Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization in Enzyme Kinetics: Advancing Drug Discovery and Bioprocess Design

Optimizing enzymatic systems, critical for drug discovery and bioprocess engineering, involves navigating complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces with competing objectives.

Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization in Enzyme Kinetics: Advancing Drug Discovery and Bioprocess Design

Abstract

Optimizing enzymatic systems, critical for drug discovery and bioprocess engineering, involves navigating complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces with competing objectives. This article explores the transformative role of Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) in addressing these challenges. We first establish the foundational principles of enzyme kinetics and the limitations of traditional single-objective approaches. The core of the discussion details the methodology of MOPSO and its advanced variants, such as SMPSO and Competitive Swarm Optimizers, for applications ranging from inhibitor mechanism elucidation to metabolic pathway engineering. We then address critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, including algorithm parameter tuning and integration with machine learning models like Bayesian Optimization and ensemble predictors to enhance robustness and predictive accuracy. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of MOPSO against other evolutionary algorithms and its experimental validation through case studies in drug-target binding analysis and bioconversion process control. This synthesis provides researchers and development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging MOPSO to solve complex, multi-faceted problems in enzyme kinetics and accelerate biomedical innovation.

The Convergence of Enzyme Kinetics and Multi-Objective Optimization: Foundational Challenges and Core Principles

Optimizing enzymatic catalysis is critical for enhancing the efficiency and scalability of bioprocesses, including pharmaceutical synthesis, food processing, and bioremediation [1]. However, achieving peak enzyme performance is a formidable challenge due to the complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces involved. Key interacting variables such as pH, temperature, ionic strength, cosubstrate concentration, and reaction time must be precisely tuned [1]. In multi-enzyme systems or cascades, this complexity is compounded by the need to balance the distinct optimal conditions for each enzyme while managing interactions like cross-inhibition or unstable intermediates [1].

Traditional optimization methods, such as one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches, are ill-suited for this task. They are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and frequently fail to identify true optima because they cannot account for synergistic or antagonistic interactions between parameters [1]. This creates a bottleneck in biocatalytic research and development. The core challenge, therefore, lies in efficiently navigating this multivariate landscape to identify condition sets that simultaneously maximize multiple, often competing, objectives—such as reaction rate, yield, stability, and cost—within a realistic experimental budget.

This document frames this challenge within the broader context of multi-objective optimization in enzyme kinetics research. It presents modern, data-driven solutions, including self-driving laboratories and machine learning (ML) frameworks, and provides detailed protocols for their implementation.

Core Frameworks for Multi-Parameter Optimization

1. Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) for Autonomous Exploration A transformative approach involves integrating automation with artificial intelligence to create self-driving laboratories. An SDL is a modular platform that autonomously executes experiments, analyzes data, and iteratively refines conditions based on algorithmic guidance [1]. A representative workflow involves:

- Hardware Integration: Combining a liquid handling station, robotic arm, multi-mode plate reader, and other analytical devices (e.g., UPLC-ESI-MS) under a unified software framework [1].

- Algorithmic Selection: Prior to experimental campaigns, conducting extensive in-silico simulations (e.g., >10,000 optimization runs on a surrogate model) to identify the most efficient optimization algorithm for the specific problem [1].

- Autonomous Operation: The system uses the selected algorithm (e.g., Bayesian Optimization with a tailored kernel) to propose new experimental conditions, execute them, measure outcomes, and update its model, all with minimal human intervention [1].

2. Machine Learning and Ensemble Predictive Modeling Machine learning models can predict optimal conditions from existing data, drastically reducing experimental screens. A powerful method involves creating ensemble models. For instance, combining predictions from Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) models can achieve superior predictive accuracy (R² = 0.95) compared to any single model [2]. These models are trained on comprehensive datasets that systematically capture enzyme activities across a wide range of physicochemical conditions [2]. Feature importance analysis (e.g., using SHAP values) can then reveal critical parameter interactions and guide mechanistic understanding [2].

3. Multi-Objective Optimization for Enzyme Cocktails Selecting optimal enzyme combinations for complex tasks like polymer degradation is a multi-objective problem. A computational framework for this involves [3]:

- Data Integration: Compiling kinetic parameters (from databases like BRENDA), sequence-derived features, and network topology metrics.

- Ensemble Classification: Training a classifier (e.g., achieving 86.3% accuracy) to predict enzyme-substrate relationships.

- Pareto-Optimal Selection: Applying a multi-objective optimization algorithm to evaluate enzyme pairs across criteria like prediction confidence, substrate coverage, operational compatibility (matching pH/temp optima), and functional diversity. This identifies a set of "Pareto-optimal" combinations where no single objective can be improved without worsening another [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Optimization Frameworks

| Framework | Primary Approach | Key Advantage | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Driving Lab [1] | Bayesian Optimization in automated experimental loop | Rapid, autonomous navigation of high-dimension parameter space | Accelerated optimization across 5+ parameters for multiple enzyme pairs |

| Ensemble ML Model [2] | XGBoost, MLP, and FCN ensemble | High predictive accuracy for parameter effects | R² = 0.95 for predicting optimal enzyme pretreatment conditions |

| Multi-Objective Selection [3] | Pareto-optimal ranking based on ensemble classifier | Identifies balanced enzyme combinations for multiple criteria | 156 Pareto-optimal pairs identified; top pair composite score > 0.89 |

Application Case Studies

Case Study 1: Sustainable Bast Fiber Pulping An ensemble ML model was trained on 1550 data points for cellulase, xylanase, and pectin lyase activities under varying pH, temperature, time, and additive concentrations [2]. The model predicted an optimal xylanase-pectinase system under non-obvious conditions. Experimental validation on paper mulberry bark showed a 17% improvement in tensile strength and a 25% improvement in burst strength compared to conventional optimization, confirming the model's ability to find superior solutions [2].

Case Study 2: Prioritizing Enzymes for Plastic Degradation A multi-objective framework evaluated enzymes for polymer degradation. It integrated kinetic data, sequence features, and network topology to rank enzyme pairs [3]. The analysis revealed a hub enzyme with broad specificity and identified the Cutinase–PETase pair for exceptional complementarity (score: 0.875 ± 0.008). Validation against experimental benchmarks confirmed enhanced depolymerization rates for the computationally recommended cocktails [3].

Case Study 3: Synthesis of Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs) A modular multi-enzyme cascade was designed to synthesize ncAAs from glycerol [4]. The key challenge was optimizing the cascade involving alditol oxidase (AldO), kinases, dehydrogenases, and the key enzyme O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS). Directed evolution of OPSS enhanced its catalytic efficiency for C–N bond formation by 5.6-fold [4]. The optimized, gram-scale cascade produced 22 different ncAAs with water as the sole byproduct, demonstrating optimization across enzyme engineering, cascade balancing, and process scaling [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Initial High-Throughput Screening for SDL Algorithm Training Objective: Generate a foundational dataset for in-silico optimization algorithm testing [1].

- Experimental Design: Define the multidimensional parameter space (e.g., pH 5-9, temperature 30-70°C, 3-5 substrate concentrations, 2-3 enzyme concentrations). Use a space-filling design (e.g., Latin Hypercube) to select 50-100 initial condition sets.

- Automated Execution: Program a liquid handling robot to prepare reactions in a microplate format according to the design. Use a plate reader to obtain continuous kinetic reads (e.g., every 30 seconds for 10 minutes) via absorbance or fluorescence.

- Data Processing: Use a tool like ICEKAT (Interactive Continuous Enzyme Analysis Tool) to consistently calculate initial reaction rates (v₀) from the kinetic traces [5]. ICEKAT offers multiple fitting modes (Maximize Slope Magnitude, Logarithmic Fit, Schnell-Mendoza) to accurately determine v₀ even with early curvature or signal noise [5].

- Surrogate Model Creation: Use linear interpolation or Gaussian Process regression on the collected (conditions → v₀) data to build a surrogate model that mimics the experimental response surface.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Optimization of Enzyme Pretreatment Objective: Optimize an enzymatic pretreatment process using an ensemble ML model [2].

- Dataset Curation: Compile a historical dataset where each entry contains reaction conditions (pH, T, time, [E], [S], [Additive]) and the corresponding output metric (e.g., fiber strength, product yield).

- Model Training & Validation:

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets.

- Train three distinct models: XGBoost, MLP, and FCN.

- Create an ensemble model that averages the predictions of the three base models.

- Validate using the test set; target R² > 0.9.

- Prediction & Experimental Validation:

- Use the trained model to predict outputs across a finely-gridded virtual parameter space.

- Select the top 3-5 predicted condition sets for experimental validation.

- Characterize the products (e.g., FTIR, XRD, mechanical testing) to confirm predicted improvements [2].

Protocol 3: Activity Screening for Enzyme Cascade Engineering Objective: Identify and characterize a key enzyme variant for a multi-enzyme cascade [4].

- Library Creation: Generate a library of enzyme variants (e.g., OPSS) via directed evolution or site-saturation mutagenesis.

- Coupled Activity Assay: For a synthase like OPSS, couple its reaction to a downstream analytical reaction. Example: The ncAA product can be derivatized with o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) to form a fluorescent adduct measurable in a plate reader [4].

- High-Throughput Screening: Express and purify variant libraries in a 96-well format. Run the coupled assay under standardized conditions.

- Hit Characterization: Select variants with >2-fold improved activity. Purify them at scale and determine full kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) for both natural and non-natural substrates to assess improved efficiency and broadened specificity [4].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Multi-Parameter SDL Optimization Workflow [1]

ML Ensemble Model Training Pathway [2]

Modular ncAA Synthesis Cascade [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents, Materials, and Software for Optimization Research

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling Station (e.g., Opentrons OT Flex) | Automated pipetting, heating, shaking, and plate manipulation. | Core hardware for SDLs, enabling reproducible execution of high-throughput screens [1]. |

| Multi-mode Plate Reader (e.g., Tecan Spark) | Measures absorbance, fluorescence, and luminescence in microplate format. | Provides the primary kinetic data (continuous assays) for optimization algorithms [1] [5]. |

| ICEKAT Software | Interactive web-based tool for calculating initial rates (v₀) from continuous kinetic data. | Standardizes and accelerates v₀ calculation, reducing bias and improving reproducibility for model training [5]. |

| Pyruvate/Lactate Dehydrogenase (PK/LDH) Coupled Assay Kit | Couples ADP production to NADH oxidation, measurable at 340 nm. | A standard assay for measuring ATP-consuming enzyme activities (e.g., kinases) in cascades [4]. |

| O-Phthalaldehyde (OPA) Reagent | Derivatizes primary amines to form highly fluorescent isoindole products. | Used for sensitive, high-throughput detection and quantification of amino acid products (e.g., ncAAs) [4]. |

| PlasticDB / BRENDA Database | Curated databases of enzyme kinetic parameters, substrates, and conditions. | Essential sources for building training datasets for machine learning models and multi-objective frameworks [3]. |

| Directed Evolution Kit (e.g., for random mutagenesis) | Creates genetic diversity for improving enzyme properties like activity or stability. | Used to engineer key enzymes (e.g., OPSS) for enhanced performance in cascades [4]. |

Traditional enzyme kinetics, anchored for over a century by the Michaelis-Menten (MM) equation, has provided a foundational framework for understanding catalytic rates. This approach typically focuses on a single objective: estimating the two canonical parameters, the catalytic constant (kcat) and the Michaelis constant (KM), often from initial velocity measurements under idealized conditions [6]. This single-objective, steady-state paradigm assumes a large excess of substrate over enzyme and treats parameters as independent, scalar values [7].

However, this canonical framework falls critically short when confronted with the complexity of real biochemical systems, both in vitro and in vivo. Its validity is restricted to conditions where the enzyme concentration is significantly lower than the substrate concentration, an assumption frequently violated in cellular environments where enzymes often operate at comparable or even higher concentrations than their substrates [7]. Furthermore, traditional analysis struggles with parameter identifiability, where highly correlated estimates for kcat and KM can fit data well but be far from their true biological values [7]. In industrial biocatalysis and drug development, where optimizing for multiple outcomes—such as maximum yield, minimum by-product formation, optimal stability, and cost-effective operation—is essential, a single-objective view is inherently inadequate [8].

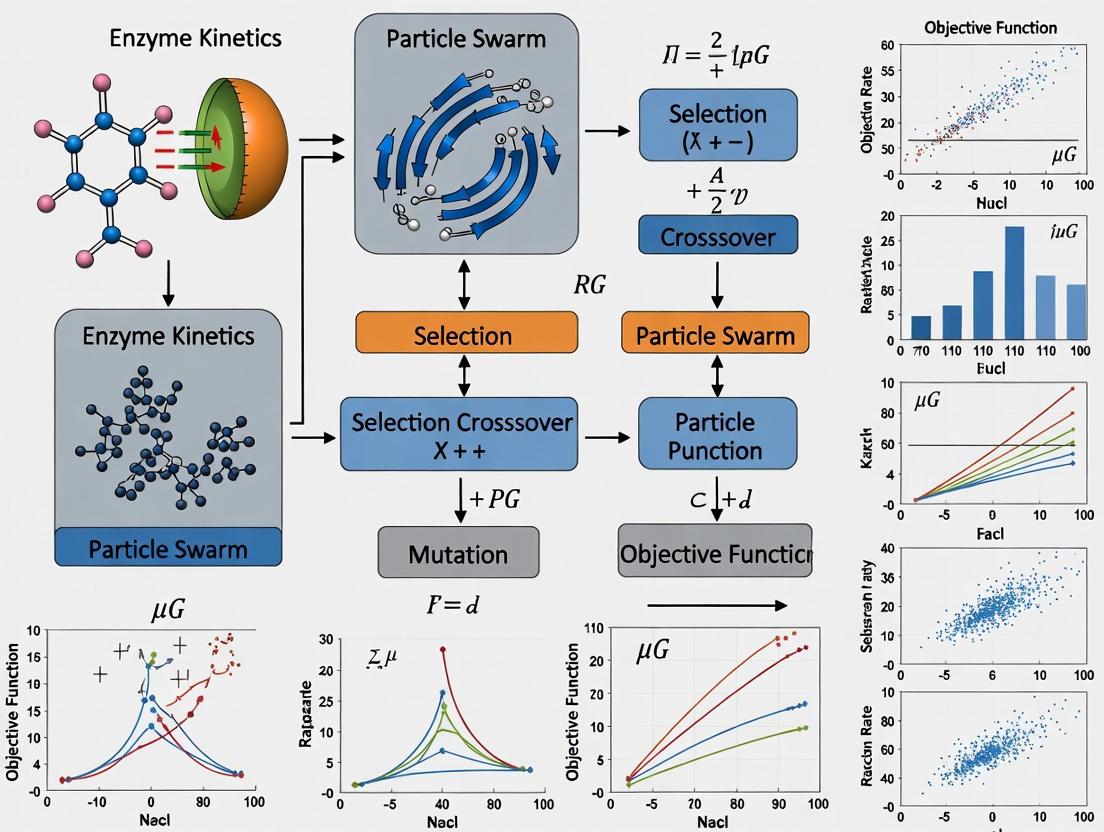

This article argues for a paradigm shift from single-objective analysis to multi-objective optimization (MOO) frameworks, underpinned by advanced computational intelligence like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). This shift is contextualized within a broader thesis that integrating MOO with more accurate kinetic models—such as those derived from the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA)—enables robust, predictive, and industrially relevant enzyme kinetics research.

The Quantitative Shortfall: A Data-Driven Critique of Traditional Methods

The limitations of traditional Michaelis-Menten analysis are not merely theoretical but have measurable consequences on parameter accuracy and experimental efficiency. The core issue often lies in applying the standard quasi-steady-state approximation (sQSSA) model outside its valid range.

Table 1: Comparative Accuracy of Kinetic Models Under Non-Ideal Conditions [7]

| Condition (Eₜ vs. Kₘ & Sₜ) | sQSSA (Classic MM) Model Accuracy | tQSSA Model Accuracy | Primary Cause of sQSSA Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eₜ << Kₘ, Sₜ | High | High | Ideal, low enzyme regime. |

| Eₜ ≈ Kₘ, Sₜ ≈ Kₘ | Low to Moderate | High | Violation of low enzyme assumption. |

| Eₜ > Kₘ, Sₜ | Low (High Bias) | High | Significant enzyme depletion invalidates sQSSA. |

| High Enzyme, Low Substrate (In Vivo-like) | Very Low | High | The sQSSA condition (Eₜ/(Kₘ+Sₜ) << 1) is broken. |

A critical advancement is the total QSSA (tQSSA) model, which remains accurate across a wider range of enzyme and substrate concentrations [7]. Bayesian inference applied to the tQSSA model demonstrably yields unbiased parameter estimates regardless of concentration ratios, enabling researchers to pool data from diverse experimental conditions for a more robust global analysis [7].

Furthermore, traditional progress curve analysis faces an experimental design conundrum: designing an informative experiment (e.g., choosing initial substrate concentration) often requires prior knowledge of the very parameter (KM) one seeks to determine [7]. Advanced computational approaches circumvent this by enabling optimal experimental design where the next most informative condition can be predicted iteratively.

The Multi-Objective Optimization Framework: Integrating PSO with Enzyme Kinetics

Industrial biocatalysis is inherently a multi-objective problem. For instance, in the continuous microbial production of 1,3-propanediol, objectives simultaneously include maximizing mean productivity, minimizing system sensitivity to parameter uncertainty, and minimizing control variation costs for operational stability [8]. A single-optimal solution does not exist; instead, there exists a Pareto front—a set of optimal trade-off solutions where improving one objective worsens another.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), a metaheuristic inspired by social behavior, is exceptionally suited for navigating complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces common in kinetic models [9]. In multi-objective PSO (MOPSO), a swarm of candidate solutions (particles) evolves over generations, guided by both personal and communal best positions, to map the Pareto frontier efficiently [8].

Table 2: Application Spectrum of PSO in Enzyme Kinetics and Bioprocessing

| Application Area | Traditional Single-Objective Approach | Multi-Objective PSO Enhancement | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimation | Nonlinear regression minimizing one residual sum-of-squares. | Simultaneous fit to multiple data sets (progress curves, yields, spectra) or objectives (speed, accuracy). | Improved identifiability, robust parameters valid across conditions [7] [9]. |

| Bioprocess Control | Optimize dilution rate for max productivity only. | Optimize time-varying control to balance productivity, robustness, and control cost [8]. | Identifies practical, stable operating policies. |

| Reaction Optimization | One-factor-at-a-time variation of pH, T, [S]. | Global navigation of multi-parameter space (pH, T, [S], [E], flow) for Pareto-optimal yield/purity/speed [1]. | Drastically reduces experimental runs to find optimal zones. |

| Model Discrimination | Sequential testing of rival kinetic models. | Concurrent evaluation of multiple model structures against multiple fit criteria. | Efficient selection of most parsimonious, predictive model. |

Advanced variants like the Multi-Objective Competitive Swarm Optimizer (MOCSO) introduce pairwise competition and mutation operations to enhance particle diversity and prevent premature convergence on local optima, providing a better spread of solutions across the Pareto front [8].

Experimental Protocols: From Traditional Assays to Autonomous Optimization

Protocol 1: Bayesian Progress Curve Analysis with the tQSSA Model

This protocol enables accurate estimation of kcat and KM from a single progress curve, even under non-ideal conditions [7].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reaction mixtures with deliberately varied enzyme-to-substrate ratios. Include conditions where

[E]ₜis comparable to or greater than[S]ₜto challenge the model. - Continuous Monitoring: Use spectrophotometric, fluorometric, or calorimetric methods to collect product concentration

[P]versus time data at high temporal resolution. - Data Modeling with tQSSA: Fit the data to the tQSSA ordinary differential equation (ODE):

dP/dt = k_cat * E_T * (K_M + S_T + E_T - P - sqrt((K_M + S_T + E_T - P)^2 - 4 * E_T * (S_T - P))) / 2using numerical integration. - Bayesian Inference: Employ a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling framework (e.g., PyMC, Stan) with weakly informative priors (e.g., Gamma distributions) for

k_catandK_Mto obtain posterior distributions. - Validation: Assess model identifiability by examining posterior distributions for tightness and correlation. Validate by predicting progress curves from a held-out experimental condition.

Protocol 2: Implementing Multi-Objective PSO for Bioprocess Optimization

This protocol outlines steps to optimize a fed-batch or continuous enzymatic process [8].

- Define Objectives: Formulate 2-3 quantifiable objectives (e.g.,

J1: Maximize final product titer,J2: Minimize total substrate consumption,J3: Minimize variance in product quality). - Formulate Dynamic Model: Develop a system of ODEs describing the reaction kinetics, mass transfer, and operational constraints.

- Discretize Control Variables: Parameterize the time-varying control variable (e.g., feed rate) into a finite set of decision variables.

- MOPSO Execution: a. Initialize a swarm of particles with random positions (control profiles) and velocities. b. Evaluate each particle by simulating the dynamic model to compute all objective functions. c. Update personal and global best positions. For MOPSO, maintain an external archive of non-dominated Pareto-optimal solutions. d. Update particle velocities and positions using competitive or crowding distance mechanisms to preserve diversity [8]. e. Iterate until convergence.

- Pareto Front Analysis: Present the set of optimal trade-off solutions to decision-makers for selection based on higher-level criteria.

Protocol 3: Autonomous Reaction Optimization in a Self-Driving Lab

This protocol leverages machine learning and robotics for fully automated kinetic screening [1].

- Platform Setup: Integrate a liquid handling robot, microplate reader, and automated reagent storage into a closed-loop system controlled by a central Python framework.

- Define Search Space: Specify ranges for key parameters (e.g., pH 5-9, temperature 20-60°C, [S] 0.1-10 mM, [cofactor] 0-5 mM).

- Select Optimization Algorithm: Implement a Bayesian Optimizer (e.g., with Gaussian Process surrogate and Expected Improvement acquisition function) to guide experiments.

- Autonomous Execution Loop: a. The algorithm proposes a batch of promising reaction conditions. b. The robotic platform prepares reactions, incubates, and quantifies output (e.g., initial rate or endpoint yield). c. Results are fed back to the algorithm to update its surrogate model. d. The loop repeats, rapidly converging on global optima.

- Modeling & Validation: Use the collected high-dimensional data set to train predictive machine learning models or refine mechanistic kinetic models.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Advanced Enzyme Kinetics

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Total QSSA Kinetic Modeling Software | Enables accurate parameter fitting from progress curves without restrictive low-enzyme assumptions. | Bayesian inference packages (e.g., custom code from [7], PyMC, Stan) implementing the tQSSA ODE model. |

| Multi-Objective PSO Algorithm Library | Solves optimization problems with multiple, competing objectives to map trade-off spaces. | Libraries like pymoo (Python) or custom implementations of MOCSO [8] for bioprocess control optimization. |

| Robotic Liquid Handling & Analysis Platform | Enables high-throughput, reproducible execution of enzymatic assays for autonomous optimization. | Opentrons Flex, Tecan Spark plate reader integrated via Python API [1]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Framework | Guides autonomous experimental design by modeling the parameter-performance landscape. | Frameworks like BoTorch or Scikit-optimize used in self-driving labs [1]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates | Allows precise tracking of reaction progress and mechanistic studies via techniques like NMR or MS. | Used in detailed kinetic isotope effect studies or with real-time MS monitoring in SDLs [1]. |

| Specialized Assay Kits (Coupled Enzymatic, Fluorogenic) | Provides sensitive, continuous, and high-throughput readouts of enzyme activity under diverse conditions. | Essential for generating large, high-quality data sets for machine learning model training in autonomous platforms. |

Visualizing the Workflow: From Single to Multi-Objective Paradigms

The following diagrams illustrate the conceptual and practical shift from traditional analysis to integrated, multi-objective frameworks.

Diagram 1: Paradigm shift from single to multi-objective analysis.

Diagram 2: Autonomous experiment cycle in a self-driving lab.

The field of enzyme kinetics is undergoing a fundamental transformation. Moving beyond single-objective analysis is not merely an incremental improvement but a necessary evolution to address the complexity of biological systems and industrial demands. The integration of accurate, generalizable kinetic models like tQSSA, with powerful multi-objective optimization algorithms like MOPSO, provides a robust framework for reliable parameter estimation and process development. Furthermore, the emergence of autonomous, machine learning-driven laboratories signifies a leap toward unprecedented efficiency, capable of navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces and discovering optimal conditions faster than ever before [1].

This multi-objective, computationally intelligent approach directly supports critical applications in rational drug design (by accurately characterizing target enzyme inhibition under physiological conditions), synthetic biology (by optimizing metabolic pathways), and sustainable biocatalysis (by balancing yield, selectivity, and operational efficiency). The future of enzyme kinetics lies in embracing this complexity, leveraging computational tools not just for analysis, but for autonomous discovery and design.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a computational method inspired by the social dynamics of bird flocking and fish schooling [10]. As a population-based stochastic optimization technique, it is particularly valuable for navigating complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces common in biochemical systems [11]. In enzyme kinetics and drug discovery research, conventional fitting algorithms often converge to local minima when dealing with multi-parametric, non-convex problems [12]. PSO addresses this by maintaining a swarm of candidate solutions (particles) that collectively explore the solution space, each adjusting its trajectory based on personal experience and swarm intelligence [10]. This metaheuristic approach makes minimal assumptions about the underlying problem, does not require gradient information, and is robust in the presence of experimental noise, making it ideal for elucidating complex biological mechanisms from data-rich biophysical assays [11]. Its application is transformative for multi-objective optimization in enzyme kinetics, where researchers must simultaneously fit parameters for reaction velocities, binding constants, and oligomeric equilibria without prior bias [10] [13].

Core Principles and Algorithmic Workflow

The PSO algorithm operates by initializing a population of particles within a predefined search space, where each particle represents a potential solution to the optimization problem (e.g., a set of kinetic parameters). Each particle has a position and a velocity. The algorithm proceeds iteratively, with particles evaluating their position based on a fitness function (e.g., the sum of squared residuals between model and experimental data). Two key values guide a particle's movement: its personal best (pbest), the best position it has individually found, and the global best (gbest), the best position found by any particle in its neighborhood [11].

The velocity (vi) and position (xi) of particle (i) are updated each iteration according to the following equations: (vi(t+1) = w \cdot vi(t) + c1 \cdot r1 \cdot (pbesti - xi(t)) + c2 \cdot r2 \cdot (gbest - xi(t))) (xi(t+1) = xi(t) + vi(t+1)) where (w) is an inertia weight, (c1) and (c2) are acceleration coefficients, and (r1), (r2) are random numbers between 0 and 1 [11]. This process allows the swarm to efficiently explore and exploit the solution space.

In the context of enzyme kinetics, the fitness function is critical. For a model defined by differential equations (e.g., Michaelis-Menten with extensions for oligomerization), PSO minimizes the difference between experimental observations—such as substrate depletion over time [12], thermal melt curves [10], or oxirane oxygen content [9]—and model predictions. Unlike traditional linearization methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plots) which can distort error structures, PSO performs nonlinear regression directly on the data, leading to more accurate and precise parameter estimates ((V{max}), (Km), (K_i), etc.) [12]. The algorithm's strength lies in its ability to avoid local minima, a common pitfall when fitting complex, multi-parametric models to enzyme kinetic data [11].

Table: Key PSO Applications in Enzyme Kinetics and Bioprocess Optimization

| Application Area | Specific Use Case | Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Inhibition | Determining mechanism of allosteric inhibitors of HSD17β13 via Fluorescence Thermal Shift Assay (FTSA) | Identified inhibitor-induced shift in oligomerization equilibrium (monomer dimer tetramer) | [10] [11] |

| Bioprocess Control | Multi-objective optimal control of glycerol-to-1,3-PD bioconversion | Optimized time-varying dilution rate to maximize productivity while minimizing system sensitivity & control cost | [8] |

| Chemical Kinetics | Kinetic parameter estimation for castor oil epoxidation | Achieved high model accuracy (R² = 0.98) for a unidirectional reaction model | [9] |

| Parameter Estimation | Comparison of methods for fitting Michaelis-Menten kinetics | Demonstrated superiority of nonlinear methods (like PSO) over linearization techniques (Lineweaver-Burk) | [12] |

| Hybrid Modeling | ANN-PSO for optimizing enzymatic dye removal (Jicama peroxidase) | Achieved superior modeling capability (R² > 0.93) compared to Response Surface Methodology | [14] |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Global Analysis of Enzyme Inhibition via Fluorescence Thermal Shift Assay (FTSA) This protocol details the use of PSO to analyze FTSA data for an enzyme in oligomerization equilibrium, as demonstrated for HSD17β13 [10] [11].

- Experimental Data Collection:

- Perform FTSA experiments on the target enzyme (e.g., HSD17β13) across a range of inhibitor concentrations. Monitor fluorescence as a function of temperature to generate melt curves [11].

- Record the raw fluorescence intensity versus temperature data for each condition.

- Model Formulation:

- Develop a thermodynamic model that describes the protein's oligomeric states (e.g., monomer, dimer, tetramer) and their respective melting temperatures [10].

- Incorporate equations describing the ligand binding equilibrium to each oligomeric state. This creates a multi-parametric model with parameters for dissociation constants ((K_D)), enthalpies ((\Delta H)), and entropies ((\Delta S)) of unfolding and binding.

- PSO Implementation for Parameter Estimation:

- Define Search Space: Set plausible lower and upper bounds for each fitted parameter (e.g., (pK_D), (\Delta H)).

- Initialize Swarm: Generate an initial population of particles with random positions and velocities within the bounded space.

- Define Fitness Function: Implement a function that calculates the sum of squared residuals between the experimental melt curves and the curves simulated by the model for a given particle's parameters.

- Execute Optimization: Run the PSO algorithm (e.g., using provided GitHub code [10]) for a set number of iterations or until convergence. The swarm will identify the global best parameter set.

- Validation: Refine the PSO solution with a local gradient descent method (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) for fine-tuning [11]. Validate the final model with orthogonal biophysical data, such as mass photometry, to confirm the predicted oligomeric state shift [10] [11].

Protocol 2: Kinetic Parameter Estimation for Epoxidation Reactions This protocol applies PSO to fit kinetic models to time-series data from chemical reactions, exemplified by the epoxidation of castor oil [9].

- Experimental Data Collection:

- Conduct the epoxidation reaction (e.g., using in situ generated peracetic acid with ZSM-5/H₂SO₄ catalyst). Maintain controlled conditions (e.g., 65°C, 200 rpm) [9].

- Withdraw aliquots at regular time intervals (e.g., every 10 minutes for 60 minutes).

- Quantify the reaction product (e.g., oxirane oxygen content) for each aliquot using titration (AOCS Cd 9-57 method) [9].

- Kinetic Model Definition:

- Propose a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based on the reaction mechanism (e.g., peracid formation, epoxidation, and ring-opening side reactions).

- For the Prilezhaev reaction, a simplified unidirectional model focusing on the 30-60 minute interval may yield a more accurate fit than a complex reversible model for the entire time course [9].

- PSO Implementation:

- Parameterization: The particles in the swarm represent vectors of the unknown kinetic rate constants in the ODE system.

- Simulation & Fitness Evaluation: For each particle, numerically integrate the ODE system using its candidate rate constants to predict product concentration over time. The fitness is the R² value or the sum of squared errors between the predicted and titrated oxirane content.

- Optimization: Execute PSO to find the rate constants that maximize R². The study achieved an R² of 0.98 for the unidirectional model [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PSO-Guided Enzyme Kinetics

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Binds to hydrophobic regions of unfolded proteins, enabling detection of thermal denaturation in FTSA. | Determining protein melting temperature ((T_m)) and ligand-induced thermal shifts [10] [11]. |

| Target Enzyme (e.g., HSD17β13) | The protein of interest whose kinetic and thermodynamic parameters are being characterized. | Studying enzyme inhibition mechanisms and oligomerization equilibria [11]. |

| Small-Molecule Inhibitor | Compounds that bind to the enzyme to modulate its activity; the subject of mechanism-of-action studies. | Screening and validating drug candidates in drug discovery pipelines [10]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Serves as an oxidizing agent in enzymatic reactions or for in situ generation of peracids. | Epoxidation kinetics studies [9] and as a substrate for peroxidases in dye removal studies [14]. |

| Hydrobromic Acid (HBr) in Acetic Acid | Titrant used for determining oxirane oxygen content via the standard titration method. | Quantifying the yield of epoxidation reactions over time for kinetic modeling [9]. |

| Immobilized Enzyme System (e.g., Jicama Peroxidase on BP/PVA) | A reusable biocatalyst with enhanced stability for process optimization studies. | Modeling and optimizing enzymatic degradation processes (e.g., dye removal) using ANN-PSO hybrid models [14]. |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

PSO Optimization Loop for Kinetic Fitting

Enzyme Oligomerization and Inhibition System

The optimization of enzymatic systems represents a cornerstone of modern biochemical research, with direct implications for pharmaceutical synthesis, bioremediation, industrial bioprocessing, and therapeutic development. Traditional optimization approaches, which focus on a single objective such as maximizing yield or initial reaction velocity, often fail to capture the complex, competing priorities inherent in real-world applications. For instance, maximizing enzyme productivity in a fermenter may come at the cost of undesirable system sensitivity to parameter fluctuations or excessive control input variation, jeopardizing process robustness [8]. Similarly, in drug discovery, an inhibitor must balance binding affinity with specificity and pharmacokinetic properties, a problem that is fundamentally multi-dimensional [11].

This article frames enzyme optimization explicitly as a Pareto search problem, where improvements in one objective (e.g., catalytic rate) can only be achieved by accepting trade-offs in others (e.g., stability, cost, or selectivity). The solution is not a single optimum but a set of Pareto-optimal solutions—a frontier where no objective can be improved without degrading another. Within this paradigm, Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) emerges as a powerful metaheuristic tool. Evolving from its predecessor, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), MOPSO is uniquely suited to navigate the high-dimensional, nonlinear, and often noisy search spaces defined by enzyme kinetics and bioprocess engineering. By efficiently approximating the Pareto front, MOPSO provides researchers and process engineers with a comprehensive map of optimal compromises, enabling data-driven decisions that align with specific economic, thermodynamic, or therapeutic constraints [8] [15].

This work, situated within a broader thesis on MOPSO in enzyme kinetics, provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols. It bridges the theoretical foundations of swarm intelligence with practical methodologies for optimizing enzymatic systems, from single-molecule kinetic parameters to industrial-scale fermentation processes.

Algorithmic Foundations: From PSO to MOPSO

The transition from single-objective PSO to MOPSO involves fundamental architectural shifts to manage and balance multiple, often conflicting, goals.

Standard Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based stochastic optimization technique inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking or fish schooling. In PSO, a swarm of particles (candidate solutions) navigates the search space. Each particle ( i ) has a position ( xi ) and velocity ( vi ), which are updated iteratively based on its own best-known position (( pBest_i )) and the best-known position found by the entire swarm (( gBest )):

[ vi^{t+1} = \omega vi^t + c1 r1 (pBesti - xi^t) + c2 r2 (gBest - xi^t) ] [ xi^{t+1} = xi^t + vi^{t+1} ]

where ( \omega ) is the inertia weight, ( c1 ) and ( c2 ) are acceleration coefficients, and ( r1, r2 ) are random numbers. The algorithm's strength lies in its simplicity and rapid convergence but it is designed to find a single global optimum [16] [17].

Multi-Objective PSO (MOPSO) extends this framework to handle multiple objectives. The core challenge is redefining the concepts of best personal position and, crucially, the global best, as no single solution is optimal across all objectives. Key adaptations include:

- Archive (External Repository): Stores non-dominated solutions found during the search, approximating the Pareto front.

- Leader Selection: Instead of a single ( gBest ), a guide for each particle is selected from the archive, often using techniques like crowding distance or roulette wheel selection to promote diversity along the front.

- Density Estimation: Methods like kernel density or nearest-neighbor distance are used to prune the archive and maintain a well-distributed set of Pareto solutions.

- Mutation Operators: Introduced to enhance exploration and prevent premature convergence to a sub-region of the front.

Advanced variants incorporate more sophisticated mechanisms. For example, the Multi-Objective Competitive Swarm Optimizer (MOCSO) replaces the traditional pBest/gBest model with a pairwise competition mechanism, where losers learn from winners, improving convergence and diversity [8]. The GPSOM algorithm divides the swarm into specialized subgroups focused on exploration, exploitation, and equilibrium, applying tailored update strategies to each [17]. These enhancements make MOPSO particularly effective for the complex, constrained, and high-dimensional landscapes common in enzyme optimization problems.

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Comparison for Enzyme Optimization

| Feature | Standard PSO | Basic MOPSO | Advanced MOPSO (e.g., MOCSO, GPSOM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Handling | Single (e.g., V_max) | Multiple, simultaneous | Multiple, with enhanced balance |

| Solution Output | Single global optimum | A set of non-dominated solutions (Pareto front) | A well-distributed, converged Pareto front |

| Leader Selection | Global best (gBest) | Selection from non-dominated archive | Competitive or grouped selection for diversity |

| Key Strength | Fast convergence, simple implementation | Maps trade-offs between objectives | Superior diversity, avoids local fronts, handles noise |

| Typical Enzyme Application | Fitting a kinetic model to a single dataset | Balancing yield, time, and cost in a process | Optimizing complex processes with stability & sensitivity constraints [8] |

Diagram 1: Conceptual evolution from PSO to advanced MOPSO architectures.

Application Notes & Quantitative Outcomes

MOPSO has been successfully applied across a spectrum of enzyme-related optimization problems, from parameter estimation to full bioprocess control. The following table summarizes key applications and their quantitative outcomes.

Table 2: Summary of Multi-Objective Enzyme Optimization Applications Using MOPSO

| Application Area | Primary Objectives | Key Decision Variables | Reported Outcome & Pareto Insight | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycerol Bioconversion to 1,3-PD | 1. Maximize mean productivity.2. Minimize system sensitivity.3. Minimize control cost (variation). | Time-varying dilution rate ( D(t) ) in a continuous fermenter. | Generated Pareto front showing trade-offs. High-productivity strategies increased sensitivity. MOCSO algorithm found robust solutions. | [8] |

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Corn Stover | Minimize error between model predictions and experimental data for glucose and cellobiose yields simultaneously. | Kinetic parameters (e.g., (K{m}), (V{max}), inhibition constants). | Reduced mean squared error by 34% for glucose and 2.7% for cellobiose versus previous studies, improving model fidelity under inhibition. | [18] |

| Industrial Balhimycin (Antibiotic) Production | 1. Maximize product concentration.2. Maximize productivity.3. Minimize substrate usage. | Glycerol and phosphate feed profiles in a batch fermenter. | Identified substrate inhibition thresholds (e.g., glycerol >59.84 g/L reduces yield). Pareto front guides feed strategy to balance output and cost. | [15] |

| HSD17β13 Inhibitor Mechanism Analysis | Accurately fit Fluorescent Thermal Shift Assay (FTSA) melting curves under a complex monomer-dimer-tetramer equilibrium model. | Binding constants, enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS) changes for multiple equilibria. | PSO enabled global parameter estimation, identifying that inhibitor binding shifts oligomerization equilibrium toward the dimeric state, explaining a large thermal shift. | [11] |

| Machine-Learning Driven Enzymatic Optimization | Autonomously maximize initial reaction rate (v0) in a high-dimensional parameter space (pH, T, [S], [E], [cofactor]). | Reaction condition parameters. | A self-driving lab using Bayesian Optimization (tuned via PSO-based simulation) found optimal conditions >10x faster than human-guided search for multiple enzyme pairs. | [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Kinetic Parameter Estimation for Hydrolytic Enzymes Using MOPSO

Objective: To estimate a set of kinetic parameters (e.g., (k{cat}), (Km), inhibition constants) for an enzymatic hydrolysis reaction by minimizing the multi-objective error between a mechanistic model and time-course experimental data for multiple products [18].

Workflow:

- Experimental Data Acquisition:

- Conduct hydrolysis experiments (e.g., of cellulose) under varied conditions: multiple substrate loadings, enzyme loadings, and inhibitor concentrations (e.g., glucose, acid).

- At regular time intervals, sample the reaction mixture and quantify the concentrations of key products (e.g., glucose, cellobiose) via HPLC or colorimetric assay.

- Compile datasets:

[S]_0,[E]_0,[Inhibitor],time→[Product1],[Product2].

Mechanistic Model Formulation:

- Develop a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) based on the reaction scheme (e.g., competitive/uncompetitive inhibition, sequential hydrolysis).

- The model output is the simulated time-course for each product.

MOPSO Optimization Setup:

- Particles: Each particle's position vector represents a candidate set of kinetic parameters.

- Objectives: Define two (or more) objective functions, typically the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between model prediction and experimental data for each primary product (e.g., glucose and cellobiose).

- ( F1(params) = RMSE(Glucose{exp}, Glucose{model}) )

- ( F2(params) = RMSE(Cellobiose{exp}, Cellobiose{model}) )

- Constraints: Impose physiologically plausible bounds on parameters (e.g., all parameters > 0).

Execution & Validation:

- Run the MOPSO algorithm (e.g., a variant with constraint handling) for a sufficient number of iterations.

- The output is a Pareto front of parameter sets, each representing a different optimal trade-off between fitting Product 1 vs. Product 2 data.

- Validate by selecting a central solution from the front and plotting its simulated curves against the experimental data. Perform identifiability analysis (e.g., likelihood profiles) on the parameters.

Diagram 2: MOPSO workflow for kinetic parameter estimation.

Protocol B: Fluorescent Thermal Shift Assay (FTSA) Analysis for Inhibitor-Oligomerization Equilibrium

Objective: To determine the mechanism of action of a drug candidate by globally analyzing FTSA data to fit a model incorporating protein oligomerization equilibria, using PSO for robust parameter estimation [11].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation:

- Purify the target enzyme (e.g., HSD17β13).

- Prepare a master mix of protein, fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange), and buffer.

- Aliquot the master mix into a PCR plate, adding a range of inhibitor concentrations (e.g., 0 to 100 μM), including a DMSO-only control. Perform replicates.

Data Acquisition:

- Run the thermal melt program on a real-time PCR instrument, typically from 25°C to 95°C with a slow ramp rate (e.g., 1°C/min).

- Record fluorescence intensity as a function of temperature for each well.

Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize fluorescence data for each well from 0% (folded) to 100% (unfolded).

- Plot normalized fluorescence vs. temperature to generate melting curves.

PSO-Powered Global Analysis:

- Model Definition: Construct a thermodynamic model describing the equilibrium between monomer (M), dimer (D), tetramer (T), and their ligand-bound states (M:I, D:I, T:I). The model defines the fraction of folded protein as a function of temperature and total inhibitor concentration.

- Parameters: Particle position includes unknown parameters: association constants for oligomerization ((K{dim}, K{tet})), binding constants for inhibitor to each state ((K{I,M}, K{I,D}, K_{I,T})), and enthalpy/entropy changes for unfolding.

- Objective Function: Minimize the sum of squared residuals between all experimental melting curves (across all inhibitor concentrations) and the curves predicted by the model.

- PSO Execution: Execute a PSO algorithm (often hybridized with a local gradient descent) to find the global minimum of the objective function in this high-dimensional parameter space.

Interpretation:

- The best-fit parameters reveal the dominant oligomeric state the inhibitor stabilizes. For example, a high (K_{I,D}) and a model fit showing increased dimer population at low inhibitor concentrations suggests the compound acts by shifting the equilibrium toward the dimeric form.

Protocol C: Multi-Objective Optimization of a Fed-Batch Fermentation Process

Objective: To identify optimal feeding profiles for substrates to maximize product titer and productivity while minimizing raw material cost and by-product formation in an industrial antibiotic (e.g., Balhimycin) fermentation [15].

Workflow:

- Process Model Development:

- Develop a dynamic, mechanistic model of the fed-batch fermentation. This includes mass balance equations for biomass, primary substrate (e.g., glycerol), product, key metabolites, and inhibitors.

- Calibrate the model with initial batch experiment data.

Formulate the Multi-Objective Optimization Problem (MOOP):

- Decision Variables: Discretize the fermentation time into stages. The decision variables are the substrate feeding rate at each stage.

- Objectives: Typically:

- ( F1 ): Maximize final product concentration (g/L).

- ( F2 ): Maximize volumetric productivity (g/L/h).

- ( F3 ): Minimize total substrate consumed (cost).

- (Optional) ( F4 ): Minimize peak concentration of a toxic by-product.

- Constraints: Model differential equations, total batch time, reactor volume limits, and operational bounds on feeding rates.

MOPSO Execution:

- Use an MOPSO variant capable of handling dynamic constraints (e.g., Elitist MODE with Jumping Gene adaptation [15]).

- Each particle represents a full feeding profile. The simulation model is run for each particle to evaluate the objectives.

Analysis of Results:

- The algorithm outputs a Pareto front showing the best possible trade-offs (e.g., high titer vs. low substrate use).

- Select 2-3 promising feeding strategies from different regions of the front.

- Scale-up Validation: Test these selected profiles in lab-scale or pilot-scale fermenters to confirm predicted trade-offs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Resource Guide

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Featured Experiments

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Protocol | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Enzymes / Systems | Cellulase cocktail (for hydrolysis); HSD17β13 (dehydrogenase); Actinoplanes sp. (Balhimycin producer) | Serves as the biocatalyst or producing organism for optimization. | Source, purity, and specific activity must be standardized. |

| Fluorescent Dye | SYPRO Orange, NanoOrange | Binds to hydrophobic patches exposed upon protein unfolding in FTSA (Protocol B). | Dye concentration must be optimized to avoid signal saturation or protein inhibition. |

| Key Substrates & Inhibitors | Microcrystalline cellulose; Glycerol; Synthetic small-molecule inhibitor (e.g., for HSD17β13) | The reactant whose conversion is optimized (Protocol A, C) or the ligand whose binding is characterized (Protocol B). | High purity is critical. Inhibitor stock solutions in DMSO require appropriate vehicle controls. |

| Analytical Standards | Glucose, cellobiose (HPLC grade); Pure Balhimycin standard; Purified protein oligomers (for SEC calibration) | Used to generate calibration curves for accurate quantification of products, substrates, or protein species. | Must be stored appropriately to prevent degradation. |

| Software & Libraries | MATLAB/Simulink, Python (SciPy, DEAP, PySwarms), COPASI | Provides environment for implementing ODE models, MOPSO algorithms, and data analysis. | Choice depends on model complexity and need for pre-built MOPSO modules. |

| Automation Hardware | Liquid handling station (e.g., Opentrons), plate reader, robotic arm | Enables high-throughput data generation for ML-driven optimization (as in [1]) and FTSA setup. | Integration and API compatibility are major development factors. |

Framing enzyme optimization through the lens of Pareto optimality and MOPSO provides a rigorous and practical framework for addressing the inherent complexities of biocatalysis. The transition from single-objective PSO to sophisticated MOPSO variants equips researchers with the ability to not only find solutions but to map the entire landscape of optimal trade-offs between yield, stability, efficiency, and cost. As demonstrated across diverse applications—from atomic-level kinetic parameter fitting to macro-scale bioreactor control—this approach yields actionable insights that single-point optimizations cannot.

The future of this field lies at the intersection of advanced swarm intelligence, machine learning, and laboratory automation. Self-driving laboratories, where MOPSO or hybrid algorithms (like ANN-PSO [19]) autonomously design and execute experiments, promise to accelerate discovery cycles dramatically [1]. Furthermore, integrating digital twins—high-fidelity dynamic process models continuously updated with sensor data—with real-time MOPSO will enable adaptive, closed-loop optimization of industrial bioprocesses. As these technologies mature, the Pareto frontier will become not just a tool for analysis, but a dynamic roadmap for the intelligent and sustainable engineering of enzymatic systems.

In the field of enzyme kinetics and biocatalysis, the systematic evaluation of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)—yield, rate, specificity, and stability—is fundamental for transitioning enzymatic processes from conceptual research to industrial-scale applications. These KPIs do not function in isolation; they often exhibit complex trade-offs, where optimizing one parameter can negatively impact another. This interdependency creates a classic multi-dimensional optimization challenge, particularly relevant in advanced research areas such as the synthesis of high-value compounds like non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) [4].

The broader thesis of this work posits that multi-objective Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) provides a powerful computational framework to navigate this complex landscape. PSO algorithms can efficiently search vast parameter spaces—including enzyme variants, reaction conditions, and pathway fluxes—to identify optimal compromises between competing KPIs. This approach is exemplified in contemporary biocatalytic strategies, such as modular multi-enzyme cascades, where the performance of the entire system hinges on the balanced integration of individual enzymatic steps [4]. By framing enzyme KPIs within an optimization paradigm, researchers and drug development professionals can develop more robust, efficient, and scalable biocatalytic processes, moving beyond single-metric improvements to achieve holistically superior systems.

A Quantitative KPI Framework for Enzyme Kinetic Analysis

A rigorous, quantitative assessment of enzyme performance is essential for informed decision-making in enzyme engineering and process development. The following tables summarize the core KPIs, their definitions, quantitative measures, and benchmark values from contemporary research.

Table 1: Definitions and Quantitative Measures of Core Enzyme KPIs

| KPI | Definition | Key Quantitative Measures | Typical Benchmark (from ncAA Synthesis [4]) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield | The efficiency of substrate conversion to the desired product. | % Conversion, Atomic Economy, Total Product (g/L, mol/L). | Atomic economy >75%; Gram- to decagram-scale production. |

| Rate | The speed of the catalytic reaction. | Turnover Number (kcat, s⁻¹), Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM, M⁻¹s⁻¹), Volumetric Productivity (g/L/h). | 5.6-fold enhanced catalytic efficiency via directed evolution. |

| Specificity | The enzyme's selectivity for target substrate(s) and reaction(s). | Enantiomeric Excess (ee%), Ratio of Activities on different substrates, Product/Byproduct Ratio. | Broad nucleophile scope (C–S, C–Se, C–N bonds); retained stereochemistry. |

| Stability | The retention of catalytic activity over time and under process conditions. | Half-life (t₁/₂), Inactivation Constant (ki), Residual Activity after incubation, Tolerance to [H₂O₂]. | Maintained activity in a 2L cascade system; use of catalase to mitigate H₂O₂ inactivation. |

Table 2: KPI Performance for Key Enzymes in a Modular ncAA Synthesis Cascade [4]

| Enzyme (Module) | Primary Function | Critical KPI & Measured Performance | Impact on Overall Cascade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alditol Oxidase (AldO) (I) | Glycerol → D-glycerate | Rate/Stability: Must operate under [O₂] with H₂O₂ byproduct; requires catalase for stability. | Initial rate dictates total system flux. |

| O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) (III) | OPS + Nucleophile → ncAA | Specificity/Rate: Broad nucleophile scope; kcat/KM enhanced 5.6-fold via directed evolution. | Directly determines product spectrum and final yield. |

| Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK) (II) | ATP regeneration from polyphosphate | Yield/Rate: Drives ATP-dependent steps to completion by overcoming equilibrium. | Enables thermodynamic favorability (ΔG'° < 0). |

| Full Cascade (I-III) | Glycerol → ncAA | Integrated Yield/Stability: >75% atom economy; scalable to 2L with water as sole byproduct. | Demonstrates the synergistic integration of KPI optimization. |

Experimental Protocols for KPI Determination

Protocol: Measuring Catalytic Rate and Specificity Constants

This protocol details the kinetic characterization of an enzyme like O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) to determine kcat and KM, and to assess substrate specificity [4].

- Objective: To determine the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) and substrate specificity profile of a PLP-dependent enzyme.

- Reagents:

- Purified enzyme (e.g., wild-type or evolved OPSS variant).

- Substrate stocks: O-phospho-L-serine (OPS) and a panel of nucleophiles (e.g., allyl mercaptan, potassium thiophenolate, 1,2,4-triazole).

- Assay buffer (e.g., 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, with PLP cofactor).

- Stopping agent (e.g., 1M HCl).

- Analytics (HPLC or LC-MS equipped with a chiral column if needed).

- Procedure:

- Initial Rate Measurements: For a fixed nucleophile, vary the concentration of OPS across a range (e.g., 0.2-5 x KM). Initiate reactions by adding enzyme, quench at multiple time points within the initial linear velocity phase (<10% substrate conversion).

- Specificity Profiling: Repeat Step 1 using a saturating concentration of OPS and varying the concentration of different nucleophilic substrates.

- Product Analysis: Quantify product formation for each time point/substrate condition via HPLC/LC-MS using standard curves.

- Data Analysis: Fit initial velocity data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (or a ping-pong bi-bi model for OPSS) using nonlinear regression software to extract KM and Vmax. Calculate kcat = Vmax / [Enzyme]. Catalytic efficiency = kcat/KM. Compare efficiencies across substrates to define specificity.

Protocol: Assessing Operational Stability in a Multi-Enzyme Cascade

This protocol evaluates the stability of enzymes under operational conditions simulating a modular cascade for ncAA production [4].

- Objective: To determine the operational half-life of key enzymes and identify stability bottlenecks in a multi-enzyme system.

- Reagents:

- Purified cascade enzymes (AldO, G3K, PGDH, PSAT, PPK, OPSS).

- Substrate mix: Glycerol, ATP, polyphosphate, nucleophile, NAD+, L-glutamate, 2-oxoglutarate.

- Stabilizing agents: Catalase (to degrade H₂O₂ from AldO), PLP.

- Assay buffer at optimal pH and temperature.

- Procedure:

- Cascade Assembly: Combine all enzyme modules and substrates in a controlled bioreactor (e.g., 2L working volume). Maintain constant pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen.

- Long-Term Monitoring: Take periodic samples (e.g., every 2-4 hours) over an extended period (24-72 hours).

- Activity Assay: For each sampled time point, measure the residual activity of individual key enzymes (e.g., AldO and OPSS) using the standard kinetic assay (Protocol 3.1) under initial rate conditions.

- Global Metric Tracking: Concurrently track the overall cascade yield (g/L of ncAA) and volumetric productivity over time.

- Data Analysis: Plot residual activity (%) of each enzyme vs. time. Fit the decay curve to a first-order inactivation model to calculate the operational half-life (t₁/₂). Correlate the decline in specific enzyme activities with the drop in overall cascade productivity.

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening for Directed Evolution Based on Multiple KPIs

This protocol outlines a screening strategy for evolving enzymes like OPSS, balancing improvements in rate, specificity, and stability [4].

- Objective: To screen a library of enzyme mutants for variants exhibiting an improved multi-KPI profile.

- Reagents:

- Library of plasmid DNA expressing OPSS mutants.

- Expression host (e.g., E. coli).

- Screening plates (96- or 384-well) containing lyophilized substrates (OPS + target nucleophile).

- Lysis buffer, PLP cofactor.

- Detection reagent: A coupled assay producing a chromophore/fluorophore upon ncAA formation, or a pH indicator for proton-coupled reactions.

- Procedure:

- Expression and Lysis: Grow mutant library in deep-well plates, induce protein expression, and lyse cells.

- Primary Rate Screen: Transfer lysates to assay plates containing substrate. Measure the initial rate of reaction via absorbance/fluorescence change in a plate reader. Select top 5-10% of variants based on initial velocity.

- Secondary Stability Screen: Pre-incubate lysates from primary hits at elevated temperature (e.g., 45°C) for a set time (e.g., 30 min). Measure residual activity under standard conditions. Rank variants by retained activity.

- Tertiary Specificity Validation: For final hits, express and purify proteins. Characterize kinetics against both the target nucleophile and a panel of alternative substrates to confirm improved specificity (ratio of desired/undesired activities).

- Hit Selection: Integrate scores from rate, stability, and specificity screens using a weighted formula to identify Pareto-optimal mutants for further characterization.

Integrating KPIs into a Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization Framework

Particle Swarm Optimization is a computational intelligence technique inspired by social behavior, ideal for navigating high-dimensional search spaces. In enzyme engineering, each "particle" represents a potential solution vector (e.g., a set of reaction conditions, an enzyme variant sequence, or module expression levels). The "swarm" collectively searches for optima by balancing personal best experiences with global best knowledge.

- Solution Encoding: A particle's position is defined by parameters influencing KPIs (e.g., temperature, pH, [cofactor], concentrations of 4-6 enzymes in a cascade).

- Fitness Evaluation: The fitness function is a weighted composite of normalized KPI scores:

Fitness = w_Y * Yield + w_R * Rate + w_S * Specificity + w_T * Stability. Weights are set based on process priorities. - Swarm Dynamics: Particles adjust their velocity (parameter changes) based on: 1) their own historical best performance, and 2) the best performance found by any particle in the swarm, allowing for efficient exploration of trade-offs between KPIs.

- Outcome: The algorithm outputs a Pareto front—a set of non-dominated solutions where no KPI can be improved without worsening another. This provides a clear visualization of the achievable trade-offs for decision-making.

Case Study: KPI-Driven Development of a Modular ncAA Synthesis Cascade

The development of a modular multi-enzyme cascade for synthesizing non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) from glycerol provides a concrete example of KPI-centric design and optimization [4]. The system was explicitly engineered to maximize yield and atom economy while maintaining sufficient rate and stability for scalability.

Workflow Analysis and KPI Integration:

- Module I (Oxidation): The choice of alditol oxidase (AldO) sets the initial rate and impacts stability due to H₂O₂ production. The inclusion of catalase is a direct stability-enhancing intervention.

- Module II (Phosphorylation & Amination): The integration of ATP regeneration via polyphosphate kinase (PPK) is a yield-critical design, driving equilibria toward product and ensuring high overall conversion.

- Module III (Diversification): OPSS is the specificity and rate-determining enzyme. Its directed evolution focused on improving the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for target nucleophiles by 5.6-fold, a direct rate KPI improvement. Its broad substrate scope enables the "plug-and-play" generation of diverse ncAAs, a specificity metric.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Modular ncAA Cascade Assembly

| Reagent / Enzyme | Primary Function in Cascade | Relevance to KPIs |

|---|---|---|

| O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) | Catalyzes C–X (X=S, Se, N) bond formation via α-aminoacrylate intermediate. | Primary driver of Rate & Specificity. Evolved variants show 5.6-fold higher catalytic efficiency [4]. |

| Alditol Oxidase (AldO) | Oxidizes glycerol to D-glycerate, initiating the cascade. | Impacts initial Rate; generates H₂O₂, requiring management for enzyme Stability. |

| Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK) + Polyphosphate | Regenerates ATP from inexpensive polyphosphate. | Critical for Yield, drives ATP-dependent steps to completion economically [4]. |

| Catalase | Degrades H₂O₂ byproduct from AldO to H₂O and O₂. | Essential for operational Stability, protects all enzymes in the cascade from oxidative inactivation. |

| O-phospho-L-serine (OPS) | Intermediate substrate for OPSS; generated in situ from glycerol. | Direct precursor; in situ synthesis from glycerol improves process Yield and atom economy vs. direct addition. |

| Diverse Nucleophiles | Allyl mercaptan, thiophenolate, triazoles, etc. | Define product scope; enzyme Specificity for these is a key performance metric. |

Future Perspectives: Advanced Optimization and System Integration

The future of KPI-driven enzyme kinetics lies in the deeper integration of machine learning with multi-objective optimization and the adoption of more complex biocatalytic systems. Predictive models trained on large datasets of enzyme sequences and kinetic parameters can drastically reduce the search space for PSO, guiding it toward more promising regions of mutation or condition space. Furthermore, the exploration of defined co-cultures [20], where metabolic pathways are distributed between different microbial specialists, presents a new frontier. Here, KPIs like yield and stability must be evaluated at the consortium level, and optimization algorithms must account for inter-species dynamics and physical segregation of pathways, which can circumvent issues like enzyme promiscuity and pathway imbalance [20]. This systems-level approach, powered by advanced multi-objective optimization, will be crucial for developing the next generation of sustainable and economically viable biocatalytic processes.

Methodology in Action: Implementing MOPSO for Enzyme Kinetics and Drug Discovery

Accurate estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters—including the turnover number (kcat), Michaelis constant (Km), and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km)—is a cornerstone of quantitative biology, metabolic engineering, and drug development [21]. These parameters are essential for predicting enzyme behavior in vivo, designing biocatalysts, and understanding metabolic flux distributions. However, their experimental determination remains resource-intensive, creating a significant bottleneck [21]. Computational prediction and optimization frameworks have emerged as powerful alternatives, yet they often tackle single objectives or fail to account for the complex, multi-faceted nature of enzyme performance in realistic biological or industrial settings [22].

This work is situated within a broader thesis that investigates multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) for advancing enzyme kinetics research. Traditional single-objective optimization, which might focus solely on minimizing the error between model predictions and experimental kcat data, can yield parameters that poorly describe Km or vice versa. A multi-objective approach is critical for identifying a Pareto-optimal set of solutions that represent the best possible trade-offs between competing aims, such as simultaneously fitting substrate depletion and product formation time courses, or balancing accuracy in parameter estimation with model robustness [23]. The MOPSO framework developed here provides a robust, global search strategy to navigate the complex, nonlinear parameter spaces common in enzyme kinetic models, moving beyond the limitations of local gradient-based methods which can become trapped in suboptimal solutions [24].

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Comparison

Core Kinetic Parameters and Estimation Challenges

Enzyme kinetics is typically described by the Michaelis-Menten framework, where the reaction velocity (v) depends on the substrate concentration [S] and the parameters Vmax (maximum velocity) and Km. The turnover number kcat is derived from Vmax and the total enzyme concentration. Estimating these parameters from experimental data is an inverse problem that is inherently nonlinear. Challenges include:

- Parameter correlation: Strong interdependence between Vmax and Km can lead to high uncertainty and non-identifiability [23].

- Noisy and multivariate data: Experimental data for metabolic networks are often sparse, noisy, and involve multiple measured variables (e.g., concentrations of various metabolites over time), making calibration difficult [23] [25].

- Non-convex objective landscapes: The error surface between model and data often contains multiple local minima, complicating the search for a global optimum [24].

Multi-Objective Optimization in Kinetic Modeling

A multi-objective formulation is necessary when model calibration must satisfy more than one criterion. For a kinetic model, common objectives include:

- Minimizing the sum of squared errors between predicted and observed substrate concentrations.

- Minimizing the sum of squared errors between predicted and observed product concentrations.

- Minimizing the sum of squared errors for an intermediate metabolite.

- Incorporating a regularization term to penalize unrealistic parameter values and improve identifiability [23].

A solution is considered Pareto-optimal if no objective can be improved without worsening another. The set of all such solutions forms the Pareto front.

Evolution of Optimization Algorithms for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

The field has progressed from traditional linearization methods to sophisticated global and multi-objective optimizers.

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Algorithms for Kinetic Parameter Estimation

| Algorithm Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression (Lineweaver-Burk, etc.) | Linear transformation of Michaelis-Menten equation. | Simple, fast, intuitive. | Prone to error amplification, poor statistical properties, unsuitable for complex models. | Preliminary analysis of simple single-substrate kinetics. |

| Local Nonlinear Regression (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) | Gradient-based search for a local minimum. | Efficient convergence for well-behaved, convex problems. | Requires good initial guesses; prone to converging to local minima; sensitive to noise. | Refining parameters near a known good estimate. |

| Single-Objective Global Heuristics (PSO, GA, SA) | Population-based stochastic search inspired by natural phenomena [24] [25]. | Robust global search; does not require derivatives; less sensitive to initial guesses. | Computationally intensive; single output (may not reveal trade-offs). | Estimating parameters for models with known, single performance metrics. |

| Multi-Objective Global Heuristics (MOPSO, NSGA-II) | Extends heuristic algorithms to maintain and evolve a Pareto front [22] [23] [26]. | Finds optimal trade-offs between competing objectives; reveals parameter sensitivities and correlations. | Higher computational cost; complexity in algorithm tuning and front analysis. | This work's focus: Calibrating complex models against multivariate data, balancing fit quality with robustness. |

Recent studies demonstrate the efficacy of MOPSO. For instance, in modeling the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass, a MOPSO approach reduced the mean squared error for glucose yield prediction by 34% compared to previous methods by effectively handling inhibition kinetics [22]. Similarly, advanced PSO variants like Enhanced Segment PSO (ESe-PSO) have outperformed standard PSO, Genetic Algorithms (GA), and Differential Evolution (DE) in estimating parameters for large-scale E. coli metabolic models [25].

The MOPSO Framework: Design and Workflow

The proposed MOPSO framework integrates principles from global optimization, Bayesian analysis, and systematic experimental design to create a rigorous workflow for kinetic parameter estimation.

The framework follows a sequential, hierarchical structure that progresses from broad global search to refined uncertainty analysis [23].

Core Algorithmic Components

1. Particle Swarm Optimization Fundamentals: Each particle i has a position xi (a vector of kinetic parameters) and a velocity vi in the parameter space. The particles move according to: vi(t+1) = ωvi(t) + c1r1(pbest,i - xi(t)) + c2r2(gbest - xi(t)) xi(t+1) = xi(t) + vi(t+1) where ω is inertia, c1, c2 are acceleration coefficients, r1, r2 are random numbers, pbest,i is the particle's best-found position, and gbest is the swarm's global best position [24] [25].

2. Multi-Objective Extension (MOPSO): The key modification for multiple objectives is the definition of gbest. Instead of a single global best, a non-dominated archive (the Pareto front) is maintained. A leader (gbest) for each particle is selected from this archive, often using techniques like crowding distance to promote diversity along the front [26]. The archive itself is updated at each iteration with newly discovered non-dominated solutions.

3. Enhanced Segment PSO (ESe-PSO) Integration: To improve performance on high-dimensional kinetic parameter problems, we incorporate the ESe-PSO strategy [25]. Particles are dynamically segmented into groups. Each segment searches a specific region of the parameter space, with information shared within and between segments. This, combined with a dynamically decreasing inertia weight (ω), enhances both exploration (global search) and exploitation (local refinement).

Integrated Parameter Estimation Workflow

This detailed workflow shows how the MOPSO algorithm interfaces with the kinetic model and experimental data.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Protocol for Generating Kinetic Data for MOPSO Calibration

Accurate parameter estimation requires high-quality experimental data. This protocol is adapted from optimized design approaches [27].

- Title: Optimized Experimental Design for Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation.

- Objective: To generate time-course substrate and product concentration data that maximizes information content for parameter identifiability.

- Materials:

- Purified enzyme of interest.

- Substrate(s) in a defined buffer system (pH, temperature controlled).

- Stopping reagent (e.g., acid, heat, inhibitor) to quench reactions at precise times.

- Analytical equipment (e.g., HPLC, spectrophotometer, LC-MS/MS [27]).

- Procedure:

- Preliminary Range-Finding: Perform single-timepoint assays across a broad range of substrate concentrations (e.g., 0.1Km to 10Km, estimated from literature) to determine an appropriate time window where ≤20% of substrate is consumed (initial rate conditions).

- Optimal Design Experiment: Instead of standard Michaelis-Menten plots, use an optimal design approach (ODA) [27]. Set up reactions at 3-5 strategically chosen substrate concentrations (spanning the range, with more points near the expected Km). For each concentration, prepare multiple reaction tubes.

- Time-Course Sampling: Initiate all reactions simultaneously. Quench individual tubes from each concentration at multiple, optimally spaced time points (e.g., 5-7 time points per concentration) [27]. This yields a rich dataset of [S] and [P] over time across different initial conditions.

- Analysis: Quantify substrate depletion and/or product formation for all samples.

- Data for MOPSO: The dataset for MOPSO input is a matrix of time points, initial substrate concentrations, and the corresponding measured product/substrate concentrations.

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Design Methods for Kinetic Data Generation

| Design Method | Description | Information Efficiency | Suitability for MOPSO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Initial Rates | Measures initial velocity (v) at various [S]. Simple but requires many independent reactions under strict initial rate conditions. | Low. Prone to error from single-timepoint measurements. | Poor. Only provides v vs. [S] data, not time courses needed for dynamic model fitting. |