Mastering the Craft: Essential Guidelines for Reproducible and FAIR Enzyme Kinetics Data Reporting

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the best practices for reporting enzyme kinetics data, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mastering the Craft: Essential Guidelines for Reproducible and FAIR Enzyme Kinetics Data Reporting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the best practices for reporting enzyme kinetics data, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of reproducibility and the FAIR data principles, outlining the critical metadata required as per the STRENDA guidelines to ensure experimental replicability [citation:1]. The methodological core details advanced techniques for data acquisition, including progress curve analysis and the use of standardized tools for robust parameter estimation [citation:6][citation:7]. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common experimental and analytical pitfalls, offering strategies for optimization. Finally, the guide explores the vital role of rigorous data reporting in validation, its impact on building public datasets and training predictive AI models, and its implications for accelerating biomedical discovery and drug development [citation:2][citation:4][citation:5].

The Cornerstones of Reproducibility: Mastering FAIR Data Principles and Essential Reporting Standards

Abstract This technical guide examines the foundational role of rigorous data practices in enzymology and drug development. Through the lens of contemporary research, such as advanced photo-biocatalytic systems [1], and established analytical methods, it delineates how systematic attention to data quality at every experimental phase—from design to presentation—directly enables reproducibility and accelerates scientific progress. The document provides actionable protocols, visualization standards, and tooling recommendations to empower researchers in implementing these best practices.

The Centrality of Data Quality in Modern Enzyme Kinetics

In fields like enzymology and drug discovery, scientific progress is not merely a function of novel findings but of credible, reproducible findings. The increasing complexity of experimental systems, exemplified by hybrid photo-enzyme catalysis for remote C–H bond functionalization [1], places unprecedented demands on data integrity. In these systems, where visible light, enzyme mutants, and radical intermediates interact, poor data quality can obscure mechanistic insights and stall development.

Data quality is a multidimensional construct critical to reproducible science. It is defined by several key attributes applied to primary data (e.g., initial velocity measurements) and derived parameters (e.g., Km, Vmax):

- Accuracy: Proximity of measured values to the true value. Requires calibrated instruments and appropriate controls.

- Precision (Repeatability & Reproducibility): The closeness of agreement between independent measurements under stipulated conditions. Distinguishes between intra-lab (repeatability) and inter-lab (reproducibility) consistency.

- Completeness: The extent to which all required data and metadata (e.g., buffer conditions, enzyme lot, temperature) are recorded and available.

- Consistency: Adherence to uniform formats, units, and analytical methods across related datasets and over time.

The failure to uphold these dimensions is a primary contributor to the reproducibility crisis, manifesting as wasted resources, retracted publications, and delayed therapeutic pipelines. For enzyme kinetics, a cornerstone of mechanistic and screening studies, this crisis underscores a non-negotiable truth: high-quality data is the substrate from which reliable scientific knowledge is catalyzed.

Quantifying the Impact: Data Quality and Reproducibility Metrics

The relationship between data quality, reproducibility, and progress can be quantified. The following table summarizes key metrics from recent research and analysis, highlighting benchmarks for high-quality outcomes.

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics Linking Data Practices to Research Outcomes

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Typical Benchmark for High Quality | Observed Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Replication | Replicate Correlation (R²) | > 0.98 for technical replicates [2] | Enables precise curve fitting and reliable parameter estimation. |

| P-value from Replicate Test | > 0.05 (non-significant) [2] | Indicates curve fit adequately explains data scatter; a significant p-value (<0.05) suggests model misspecification. | |

| Analytical Output | Enantiomeric Ratio (e.r.) | Up to 99.5:0.5 [1] | Defines product purity and catalytic selectivity; directly impacts the utility of a synthetic enzyme. |

| Standard Error of Km/Vmax | < 10-20% of parameter value [2] | Reflects confidence in kinetic constants; lower error enables robust comparative studies. | |

| Process Integrity | Z'-factor for HTS Assays | > 0.5 [3] | Quantifies assay robustness and suitability for high-throughput screening in drug discovery. |

Foundational Experimental Protocols for Robust Enzyme Kinetics Data

The generation of high-quality data begins with meticulously planned and executed experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for two critical aspects: initial reaction rate determination and continuous assay data processing.

3.1 Protocol for Determining Initial Velocity (v0) with Replication This protocol is essential for generating the primary data for Michaelis-Menten analysis.

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: Prepare a master mix containing all reaction components except the substrate. This includes buffer, cofactors, enzyme (at a concentration that yields linear progress curves), and any essential salts. Maintain the mix on ice.

- Substrate Dilution Series: Prepare serial dilutions of the substrate across a concentration range typically spanning 0.2-5.0 x Km. Use the same buffer as the master mix.

- Initiation and Measurement: For each substrate concentration, aliquot the master mix into a cuvette or microplate well. Initiate the reaction by adding the substrate. Immediately begin monitoring the product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence) over time using a plate reader or spectrophotometer.

- Replication Strategy: Perform each substrate concentration in at least triplicate (n≥3). Replicates should be true biological or technical replicates, not mere repeated measurements of the same sample [2].

- Initial Rate Calculation: For each progress curve, identify the linear phase. The slope of this linear region, typically determined by linear regression over the first 5-10% of the reaction, is the initial velocity (v0).

3.2 Protocol for Data Processing and Outlier Analysis Raw data must be processed consistently to identify and address anomalies before kinetic analysis.

- Background Subtraction: Subtract the average signal from blank control wells (containing no enzyme) from all experimental measurements.

- Normalization: If using an internal control (e.g., a fluorescence standard), normalize signals accordingly.

- Outlier Identification: Use statistical tests to identify non-conforming data points. For replicate v0 values at a given [S], the Grubbs' test can identify a single outlier. For non-linear progress curves, advanced software like MARS can employ algorithms to flag anomalous kinetic traces [3].

- Inspection and Justification: Manually inspect flagged outliers. Discard data only if a clear technical fault (e.g., pipetting error, bubble in well) can be identified and documented. Arbitrary removal of data to improve fit statistics invalidates the analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software Solutions

Implementing best practices requires high-quality materials and analytical tools. The following table details key resources for photo-enzyme kinetics and general data analysis.

Table 2: Research Reagent and Software Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function in Research | Key Rationale for Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chiral Nitrile Precursors [1] | Chemical Substrate | Acts as a radical precursor in photo-enzyme catalyzed remote C–H acylation. | High chemical purity and defined stereochemistry are prerequisite for obtaining high enantiomeric ratios and reproducible reaction yields. |

| Engineered Acyltransferase Mutant Library | Biological Catalyst | Provides the enantioselective environment for radical trapping and C–C bond formation. | Well-characterized kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) for each mutant enable informed enzyme selection and reliable prediction of reaction scales. |

| Pre-defined Enzyme Kinetics Assay Protocols [3] | Software Module | Offers standardized instrument settings (wavelengths, gain, intervals) for common assays. | Eliminates configuration errors, ensures consistency across users and days, and accelerates reliable assay setup. |

| MARS Data Analysis Software [3] | Analysis Suite | Performs Michaelis-Menten, Lineweaver-Burk, and other non-linear curve fittings on kinetic data. | Uses validated algorithms to calculate Km and Vmax with standard errors and confidence intervals, ensuring analytical rigor and reproducibility. |

| FDA 21 CFR Part 11 Compliant Software [3] | Data Management | Provides audit trails, electronic signatures, and secure data storage for enzyme analyzers. | Maintains data integrity for regulatory submissions in drug development, ensuring all data modifications are tracked and accountable. |

Effective Data Presentation and Visualization

Clear presentation transforms robust data into compelling scientific narrative. Best practices are derived from authoritative sources on data communication [4].

5.1 Principles for Figures and Tables

- Single Key Message: Each figure or table should communicate one primary finding. For enzyme kinetics, this could be the comparison of Km values between wild-type and mutant enzymes [5].

- Standalone Clarity: Visuals should be interpretable without reading the main text. This requires descriptive titles, clear axis labels with units, and defined symbols [4].

- Data Density Balance: Avoid clutter. A Michaelis-Menten plot should show all individual replicate data points, not just the mean, while maintaining readability [2] [5].

- Accessible Color Schemes: Use color to enhance, not decorate. For multi-enzyme comparisons, choose a color palette with sufficient luminance contrast (e.g., blue #4285F4 and orange #FBBC05). Avoid red/green contrasts, which are problematic for color-blind readers [6] [7]. Use shades of gray (#5F6368, #F1F3F4) for control data or background elements [8].

5.2 Standard for Presenting Kinetic Parameters When reporting derived parameters like Km and Vmax, a table must include the estimate, its standard error (or confidence interval), and the goodness-of-fit metric (e.g., R²). Never report a parameter without a measure of its uncertainty [2].

Table 3: Model Presentation of Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

| Enzyme Variant | Km (μM) | 95% CI for Km | Vmax (nmol/s/mg) | 95% CI for Vmax | R² of Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 125 | (118, 132) | 450 | (435, 465) | 0.993 |

| Mutant A (S112A) | 85 | (79, 91) | 210 | (202, 218) | 0.987 |

Visualizing Workflows and Logical Frameworks

Diagrams clarify complex experimental and conceptual relationships. The following Graphviz-generated diagrams adhere to WCAG contrast guidelines, using a foreground text color of #202124 on light backgrounds and #FFFFFF on dark backgrounds to ensure a minimum 4.5:1 contrast ratio [9] [7].

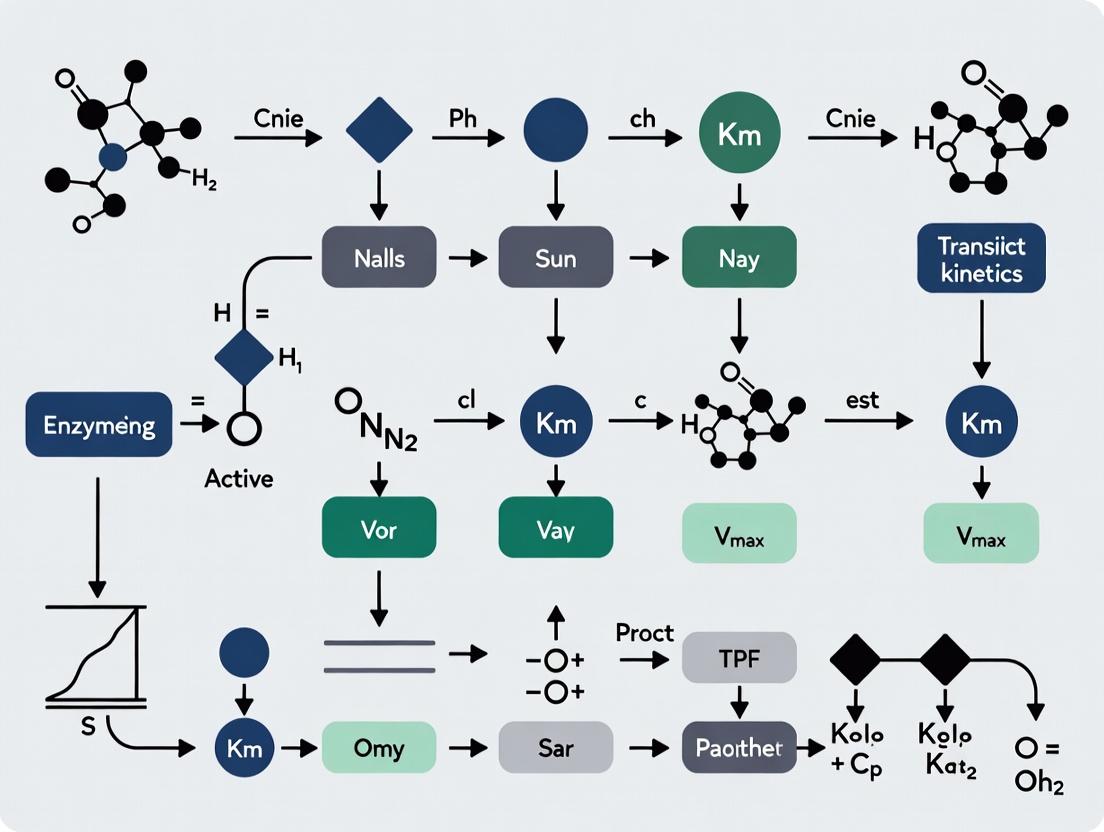

Diagram 1: Photo-Enzyme Kinetics Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Logical Framework Linking Data to Scientific Progress

The path from a kinetic assay to a genuine scientific advance is paved with intentional, quality-focused practices. As demonstrated by cutting-edge research [1] and reinforced by fundamental data analysis principles [2] [3], each step—meticulous experimental design, rigorous data processing, clear presentation, and accessible visualization—strengthens the chain linking data to reproducibility and progress. For researchers and drug developers, adopting the protocols, tools, and standards outlined here is not an administrative burden but a critical investment in the credibility, efficiency, and ultimate impact of their scientific work.

The reproducibility and reliability of enzyme kinetics data are foundational to progress in biochemistry, drug discovery, and systems biology. Historically, a critical analysis of the scientific literature has revealed that publications often omit essential experimental details, such as precise assay conditions, enzyme purity, or the full context of kinetic parameters [10] [11]. These omissions make it impossible to accurately reproduce, compare, or computationally model biological processes, creating a significant barrier to scientific advancement.

To address this, the STRENDA (Standards for Reporting ENzymology DAta) Consortium was established. This international commission of experts has developed a set of minimum information guidelines to ensure that all data necessary to interpret, evaluate, and repeat an experiment are comprehensively reported [10] [11]. The STRENDA Guidelines have gained widespread recognition, with over 60 international biochemistry journals now recommending or requiring their use for authors publishing enzyme kinetics data [12] [13]. This framework represents the established gold standard for reporting enzyme functional data, ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and utility for the broader research community.

The STRENDA Guidelines: A Two-Level Reporting Framework

The STRENDA Guidelines are structured into two complementary levels, designed to capture all information required for a complete understanding of an enzymology experiment [12].

Level 1A focuses on the comprehensive description of the experimental setup. Its purpose is to provide enough detail for another researcher to exactly replicate the experiment. As shown in Table 1, its requirements span from the precise identity of the enzyme to the exact conditions of the assay.

Table 1: Core Reporting Requirements of STRENDA Level 1A (Experiment Description)

| Category | Required Information | Purpose & Example |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Identity | Accepted name, EC number, balanced reaction, organism, sequence accession. | Unambiguously defines the catalyst. E.g., "Hexokinase (EC 2.7.1.1) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, UniProt P04806". |

| Enzyme Preparation | Source, purification procedure, purity criteria, oligomeric state, modifications (tags, mutations). | Informs on enzyme quality and potential experimental artifacts. E.g., "Recombinant His-tagged protein, purified to >95% homogeneity by Ni-NTA chromatography". |

| Storage Conditions | Buffer, pH, temperature, additives, freezing method. | Ensures enzyme stability is maintained pre-assay. |

| Assay Conditions | Temperature, pH, buffer identity/concentration, metal salts, all component purities, substrate concentration ranges. | Defines the exact chemical environment of the reaction. E.g., "Assayed at 30°C in 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl₂". |

| Activity Measurement | Method (continuous/discontinuous), direction, measured reactant, proof of initial rate conditions. | Validates the integrity of the primary data collection. |

Level 1B defines the minimum information required to report and validate the resulting activity data itself. Its goal is to enable a rigorous quality check and allow others to reuse the data with confidence. The requirements are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Core Reporting Requirements of STRENDA Level 1B (Data Description)

| Data Type | Required Information | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| General Data | Number of independent experiments, statistical precision (e.g., SD, SEM), specification of data deposition (e.g., DOI). | Ensures statistical robustness and FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles. |

| Kinetic Parameters | Model/equation used, values for kcat, Km, kcat/Km, etc., with units. Quality of fit measures. | Allows critical evaluation of the fitted constants. The use of IC₅₀ values without supporting data is discouraged [12]. |

| Inhibition Data | Mechanism (competitive, uncompetitive), Ki value with units, time-dependence/reversibility. | Essential for accurate interpretation in drug discovery contexts. |

| Equilibrium Data | Tabulated equilibrium concentrations, calculated K'eq, description of how reactants were measured. | Required for thermodynamic analyses. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing STRENDA in Practice

Adhering to STRENDA is not a post-hoc reporting exercise but a holistic approach to experimental design and documentation. The following methodology outlines key stages.

A. Pre-Assay Documentation Begin by documenting the enzyme identity (IUBMB name, EC number, source organism, sequence variant) and preparation details (expression system, purification protocol, final storage buffer with precise pH and temperature). Determine and report the enzyme's purity (e.g., by SDS-PAGE) and oligomeric state (e.g., by size-exclusion chromatography) [12].

B. Assay Design and Validation Design the reaction mixture to include all components: buffer, salts, substrates, cofactors, and necessary additives (e.g., DTT, BSA). Precisely specify the assay pH (not just the buffer), temperature (with control method), and the chemical identity and purity of all substrates [12]. Before collecting formal data, perform two critical validation experiments: 1) Demonstrate linearity of product formation over time to prove initial velocity conditions are met. 2) Show proportionality between the initial velocity and the enzyme concentration used. These validate that the assay measures true enzyme activity [12].

C. Data Collection and Analysis Collect progress curves or time-point data across a suitable range of substrate concentrations. For inhibition studies, include appropriate controls (e.g., no inhibitor). Analyze data by fitting to the relevant kinetic model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten, Hill equation) using non-linear regression. Report the best-fit parameters with associated errors (e.g., standard error from the fit) and the goodness-of-fit metrics [12]. Clearly state any software used for analysis.

D. Reporting and Deposition Structure the manuscript's Methods and Results sections to address all items in STRENDA Level 1A and 1B. Deposit the final kinetic dataset and associated metadata in a public repository such as STRENDA DB to obtain a persistent identifier (DOI) for citation [13] [14].

The STRENDA DB Ecosystem: Validation, Sharing, and Reuse

The STRENDA Guidelines are operationalized through STRENDA DB, a dedicated online platform for validating, registering, and sharing enzyme kinetics data [13] [14]. Its workflow enforces and simplifies compliance.

Diagram: STRENDA DB Submission and Validation Workflow (83 characters)

The platform's structure mirrors the organization of a scientific study. A single Manuscript entry contains one or more Experiments, each studying a specific enzyme or variant. Each Experiment can be linked to multiple Datasets, representing distinct assay conditions (e.g., different pH values or inhibitor concentrations) [14].

Table 3: Benefits of Using STRENDA DB for Researchers and Journals

| Stakeholder | Key Benefits |

|---|---|

| Researcher (Author) | Automated checklist ensures no critical detail is omitted before journal submission. Receives a permanent STRENDA Registry Number (SRN) and DOI to cite, increasing data visibility and credit [13] [14]. |

| Journal & Reviewer | Streamlines review by guaranteeing data reporting completeness. Journals like Nature, JBC, and eLife recommend its use [11] [14]. |

| Research Community | Provides a growing, FAIR-compliant repository of high-quality, reusable kinetic data for meta-analysis, modeling, and systems biology [11] [14]. |

An empirical analysis demonstrated that using STRENDA DB would capture approximately 80% of the relevant information often missing from published papers, highlighting its practical impact on data quality [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for STRENDA-Compliant Work

A robust, STRENDA-compliant enzymology study relies on well-characterized reagents. Below is a non-exhaustive list of essential materials.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics

| Reagent Category | Function in Assay | STRENDA Reporting Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Buffers (e.g., HEPES, Tris, Phosphate) | Maintain constant assay pH, which critically affects enzyme activity and stability. | Exact identity, concentration, counter-ion, and temperature at which pH was measured [12]. |

| Metal Salts (e.g., MgCl₂, KCl, CaCl₂) | Act as cofactors, stabilize enzyme structure, or contribute to ionic strength. | Identity and concentration. For metalloenzymes, reporting estimated free cation concentration (e.g., pMg) is highly desirable [12]. |

| Substrates & Cofactors | Reactants transformed by the enzyme (e.g., ATP, NADH, peptide substrates). | Unambiguous identity (using PubChem/CHEBI IDs), purity, and source. The balanced reaction equation must be provided [12] [15]. |

| Stabilizers/Additives (e.g., DTT, BSA, Glycerol, EDTA) | Prevent enzyme inactivation, reduce non-specific binding, or chelate interfering metals. | Identity and concentration of all components in the assay mixture [12]. |

| Detection Reagents | Enable monitoring of reaction progress (e.g., chromogenic/fluorogenic probes, coupling enzymes). | For coupled assays, full details of all coupling components and validation that the coupling system is not rate-limiting [12]. |

Within the broader thesis on best practices for reporting enzyme kinetics data, the STRENDA (Standards for Reporting Enzymology Data) Guidelines establish a foundational framework to ensure reproducibility, data quality, and utility for computational modeling [12]. At the core of these guidelines is Level 1A, which mandates the comprehensive reporting of experimental metadata. This article provides a technical deep dive into Level 1A, dissecting its requirements for enzyme identity, assay conditions, and storage. This metadata is not merely administrative; it is the critical context that transforms a standalone kinetic parameter into a reusable, trustworthy scientific fact. Over 60 international biochemistry journals now recommend authors consult these guidelines, underscoring their role as a community standard for credible enzymology [12]. The subsequent Level 1B guidelines detail the reporting of the kinetic parameters and activity data themselves, but their correct interpretation is wholly dependent on the robust metadata captured in Level 1A [12].

Deconstructing STRENDA Level 1A: The Essential Metadata Tables

The STRENDA Level 1A specification is systematically organized into three interconnected domains. The following tables summarize the mandatory quantitative and descriptive data required for each.

Enzyme Identity and Preparation

This section demands unambiguous identification of the catalytic entity and a complete description of its source and preparation history [12].

Table 1: Mandatory Metadata for Enzyme Identity and Preparation [12]

| Data Field | Technical Specification & Examples |

|---|---|

| Enzyme Identity | Accepted IUBMB name, EC number, balanced reaction equation. |

| Sequence & Source | Sequence accession number (e.g., UniProt ID), organism species/strain (with NCBI Taxonomy ID), oligomeric state. |

| Modifications & Purity | Details of post-translational modifications, artificial tags (e.g., His-tag), purity criteria (e.g., >95% by SDS-PAGE). |

| Preparation | Commercial source or detailed purification protocol, description of final preparation (e.g., lyophilized powder, glycerol stock). |

Enzyme Storage Conditions

Precise storage conditions are required to justify the enzyme’s functional state at the experiment’s outset [12].

Table 2: Mandatory Metadata for Enzyme Storage Conditions [12]

| Data Field | Technical Specification & Examples |

|---|---|

| Storage Buffer | Full buffer composition (e.g., 50 mM HEPES-KOH, 100 mM NaCl, 10% v/v glycerol), pH (and temperature of pH measurement). |

| Temperature & Method | Exact temperature (e.g., -80 °C), freezing method (e.g., flash-freezing in liquid N₂). |

| Additives & Stability | Concentrations of stabilizers (e.g., 1 mM DTT), metal salts, protease inhibitors. Optional: statement on activity loss over time. |

Assay Conditions

This defines the exact experimental environment in which kinetic activity was measured [12].

Table 3: Mandatory Metadata for Assay Conditions [12]

| Data Field | Technical Specification & Examples |

|---|---|

| Assay Environment | Temperature, pH, pressure (if not atmospheric), buffer identity and concentration (including counter-ion). |

| Reaction Components | Identity and purity of all substrates, cofactors, and coupling enzymes. Unambiguous identifiers (e.g., PubChem CID) are recommended. |

| Concentrations | Enzyme concentration (in µM or mg/mL), substrate concentration range used, concentrations of varied components (e.g., inhibitors). |

| Activity Verification | Evidence of initial rate conditions (e.g., <10% substrate depletion), proportionality between velocity and enzyme concentration. |

Experimental Protocols: From Metadata to Kinetic Data

The mandatory metadata of Level 1A supports specific, reproducible experimental methodologies for generating kinetic data.

Establishing Initial Velocity Conditions

A core requirement is demonstrating that reported velocities are initial rates, measured under steady-state conditions where substrate depletion, product inhibition, and enzyme instability are negligible [16].

- Protocol: Conduct a progress curve experiment by mixing enzyme and substrate, then measuring product formation over time. Perform this at multiple enzyme concentrations (e.g., 0.5x, 1x, 2x relative levels) [16].

- Validation: Identify the time window where product formation is linear (typically <10% substrate conversion) and where the maximum plateau product level is proportional to the enzyme concentration. This confirms stable enzyme activity [16].

- Application: Use the enzyme concentration and time point from the linear regime for all subsequent kinetic experiments.

Determining the Michaelis Constant (Kₘ)

Accurate Kₘ determination is a fundamental kinetic measurement explicitly referenced in STRENDA Level 1B [12].

- Protocol: Measure initial velocity at a minimum of 8 substrate concentrations spanning a range from approximately 0.2 to 5.0 times the suspected Kₘ [16]. The reaction should be started by adding enzyme.

- Analysis: Fit the data (velocity vs. [substrate]) to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression. For competitive inhibitor studies, it is essential to use substrate concentrations at or below the Kₘ value [16].

- Reporting: State the fitted Kₘ value with units, the model used, and the method of fitting (e.g., non-linear least squares in GraphPad Prism).

Visualization: Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and workflows central to applying STRENDA standards.

STRENDA DB Manuscript Submission and Validation Flow

Enzyme Assay Validation and Optimization Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and reagents necessary to conduct experiments that comply with STRENDA Level 1A reporting standards [12] [16] [17].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Compliant Enzyme Kinetics

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in STRENDA Compliance |

|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Preparation | The catalytic entity. Must be characterized for source, sequence, purity, and storage conditions as per Level 1A [12] [16]. |

| Defined Substrates & Cofactors | Reaction components. Must be identified with high purity and sourced from qualified suppliers to satisfy assay condition reporting [12] [16]. |

| Buffers and Salt Solutions | Establish assay pH and ionic strength. Precise composition and concentration are mandatory Level 1A metadata [12]. |

| Detection System Components | (e.g., fluorescent dyes, coupled enzymes, antibodies). Enable quantitative measurement of initial rates, required for Level 1B data generation [16] [17]. |

| Reference Inhibitors/Activators | Used as controls to validate assay performance and mechanism studies, supporting high-quality inhibition/activation data [16]. |

Within the framework of best practices for reporting enzyme kinetics data, the STRENDA (Standards for Reporting Enzymology Data) Guidelines serve as the international benchmark for ensuring data completeness, reproducibility, and utility [18]. These guidelines are structured into two tiers: Level 1A, which defines the minimum information required to describe experimental materials and methods, and Level 1B, the focus of this guide, which specifies the essential data for reporting enzyme activity results [19]. Adherence to Level 1B transforms raw observations into reusable, trustworthy scientific knowledge by mandating precise reporting of kinetic parameters, comprehensive statistics, and rigorous data accessibility. This practice is endorsed by more than 60 international biochemistry journals, underscoring its critical role in advancing enzymology and drug discovery research [12] [18].

Decoding Level 1B: Core Data Reporting Requirements

Level 1B of the STRENDA Guidelines establishes the minimum information necessary to describe enzyme activity data, allowing for quality assessment and ensuring the data's long-term value [12]. Its requirements can be categorized into three pillars: kinetic parameters, statistical reporting, and data accessibility.

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Parameter Reporting

The accurate reporting of derived parameters is fundamental. The choice of model and the clarity of definitions are as crucial as the values themselves.

Table 1: Level 1B Requirements for Reporting Kinetic Parameters [12]

| Parameter Category | Required Information | Key Specifications & Units |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Parameters | kcat (turnover number) |

Report as mol product per mol enzyme per time (e.g., s⁻¹, min⁻¹). |

Vmax (maximum velocity) |

Report as specific activity (e.g., mol min⁻¹ (g enzyme)⁻¹). | |

Km (Michaelis constant) |

Concentration units (e.g., µM, mM). Define operational meaning (e.g., S₀.₅). | |

kcat/Km (specificity constant) |

Report as per concentration per time (e.g., M⁻¹ s⁻¹). | |

| Extended Parameters | Michaelis constants for all co-substrates (KM2) |

Required for multi-substrate reactions. |

Inhibition constants (Ki) |

Type (competitive, uncompetitive, etc.) and units required. | |

Product inhibition constants (KP) |

For all products, including cofactors. | |

| Hill coefficient / Cooperativity | Include the defining equation. | |

Equilibrium constant (Keq') |

With reference to the full reaction equation and direction. | |

| Critical Metadata | Kinetic equation/model used | e.g., Michaelis-Menten, Hill equation. |

| Method of parameter obtention | e.g., non-linear least squares fitting, direct linear plot. Software used. | |

| Quality of fit measures | Report for the chosen and any alternative models considered. |

Special Considerations:

- IC₅₀ Values: Their use is not recommended for definitive characterization because the relationship to true inhibition constants varies with experimental conditions. Reporting

Kiwith its mechanism is preferred [12]. - Inhibition Data: Must include assessment of time-dependence and reversibility. The type of inhibition (reversible, tight-binding, or irreversible) must be clearly stated, with appropriate parameters [12].

- Equilibrium Data: Requires tabulation of measured equilibrium concentrations for all reactants and specification of how they were determined (e.g., directly measured or estimated) [12].

Statistical and Reproducibility Reporting

A cornerstone of Level 1B is the transparent reporting of data robustness, which is essential for critical evaluation.

Table 2: Level 1B Requirements for Statistical Reporting [12]

| Requirement | Description | Reporting Example |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Independent Experiments (n) | Indicate the biological/technical replication level and what varied between replicates (e.g., new enzyme prep, different day). | "n = 3 independent enzyme preparations." |

| Precision of Measurement | Report the dispersion of the data (e.g., standard deviation, standard error of the mean, confidence intervals). | "Km = 1.5 ± 0.2 mM (mean ± SD, n=4)." |

| Parameter Estimation Method | Specify the fitting algorithm and weighting methods. Acknowledge statistical assumptions. | "Parameters were derived by non-linear regression minimizing the sum of squared residuals, assuming constant relative error." |

| Proportionality Evidence | Demonstrate that the initial velocity is proportional to the enzyme concentration within the range used. | "Initial velocity was linear with enzyme concentration up to 10 nM (R² > 0.98)." |

Data Accessibility and Deposition

Level 1B moves beyond the article to ensure data longevity and reusability. The ultimate standard is to deposit primary experimental data (e.g., time-course data for each substrate concentration) [12].

- Requirement: Data should be made findable (via a DOI or URL) and accessible (openly available post-publication).

- Format: Using structured, machine-readable formats like EnzymeML enhances interoperability.

- Platform: The STRENDA DB database provides a dedicated platform for validation and deposition. Successful submission generates a STRENDA Registry Number (SRN) and a DOI for the dataset, which can be included with the manuscript [19] [18].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from experiment to publication, emphasizing the Level 1B reporting and validation pathway.

STRENDA DB Compliance and Publication Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Generating Level 1B-Compliant Data

Protocol: Determining Basic Michaelis-Menten Parameters

This protocol outlines the steps to generate data suitable for extracting Km, Vmax, and kcat in compliance with Level 1B.

1. Experimental Design:

- Substrate Concentration Range: Use a minimum of 8-10 substrate concentrations, spaced appropriately (e.g., geometrically) to bracket the expected

Km(typically from 0.2 to 5 xKm). - Enzyme Concentration: Must be determined from a preliminary proportionality experiment to ensure initial rate conditions (≤5% substrate conversion). This concentration must be reported [12].

- Controls: Include negative controls (no enzyme, heat-inactivated enzyme) for background subtraction.

2. Data Collection:

- Initial Rates: Measure the initial linear phase of product formation or substrate depletion. Specify how linearity was confirmed (e.g., R² > 0.98 over the time course used).

- Replicates: Perform each substrate concentration in at least duplicate technical replicates, with the entire experiment repeated for multiple independent enzyme preparations (biological replicates). The nature of the replicates must be stated [12].

3. Data Analysis & Reporting:

- Fitting: Fit the initial rate (v) vs. substrate concentration ([S]) data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])using non-linear regression. - Statistical Output: Report the fitted parameters (

Km,Vmax) with their standard errors or confidence intervals from the fit. CalculatekcatfromVmax / [Enzyme]. - Quality Indicators: Provide a plot of residuals to demonstrate the goodness of fit and the appropriateness of the model.

Protocol: Conducting and Reporting Inhibition Studies

1. Determining Reversibility and Mode:

- Dilution/Jump Assay: Pre-incubate enzyme with inhibitor. Initiate reaction by a large dilution (e.g., 50-fold) or addition of a high concentration of substrate. Recovery of activity indicates reversible inhibition.

- Mode Determination: Measure initial rates at varying substrate concentrations and several fixed inhibitor concentrations. Global fitting of the data to competitive, uncompetitive, or mixed inhibition models allows determination of the inhibition mode and

Kivalue [12].

2. Key Reporting Requirements:

- Clearly state the mechanism of inhibition (e.g., competitive, non-competitive) and the associated model used for fitting.

- Report the

Kivalue with units and its confidence interval. - If reporting an IC₅₀, mandatorily state the substrate concentration at which it was determined, as the value is condition-dependent [12].

The following diagram summarizes the logical decision pathway for characterizing an enzyme inhibitor according to Level 1B standards.

Inhibition Characterization Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Compliance with Level 1B begins with rigorous experimental execution. The following toolkit details critical reagents and their roles in generating robust kinetics data.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics [12]

| Reagent/Material | Function in Kinetics Experiments | Level 1B Reporting Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Enzyme | The catalyst of defined identity and oligomeric state. Source (recombinant, tissue) and purification details are critical. | Required for calculating kcat. Purity and preparation method are Level 1A/1B metadata. |

| Characterized Substrates & Cofactors | Reactants of known identity and purity, ideally with database IDs (PubChem, ChEBI). | Must be unambiguously identified. Purity affects observed kinetics. |

| Spectrophotometric/Coupled Assay Components (e.g., NADH, ATP, reporter enzymes) | Enable continuous monitoring of reaction progress. Coupling enzymes must be in excess to avoid being rate-limiting. | The assay method and components (including coupling systems) must be fully described. |

| Buffers with Defined Metal Content (e.g., Tris-HCl, HEPES, with MgCl₂) | Maintain constant pH and provide essential metal cofactors. Counter-ions and free metal concentration can be critical. | Exact buffer identity, concentration, pH, temperature, and metal salt details are mandatory. |

| Inhibitors/Activators of Defined Structure | Molecules used to probe enzyme mechanism and regulate activity. | Must be unambiguously identified. For inhibitors, mechanism and Ki are required over IC₅₀. |

| Data Analysis Software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot, KinTek Explorer) | Tools for non-linear regression, model fitting, and statistical analysis. | The specific software and fitting algorithms used must be reported. |

The STRENDA Level 1B requirements are not an arbitrary checklist but the structural foundation for credible, reproducible, and reusable enzymology. By systematically reporting kinetic parameters with their statistical context, detailing experimental provenance, and depositing primary data, researchers contribute to a cumulative body of knowledge that is greater than the sum of its parts. For the drug development professional, this translates into robust structure-activity relationships, reliable Ki values for lead optimization, and clear mechanistic understanding. Ultimately, adopting Level 1B reporting is a commitment to scientific integrity, elevating the quality of published research and accelerating discovery across biochemistry and molecular pharmacology.

In the critical fields of biocatalysis, enzymology, and drug development, research advancement is fundamentally constrained not by a lack of data, but by a crisis of data structure and interoperability. High-throughput techniques generate vast amounts of enzymatic data, yet the predominant practice of recording results in unstructured spreadsheets or PDFs creates profound inefficiencies [20]. This fragmented approach leads to incomplete metadata, hampers reproducibility, and makes the re-analysis of published work nearly impossible [20]. The consequence is a significant loss of scientific trust and productivity, as researchers spend more time managing and reformatting data than conducting novel analysis [20].

The solution lies in a paradigm shift toward standardized, machine-readable data formats. This whitepaper argues that adopting structured data standards, specifically the EnzymeML format, is a foundational best practice for reporting enzyme kinetics data. Structured data transcends the limitations of spreadsheets by embedding rich experimental context, enabling seamless exchange, and serving as the essential substrate for advanced computational analysis, including machine learning and automated process simulation [21] [22].

The EnzymeML Framework: A Standardized Data Container

EnzymeML is an open, community-driven data standard based on XML/JSON schemas, designed explicitly for catalytic reaction data [21]. It functions as a comprehensive container that organizes all elements of a biocatalytic experiment into a consistent, machine-readable structure [21] [20].

An EnzymeML document is formally an OMEX archive (a ZIP container) that integrates several key components [20]:

- An experiment file in SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) format containing the metadata, kinetic model, and estimated parameters.

- One or more measurement files (e.g., CSV) storing the raw time-course data for substrates and products.

- A manifest file (XML) listing all contents of the archive [20].

This structure ensures that the intricate relationships between experimental conditions, raw observations, and derived models are permanently and explicitly maintained.

Core Components of an EnzymeML Document

The power of EnzymeML stems from its semantically defined elements, which collectively describe an experiment fully [21]:

- Protein Data: Describes the biocatalyst, including amino acid sequence, EC number, source organism, and functional annotations.

- Reactant Data: Defines all small molecules (substrates, products, inhibitors, activators) using canonical identifiers like SMILES or InChI, ensuring unambiguous chemical identification.

- Reaction Data: Specifies the reaction equation, stoichiometry, reversibility, and links to the participating species and modifiers.

- Measurement Data: Contains the core experimental observations—time-course concentration data—alongside the precise environmental conditions (temperature, pH, buffer) under which they were collected [21].

This structured approach directly supports the FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management. EnzymeML makes data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable by design, transforming isolated datasets into community assets [21] [22].

Diagram 1: Traditional Fragmented Data Workflow (76 words)

Best Practices in Reporting: From Measurement to Modeling

Adopting EnzymeML integrates with and reinforces established methodological best practices in enzyme kinetics. Two critical areas are the rigorous analysis of kinetic data and the comprehensive reporting of experimental metadata.

Kinetic Parameter Estimation: Embracing Nonlinear Regression

The accurate determination of parameters like Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ is a cornerstone of enzyme kinetics. Historically, linear transformations of the Michaelis-Menten equation (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plots) were used for convenience. Modern best practice, however, mandates the use of nonlinear regression to fit the untransformed data directly to the mechanistic model [23] [24].

- Statistical Validity: Linear transformations distort the error structure of the data, violating the assumptions of standard linear regression and leading to biased parameter estimates. Nonlinear regression fits the correct error model [23].

- Direct Parameter Estimation: Nonlinear regression provides best-fit estimates and standard errors for the actual kinetic parameters, not apparent values derived from rearranged equations [23].

- Model Flexibility: It readily accommodates complex models, such as those accounting for substrate contamination, background signal, or multi-substrate kinetics, where linearization is impossible or impractical [23] [24].

An EnzymeML document naturally encapsulates this practice by storing both the raw time-series concentration data and the fitted kinetic model (e.g., the irreversible Henri-Michaelis-Menten equation) with its estimated parameters, ensuring the analysis is fully transparent and reproducible [22] [20].

Essential Metadata for Reproducibility

Incomplete reporting of experimental conditions is a major barrier to reproducibility [20]. A best-practice EnzymeML document mandates the inclusion of the following metadata categories:

Table 1: Essential Metadata Categories for Reproducible Enzyme Kinetics

| Metadata Category | Specific Elements | Common Pitfalls (Spreadsheet Era) |

|---|---|---|

| Biocatalyst | Enzyme source (organism, strain), purity assessment (e.g., SDS-PAGE, activity/µg), concentration in assay, storage buffer, modification state (immobilized, tagged). | Omitting purity data, reporting only commercial supplier name, unclear concentration units. |

| Reaction Mixture | Precise concentrations of all substrates, products, cofactors, inhibitors. Buffer identity, ionic strength, and pH. Temperature control method and accuracy. | Incomplete buffer recipes, unreported pH verification, assuming stock concentrations are accurate. |

| Assay Methodology | Detection method (spectrophotometry, fluorescence, HPLC), instrument calibration details, path length, wavelength(s). Assay initialisation protocol (order of addition). | Omitting calibration curves, not specifying the instrument model or settings, vague initiation description. |

| Data Processing | Software used for analysis, fitting algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt), weighting schemes, handling of background/subtraction. | Not documenting data transformations, using proprietary software without sharing settings file. |

The Integrated Workflow: EnzymeML in Action

The true value of a structured format is realized in end-to-end automated workflows. Recent research demonstrates a seamless pipeline from experiment to simulation using EnzymeML [22].

1. Structured Data Acquisition: Experimental data, such as the oxidation of ABTS by laccase monitored in a capillary flow reactor, is recorded directly into an EnzymeML-compatible spreadsheet template [22]. 2. Kinetic Modeling & Export: Data is parsed into a Python environment (e.g., a Jupyter Notebook) for model fitting. The resulting data, model, and parameters are serialized into a standardized EnzymeML document [22]. 3. Ontology-Based Integration: The EnzymeML document is processed using an ontology (e.g., Systems Biology Ontology terms) to create a knowledge graph. This adds semantic meaning, ensuring concepts are unambiguous [22]. 4. Automated Process Simulation: The semantically rich data is automatically transferred via API to a process simulator like DWSIM. The simulator is configured to model the bioreactor, enabling in-silico scale-up and optimization without manual data re-entry [22].

This workflow eliminates error-prone manual steps, dramatically accelerates the design cycle, and ensures that the simulation is grounded in fully traceable experimental data [22].

Diagram 2: Integrated, FAIR Data Workflow with EnzymeML (78 words)

Validation, Sharing, and the Path to FAIR Data

Implementing a standard requires tools for validation and community infrastructure for sharing.

- Validation: The EnzymeML ecosystem provides a validation tool that performs both schema validation (checking JSON/XML structure) and consistency checks (ensuring internal logical rules are met), guaranteeing document integrity before publication or exchange [25] [26].

- Database Integration: EnzymeML is designed for interoperability with public databases. The kinetic database SABIO-RK accepts EnzymeML uploads, and a Dataverse metadata block schema facilitates deposition into institutional repositories [26] [20]. This creates a direct, low-friction path from the researcher's desktop to sustainable public archiving.

- Overcoming Legacy Challenges: Transitioning from spreadsheets requires a cultural and technical shift. The strategy involves providing user-friendly spreadsheet templates for data entry, developing conversion tools for historical data, and integrating EnzymeML export into laboratory software and electronic lab notebooks (ELNs) [20].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Data Management Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional (Spreadsheet/PDF) | EnzymeML-Enabled |

|---|---|---|

| Reproducibility | Low. Critical metadata is often omitted or buried in notes [20]. | High. Metadata is structured, mandatory, and linked to data. |

| Data Exchange | Manual, error-prone reformatting and copy-pasting between tools [20]. | Automated. Machine-readable format enables seamless tool interoperability [21] [22]. |

| Reusability & Integration | Difficult. Data must be manually extracted and interpreted for new analyses. | Straightforward. Data is ready for computational reuse, simulation, and meta-analysis [22]. |

| Long-Term Preservation | At risk. Format obsolescence and lack of context lead to "data rot." | Sustainable. Open standard with rich context ensures future usability. |

| Support for AI/ML | Poor. Unstructured data requires extensive pre-processing. | Built-for-purpose. Structured data is the ideal substrate for training machine learning models [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Enzyme Kinetics

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ABTS (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) | Chromogenic substrate. Oxidation yields a stable, green-colored radical cation easily quantified by spectrophotometry at 420 nm [22]. | Standard activity assay for oxidoreductases like laccases and peroxidases [22]. |

| Laccase from Trametes versicolor | Model oxidoreductase enzyme. Catalyzes the oxidation of phenols and aromatic amines coupled to oxygen reduction [22]. | Workhorse enzyme for studying reaction kinetics in biocatalysis and process development [22]. |

| DNA-Hemin Conjugate / G4-Hemin DNAzyme | Synthetic nucleic acid enzyme (nucleozyme). Comprises a guanine quadruplex (G4) DNA structure bound to hemin, exhibiting peroxidase-like activity [27]. | Enables the construction of Controllable Enzyme Activity Switches (CEAS) for stimulus-responsive biosensing and regulated catalysis [27]. |

| Capillary Flow Reactor (FEP tubing) | Microscale continuous-flow reactor. Provides high surface-to-volume ratio, precise residence time control, and efficient mass/heat transfer [22]. | Rapid screening of enzyme kinetics under different conditions (pH, T, [O₂]) and integration with online analytics [22]. |

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | Chromogenic peroxidase substrate. Yields a blue-colored product upon oxidation, measurable at 650 nm, and can be stopped with acid to a yellow product [27]. | Common substrate for detecting peroxidase activity in assays like ELISA and with DNAzyme systems [27]. |

Moving beyond the spreadsheet is not merely a technical upgrade; it is a necessary evolution for the field of enzyme kinetics. The adoption of structured, standardized data formats like EnzymeML represents a core best practice that directly addresses the pervasive challenges of reproducibility, efficiency, and knowledge transfer in research and drug development.

By providing a universal container for the complete experimental narrative—from protein sequence and reaction conditions to raw data and fitted models—EnzymeML transforms private data into collaborative, FAIR-compliant community resources. It bridges the gap between experimental biology and computational simulation, laying the groundwork for a future of data-driven biocatalysis powered by machine learning and automated discovery. The tools and community frameworks are now established; the next step in accelerating scientific progress is their widespread adoption by researchers, journals, and databases.

From Raw Data to Reliable Parameters: Advanced Methodologies and Analytical Tools in Practice

Core Methodologies and Strategic Comparison

The selection between initial rate analysis and progress curve analysis is a fundamental decision in enzyme kinetics. This choice dictates experimental design, data processing, and the reliability of the extracted kinetic parameters (kcat, Km). Adherence to standardized reporting guidelines, such as the STRENDA (Standards for Reporting Enzymology Data) Guidelines, is critical for ensuring reproducibility and data utility across both methodologies [12].

The table below provides a high-level comparison of the two core approaches.

Table 1: Strategic Comparison of Initial Rate Analysis and Progress Curve Analysis

| Aspect | Initial Rate Analysis | Progress Curve Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Measures the reaction velocity at time zero, under conditions where substrate depletion is negligible (typically <5-10%). | Analyzes the entire time course of product formation or substrate depletion to extract parameters. |

| Key Assumption | The steady-state or initial steady-state approximation is valid; [S] ≈ constant during measurement. | A valid kinetic model (e.g., integrated Michaelis-Menten) describes the entire reaction time course. |

| Typical Substrate Conversion | Low (≤10%) [28]. | High (can approach 70-100%) [28]. |

| Experimental Effort | High. Requires multiple independent reactions at different [S] to construct one velocity curve. | Lower. A single reaction time course at one [S] can, in theory, yield Vmax and Km. |

| Data Density | Single data point (initial velocity) per reaction condition. | Many data points (concentration vs. time) per reaction condition. |

| Information Content | Provides a snapshot of velocity under defined conditions. Ideal for simple Michaelis-Menten kinetics. | Reveals time-dependent phenomena: product inhibition, enzyme inactivation, or reversibility. |

| Computational Complexity | Low to moderate. Often uses linear transformations or non-linear regression of velocity vs. [S]. | Higher. Requires solving an integral equation or numerically fitting a differential equation model [29]. |

| Best For | Standard characterisation; systems where enzyme is stable and product inhibition is absent; high-throughput screening [30]. | Systems with scarce enzyme/substrate; identifying time-dependent inhibition or inactivation; single-point screening. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Initial Rate Analysis

This protocol is designed to determine kcat and Km under steady-state conditions, in alignment with STRENDA Level 1A/B reporting requirements [12].

Reaction Mixture Design:

- Prepare a master mix containing all reaction components except the substrate (enzyme, buffer, cofactors, salts). The enzyme concentration ([E]) must be significantly lower than all substrate concentrations ([S]) to maintain steady-state conditions.

- In a 96-well plate or cuvettes, dispense aliquots of the master mix.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the substrate at varying concentrations. The range should ideally span from

0.25Kmto4-5Km. Include a negative control without enzyme.

Initial Rate Measurement:

- Use a continuous assay (e.g., spectrophotometric, fluorometric) if possible. Immediately begin monitoring the signal (e.g., absorbance of NADH at 340 nm).

- Record the signal for a duration where the change remains linear (typically <10% substrate conversion). The true initial rate is defined as

(d[P]/dt) at t=0[28]. - For discontinuous assays, quench multiple reaction aliquots at very early, sequential time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 90 seconds) and analyze product formation. The slope of the linear portion of [P] vs. t is the initial rate.

Data Processing:

- For each substrate concentration ([S]), convert the linear signal slope to a reaction velocity (

v, e.g., µM/s). - Plot

vversus[S]. Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v = (Vmax*[S])/(Km + [S])) using non-linear regression. - Extract the parameters

VmaxandKm. Calculatekcat = Vmax / [E]total.

- For each substrate concentration ([S]), convert the linear signal slope to a reaction velocity (

Protocol for Progress Curve Analysis

This protocol leverages the integrated form of the rate equation to extract kinetic parameters from a single reaction time course, reducing experimental load [29] [28].

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare the complete reaction mixture containing enzyme, a single initial substrate concentration ([S]0), and all other components. [S]0 should be on the order of

Km. - The reaction can be run in a standard cuvette or well.

- Prepare the complete reaction mixture containing enzyme, a single initial substrate concentration ([S]0), and all other components. [S]0 should be on the order of

Time-Course Data Collection:

- Initiate the reaction and continuously monitor the signal (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence) until the reaction reaches at least 70-80% completion or equilibrium [28].

- Ensure a high density of data points, especially in the early phase, to accurately define the curve's shape.

Data Fitting and Parameter Extraction:

- Convert the entire signal trajectory to product concentration ([P]) versus time (t).

- Fit the [P] vs. t data directly to the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation:

t = (1/Vmax) * ( [P] + Km * ln( [S]0/([S]0-[P]) ) )using non-linear regression, withVmaxandKmas fitting parameters. - Advanced Numerical Methods: For more complex systems (e.g., with product inhibition), directly fit the differential equation

d[P]/dt = f([S],[P], Vmax, Km, ...)to the progress curve data. Methods using spline interpolation of the data to transform the dynamic problem into an algebraic one have shown robustness and lower dependence on initial parameter estimates [29].

Method Selection and Data Processing Workflow

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting the appropriate kinetic analysis method based on system properties and experimental goals.

From Raw Data to FAIR Kinetic Parameters

After data collection, processing and reporting are critical. The following diagram visualizes the pipeline from raw experimental data to structured, FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) kinetic parameters, incorporating modern data science approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics

| Item | Function & Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Source (recombinant, tissue), purity, and oligomeric state must be reported [12]. | Specific activity, storage conditions (buffer, pH, temperature, cryoprotectants like glycerol), and stability under assay conditions are critical. |

| Substrates & Cofactors | Reactants and essential helper molecules. Identity and purity must be unambiguously defined [12]. | Use database identifiers (PubChem CID, ChEBI ID). For cofactors (NAD(P)H, ATP, metal ions), report concentrations and, for metals, free cation concentration if critical [12]. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains constant pH and ionic environment. | Specify buffer identity, concentration, counter-ion, and pH measured at assay temperature. Include all salts and additives (e.g., DTT, EDTA, BSA) [12]. |

| Detection System | Quantifies product formation/substrate depletion. | Continuous: Spectrophotometer/plate reader (for chromogenic/fluorogenic changes). Discontinuous: HPLC, MS, electrophoresis (requires reaction quenching). |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Validates assay functionality. | Positive: Reaction with all components. Negative: Omit enzyme or use heat-inactivated enzyme. Essential for defining baseline. |

| Reference Databases | For data deposition, validation, and contextualization. | STRENDA DB: For standardized reporting [12]. BRENDA/SABIO-RK: Core kinetic databases [31]. EnzyExtractDB: A new, large-scale LLM-extracted database [32]. SKiD: Integrates kinetics with 3D structural data [31]. |

Best Practices in Data Reporting and Visualization

Consistent with the thesis on best practices, comprehensive reporting is non-negotiable. The STRENDA Guidelines provide a definitive checklist [12].

- Level 1A (Experiment Description): Report full enzyme identity (EC number, sequence), balanced reaction equation, detailed assay conditions (pH, T, buffer, [E], [S] ranges), and measurement methodology.

- Level 1B (Activity Data): Report mean kinetic parameters (

kcat,Km,kcat/Km) with associated precision (standard error/ deviation), the model/fitting method used, and deposit raw progress curves or initial rate data [12] [28]. This allows independent re-analysis.

For visualizations (progress curves, Michaelis-Menten plots):

- Contrast: Ensure a minimum 3:1 contrast ratio for graphical objects (lines, bars) and 4.5:1 for standard text against backgrounds [33] [34].

- Color: Do not use color as the sole information carrier. Use differing symbols or line patterns in addition to color [33].

- Data Sharing: Below figures, provide a link to the underlying numerical data in tabular format, enhancing accessibility and FAIRness [33].

The choice between initial rate and progress curve analysis is not merely technical but strategic. Initial rate analysis remains the gold standard for well-behaved systems and is essential for high-throughput drug discovery screening [30]. Progress curve analysis offers a powerful, information-rich alternative that maximizes data yield from minimal material and is indispensable for diagnosing complex kinetic mechanisms [29] [28].

The future of the field lies in the convergence of rigorous experimentation and advanced data science. The increasing importance of structured datasets like SKiD (linking kinetics to 3D structure) [31] and the use of large language models (LLMs) to extract "dark data" from literature into databases like EnzyExtractDB [32] underscore this trend. Whichever method is chosen, researchers must adhere to STRENDA and FAIR data principles [12], ensuring their hard-won kinetic parameters are reproducible, discoverable, and capable of fueling the next generation of predictive models and enzyme engineering breakthroughs.

Progress curve analysis presents a powerful, resource-efficient alternative to initial velocity studies for determining enzyme kinetic parameters, offering significant reductions in experimental time and material costs [29]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three core computational methodologies for analyzing progress curves: analytical integrals of rate equations, direct numerical integration of differential equations, and spline-based algebraic transformations. Framed within the broader context of establishing best practices for reporting enzyme kinetics data, this whitepaper details the underlying principles, practical implementation protocols, and relative strengths of each approach. We demonstrate that while analytical methods offer high precision where applicable, spline-based numerical approaches provide superior robustness and reduced dependence on initial parameter estimates, making them particularly valuable for complex or noisy datasets encountered in modern drug discovery [29].

The accurate modeling of enzymatic reaction kinetics is foundational to biocatalytic process design, mechanistic enzymology, and inhibitor screening in pharmaceutical development. Traditional initial velocity studies, while established, require extensive experimental replicates at multiple substrate concentrations to construct Michaelis-Menten plots. Progress curve analysis, in contrast, leverages the full time-course of product formation or substrate depletion from a single reaction, thereby drastically reducing experimental effort [29].

The core challenge of progress curve analysis is solving a dynamic nonlinear optimization problem to extract parameters like (V{max}) and (KM) from the time-series data [29]. Multiple computational strategies have been developed, each with distinct mathematical foundations and practical implications for accuracy, ease of use, and robustness. This guide examines three principal categories: (1) methods based on the analytical, integrated forms of the Michaelis-Menten equation; (2) direct numerical integration of the system's differential equations; and (3) spline interpolation techniques that transform the dynamic problem into an algebraic one [29].

The selection of an appropriate method is not merely a technical detail but a critical component of rigorous data reporting. Consistency, reproducibility, and a clear understanding of methodological limitations are essential for comparing results across studies, especially in pre-clinical drug development where enzymatic efficiency and inhibition constants are key decision-making metrics.

Core Methodological Concepts and Mathematical Foundations

Analytical Integral Approaches

Analytical approaches utilize the exact, closed-form solution to the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation. For a simple one-substrate reaction, the differential equation is: [ -\frac{d[S]}{dt} = \frac{V{max}[S]}{KM + [S]} ] Integration yields the implicit form: [ [S]0 - [S]t + KM \ln\left(\frac{[S]0}{[S]t}\right) = V{max} t ] where ([S]0) is the initial substrate concentration and ([S]t) is the concentration at time (t) [35]. The explicit solution can be expressed using the Lambert W function: [ S = KM W\left( \frac{[S]0}{KM} \exp\left(\frac{[S]0 - V{max}t}{KM}\right) \right) ] where (W) is the Lambert W function [35].

Strengths: This method is computationally efficient and exact for ideal Michaelis-Menten systems, providing high-precision parameter estimates when the model perfectly matches the underlying mechanism.

Limitations: Its applicability is restricted to simple kinetic mechanisms with known, integrable rate laws. It cannot easily accommodate more complex scenarios like multi-substrate reactions, reversible inhibition, or enzyme instability without deriving new, often intractable, integrated equations.

Direct Numerical Integration

This approach directly solves the system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) describing the reaction without requiring an algebraic integral. For a given set of initial parameter guesses ((V{max}), (KM)), the ODE solver computes a predicted progress curve. An optimization algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) then iteratively adjusts the parameters to minimize the difference between the predicted curve and the experimental data.

Strengths: It is highly flexible and can be applied to virtually any kinetic mechanism, including complex multi-step models, by simply modifying the system of ODEs. It is the method of choice for non-standard mechanisms.

Weaknesses: The accuracy and convergence of the optimization are often highly dependent on the quality of the initial parameter estimates. It can converge to local minima, and the computational cost is higher than for analytical methods.

Spline-Based Algebraic Transformation

This innovative numerical approach bypasses both integration and ODE solving. The raw progress curve data is first smoothed using a cubic spline interpolation [29]. The spline provides a continuous, differentiable function (P(t)) representing product concentration.

The key insight is that the reaction velocity (v = dP/dt) can be obtained directly by analytically differentiating the spline function. This velocity can then be plugged into the differential form of the Michaelis-Menten equation: [ \frac{dP}{dt} = \frac{V{max} ([S]0 - P)}{KM + ([S]0 - P)} ] The problem is thus transformed from a dynamic optimization into an algebraic curve-fitting problem, where (V{max}) and (KM) are estimated by fitting the spline-derived ((v, [S])) pairs to the Michaelis-Menten equation [29].

Strengths: This method decouples the parameter estimation from initial value sensitivity, as the spline fitting and derivative calculation are performed independently. Case studies show it offers "great independence from initial values for parameter estimation" [29], providing robustness comparable to analytical methods but with wider applicability.

Methodological Comparison and Performance Evaluation

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of the three core approaches, based on comparative studies [29].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Progress Curve Methodologies

| Feature | Analytical Integral | Numerical Integration | Spline-Based Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Basis | Exact solution of integrated rate law. | Numerical solution of system of ODEs. | Algebraic fitting to derivatives from spline-smoothed data. |

| Parameter Sensitivity | Low sensitivity to initial guesses when model is correct. | High sensitivity to initial parameter estimates; risk of local minima. | Low dependence on initial values [29]. |

| Computational Cost | Low. | High (requires iterative ODE solving). | Medium (requires spline fitting and algebraic fit). |

| Model Flexibility | Low. Limited to simple, integrable mechanisms. | Very High. Can handle any mechanism definable by ODEs. | Medium-High. Can handle any mechanism where velocity can be expressed as a function of concentration. |

| Ease of Implementation | Straightforward if integrated equation is available. | Requires careful ODE solver and optimizer setup. | Requires robust spline fitting and differentiation routines. |

| Best Use Case | Ideal, simple Michaelis-Menten systems with high-quality data. | Complex, non-standard kinetic mechanisms. | Robust parameter estimation from noisy data or when good initial guesses are unavailable. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Implementation

General Data Acquisition Protocol for Progress Curve Analysis

- Assay Configuration: Perform continuous enzyme assays under controlled conditions (pH, temperature, ionic strength). Use a substrate concentration ideally near or above (K_M) to capture the full kinetic transient from initial velocity to substrate depletion.

- High-Resolution Data Collection: Collect signal (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence) at frequent time intervals to densely define the progress curve. High temporal resolution is critical for accurate derivative calculation in spline-based methods.

- Replication: Include replicates to assess experimental variability. Run a negative control (no enzyme) to correct for non-enzymatic substrate turnover or background signal drift.

- Data Formatting: Export time and signal data into a standard format (e.g., CSV). Ensure signal is converted to concentration units (e.g., µM product) using an appropriate calibration curve.

- Data Preprocessing: Load the experimental progress curve data ( (ti, Pi) ). Perform background subtraction using control data.

- Spline Interpolation: Fit a cubic smoothing spline to the ((t, P)) data. The smoothing parameter should be chosen to reduce noise without distorting the underlying kinetic trend. Tools like SciPy's

UnivariateSplineor MATLAB'scsapscan be used. - Derivative Calculation: Analytically differentiate the spline function to obtain the reaction velocity ( v(ti) = dP/dt|{t_i} ) at each data point.

- Substrate Calculation: Calculate the remaining substrate concentration at each point: ( S = [S]0 - P(ti) ).

- Algebraic Fitting: Perform a nonlinear least-squares fit of the paired data ( (S, v(ti)) ) to the Michaelis-Menten equation ( v = V{max}[S]/(KM + [S]) ). This step estimates (V{max}) and (K_M).

- Data Preparation: As in Step 4.1, obtain ( (ti, [S]i) ) data.

- Direct Fitting: Use a nonlinear regression algorithm to fit the data directly to the explicit integrated form involving the Lambert W function [35]: [ S = KM W\left( \frac{[S]0}{KM} \exp\left(\frac{[S]0 - V{max}t}{KM}\right) \right) ]

- Parameter Extraction: The fitting procedure directly outputs the best-fit estimates for (V{max}) and (KM).

Protocol for Direct Numerical Integration Fitting

- Define the ODE Model: Program the differential equation for the model (e.g.,

dS/dt = - (V_max * S) / (K_M + S)). - Simulate and Optimize: Use a computational environment (e.g., Python with SciPy, MATLAB, or specialized tools like KinTek [35]) to repeatedly: a. Solve the ODE for a given parameter set. b. Calculate the sum of squared residuals between the simulated and experimental curve. c. Adjust parameters via an optimization algorithm to minimize the residuals.

Visualization of Methodological Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of the two primary numerical approaches discussed.

Workflow for Two Primary Numerical Analysis Methods

The Spline-Based Transformation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent and Software Solutions

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Progress Curve Analysis [29] [35]

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Analysis | Key Feature / Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICEKAT | Software | Web-based tool for calculating initial rates and parameters from continuous assays. | Offers multiple fitting modes (Linear, Logarithmic, Schnell-Mendoza); valuable for teaching and standardizing analysis [35]. |

| DynaFit | Software | Fitting biochemical data to complex kinetic mechanisms. | Powerful for multi-step mechanisms beyond Michaelis-Menten [35]. |

| KinTek Explorer | Software | Simulating and fitting complex kinetic data, including progress curves. | Provides robust numerical integration and global fitting capabilities [35]. |

| GraphPad Prism | Software | General-purpose statistical and curve-fitting software. | Widely used; requires manual implementation of integrated equations or user-defined ODE models. |

| SciPy (Python) | Software Library | Provides algorithms for numerical integration (odeint), spline fitting (UnivariateSpline), and optimization (curve_fit). | Enables full customization of the spline-based or numerical integration pipeline. |

| High-Purity Substrate | Reagent | The reactant whose depletion is monitored. | Must be chemically stable and free of contaminants that could alter enzyme behavior. |

| Stable Enzyme Preparation | Reagent | The catalyst of interest. | Enzyme stability over the assay duration is critical for valid progress curve analysis. |

| Continuous Assay Detection Mix | Reagent | Components for real-time signal generation (e.g., NADH, chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates). | Signal must be linearly proportional to product concentration over the full assay range. |

Best Practice Recommendations for Reporting

To align with the broader thesis on best practices in enzyme kinetics reporting, researchers employing progress curve analysis should:

- Explicitly State the Method: Clearly report whether an analytical integral, numerical integration, or spline-based (or other) method was used. Cite the specific software or algorithm (e.g., "fitted to the integrated Michaelis-Menten equation using the Schnell-Mendoza method in ICEKAT v2.1").

- Document Initial Guesses and Convergence: For numerical methods, report the initial parameter estimates used and how convergence was assessed. This is crucial for reproducibility.

- Justify Model Selection: Provide justification for the chosen kinetic model (e.g., simple Michaelis-Menten vs. a model with inhibition). For spline or numerical methods, state the system of equations that was fitted.

- Include Quality of Fit Metrics: Always present goodness-of-fit indicators (e.g., R², sum of squared residuals, confidence intervals on parameters) alongside the final kinetic parameters ((V{max}), (KM), etc.).

- Provide Access to Raw Data: Where possible, make the raw progress curve time-series data available as supplementary material to enable re-analysis and validation.

Progress curve analysis stands as a efficient and information-rich technique for enzyme characterization. The choice between analytical, numerical integration, and spline-based approaches involves a trade-off between precision, robustness, and flexibility. Analytical integrals are excellent for simple systems, while numerical integration is indispensable for complex mechanisms. The spline-based approach emerges as a particularly robust middle ground, mitigating the common problem of initial value sensitivity while remaining applicable to a broad range of kinetic models [29].

Adopting these advanced computational methods and adhering to stringent reporting standards, as outlined in this guide, will enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and translational value of enzyme kinetics data in both basic research and applied drug development contexts.