Rational Design of Enzyme Enantioselectivity: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions in Biocatalysis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of rational design strategies for engineering enzyme enantioselectivity, a critical property for synthesizing enantiopure pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals.

Rational Design of Enzyme Enantioselectivity: Strategies, Applications, and Future Directions in Biocatalysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of rational design strategies for engineering enzyme enantioselectivity, a critical property for synthesizing enantiopure pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of enzyme engineering, compares rational design with directed evolution, and details key methodologies including multiple sequence alignment, steric hindrance control, and computational protein design. The content further addresses practical challenges, troubleshooting, and optimization techniques, supported by case studies and validation protocols. By synthesizing recent advances, this review serves as a strategic guide for applying rational design to develop highly selective biocatalysts for biomedical and industrial applications.

Understanding Enzyme Enantioselectivity: Core Principles and Industrial Significance

In the realm of drug development, molecular chirality—the property wherein a molecule and its mirror image cannot be superimposed—is a fundamental determinant of therapeutic efficacy and safety. Like a left and right hand, chiral enantiomers share the same chemical structure but differ in their three-dimensional orientation, leading to profoundly different biological interactions. This dichotomy is crucial in pharmaceuticals, where one enantiomer (the eutomer) may provide the desired therapeutic effect, while its mirror image (the distomer) may be inactive or, in notorious cases, cause severe adverse effects [1]. A tragic historical example is thalidomide, where one enantiomer provided the intended sedative effect while the other caused teratogenic effects [2].

The pharmaceutical industry has increasingly recognized these critical differences, with regulatory agencies including the FDA and EMA now requiring detailed characterization of stereochemistry in drug submissions [1]. This has driven significant growth in chiral technology, with the global market projected to surpass $10.7 billion by 2030, primarily driven by demand for enantiomerically pure pharmaceuticals [3]. Within this landscape, enantioselective biocatalysis—using enzymes to selectively synthesize single enantiomers—has emerged as a powerful tool for sustainable and precise manufacturing of chiral drugs [4] [5].

The Molecular Basis of Enantioselectivity

Fundamental Principles of Chirality

Stereogenic centers, typically carbon atoms bonded to four different substituents, are the most common source of chirality in organic molecules. However, recent research has revealed novel chiral configurations, including stereogenic centers based on oxygen and nitrogen atoms and chiral-at-metal complexes where asymmetry arises from the spatial arrangement of ligands around a metal center [6] [2]. These diverse manifestations of chirality share a common principle: the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms determines biological recognition and response.

Mechanisms of Biological Discrimination

The enantioselectivity of biological systems stems from the chiral nature of biomolecules. Proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates are inherently chiral, creating environments that interact differently with each enantiomer of a chiral compound. This differential binding arises from distinct intermolecular interactions—hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions—that vary in strength and geometry between enantiomers and their chiral biological targets [1].

In enzymatic catalysis, enantioselectivity is quantified by the enantiomeric ratio (E-value), which reflects the enzyme's relative preference for one enantiomer over another in kinetic resolutions. This preference stems from energy differences in the diastereomeric transition states formed between the enzyme and each enantiomer [7].

Engineering Enantioselectivity: Rational Design Strategies for Enzymes

Rational enzyme design represents a knowledge-driven approach to engineering enantioselectivity, leveraging structural and mechanistic insights to create targeted mutations that enhance stereochemical preference. Unlike directed evolution, which relies on extensive random mutagenesis and screening, rational design uses understanding of structure-function relationships to predict mutations that will improve enantioselectivity [4] [5]. The following table summarizes major rational design strategies used to engineer enzyme enantioselectivity:

Table 1: Rational Design Strategies for Engineering Enzyme Enantioselectivity

| Strategy | Fundamental Principle | Key Methodologies | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | Identify conserved residues and "conserved but different" (CbD) sites in homologous enzymes with desired selectivity [4]. | Sequence alignment tools (ClustalOmega, MUSCLE), phylogenetic analysis [4]. | Engineering Bacillus-like esterase (EstA) by mutating GGS motif to conserved GGG, enhancing activity toward tertiary alcohol esters by 26-fold [4]. |

| Steric Hindrance Optimization | Modify active site volume and geometry to preferentially accommodate one enantiomeric transition state [4]. | Structure-guided site-saturation mutagenesis, computational modeling of substrate docking [4]. | Remodeling interaction networks around catalytic triad to reverse enantiopreference of amidase for desymmetrization of meso heterocyclic dicarboxamides [4]. |

| Interaction Network Remodeling | Reconfigure hydrogen bonding and electrostatic networks within the active site to stabilize one enantiomer [4]. | Molecular dynamics simulations, quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations [4]. | Engineering enantioselective SNAr biocatalyst through directed evolution, achieving >99% e.e. for coupling reactions [8]. |

| Protein Dynamics Engineering | Modify conformational flexibility and dynamics to favor productive binding of target enantiomer [4]. | B-factor analysis, molecular dynamics simulations, consensus mutations [5]. | Applying B-FIT (B-Factor Iterative Test) method to target flexible residues for saturation mutagenesis to enhance stability and selectivity [5]. |

| Computational Protein Design | De novo design of active site architecture for target enantioselectivity using advanced algorithms [4]. | Rosetta, FoldX, machine learning prediction of enantioselectivity [4] [7]. | Machine learning-assisted prediction of amidase enantioselectivity using random forest classification models based on substrate descriptors [7]. |

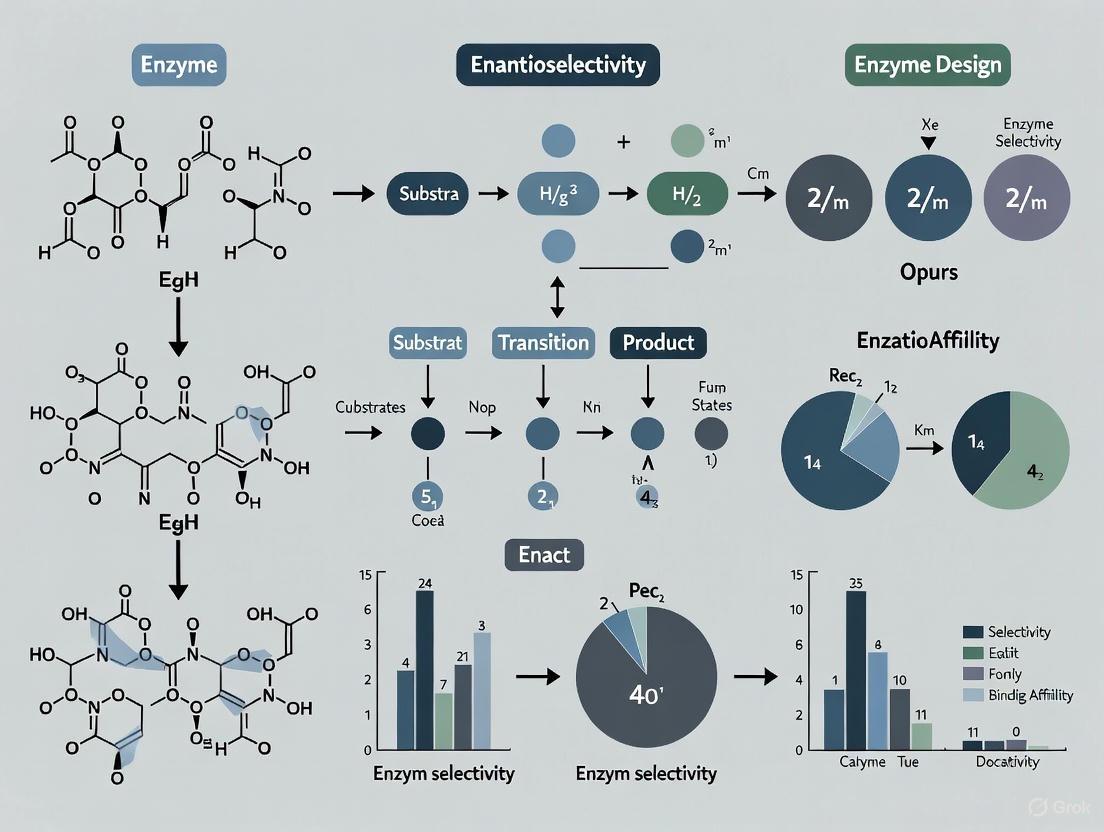

The workflow below illustrates how these computational and experimental elements integrate in a rational design cycle for engineering enantioselective enzymes:

Case Study: Engineering an Enantioselective SNAr Biocatalyst

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) is a cornerstone reaction in pharmaceutical and agrochemical synthesis, traditionally requiring harsh conditions and offering poor stereocontrol. Recently, researchers successfully engineered a bespoke enzyme, SNAr1.3, capable of catalyzing enantioselective SNAr reactions with remarkable efficiency [8].

The engineering journey began with MBH32.8, a Morita-Baylis-Hillmanase containing a flexible Arg124 residue that could be repurposed for SNAr catalysis. Through iterative rounds of site-saturation mutagenesis targeting 41 active-site residues and screening approximately 4,000 variants, the SNAr1.3 variant emerged with six key mutations. The optimized biocatalyst achieved a 160-fold efficiency improvement over the parent template, with near-perfect stereocontrol (>99% e.e.), high turnover (0.15 s⁻¹), and broad substrate acceptance, including challenging 1,1-diaryl quaternary stereocenters [8].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Engineering and Implementing Enantioselective SNAr Biocatalysis

| Research Reagent | Specifications/Conditions | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| SNAr1.3 Enzyme | 0.5 mol% loading, phosphate buffer (46.4 mM Na₂HPO₄, 3.6 mM NaH₂PO₄) [8]. | Engineered biocatalyst for enantioselective nucleophilic aromatic substitution. |

| Aryl Halide Electrophiles | 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (2), bromide (4), and iodide (5) analogs; 2.5 mM concentration [8]. | Electron-deficient aryl halide coupling partners; iodide variant showed 8.6-fold higher activity vs. chloride. |

| Carbon Nucleophiles | Ethyl 2-cyanopropionate (1); 7.7 mM KM value [8]. | Carbon-centered nucleophile for C-C bond formation; forms acyclic quaternary stereocenters. |

| UPLC Assay System | 96-well plate format, clarified cell lysate or purified protein [8]. | High-throughput screening method for evaluating conversion and enantioselectivity. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | NNK degenerate codons, 41 targeted active site residues [8]. | Library construction method for exploring sequence space and identifying beneficial mutations. |

Experimental Protocol: Machine Learning-Guided Engineering of Amidase Enantioselectivity

This protocol details a machine learning-assisted approach for predicting and engineering the enantioselectivity of amidases, adapted from a recent study [7].

Data Set Curation and Preprocessing

- Data Collection: Compile enantioselectivity data (E-values or ee values) for amidase-catalyzed reactions from literature and experimental results. The foundational study utilized 240 substrate reactions, including 160 kinetic resolutions and 80 desymmetrization reactions [7].

- Data Standardization: Transform all enantioselectivity measurements to enantiomeric ratio (E) values, then calculate the free energy difference (ΔΔG‡) using the equation: ΔΔG‡ = -RT ln E, where R is the gas constant and T is temperature in Kelvin [7].

- Data Classification: Categorize reactions as "positive" or "negative" based on ΔΔG‡ thresholds corresponding to practical enantioselectivity levels (e.g., 2.40 kcal/mol ≈ 90% ee at 303 K) [7].

Feature Engineering and Model Training

Descriptor Calculation:

- Compute chemistry descriptors based on molecular "cliques" derived from substrate structure.

- Calculate geometry descriptors as histograms of weighted atomic-centered symmetry functions.

- Perform geometry optimization of all substrates using computational chemistry software (e.g., Gaussian 09) [7].

Feature Selection: Implement feature selection to identify the most informative descriptors, reducing model complexity and potential overfitting.

Model Training:

- Partition data into training (80%) and test (20%) sets.

- Train multiple classifier types (Random Forest, SVM, Logistics Regression, GBDT) using 5-fold cross-validation.

- Select the best-performing model based on accuracy, precision, recall, F-score, and AUC metrics. The foundational study found Random Forest most effective [7].

Model Implementation and Experimental Validation

Enantioselectivity Prediction: Use the trained model to predict the enantioselectivity of amidase toward new substrates, prioritizing those predicted to yield high enantioselectivity.

Virtual Mutagenesis Screening:

- Create in silico mutant libraries targeting active site residues.

- Use the trained model to predict enantioselectivity of variants toward target substrates.

- Select top-predicted variants for experimental testing.

Experimental Validation:

- Express and purify selected amidase variants.

- Assay enzymatic activity and enantioselectivity toward target substrates using analytical chromatography (e.g., chiral HPLC or GC).

- Compare experimental results with model predictions to validate and refine the computational model.

The machine learning workflow integrates computational and experimental components as shown below:

This approach enabled the identification of an optimized amidase variant with a 53-fold higher E-value compared to the wild-type enzyme [7].

Analytical Methods for Enantioselectivity Assessment

Chromatographic Techniques

Chiral chromatography is the cornerstone of enantioselectivity assessment in enzyme engineering. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) systems equipped with chiral stationary phases (e.g., cyclodextrin, macrocyclic glycopeptide, or polysaccharide-based columns) enable separation and quantification of enantiomers [1]. Method development should optimize mobile phase composition, flow rate, and temperature to achieve baseline separation. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) provides enhanced resolution and faster analysis times, crucial for high-throughput screening [8].

Spectroscopic and Sensor-Based Methods

Polarimetry offers a traditional but effective approach for enantiopurity assessment when authentic standards are available. More recently, chiral sensor arrays and spectroscopic techniques coupled with multivariate analysis have emerged as rapid screening tools. While these methods may provide less comprehensive information than chromatography, they enable much higher throughput for initial screening phases.

The strategic importance of enantioselectivity in drug development continues to grow alongside advances in rational enzyme design methodologies. The integration of machine learning with structural biology and high-throughput experimentation represents a paradigm shift in our ability to engineer enantioselective biocatalysts [7]. These data-driven approaches enable researchers to navigate the vast sequence-function space more efficiently, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches.

Future developments will likely focus on generalizable design principles that transcend individual enzyme families and reaction types. The expansion of 3D structure databases and continued development of accurate activity prediction algorithms will further accelerate the design-test-learn cycle in enzyme engineering [5]. Additionally, the exploration of non-canonical chiral elements—such as the recently discovered stable chiral centers based on oxygen and nitrogen atoms—may open new frontiers in chiral drug design [6].

As the pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to develop more selective therapeutics with reduced environmental impact, biocatalytic approaches to enantioselective synthesis will play an increasingly central role. The rational design strategies and experimental frameworks outlined in this document provide a roadmap for researchers to contribute to this rapidly evolving field, ultimately enabling the development of safer, more effective chiral pharmaceuticals.

The global market for chiral technology and chemicals demonstrates robust growth, driven by the critical need for enantiopure compounds in precision-driven industries. Table 1 summarizes the key market data, highlighting the significant economic value and growth trajectories across different segments.

Table 1: Global Market Overview for Chiral Technology and Chemicals

| Market Segment | Market Size (2024) | Projected Market Size (2030+) | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiral Technology Market [3] [9] | USD 8.6 Billion | USD 10.7 Billion (2030) | 3.6% | Demand for pure pharmaceuticals, regulatory standards |

| Chiral Chemicals Market [10] | USD 88.52 Billion | USD 259.42 Billion (2033) | 11.67% | Single-enantiomer drugs, agrochemicals |

| Chiral Synthesis Services [11] | - | USD 4.17 Billion (2025) | 8.6% (2019-2033) | Outsourcing of complex synthesis |

The pharmaceutical sector is the dominant force, accounting for approximately 70.8% of the chiral chemicals market share [10]. This dominance is underpinned by the stark differences in biological activity that enantiomers can exhibit. For instance, while the S-enantiomer of ketamine is an anesthetic, its R-enantiomer is hallucinogenic [12]. Similarly, only the S-enantiomer of Crizotinib is active as a kinase inhibitor, with the R-enantiomer being essentially inactive [12]. These examples underscore the therapeutic imperative for enantiopurity, a focus reinforced by stringent regulatory requirements from bodies like the FDA and EMA, which mandate high purity standards for new chiral drugs [3] [9].

The agrochemical industry is another major driver, increasingly adopting chiral compounds to develop herbicides and pesticides with superior target selectivity and a reduced environmental footprint [10] [13]. The push towards green chemistry is also accelerating innovation, with biocatalysis emerging as a key sustainable and efficient technology for producing enantiomerically pure compounds [13].

Application Note 1: Biocatalytic Synthesis of Enantiopure Phenylalaninol

Rationale and Business Case

Enantiopure phenylalaninol is a vital intermediate in pharmaceuticals, notably for the one-step synthesis of solriamfetol, an approved drug for excessive daytime sleepiness [14]. Traditional chemical synthesis routes face challenges including harsh reaction conditions, costly metal catalysts, and significant waste production. A biocatalytic cascade approach offers a greener, more sustainable alternative that aligns with the principles of rational enzyme design for high enantioselectivity.

Experimental Protocol: One-Pot Two-Stage Cascade Biocatalysis

Objective: To convert biobased L-phenylalanine into (R)- or (S)-phenylalaninol with high enantiomeric excess (ee) [14].

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the multi-step enzymatic cascade for synthesizing enantiopure phenylalaninol.

Procedure:

Stage 1 - Reconstruction of the Carbon Skeleton:

- In a suitable reaction buffer, combine biobased L-phenylalanine (150 mg scale) with engineered recombinant E. coli EAL-RR cells. These cells co-express the enzymes L-amino acid deaminase (LAAD), α-keto acid decarboxylase (ARO10), and the novel benzaldehyde lyase (RpBAL) from Rhodopseudomonas palustris [14].

- Incubate the mixture with agitation to allow the sequential deamination, decarboxylation, and hydroxymethylation reactions to proceed.

- Monitor the reaction for the formation of the aldehyde intermediate.

Stage 2 - Asymmetric Reductive Amination:

- To the same pot, add E. coli ATA cells expressing an amine transaminase with the desired enantioselectivity [14].

- Include necessary co-substrates (e.g., an amine donor) for the transaminase reaction.

- Continue incubation until the reaction reaches completion.

Workup and Isolation:

- Separate the cells from the reaction mixture via centrifugation.

- Extract the product from the supernatant and purify using standard techniques (e.g., chromatography).

- Analyze the final product for chemical purity and enantiomeric excess using chiral HPLC or GC [14].

Key Outcomes:

- Conversion: 72% for (R)-phenylalaninol; 80% for (S)-phenylalaninol [14].

- Enantiomeric Excess (ee): >99% for both enantiomers [14].

- Isolated Yield: 60-70% on a 150 mg scale [14].

Application Note 2: Deracemization of Atropisomeric Biaryls

Rationale and Business Case

Atropisomers—stereoisomers arising from restricted rotation around a single bond—are privileged scaffolds in asymmetric catalysis and as pharmacophores in drug discovery [15]. Traditional methods for obtaining enantiopure atropisomers, such as chromatography or kinetic resolution, have a maximum theoretical yield of 50%. A P450-catalyzed deracemization process overcomes this limitation, enabling quantitative yields and providing a novel route to these valuable compounds through controlled bond rotation rather than bond formation [15].

Experimental Protocol: P450-Catalyzed Deracemization of BINOL

Objective: To achieve stereoconvergent conversion of racemic BINOL (rac-5) to enantioenriched (R)-BINOL [15].

Workflow: The deracemization process involves a cyclic redox mechanism to achieve stereoconvergence, as shown below.

Procedure:

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a solution of rac-BINOL (rac-5) in an appropriate buffer.

- Add the engineered P450 enzyme variant (e.g., derived from CYP158A2) with its fused reductase domain [15].

- Include the NADPH cofactor recycling system: NADP+, glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) [15].

- Include sodium ascorbate, which is critical for high substrate recovery [15].

Deracemization Reaction:

- Incubate the reaction mixture at the optimal temperature and pH for the P450 variant.

- Monitor the reaction progress and enantiomeric ratio over time using chiral analytical methods (e.g., HPLC).

Key Outcomes:

- Starting from rac-BINOL (50:50 er), the enantiomeric ratio increased to 90:10 enantiomeric ratio (er) favoring (R)-BINOL [15].

- The process demonstrated high recovery (91-95%) of the BINOL starting material, confirming a deracemization mechanism over kinetic resolution [15].

Application Note 3: High-Efficiency Enzymatic Resolution in a Three-Liquid-Phase System

Rationale and Business Case

Enzymatic resolution is a common industrial method but often suffers from limitations such as low catalytic efficiency, difficulties in product recovery, and challenges in enzyme reuse. A Three-Liquid-Phase System (TLPS) addresses these issues by creating a multi-compartment reaction and separation medium that enhances enzyme performance, enables simultaneous product separation, and allows for straightforward enzyme recycling [16].

Experimental Protocol: Lipase-Catalyzed Resolution in TLPS

Objective: To resolve racemic 1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethanol with high efficiency, enantioselectivity, and enzyme reusability [16].

Workflow: The TLPS separates reagents, products, and catalysts into distinct phases for efficient resolution and recovery.

Procedure:

TLPS Formation:

- Construct the TLPS by combining isooctane (hydrophobic solvent), an aqueous solution of PEG600, and an aqueous solution of Na₂SO₄ [16].

- Allow the system to equilibrate until three distinct, clear liquid phases form.

Enzymatic Resolution:

- Add the racemic secondary alcohol substrate (e.g., rac-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethanol) and the lipase enzyme (e.g., Burkholderia cepacia lipase) to the pre-formed TLPS [16].

- Initiate the kinetic resolution by adding the acyl donor (e.g., vinyl acetate) [16].

- Incubate the mixture with continuous shaking to maintain interfacial area.

Product Separation and Enzyme Reuse:

- After the reaction, allow the phases to separate completely.

- The (R)-ester product partitions into the top isooctane phase for easy recovery.

- The (S)-alcohol product partitions into the bottom Na₂SO₄ solution phase.

- The lipase enzyme remains concentrated in the middle PEG600 phase, which can be directly reused in subsequent reaction cycles by adding fresh substrate and solvent phases [16].

Key Outcomes:

- Conversion: ~49.8% (close to theoretical maximum for kinetic resolution) [16].

- Enantiomeric Excess (ee): >99% for both the (S)-alcohol and (R)-ester products [16].

- Enzyme Reusability: The lipase retained over 85% of its initial activity after 10 repeated reaction cycles [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enantioselective Biocatalysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Whole Cells [14] | Living factories co-expressing multiple cascade enzymes; simplify reaction setups. | One-pot synthesis of phenylalaninol using engineered E. coli EAL-RR and ATA cells. |

| Chiral Amine Transaminases (ATAs) [14] | Catalyze the stereoselective transfer of an amino group to a keto acid; key for introducing chiral amine centers. | Synthesis of (R)- and (S)-phenylalaninol from 3-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanal. |

| Benzaldehyde Lyase (RpBAL) [14] | Catalyzes the hydroxymethylation of aldehydes; broad substrate tolerance for aryl aliphatic aldehydes. | Formation of the chiral precursor 3-hydroxy-3-phenylpropanal in the phenylalaninol cascade. |

| Engineed P450 Enzymes [15] | Catalyze deracemization via a proposed oxidation/rotation/reduction mechanism; enable access to enantioenriched atropisomers. | Deracemization of rac-BINOL to (R)-BINOL with 90:10 er. |

| NADPH Cofactor Recycling System [15] | Regenerates the essential NADPH cofactor in situ using G6P and G6PDH; makes oxidative biocatalysis economical. | Essential for driving the P450-catalyzed deracemization reaction. |

| Lipase Enzymes [16] | Catalyze the enantioselective transesterification or hydrolysis of alcohols; workhorse enzymes for kinetic resolution. | Resolution of rac-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethanol in the Three-Liquid-Phase System. |

| Three-Liquid-Phase System (TLPS) [16] | A reaction medium (e.g., Isooctane/PEG/Na₂SO₄) that simultaneously separates products and allows enzyme recovery. | Enables high-efficiency enzymatic resolution with easy product isolation and enzyme reuse. |

Protein engineering has become an indispensable tool for developing biocatalysts with tailored properties for applications in pharmaceuticals, bioenergy, and fine chemicals. Two primary strategies have emerged for engineering enzymes: rational design and directed evolution. While directed evolution mimics natural selection in the laboratory through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening, rational design employs computational and structural insights to make precise, targeted mutations [4] [17]. The choice between these approaches significantly impacts the efficiency, cost, and outcome of enzyme engineering projects, particularly when aiming to enhance complex properties such as enantioselectivity. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their application in engineering enzyme enantioselectivity, with practical protocols and implementation guidelines for researchers in drug development and biocatalysis.

Comparative Analysis: Core Principles and Methodologies

The fundamental distinction between rational design and directed evolution lies in their approach to exploring protein sequence space. Rational design operates from a position of knowledge, using understanding of protein structure-function relationships to predict beneficial mutations. In contrast, directed evolution is an empirical discovery process that screens large libraries of random variants to identify improved clones [4] [17].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Protein Engineering Strategies

| Feature | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Approach | Knowledge-driven, deterministic | Empirical, probabilistic |

| Mutation Strategy | Targeted, specific mutations | Random mutagenesis across gene |

| Structural Requirements | High-resolution structure or reliable homology model beneficial | No structural information required |

| Throughput Requirements | Low to medium (dozens to hundreds of variants) | Very high (thousands to millions of variants) |

| Primary Challenge | Requires deep understanding of structure-function relationships | Requires robust high-throughput screening method |

| Time Investment | Primarily in computational analysis and design | Primarily in library construction and screening |

| Typical Applications | Active site engineering, stability enhancement, mechanism manipulation | Broad property optimization, especially when structural knowledge is limited |

Rational Design Strategies for Engineering Enantioselectivity

Sequence-Based Approaches

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) serves as a powerful starting point for rational design. By comparing homologous enzymes with known functional differences, researchers can identify "conserved but different" (CbD) sites where variation correlates with functional divergence [4] [18]. For instance, when engineering a Bacillus-like esterase (EstA) to improve its activity toward tertiary alcohol esters, researchers used MSA of 1,343 sequences to identify a non-conserved serine residue in a GGS motif (versus the conserved GGG motif in homologs). Mutation to the conserved glycine (EstA-GGG) enhanced conversion of tertiary alcohol esters by 26-fold [4].

The "back-to-consensus" approach extends this logic, mutating residues in a target enzyme to the most frequent amino acid found at that position among homologous sequences [4] [18]. This strategy leverages evolutionary information to guide engineering decisions.

Structure-Based Approaches

When high-resolution structural information is available, several powerful strategies become feasible:

Steric Hindrance Engineering: Strategically introducing bulky residues near the active site can physically block binding of one enantiomer while permitting access to the other. This approach successfully enhanced the enantioselectivity of a phosphotriesterase, lipase, and yeast old yellow enzyme [18].

Interaction Network Remodeling: Modifying hydrogen bonding or electrostatic networks surrounding the active site can alter substrate positioning and transition state stabilization. This strategy improved enantioselectivity in P411 enzymes, lipase CALB, and esterase BioH [18].

Dynamics Modification: Targeting residues that influence protein dynamics and conformational sampling can profoundly impact enantioselectivity, as demonstrated with alcohol dehydrogenase and lipase CALB [18].

Computational Protein Design

Advanced computational methods now enable precise enzyme redesign through molecular dynamics simulations, quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations, and machine learning approaches [19] [20]. For example, the CataPro deep learning model predicts enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) using protein sequence and substrate structure, enabling in silico screening of potential enzyme variants [20]. Similarly, machine learning classifiers have been developed specifically to predict amidase enantioselectivity toward new substrates [7].

These computational approaches are particularly valuable for enantioselectivity engineering, where traditional methods struggle to predict the subtle energy differences between diastereomeric transition states.

Directed Evolution Strategies for Engineering Enantioselectivity

Library Generation Methods

Directed evolution employs various mutagenesis strategies to create genetic diversity:

Error-prone PCR: Introduces random point mutations throughout the gene by adjusting PCR conditions to reduce polymerase fidelity [17].

DNA Shuffling: Recombines fragments from homologous genes to exchange functional domains or beneficial mutations [17] [21].

Site-saturation Mutagenesis: Targets specific residues to explore all possible amino acid substitutions at chosen positions [17].

The evolution of an esterase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (AFEST) exemplifies a typical directed evolution workflow, employing initial error-prone PCR followed by DNA shuffling of beneficial mutations across five rounds of evolution [21].

High-Throughput Screening Platforms

The success of directed evolution hinges on efficient screening of variant libraries:

Microtiter Plate-Based Screening: Traditional method screening ~104 variants per day using chromogenic or fluorogenic substrates [21].

Dual-Channel Microfluidic Droplet Screening (DMDS): Ultrahigh-throughput platform capable of screening ~107 enzyme variants per day using two-color fluorescence detection to simultaneously monitor activity toward different substrates [21].

The DMDS platform exemplifies cutting-edge screening technology, employing two operational modes: "cooperative mode" for enhancing activity toward a specific substrate, and "biased mode" for engineering selectivity between substrates [21].

Experimental Protocols

Rational Design Protocol: Active Site Remodeling for Enhanced Enantioselectivity

This protocol outlines a structure-based approach to improve enzyme enantioselectivity through targeted active site modifications.

Materials:

- Purified wild-type enzyme

- Enzyme substrates (both enantiomers)

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit

- Protein expression system (E. coli or other suitable host)

- Protein purification system (e.g., affinity chromatography)

- Analytical instrumentation for enantioselectivity assessment (HPLC with chiral column or GC)

Procedure:

Structural Analysis

- Obtain high-resolution crystal structure of the wild-type enzyme or generate a reliable homology model.

- Identify active site residues involved in substrate binding and catalysis.

- Perform molecular docking of both substrate enantiomers to identify residues that contribute differentially to binding each enantiomer.

Mutation Design

- Select target residues for mutagenesis based on docking results and evolutionary conservation analysis.

- Design specific mutations to create steric hindrance for the undesired enantiomer or to improve binding interactions with the desired enantiomer.

- Use computational tools (FoldX, Rosetta) to predict stability changes caused by designed mutations.

Library Construction

- Perform site-directed mutagenesis at selected positions.

- Alternatively, create small focused libraries (10-100 variants) using saturation mutagenesis at key positions.

Screening and Characterization

- Express and purify designed variants.

- Measure enzymatic activity and enantioselectivity for each variant.

- For promising variants, determine kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) for both enantiomers.

Iterative Design

- Combine beneficial mutations through structure-guided iterative design.

- Validate final designs with comprehensive biochemical characterization.

Directed Evolution Protocol: Ultrahigh-Throughput Screening for Enantioselective Enzymes

This protocol describes a directed evolution workflow using microfluidic droplet screening to engineer enantioselectivity.

Materials:

- Target gene cloned in appropriate expression vector

- Error-prone PCR mutagenesis kit

- Microfluidic droplet generation and sorting system (e.g., DMDS platform)

- Fluorogenic substrate analogs for both enantiomers

- Host cells for enzyme expression (typically E. coli)

- Flow cytometer for initial validation

Procedure:

Library Generation

- Perform error-prone PCR on target gene under conditions that yield 2-4 nucleotide mutations per gene.

- Clone mutated genes into expression vector and transform into host cells.

- Alternatively, use DNA shuffling to recombine beneficial mutations from previous evolution rounds.

Substrate Preparation

- Synthesize or procure fluorogenic substrates for both enantiomers, conjugated to different fluorophores (e.g., (S)-enantiomer linked to fluorescein, (R)-enantiomer linked to rhodamine derivative).

Droplet Screening

- Encapsulate single cells expressing enzyme variants in microfluidic droplets containing both fluorogenic substrates.

- Incubate droplets to allow enzyme expression and substrate conversion.

- Analyze droplets using dual-channel fluorescence detection to simultaneously monitor conversion of both enantiomers.

- Sort droplets based on predefined fluorescence criteria using the DMDS platform.

Hit Validation

- Recover sorted variants and characterize enantioselectivity in microtiter plate format using authentic substrates.

- Sequence validated hits to identify beneficial mutations.

Iterative Evolution

- Use beneficial mutations as templates for subsequent rounds of evolution.

- Alternate between cooperative mode (enhancing activity toward desired enantiomer) and biased mode (suppressing activity toward undesired enantiomer) screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Enzyme Engineering

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology Tools | ||

| X-ray Crystallography | Determines high-resolution protein structures | Identifying active site architecture for rational design [22] |

| Cryo-EM | Determines structures of large complexes | Studying multi-enzyme assemblies [22] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Predicts substrate binding orientations | Virtual screening of active site mutations [19] |

| Library Construction | ||

| Error-prone PCR Kits | Introduces random mutations | Creating initial diversity in directed evolution [17] [21] |

| DNA Shuffling Protocols | Recombines beneficial mutations | Combining mutations from different variants [21] |

| Site-directed Mutagenesis Kits | Creates specific point mutations | Testing rational design hypotheses [4] |

| Screening Platforms | ||

| Microtiter Plate Readers | Medium-throughput screening | Initial validation of enzyme variants [21] |

| Flow Cytometry | High-throughput single-cell analysis | Screening cell-surface displayed enzymes [17] |

| Microfluidic Droplet Systems | Ultrahigh-throughput screening | DMDS platform for enantioselectivity engineering [21] |

| Computational Tools | ||

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates protein dynamics and flexibility | Assessing conformational changes [4] |

| Protein Design Software (Rosetta) | Predicts effects of mutations | In silico screening of variant libraries [4] [18] |

| Machine Learning Models (CataPro) | Predicts enzyme kinetic parameters | Prioritizing variants for experimental testing [20] [7] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows for rational design and directed evolution approaches to enzyme engineering. Rational design follows a knowledge-driven path (yellow to green), while directed evolution employs an empirical screening approach (blue to red). Modern practice often combines elements of both in hybrid approaches.

Rational design and directed evolution represent complementary approaches to enzyme engineering with distinct strengths and applications. Rational design excels when substantial structural and mechanistic knowledge is available, enabling precise targeting of specific residues with minimal experimental screening. Its applications in enantioselectivity engineering include steric hindrance strategies, interaction network remodeling, and computational protein design. Directed evolution provides a powerful alternative when structural insights are limited, leveraging high-throughput screening to explore sequence space empirically. Technological advances like microfluidic droplet screening have dramatically increased the efficiency of directed evolution campaigns.

The future of enzyme engineering lies in hybrid approaches that combine the predictive power of rational design with the exploratory strength of directed evolution. Machine learning models trained on structural data and experimental outcomes promise to further accelerate the engineering cycle [20] [7]. For researchers targeting enzyme enantioselectivity in drug development, the strategic integration of both methodologies offers the most robust path to creating efficient biocatalysts for asymmetric synthesis.

Enantioselectivity is a cornerstone of biocatalysis, enabling the asymmetric synthesis of chiral building blocks essential for the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries [23]. The profound biological significance of chirality means that the enantiomers of a drug often exhibit starkly different pharmacological effects, where one enantiomer may be therapeutic (eutomer) and the other may be inactive or even deleterious (distomer) [23] [24]. Enzymes have evolved to distinguish between these mirror-image molecules with exquisite precision. This application note delves into the key structural elements that govern this enantioselective binding, moving from the well-established catalytic triad to other critical architectural features of the enzyme active site. Framed within a broader thesis on rational design, this document provides structured data, detailed protocols, and visual tools to guide research in engineering enzyme enantioselectivity.

Structural Foundations of Enantioselectivity

The Catalytic Triad and Its Role in Stereocontrol

The catalytic triad—a conserved set of residues typically comprising a nucleophile (e.g., serine), a base (e.g., histidine), and an acid (e.g., aspartate)—is fundamental to the mechanism of many hydrolytic enzymes. Its primary role is to activate the nucleophile and stabilize the transition state during catalysis. For enantioselectivity, the precise geometry and electrostatic environment of the triad are paramount. For instance, in the esterase RhEst1, the catalytic triad (Ser101, Asp225, His253) is responsible for forming a low-barrier hydrogen bond that facilitates the nucleophilic attack on the substrate. The stereoelectronic requirements of this mechanism force the substrate into a specific orientation, thereby dictating enantiopreference [25]. Mutations that alter the spatial arrangement or hydrogen-bonding network of the triad can significantly impact enantioselectivity by disrupting the optimal geometry for transition state stabilization of one enantiomer over the other.

Beyond the Triad: Key Structural Elements Governing Enantioselectivity

While the catalytic triad is essential for the chemical step, enantioselective discrimination is often mediated by the broader architecture of the substrate-binding pocket.

- Substrate-Binding Tunnels and Pockets: Long, hydrophobic tunnels can enforce enantioselectivity by sterically excluding one enantiomer from productive binding. In Candida rugosa lipase, molecular modeling revealed that the fast-reacting (S)-enantiomer of a substrate productively binds within an acyl-binding tunnel, while the slow-reacting (R)-enantiomer is bound in a mode that leaves this tunnel vacant, preventing efficient catalysis [26].

- The "Oxyanion Hole": This structural motif, which stabilizes the negatively charged oxygen in the tetrahedral intermediate of esterase or lipase reactions, contributes to enantioselectivity through precise pre-organization and electrostatic complementarity with only one of the enantiomeric transition states [25].

- Cap Domains and Flexible Loops: Dynamic structural elements, such as the α/β hydrolase cap domain, can act as gates to the active site. Engineering these regions can reshape the active site entrance and alter enantioselectivity. In RhEst1, mutations in the cap domain (e.g., A143T) were crucial for recovering high enantioselectivity that had been lost in earlier engineered variants [25].

- Residue Interaction Networks (RIN): Beyond single residues, the network of interactions within the active site can allosterically influence enantioselectivity and stability. RIN analysis of RhEst1 mutants linked enhanced thermostability to a more robust interaction network, which indirectly stabilizes the active site in a conformation favorable for enantioselectivity [25].

Table 1: Key Structural Elements Governing Enantioselectivity

| Structural Element | Primary Function | Impact on Enantioselectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Triad | Catalysis; Transition State Stabilization | Determines the stereoelectronic requirements for the reaction mechanism. |

| Substrate-Binding Tunnels | Substrate Recognition and Orientation | Sterically filters enantiomers based on size and shape complementarity. |

| Oxyanion Hole | Transition State Stabilization | Provides precise electrostatic stabilization for one enantiomeric transition state. |

| Cap Domains/Loops | Active Site Access & Dynamics | Controls substrate entry and product release, imposing a steric checkpoint. |

| Residue Interaction Network (RIN) | Structural Stability & Allostery | Maintains active site architecture and can transmit effects from distal mutations. |

Quantitative Data on Engineered Enantioselectivity

Rational design strategies have successfully engineered enzyme enantioselectivity across various enzyme classes. The following table summarizes representative examples from recent literature, illustrating the impact of specific mutations.

Table 2: Representative Examples of Rationally Engineered Enantioselectivity

| Enzyme | Target Property | Rational Design Strategy | Key Mutations | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esterase RhEst1 | Enantioselectivity & Activity | Cap domain engineering; MD simulations | A147I/V148F/G254A (M1) + A143T (M2) | M1: 5x activity, ↓ e.e.M2: 6x activity, recovered e.e. (~99:1 er) | [25] |

| Limonene Epoxide Hydrolase (ReLEH) | Reprogrammed Reactivity (Baldwin Cyclization) | Disrupting water network; Active site hydrophobicity | Y53F/N55A (SZ611) | Shift from hydrolysis to cyclization; up to 78% yield of Baldwin product. | [27] |

| Candida rugosa Lipase | Understanding Inhibition | Molecular modeling of binding modes | N/A | Revealed molecular mechanism for enantioselective inhibition by long-chain alcohols. | [26] |

| P411 Enzyme | Enantioselectivity | Remodeling interaction network | Not Specified | Improved enantioselectivity for target reaction. | [18] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Workflow for Rational Design of Enantioselectivity

This protocol outlines a general workflow for using rational design to improve enzyme enantioselectivity, integrating multiple computational and experimental steps.

Protocol 2: Computational Analysis of Substrate Binding Modes

Objective: To identify the structural basis for enantioselectivity by comparing the binding poses of R- and S-enantiomers. Materials:

- High-resolution crystal or homology model of the enzyme (PDB format).

- 3D structures of the R- and S-substrate enantiomers.

- Molecular docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina [25]).

- Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation software (e.g., NAMD [25]).

- Visualization software (e.g., VMD [25]).

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the enzyme structure. Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add polar hydrogens and assign partial charges using the appropriate force field (e.g., AMBER ff14SB [25]).

- Prepare the substrate enantiomers: Draw the 3D structures of the R and S substrates. Energy-minimize them using a molecular mechanics force field. Assign Gasteiger charges or other charges suitable for the docking program.

Define the Search Space:

- Identify the active site residues, typically centered around the catalytic triad. Define a grid box that encompasses the entire binding pocket and its immediate vicinity for docking calculations.

Molecular Docking:

- Dock both the R- and S-enantiomers into the enzyme active site. Use an exhaustiveness setting high enough to ensure reproducible results (e.g., 20-50 for AutoDock Vina). Perform multiple docking runs for each enantiomer.

Pose Analysis and Clusterization:

- Cluster the resulting docking poses based on root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). Select the top-ranked pose from the largest cluster for each enantiomer for further analysis.

- Critically analyze the differences:

- Does the fast-reacting enantiomer form a more optimal geometry with the catalytic triad?

- Is the oxyanion of the favored transition state better stabilized?

- Are there steric clashes between the slow-reacting enantiomer and specific active site residues (e.g., tunnel walls, cap domain residues)?

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations (Optional but Recommended):

- Solvate the top enzyme-substrate complexes for each enantiomer in a water box with ions.

- Run MD simulations (e.g., 50-100 ns) to assess the stability of the binding poses and observe the dynamic interactions that may not be evident from static docking.

- Calculate the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of the enzyme backbone to identify regions of flexibility impacted by substrate binding.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Calculations (Advanced):

- For a more quantitative prediction, use FEP calculations to compute the relative binding free energy difference between the R- and S-enantiomer complexes. This provides a theoretical eudysmic ratio [25].

Expected Outcome: A molecular-level understanding of why one enantiomer is preferred, identifying specific residues for mutagenesis to alter enantioselectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Enantioselectivity Research

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Example Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Software | Protein structure visualization, docking, and MD simulations. | AutoDock Vina [25], VMD [25], NAMD [25], Modeller [25] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduction of specific point mutations into the gene of interest. | Commercial kits from suppliers (e.g., Q5 from NEB, QuikChange from Agilent) |

| Chiral Stationary Phase HPLC/GC Columns | Analytical separation of enantiomers to determine enantiomeric excess (e.e.). | Chiralpak or Chiraleel (HPLC), Chiraldex (GC) columns |

| Protein Crystallization Kits | Obtaining high-resolution enzyme structures for rational design. | Sparse matrix screens from Hampton Research or Qiagen |

| Hydrophobic Residues (Amino Acids) | Saturation mutagenesis to sterically reshape the binding pocket. | Oligonucleotides encoding Val, Ile, Leu, Phe [27] |

The rational design of enzyme enantioselectivity has progressed from relying solely on the catalytic triad to encompass a holistic view of the active site as a complex, dynamic system. Elements such as substrate-access tunnels, cap domains, and residue interaction networks play decisive roles in chiral discrimination. By employing the integrated strategies, protocols, and tools outlined in this document—from computational analysis and steric hindrance engineering to interaction network remodeling—researchers can systematically decode and reprogram the structural logic of enantioselective binding. This approach is instrumental for developing next-generation biocatalysts for the efficient and sustainable synthesis of high-value chiral molecules.

The pursuit of engineering enzyme enantioselectivity—the ability to favor the production of one chiral molecule over its mirror image—represents a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, with profound implications for pharmaceutical synthesis and sustainable chemistry. The journey from initial protein modification techniques to today's sophisticated computational algorithms has transformed our capacity to tailor enzyme specificity. This evolution began with the foundational technique of site-directed mutagenesis (SDM), developed by Michael Smith in 1978, which enabled precise investigation of how specific amino acids influence protein structure and function [18] [4]. This breakthrough, garnering the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, laid the essential groundwork for all rational enzyme design by allowing researchers to test hypotheses about structure-function relationships directly.

For decades, directed evolution—an iterative process of random mutagenesis and high-throughput screening—dominated enzyme engineering, earning Frances H. Arnold the 2018 Nobel Prize [18] [4]. However, this approach is often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and limited by the availability of high-throughput screening methods [18] [4]. In response, the field has progressively shifted toward rational design strategies, accelerated by increasing computational power, growing protein structure databases, and more advanced algorithms [18]. These rational methods aim to predict function-enhancing mutants based on an understanding of enzyme mechanism and structure before laboratory testing, significantly streamlining the engineering process. This article traces these pivotal historical milestones, detailing the key protocols and reagent solutions that have shaped the rational design of enantioselective enzymes.

Foundational Strategies: Sequence and Structure-Based Design

Strategy 1: Multiple Sequence Alignment

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) leverages evolutionary information from homologous enzymes to guide mutagenesis. The core principle is that enzymes with high sequence identity and structural similarity often share functional properties, and residues conserved across homologs can provide critical insights for engineering [18] [4].

Protocol: Engineering Enantioselectivity via MSA

- Identify Homologs: Perform a database search (e.g., using BLAST) to identify a diverse set of protein sequences homologous to your target enzyme.

- Perform Alignment: Use software such as Clustal Omega or MUSCLE to align the sequences. Visually inspect the alignment, focusing on the region surrounding the active site.

- Identify "Conserved but Different" (CbD) Sites: Pinpoint residues that are highly conserved among the homologs but are different in your target enzyme. These CbD sites are prime targets for mutagenesis [18] [4].

- Design and Create Mutants: Use site-directed mutagenesis to substitute the target amino acid in your enzyme with the conserved residue found in the homologs.

- Express and Screen: Express the variant enzymes and assay them for enantioselectivity (e.g., by measuring the enantiomeric ratio, E).

Application Note: This strategy was successfully applied to engineer a Bacillus-like esterase (EstA). MSA of over 1,300 sequences revealed a conserved GGG motif in the oxyanion hole, whereas EstA possessed a GGS motif. The S→G mutation to create the EstA-GGG variant enhanced its conversion of tertiary alcohol esters by 26-fold [18] [4].

Strategy 2: Steric Hindrance Engineering

This approach focuses on reshaping the enzyme's active site pocket to preferentially accommodate one enantiomer of a substrate over the other by introducing or relieving steric constraints [18].

Protocol: Modeling and Mutating Binding Pocket Residues

- Obtain a 3D Structure: Acquire a crystal structure or a high-quality computational model (e.g., from AlphaFold) of your enzyme, ideally with a bound substrate or inhibitor.

- Analyze Substrate Binding Modes: Use molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL) to model the productive binding modes for both the R- and S-enantiomers of the target substrate.

- Identify Steric Conflict Points: Identify residues in the binding pocket that cause steric clash with the fast-reacting enantiomer or provide insufficient space for the slow-reacting enantiomer.

- Design Size-Reducing/Enlarging Mutations: To improve selectivity for a target enantiomer, design mutations that increase steric clash for the undesired enantiomer (e.g., mutating to a larger side chain like Val or Phe) or create more space for the desired enantiomer (e.g., mutating to a smaller side chain like Gly or Ala).

- Validate In Silico and In Vitro: Use simple docking or energy calculations to pre-screen designs before proceeding with SDM and experimental characterization.

Application Note: A classic example is the engineering of a phosphotriesterase for enantioselective hydrolysis. By rationally mutating a binding pocket residue to a bulkier amino acid, researchers successfully altered the enzyme's stereochemical preference, demonstrating the power of manipulating active site volume [18].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical progression and decision points in a rational enzyme engineering campaign, integrating the strategies discussed in this article.

The Thermodynamic Turn and the Role of Dynamics

A pivotal advancement in the field was the realization that enantioselectivity is governed by both enthalpic (ΔH‡) and entropic (TΔS‡) components of the activation free energy difference (ΔΔG‡) between enantiomers [28]. The relationship is defined by:

-RTlnE = ΔΔG‡ = ΔΔH‡ - TΔS‡

where E is the enantiomeric ratio, R is the gas constant, and T is the temperature [28].

- Key Insight: A 2001 study on Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) variants demonstrated that changes in enantioselectivity often result from compensatory changes in both ΔΔH‡ and ΔΔS‡ [28]. For instance, the T103G variant showed increased enantioselectivity (E from 970 to 2140) because the favorable increase in ΔΔH‡ was not fully counteracted by the unfavorable increase in ΔΔS‡. This highlighted that rational design must account for both thermodynamic parameters, not just steric fit [28].

Strategy 3: Dynamics Modification

This strategy targets residues distant from the active site to modulate the enzyme's conformational flexibility and dynamics, which can profoundly influence the entropy of the transition state and thus enantioselectivity [18].

Protocol: Targeting Allosteric and Remote Sites

- Identify Dynamic Networks: Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify networks of residues that are correlated in their motion with the active site.

- Select Rigidifying/Flexibilizing Mutations: Select remote or allosteric sites within these networks to introduce mutations (e.g., Pro mutations, disulfide bonds) that rigidify flexible regions, or Gly/Ala mutations to enhance flexibility, depending on the system.

- Measure Thermodynamic Parameters: For promising variants, determine ΔΔH‡ and ΔΔS‡ by measuring the enantiomeric ratio E at different temperatures and applying equation (1) [28].

- Correlate Dynamics with Selectivity: Analyze how the introduced mutations altered the collective dynamics of the protein and correlate these changes with the measured thermodynamic parameters.

Application Note: Engineering the conformational dynamics of Candida antarctica lipase B (CALB) by targeting residues involved in global flexibility has successfully altered its enantioselectivity profile, demonstrating that remote mutations can be as impactful as active-site modifications [18].

The Computational Frontier: Algorithms and De Novo Design

The modern era of enzyme engineering is defined by the integration of powerful computational methods, moving beyond analogies to natural enzymes toward de novo design and machine learning-guided optimization.

Strategy 4: Computational Protein Design

This strategy uses physical force fields and quantum mechanics (QM) to quantitatively predict the effects of mutations on substrate binding, transition state stabilization, and catalytic rate [29].

Protocol: A Physics-Based In Silico Screening Pipeline

- Generate a Structural Model: Obtain a high-quality structure of the enzyme-substrate complex in a transition state-like geometry.

- Define a Design Library: Select a set of residues in the active site or second coordination sphere for virtual mutagenesis.

- Calculate Interaction Energies: Use molecular mechanics (MM) or QM/MM methods to calculate the interaction energy between the enzyme and the transition state for each enantiomer for every variant in the design library.

- Rank and Select Variants: Rank the designed mutants based on the predicted difference in transition state stabilization energy (ΔΔE) for the two enantiomers.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize and test the top-predicted variants.

Application Note: A landmark 2025 study engineered a highly enantioselective enzyme (SNAr1.3) for a non-natural nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) reaction. Starting from a promiscuous MBHase template, computational insights guided directed evolution to create a variant with a 160-fold improved efficiency and >99% enantiomeric excess (e.e.), showcasing the power of combining computational and evolutionary principles [8].

The Rise of Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) models are overcoming the challenge of epistasis—non-additive interactions between mutations—thereby improving the prediction of variant fitness from sequence data alone [30].

Protocol: innov'SAR for Predicting Enantioselectivity

- Create a Learning Set: Generate a small library of single-point mutants of the target enzyme and experimentally measure their enantioselectivity (E-value).

- Encode Sequences: Convert the amino acid sequences of the characterized mutants into numerical sequences using physicochemical properties from the AAindex database.

- Generate Protein Spectra: Process the numerical sequences using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to generate an "energy spectrum" for each variant.

- Build a Predictive Model: Use the energy spectra and the associated E-values as inputs to train a machine learning model (e.g., innov'SAR).

- Predict and Validate: Use the model to predict the E-values for all possible combinations of the single mutations. Synthesize and test the top-predicted multi-mutant combinations [30].

Application Note: Applying the innov'SAR method to an epoxide hydrolase from Aspergillus niger (ANEH) allowed researchers to predict highly enantioselective multi-mutant variants from a dataset of only 9 single-point mutants, dramatically reducing the experimental screening burden [30].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Rational Design for Enzyme Enantioselectivity

| Year | Milestone | Key Finding/Technology | Impact on Enantioselectivity Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Site-Directed Mutagenesis [18] [4] | Technique for making specific amino acid changes. | Enabled foundational testing of structure-function hypotheses. |

| 2001 | Thermodynamic Analysis of CALB [28] | Quantified enthalpy-entropy compensation in enantioselectivity. | Showed that both ΔΔH‡ and ΔΔS‡ must be considered in design. |

| 2000s | Steric Hindrance & MSA Strategies [18] [4] | Rational frameworks based on structure and evolution. | Provided systematic, non-random approaches to engineer activity and selectivity. |

| 2010s | Computational Protein Design [18] [29] | Use of force fields (Rosetta, FoldX) and QM/MM. | Enabled predictive in silico screening of mutant libraries. |

| 2018 | Machine Learning (innov'SAR) [30] | DSP-based prediction of variant fitness from sequence. | Addressed epistasis, predicting optimal multi-mutant combinations. |

| 2025 | De Novo SNAr Enzyme [8] | Creation of an enzyme for a new-to-nature reaction with high e.e. | Demonstrated the fusion of computational design and directed evolution for novel catalysis. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Rational Enzyme Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Enzyme Engineering | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduces specific point mutations into plasmid DNA. | Foundationally enabled by Michael Smith's work; commercial kits (e.g., from NEB) are standard. |

| NNK Degenerate Codons | Creates saturation mutagenesis libraries by encoding all 20 amino acids at a target site. | Essential for CASTing and exploring sequence space in directed evolution [8]. |

| Homologous Enzyme Panels | Provides sequences for Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA). | Sourced from databases (e.g., UniProt) or genome mining; used to identify CbD sites [18] [4]. |

| Molecular Visualization Software | Visualizes enzyme 3D structures and models substrate binding modes. | Software like PyMOL is critical for steric hindrance engineering. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software | Simulates enzyme flexibility and conformational dynamics. | Packages like GROMACS or AMBER are used in dynamics modification strategies [18] [29]. |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Software | Calculates electronic structures and reaction energies with high accuracy. | Used for transition state modeling and understanding catalytic mechanisms in computational design [29]. |

The rational design of enantioselective enzymes has evolved from a concept grounded in basic site-directed mutagenesis to a sophisticated discipline integrating evolutionary biology, structural analysis, thermodynamics, and computational science. The historical progression from manipulating single residues based on sequence alignment to deploying physics-based models and machine learning algorithms reflects a broader shift toward a predictive, first-principles understanding of enzyme function. As computational power continues to grow and algorithms become more refined, the promise of reliably designing perfectly selective biocatalysts from scratch is moving from a visionary goal to a tangible reality. This will undoubtedly accelerate the development of more efficient and sustainable synthetic routes in the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries.

Strategic Framework: Key Rational Design Methodologies for Enhancing Enantioselectivity

Within the framework of rational enzyme design, the pursuit of enhanced enantioselectivity is a primary objective for applications in pharmaceutical synthesis and fine chemicals. While de novo design remains challenging, evolutionary data embedded in protein sequences provides a powerful blueprint for engineering. The analysis of Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSA) allows researchers to identify conserved structural and functional elements, while the consensus mutation approach leverages the most frequent amino acids observed at each position across homologs to infer optimal function. These methods operate on the rationale that natural selection has already sampled a vast mutational space, and that the most prevalent solutions across a protein family often contribute to stability, activity, and selectivity. This application note details the practical application of MSA and consensus design, providing specific protocols and datasets to guide researchers in engineering enzyme enantioselectivity.

Fundamental Principles and Key Concepts

The MSA and consensus approach is predicated on the idea that enzymes with high sequence identity and structural similarity often share functional traits [4]. By aligning sequences from a diverse set of homologs, a pattern of conserved residues emerges.

- Consensus Design: This strategy is based on the hypothesis that the most frequent amino acid found at a given position in a multiple sequence alignment of homologous proteins contributes more favorably to stability and function than less frequent variants [4]. While initially applied to improve thermostability, targeting this approach to regions near the active site can directly influence catalytic properties like enantioselectivity.

- CbD (Conserved but Different) Sites: These are positions that are highly conserved within the family of homologous proteins but are different in the target enzyme sequence [4]. Mutating these sites in the target enzyme to match the conserved consensus can be a highly effective strategy for importing desirable functional properties from the homologs.

Table 1: Key Terminology for MSA-Based Engineering

| Term | Definition | Application in Enzyme Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | An alignment of three or more protein sequences, highlighting regions of similarity and divergence. | Identifies evolutionarily conserved residues critical for function and stability. |

| Consensus Mutation | Replacing an amino acid in a target sequence with the most frequent residue found at that position in an MSA. | Used to infer and install amino acids that optimize stability and function. |

| CbD Sites | "Conserved but Different" sites; positions that are conserved in homologs but differ in the target enzyme. | High-value targets for rational design to improve activity or selectivity. |

| Catalytic Triad | A set of three amino acid residues within an enzyme's active site that are essential for catalysis. | A highly conserved region in an MSA; mutations here are typically avoided unless supported by strong evidence. |

Quantitative Data from Representative Studies

The following case studies, summarized in Table 2, demonstrate the successful application of MSA and consensus approaches to engineer improved enzyme functions.

Table 2: Summary of Enzyme Engineering Cases Using MSA and Consensus Design

| Enzyme Engineered | Target Property | MSA Strategy | Key Mutation(s) | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus-like Esterase (EstA) [4] | Activity towards tertiary alcohol esters | MSA of 1,343 sequences identified a conserved GGG motif in the oxyanion hole. | S→G in GGS motif (creating EstA-GGG) | 26-fold increase in conversion rate of tertiary alcohol esters. |

| Glutamate Dehydrogenase (PpGluDH) [4] | Activity for reductive amination of PPO | Sequence alignment with a more active, poorly expressing homolog (BpGluDH). | I170M (one of six targeted mutations) | 2.1-fold enhanced activity while maintaining high soluble expression. |

| Amidase (AmdA) [4] | Activity for degrading ethyl carbamate | MSA with three known urethanases; CbD sites adjacent to the catalytic triad were targeted. | R94P, P163A, A172G, etc. (six mutations total) | Successfully generated mutants with improved EC degradation activity. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiple Sequence Alignment Analysis for Identifying Engineering Targets

This protocol describes the process for generating an MSA and analyzing it to identify consensus and CbD sites for mutagenesis.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Target Enzyme Sequence: The amino acid sequence of the enzyme to be engineered.

- Homologous Sequences: Retrieved from public databases (e.g., UniProt, NCBI) using tools like BLASTP.

- Alignment Software: Such as Clustal Omega, MUSCLE, or MAFFT.

- Visualization/Analysis Tool: BioEdit, Jalview, or similar software for analyzing conservation scores.

Procedure:

- Sequence Retrieval: Perform a homology search using the target enzyme sequence as a query against a protein sequence database. Select a diverse but relevant set of homologous sequences for alignment.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Input the collected sequences into your chosen alignment software using default parameters. Manually inspect and refine the alignment if necessary.

- Conservation Analysis: Use the analysis tool to calculate a conservation score for each position in the alignment. Identify:

- The fully conserved catalytic triad/residues.

- The consensus amino acid for every position.

- Target Identification:

- CbD Sites: Note any positions where the target enzyme has a different amino acid from the consensus, particularly those near the active site.

- Active Site Consensus: Compare the target's active site residues (e.g., oxyanion hole, substrate-binding pocket) to the consensus. Note any discrepancies as high-priority targets.

Protocol 2: Site-Directed Mutagenesis for Consensus Mutations

This protocol outlines the steps for introducing identified consensus mutations into the target gene via site-directed mutagenesis (SDM).

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Plasmid DNA: Containing the wild-type gene of the target enzyme.

- Oligonucleotide Primers: Designed to be complementary to the target region but incorporating the desired mutation(s).

- High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase: For PCR amplification (e.g., PfuUltra).

- Restriction Enzyme (DpnI): For digesting the methylated template DNA post-PCR.

- Competent E. coli Cells: For transformation of the mutagenesis reaction product.

Procedure:

- Primer Design: Design forward and reverse primers that are complementary to the target site and contain the desired nucleotide change(s) in the center. The primers should typically be 25-45 bases long with a melting temperature (Tm) ≥ 78°C.

- PCR Amplification: Set up a PCR reaction using the wild-type plasmid as a template and the mutagenic primers. Use a high-fidelity polymerase to minimize the introduction of random errors.

- Template Digestion: Add DpnI restriction enzyme directly to the PCR product and incubate for 1-2 hours. DpnI specifically cleaves the methylated parental DNA template, leaving the newly synthesized, mutated DNA strand intact.

- Transformation: Transform the DpnI-treated DNA into competent E. coli cells and plate onto selective agar medium.

- Verification: Pick resulting colonies, culture them, and isolate plasmid DNA. Verify the presence of the desired mutation by DNA sequencing.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for an MSA-driven enzyme engineering campaign.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MSA-Based Engineering

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Trimer Phosphoramidites [31] | An equimolar mix of trimeric phosphoramidites coding for optimal codons. Used in oligo synthesis for mutagenesis to avoid skewed amino acid representation and rare/stop codons in libraries. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Essential for error-free amplification during site-directed mutagenesis to ensure only the desired mutations are introduced. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Selectively digests the methylated parental DNA template after PCR, enriching for the newly synthesized mutant strand in the transformation step. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrates | Enable high-throughput screening or facile assay of enzyme activity and enantioselectivity of generated mutants. |

| AlphaFold2/3 [29] | Provides reliable 3D structural models of the target enzyme and mutants, enabling visual inspection of the active site and the structural impact of consensus mutations. |

The rational design of enantioselectivity represents a cornerstone of modern molecular science, with profound implications for asymmetric synthesis, pharmaceutical development, and catalyst engineering. At its core, shape-complementarity engineering exploits precise steric interactions to differentiate between competing transition states, thereby controlling the stereochemical outcome of chemical and biological transformations. This approach has become indispensable for constructing chiral molecules with high precision, moving beyond traditional empirical methods toward computationally informed design.

The fundamental principle governing enantioselectivity hinges on the energy difference between diastereomeric transition states leading to enantiomeric products. By engineering molecular environments—whether in enzyme active sites or synthetic catalyst architectures—researchers can create steric barriers and binding pockets that preferentially stabilize one reaction pathway over another. The integration of advanced computational tools with structural biology and organic synthesis has accelerated the development of tailored systems exhibiting unprecedented stereocontrol, enabling access to enantiopure compounds through rational design rather than serendipitous discovery.

Computational Foundations for Enzyme Engineering

Structure-Based Enzyme Design

Rational computational enzyme design operates on the fundamental premise that protein structure dictates function [32]. This paradigm enables researchers to systematically engineer enantioselectivity by targeting specific residues that influence transition state stabilization. Structure-based approaches leverage detailed atomic-level understanding of enzyme mechanisms to redesign active sites for enhanced stereocontrol.

Key Methodologies and Protocols:

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Investigate conformational flexibility and identify residues controlling access to the active site. Protocol: Run 50-100 ns simulations using AMBER or GROMACS with explicit solvent models to sample enzyme conformational states [32].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations: Model reaction mechanisms and transition states. Protocol: Employ B3LYP/6-31G* level theory to calculate energy barriers for competing enantiomeric pathways [33].

- Rosetta Enzyme Design: Repurpose enzyme active sites for novel functions. Protocol: Use catalytic residue placement, sequence optimization, and backbone sampling algorithms to generate designed enzymes [32].

- Computer-Aided Directed Evolution of Enzymes (CADEE): Accelerate predictive enzyme engineering through transition state modeling and electrostatic preorganization calculations [32].

Recent advances have demonstrated the power of these approaches. For cytochrome P450 enzymes, computational redesign has enabled altered regioselectivity in C-H activation reactions. Through multiple sequence alignment and tunnel analysis, researchers identified three critical residues responsible for chemo- and regio-selectivity in terpene oxidation [34]. Single mutations (T338S and L398I) successfully redirected oxidation to different carbon positions, showcasing how minimal computational interventions can dramatically alter selectivity profiles.

Table 1: Computational Tools for Rational Enzyme Design

| Tool/Method | Primary Application | Key Features | Success Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Substrate positioning | Predicts binding orientations and interactions | L398I mutation in P450 rotated substrate, altering regioselectivity [34] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | Identify conserved motifs | Compares homologous enzymes to find key residues | Identification of N121 and S260 in imine reductase G-36 [34] |

| Rosetta Enzyme Design | De novo enzyme creation | Models catalytic residues and optimizes sequences | Creation of enzymes for non-biological reactions like Morita-Baylis-Hillman [32] |

| CADEE Framework | Directed evolution | Combines MD simulations with electrostatic modeling | Improved turnover numbers and stereoselectivity in designed variants [32] |

Sequence-Based and Data-Driven Approaches

When high-resolution structures are unavailable, sequence-based methods provide powerful alternatives for enzyme engineering. These approaches leverage the growing databases of protein sequences and functions to identify patterns correlating with enantioselectivity.

Experimental Protocol: Sequence-Based Enzyme Engineering