Mastering Vmax and Km: Advanced Estimation Techniques for Enzyme Kinetics in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Vmax and Km estimation in enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Mastering Vmax and Km: Advanced Estimation Techniques for Enzyme Kinetics in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Vmax and Km estimation in enzyme kinetics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of Michaelis-Menten kinetics, practical experimental and computational methods for parameter determination, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing assays, and advanced techniques for validation and comparative analysis. The content integrates recent advancements, including Bayesian estimation, optimized experimental designs, and applications in predicting drug clearance and bioavailability, to support accurate and efficient research in drug discovery and development.

The Fundamentals of Vmax and Km: Core Concepts in Enzyme Kinetics

Foundational Definitions and Core Biological Meanings

The parameters Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant) are the principal quantitative descriptors in enzyme kinetics, derived from the Michaelis-Menten model first proposed in 1913 [1]. They provide an essential framework for understanding how enzymes function as biological catalysts, which accelerate biochemical reactions by lowering the activation energy required [2] [3].

Vmax is defined as the maximum rate of reaction achievable when all available enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate [1] [2]. It represents a plateau in the reaction velocity, where further increases in substrate concentration yield no increase in rate. Vmax is directly proportional to the total enzyme concentration ([ET]) and fundamentally reflects the catalytic capacity of the enzyme when substrate binding is not rate-limiting. It is mathematically defined as *Vmax = k₂[ET], where *k₂ (often denoted k_cat) is the catalytic rate constant for the conversion of the enzyme-substrate complex to product [4] [5].

Km, the Michaelis constant, is defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vmax [1] [6]. It is a composite constant expressed in terms of microscopic rate constants: Km = (k₋₁ + k₂)/k₁, where k₁ and k₋₁ are the forward and reverse rate constants for substrate binding, and k₂ is the catalytic rate constant [4] [3]. Biologically, Km provides an inverse measure of the enzyme's apparent affinity for its substrate: a low Km value indicates high affinity, meaning the enzyme achieves half-maximal efficiency at low substrate concentrations, while a high Km indicates low affinity [1] [2].

Table 1: Core Definitions and Biological Interpretations of Vmax and Km

| Parameter | Mathematical Definition | Biological Meaning | Interpretation of Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax | Vmax = k_cat · [E_T] |

Maximum catalytic capacity when enzyme is saturated. | High Vmax = High turnover capacity. Dependent on enzyme concentration. |

| Km | Km = (k_₋₁ + k_cat)/k_₁ |

Substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity (Vmax/2). | Low Km = High apparent substrate affinity. High Km = Low apparent affinity. |

Kinetic Significance in Catalytic Efficiency

The individual parameters Vmax and Km are most informative when considered together. Their ratio, k_cat/Km, known as the specificity or catalytic efficiency constant, is a critical metric for evaluating an enzyme's performance under non-saturating, physiologically relevant substrate concentrations [3] [7]. This constant has units of M⁻¹s⁻¹ and represents the enzyme's effectiveness in converting substrate to product when substrate is limiting.

A high k_cat/Km indicates high efficiency, resulting from a combination of a fast turnover rate (high k_cat, reflected in Vmax) and tight substrate binding (low Km) [7]. For example, the enzyme carbonic anhydrase has a k_cat/Km approaching the diffusion-controlled limit (~10⁸ M⁻¹s⁻¹), denoting a near-perfect catalyst [6]. This efficiency has direct biological implications: enzymes with high catalytic efficiency for specific substrates can effectively outcompete other enzymes for a shared, limited substrate pool within a cell [8].

The relationship between velocity (v), substrate concentration ([S]), Vmax, and Km is described by the fundamental Michaelis-Menten equation:

v = (Vmax [S]) / (Km + [S]) [2] [3]

This equation generates a rectangular hyperbola when reaction velocity is plotted against substrate concentration. The plot reveals two key kinetic regimes: 1) First-order kinetics at low [S] (where [S] << Km), where velocity is approximately proportional to substrate concentration, and 2) Zero-order kinetics at high [S] (where [S] >> Km), where velocity is independent of [S] and approaches Vmax [2] [6].

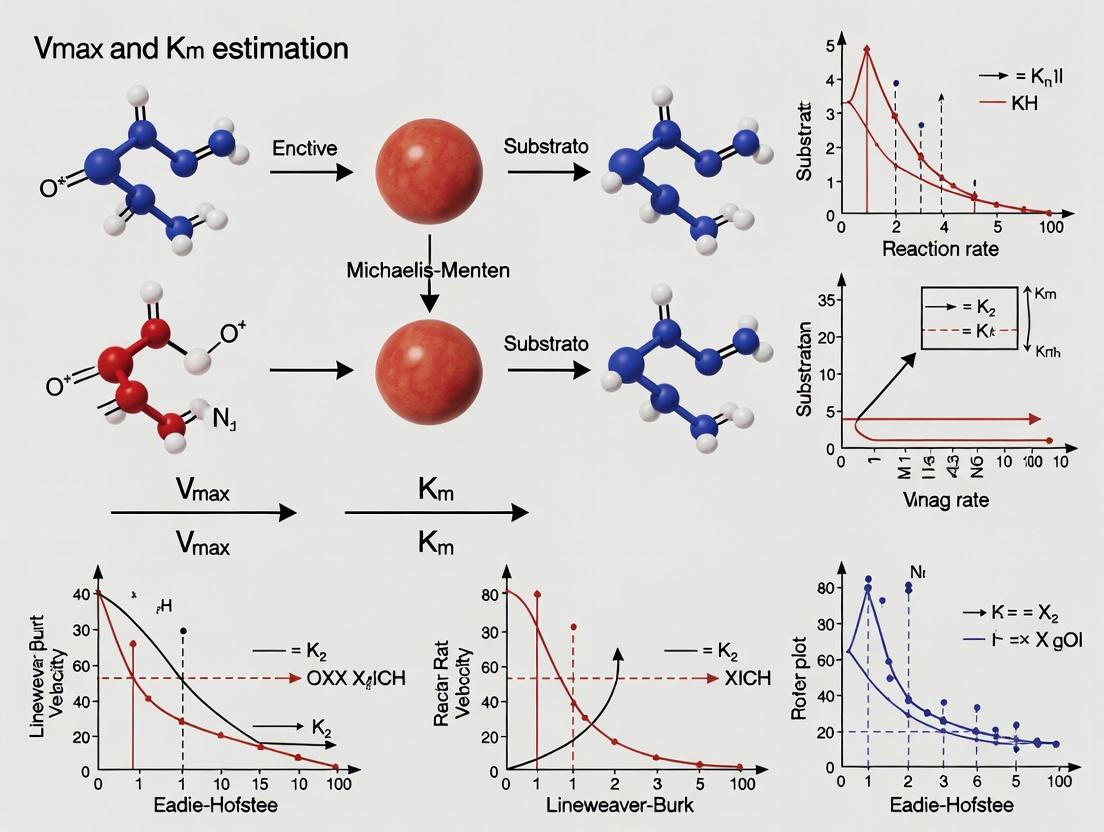

Diagram 1: Michaelis-Menten Enzyme Kinetic Pathway. This diagram illustrates the fundamental steps of enzyme catalysis, highlighting the microscopic rate constants (k₁, k₋₁, k_cat) that underlie the macroscopic parameters Vmax and Km [4] [5] [3].

The Research Context: Reliability and Interpretation of Parameters

Within the broader thesis of Vmax and Km estimation research, a paramount challenge is ensuring the reliability, accuracy, and appropriate interpretation of these parameters [8]. They are not universal constants but are dependent on experimental conditions such as temperature, pH, ionic strength, and buffer composition [8]. Consequently, a value reported in the literature is only valid for the specific conditions under which it was measured.

Key issues in research include:

- Assay Conditions: Many historical studies use conditions optimized for assay convenience rather than physiological relevance, complicating the integration of data for systems biology modeling [8].

- Parameter Variability: Estimates of Vmax and Km can show higher variability than derived parameters like intrinsic clearance (CLint), particularly when substrate turnover is low [9].

- Data Sources and Quality: Researchers often source parameters from databases like BRENDA or SABIO-RK [8]. The emerging STRENDA (STandards for Reporting ENzymology DAta) guidelines aim to improve reporting standards, requiring detailed methodological metadata to facilitate data assessment and reuse [8].

Furthermore, the interpretation of Km as a simple measure of affinity is most straightforward for classical, single-substrate Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Mechanisms become more complex with multi-substrate reactions (e.g., ordered-sequential, ping-pong mechanisms), allosteric enzymes, and membrane transporters [4] [8]. For instance, in transporter kinetics (e.g., solute carriers like ASBT or PEPT1), a simple Michaelis-Menten model is often an oversimplification of a multi-state translocation cycle involving unidirectional steps [4]. In such systems, Km and Vmax are complex functions of multiple microscopic rate constants governing binding, translocation, and release [4].

Table 2: Impact of Key Experimental Variables on Km and Vmax Estimates

| Experimental Variable | Typical Effect on Km | Typical Effect on Vmax | Notes for Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Concentration | None (Theoretically independent) | Linear increase | Vmax must be normalized (e.g., per mg protein) for comparison across studies [6]. |

| Temperature | Can increase or decrease | Usually increases to an optimum | Changes reflect alterations in rate constants and enzyme stability [8]. |

| pH | Can change significantly | Usually has a clear optimum | Alters ionization states of active site residues, affecting binding (Km) and catalysis (Vmax) [2] [8]. |

| Competitive Inhibitor | Increases (apparent Km) | No change | Classic diagnostic pattern. Inhibitor competes with substrate for the active site [1] [2]. |

| Non-competitive Inhibitor | No change | Decreases | Inhibitor binds at a site other than the active site, reducing catalytic rate [1] [2]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Parameter Estimation

Accurate determination of Vmax and Km requires measuring the initial reaction rates (v₀) at a series of substrate concentrations ([S]) while keeping enzyme concentration constant [6] [8]. The "initial rate" is critical to avoid complications from product inhibition, substrate depletion, or enzyme inactivation.

Classical Protocol (Substrate Saturation Curve):

- Prepare a set of reaction mixtures with a fixed, known concentration of enzyme.

- In each mixture, use a different concentration of substrate, typically spanning a range from well below to well above the expected Km (e.g., 0.2Km to 5Km).

- Initiate the reaction and measure the amount of product formed (or substrate consumed) over a short, early time period where the relationship is linear.

- Plot the initial velocity (v₀) against substrate concentration ([S]) to obtain the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten curve.

- Use non-linear regression to fit the data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation, which is the preferred modern method for extracting Vmax and Km [9].

Linear Transformation (Lineweaver-Burk Plot): The hyperbolic relationship can be linearized by plotting 1/v₀ against 1/[S]. This Lineweaver-Burk plot yields a straight line where the y-intercept is 1/Vmax, the x-intercept is -1/Km, and the slope is Km/Vmax [2]. While historically important and useful for visualizing inhibition patterns (competitive, non-competitive), this method can distort experimental error and is less statistically reliable for parameter estimation than non-linear regression [2].

Advanced and Optimized Protocols: Recent research focuses on optimizing experimental design for efficiency and reliability, particularly in drug discovery. The Optimal Design Approach (ODA) uses multiple substrate starting concentrations with strategically chosen late sampling time points. This method, validated against richer "multiple depletion curves" methods, provides reliable estimates of Vmax, Km, and intrinsic clearance (CLint) even with a limited total number of samples [9].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Estimating Vmax and Km. This flowchart outlines the standard process from experiment initiation to parameter estimation, highlighting the two primary analysis pathways [6] [9].

Advanced Applications and Biological Scaling

The principles of Vmax and Km extend beyond soluble enzymes to critical applications in drug development and systems biology.

In pharmacology and toxicology, these parameters are used to characterize the metabolism of drugs by cytochrome P450 enzymes and their transport by membrane carriers [4] [9]. Determining the Km for a drug's metabolism is essential for assessing the risk of non-linear pharmacokinetics, where saturation of metabolic pathways at clinical doses leads to disproportionate increases in drug exposure [9].

From an evolutionary and ecological perspective, fundamental scaling relationships exist between kinetic parameters and cellular physiology. Research on phototrophic and chemotrophic microorganisms reveals a trade-off between Vmax and Km, often following power-law relationships with cell size [10]. Generally, larger cells have a higher maximum uptake capacity (Vmax), but this is associated with a higher Km (lower affinity). This Vmax-Km trade-off is a key constraint in microbial ecology and modeling, influencing competition for nutrients in environmental systems [10].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Source can be recombinant or isolated from tissue. | Activity and concentration must be known and consistent. Stability under assay conditions is critical [6] [8]. |

| Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme. | High purity. A range of concentrations must be prepared from a stock solution. Use of physiologically relevant substrates is preferred [8]. |

| Detection System | To quantify product formation or substrate depletion (e.g., spectrophotometer, fluorimeter, LC-MS/MS). | Must be specific, sensitive, and allow for rapid, continuous or stopped-point measurement [9]. |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength. | Choice of buffer (e.g., phosphate, Tris, HEPES) can affect enzyme activity and stability. Should mimic physiological conditions when possible [8]. |

| Cofactors / Cations | Required for activity of many enzymes (e.g., NADH, Mg²⁺). | Must be included at saturating, non-inhibitory concentrations in all reaction mixtures [8]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes | A common in vitro system for studying drug metabolism kinetics. | Contains native cytochrome P450 enzymes and other drug-metabolizing enzymes. Protein content is normalized [9]. |

Historical Context and Original Derivation

The foundational work of Leonor Michaelis and Maud Leonora Menten was published in their 1913 paper "Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung," which studied the enzyme invertase catalyzing sucrose hydrolysis into glucose and fructose [11]. Their research was conducted in Berlin, where Menten worked as a research assistant after earning her medical degree. Their experimental goal was to test the hypothesis that enzyme catalysis proceeds through the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex, with the reaction rate proportional to the concentration of this complex [11].

Michaelis and Menten recognized that product inhibition complicated kinetic analysis, a problem previously noted by Victor Henri. To circumvent this, they pioneered the initial velocity measurement approach, following the reaction only during the brief initial period where product influence was negligible [11]. They monitored the invertase-catalyzed reaction at various sucrose concentrations by measuring optical rotation changes over time, tracking reactions to completion. Their data analysis assumed equilibrium binding between sucrose and enzyme, postulating the reaction rate was proportional to enzyme-substrate complex concentration [11].

Surprisingly, Michaelis and Menten's original analysis was more comprehensive than typically recognized. Beyond initial velocity measurements, they fitted full time-course data to integrated rate equations incorporating product inhibition. They derived a single global constant representing all their data—not the Michaelis constant (Kₘ), but rather Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ (the specificity constant multiplied by enzyme concentration) [11]. Their graphical analysis employed an innovative approach: plotting rate versus logarithm of substrate concentration, analogous to Henderson-Hasselbalch equations, rather than using the now-common double reciprocal plot developed later by Lineweaver and Burk [11].

Mathematical Foundations and Core Assumptions

The canonical Michaelis-Menten model describes enzyme kinetics through a fundamental mechanism where enzyme (E) binds substrate (S) to form a complex (ES), which then yields product (P) while regenerating the free enzyme [12]:

The derivation of the Michaelis-Menten equation relies on several critical assumptions that remain essential for proper application of the model [13]:

Assumption 1: No product is present at the reaction start, allowing neglect of the reverse reaction E + P → ES during initial rate measurements [13].

Assumption 2: The steady-state approximation applies, where the rate of ES complex formation equals its rate of breakdown (dissociation plus product formation) [13].

Assumption 3: Enzyme concentration is much lower than substrate concentration ([E] << [S]), ensuring minimal substrate depletion during measurement [13].

Assumption 4: Only initial velocity is measured, maintaining [P] ≈ 0 and [S] approximately constant [13].

Assumption 5: Enzyme exists either as free enzyme or ES complex, with total enzyme concentration [E]ₜ = [E] + [ES] [13].

Under these assumptions, the Michaelis-Menten equation is derived:

Where:

v= initial reaction velocityVₘₐₓ= maximum velocity (k꜀ₐₜ × [E]ₜ)[S]= substrate concentrationKₘ= Michaelis constant = (k₋₁ + k꜀ₐₜ)/k₁

The equation produces a rectangular hyperbola where velocity asymptotically approaches Vₘₐₓ as substrate concentration increases [14]. The Kₘ represents the substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity and provides a measure of enzyme-substrate affinity (lower Kₘ indicates higher affinity) [12].

Table 1: Historical vs. Modern Interpretation of Michaelis-Menten Parameters

| Parameter | Original 1913 Interpretation | Modern Interpretation | Biological/Experimental Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vₘₐₓ | Maximum velocity of fission during initial phase [11] | Maximum reaction rate at saturating substrate: Vₘₐₓ = k꜀ₐₜ[E]ₜ [12] | Determines enzyme's catalytic capacity; proportional to enzyme concentration |

| Kₘ | Dissociation constant for enzyme-substrate complex (Kₛ) [11] | Substrate concentration at half-maximal velocity: Kₘ = (k₋₁ + k꜀ₐₜ)/k₁ [12] | Measures apparent enzyme-substrate affinity; lower Kₘ indicates higher affinity |

| k꜀ₐₜ | Not explicitly defined | Turnover number: molecules converted per active site per unit time [12] | Intrinsic catalytic efficiency of enzyme |

| Specificity Constant (k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ) | Global constant derived from full time-course analysis [11] | Measure of catalytic efficiency and specificity for competing substrates [12] | Determines enzyme selectivity under physiological substrate concentrations |

Evolution of Parameter Estimation Methods

The methodology for estimating Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ has evolved significantly from Michaelis and Menten's original graphical approach to contemporary computational methods. Their innovative but laborious technique involved plotting reaction velocity against the logarithm of substrate concentration, then normalizing the curve to achieve a specific slope (0.576) at half-maximal velocity to extract parameters [11].

Linear Transformation Methods: The 1934 Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal plot (1/v vs. 1/[S]) became the standard linearization method for decades, despite its susceptibility to error propagation with imperfect data [11]. Other linear transformations include Eadie-Hofstee (v vs. v/[S]) and Hanes-Woolf ([S]/v vs. [S]) plots, each with different error distribution characteristics [12].

Modern Computational Approaches: Current parameter estimation employs nonlinear regression to directly fit the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation to experimental data, providing more statistically reliable parameter estimates [15]. Bayesian inference methods have emerged as powerful alternatives, particularly when using models derived with the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQ model) rather than the standard approximation (sQ model) [15]. The tQ model remains accurate under a wider range of conditions, especially when enzyme concentration is not negligible compared to substrate [15].

Optimal Experimental Design: Contemporary research emphasizes designing experiments to maximize parameter identifiability. For progress curve assays, starting with substrate concentrations near Kₘ is recommended, while for initial velocity assays, substrate concentrations should span from well below to well above Kₘ [15]. Recent studies demonstrate that using multiple starting concentrations with limited sampling points can yield reliable parameter estimates comparable to more data-intensive methods [9].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Parameter Estimation Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis-Menten Original (1913) | Rate vs. log[S] plot with normalization to slope 0.576 at v/2 [11] | Comprehensive analysis of full time-course data with product inhibition [11] | Laborious graphical procedure; requires normalization step | Historical interest; understanding original derivation |

| Lineweaver-Burk (1934) | Double reciprocal plot: 1/v vs. 1/[S] yields linear relationship [11] | Linearization simplifies parameter estimation visually | Error propagation magnifies uncertainties; statistically flawed | Quick visual assessment (though discouraged for final analysis) |

| Nonlinear Regression | Direct fitting of v = Vₘₐₓ[S]/(Kₘ + [S]) to experimental data | Statistically robust; proper error weighting; no data transformation | Requires computational tools; initial parameter estimates needed | Standard modern approach for accurate parameter estimation |

| Bayesian Inference with tQ Model | Uses total quasi-steady-state approximation model within Bayesian framework [15] | Accurate even when [E] ≈ [S]; identifies optimal experimental designs | Computationally intensive; requires statistical expertise | Challenging conditions where standard assumptions may not hold |

Contemporary Experimental Protocols

Modern enzyme kinetics research employs sophisticated protocols for reliable estimation of Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where these parameters inform drug metabolism predictions.

Initial Velocity Assays: The traditional approach measures initial reaction rates at varying substrate concentrations. Protocols require careful control of conditions (pH, temperature, ionic strength) and use of appropriate detection methods (spectrophotometric, fluorometric, chromatographic) [16]. Each substrate concentration is tested in triplicate with appropriate controls to ensure reliability.

Progress Curve Assays: This approach fits the entire time-course of product formation or substrate depletion to integrated rate equations. Modern implementations use computational fitting to extract parameters from fewer data points. A recent study demonstrated that an optimal design approach using multiple starting concentrations with late sampling points provides reliable estimates of intrinsic clearance (CLᵢₙₜ), Vₘₐₓ, and Kₘ with minimal samples [9].

Specific Protocol for Metabolic Studies: In drug development, enzyme kinetic parameters for cytochrome P450 enzymes are typically determined using human liver microsomes. A validated protocol involves [9]:

- Incubating test compounds at multiple starting concentrations (typically 6-8 concentrations spanning expected Kₘ range)

- Sampling at optimized late time points (reducing number of samples while maintaining information content)

- Analyzing samples via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Fitting substrate depletion data to appropriate kinetic models using nonlinear regression

Validation Studies: Comparative studies show that optimal design approaches yield parameter estimates within 2-fold of values obtained from more intensive sampling methods in >90% of cases for CLᵢₙₜ and >80% for Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ [9]. These methods are particularly valuable when assessing potential nonlinear metabolism risks in vivo.

Advanced Applications and Modern Interpretations

Beyond basic enzyme characterization, Michaelis-Menten kinetics finds application in diverse fields with evolving interpretations of Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ.

Drug Discovery and Development: In pharmacokinetics, Kₘ values determine potential nonlinear metabolism at therapeutic concentrations. Drugs administered at doses producing concentrations approaching or exceeding Kₘ may exhibit dose-dependent clearance. Accurate estimation of these parameters enables prediction of in vivo behavior from in vitro data [9].

Microbial Ecology and Systems Biology: Michaelis-Menten parameters describe nutrient uptake in microorganisms, with studies revealing relationships between cell size and kinetic parameters. Research indicates Vₘₐₓ scales with cell surface area (approximately Vₘₐₓ ∝ cell volume²ᐟ³), while Kₘ shows trade-off relationships with Vₘₐₓ [10]. Chemotrophic organisms generally exhibit higher mass-specific Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ values than phototrophs [10].

Single-Molecule Enzymology: Advanced techniques now probe enzyme kinetics at the single-molecule level, revealing heterogeneity and dynamic disorder not apparent in ensemble measurements. These studies sometimes show deviations from classical Michaelis-Menten behavior, prompting development of more sophisticated models.

Limitations and Extensions: The classical equation assumes homogeneity of enzyme populations, absence of allosteric effects, and single-substrate reactions. Extensions include models for multi-substrate reactions, allosteric enzymes (Hill equation), and inhibition patterns (competitive, noncompetitive, uncompetitive). Recent work emphasizes conditions where the standard quasi-steady-state approximation fails and total quasi-steady-state approximation models are required [15].

Table 3: Representative Enzyme Kinetic Parameters Across Biological Systems

| Enzyme | Kₘ (M) | k꜀ₐₜ (s⁻¹) | k꜀ₐₜ/Kₘ (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 | Proteolytic enzyme; intermediate affinity, moderate turnover [12] |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ | Stomach protease; high affinity, moderate turnover [12] |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ | RNA degradation; moderate affinity, high turnover [12] |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ | CO₂ hydration; moderate affinity, extremely high turnover [12] |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ | Citric acid cycle; very high affinity, high turnover [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Michaelis-Menten Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | Catalytic agent whose kinetics are being characterized | Source, purity, and specific activity must be documented; e.g., commercially available invertase [11] |

| Substrate Solutions | Varied concentrations to establish saturation curve | Prepare in reaction buffer; purity critical; e.g., sucrose solutions for invertase [11] |

| Reaction Buffer | Maintains optimal pH and ionic conditions | Typically includes pH buffer, salts; e.g., acetate buffer for invertase [11] |

| Detection System | Monitors reaction progress over time | Spectrophotometer, polarimeter (for optical rotation), fluorometer, or LC-MS/MS [9] |

| Stop Solution | Halts reaction at precise time points | Acid, base, or inhibitor; timing critical for initial rate measurements |

| Product Standards | Quantification reference for calibration curves | Pure product for standard curve generation |

| Inhibition Controls | Validates specificity of observed activity | Specific inhibitors, heat-inactivated enzyme, no-enzyme controls |

| Microsomal Preparations | Drug metabolism studies (pharmaceutical applications) | Human liver microsomes for cytochrome P450 kinetics [9] |

| Internal Standards | Mass spectrometry quantification (pharmaceutical applications) | Stable isotope-labeled analogs of analytes; e.g., 5,5-diethyl-1,3-diphenyl-2-imminobarbituric acid [9] |

The Michaelis-Menten equation remains a cornerstone of enzymology a century after its introduction, testament to the robustness of its fundamental insights. Michaelis and Menten's original work established not only the mathematical relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity but also key experimental approaches including initial velocity measurements and consideration of product inhibition [11].

Modern research continues to refine parameter estimation methods, with Bayesian approaches and optimal experimental designs improving accuracy while reducing experimental burden [9] [15]. The interpretation of Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ has expanded from basic enzyme characterization to applications in drug development, microbial ecology, and systems biology [9] [10].

Future directions include integration of single-molecule observations, development of more comprehensive models for complex enzyme systems, and application of machine learning to kinetic parameter estimation. The enduring relevance of the Michaelis-Menten equation lies in its elegant simplification of complex biochemical processes while providing a framework that can be extended and refined as experimental capabilities advance.

The hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity, formalized by the Michaelis-Menten equation, remains a cornerstone for quantifying enzyme behavior and inhibitor interactions in biochemical and pharmacological research [17]. This relationship is described by the equation V₀ = (Vₘₐₓ × [S]) / (Kₘ + [S]), where V₀ is the initial reaction velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, Vₘₐₓ is the maximum velocity, and Kₘ is the Michaelis constant [18]. Within the broader thesis of Vmax and Km estimation research, precise determination of these parameters is not merely an academic exercise but a critical endeavor with direct implications for understanding metabolic pathways, characterizing drug metabolism, and designing targeted therapies [9]. The half-maximal velocity, defined by the point where V₀ = Vₘₐₓ/2, provides the operational definition of Kₘ, serving as a quantitative measure of an enzyme's apparent affinity for its substrate [17] [19]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to interpreting these fundamental kinetic curves and the experimental methodologies employed for robust parameter estimation in contemporary research.

Deconstructing the Hyperbolic Curve: A Graphical Primer

The classic Michaelis-Menten plot graphs reaction velocity (V₀) against substrate concentration ([S]), yielding a characteristic hyperbolic curve [17]. This shape arises from the underlying mechanism of enzyme catalysis, where the formation of an enzyme-substrate (ES) complex is a prerequisite for product formation [20].

Key Graphical Features and Interpretations:

- The Initial Linear Region: At low [S] where [S] << Kₘ, the equation simplifies to V₀ ≈ (Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ)[S]. Velocity increases approximately linearly with [S], indicating that most enzyme active sites are unoccupied. The slope of this region is Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ [20].

- The Curvilinear Transition Region: As [S] approaches and passes Kₘ, the relationship becomes nonlinear. The Kₘ is defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is half of Vₘₐₓ [17]. A lower Kₘ value indicates a higher apparent affinity of the enzyme for the substrate, as half-saturation is achieved at a lower substrate concentration [18].

- The Plateau Region (Vₘₐₓ): At high [S] where [S] >> Kₘ, the equation simplifies to V₀ ≈ Vₘₐₓ. The curve asymptotically approaches a maximum velocity, signifying that all available enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate. At this point, the reaction rate is zero-order with respect to substrate and depends solely on enzyme concentration and its intrinsic turnover number (k_cat) [20] [19]. Vₘₐₓ can only be increased by increasing the concentration of active enzyme [18].

It is critical to distinguish this hyperbolic kinetics, typical of Michaelis-Menten enzymes, from sigmoidal kinetics. Sigmoidal curves are characteristic of allosteric enzymes with multiple interacting subunits, where substrate binding at one site increases the affinity of other sites, leading to cooperative behavior [21].

Table 1: Key Parameters Derived from Michaelis-Menten Hyperbolic Curves

| Parameter | Symbol | Graphical Determination | Biochemical Meaning | Impact of Higher Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Velocity | Vₘₐₓ | The asymptotic plateau of the hyperbola [17]. | The maximum reaction rate when enzyme is fully saturated. Limited by k_cat and [Enzyme]. | Higher maximum catalytic throughput. |

| Michaelis Constant | Kₘ | Substrate concentration at Vₘₐₓ/2 [17]. | Apparent affinity of enzyme for substrate. Approximates the dissociation constant (Kd) for ES complex when kcat << k_off [18]. | Lower apparent substrate affinity. |

| Catalytic Efficiency | k_cat/Kₘ | Derived parameter; slope of linear region (Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ) [17]. | Overall efficiency of an enzyme combining substrate binding (1/Kₘ) and catalysis (k_cat). | More efficient enzyme at low substrate concentrations. |

| Turnover Number | k_cat | Calculated as Vₘₐₓ / [E_total] [19]. | Number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time. | Faster conversion of substrate to product at saturation. |

Methodologies for Parameter Estimation: From Classic Plots to Modern Assays

Accurate estimation of Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ is foundational. Researchers employ various experimental and analytical strategies, each with strengths and limitations.

Direct Fitting and Linear Transformations

The most straightforward method is to perform nonlinear regression to fit the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation directly to velocity vs. [S] data [15]. Historically, linear transformations like the Lineweaver-Burk plot (double-reciprocal plot: 1/V vs. 1/[S]) were used to visualize data and extract parameters [22].

- Y-intercept = 1/Vₘₐₓ

- X-intercept = -1/Kₘ

- Slope = Kₘ/Vₘₐₓ While useful for illustrative purposes and identifying inhibition types (competitive, non-competitive), these plots can distort experimental error and are less reliable for accurate parameter estimation than direct nonlinear fitting [22].

Progress Curve and Substrate Depletion Assays

Modern approaches often utilize progress curve or substrate depletion assays, which can be more efficient with fewer data points. Instead of measuring initial velocities at multiple substrate concentrations, these methods follow product formation or substrate loss over time from one or several starting concentrations [9] [15].

A significant advancement in this area is the Optimal Design Approach (ODA) evaluated in contemporary research. This method uses multiple starting substrate concentrations (C₀) with strategically chosen late sampling time points (tₛ) [9]. When experimentally evaluated against a reference method (the multiple depletion curves method, MDCM) using human liver microsomes and 30 compounds, the ODA showed strong agreement: >90% of intrinsic clearance (CLᵢₙₜ) estimates and >80% of Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ estimates were within a 2-fold difference [9]. This method is particularly valuable for assessing nonlinear metabolism risk in drug discovery [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Key Methodologies for Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ Estimation

| Method | Core Principle | Typical Experimental Design | Key Advantages | Key Limitations/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Velocity (Classic) | Measures V₀ at a range of fixed [S] points. | Multiple reactions, each at a different [S], measured at early time points [17]. | Conceptually simple, directly visualizes hyperbola. Widely understood. | Can be resource-intensive (many samples). Requires careful assurance of initial rate conditions. |

| Substrate Depletion (Progress Curve) | Fits timecourse of substrate loss to kinetic model. | Monitors [S] over time from one or more starting C₀ [9]. | Can be more efficient with fewer data points. Provides estimates of CLᵢₙₜ directly. | Requires an accurate analytical method (e.g., LC-MS/MS). More complex data analysis. |

| Optimal Design (ODA) | A progress curve method using multiple C₀ with optimized late tₛ. | A limited number of samples taken at strategic late time points from several different C₀ [9]. | Efficient with limited samples. Good for identifying nonlinearity risk. Reliable agreement with reference methods [9]. | Design requires understanding of expected parameter space. |

| Bayesian tQ Model Fitting | Uses the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) model for fitting. | Fits progress curve data to the more general tQ model (Equation 2) [15]. | Accurate even when enzyme concentration is not low ([E] ~ or > [S] or Kₘ). Overcomes bias of standard MM equation in vivo [15]. | Computationally more intensive. Requires specialized software/packages. |

Advanced Computational: The Bayesian tQ Model

A critical limitation of the standard Michaelis-Menten equation is its requirement that total enzyme concentration [Eₜ] be much lower than Kₘ + [Sₜ] for accuracy [15]. This condition often does not hold in vivo. The total QSSA (tQ) model provides a more robust framework valid over wider concentration ranges [15]. A Bayesian inference approach using this tQ model can yield unbiased estimates of k_cat and Kₘ from progress curve data without restrictive assumptions about enzyme concentration, enabling more accurate in vitro to in vivo extrapolation [15].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Kinetic Parameter Estimation (85 chars)

Factors Influencing Kinetic Parameters and Experimental Design

Accurate interpretation requires awareness of factors that alter Vₘₐₓ and Kₘ.

- Enzyme Concentration: Vₘₐₓ is directly proportional to the concentration of active enzyme ([E]); doubling [E] doubles Vₘₐₓ. In contrast, Kₘ is theoretically independent of [E], as it is an intensive property of the enzyme-substrate pair [19].

- Temperature and pH: Both affect enzyme structure and activity. They typically alter Vₘₐₓ by changing k_cat and can also affect Kₘ by altering substrate binding affinity. Each enzyme has an optimal temperature and pH [19].

- Inhibitors: The hallmark of different inhibitor types is their distinctive effect on the hyperbolic curve and its linear transformations [22].

- Competitive Inhibitors: Increase apparent Kₘ; no change to Vₘₐₓ.

- Non-competitive Inhibitors: Decrease Vₘₐₓ; no change to Kₘ.

- Uncompetitive Inhibitors: Decrease both Vₘₐₓ and apparent Kₘ.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Typical Source/Example | Function in Experiment | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Enzyme or Tissue Fractions | Commercial vendors; Human liver microsomes (HLM) [9]. | Source of the enzyme activity being characterized. | Purity, activity lot-to-lot variability, relevance to physiological system (e.g., HLM for cytochrome P450 studies). |

| Substrate Library | Traditional probe substrates (e.g., midazolam, diclofenac) [9]; new molecular entities. | The molecule whose conversion is measured. | Solubility, specificity for the target enzyme, availability of analytical detection method. |

| Co-factors | NADPH (for P450s), Mg²⁺, ATP. | Essential for the catalytic activity of many enzymes. | Stability in buffer, required concentration for saturation. |

| Analytical Detection System | Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [9]. | Quantifies substrate depletion or product formation with high sensitivity and specificity. | Sensitivity, dynamic range, freedom from matrix interference. |

| Incubation Buffer | Phosphate, Tris, HEPES buffers. | Provides stable pH and ionic environment for the enzymatic reaction. | pH optimum, chemical compatibility with enzyme and substrate. |

| Internal Standard | Stable isotope-labeled analog of substrate/product [9]. | Added to samples prior to analysis to correct for variations in sample processing and instrument response. | Should be chemically identical to analyte except for mass label. |

| Inhibitors/Activators | Chemical inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies. | Used to characterize enzyme selectivity or mechanism. | Specificity, potency, solubility. |

Diagram 2: Enzyme Kinetic Reaction Mechanism (63 chars)

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

The field of enzyme kinetics is moving beyond simple Michaelis-Menten analysis. Key frontiers include:

- In Vivo Kinetics: Recognizing that intracellular enzyme concentrations can be high, invalidating the standard Michaelis-Menten assumption. The tQSSA and Bayesian approaches are crucial for bridging in vitro and in vivo data [15].

- Parameter Identifiability: A major challenge is that parameters k_cat and Kₘ can be highly correlated in progress curve fits, leading to uncertainty. Optimal experimental design (like ODA) and advanced statistical inference are required to ensure reliable, unique estimates [9] [15].

- Automation and High-Throughput: In drug discovery, methods must balance thoroughness with resource constraints. Efficient designs like the ODA that use a limited number of samples are increasingly valuable for early-stage compound profiling [9].

Diagram 3: Pathways from Data to Kinetic Parameters (77 chars)

Interpreting the hyperbolic velocity-substrate curve and its defining parameter, the half-maximal velocity (Kₘ), is fundamental to quantitative biochemistry and pharmacology. While the Michaelis-Menten framework provides an essential model, contemporary research demands more sophisticated methodologies like substrate depletion assays, optimal experimental design (ODA), and Bayesian fitting with the tQ model to address challenges of parameter identifiability and in vivo extrapolation [9] [15]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate experimental and analytical strategy is critical for generating reliable kinetic parameters that accurately predict enzyme behavior in complex biological systems, ultimately guiding the development of safer and more effective therapeutics.

The Role of the Enzyme-Substrate Complex and the Steady-State Assumption in Kinetic Theory

1. Introduction: The Foundation of Enzyme Kinetics in Modern Research

The quantitative analysis of enzyme catalysis, centered on the accurate estimation of the kinetic parameters Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant), is a cornerstone of biochemistry, pharmacology, and drug development. These parameters are not abstract numbers; they provide a rigorous, quantitative framework for understanding molecular efficiency, substrate affinity, and inhibitor potency. This understanding is predicated on two interconnected conceptual pillars: the formation of the enzyme-substrate (ES) complex as the central catalytic intermediate and the steady-state assumption that allows this dynamic process to be described by a workable mathematical model. The Michaelis-Menten equation, derived from these concepts, remains the fundamental model for characterizing enzyme activity [12] [5]. The ongoing refinement of Vmax and Km estimation methodologies, from classical linearizations to modern nonlinear regression and computational simulations, represents the practical application of this theory. This guide examines the structural and kinetic principles of the ES complex, details the derivation and implications of the steady-state assumption, and frames this classical theory within the context of contemporary, high-precision parameter estimation research essential for drug discovery and enzyme engineering.

2. The Enzyme-Substrate Complex: Structural and Energetic Basis of Catalysis

The enzyme-substrate complex is the transient, high-energy intermediate in which the substrate is converted to product. Its formation and properties are the structural determinants of Km and Vmax.

Active Site Architecture and Specificity: The active site is a specialized three-dimensional pocket within the enzyme where catalysis occurs. It is composed of amino acid residues that create a unique chemical environment (e.g., hydrophobic, charged, acidic) complementary to the transition state of the reaction [23] [24]. This complementarity is dynamic. The historical "lock-and-key" model has been largely supplanted by the induced fit model, where substrate binding induces conformational changes in the enzyme to achieve an optimal catalytic alignment [23] [25]. This precise arrangement is crucial for the kinetic parameter of specificity (kcat/Km).

Mechanisms of Catalysis within the Complex: The active site employs several strategies to lower the activation energy of the reaction [25]:

- Covalent Catalysis: Transient formation of a covalent bond between the enzyme and substrate.

- General Acid-Base Catalysis: Amino acid residues donate or accept protons.

- Catalysis by Approximation: Binding brings two substrates into close proximity and optimal orientation.

- Metal Ion Catalysis: Bound metal ions stabilize charges, mediate redox reactions, or enhance nucleophilicity. These mechanisms are optimized within the ES complex to maximize kcat, the catalytic rate constant directly related to Vmax (Vmax = kcat [E]total).

Modern Structural Analysis: Contemporary techniques like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations now allow researchers to visualize and simulate the dynamic conformational states (open, intermediate, closed) of the ES complex, linking structural flexibility directly to substrate capture and catalytic efficiency [24] [26]. This provides a physical basis for understanding kinetic parameters.

3. The Steady-State Assumption and the Derivation of Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

The kinetic behavior of the ES complex is described by the Michaelis-Menten model. For the reversible reaction:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P

The key challenge is solving for the rate of product formation (v) as a function of substrate concentration [S].

The Steady-State Assumption: In 1925, Briggs and Haldane introduced a critical simplification [27]. They proposed that after a brief initial transient, the concentration of the ES complex remains constant over time because the rate of its formation equals the rate of its breakdown (to product + enzyme or back to substrate + enzyme). This is expressed as

d[ES]/dt = 0. This assumption is valid when the total enzyme concentration [E]_total is much lower than [S], a condition typical in experimental setups [27] [5].Derivation of the Michaelis-Menten Equation: Applying the steady-state assumption and mass conservation ([E]total = [E]free + [ES]), the rate equation simplifies to:

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])Here, Vmax (kcat * [E]_total) is the maximum theoretical rate at saturating [S], and Km (the Michaelis constant) is the substrate concentration at which v = Vmax/2 [12] [5]. Km is an aggregate constant approximating the enzyme's affinity for the substrate; a lower Km generally indicates higher affinity.Graphical Representation and Meaning of Parameters: The plot of v vs. [S] is a rectangular hyperbola. At low [S] ([S] << Km), the reaction is first-order with respect to [S], and v is approximated by (Vmax/Km)[S]. The specificity constant kcat/Km is the critical measure of catalytic efficiency under these conditions [12]. At high [S] ([S] >> Km), the reaction rate approaches Vmax (zero-order in [S]), and the enzyme is saturated.

Table 1: Representative Michaelis-Menten Parameters for Enzymes [12]

| Enzyme | Km (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Catalytic Efficiency Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 | Moderate efficiency |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ | Extremely high efficiency (diffusion-limited) |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ | Very high affinity and efficiency |

4. Experimental Determination of Vmax and Km: Methodologies and Best Practices

Accurate estimation of Vmax and Km is critical for reliable biochemical characterization. Methods have evolved from linear transformations to more robust nonlinear techniques.

Classical Linear Transformation Methods: These involve algebraically manipulating the Michaelis-Menten equation to generate linear plots.

- Lineweaver-Burk (Double-Reciprocal) Plot:

1/v vs. 1/[S]. While historically widespread, it is statistically flawed as it distorts experimental error, giving undue weight to low-velocity data points [28]. - Eadie-Hofstee Plot:

v vs. v/[S]. Less prone to error distortion than Lineweaver-Burk but still inferior to direct nonlinear fitting [28].

- Lineweaver-Burk (Double-Reciprocal) Plot:

Modern Nonlinear Regression (NLR): The preferred method is to fit the untransformed velocity (v) vs. substrate concentration ([S]) data directly to the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation using iterative computational algorithms (e.g., in GraphPad Prism, NONMEM) [28]. This method treats all data points with appropriate weighting and yields the most accurate and precise estimates of Vmax and Km with associated confidence intervals.

Full Time-Course Analysis (NM Method): The most advanced approach fits the raw time-course data of substrate depletion or product formation to the integrated form of the Michaelis-Menten equation [28]. This method, often using powerful software like NONMEM, utilizes all data points without requiring the estimation of initial velocities, further improving parameter accuracy, especially with complex error structures.

Table 2: Comparison of Vmax and Km Estimation Methods [28]

| Estimation Method | Data Transformation | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Relative Accuracy/Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | 1/v vs. 1/[S] |

Simple visualization of inhibition type | Severe error distortion; poor parameter reliability | Low |

| Eadie-Hofstee (EH) | v vs. v/[S] |

Less error distortion than LB | Error not uniform; suboptimal for statistical inference | Moderate |

| Nonlinear Regression (NL) | v vs. [S] (direct fit) |

Proper error weighting; statistically sound | Requires computational software | High |

| Full Time-Course (NM) | [S] vs. time (integrated fit) |

Uses all data; no initial velocity approximation | Requires sophisticated software and modeling expertise | Highest |

5. Advanced Protocols: From Structural Biology to Computational Prediction

Protocol 1: Structural Characterization of the ES Complex via Crystallography/cryo-EM.

- Sample Preparation: Purify the target enzyme to homogeneity. For crystallography, generate a high-concentration protein solution and screen crystallization conditions with and without substrate or a non-reactive substrate analogue [24]. For cryo-EM, vitrify the sample in a thin layer of ice [26].

- Data Collection & Modeling: Collect X-ray diffraction or cryo-EM images. Solve the phase problem (crystallography) or perform 3D reconstruction (cryo-EM). Dock the substrate into the active site electron density, which may require computational modeling if a true substrate complex is not captured [24].

- MD Simulation Refinement: Use the solved structure as a starting point for molecular dynamics simulations in explicit solvent to model the dynamic behavior and conformational sampling of the ES complex under physiological conditions [24] [26].

Protocol 2: Kinetic Parameter Estimation via Nonlinear Regression.

- Experimental Data Collection: Perform initial velocity experiments. Hold enzyme concentration constant and measure initial velocity (v) across a wide range of substrate concentrations [S] (spanning ~0.2–5 x Km). Use sensitive, continuous assays where possible.

- Data Preparation: Input paired [S] and v data into statistical software, ensuring v values have appropriate error estimates (e.g., standard deviation from replicates).

- Model Fitting: Fit the data to the model

v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S]). Use appropriate weighting (e.g., 1/variance). Estimate parameters by least-squares minimization. - Validation: Assess goodness-of-fit (R², residual plot). Report Vmax and Km with 95% confidence intervals. Compare models if testing for inhibition (competitive, non-competitive) [28].

Protocol 3: In silico Prediction of Substrate Specificity and Kinetics.

- Model Training: As demonstrated by AI tools like EZSpecificity, train a graph neural network on a comprehensive database of known enzyme structures (or sequences) and their validated substrates [29].

- Feature Encoding: Represent the enzyme active site and candidate substrate molecules as graphs, encoding atomic properties, bonds, and spatial relationships [29].

- Prediction & Validation: The model outputs a prediction of catalytic compatibility or a quantitative activity score. These computational hits must be validated experimentally through targeted kinetic assays [30] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Resources

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Enzyme | The catalyst under investigation. Must be highly pure and active. | Recombinantly expressed and affinity-purified protein. |

| Substrates & Analogues | To measure activity and, for analogues, to trap the ES complex for structural studies. | Natural physiological substrate; unreactive transition-state analogues (e.g., phosphonates). |

| Cofactors & Cations | Required for the activity of many enzymes (metalloenzymes, dehydrogenases). | Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, NADH, ATP. Concentration must be optimized and held constant in assays. |

| Detection Reagents | To quantify substrate loss or product formation continuously or at endpoint. | Chromogenic/fluorogenic probes, coupled enzyme systems, HPLC-MS standards. |

| Crystallization/Cryo-EM Kits | To generate ordered arrays (crystals) or vitrified samples for structural analysis. | Sparse matrix screens; graphene oxide grids for cryo-EM [26]. |

| Kinetic Analysis Software | To fit data, estimate parameters, and perform statistical analysis. | GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot; NONMEM for advanced population kinetic modeling [28]. |

| Computational Suites | For MD simulations, molecular docking, and AI/ML-based prediction. | CHARMM/NAMD (MD) [24]; AutoDock (docking); EZSpecificity models (specificity prediction) [29]. |

6. Future Directions: AI, Dynamics, and the Expansion of Kinetic Theory

The field is moving beyond static measurements of Km and Vmax. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing enzyme science. Models like EZSpecificity can predict substrate specificity from sequence or structure, guiding enzyme engineering and the discovery of biocatalysts for novel reactions [30] [29]. This integrates directly with directed evolution, where AI models can predict fitness landscapes, dramatically accelerating the optimization of kcat and Km [30]. Furthermore, techniques like cryo-EM are revealing that enzymes are not static locks but dynamic machines; the distribution of conformational states influences the macroscopic kinetic parameters [26]. Future kinetic models may incorporate these dynamic ensembles, leading to a more nuanced understanding of catalysis that bridges structural biology, computational prediction, and high-precision kinetic parameter estimation.

Visualization: Enzyme Catalysis Mechanism and Kinetic Analysis

Experimental Approaches and Analytical Methods for Vmax and Km Determination

Accurate estimation of the kinetic parameters Vmax (maximum reaction velocity) and Km (Michaelis constant) forms the cornerstone of quantitative enzymology and is critical in drug discovery, where enzymes constitute a major class of therapeutic targets [31]. These parameters are not mere numbers; they are fundamental descriptors of enzyme function, defining catalytic efficiency and substrate affinity. Their precise determination is essential for characterizing enzyme mechanisms, diagnosing metabolic disorders, and evaluating the potency and modality of inhibitory compounds.

This guide details the core experimental methodologies—initial velocity assays and progress curve analysis—within the rigorous framework required for reliable parameter estimation. A common pitfall in kinetic research is the generation of precise but inaccurate parameters due to flawed experimental design. This often stems from incorrect substrate concentration ranges, misapplication of the Michaelis-Menten equation under non-valid conditions, or improper analysis of reaction time courses [32] [33]. The following sections provide a technical roadmap for designing experiments that yield kinetically meaningful and reproducible estimates of Km and Vmax, ensuring data integrity for downstream applications in hit validation and structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies [31].

Foundational Concepts and Experimental Prerequisites

The Critical Importance of Initial Velocity Conditions

The Michaelis-Menten equation (v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])) is derived under steady-state assumptions, which are only valid when measuring the initial velocity of a reaction. An initial velocity is defined as the rate measured in the initial linear phase where less than 10% of the substrate has been converted to product [31]. Adhering to this condition is non-negotiable for several reasons:

- It ensures the substrate concentration ([S]) is essentially constant and equal to the starting concentration.

- It negates significant effects from product inhibition, substrate depletion, and the reverse reaction.

- It guarantees the reaction velocity is directly proportional to the enzyme concentration [31].

Failure to operate under initial velocity conditions leads to non-linear progress curves, an undefined and decreasing [S], and invalidates the steady-state kinetic treatment, rendering subsequent Km and Vmax estimates erroneous [31].

The Relationship Between Enzyme Concentration and Parameter Validity

A fundamental yet frequently overlooked criterion is the requirement for the total enzyme concentration ([E]₀) to be significantly lower than the Km. Recent rigorous analysis demonstrates that the classic Michaelis-Menten equation is only valid for reliably estimating both Km and Vmax when [E]₀ ≤ 0.01Km [33]. At higher enzyme concentrations (0.01Km < [E]₀ < Km), the reaction dynamics deviate, and a more complex equation is required. Operating with [E]₀ approaching or exceeding Km introduces significant systematic error into parameter estimates [33]. Therefore, a key step in assay development is empirically determining the dilute enzyme concentration that yields a linear progress curve for the assay duration while satisfying this stringent concentration criterion.

Defining the Optimal Substrate Concentration Range

Selecting the correct substrate concentrations is paramount for robust parameter estimation. The goal is to define a range that adequately captures the transition from first-order to zero-order kinetics.

- Minimum Range: A minimum of six substrate concentrations is recommended for an initial estimate [31].

- Optimal Range: For reliable fitting, use 8 or more substrate concentrations spanning from below to above the Km [31].

- Ideal Span: Concentrations should ideally cover 0.2Km to 5.0Km [31]. This range ensures sufficient data points in the sensitive, approximately linear region below Km and in the saturation region approaching Vmax.

For competitive inhibitor screening, the assay must be run with a substrate concentration at or below the Km value. Using [S] >> Km dramatically reduces the assay's sensitivity for detecting this important class of inhibitors [31].

Table 1: Guidelines for Key Experimental Parameters in Kinetic Assays

| Parameter | Optimal Value or Range | Rationale & Consequences of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Depletion | < 10% | Maintains [S] ~constant; >10% leads to non-linearity and invalid steady-state assumptions [31]. |

| [E]₀ / Km Ratio | ≤ 0.01 | Ensures validity of Michaelis-Menten equation for simultaneous Km & Vmax estimation [33]. |

| Substrate Concentration Range | 0.2Km – 5.0Km | Adequately characterizes hyperbolic saturation curve [31]. |

| Number of [S] Data Points | ≥ 8 | Enables robust non-linear regression fitting [31]. |

| Assay [S] for Inhibitor Screening | ≤ Km | Maximizes sensitivity for identifying competitive inhibitors [31]. |

Diagram 1: Kinetic Assay Development & Analysis Workflow

Core Experimental Methodologies

Initial Velocity Assays: Protocol and Best Practices

This method involves running separate reactions at different substrate concentrations and measuring the velocity at a single early time point for each.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare a master reaction buffer containing all necessary components (cofactors, salts, pH buffer). Separately, prepare a serial dilution of the substrate to generate at least 8 concentrations spanning the target range (e.g., 0.2–5.0 × estimated Km).

- Initiation: In a plate or cuvette, mix a fixed, dilute volume of enzyme solution with the reaction buffer. Initiate the reaction by adding the substrate solution. The final enzyme concentration must be validated to satisfy [E]₀ ≤ 0.01Km [33].

- Measurement: Immediately begin monitoring the increase in product (or decrease in substrate) using an appropriate detection method (e.g., absorbance, fluorescence). The signal must be confirmed to be linear with product concentration over the assay's range [31].

- Data Capture: Record the signal at short, regular intervals (e.g., every 10-30 seconds) for a period that captures only the initial linear phase. The duration of linearity must be pre-determined from a progress curve experiment.

- Control Measurements: Include negative controls lacking enzyme or substrate to correct for background signal [31].

- Velocity Calculation: For each substrate concentration, calculate the initial velocity (v₀) as the slope of the linear portion of the progress curve (signal vs. time).

Progress Curve Analysis: Protocol and Best Practices

This method obtains multiple data points from a single reaction by continuously monitoring product formation over time, fitting the entire curve to an integrated rate equation.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reagent Preparation: Similar to the initial velocity assay, prepare reaction buffer and substrate solution. Critical Requirement: For progress curve analysis, a single substrate concentration is insufficient to uniquely determine Km and kcat (k₂). Experiments must be performed at multiple starting substrate concentrations ([S]₀) to allow proper parameter identification [32].

- Reaction Initiation & Monitoring: Mix enzyme and substrate to start the reaction. Use a continuous detection method to collect signal data points at high frequency from the start of the reaction until it approaches completion or a clear plateau.

- Data Requirements: Collect dense time-course data for each [S]₀. The experiment must be designed such that the signal remains within the detection system's linear range throughout [31].

Mathematical Foundation:

For the simple irreversible reaction E + S → ES → E + P, the progress curve is described by the integrated equation:

t = (P/(k₂[E]₀)) + (Km/(k₂[E]₀)) * ln([S]₀/([S]₀ - P)) [32],

where P is product concentration at time t. Since this function cannot be explicitly solved for P, analysis requires non-linear fitting using specialized software.

Diagram 2: Progress Curve Analysis via Numerical Integration

Data Analysis and Parameter Estimation

Analyzing Initial Velocity Data

- Plotting: Plot the calculated initial velocity (v₀) against the corresponding substrate concentration ([S]).

- Non-Linear Regression: Fit the data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation using non-linear regression (e.g., in GraphPad Prism, SigmaPlot). This is the preferred method as it provides unbiased estimates of Vmax and Km.

- Linear Transformations (Caution): Transformations like Lineweaver-Burk (1/v vs. 1/[S]), Eadie-Hofstee, or Hanes-Woolf can be used for visualization but should not be used for primary parameter estimation. These transformations distort the error structure of the data and can give misleading results.

Analyzing Progress Curve Data

The analysis of full progress curves is computationally intensive and requires specialized tools. Two primary approaches exist [34]:

- Analytical Integration Approach: Uses the implicit integrated rate equation (like the one shown in Section 3.2). Software (e.g., some functions in Prism) can perform the non-linear fit of P(t) to this integrated form.

- Numerical Integration Approach: More flexible for complex mechanisms. Software tools like FITSIM or DYNAFIT allow the user to define a reaction mechanism with differential equations [32]. The program then simulates progress curves by numerically integrating these equations, iteratively adjusting rate constants until the sum of squared differences between simulated and experimental data is minimized [32].

Critical Consideration: A major pitfall is attempting to derive all individual rate constants (k₁, k₋₁, k₂) from a simple product formation curve. Different combinations of these constants can produce identical progress curves, making their unique identification impossible without additional experimental data [32]. The reliably determinable parameters from a standard progress curve are the composite constants Km and kcat (k₂).

Assessing Parameter Reliability: Monte Carlo Simulation

Given the complexity of progress curve fitting, assessing parameter uncertainty is crucial. Monte Carlo simulation is a powerful diagnostic tool for this purpose [32]. The process involves:

- Taking the best-fit curve and the observed variance of the experimental data.

- Generating thousands of synthetic "virtual" datasets by randomly perturbing the best-fit data points within the expected noise distribution.

- Refitting each synthetic dataset.

- Analyzing the distribution of the resulting parameter estimates to generate robust confidence intervals (e.g., 95% CI for Km and Vmax).

This method reveals whether the experimental design yields well-constrained, unique parameter estimates or if the parameters are highly correlated and uncertain [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Kinetic Analysis Methods

| Feature | Initial Velocity Assay | Progress Curve Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Effort | High (many separate reactions) | Lower (fewer reactions, continuous monitoring) [34]. |

| Data Yield per Reaction | Single v₀ data point | Dozens of [P] vs. time points. |

| Mathematical Analysis | Simpler (direct or linear fit). | Complex (numerical integration & non-linear fitting) [32] [34]. |

| Ability to Detect | Ideal for: Steady-state parameters (Km, Vmax). | Ideal for: Time-dependent phenomena (e.g., slow-binding inhibition, enzyme instability) [31]. |

| Key Pitfall | Missing non-linearity; using invalid [E]₀ [31] [33]. | Underdetermined systems; fitting too many parameters [32]. |

| Best for | Routine characterization; inhibitor screening. | Mechanistic studies; detailed characterization. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Assays

| Item | Function & Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Enzyme | The catalyst of interest. Source (recombinant, native), purity, and specific activity must be known and consistent [31]. | Test for contaminating activities. Aliquot and store to maintain stability. Determine lot-to-lot consistency [31]. |

| Defined Substrate | The molecule transformed by the enzyme. Can be the natural substrate or a synthetic surrogate [31]. | Purity is critical. Must have a reliable detection method for its depletion or product formation. Ensure adequate supply for entire project [31]. |

| Appropriate Cofactors | Molecules required for enzyme activity (e.g., metals, ATP, NADH). | Identify all essential cofactors from literature. Include at saturating concentrations in assays unless being studied as a variable substrate [31]. |

| Optimized Assay Buffer | Maintains constant pH and ionic strength, and provides optimal enzyme activity/stability. | Includes pH buffer, salts, potential stabilizing agents (e.g., BSA, glycerol). Must not interfere with detection [31]. |

| Validated Control Inhibitors | Known inhibitors (e.g., for kinases: staurosporine) used as assay controls. | Essential for validating assay performance and sensitivity during development and screening [31]. |

| Detection System Components | Enables quantification of reaction progress (e.g., fluorescent probe, coupled enzyme system, radioactive label). | Signal must be linear with product concentration over the entire assay range. Throughput, cost, and sensitivity should match project goals [31]. |

| Inactive Enzyme Mutant | Protein purified identically to wild-type but lacks catalytic activity. | Serves as the highest-quality negative control to identify non-enzymatic background signals [31]. |

Theoretical Foundations of Enzyme Kinetics and Parameter Estimation

The quantitative analysis of enzyme catalysis centers on determining two fundamental kinetic parameters: the maximum reaction velocity (Vmax) and the Michaelis constant (Km). Vmax represents the theoretical maximum rate of the reaction when the enzyme is fully saturated with substrate, while Km indicates the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax, providing a measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate [22]. These parameters are traditionally derived from the Michaelis-Menten equation, which describes the hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration and initial reaction velocity [20].

The classical linear transformation methods were developed to overcome the challenge of directly estimating Vmax and Km from the hyperbolic curve. By algebraically manipulating the Michaelis-Menten equation, these methods transform the data into linear forms, allowing for parameter estimation through linear regression. This approach dominated enzyme kinetics for decades before the widespread availability of non-linear regression software [35].

Within the broader thesis on Vmax and Km estimation research, these linear transformations represent the foundational methodologies that enabled the systematic study of enzyme behavior, inhibition mechanisms, and substrate specificity. Their development marked a critical transition from qualitative to quantitative enzymology, establishing standards for kinetic characterization that remain relevant despite advances in computational fitting methods [36].

The Michaelis-Menten Framework and Transformation Principles

The Michaelis-Menten equation, v = (Vmax × [S]) / (Km + [S]), where v is the initial velocity and [S] is the substrate concentration, forms the basis for all three linear transformation methods [20]. This equation arises from the fundamental enzyme kinetic mechanism involving substrate binding, formation of an enzyme-substrate complex, and product release [36].

The linear transformations work by rearranging this equation into forms that yield straight lines when appropriate variables are plotted. Each transformation distributes experimental error differently and provides unique visual insights into the kinetic data. The common objective is to obtain accurate estimates of Vmax and Km through graphical methods that were more accessible before computational approaches became widespread [35].

Table 1: Fundamental Equations of Linear Transformations

| Plot Type | Linear Equation Form | X-axis Variable | Y-axis Variable | Slope | Y-intercept | X-intercept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk | 1/v = (Km/Vmax)×(1/[S]) + 1/Vmax |

1/[S] |

1/v |

Km/Vmax |

1/Vmax |

-1/Km |

| Eadie-Hofstee | v = Vmax - Km×(v/[S]) |

v/[S] |

v |

-Km |

Vmax |

Vmax/Km |

| Hanes-Woolf | [S]/v = (1/Vmax)×[S] + Km/Vmax |

[S] |

[S]/v |

1/Vmax |

Km/Vmax |

-Km |

Lineweaver-Burk (Double Reciprocal) Plot

Mathematical Derivation and Graphical Interpretation

The Lineweaver-Burk plot, introduced in 1934, is created by taking the reciprocal of both sides of the Michaelis-Menten equation, resulting in the linear form: 1/v = (Km/Vmax) × (1/[S]) + 1/Vmax [35]. This transformation yields a straight line when 1/v is plotted against 1/[S].

On the Lineweaver-Burk plot, the y-intercept corresponds to 1/Vmax, allowing direct determination of the maximum velocity. The x-intercept equals -1/Km, from which Km can be calculated. The slope of the line represents Km/Vmax [22] [37]. This plot gained widespread adoption due to the ease of determining both parameters from intercepts rather than slopes, which was considered advantageous for manual graphical analysis.

Applications in Inhibition Studies

The Lineweaver-Burk plot became particularly valuable for distinguishing different types of enzyme inhibition:

- Competitive inhibition: Increases the apparent Km without affecting Vmax, resulting in lines that intersect on the y-axis [35].

- Pure non-competitive inhibition: Decreases Vmax without altering Km, producing lines that intersect on the x-axis [35].

- Uncompetitive inhibition: Decreases both Vmax and apparent Km, yielding parallel lines [35].

- Mixed inhibition: Affects both Vmax and Km, creating lines that intersect in the second quadrant [35].

This diagnostic capability made the Lineweaver-Burk plot an essential tool for mechanistic studies in enzymology and drug development, where understanding inhibition patterns is crucial for therapeutic design [22].

Limitations and Error Considerations

Despite its historical popularity, the Lineweaver-Burk plot has significant statistical limitations. The reciprocal transformation distorts experimental error, giving disproportionate weight to measurements at low substrate concentrations where the relative error in 1/v is largest [35]. As noted in the literature, "if v = 1 ± 0.1 then 1/v = 1 ± 0.1, a 10% error. However, if v = 10 ± 0.1 then 1/v = 0.1 ± 0.001, only a 1% error" [35]. This uneven error distribution can lead to biased parameter estimates, particularly when data points are unevenly distributed across the substrate concentration range.

Eadie-Hofstee Plot

Mathematical Derivation and Graphical Interpretation

The Eadie-Hofstee plot uses the transformation v = Vmax - Km×(v/[S]), derived by multiplying both sides of the Michaelis-Menten equation by (Km + [S]), rearranging to isolate v on one side [38]. In this plot, v is plotted against v/[S], yielding a straight line with a slope of -Km and a y-intercept of Vmax.

An alternative form, sometimes called the Eadie plot, reverses the axes: v/[S] = (Vmax/Km) - (1/Km)×v, where the slope is -1/Km and the y-intercept is Vmax/Km [38]. This plot is mathematically equivalent to the Scatchard plot used in receptor-binding studies.

Advantages in Error Distribution

Unlike the Lineweaver-Burk transformation, the Eadie-Hofstee plot avoids taking reciprocals of the measured velocity, resulting in more uniform error distribution across the data range [39]. Experimental error is typically assumed to affect the rate v rather than the substrate concentration a, and since v appears on both axes, the errors are correlated [38]. This correlated error structure makes the Eadie-Hofstee plot less sensitive to experimental scatter than the Lineweaver-Burk plot.

Additionally, because the ordinate spans the entire theoretical range of v (from 0 to Vmax), the Eadie-Hofstee plot makes it easier to visually identify data points that deviate significantly from expected behavior, potentially revealing faults in experimental design or assumptions [38].

Historical Context and Attribution

The transformation underlying the Eadie-Hofstee plot has a complex history of independent discovery. Although commonly associated with Eadie (1942) and Hofstee (1959), the linear form was originally credited to Woolf by Haldane and Stern in 1932 [38]. Haldane later clarified in 1957 that "Woolf pointed out that linear graphs are obtained when v is plotted against v×[S]⁻¹, v⁻¹ against [S]⁻¹, or v⁻¹×[S] against [S], the first plot being most convenient unless inhibition is being studied" [38].

The plot is occasionally attributed to Augustinsson (1948), though he did not explicitly cite the earlier work of Haldane, Woolf, or Eadie when introducing the v versus v/[S] plot [38]. This multiplicity of attribution reflects the independent mathematical derivation of this transformation by multiple researchers.

Hanes-Woolf Plot

Mathematical Derivation and Graphical Interpretation

The Hanes-Woolf plot utilizes the transformation [S]/v = (1/Vmax)×[S] + Km/Vmax, derived by multiplying both sides of the Lineweaver-Burk equation by [S] [40]. This yields a linear relationship when [S]/v is plotted against [S].

In this plot, the slope equals 1/Vmax, allowing direct calculation of Vmax. The y-intercept is Km/Vmax, from which Km can be derived using the already determined Vmax value. Alternatively, the x-intercept is -Km [40]. This plot is particularly useful when studying allosteric enzymes, as it can clearly display changes in reaction velocity under varying substrate concentrations [40].

Statistical Advantages

The Hanes-Woolf plot offers superior statistical properties compared to the Lineweaver-Burk plot. Unlike the double-reciprocal transformation, the Hanes-Woolf plot does not disproportionately amplify errors at low substrate concentrations [40]. The transformation results in more evenly distributed errors across the data range, leading to more reliable parameter estimates through linear regression.

Comparative studies have shown that the Hanes-Woolf plot generally provides more accurate estimates of Vmax and Km than the Lineweaver-Burk plot, especially when data quality is variable or when substrate concentrations span limited ranges [40]. This advantage made it preferable for many practical applications despite the slightly more complex parameter extraction (requiring both slope and intercept rather than just intercepts).

Applications in Modern Analysis

While all linear transformation methods have been largely superseded by nonlinear regression for primary parameter estimation, the Hanes-Woolf plot retains value for diagnostic purposes. Its linear representation makes it easier to visually assess data quality, identify outliers, and detect deviations from Michaelis-Menten behavior that might indicate cooperativity, substrate inhibition, or other complex kinetic phenomena [40].

Comparative Analysis of Linear Transformation Methods

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Linear Transformation Methods

| Characteristic | Lineweaver-Burk Plot | Eadie-Hofstee Plot | Hanes-Woolf Plot |