Substrate Inhibition in Enzyme Kinetics: From Foundational Mechanisms to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive examination of substrate inhibition, a prevalent phenomenon affecting approximately 25% of all known enzymes where catalytic activity decreases at high substrate concentrations.

Substrate Inhibition in Enzyme Kinetics: From Foundational Mechanisms to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of substrate inhibition, a prevalent phenomenon affecting approximately 25% of all known enzymes where catalytic activity decreases at high substrate concentrations. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational mechanistic theories and kinetic models to advanced analytical methods for parameter determination. It further addresses practical challenges in experimental systems and industrial bioreactors, explores emerging validation techniques, and discusses the critical implications of these kinetics for the accurate prediction of in-vivo drug metabolism and the design of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Unraveling the Mechanisms: The What and Why of Substrate Inhibition

Fundamental Concepts: FAQs on Substrate Inhibition

Q1: What is substrate inhibition? Substrate inhibition is a common deviation from Michaelis-Menten kinetics in which the velocity of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction rises to a maximum as substrate concentration increases but then descends at higher substrate concentrations. This descent may either approach zero (complete inhibition) or a non-zero asymptote (partial inhibition) [1].

Q2: What is the key difference between complete and partial substrate inhibition? The fundamental difference lies in the catalytic capability of the enzyme-substrate-inhibitor complex (ES₁S₂):

- Complete Inhibition: The ES₁S₂ complex is non-productive and cannot generate any product (k' = 0). The reaction velocity eventually decreases to zero at very high substrate concentrations [1].

- Partial Inhibition: The ES₁S₂ complex breaks down to form product at a reduced rate compared to the enzyme-substrate complex (ES₁). The reaction velocity descends to a non-zero plateau (k'/k < 1) [1].

Q3: What is the general mechanism behind this phenomenon? The simplest explanation involves the binding of two substrate molecules to the enzyme: one at the active (catalytic) site and another at a separate non-catalytic (inhibitory) site, forming a ternary ES₁S₂ complex that is either inactive or less active [1] [2].

Troubleshooting Guides for Experimental Analysis

Problem: Determining Inhibition Type from Kinetic Data

Symptoms: Your initial rate data shows a clear peak in velocity at a specific substrate concentration, but you are unsure if the inhibition is complete or partial.

Solution:

- Plot your data as ( v/(V_{max} - v) ) versus ( 1/[S] ) for the higher, inhibitory substrate concentrations [1].

- Interpret the plot:

Problem: Overcoming Substrate Inhibition in Bioreactor Cell Cultures

Symptoms: High substrate concentration in your bioreactor is leading to reduced cell growth rates and decreased product yields, potentially due to osmotic issues, viscosity, or inefficient oxygen transport [3].

Solution:

- Switch to Fed-Batch Operation: Instead of adding all substrate at the beginning, continuously feed it into the inoculum. This maintains the substrate concentration at a level that supports growth without triggering inhibition [3].

- Alternative Strategies:

- Use Two-Phase Partitioning Bioreactors: A second phase can store excess substrate, releasing it based on metabolic demand [3].

- Immobilize Cells: Encapsulating cells in a protective matrix can create a barrier against inhibitory substrate concentrations [3].

- Increase Biomass Concentration: Supporting cells on a scaffold to form a biofilm can reduce the per-cell impact of the inhibitor [3].

Kinetic Parameter Estimation

The following equations and parameters are essential for characterizing substrate inhibition. The Haldane equation is a common model for uncompetitive substrate inhibition [2] [3].

Fundamental Kinetic Equation (Uncompetitive Inhibition): [ v = \frac{V{max} \cdot [S]}{Km + [S] + \frac{[S]^2}{K_i}} ] Where:

- ( v ): Initial reaction velocity

- ( V_{max} ): Maximal velocity

- ( [S] ): Substrate concentration

- ( K_m ): Michaelis constant

- ( K_i ): Substrate inhibition constant

Summary of Key Kinetic Parameters:

| Parameter | Description | Significance in Complete vs. Partial Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| ( K_m ) | Michaelis constant; approximates the dissociation constant of the ES complex. | Fundamental to both types; determined from data at low, non-inhibitory [S]. |

| ( K_i ) | Substrate inhibition constant; dissociation constant for the inhibitory ES₁S₂ complex. | A lower ( K_i ) indicates inhibition occurs at a lower [S]. Relevant for both types. |

| ( k' / k ) | Ratio of the rate constant for product formation from ES₁S₂ vs. ES₁. | Critical differentiator. ( k' / k = 0 ) for complete inhibition; ( 0 < k' / k < 1 ) for partial inhibition [1]. |

| ( [S]_{m} ) | Substrate concentration at which the maximal velocity (( v_{max} )) is observed. | Calculated for uncompetitive inhibition as ( [S]m = \sqrt{Km \cdot K_i} ) [2]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and tools are fundamental for studying substrate inhibition kinetics.

Key Reagents for Kinetic Studies:

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Analysis | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Haldane (Andrews) Model | Mathematical model to fit kinetic data and estimate ( V{max} ), ( Km ), and ( K_i ) under inhibiting conditions. | Used to model hydrogen production inhibition in dark fermentation and phenol biodegradation [2] [3]. |

| Quotient Velocity Plot (( v/(V_{max}-v) ) vs ( 1/[S] )) | A graphical method to distinguish between complete and partial inhibition and determine the ( k'/k ) ratio [1]. | Applied in the analysis of E. coli phosphofructokinase II inhibition by ATP [1]. |

| Nonlinear Regression Software | Software tools for fitting complex kinetic models (e.g., Haldane) to experimental data to obtain accurate parameter estimates. | Curve fitting performed with KaleidaGraph and Python in myoglobin peroxidase activity studies [4]. |

| External Electron Donors (e.g., ABTS) | Used in studies of pseudo-peroxidase activity to monitor reaction rates and probe inhibition mechanisms. | ABTS oxidation monitored at 730 nm to study substrate inhibition in myoglobin and hemoglobin [4]. |

Advanced Technical Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Analyzing Substrate Inhibition of a Purified Enzyme

Objective: To determine the type of substrate inhibition and calculate the kinetic parameters ( Km ), ( Ki ), and ( k'/k ).

Materials:

- Purified enzyme

- Substrate

- Assay buffers

- Spectrophotometer or instrument for measuring initial rates

Procedure:

- Initial Rate Measurements: Measure the initial velocity (v) of the reaction over a wide range of substrate concentrations [S]. Ensure you include enough data points both before and after the observed activity peak.

- Estimate ( V{max} ): From a double-reciprocal or nonlinear fit of the data at low, non-inhibitory substrate concentrations, obtain an initial estimate of ( V{max} ) [1].

- Diagnostic Plot: Create a plot of ( v/(V_{max} - v) ) versus ( 1/[S] ), using only the data from the higher, inhibitory substrate concentrations [1].

- Determine Inhibition Type:

- Observe where the linear regression of the data from Step 3 intercepts the y-axis.

- Origin Intercept: Suggests complete inhibition.

- Positive Y-intercept: Suggests partial inhibition. The intercept value is ( (k'/k)/(1 - k'/k) ), from which ( k'/k ) can be calculated [1].

- Calculate ( Ki ): Using the value of ( k'/k ) from Step 4, the ( Ki ) (or ( K_{Si}' )) can be determined from the slope of the same plot [1].

- Global Curve Fitting: For a more robust estimation, fit the full dataset to the appropriate equation using nonlinear regression software. For uncompetitive inhibition, use the Haldane equation [2] [3] [4].

Prevalence and Biological Significance in Metabolic Regulation

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs on Substrate Inhibition in Enzyme Kinetics

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Substrate Inhibition in Experimental Data

Problem: My enzyme activity decreases at high substrate concentrations. How do I confirm this is substrate inhibition?

- Step 1 – Visual Inspection: Plot your initial reaction velocity (V₀) against substrate concentration ([S]). A hallmark sign of substrate inhibition is a curve that rises to a peak and then declines with increasing [S], instead of plateauing as in standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics [5].

- Step 2 – Model Fitting: Fit your data to the substrate inhibition model [6] [7]: ( V0 = \frac{V{\max} \cdot [S]}{Km + [S] + \frac{[S]^2}{Ki}} ) A good fit to this model, yielding a finite inhibition constant (Kᵢ), confirms substrate inhibition.

- Step 3 – Control Experiments: Perform Selwyn's test to ensure the enzyme is stable during the assay time and that the loss of activity is not due to enzyme denaturation [7].

Problem: The standard fitting procedure for my inhibition constants (Kᵢc and Kᵢu) is imprecise and requires too many experiments. What can I do?

- Solution: Implement the IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) [8]. This modern method can precisely estimate inhibition constants using a single, well-chosen inhibitor concentration, drastically reducing experimental workload.

- Protocol:

- First, determine the IC₅₀ value (the inhibitor concentration that gives 50% control activity) using a substrate concentration near the Kₘ.

- Then, measure initial velocities using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC₅₀ (e.g., 2x IC₅₀) across a range of substrate concentrations.

- Fit this reduced dataset to the mixed inhibition model, incorporating the known IC₅₀ value into the fitting algorithm for greater accuracy [8].

- Protocol:

Problem: Substrate inhibition is limiting the product yield in my whole-cell biocatalytic process. How can I mitigate this?

- Solution 1 – Enzyme Engineering: Use structure-guided engineering to create enzyme variants with reduced substrate inhibition. For example, mutations in the substrate access tunnels or active site of L-aspartate-α-decarboxylase (PanD) have successfully enhanced substrate tolerance and increased β-alanine production yields [9].

- Solution 2 – Process Optimization: Use fed-batch strategies to maintain the substrate concentration in the reactor below the inhibitory threshold. This avoids the irreversible inactivation observed in some enzymes like PanD at high substrate levels [9].

- Solution 3 – Use of Effectors: Some competitive inhibitors can paradoxically reactivate a substrate-inhibited enzyme. For instance, β-carotene alleviates strong substrate inhibition in the glucosyltransferase NbUGT72AY1 [10]. Screening for such effectors can be a viable strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental mechanism behind substrate inhibition? A1: The classical mechanism involves the binding of a second substrate molecule to the enzyme-substrate (ES) complex, forming an unproductive ternary complex (ESS) that slows down the reaction [6] [11]. Recent studies have also revealed unusual mechanisms where the substrate binds to the enzyme-product (EP) complex, physically blocking product release [11].

Q2: How common is substrate inhibition, and does it have biological relevance? A2: Substrate inhibition occurs in approximately 20-25% of all known enzymes [11] [10]. It is not an artifact but a crucial metabolic regulation mechanism. A classic example is the inhibition of phosphofructokinase by high ATP levels, which helps regulate glycolysis and ATP production [11].

Q3: My progress curve shows a rapid initial rate that then slows down. Is this always substrate inhibition? A3: Not necessarily. This pattern can also be caused by product inhibition. To distinguish between them, fit your time-course data to the integrated rate equations for both phenomena [7]. If adding initial product to the reaction mixture further slows the initial rate, product inhibition is likely involved.

Q4: Are there computational tools to help model and fit substrate inhibition kinetics? A4: Yes, software like the Enzyme Kinetics app for OriginPro provides built-in functions to fit data to various inhibition models, including substrate inhibition [12]. Using such tools ensures accurate parameter estimation based on robust numerical methods.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Kinetic Parameters under Substrate Inhibition

- Experimental Design: Use a wide range of substrate concentrations, ensuring you have sufficient data points both before and after the expected activity peak. A Bayesian optimal design approach suggests spacing substrate concentrations around the prior Kₘ estimate and its multiples to minimize parameter variance [13].

- Initial Rate Measurements: For each [S], measure the initial linear rate of product formation or substrate consumption. Ensure less than 5-10% substrate conversion to avoid significant product inhibition interference [7].

- Data Fitting: Fit the collected (V₀, [S]) data pairs to the substrate inhibition equation using nonlinear regression software. The fitted parameters will be V_max, Kₘ, and Kᵢ.

Protocol 2: A Single-Time-Point Method for High-Throughput Screening

This is advantageous when substrate is expensive or assays are time-consuming [7].

- Incubation: Incubate enzyme with substrate for a single, sufficiently long time period (t), allowing for a large proportion (e.g., 50-60%) of the substrate to be converted.

- Measurement: Measure the final product concentration [P].

- Calculation: Use the integrated form of the rate equation to solve for parameters: ( V \cdot t = [P] + \frac{[S]0^2 - [S]^2}{2Ki} + Km \cdot \ln\left(\frac{[S]0}{[S]}\right) ) where [S] = [S]₀ - [P]. This can be fitted directly to time-course data from a single initial substrate concentration.

Quantitative Data on Substrate Inhibition

Table 1: Summary of Substrate Inhibition Constants (Kᵢ) from Various Enzymes

| Enzyme | Source | Substrate | Inhibition Constant (Kᵢ) | Biological/Industrial Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucosyltransferase (NbUGT72AY1) [10] | Nicotiana benthamiana | Scopoletin | Exhibits strong inhibition | Plant defense mechanism; inhibition can be reversed by β-carotene. |

| L-Aspartate-α-decarboxylase (PanD) [9] | Bacillus subtilis | L-Aspartate | >80% activity loss at 50 g/L | Limits industrial production of β-alanine; targeted by enzyme engineering. |

| Haloalkane Dehalogenase (LinB L177W) [11] | Engineered Variant | Haloalkane | Strong inhibition observed | Engineered tunnel mutation caused unusual inhibition via enzyme-product complex. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Chart for Common Experimental Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Activity decline at high [S] | Substrate Inhibition | Fit data to substrate inhibition model; check fit with F-test or AIC [12]. |

| Product Inhibition | Add product at t=0; if initial rate decreases, product is inhibitory [7]. | |

| Enzyme Denaturation | Perform Selwyn's test to check enzyme stability over time [7]. | |

| Poor precision in Kᵢ estimate | Sub-optimal [I] choice | Use the 50-BOA method with an inhibitor concentration > IC₅₀ [8]. |

| Insufficient data points | Use Bayesian design to select substrate concentrations around Kₘ [13]. | |

| Low product yield in bioreactor | Irreversible Substrate Inhibition | Switch to fed-batch operation to keep [S] below inhibitory level [9]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Studying Substrate Inhibition

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example & Note |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | The biocatalyst under investigation. | Wild-type vs. engineered variants (e.g., B. subtilis PanD for higher activity) [9]. |

| Substrate | The molecule converted by the enzyme. | Use high-purity grade. Prepare stock solutions at high concentration to avoid dilution artifacts. |

| Inhibitor/Effector | Molecule used to probe inhibition mechanism or alleviate inhibition. | e.g., β-carotene for NbUGT72AY1 [10]; specific inhibitors for metabolic studies. |

| Assay Buffers | Maintain optimal pH and ionic strength for enzyme activity. | Critical, as pH can influence inhibition (e.g., in anaerobic digestion) [14]. |

| Stopped-Flow or Rapid Kinetics Instrument | For measuring very fast initial reaction rates. | Essential for pre-steady-state kinetics to resolve individual catalytic steps [11]. |

| Software for Nonlinear Regression | To fit data to complex kinetic models and estimate parameters. | OriginPro with Enzyme Kinetics App [12]; custom scripts in MATLAB/R for 50-BOA [8]. |

Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

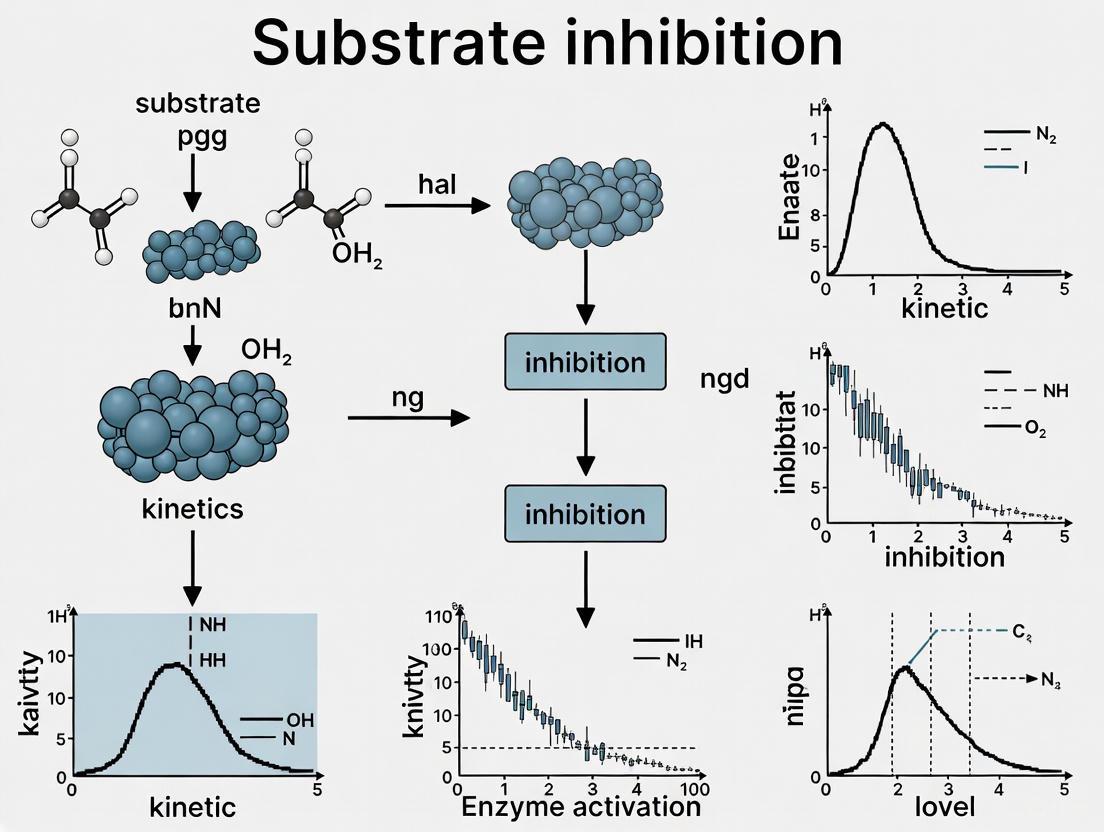

Diagram 1: Diagnosing substrate inhibition.

Diagram 2: Uncompetitive substrate inhibition mechanism.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Core Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Michaelis-Menten kinetics and the Haldane model for substrate inhibition?

A1: The key difference lies in the reaction mechanism and the resulting rate equation. The standard Michaelis-Menten model describes a hyperbolic increase in reaction rate with substrate concentration, approaching a maximum velocity ((V_{max})). In contrast, the Haldane model is a classical mechanistic model for substrate inhibition where the enzyme can bind two substrate molecules. The binding of the second substrate at a inhibitory site leads to the formation of a non-productive ternary complex (ES₂), which causes the reaction rate to decrease at high substrate concentrations. [15] [5] [16]

The equations governing these behaviors are:

- Michaelis-Menten: ( V = \frac{V{max}[S]}{Km + [S]} ) [5] [17]

- Haldane (Andrews) model: ( V = \frac{V{max}[S]}{Km + [S] + \frac{[S]^2}{K_I}} ) [5] [3]

Here, (KI) is the substrate inhibition constant. The term (\frac{[S]^2}{KI}) in the denominator is responsible for the decrease in velocity at high ([S]). [5] [3]

Q2: Under what condition does the Haldane model reduce to standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics?

A2: The Haldane model reduces to the Michaelis-Menten model when the substrate inhibition constant ((KI)) becomes infinitely large ((K{SS} \rightarrow \infty )). [15] This means the affinity of the substrate for the inhibitory site is effectively zero, eliminating the formation of the inactive ES₂ complex. This reduction can also occur when the catalytic efficiency of the ternary SES complex (in the Haldane-Radić mechanism) is identical to that of the binary ES complex (parameter b = 1). [15]

Q3: What is the biological significance of substrate inhibition?

A3: Substrate inhibition is not merely a kinetic anomaly but an important regulatory mechanism in biological systems. It allows an enzyme's activity to be modulated by the concentration of its own substrate, providing a feedback mechanism. For example, phosphofructokinase, a key enzyme in glycolysis, is inhibited by its substrate ATP. This ensures that glycolysis is slowed when the cell has ample energy, preventing unnecessary ATP production. [16] This mechanism is crucial for maintaining homeostasis in metabolic pathways. [5] [16]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Substrate Inhibition Studies

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No clear peak in rate; velocity plateaus but does not decrease | Substrate solubility limit is reached before inhibition becomes apparent. [5] | Verify substrate solubility. Use a more soluble substrate analog or different buffer system. Experimentally determine the full substrate concentration range. |

| High variability in rate measurements at inhibitory substrate concentrations | Non-ideal mixing or viscosity effects at high substrate concentrations leading to inaccurate rate measurements. [3] | Ensure proper agitation in batch experiments. Consider switching to a fed-batch system to maintain a lower, non-inhibitory substrate level in the bulk phase. [3] |

| Inability to fit data to the Haldane equation | The underlying mechanism may not be simple two-site binding, or the inhibition may be partial. [16] | Test other inhibition models (e.g., a generalized model for partial inhibition). [16] Re-examine assumptions about the enzyme's mechanism. |

| Cell growth inhibition in bioreactors at high substrate levels | Osmotic stress, viscosity, or inefficient oxygen transport due to high substrate concentration. [3] | Transition from batch to fed-batch operation to control substrate concentration. [3] Explore cell immobilization or use of Two Phase Partitioning Bioreactors. [3] |

Key Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol: Determining Kinetic Parameters with the Haldane Model

This protocol outlines the steps to obtain the substrate inhibition constants (Km), (V{max}), and (K_I) for an enzymatic reaction.

1. Experimental Setup and Initial Velocity Measurements:

- Prepare a fixed, low concentration of enzyme.

- Set up reactions with substrate concentrations ([S]) that span a wide range, from well below the expected (K_m) to concentrations that are high enough to clearly observe a decrease in reaction velocity. It is critical to have sufficient data points in the decreasing limb of the curve. [5]

- For each [S], measure the initial velocity ((v_0)) of the reaction, ensuring minimal substrate depletion (typically <5-10%). [17]

2. Data Fitting and Parameter Estimation:

- Use non-linear regression analysis to fit the collected data ((v0) vs. [S]) to the Haldane equation: ( v0 = \frac{V{max}[S]}{Km + [S] + \frac{[S]^2}{K_I}} )

- From the fit, the software will provide estimates for (V{max}), (Km), and (K_I).

3. Calculating the Optimum Substrate Concentration:

- For the classical Haldane model, the substrate concentration at which the reaction velocity is maximized ([S]) can be calculated from the estimated parameters: [16] ( [S]^ = \sqrt{Km \cdot KI} )

Advanced Protocol: A Generalized Model for Partial Inhibition

For cases where binding of the second substrate does not completely abolish activity, a more general model is required. This protocol is based on a generalized kinetic scheme. [16]

1. Mechanism: The enzyme can bind one (ES) or two (ES₂) substrate molecules, each with potentially different catalytic rate constants ((k{cat}) and (k'{cat})) and Michaelis constants ((K{1m}) and (K{2m})). [16]

2. Initial Velocity Equation: The initial velocity is given by: ( v0 = \frac{\frac{V1}{K{1m}}[S] + \frac{V2}{K{1m} K{2m}}[S]^2}{1 + \frac{1}{K{1m}}[S] + \frac{1}{K{1m} K{2m}}[S]^2} ) where (V1 = k{cat}[E]T) and (V2 = k'{cat}[E]_T). [16]

3. Condition for Substrate Inhibition: Substrate inhibition (a peak in the velocity curve) exists only if (V1 > V2). If (V2 > V1), the binding of the second substrate is activating and the velocity will asymptotically approach (V_2). [16]

4. Finding the Optimum [S]: If (V_1 > V_2), the optimum substrate concentration that yields the maximum velocity is: [16] ( [S]^ = \sqrt{\frac{K{1m} K{2m} (V1 - V2)}{V2 K{2m} - V1 K{1m}} } )

Table 2: Summary of Key Parameters in Substrate Inhibition Models

| Parameter | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| (K_m) | Michaelis constant for the first substrate binding event. [17] | Apparent affinity for the catalytic site. Lower (K_m) means higher affinity. |

| (K_I) | Substrate inhibition constant in the Haldane model. [5] [3] | Reflects affinity for the inhibitory site. A low (K_I) indicates strong inhibition. |

| (k{cat}) ((V1)) | Turnover number for the ES complex. [16] | Catalytic efficiency when one substrate is bound. |

| (k'{cat}) ((V2)) | Turnover number for the ES₂ complex. [16] | Catalytic efficiency when two substrates are bound. If (V_2=0), inhibition is complete. |

| [S]* | Optimal substrate concentration. | The concentration that yields the maximum reaction rate. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Substrate Inhibition Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Substrate | To ensure that observed kinetics are due to the substrate and not impurities. Critical for accurate (Km) and (KI) determination. |

| Recombinant Enzyme | Allows for controlled studies with minimal interference from other enzymatic activities, ideal for mutagenesis studies to probe binding sites. [15] |

| Buffers with Cofactors | Maintains optimal pH and provides essential cofactors (e.g., Mg²⁺, NADH) for enzymatic activity, ensuring accurate kinetic measurement. |

| Fed-Batch Bioreactor System | A key tool for overcoming substrate inhibition in industrial and cell-based applications by controlling substrate concentration at non-inhibitory levels. [3] |

| Numerical Fitting Software | Essential for performing non-linear regression to fit complex models like the Haldane and generalized equations to experimental data. |

Conceptual Diagrams and Workflows

Haldane Mechanism for Substrate Inhibition

Experimental Workflow for Kinetic Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Product Release Blockage in Enzyme Kinetics

Problem: Enzyme activity decreases at high substrate concentrations, and initial data suggests non-classical inhibition.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome | Key Parameters to Monitor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Confirm Inhibition Pattern | A plot of reaction rate (v) vs. substrate concentration ([S]) shows a distinct peak and then a decrease [2] [3]. | Maximum reaction rate (Vmax), optimal [S], inhibition constant (Ki) [3]. |

| 2 | Rule Out Classical Mechanisms | Initial rate analysis does not fit competitive, non-competitive, or uncompetitive models. Inhibition may be linked to the enzyme-product (EP) complex [11]. | Michaelis constant (Km), apparent Vmax; look for inconsistencies with standard models [11] [7]. |

| 3 | Test for Product Release | Direct measurement shows product formation stalls at high [S], even when the chemical step is complete. | Product concentration over time, halide ion release (for dehalogenases) [11]. |

| 4 | Investigate Tunnel Blockage | Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations show substrate molecules obstructing product exit pathways [11]. | Ligand positions in access tunnels, conformational flexibility of the protein [11]. |

| 5 | Implement Tunnel Engineering | A point mutation in an access tunnel (e.g., L177W in LinB) is introduced, or a suppressor mutation (e.g., I211L) is added to restore flux [11] [18]. | Catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km), level of substrate inhibition (Ki) [11]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Experimental Artifacts in Inhibition Studies

Problem: Unexpected inhibition or lack of expected activity in enzymatic assays.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Digestion/Restriction | Inhibition by contaminants (salt, solvents) from DNA purification or PCR [19]. | Clean up DNA (e.g., spin column) prior to digestion; ensure DNA volume is ≤25% of total reaction volume to dilute contaminants [19]. |

| No or Low Enzyme Activity | The enzyme is inhibited by Dam/Dcm/CpG methylation of its recognition site [19]. | Check enzyme's sensitivity to methylation; grow plasmid in a dam-/dcm- strain for methylation-sensitive enzymes [19]. |

| Extra Bands on Gel (Star Activity) | Altered specificity due to high glycerol concentration, too many enzyme units, or prolonged incubation [19]. | Use High-Fidelity (HF) enzymes; ensure glycerol concentration is <5%; use the minimum units and incubation time required [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between classical substrate inhibition and the mechanism of substrate blockage of product release?

Classical substrate inhibition is typically attributed to the formation of an unproductive enzyme-substrate complex, often when two substrate molecules bind simultaneously to the active site, as described by Haldane [11]. In contrast, the unconventional mechanism involves the binding of an excess substrate molecule to the enzyme-product (EP) complex, forming a dead-end ternary complex (SEP). This bound substrate physically blocks the exit tunnel, preventing the release of the product and halting the catalytic cycle [11] [18].

Q2: What experimental evidence can distinguish this mechanism from classical models?

A global kinetic analysis using transient-state methods, rather than just steady-state kinetics, is key. This approach can reveal that inhibition is tied to the EP complex rather than the free enzyme [11]. The most direct evidence comes from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and Markov state models (MSM), which can visually demonstrate how a substrate molecule occupies the access tunnel, thereby obstructing the product's path to the bulk solvent [11].

Q3: How can this form of inhibition be controlled or eliminated in laboratory experiments?

The most rational approach is tunnel engineering through targeted mutagenesis. As demonstrated in haloalkane dehalogenase LinB, a point mutation (L177W) that caused strong substrate inhibition by blocking the main tunnel could be suppressed by introducing a second mutation (I211L) in a different tunnel. This combination restored catalytic efficiency while reducing inhibition by opening an auxiliary pathway for product release [11] [18].

Q4: In a single time-point assay with high substrate conversion, how does product inhibition affect the accuracy of measured kinetic parameters?

Using the simple [P]/t ratio as a substitute for the initial rate (v) in the Michaelis-Menten equation can lead to systematic errors if product inhibition is present. While the apparent Vmax and Km values might still be reasonable, the determination of the product inhibition constant (Kp) is highly sensitive to even minor experimental errors (2-10%) and can yield unreliable results. For accurate parameter estimation, it is better to use the integrated rate equation that accounts for competitive product inhibition or to employ initial rate measurements [7].

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from the study on LinB dehalogenase, which detailed the mechanism of substrate blockage of product release [11].

| Parameter / Parameter Set | Wild-Type LinB | L177W Mutant | L177W/I211L Double Mutant | Notes / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Efficiency | Baseline | Decreased | Restored to High | Double mutant counteracts negative effects of single mutation [11]. |

| Substrate Inhibition | Low / Baseline | Strong | Reduced to near Wild-Type | Synergistic effect between mutations in different tunnels [11]. |

| Ki (Inhibition Constant) | Not specified in extracts | Low | Higher than L177W | A higher Ki indicates weaker inhibition [11]. |

| Key Finding | Conventional kinetics | Substrate binds EP complex, blocks product exit | Opened auxiliary tunnel relieves blockage | Engineering access tunnels is a valid strategy to control substrate inhibition [11]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Transient-State Kinetic Analysis to Identify Product Release Blockage

Objective: To distinguish substrate inhibition caused by binding to the enzyme-product complex from classical mechanisms by analyzing the complete reaction pathway.

Methodology:

- Rapid-Kinetics Setup: Use a stopped-flow or quenched-flow instrument to initiate the reaction and measure product formation on a millisecond timescale.

- Pre-Steady State Burst Phase: Under conditions where enzyme concentration ([E]) is significant relative to substrate ([S]), look for a rapid "burst" of product formation equal to the concentration of active enzyme sites. This burst represents the first turnover.

- Steady-State Phase: The linear phase after the burst represents the steady-state turnover, which is limited by the rate-limiting step (often product release).

- Varying Substrate Concentration: Repeat the experiment across a wide range of substrate concentrations, including inhibitory levels.

- Data Analysis: If the burst amplitude remains constant but the steady-state rate decreases at high [S], it indicates that the chemical step is unaffected, but a post-chemical step (like product release) is being inhibited [11].

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations to Visualize Tunnel Blockage

Objective: To computationally model and visualize the molecular interactions where a substrate molecule obstructs the product exit pathway.

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain the crystal structure of the enzyme (e.g., PDB ID 1MJ5 for wild-type LinB).

- Use simulation software (e.g., HTMD). Protonate the structure at the desired pH (e.g., 7.5) using a tool like H++.

- Manually place the substrate (e.g., DBE) near the tunnel entrance and the product (e.g., bromide ion) in the active site.

- Solvate the system in a water box (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 0.1 M) [11].

- Equilibration:

- Perform a multi-step equilibration: first with constraints on protein heavy atoms, then without constraints, each for ~2.5 ns in an NPT ensemble at 300 K [11].

- Production and Adaptive Sampling:

- Run production simulations using adaptive sampling epochs (e.g., 10 x 50 ns). Use a metric like the distance between key atoms in the substrate, product, and tunnel residues to guide sampling [11].

- Markov State Model (MSM) Construction:

- Build an MSM from the simulation data to identify metastable states and their transition probabilities. This reveals the most probable pathways for ligand entry and exit and can identify states where the substrate and product are simultaneously trapped [11].

- Analysis:

- Analyze the MSM states to identify conformations where the substrate is positioned in the tunnel, physically blocking the product's egress path.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Haloalkane Dehalogenase (LinB) Variants | Model enzyme system for studying access tunnel function and substrate inhibition. Includes wild-type and mutants like L177W and I211L [11] [18]. |

| 1,2-Dibromoethane (DBE) | Prototypical substrate used in kinetic assays and MD simulations with LinB dehalogenase [11]. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Instrument essential for performing transient-state kinetic analysis to measure rapid, pre-steady-state reaction phases [11]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., HTMD) | Computational platform used for running MD simulations, system equilibration, and adaptive sampling to study molecular-level events [11]. |

| Markov State Model (MSM) Algorithms | Analytical tools built from MD simulation data to identify and quantify the probabilities of different enzyme-ligand states and transitions [11]. |

| Spin Columns (for DNA/RNA clean-up) | Used to remove contaminants like salts or solvents from DNA samples prior to enzymatic reactions (e.g., restriction digests) to prevent inhibition [19]. |

| dam⁻/dcm⁻ E. coli Strains | Used for propagating plasmid DNA to avoid Dam/Dcm methylation, which can block cleavage by methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Addressing Substrate Inhibition

Problem: Enzyme reaction rate decreases at high substrate concentrations, leading to non-classical kinetic profiles.

Background: Substrate inhibition occurs when excess substrate molecules bind to non-catalytic sites or form unproductive complexes with the enzyme, reducing catalytic efficiency [5]. This is common in allosteric enzymes and multimeric complexes.

Troubleshooting Steps:

Confirm the Phenomenon

- Symptom: A hyperbolic or bell-shaped curve when plotting reaction velocity (V) against substrate concentration [S], rather than the standard saturation curve [5].

- Action: Perform assays with a wide range of substrate concentrations, ensuring you include high [S] values (e.g., 5-10x Km).

Verify Initial Velocity Conditions

- Symptom: Non-linear progress curves even at low substrate concentrations.

- Action: Ensure measurements are taken in the initial linear phase where less than 10% of the substrate has been converted to product. Reduce enzyme concentration if necessary to extend linearity [20].

Apply the Correct Model

- Symptom: The standard Michaelis-Menten model provides a poor fit for the data.

- Action: Fit data using the modified Michaelis-Menten equation for substrate inhibition [5]:

V = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S] + ([S]^2 / Ki)) - Here,

Kiis the substrate inhibition constant. A lower Ki indicates stronger inhibition.

Optimize Reaction Conditions

- Factor: Substrate Concentration.

- Solution: Identify the optimal [S] that maximizes velocity and avoid inhibitory concentrations in your assay design [5].

- Factor: Enzyme Concentration.

- Solution: At low enzyme concentrations, saturation and inhibition can occur more readily; adjust accordingly [5].

- Factor: pH and Temperature.

- Solution: These can alter enzyme conformation and substrate affinity; re-evaluate kinetics after any change in conditions [5].

- Factor: Substrate Concentration.

Preventive Measures: Always perform a comprehensive substrate saturation experiment during assay development to identify potential inhibitory ranges. Use this data to select a non-inhibitory, optimal substrate concentration for subsequent inhibitor studies.

Guide 2: Accurate Determination of Inhibition Constants (Ki)

Problem: Inconsistent or inaccurate estimation of Ki (inhibition constant) for competitive inhibitors.

Background: Ki is the dissociation constant for the enzyme-inhibitor complex. A lower Ki indicates a tighter binding inhibitor. For competitive inhibitors, Ki is the concentration that doubles the apparent Km [21] [8].

Troubleshooting Steps:

Use Substrate Concentrations at or Below Km

- Problem: Using [S] >> Km makes the assay insensitive to detecting competitive inhibitors.

- Solution: Set up inhibitor assays with substrate concentrations around or below the established Km value. This makes the velocity sensitive to changes in substrate binding and allows for better identification of competitive inhibitors [20].

Employ a Single, High Inhibitor Concentration (50-BOA Method)

- Problem: Traditional methods require multiple inhibitor and substrate concentrations, which can be resource-intensive and introduce bias [8].

- Solution: For precise Ki estimation, recent studies show that using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) can be sufficient. This IC50-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) incorporates the relationship between IC50 and Ki into the fitting process, reducing experiments by over 75% while maintaining accuracy [8].

Ensure Precise IC50 Determination

- Problem: An inaccurate IC50 value will lead to incorrect experimental design for Ki estimation.

- Action: Prior to Ki studies, accurately determine IC50 by measuring enzyme activity over a wide range of inhibitor concentrations with a single substrate concentration (typically at Km) [8].

Validate with Positive Controls

- Problem: Unaccounted for factors like low active enzyme fraction lead to erroneous Ki values.

- Solution: Use a known, well-characterized inhibitor for your enzyme as a positive control to validate the experimental setup and analysis model [22].

Preventive Measures: Before large-scale screening, thoroughly validate the inhibition assay using a control inhibitor to confirm that the estimated Ki matches literature values.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the reaction velocity not linear over time, and how does this impact parameter estimation?

- Non-linear progress curves often indicate that initial velocity conditions are not met. This can be due to substrate depletion (>10% converted), product inhibition, enzyme instability, or reverse reaction becoming significant [20]. Measuring kinetics under these non-linear conditions invalidates the steady-state assumption, leading to inaccurate estimates of Vmax, Km, and Ki. To fix this, reduce the enzyme concentration, shorten the reaction time, or increase the substrate concentration to ensure less than 10% conversion during the measurement period [20].

FAQ 2: What does a high Km value imply for my enzyme, and how should I choose substrate concentration for inhibitor assays?

- A high Km indicates low affinity between the enzyme and substrate, meaning a higher substrate concentration is needed to achieve half-maximal velocity (Vmax/2) [23]. When designing inhibitor assays, using a substrate concentration around or below the Km value is crucial for identifying competitive inhibitors, as it makes the reaction velocity sensitive to competition at the active site [20].

FAQ 3: How can I distinguish between different types of enzyme inhibition by analyzing Vmax and Km?

- The effect on Vmax and Km reveals the inhibition mechanism [23].

- Competitive Inhibition: Apparent Km increases; Vmax remains unchanged.

- Non-competitive Inhibition: Vmax decreases; Km remains unchanged.

- Uncompetitive Inhibition: Both Vmax and Km decrease. These patterns are most clearly identified using a Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/V vs. 1/[S]) [24].

FAQ 4: What is IC50, and how is it related to the inhibition constant Ki?

- IC50 (Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration) is the concentration of an inhibitor that reduces enzyme activity by 50% under a specific set of assay conditions [21]. Its relationship to Ki depends on the inhibition mechanism and substrate concentration. For a competitive inhibitor, the IC50 value is directly influenced by the substrate concentration and the enzyme's Km. Therefore, Ki is a more fundamental constant as it describes the inherent affinity of the inhibitor for the enzyme, independent of assay conditions [8].

FAQ 5: Our lab is new to enzyme kinetics. What is a robust experimental workflow to estimate Vmax and Km?

- A reliable workflow for determining Vmax and Km involves several key steps [24] [20]:

- Establish Initial Velocity Conditions: Conduct a time-course experiment with multiple enzyme concentrations to find the range where product formation is linear over time.

- Vary Substrate Concentration: Measure initial velocity at 8 or more substrate concentrations, ideally spanning from 0.2 to 5.0 times the expected Km.

- Plot and Analyze: Plot velocity versus [S] to generate a saturation (Michaelis-Menten) curve. Vmax is the maximum plateau value, and Km is the [S] at Vmax/2.

- Linearize Data (Optional): For more accurate estimation, use a Lineweaver-Burk plot (1/V vs. 1/[S]). Vmax is derived from the y-intercept (1/Vmax), and Km from the x-intercept (-1/Km) [24].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Experimentally Determined IC50 Values for Tyrosinase Inhibitors

Data obtained using an amperometric biosensor with catechol as substrate. A lower IC50 indicates a more potent inhibitor [21].

| Inhibitor Compound | IC50 (μM) | Relative Potency |

|---|---|---|

| Kojic Acid | 30 | Highest |

| Benzoic Acid | 119 | Moderate |

| Sodium Azide | 1480 | Lowest |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics Studies

Key materials and their functions based on cited experimental protocols [21] [24] [20].

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Tyrosinase Enzyme | Model enzyme for studying phenol oxidation and inhibition [21]. |

| Invertase Enzyme | Model enzyme for teaching hydrolysis kinetics; easily sourced [24]. |

| Catechol | Substrate for tyrosinase in biosensor-based inhibition studies [21]. |

| Sucrose | Natural substrate for the invertase enzyme [24]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Used as a stabilizing agent in enzyme immobilization protocols [21]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent for immobilizing enzymes on solid supports [21]. |

| Phosphate Buffer | Maintains optimal and stable pH for enzymatic reactions [21] [20]. |

| Glucometer & Strips | Detection system for measuring glucose product in invertase assays [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Vmax and Km via Michaelis-Menten and Lineweaver-Burk Analysis

Application: Fundamental characterization of enzyme kinetics. Based on: Educational activity for undergraduate students using the invertase enzyme [24].

Procedure:

- Prepare Invertase Enzyme Solution: Suspend 0.25 g of dry yeast in 250 mL of warm distilled water (30°C). Stir periodically for 20 minutes, then store at 30°C [24].

- Prepare Substrate Dilutions: Serially dilute a 0.4 M sucrose stock solution to create at least six different concentrations (e.g., from 0.2 M to 0.00625 M) [24].

- Initiate Reactions: Add 1 mL of enzyme solution to 1 mL of each substrate dilution at timed intervals. Incubate all tubes at 30°C [24].

- Measure Product Formation: After 20 minutes, use a glucometer to measure the glucose concentration produced in each reaction tube [24].

- Calculate and Plot:

- Calculate the initial velocity (V0) for each sucrose concentration as μmol glucose produced per minute per mL.

- Michaelis-Menten Plot: Plot V0 vs. [Sucrose]. Vmax is the maximum plateau, and Km is [S] at Vmax/2.

- Lineweaver-Burk Plot: Plot 1/V0 vs. 1/[Sucrose]. The y-intercept is 1/Vmax, the x-intercept is -1/Km, and the slope is Km/Vmax [24].

Protocol 2: Assessing Inhibitor Potency (IC50) Using a Tyrosinase Biosensor

Application: Quantitative determination of inhibitor strength. Based on: Kinetic and analytical study of competitive tyrosinase inhibitors [21].

Procedure:

- Biosensor Preparation:

- Prepare a carbon black paste electrode (CBPE).

- Immobilize tyrosinase by cross-linking: Mix 15 µL tyrosinase (35 U/mL), 7.5 µL BSA (1% w/v), and 7.5 µL glutaraldehyde (0.25% w/v). Spread 7.5 µL of this mixture on the CBPE surface and dry for 1 hour at room temperature [21].

- Amperometric Measurement:

- Use the tyrosinase biosensor as the working electrode in a three-electrode system, polarized at -0.15 V vs. Ag/AgCl in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) [21].

- Inhibitor Testing:

- With a fixed, non-saturating concentration of catechol substrate, measure the steady-state current.

- Add increasing concentrations of the inhibitor to the cell and record the subsequent decrease in current, which corresponds to a loss of enzyme activity.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of inhibition at each inhibitor concentration.

- Plot % inhibition vs. log[Inhibitor]. Fit the data with a sigmoidal curve and determine the IC50 value, which is the inhibitor concentration that gives 50% inhibition [21].

Experimental Workflow and Kinetic Relationship Visualization

Experimental Workflow for Kinetic Analysis

Interrelationship of Key Kinetic Parameters

Kinetic Analysis in Practice: From Graphical Methods to Modern Curve Fitting

Substrate inhibition is a common deviation from standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics in which the velocity of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction decreases at higher substrate concentrations rather than reaching a stable plateau [1] [5]. This phenomenon occurs when a substrate molecule binds to both the catalytic site and a separate inhibitory site on the enzyme, forming a less productive or inactive enzyme-substrate-inhibitor (ESI) complex [1] [5]. Understanding and characterizing substrate inhibition is critical across biochemistry, pharmacology, and industrial biotechnology, as it plays important regulatory roles in metabolic pathways and can significantly impact drug metabolism and industrial enzyme processes [1] [5].

The Quotient Velocity Plot method provides researchers with a straightforward graphical approach for determining key kinetic parameters of substrate inhibition, distinguishing between complete inhibition (where the velocity eventually drops to zero) and partial inhibition (where the velocity approaches a non-zero asymptote) [1]. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for implementing this method effectively in your research.

Understanding Substrate Inhibition

Basic Concepts and Mechanisms

In standard Michaelis-Menten kinetics, reaction velocity increases with substrate concentration until reaching a maximum velocity (Vmax) as enzymes become saturated [25] [5]. However, in substrate inhibition, velocity declines after reaching an optimum due to one of these primary mechanisms:

- Two-site binding: The substrate binds to both the catalytic site and a separate inhibitory site, causing conformational changes that reduce catalytic efficiency [1] [5].

- Formation of inactive complexes: Excess substrate leads to the formation of ESI complexes (enzyme-substrate-inhibitor) that break down at a reduced velocity or not at all [1].

Mathematical Models

The classic Michaelis-Menten equation is modified to account for substrate inhibition. The most common model incorporates an additional term in the denominator to reflect the inhibitory effect at high substrate concentrations [5]:

Modified Michaelis-Menten Equation for Substrate Inhibition: [ V = \frac{V{\max} \cdot [S]}{Km + [S] + \frac{[S]^2}{K_i}} ] Where:

- (V) = reaction velocity

- (V_{\max}) = maximum velocity

- ([S]) = substrate concentration

- (K_m) = Michaelis constant

- (K_i) = inhibition constant

Table 1: Key Parameters in Substrate Inhibition Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Velocity | (V_{\max}) | Theoretical maximum reaction rate | Catalytic efficiency at saturation |

| Michaelis Constant | (K_m) | Substrate concentration at half (V_{\max}) | Apparent affinity for catalytic site |

| Inhibition Constant | (K_i) | Dissociation constant for inhibitory site | Measure of inhibition strength |

| Rate Constant Ratio | (k'/k) | Ratio of breakdown rate constants | Distinguishes complete ((k'=0)) from partial ((k'<1)) inhibition |

The Quotient Velocity Plot Method

Theoretical Basis

The Quotient Velocity Plot method transforms the substrate inhibition equation into a linear form by plotting (v/(V_{\max} - v)) against the reciprocal of substrate concentration ((1/[S])) at higher, inhibitory substrate concentrations [1]. This approach allows direct determination of kinetic parameters from the slope and intercept of the resulting straight line.

For complete substrate inhibition ((k' = 0)), the relationship becomes: [ \frac{v}{V{\max} - v} \approx \frac{Ki'}{[S]} ] This yields a straight line through the origin with slope (K_i') [1].

For partial substrate inhibition ((k'/k < 1)), the relationship is: [ \frac{v}{V{\max} - v} \approx \frac{Ki'}{1 - k'/k} \cdot \frac{1}{[S]} + \frac{k'/k}{1 - k'/k} ] This gives a straight line with a y-intercept of ((k'/k)/(1 - k'/k)) and slope of (K_i'/(1 - k'/k)) [1].

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for implementing the Quotient Velocity Plot method:

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Experimental Issues

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor linearity in quotient plot | Incorrect Vmax value; Substrate inhibition not the dominant mechanism; Measurement errors at high [S] | Re-determine Vmax accurately at low [S]; Verify substrate inhibition mechanism; Repeat measurements in critical concentration range | Use multiple methods to confirm Vmax; Include sufficient data points near optimal [S] |

| Unrealistic parameter values (e.g., negative constants) | Experimental errors; Incorrect assumption of mechanism; Poor data quality at extreme concentrations | Verify data quality and experimental conditions; Test alternative mechanisms; Extend substrate concentration range systematically | Include controls; Validate assay conditions with standard substrates |

| High variability in plotted data | Pipetting errors at viscous high [S]; Enzyme instability during prolonged assays; Inadequate replication | Use positive displacement pipettes for viscous solutions; Check enzyme stability under assay conditions; Increase replicates for key concentrations | Prepare fresh substrate solutions; Standardize assay timing |

| Unable to distinguish complete vs partial inhibition | Insufficient data at high inhibition levels; Too narrow substrate concentration range | Extend substrate concentration further into inhibitory range; Increase data density in transition region | Perform preliminary range-finding experiments |

Data Quality and Validation

Verification of Vmax: Since the Quotient Velocity Plot method depends on an accurate Vmax value, determine this parameter from measurements at low substrate concentrations where inhibition is negligible. Use both direct linear plots and nonlinear regression of the Michaelis-Menten equation to confirm consistency [26].

Mechanism Validation: The Quotient Velocity Plot method assumes a rapid equilibrium system where Km approximates the dissociation constant of the ES complex. Verify this assumption by examining the dependence of Km on modifier concentration - any non-monotonous dependence (showing a maximum or minimum) indicates deviations from the underlying assumptions [26].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can the Quotient Velocity Plot method be used for statistical analysis and parameter error estimation? No, the Quotient Velocity Plot is primarily a graphical diagnostic method. Because both variables (v/(Vmax-v) and 1/[S]) contain experimental error in v, the assumptions of standard linear regression are violated. Use this method for initial parameter estimation and mechanism diagnosis, then apply nonlinear regression to the original velocity data for precise parameter estimation with error analysis [26].

Q2: How can I distinguish substrate inhibition from other types of inhibition like non-competitive or uncompetitive inhibition? Substrate inhibition specifically shows a characteristic decline in velocity at high substrate concentrations, whereas other inhibition types typically show reduced velocity across all substrate concentrations when inhibitors are present. The Quotient Velocity Plot specifically diagnoses substrate inhibition by the linear relationship between v/(Vmax-v) and 1/[S] at inhibitory concentrations [1] [5].

Q3: What substrate concentration range should I use for the Quotient Velocity Plot? Focus on the inhibitory concentration range where velocity clearly decreases with increasing substrate. This typically requires substrate concentrations 5-20 times Km, but the exact range is enzyme-specific. Include at least 5-6 data points in the inhibitory region for reliable linear fitting [1].

Q4: The method doesn't seem to work for my enzyme system. What could be wrong? Potential issues include: (1) The inhibition may not follow the two-site binding mechanism assumed by the method; (2) The substrate may be acting as both substrate and modifier simultaneously; (3) There may be significant experimental error in determining Vmax; (4) The system may not adhere to rapid equilibrium conditions. Consider alternative mechanisms and validation experiments [26].

Q5: Can this method be applied to systems with multiple inhibitors or allosteric effectors? The basic Quotient Velocity Plot method described here is designed for simple substrate inhibition without additional effectors. For complex systems with multiple modifiers, consider the related Specific Velocity Plot method, which can handle a wider range of modifier mechanisms [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Quality Specifications | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | Catalytic component of the system | High purity (>95%); Known concentration; Verified activity | Aliquot and store appropriately; Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles |

| Substrate | Reactant and potential inhibitor | High purity; Appropriate solubility in assay buffer | Prepare fresh solutions; Consider solubility limits at high concentrations |

| Assay Buffer | Maintains optimal pH and ionic conditions | Appropriate buffering capacity; Compatible cofactors | Include necessary cofactors; Check for chemical compatibility |

| Detection Reagents | Measure reaction progress (e.g., NADH, chromogens) | Suitable sensitivity and dynamic range | Verify linear response range; Protect from light if sensitive |

| Positive Control | Validates assay performance | Enzyme with known substrate inhibition parameters | Include in every experiment to monitor assay performance |

Application Example: Phosphofructokinase Analysis

The Quotient Velocity Plot method was successfully applied to analyze substrate inhibition of Escherichia coli phosphofructokinase II (encoded by pfkB) by ATP [1]. The analysis revealed that ATP inhibition follows a complete inhibition pattern ((k' = 0)), with straight lines converging on the origin in the quotient plot [1]. The apparent (K_i') values were determined to be 0.65 mM, 2.8 mM, and 7 mM in the presence of 0.1 mM, 0.5 mM, and 5 mM fructose 6-phosphate, respectively, demonstrating the utility of this method for quantifying inhibition constants under different conditions [1].

Implementing the Haldane Model for Non-Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Haldane Model Implementation Issues

Problem 1: Poor Curve Fit with Experimental Data

- Potential Cause: The classical Haldane equation may be too simplistic for your enzyme system, which might exhibit more complex inhibition mechanics.

- Solution: Consider the generalized Haldane-Radić equation (shown below) that includes a catalytic parameter

bto account for whether the ternary SES complex has any catalytic activity. Fit your data to this more flexible model [15].v = (Vₘ[S]) / (Kₘ + [S] + ([S]²/Kᵢ))... (Classic Haldane)v = (Vₘ[S] (1 + b[S]/Kᵢ)) / (Kₘ + [S] + ([S]²/Kᵢ))... (Haldane-Radić)

Problem 2: No Closed-Form Solution for Substrate Progress Curve

- Potential Cause: The differential form of the Haldane equation is transcendental and lacks an explicit analytical solution for substrate concentration over time, making direct integration difficult [27] [15].

- Solution:

- Decomposition Method: Use a recursive series solution. Divide the total reaction time into small subintervals (e.g., 1% of total time) and use the first few terms of the decomposition series for accurate approximation [27].

- Logistic Approximation: For a simplified approach, you can adapt the logistic progress curve solution derived for Michaelis-Menten kinetics, though its applicability for strong inhibition should be validated [15].

Problem 3: Substrate Inhibition Disrupts Bioreactor Performance

- Potential Cause: High substrate concentration in the medium leads to osmotic stress, increased viscosity, and reduced oxygen transfer, inhibiting cell growth [3].

- Solution:

- Switch from a batch to a fed-batch process. This allows for controlled addition of substrate, maintaining its concentration below the inhibitory threshold [3].

- Consider advanced bioreactor designs like Two-Phase Partitioning Bioreactors (TPPBs) or cell immobilization techniques to protect cells from high local substrate concentrations [3].

Problem 4: Inaccurate Estimation of Inhibition Constant (Kᵢ)

- Potential Cause: Traditional methods requiring multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations can be inefficient and sometimes introduce bias [8].

- Solution: Implement the IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA). This modern method uses a single inhibitor concentration greater than the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) for precise and accurate estimation of Kᵢ, significantly reducing experimental workload [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use the Haldane model instead of the standard Michaelis-Menten model? Use the Haldane model when you observe a clear peak in your reaction rate (v) versus substrate concentration ([S]) plot, followed by a decrease at higher [S]. This "hump-shaped" curve is the definitive signature of substrate inhibition [2] [3]. The Michaelis-Menten model only produces a hyperbolic curve that reaches a plateau.

Q2: What are the physiological implications of substrate inhibition? Substrate inhibition is not just an in vitro artifact; it is a critical regulatory mechanism in living systems. For example, it helps maintain stable ATP levels by inhibiting phosphofructokinase in glycolysis when energy is abundant. It also rapidly terminates neural signals by controlling neurotransmitter levels [11].

Q3: My enzyme shows substrate inhibition. Is the Haldane mechanism the only explanation? No. While the Haldane mechanism (binding of a second substrate molecule to an allosteric site, forming an unproductive SES complex) is the most common model, recent studies have revealed alternative mechanisms. A significant one is substrate binding to the enzyme-product (EP) complex, blocking product release and halting the catalytic cycle [11].

Q4: Are there mathematical solutions for modeling the progress curve with the Haldane equation? The integrated form of the Haldane equation does not have a simple closed-form solution [27] [15]. However, accurate numerical and approximate series solutions exist. The decomposition method [27] and transformations involving the Lambert W function [15] are two advanced approaches that can be implemented computationally to model the substrate depletion curve over time effectively.

Essential Experimental Parameters & Data

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters in the Haldane Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Velocity | Vₘ | concentration/time | The theoretical maximum reaction rate, approached at optimal [S] before inhibition. |

| Michaelis Constant | Kₘ | concentration | The substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vₘ in the absence of inhibition. |

| Inhibition Constant | Kᵢ | concentration | Reflects the dissociation constant for the inhibitory enzyme-substrate complex (ES₂). A lower Kᵢ indicates stronger inhibition [2]. |

| Substrate Concentration at Max Rate | [S]ₘ | concentration | The substrate concentration that yields the highest observable reaction rate. Calculated as [S]ₘ = √(Kₘ × Kᵢ) [2]. |

Table 2: Recommended Experimental Design for Parameter Fitting

| Factor | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Range | Should extensively bracket the estimated [S]ₘ. Use concentrations from well below to well above [S]ₘ. | Essential for capturing both the ascending and descending limbs of the rate curve. |

| Data Points | Use a higher density of points around the suspected [S]ₘ. | Ensures accurate characterization of the critical peak region. |

| Replicates | Minimum of 3 replicates per [S]. | Accounts for experimental variability and improves parameter estimation reliability. |

| Inhibitor Screening | For a new inhibitor, use the 50-BOA method: a single [I] > IC₅₀ [8]. | Drastically reduces experimental load while maintaining precision. |

Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

Haldane Inhibition Mechanism

Diagram Title: Classical Haldane Substrate Inhibition Mechanism

This diagram illustrates the core principle of the Haldane model. The enzyme (E) first binds one substrate molecule (S) to form the productive ES complex, which can proceed to form product (P). However, at high substrate concentrations, a second molecule of S can bind to the ES complex, forming a non-productive or less productive ternary complex (SES), which inhibits the reaction [2] [11].

Haldane Model Implementation Workflow

Diagram Title: Kinetic Analysis Workflow for Substrate Inhibition

This workflow provides a logical sequence for identifying and characterizing substrate inhibition. The key diagnostic step is visually confirming a "hump-shaped" curve in the kinetic plot, which triggers the application of the Haldane model for parameter estimation [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Haldane Kinetics Studies

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fed-Batch Bioreactor | Allows controlled substrate feeding to maintain [S] below inhibitory levels, overcoming a major limitation in production processes [3]. | Critical for scaling up processes with substrate-inhibited enzymes or microbial cultures. |

| Enzyme Variants (Mutants) | Used to probe inhibition mechanisms. Specific point mutations can abolish or enhance substrate inhibition, providing insights into the binding sites involved [15] [11]. | e.g., L177W mutation in LinB dehalogenase introduced strong substrate inhibition [11]. |

| IC₅₀-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) | A computational/experimental method that drastically reduces the number of experiments needed to precisely estimate inhibition constants (Kᵢ) [8]. | Requires user-friendly MATLAB or R packages provided by the method's developers [8]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Used to visualize and understand the atomic-level details of inhibition, such as substrate molecules blocking product exit tunnels [11]. | e.g., HTMD software; used to model how substrate binding to the enzyme-product complex causes inhibition [11]. |

Practical Guide to Nonlinear Regression with Tools like GraphPad Prism

Substrate Inhibition Kinetics FAQ

Q1: What is substrate inhibition and why is it important in enzyme kinetics?

Substrate inhibition is a phenomenon observed in approximately 20% of all known enzymes, where the enzyme activity decreases at high substrate concentrations rather than reaching a stable plateau [28]. This occurs when two substrate molecules bind to the enzyme, potentially blocking its activity or forming a less effective enzyme-substrate complex [28] [5]. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for accurate enzymatic modeling in biochemistry, pharmacology, and industrial biotechnology, as it represents an important regulatory mechanism in biological systems [5] [16].

Q2: What is the mathematical model for substrate inhibition in GraphPad Prism?

GraphPad Prism uses the following model for substrate inhibition kinetics [28]:

Y = Vmax × X / (Km + X × (1 + X/Ki))

Where:

- Y is the enzyme velocity (response variable)

- X is the substrate concentration

- Vmax is the maximum enzyme velocity

- Km is the Michaelis-Menten constant

- Ki is the inhibition constant for substrate binding

This model can be rearranged to: Y = Vmax / (Km/X + 1 + X/Ki) to better understand how different parameters dominate various regions of the curve [28].

Q3: Why might my substrate inhibition model fail to converge in Prism?

Two common reasons cause convergence problems [28]:

- Insufficient data range: You need X values both less than Km and greater than Ki to provide enough information for the algorithm to separately determine both parameters.

- Model-data mismatch: The shape of your experimental data may not truly comply with the substrate inhibition model, even if it visually appears similar.

Q4: How do I set up my data in Prism for substrate inhibition analysis?

Create an XY data table with [28]:

- X column: Substrate concentration

- Y columns: Enzyme activity measurements For multiple experimental conditions, place each dataset in separate columns (A, B, C, etc.).

Substrate Inhibition Parameters Table

| Parameter | Description | Units | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax | Maximum enzyme velocity without inhibition | Same as Y axis | Theoretical maximum rate if substrate didn't inhibit |

| Km | Michaelis-Menten constant | Same as X axis | Describes substrate-enzyme interaction affinity |

| Ki | Inhibition constant | Same as X axis | Dissociation constant for inhibitory substrate binding; lower value = stronger inhibition |

Troubleshooting Common Prism Issues

Q1: What should I do if GraphPad Prism won't start? (Windows)

If Prism fails to launch completely, try these solutions in order [29]:

- Delete preferences files: Corrupted preference files (PrismX.cfg, where X is the version number) can prevent startup. Navigate to

Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\GraphPad Software\Prism\and delete files for all Prism versions [29]. - Reboot your computer: Simple but effective for resolving many temporary system issues [29].

- Prevent checking for updates: In rare cases, Prism can hang during update checks. Disconnect from the internet before starting Prism, then in Edit → Preferences → Internet, disable automatic update checking [29].

- Check for multiple instances: Use Task Manager (Ctrl+Alt+Del) to ensure Prism isn't already running in the background [29].

- Delete auto backup files: Remove temporary files from

C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Local\Temp\[29].

Q2: How do I resolve error messages related to Prism Cloud login?

Prism Cloud requires an eligible subscription and may show these specific errors [30]:

- "No workspace associated with the Activation Code": Your subscription lacks an associated Prism Cloud Workspace needed for publishing (though you can still login and collaborate on others' work).

- "No seats left in the associated Prism Cloud Workspace": The workspace has reached its user limit; the workspace administrator needs to free up seats or purchase additional ones [30].

Q3: Why does my nonlinear regression fail or produce ambiguous results?

For substrate inhibition specifically, ensure [28]:

- Adequate data points: Collect data across a wide substrate concentration range, ideally with values both below Km and above Ki.

- Proper initial values: Prism 7+ uses improved algorithms for initial parameter estimates.

- Model validation: Verify that your data truly follows the substrate inhibition pattern.

Prism Startup Troubleshooting Table

| Problem | Symptoms | Solution | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrupted Preferences | Prism won't launch, no error message | Delete PrismX.cfg files | Affects versions 4+; location varies by Windows version |

| Update Check Hang | Stalls during startup, no Welcome dialog | Disconnect internet or add "/U" to command line | Use Target: "C:\Program Files\GraphPad\PrismX\prism.exe" /U |

| VPN Conflict | Crashes during startup (Prism 6.00-6.01 only) | Update to Prism 6.02+ or disable VPN | Fixed in later versions |

| Path Length Issue | Won't launch from shortcut | Ensure total path < 260 characters | Avoid Unicode characters in path |

Experimental Protocols for Substrate Inhibition Studies

Protocol 1: Measuring Enzyme Kinetics with Substrate Inhibition

Materials Required:

- Purified enzyme preparation

- Substrate solutions across concentration range (from well below expected Km to above expected Ki)

- Buffer components appropriate for the enzyme

- Spectrophotometer or appropriate detection method

- GraphPad Prism software (version 8 or later recommended)

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Experimental Design:

- Prepare substrate concentrations spanning a minimum of 3 orders of magnitude.

- Include replicates for each concentration (minimum n=3).

- Plan for appropriate controls (no enzyme, no substrate).

Data Collection:

- Measure initial reaction rates at each substrate concentration.

- Ensure measurements fall within the linear range for product formation.

- Record time-course data to calculate initial velocities.

Data Entry in Prism:

- Create an XY table.

- Enter substrate concentrations in the X column.

- Enter corresponding enzyme velocities in Y columns.

- Label columns appropriately for record keeping.

Nonlinear Regression Analysis:

- Click Analyze → Nonlinear regression → Enzyme kinetics equations → Substrate inhibition.

- Review initial parameter estimates; adjust if necessary based on your data.

- Run the fitting algorithm and examine the residuals plot.

Model Validation:

- Check confidence intervals for all parameters.

- Verify that the curve appropriately fits data across all regions.

- Consider comparing with other models if fit is poor.

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting Poor Fits in Substrate Inhibition Models

When the substrate inhibition model doesn't converge or produces ambiguous results, follow this diagnostic workflow [28]:

Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics

Essential Materials for Substrate Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Preparation | Biological catalyst for reaction | Purity critical; avoid contaminating enzymes |

| Substrate Series | Reactant across concentration range | Must span from below Km to above Ki; solubility limits |

| Detection System | Measure reaction progress | Spectrophotometric, fluorometric, or radioisotopic methods |

| Buffer Components | Maintain optimal pH and ionic environment | Should not interfere with enzyme activity or detection |

| Positive Controls | Verify experimental system functionality | Known substrate/inhibitor combinations |

| GraphPad Prism | Data analysis and nonlinear regression | Version 8+ recommended for improved algorithms |

Advanced Concepts in Substrate Inhibition

Generalized Model for Enzymatic Substrate Inhibition

Beyond the standard model implemented in Prism, a more generalized framework exists where binding of the second substrate molecule doesn't necessarily result in complete loss of activity [16]. In this model:

- The enzyme can have variable activity in both single (ES) and double (ES2) substrate-bound states

- The optimum substrate concentration ([S]*) can be calculated using specialized equations

- The condition V1max > V2max must be met for an optimum substrate concentration to exist [16]

This generalized approach provides greater flexibility for modeling complex enzymatic behavior beyond classical complete inhibition scenarios.

Relationship Between Parameters and Curve Characteristics

Understanding how each parameter affects the substrate inhibition curve is essential for proper experimental design and interpretation [28]:

- Small X values (X < Km): Curve characteristics dominated by Km value

- Large X values (X > Ki): Curve characteristics dominated by Ki value

- Middle X values: Jointly determined by both Km and Ki

- Vmax: Controls the theoretical maximum height of the peak, though not the actual Y value at the peak

This understanding explains why data must be collected across a broad concentration range to reliably estimate all parameters in the substrate inhibition model.

Substrate inhibition is a common deviation from Michaelis-Menten kinetics where an enzyme is inhibited by its own substrate at high concentrations. This phenomenon is characterized by a reaction velocity that initially rises with increasing substrate concentration, reaches a maximum, and then declines. Approximately 25% of known enzymes exhibit substrate inhibition, which plays crucial regulatory roles in metabolic pathways by preventing wasteful overconsumption of substrates [31] [1].

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers studying substrate inhibition in phosphofructokinase (PFK) and haloalkane dehalogenase (HLD), two enzymes with significant implications in energy metabolism and bioremediation, respectively.

Phosphofructokinase (PFK) Substrate Inhibition

Troubleshooting Guide: PFK Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly low PFK activity at high ATP concentrations | ATP substrate inhibition | Reduce ATP concentration to optimal range (typically 0.3-2.5 mM); use kinetic modeling to separate substrate vs. inhibitory effects [31] |

| Inconsistent PFK activity measurements across pH conditions | pH-sensitive ATP binding to regulatory site | Maintain strict pH control using appropriate buffers: MES (pH 5.3), PIPES (pH 6.4-7), HEPES (pH 7.1-8), Tris-base (pH 9) [31] |

| Non-linear reaction progress curves | Depletion of substrate or accumulation of inhibitory products | Use initial velocity method (first 2+ data points) or implement full kinetic modeling of entire time course [31] |

| High variability in replicate measurements | Inconsistent homogenization of muscle tissue | Use liquid nitrogen pulverization with Polytron homogenizer at 1:20 (w/v) in ice-cold K₂HPO₄ buffer [31] |

Quantitative Analysis of PFK Substrate Inhibition

Table 1: PFK Activity as Affected by pH and ATP Concentration [31]

| ATP Concentration (mM) | Relative Activity at pH 6.5 | Relative Activity at pH 7.0 | Relative Activity at pH 7.5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | 45% | 58% | 52% |