Overcoming Enzyme Denaturation: AI-Driven Stabilization Strategies for Harsh Conditions in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive overview of innovative strategies to combat enzyme denaturation, a critical challenge that compromises therapeutic efficacy and industrial application.

Overcoming Enzyme Denaturation: AI-Driven Stabilization Strategies for Harsh Conditions in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of innovative strategies to combat enzyme denaturation, a critical challenge that compromises therapeutic efficacy and industrial application. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental mechanisms of denaturation caused by temperature, pH, and chemical stressors. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodological advances, including machine learning-guided enzyme engineering, the use of stabilizing additives, and data-driven protein design. It further covers practical troubleshooting for optimizing enzyme stability in formulation and manufacturing, alongside rigorous validation frameworks required for regulatory compliance and clinical translation. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest technological breakthroughs, this resource aims to equip scientists with the tools to develop more robust and effective enzyme-based solutions.

The Enzyme Stability Crisis: Understanding Denaturation Mechanisms in Hostile Environments

FAQs: Understanding Denaturation

What is denaturation, and why is it a critical concern in biopharmaceutical research? Denaturation is the process where proteins or DNA lose their functional, three-dimensional structure due to external stressors. This loss of structure leads directly to a loss of function. In drug development, this is critical because it can deactivate therapeutic enzymes, cause irreversible aggregation of protein-based drugs, and compromise the validity of high-throughput screening assays, leading to failed experiments and costly losses.

Is denaturation always irreversible? No, denaturation can be either reversible or irreversible. The reversibility depends on the protein and the severity of the denaturing conditions. Irreversible denaturation often occurs when the conditions cause the protein to aggregate, as unfolded regions that are normally buried become exposed and stick together. However, some proteins can refold into their native structure when the denaturing stress is removed [1].

What are the most common causes of denaturation in a laboratory setting? The primary causes of denaturation can be categorized as follows:

- Temperature: High temperatures provide enough kinetic energy to break the weak hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions that stabilize protein structure. While cold temperatures slow enzyme function, they do not typically cause denaturation [1].

- pH Extremes: Highly acidic or basic conditions can alter the charge of amino acid side chains, disrupting the salt bridges and hydrogen bonding networks essential for structure [1].

- Organic Solvents: Water-miscible solvents can strip the essential hydration shell from a protein's surface and bind to the partially dehydrated protein, leading to a conformational change and loss of activity [2].

- Chemical Denaturants: Chaotropic agents like urea and guanidine hydrochloride (GdmCl) disrupt the hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions within a protein, leading to unfolding [3].

- High Salt Concentration: For non-halophilic proteins, very high salt concentrations can compete for essential water molecules, leading to dehydration, aggregation, and precipitation [4].

How can we experimentally confirm that our protein sample has denatured? Several biophysical techniques can confirm denaturation:

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: A loss of signal in the far-UV region indicates a disruption of the protein's secondary structure (e.g., alpha-helices, beta-sheets) [4].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Measures the heat capacity of a protein as it is heated. Denaturation is observed as an endothermic peak, and the midpoint of this transition (Tm) indicates the protein's thermal stability [5].

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Tryptophan residues buried in the native protein become exposed to the solvent upon unfolding, causing a shift in their intrinsic fluorescence emission spectrum [3].

- Mass Photometry: Can be used under denaturing conditions (dMP) to monitor the dissociation of protein complexes into monomers, confirming the loss of quaternary structure [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Preventing and Managing Denaturation

This guide addresses common experimental issues related to denaturation.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of enzyme activity after purification | Exposure to low salt buffers, leading to unfolding. | Dialyze into a stabilizing buffer. For halophilic enzymes, maintain high salt (e.g., 1-4 M NaCl or KCl) as per the specific enzyme's requirement [4]. |

| Protein aggregation during storage | Repeated freeze-thaw cycles, or storage in a dilute, salt-free buffer. | Add stabilizing agents like glycerol or sucrose. Store in aliquots to avoid freeze-thaw cycles. Increase protein concentration or add a carrier protein like BSA [2]. |

| Inconsistent enzyme kinetics data | Partial, temperature-dependent denaturation during the assay. | Use a temperature control unit. Characterize your enzyme's activity and stability at the assay temperature, as kinetics are highly temperature-dependent [5]. |

| Unexpected bands on SDS-PAGE after cross-linking | Formation of non-specific, denatured aggregates due to harsh cross-linking conditions. | Optimize cross-linker concentration, reaction time, and temperature. Use denaturing Mass Photometry (dMP) for rapid optimization, as it provides accurate mass identification and quantification of all species [6]. |

Advanced Stabilization Strategies

For experiments in highly denaturing conditions, such as those involving organic solvents, consider these advanced methodologies:

- Enzyme Immobilization: Covalently attaching enzymes to a solid support provides high conformational rigidity, allowing them to retain activity in the presence of significant amounts of organic co-solvents [2].

- Forming Polyplexes: Forming complexes between enzymes and polyelectrolytes (e.g., polycations or polyanions) through multiple electrostatic interactions can protect the enzyme from inactivation. These complexes remain stable in low-dielectric media like organic solvents [2].

- Surface Modification: Chemically modifying the enzyme's surface with polar or charged groups (e.g., using pyromellitic anhydride) increases its affinity for water, retarding dehydration caused by organic solvents [2].

- Learning from Halophiles: Halophilic (salt-loving) enzymes have evolved acidic, hydrophilic surfaces that maintain a hydration shell in high-salt environments. This principle can be mimicked in protein engineering to create more stable enzymes [4].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Assessing Thermal Stability via Multi-Temperature Crystallography

This protocol uses serial crystallography to capture enzyme structure and kinetics at physiological temperatures [5].

- Protein Crystallization: Generate a large batch of microcrystals of your target enzyme (e.g., β-lactamase CTX-M-14 or xylose isomerase) to ensure consistency.

- Environmental Control: Load crystals onto a fixed-target 'HARE' chip and place it within an environmental control box. This box uses closed-loop control circuits to maintain precise temperature and relative humidity.

- Data Collection: Raster-scan the chip through an X-ray beam to collect diffraction data. Collect sequential datasets at a range of temperatures (e.g., from 10°C to 70°C).

- Reaction Initiation (for time-resolved studies): Use the LAMA (liquid-application method) to mix soluble ligands (substrates) with the crystals directly on the chip, initiating the enzymatic reaction.

- Data Analysis: Determine the enzyme's structure at each temperature. Analyze the Atomic Displacement Parameters (ADPs) to quantify structural dynamics. Correlate structural changes with measured turnover kinetics (kcat) at each temperature.

The workflow for this protocol is illustrated below.

Quantitative Data on Denaturation

The following table summarizes experimental data on how environmental factors induce denaturation and the corresponding protective effects of stabilization strategies.

Table 1: Denaturation Triggers and Stabilization Efficacy

| Denaturation Stressor | Observed Effect on Protein | Measured Protective Strategy | Result of Stabilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvents (e.g., Methanol) | Threshold-like drop in activity at ~40 vol.% [2]. | Chymotrypsin immobilized to polyacrylamide gel [2]. | Retained activity at 60 vol.% methanol (20% higher than native) [2]. |

| Urea (Chemical Denaturant) | Unfolding midpoint (C_M) of BsCspB at 2.7 M [3]. | Adding 120 g/L PEG1 (crowding agent) [3]. | C_M shifted to 3.3 M urea; ΔΔG increased by ~1.4 kJ/mol [3]. |

| Temperature (on CTX-M-14 β-lactamase) | Modulation of turnover kinetics and structural dynamics [5]. | N/A (Inherent property measured) | Direct correlation between temperature, atomic displacement dynamics, and catalytic rate [5]. |

| Low Salt (on Halophilic Malate Dehydrogenase) | Complete loss of activity and secondary structure at 0 M NaCl [4]. | Maintaining 4.0 M NaCl [4]. | Full enzymatic activity and structured ellipticity in CD spectra [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This table details essential materials used in research focused on understanding and preventing denaturation.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Denaturation Research

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropes (Urea, Guanidine HCl) | Chemical denaturants used to induce unfolding and measure protein stability [3]. | Disrupts hydrogen bonding networks within the protein. |

| Crowding Agents (PEG, Dextran) | Mimic the crowded intracellular environment; can stabilize proteins via the excluded volume effect [3]. | Increases thermodynamic stability and can shift unfolding midpoints. |

| Halophilic Enzymes (e.g., Halophilic MDH) | Model systems for studying structural adaptations to extreme conditions [4]. | Rich in acidic surface residues, requires high salt for stability. |

| Chemical Cross-linkers (e.g., DSS/BS3) | Covalently link proximal amino acids to stabilize protein complexes and provide structural insights [7]. | Homo-bifunctional, amine-reactive, with defined spacer arm lengths. |

| Polyelectrolytes (e.g., Polybrene) | Form multi-point, non-covalent complexes with enzymes to increase rigidity in organic solvents [2]. | Provides reversible stabilization through electrostatic interactions. |

The relationships between different stabilization strategies and their core principles are mapped in the following diagram.

Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating Protein Denaturation

This guide helps researchers diagnose and understand the fundamental stressors that disrupt protein structure during experiments.

| Stressor Type | Primary Mechanism of Action | Observed Experimental Consequences | Key Structural Levels Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (High) | Disrupts weak, non-covalent interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions); increases molecular agitation leading to unfolding [8] [9]. | Loss of activity; increased turbidity or aggregation; observable precipitation [8] [10]. | Secondary, Tertiary, Quaternary [8]. |

| Temperature (Low/Cold) | Disrupts the hydrophobic effect and hydration shells, potentially destabilizing the protein core below the freezing point [8]. | Loss of activity, often reversible upon warming; can occur below solution freezing point [8]. | Tertiary, Quaternary [8]. |

| pH (Extremes) | Alters the charge states of amino acid side chains, disrupting ionic bonds and hydrogen bonding networks [9] [11]. | Loss of solubility; precipitation; sharp decline in enzymatic activity outside optimal range [9] [11]. | Secondary, Tertiary, Quaternary [9]. |

| Chemical Denaturants (Urea, GdnHCl) | Destabilize the native structure by forming more favorable interactions with the peptide backbone than the protein-internal hydrogen bonds, thereby solubilizing unfolded state [12]. | Unfolding and loss of function; increased susceptibility to proteolysis; used to measure protein stability (Tm) [8] [12]. | Secondary, Tertiary [8] [12]. |

| Organic Solvents | Perturbs the dielectric constant of the medium and disrupts hydrophobic interactions critical for the protein core [8] [9]. | Loss of activity; possible conformational change or precipitation [9]. | Tertiary, Quaternary [9]. |

| Detergents (e.g., SDS) | Binds extensively to the protein chain, overwhelming native interactions and imparting a strong negative charge, which unfolds the structure [8]. | Extensive unfolding; loss of native function; used in denaturing gel electrophoresis [8]. | Secondary, Tertiary, Quaternary [8]. |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Hg, Pb) | Form complexes with functional side chains (e.g., thiols of cysteine), oxidize residues, or displace essential metal cofactors [9]. | Irreversible inactivation; non-specific aggregation or precipitation [9]. | Tertiary (can disrupt primary if disulfides cleaved) [9]. |

| Interfacial Stresses (Ice-Water, Air-Water) | Disruption of the protein's hydrophobic core due to direct interactions with the interface [8]. | Surface-induced denaturation and aggregation [8]. | Tertiary [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most immediate signs that my protein has denatured during an experiment?

The most common indicators are a precipitate or increased turbidity in your solution and a complete or near-complete loss of biological activity. In assays, you may observe a sudden drop in the reaction rate. Techniques like differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) or circular dichroism (CD) can directly confirm a loss of native structure by showing a decrease in the melting temperature (Tm) or a change in the secondary structure spectrum [8] [10].

Is protein denaturation always irreversible?

No, denaturation can be reversible. Reversible denaturation occurs when the polypeptide chain is stabilized in its unfolded state by the denaturing agent but can spontaneously refold into its native, active conformation once the stressor is removed, provided the primary structure is intact. Irreversible denaturation often happens when unfolded chains interact and form stabilized aggregates, or when reactive groups like thiols become exposed and form incorrect disulfide bonds upon unfolding [8] [9]. For example, the protein ribonuclease A can refold after denaturation by urea and reduction, while a boiled egg white protein cannot [8] [9].

How can I determine the thermodynamic stability (ΔG) of my protein, and what are the challenges?

Protein stability (ΔG0D) is thermodynamically defined as the Gibbs free energy change for the transition from the native (N) to the denatured (D) state under physiological conditions. In practice, this quantity is typically measured by inducing denaturation with chemical denaturants like guanidinium chloride (GdnHCl) or urea and monitoring the unfolding transition using spectroscopic methods. A significant challenge is that the stability value under physiological conditions (ΔG0D) must be extrapolated from data obtained in denaturant solutions, and different extrapolation methods can yield different values, eroding confidence in the absolute number [12]. Furthermore, these in vitro measurements in dilute buffers ignore the "crowding effect" of the in vivo environment [12].

My therapeutic protein is prone to aggregation. What formulation strategies can enhance its stability?

Yes, formulation buffers are a primary tool for increasing stability. Key strategies include:

- pH Optimization: Finding the right pH is critical for stability [10].

- Additives/Excipients:

- Salts: Can help balance ionic strength [10].

- Sugars (e.g., sucrose, trehalose): Act as stabilizers and help with protein hydration [10].

- Amino Acids (e.g., glycine, arginine): Can help balance charges and suppress aggregation [10].

- Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbate 80): Protect the protein from aggregation at interfaces by acting as emulsifiers [8] [10].

- It is essential to verify that any additive does not negatively impact the protein's structure or function [10].

What is enzyme immobilization, and how can it protect against denaturation?

Enzyme immobilization involves binding or entrapping enzyme molecules to a solid support or within a carrier material. This process can significantly enhance stability against temperature, pH, solvents, and impurities. It works by limiting the mobility of the enzyme molecule, thereby reducing its tendency to unfold, and can provide a protective microenvironment. Common techniques include adsorption, covalent binding, and encapsulation [13]. For instance, covalent immobilization can create multiple attachment points between the enzyme and the support, dramatically rigidifying the structure and preventing unfolding [13].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Determining Melting Temperature (Tm) via Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF)

Purpose: To quantify the thermal stability of a protein and the potential stabilizing effects of ligands or buffer conditions.

Principle: A fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) binds to hydrophobic patches of the protein that become exposed during unfolding. The fluorescence intensity increases as the protein denatures, allowing the melting temperature (Tm) to be determined [10].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a protein solution (e.g., 0.1 - 1 mg/mL) in the buffer of interest. Include a 1:1000 dilution of SYPRO Orange dye. If testing, include your ligand or additive in the experimental sample.

- Plate Setup: Load the samples into a real-time PCR plate or a suitable thermostable plate.

- Run the Assay: Using a real-time PCR machine or other thermal gradient instrument, heat the plate from 25°C to 95°C with a gradual ramp rate (e.g., 1°C per minute). Monitor the fluorescence signal continuously.

- Data Analysis: Plot the fluorescence intensity as a function of temperature. The Tm is defined as the midpoint of the unfolding transition, where 50% of the protein is unfolded [10]. A higher Tm indicates a more stable protein.

Protocol 2: Assessing Structural Stability Using Microfluidic Modulation Spectroscopy (MMS)

Purpose: To detect subtle, stress-induced changes in protein secondary structure (alpha-helix, beta-sheet) that may indicate instability.

Principle: MMS measures the infrared absorption spectrum of a protein, which is sensitive to its secondary structure. It compares the sample spectrum to a control and highlights differences, making it highly sensitive to conformational changes [10].

Procedure:

- Stress Application: Subject your protein sample to the stress of interest (e.g., incubate at 50°C overnight, agitate, or expose to different pH buffers).

- Control Sample: Keep an aliquot of the protein under non-stressful conditions as a control.

- Spectra Acquisition: Analyze both the stressed and control samples using an MMS instrument.

- Data Interpretation: The instrument generates a delta plot by subtracting the second derivative spectrum of the control from the stressed sample. A loss of alpha-helix or beta-sheet signals, or the formation of intermolecular beta-sheet (associated with aggregation), indicates stability loss. The technique can also demonstrate the stabilizing effect of ligands or excipients by showing reduced structural change after stress [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function in Stability Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Denaturants | To progressively unfold the protein in a controlled manner to study stability and folding pathways [12]. | Determining the free energy of unfolding (ΔG) by urea or GdnHCl titration [12]. |

| Stabilizing Excipients | To protect the native protein structure from various stressors in formulation buffers [10]. | Adding polysorbate 80 to prevent surface-induced aggregation of a monoclonal antibody [10]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Tween 80) | To stabilize proteins at interfaces (e.g., air-water, ice-water) by competing for the surface, preventing protein unfolding [8]. | Added to protein formulations to prevent denaturation at air-liquid interfaces during shaking [8]. |

| Immobilization Carriers | To provide a solid support for covalent or non-covalent enzyme attachment, rigidifying structure and enabling reuse [13]. | Covalently binding an enzyme to chitosan beads to enhance its thermal and pH stability for industrial catalysis [13]. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | To create covalent bonds within or between protein molecules, increasing rigidity and stability [13]. | Used in enzyme immobilization protocols to form stable, cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) [13]. |

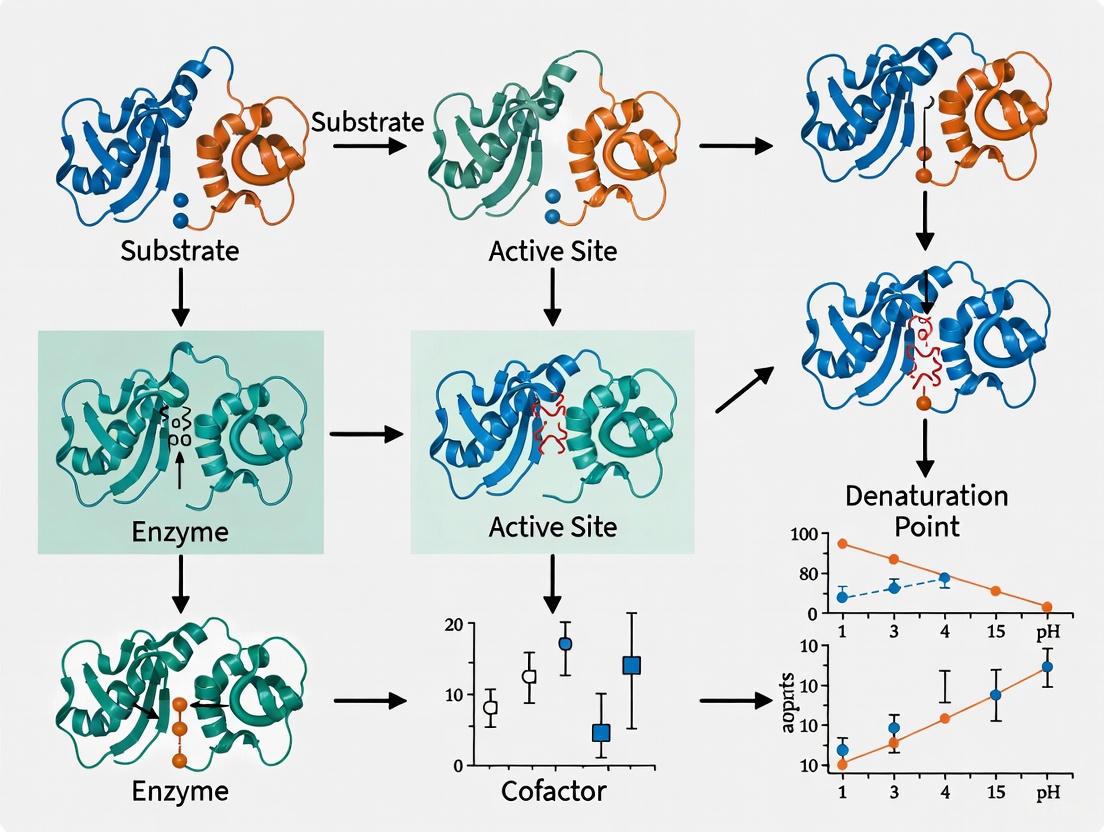

Protein Denaturation and Stabilization Pathways

Troubleshooting Guide: Active Site Stability

Problem 1: How does mutation of a single amino acid near the catalytic triad lead to activity loss?

Issue: A glycine residue adjacent to the catalytic histidine was mutated to an asparagine (G282N) to promote hydrogen bond formation. The mutant enzyme showed a significant drop in activity, especially at sub-optimal temperatures [14].

Root Cause: The mutation restricts the necessary flexibility of the catalytic "His-loop." The wild-type enzyme uses a glycine at this position to allow for dynamic loop movement essential for catalysis. Introducing a bulkier side chain (asparagine) forms a new hydrogen bond that locks the loop in a less flexible conformation, impeding the conformational changes needed for efficient substrate turnover [14].

Solutions:

- Revert to Glycine: Switch back to the wild-type glycine residue to restore loop flexibility.

- Engineer Compensatory Flexibility: If the mutation is essential for another property, consider introducing flexibility at another nearby, non-critical loop region to compensate for the rigidity introduced by the mutation.

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: Perform the reaction at the enzyme's optimal temperature, as the deleterious effect of rigidity is often more pronounced at lower temperatures [14].

Problem 2: Why does my enzyme lose activity after incubation at elevated (but sub-optimal) temperatures?

Issue: An EstE1 G282N mutant gradually lost residual activity when pre-incubated at 50–60°C, retaining only 25% activity at 70°C, while the wild-type remained stable [14].

Root Cause: The mutation compromises active-site stability. The new hydrogen bond that restricts flexibility also makes the active site more vulnerable to thermal denaturation. The local rigidity may prevent the enzyme from absorbing thermal energy through harmless conformational dynamics, leading to irreversible unfolding or distortion of the catalytic geometry [14].

Solutions:

- Screen Stabilizing Excipients: Add stabilizers like sugars (sucrose, trehalose) or certain amino acids (e.g., arginine) to the formulation. These can create a protective hydration shell and prevent aggregation during thermal stress [15].

- Consider Immobilization: Covalently immobilize the enzyme on a solid support. This can increase the enzyme's rigidity and resistance to denaturation by restricting unfolding [13].

Problem 3: What strategies can I use to improve the stability of an enzyme with a flexible, unstable active site?

Issue: A mesophilic enzyme (rPPE) has a globally flexible structure but a locally rigid His-loop stabilized by hydrogen bonding, limiting its activity [14].

Root Cause: The inherent flexibility of the enzyme's scaffold, combined with rigid loops in the active site, creates a sub-optimal balance between stability and activity.

Solutions:

- Enzyme Immobilization: This is a primary technique for stabilizing free enzymes.

- Covalent Binding: Create stable complexes by forming covalent bonds between enzyme functional groups (e.g., from lysine or cysteine) and a carrier matrix. This method prevents enzyme leakage and often improves thermal stability [13].

- Adsorption: Bind the enzyme to a support material (e.g., chitosan, porous silica) via weak forces. This is a simpler, reversible method but can lead to enzyme leakage under shifting pH or ionic strength [13].

- Protein Engineering: Use directed evolution or rational design to introduce stabilizing mutations. Machine learning tools can now predict mutations that enhance stability, solubility, and function without compromising activity [16].

- Chemical Modification: Conjugate the enzyme with chemically modified polysaccharides to enhance its physicochemical characteristics [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can enzyme denaturation be reversed? In some cases of mild denaturation, if the changes in temperature or pH are not too severe or prolonged, the enzyme can refold into its functional shape—a process called renaturation. However, many instances of denaturation, especially those that cause irreversible tangling of the polypeptide chain, are permanent [17].

Q2: Besides temperature, what other factors can denature an enzyme and distort the active site? Deviations from the optimal pH can alter the charge of amino acid residues, disrupting ionic and hydrogen bonds that maintain the enzyme's three-dimensional structure, including the active site. Exposure to organic solvents, certain salts, and mechanical stress (e.g., from pumping or agitation) can also cause denaturation [13] [17] [15].

Q3: How can I experimentally monitor changes in active-site flexibility? Intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy can be used. Tryptophan or tyrosine residues in the active-site wall contribute to the overall fluorescence signal. A temperature-dependent fluorescence decrease can indicate conformational changes. Acrylamide quenching can further probe flexibility; a more rigid mutant will exhibit reduced quenching compared to the flexible wild-type [14].

Q4: We discovered a novel enzyme with great activity but poor stability. Is formulation a viable solution? Yes. A well-designed formulation creates a microenvironment that protects the enzyme's native structure. This involves finding the optimal combination of pH, ionic strength, and stabilizing excipients (e.g., sugars, surfactants, antioxidants) to protect the molecule through storage and delivery. A data-driven approach using high-throughput screening and machine learning can efficiently identify the right stabilizers for a specific enzyme [15].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Key Quantitative Data on His-Loop Mutations

Table 1: Impact of His-loop mutations on esterase activity and stability. WT = Wild-Type. Data adapted from [14].

| Enzyme | Mutation | Residual Activity vs. WT | Key Stability Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EstE1 (Hyperthermophilic) | G282N | 71% (at 70°C), 54% (at 30°C) | Lost ~75% activity after pre-incubation at 70°C |

| EstE1 (Hyperthermophilic) | G282Q | 65% (at 70°C), 32% (at 30°C) | Greater flexibility than WT, but lower stability |

| rPPE (Mesophilic) | D287G | 153% (at 30°C) | Increased flexibility enhanced activity |

| rPPE (Mesophilic) | D287E | 116% (at 30°C) | Stronger hydrogen bond improved stability and affinity |

Protocol 1: Assessing Active-Site Stability via Residual Activity

Purpose: To determine an enzyme's ability to maintain its catalytic function after exposure to stressful conditions.

Methodology:

- Pre-incubation: Aliquot the enzyme solution into small tubes. Incubate each tube at a specific elevated temperature (e.g., from 40°C to 70°C) for a fixed period (e.g., 10-60 minutes).

- Cooling: Immediately place the tubes on ice to stop the thermal denaturation process.

- Activity Assay: Measure the remaining enzymatic activity of each pre-incubated sample under the enzyme's standard optimal assay conditions (e.g., at its optimal temperature and pH, using a specific substrate like p-nitrophenyl esters).

- Calculation: Express the activity of each heat-treated sample as a percentage of the activity of an untreated control sample kept on ice [14].

Protocol 2: Probing Flexibility with Intrinsic Tryptophan Fluorescence

Purpose: To monitor conformational changes and flexibility in the enzyme's structure, particularly near the active site.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a purified enzyme solution in an appropriate buffer.

- Temperature Ramp: Place the sample in a spectrofluorometer equipped with a temperature controller. Gradually increase the temperature from a low (e.g., 4°C) to a high value (e.g., 90°C).

- Fluorescence Measurement: At regular temperature intervals, excite the sample at 295 nm (to selectively excite tryptophan residues) and record the emission spectrum, typically from 300 to 400 nm.

- Data Analysis: Plot the maximum fluorescence intensity versus temperature. A gradual decrease suggests a flexible structure undergoing continuous unfolding, while a sharp drop indicates a cooperative, more rigid unfolding transition [14].

Visualizing the Concepts

Diagram 1: Active Site Flexibility Trade-Off

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Stability Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and methods for studying and mitigating active site geometry loss.

| Research Reagent / Method | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduces targeted point mutations to test the role of specific residues in active-site geometry and flexibility. | Critical for establishing causality between a specific amino acid and observed functional changes. |

| Intrinsic Tryptophan Fluorescence | Probes conformational changes and flexibility in the enzyme's structure, often near the active site. | A non-destructive method that can monitor real-time unfolding. |

| Covalent Immobilization Carriers | Provides a solid support for stable enzyme attachment via covalent bonds, restricting unfolding. | Prevents enzyme leakage but requires careful selection to avoid blocking the active site [13]. |

| Stabilizing Excipients | Protects the enzyme's native structure in solution against various stressors. | Sucrose/Trehalose: Form protective hydration shells.Polysorbates: Shield against interfacial stress.Antioxidants: Prevent chemical degradation [15]. |

| AI/Machine Learning Platforms | Analyzes sequence-structure-function data to predict stabilizing mutations and optimal formulation conditions. | Dramatically accelerates the engineering and formulation process compared to traditional trial-and-error [18] [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center provides solutions for common challenges in enzyme stability research, directly supporting thesis work on overcoming denaturation in harsh conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our enzyme rapidly loses activity in liquid formulation at room temperature. What are our most effective strategies to improve shelf-life?

Liquid enzyme formulations are prone to degradation, but several strategies can significantly enhance stability.

- Add Stabilizing Excipients: Incorporate polyhydric alcohols like glycerol (typically 25-50%) or sugars like sucrose and trehalose. These act as cryoprotectants and stabilizers by forming a protective hydration shell around the enzyme, preventing unfolding and aggregation [19] [20] [21]. Antioxidants (e.g., DTT) and chelating agents (e.g., EDTA) can also be added to prevent chemical instability like oxidation [19] [15].

- Optimize Buffer Conditions: The buffer's pH and ionic strength are critical. Most enzymes are stable only within a specific pH range, and the buffer type itself can sometimes inhibit activity [19]. Extensive screening is required to find the optimal buffer.

- Consider a Solid Formulation: Converting a liquid enzyme to a solid granulate through processes like wet granulation can dramatically improve long-term stability. One study showed that a granulated enzyme was stable for up to 24 months at 30°C, compared to a liquid form which was stable for only 1 day at room temperature after reconstitution [22]. Lyophilization (freeze-drying) is another common method, often facilitated by glycerol-free formulations for better water removal [20].

Q2: How can we stabilize an enzyme for repeated use in an industrial bioreactor?

For reusable industrial biocatalysts, immobilization is the preferred strategy as it enhances stability and allows easy separation from the reaction mixture.

- Covalent Bonding: This technique creates stable complexes by forming covalent bonds between the enzyme's functional groups (e.g., amino groups from lysine) and a solid carrier matrix (e.g., porous silica, agarose). It is highly effective due to strong enzyme/support interaction, which prevents enzyme leakage and often improves thermal stability [23] [13].

- Entrapment: The enzyme is physically trapped within an inert matrix, such as calcium alginate beads or a silk fibroin film. Entrapment in silk films has been shown to allow enzymes to retain significant activity even when stored at 37°C for ten months [23] [24].

- Cross-Linking: Enzyme molecules are cross-linked to each other using linkers like glutaraldehyde to form a stable aggregate. This method, known as Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs), "locks" the enzyme structure and has shown large improvements in stability for industrial biocatalysts [24].

Q3: We need to ship diagnostic enzymes to remote areas without cold chain access. How can we achieve ambient-temperature stability?

Achieving ambient-temperature stability is a key goal in diagnostic and therapeutic development.

- Develop Glycerol-Free Lyophilized Reagents: Glycerol, while good for cold storage, hinders lyophilization. Formulating glycerol-free enzymes with optimized buffers containing specific stabilizers allows for successful lyophilization, creating stable powders that can be shipped and stored at ambient temperature without losing activity [20].

- Use Solid Stabilization Matrices: Embedding enzymes in biocompatible, solid-state protein matrices like silk fibroin can stabilize them without refrigeration. These systems are ingestible, biocompatible, and offer remarkable long-term stability, making them ideal for distribution in challenging environments [24].

Q4: Can we predict and engineer an enzyme to be inherently more stable under high temperature or pressure?

Yes, advanced computational and simulation methods are now used to guide enzyme engineering for enhanced stability.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations under varying temperature and pressure levels can reveal an enzyme's structural adaptability. By analyzing metrics like root mean square deviation (RMSD) and radius of gyration (Rg), researchers can understand how the enzyme's structure fluctuates and denatures under stress [25].

- Conformational Biasing and ProteinMPNN: This computational pipeline uses stable enzyme conformations derived from MD simulations (e.g., from states at 273 K/1 bar and 333 K/4000 bar) to identify mutation sites. The ProteinMPNN neural network model then designs mutant sequences with a bias toward more stable conformations, effectively engineering enzymes for harsh conditions [25].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enzyme Immobilization via Covalent Binding to a Solid Support

This methodology details the covalent immobilization of an enzyme, which improves reusability and resistance to temperature and pH changes [13].

- Principle: Create stable covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme (e.g., amino groups from Lysine) and an activated carrier matrix.

- Materials:

- Purified enzyme

- Carrier matrix (e.g., porous silica, agarose, chitin/chitosan)

- Coupling agent (e.g., Glutaraldehyde or Carbodiimide)

- Appropriate buffer solutions

- Procedure:

- Activate the Carrier: Incubate the carrier matrix with a coupling agent like glutaraldehyde to create an electrophilic group on its surface.

- Couple the Enzyme: Mix the activated carrier with the enzyme solution in a suitable buffer. The nucleophilic groups on the enzyme (e.g., amino groups) will covalently bind to the activated support.

- Incubate: Allow the reaction to proceed for several hours to ensure complete binding and formation of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM).

- Wash: Thoroughly wash the immobilized enzyme preparation to remove any unbound enzyme or reagents.

- Troubleshooting Tip: A loss of activity after immobilization may indicate that the covalent binding involved amino acid residues critical for the enzyme's catalytic function. Testing different coupling chemistries or carrier materials may be necessary [13].

Protocol 2: Assessing Stability via Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

This protocol describes a computational method to study enzyme stability under harsh conditions like high temperature and pressure, providing a theoretical foundation for experimental engineering [25].

- Principle: Use MD simulations to model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time under defined environmental stresses to analyze structural changes.

- Materials:

- Enzyme 3D structure (e.g., from AlphaFold3 or crystal structure)

- MD simulation software (e.g., GROMACS)

- High-performance computing cluster

- Procedure:

- System Setup: Place the enzyme structure in a simulation box with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP4P model). Add ions to neutralize the system's charge.

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization using a method like steepest descent to relieve any steric clashes.

- Set Conditions: Define the simulation parameters, including a range of temperatures (e.g., 273 K to 333 K) and pressures (e.g., 1 bar to 4000 bar).

- Run Simulation: Perform multiple independent MD simulation replicates for each temperature-pressure condition (e.g., 60 ns each).

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate key structural metrics from the simulation data:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures overall structural stability.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions.

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Assesses protein compactness.

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Monitors unfolding.

The workflow for this computational protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Quantitative Data on Enzyme Stabilization Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Enzyme Formulation Strategies for Shelf-Life Extension

| Strategy | Key Components | Storage Condition | Stability Outcome | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Formulation (with stabilizers) [19] [21] | Glycerol (25-50%), Sucrose/Trehalose, Antioxidants | 0°C to 4°C, sometimes -20°C with glycerol | Varies; gradual activity loss over weeks/months | Convenient for ready-to-use solutions |

| Solid Granulate [22] | Enzyme, Excipients (e.g., Citrate), processed via wet granulation | 30°C | Stable for 24 months; 3 days after reconstitution | Dramatically improved ambient-temperature shelf-life |

| Silk Fibroin Entrapment [24] | Silk protein matrix, Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase) | 37°C | Retained >90% activity after 10 months | Biocompatible and stable under physiological conditions |

| Lyophilized (Glycerol-Free) [20] | Optimized salts, PCR enhancers, stabilizers | Ambient temperature | Maintains stability and performance post-lyophilization | Eliminates cold chain for shipping and storage |

Table 2: Structural Metrics from Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Stability Analysis [25]

| Simulation Condition | Impact on RMSD (Overall Stability) | Impact on Rg (Compactness) | Impact on SASA (Solvent Exposure) | Molecular Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing Temperature | Increase | Increase | Increase | Elevated molecular entropy leads to unfolding and loss of structure. |

| Increasing Pressure | Decrease (at moderate levels) | Decrease | Decrease | Collapse of internal cavities and organized molecular order, leading to tighter packing. |

| Coupled High Temp. & Pressure | Varies, can be stabilizing | Varies, can be compacting | Varies | Pressure can counteract some denaturing effects of heat, revealing structural adaptability. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Enzyme Stabilization Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research & Development |

|---|---|

| Glycerol [19] [21] | A cryoprotectant and stabilizer; prevents ice crystal formation and protein aggregation in cold storage. |

| Silk Fibroin [24] | A biocompatible protein matrix for enzyme entrapment; provides a stabilizing microenvironment for long-term activity. |

| Glutaraldehyde [13] | A cross-linking agent; used for covalent enzyme immobilization on supports and creating Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs). |

| Chitosan / Alginate [23] [13] | Natural polymer supports for enzyme immobilization via adsorption or covalent binding; cost-effective and biodegradable. |

| Trehalose / Sucrose [15] | Stabilizing excipients that form a protective hydration shell around enzymes, used in both liquid and lyophilized formulations. |

| Polysorbate Surfactants [15] | Protect enzymes from interfacial and mechanical stress (e.g., from agitation) by occupying air-liquid interfaces. |

Engineering Resilience: AI, Additives, and Advanced Strategies for Enzyme Stabilization

Core Concepts: Machine Learning for Enzyme Stability

How can Machine Learning help overcome enzyme denaturation in harsh industrial conditions? Machine Learning (ML) guides enzyme engineering by rapidly predicting sequence modifications that enhance stability, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods. ML models learn from vast datasets of sequence-function relationships to map fitness landscapes and identify mutations that improve structural robustness against stressors like extreme pH, temperature, and solvents [26] [27]. This data-driven approach is particularly effective for designing stabilized enzymes for bioreactors and drug development, where maintaining activity in demanding environments is critical [15] [28].

What are the primary ML strategies for designing stable enzymes? ML integration in enzyme engineering has evolved through multiple stages, each contributing to stability prediction:

- Classical Machine Learning: Uses algorithms like ridge regression with handcrafted features to predict stability from sequence data [26].

- Deep Neural Networks (DNNs): Model complex, non-linear relationships in protein sequences for more accurate stability predictions [27].

- Protein Language Models (pLMs): Leverage evolutionary information from protein sequences to make zero-shot stability predictions without explicit experimental data [26] [27].

- Multimodal Models: Integrate diverse data types, such as sequence, structure, and functional assays, for a holistic and generalizable stability assessment [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering Workflow

| Problem Area | Specific Problem | Possible Cause | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Generation & Quality | Limited sequence-function data for model training. | Low-throughput screening methods; high cost of experimental characterization. | Adopt high-throughput cell-free gene expression (CFE) systems to rapidly generate large fitness datasets [26]. |

| Model Performance & Prediction | ML model fails to predict variants with improved stability. | Insufficient or low-quality training data; model cannot generalize to new sequence space. | Augment models with evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictors; use ensemble methods combining multiple algorithms [26] [27]. |

| Experimental Validation | Predicted stable enzymes perform poorly in real-world bioreactors. | Model trained on idealized lab conditions; neglects process stresses like shear forces or interfaces. | Include stability data from industrial-relevant conditions (e.g., presence of solvents, high concentration) in training sets [15] [28]. |

| Stability in Application | Enzyme loses activity upon immobilization or in final formulation. | Stabilizing mutations may block key functional sites or alter surface charges crucial for immobilization. | Employ multimodal ML models that simultaneously optimize for stability, activity, and surface properties for downstream application [27] [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ML-Guided Engineering of a Thermostable Amide Synthetase

This protocol is adapted from a study that engineered amide synthetases using an ML-guided, cell-free platform [26].

1. Objective: Improve enzyme activity and stability under industrial-relevant conditions for pharmaceutical synthesis.

2. Methods:

- Data Generation (Build):

- Library Construction: Use cell-free DNA assembly and PCR-based site-saturation mutagenesis to generate a library of 1,216 single-point mutants targeting 64 residues enclosing the active site and substrate tunnels [26].

- High-Throughput Screening (Test): Express mutant enzymes using cell-free gene expression (CFE). Perform functional assays with target substrates under conditions of high substrate concentration and low enzyme loading to simulate industrial stress. Collect conversion data as a fitness score [26].

- Machine Learning (Learn):

- Model Training: Use the sequence-function data (1,217 variants tested in 10,953 reactions) to train supervised ridge regression models.

- Model Augmentation: Augment the model with an evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictor to improve extrapolation.

- Variant Prediction: Use the trained ML model to predict higher-order mutants with increased activity and stability [26].

- Validation:

- Synthesize and test the top ML-predicted variants. Reported results showed variants with 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity relative to the parent enzyme for synthesizing nine pharmaceutical compounds [26].

Protocol 2: Enzyme Stabilization via Surface Immobilization

Immobilization is a key method to combat denaturation, and ML can help select optimal enzyme-support pairs [28] [29].

1. Objective: Enhance enzyme stability and reusability by covalent immobilization on a solid support.

2. Methods:

- Support Activation:

- Activate the carrier surface (e.g., porous silica, chitosan) with a linker molecule like glutaraldehyde. This creates an electrophilic group on the carrier [29].

- Enzyme Coupling:

- Incubate the enzyme with the activated carrier. Covalent bonds form between the carrier's electrophilic groups and nucleophilic amino acid residues on the enzyme (e.g., lysine's amino group). This creates a stable, multi-point attachment [29].

- Analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering |

|---|---|

| Cell-free Gene Expression (CFE) System | Enables rapid, high-throughput synthesis and testing of thousands of enzyme variants without cloning, accelerating data generation for ML models [26]. |

| Ridge Regression ML Model | A supervised learning algorithm used to predict enzyme fitness from sequence data, helping to navigate the protein fitness landscape and identify stabilizing mutations [26]. |

| Augmented ML Model (e.g., with zero-shot predictor) | Enhances predictive power by combining experimentally derived sequence-function data with evolutionary information from related protein sequences [26]. |

| Covalent Immobilization Support (e.g., Chitosan, Porous Silica) | Provides a solid matrix for enzyme attachment, restricting molecular movement and enhancing stability against denaturation from heat, pH, and solvents [29]. |

| Linker Molecules (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Acts as a cross-linking agent to form stable, covalent bonds between the enzyme and the support material during immobilization [29]. |

Comparison of Enzyme Stabilization Techniques

When designing your enzyme stabilization strategy, the choice of method depends on your application requirements. The table below compares common techniques.

| Stabilization Method | Key Mechanism | Relative Cost | Stability Improvement | Reusability | Best For Applications Requiring: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Guided Protein Engineering | Altering amino acid sequence to improve intrinsic stability [26] [27]. | High (R&D) | High (tailored) | N/A (inherent) | Permanent, intrinsic stability without supports. |

| Covalent Immobilization | Forming strong covalent bonds between enzyme and solid support [29]. | Medium | High | Excellent | Continuous flow reactors, multiple reuses without enzyme leakage [28]. |

| Adsorption Immobilization | Binding via weak forces (ionic, hydrophobic) [29]. | Low | Low to Medium | Poor | Low-cost, one-off use where some enzyme loss is acceptable. |

| Chemical Modification | Modifying surface residues with soluble polymers (e.g., polysaccharides) [29]. | Medium | Medium | N/A | Improved solubility and stability in liquid formulations. |

Workflow Visualization

ML-Guided Engineering Workflow

Enzyme Stabilization via Immobilization

Enzyme thermostability—the ability to retain structure and function at high temperatures—is a critical property for industrial and research applications, from pharmaceutical synthesis to biofuel production. Overcoming enzyme denaturation in harsh conditions is a central challenge in biocatalysis. Traditional methods like directed evolution are often costly, time-consuming, and labor-intensive [30] [31]. The emergence of a data-driven research paradigm, powered by machine learning (ML) and large-scale biological databases, is revolutionizing this field. This approach leverages vast, curated datasets to build predictive models that guide rational enzyme design, significantly accelerating the engineering of robust biocatalysts [30]. This technical support center is designed to empower researchers in navigating this new landscape, providing practical guidance on utilizing key resources like BRENDA and ThermoMutDB to overcome the persistent problem of enzyme denaturation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary data resources for enzyme thermostability engineering, and how do I choose between them? Your choice of database depends on the specific data type required for your project. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of major resources.

Table 1: Key Databases for Enzyme Thermostability Research

| Database Name | Primary Data Type | Scale | Key Features & Advantages | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRENDA [30] [31] | Enzyme function & properties (e.g., optimal temperature) | >32 million sequences; ~41,000 optimal temp. labels [30] | Manually curated from literature; wide enzyme coverage; actively maintained. | Finding wild-type enzyme properties and temperature activity profiles. |

| ThermoMutDB [30] [32] | Mutant thermodynamic data (e.g., ΔTm, ΔΔG) | ~14,669 mutations across 588 proteins [30] | Manually curated; flexible search/API; focuses on mutation effects. | Analyzing the stabilizing/destabilizing effects of specific point mutations. |

| AlphaFold DB [33] | Predicted 3D protein structures | Over 200 million entries [33] | Open access; high accuracy; broad coverage of UniProt. | Generating structural models for rational design when experimental structures are unavailable. |

| ProThermDB [30] | Mutant thermal stability data | >32,000 proteins; ~120,000 data points [30] | Extensive, high-quality experimental data; continuously updated. | Accessing a large volume of experimentally derived thermal stability parameters. |

Q2: My dataset is small and imbalanced, with few examples of thermostable enzymes. How can I train an effective machine learning model? Data scarcity and imbalance, where enzymes with mid-range temperatures are over-represented, are common challenges [31]. To address this:

- Use Specialized Datasets: Leverage recently developed, pre-curated datasets designed for thermal stability modeling, which implement clustering strategies to minimize sequence similarity between training and test sets, thus improving generalizability [31].

- Apply Weighted Loss Functions: During model training, use a weighted Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) loss function. This technique assigns higher importance to underrepresented samples (e.g., hyper-thermostable enzymes), forcing the model to learn these patterns more effectively [31].

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Start with a model pre-trained on a large, general protein sequence database (like UniProt) and fine-tune it on your smaller, specific thermostability dataset. This allows the model to learn fundamental protein principles before specializing.

Q3: How can I predict thermostability for an enzyme when the optimal growth temperature (OGT) of its source organism is unknown? Earlier models relied heavily on OGT, limiting their applicability [31]. Newer, state-of-the-art models like the Segment Transformer are OGT-independent. They predict temperature stability directly from the amino acid sequence by learning segment-level features that contribute unequally to thermal behavior, achieving high accuracy without organism-specific metadata [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Interpreting and Validating Computational Predictions

Problem: Predictions from a machine learning model for a newly designed enzyme variant do not align with initial experimental results. Solution: Follow this systematic workflow to diagnose and resolve the discrepancy.

Steps:

- Check Input Data Quality:

- Sequence Verification: Ensure the input amino acid sequence for prediction is accurate and free of errors. A single misplaced residue can significantly alter the predicted structure and stability.

- Database Context: Cross-reference your enzyme's sequence and properties (e.g., from BRENDA) to ensure it falls within the model's trained scope. Performance may degrade for highly novel enzymes distant from the training data.

Assess Model Limitations:

- Understand the Training Data: Recognize that models trained on databases like BRENDA may be biased towards mesophilic enzymes, as data for extreme thermophiles is underrepresented [31]. A predicted stability of 70°C might have a higher error margin than one at 50°C.

- Use Uncertainty Estimates: If the model provides confidence intervals (e.g., the Segment Transformer outputs fluctuation ranges [31]), treat the prediction as a guide rather than an absolute value. A wide range suggests lower reliability.

Validate Experimental Conditions:

- Protocol Consistency: Ensure your experimental protocol for measuring stability (e.g., melting temperature (T_m)) matches the assumptions underlying the data in resources like ThermoMutDB (e.g., buffer pH, ionic strength). Inconsistent conditions are a major source of apparent disagreement [30].

- Replicate Experiments: Perform multiple experimental replicates to confirm the initial result and rule out technical errors.

Iterate and Re-design:

- Use the initial experimental data as a new data point to refine your understanding. Even a "failed" prediction provides valuable information about the model's performance for your specific enzyme family, guiding future design cycles.

Guide: Designing a Thermostability Engineering Workflow

Problem: My team wants to initiate a thermostability engineering project but needs a standardized, effective workflow. Solution: Implement a synergistic data-driven pipeline that integrates computational prediction with experimental validation.

Steps:

- Define Goal and Select Parent Enzyme: Clearly define the target temperature stability and select a parent enzyme with the desired catalytic activity.

- Data Mining and Analysis:

- Mine BRENDA for homologous enzymes to understand natural sequence and stability variation.

- Query ThermoMutDB to identify point mutations (e.g., ΔTm, ΔΔG values) known to stabilize similar protein folds.

- Obtain a 3D Structure from the AlphaFold Database to visualize and guide rational design.

- Run ML Models like the Segment Transformer to get initial stability predictions and identify potential stability "hotspots" [31].

- Generate Variant Library: Synthesize a library of enzyme variants based on the computational predictions, prioritizing mutations with high predicted stability scores and avoiding the enzyme's active site.

- High-Throughput Experimental Testing: Express and purify the variants, then test them using high-throughput assays for activity and thermal stability (e.g., melting temperature (T_m) assays, residual activity after heat shock).

- Model Refinement and Next Cycle: Feed the experimental results back into the machine learning model as new training data. This improves the model's accuracy for your specific enzyme, creating a virtuous cycle of design, test, and learn.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Data-Driven Thermostability Engineering

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database [30] | Data Resource | Provides reference data on wild-type enzyme temperature optima and stability for benchmarking and homolog analysis. |

| ThermoMutDB [32] | Data Resource | Offers a curated list of characterized point mutations and their thermodynamic impact (ΔTm, ΔΔG) to inform rational design. |

| AlphaFold DB [33] | Structural Resource | Supplies accurate 3D protein structure predictions for visualizing mutations, analyzing folds, and conducting in silico analysis. |

| Segment Transformer Model [31] | Software Model | A deep learning tool that predicts enzyme temperature stability directly from sequence, enabling rapid in silico screening of designs. |

| MMseqs2 [31] | Software Tool | Used for sensitive sequence clustering and searching; crucial for creating non-redundant training and test sets to avoid data bias. |

| Thermal Shift Assay (e.g., T_m) | Experimental Assay | A standard high-throughput method to measure protein melting temperature, providing a key experimental validation metric (ΔTm). |

| Residual Activity Assay | Experimental Assay | Measures the percentage of enzymatic activity remaining after exposure to a high temperature, indicating operational stability. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary function of DTT in enzyme stabilization? Dithiothreitol (DTT) is a potent reducing agent that protects enzymes by reducing disulfide bonds and preventing the formation of incorrect intermolecular disulfide bridges that can lead to aggregation and inactivation. Its main role is to maintain cysteine residues in their reduced (-SH) state, which is crucial for the catalytic activity of many enzymes. Once oxidized, DTT forms a stable six-membered ring, which drives the reduction reaction forward and prevents the reformation of disulfide bonds [34] [35].

2. How does cysteine act as a stabilizing agent? Cysteine can function as a stabilizing additive through its thiol group, which serves as an antioxidant. It helps control reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can cause oxidative stress and damage to enzymes. By scavenging ROS, cysteine prevents the oxidation of sensitive amino acid residues in the enzyme's active site, thereby preserving its native structure and function [36]. Furthermore, its thiol group can participate in redox reactions, helping to maintain a reducing environment in the solution [37].

3. What is the protective mechanism of phosphocholine? Phosphocholine, a phospholipid, contributes to enzyme stabilization by mimicking the native membrane environment for membrane-associated enzymes. Many enzymes, such as cytochromes P450, are embedded in lipid membranes. In vitro, phosphocholine helps preserve the structural integrity and catalytic activity of such enzymes by maintaining the hydrophobic and phospholipid interactions necessary for their correct folding and oligomerization [36].

4. When should I choose DTT over other reducing agents like TCEP? DTT is highly effective at pH values above 7, but its reducing power diminishes in acidic conditions. In contrast, Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) is more stable and effective over a broader pH range, including acidic conditions. However, TCEP is a bulkier molecule and may reduce disulfide bonds in folded proteins more slowly than DTT. Choose DTT for standard, pH-neutral conditions and TCEP when working under acidic conditions or when a more stable, odorless alternative is needed [34] [35].

5. Why is my enzyme still losing activity despite adding DTT? A common reason is the oxidation of DTT in solution. DTT is susceptible to air oxidation, and its half-life can be as short as 1.4 hours at pH 8.5 and 20°C. To ensure efficacy, always prepare fresh DTT solutions and store the powder in a desiccated environment at -20°C. The inclusion of EDTA in the solution can chelate divalent metal ions and considerably extend DTT's half-life [35]. Furthermore, note that DTT cannot reduce buried (solvent-inaccessible) disulfide bonds; for these, denaturing conditions may be required prior to reduction [35].

6. Can these additives be used together? Yes, these additives are often used in combination in complex stabilization cocktails. Research focused on stabilizing cytochrome P450 enzymes screened various classes of additives—including sugars, salts, amino acids, phospholipids, and antioxidants—simultaneously. The key is to test different combinations and concentrations, as synergistic effects are possible, but incompatibilities must also be ruled out [36].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid loss of enzyme activity | Additives have oxidized or degraded.Incorrect storage conditions. | Prepare fresh DTT and cysteine solutions daily [35]. Store stock solutions in aliquots at -20°C under inert gas [34]. |

| Enzyme precipitation or aggregation | Lack of reducing agent leading to disulfide bond formation.Incorrect ionic strength. | Increase DTT concentration (e.g., 1-5 mM) [34]. Desalt the enzyme preparation to remove contaminants [38]. |

| Poor enzyme kinetics in assays | Stabilizing additives interfering with the reaction.Mass transfer limitations. | Include control experiments without the substrate to identify inhibition [36]. Dilute the enzyme-additive mix to minimize interference. |

| Inconsistent results between batches | Variable oxidation state of additives.Enzyme sensitivity to minor buffer changes. | Standardize buffer preparation and use high-purity reagents. Confirm the pH of all solutions, as DTT's efficacy is pH-dependent [35]. |

Stabilizing Additives at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key properties and applications of DTT, cysteine, and phosphocholine for easy comparison.

| Additive | Core Function | Typical Working Concentration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTT | Reduces and prevents disulfide bond formation [34] [35]. | 1 - 10 mM | Unstable in solution; prepare fresh. Ineffective at low pH [35]. |

| Cysteine | Antioxidant; scavenges ROS [36]. | Concentration data not available in search results | Can form mixed disulfides; its effectiveness is concentration and context-dependent [37]. |

| Phospholipids (e.g., Phosphocholine) | Mimics native membrane environment; stabilizes structure [36]. | Concentration data not available in search results | Critical for membrane-bound enzymes (e.g., CYPs); may form micelles at high concentrations [36]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Enzyme Stabilization |

|---|---|

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Potent reducing agent to keep cysteines reduced and prevent aggregation [34]. |

| L-Cysteine | Acts as an antioxidant to mitigate oxidative damage from reactive oxygen species (ROS) [36]. |

| Phospholipids | Provides a lipid bilayer-like environment to maintain the structure of membrane-associated enzymes [36]. |

| Trehalose | Stabilizes protein structure through preferential exclusion and water replacement mechanisms [36]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Prevents surface adsorption and stabilizes enzymes by hydrophobic interactions [36]. |

| EDTA | Chelates metal ions to prevent metal-catalyzed oxidation and extends the half-life of DTT [35]. |

| Glycerol | Acts as a kosmotropic agent to reduce molecular mobility and stabilize the hydrated structure of enzymes [39]. |

Experimental Workflow for Testing Stabilizing Additives

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for systematically testing and optimizing stabilizing additives for an enzyme.

Enzyme Stabilization Workflow

Mechanism of DTT in Reducing Disulfide Bonds

This diagram details the step-by-step chemical mechanism by which DTT reduces a protein's disulfide bond.

DTT Reduction Mechanism

Cell-Free Platforms and High-Throughput Screening for Rapid Biocatalyst Development

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues in Cell-Free Biocatalyst Development

Problem: Low or No Protein Yield in Cell-Free Expression

- Potential Cause 1: Suboptimal DNA Template. The DNA template may be impure, have low concentration, or contain sequence errors.

- Solution: Ensure the DNA template is pure and not contaminated with salts, ethanol, or RNases. Verify the sequence, including the presence of an ATG initiation codon and correct reading frame. Avoid gel purification methods that can inhibit the reaction [40].

- Potential Cause 2: Inefficient Reaction Conditions. The reaction may be operating at a non-optimal temperature or with insufficient feeding.

- Solution: For larger proteins, reduce the incubation temperature to 25–30°C to aid proper folding. Use a thermomixer or incubator with shaking. Instead of a single feed, perform multiple feeding steps with smaller volumes of feed buffer (e.g., every 30-45 minutes) to sustain the reaction [40].

- Potential Cause 3: Protein Misfolding or Lack of Cofactors.

- Solution: Add mild detergents (e.g., up to 0.05% Triton-X-100) or molecular chaperones to the reaction to improve folding. If the enzyme requires co-factors for activity or stability, add them directly to the protein synthesis reaction [40].

Problem: High Variability and False Results in High-Throughput Screening (HTS)

- Potential Cause 1: Manual Process Variability. Inter- and intra-user variability during liquid handling can lead to inconsistent reagent volumes and concentrations.

- Solution: Implement automated liquid handling systems to standardize workflows. Technologies with in-built verification, such as droplet detection, can confirm dispensed volumes and enhance reproducibility [41].

- Potential Cause 2: Sample Interference in Cell-Free Systems. The lack of a physical cell membrane means system components are more exposed to interference from complex sample matrices.

- Solution: Incorporate design strategies that reduce interference. This can include using mathematical simulations to optimize assay kinetics or engineering two-filter systems to improve specificity [42].

- Potential Cause 3: Data Handling Challenges. The vast volume of multiparametric data generated by HTS can be difficult to manage and analyze consistently.

- Solution: Utilize automated data management and analytics platforms to streamline analysis, enable rapid insights, and ensure hit compounds are accurately identified [41].

Problem: Enzyme Instability and Denaturation in Harsh Conditions

- Potential Cause 1: Dehydration in Organic Solvents. In water-co-solvent mixtures, organic solvents displace essential water molecules from the enzyme's hydration shell, leading to denaturation.

- Solution: Enhance the enzyme's hydration shell by covalent modification with polar or charged groups (e.g., using pyromellitic anhydride). This increases the enzyme's affinity for water, retarding dehydration-driven denaturation [2].

- Solution: Use immobilization techniques. Multi-point covalent attachment to a support or formation of complexes with polyelectrolytes can increase the conformational rigidity of the enzyme, making it more stable in the presence of organic solvents [2].

- Potential Cause 2: Thermal Degradation. At high temperatures, enzymes can undergo irreversible inactivation through processes like deamidation of asparagine and glutamine or succinimide formation at aspartate and glutamate residues.

- Solution: While this is inherent to the enzyme's structure, one stabilization strategy is "nanoarmoring." Wrapping the enzyme with a synthetic polymer (e.g., polyacrylic acid) reduces the conformational entropy of the denatured state, effectively raising the free energy required for unfolding and stabilizing the native state [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using cell-free platforms over traditional cell-based methods for biocatalyst screening? Cell-free systems offer several distinct advantages: they provide high biosafety as no live cells are involved, enable fast material transport without membrane barriers for quicker reactions, and permit direct control over the reaction environment. This allows for high sensitivity and the ability to screen conditions that would be toxic to cells [42].

Q2: How can I improve the portability and shelf-life of my cell-free biosensor? Freeze-drying technology is a key strategy. You can lyophilize the cell-free transcription-translation system onto substrates like paper, creating stable, ready-to-use tests that can be activated simply by adding water. These freeze-dried systems have been shown to remain stable at room temperature for months [42].

Q3: Our AI-driven enzyme discovery is successful in silico, but the enzymes perform poorly in the lab. What is the most likely cause? This is a common bottleneck. AI predicts structure and function, but it may not fully account for critical real-world factors like enzyme production yield, solubility, cofactor requirements, or stability under actual process conditions (e.g., in the presence of solvents or at elevated temperatures). Bridging this gap requires integrated wet-lab testing with rapid feedback loops to characterize and optimize the computationally designed enzymes [43].

Q4: What are some practical methods to stabilize enzymes in organic solvents? Beyond the methods in the troubleshooting guide, you can:

- Use protein engineering: Introduce mutations that increase rigidity or metal-chelating histidine residues to create stabilizing internal coordination bonds [2].

- Form complexes with oligoamines: Compounds like spermine can electrostatically bind to enzymes, providing additional stabilization under harsh conditions [2].

- Choose solvents wisely: Hydrophilic solvents like glycerol and ethylene glycol have a much lower denaturing capacity than hydrophobic solvents like tetrahydrofuran (THF) or butanol [2].

Q5: How can automation specifically address challenges in HTS for biocatalyst development? Automation directly tackles the core issues of reproducibility and data quality. It minimizes human error and variability in liquid handling, which is crucial for reliable results. Furthermore, automation enables miniaturization, drastically reducing reagent consumption and costs by up to 90%, while increasing throughput by allowing large libraries to be screened at multiple concentrations [41].

Performance Data and Stabilization Strategies

The tables below summarize quantitative data and methodological details to aid in experimental planning and problem-solving.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Cell-Free Biosensors This table provides examples of detection capabilities for various targets using cell-free systems, illustrating their sensitivity and versatility [42].

| Target Substance | Limit of Detection / Range | Response Time | Output Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzoic Acid | 10 µM | ~1 hour | sfGFP |

| 12 Amino Acids | 0.1–1 µM | 1 hour | sfGFP |

| Theophylline | 1 mM | <90 minutes | lacZ |

| Zika Virus RNA | 2 aM | 2.5 hours | lacZ |

| Mercury | 6 µg/L | ~1 hour | sfGFP |

| Tetracycline | 10–10,000 ng/mL | <90 minutes | Luciferase |

| Arsenic | 0.5 µM | 2 hours | XylE |

Table 2: Comparison of Enzyme Stabilization Techniques Against Denaturation A summary of common strategies to combat enzyme denaturation, particularly in non-ideal environments [2].

| Stabilization Method | Mechanism of Action | Example Application / Result |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Immobilization | Multi-point attachment to a support increases conformational rigidity. | Chymotrypsin on polyacrylamide remained active at 60% methanol, 20% higher than native enzyme. |

| Polyelectrolyte Complexation | Multiple electrostatic interactions protect the enzyme from denaturation. | Chymotrypsin-polyanion complex enabled peptide synthesis in 60% DMF. |

| Surface Modification | Introduces groups that strongly bind water, retarding dehydration. | Pyromellitic anhydride-modified chymotrypsin retained activity in broader ethanol range. |

| Nanoarmoring | Synthetic polymer wrapping reduces conformational entropy of denatured state. | Polyacrylic acid wrapping stabilizes the native enzyme state via "entropy control". |

| Metal Chelation | Introduced residues create internal coordination bonds for rigidity. | Enzymes with engineered metal-chelating histidines showed higher stability in organic solvents. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Stabilizing an Enzyme via Polyelectrolyte Complexation for Use in Organic Solvents

This protocol describes a method to form a non-covalent complex between an enzyme and a polyelectrolyte to enhance its stability in water-organic solvent mixtures [2].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a low-salt aqueous buffer (e.g., 1-5 mM) at a pH where your enzyme is charged. For a negatively charged enzyme, use a pH above its isoelectric point (pI).

- Complex Formation: Add the polycation (e.g., polybrene) to the enzyme solution under gentle stirring. The amount of polyelectrolyte required must be determined empirically, but is typically based on charge ratios.

- Incubation: Allow the mixture to incubate for 30-60 minutes at 4°C to form the complex.

- Application: The enzyme-polyelectrolyte complex can be used directly in the water-organic solvent mixture. The complex is stable in low-dielectric media but can be dissociated by adding high concentrations of salt if needed.

Protocol 2: Miniaturized HTS using Automated Liquid Handling

This protocol outlines a general workflow for a high-throughput screening assay in a microplate format, emphasizing automation to minimize variability [41].

- Assay Design: Define the experimental parameters, including compound concentrations, controls, and replication scheme.

- Plate Reformatting: Use an automated liquid handler to transfer compounds from a library stock plate into the assay microplate. Non-contact dispensers are preferred to avoid cross-contamination.

- Reagent Dispensing: Dispense the cell-free reaction mix or buffer containing the target and detection reagents into all wells of the assay plate. Automated systems with drop-detection technology can verify dispensed volumes.

- Initiation: If required, use the dispenser to add a substrate to initiate the enzymatic reaction.

- Incubation and Reading: Incubate the plate at the designated temperature and time, then read the output signal (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) using a plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Automatically stream the raw data to an analysis platform for normalization, hit identification, and quality control checks.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

HTS Automation Workflow

Enzyme Denaturation and Stabilization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cell-Free and HTS Biocatalyst Development

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Pure, Linear DNA Template | Directly used in cell-free protein synthesis reactions to program the production of the target biocatalyst. Must be free of contaminants like salts and RNases [40]. |

| Cell-Free Transcription-Translation Kit | A pre-mixed system containing all essential cellular components (ribosomes, tRNAs, enzymes, nucleotides) for protein synthesis in vitro. Examples include Expressway or similar systems [40]. |

| MembraneMax Reagent | A proprietary scaffold used in cell-free systems to facilitate the proper folding and integration of membrane proteins, which are often difficult to express functionally [40]. |

| Polyelectrolytes (e.g., Polybrene) | Used to form reversible complexes with enzymes, providing stabilization against denaturation in organic solvents and other harsh conditions through multi-point electrostatic binding [2]. |

| Non-Contact Liquid Handler | Automated instrument for precise, high-throughput dispensing of nanoliter to microliter volumes of compounds, reagents, and cell-free mixes into microplates, minimizing variability and cross-contamination [41]. |

| Molecular Chaperones | Proteins that can be added to cell-free reactions to assist in the proper folding of the synthesized target enzyme, thereby improving the yield of active biocatalyst [40]. |