Optimizing Biomedical Experiments: A Practical Guide to the Fisher Information Matrix for Efficient Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) and its pivotal role in optimal experimental design (OED) for biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Optimizing Biomedical Experiments: A Practical Guide to the Fisher Information Matrix for Efficient Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) and its pivotal role in optimal experimental design (OED) for biomedical and pharmaceutical research. We first establish the foundational link between the FIM and the precision of parameter estimation via the Cramér-Rao bound, explaining its critical function in model-based design[citation:2][citation:4]. We then explore methodological advancements, including optimization-free, ranking-based approaches for online design and the implementation of population FIMs for nonlinear mixed-effects models prevalent in pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD)[citation:1][citation:3]. A dedicated troubleshooting section analyzes the impact of key approximations (FO vs. FOCE) and matrix implementations (Full vs. Block-Diagonal FIM) on design robustness, especially under parameter uncertainty[citation:2]. Finally, we compare validation strategies, from asymptotic FIM evaluations to robust simulation-based methods, offering a clear framework for researchers and drug development professionals to design more informative, cost-effective, and reliable studies.

The Core of Precision: Demystifying the Fisher Information Matrix and the Cramér-Rao Bound

Technical Support Center: FIM Troubleshooting & FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists applying Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) concepts within optimal experimental design (OED), particularly in drug development. The FIM quantifies the amount of information a sample provides about unknown parameters of a model, guiding the design of efficient and informative experiments [1] [2]. Below are common technical issues, troubleshooting guides, and detailed protocols to support your work.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM), and why is it critical for my experimental design? The FIM is a mathematical measure of the information an observable random variable carries about unknown parameters of its underlying probability distribution [2]. In optimal design, you aim to choose controllable variables (e.g., sample times, dose amounts) to maximize the FIM. This is equivalent to minimizing the lower bound on the variance of your parameter estimates, as defined by the Cramér-Rao Bound (CRB) [3]. A larger FIM indicates your experiment will yield more precise parameter estimates, leading to more robust conclusions from costly clinical or preclinical trials [4].

Q2: My model parameters are highly correlated, leading to a near-singular FIM. What should I do? A near-singular FIM indicates poor parameter identifiability—your data cannot reliably distinguish between different parameter values. This is reflected in large off-diagonal elements in the FIM or its inverse [3].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Simplify the Model: Re-evaluate if all parameters are necessary. Fix well-known parameters to literature values if possible.

- Re-design the Experiment: Use FIM-based optimal design before running the experiment. Optimize sampling times or dose levels to reduce correlation. The D-optimality criterion is specifically designed to minimize the overall variance of parameter estimates by maximizing the determinant of the FIM.

- Include Prior Information: If using a Bayesian framework, consider using the prior distribution to regularize the problem. The FIM forms the basis of non-informative priors in Jeffreys' rule [2].

Q3: How do I calculate the FIM for a nonlinear mixed-effects (NLME) model commonly used in pharmacometrics? For NLME models, the marginal likelihood requires integrating over random effects, making exact FIM calculation difficult.

- Standard Protocol: The First Order (FO) approximation is widely used. This method linearizes the model around the expected values of the random effects (typically zero), allowing for an approximate, closed-form calculation of the expected FIM for the population-level parameters [3].

- Important Note: The FO approximation is an estimation. Always validate your final optimal design using stochastic simulation and re-estimation (SSE) to confirm that parameter precision targets are met in practice [3].

Q4: In dose-response studies, how can FIM-based design improve Phase II/III dose selection? Traditional pairwise dose comparisons are limited and contribute to high late-stage attrition [4]. FIM-based OED shifts the paradigm to an estimation problem.

- Application: You design a study to precisely estimate the parameters of a dose-exposure-response (DER) model (e.g., an Emax model). By maximizing the FIM for parameters like Emax (maximum effect) and ED50 (potency), you optimally select dose levels and patient allocation to learn the full dose-response curve. This provides a scientific rationale for selecting the optimal dose for confirmatory trials, rather than just a statistically significant one [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Precision in Key Parameter Estimates

- Symptom: After analysis, the confidence intervals for critical parameters (e.g., drug clearance, IC50) are unacceptably wide.

- Diagnosis: The experimental design provided insufficient information for those parameters.

- Solution:

- Pre-Design FIM Evaluation: Before conducting the experiment, compute the expected FIM for your proposed design (sampling schedule, doses, sample sizes) [3].

- Apply an Optimality Criterion: Use a criterion like A-optimality (minimizing the trace of FIM inverse) to improve the average precision of your specific parameters of interest.

- Iterate: Use software tools to optimize your design variables (e.g., times, doses) to maximize your chosen criterion. The table below compares common criteria.

Table 1: Common Optimality Criteria for Experimental Design

| Criterion | Objective | Best Used For | Mathematical Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-Optimality | Maximizes overall precision; minimizes joint confidence ellipsoid volume. | General purpose design; model discrimination. | Maximize det(FIM) |

| A-Optimality | Maximizes average precision of individual parameter estimates. | Focusing on a specific set of parameters. | Minimize trace(FIM⁻¹) |

| C-Optimality | Minimizes variance of a linear combination of parameters (e.g., predicted response). | Precise prediction at a specific point (e.g., target dose). | Minimize cᵀFIM⁻¹c |

Issue: Failed Model Convergence or Estimability During Analysis

- Symptom: Software fails to converge or reports "estimability" errors when fitting the model to the collected data.

- Diagnosis: The collected data is information-poor for the chosen model, often due to a suboptimal design. This is a direct consequence of a low FIM.

- Solution:

- Simulate and Verify: Prior to the physical experiment, simulate virtual datasets from your proposed optimal design and your model. Attempt to re-estimate parameters from these datasets.

- Assess Success Rate: If the estimation fails or is biased in >20% of simulations, the design is inadequate despite theoretical FIM optimality [3].

- Re-optimize with Constraints: Add practical constraints (e.g., minimum time between samples, feasible dose levels) and re-optimize the design. A multi-objective framework can balance information with cost and practicality [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: FIM-Based Optimal Design for a Dose-Response Study

This protocol outlines steps to design a dose-finding study using an Emax model.

1. Define the Model and Parameters:

- Model: ( E = E0 + \frac{E{max} \cdot D}{ED_{50} + D} )

- Parameters to Estimate: ( E0 ) (baseline effect), ( E{max} ) (maximum drug effect), ( ED{50} ) (dose producing 50% of ( E{max} )) [4].

- Parameter Uncertainty: Specify initial/prior estimates and their uncertainty (e.g., coefficient of variation).

2. Specify Design Variables and Constraints:

- Variables: Dose levels (D), number of subjects per dose (N), sampling times for response measurement.

- Constraints: Total number of subjects, minimum/maximum safe dose, clinical sampling limitations.

3. Compute and Optimize the Expected FIM:

- Using optimal design software (e.g., Pumas, PopED), calculate the expected FIM for a candidate design [3].

- Select an optimality criterion (see Table 1). For dose-response, D-optimality is often used to precisely estimate all parameters of the curve.

- Run an optimization algorithm to adjust design variables to maximize the criterion.

4. Validate Design via Simulation:

- Simulate 500-1000 virtual trials using the optimal design.

- Fit the Emax model to each simulated dataset.

- Calculate the relative root mean square error (RRMSE) for each parameter: ( \text{RRMSE} = \sqrt{\text{MSE}} / \text{True Value} ). A successful design should have RRMSE < 0.3 for key parameters.

Table 2: Example Dose-Response Parameters and Target Precision

| Parameter | Symbol | Initial Estimate | Target RRMSE | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Effect | ( E_0 ) | 10 units | < 0.15 | Disease severity without treatment. |

| Maximum Effect | ( E_{max} ) | 50 units | < 0.25 | Maximal achievable drug benefit. |

| Potency | ( ED_{50} ) | 5 mg | < 0.30 | Indicator of drug strength; key for dose selection. |

5. Implement and Adapt:

- Run the study according to the optimized design.

- For adaptive trials, interim data can be used to update parameter estimates and re-optimize the design for remaining subjects [4].

Protocol 2: Diagnosing & Solving Parameter Non-Identifiability

Symptoms: Extremely large standard errors, failure of estimation algorithm, strong pairwise parameter correlations (>0.95) in the correlation matrix (derived from FIM⁻¹).

Diagnostic Steps:

- Compute the FIM and its Eigenvalues: A singular FIM will have one or more eigenvalues near zero. The corresponding eigenvectors indicate which linear combinations of parameters are not informed by the data.

- Profile Likelihood Analysis: For each parameter, fix it at a range of values and optimize over all others. A flat profile likelihood indicates the data does not contain information about that parameter.

Remedial Actions:

- Design Enhancement: Add informative data points (e.g., a new sampling time, an additional dose level) targeted at the weak directions identified by the FIM eigenanalysis.

- Parameter Reduction: If two parameters are perfectly correlated (e.g., volume and clearance in a simple PK model), consider if they can be combined into a single composite parameter (e.g., half-life).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for FIM-Based Optimal Experimental Design

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Example/Function | Role in FIM/OED Research |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Design Software | Pumas (Julia), PopED (R), PFIM (standalone) | Platforms to compute expected FIM for nonlinear models, optimize designs, and perform validation simulations [3]. |

| Pharmacometric Modeling Software | NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix NLME | Industry-standard tools for building NLME models. The final model structure is the foundation for FIM calculation. |

| Statistical Computing Environment | R, Python (SciPy), Julia | Essential for custom scripting, advanced statistical analysis, and implementing bespoke optimality criteria or visualizations. |

| Clinical Trial Simulation Framework | Clinical trial simulation (CTS) suites [4] | Used to validate optimal designs under realistic, stochastic conditions beyond the FIM approximation. |

| Reference Models & Parameters | Published PK/PD models (e.g., Emax, indirect response) | Provide initial parameter estimates and uncertainty required to compute the expected FIM before any new data is collected [4]. |

Visual Guides: Workflows and Relationships

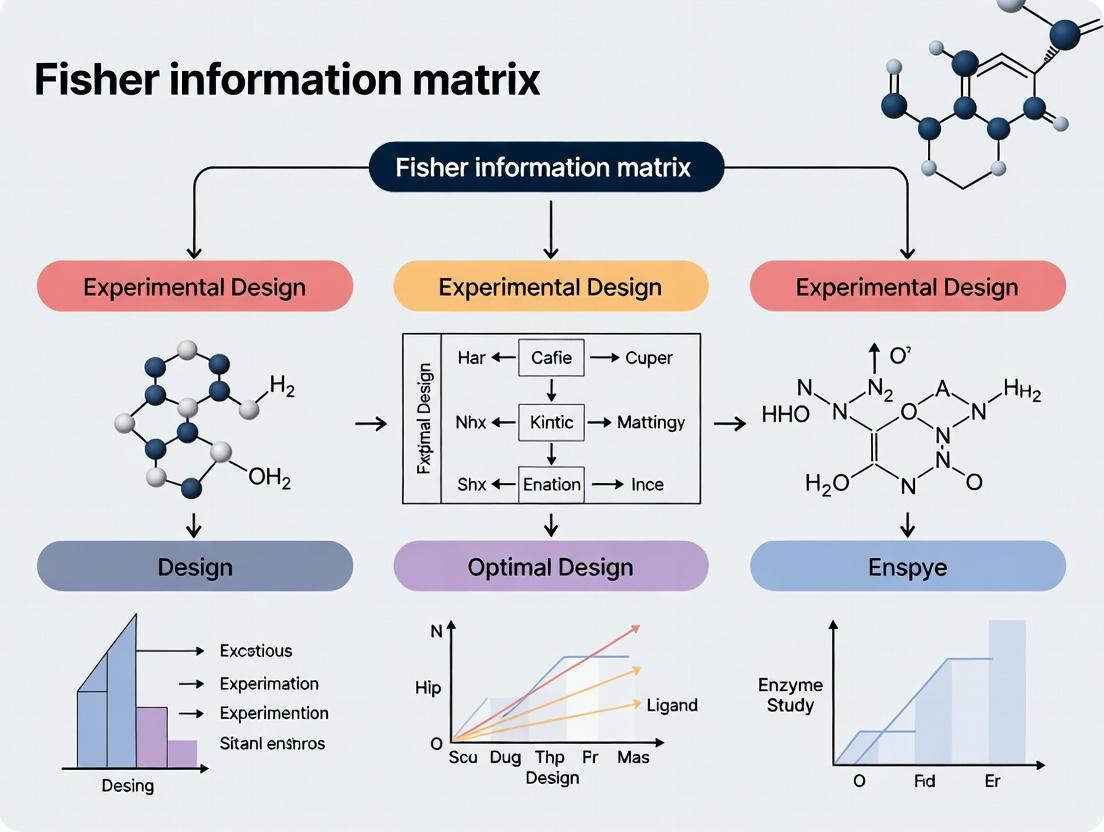

Diagram 1: FIM-Based Optimal Design Cycle (85 characters)

Diagram 2: Integrating PK/PD Models with FIM (74 characters)

In the context of optimal experimental design, a core objective is to configure experiments that yield the most precise estimates of model parameters, such as kinetic constants or drug potency. The Cramer-Rao Bound (CRB) provides the theoretical foundation for this pursuit. It states a fundamental limit: for any unbiased estimator of a parameter vector (\boldsymbol{\theta}), its covariance matrix cannot be smaller than the inverse of the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) [6] [7]. Formally:

[ \operatorname{Cov}(\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}) \succeq I(\boldsymbol{\theta})^{-1} ]

where (I(\boldsymbol{\theta})) is the FIM and (\succeq) denotes that the difference is a positive semi-definite matrix [6]. The FIM quantifies the amount of information an observable random variable carries about the unknown parameters [2]. Therefore, in experiment design, we aim to maximize the FIM (according to a chosen optimality criterion like D-optimality) to push the achievable variance of our estimators toward this theoretical lower bound, ensuring maximal precision [8].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting FIM & CRB Applications

FAQ 1: What is the practical interpretation of the Cramér-Rao Bound for my experiment?

The CRB is not just a theoretical limit; it is a direct benchmark for your experimental design's potential efficiency. If you calculate the FIM for your proposed experimental protocol (e.g., sampling times, dosages), its inverse provides a lower bound on the covariance matrix for your parameter estimates. By comparing the actual performance of your estimator against this bound, you can assess how much room for improvement exists. An estimator that attains the bound is called efficient [6] [9]. In pharmacometrics, optimizing designs to maximize the FIM (minimize the bound) is a standard method to reduce required sample sizes and costs [8].

FAQ 2: My optimal design is producing highly clustered sampling points. Is this a problem, and how can I address it?

Issue: Clustering of sampling times or conditions is a common outcome of D-optimal design, where samples are placed at theoretically information-rich points [8]. Troubleshooting: While clustering is optimal for a perfectly specified model, it reduces robustness. If the model structure or prior parameter values are misspecified, clustered designs can perform poorly [8]. Solutions:

- Use a more accurate FIM approximation: Research shows that using the First-Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE) approximation instead of the simpler First-Order (FO) method, along with a full FIM calculation (not block-diagonal), tends to generate designs with more support points and less clustering, enhancing robustness to parameter misspecification [8].

- Implement a robust design criterion: Consider criteria like ED-optimality that account for parameter uncertainty explicitly.

- Apply practical constraints: Enforce minimum time intervals between samples in the optimization algorithm to ensure feasibility and robustness.

FAQ 3: Why do my parameter estimates have higher variance than the CRB predicted? What are the common causes?

The CRB assumes the estimator is unbiased and that the model is correct. Discrepancies arise from:

- Model Misspecification: The CRB is derived for the true underlying model. An incorrect model structure invalidates the bound [8].

- Parameter Misspecification in Design: Using incorrect prior parameter values to compute the FIM during the design phase leads to a suboptimal design that collects less information than predicted [8].

- Violation of Regularity Conditions: The CRB derivation requires conditions like the ability to interchange integration and differentiation [6] [10]. Distributions with parameter-dependent supports (e.g., Uniform(0, θ)) violate these [2].

- Finite Sample Effects: Maximum Likelihood Estimators (MLE) are asymptotically efficient, but for small samples, they may not achieve the bound [9] [7].

- Use of Approximated FIM: In complex nonlinear mixed-effects models (common in drug development), the exact FIM is intractable. Using FO or FOCE approximations introduces error into the bound itself [8].

FAQ 4: The optimization for my model-based design of experiments (MBDoE) is computationally expensive or gets stuck in local optima. Are there alternatives?

Issue: Traditional MBDoE solves a (often non-convex) optimization problem to maximize a function of the FIM, which is computationally intensive and sensitive to initial guesses [11]. Solution: An Optimization-Free FIM-Driven (FIMD) Approach. This emerging methodology [11]:

- Generates a large candidate set of possible experimental conditions.

- For each candidate experiment, computes the FIM based on current parameter estimates.

- Ranks the experiments by an information-theoretic criterion (e.g., D-optimality value).

- Selects the top-ranked experiment for the next run. This iterative, ranking-based approach avoids expensive nonlinear optimization, significantly reduces computation time, and is less prone to local optima, making it suitable for online/autonomous experimental platforms [11].

FAQ 5: When should I use the full FIM versus the block-diagonal FIM in pharmacometric design?

This choice significantly impacts your optimal design [8].

Block-Diagonal FIM: Assumes that the fixed effects parameters ((\beta)) and the variance-covariance parameters ((\lambda)) are independent. It simplifies and speeds up computation [8]. Full FIM: Accounts for the covariance between fixed effects and variance parameters. It is more accurate but computationally heavier [8].

Recommendation: The literature indicates that for design optimization, using the full FIM (especially with the FOCE approximation) generally yields designs that are more robust to parameter misspecification [8]. Use the block-diagonal approximation primarily for initial scoping or when computational resources are severely constrained, acknowledging the potential for increased bias in the resulting designs [8].

Table 1: Comparison of FIM Approximation and Implementation Methods in Pharmacometrics [8]

| Method | Description | Computational Cost | Design Characteristic | Robustness to Misspecification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FO Approximation | Linearizes around random effect mean of 0. | Lower | Tends to create designs with clustered support points. | Lower; FO block-diagonal designs showed higher bias. |

| FOCE Approximation | Linearizes around conditional estimates of random effects. | Higher | Creates designs with more support points, less clustering. | Higher. |

| Block-Diagonal FIM | Ignores covariances between fixed & variance parameters. | Lower | Can be less informative. | Generally lower than Full FIM. |

| Full FIM | Includes all parameter covariances. | Higher | More informative support points. | Superior, particularly when combined with FOCE. |

Featured Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: D-Optimal Design for a Pharmacokinetic (PK) Model

This protocol is based on a study optimizing sampling schedules for Warfarin PK analysis [8].

1. Objective: Determine optimal sampling times to minimize the uncertainty (maximize the D-optimality criterion) of PK parameter estimates (e.g., clearance CL, volume V).

2. Pre-experimental Setup:

- Define Model: Use a nonlinear mixed-effects model (e.g., one-compartment, first-order absorption and elimination).

- Specify Parameters: Provide initial (prior) estimates for fixed effects (

CL,V,ka), between-subject variability (BSV), and residual error. - Define Design Space: Specify constraints (e.g., sampling window: 0-72 hours, maximum 10 samples per subject).

3. FIM Calculation & Optimization:

- Select FIM Method: Choose an approximation (FO or FOCE) and implementation (Full or Block-diagonal). For robustness, FOCE with Full FIM is recommended [8].

- Compute FIM: For a given sampling schedule (\xi), calculate the FIM (I(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \xi)) using the chosen method. Software:

PopED,PFIM, orPhoenix. - Optimize: Use an algorithm (e.g., stochastic gradient, exchange) to find the schedule (\xi^*) that maximizes (\log(\det(I(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \xi)))) (D-optimality).

4. Validation via Simulation & Estimation (SSE):

- Simulate 500-1000 datasets using the optimal design (\xi^) and the *true parameter values.

- Estimate parameters from each simulated dataset.

- Calculate the empirical covariance matrix and the empirical D-criterion. Compare this to the predicted FIM-based D-criterion to evaluate performance [8].

Protocol B: Optimization-Free FIMD for Kinetic Model Identification

This protocol implements the FIMD approach for a fed-batch yeast fermentation reactor [11].

1. Objective: Sequentially select the most informative experiment to rapidly reduce uncertainty on kinetic model parameters.

2. Iterative Loop:

- Step 1 - Candidate Generation: At iteration (k), using current parameter estimates (\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_k), generate a large set (S) of candidate experimental conditions (e.g., varying substrate feed rate, temperature).

- Step 2 - FIM Ranking: For each candidate (s \in S), compute the FIM (I(\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_k, s)). Calculate its determinant (D-value).

- Step 3 - Experiment Selection: Choose and run the experiment (s^*) with the highest D-value.

- Step 4 - Parameter Update: Incorporate new data from (s^*), re-estimate parameters to obtain (\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{k+1}).

- Step 5 - Convergence Check: Stop when parameter confidence intervals are sufficiently small or a set number of iterations is reached.

3. Key Advantage: This method avoids the nonlinear optimization of traditional MBDoE by leveraging ranking, leading to faster convergence and lower computational cost for online applications [11].

Table 2: Key Resources for FIM-based Optimal Experimental Design

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Solution | Function & Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Platforms | PopED (R), PFIM, Phoenix NLME, MONOLIX |

Industry-standard platforms for computing FIM and optimizing experimental designs for pharmacometric and biological models. |

| Computational Algorithms | First-Order (FO) & First-Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE) linearization [8] | Algorithms to approximate the FIM for nonlinear mixed-effects models where the exact likelihood is intractable. |

| Statistical Criteria | D-optimality, ED-optimality | Scalar functions of the FIM used as objectives for optimization. D-opt maximizes the determinant of FIM; ED-opt maximizes the expected determinant over parameter uncertainty. |

| Theoretical Benchmarks | Cramér-Rao Bound (Scalar & Multivariate) [6], Bayesian Cramér-Rao Bound [9] | Fundamental limits for unbiased and Bayesian estimators, used to benchmark the efficiency of any estimation procedure. |

| Emerging Methodologies | Fisher Information Matrix Driven (FIMD) approach [11] | An optimization-free, ranking-based method for sequential experimental design, ideal for autonomous experimentation. |

Core Conceptual and Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Logical Pathway from Experiment to Estimation Limit

Diagram 2: Workflow for Model-Based Optimal Design (MBDoE)

The Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) serves as the foundational mathematical bridge connecting a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model to the efficiency of an experimental design. In drug development, where studies are costly and subject numbers are limited, optimizing the design through the FIM is critical for obtaining precise parameter estimates with minimal resources [12]. The core principle is encapsulated in the Cramér-Rao inequality, which states that the inverse of the FIM provides a lower bound for the variance-covariance matrix of any unbiased parameter estimator [13] [8]. Therefore, by maximizing the FIM, we minimize the expected uncertainty in our parameter estimates.

This optimization is not performed on the matrix directly but via specific scalar functions known as optimality criteria. The most common is D-optimality, which seeks to maximize the determinant of the FIM, thereby minimizing the volume of the confidence ellipsoid around the parameter estimates [13] [12]. Other criteria, such as lnD- and ELD- (Expected lnD) optimality, provide nuanced approaches for local (point parameter estimates) and robust (parameter distributions) design optimization, respectively [13]. This technical support center addresses the practical challenges researchers encounter when implementing these theoretical concepts, from selecting approximations to validating designs in the context of a Model-Based Adaptive Optimal Design (MBAOD) framework [13].

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

This section provides targeted solutions for common computational, methodological, and interpretive challenges in FIM-based optimal design.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common FIM Implementation Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Probable Cause | Corrective Action & Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Misspecification | Design performs poorly when implemented; high bias or imprecision in parameter estimates from study data. | Prior parameter values (θ) used for FIM calculation are inaccurate [13]. | Implement a Model-Based Adaptive Optimal Design (MBAOD). Use a robust criterion like ELD-optimality, which integrates over a prior parameter distribution [13]. Validate with a pilot study. |

| FIM Approximation Error | Significant discrepancy between predicted parameter precision (from FIM inverse) and empirical precision from simulation/estimation [8]. | Use of an inappropriate linearization method (e.g., First-Order (FO) vs. First-Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE)) for the model's nonlinearity [8]. | For highly nonlinear models or large inter-individual variability, switch from FO to FOCE approximation [8]. Compare the empirical D-criterion from simulated datasets against the predicted value. |

| Suboptimal Sampling Clustering | Optimal algorithm yields only 1-2 unique sampling times, creating risk if model assumptions are wrong. | D-optimality for rich designs often clusters samples at information-rich support points [8]. | Use the Full FIM implementation instead of the block-diagonal FIM during optimization, which tends to produce designs with more support points [8]. |

| Unrealistic Power Prediction | FIM-predicted power to detect a covariate effect is overly optimistic compared to simulation. | FIM calculation did not properly account for the full distribution (discrete/continuous) of covariates [14]. | Extend FIM calculation by computing its expectation over the joint covariate distribution. Use simulation of covariate vectors or copula-based methods [14]. |

| Failed Design Optimization | Optimization routine fails to converge or returns an invalid design. | Numerical instability in FIM calculation; ill-conditioned matrix; inappropriate design space constraints. | Simplify model if possible; check conditioning of FIM; use logarithmic parameterization; verify and broaden design variable boundaries. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the practical difference between D- and lnD-optimality? A1: Mathematically, D-optimality maximizes det(FIM), while lnD-optimality maximizes ln(det(FIM)). They yield the same optimal design because the logarithm is a monotonic function. The lnD form is often preferred for numerical stability, as it avoids computing extremely large or small determinants [13].

Q2: When should I use a robust optimality criterion like ELD instead of local D-optimality? A2: Use a local criterion (D-/lnD-optimality) only when you have high confidence in your prior parameter estimates. If parameters are uncertain (specified as a distribution), a robust criterion (ELD-optimality) that maximizes the expected information over that distribution is superior. Evidence shows MBAODs using ELD converge faster to the true optimal design when initial parameters are misspecified [13].

Q3: How do I choose between FO and FOCE approximations for my model? A3: The First-Order (FO) approximation is faster and sufficient for mildly nonlinear models with small inter-individual variability. The First-Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE) approximation is more accurate for highly nonlinear models or models with large variability but is computationally heavier [8]. Start with FO, but if predicted standard errors seem unrealistic, validate with a small set of FOCE-based optimizations.

Q4: What software tools are available for FIM-based optimal design?

A4: Several specialized tools exist: PFIM (for population FIM), PopED, POPT, and PkStaMP [8]. The MBAOD R-package is designed specifically for adaptive optimal design [13]. The recent work on covariate power analysis has been implemented in a development version of the R package PFIM [14].

Q5: How can I validate an optimal design before running the actual study? A5: Always perform a stochastic simulation and estimation (SSE) study. 1) Simulate hundreds of datasets under your optimal design and true model. 2) Estimate parameters from each dataset. 3) Calculate empirical bias, precision, and coverage. Compare the empirical covariance matrix to the inverse of the FIM used for design [8]. This is the gold standard for performance evaluation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Model-Based Adaptive Optimal Design (MBAOD) Study

This protocol outlines the iterative "learn-and-confirm" process for dose optimization, as described in [13].

1. Pre-Study Setup:

- Define PK/PD Model: Specify the structural (e.g., one-compartment PK with sigmoidal Emax PD) and statistical (random effects, residual error) models.

- Set Prior Information: Define initial population parameter estimates (β, ω, σ). Acknowledge potential misspecification (e.g., PD parameters may be 50% overestimated).

- Choose Optimality Criterion: Select lnD-optimality (local) or ELD-optimality (robust) based on parameter certainty.

- Define Stopping Rule: Establish a quantitative endpoint. Example: Stop when the 95% CI for the population mean effect prediction is within 60–140% for all doses and sampling times [13].

- Cohort Design: Determine initial cohort size (e.g., 8 subjects in 2 dose groups) and adaptive cohort size (e.g., +2 subjects per iteration).

2. Iterative MBAOD Loop:

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center provides targeted solutions for common challenges encountered when implementing Fisher Information Matrix (FIM)-based optimal experimental design (OED) in Nonlinear Mixed-Effects (NLME) frameworks. The guidance is framed within a broader thesis on advancing OED to improve the precision and efficiency of pharmacological research and drug development.

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: Singular or Ill-Conditioned Fisher Information Matrix (FIM)

- Symptoms: Software errors stating the FIM is "non-invertible" or "singular"; extremely large or unreliable parameter standard errors from estimation routines; failure of OED optimization algorithms to converge [15].

- Diagnosis: This indicates a practical or structural identifiability problem. Parameters may be unidentifiable due to insufficient data, poor experimental design, or redundant parameterization within the complex NLME model structure [16] [15].

- Solutions:

- Parameter Subset Selection (Leave Out Approach): Systematically identify and fix a subset of problematic parameters to their prior estimates. This reduces the dimensionality of the estimation problem, resulting in a well-conditioned, reduced FIM for designing experiments. Research shows this approach leads to superior designs compared to using a pseudoinverse [15].

- Reparameterize or Simplify the Model: Use prior knowledge or initial exploratory analysis (e.g., profile likelihood) to combine or fix parameters that are highly correlated or cannot be independently informed by the available measurements [16].

- Employ a Sequential Design: Use a two-stage approach. An initial "learning" stage with a safe, conservative design (e.g., a bolus injection) provides data to obtain preliminary parameter estimates. These estimates are then used to compute a stable FIM for optimizing the design of a subsequent "optimization" stage [17].

Issue 2: Poor Practical Identifiability and High Parameter Uncertainty

- Symptoms: Wide confidence intervals for population or individual parameter estimates; parameter estimates that vary significantly with different starting values; inability to distinguish between competing biological hypotheses [16].

- Diagnosis: The experimental design provides insufficient information to precisely estimate all parameters, even if they are structurally identifiable. This is common in NLME models with high inter-individual variability and sparse sampling [16].

- Solutions:

- Adopt a Multi-Start Estimation Approach: Run the parameter estimation algorithm from multiple diverse starting points. Convergence to a single optimum indicates identifiability, while convergence to distinct optima indicates unidentifiability and the need for a better design [16].

- Apply Optimal Design Criteria: Redesign the experiment using FIM-based criteria. Use the initial, uncertain parameter estimates to compute the FIM and optimize the design (e.g., sampling times, dose levels) to maximize a scalar criterion like D-optimality (maximizing determinant) or A-optimality (minimizing trace of the inverse) [17] [18].

- Incorporate Prior Information: Formally use Bayesian optimal design or use the expected FIM integrated over a prior distribution of the parameters. This acknowledges uncertainty upfront and designs experiments that are robust across plausible parameter values [17] [3].

Issue 3: Suboptimal Performance of "Optimal" Designs in Practice

- Symptoms: An experiment designed using OED software yields parameter estimates with higher-than-predicted uncertainty; the optimized design seems impractical or violates clinical constraints.

- Diagnosis: The local approximation (e.g., first-order linearization) used to compute the FIM for the complex NLME model may be inaccurate. The design is only optimal for the specific parameter values used during the design phase [3] [19].

- Solutions:

- Validate with Stochastic Simulation and Estimation (SSE): Before running the costly experiment, simulate hundreds of virtual datasets using the proposed design and the NLME model. Re-estimate parameters from each dataset. The empirical distribution of the estimates will reveal the true, not approximated, expected performance of the design [3].

- Enforce Real-World Constraints Explicitly: Frame the OED problem as a constrained optimization. Include hard limits on total dosage, maximum instantaneous infusion rates, clinically feasible sampling times, and patient/animal safety boundaries directly in the optimization algorithm [17].

- Use More Accurate FIM Approximations: Explore software tools that use more sophisticated methods than first-order linearization to approximate the FIM, such as Monte Carlo sampling to compute the mean response and its covariance matrix [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental link between the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) and the quality of my parameter estimates in an NLME model? A1: The FIM quantifies the amount of information your experimental data provides about the unknown model parameters. According to the Cramér-Rao lower bound, the inverse of the FIM provides a lower bound for the covariance matrix of any unbiased parameter estimator [3]. Therefore, a "larger" FIM (as measured by optimality criteria) translates to a theoretical minimum for parameter uncertainty that is smaller, meaning your estimates can be more precise.

Q2: I understand D-optimality minimizes the generalized variance, but what do A-optimal and V-optimal designs target? A2: Different optimality criteria minimize different aspects of uncertainty:

- A-Optimality: Minimizes the average variance of the parameter estimates (trace of the inverse FIM). It is ideal when you want all parameters to be estimated with good, balanced precision [17] [18].

- V-Optimality: Minimizes the average prediction variance over a set of important experimental conditions. It is used when the primary goal is to make the most accurate future predictions from the model, rather than just estimating parameters [15].

- D-Optimality: Minimizes the volume of the joint confidence ellipsoid for the parameters (determinant of the inverse FIM). It is the most common criterion for improving overall parameter identifiability [18].

Q3: How do I choose initial parameter values for OED when studying a new compound with high inter-subject variability? A3: When prior information is very limited, implement a two-stage sequential design. The first stage uses a simple, safe design (like a moderate bolus) to collect preliminary data from the population. These data are used to obtain initial estimates (a "prior distribution") for the parameters. The FIM is then calculated based on this prior to design an optimized second-stage experiment (e.g., a complex infusion schedule) tailored to reduce the remaining uncertainty [17].

Q4: Can modern AI/ML methods be integrated with FIM-based OED in NLME frameworks? A4: Yes, hybrid approaches are emerging. For instance, AI can be used to model complex, non-specific response patterns (e.g., placebo effect) from historical data. The predictions from the AI model (e.g., an Artificial Neural Network) can then be integrated as covariates or into the error structure of an NLME model. The FIM for this combined "AI-NLME" model is then used for OED, leading to trials with enhanced signal detection for the true drug effect [20]. This represents a cutting-edge extension of traditional FIM methodology.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Optimal Design for Pharmacokinetic (PK) Parameter Estimation

- Objective: Precisely estimate individual-specific PK parameters (e.g., clearance, volume of distribution) with minimal data points, subject to safety constraints [17].

- Methodology:

- Learning Stage: Administer a standard, safe bolus injection. Take 4-6 strategic blood samples over the compound's anticipated half-life. Fit an NLME PK model to obtain individual empirical Bayes estimates and their population distribution.

- FIM Computation: Using the individual estimates from Step 1 as the prior

θ, compute the expected FIM for a candidate designd(a vector of future sample times and infusion rates). For a linear(ized) model, the FIM entry(i,j)is a quadratic formI_θ(i,j) = u_agg^T * M_θ(i,j) * u_agg, whereu_aggincludes the input design [17]. - Optimization Stage: Solve a constrained optimization problem:

max_d [ log(det(FIM(θ, d))) ](for D-optimality). Constraints include maximum/minimum infusion rate, total dose, and time horizon. The output is an optimized infusion schedule and sampling plan. - Validation: Perform Stochastic Simulation and Estimation (SSE) with the optimized design to confirm performance.

Protocol 2: D-Optimal Design for Signaling Pathway Model Calibration

- Objective: Identify an optimal dynamic input (e.g., cytokine concentration) profile to minimize parameter uncertainty in a systems biology ODE model [18].

- Methodology:

- Sensitivity Analysis: For the nonlinear ODE model

dx/dt = f(x,u,p), compute local sensitivity coefficientsS_ij = ∂y_i/∂p_jfor all measured outputsyand parameterspat numerous time points. - FIM Construction: Assemble the sensitivity matrix

S. The FIM is approximated byF = S^T * S[18]. - Input Optimization: Parameterize the input

u(t)as a piecewise-constant function. Use an optimization algorithm to maximizelog(det(F))by adjusting the sequence of input levels, subject to bounds (e.g., non-negative, below cytotoxic level). This often results in a pseudo-random binary sequence (PRBS)-like input that dynamically perturbs the system [18]. - In-Silico Validation: Compare the parameter covariance matrix from the optimal dynamic input versus a constant input via simulated experiments.

- Sensitivity Analysis: For the nonlinear ODE model

Data Presentation: Optimality Criteria Comparison

The choice of optimality criterion depends on the primary goal of the experimental design. The table below summarizes key properties [17] [15] [18].

| Optimality Criterion | Mathematical Objective | Primary Goal | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| D-Optimality | Maximize det( FIM ) |

Minimize the joint confidence ellipsoid volume for all parameters. | General purpose; promotes overall parameter identifiability. |

| A-Optimality | Minimize trace( FIM⁻¹ ) |

Minimize the average variance of parameter estimates. | Good for balanced precision across parameters. |

| V-Optimality | Minimize trace( W * FIM⁻¹ ) |

Minimize the average prediction variance over a region of interest (matrix W). |

Best for ensuring accurate model predictions. |

| E-Optimality | Maximize λ_min( FIM ) |

Maximize the smallest eigenvalue of the FIM. | Improves the worst-case direction of parameter estimation. |

Visualization: Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: FIM-Based Optimal Design Conceptual Workflow (78 chars)

Diagram 2: Two-Stage Sequential Optimal Design Protocol (59 chars)

Diagram 3: AI-NLME Hybrid Analysis & Design Workflow (65 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential software, packages, and methodological approaches for implementing FIM-based OED in NLME frameworks.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in NLME OED | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monolix | Software Suite | NLME parameter estimation & simulation. Includes the simulx library for optimal design [16]. |

Industry-standard; user-friendly interface for modeling and simulation. |

| Pumas | Software Suite & Language | NLME modeling, simulation, and built-in optimal design capabilities [3]. | Modern, open-source toolkit with a focus on optimal design workflows. |

| PkStaMp Library | Software Library | Construction of D-optimal sampling designs for PK/PD models using advanced FIM approximations [19]. | Useful for improving FIM calculation accuracy via Monte Carlo methods. |

| Stochastic Simulation & Estimation (SSE) | Methodology | Validates the operating characteristics (bias, precision) of a proposed design before running the experiment [3]. | Critical step to confirm that a locally optimal design performs well in practice. |

| Profile Likelihood / Multistart Approach | Diagnostic Methodology | Assesses practical parameter identifiability by exploring the likelihood surface, complementing FIM analysis [16]. | Essential for diagnosing issues that a singular FIM may indicate. |

| Sequential (Two-Stage) Design | Experimental Strategy | Mitigates the "chicken-and-egg" problem of needing parameters to design an experiment [17]. | Highly practical for studies with high variability and limited prior information. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing FIM-Driven Design in Biomedical Research

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting and FAQs

This technical support center is designed within the context of advanced research on optimal experimental design and the Fisher information matrix. It provides targeted guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals encountering practical challenges when implementing Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) frameworks for system optimization and precise parameter estimation [21].

Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) is a systematic methodology that uses a mathematical model of a process to strategically design experiments that maximize information gain for a specific goal, such as precise parameter estimation or model discrimination [21]. Unlike traditional factorial designs, MBDoE leverages current model knowledge and its uncertainties to recommend the most informative experimental conditions [22].

The Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) is central to this framework. For a parameter vector θ, the FIM quantifies the amount of information that observable data carries about the parameters. It is defined as the negative expectation of the Hessian matrix of the log-likelihood function. In practice, for nonlinear models, it is approximated using sensitivity equations. The FIM's inverse provides a lower bound (Cramér-Rao bound) for the variance-covariance matrix of the parameter estimates, making its maximization synonymous with minimizing parameter uncertainty [23].

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow of an MBDoE process driven by the Fisher Information Matrix.

Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, materials, and software tools commonly employed in MBDoE studies, particularly in chemical and biochemical engineering contexts [24] [25] [22].

| Item Name | Category | Function & Application in MBDoE |

|---|---|---|

| gPROMS ProcessBuilder | Software | A high-fidelity process modeling platform used to formulate mechanistic models, perform parameter estimation, and execute MBDoE algorithms for optimal design [22]. |

| Pyomo.DoE | Software | An open-source Python package for designing optimal experiments. It calculates the FIM for a given model and optimizes design variables based on statistical criteria (A-, D-, E-optimality) [26]. |

| Vapourtec R-Series Flow Reactor | Hardware | An automated continuous-flow chemistry system. It enables precise control of reaction conditions (time, temp, flow) and automated sampling, crucial for executing sequential MBDoE protocols [22]. |

| Plackett-Burman Design Libraries | Statistical Tool | A type of fractional factorial design used in initial screening phases to efficiently identify the most influential factors from a large set with minimal experimental runs [25]. |

| Sparse Grid Interpolation Toolbox | Computational Tool | Creates computationally efficient surrogate models for complex, high-dimensional systems. This allows for tractable global optimization of experiments when dealing with significant parametric uncertainty [27]. |

| Definitive Screening Design (DSD) | Statistical Tool | An advanced screening design that can identify main effects and quadratic effects with minimal runs, providing a more informative starting point for optimization than traditional screening designs [25]. |

| Palladium Catalysts (e.g., Pd(OAc)₂) | Chemical Reagent | A common catalyst for cross-coupling and C-H activation reactions often studied using MBDoE to optimize yield and understand complex reaction networks [22]. |

Troubleshooting Common MBDoE Implementation Challenges

Q1: My parameter estimates have extremely high uncertainty or the optimization fails to converge. What could be wrong? This is often a problem of poor practical identifiability, frequently caused by a poorly designed experiment that does not excite the system dynamics sufficiently [22].

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Calculate the FIM for your current experimental design and initial parameter guesses.

- Perform an eigendecomposition of the FIM. The presence of very small eigenvalues indicates that the FIM is ill-conditioned, and certain parameter combinations cannot be uniquely identified from the proposed data [26].

- Solution Protocol (Design-by-Grouping):

- Calculate normalized local parameter sensitivities over the experimental time horizon.

- Group parameters whose sensitivity profiles peak in similar time intervals.

- Use MBDoE to design a separate experiment targeting the precise estimation of each parameter group (e.g., design Experiment A for Group 1 parameters, Experiment B for Group 2) [22].

- Sequentially run these targeted experiments to decouple correlated parameters. This approach was successfully used to estimate kinetic parameters for a C-H activation reaction where full simultaneous estimation was infeasible [22].

Q2: How do I determine the appropriate sample size or number of experimental runs needed for a precise model? Traditional rules of thumb can be insufficient. A modern approach decomposes the Fisher information to link sample size directly to the precision of individual predictions [23].

- Diagnosis: Your model predictions have wide confidence intervals, or performance degrades significantly on validation data.

- Solution Protocol (Five-Step Sample Size Planning):

- Specify the overall outcome risk in your target population.

- Define the anticipated distribution of key predictors in the model.

- Specify an assumed "core model" (e.g., a logistic regression equation with assumed coefficients).

- Use the relationship

Variance(Individual Risk Estimate) ∝ (FIM)^(-1) / Nto decompose the variance of an individual's risk estimate into components from the FIM and sample size (N) [23]. - Calculate the required N to achieve a pre-specified level of precision (e.g., confidence interval width) for predictions at critical predictor values. This method is implemented in software like

pmstabilityss[23].

Q3: Should I use "Classical" MBDoE or Bayesian Optimization (BO) for my problem? The choice depends entirely on the primary objective [28].

- Use Classical MBDoE when:

- Your goal is parameter estimation, model discrimination, or understanding factor effects.

- You have a first-principles or semi-mechanistic model you wish to calibrate.

- You need to account for blocking factors or randomization to avoid time-trend biases [28].

- Use Bayesian Optimization when:

- Your sole goal is to find a global optimum (e.g., maximum yield) of a black-box function.

- You are optimizing hyperparameters of a machine learning model.

- Evaluating the system is extremely expensive, and you need a sample-efficient global search [28].

- Solution: Clearly define your objective. For comprehensive model development and validation, classical MBDoE is essential. BO can be a complementary tool for pure optimization tasks once a model is established.

Q4: The computational cost of solving the MBDoE optimization problem is prohibitive for my large-scale model. Are there efficient alternatives? Yes, this is a common challenge with nonlinear, high-dimensional models. An optimization-free, FIM-driven approach has been developed to address this [29].

- Diagnosis: The nested optimization loop (outer loop: design variables, inner loop: parameter estimation/FIM calculation) is too slow for online or high-throughput application.

- Solution Protocol (FIM-Driven Ranking):

- Define a candidate set of feasible experiments based on practical constraints.

- For each candidate experiment, compute or approximate its expected FIM.

- Rank all candidates based on an optimality criterion (e.g., determinant of FIM).

- Select and run the top-ranked experiment. This sampling-and-ranking method avoids the costly nonlinear optimization step while still providing highly informative designs and has been demonstrated in fed-batch bioreactor and flow chemistry case studies [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

The following table summarizes quantitative results and methodologies from pivotal MBDoE implementations, providing a benchmark for experimental design.

Table: Summary of MBDoE Case Studies & Outcomes

| Study Focus | Model & System | MBDoE Strategy | Key Quantitative Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-H Activation Flow Process | Pd-catalyzed aziridine formation; 4 kinetic parameters. | Sequential MBDoE with parameter grouping. D-optimal design in gPROMS. | 8 designed experiments with 5-11 samples each reduced parameter confidence intervals by >70% compared to initial DFT guesses [22]. | [22] |

| Benchmark Reaction Kinetics | Consecutive reactions A → B → C in batch; 4 Arrhenius params. |

FIM analysis & A-/D-/E-optimal design via Pyomo.DoE. | Identified unidentifiable parameters from initial data; a designed experiment at T=350K, CA0=2.0M increased min FIM eigenvalue by 500% [26]. | [26] |

| Dynamical Uncertainty Reduction | 19-dimensional T-cell receptor signaling model. | Global MBDoE using sparse grid surrogates & greedy input search. | Designed input sequence & 4 measurement pairs reduced the dynamical uncertainty region of target states by 99% in silico [27]. | [27] |

| Genetic Pathway Optimization | Metabolic engineering for product yield. | Definitive Screening Design (DSD) for screening, followed by RSM. | DSD evaluated 7 promoter strength factors with only 13 runs, correctly identifying 3 key factors for subsequent optimization [25]. | [25] |

Protocol: MBDoE for Kinetic Model Identification in Flow [22]

- Objective: Precisely estimate activation energies (Ea) and pre-exponential factors (k_ref) for a catalytic reaction network.

- Pre-experimental Setup:

- Define Priors: Obtain initial parameter estimates and uncertainties from Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations or literature.

- Define Constraints: Specify operational bounds (e.g., Tmin, Tmax, concentration limits to avoid precipitation).

- Sequential Experimental Procedure:

- Sensitivity Analysis: Simulate the model with prior parameters to calculate the time-dependent sensitivity coefficients for each parameter.

- Parameter Grouping: Plot normalized sensitivity profiles. Group parameters with maxima in the same time region (e.g., all

k_refparameters). - Design Generation: For a selected parameter group, formulate a D-optimal MBDoE problem to maximize the determinant of the FIM for those parameters. Decision variables are typically initial concentrations, temperature, and sample times.

- Experiment Execution: Implement the designed conditions in an automated flow reactor (e.g., Vapourtec R2+). Use sample loops for precise reagent delivery and an in-line UV cell/GC for analysis.

- Parameter Estimation: Fit the model to the new data, updating only the targeted parameter group.

- Iteration: Update the model with new parameter estimates and uncertainties. Return to Step 1 to design an experiment for the next parameter group. Iterate until all parameter confidence intervals are satisfactorily small.

Advanced Topics: Optimization Frameworks and Future Directions

The field is evolving beyond local FIM-based optimization. The diagram below contrasts the classical local MBDoE approach with a modern global framework designed to manage significant parametric uncertainty.

Future Directions: Research is focusing on hybridizing classical and Bayesian approaches, creating robust designs for large uncertainty sets, and developing open-source, scalable software (like the tools described by Wang and Dowling [24]) to make these advanced MBDoE techniques accessible for broader applications in pharmaceuticals, biomolecular engineering, and materials science [21].

This technical support center is dedicated to the implementation and troubleshooting of the Fisher Information Matrix Driven (FIMD) approach for the online design of experiments (DoE). This method provides an optimization-free alternative to traditional Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE), which relies on computationally intensive optimization procedures that can be prone to local optimality and sensitivity to parametric uncertainty [11].

The core innovation of the FIMD method is its ranking-based selection of experiments. Instead of solving a complex optimization problem at each step, a candidate set of possible experiments is generated. Each candidate is evaluated based on its contribution to the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM), a mathematical measure of the amount of information an observable random variable carries about unknown parameters of a model [2]. The experiment that maximizes a chosen criterion of the FIM (such as the D-criterion) is selected and executed. This process iterates rapidly, allowing for fast online adaptation and reduction of parameter uncertainty in applications such as autonomous kinetic model identification platforms [11].

Diagram 1: Workflow of the FIMD Ranking-Based Approach

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Core Concept & Implementation Issues

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of the ranking-based FIMD approach over standard MBDoE? The primary advantage is the elimination of the nonlinear optimization loop. Standard MBDoE requires solving a constrained optimization problem to find the single best experiment, which is computationally heavy and can get stuck in local optima. The FIMD method replaces this with a ranking procedure over a sampled candidate set. This leads to a dramatic reduction in computational time per design cycle, enabling true online and real-time experimental design, which is critical for autonomous platforms in chemical and pharmaceutical development [11].

Q2: When generating the candidate set of experiments, what are common pitfalls and how can I avoid them? A poorly designed candidate set will limit the effectiveness of the ranking method.

- Pitfall 1: Poor Coverage. Candidates clustered in a small region of the experimental design space (e.g., time, temperature, concentration) will not provide informative choices.

- Solution: Use a space-filling sampling method (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to ensure broad and uniform coverage of the allowable operational ranges.

- Pitfall 2: Excessive Size. A very large candidate set makes the ranking calculation inefficient.

- Solution: Determine a sufficient sample size through preliminary tests. A number between 100 and 1000 candidates is often effective, balancing thoroughness with computational speed for online use.

- Pitfall 3: Static Candidates. Using the same fixed candidate set for every iteration.

- Solution: Implement adaptive candidate generation. For example, after several iterations, you can bias the sampling towards regions of the design space that have proven to be more informative.

Fisher Information Matrix Calculation & Approximation

Q3: What are FO and FOCE approximations of the FIM, and which should I use? In nonlinear mixed-effects models common in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) research, the exact FIM cannot be derived analytically. Approximations are necessary [8].

- First Order (FO): Linearizes the model around the typical parameter values (random effects set to zero). It is computationally fast but can be inaccurate if inter-individual variability is high or the model is highly nonlinear [8].

- First Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE): Linearizes around conditional estimates of the random effects. It is more accurate but computationally more intensive than FO [8].

Selection Guidance: Start with the FO approximation for initial testing and rapid prototyping of your FIMD workflow. For final design and analysis, especially with complex biological models, use the FOCE approximation to ensure reliability. Research indicates that FOCE leads to designs with more support points and less clustering of samples, which can be more robust [8].

Q4: What is the difference between the "Full FIM" and "Block-Diagonal FIM," and why does it matter? This relates to the structure of the FIM when estimating both fixed effect parameters (β) and variance parameters (ω², σ²) [8].

- Full FIM: Accounts for potential correlations between the uncertainty in fixed effects and variance parameters.

- Block-Diagonal FIM: Assumes these uncertainties are independent, simplifying the matrix into two separate blocks.

Impact: Using the block-diagonal approximation is simpler and faster. While studies show comparable performance when model parameters are correctly specified, the full FIM implementation can produce designs that are more robust to parameter misspecification at the design stage [8]. If your initial parameter guesses are poor, the full FIM is the safer choice.

Diagram 2: Key Approximations and Structures of the Fisher Information Matrix

Performance & Validation

Q5: How do I quantitatively validate that my FIMD implementation is working correctly? You should compare its performance against a benchmark. The standard methodology involves simulation and estimation:

- Simulate Data: Use a known model with known ("true") parameters to generate synthetic datasets based on the designed experiments.

- Re-estimate Parameters: Fit the model to each simulated dataset to obtain estimates.

- Calculate Metrics:

- Bias: Difference between the mean of estimated parameters and the true value.

- Precision: Relative Standard Error (RSE%) of the estimates.

- Empirical D-criterion: Calculate the determinant of the inverse empirical variance-covariance matrix from the simulations. A higher value indicates a more informative design [8].

Table 1: Expected Comparative Performance of FIMD vs. Standard MBDoE

| Metric | Standard MBDoE | FIMD (Ranking-Based) | Rationale & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Time per Design Cycle | High | Low (up to 10-50x faster) [11] | FIMD avoids nonlinear optimization. |

| Quality of Final Design | High (when converging to global optimum) | Comparable/High | Ranking on FIM criteria directly targets information gain. |

| Robustness to Initial Guess | Low (risk of local optima) | Higher | Sampling-based candidate generation explores space broadly. |

| Suitability for Online/Real-Time Use | Low | High | Low cycle time enables immediate feedback. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: Benchmarking on a Fed-Batch Bioreactor

This protocol is based on a published case study for kinetic model identification [11].

- Objective: Estimate the parameters of a Monod-type kinetic model for baker’s yeast fermentation.

- System: Simulated fed-batch reactor. The model includes state equations for biomass, substrate, and product.

- FIMD Implementation:

- Design Variables: Feed flow rate and sampling times for concentration measurements.

- Candidate Generation: Sample 500 candidate feed profiles (piece-wise constant) within operational bounds.

- Ranking Criterion: D-optimality (maximize determinant of FIM).

- Update: After each "experiment" (simulated run), parameters are re-estimated via maximum likelihood.

- Validation: Perform 100 simulation-estimation runs. Compare the mean squared error and parameter identifiability (RSE% < 50%) against designs from a traditional MBDoE optimizer.

Protocol 2: Robustness Test with Parameter Misspecification

This tests the method's performance under realistic conditions of poor initial guesses [8].

- Objective: Design an optimal sampling schedule for a pharmacokinetic (PK) model (e.g., a one-compartment IV bolus model).

- Procedure: a. Use perturbed parameters (e.g., 50% error on clearance and volume) as the initial guess for design. b. Run the FIMD algorithm (using both FO and FOCE approximations) to generate an optimal sampling schedule. c. Evaluate this schedule by simulating data using the true parameters. d. Fit the model to this data multiple times and compute the empirical bias and precision.

- Success Criteria: A robust design will yield low bias (<10%) and acceptable precision (RSE% < 30%) for key parameters (e.g., clearance) even when designed with misspecified values.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FIMD Implementation

| Reagent / Tool | Function in FIMD Research | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Modeling Software (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix, nlmixr) | Provides the environment for defining the mechanistic model, calculating FIM approximations (FO/FOCE), and performing parameter estimation. | Essential for pharmacometric and complex kinetic applications [8]. |

| Scientific Computing Environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python with SciPy/NumPy, R) | Used to implement the core FIMD algorithm: candidate generation, FIM calculation, ranking, and iterative control logic. | Python/R offer open-source flexibility; MATLAB has dedicated toolboxes. |

| D-Optimality Criterion | The scalar objective function for ranking experiments. Maximizing det(FIM) minimizes the volume of the confidence ellipsoid of the parameters. | The most common criterion for parameter precision [11] [8]. |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) Algorithm | A statistical method for generating a near-random, space-filling distribution of candidate experiments within specified ranges. | Superior to random sampling for ensuring coverage of the design space. |

| Cramér-Rao Lower Bound (CRLB) | The inverse of the FIM. Provides a theoretical lower bound on the variance of any unbiased parameter estimator. Used to predict best-case precision from a design [2]. | A key metric for evaluating the potential information content of a designed experiment before it is run. |

| Model-Based Design of Experiments (MBDoE) Software (e.g., gPROMS, JMP Pro) | Serves as a benchmark. Its traditional optimization-based designs are used for comparative performance analysis against the FIMD method [11]. | Critical for validating that the FIMD method achieves comparable or superior efficiency. |

Within the framework of optimal experimental design (OED) for nonlinear mixed-effects models (NLMEM), the Population Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) serves as the fundamental mathematical object for evaluating and optimizing study designs in fields like pharmacometrics and drug development [30] [31]. It quantifies the expected information that observed data carries about the unknown model parameters (both fixed effects and variances of random effects). The core objective is to design experiments that maximize a scalar function of the Population FIM (e.g., its determinant, known as D-optimality), thereby minimizing the asymptotic uncertainty of parameter estimates [31].

Prior to the adoption of FIM-based methods, design evaluation relied heavily on computationally expensive Clinical Trial Simulation (CTS), which involved simulating and fitting thousands of datasets for each candidate design [31]. The derivation of an approximate expression for the Population FIM for NLMEMs provided a direct, analytical pathway to predict the precision of parameter estimates, revolutionizing the efficiency of designing population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies [31]. This article establishes a technical support center to empower researchers in successfully implementing these critical computational methods.

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an Individual FIM and a Population FIM?

- A: The Individual FIM is calculated for a single subject's data given a known set of their individual parameters. The Population FIM, crucial for population design, accounts for the hierarchy of data: it measures the information about the population's typical parameters (fixed effects) and the inter-individual variability (variance of random effects) by integrating over all possible individual parameter realizations given the population model [31].

Q2: Why is the Population FIM only an approximation, and what are the common approximations used?

- A: The exact likelihood for NLMEMs is often intractable. Therefore, approximations are used to calculate the FIM. The most common is the First-Order (FO) linearization approximation, which linearizes the model around the random effects [31]. Some software also offer the First-Order Conditional Estimation (FOCE) approximation, which can be more accurate but is computationally heavier. For most PK/PD models, the FO approximation provides a reliable and efficient balance for design purposes [31].

Q3: My software returns a singular or non-positive definite FIM. What does this mean and how can I fix it?

- A: A singular FIM indicates that your design is insufficient to estimate all parameters—some parameters are non-identifiable under that design. Common causes include [30]:

- Over-parameterization: The model has too many parameters for the proposed data (e.g., sampling times). Simplify the model or add sampling points.

- Poor Design: Sampling times may be clustered, failing to inform certain model dynamics (e.g., absorption vs. elimination). Use optimal design algorithms to find more informative time points.

- Redundant Parameters: Two parameters may be perfectly correlated based on the design. Review parameter correlations in the FIM.

- A: A singular FIM indicates that your design is insufficient to estimate all parameters—some parameters are non-identifiable under that design. Common causes include [30]:

Q4: How do I validate that a design optimized using the predicted FIM will perform well in practice?

- A: The gold standard for validation is Clinical Trial Simulation (CTS). After obtaining an optimal design via FIM maximization, use it as a template to simulate a large number (e.g., 500-1000) of virtual patient datasets. Estimate parameters from each simulated dataset and compare the empirical standard errors of the estimates to the standard errors predicted by the FIM. Close agreement confirms the design's robustness [31].

Q5: What software tools are specifically designed for Population FIM calculation and optimal design?

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Errors and Solutions

| Error / Symptom | Likely Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Failed convergence of optimization algorithm | Design space is too large or constraints are conflicting; algorithm stuck in local optimum. | 1. Simplify the problem: Reduce the number of variable design parameters [11].2. Use multiple starting points for the optimization.3. Switch optimization algorithms (e.g., from Fedorov-Wynn to a stochastic method). |

| Large discrepancy between FIM-predicted SE and CTS-empirical SE | The FO linearization approximation may be inadequate for a highly nonlinear model at the proposed dose/sampling design. | 1. Switch to a more accurate FIM approximation (e.g., FOCE) if available.2. Use the FIM-based design as a starting point, then refine using a limited, focused CTS [31]. |

| Optimal design suggests logistically impossible sampling times | The optimization is purely mathematical and ignores practical constraints. | 1. Incorporate sampling windows (flexible time intervals) into the optimization.2. Add constraints to force a minimum time between samples or to align with clinic visits. |

| Software crashes when evaluating FIM for a complex ODE model | Numerical instability in solving ODEs or calculating derivatives. | 1. Check ODE solver tolerances and ensure the model is numerically stable.2. Use the software's built-in analytical model library if a suitable approximation exists.3. Simplify the PD model structure if possible. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential software "reagents" for performing Population FIM calculations and optimal design [31] [32].

| Software Tool | Primary Function | Key Feature / Application | Access / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFIM | Design evaluation & optimization for NLMEM. | Implements FO and FOCE approximations; continuous and discrete optimization; R package. | R (CRAN) [32] |

| PopED | Optimal experimental design for population & individual studies. | Flexible for complex models (ODEs), robust design, graphical output; R package. | R (CRAN) [32] |

| POPT / WinPOPT | Optimization of population PK/PD trial designs. | User-friendly interface (WinPOPT); handles crossover and multiple response models. | Standalone [31] |

| PopDes | Design evaluation for nonlinear mixed effects models. | ||

| PkStaMp | Design evaluation based on population FIM. | ||

| IQR Tools | Modeling & simulation suite. | Interfaces with PopED for optimal design; integrates systems pharmacology. | R Package [32] |

| Monolix & Simulx | Integrated PK/PD modeling & simulation platform. | Includes design evaluation/optimization features based on the Population FIM. | Commercial (Lixoft) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evaluating a Candidate Design Using the Population FIM Objective: To assess the predicted parameter precision of a proposed population PK study design.

- Define Pharmacometric Model: Specify the structural PK model (e.g., 1-compartment with oral absorption), statistical model (inter-individual variability on parameters), and residual error model. Fix all parameters to literature-based nominal values [31].

- Define Candidate Design: Specify the design variables: number of subjects (

N), number of samples per subject (n), dose amount (D), and a vector of sampling times (t₁, t₂, ... tₙ). - Compute Population FIM: Use software (e.g., PFIM, PopED) to calculate the FIM using the FO approximation for the given design and model [31].

- Derive Statistics: Calculate the asymptotic variance-covariance matrix as the inverse of the FIM. Extract the Relative Standard Error (RSE %) for each parameter:

RSE% = 100 * sqrt(Cᵢᵢ) / θᵢ, whereCᵢᵢis the diagonal element (variance) for the i-th parameterθᵢ. - Evaluate: A design is generally considered informative if the predicted RSE% for key parameters (e.g., clearance) is below a target threshold (e.g., 30%).

Protocol 2: Validating an Optimal Design via Clinical Trial Simulation Objective: To empirically verify the operating characteristics of a design obtained through FIM-based optimization [31].

- Generate Optimal Design: Using Protocol 1, employ an optimization algorithm (e.g., in PopED) to find the sampling times that maximize the determinant of the FIM (D-optimality).

- Simulate Virtual Trials: Using the optimized design and the same nominal parameter values, simulate

M(e.g., 500) replicates of the full clinical trial dataset, incorporating inter-individual and residual variability. - Estimate Parameters: Fit the pre-specified NLMEM to each of the

Msimulated datasets using a standard estimation tool (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix). - Compare Precision: For each parameter, calculate the empirical standard error as the standard deviation of its

Mestimates. Plot these against the FIM-predicted standard errors. Good agreement (points near the line of unity) validates the FIM approximation and the optimal design's performance.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Diagram: Population FIM Calculation & Design Workflow (100 chars)

Diagram: Online FIM-Driven Experiment Design (100 chars)

Data Presentation: Software and Method Comparisons

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Software Tools for Population FIM & Optimal Design [31] [32]

| Software | Primary Language/Platform | Key Approximation(s) for FIM | Notable Features for Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFIM | R | FO, FOCE | Continuous & discrete optimization, library of built-in models. |

| PopED | R | FO, FOCE, Laplace | Highly flexible for complex models (ODEs), robust & group designs. |

| POPT/WinPOPT | Standalone (C++ / GUI) | FO | User-friendly interface, handles crossover designs. |

| PopDes | FO | ||

| PkStaMp | FO |

Table 2: Computational Methods for Fisher Information Matrix Estimation [30]

| Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations / Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Derivation | Exact calculation of derivatives of the log-likelihood. | Maximum accuracy, no simulation noise. | Only possible for simple models with tractable likelihoods. |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Estimate expectation by averaging over simulated datasets. | General-purpose, applicable to complex models. | Computationally expensive; variance requires many simulations. |

| First-Order Linearization | Approximates NLMEM by linearizing around random effects. | Fast, standard for population PK/PD optimal design. | May be inaccurate for highly nonlinear models in certain regions. |

| Variance-Reduced MC | Uses independent perturbations per data point to reduce noise. | More reliable error bounds with fewer simulations. | Increased per-simulation cost [30]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center provides solutions for common challenges in Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) study design and clinical trial optimization, framed within the context of optimal experimental design and Fisher information matrix research.

Core Concept: Fisher Information in PK/PD Design

The Fisher information matrix (I(θ)) quantifies the amount of information an observable random variable carries about an unknown parameter (θ) of its distribution [2]. In PK/PD, it measures the precision of parameter estimates (e.g., clearance, volume, EC₅₀) from concentration-time and effect-time data. Maximizing Fisher information is the mathematical principle behind optimizing sampling schedules and trial designs to reduce parameter uncertainty.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PK/PD Study Challenges

Problem 1: Inadequate Data Quality for Model Development

- Symptoms: Poor model fit, high parameter uncertainty, failure to identify significant covariates, model instability.

- Root Cause: Errors in source data, incorrect NONMEM data formatting, or incomplete data handling rules [33].

- Solution - Implement a Quality Control (QC) Checklist:

- Pre-Modeling QC: Verify units, date/time consistency, and handling of missing/blinded data in source datasets [33].

- Input QC: Ensure NONMEM data files have correct