |

Comprehensive Protocol for Progress Curve Assay Development

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a robust, continuous assay suitable for progress curve analysis, with an emphasis on generating data for nonlinear least squares parameter estimation.

Stage 1: Reagent Preparation and Instrument Calibration

1.1 Enzyme Solution:

- Source & Purity: Use enzyme of known amino acid sequence and high purity. Document source, specific activity (units/mg), and lot number [33]. Determine protein concentration via a reliable method (e.g., A280, BCA assay).

- Specific Activity Definition: Define one unit (U) of enzyme as the amount that catalyzes the conversion of 1 μmol (or 1 nmol) of substrate per minute under defined standard conditions [34]. Consistently use nmol/min/mg for specific activity to avoid ambiguity [34].

- Stability & Storage: Conduct stability tests to define optimal storage buffers and on-bench stability. Aliquot and store to avoid freeze-thaw cycles [33].

1.2 Substrate & Cofactor Solutions:

- Selection: Use the natural substrate or a validated surrogate (e.g., fluorogenic/ chromogenic peptide) [33]. For kinases, determine Km for both the peptide substrate and ATP [33].

- Concentration Range: Prepare a stock solution at the highest required concentration (typically >10x Km) in assay buffer. Serial dilute to generate a range spanning 0.2–5.0 × Km (at least 8 concentrations) [33]. The final concentration must be known with high accuracy.

- Cofactors/Additives: Identify and include all essential cofactors (e.g., Mg2+ for kinases), metal ions, or reducing agents as per the enzyme's requirement [33].

1.3 Assay Buffer Optimization:

- Systematically optimize pH, ionic strength, and buffer composition in preliminary experiments to maximize activity and stability [33]. A standard buffer (e.g., 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.01% Triton X-100) is a common starting point.

1.4 Detection System Linearity Validation:

- Critical Step: Before any enzyme assay, validate the linear dynamic range of the detection instrument (plate reader, spectrophotometer). Perform a standard curve using pure product (or a surrogate chromophore/fluorophore).

- Procedure: Measure signal (absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence) across a range of product concentrations that spans and exceeds the expected yield in the assay.

- Acceptance Criterion: The signal must be linear (R² > 0.99) over the entire range of product concentrations that will be generated. Enzyme reactions must be confined to this linear range [33] [34].

Stage 2: Defining Initial Velocity Conditions and Linear Range

Objective: To establish enzyme concentration and assay time where the progress curve is linear (initial velocity conditions), defined as less than 10% substrate depletion [33].

2.1 Time-Course at Varied Enzyme Concentrations:

- Setup: In a 96- or 384-well plate, combine assay buffer, fixed substrate concentration (at or below estimated Km), and varying concentrations of enzyme (e.g., 0.5x, 1x, 2x of a guessed concentration). Perform in triplicate. Use a final volume appropriate for the detection method (e.g., 50-100 μL) [34].

- Execution: Initiate the reaction by adding enzyme (or substrate) using a repeat pipettor or automated dispenser. Immediately place the plate in a pre-warmed reader (e.g., 25°C or 30°C) and record signal every 10-30 seconds for a duration 3-5 times the expected linear period.

- Analysis: Plot product formed (calculated from signal using the standard curve) versus time for each enzyme concentration.

- Interpretation: Identify the enzyme dilution that yields a linear progress curve for the desired assay duration (e.g., 15-60 minutes). Higher enzyme concentrations may cause early substrate depletion and curvature; lower concentrations provide longer linearity [33] [34]. Select the highest enzyme concentration that maintains linearity for your chosen assay time.

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for Progress Curve Assays

| Parameter | Recommended Specification | Rationale & Consequence of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Depletion | < 10-15% of initial [S] [33] [34] | Maintains pseudo-first-order conditions; >15% depletion introduces significant curvature from substrate loss. |

| Assay Time | 15 – 60 minutes [34] | Short times (<2 min) increase timing error; long times risk enzyme inactivation or non-linearity. |

| Enzyme Concentration | Adjusted to meet <10% depletion criterion [33] | Too high: non-linear curves, wasted reagent. Too low: poor signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Signal Intensity | Mid-range of detector's linear dynamic range [33] [34] | Low signal: poor precision. Signal at detector saturation: invalid data. |

| Replicates | Minimum n=3 (technical) | Required for estimating error in velocity and fitted parameters. |

Stage 3: Full Progress Curve Experiment for Km and Vmax Estimation

Objective: To collect high-quality time-course data at multiple substrate concentrations for global nonlinear regression fitting.

3.1 Experimental Design:

- Prepare reactions with the optimized enzyme concentration (from Stage 2) and a series of substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5 × Km). Include a zero-substrate control for background subtraction.

- For each [S], monitor the reaction continuously until the curve clearly approaches a plateau (substrate exhaustion) or for a predetermined maximum time.

3.2 Data Processing Workflow:

- Background Subtraction: Subtract the average signal from the zero-substrate control from all time-course data.

- Conversion to Concentration: Convert raw signal (RFU, absorbance) to product concentration [P] using the standard curve.

- Data Assembly: For each [S], the dataset is a list of time (t) and [P] pairs.

3.3 Fitting with Nonlinear Least Squares:

- Model Selection: Choose an appropriate model. For simple Michaelis-Menten kinetics under sQSSA, use the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation. For greater generality, use the tQSSA model [31]. To account for product inhibition, use an integrated equation that includes a Ki term.

- Software: Use specialized software (e.g., COPASI [35], Prism, KinTek Explorer, or custom scripts in R/Python with libraries like

lmfitorSciPy). - Fitting Procedure: Perform a global fit, where all progress curves (for different [S]) are fitted simultaneously to a shared set of parameters (Km, Vmax, and optionally Ki). This utilizes all data points and yields the most precise and accurate estimates [31].

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate the fit by inspecting residuals (which should be randomly distributed), confidence intervals of parameters, and R² values.

Flowchart: Progress Curve Analysis & Fitting Workflow.

Advanced Application: Diagnosing Time-Dependent Kinetic Complexity

Progress curve analysis is uniquely powerful for detecting deviations from simple Michaelis-Menten kinetics [32].

4.1 Identifying Hysteresis (Lag or Burst):

- Visual Inspection: Plot the early time points. A lag phase shows an upward-curving trace (velocity increases). A burst phase shows a rapid initial product formation followed by a slower linear phase (velocity decreases) [32].

- Derivative Analysis: Plot the instantaneous velocity (d[P]/dt) vs. time. For a hysteretic enzyme, this derivative will not be constant initially but will change (increase for lag, decrease for burst) towards a steady-state value [32].

- Fitting: Fit data to a hysteretic model equation:

[P] = Vss*t - (Vss - Vi)*(1 - exp(-k*t))/k, where Vi is initial velocity, Vss is steady-state velocity, and k is the isomerization rate constant [32].

4.2 Diagnosing Product Inhibition:

- Global fitting of progress curves to an integrated equation that includes a Ki parameter. A significant improvement in fit quality (e.g., reduced sum-of-squares) and a well-constrained Ki value indicate product inhibition.

- Test directly by adding known product to the start of the reaction and observing a decreased initial rate.

4.3 Assessing Enzyme Inactivation:

- Compare the final plateau (endpoint) of progress curves at different enzyme concentrations. If the plateaus are not proportional to [E] (e.g., a 2x [E] does not yield 2x product), time-dependent enzyme inactivation is likely occurring [33].

Diagram: Enzyme Kinetic Pathways Showing Complexities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Progress Curve Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification & Function | Critical Notes for Assay Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | High specific activity; known concentration (mg/mL). Source and lot documented [33]. | Low specific activity indicates impurities or denaturation, affecting kinetic parameter accuracy [34]. |

| Substrate(s) | >95% chemical purity; solubility in assay buffer verified. Natural or validated surrogate substrate [33]. | Impurities can act as inhibitors or alternative substrates. Accurate molar concentration is vital for Km. |

| Cofactors | Essential ions (Mg2+, Mn2+), nucleotides (ATP, NADH), or coenzymes. | Concentration must be saturating and non-inhibitory. Determine required concentration separately. |

| Assay Buffer | Optimized for pH, ionic strength, and stability. Includes necessary additives (e.g., DTT, BSA) [33]. | Poor buffer choice can reduce activity by >90%, leading to underestimation of kcat. |

| Product Standard | Pure compound identical to the reaction product. | Essential for generating the standard curve to convert signal to [P] and validate detector linearity [33]. |

| Reference Inhibitor | Well-characterized inhibitor (e.g., a published compound with known Ki). | Serves as a positive control for assay sensitivity and validation of the fitting protocol. |

| Microplates & Seals | Optically clear plates compatible with detection mode (UV-transparent, low-fluorescence). Non-binding surfaces for low [E]. | Plate type can affect signal intensity and well-to-well consistency. |

| Liquid Handling | Precision pipettes or automated dispensers for reagent addition. | Manual addition of enzyme to start reaction is a major source of timing error; use a multichannel or dispenser. |

Abstract The precise estimation of enzyme inhibition constants (Ki) is fundamental to drug development, safety assessment, and basic enzymology. Traditional methods require resource-intensive experimental designs involving multiple inhibitor and substrate concentrations. This article introduces and details the 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach), a novel paradigm within the broader field of nonlinear least squares enzyme parameter estimation. By employing error landscape analysis and incorporating the harmonic mean relationship between IC50 and Ki into the fitting process, the 50-BOA demonstrates that accurate and precise estimation of inhibition constants for competitive, uncompetitive, and mixed inhibition is achievable using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50. This methodology reduces the required number of experiments by over 75% while improving precision, offering a transformative, efficiency-driven protocol for researchers and drug development professionals [36] [37].

The estimation of kinetic parameters—the Michaelis constant (Km), maximum velocity (Vmax), and inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu)—is a cornerstone of quantitative enzymology with direct implications for drug discovery and safety [38]. Inhibition constants, representing the dissociation constants for inhibitor binding to the enzyme or enzyme-substrate complex, are particularly critical. They quantify inhibitor potency and reveal the mechanism of action (competitive, uncompetitive, or mixed), information essential for predicting clinical drug-drug interactions and guiding dose adjustments [36] [37].

The prevailing methodology for Ki determination relies on fitting the relevant kinetic model to initial velocity data collected from a matrix of substrate ([S]) and inhibitor ([I]) concentrations, a canonical approach used in tens of thousands of studies [37]. This process is intrinsically a problem of nonlinear least squares parameter estimation. Historically, linear transformations like Lineweaver-Burk plots were used, but these distort error structures and can yield biased estimates [20] [39]. Modern practice employs direct nonlinear regression, yet the experimental design guiding this fitting remains largely empirical and inefficient [36].

A significant challenge arises in the common scenario where the inhibition mechanism is unknown a priori. The general mixed inhibition model, which requires estimating two inhibition constants (Kic, Kiu), must be applied [37]. The canonical experimental design, however, was not rigorously optimized for this task, often leading to imprecise estimates, ambiguous mechanism identification, and inconsistent results across studies [36]. Furthermore, the resource burden of testing multiple inhibitor concentrations is substantial.

This article situates the 50-BOA within the ongoing evolution of nonlinear parameter estimation strategies. It moves beyond optimizing the fitting algorithm (e.g., using genetic algorithms or particle swarm optimization for nonlinear regression [39]) to fundamentally re-engineering the experimental design and objective function. By analyzing the mathematical "error landscape" of the estimation problem, the 50-BOA identifies an optimal, minimal data requirement and incorporates prior knowledge (the IC50) as a regularization constraint, thereby achieving a paradigm shift toward radical efficiency and enhanced reliability in Ki estimation [36] [40].

Theoretical Foundation and the 50-BOA Protocol

The Canonical Approach: A Baseline for Comparison

The canonical protocol serves as a baseline for understanding the 50-BOA's advantages.

- Step 1 – IC50 Determination: The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) is estimated from a dose-response curve using a single substrate concentration, typically at or near the Km [36] [38].

- Step 2 – Experimental Matrix Design: Initial velocity (V0) is measured for a grid of concentrations: typically [S] at 0.2Km, Km, and 5Km; and [I] at 0, (1/3)IC50, IC50, and 3IC50. This results in 12 distinct reaction conditions [36] [37].

- Step 3 – Nonlinear Regression: The general velocity equation for mixed inhibition (Eq. 1) is fitted to the 12 (V0, [S], [I]) data points using nonlinear least squares to estimate parameters Vmax, Km, Kic, and Kiu [37].

Equation 1: General Mixed Inhibition Model

V0 = (Vmax * [S]) / ( Km * (1 + [I]/Kic) + [S] * (1 + [I]/Kiu) )

Table 1: Canonical vs. 50-BOA Experimental Protocol

| Aspect | Canonical Approach | 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Empirical design; fit model to multi-concentration grid. | Error landscape optimization; use IC50 as a fitting constraint [36]. |

| Key Inhibitor Conc. | Multiple, including values below IC50 (e.g., 0, IC50/3) [37]. | A single concentration greater than or equal to IC50 [36] [37]. |

| Typical [#] of [I] tested | 4 | 1 |

| Typical Total Experiments | 12 (3[S] x 4[I]) | 3 (3[S] x 1[I]) |

| Data Requirement for Fit | All data points from the matrix. | Velocity at one high [I] across varying [S]; IC50 value. |

| Error Landscape | Broad, shallow minimum with sub-optimal [I], leading to poor identifiability of Kic and Kiu [36]. | Sharp, well-defined global minimum, enabling precise estimation [36]. |

The 50-BOA Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

The 50-BOA protocol is a streamlined, principled alternative.

Part A: Preliminary Experiment

- Determine Km and Vmax: Characterize the enzyme kinetics in the absence of inhibitor using standard nonlinear fitting of the Michaelis-Menten equation to initial velocity data across a range of substrate concentrations [38] [20].

- Determine IC50: Using a substrate concentration near the Km, perform a dose-response experiment with the inhibitor. Fit a sigmoidal curve to obtain the IC50 value [36] [38].

Part B: Optimal Initial Velocity Assay

- Select Inhibitor Concentration: Choose a single inhibitor concentration ([I]opt) ≥ IC50. The analysis of error landscapes demonstrates that data from inhibitor concentrations significantly below the IC50 provide little information and can broaden confidence intervals, whereas a single point at or above IC50 is sufficient for precise estimation [36].

- Select Substrate Concentrations: Perform reactions at this single [I]opt across at least two distinct substrate concentrations, optimally spanning a range within (0.2Km, 5Km) [40]. This is required to resolve the effects on Km and Vmax.

- Measure Initial Velocities: Conduct the enzymatic assays and measure the initial reaction velocity (V0) for each condition.

Part C: Computational Analysis with 50-BOA Package

- Prepare Data File: Format the data as required by the 50-BOA software package [40].

- Row 1: Input the previously determined Vmax, Km, IC50, and the substrate concentration used for the IC50 assay.

- Subsequent Rows: List each experimental condition: Substrate concentration ([S]), Inhibitor concentration ([I]), Measured Initial Velocity (V0).

- Execute the 50-BOA Algorithm: Run the

Error_Landscapefunction. The software [40]:- Checks Data Sufficiency: Verifies that [I] ≥ IC50 and that multiple [S] are used.

- Performs Regularized Fitting: Fits Equation 1 using a nonlinear least squares objective function that is regularized by the harmonic mean relationship between IC50, Kic, and Kiu. This key step incorporates the known IC50 as a constraint, guiding the fit to a physiologically plausible and precise solution [36].

- Generates Output: Returns the estimated Kic and Kiu with 95% confidence intervals, the inhibition type (based on the ratio Kic/Kiu), and a visual heatmap of the error landscape.

Visual Workflow: The 50-BOA Process

Diagram 1: A flowchart of the 50-BOA protocol, from preliminary characterization to computational analysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Notes for 50-BOA |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biological catalyst of interest. | Must be stable and active under assay conditions. |

| Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme. | Concentration range should span below and above Km. |

| Inhibitor | The test compound for inhibition analysis. | Stock solutions prepared at high concentration for accurate dilution to [I]opt. |