The Invisible World of Industrial Biocatalysis

How Electron Microscopy Revolutionizes Green Chemistry

The Hidden World of Biocatalysis

In the fascinating realm where biology meets industry, scientists have harnessed the power of nature's most efficient catalysts—enzymes—to transform how we manufacture everything from life-saving medications to eco-friendly materials. These remarkable biological workhorses operate at unimaginably small scales, making them virtually invisible to the naked eye. Yet, understanding their precise organization within industrial carriers represents the key to unlocking their full potential.

Through the cutting-edge technology of field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), researchers can now peer into the hidden architecture of biocatalytic particles with unprecedented clarity, revealing a complex microscopic landscape that holds the secret to greener, more efficient chemical processes 1 4 .

This revolutionary imaging technology doesn't just provide pretty pictures—it offers crucial insights that are reshaping how we design biological catalysts for a more sustainable future. By revealing the intricate relationship between enzyme distribution and particle morphology, FESEM helps engineers create more efficient, stable, and cost-effective biocatalysts that are already transforming industries from pharmaceuticals to environmental technology 9 .

What Are Biocatalytic Particles?

The Science of Enzyme Immobilization

At their core, biocatalytic particles are sophisticated microscopic structures designed to harness the power of enzymes for industrial processes. These particles typically range from micrometers to millimeters in size and serve as stable supports for enzyme immobilization.

Free enzymes, while efficient, often suffer from limitations that make them impractical for industrial use: they can be structurally fragile, difficult to recover after use, and unstable under the harsh conditions of industrial processes.

Design and Composition

Industrial biocatalytic particles are typically composed of two key elements:

- A support matrix (often made from polymers, silica, or other materials)

- The immobilized enzymes anchored to this matrix

These particles can be crafted from various materials, including chitosan, gelatin, silica nanoparticles, or synthetic polymers, each offering different advantages for specific applications 3 .

By attaching biological catalysts to solid supports or trapping them within porous materials, scientists create robust, reusable, and stable biocatalytic systems that maintain the exquisite specificity and efficiency of natural enzymes while overcoming their practical limitations 3 .

FESEM: A Window into the Nanoworld

Seeing the Unseeable

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) represents a monumental leap in our ability to visualize the microscopic world. Unlike conventional optical microscopes limited by the wavelength of visible light, FESEM uses a focused beam of electrons to achieve resolutions down to 0.5 nanometers—allowing us to distinguish features nearly a million times smaller than a grain of sand 7 .

The secret to FESEM's exceptional resolution lies in its unique electron source. Where conventional scanning electron microscopes use thermionic emission (heating a filament to produce electrons), FESEM employs a field emission gun that generates electrons by applying a strong electric field to a sharp tungsten tip.

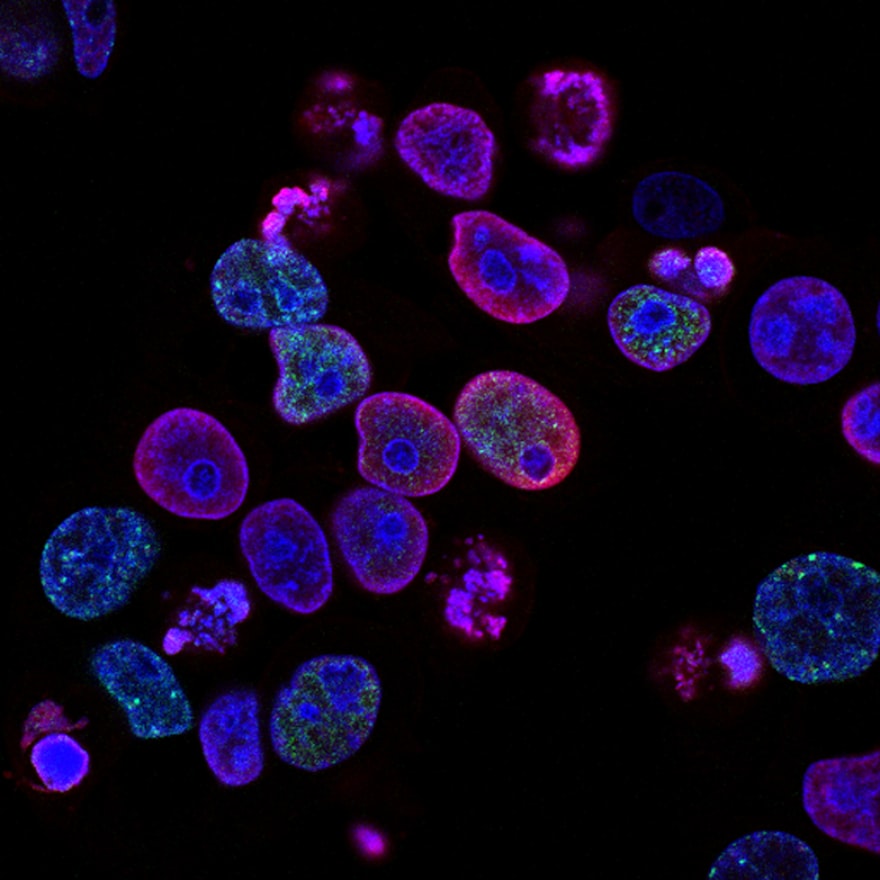

FESEM instrumentation allows for nanoscale imaging of biological materials.

Why FESEM Triumphs for Biocatalyst Analysis

For studying biocatalytic particles, FESEM offers several distinct advantages over other microscopic methods:

Reduced interpretation discrepancies

The single preparation method and detection system avoids inconsistencies that arise when using different techniques on different samples 1 .

Surface topography visualization

FESEM excels at revealing surface features and three-dimensional morphology that would be difficult to discern with other techniques 7 .

A Case Study: Unveiling the Secrets of an Industrial Biocatalyst

The Assemblase Particle

One of the most illuminating applications of FESEM in industrial biocatalysis comes from the analysis of Assemblase, an industrially important biocatalytic particle containing immobilized penicillin-G acylase—an enzyme crucial for producing semi-synthetic antibiotics 1 . Understanding the internal architecture of these particles is essential for optimizing their performance in manufacturing medications.

Step-by-Step: How Scientists Visualize Enzyme Distribution

Sample Preparation

Particles are carefully fixed and prepared to maintain their native structure under the vacuum conditions required for electron microscopy.

Sectioning

Unlike traditional TEM preparations that require ultra-thin sections, FESEM allows researchers to work with thick sections (several micrometers) that preserve more of the particle's three-dimensional structure.

Labeling

Enzymes are tagged with specific markers (usually gold-labeled antibodies) that allow their precise localization within the particle.

Imaging

The prepared samples are scanned with the focused electron beam, detecting secondary electrons emitted from the sample surface to create detailed topographic images.

Analysis

Sophisticated software helps quantify enzyme distribution patterns throughout the particle structure.

Revelations from the Nanoscale: Key Findings

The FESEM analysis of Assemblase particles yielded several fascinating discoveries that transformed our understanding of these industrial biocatalysts:

| Location in Particle | Enzyme Concentration Relative to Core | Probable Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Surface | 1.4 times higher | Dense polymer top layer |

| Areas around internal macro-voids (halos) | 7.7 times higher | Local polymer demixing |

| Core Region | Standard concentration | Homogeneous polymer mix |

Table 1: Enzyme Distribution Patterns in Assemblase Biocatalytic Particles

Perhaps most remarkably, FESEM revealed that enzyme distribution wasn't random but followed very specific patterns dictated by the underlying morphological heterogeneity of the support material. The research team discovered strikingly dense top layers surrounding both the exterior of the particles and internal macro-voids, creating distinct microenvironments that influenced where enzymes accumulated .

Comparative Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Light Microscopy | ~200 nm | Limited resolution |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | ~0.1 nm | Ultra-thin sections required |

| Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) | 0.5 nm | None of the above limitations |

Table 2: Advantages of FESEM Over Other Microscopic Techniques for Biocatalyst Analysis

Particle Size Impact

| Particle Size (μm) | Relative Efficiency | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| 50-100 | 100% | Balanced ratio |

| 100-200 | 87% | Diffusion limitations |

| 200-500 | 72% | Significant heterogeneity |

Table 3: Impact of Particle Size on Catalytic Efficiency

Further analysis suggested that these heterogeneities resulted from polymer demixing during particle production—a process where the two primary polymers used (chitosan and gelatin) separated due to their different hydrophilicities. This demixing created regions with distinct chemical properties that preferentially attracted enzymes, forming the heterogeneous distribution patterns observed .

Quantitative Insights: Relating Structure to Function

Beyond the striking images, FESEM provided crucial quantitative data that linked particle structure to function. These findings demonstrated that larger particles developed more pronounced heterogeneities in enzyme distribution, which directly impacted their catalytic efficiency due to substrate diffusion limitations. This critical insight helps engineers optimize particle size for specific industrial applications .

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Application in FESEM Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope | High-resolution imaging | Visualizing surface topography and enzyme distribution at nanoscale |

| Gold-Labeled Antibodies | Specific enzyme tagging | Localizing enzymes within the biocatalytic particle |

| Modified Silica Nanoparticles | Enzyme support material | Creating stable platforms for enzyme immobilization |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [BMIM]Cl) | Enzyme stabilization | Enhancing enzyme stability and activity in non-aqueous media |

| Polymer Components (Chitosan, Gelatin) | Matrix formation | Creating the structural framework of biocatalytic particles |

| Penicillin-G Acylase | Model enzyme | Study subject for industrial biocatalyst applications |

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for FESEM Analysis of Biocatalytic Particles

Beyond Imaging: Why This Matters

Optimizing Industrial Processes

The insights gained from FESEM analysis extend far beyond academic curiosity—they drive real-world innovations in industrial biocatalysis. By understanding how enzyme distribution patterns form and affect catalytic efficiency, scientists can now deliberately design particles with optimized enzyme arrangements for specific applications 1 .

For example, processes limited by substrate diffusion might benefit from particles with enzyme-rich surfaces, while reactions susceptible to product inhibition might perform better with more uniform enzyme distributions.

Environmental and Economic Impacts

The implications of optimized biocatalytic particles extend to environmental sustainability and economic efficiency. More efficient catalysts mean:

- Reduced energy consumption in industrial processes

- Higher product yields with less waste

- Decreased production costs for pharmaceuticals and chemicals

- Lower environmental impact through greener manufacturing processes

These advantages align perfectly with the principles of green chemistry and sustainable development 9 .

Future Applications

The lessons learned from FESEM analysis of biocatalytic particles are already finding applications beyond traditional industrial chemistry. Researchers are applying similar principles to develop:

Advanced drug delivery systems

Environmental remediation

Biosensing platforms

Biofuel production

Conclusion: The Future of Biocatalyst Design

The application of field-emission scanning electron microscopy to industrial biocatalytic particles represents more than just a technical achievement—it exemplifies how advances in analytical techniques can drive innovation across multiple industries. By revealing the previously invisible architectural details of these powerful biocatalysts, FESEM has provided scientists with the knowledge needed to design smarter, more efficient, and more sustainable chemical processes.

As we look to the future, the integration of FESEM with other emerging technologies—particularly machine learning and artificial intelligence—promises to accelerate biocatalyst development even further. Researchers can now use the quantitative data from FESEM analyses to build predictive models that guide particle design without exhaustive trial-and-error experimentation 6 9 .

The ongoing revolution in biocatalysis, powered by advanced imaging technologies like FESEM, brings us closer to a future where industrial chemistry operates in harmony with biological systems—creating a more sustainable, efficient, and greener world for generations to come. From breaking down plastic waste to synthesizing life-saving medications, these invisible biological workhorses, now fully revealed through the power of electron microscopy, will undoubtedly play an increasingly vital role in solving some of humanity's most pressing challenges 9 .