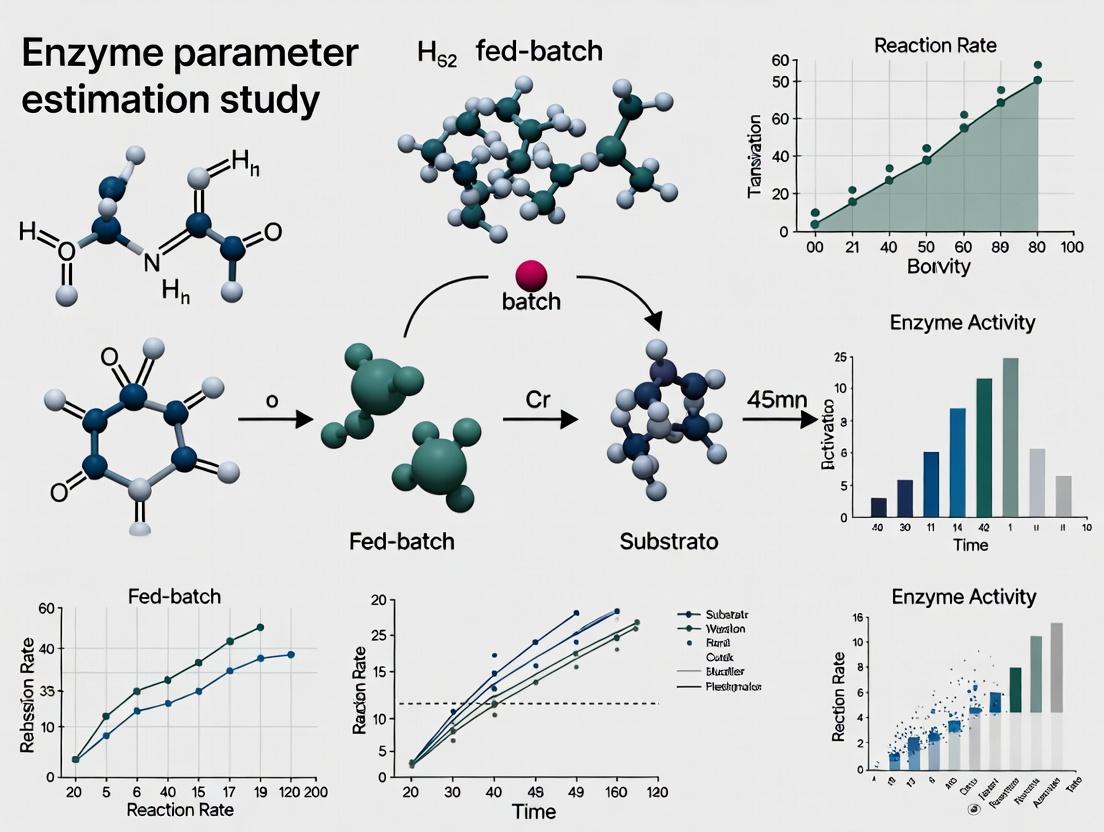

Modern Data Science and Enzyme Kinetics: Precise Strategies for Batch vs. Fed-Batch Parameter Estimation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioprocess engineers on the critical task of estimating enzyme kinetic parameters within batch and fed-batch cultivation systems.

Modern Data Science and Enzyme Kinetics: Precise Strategies for Batch vs. Fed-Batch Parameter Estimation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and bioprocess engineers on the critical task of estimating enzyme kinetic parameters within batch and fed-batch cultivation systems. We begin by establishing the foundational principles of each bioprocess mode and their distinct implications for kinetic analysis [citation:1][citation:10]. The core of the article details the methodological workflow, from designing experiments and constructing mass balance models to applying advanced statistical and machine learning frameworks for parameter estimation [citation:3][citation:9]. We then address common analytical challenges, such as overcoming substrate and product inhibition, and outline strategies for model optimization and troubleshooting [citation:6][citation:7]. Finally, we discuss robust methods for validating estimated parameters, present comparative analyses of performance across different systems, and evaluate how these decisions impact downstream biopharmaceutical production [citation:3][citation:5]. This synthesis aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to select and optimize the most effective parameter estimation strategy for their specific application.

Core Concepts and Strategic Choices: Understanding Batch and Fed-Batch Dynamics for Enzyme Studies

Core Concept Comparison for Parameter Estimation

This technical guide supports researchers in selecting and optimizing bioprocess operation modes for enzyme kinetic studies and bioproduction. The choice between batch (closed) and fed-batch (semi-open) systems is foundational, impacting parameter estimation accuracy, experimental outcomes, and scalability [1] [2].

- Batch Process (Closed System): All nutrients are provided at the beginning. The system is "closed" as no additional substrates are added during cultivation, only gases and pH control agents [1]. It is a discontinuous process where the culture runs until nutrients are depleted [1].

- Fed-Batch Process (Semi-Open System): Nutrients (substrates) are added incrementally during cultivation, but no culture broth is removed until harvest [1]. It is a semi-continuous process that extends the productive culture duration [1].

- Key Context for Research: For enzyme kinetic parameter estimation (e.g., Michaelis-Menten constants), studies show that a substrate-fed-batch process design can significantly improve estimation precision compared to pure batch experiments. The Cramér-Rao lower bound for the variance of parameter estimation error can be reduced to 82% for μmax and 60% for Km on average [3] [4].

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences critical for experimental planning.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Batch vs. Fed-Batch Systems

| Characteristic | Batch (Closed System) | Fed-Batch (Semi-Open System) |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Addition | Single charge at start [1] [2]. | Incremental feeding during cultivation [1] [2]. |

| System Classification | Discontinuous [1]. | Semi-continuous [1]. |

| Growth Kinetics | Defined phases: lag, exponential, stationary, decline [2]. | Exponential phase can be prolonged [1]. |

| Primary Control Levers | Initial conditions (concentration, pH, temperature) [1]. | Feeding profile (rate, timing, composition) [1]. |

| Volume | Constant [1]. | Increases during feed phase [1]. |

| Parameter Estimation | Suitable for initial screening and basic kinetics [1]. | Superior for precise estimation of kinetic parameters; allows dynamic probing of enzyme behavior [3] [4]. |

| Best For | Rapid experiments, strain characterization, medium optimization [1]. | High-density cultures, maximizing product titer, detailed kinetic studies [1] [3]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Declining Reaction Rate or Cell Growth Mid-Experiment

- In Batch Mode: Likely caused by substrate depletion or inhibitor accumulation (e.g., ethanol, acids) [1] [5]. Check: Monitor glucose/primary carbon source concentration. High initial substrate can also cause inhibition [5].

- In Fed-Batch Mode: Could indicate incorrect feeding profile. An excessive feed rate may cause inhibitor buildup (e.g., lactate), while a too-slow rate starves the culture [1] [6]. Check: Review feeding calculations. Use online sensors (e.g., DO, pH) as indirect indicators of metabolic shifts [7].

Problem: Low Final Product Titer or Yield

- In Batch Mode: Often limited by initial substrate load due to inhibition or viscosity constraints [8]. For enzymatic hydrolysis, high solid loading (>15% w/v) can reduce conversion rates [8].

- In Fed-Batch Mode: Potential sub-optimal feeding strategy. A linear feed may not match exponential demand. Solution: Implement an exponential feeding strategy calibrated to the specific growth or reaction rate [9] [7]. For product induction, time the feed to trigger metabolic switches.

Problem: Poor Reproducibility of Kinetic Data

- In Batch Mode: Variability often stems from inconsistent initial conditions (cell viability, substrate concentration, residual metabolites from inoculum) [10].

- In Fed-Batch Mode: Reproducibility is highly sensitive to feeding precision. Manual or poorly calibrated pumps introduce error [6]. Solution: Automate feeds using bioreactor controllers and calibrate pumps regularly. For parameter estimation, a model-based design of experiments (DoE) is recommended to define robust feeding and sampling points [3].

Problem: Excessive Foaming or Viscosity During Process

- In Batch Mode: Typically occurs with high initial protein or polysaccharide concentrations. Solution: Reduce initial solid loading, use antifoam agents, or modify medium composition [8].

- In Fed-Batch Mode: Often triggered by a feeding pulse that introduces proteins or lipids. Solution: Switch to a continuous, low-rate feed instead of bolus addition. For high-solid enzymatic hydrolysis, fed-batch is specifically used to avoid high initial viscosity [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a batch over a fed-batch process for initial experiments?

- A: Use batch for short-duration screening (e.g., comparing enzyme variants, testing medium compositions, assessing strain growth) because it is simpler, faster, and has a lower contamination risk [1]. It provides a quick baseline for kinetic constants before fed-batch optimization.

Q2: How do I design my first fed-batch feeding protocol?

- A: Start with a simple pulse feed based on a depletion signal (e.g., glucose reading, DO spike) [6]. For growth-associated production, an exponential feed rate (calculated from your target specific growth rate, μ) is a robust starting point to avoid overflow metabolism [9] [7]. Always simulate feeding volumes to ensure they don't exceed your bioreactor's working capacity.

Q3: Can I switch from batch to fed-batch mode seamlessly in one experiment?

- A: Yes, this is standard practice. Most fed-batch processes begin with a batch phase to build biomass, followed by the initiation of feeding as nutrients deplete [2] [6]. The transition point is critical and should be determined by a clear metabolite signal (e.g., glucose near zero).

Q4: How does the system choice impact downstream processing?

- A: Fed-batch typically achieves higher product concentrations, reducing the volume to be processed and increasing the efficiency of downstream steps like centrifugation and filtration [1] [8]. However, very high cell densities can also create challenges like increased viscosity [1].

Q5: For enzyme kinetic studies, why is fed-batch sometimes better for parameter estimation?

- A: A substrate-fed-batch experiment generates a dynamic range of substrate concentrations over time from a single run, providing more informative data for fitting models like Michaelis-Menten. Analytical analysis of the Fisher Information Matrix shows that substrate feeding with a small volume flow can optimize the estimation of Vmax and Km, reducing confidence intervals compared to batch [3] [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fed-Batch Cultivation for Recombinant Protein (e.g., mAb) Production

Adapted from a monoclonal antibody production study [6].

Objective: To maximize cell density and product titer using a controlled feeding strategy.

- Inoculum & Bioreactor Setup: Grow CHO cells in shake flasks. Inoculate a bioreactor with a defined medium to an initial viable cell density of ~0.3-0.5 x 10⁶ cells/mL [6].

- Batch Phase: Maintain temperature at 37°C, pH at 7.0, and dissolved oxygen (DO) at 50%. Allow cells to grow in batch mode until the primary carbon source (e.g., glucose) is nearly depleted (typically 2-3 days) [6].

- Feed Initiation: Begin feeding a concentrated nutrient supplement (e.g., EfficientFeed) at a rate of 3-5% of the initial working volume per day. Automate feeding using a bioreactor controller for precision [6].

- Process Control: Implement a temperature shift to 32-33°C upon feed start to prolong culture viability and enhance protein production [6]. Maintain glucose at a low setpoint (e.g., >3 g/L) via bolus additions based on daily assays.

- Harvest: Terminate the culture when viability drops below 70-80% (typically day 10-14). Cool the bioreactor and proceed to harvest.

Protocol 2: Fed-Batch Enzymatic Hydrolysis for High-Sugar Yield

Adapted from a kinetic study on lignocellulosic biomass [8].

Objective: To achieve high sugar concentrations by mitigating substrate inhibition at high solid loadings.

- Batch Kinetics Prelim: Perform batch hydrolysis experiments at various solid consistencies (e.g., 5%, 10%, 15% w/v) to determine the inhibition threshold and initial rate constants [8].

- Fed-Batch Setup: Charge the reactor with an initial substrate load below the inhibition threshold (e.g., 10% w/v). Add cellulase enzymes at standard dosage [8].

- Feeding Strategy: Use a discrete pulse-feeding policy. Add pre-measured, sterile solid substrate (e.g., 50 g) when the hydrolysis rate slows significantly (monitored by sugar release rate). In the referenced study, pulses were added at 24, 56, and 80 hours [8].

- Monitoring: Sample regularly to measure glucose concentration and insoluble solids. Compare the profile to a kinetic model simulation if available [8].

- Termination: Stop hydrolysis when the total solid loading target is reached (e.g., cumulative 20% w/v) and the sugar release rate plateaus.

Table 2: Key Outcomes from Protocol 2 (Example Data) [8]

| Process Mode | Initial/Cumulative Substrate | Final Sugar Concentration | Cellulose Conversion | Subsequent Ethanol Titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | 20% (w/v) initial | 80.78 g/L | 40.39% | 34.78 g/L |

| Fed-Batch | 20% (w/v) cumulative | 127.00 g/L | 63.56% | 52.83 g/L |

Visual Guide: System Workflows & Decision Logic

Decision Logic for Selecting Batch vs. Fed-Batch Mode

Typical Phased Workflow of a Fed-Batch Experiment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Fed-Batch vs. Batch Experiments

| Item | Function | Key Consideration for Fed-Batch |

|---|---|---|

| Concentrated Feed Solution | Provides nutrients (C, N, P, vitamins) without excessive dilution [6]. | Must be sterile, compatible with base medium. Osmolarity needs to be controlled to avoid cell stress. |

| Precision Peristaltic Pumps | Delivers feed at controlled, often variable, rates [6]. | Calibration is critical. Use pumps compatible with bioreactor automation software. |

| On-line/Auto-sampler Sensors | Monitors key parameters (e.g., glucose, DO, pH, OD) [7]. | Enables feedback control of feeding (e.g., pH-stat, DO-stat) [10]. |

| Antifoam Agents | Controls foam from proteins or surfactants [7]. | Fed-batch processes may require more due to accumulating products. Can be added via automated pump. |

| Cell Retention Device (for perfusion) | Retains cells while removing spent medium [6]. | For advanced continuous fed-batch or perfusion processes. Not used in standard fed-batch. |

| Modeling & DoE Software | Designs optimal feeding strategies and sampling points [3] [9]. | Uses preliminary batch data to simulate and optimize fed-batch protocols for parameter estimation [3]. |

| High-Quality Substrate | The target molecule for enzymatic conversion or cell metabolism. | In fed-batch, ensure sterilizability and solubility of the feed stock solution. |

Comparative Impact on Microbial Physiology and Enzyme Expression Profiles

This technical support center is designed within the context of thesis research focused on parameter estimation for enzyme kinetics and microbial physiology in batch versus fed-batch systems. The guides below address common experimental challenges, provide methodological clarity, and present comparative data to support your research and development work.

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem Category 1: Poor Enzyme Yields or Inconsistent Expression

Q1: My recombinant protein expression is low in batch culture, even with high cell density. What's wrong?

- A: In batch mode, high initial substrate (e.g., glucose) concentrations can cause catabolite repression, inhibiting the expression of target enzymes. A fed-batch strategy is designed to alleviate this. For example, in recombinant yeast, the expression of the SUC2 gene (invertase) is derepressed only when glucose levels fall below 2 g/L [11]. Implement a fed-batch protocol to first build biomass at a moderate growth rate, then deplete the carbon source to trigger derepression before initiating a controlled feed to maintain expression.

Q2: I am using a fed-batch strategy, but my enzyme productivity is not improving as expected.

- A: The feeding strategy is likely suboptimal. Fed-batch is not a single method but a range of strategies (constant, exponential, DO-stat, pH-stat). The optimal choice depends on your organism and product. For instance, a study on β-fructofuranosidase production in Pichia pastoris found that while a DO-stat strategy achieved higher maximum enzyme activity, a constant feed strategy resulted in better volumetric productivity due to a significantly shorter process time (59h vs. 155h) [12]. Review your feeding profile (rate, timing, substrate concentration) and consider a model-based approach to optimize it.

Problem Category 2: Inhibitory Effects and Reduced Cell Viability

Q3: My batch fermentation stops prematurely, likely due to inhibition. How can I mitigate this?

- A: Premature cessation is a classic limitation of batch processes where substrates, products, or by-products accumulate to inhibitory levels [1]. This is prevalent in processes involving lignocellulosic hydrolysates (inhibitors like furfurals) or organic acid production. Fed-batch operation is a primary solution. By gradually adding substrate, you prevent toxic concentrations from building up. For example, in butyric acid fermentation by Clostridium tyrobutyricum, fed-batch operation is used to avoid strong inhibition from high initial glucose and the final product [13]. A repeated fed-batch or semi-continuous approach, where part of the broth is harvested and replaced with fresh medium, can also prevent toxic metabolite accumulation [1].

Q4: I'm working with high-solid enzymatic hydrolysis, but mixing and viscosity are crippling my batch process.

- A: Switch to a fed-batch enzymatic hydrolysis protocol. Adding solid substrate incrementally allows for higher final solid loads while maintaining manageable viscosity. Research on saccharifying pretreated biomass showed that while batch mode at 20% solid loading yielded 80.78 g/L sugars, a fed-batch strategy with staggered substrate addition increased the final sugar concentration to 127 g/L [8]. This also improves conversion rates and reduces shear stress on both cells and enzymes.

Problem Category 3: Suboptimal Growth and Process Parameters

Q5: How do I accurately estimate kinetic parameters (μmax, Ks, Y_x/s) for my fed-batch model from batch experiments?

- A: This is a core task for thesis research. Conduct a series of carefully controlled batch fermentations with varying initial substrate concentrations. Use the data to fit unstructured kinetic models (e.g., Monod with substrate/product inhibition terms). As demonstrated for Clostridium tyrobutyricum, parameters estimated from batch data (μmax, Ks, inhibition constant K_I) can successfully predict and optimize fed-batch performance when integrated into mass balance equations [13]. Remember that fed-batch introduces a dilution effect; ensure your model accounts for changing volume [14].

Q6: My fed-batch culture shows metabolic shifts (e.g., to the Crabtree effect) that ruin my product profile. How can I control this?

- A: This highlights the critical link between feeding, physiology, and metabolism. High glucose influx in fed-batch can trigger overflow metabolism (e.g., ethanol formation in yeast even under aerobic conditions). To promote efficient respiratory metabolism and desired product formation, you must implement a strictly controlled, growth-limiting feed. The goal is to maintain the substrate concentration below the critical level that triggers the metabolic shift. Monitoring the respiratory quotient (RQ) can be a valuable online indicator of this metabolic state.

Comparative Data: Batch vs. Fed-Batch Performance

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from published research, illustrating the physiological and productivity impacts of cultivation mode.

Table 1: Comparative Performance in Biofuel and Chemical Production

| System & Product | Cultivation Mode | Key Performance Indicator (Batch) | Key Performance Indicator (Fed-Batch) | Physiological & Kinetic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Biomass [8] | Batch | Sugar: 80.78 g/L Conversion: 40.4% | Sugar: 127.0 g/L Conversion: 63.6% | Fed-batch mitigates substrate inhibition and high viscosity at elevated solid loadings, enabling higher total substrate processing and conversion. |

| SSF for Ethanol from Spruce [15] | Batch | Ethanol: ~40-44 g/L | Ethanol: ~40-44 g/L | With inhibitor-adapted yeast, final titers were similar. Fed-batch showed higher productivity in the first 24h, allowing slower substrate feeding to manage inhibitors. |

| Butyric Acid with C. tyrobutyricum [13] | Batch (Model) | Subject to strong substrate & product inhibition | Increased production & growth (Model) | Fed-batch is essential to avoid inhibition from high initial glucose and butyric acid accumulation, enabling extended production. |

| MEL Biosurfactants with M. aphidis [16] | Batch | Biomass: 4.2 g/L MEL rate: ~0.1 g/L·h | Biomass: 10.9-15.5 g/L MEL rate: ~0.4 g/L·h | Exponential fed-batch dramatically increases biomass, which drives higher volumetric productivity of the secondary metabolite. |

Table 2: Impact on Recombinant Protein and Cell Production

| System & Product | Cultivation Mode | Key Performance Indicator | Physiological & Kinetic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Yeast Invertase [11] | Fed-Batch | Expression derepressed at glucose < 2 g/L | Fed-batch enables separation of growth (high glucose) and product formation (low glucose) phases, directly controlling enzyme expression via catabolite regulation. |

| β-fructofuranosidase in P. pastoris [12] | Fed-Batch (DO-stat) | Higher max volumetric activity | DO-stat feeding maintains healthy, oxygen-limited growth for extended expression phases. |

| Fed-Batch (Constant) | Higher volumetric productivity (shorter time) | Constant feed supports faster biomass accumulation and shorter process cycles, favoring productivity. | |

| Recombinant BCG Vaccine [17] | Simple Batch | Higher optical density (OD) | Fed-batch with pH-stat control of glutamate feed did not increase max growth rate but improved cell viability and recovery after lyophilization, a critical product quality attribute. |

| Fed-Batch (pH-stat) | Better post-lyophilization viability |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

Protocol 1: Model-Based Fed-Batch Setup for Inhibitory Products (e.g., Butyric Acid) [13]

- Batch Kinetic Characterization: Perform a series of batch fermentations with the target organism (e.g., Clostridium tyrobutyricum) across a wide range of initial substrate concentrations (e.g., 0-150 g/L glucose).

- Data Collection: Monitor biomass (OD or DW), substrate (glucose), and products (butyric/acetic acid) concentration over time.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit the data to an appropriate model (e.g., an extended Monod model with substrate inhibition

μ = μ_max * S / (K_s + S + S²/K_I)and a Luedeking-Piret model for product formation). - Fed-Batch Strategy Design: Using the estimated parameters and mass balance equations, design a feeding profile that maintains the substrate concentration below the inhibitory threshold while supporting sustained production.

- Validation: Run the model-predicted fed-batch process and compare results to batch controls.

Protocol 2: Fed-Batch Enzymatic Hydrolysis for High Solid Loadings [8]

- Baseline Batch Kinetics: Conduct batch enzymatic hydrolysis at various solid consistencies (e.g., 5%, 10%, 15%, 20% w/v). Determine the hydrolysis rate constant (k) for each.

- Identify Limiting Consistency: Note the consistency at which the rate constant significantly drops and viscosity becomes problematic (e.g., at 20%).

- Design Fed-Batch Schedule: Start hydrolysis at a lower, non-inhibitory consistency (e.g., 10%). At defined time intervals (e.g., 24h, 56h), add pulses of solid substrate to bring the cumulative loading to the target level.

- Monitor: Track sugar release and viscosity. The incremental addition keeps the reaction mixture more fluid, improving mass transfer and enzyme accessibility.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Below are diagrams illustrating the metabolic regulation and experimental workflow central to batch vs. fed-batch comparisons.

Diagram 1: Metabolic Regulation in Batch vs. Fed-Batch Cultivation

Diagram 2: Workflow for Kinetic Parameter Estimation & Fed-Batch Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Batch/Fed-Batch Parameter Estimation Studies

| Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Research Context | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Defined/Minimal Medium | Essential for accurate kinetic modeling and parameter estimation (Yields, Stoichiometry). Eliminates unknown variables from complex media. | Used in fed-batch production of mannosylerythritol lipids (MEL) for clear growth/product correlation [16]. |

| Controlled-Substrate Feed Solution | The core of fed-batch experimentation. Allows precise manipulation of growth rate, avoidance of inhibition, and induction/derepression of enzyme expression. | Used in all fed-batch studies; e.g., glucose feed for yeast [11], glycerol feed for P. pastoris [12]. |

| Antifoam Agents (e.g., Tween-80, Pluronic) | Critical for fed-batch and high-cell-density processes where aeration and surfactants (e.g., biosurfactants) cause excessive foaming and potential reactor overflow. | Used in BCG bioreactor cultivations to prevent foaming and cell aggregation [17]. |

| Enzyme Inhibitors/Activators | Used in in vitro assays to characterize enzymes extracted from cultures. Helps link physiological state (from cultivation) to specific enzyme kinetic properties. | Implied in studies measuring specific enzyme activity (e.g., invertase, cellulase) from culture samples. |

| Metabolic Probes/Indicators | Chemicals or dyes to assess cell physiology (viability, membrane potential, metabolic activity) in response to batch/fed-batch stresses. Useful for supporting growth data. | -- |

| Modeling & Simulation Software | Required for fitting batch data to kinetic models and simulating/predicting fed-batch profiles. Crucial for the "parameter estimation" thesis focus. | Used to model butyric acid batch kinetics and design fed-batch strategy [13]. |

| On-line Analyzers (e.g., for DO, pH, CO₂) | Provide real-time data for feedback control strategies (DO-stat, pH-stat) and for calculating metabolic rates (e.g., Oxygen Uptake Rate - OUR, Carbon Evolution Rate - CER). | DO-stat strategy used for β-fructofuranosidase production [12]; pH-stat for rBCG feeding [17]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Kinetic Parameter Estimation

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers navigating the challenges of kinetic parameter estimation in bioprocess development. The content is framed within a thesis investigating the comparative advantages of batch versus fed-batch cultivation for elucidating enzyme and microbial kinetics. The following FAQs, protocols, and tools are designed to help you select the appropriate bioprocess mode and overcome common analytical hurdles.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a fed-batch over a batch process for kinetic parameter estimation? A: The choice hinges on your experimental goals. Use batch for initial, rapid characterization of growth and substrate consumption kinetics under constant conditions. It is simpler and yields data for basic Monod or similar models. Opt for fed-batch when your goal is to 1) estimate maintenance coefficients and true yield parameters, 2) avoid substrate inhibition or catabolite repression, 3) study dynamic responses to nutrient shifts, or 4) maximize the resolution of kinetic data for a specific growth phase (e.g., steady-state growth at controlled specific rates). Fed-batch is essential for identifying parameters in more structured, segregated models [9].

Q2: My kinetic models fit training data well but fail in predictive validation. What could be wrong? A: This is a classic sign of overfitting or an incorrect model structure. First, ensure your parameter estimation algorithm (e.g., Differential Evolution, Genetic Algorithm) has converged on a global, not local, optimum [9]. Second, consider that the pre-defined model structure (e.g., simple Monod) may be inadequate. Advanced approaches like symbolic regression can discover alternative, more accurate algebraic expressions for rate equations directly from your concentration profile data without pre-assuming a structure [18]. Third, for fed-batch processes, verify that your model correctly accounts for the changing volume and feeding dynamics.

Q3: How can I leverage existing kinetic knowledge from a related organism or system for my new process? A: You can apply model structural transfer learning. This method uses an existing "source" kinetic model as a starting point and employs artificial neural networks (ANNs) to identify where corrections are needed. Feature attribution then guides symbolic regression to generate interpretable, mechanistic corrections (e.g., a new inhibition term). This adapts the model structure to your new system, accelerating development and providing physical insight into the differences between the two processes [19].

Q4: My parameter estimation is highly sensitive to initial guesses and yields inconsistent results. How can I improve robustness? A: Switch from local (e.g., gradient-based) to global evolutionary optimization algorithms. Studies show that Differential Evolution (DE) consistently outperforms or matches Genetic Algorithms (GA) for this task, finding better global optimum parameter sets that minimize error between experimental data and model predictions [9]. Employ multiple algorithm strategies (like DE/best/1/bin) and perform statistical analysis of the results to ensure consistency [9].

Q5: I have sparse or noisy experimental data. Can I still build an accurate kinetic model? A: Yes, but it requires specialized methods. Numerical differentiation based on regression (e.g., smoothing splines) can reduce noise in small time-series datasets before parameter estimation [18]. Furthermore, generative machine learning frameworks like RENAISSANCE can integrate diverse, sparse omics data (metabolomics, fluxomics) with physicochemical constraints to parameterize large-scale kinetic models that match observed dynamic phenotypes, even with limited traditional kinetic data [20].

Q6: My analytical assays (e.g., ELISA for host cell protein) are showing high background noise or poor precision during kinetic sampling. What should I check? A: This is critical as poor data quality invalidates all subsequent modeling.

- Contamination: Ensure you are not introducing analyte contamination. Use dedicated, clean pipettes with aerosol barrier tips, work in a separate area from concentrated sample handling, and avoid talking over open plates [21].

- Washing Technique: Incomplete or excessive washing of ELISA plates is a prime cause. Follow the kit's protocol precisely for wash volume, soak time, and number of cycles [21].

- Curve Fitting: Never force nonlinear ELISA data into a linear fit. Use recommended routines (4-parameter logistic, cubic spline) for accurate interpolation, especially at low concentrations crucial for kinetic decay phases [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Convergence in Parameter Estimation Algorithm

Symptoms: The objective function (e.g., sum of squared errors) does not stabilize between runs; parameters vary widely with different initial guesses. Steps:

- Visualize Data: Plot experimental data (biomass, substrate, product) to identify obvious trends or anomalies.

- Switch Algorithm: Implement a global optimizer. For fed-batch systems, Differential Evolution (DE) strategies like

best/1/binhave shown superior convergence [9]. - Parameter Bounds: Set physiologically plausible bounds for all parameters (e.g., positive values, maximum specific growth rate).

- Check Model ODEs: Ensure your system of ordinary differential equations is coded correctly, especially for fed-batch volume and feed terms.

Issue: Model Predictions Diverge from Fed-Batch Process Data After Feeding Begins

Symptoms: Good fit during batch phase, but error increases exponentially after feed start. Steps:

- Verify Feed Profile: Double-check the calculation and implementation of your feed rate (constant, exponential, etc.) in the model.

- Review Model Assumptions: The shift may reveal a change in metabolic state. Your model may need terms for maintenance energy, product inhibition, or a shift in yield coefficients at different growth rates. Consider applying structural transfer learning to identify the missing term [19].

- Validate Maintenance Coefficient: Design a fed-batch experiment to operate at very low specific growth rate. The substrate consumption rate at near-zero growth provides a direct estimate of the maintenance coefficient, which can then be fixed in your model.

Issue: Low Absorbance or Signal in Analytical Assays for Kinetic Samples

Symptoms: Sample readings fall below the standard curve, preventing quantification. Steps:

- Check Dilution Factors: Upstream samples may be too concentrated, causing a "hook effect" where high analyte levels saturate the assay, giving a false low signal. Perform a dilution linearity test [21].

- Sample Stability: Ensure analytes (e.g., enzymes, substrates) are stable under sampling and storage conditions (pH, temperature).

- Matrix Effects: The sample buffer may be interfering. Perform a spike-and-recovery experiment using the assay's recommended diluent to validate accuracy [21].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To estimate the global optimum set of kinetic parameters (e.g., for growth, substrate consumption, product formation) minimizing the error between experimental data and model simulations.

Materials: Time-series experimental data (Biomass-X, Substrate-S, Product-P), a defined kinetic model (e.g., with Monod, Luedeking-Piret equations), high-performance computing environment.

Procedure:

- Formulate the Optimization Problem:

- Define the objective function as the sum of squared errors (SSE) between

Nexperimental data points and model predictions:SSE = Σ (X_exp - X_model)² + (S_exp - S_model)² + (P_exp - P_model)². - Set decision variables as the vector of kinetic parameters (

μ_max, Ks, Yxs, etc.). - Define reasonable lower and upper bounds for each parameter.

- Define the objective function as the sum of squared errors (SSE) between

Implement Differential Evolution (DE):

- Initialize: Generate a random population of parameter vectors within the defined bounds.

- Mutation: For each target vector in the population, create a mutant vector. The study found

best/1/binstrategy effective:V = X_best + F * (X_r1 - X_r2), whereFis the scaling factor,X_bestis the best parameter set, andX_r1,X_r2are random population members [9]. - Crossover: Create a trial vector by mixing components of the target and mutant vectors based on a crossover probability (

CR). - Selection: Evaluate the SSE of the trial vector. If it outperforms the target vector, it replaces the target in the next generation.

- Iterate: Repeat Mutation, Crossover, and Selection for many generations until convergence (minimal change in best SSE).

Validation: Use the optimized parameters to simulate the process. Visually and statistically (e.g., via

R²) compare simulations with a separate validation dataset not used for optimization.

Objective: To identify an interpretable, closed-form algebraic expression for a kinetic rate (e.g., specific growth rate μ) directly from concentration data, without pre-specifying a model structure.

Materials: Cleaned time-series data for state variables (e.g., S, P). Software/platform supporting symbolic regression (e.g., Python with gplearn, pysr, or custom code).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation & Numerical Differentiation:

- Fit smoothing regressions (e.g., polynomial, spline) to your concentration vs. time data for

X,S,P. - Differentiate numerically to estimate rates

dX/dt,dS/dt,dP/dt. - Calculate the target variable, e.g., specific growth rate:

μ = (dX/dt) / X.

- Fit smoothing regressions (e.g., polynomial, spline) to your concentration vs. time data for

Perform Symbolic Regression:

- Define a set of mathematical primitives (e.g.,

+, -, *, /, exp, log, ^). - Define input variables (e.g.,

S, P). - The algorithm (e.g., genetic programming) will iteratively combine primitives and inputs into expression trees, evaluating their fitness (e.g., mean squared error against calculated

μ). - It evolves populations of expressions, promoting simpler, more accurate forms.

- Define a set of mathematical primitives (e.g.,

Model Extraction & Interpretation:

- Select the best expression(s) based on fitness and complexity (parsimony).

- The output is an equation like

μ = μ_max * S / (K + S + S^2/K_i). This can be directly interpreted as a Monod term with substrate inhibition and used in your ODE model.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimization Algorithms for Kinetic Parameter Estimation [9]

| Fermentation Mode | Optimization Algorithm | Best Strategy Found | Key Outcome (vs. Genetic Algorithm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch | Differential Evolution (DE) | best/1/bin | Lower objective function (SSE) |

| Fed-Batch (Exponential Feed) | Differential Evolution (DE) | best/1/bin, current-to-best/1/bin | Lower SSE; More robust convergence across different runs |

Table 2: Model Accuracy Benchmarks from Advanced Machine Learning Frameworks

| Framework | Application Context | Key Performance Metric | Interpretability Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic Regression [18] | General bioprocess kinetic model identification | Slightly outperformed neural network benchmarks | Closed-form algebraic rate equations |

| Structural Transfer Learning [19] | Adapting a kinetic model from a source to target system | Improved predictive accuracy on target system data | Identified structural corrections (e.g., new inhibition term) |

| RENAISSANCE [20] | Parameterization of large-scale metabolic models (E. coli) | >92% incidence of models with valid dynamic timescales | Population of kinetic parameter sets consistent with omics data |

Table 3: Analytical Troubleshooting Benchmarks for ELISA-based Kinetic Data [21]

| Issue | Recommended Validation Experiment | Acceptance Criteria | Common Root Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Background/Noise | Assay diluent alone as a sample | Absorbance ≈ Kit's zero standard | Contaminated reagents or work surface |

| Poor Dilution Linearity | Spike-and-recovery in sample matrix at multiple dilutions | 95-105% recovery across the range | Matrix interference or "Hook Effect" at high concentrations |

| Inaccurate Interpolation | Back-fit standard curve points as unknowns | Reported concentration within 10% of nominal value | Use of inappropriate (e.g., linear) curve fitting method |

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram Title: Decision Framework for Batch vs. Fed-Batch Mode Selection

Diagram Title: Structural Transfer Learning Workflow for Kinetic Models [19]

Diagram Title: RENAISSANCE Generative Framework for Kinetic Model Parameterization [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Solution Guide

Table 4: Essential Materials for Kinetic Parameter Estimation Studies

| Item / Solution | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Culture Media | Provides controlled nutrient environment for precise substrate consumption kinetics. | Use minimal media for simplified models; note complex media can introduce unmodeled interactions. |

| Feed Solution (for Fed-Batch) | Concentrated substrate source for controlled nutrient delivery. | Sterilize separately; composition must be known precisely for accurate model inputs. |

| Enzyme or Cell Line with Stable Kinetics | The biocatalyst whose kinetic parameters are being estimated. | Ensure genetic and phenotypic stability across all experimental runs for consistency. |

| Rapid Sampling & Quenching Kit | Allows capture of metabolic state at precise time points for dynamic models. | Quenching method (cold methanol, etc.) must stop metabolism instantaneously to avoid artifacts. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., Substrate, Product) | For generating calibration curves for HPLC, GC, or spectrophotometric assays. | Purity and accurate concentration are critical for converting raw signals to model variables (S, P). |

| Assay-Specific Diluent (for ELISAs, etc.) [21] | Matrix for diluting concentrated samples to within assay range without interference. | Using the kit's recommended diluent is vital to avoid matrix effects that distort kinetic data. |

| Software for ODE Solving & Optimization | Platform to code kinetic models, integrate ODEs, and perform parameter estimation. | Must support global optimization algorithms (e.g., Differential Evolution) and statistical analysis. |

From Data to Parameters: A Step-by-Step Workflow for Kinetic Estimation in Different Bioprocesses

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges in the design and execution of studies focused on kinetic parameter estimation for enzyme-catalyzed processes. The content is framed within a broader thesis investigating the comparative advantages of fed-batch versus batch operation modes. Fed-batch processes, where substrates or other reagents are added incrementally, offer distinct advantages for parameter estimation, such as maintaining optimal reaction conditions, mitigating inhibitor effects, and exploring a wider operational space for model validation [1]. However, they introduce complexity in design, including the optimization of feeding profiles and sampling schedules to generate maximally informative data. This resource provides targeted troubleshooting advice, detailed protocols, and data-driven insights to support researchers and process scientists in navigating these complexities.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: During fed-batch enzymatic hydrolysis, my reaction rate declines significantly over time, reducing yield. What could be causing this and how can I mitigate it?

- Problem Identification: A decline in reaction rate during fed-batch operation is a common issue often attributed to inhibition, catalyst dilution, or shifting solution conditions.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Inhibitor Accumulation: Products (e.g., glucose in saccharification) can inhibit enzymes. Solution: Implement a fed-batch strategy with periodic removal of hydrolysate or integrate with a continuous fermentation step to simultaneously remove inhibitors [8].

- Catalyst Dilution or Inactivation: Continuous feeding dilutes enzyme concentration, and shear stress from mixing can cause inactivation. Solution: Consider a fed-batch strategy with supplemental enzyme dosing or use enzyme recycling techniques [8].

- Shift in pH or Ionic Strength: Metabolic activity or reagent feeds can alter pH and salt concentration, negatively impacting enzyme activity. Solution: Use robust buffer systems. For complex processes like in vitro transcription (IVT), implement model-predictive control to adjust feeds and maintain optimal conditions, as uncontrolled pH drop can be a primary cause of rate decline [22].

- Substrate Depletion or Limitation: An improperly designed feed profile can lead to periods of substrate limitation. Solution: Optimize the feed profile using model-based strategies to maintain substrate concentration within an optimal range [22].

Q2: My parameter estimates from batch and fed-batch experiments are inconsistent. Which mode provides more reliable estimates?

- Problem Identification: Discrepancies often arise because different operational modes test the kinetic model under different conditions, revealing model shortcomings.

- Guidance:

- Fed-batch as a Superior Tool for Estimation: Theoretical and practical studies indicate fed-batch operations can provide more robust parameter estimates. Analysis of the Fisher information matrix for Michaelis-Menten kinetics shows that a substrate-fed-batch process can reduce the lower bound of the parameter estimation error variance to 82% for μmax and 60% for Km compared to batch experiments [4].

- Actionable Steps: Use fed-batch experiments to actively "stress-test" your model across a wider range of metabolite concentrations. The increased operational space makes the parameter estimation problem better posed. If estimates differ, use the fed-batch data as the primary set for model calibration, as it is inherently more informative, then validate if the calibrated model can predict batch data [4] [8].

Q3: How do I design an optimal sampling schedule for parameter estimation in a fed-batch process?

- Problem Identification: Inefficient sampling wastes resources and yields poorly identifiable parameters.

- Optimal Design Principles:

- Leverage Model-Based Design: The most powerful approach uses a preliminary model and Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) analysis to predict which sampling times will maximize the information content (e.g., minimize parameter covariance) [4].

- Focus on Dynamic Phases: Increase sampling frequency during periods of rapid change (e.g., immediately after a feed pulse, during the exponential growth phase). For a logistic growth model in mammalian cell culture, robust parameter estimation requires sufficient points during the inflection point of the growth curve [23].

- Practical Protocol: 1) Run a preliminary, well-instrumented experiment with frequent sampling. 2) Fit an initial model to this data. 3) Use FIM analysis or a Bayesian Experimental Design (BED) framework to compute optimal sampling times for subsequent, high-precision experiments [24].

Q4: What is the most efficient way to optimize a fed-batch feed profile? Trial-and-error is too costly.

- Problem Identification: Empirical optimization of multi-variable feed profiles is prohibitively resource-intensive.

- Recommended Strategies:

- Mechanistic Model-Based Optimization: Develop a dynamic kinetic model (e.g., for IVT or fermentation) and use optimal control theory to compute a feed profile that maximizes yield or productivity [22]. This is the gold standard for fundamental understanding.

- Data-Driven, Batch-to-Batch Optimization: For complex systems where mechanistic modeling is difficult, use data from each run to iteratively improve the next. A recursively updated Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) model can adapt to process variations and generate an improved control profile for each subsequent batch [25].

- Bayesian Experimental Design (BED): For multi-objective optimization (e.g., maximizing yield while minimizing cost), BED efficiently explores the parameter space by using a surrogate model to select the most promising feed conditions for the next experiment, dramatically improving data efficiency [24].

Q5: Are there economic justifications for developing a fed-batch process over a simpler batch process?

- Consideration: The development cost for an optimized fed-batch process is higher, but the operational benefits can be significant.

- Economic Analysis: A techno-economic simulation of cellulosic ethanol production comparing batch and fed-batch enzymatic hydrolysis found clear advantages for fed-batch:

- Reduced Production Cost: Ethanol unit cost was approximately $0.10 per gallon lower for fed-batch.

- Lower Capital and Operational Costs: Fed-batch operation decreased facilities costs by 41%, labor costs by 21%, and capital investment costs by 15%, primarily due to higher product concentration and smaller required reactor volumes [26].

- Justification: The economic benefit is most pronounced in processes where the substrate or enzymes are expensive, or where downstream processing costs are significant [26].

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Comparative Kinetic Study of Batch vs. Fed-Batch Enzymatic Saccharification [8]

- Objective: To determine kinetic parameters and compare the performance of batch and fed-batch enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated lignocellulosic biomass.

- Materials: Pretreated Prosopis juliflora substrate, commercial cellulase enzyme complex, sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.8), stirred-tank reactor.

- Procedure:

- Batch Experiments: Conduct hydrolysis runs at different initial substrate consistencies (e.g., 5%, 10%, 15%, 20% w/v). Sample periodically to measure glucose concentration.

- Kinetic Parameter Estimation: Fit a kinetic model (e.g., based on cellulose hydrolysis rates) to the batch data to obtain initial parameter estimates.

- Fed-batch Experiment: Start with a lower initial substrate consistency (e.g., 10%). Based on model simulations, add discrete pulses of solid substrate (e.g., 50g) at predetermined times (e.g., 24h, 56h).

- Validation & Comparison: Measure glucose and insoluble solids over time. Compare final sugar concentration, conversion yield, and reaction rate profiles against batch mode.

Protocol 2: Model-Based Optimization of a Fed-Batch In Vitro Transcription (IVT) Reaction [22]

- Objective: To maximize RNA yield and capping efficiency in a fed-batch IVT process using a mechanistic model.

- Materials: DNA template, NTPs, RNA polymerase, cap analog, Mg2+, buffer components, bioreactor with feeding pumps.

- Procedure:

- Model Development: Formulate a mechanistic model integrating enzyme kinetics (polymerase binding, initiation, elongation) and solution thermodynamics (ionic speciation, pH).

- Parameter Estimation: Calibrate the model using data from batch experiments under varying conditions (NTP, Mg2+, salt concentrations).

- Optimal Control Formulation: Define an optimization problem to maximize total RNA yield subject to constraints (e.g., maintaining NTP concentration within a range, target cap fraction).

- Profile Computation & Validation: Solve the optimization to generate an optimal time-varying feed profile for NTPs. Test this profile experimentally against a standard batch or heuristic fed-batch protocol.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Batch vs. Fed-Batch Enzymatic Saccharification [8]

| Metric | Batch Operation (20% initial solids) | Fed-Batch Operation (20% cumulative solids) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final Sugar Concentration | 80.78 g/L | 127.0 g/L | +57% |

| Cellulose Conversion | 40.39% | 63.56% | +57% |

| Subsequent Ethanol Titer | 34.78 g/L | 52.83 g/L | +52% |

Table 2: Techno-Economic Comparison for a Cellulosic Ethanol Plant [26]

| Cost Category | Batch Hydrolysis Scenario | Fed-Batch Hydrolysis Scenario | Relative Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol Unit Production Cost | Base Case | Base Case - $0.10/gal | Decrease |

| Facilities Cost | Base Case | Base Case - 41% | Decrease |

| Labor Cost | Base Case | Base Case - 21% | Decrease |

| Capital Investment Cost | Base Case | Base Case - 15% | Decrease |

Table 3: Parameter Estimation Precision: Batch vs. Fed-Batch Design [4]

| Kinetic Parameter | Cramér-Rao Lower Bound (Variance) | Theoretical Improvement with Optimal Fed-Batch |

|---|---|---|

| μ_max (Maximum rate) | Batch = Reference (100%) | Can be reduced to ~82% of batch variance |

| K_m (Michaelis constant) | Batch = Reference (100%) | Can be reduced to ~60% of batch variance |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Fed-Batch Enzyme Kinetics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Typical Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Fed-Batch |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Preparation (e.g., Cellulase, RNA Polymerase) | Biological catalyst. Activity and stability define reaction kinetics. | Fed-batch may require stability over extended periods. Consider supplemental dosing or use of enzyme recycling strategies [8]. |

| Substrate (e.g., Cellulose, Nucleoside Triphosphates (NTPs)) | The reactant consumed to form product. | Feeding strategy is the core optimization variable. Goal is to maintain concentration in an optimal window to avoid inhibition or limitation [22] [8]. |

| Buffer Components | Maintains optimal pH and ionic strength for enzyme activity. | Must have sufficient capacity to counteract pH shifts from metabolism or reagent feeds. Phosphate buffers require care to avoid precipitation with Mg²⁺ [22]. |

| Cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺ for kinases/polymerases) | Essential for enzymatic activity. | Concentration is critical. In IVT, Mg²⁺ forms complexes with NTPs and phosphate; uncontrolled crystallization can occur, requiring thermodynamic modeling to prevent it [22]. |

| Inhibitors/Activators | Used to probe enzyme mechanism and validate models. | Fed-batch allows dynamic introduction/removal, enabling sophisticated perturbation studies for superior parameter identifiability [4]. |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Iterative Workflow for Fed-Batch Model Development & Validation (92 characters)

Diagram 2: Thesis Framework: Batch vs. Fed-Batch Value Comparison (82 characters)

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This resource provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers developing and calibrating mathematical models for enzyme kinetics in batch and fed-batch systems. The content is framed within a thesis context focused on comparing parameter estimation challenges and strategies across these fundamental bioprocess operation modes.

Foundational Concepts & Model Selection

Q1: What are the core mathematical components I must integrate to build a dynamic model for an enzymatic bioreaction? The framework rests on two pillars: mass balances and kinetic rate equations.

- Mass Balances (Differential Equations): These account for the accumulation of species (substrate, product, cells) in the system. For a batch reactor, a substrate balance is:

dS/dt = -r_s * X, whereSis concentration,r_sis the substrate uptake rate, andXis cell concentration [27]. Fed-batch systems include an additional inlet flow term (F_in * S_in). - Kinetic Rate Equations (Algebraic Models): These express the reaction rate

r_sas a function of state variables (e.g.,S,P) and unknown parameters (kcat,Km,Ki). A common form with product inhibition is:r_s = (kcat * E * S) / (Km + S + (S^2/Ki))[28]. The integrated system forms a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describe the process dynamics [27].

Q2: How do I choose between a batch and fed-batch model for my parameter estimation study? The choice should be driven by your experimental data and the inhibition phenomena under investigation.

Table: Guidance for Model System Selection

| System Choice | Recommended For | Key Advantage for Parameter Estimation | Thesis Context Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch Model | Preliminary studies, strong substrate inhibition, initial model validation [29]. | Simpler ODE structure; provides a clear progress curve for fitting [29]. | Baseline for comparison; fed-batch may mask or alleviate inhibition present in batch. |

| Fed-Batch Model | Substrate or product inhibition, high-solid processes, simulating industrial production [12] [28]. | Operating at higher final concentrations can expose nonlinear interactions; dynamic feed profile provides richer data [30]. | Essential for studying how controlled substrate delivery alters the identifiability of inhibition parameters (e.g., Ki). |

Q3: What are the most common pitfalls when formulating the initial mass balance equations? Common errors include:

- Ignoring Volume Change in Fed-Batch: Forgetting that the reactor volume

Vis time-varying (dV/dt = F_in), which affects concentration calculations. - Incorrect Inhibition Structure: Assuming Michaelis-Menten kinetics when strong product inhibition exists, leading to poor fits at high conversion [28].

- Over-parameterization: Using a complex kinetic model (e.g., multiple inhibitors) without sufficient experimental data points to reliably estimate all parameters.

Practical Implementation & Parameter Fitting

Q4: I have progress curve data. What methods can I use to estimate kinetic parameters, and how do I choose? A 2025 methodological comparison suggests the optimal approach depends on data quality and prior knowledge [29].

Table: Comparison of Parameter Estimation Methods from Progress Curves [29]

| Method | Description | Strengths | Weaknesses | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Integration | Uses the explicit integral of the rate law. | Direct, computationally fast. | Limited to simple kinetic models (e.g., basic M-M). | Use for simple models with high-quality data. |

| Numerical Integration + ODE Solver | Directly solves the ODE system during fitting. | Highly flexible for any model complexity. | Sensitive to initial parameter guesses; computationally heavier. | Default choice for complex models (e.g., with inhibition). |

| Spline Interpolation + Algebraization | Fits a spline to data, transforming the dynamic problem to algebraic. | Low sensitivity to initial guesses; robust [29]. | Requires dense data points for good spline fitting. | Use when good initial parameter estimates are unavailable. |

Experimental Protocol: Progress Curve Analysis for Batch Parameter Estimation [29]

- Design: Conduct a batch experiment with frequent sampling to capture the reaction dynamics, especially at early time points.

- Assay: Measure substrate/product concentration over time.

- Model Formulation: Propose a candidate kinetic model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten with product inhibition).

- Parameter Estimation: Use software (e.g., Python/SciPy, MATLAB, COPASI) to perform nonlinear regression. Implement the "Numerical Integration" method: use an ODE solver to simulate the progress curve for a given parameter set and minimize the sum of squared errors between simulated and measured data.

- Validation: Check parameter physical plausibility and confidence intervals. Use the fitted model to predict a separate dataset.

Q5: My parameter estimation algorithm fails to converge or returns unrealistic values. How do I troubleshoot this? Follow this systematic checklist:

- Check ODE Integration: Ensure your mass balance ODEs are coded correctly. Simulate with a manual parameter set to see if the output trend matches qualitative expectations.

- Rescale Parameters: Parameters like

kcatandKmcan span orders of magnitude. Fit the logarithm of the parameters to improve algorithm stability [27]. - Provide Sensible Initial Guesses: Use literature values or make rough estimates from your data (e.g.,

Kmis roughly the substrate level at half-max rate). - Consider Identifiability: Your data may not contain enough information to estimate all parameters. Fix some parameters (e.g., from literature) and estimate others.

- Use a Global Optimizer: Local optimizers can get stuck. Use a multi-start approach or a global optimization algorithm like the Nelder-Mead simplex or evolutionary algorithms [31] [30].

Fed-Batch Specific Challenges

Q6: How do I adapt my batch kinetic model for a fed-batch process with intermittent feeding?

The kinetic rate equation remains identical. The change is in the substrate mass balance, which gains an inflow term:

d(S*V)/dt = F_in * S_in - r_s * X * V

Since V changes, it's often practical to work in terms of total moles (M) instead of concentration: dM_s/dt = F_in * S_in - r_s * X * V. You must also track volume: dV/dt = F_in [28]. The feed profile F_in(t) (constant, exponential, or DO-stat [12]) is a known control input to the model.

Q7: Why would parameter values estimated from batch experiments fail to predict fed-batch performance? This is a central thesis question. Key reasons include:

- Unmodeled Inhibition: Batch experiments at low initial substrate may not reveal inhibition that becomes critical at the high cumulative substrate levels achieved in fed-batch [15].

- Changing Environmental Conditions: Fed-batch runs are longer; factors like gradual enzyme deactivation, not captured in short batch trials, become significant.

- Physiological Shifts in Cells: In cell-based expression systems, fed-batch growth at controlled rates can alter metabolic states and enzyme expression profiles compared to batch [12] [20].

Experimental Protocol: Fed-Batch Model Calibration & Validation [12] [28]

- Batch Phase Characterization: Perform initial batch runs to estimate basic growth (

μ_max) and substrate consumption parameters. - Fed-Batch Experiment Design: Execute fed-batch runs with different feeding strategies (e.g., constant feed vs. DO-stat [12]).

- Data Collection: Measure time-course data for biomass, substrate, product, and volume.

- Integrated Model Fitting: Calibrate the full fed-batch model (including feed equations) against the datasets. You may need to estimate additional parameters (e.g., a maintenance coefficient) not identifiable from batch alone.

- Cross-Validation: Validate the model calibrated on one feeding profile by predicting the outcome of a different feeding strategy.

Advanced Computational & Data Tools

Q8: How can machine learning assist in building kinetic models? ML offers tools across the modeling pipeline:

- Parameter Prediction: Frameworks like CatPred [32] and UniKP [33] use deep learning to predict

kcatandKmfrom enzyme sequence and substrate structure, providing valuable initial guesses. - Model Identification: ANNs can classify which kinetic model structure best fits a given dataset, streamlining model selection [31].

- Hybrid & Generative Modeling: Tools like jaxkineticmodel [27] enable efficient parameter fitting for large ODE systems. RENAISSANCE [20] uses generative ML to create populations of kinetic models consistent with omics data, bypassing traditional fitting.

Q9: What software tools are available for simulating and fitting fed-batch models?

- General Purpose: Python (SciPy, PyMC, JAX), MATLAB, and Julia offer ODE solvers and optimizers for custom models [27].

- Specialized Tools: The open-source fed-batch bioreactor modeling software provides a dedicated platform for CHO cell processes [30]. COPASI and SBML-compatible tools like jaxkineticmodel are also widely used [27].

Data Interpretation & Validation

Q10: How do I know if my estimated parameters are reliable and the model is good? Perform rigorous checks:

- Statistical Metrics: Examine confidence intervals (should be tight). Use R² and root-mean-square error (RMSE) [33].

- Visual Inspection: Plot simulated progress curves against experimental data. The fit should be good across the entire time range, not just one phase.

- Cross-Validation: The most important test. Calibrate the model using one dataset (e.g., batch data) and predict a different one (e.g., fed-batch outcome). A significant discrepancy suggests a flawed model structure [15].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test how small changes in parameters affect the output. Unidentifiable parameters will show negligible effect on the model fit.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Kinetic Modeling

| Item/Tool | Function & Role in Research | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cellic CTec3 Enzymes | Commercial cellulase cocktail for hydrolysis studies; used to generate progress curve data for model fitting [28]. | Novozymes |

| Pichia pastoris GAP Strains | Recombinant expression host for enzyme production; allows comparison of native vs. engineered enzymes under different feed strategies [12]. | [12] |

| DO-Stat & Constant Feed Controllers | Bioreactor hardware/software to implement fed-batch feeding strategies critical for generating relevant dynamic data [12]. | Standard bioreactor setup |

| SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) | Standard format for encoding and exchanging kinetic models, enabling use with various software tools [27]. | sbml.org |

| jaxkineticmodel Python Package | Simulation/training framework for SBML models using JAX; enables efficient parameter fitting for large models [27]. | [27] |

| CatPred / UniKP Framework | Deep learning tools to predict kcat, Km, and Ki from sequence/structure, providing prior knowledge for parameter estimation [32] [33]. |

[32] [33] |

| RENAISSANCE Framework | Generative ML framework to parameterize large-scale kinetic models consistent with omics data, useful for complex cellular systems [20]. | [20] |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center is designed within the context of advanced research comparing fed-batch and batch processes for enzyme and metabolite production. It addresses common computational and experimental challenges in parameter estimation, from foundational nonlinear regression to sophisticated optimal control theory.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My kinetic model fits are poor when analyzing progress curves from batch experiments. The parameters change drastically with my initial guesses. What robust numerical approach should I use? A common issue arises from the sensitivity of nonlinear regression to initial parameter values. A robust solution is to use a spline interpolation-based numerical approach [29].

- Recommended Action: Instead of directly integrating differential equations with guessed parameters, first fit a smoothing spline to your experimental progress curve data (e.g., substrate or product concentration over time). This spline provides smoothed estimates of the rate of the reaction at each time point. You can then perform a simpler algebraic regression of your kinetic model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten) against these estimated rates. This method significantly reduces dependence on initial parameter guesses and provides stability comparable to analytical integration approaches [29].

- Thesis Context: In batch enzyme studies, this method allows for reliable extraction of initial kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km) from a single progress curve, forming a solid basis for comparison with dynamic parameters estimated from fed-batch systems.

Q2: In fed-batch fermentations, my model predictions for biomass and product diverge from real-time sensor data after the initial batch phase. How can I improve real-time state estimation? This "plant-model mismatch" often stems from unaccounted microbial adaptation dynamics. Implementing a Bayesian estimation filter that treats key parameters as time-varying states can solve this [34].

- Recommended Action: Move beyond static parameters. Implement a Particle Filter or similar Bayesian estimator where the substrate uptake rate ((qS)) is defined as a dynamic state variable, not a constant. Introduce an "adaptability rate" parameter ((\lambda)) to capture how quickly cells adjust their uptake. This framework allows for simultaneous real-time estimation of system states (biomass, substrate) and adaptive parameters ((qS^{max}), yield) directly from online data like oxygen uptake rate (OUR), dramatically improving prediction accuracy during fed-batch transitions [34].

- Thesis Context: This advanced parameter estimation technique is crucial for fed-batch processes where cellular physiology changes between growth and production phases. It provides a dynamic parameter set that can be contrasted against the constant parameters typically derived from batch experiments.

Q3: I am designing a fed-batch process for enzyme production. Should I use a constant feed or a DO-stat feeding strategy to maximize volumetric productivity? The optimal strategy depends on the specific trade-off between final titer and process time. Recent research on Pichia pastoris producing β-fructofuranosidase provides clear comparative data [12].

- Decision Guide:

- Choose Constant Feed if your primary objective is maximizing volumetric productivity (g/L/h) and reducing total process time. This strategy leads to higher biomass and faster overall production [12].

- Choose DO-Stat Feed if your goal is to achieve the highest possible maximum enzyme activity (U/mL) in the broth, and process time is a secondary concern. This method maintains optimal metabolic activity for longer [12].

Experimental Data Reference: The table below summarizes the key findings from the referenced study to guide your decision [12]:

Table 1: Comparison of Fed-Batch Feeding Strategies for Enzyme Production in P. pastoris

Feeding Strategy Process Duration Max Volumetric Activity Volumetric Productivity Key Advantage Constant Feed ~59 hours Lower than DO-stat Higher Shorter time, higher overall output rate. DO-Stat Feed ~155 hours Higher Lower than constant Achieves highest final enzyme concentration.

Q4: For a growth-decoupled product (e.g., a secondary metabolite), how do I algorithmically determine the optimal feed rate and the ideal time to switch from growth to production phase in a fed-batch? This is an optimal control problem. Use a framework like OptFed that integrates nonlinear regression with orthogonal collocation and nonlinear programming [35].

- Recommended Action:

- Define & Fit: Collect data from a non-optimal fed-batch run. Use a general Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) model where cell-specific rates depend on multiple state variables. Fit the model to your data, then use a heuristic algorithm to prune insignificant terms and prevent overfitting [35].

- Optimize: Formulate an objective function (e.g., maximize product-to-biomass yield). Using the fitted model, solve the optimal control problem numerically (e.g., via orthogonal collocation) to compute the optimal trajectory for the feed rate (and other controls like temperature) and the precise switching time [35].

- Thesis Context: This represents the pinnacle of model-based fed-batch optimization, moving beyond heuristic rules. It allows for direct comparison against batch processes by quantitatively predicting the maximum performance achievable through dynamic control.

Q5: When scaling up a fed-batch lignocellulosic ethanol process, how can I rapidly model substrate heterogeneity and its impact on yields without complex CFD simulations? A machine-learning-aided dynamic compartment model (ML-CM) can serve as an efficient surrogate for Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) [36].

- Recommended Action: Develop or employ a compartment model where the bioreactor is divided into zones (e.g., well-mixed, stagnant). Use machine learning to predict how flow patterns and mixing times between these compartments change dynamically with operating conditions like stirring speed and broth volume. This hybrid model runs significantly faster than full CFD (e.g., 1/500th of the time) and allows for rapid exploration of feeding strategies and scale-up effects on substrate concentration gradients and microbial performance [36].

Q6: Can I use simple batch-derived kinetic parameters to design a fed-batch process? What are the key pitfalls? This is a central thesis question. Using batch parameters directly is not recommended and is a common source of process failure.

- Key Pitfalls & Solutions:

- Pitfall 1: Inhibition Dynamics: Batch systems often experience high initial substrate/inhibitor concentrations, while fed-batch systems aim to maintain low, constant levels. Parameters related to inhibition (e.g., K(_i)) may not be transferable [15].

- Solution: Perform fed-batch-style pulse experiments in batch reactors to estimate inhibition kinetics under dynamic conditions.

- Pitfall 2: Metabolic Shift: Cells may operate under different metabolic regimes (e.g., respiration vs. fermentation) in substrate-limited fed-batch versus substrate-rich batch phases. Growth-associated product formation coefficients are often not constant [37] [34].

- Solution: Use tools like FedBatchDesigner that explicitly require separate parameter sets for the growth and production phases, which must be estimated from phased experiments [37].

- Pitfall 3: Maintenance Metabolism: At high cell densities typical of fed-batch, maintenance energy demands become dominant and are poorly characterized in low-density batch experiments [35].

- Solution: Ensure your fed-batch model includes a maintenance coefficient and estimate it from chemostat or extended fed-batch data.

- Pitfall 1: Inhibition Dynamics: Batch systems often experience high initial substrate/inhibitor concentrations, while fed-batch systems aim to maintain low, constant levels. Parameters related to inhibition (e.g., K(_i)) may not be transferable [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Fed-Batch for Inhibitory Substrates (e.g., Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates) This protocol is adapted from simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) research [15]. Objective: To achieve high product titer from an inhibitory substrate by acclimatizing the culture and controlling inhibitor concentration via fed-batch addition.

- Yeast Adaptation: Cultivate the production yeast (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) aerobically on the pretreated hydrolysate liquid to adapt it to inhibitors. Aim for a cell mass concentration of 16-17 g/L [15].

- Initial Batch Phase: Begin fermentation in the bioreactor with a reduced dry matter content (e.g., 6% water-insoluble solids (WIS)) using the adapted yeast at an initial concentration of 2-5 g/L [15].

- Fed-Batch Phase: After inoculation, initiate the feeding of concentrated pretreated fibrous slurry. Use 4-5 pulsed additions over the first 24-25 hours to gradually increase the total dry matter content to the target (e.g., 10% WIS) [15].

- Monitoring: Track glucose/hexose concentration to ensure complete consumption. Expect final ethanol concentrations of 40-44 g/L and yields of 79-84% of theoretical after ~72 hours total process time [15].

Protocol 2: Parameter Estimation for Dynamic Substrate Uptake Models This protocol is based on real-time Bayesian estimation methods [34]. Objective: To generate data suitable for estimating time-varying substrate uptake parameters ((qS^{max}), (Y{XC})) in E. coli fed-batch cultures.

- Cultivation Setup: Use a defined minimal medium (e.g., DeLisa medium) with glycerol as the sole carbon source. Inoculate the bioreactor at a low initial biomass (~0.05 g/L). Maintain temperature at 37°C and pH at 6.8 [34].

- Data Acquisition: Ensure real-time monitoring of Oxygen Uptake Rate (OUR) and Carbon Evolution Rate (CER). Collect frequent offline samples for biomass (DCW), substrate (glycerol), and product analysis.

- Dynamic Feeding: After the initial batch phase, initiate a fed-batch phase with a defined but non-optimal feed profile (e.g., constant or linear feed). The goal is to create a dynamic environment that stresses the cells and reveals adaptation.

- Data Processing for Estimation: Use the online OUR/CER data and offline measurements as inputs for a Particle Filter estimator. The estimator should implement a dynamic model where (qS(t)) is a state variable with its own adaptability kinetics, allowing the parameters (qS^{max}) and (Y_{XC}) to be estimated adaptively throughout the fermentation [34].

Protocol 3: Model-Based Optimal Feed Profile Identification using OptFed This protocol outlines the application of the OptFed framework [35]. Objective: To identify the optimal feed and temperature profiles that maximize product-to-biomass yield in a recombinant protein fed-batch process.

- Preliminary Data Collection: Conduct 2-3 fed-batch fermentations under different, sub-optimal feeding strategies (e.g., varying constant rates or simple exponential feeds) and temperature setpoints. Measure key states over time: bioreactor volume, biomass (total and residual), product concentration, and substrate concentration [35].

- Model Definition and Fitting (Stage I & II):

- Define a general ODE model with equations for biomass, product, substrate, and volume. Formulate the specific substrate uptake rate ((\gamma^\circ)) as a flexible function of state variables (e.g., substrate, product, biomass) using inhibited Michaelis-Menten forms [35].

- Fit this general model to your collected data using nonlinear regression. Subsequently, apply a model reduction heuristic (e.g., term pruning based on significance) to obtain a parsimonious, validated process model [35].

- Optimal Control Solution (Stage III):

- Define your objective function, e.g.,

Maximize P(t_f) / X(t_f). - Using the reduced model, formulate and solve an optimal control problem with the feed rate

f(t)and temperatureT(t)as control variables. Employ a direct method like orthogonal collocation on finite elements to discretize the problem and solve it using nonlinear programming (NLP) [35]. - The solution provides the theoretical optimal trajectories for the controls to be implemented in a validation experiment.

- Define your objective function, e.g.,

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents, Software, and Models for Parameter Estimation Research

| Item | Function/Description | Relevance to Thesis |

|---|---|---|

| FedBatchDesigner Web Tool [37] | User-friendly interface for designing & optimizing two-stage fed-batch (2SFB) processes. Explores trade-offs between Titer, Rate, and Yield (TRY). | Enables rapid comparison of batch vs. 2SFB performance and optimal switching time analysis. |

| OptFed Modeling Framework [35] | A three-stage (define, fit, optimize) computational framework using ODE models and optimal control theory to predict optimal fed-batch controls. | Provides a method to move from batch/fed-batch data to an optimally controlled fed-batch process, maximizing yield. |

| Particle Filter (Bayesian Estimator) [34] | A sequential Monte Carlo method for state and parameter estimation. Ideal for nonlinear systems with time-varying parameters. | Critical for estimating dynamic, time-varying kinetic parameters in fed-batch that differ from static batch parameters. |

| Spline Interpolation for Progress Curves [29] | A numerical method that fits a smoothing spline to progress curve data before parameter regression, reducing initial guess sensitivity. | Provides robust parameter estimates from batch enzyme kinetics experiments, forming a reliable baseline. |

| Dynamic Compartment Model (ML-CM) [36] | A hybrid machine-learning model that predicts bioreactor heterogeneity and mixing dynamics at low computational cost. | Essential for scaling up fed-batch processes by predicting how gradients affect parameter efficacy. |

| Glycerol (Carbon Source) [12] | A non-fermentable, low-inhibition substrate often used in fed-batch for recombinant protein expression in yeast (e.g., with GAP promoter). | Enables controlled, high-cell-density fed-batch cultivations for enzyme production, avoiding methanol. |

| Defined Minimal Medium (e.g., DeLisa) [34] | A chemically defined medium allowing precise control over nutrient availability and accurate stoichiometric calculations. | Necessary for precise parameter estimation (yields, uptake rates) in both batch and fed-batch metabolic studies. |

Technical Workflow & Conceptual Diagrams

Troubleshooting Parameter Estimation Workflow (100 chars)

Bayesian Estimation Process for Substrate Uptake (78 chars)

OptFed Modeling Framework Overview (47 chars)

Technical Support Center: AI-Driven Enzyme Kinetics