Thermostable DNA Polymerases: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Research and Diagnostic Applications

This article provides a systematic comparison of thermostable DNA polymerases, essential enzymes in molecular biology and diagnostic applications.

Thermostable DNA Polymerases: A Comprehensive Performance Comparison for Research and Diagnostic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of thermostable DNA polymerases, essential enzymes in molecular biology and diagnostic applications. It covers the foundational characteristics of fidelity, processivity, thermostability, and specificity, explaining their impact on DNA amplification. The review details methodological applications across clinical diagnostics, genomics, and drug development, including specialized uses in reverse transcription and long-fragment PCR. It offers practical troubleshooting guidance for challenging samples and complex templates, evaluating inhibitor resistance. Finally, it presents a validated, comparative analysis of commercially available and novel engineered polymerases, empowering researchers and drug development professionals to select optimal enzymes for their specific workflows and advance biomedical research.

The Essential Toolkit: Understanding Core Characteristics of Thermostable DNA Polymerases

The selection of an appropriate thermostable DNA polymerase is a critical determinant for the success of virtually all polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based applications. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the choice extends beyond mere amplification capability to how well an enzyme's performance profile aligns with specific experimental goals. Whether the priority is utmost sequence accuracy, amplification of long or complex templates, or the prevention of false-positive results, understanding core enzyme metrics is paramount. This guide provides an objective comparison of thermostable DNA polymerases, focusing on four key performance characteristics—fidelity, processivity, thermostability, and specificity—to inform strategic enzyme selection within modern life science research.

Core Performance Metrics of DNA Polymerases

The performance of DNA polymerases can be quantified through several key metrics, each critical for different applications.

Fidelity: The Accuracy of DNA Synthesis

Fidelity refers to the accuracy with which a DNA polymerase replicates a DNA template, measured as its error rate (number of misincorporated nucleotides per base synthesized) [1]. High-fidelity polymerases are essential for applications like cloning, sequencing, and site-directed mutagenesis, where sequence integrity is crucial [1]. The proofreading activity, or 3′→5′ exonuclease activity, is a major contributor to fidelity, as it allows the enzyme to identify and excise misincorporated nucleotides [1] [2].

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Fidelity: A common method for assessing fidelity is the lacI PCR-based cloning and colony screening assay [1].

- Amplification: A segment of the lacI gene is amplified using the DNA polymerase being tested.

- Cloning: The resulting PCR products are cloned into a suitable plasmid vector.

- Transformation: The plasmids are used to transform E. coli cells, which are then plated on media containing X-Gal.

- Analysis: Colonies with a functional lacI gene (no errors introduced during PCR) appear blue. Colonies with mutated lacI genes (containing errors from PCR) appear white. The error rate is calculated based on the ratio of white to blue colonies [1]. More modern approaches use next-generation sequencing of PCR amplicons to directly identify and quantify misincorporation events with high precision [1].

Processivity: Nucleotides Added per Binding Event

Processivity is defined as the number of nucleotides a DNA polymerase incorporates into a growing DNA strand in a single binding event [1]. A highly processive enzyme is advantageous for amplifying long DNA fragments, GC-rich sequences with strong secondary structures, and for reactions containing PCR inhibitors [1]. Processivity can be enhanced through protein engineering, such as fusing the polymerase to a DNA-binding domain like Sso7d, which increases the enzyme's affinity for the template [1] [3].

Thermostability: Withstanding High Temperatures

Thermostability describes an enzyme's ability to retain its structure and function at high temperatures, a non-negotiable requirement for the repeated denaturation steps in PCR [1]. While Taq polymerase is thermostable, enzymes from hyperthermophilic archaea, such as Pyrococcus furiosus, exhibit superior stability. For example, Pfu DNA polymerase is about 20 times more stable at 95°C than Taq polymerase [1]. This property is vital for protocols involving prolonged high-temperature incubations.

Specificity: Preventing Non-Specific Amplification

Specificity ensures that PCR amplification yields only the desired target product, minimizing artifacts like primer-dimers and amplification from misprimed sites [1]. Hot-start PCR is a key technique to enhance specificity. It involves inhibiting the polymerase's activity during reaction setup at room temperature. Activation occurs only after the first high-temperature denaturation step (>90°C), which degrades the inhibitory antibody or compound [1]. This prevents non-specific synthesis before thermal cycling begins.

Comparative Performance Data of Common DNA Polymerases

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of commonly used thermostable DNA polymerases, providing a direct comparison of their performance metrics [2] [4].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Common Thermostable DNA Polymerases

| Polymerase | Source Organism | Fidelity (Error Rate) | Proofreading (3'→5' Exo) | Processivity | Optimal Extension Temperature | PCR Product Ends |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | Thermus aquaticus (Bacterium) | ~1.5 × 10⁻⁴ [2] | No [2] | Moderate [1] | 74°C [2] | 3'-A Overhang [2] |

| Pfu | Pyrococcus furiosus (Archaeon) | ~1.3 × 10⁻⁶ [2] | Yes [2] | Lower than Taq [1] | 75°C [2] | Blunt [2] |

| TstP36H-Sso7d | Thermococcus stetteri (Archaeon, engineered) | Very High (Higher than Pfu) [3] | Yes [3] | High (amplifies up to 15 kb) [3] | ~75°C (inferred) | Blunt (inferred) |

| KOD | Thermococcus kodakarensis (Archaeon) | ~1.2 × 10⁻⁵ [2] | Yes [2] | High (~120 bp/s synthesis rate) [2] | 75°C [2] | Blunt [2] |

| Bst (LF) | Geobacillus stearothermophilus (Bacterium) | N/A (Not typically for PCR) | No [5] | High (strand-displacing) [5] | 65°C [2] | 3'-A Overhang [2] |

Table 2: Engineered and Hybrid DNA Polymerase Systems

| Polymerase / System | Composition / Type | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start Taq | Antibody-inhibited Taq [1] | High specificity, room-temperature setup, reduced primer-dimer formation [1]. |

| Pfu Ultra | Engineered Pfu variant [2] | Extremely high fidelity (error rate ~4.3 × 10⁻⁷) [2]. |

| Q5 Polymerase | Engineered, high-fidelity [2] | Fusion protein with DNA-binding domain for high processivity and fidelity [2]. |

| Herculase / TaqPlus | Mixture of Taq and Pfu [2] | Balances high processivity of Taq with proofreading of Pfu for long-range PCR [2]. |

Experimental Workflows for Performance Evaluation

The following diagrams and protocols outline standard experimental approaches for evaluating DNA polymerase performance.

Workflow for Testing Hot-Start Specificity

This workflow tests a polymerase's specificity by comparing its performance under standard and hot-start conditions.

Experimental Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare two identical PCR master mixes. To one, add a hot-start DNA polymerase (e.g., antibody-inhibited); to the other, add a non-hot-start version of the same enzyme [1].

- Room-Temperature Challenge: Incubate both reaction sets at room temperature for a prolonged period (e.g., 0, 24, and 72 hours) before placing them in the thermocycler [1].

- Amplification: Run the standard PCR protocol.

- Analysis: Analyze the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. A true hot-start polymerase will show a clean, specific band of the expected size even after 72 hours at room temperature, while the non-hot-start enzyme will show significant smearing and non-specific products under the same conditions [1].

Workflow for Assessing Fidelity

This workflow outlines the process for determining polymerase fidelity using a cloning and sequencing-based assay.

Experimental Protocol: This protocol utilizes the lacI gene system for a functional assessment of fidelity [1].

- Amplification: The lacI gene is amplified by the DNA polymerase being tested.

- Cloning and Transformation: The PCR products are cloned into a vector and transformed into an E. coli host. The transformed cells are plated on media containing X-Gal.

- Screening: Functional lacI gene product results in blue colonies. Mutations introduced during PCR that disrupt the lacI gene result in white colonies.

- Calculation: The error rate is calculated based on the frequency of white colonies. More advanced methods involve direct next-generation sequencing of the amplicons to catalog all errors [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimentation with DNA polymerases requires a set of key reagents and components.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DNA Polymerase Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme engineered for high specificity, activated only at high temperatures to prevent non-specific amplification during reaction setup [1]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme with high proofreading activity (e.g., Pfu, TstP36H-Sso7d) for applications requiring low error rates, such as cloning and sequencing [3] [4]. |

| PCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed, optimized solution containing buffer, dNTPs, and MgCl₂. Saves time, reduces contamination risk, and improves reproducibility [6] [7]. |

| dNTP Mix | A solution containing equimolar amounts of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; the building blocks for DNA synthesis. |

| Optimized Reaction Buffer | A buffering system (often supplied with the enzyme) that provides optimal pH, salt conditions, and Mg²⁺ concentration for polymerase activity. |

| DNA Ladder | A molecular weight marker used in gel electrophoresis to estimate the size of amplified PCR products. |

| Agarose | A polysaccharide used to create gels for the electrophoretic separation and analysis of DNA fragments. |

Future Directions in DNA Polymerase Engineering

The field of DNA polymerase engineering is rapidly advancing to meet the demands of novel biotechnology applications. Key future directions include:

- Engineering for Modified Templates: Developing polymerases that can efficiently amplify and sequence DNA containing damaged bases or epigenetic modifications (e.g., methylated cytosine) for clinical and ancient DNA analysis [8].

- Chimeras and Directed Evolution: Creating novel enzyme chimeras and using advanced directed evolution techniques (e.g., Compartmentalized Self-Replication - CSR) to engineer polymerases with tailor-made properties, such as extreme resistance to inhibitors found in blood or soil samples, or altered substrate specificity for synthetic biology [8] [3].

- AI-Enhanced Enzyme Design: Leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning to predict polymerase structure-function relationships, thereby accelerating the design of enzymes with enhanced speed, fidelity, and application-specific performance [7].

The landscape of thermostable DNA polymerases offers a diverse toolkit for the modern researcher. There is no single "best" polymerase; rather, the optimal choice is dictated by the specific requirements of the experiment. A strategic selection process, grounded in a clear understanding of fidelity, processivity, thermostability, and specificity, is crucial. As polymerase engineering continues to evolve, the availability of ever-more-specialized enzymes will further empower scientific discovery and innovation in drug development and diagnostic applications.

Thermostable DNA polymerases are indispensable tools in modern molecular biology, serving as the core engines for techniques ranging from basic PCR to advanced diagnostics and gene sequencing. The natural diversity of enzymes sourced from thermophilic microorganisms provides a rich reservoir of distinct biochemical properties. Thermus aquaticus, Pyrococcus furiosus, and Thermococcus kodakarensis represent three foundational genera that have yielded polymerases with unique and complementary characteristics. This guide provides a performance comparison of native and engineered DNA polymerases from these species, offering experimental data and methodologies to help researchers select the optimal enzyme for their specific applications. The continuous engineering of these native scaffolds—enhancing their reverse transcriptase activity, fidelity, and processivity—demonstrates how natural diversity remains a critical foundation for biotechnology innovation [9] [10] [11].

Comparative Analysis of Native and Engineered Polymerases

The following tables summarize the key characteristics and performance metrics of DNA polymerases derived from Thermus, Pyrococcus, and Thermococcus species, including both native and engineered variants.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Polymerases from Different Genera

| Genus/Species | Polymerase Name | Native/Engineered | Key Features | 3'→5' Exonuclease (Proofreading) | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermus aquaticus | Taq | Native | Thermostable, 5'→3' polymerase, 5'→3' exonuclease | No | Standard PCR, DNA amplification [10] |

| Thermus aquaticus | KlenTaq (KTq) | Native (N-terminal truncation) | 5'→3' polymerase, lacks 5'→3' nuclease activity | No | DNA sequencing, primer extension [9] |

| Thermus aquaticus | RevTaq, RT-Taq | Engineered | Enhanced reverse transcriptase activity for one-step RT-PCR | No | One-tube RT-PCR, molecular diagnostics [9] [10] |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | Pfu | Native | High fidelity, thermostable | Yes | High-fidelity PCR, cloning [12] [13] |

| Pyrococcus furiosus | Pfu-M6 | Engineered | Acquired reverse transcriptase activity, thermostable | Yes | One-enzyme RT-PCR [11] |

| Thermococcus kodakarensis | KOD | Native | High processivity, high fidelity, fast | Yes | Fast, high-fidelity PCR, long amplicons [14] |

| Thermococcus kodakarensis | KOD-GT4G-Sto7d | Engineered (Fusion) | Fused to dsDNA-binding protein Sto7d, enhanced processivity | Yes | Time-saving PCR, high-demand applications [14] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison

| Polymerase | Error Rate (Relative Fidelity) | Elongation Speed (sec/kb) | Optimal Elongation Temp. | Salt Tolerance | Recommended Amplicon Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq (Native) | ~1 × 10⁻⁵ [15] | 60 | 72°C | Low | < 5 kb [13] |

| Pfu (Native) | ~1 × 10⁻⁶ [15] [13] | 60-120 | 72°C | Moderate | < 10 kb |

| KOD (Native) | High (Similar to Pfu) [14] | 10-15 | 70-75°C | High (up to 120 mM NaCl) [14] | Up to 10 kb in 4 min [14] |

| KOD-GT4G-Sto7d | High (Retained fidelity) [14] | ~10 | 70-75°C | Very High | Up to 10 kb [14] |

| Tt72 (Phage on T. thermophilus) | ~1.41 × 10⁻⁵ [15] | Information Missing | 55-70°C [15] | Information Missing | Specialized cloning |

Table 3: Reverse Transcriptase (RT) Proficiency in Engineered Polymerases

| Polymerase | RT Activity Source | Key Mutations/Fusions | Probe Compatibility | Multiplex RT-PCR Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RevTaq / RT-Taq | Engineered Taq scaffold | L459M, S515R, I638F, M747K [9] | Yes (TaqMan probes) [9] | Yes (Quadruplex) [9] |

| OmniTaq2 | Engineered Taq scaffold | Single substitution D732N [10] | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| ReverHotTaq | Taq-Bst chimeric | Incorporates Bst polymerase fragments [10] | Information Missing | Information Missing |

| Pfu-M6 | Engineered Pfu scaffold | Multiple substitutions in palm and exonuclease domains [11] | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

To ensure reproducibility and provide a framework for independent validation, this section details key experimental methodologies cited in the comparison data.

Fidelity Measurement vialacZαComplementation Assay

The error rates of DNA polymerases can be quantitatively compared using a plasmid-based fidelity assay [15].

- Principle: The polymerase is used to amplify the lacZα gene in vitro. The resulting PCR products are then cloned into a suitable vector and transformed into an E. coli host. The functional lacZα gene produces blue colonies in the presence of X-gal, while colonies containing mutations that inactivate the gene appear white.

- Procedure:

- Amplification: The lacZα template is amplified using the target polymerase under standard conditions.

- Cloning: The PCR products are ligated into a plasmid vector and introduced into competent E. coli cells.

- Plating and Screening: Transformants are plated on media containing X-gal and IPTG. After incubation, blue and white colonies are counted.

- Calculation: The mutation frequency (MF) is calculated as (Number of white plaques / Total number of plaques). The error rate is then derived from the MF using a established statistical model [15].

- Key Reagents: lacZα-containing plasmid, competent E. coli cells (e.g., DH5α), X-gal, IPTG, ligation kit.

Evaluating Reverse Transcriptase Proficiency in Engineered Polymerases

The acquisition of efficient RT activity in engineered DNA polymerases is crucial for one-step RT-PCR applications [9] [11].

- Principle: A single-enzyme RT-PCR is performed using an RNA template. Successful amplification of a specific cDNA product demonstrates combined RT and DNA polymerase activity.

- Procedure (as used for Taq variants):

- Reaction Setup: A one-tube reaction is prepared containing the target polymerase, reaction buffer, dNTPs, primers, and TaqMan probes specific for an RNA target (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 RNA).

- Thermocycling: The reaction is run in a real-time PCR instrument. The protocol typically includes a reverse transcription step (e.g., 50°C for 15-30 minutes) followed by standard PCR cycling.

- Analysis: Successful amplification, evidenced by a characteristic fluorescence curve and a low detection limit (e.g., 20 copies of RNA), confirms proficient RT activity. Compatibility with hydrolysis probes and the ability to perform multiplex detection (multiple targets in one reaction) are key performance indicators [9].

- Key Reagents: Target RNA (e.g., viral RNA, total RNA), primers and TaqMan probes, one-step RT-PCR reaction buffer, real-time PCR instrument.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents required for experiments involving thermostable DNA polymerases, as featured in the cited studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Polymerase Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable DNA Polymerases | Enzyme for catalyzing DNA synthesis at high temperatures. | PCR, RT-PCR [9] [10] |

| Defined Reaction Buffers | Provides optimal pH, salt, and co-factor conditions for enzyme activity. | Specific buffers for RevTaq, OmniTaq2, etc. [10] |

| dNTP Mix | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) are the building blocks for DNA synthesis. | Standard component of any PCR or RT-PCR [10] |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end of the amplification target. | Target-specific amplification [9] [10] |

| TaqMan Hydrolysis Probes | Fluorescently labeled probes for specific detection of amplification products in real-time PCR. | Quantitative real-time RT-PCR [9] [10] |

| RNA Templates | The target molecule for reverse transcription, such as viral RNA or total mRNA. | Testing RT activity in engineered polymerases [9] [10] |

| lacZα Complementation System | Plasmid, E. coli strain, and substrates (X-gal/IPTG) for measuring polymerase fidelity. | Determining error rates of different polymerases [15] |

| Expression Vectors (e.g., pET series) | Plasmids for recombinant expression of polymerase genes in host systems like E. coli. | Production of recombinant native or engineered polymerases [16] [11] |

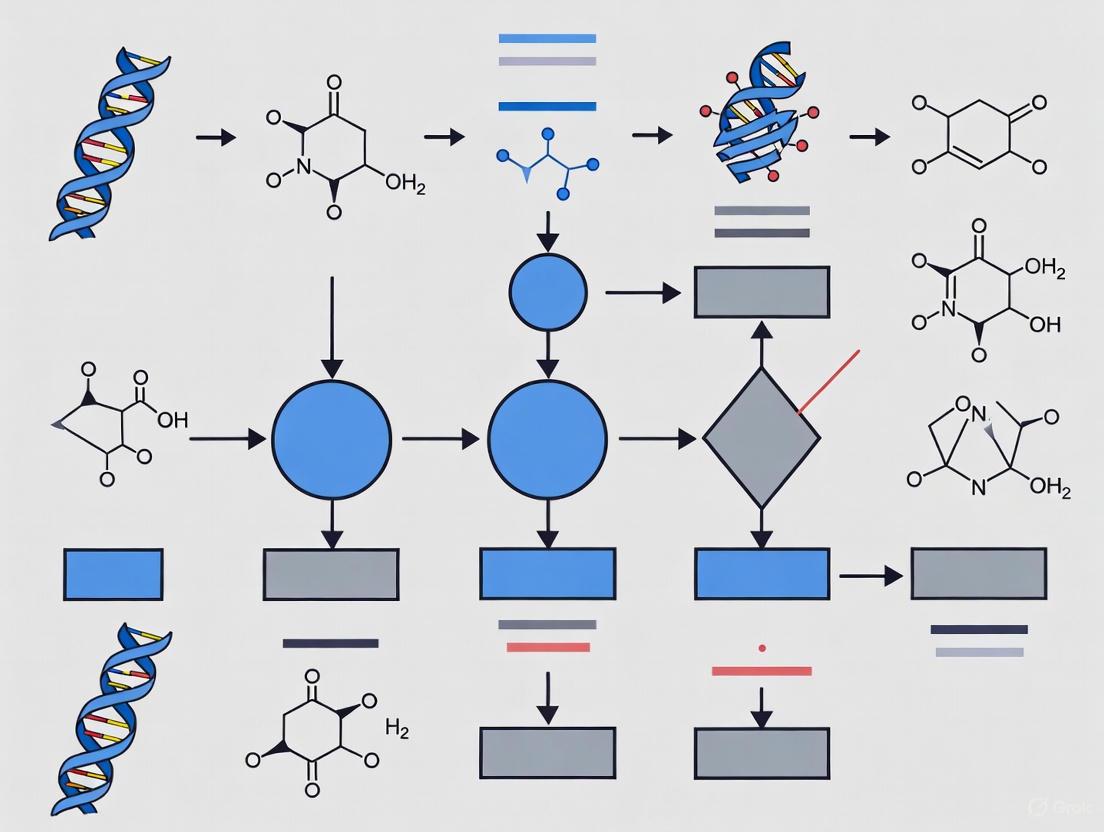

Polymerase Engineering and Functional Relationships

The engineering of novel polymerase functions often involves rational design or directed evolution based on natural scaffolds. The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow and relationships between native polymerases and their engineered variants.

Polymerase Engineering Pathways: This diagram illustrates the engineering pathways from native polymerase scaffolds to novel variants with enhanced functionalities. The process often begins with rational design, where specific mutations are introduced based on structural knowledge to confer new activities, such as the reverse transcriptase function in RevTaq and Pfu-M6 [9] [11]. Alternatively, fusion protein strategies link the polymerase to DNA-binding domains like Sto7d, significantly boosting processivity and salt tolerance, as seen in KOD-Sto7d [14]. A library and recombination approach, combining beneficial mutations from different variant lineages, was successfully used to develop the advanced RT-Taq variants [9]. These engineering efforts directly enable advanced application outcomes, including simplified one-step RT-PCR, multiplex target detection, and efficient amplification of long DNA fragments.

In the realm of molecular biology, the precision of DNA replication is paramount. DNA polymerase fidelity refers to the enzyme's accuracy in selecting correct nucleotides during DNA synthesis, a critical property that ensures the integrity of genetic information. Thermostable DNA polymerases, indispensable for techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), span a broad spectrum of accuracy, from non-proofreading enzymes to high-fidelity proofreading enzymes. The division between these categories fundamentally hinges on the presence or absence of 3'→5' exonuclease activity, a proofreading function that excises misincorporated nucleotides, thereby dramatically reducing error rates [17].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate polymerase is not a trivial decision. The choice has profound implications for the success of downstream applications, from routine gene cloning to large-scale synthetic biology and diagnostic assay development. An enzyme's error rate can introduce unintended mutations, compromising experimental results, therapeutic protein function, and diagnostic reliability. This guide provides a performance comparison of thermostable DNA polymerases, underpinned by experimental data, to inform strategic enzyme selection for your research needs.

Enzyme Fidelity Comparison and Performance Data

The fidelity of DNA polymerases is quantitatively expressed as an error rate, representing the number of mutations incorporated per base pair per duplication event. As shown in Table 1, these rates vary by orders of magnitude, creating a clear fidelity hierarchy among enzymes commonly used in molecular biology [18].

Table 1: Error Rate Comparison of DNA Polymerases

| Enzyme | Proofreading Activity | Published Error Rate (errors/bp/duplication) | Relative Fidelity (vs. Taq) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase | No | 1.0 - 2.0 × 10⁻⁵ | 1x | Standard for routine PCR; lower accuracy [18] |

| AccuPrime-Taq HF | No | ~1.0 × 10⁻⁵ | ~9x better than Taq | Engineered for higher fidelity without proofreading [18] |

| KOD Hot Start | Yes | ~10⁻⁶ range | >50x better than Taq | High processivity and speed [18] |

| Pfu Polymerase | Yes | 1.0 - 2.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 6-10x better than Taq | Archetypal high-fidelity enzyme [18] |

| Phusion Hot Start | Yes | 4.0 × 10⁻⁷ (HF buffer) | >50x better than Taq | One of the highest fidelity enzymes available [18] |

| Platinum SuperFi II | Yes | >300x Taq fidelity | >300x better than Taq | Engineered enzyme with superior accuracy and simplified workflow [17] |

Beyond the core error rate, other performance metrics are crucial for selecting an enzyme for specific experimental conditions. These include the ability to amplify long fragments, handle complex secondary structures, and tolerate common PCR inhibitors.

Table 2: Functional Performance of DNA Polymerases

| Enzyme | Processivity & Amplicon Length | GC-Rich Amplification | Inhibitor Tolerance | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase | Moderate; typically up to 3-4 kb | Standard performance | Low | Routine PCR, genotyping |

| Pfu Polymerase | High; up to 10+ kb | Good | Moderate | High-fidelity cloning, mutagenesis |

| Phusion Hot Start | High; up to 20+ kb | Excellent with GC buffer | High | Long-range PCR, complex templates |

| Platinum SuperFi II | High; demonstrated up to 14 kb [17] | Robust [17] | High (tolerant to humic acid, hemin, bile salt) [17] | High-throughput cloning, sequencing, mutagenesis [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Fidelity Assessment

A true comparison of polymerase fidelity requires standardized experimental methodologies. Direct sequencing of cloned PCR products across a wide array of template sequences is considered a robust approach, as it interrogates errors across a vast DNA sequence space, revealing sequence context-dependent biases [18].

Direct Sequencing Protocol for Error Rate Measurement

This protocol is adapted from a study that sequenced 94 unique plasmid templates to comprehensively evaluate error rates [18].

- Template Preparation: Utilize a diverse set of plasmid templates (e.g., 94 unique sequences with a median insert size of 1.4 kb and GC content of 44%). This diversity is critical to account for sequence-context effects on error rate.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify targets using a high cycle number (e.g., 30 cycles) to maximize the number of template doublings and amplify any potential errors. Use small amounts of plasmid template (e.g., 25 pg per reaction). Employ a standardized protocol with a 2-minute extension per cycle for targets ≤2 kb.

- Product Cloning: Purify PCR products and clone them into a suitable vector using a high-efficiency cloning system (e.g., Gateway recombination or traditional restriction/ligation).

- Sequencing and Analysis: Pick individual colonies and Sanger sequence the entire inserted amplicon. Align sequences to the known reference template.

- Error Rate Calculation: Calculate the error rate using the formula: Error Rate = (Total Number of Mutations Observed) / (Total bp Sequenced × Number of Template Doublings). The number of doublings is calculated from the fold-amplification of the PCR reaction [18].

Simplified Workflow with Modern High-Fidelity Enzymes

Recent enzyme engineering has yielded polymerases like Platinum SuperFi II, which streamline protocols while maintaining high accuracy. A key innovation is a buffer formulation that enables a universal primer annealing temperature of 60°C, regardless of primer sequence [17].

- Protocol: A single thermocycling protocol can be used for multiple targets: 98°C denaturation for 10 sec, 60°C annealing for 10 sec, and 72°C extension. The extension time is set based on the longest fragment in the multiplex reaction (e.g., 7 minutes for a 14 kb fragment) [17].

- Benefit: This "co-cycling" capability saves significant time and simplifies experimental setup, especially in high-throughput environments, without compromising specificity or yield [17].

The following diagram illustrates the key experimental workflow for assessing polymerase fidelity using the direct sequencing method.

Figure 1: Workflow for direct sequencing-based fidelity assessment.

Analysis of Fidelity Mechanisms and Mutation Spectra

The stark difference in error rates between non-proofreading and proofreading enzymes is a direct consequence of their molecular mechanisms. Taq polymerase, lacking 3'→5' exonuclease activity, relies solely on its intrinsic nucleotide selectivity. Once a wrong nucleotide is incorporated, it is permanently fixed into the DNA strand, leading to a high final error rate of ~10⁻⁵ [18].

In contrast, high-fidelity proofreading enzymes like Pfu, Phusion, and Platinum SuperFi II operate a two-tiered accuracy system. First, they possess high intrinsic selectivity. Second, and most critically, their 3'→5' exonuclease "proofreading" domain actively scans the newly synthesized DNA. Upon detecting a misincorporated nucleotide (a geometric distortion in the DNA helix), the enzyme reverses direction, excises the incorrect base, and then resumes synthesis, providing a second opportunity for correct incorporation [17]. This mechanism reduces error rates to the ~10⁻⁶ range and lower.

The types of mutations generated, or the "mutation spectrum," also differ. Studies comparing enzymes like Pfu, Phusion, and Pwo have found that they produce broadly similar spectra, with transition mutations (e.g., purine to purine) predominating [18]. Understanding the mutation spectrum is valuable for designing validation strategies for cloned PCR products.

The following diagram contrasts the fundamental biochemical pathways of non-proofreading and proofreading DNA polymerases.

Figure 2: Mechanisms of non-proofreading vs. proofreading polymerases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful high-fidelity PCR experiment depends on more than just the choice of polymerase. Key reagents and materials form an integrated system that supports optimal enzyme performance and accurate downstream analysis.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High-Fidelity PCR Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function & Importance | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes accurate DNA synthesis; the core component of the reaction. | Choose based on required balance of fidelity, speed, and robustness (e.g., Platinum SuperFi II for highest accuracy, Phusion for long amplicons) [17] [18]. |

| Optimized Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength, and co-factors (like Mg²⁺) for polymerase activity and specificity. | Proprietary buffers (e.g., Platinum SuperFi II buffer with universal 60°C annealing) can simplify protocols and enhance performance [17]. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis. | Use high-quality, neutral-pH dNTPs at balanced concentrations to prevent misincorporation. |

| Template DNA | The sequence to be amplified. | Purity and integrity are critical. For fidelity tests, a diverse set of plasmid templates is used to sample different sequence contexts [18]. |

| Primers | Short oligonucleotides that define the start and end of the amplicon. | Design primers with appropriate melting temperatures and avoid secondary structures to ensure specific binding. |

| Cloning Kit (e.g., Gateway) | For inserting PCR products into vectors for sequencing and functional analysis. | Essential for the direct sequencing fidelity assay protocol to isolate individual molecules for sequencing [18]. |

| Agarose Gels & Electrophoresis System | For size-based separation and qualitative analysis of PCR products. | The Platinum SuperFi II Green Master Mix allows for direct gel loading, reducing pipetting steps and potential errors [17]. |

The journey from non-proofreading to high-fidelity proofreading enzymes represents a cornerstone of advancement in molecular biology. The data and protocols presented here underscore that the choice of polymerase is a fundamental experimental variable. While Taq polymerase remains a cost-effective choice for routine applications where ultimate accuracy is not critical, the use of high-fidelity enzymes like Phusion, Pfu, and the engineered Platinum SuperFi II is non-negotiable for applications such as cloning, sequencing, mutagenesis, and the development of molecular diagnostics where sequence integrity is paramount [17] [18].

The market evolution reflects this understanding, with a projected growth in the DNA polymerase market, driven by the surge in genomics, personalized medicine, and the need for precise molecular diagnostics [19] [20] [21]. The ongoing engineering of enzymes, offering not only superior fidelity but also simplified workflows, robust performance, and inhibitor tolerance, directly empowers researchers and drug developers to achieve more reliable and reproducible results. By strategically selecting enzymes from across the fidelity spectrum, the scientific community can continue to push the boundaries of genetic research and therapeutic development with greater confidence.

Conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) represents a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet it suffers from a critical limitation: DNA polymerases exhibit significant enzymatic activity at room temperature. This residual activity facilitates non-specific amplification during reaction setup through mis-priming (primers binding to template sequences with low homology) and primer-dimer formation (primers binding to each other) [22]. These non-specific products compete with the target sequence for reagents, substantially reducing amplification efficiency, yield, and sensitivity—a limitation particularly problematic for low-copy-number targets and diagnostic applications [22].

Hot-Start PCR addresses this fundamental challenge by employing specialized mechanisms to inhibit DNA polymerase activity during reaction setup at room temperature. The core principle involves blocking polymerase function until a critical "hot start" temperature is reached during the initial denaturation step, typically >90°C [23]. This temperature-dependent activation prevents amplification during non-stringent conditions, ensuring that primer extension only initiates when the reaction mixture reaches temperatures that promote specific primer-template hybridization [24]. The strategic delay dramatically improves amplification specificity, sensitivity, and yield by preventing the accumulation of non-specific products during the crucial early cycles where amplification errors become exponentially amplified [24].

Comparative Analysis of Hot-Start Mechanisms

Antibody-Based Inhibition

Mechanism of Action: Antibody-based Hot-Start PCR utilizes monoclonal antibodies that specifically bind to the active site of DNA polymerases, forming a physical barrier that blocks substrate access at room temperature [24]. This antibody-polymerase complex remains inactive until the initial high-temperature denaturation step in the PCR cycle, where the antibody denatures and dissociates from the polymerase, releasing the enzyme's active site for DNA synthesis [22].

Activation Profile: This system features rapid activation, typically requiring only 1-3 minutes at the initial denaturation temperature (usually 94-95°C) to achieve complete polymerase activation [24]. Once activated, the polymerase behaves identically to conventional enzymes, with no residual inhibition affecting subsequent amplification cycles.

Advantages and Limitations: The primary advantage of antibody-based systems lies in their rapid activation kinetics and complete reversal of inhibition [24]. However, potential limitations include the animal origin of antibodies, which might raise concerns for certain applications, and possible interference in mammalian target DNA amplification due to higher antibody content in reactions [24].

Chemical Modification

Mechanism of Action: Chemically modified Hot-Start polymerases employ covalent attachment of heat-labile chemical groups to critical amino acid residues in the enzyme's active site [24]. These chemical modifiers sterically hinder substrate binding at lower temperatures, effectively inactivating the enzyme during reaction setup.

Activation Profile: Chemical inhibition requires longer activation times compared to antibody-based methods, often exceeding 10 minutes at elevated temperatures [24]. This prolonged heating may potentially damage DNA templates, particularly for longer amplicons (>3kb). Additionally, these systems may exhibit gradual activation characteristics, with some polymerase molecules remaining inactive during initial cycles and activating progressively throughout the amplification process [24].

Advantages and Limitations: Key advantages include superior stability at room temperature and reduced contamination risk [24]. The primary limitations center on extended activation requirements and potential incomplete reactivation, where some polymerase molecules may remain modified and inactive throughout the amplification process [24].

Aptamer-Based Inhibition

Mechanism of Action: Aptamer-based inhibition utilizes specific oligonucleotide sequences (aptamers) that bind with high affinity to DNA polymerases, blocking enzymatic activity through steric hindrance at lower temperatures [22]. Similar to antibody-based systems, these aptamers dissociate from the polymerase during the initial denaturation step, restoring enzymatic function.

Activation Profile: This method offers the fastest activation kinetics among commercial Hot-Start technologies, typically requiring only 30 seconds at high temperatures [24]. The rapid activation minimizes template exposure to potentially damaging high temperatures.

Advantages and Limitations: The principal advantages include rapid activation and non-animal origin of inhibitory aptamers [24]. The primary limitation involves potentially less stringent binding compared to antibodies, which might result in premature activation or non-specific amplification in some cases [24].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Hot-Start PCR Mechanisms

| Feature | Antibody-Based | Chemical Modification | Aptamer-Based |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor Type | Monoclonal antibodies | Heat-labile chemical groups | Oligonucleotides (aptamers) |

| Activation Time | 1-3 minutes | >10 minutes | ~30 seconds |

| Activation Completeness | Complete | May be incomplete | Complete |

| Inhibitor Origin | Animal | Synthetic | Synthetic |

| Key Advantage | Rapid, complete activation | Room-temperature stability | Fastest activation, non-animal origin |

| Primary Limitation | Potential interference with mammalian DNA | Potential template damage, incomplete activation | Less stringent binding |

Experimental Comparison and Performance Data

Methodology for Performance Evaluation

Experimental Design: Comparative evaluation of Hot-Start PCR systems requires standardized amplification conditions using identical template DNA, primer sets, and thermal cycling parameters. Typical protocols utilize serial dilutions of target DNA (genomic DNA, plasmid clones, or synthetic fragments) to assess sensitivity across a concentration range from 10 ng to 10 pg [10]. Reaction mixtures should contain standardized concentrations of dNTPs (typically 0.25 mM each), primers (0.3 μM each), and appropriate buffer components according to manufacturer specifications [10].

Specificity Assessment: Specificity is evaluated through parallel amplification of targets with varying degrees of sequence complexity, including human genomic DNA, viral RNA (e.g., SARS-CoV-2), and endogenous mRNA molecules (e.g., GAPDH, beta-2-microglobulin) [10]. Non-specific amplification is quantified through post-amplification analysis methods including gel electrophoresis with densitometry, quantitative real-time PCR efficiency calculations, and high-resolution melt curve analysis [10].

Yield Quantification: Amplification yield is determined through multiple methods including UV spectrophotometry, fluorometric assays, and capillary electrophoresis. For real-time applications, amplification efficiency is calculated from standard curves generated using serial template dilutions, with optimal efficiency ranging from 90-105% [10].

Performance Data Analysis

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Hot-Start PCR Systems

| Performance Metric | Antibody-Based | Chemical Modification | Conventional PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specific Products | Significantly reduced | Moderately reduced | Prevalent |

| Primer-Dimer Formation | Minimal | Minimal | Significant |

| Sensitivity (Detection Limit) | 10-100 copies | 10-100 copies | 100-1000 copies |

| Amplification Yield | High | Moderate to High | Variable |

| Inhibition Relief | Complete after activation | Gradual, may be incomplete | Not applicable |

Recent comparative studies demonstrate that antibody-based Hot-Start systems consistently outperform conventional PCR across all specificity metrics, with up to 10-fold improvement in detection sensitivity for low-copy-number targets [10]. Engineering approaches focusing on polymerase mutations (e.g., S515R, L459M, I638F, M747K in RevTaq; D732N in OmniTaq2) further enhance performance by conferring additional properties such as reverse transcriptase activity and improved strand displacement capability [10].

Advanced Applications and Workflow Integration

Specialized PCR Applications

Hot-Start mechanisms provide particular advantages in specialized PCR applications where specificity is paramount:

Multiplex PCR: Simultaneous amplification of multiple targets requires exceptional specificity to prevent cross-reactivity among primer pairs. Hot-Start technology, particularly antibody-based systems, enables robust multiplexing by preventing mis-priming between numerous primers present in the reaction mixture [23].

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR): Coupled reverse transcription and PCR amplification presents unique challenges, as reverse transcriptases can inhibit Taq polymerase activity [10]. Engineered Hot-Start polymerases with built-in reverse transcriptase activity (e.g., RevTaq, OmniTaq2, ReverHotTaq) enable single-enzyme RT-PCR, simplifying reaction assembly while maintaining specificity [10].

High-Throughput Screening: The room-temperature stability of chemically modified Hot-Start systems facilitates automated reaction setup for high-throughput applications, as the polymerase remains inactive during robotic liquid handling procedures [23].

Diagnostic and Research Applications

The diagnostic applications of Hot-Start PCR are particularly valuable in clinical microbiology, virology, and genetic testing. Recent evaluations have demonstrated the effectiveness of Hot-Start systems in SARS-CoV-2 detection, with engineered polymerases showing compatibility with both endpoint and real-time RT-PCR platforms [10]. While these specialized enzymes perform adequately for diagnostic applications, studies indicate limitations in long-fragment RT-PCR amplification, suggesting context-dependent selection criteria [10].

The following workflow illustrates the implementation of Hot-Start PCR in a diagnostic setting:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of Hot-Start PCR requires careful selection of reagents and optimization strategies. The following toolkit outlines essential components and their functions:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hot-Start PCR Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerases | Platinum Taq, AccuStart Taq (antibody-based); HotStart-IT (chemical modification) | Core enzymatic component; selection depends on required activation speed and application |

| Reaction Buffers | MgCl₂-containing buffers with stabilizers | Provides optimal ionic environment; Mg²⁺ concentration often requires optimization |

| PCR Enhancers | DMSO, formamide, BSA, Tween-20, glycerol | Reduces secondary structure, counteracts inhibitors; concentration must be optimized |

| Nucleic Acid Templates | Genomic DNA, cDNA, viral RNA | Quality and purity significantly impact amplification efficiency |

| Detection Systems | SYBR Green, TaqMan probes, EvaGreen | Enables real-time monitoring and quantification; probe-based methods increase specificity |

Optimization Strategies: Effective Hot-Start PCR implementation requires systematic optimization of several parameters. Magnesium concentration (typically 1.5-3.0 mM) significantly influences specificity and yield, with titration recommended for each new primer-template system [25]. Annealing temperature optimization through gradient PCR (typically 2-5°C below primer Tm) enhances specificity, while extension time should be calibrated to amplicon length (approximately 1 minute per kb) [23]. Additives including DMSO (3-10%), formamide (1-5%), and BSA (0.1-0.5 mg/mL) can improve amplification of difficult templates, particularly those with high GC content or secondary structure [25].

Hot-Start PCR technologies represent a significant advancement in molecular amplification methods, addressing fundamental limitations of conventional PCR through sophisticated inhibition mechanisms. Antibody-based systems offer rapid, complete activation ideal for diagnostic applications and multiplex assays, while chemically modified enzymes provide superior room-temperature stability advantageous for high-throughput workflows. Aptamer-based methods present an emerging alternative with rapid activation kinetics and synthetic origin.

The selection of appropriate Hot-Start methodology depends on specific application requirements, with diagnostic applications favoring antibody-based systems for their robust performance and consistent activation, while research applications with complex templates may benefit from the gradual activation profile of chemically modified enzymes. Continuing engineering efforts focused on polymerase mutations and novel inhibition strategies promise further enhancements to specificity, sensitivity, and utility across diverse molecular biology applications.

The Impact of Accessory Domains and Protein Engineering on Enzyme Performance

In molecular biology, DNA polymerases are indispensable enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA strands, serving as the fundamental workhorses for techniques ranging from basic PCR to advanced next-generation sequencing. The performance of these enzymes directly determines the accuracy, efficiency, and reliability of genetic analysis. Within the global DNA polymerase market—projected to reach USD 420 million in 2025 and USD 721.42 million by 2034—innovation is increasingly driven by strategic enhancements to the enzymes themselves [6]. This article examines how accessory domain integration and sophisticated protein engineering approaches are collectively transforming the capabilities of thermostable DNA polymerases, enabling researchers to overcome longstanding technical barriers in molecular diagnostics and genetic research.

The pursuit of enhanced enzyme performance is not merely academic; it addresses critical market needs for more precise genetic analysis, cost-effective diagnostic solutions, and specialized enzymes for emerging applications like point-of-care testing and gene editing [19] [6]. As the industry shifts toward customized DNA polymerases, understanding the molecular strategies behind these engineering advancements becomes crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals selecting enzymes for specific workflows [19].

Accessory Domains and Protein Engineering Strategies

The Functional Roles of Accessory Domains

Accessory domains are discrete protein modules that augment the functionality of catalytic domains without directly participating in the primary chemical reaction. In DNA polymerases and other enzymes, these domains serve critical roles in substrate recognition, structural stability, and spatial organization. The strategic incorporation of accessory domains represents a powerful tool for expanding enzyme functionality and tailoring catalytic properties for specialized applications.

The modular nature of accessory domains enables a "plug-and-play" approach to enzyme design. Research across enzyme families demonstrates that domains with specific functionalities can be combined to create recombinant proteins with customized properties [26]. For example, in carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) serve as compact yet potent accessories that guide catalytic domains to their target substrates, significantly enhancing catalytic efficiency [27]. Similarly, studies on β-glucosidases from Aspergillus and Streptomyces reveal diverse domain architectures where accessory fibronectin type III (Fn3) and carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM2) domains are fused to glycoside hydrolase family 3 (GH3) catalytic domains, potentially influencing substrate specificity and enzymatic performance [28].

In bacterial secretion systems, accessory proteins containing domains of unknown function (DUF4123) have evolved to recognize structurally diverse effector proteins, demonstrating how accessory domains can expand the functional repertoire of molecular machinery [29]. These principles are now being applied to DNA polymerase engineering, where strategic fusion of functional domains creates enzymes with enhanced capabilities for specific research and diagnostic applications.

Protein Engineering Approaches for DNA Polymerases

Protein engineering of DNA polymerases employs both rational design and directed evolution to enhance key enzymatic properties. The primary goals include improving thermostability, increasing fidelity (replication accuracy), enhancing processivity (nucleotides added per binding event), and conferring specialized functions like reverse transcriptase activity.

Thermostability engineering focuses on maintaining structural integrity and catalytic function at elevated temperatures essential for PCR. This involves introducing mutations that stabilize the protein core, often through strategies like optimizing salt bridges, enhancing hydrophobic packing, and introducing disulfide bonds [10].

Fidelity enhancement targets the polymerase's proofreading capability. High-fidelity enzymes such as New England Biolabs' Q5 polymerase achieve error rates 280-fold lower than standard Taq polymerase through strategic mutations that improve nucleotide selection and exonucleolytic proofreading [30]. These advancements are particularly valuable for next-generation sequencing applications where accuracy is paramount.

Functional expansion represents perhaps the most innovative engineering approach. By incorporating specific mutations or fusion domains, engineers create polymerases with entirely new capabilities. The development of engineered DNA polymerases with reverse transcriptase activity exemplifies this trend, enabling single-enzyme reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) [10]. Specific examples include:

- RevTaq (myPOLS Biotec): Contains four substitutions (S515R, L459M, I638F, M747K) that confer efficient reverse transcriptase activity while maintaining thermostability [10].

- OmniTaq2 (DNA Polymerase Technology, Inc.): Features a single D732N substitution that provides both strand displacement and reverse transcriptase activities [10].

- ReverHotTaq (Bioron GmbH): Created by incorporating fragments from Bst DNA polymerase into Taq polymerase, combining strand displacement and reverse transcriptase activities with high thermostability [10].

These engineering strategies demonstrate how targeted modifications to polymerase structure can overcome natural functional limitations, creating multifunctional enzymes that streamline molecular workflows.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Engineered DNA Polymerases

Experimental Framework for Polymerase Evaluation

The comparative assessment of engineered DNA polymerases requires standardized experimental protocols that evaluate performance across multiple parameters. The following methodology, adapted from published comparisons, provides a framework for objective polymerase evaluation [10]:

Endpoint RT-PCR Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: 25 µL reactions containing 0.25 mM dNTPs, 0.3 µM primers, 1X concentration of test polymerase, and template RNA (e.g., 10 pg-10 ng human total RNA or SARS-CoV-2 RNA).

- Thermal Cycling: Reverse transcription at 50-60°C for 10-30 minutes; initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes; 35-40 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 15-30 seconds), annealing (55-65°C, 15-30 seconds), and extension (68-72°C, 30-60 seconds/kb); final extension at 68-72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Analysis: Gel electrophoresis to assess amplification yield, specificity, and product size.

Real-Time RT-PCR Protocol:

- Reaction Composition: Similar to endpoint RT-PCR but including fluorescent detection chemistry (SYBR Green or TaqMan probes).

- Thermal Profiling: Optimized cycling conditions compatible with real-time detection platforms.

- Analysis: Standard curve generation for quantification efficiency assessment; Cq value comparison for sensitivity determination; melt curve analysis for amplicon specificity verification.

Performance Metrics:

- Amplification Efficiency: Calculated from standard curve slopes.

- Sensitivity: Limit of detection (LOD) determination using serial template dilutions.

- Specificity: Evaluation of non-specific amplification products.

- Processivity: Maximum amplifiable fragment length assessment.

- Inhibitor Tolerance: Performance in presence of common PCR inhibitors.

Quantitative Comparison of Engineered DNA Polymerases

The table below summarizes experimental data comparing the performance of commercially available engineered DNA polymerases with reverse transcriptase activity against conventional enzyme mixtures:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Engineered DNA Polymerases with Reverse Transcriptase Activity

| Polymerase | Engineering Strategy | RT Efficiency | DNA Amplification Performance | Optimal Template Type | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RevTaq [10] | Taq mutant with 4 substitutions (S515R, L459M, I638F, M747K) | High | Robust amplification of short to medium fragments (≤2 kb) | Viral RNA, mRNA | SARS-CoV-2 detection, gene expression analysis |

| OmniTaq2 [10] | Single D732N substitution conferring strand displacement | Moderate | Effective with structured templates due to strand displacement activity | RNA with secondary structure | Detection of highly structured viral RNAs |

| ReverHotTaq [10] | Bst polymerase fragments incorporated into Taq | High | Strong performance on short fragments, limited for long targets | Short viral amplicons | Rapid diagnostics of RNA pathogens |

| Conventional M-MLV/Taq Mixture [10] | Two-enzyme system | High (reference) | Broad fragment length range | All RNA types | Benchmark for comparison |

Table 2: Fidelity and Thermostability Comparison of Specialty DNA Polymerases

| Polymerase Type | Example Product | Relative Fidelity (Error Rate) | Thermostability | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Taq | Conventional Taq polymerase | 1x (reference) | Good (~95°C half-life >40 min) | Routine PCR, genotyping |

| High-Fidelity | Q5 DNA Polymerase [30] | 280x higher than Taq | Excellent | NGS library prep, cloning |

| Proprietary Blends | PrimeCap T7 [31] | Varies by blend | Tailored for specific workflows | Sensitive PCR tests, cloning |

Functional Advantages in Specialized Applications

Engineered DNA polymerases demonstrate significant functional advantages across specialized research and diagnostic applications:

Next-Generation Sequencing: High-fidelity polymerases like Q5 (New England Biolabs) with error rates 280-fold lower than standard Taq are essential for NGS library preparation, where accurate amplification is critical for variant detection [30]. The demand for such precision enzymes is growing at 7.34% CAGR, outpacing the broader polymerase market [30].

Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Lyophilized, thermostable polymerases enable development of ambient-temperature-stable reagents for resource-limited settings. These formulations support the expanding point-of-care testing market, particularly for infectious disease detection [30] [6].

Long-Range PCR: Engineered polymerases with enhanced processivity and robust performance across GC-rich regions facilitate amplification of lengthy genomic segments, supporting structural variation studies and complex cloning projects.

Multiplex PCR: Specialty blends like Fantom High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Genes2Me) enhance PCR sensitivity and specificity, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple targets in diagnostic panels [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DNA Polymerase Applications

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Q5 (NEB), PrimeCap T7 (Takara Bio) | NGS library prep, cloning requiring ultra-low error rates |

| RT-Competent DNA Polymerases | RevTaq (myPOLS), OmniTaq2, ReverHotTaq | Single-enzyme RT-PCR, pathogen detection |

| Standard Taq Polymerases | Conventional Taq, GoTaq (Promega) | Routine PCR, educational use, high-throughput screening |

| Specialty Formulations | Lyophilized master mixes, inhibitor-resistant blends | Point-of-care testing, field applications, forensic analysis |

| Library Preparation Kits | NEBNext UltraExpress (NEB) | Streamlined NGS workflow integration |

| Quantitative PCR Reagents | TaqMan probes, SYBR Green master mixes | Gene expression analysis, viral load quantification |

The strategic engineering of DNA polymerases through accessory domain incorporation and targeted mutagenesis has fundamentally transformed molecular biology workflows. The experimental data presented demonstrates that engineered enzymes like RevTaq, OmniTaq2, and high-fidelity variants offer tangible performance advantages over conventional polymerases for specific applications. These innovations directly address evolving research needs in precision medicine, diagnostics, and synthetic biology.

As the DNA polymerase market continues to evolve—projected to reach USD 721.42 million by 2034—the trend toward application-specific enzyme engineering appears likely to accelerate [6]. Future developments may include polymerases optimized for emerging CRISPR-based diagnostics, portable sequencing platforms, and specialized clinical assays. For researchers, maintaining awareness of these enzyme engineering advancements ensures optimal polymerase selection for specific experimental requirements, ultimately enhancing research outcomes across the life sciences.

Visual Appendix

DNA Polymerase Engineering Strategies

DNA Polymerase Engineering and Outcomes - This diagram illustrates the primary engineering strategies for DNA polymerases and their resulting functional applications, showing how specific modifications enable advanced molecular biology techniques.

RT-PCR Experimental Workflow

RT-PCR Experimental Workflow - This workflow outlines the key steps in reverse transcription PCR using engineered DNA polymerases, from template preparation through analysis, based on standardized experimental protocols.

Precision in Practice: Matching DNA Polymerases to Your Research and Diagnostic Goals

The performance of clinical diagnostic assays is fundamentally rooted in the precise selection of molecular tools, with thermostable DNA polymerases standing as a pivotal component. The fidelity, processivity, and efficiency of these enzymes directly govern the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based tests, which remain the gold standard for detecting a wide spectrum of pathogens [32]. Within infectious disease diagnostics, applications range from detecting rapidly emerging threats like SARS-CoV-2 to confirming serious neurological infections such as herpes simplex virus encephalitis (HSVE) and deploying broad infectious disease panels. This guide provides a objective comparison of thermostable DNA polymerases, underpinned by experimental data, to inform their application in clinical assay development. The performance of these enzymes is contextualized through specific clinical scenarios, including the detection of SARS-CoV-2 via RT-qPCR and RT-LAMP, the confirmation of HSVE through PCR, and the use of multiplexed panels for syndromic testing.

Performance Comparison of Thermostable DNA Polymerases

The choice of DNA polymerase profoundly influences assay outcomes, with key differentiators being error rate, amplification speed, and robustness in complex reaction setups. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of several commonly used enzymes.

Table 1: Fidelity and Performance Characteristics of DNA Polymerases

| Polymerase | Reported Error Rate (Errors/bp/duplication) | Relative Fidelity (vs. Taq) | Key Characteristics | Ideal Diagnostic Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | (1-20 \times 10^{-5}) [18] | 1x [18] | Low fidelity, standard for many qPCR assays | Routine, single-target detection where ultimate fidelity is not critical |

| AccuPrime-Taq HF | Not Available | ~9x better than Taq [18] | Blend optimized for high fidelity | |

| KOD Hot Start | Not Available | ~4-50x better than Taq [18] | High processivity, good fidelity | |

| Pfu | (1-2 \times 10^{-6}) [18] | 6-10x better than Taq [18] | High fidelity (proofreading activity) | Detection in strain surveillance or where sequence accuracy is paramount |

| Phusion Hot Start | (4.0 \times 10^{-7}) (HF Buffer) [18] | >50x better than Taq [18] | One of the highest fidelity enzymes available | |

| Pwo | Not Available | >10x better than Taq [18] | High fidelity |

A direct comparison of error rates determined by sequencing cloned PCR products reveals that Pfu, Phusion, and Pwo polymerases offer a significant improvement over standard Taq polymerase, with error rates more than an order of magnitude lower [18]. This high fidelity is achieved through 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity. The mutation spectra also differ, with high-fidelity enzymes predominantly producing transition mutations [18].

Beyond fidelity, the master mix formulation—an often-overlooked variable—is critical. A study evaluating ten different polymerases or master mixes for a well-established Listeria monocytogenes qPCR assay found that some alternatives failed to amplify the target altogether, despite a functional internal amplification control [33]. This demonstrates that a simple, direct substitution of the polymerase can destroy a well-established assay's performance, leading to a dramatic loss of analytical sensitivity of up to >10^6-fold [33]. Such findings underscore that an enzyme's performance is intrinsically linked to its specific buffer system, MgCl₂ concentration, and thermal profile.

Application in SARS-CoV-2 Detection

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for robust, scalable molecular diagnostics. RT-qPCR emerged as the gold standard, but its performance is heavily dependent on the enzymatic strategy employed.

Experimental Protocol: One-Step RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2

The following protocol, derived from an open-source initiative, outlines a validated one-step RT-qPCR using specific recombinant enzymes [34].

- RNA Extraction: Viral RNA is extracted from nasopharyngeal swab samples using a commercial kit. The purified RNA is eluted in a small volume (e.g., 100 µL) and its purity and quantity are assessed via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0) [34] [35].

- One-Step RT-qPCR Reaction: The reaction is set up in a total volume of 20-25 µL.

- Enzymes: The protocol uses a combination of Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase (M-MLV RT) and Taq DNA polymerase [34]. The M-MLV RT is a mutant version (D200N, L603W, T330P, L139P, E607K) with enhanced thermostability and processivity [34].

- Master Mix: The reaction includes a non-proprietary buffer, dNTPs, primers, and a TaqMan probe [34].

- Thermal Cycling: The typical profile involves reverse transcription at 50°C for 20 minutes, initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds and annealing/extension at 55°C for 40 seconds, with fluorescence acquisition [35].

- Detection: The TaqMan probe, cleaved by the 5'→3' exonuclease activity of Taq polymerase, generates a fluorescent signal, allowing for quantification of the target (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 N gene) [35].

Comparative Data: RT-qPCR vs. RT-LAMP

Alternative isothermal methods like Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP) offer simpler instrumentation. A 2024 comparative study of 342 clinical samples provides performance data.

Table 2: Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 Detection Methods on Clinical Samples

| Method | Sample Type | Number of Positive (%) | Number of Negative (%) | Agreement (Cohen's κ) | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-Step RT-LAMP [35] | Saliva | 92 (26.9%) | 250 (73.1%) | κ = 0.93 (P < 0.001) | High (Detection limit of 1 × 10¹ copies) | 100% |

| Nasopharynx | 94 (27.4%) | 248 (72.5%) | κ = 0.94 (P < 0.001) | |||

| One-Step RT-qPCR [35] | Saliva | 86 (25.1%) | 256 (74.8%) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) |

| Nasopharynx | 93 (27.1%) | 249 (72.8%) | (Reference) |

The study concluded that RT-LAMP is a highly reliable, rapid, and cost-effective alternative to RT-qPCR, with near-perfect agreement and 100% specificity [35]. The key enzyme in this RT-LAMP protocol is Bst DNA/RNA Polymerase 3.0, which possesses reverse transcriptase and strand-displacing DNA polymerase activity in a single enzyme, enabling isothermal amplification [35].

Figure 1: Comparative workflows for SARS-CoV-2 detection using RT-qPCR and RT-LAMP methodologies.

Application in Herpes Simplex Encephalitis (HSE) Diagnosis

Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a severe neurological condition where timely and accurate diagnosis is critical. PCR has become the method of choice for detecting viral DNA in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Experimental Protocol: HSV-Specific PCR for Encephalitis

- Sample Preparation: CSF is collected from patients with suspected HSVE. The sample does not require complex processing prior to nucleic acid extraction [36].

- DNA Extraction: Total nucleic acid is extracted from the CSF sample using a commercial kit. This DNA will serve as the PCR template.

- PCR Amplification: A standard PCR is set up. While the specific polymerase was not named in the foundational 1992 study, modern applications would typically use a high-fidelity enzyme to ensure accurate detection.

- Primers: The reaction uses primers designed to target a specific sequence within the HSV genome.

- Thermal Cycling: The sample undergoes multiple cycles of denaturation, primer annealing, and extension.

- Detection: Historically, amplicons were detected via gel electrophoresis. In contemporary diagnostics, this would be replaced by real-time PCR using fluorescent probes for a faster, more sensitive, and quantitative result.

Diagnostic Significance

A landmark 1992 study that compared PCR to isoelectric focusing (IEF) for intrathecally produced antibodies demonstrated the power of PCR. Of 14 patients with clinically diagnosed HSVE, the infection was confirmed in 12 by either PCR or IEF positivity, while two were negative by both methods, ruling out HSVE [36]. Furthermore, 17 patients with non-HSVE and 24 with other neurological diseases were all negative by both PCR and IEF, establishing the high specificity of the PCR method [36]. The study concluded that PCR is especially critical in the acute phase of the disease, enabling rapid diagnosis and treatment initiation [36].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and execution of the diagnostic protocols described rely on a core set of reagents and materials. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Molecular Diagnostics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Thermostable enzyme for DNA amplification via PCR. Lacks proofreading activity. | Core enzyme in open one-step RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 [34]. |

| Pfu DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity thermostable polymerase with 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity. | Preferred for applications requiring high sequence accuracy, like cloning for surveillance [18]. |

| Bst DNA/RNA Polymerase 3.0 | Recombinant polymerase with reverse transcriptase and strand-displacing DNA polymerase activity. | Key enzyme in one-step RT-LAMP for isothermal amplification of SARS-CoV-2 [35]. |

| M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme for synthesizing complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template. | Used in the first step of one-step RT-qPCR to convert SARS-CoV-2 RNA to cDNA [34]. |

| TaqMan Probe | Hydrolysis probe that emits fluorescence when cleaved by Taq polymerase's 5' nuclease activity. | Enables specific, real-time detection of target amplicons in RT-qPCR [35]. |

| LAMP Primers | A set of 4-6 primers targeting 6-8 regions of the genome for highly specific isothermal amplification. | Designed for the N gene of SARS-CoV-2 to enable specific detection via RT-LAMP [35]. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | A medium designed to stabilize viral specimens during transport and storage. | Used for collecting and storing nasopharyngeal swab samples [35]. |

The selection of a thermostable DNA polymerase is a critical determinant of success in clinical molecular diagnostics. Data demonstrates that enzymes like Pfu and Phusion offer superior fidelity for applications where sequence accuracy is paramount, while Taq polymerase remains a robust and effective choice for many quantitative detection assays. The performance of any polymerase, however, is inextricably linked to its optimized reaction buffer and conditions, and simple substitution without validation can be catastrophic for assay performance [33]. As demonstrated in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 and HSVE, the choice of enzymatic strategy—from traditional RT-qPCR to rapid isothermal RT-LAMP—must be aligned with the clinical and operational requirements, including speed, sensitivity, specificity, and resource availability. A deep understanding of polymerase characteristics enables researchers and clinicians to develop and deploy diagnostic assays with the highest level of performance and reliability.

In the realms of genomics and cloning, the selection of appropriate DNA polymerases is a fundamental determinant of experimental success. The accuracy with which these enzymes replicate template DNA sequences varies by an order of magnitude across available options, directly impacting the reliability of high-throughput sequencing data and the efficiency of high-fidelity gene construction [37]. Fidelity—the accuracy of nucleotide incorporation—and processivity—the average number of nucleotides added per binding event—represent two critical enzymatic properties that researchers must balance against technical requirements and constraints [38].

This guide provides an objective comparison of thermostable DNA polymerases, focusing on their performance in applications requiring high accuracy. We present quantitative experimental data to inform selection strategies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in advanced genomic and synthetic biology workflows.

DNA Polymerase Performance Metrics and Comparison

Key Properties Influencing Polymerase Selection

DNA polymerases exhibit distinct biochemical characteristics that dictate their suitability for specific applications. The following properties are particularly relevant for genomics and cloning:

- 3'→5' Exonuclease (Proofreading) Activity: Enzymes possessing this activity can excise misincorporated nucleotides, significantly enhancing fidelity. Proofreading capability can improve accuracy by 2-3 orders of magnitude [38] [39].

- Strand Displacement: This capability allows polymerases to unwind and replicate DNA sequences with secondary structures, beneficial for amplifying complex genomic regions [40].

- Resulting Ends: The type of ends generated (blunt or 3'A-overhangs) influences downstream cloning efficiency [41].

- Thermostability: Essential for withstanding repeated high-temperature denaturation cycles during PCR [39].

- Error Rate: Typically expressed as substitutions per base per duplication, this quantitative measure directly reflects polymerase accuracy [37].

Comparative Analysis of DNA Polymerases

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of commercially available DNA polymerases relevant to high-throughput sequencing and gene construction:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Polymerases for Genomics and Cloning Applications

| DNA Polymerase | 3'→5' Exo (Proofreading) | Fidelity (Relative to Taq) | Error Rate (per bp per duplication) | Strand Displacement | Resulting Ends | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq Standard | No | 1x | 1.1x10⁻⁴ to 8.9x10⁻⁵ [39] | No [41] | 3'A | Routine PCR, genotype screening |

| Q5 High-Fidelity | Yes (++++)) | 280x Taq [41] | Not specified | No | Blunt | High-fidelity PCR, NGS library prep, cloning |

| Phusion High-Fidelity | Yes (++++)) | 39-50x Taq [41] | ~2.0x10⁻⁶ (calculated) [37] | No | Blunt | High-fidelity PCR, cloning |

| OneTaq | Yes (++)) | 2x Taq [41] | Not specified | Yes | 3'A/Blunt | Routine PCR, colony PCR |

| Pfu Polymerases | Yes | >10x Taq | ~1.3x10⁻⁶ [39] | Varies | Blunt | High-fidelity cloning, sequencing, mutagenesis |

| Kapa High-Fidelity | Not specified | Not specified | ~5.8x10⁻⁷ (measured) [37] | Not specified | Not specified | High-fidelity applications |

Specialized Polymerases for Advanced Applications

Recent protein engineering efforts have produced novel polymerase variants with enhanced capabilities:

Reverse Transcriptase-Active DNA Polymerases: Engineered thermostable DNA polymerases like RevTaq, OmniTaq2, and ReverHotTaq incorporate reverse transcriptase activity, enabling single-enzyme RT-PCR. While suitable for SARS-CoV-2 detection and endogenous mRNA assays, these enzymes show limitations in long-fragment RT-PCR amplification [40].

High-Fidelity Polymerases for Gene Synthesis: Enzymes such as Q5 are instrumental in large-scale gene construction platforms. When implemented with optimized assembly protocols and enzymatic error correction, these polymerases enable synthesis of 35 kilobasepairs of DNA from complex oligonucleotide pools containing 13,000 oligonucleotides encoding ~2.5 megabases of DNA [42].

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Quantitative Fidelity Assessment

Advanced methodologies combining unique molecular identifier (UMI) tagging with high-throughput sequencing enable precise measurement of polymerase error rates. This approach discriminates errors introduced during initial PCR from those occurring in subsequent amplification and sequencing steps, providing exceptional resolution for comparing polymerase accuracy [37].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Error Rates for Various DNA Polymerases

| DNA Polymerase | Per-Cycle Error Rate (Substitutions/bp/duplication) | Dominant Substitution Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kapa High-Fidelity | 5.8x10⁻⁷ | C>T/G>A | Highest measured fidelity |

| SD-HS | 1.1x10⁻⁶ | A>G/T>C | |

| TruSeq | 1.2x10⁻⁶ | C>T/G>A | |

| Tersus-buf1 | 1.6x10⁻⁶ | C>T/G>A | |

| Taq-HS | 3.3x10⁻⁶ | A>G/T>C | |

| Encyclo | 4.2x10⁻⁶ | A>G/T>C | Lowest fidelity among high-fidelity enzymes tested |

| Phusion | ~2.0x10⁻⁶ (calculated from limited data) | Not determined | Excluded from detailed pattern analysis due to low efficiency [37] |

The experimental data reveal that error rates vary significantly across polymerases, with the most accurate enzymes (Kapa High-Fidelity) exhibiting approximately 7-fold greater accuracy than the least accurate high-fidelity option (Encyclo) under standardized testing conditions [37].

Substitution Pattern Analysis

Comprehensive error analysis reveals distinct substitution preferences across different polymerase types:

- Category 1 (C>T/G>A dominant): Includes Kapa HF, SNP-detect, Tersus, and TruSeq

- Category 2 (A>G/T>C dominant): Includes Encyclo, SD-HS, Taq-HS, and KTN [37]

These polymerase-specific "fingerprints" reflect underlying biochemical differences in nucleotide recognition and incorporation. Understanding these patterns informs polymerase selection for applications where specific substitution types might be particularly problematic.

Research Reagent Solutions for High-Fidelity Applications

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Fidelity Genomics and Cloning Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Q5, Phusion, Pfu Ultra II | Provide accurate DNA amplification with minimal errors |

| Proofreading Polymerase Mixtures | Taq/Pfu blends | Balance speed and fidelity for longer amplicons |

| Hot Start Formulations | Hot Start Taq, Q5 Hot Start | Inhibit polymerase activity at room temperature to reduce primer-dimer formation and non-specific amplification |

| Reverse Transcriptase-Active Polymerases | RevTaq, OmniTaq2, Tth | Enable cDNA synthesis and amplification in single-enzyme systems |

| Strand Displacing Polymerases | Bst DNA Polymerase, ReverHotTaq | Amplify templates with complex secondary structures |

| Library Preparation Kits | NEBNext UltraExpress | Optimized for fast, efficient NGS library construction |

| Assembly Systems | NEBridge Golden Gate Assembly | Type IIS restriction enzyme-based systems for modular DNA construction |

| Error Correction Enzymes | Uracil-DNA Glycosylase, Endonuclease VIII | Correct errors in synthesized DNA fragments |

Application-Oriented Selection Guidelines