Rational Design vs. Directed Evolution: A Strategic Guide for Protein Engineering in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of rational design and directed evolution, the two dominant strategies in protein engineering.

Rational Design vs. Directed Evolution: A Strategic Guide for Protein Engineering in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of rational design and directed evolution, the two dominant strategies in protein engineering. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and practical applications of each approach. It delves into their respective advantages and limitations, offers guidance for troubleshooting and optimization, and examines how hybrid strategies and emerging technologies like machine learning are forging the future of protein engineering for therapeutics and industrial biocatalysis.

Core Principles: Deconstructing Rational Design and Directed Evolution

In the field of protein engineering, scientists employ sophisticated methodologies to design and optimize proteins for therapeutic, diagnostic, and industrial applications. The two predominant strategies—rational design and directed evolution—offer distinct pathways to protein optimization. Rational design represents the architect's approach, leveraging detailed structural knowledge to make precise, calculated changes to a protein's amino acid sequence. In contrast, directed evolution mimics natural selection through iterative rounds of mutation and screening. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, examining their principles, experimental protocols, and performance metrics to inform research and development decisions.

Core Principles and Methodological Comparison

At their foundation, rational design and directed evolution operate on different philosophical and technical principles, each with characteristic strengths and limitations.

Rational design is a knowledge-driven approach where researchers use detailed understanding of protein structure-function relationships to introduce specific, targeted changes. This method requires comprehensive structural data from techniques like X-ray crystallography and computer modeling, enabling precise predictions about how modifications will affect protein performance [1] [2]. The approach allows for targeted alterations that can enhance stability, specificity, or activity with relatively few experimental iterations.

Directed evolution, awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2018, harnesses Darwinian principles in a laboratory setting. This method involves creating diverse libraries of protein variants through random mutagenesis, followed by high-throughput screening or selection to identify variants with improved properties [3]. Unlike rational design, directed evolution does not require prior structural knowledge and can uncover non-intuitive, beneficial mutations that computational models might not predict [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Protein Engineering Approaches

| Characteristic | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Requirement | High (requires detailed structural information) | Low (no structural knowledge needed) |

| Mutagenesis Approach | Targeted (site-directed mutagenesis) | Random (epPCR, gene shuffling) |

| Theoretical Basis | Structure-function relationships | Darwinian evolution |

| Primary Advantage | Precision and control | Discovery of non-intuitive solutions |

| Primary Limitation | Dependent on available structural data | Resource-intensive screening |

| Best Suited For | Optimizing known functions, specific alterations | Exploring new functionalities, complex traits |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The implementation of rational design and directed evolution follows distinct experimental pathways, each with characteristic workflows and technical requirements.

Rational Design Methodology

The rational design workflow begins with obtaining high-resolution structural data of the target protein through methods such as X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy. Researchers then analyze the structure to identify key residues or regions influencing the target function or property. Using computational modeling and bioinformatics tools, they design specific amino acid substitutions predicted to enhance the desired characteristic [2].

The core experimental step involves site-directed mutagenesis, where precise changes are introduced into the protein's coding sequence. The mutated genes are then expressed, and the resulting protein variants are purified and characterized using relevant functional assays. This process is typically iterative, with structural analysis informing subsequent design cycles [2].

Directed Evolution Methodology

Directed evolution employs a fundamentally different workflow centered on creating diversity and selecting improved variants. The process begins with the creation of a diverse library of gene variants through:

- Error-Prone PCR (epPCR): A modified PCR protocol that reduces polymerase fidelity through manganese ions (Mn²⁺) and dNTP imbalances, introducing random mutations at a rate of 1–5 base mutations per kilobase [3].

- DNA Shuffling: Also known as "sexual PCR," this method fragments homologous genes with DNaseI and reassembles them through primerless PCR, recombining beneficial mutations from multiple parents [3].

- Site-Saturation Mutagenesis: A semi-rational approach that comprehensively explores all possible amino acid substitutions at predetermined target positions [3].

The critical second phase involves high-throughput screening or selection to identify improved variants from the library. This can involve plate-based assays using colorimetric or fluorometric substrates, growth-based selections where survival is linked to desired function, or sophisticated techniques like fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and phage display [3] [2]. Genes from improved variants are isolated and subjected to additional rounds of mutagenesis and screening until the desired performance level is achieved.

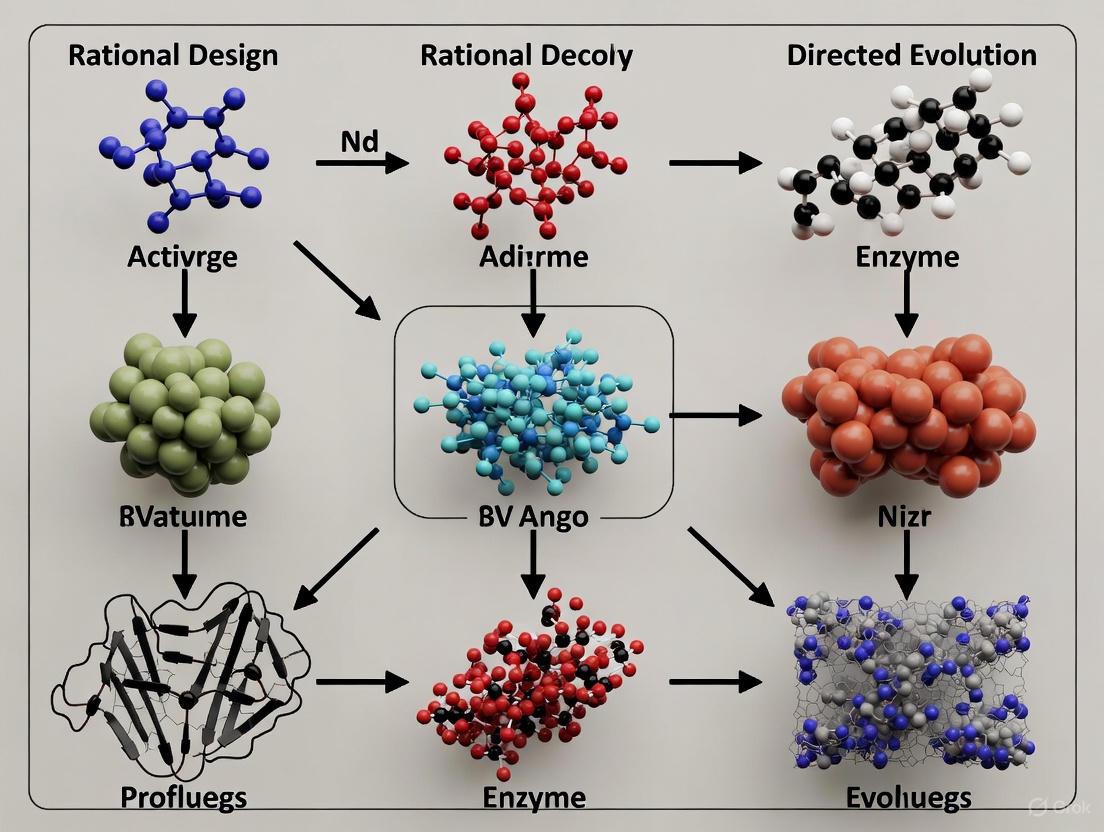

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows of rational design (yellow) and directed evolution (green) approaches to protein engineering.

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Both rational design and directed evolution have demonstrated success across various protein engineering applications, though with different performance characteristics and optimization efficiencies.

Rational design excels in applications where structural information is available and specific, well-understood modifications are required. In industrial enzyme engineering, rational design has successfully enhanced thermostability in α-amylase for food processing applications through targeted point mutations [2]. Similarly, therapeutic proteins like insulin have been optimized using site-directed mutagenesis to create fast-acting monomeric forms with improved pharmacokinetic properties [2].

Directed evolution demonstrates particular strength in optimizing complex traits and discovering novel functions. A notable application appears in engineering the protoglobin ParPgb for non-native cyclopropanation reactions. In this challenging landscape with significant epistatic interactions, directed evolution improved the yield of the desired product from 12% to 93% through iterative optimization of five active-site residues [4]. Similarly, directed evolution has generated alkaline proteases with enhanced activity at alkaline pH and low temperatures for detergent applications [2].

Table 2: Representative Experimental Outcomes from Protein Engineering Approaches

| Engineering Approach | Protein Target | Engineering Goal | Method Details | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational Design | α-amylase | Thermostability | Site-directed mutagenesis | Enhanced thermal stability for food processing [2] |

| Rational Design | Insulin | Pharmacokinetics | Site-directed mutagenesis | Fast-acting monomeric insulin [2] |

| Rational Design | CRISPR-Cas9 | Allosteric regulation | Domain insertion (ProDomino) | Light- and chemically-regulated genome editing [5] |

| Directed Evolution | Alkaline proteases | Activity at alkaline pH | Random mutagenesis | High activity at alkaline pH and low temperatures [2] |

| Directed Evolution | ParPgb protoglobin | Cyclopropanation yield | Active learning-assisted directed evolution (ALDE) | Yield improvement from 12% to 93% for desired product [4] |

| Directed Evolution | 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimate-3-phosphate synthase | Herbicide tolerance | Error-prone PCR | Enhanced kinetic properties and glyphosate tolerance [2] |

The Emergence of Integrated and Machine Learning-Enhanced Approaches

Contemporary protein engineering increasingly leverages hybrid strategies that combine elements of both rational design and directed evolution, enhanced by machine learning algorithms.

Semi-rational design represents a middle ground, using computational analysis and bioinformatic data to identify promising target regions for focused mutagenesis. This approach creates smaller, higher-quality libraries than fully random methods, increasing the frequency of beneficial variants while still exploring sequence space beyond purely rational predictions [2].

Machine learning-guided protein engineering has emerged as a transformative advancement. Techniques like ProDomino use machine learning trained on natural domain insertion events to predict optimal sites for domain recombination, enabling the creation of allosteric protein switches with high success rates (~80%) [5]. Similarly, active learning-assisted directed evolution (ALDE) combines Bayesian optimization with high-throughput screening to navigate epistatic fitness landscapes more efficiently than standard directed evolution [4].

Another innovative approach uses deep learning models that require minimal experimental data—as few as 24 characterized mutants—to guide protein engineering. This method successfully improved green fluorescent protein (avGFP) and TEM-1 β-lactamase function, with 5-65% and 2.5-26% of computational designs showing improved performance, respectively [6].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Successful implementation of protein engineering methodologies requires specific reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential materials and their applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Engineering Approaches

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Directed Evolution | Introduces random mutations throughout gene sequence during amplification [3] |

| DNase I Enzyme | Directed Evolution | Fragments genes for DNA shuffling and recombination experiments [3] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Rational Design | Enables precise, targeted amino acid changes in protein coding sequences [2] |

| Phage Display System | Directed Evolution | Links genotype to phenotype for screening protein-binding interactions [2] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Directed Evolution | Enables high-throughput screening of large variant libraries based on fluorescence [2] |

| Non-natural Amino Acids | Rational Design | Expands chemical functionality beyond the 20 canonical amino acids [2] |

| Crystallography Reagents | Rational Design | Enables structural determination for informed target selection [2] |

Rational design and directed evolution represent complementary rather than competing approaches in the protein engineering toolkit. Rational design serves as the architect's precise instrument, ideal when comprehensive structural data exists and targeted modifications are required. Its efficiency and precision make it valuable for therapeutic protein optimization and industrial enzyme engineering. Directed evolution functions as an exploratory discovery engine, capable of optimizing complex traits and identifying non-intuitive solutions without requiring detailed structural knowledge.

The most advanced protein engineering initiatives increasingly transcend this historical dichotomy, integrating structural insights, evolutionary principles, and machine learning predictions. These hybrid approaches leverage the strengths of both methodologies while mitigating their individual limitations. As computational power increases and experimental throughput advances, the distinction between rational and evolutionary approaches will likely continue to blur, leading to more efficient and effective protein engineering pipelines across biomedical and industrial applications.

In the fields of biotechnology and drug development, engineering biological molecules to exhibit novel or enhanced functions is a fundamental challenge. Two primary philosophies have emerged to meet this challenge: rational design and directed evolution. While rational design relies on detailed structural knowledge and predictive computational models to make precise, targeted changes, directed evolution (DE) mimics the process of natural selection in a laboratory setting to steer proteins or nucleic acids toward a user-defined goal [7]. This guide provides a objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their operational principles, experimental protocols, and performance in practical applications.

Directed evolution functions as an iterative, empirical algorithm that does not require a priori knowledge of a protein's three-dimensional structure or its catalytic mechanism [3]. Its power lies in exploring vast sequence landscapes through random mutation and functional screening, often uncovering highly effective and non-intuitive solutions that would not be predicted by computational models or human intuition [3]. The profound impact of this approach was recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Frances H. Arnold for her pioneering work in establishing directed evolution as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology [3].

Core Principles and Comparative Framework

The Fundamental Divide in Approach

The conceptual divide between rational design and directed evolution stems from their underlying strategies for navigating protein sequence space.

Rational Design operates on a principle of deductive prediction. It requires in-depth knowledge of the protein structure, as well as its catalytic mechanism [7]. Specific changes are then made by site-directed mutagenesis in an attempt to change the function of the protein based on hypotheses about sequence-structure-function relationships [8]. The success of this approach is often limited by the complexity of these relationships, which are difficult to predict accurately, even with advanced computational models [9].

Directed Evolution, in contrast, operates on a principle of empirical selection. It harnesses the principles of Darwinian evolution—iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection—within a laboratory setting [10] [3]. This approach compresses geological timescales into weeks or months by intentionally accelerating the rate of mutation and applying unambiguous, user-defined selection pressure [3]. The process does not attempt to predict which mutations will be beneficial; instead, it relies on high-throughput experimental methods to find them.

Table 1: Core Philosophical and Practical Differences Between Rational Design and Directed Evolution

| Aspect | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Deductive, knowledge-based prediction | Empirical, selective pressure-based screening |

| Knowledge Requirement | High (requires detailed structure & mechanism) | Low (requires only a functional assay) |

| Primary Advantage | Precise, targeted changes; avoids large libraries | Bypasses need for mechanistic understanding; discovers non-obvious solutions |

| Primary Limitation | Limited by accuracy of structure-function predictions | Requires a high-throughput assay; can be labor-intensive |

| Handling of Epistasis | Can be difficult to model and predict | Automatically accounts for epistatic (non-additive) effects |

The Directed Evolution Workflow Cycle

The directed evolution cycle functions as a two-part iterative engine, driving a population of protein variants toward a desired functional goal [3]. This process consists of two fundamental steps performed repeatedly: first, the generation of genetic diversity to create a library of protein variants, and second, the application of a high-throughput screen or selection to identify the rare variants exhibiting improvement [10] [7]. The following diagram illustrates this continuous cycle.

Experimental Protocols in Directed Evolution

Step 1: Library Creation – Generating Genetic Diversity

The first and foundational step is creating a diverse library of gene variants. The quality and nature of this diversity directly constrain the potential outcomes of the entire evolutionary campaign [3]. Common methods include:

Random Mutagenesis: This approach introduces mutations across the entire gene. The most established method is Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) [3]. This technique is a modified PCR that intentionally reduces the fidelity of the DNA polymerase by using factors such as a non-proofreading polymerase, unbalanced dNTP concentrations, and manganese ions (Mn²⁺) to introduce errors during amplification [3]. The mutation rate is typically tuned to 1–5 base mutations per kilobase [3]. A limitation is that epPCR is not truly random; polymerase bias favors transition mutations, meaning that at any given amino acid position, epPCR can only access an average of 5–6 of the 19 possible alternative amino acids [3].

Recombination-Based Methods (Gene Shuffling): These techniques mimic natural sexual recombination by combining beneficial mutations from multiple parent genes. DNA Shuffling (or "sexual PCR"), involves randomly fragmenting one or more related parent genes with DNaseI, then reassembling the fragments in a primer-free PCR reaction [10] [3]. This template-switching results in crossovers, creating a library of chimeric genes [3]. Family Shuffling applies this protocol to a set of homologous genes from different species, accessing nature's standing variation to accelerate improvement [3]. A key limitation is the requirement for high sequence homology (typically >70-75%) between parent genes for efficient reassembly [3].

Semi-Rational and Focused Mutagenesis: This approach targets diversity to specific regions based on structural or functional knowledge, creating smaller, higher-quality libraries. Site-Saturation Mutagenesis is a powerful example, where a target codon is randomized to encode all 20 possible amino acids, allowing deep interrogation of a specific residue's role [9] [3]. This is often applied to "hotspots" identified from prior random mutagenesis or structural models [11].

Table 2: Key Methods for Generating Diversity in Directed Evolution

| Method | Key Feature | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR | Introduces random point mutations | Easy to perform; no prior knowledge needed | Mutagenesis bias (limited to ~5-6 amino acids per position) |

| DNA Shuffling | Recombines fragments of parent genes | Combines beneficial mutations; mimics natural evolution | Requires high sequence homology (>70-75%) |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Tests all amino acids at a chosen position | Comprehensive exploration of a specific site | Can only be applied to a limited number of positions |

Step 2: Screening & Selection – Identifying Improved Variants

This step is often the bottleneck in directed evolution and involves linking a variant's genetic code (genotype) to its functional performance (phenotype) [3] [7]. The power of the screening method must match the size of the library.

Screening vs. Selection: A critical distinction exists between these two approaches. Screening involves the individual evaluation of every library member for the desired property, often in a multi-well format using colorimetric or fluorogenic assays read by a plate reader [3] [7]. This provides quantitative data on every variant but has lower throughput. Selection establishes a system where the desired function is directly coupled to the survival or replication of the host organism (e.g., resistance to an antibiotic or production of a vital metabolite) [7]. Selections can handle immense library sizes (up to 10¹⁵ variants in in vitro systems) but can be difficult to design, prone to artifacts, and provide less quantitative information [3] [7].

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Platforms: Modern screening leverages automation and advanced instrumentation. Microtiter plate-based assays (96- or 384-well) allow for the quantitative measurement of enzyme activity using spectrophotometers or fluorometers [9]. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) is a very high-throughput method used when the evolved property can be linked to a change in fluorescence, such as when using a fluorogenic substrate [9]. Display techniques, like phage display, physically link the protein variant to its genetic code, allowing for efficient selection for binding affinity from large libraries [9] [7].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Outcomes from Directed Evolution Campaigns

Directed evolution has demonstrated remarkable success in optimizing proteins for industrial and therapeutic applications. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from several landmark studies.

Table 3: Experimental Data from Successful Directed Evolution Campaigns

| Target Protein | Engineering Goal | Method(s) Used | Key Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtilisin E [10] | Activity in organic solvent (DMF) | Error-prone PCR | 256-fold higher activity in 60% DMF after 3 rounds |

| β-Lactamase [10] | Antibiotic resistance (Cefotaxime) | DNA Shuffling | 32,000-fold increase in Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) |

| ParPgb Protoglobin [4] | Yield/selectivity for non-native cyclopropanation | Active Learning-assisted DE (ALDE) | Yield improved from 12% to 93%; high diastereoselectivity (14:1) |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens Esterase [11] | Enantioselectivity | Semi-rational (3DM analysis & SSM) | 200-fold improved activity and 20-fold improved enantioselectivity |

| Haloalkane Dehalogenase (DhaA) [11] | Catalytic Activity | Semi-rational (MD simulations & SSM) | 32-fold improved activity by restricting water access |

Case Study: Overcoming Epistasis with Machine Learning

A significant challenge for traditional directed evolution is epistasis, where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of other mutations, leading to rugged fitness landscapes that can trap evolution at local optima [4]. A recent study on engineering a protoglobin (ParPgb) for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction exemplifies this challenge and a modern solution.

- The Challenge: Single-site saturation mutagenesis at five active-site residues failed to yield significant improvements. Furthermore, recombining the best single-point mutants also failed, indicating strong negative epistasis [4]. This landscape is difficult for standard "greedy hill-climbing" DE.

- The Solution: Researchers employed Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE), a machine learning workflow that uses Bayesian optimization and uncertainty quantification to intelligently propose combinations of mutations to test in the wet lab [4].

- The Result: In just three rounds of ALDE, which explored only ~0.01% of the possible sequence space, the team optimized the enzyme, increasing the yield of the desired product from 12% to 93% with high stereoselectivity [4]. This demonstrates the power of integrating computational prediction with empirical screening to navigate complex fitness landscapes more efficiently than traditional DE.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful directed evolution relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for setting up a directed evolution pipeline.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Workflow | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random mutations during gene amplification. | Kits often use Taq polymerase (no proofreading) and include Mn²⁺ to reliably tune mutation rate. |

| DNase I | Randomly fragments genes for DNA shuffling experiments. | Used to create small fragments (100-300 bp) for the reassembly process. |

| NNK Degenerate Codon Primers | For site-saturation mutagenesis to randomize a specific codon. | NNK (N=A/T/G/C; K=G/T) covers all 20 amino acids and one stop codon. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrate | Enables high-throughput screening in microtiter plates or via FACS. | The substrate must produce a detectable signal (fluorescence/color) upon reaction. |

| Phage Display Vector | Links the expressed protein variant to its genetic code on a phage coat. | Essential for selection-based campaigns for binding affinity (e.g., antibodies). |

| In Vitro Transcription/Translation Kit | For cell-free expression of protein libraries, enabling larger library sizes. | Bypasses the bottleneck of cellular transformation, allowing libraries >10¹². |

While this guide has focused on delineating the methodologies of rational design and directed evolution, the current state of the art in protein engineering increasingly blurs the lines between them. The most effective strategies often involve semi-rational or combinatorial approaches [11] [7]. Focused libraries, which concentrate diversity on regions informed by evolutionary analysis (e.g., consensus sequences) or structural insights, create smaller, higher-quality libraries that are more likely to contain improved variants [11]. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning and high-throughput measurements is revolutionizing directed evolution, making it a more predictive and precise engineering discipline [12] [4] [13]. By leveraging large datasets from deep mutational scanning, ML models can now help predict functional outcomes, guiding library design and variant selection to accelerate the entire engineering cycle [4] [13]. Ultimately, the choice between rational design and directed evolution is not binary; they are complementary tools in the molecular engineer's arsenal, both aimed at harnessing the power of evolution to create biological solutions to some of science's most pressing challenges.

The journey from Sol Spiegelman's groundbreaking experiments with a self-replicating RNA molecule to the awarding of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Frances H. Arnold for directed evolution represents a profound transformation in biological engineering. This timeline marks the shift from observing molecular evolution to actively harnessing its principles. Spiegelman's work in the 1960s demonstrated that RNA molecules could evolve under selective pressure in a test tube, providing the conceptual foundation for what would become directed evolution—a methodology that now enables researchers to engineer proteins with novel functions without requiring complete structural knowledge. The 2018 Nobel Prize formally recognized this paradigm shift, cementing directed evolution as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, with applications spanning pharmaceutical development, sustainable chemistry, and biofuel production [14] [3].

Section 1: Spiegelman's RNA and the Foundations of EvolutionIn Vitro

In the 1960s, Sol Spiegelman and his team conducted what became known as the "Spiegelman's Monster" experiment, which demonstrated Darwinian evolution in a test tube. Using an RNA-replicating system from the bacteriophage Qβ, they showed that RNA molecules could evolve into simpler, faster-replicating forms when subjected to selective pressure over multiple generations.

Experimental Protocol: Qβ Replication System

- System Preparation: The experiment utilized an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (replicase) isolated from the Qβ bacteriophage, along with nucleotides and necessary salts in a test tube environment [14].

- Serial Transfer Technique: After each round of replication, a portion of the RNA product was transferred to a fresh tube containing new replicase and nucleotides. This created sequential generations of selective pressure favoring faster replication [14].

- Evolutionary Outcome: Over 74 transfers, the original ~4,500-nucleotide Qβ RNA genome evolved into a vastly different, highly optimized replicator of only ~550 nucleotides. This "monster" had shed genes unnecessary for replication in the experimental environment, demonstrating that evolution favors genotypes with the greatest reproductive efficiency under prevailing conditions [14].

Spiegelman's work had a powerful impact on molecular biology theory. His development of DNA-RNA hybridization became a core component of many subsequent DNA technologies. His team's isolation of a viral enzyme used to make in-vitro copies of viral RNA was described by contemporary press as creating "life in a test tube," generating significant scientific excitement [14].

Section 2: The Rise of Directed Evolution as an Engineering Tool

Directed evolution matured from a novel academic concept into a transformative protein engineering technology, systematically applying the principles of natural evolution in a laboratory setting. The profound impact of this approach was formally recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Frances H. Arnold for her pioneering work [3].

Unlike rational design approaches that require detailed a priori knowledge of protein structure and mechanism, directed evolution harnesses iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection to tailor proteins for specific applications. This forward-engineering process can bypass the limitations of rational design by exploring vast sequence landscapes through mutation and functional screening, frequently uncovering non-intuitive and highly effective solutions that computational models or human intuition would not predict [3].

Table 1: Core Principles of Laboratory-Directed Evolution

| Principle | Natural Evolution | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Diversity Generation | Random mutations, genetic recombination | Intentional mutagenesis (epPCR, DNA shuffling, saturation mutagenesis) |

| Selection Pressure | Environmental fitness for survival and reproduction | User-defined functional screening or selection |

| Time Scale | Millions of years | Weeks to months |

| Primary Objective | Adaptation to environment | Optimization of specific protein properties |

The Directed Evolution Cycle

The directed evolution workflow functions as a two-part iterative engine, compressing geological timescales into practical timeframes for laboratory research [3]:

- Library Creation: Generating genetic diversity to create a library of protein variant sequences.

- Screening/Selection: Applying high-throughput screening or selection to identify rare improved variants.

This cycle repeats, with genes from the best variants serving as templates for subsequent rounds of evolution, allowing beneficial mutations to accumulate until desired performance targets are met [3].

Section 3: Methodological Framework and Comparison with Rational Design

The successful application of directed evolution relies on sophisticated methodologies for creating diversity and identifying improved variants. The choice between random and targeted approaches represents a key strategic consideration.

Table 2: Protein Engineering Methodologies: Directed Evolution vs. Rational Design

| Aspect | Directed Evolution | Rational Design |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Requirement | Requires no detailed structural or mechanistic knowledge | Relies on comprehensive 3D structural and mechanistic understanding |

| Diversity Approach | Explores vast sequence space through random or semi-random mutagenesis | Targets specific residues predicted to influence function |

| Library Size | Very large (10^6 - 10^12 variants) | Small, focused libraries |

| Key Advantage | Discovers non-intuitive solutions; requires minimal prior knowledge | Efficient when structural insights are accurate and complete |

| Primary Limitation | Requires robust high-throughput screening; can be labor-intensive | Limited by accuracy of structural predictions and current knowledge |

Key Techniques in Directed Evolution

Genetic Diversification Methods:

- Error-Prone PCR (epPCR): A modified PCR protocol that intentionally reduces DNA polymerase fidelity through manganese ions (Mn²⁺), nucleotide imbalances, and use of non-proofreading polymerases. This introduces random base substitutions throughout the gene, typically at a rate of 1–5 mutations per kilobase [3] [15].

- DNA Shuffling: Also known as "sexual PCR," this method mimics natural recombination by fragmenting parent genes with DNaseI and reassembling them through primer-less PCR. Fragments from different templates prime each other, creating chimeric genes with novel mutation combinations [3].

- Site-Saturation Mutagenesis: A semi-rational approach that comprehensively explores all 19 possible amino acid substitutions at one or a few targeted positions, often "hotspots" identified from prior random mutagenesis or structural analysis [3].

Screening and Selection Strategies:

- Growth-Coupled High-Throughput Selection (GCHTS): Establishes a direct link between enzyme activity and host cell survival, enabling screening of up to 10^9 variants based on cell growth. Strategies include detoxification (survival in toxic environments), auxotroph complementation (compensating for essential gene deletions), and reporter-based systems (linking activity to antibiotic resistance) [15].

- Yeast Surface Display: A platform for both characterizing and evolving proteins, where variants are displayed on the yeast cell surface and labeled with fluorescent probes for analysis by flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [16].

- Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution (PACE): An automated system that combines continuous mutagenesis and selection in a single process, significantly accelerating evolutionary timelines by eliminating manual intervention between generations [15].

Diagram 1: Directed Evolution Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of diversity generation and screening that drives protein optimization.

Section 4: Case Studies in Contemporary Directed Evolution

Case Study 1: Engineering an RNA-Reactive HUH Tag

Researchers successfully engineered a protein for sequence-specific, covalent conjugation to RNA through directed evolution, starting from a natural enzyme (HUH tag) that reacts only with single-stranded DNA [16].

Experimental Protocol:

- Yeast Display Platform: The 13.3 kD HUH protein was fused to Aga2p for yeast surface display with a C-terminal myc tag for detection [16].

- Library Construction: Error-prone PCR created an initial library with an average of 1-2.3 amino acid changes per gene and a size of ~1.2×10^8 variants [16].

- Staggered Selection: Due to initially undetectable RNA reactivity, evolution began using DNA-RNA hybrid substrates. The first generation used a probe with 9 RNA nucleotides (r9 hybrid), with successive generations transitioning to pure RNA probes [16].

- Progressive Stringency: Over 7 generations, selection pressure increased by progressively decreasing RNA probe concentration from 2 μM to 1 nM and replacing Mn²⁺ with Mg²⁺ to match cellular conditions [16].

- Outcome: The final evolved variant (rHUH) contained 12 mutations and formed covalent bonds with a 10-nucleotide RNA sequence within minutes at nanomolar concentrations, enabling applications in RNA labeling, imaging, and editing [16].

Case Study 2: Directed Evolution of Hydrocarbon-Producing Enzymes

Directed evolution faces unique challenges when applied to engineer enzymes that produce aliphatic hydrocarbons, which are often insoluble, gaseous, and chemically inert, making detection in vivo difficult [17].

Experimental Challenges and Solutions:

- Detection Limitations: Unlike enzymes producing chromogenic or fluorescent products, hydrocarbon-producing enzymes like OleTJE (a cytochrome P450 that decarboxylates fatty acids to alkenes) require specialized detection methods including gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), which is low-throughput [17].

- Growth-Coupling Strategies: Successful evolution campaigns have relied on engineering selection systems where hydrocarbon production is linked to cell survival, such as by complementing auxotrophs or regulating essential gene expression [17] [15].

- Biosensor Integration: Genetically encoded biosensors that transcribe antibiotic resistance genes in response to hydrocarbon production enable survival-based selection, allowing screening of large variant libraries without specialized equipment [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Directed Evolution

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Material | Function in Directed Evolution |

|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random mutations throughout the target gene during amplification |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Non-proofreading polymerase essential for error-prone PCR protocols |

| Manganese Chloride (MnCl₂) | Critical component for reducing DNA polymerase fidelity in error-prone PCR |

| DNase I | Enzyme used to fragment genes for DNA shuffling and recombination |

| Auxotrophic Bacterial Strains | Host cells with deleted essential genes for growth-coupled selection systems |

| Yeast Display System | Platform for protein surface display and screening via FACS |

| Fluorescent-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Instrument for high-throughput screening of yeast or bacterial display libraries |

| Microtiter Plates (96/384-well) | Platform for high-throughput screening of variant libraries in cell lysates |

| Reporter Plasmids | Vectors containing antibiotic resistance or fluorescent protein genes for selection |

The intellectual pathway from Spiegelman's RNA evolution experiments to the formal recognition of directed evolution with a Nobel Prize illustrates a fundamental transition in life science methodology—from observation to engineering. Where Spiegelman demonstrated that evolution could be observed and studied in a test tube, modern directed evolution actively guides this process to solve real-world problems. While these approaches have traditionally been viewed as distinct alternatives, contemporary protein engineering increasingly employs hybrid strategies that combine the exploratory power of directed evolution with the precision of structure-informed rational design. This synergy continues to expand the boundaries of synthetic biology, enabling the development of novel enzymes for sustainable fuel production, therapeutic agents, and environmentally friendly industrial processes that were unimaginable in Spiegelman's era [3] [17].

Structural Knowledge for Rational Design vs. High-Throughput Assays for Directed Evolution

In the field of protein engineering, rational design and directed evolution represent two fundamentally distinct methodologies for creating proteins with enhanced or novel functions. Rational design operates like an architect, relying on detailed structural knowledge to make precise, premeditated changes to a protein's amino acid sequence. In contrast, directed evolution mimics natural selection in laboratory settings, employing high-throughput screening (HTS) assays to sift through vast libraries of random variants for those with desirable traits [1]. The choice between these approaches significantly impacts research strategy, resource allocation, and experimental outcomes. This guide provides an objective comparison of their core requirements, focusing specifically on the structural information needed for rational design and the assay technologies that enable directed evolution.

Core Requirements: A Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes the key differences in requirements and methodologies between rational design and directed evolution.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Rational Design and Directed Evolution

| Aspect | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Core Requirement | Detailed structural knowledge of the target protein [1] | High-throughput screening or selection assays [1] [9] |

| Primary Data Input | Protein structure (X-ray, Cryo-EM), computational models, sequence-function relationships [1] [11] | Library of genetic variants (mutagenic or recombinatory) [9] |

| Knowledge Dependency | High; requires prior understanding of structure-function relationships [1] [11] | Low; can proceed without prior structural knowledge [1] [9] |

| Experimental Workflow | Targeted modifications → Expression → Characterization | Library Creation → HTS/Selection → Characterization → Iteration [9] |

| Mutational Basis | Specific, pre-determined mutations based on hypothesis [1] | Random mutations or recombinations, beneficial ones identified post-screening [1] [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Rational Design: A Structure-Driven Workflow

The rational design pipeline is iterative and heavily reliant on computational and structural biology data.

- Structure Determination and Analysis: The process begins with obtaining a high-resolution structure of the target protein via X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy. Researchers analyze this structure to identify active sites, binding pockets, and regions critical for stability and function [11].

- Computational Modeling and In Silico Design: Using molecular modeling software (e.g., MOE, Rosetta), scientists predict which amino acid substitutions, insertions, or deletions might confer the desired property. This often involves simulating how these changes affect protein dynamics, stability, and interactions with substrates [11].

- Targeted Mutagenesis: Based on the computational predictions, a limited set of specific variants is created using techniques like site-directed mutagenesis or site-saturation mutagenesis. This results in a small, focused library of candidates [11].

- Expression and Functional Characterization: The designed variants are expressed, purified, and characterized using biochemical assays to validate the functional outcome of the mutations.

A specific application is illustrated in the engineering of a Ras-activating enzyme (SOS1). Researchers used an ensemble structure-based virtual screening approach to identify small molecules that could disrupt the SOS1-Ras interaction. This rational method started with structural knowledge of the catalytic pocket to select 418 candidate compounds from a library of 350,000, which were then experimentally screened to find inhibitors [19] [20].

Directed Evolution: A Screening-Driven Workflow

Directed evolution relies on creating diversity and using high-throughput assays to find improved variants, often without requiring structural data.

- Library Generation: A diverse library of protein variants is created through random mutagenesis techniques (e.g., error-prone PCR) or in vitro recombination methods (e.g., DNA shuffling) that mimic natural sexual recombination [9] [18].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS) or Selection: This is the critical step that substitutes for structural knowledge. Massive libraries are screened using assays designed to report on the desired function. Common methods include:

- Microtiter Plate-Based Assays: Utilizing colorimetric or fluorimetric readouts in 96-, 384-, or 1,536-well plates to measure enzymatic activity [21]. For example, a colorimetric assay was developed to screen for inhibitors of α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR) by monitoring the formation of 2,4-dinitrophenolate [21].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): An ultra-high-throughput method used to screen cell-surface displayed libraries based on binding affinity or enzymatic activity, enabling the processing of millions of variants in a short time [9].

- Display Technologies: Methods like phage display link the protein variant (phenotype) to its genetic code (genotype), allowing for iterative selection based on binding properties [9].

- Hit Isolation and Iteration: Improved variants identified in the screen are isolated, and their genes are sequenced. This process is typically repeated for multiple rounds, accumulating beneficial mutations to achieve significant functional gains [9].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The successful implementation of either protein engineering strategy depends on a specific toolkit of reagents and platforms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Rational Design and Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 3DM Database & HotSpot Wizard | Computational analysis of protein superfamilies to identify evolutionarily allowed mutations and functional hotspots [11]. | Rational & Semi-Rational Design |

| RosettaDesign & MOE Software | Molecular modeling suites for predicting the impact of amino acid substitutions on protein structure and stability [11]. | Rational Design |

| Error-Prone PCR & DNA Shuffling Kits | Commercial kits for introducing random point mutations or recombining homologous genes to create diverse variant libraries [9] [18]. | Directed Evolution |

| Fluorescent/Colorimetric Assay Substrates | Chemically designed substrates that produce a detectable signal (color, fluorescence) upon enzymatic conversion, enabling HTS [9] [21]. | Directed Evolution (HTS) |

| Phage or Yeast Display Systems | Platforms for displaying protein variants on the surface of viruses or cells, linking phenotype to genotype for easy selection [9]. | Directed Evolution (Selection) |

| FACS Instrumentation | Hardware for sorting millions of individual cells based on fluorescence, a key enabler for ultra-high-throughput screening [9]. | Directed Evolution (HTS) |

Workflow and Logical Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core decision-making and experimental workflows for both rational design and directed evolution.

Logical Pathway for Method Selection

This diagram outlines the key decision points when choosing between rational design and directed evolution.

Directed Evolution High-Throughput Screening Workflow

This diagram details the iterative cycle of directed evolution, highlighting the central role of HTS.

Rational design and directed evolution are complementary pillars of modern protein engineering. Rational design offers precision and deep mechanistic insight but is constrained by the necessity for extensive structural knowledge. In contrast, directed evolution is a powerful discovery engine that leverages high-throughput assays to find solutions within random diversity, often without requiring a priori structural data. The choice between them is not merely technical but strategic, dictated by the specific project goals and available resources. As the field advances, the most successful strategies often integrate both approaches, using rational design to inform library construction and directed evolution to explore unforeseen possibilities, thereby accelerating the development of novel enzymes, therapeutics, and biomaterials [22] [12] [11].

Methodologies in Action: Techniques and Real-World Applications

The field of protein engineering is defined by two dominant, complementary paradigms: rational design and directed evolution. Rational design employs computational and structure-based insights to make precise, targeted changes to a protein's sequence. In contrast, directed evolution harnesses the principles of natural selection—creating large, diverse libraries of variants and screening for improved function—often without requiring prior structural knowledge [3]. For years, these approaches were viewed as distinct philosophies, each with its own strengths and limitations. Directed evolution is powerful for optimizing complex properties like stability or catalytic efficiency without needing a complete mechanistic understanding, but it can require screening immense libraries [3]. Classical rational design is efficient and targeted but has been constrained by the limits of our predictive understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships.

The modern protein engineering landscape, however, is increasingly characterized by the synergistic integration of these methodologies [23]. This guide focuses on two foundational techniques—site-directed mutagenesis and saturation mutagenesis—that are central to this fusion. Once considered tools primarily for the rational design toolkit, they are now strategically deployed within directed evolution campaigns and supercharged by machine learning (ML). This comparison will objectively analyze their performance, protocols, and applications, framing them within the broader thesis of rational design versus directed evolution. We will demonstrate that the distinction between these paradigms is blurring, with the combined approach driving the most significant recent advances in biotechnology, therapeutics, and enzyme engineering [23] [24] [22].

Technical Comparison of Mutagenesis Methods

The following table provides a structured comparison of the core mutagenesis techniques, highlighting their distinct roles in the engineering workflow.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Protein Engineering Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Typical Library Size | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Introduces a single, predefined amino acid change at a specific residue. | Individual variant | - Mechanistic studies (e.g., alanine scanning) [3]- Fine-tuning known active sites- Correcting or introducing specific traits | High precision; simple experimental analysis; ideal for hypothesis testing. | Explores a minimal sequence space; requires prior knowledge of function. |

| Saturation Mutagenesis | Systematically replaces a single residue with all 19 other possible amino acids. | ~20 variants per site (theoretical) | - Exploring individual residue flexibility [3]- Hot-spot optimization identified from initial screens [3]- Interrogating active sites or epistatic networks | Comprehensively explores a single position; bridges rational and random approaches. | Does not explore combinatorial effects across multiple sites. |

| Random Mutagenesis (e.g., epPCR) | Introduces random mutations across the entire gene. | (10^4)-(10^6) variants [3] | - Initial discovery campaigns for beneficial mutations [3]- When no structural or mechanistic data is available | Requires no prior knowledge; can discover non-intuitive solutions. | Heavily biased (e.g., favors transitions); vast majority of mutations are neutral or deleterious [3]. |

| Machine Learning-Guided Design | Uses models trained on fitness data to predict beneficial higher-order mutants. | (10^2)-(10^5) in silico variants, followed by smaller experimental testing [24] [25] | - Navigating high-dimensional sequence space [24]- De novo protein generation [25]- Predicting epistatic interactions | Dramatically reduces experimental burden; enables prediction of complex variants. | Requires large, high-quality training datasets; computational complexity [24]. |

Quantitative Performance and Experimental Data

The true test of any engineering method lies in its experimental outcomes. The table below summarizes quantitative results from recent studies that leverage saturation mutagenesis, often integrated with ML, for enzyme and protein optimization.

Table 2: Summary of Experimental Performance from Recent Studies

| Engineering Goal / Target System | Experimental Approach | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improve Amide Synthetase (McbA) Activity | ML-guided saturation mutagenesis of 64 active site residues (1216 variants), followed by ridge regression model prediction. | ML-predicted variants showed 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity for nine different pharmaceutical compounds compared to the wild-type enzyme. | [24] |

| Enhance Protease (ZH1) Thermostability | AI pipeline (Omni-Directional Mutagenesis) generating 100,000 mutants, with screening based on the "Barrel Theory" weak-point ranking. | 62.5% of experimentally tested protease mutants showed increased thermostability. | [25] |

| Increase Lysozyme (G732) Bacteriolytic Activity | AI pipeline generating 100,000 mutants, with screening based on weak-point ranking and biological indicators. | 50% of experimentally tested lysozyme mutants displayed increased bacteriolytic activity. | [25] |

| Engineer Allosteric Protein Switches | ProDomino ML model predicting domain insertion sites, validated in E. coli and human cells. | Achieved ~80% success rate for creating functional, light- and chemically-regulated switches for CRISPR-Cas systems. | [5] |

The data in Table 2 underscores a critical trend: the standalone use of saturation mutagenesis is being eclipsed by its use as a data-generating engine for machine learning. In the amide synthetase study, the initial saturation mutagenesis of 64 sites (1,216 variants) provided the sequence-function data necessary to train a predictive model. This model successfully identified multi-point mutants with drastically improved activity, a feat difficult to achieve by screening alone [24]. Similarly, the "Barrel Theory" ranking method used for the protease and lysozyme demonstrates a novel computational strategy to prioritize which variants from a massive in silico library are most likely to be functional, thereby increasing the success rate of experimental validation [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Saturation Mutagenesis for Machine Learning

This protocol, adapted from a machine-learning-guided platform for enzyme engineering, is designed for rapidly generating large sequence-function datasets [24].

- Library Design (Hot Spot Identification): Select target residues for saturation based on structural data (e.g., within 10 Å of the active site or substrate tunnel) to create a focused but comprehensive library.

- Cell-Free DNA Assembly:

- Use PCR with primers containing a nucleotide mismatch to introduce the desired mutation.

- Digest the parent plasmid with DpnI to eliminate the methylated template.

- Perform an intramolecular Gibson Assembly to form the circular mutated plasmid.

- Template Preparation: Use a second PCR to amplify linear DNA expression templates (LETs) from the assembled plasmids. This step avoids the need for laborious bacterial transformation and cloning.

- Cell-Free Protein Expression (CFE): Express the mutated protein variants directly using a cell-free gene expression system.

- High-Throughput Functional Assay: Test the expressed variants for the desired activity (e.g., catalytic efficiency, substrate specificity) in a microtiter plate format. The platform enabled the evaluation of 1,217 enzyme variants in 10,953 unique reactions [24].

- Data for Machine Learning: The resulting dataset of sequence-performance pairs is used to train supervised machine learning models (e.g., augmented ridge regression) for predicting higher-performance variants.

Protocol 2: Traditional Site-Saturation Mutagenesis for Hypothesis Testing

This classic protocol is used for deeply characterizing individual residues or optimizing known hotspots [3].

- Primer Design: Design oligonucleotide primers where the target codon is replaced with an NNK degenerate sequence (N = A/T/G/C; K = G/T). This mixture encodes all 20 amino acids and includes a single stop codon.

- PCR Amplification: Perform a standard PCR using a high-fidelity, non-proofreading polymerase to amplify the entire plasmid using the degenerate primers.

- Template Digestion: Treat the PCR product with DpnI, which specifically cleaves methylated parental DNA, enriching for the newly synthesized, mutated DNA.

- Transformation: Transform the digested PCR product into competent E. coli cells, which repair the nicks in the circular DNA.

- Screening & Sequencing: Screen individual colonies for the presence of the insert and sequence them to identify the specific amino acid at the target position. This confirms library diversity.

- Functional Characterization: Express and purify the unique variants and assay them for the function of interest to build a profile of the target residue's mutability.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the modern, integrated protein engineering workflow that combines rational design, saturation mutagenesis, and machine learning, as exemplified by the cited studies.

Figure 1: Integrated Protein Engineering Workflow. This diagram shows the synergy between rational design, high-throughput experimentation, and machine learning in modern protein engineering.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and their functions essential for executing the high-throughput saturation mutagenesis protocols described in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Modern Mutagenesis Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Degenerate Primers (NNK) | Encodes all 20 amino acids at a single target codon during PCR. | The NNK codon reduces stop codon frequency compared to NNN [3]. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests the methylated parent plasmid template post-PCR, enriching for newly synthesized mutated DNA. | Critical for reducing background in site-directed and saturation mutagenesis [3]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis System | Enables rapid in vitro expression of protein variants without the need for live cells, drastically increasing throughput. | Used to express 1,216 enzyme variants within a day for ML training [24]. |

| High-Throughput Assay Reagents | Allows for quantitative measurement of protein function (e.g., activity, stability) in microtiter plate formats. | Colorimetric or fluorometric substrates readable by a plate reader are essential for gathering high-integrity data [3]. |

| Machine Learning Models | Computational tools that predict protein fitness from sequence data, guiding the design of subsequent libraries. | Includes fine-tuned protein BERT models [25] and ridge regression models trained on experimental data [24]. |

The classical dichotomy between rational design and directed evolution is no longer a productive framework for understanding the state of the art in protein engineering. As this guide has demonstrated, techniques like saturation mutagenesis are pivotal connectors between these worlds. They provide the targeted, quantitative data that powers machine learning models, which in turn predict multi-point mutants that navigate the fitness landscape more effectively than iterative screening alone [23] [24] [25].

The future of the field lies in continued integration. Rational design provides the initial structural hypotheses and constraints. Saturation mutagenesis and other high-throughput methods generate deep, localized fitness data. Finally, machine learning synthesizes this information to reveal complex sequence-performance relationships and propose new, high-performing variants, effectively closing the DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) loop. This synergistic toolbox—exemplified by breakthroughs in enzyme engineering [24], AAV capsid design [22], and allosteric switch creation [5]—is accelerating the development of specialized proteins for therapeutics, diagnostics, and industrial biotechnology at an unprecedented pace.

In the ongoing comparison of protein engineering strategies, directed evolution stands as a powerful, empirical counterpart to rational design. While rational design relies on precise knowledge of structure-function relationships to make targeted changes, directed evolution mimics natural selection by generating vast genetic diversity and screening for improved function [10]. This approach is particularly valuable when a protein's structure is unknown or the mechanisms underlying its function are poorly understood, as it requires no a priori structural knowledge [10]. Two foundational methods for creating this diversity are error-prone PCR (epPCR) and DNA shuffling. Since its landmark demonstration in the evolution of subtilisin E, directed evolution has become an indispensable tool for creating proteins with enhanced stability, altered substrate specificity, and novel functions [10]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these core techniques, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select and implement the optimal strategy for their protein engineering goals.

Error-Prone PCR (epPCR): Principles and Protocols

Core Principle and Mechanism

Error-prone PCR is a method for introducing random point mutations throughout a gene of interest. It modifies standard PCR conditions to reduce the fidelity of the DNA polymerase, thereby increasing the rate at which incorrect nucleotides are incorporated during amplification [26] [27]. The mutation frequency can be controlled by the experimenter and typically ranges from 0.11% to 2%, equating to 1 to 20 nucleotide changes per 1 kilobase of DNA [28]. This technique is most effective for exploring a wide mutational landscape near a parent sequence, making it ideal for the initial stages of evolution to improve properties like solubility or enzymatic activity [29] [26].

Standard Experimental Protocol

A typical epPCR protocol involves careful preparation of a specialized reaction mixture and thermal cycling. The table below summarizes a standard reagent setup and the function of each component [28].

Table 1: Standard Reagent Setup for an Error-Prone PCR Reaction

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 10X epPCR Buffer | 1X | Provides optimal reaction conditions (pH, salts). |

| MgCl₂ | ~7 mM | Stabilizes non-complementary base pairs, increasing error rate. |

| dNTP Mix | Variable (e.g., 0.2-0.5 mM each) | Nucleotide building blocks; biased ratios enhance errors. |

| MnCl₂ | ~0.5 mM | Significantly reduces polymerase fidelity, a key mutagenic agent. |

| Forward & Reverse Primers | 30 pmol each | Binds ends of the target gene for amplification. |

| Template DNA | ~2 fmol (~10 ng of an 8-kb plasmid) | The gene sequence to be mutated. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | 1-2.5 U | Low-fidelity enzyme that catalyzes DNA synthesis. |

| Water | To final volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) | Adjusts volume and reagent concentrations. |

The thermal cycling program generally follows these steps [28]:

- Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 2-3 minutes.

- Cycling (35-50 cycles):

- Denaturation: 92-94°C for 15-60 seconds.

- Annealing: Temperature specific to primers (e.g., 60-68°C) for 20-60 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C (1 minute per 1 kb of gene length).

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

Overcoming Biases and Limitations

A critical consideration in epPCR is its inherent mutational bias. The technique does not produce a perfectly random library due to three main factors [27]:

- Error Bias: The polymerase has preferred misincorporation patterns (e.g., A to G transitions might be more common than C to T).

- Codon Bias: Because the genetic code is degenerate, a single nucleotide change can only access a subset of possible amino acids. Reaching others requires two or three simultaneous mutations, which is statistically less likely.

- Amplification Bias: Some sequences may amplify more efficiently than others during PCR.

To mitigate these biases, researchers can use specialized polymerases or kits (e.g., Stratagene's GeneMorph system) with different error profiles, or combine epPCR with other mutagenesis methods [27]. Furthermore, the cloning step after epPCR can significantly limit library complexity. Traditional ligation-dependent cloning is inefficient, but modern methods like Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning (CPEC) can dramatically improve the number of variants captured. One study found CPEC superior to traditional methods for cloning a DsRed2 gene library generated by epPCR [30].

Figure 1: Error-Prone PCR Workflow. The gene of interest is amplified under low-fidelity conditions, cloned into an expression vector, and screened for desired traits.

DNA Shuffling: Principles and Protocols

Core Principle and Mechanism

DNA shuffling, also known as molecular breeding, is an in vitro random recombination method that fragments multiple parent genes and reassembles them to create a library of chimeric progeny [31]. Introduced by Willem P.C. Stemmer in 1994, its key advantage is the ability to combine beneficial mutations from different sequences while simultaneously removing deleterious ones [31] [10]. This process is analogous to sexual recombination and is especially powerful for evolving complex properties that require multiple cooperative mutations or for recombining homologous genes from different species [10].

Primary Methodologies

DNA shuffling can be performed through several procedures, each with distinct advantages.

Table 2: Comparison of DNA Shuffling Techniques

| Method | Key Reagent | Procedure Summary | Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Breeding (Classical) | DNase I | 1. Fragment genes with DNase I.2. Reassemble fragments without primers in a PCR-like reaction.3. Amplify full-length chimeras with primers. | Advantage: Efficient homologous recombination.Disadvantage: Requires high sequence similarity between parents. |

| Restriction Enzyme-Based | Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | 1. Digest parent genes with enzymes that have common restriction sites.2. Ligate fragments together. | Advantage: No PCR required; control over crossover points.Disadvantage: Dependent on common restriction sites. |

| NExT DNA Shuffling | dUTP, Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase, Piperidine | 1. Amplify genes with dUTP/dTTP mix.2. Excise uracil bases and cleave backbone.3. Reassemble fragments. | Advantage: Rational, reproducible fragmentation; low error rate.Disadvantage: Uses toxic reagent (piperidine). [32] |

| Staggered Extension (StEP) | DNA Polymerase | 1. Perform PCR with very short extension steps.2. Nascent fragments repeatedly anneal to different templates. | Advantage: Simple, single-tube reaction. [10]Disadvantage: Can be difficult to optimize. |

Standard Experimental Protocol

The classical DNA shuffling protocol by Stemmer involves the following key steps [31]:

- Fragmentation: The parent genes (e.g., homologs or mutant sequences) are digested with DNase I in the presence of Mn²⁺ to generate random double-stranded fragments of 10-50 base pairs to over 1 kbp.

- Reassembly: The fragments are purified and subjected to a primer-less PCR. In this step, fragments with homologous regions anneal to each other and are extended by a DNA polymerase. Repeated cycles of annealing and extension reassemble the fragments into full-length chimeric genes.

- Amplification: Standard primers are added to the reaction to amplify the newly formed, full-length hybrid genes via a conventional PCR. This method was famously used to evolve a β-lactamase with a 32,000-fold increase in resistance to the antibiotic cefotaxime, far exceeding the improvement achieved with non-recombinogenic methods [10].

Figure 2: DNA Shuffling Workflow. Multiple parent genes are fragmented and reassembled, creating a library of hybrid sequences.

Comparative Analysis and Selection Guide

The choice between error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling depends on the starting material, the desired outcome, and the project stage.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Error-Prone PCR and DNA Shuffling

| Parameter | Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | DNA Shuffling |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Diversity | Point mutations (substitutions, small insertions/deletions). | Recombination of existing sequences; creates chimeras. |

| Primary Input | A single parent gene. | Multiple parent genes (homologs or pre-evolved mutants). |

| Mutation Rate | Controllable, typically 1-20 mutations/kb. [28] | Lower inherent rate, but combines large sequence blocks. |

| Best Application | Early rounds: exploring local sequence space, improving solubility, stability. [29] [10] | Later rounds: combining beneficial mutations, propagating improvements from different homologs. [31] [10] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, requires only one starting sequence. | Can rapidly combine beneficial mutations from different parents. |

| Main Limitation | Limited to point mutations; biased mutational spectrum. [27] | Requires sequence homology or common restriction sites for most methods. [31] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these directed evolution workflows relies on a set of core reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Workflow | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Low-fidelity polymerase for standard epPCR. | Introducing random mutations in a target gene. [28] |

| Stratagene GeneMorph or Clontech Diversify Kits | Commercial kits for controlled, high-efficiency random mutagenesis. | Generating a library with a specific, predictable mutation rate. [27] [30] |

| DNase I | Enzyme for random fragmentation of DNA in classical shuffling. | Creating a pool of fragments for recombination from parent genes. [31] |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (e.g., BsaI) | Enzymes that cut outside their recognition site for Golden Gate Assembly. | Facilitating ligation-free, modular cloning of shuffled libraries. [28] |

| Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase | Enzyme used in NExT DNA shuffling to excise uracil bases. | Creating defined fragmentation points for recombination. [32] |

| Gateway Technology | System for highly efficient cloning of PCR products. | Transferring epPCR libraries into expression vectors with minimal background. [29] |

| CPEC (Circular Polymerase Extension Cloning) | A ligation-independent cloning method. | Efficiently capturing a larger diversity of epPCR variants compared to traditional cloning. [30] |

Both error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling are cornerstone techniques in the directed evolution workflow, each addressing a distinct need. Error-prone PCR excels as a starting point, efficiently generating a cloud of point mutants around a single parent sequence to uncover initial improvements. DNA shuffling acts as a powerful follow-up, capable of recombining these improvements from multiple optimized variants or homologous genes to achieve synergistic effects that are inaccessible through point mutations alone. The strategic selection and sequential application of these methods, often within an iterative cycle of diversification and screening, enables researchers to navigate the vast fitness landscape of proteins and solve complex challenges in biotechnology, therapeutics, and enzyme engineering.

In the pursuit of linking genotype to phenotype—a central challenge in modern biology and drug discovery—two distinct methodological paradigms have emerged: High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and Powerful Selection Systems. These approaches differ fundamentally in their underlying philosophy and implementation. HTS operates as a measurement-driven, parallel analysis tool, systematically testing individual library members against a target or cellular assay [33] [34]. In contrast, selection systems are enrichment-driven, employing a Darwinian process where a functional output, such as survival or binding, is directly linked to the amplification of the corresponding genotype [35] [36]. This comparison is intrinsically linked to the broader thesis of rational design versus directed evolution; HTS often provides the quantitative data necessary for informed design, while selection systems directly implement evolutionary principles to discover functional variants. The choice between them shapes the entire experimental strategy, from library design to hit identification.

Core Principles and Technological Evolution

High-Throughput Screening (HTS)

HTS is a cornerstone of drug discovery and functional genomics, enabling the parallel testing of hundreds of thousands of compounds or genetic perturbations in a short time. The core principle involves miniaturized assays (e.g., in 384- or 1536-well microplates), automation and robotics for liquid handling, and detection systems (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence) to measure a specific biochemical or cellular response [33] [37]. A key metric for assay quality is the Z'-factor (0.5–1.0 indicates an excellent assay), which reflects robustness and reproducibility [37]. The trend has been toward extreme miniaturization and automation; whereas early HTS used 96-well plates, it now routinely uses 1536-well plates and even 3456-well formats, with typical assay volumes ranging from 5 μL down to 1–2 μL [33] [34]. This miniaturization, coupled with advanced detection chemistries, allows for the screening of vast chemical or genomic libraries to identify "hits" that modulate a target of interest.

Powerful Selection Systems

Selection systems, often embodied in display technologies and in-vivo survival assays, directly couple a desired phenotypic function to the gene that encodes it. The fundamental principle is enrichment through iterative rounds of selection for a specific function, such as binding, catalysis, or cell survival [35] [36]. Unlike HTS, which measures all library members individually, selection systems impose a functional sieve; only variants possessing the desired activity are propagated. This is powerfully exemplified by technologies like phage display, yeast display, and more recently, the ORBIT bead display, which multiplexes peptides and their encoding DNA on the surface of beads for functional selection [35]. In microbial systems, a mixed library can be grown under selective pressure (e.g., antibiotic presence), and the resulting enrichment of resistant genotypes is tracked via deep sequencing to quantify fitness [36]. These systems are exceptionally powerful for sifting through immense sequence spaces to find functional needles in a haystack.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of HTS and Selection Systems, highlighting their strategic differences.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of HTS and Selection Systems

| Characteristic | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Powerful Selection Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Parallel measurement of individual library members [33] [34]. | Functional enrichment linking phenotype to genotype amplification [35] [36]. |

| Primary Readout | Quantitative signal (e.g., fluorescence, absorbance, cell count). | Enrichment of specific genotypes after selection. |

| Typical Library Size | 10,000 to >1,000,000 compounds/variants [33] [34]. | Can be extremely large (>1010 in emulsion-based systems) [35]. |

| Throughput | Defined as data points per day (e.g., 10,000-100,000 for HTS; >100,000 for UHTS) [33]. | Defined by the number of selection rounds and the diversity of the starting library. |

| Key Advantage | Generates rich, quantitative data for each sample; well-suited for dose-response and mechanistic studies [37]. | Can access extremely large libraries and identify rare, functional clones without complex instrumentation. |

| Key Limitation | Throughput is physically limited by automation and miniaturization; lower functional density in libraries [11]. | Provides less quantitative information on negatives; can be biased by amplification efficiency and non-functional binders. |

| Cost & Infrastructure | High initial investment in robotics, detectors, and reagent management systems [33] [34]. | Often lower infrastructure cost, but requires expertise in molecular biology and library construction. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A Typical HTS Workflow for Biochemical Target Screening

The following diagram illustrates the standardized, parallel process of a typical HTS campaign.

Detailed Protocol:

- Assay Development & Miniaturization: A biochemical assay, such as an enzyme activity measurement, is developed and miniaturized to a 384-well or 1536-well microplate format. Key validation metrics like the Z'-factor are calculated to ensure robustness [37].

- Compound Library Preparation: Libraries of small molecules, which can be general or target-family focused (e.g., kinase libraries), are stored in plates compatible with the automated system [37].

- Automated Liquid Handling & Incubation: A centralized robotic system equipped with a gripper moves microplates around a platform. Dispensing modules add assay reagents, enzymes, and compounds to the plates, which are then incubated [33].

- Signal Detection: The plates are transferred to a detector (e.g., a fluorescence plate reader) to measure the signal generated by the assay. Homogeneous detection methods like Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) are often used for efficiency [33].

- Data Analysis: The raw data is processed. Compounds that produce a signal statistically significantly different from controls are designated as "hits." These are typically confirmed in a dose-response secondary screen to calculate IC50 values [33] [37].

A Typical Workflow for a Bead-Based Selection System

The following diagram outlines the iterative enrichment process of a bead-based selection system, such as ORBIT display.

Detailed Protocol (ORBIT Bead Display) [35]: