Validating Enzyme Substrate Specificity: A Comprehensive Guide from Prediction to Experimental Confirmation

Accurately predicting and validating enzyme substrate specificity is a critical challenge in biochemistry, metabolic engineering, and drug discovery.

Validating Enzyme Substrate Specificity: A Comprehensive Guide from Prediction to Experimental Confirmation

Abstract

Accurately predicting and validating enzyme substrate specificity is a critical challenge in biochemistry, metabolic engineering, and drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of enzyme specificity, advanced computational prediction methods, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing predictions, and rigorous experimental validation techniques. By integrating insights from structural genomics, machine learning, kinetic analysis, and multi-substrate screening, we outline a systematic approach to bridge the gap between in silico predictions and reliable experimental confirmation, enabling more confident application of enzyme specificity data in biomedical and industrial contexts.

Understanding Enzyme Specificity: From Evolutionary Patterns to Structural Determinants

In enzymology, the precise definitions of specificity and selectivity are foundational to understanding enzyme function, engineering biocatalysts, and developing therapeutic interventions. Specificity often refers to an enzyme's ability to recognize and catalyze a reaction with a single substrate among many, while selectivity commonly describes the preferential action on one substrate over others present in a mixture. Quantifying these properties relies on kinetic parameters and discrimination indices derived from rigorous experimental data. Within the broader context of validating enzyme substrate specificity predictions, this guide objectively compares the performance of established experimental methods with emerging computational tools for defining enzyme specificity and selectivity. We present supporting kinetic data, detailed experimental protocols, and a curated toolkit to equip researchers with the resources for critical assessment in drug development and enzyme engineering.

Comparative Analysis of Specificity Determination Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the primary methods used to define and quantify enzyme specificity.

Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Defining Enzyme Specificity and Selectivity

| Method | Key Measurable Outputs | Typical Discrimination Indices | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-State Kinetics | ( k{cat} ), ( Km ), ( k{cat}/Km ) [1] | Specificity Constant (( k{cat}/Km )) ratio for substrates | Provides fundamental, quantitative parameters; well-understood theoretical framework [1] | Parameter reliability issues; unidentifiable parameters in complex systems [2] [1] |

| Structure-Based Machine Learning (e.g., PGCN, EZSpecificity) | Cleavage probability, Specificity score/accuracy [3] [4] | Prediction accuracy (%), AUC, F1 score [4] | High throughput; can predict for uncharacterized enzymes/substrates; incorporates structural energetics [3] [4] | "Black box" interpretation; dependency on quality and scope of training data [4] |

| Binding Affinity Studies (SPR, ITC) | Dissociation constant (( K_D )), Binding enthalpy (ΔH) [5] | ( K_D ) ratio for competing substrates | Directly measures binding energy; identifies exosite interactions [5] | May not directly correlate with catalytic efficiency; requires purified components [5] |

| 3D Template/Evolutionary Tracing (ETA) | Functional annotation, Substrate prediction [6] | Annotation accuracy down to 4th EC number [6] | High accuracy at low sequence identity; identifies key functional residues [6] | Limited to enzymes with evolutionary relatives and structural data [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Kinetic Parameter Determination

Reliable determination of specificity requires carefully controlled experiments. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies.

Steady-State Kinetics and Parameter Estimation

This protocol is used to determine the classic Michaelis-Menten parameters, ( Km ) and ( V{max} ), which are the foundation for calculating the specificity constant (( k{cat}/Km )).

- Assay Condition Design: Reactions should be conducted under physiologically relevant conditions of pH, temperature, and ionic strength to ensure kinetic parameters are meaningful [1]. The buffer system must be chosen carefully as components can activate or inhibit the enzyme [1].

- Initial Rate Measurements: Kinetic parameters are predicated on initial rate conditions, where the reaction rate is linear over time, avoiding complications from substrate depletion, product inhibition, or enzyme instability [1]. Use high-throughput assays with fixed time points or continuous monitoring to capture this initial linear phase.

- Nonlinear Least Squares Estimation: Avoid outdated graphical/linearization methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk plots) that distort error structures [2]. Instead, use nonlinear regression to fit the initial rate data directly to the Michaelis-Menten equation (( v = (V{max} \times [S]) / (Km + [S]) )) for robust parameter estimation [2] [1].

- Handling Complex Systems: For enzymes with competing substrates (e.g., CD39 where ADP is both product and substrate), use a modified Michaelis-Menten framework that accounts for competition. The rate for the ATPase reaction, for instance, can be expressed as: ( V{ATP} = \frac{v{max1} \times [ATP]}{K{m1} \times (1 + \frac{[ADP]}{K{m2}}) + [ATP]} ) where subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the ATPase and ADPase reactions, respectively [2]. To overcome parameter unidentifiability, estimate kinetic parameters for each reaction (e.g., ATPase vs. ADPase) using independent datasets where possible [2].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) for Binding Specificity

SPR measures real-time biomolecular interactions without labels, providing direct data on binding affinity and kinetics [5].

- Immobilization: The enzyme (e.g., ScpA) is immobilized on a sensor chip surface. A blank reference flow cell is essential for subtracting background signals.

- Binding Kinetics: A series of concentrations of the analyte (e.g., substrate C5a) are flowed over the chip surface. The association and dissociation phases are recorded in real-time as resonance units (RU) [5].

- Data Analysis: The resulting sensorgrams are fitted to a binding model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir) to determine the association rate constant (( k{on} )), dissociation rate constant (( k{off} )), and the equilibrium dissociation constant (( KD = k{off}/k_{on} )) [5].

- Exosite Mapping: To identify interactions beyond the active site, binding studies can be repeated with substrate fragments (e.g., the core "PN" fragment of C5a) or point mutants (e.g., arginine-to-alanine mutations) to deconvolve the contributions of different binding regions to the overall affinity [5].

Validation of Computational Predictions

Experimental validation is critical for assessing computational predictions of substrate specificity.

- Yeast Surface Display: This method is used for high-throughput screening of protease specificity. A library of potential substrate sequences is displayed on the yeast surface. Cleavage by a protease of interest removes an epitope tag, which can be quantified by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to identify cleaved versus uncleaved substrates [4].

- Enzyme Assays with Predicted Substrates: For a proposed enzyme-substrate pair, traditional enzyme assays are performed. The substrate is incubated with the enzyme, and the formation of product or depletion of substrate is measured over time using appropriate analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC, mass spectrometry) to confirm activity and determine kinetic parameters [6] [7].

- Mutagenesis of Critical Residues: Key residues identified by computational models (e.g., catalytic or specificity-determining residues from a 3D template) are mutated. A significant drop in activity or a shift in specificity upon mutation provides strong experimental evidence for the model's prediction [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Specificity Studies

| Tool / Resource | Function in Specificity Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive repository for curated enzyme kinetic data (( k{cat}), ( Km )) from literature [1] [8]. | https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/ |

| STRENDA Guidelines | Standards for Reporting Enzymology Data; ensures reliability and reproducibility of reported kinetic parameters [1]. | https://www.strenda.org/ |

| SKiD (Structure-oriented Kinetics Dataset) | A curated dataset integrating enzyme kinetic parameters with 3D structural data of enzyme-substrate complexes [8]. | https://github.com/Structural-Kinetics/SKiD |

| EZSpecificity AI Tool | A cross-attention graph neural network that predicts enzyme-substrate specificity from sequence and structural data [3] [9]. | Available via web interface [9] |

| PGCN (Protein Graph Convolutional Network) | A geometric ML model using protein structure and energetics to predict protease substrate specificity [4]. | - |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Provides energy functions for modeling protein structures and complexes, used to generate features for ML models like PGCN [4]. | https://www.rosettacommons.org/ |

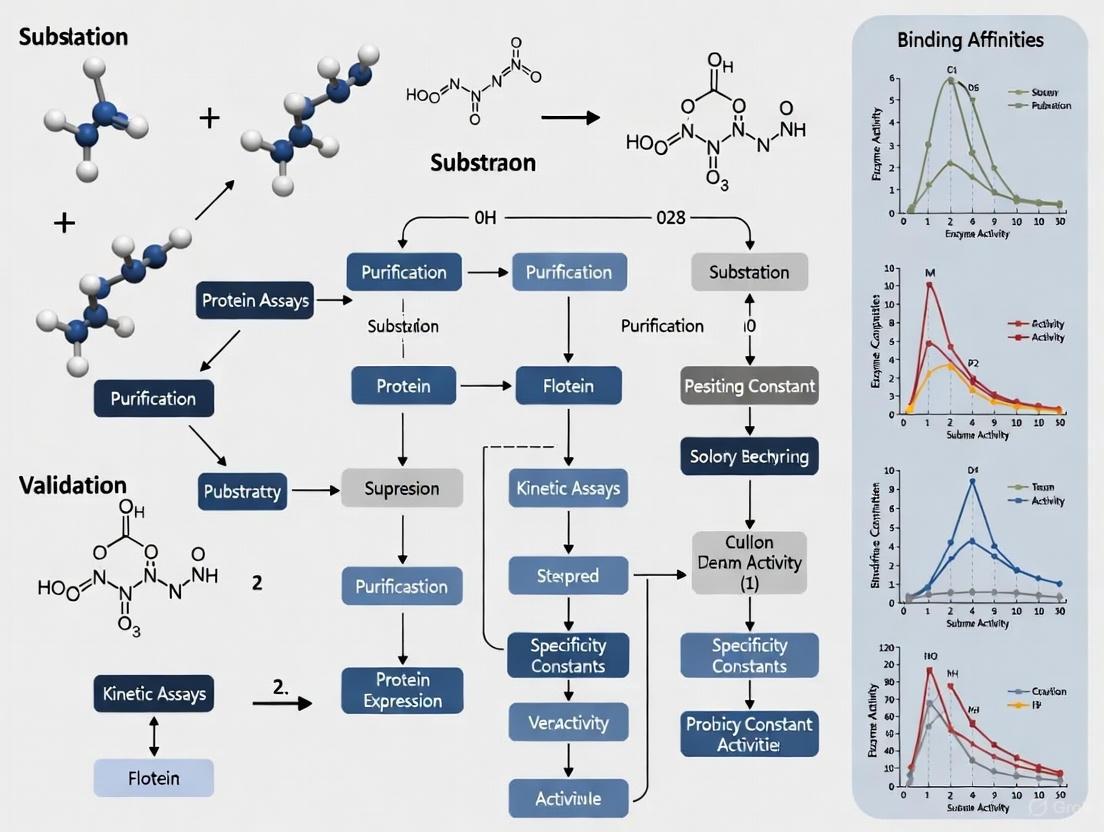

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Experimental Workflow for Specificity Validation

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for integrating computational predictions with experimental validation, a key process in modern enzyme specificity research.

Kinetic Parameter Identifiability Challenge

This diagram outlines the specific challenge of parameter unidentifiability in complex enzyme systems like CD39, and the proposed solution of using independent experiments.

The accurate definition of enzyme specificity and selectivity hinges on the reliable determination of kinetic parameters and the intelligent application of discrimination indices. As demonstrated, traditional steady-state kinetics remains the gold standard for quantification but faces challenges with parameter reliability and identifiability in complex systems. Emerging machine learning tools, such as EZSpecificity and PGCN, show remarkable promise in predicting specificity with high accuracy, offering a powerful complement to experimental methods. The future of specificity validation lies in a synergistic approach, where computational predictions guide targeted experimental designs, and high-quality kinetic data from those experiments, in turn, refines and validates the predictive models. This iterative cycle, supported by curated resources like the SKiD database and STRENDA guidelines, will accelerate the precise engineering of enzymes for therapeutics and biocatalysis.

In the fields of protein engineering and drug development, a central challenge lies in accurately identifying which amino acid residues within an enzyme are most critical to its function. These functionally critical residues determine substrate specificity, catalytic activity, and molecular recognition. For researchers aiming to redesign enzymes for industrial applications or to develop drugs that precisely target pathogenic proteins, distinguishing these key residues from the structural background is paramount. Evolutionary Tracing (ET) has emerged as a powerful computational method that addresses this challenge by extracting functional signals from evolutionary patterns [10]. This guide provides an objective comparison between ET and other computational approaches for identifying functionally critical residues, with a specific focus on validating enzyme substrate specificity predictions—a crucial consideration for both basic research and therapeutic development.

Methodological Approaches: A Comparative Framework

Evolutionary Tracing (ET)

Core Principle: Evolutionary Tracing operates on the fundamental premise that residues critical for function will exhibit variation patterns that correlate with major evolutionary divergences. The method analyzes a multiple sequence alignment of homologous proteins to rank each residue position by its relative importance [10]. The underlying hypothesis is that residues varying between widely divergent evolutionary branches are more functionally impactful than those varying only among closely related species [10].

Methodological Workflow: The basic ET algorithm assigns a rank to each residue position (i) according to the formula:

ri = 1 + Σδn

where the summation occurs over all nodes (n) in the phylogenetic tree, and δ_n equals 0 if the residue is invariant within sequences at node n, or 1 if it varies [10]. Refinements have led to a real-value ET (rvET) that incorporates Shannon entropy to measure invariance within branches, making the method more robust to alignment errors and natural variations [10]. Top-ranked ET residues (typically those in the top 30th percentile) are considered functionally important, and their spatial clustering in protein structures is quantified using a clustering z-score to identify functional sites [10].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Evolutionary Tracing

| Feature | Description | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Correlation between residue variations and evolutionary divergence | Experimental mutagenesis in multiple protein families [10] |

| Requirements | Multiple sequence alignment (20+ homologs), phylogenetic tree, protein structure | Significant results typically require 20+ sequence homologs [10] |

| Output | Ranked list of residues by evolutionary importance | Top-ranked residues cluster in 3D structure and map to functional sites [10] |

| Key Strength | Identifies both conserved and subfamily-specific functional determinants | Successfully guided function swapping between homologs [10] [11] |

Alternative Computational Approaches

Several complementary methods have been developed to identify critical residues using different principles and data sources:

Network Analysis Methods: These approaches model proteins as residue interaction networks where nodes represent amino acids and edges represent chemical interactions or spatial proximity. Centrality measurements (connectivity, betweenness, closeness centrality) identify residues critical for maintaining the interaction network [12]. Unlike ET, these methods rely solely on 3D structure without requiring multiple sequence alignments.

Coevolution Analysis (DyNoPy): This method combines residue coevolution analysis from multiple sequence alignments with molecular dynamics simulations. It detects "coevolved dynamic couplings"—residue pairs with critical dynamical interactions preserved during evolution—using graph models to identify communities of important residue groups [13].

Surface Patch Ranking (SPR): SPR identifies specificity-determining residue clusters by exploring both sequence conservation and correlated mutations. It focuses on surface patches and evaluates clusters of residues rather than individual positions for their ability to discriminate functional subtypes [14].

Machine Learning (EZSpecificity): Recent approaches like EZSpecificity use cross-attention-empowered SE(3)-equivariant graph neural networks trained on comprehensive enzyme-substrate interaction databases to predict substrate specificity from sequence and structural information [3].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Predictive Accuracy for Functional Residues

Direct comparisons between methods reveal complementary strengths. A study comparing phylogenetic approaches to network-based methods found that while both accurately detect critical residues, they tend to predict different sets of residues [12]. Specifically, network-based methods preferentially identify highly connected, internal residues critical for structural integrity, while ET identifies more surface residues involved in functional interactions [12].

A hybrid approach combining closeness centrality (a network measure) with Conseq (a phylogenetic method) demonstrated improved prediction accuracy over either method alone, highlighting the complementary nature of these approaches [12]. This suggests that evolutionary conservation and structural centrality capture different aspects of residue importance.

Table 2: Method Performance Comparison for Identifying Critical Residues

| Method | Basis of Prediction | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Trace | Evolutionary variation patterns | Excellent for functional site prediction; validated for protein engineering | Requires multiple homologs; sensitive to alignment quality [10] |

| Network Analysis | Residue interaction networks | Works with single structures; identifies structurally critical residues | May miss functionally important surface residues [12] |

| Coevolution (DyNoPy) | Coevolved dynamic couplings | Captures dynamics and allostery; identifies residue communities | Computationally intensive; requires MD simulations [13] |

| Machine Learning | Pattern recognition in known structures | High accuracy for substrate prediction; rapid once trained | Requires extensive training data; black box limitations [3] |

Validation in Enzyme Substrate Specificity Prediction

The accurate prediction of enzyme substrate specificity represents a particularly challenging validation test. The Evolutionary Trace Annotation (ETA) pipeline creates 3D templates from 5-6 top-ranked ET residues and searches for matching geometric and evolutionary patterns in annotated structures [6]. In large-scale controls, ETA identified enzyme activity down to the first three Enzyme Commission levels with 92% accuracy, maintaining nearly perfect annotation accuracy even when sequence identity between query and matches fell below 30% [6].

Notably, ETA successfully predicted the substrate specificity of a previously uncharacterized Silicibacter sp. protein as a carboxylesterase for short fatty acyl chains. Biochemical assays and directed mutations confirmed both the activity and that the ET-identified motif was essential for catalysis and substrate specificity [6]. The ET-derived 3D templates were found to be hybrid motifs containing both catalytic residues (e.g., histidine, aspartic acid) and non-catalytic residues (e.g., glycine, proline) that contribute to structural stability and dynamics [6].

In comparison, the machine learning method EZSpecificity demonstrated 91.7% accuracy in identifying single potential reactive substrates for eight halogenases with 78 substrates, significantly outperforming a state-of-the-art model which achieved only 58.3% accuracy [3].

Experimental Validation Protocols

ET-Guided Mutagenesis and Functional Assays

Experimental validation of ET predictions typically follows a structured pipeline. After ET analysis identifies top-ranked residues, site-directed mutagenesis targets these positions. Functional assays then compare wild-type and mutant proteins. Key experimental approaches include:

Activity Assays: For enzymes, these measure catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) and substrate specificity against multiple potential substrates [6] [15]. For example, after ET identified position I244 in esterase EH3 as critical, I244F mutation dramatically altered enantioselectivity (e.e. 50% to 99.99%) while maintaining a broad substrate range [15].

Binding Assays: Surface plasmon resonance (SPR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), or yeast two-hybrid systems quantify interactions with partners, substrates, or inhibitors [16].

Structural Studies: X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM reveal structural changes in mutants, particularly when residues cluster in specific regions [10].

High-Throughput Validation

Recent advances enable library-scale validation. Deep mutational scanning creates comprehensive variant libraries which can be screened for activity, stability, or binding [16]. For example, in one protein engineering study, five cycles of computational design and experimental screening (using yeast display and flow cytometry) refined antibody designs until nM binders were obtained [16]. Such quantitative sequence-performance mapping provides rich feedback for improving computational methods.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Method Implementation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools | Generate aligned homolog sequences for ET analysis | ClustalOmega, MUSCLE, MAFFT [10] |

| Evolutionary Trace Servers | Perform ET analysis automatically | Public ET server: http://mammoth.bcm.tmc.edu/ [10] |

| Protein Structures | For spatial mapping and cluster analysis | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [6] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Create targeted mutations in predicted residues | Commercial kits (e.g., Q5, QuikChange) [6] [15] |

| Activity Assay Reagents | Validate functional consequences of mutations | Substrate libraries, coupling enzymes, detection reagents [6] [15] |

Evolutionary Tracing represents the most extensively validated approach for identifying functionally critical residues, with demonstrated success in predicting functional sites and guiding protein engineering [10]. The method's particular strength lies in its ability to identify residues where evolutionary variations correlate with functional divergence, making it exceptionally valuable for predicting substrate specificity in enzymes.

When compared to alternative methods, ET shows complementary strengths with network-based approaches, with hybrid methods delivering superior performance [12]. While newer machine learning methods like EZSpecificity show impressive accuracy for substrate prediction [3], ET provides interpretable, mechanistic insights into why specific residues matter based on evolutionary principles.

For researchers pursuing enzyme engineering or drug discovery, the experimental evidence supports a strategic approach: begin with ET to identify candidate functional residues, potentially combine with network analysis for structural context, and employ machine learning for large-scale substrate predictions. As structural genomics continues to expand the universe of uncharacterized proteins, these computational methods for identifying critical residues will become increasingly essential for converting structural information into functional understanding.

The exquisite specificity of enzymes is a cornerstone of biological function, dictating the flow of biochemical pathways and cellular signaling events. This specificity originates from the precise three-dimensional arrangement of atoms within the enzyme's active site—a structural motif that physically complements and chemically stabilizes specific transition states. For researchers in enzymology and drug development, predicting and validating these structure-function relationships remains a fundamental challenge. Recent advances in computational and structural biology have produced powerful tools for dissecting active site architecture and forecasting substrate specificity. This guide provides an objective comparison of these emerging methodologies, evaluating their performance, experimental validation, and practical applications for profiling enzyme function in research and therapeutic contexts.

Quantitative Comparison of Specificity Prediction Platforms

The following tables summarize the core methodologies, performance metrics, and optimal use cases for leading specificity prediction tools, enabling direct comparison of their capabilities.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Specificity Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Methodology | Reported Accuracy | Key Experimental Validation | Throughput Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network [3] | 91.7% (single reactive substrate ID) [3] | 8 halogenases with 78 substrates [3] | High (structural database) |

| ESP | Transformer model with gradient-boosted decision trees [17] | >91% (independent test data) [17] | 18,351 enzyme-substrate pairs [17] | High (sequence-based) |

| EZSCAN | Homologous sequence analysis & conservation [18] | Validated on known SDRs* | LDH/MDH mutation experiments [18] | Medium (requires homologs) |

| COLLAPSE | Unsupervised clustering of structural microenvironments [19] | State-of-art structure search [19] | Pathogenic variant mapping [19] | Structural motif discovery |

*SDRs: Specificity-determining residues

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Data Requirements

| Tool | Input Requirements | Output Specificity | Therapeutic Application Evidence | Access Modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity | Enzyme structure & substrate data [3] | Single substrate identification [3] | Not explicitly stated | Web server (public) |

| ESP | Enzyme sequence & small molecule [17] | Enzyme-substrate pair prediction [17] | Drug development implication [17] | Web server (public) |

| EZSCAN | Enzyme sequence (homologs required) [18] | Specificity residues & mutations [18] | Drug discovery implication [18] | Web server (public) |

| COLLAPSE | Protein structure or microenvironment [19] | Local motif classification [19] | Pathogenic variant interpretation [19] | Code repository (public) |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

To ensure reproducible results when applying these tools, researchers should follow standardized experimental protocols for training, validation, and implementation.

EZSpecificity Model Training and Validation

The EZSpecificity protocol employs a comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate interactions at sequence and structural levels [3]. The experimental validation involved eight halogenases tested against 78 potential substrates, with performance benchmarked against state-of-the-art models. The key methodological steps include:

- Data Curation: Compile enzyme-substrate pairs with structural and sequence information from public databases and literature sources.

- Model Architecture Implementation: Configure the cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network to process 3D structural data while maintaining rotational and translational invariance.

- Training Protocol: Train the model using positive enzyme-substrate pairs with data augmentation techniques to account for structural variations.

- Experimental Validation: Express and purify target enzymes (e.g., halogenases) for in vitro activity assays against potential substrates identified by predictions.

- Performance Quantification: Calculate prediction accuracy as the percentage of correctly identified reactive substrates from the test pool.

ESP (Enzyme Substrate Prediction) Framework

The ESP model was trained on approximately 18,000 experimentally confirmed enzyme-substrate pairs encompassing 12,156 unique enzymes and 1,379 unique metabolites [17]. Critical to its success was the strategic generation of negative examples:

- Positive Data Collection: Extract experimentally validated enzyme-substrate pairs from UniProt and GO annotation databases with high-confidence evidence codes.

- Negative Data Augmentation: For each positive enzyme-substrate pair, sample three structurally similar molecules (similarity score 0.75-0.95) from the metabolite pool that are not known substrates, creating putative non-binding pairs [17].

- Protein Representation: Generate enzyme embeddings using a modified ESM-1b transformer model with an additional 1280-dimensional token trained to capture enzyme-specific functional information [17].

- Substrate Representation: Encode small molecules using task-specific fingerprints created with graph neural networks to capture structural and chemical features.

- Model Training: Implement gradient-boosted decision trees on concatenated enzyme and substrate representations, with cross-validation to prevent overfitting.

EZSCAN Workflow for Specificity Residue Identification

EZSCAN employs a homology-based approach to identify residues governing substrate specificity [18]:

- Sequence Alignment: Compile and align homologous enzyme sequences with known functional differences using standard tools (e.g., ClustalOmega, MUSCLE).

- Feature Extraction: Treat each residue position as an independent feature for classification between enzyme subgroups.

- Conservation Analysis: Calculate position-specific conservation scores and residue frequency distributions to identify specificity-determining positions.

- Mutational Validation: Introduce point mutations at predicted specificity residues and measure kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) against alternative substrates.

- Functional Assay: Quantify enzyme activity and specificity shifts using appropriate biochemical assays (e.g., spectrophotometric, chromatographic).

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows for the key methodologies discussed, providing researchers with clear conceptual roadmaps.

Diagram 1: Computational Prediction Workflows (ESP & EZSCAN)

Diagram 2: Experimental Validation Pipeline

Successful investigation of structural motifs and active site architecture requires specialized computational and experimental resources. The following table catalogs essential tools and databases for comprehensive specificity studies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Specificity Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | AlphaSync Database [20] | Continuously updated predicted structures | Access to current structural models for enzymes |

| Structure Search Tools | Foldseek [21] | Rapid protein structure comparison | Identify similar active site architectures |

| Specialized Analysis Frameworks | PGH-VAEs [22] | Topological analysis of active sites | Inverse design of catalytic sites |

| Microenvironment Clustering | COLLAPSE [19] | Unsupervised learning of structural motifs | Local functional site annotation |

| Variant Effect Prediction | AlphaMissense [21] | Pathogenicity of missense variants | Assess functional impact of active site mutations |

| Enzyme-Substrate Databases | UniProt [17] | Comprehensive enzyme functional annotations | Source of experimentally validated pairs |

The validation of enzyme substrate specificity predictions represents a rapidly advancing frontier where computational intelligence and experimental evidence increasingly converge. Tools like EZSpecificity and ESP demonstrate that machine learning can achieve remarkable accuracy (>91%) in predicting enzyme-substrate relationships when trained on diverse, high-quality datasets [3] [17]. The complementary strengths of structure-based (EZSpecificity) and sequence-based (ESP) approaches offer researchers multiple pathways for specificity investigation. For therapeutic applications, these platforms enable rapid prioritization of enzyme-substrate pairs for experimental validation, accelerating drug target identification and off-target profiling. As structural databases expand and algorithms refine their capacity to interpret the physical principles of molecular recognition, the integration of these computational tools with robust experimental protocols will continue to enhance our understanding of the architectural foundations of enzymatic specificity.

Enzyme promiscuity, defined as the ability of enzymes to catalyze reactions beyond their primary physiological functions, has emerged as a pivotal concept in modern enzyme engineering and functional annotation [23]. This phenomenon stands in contrast to the traditional "lock-and-key" model of enzyme specificity, where enzymes are thought to interact with a single, specific substrate. In reality, enzyme function is not that simple; the active site pocket is not static but changes conformation upon substrate interaction in a process more accurately described as an "induced fit" [24]. Some enzymes exhibit remarkable flexibility, demonstrating "catalytic promiscuity" by stabilizing different transition states or "substrate promiscuity" by accommodating multiple substrates involving similar transition states [23].

The accurate prediction of enzyme-substrate relationships represents a fundamental challenge in biochemistry with significant implications for basic research and applied biotechnology. While enzyme promiscuity can pose challenges to specificity, it also serves as an evolutionary starting point for the development of new enzymatic activities and pathways [25]. This dual nature of promiscuity—both a challenge for prediction and an opportunity for enzyme engineering—frames the current landscape of computational and experimental approaches to understanding enzyme function. This review examines the current generation of AI-driven tools for enzyme specificity prediction, provides experimental frameworks for their validation, and explores the practical implications of enzyme promiscuity for research and industrial applications.

Computational Tools for Predicting Enzyme-Specificity and Promiscuity

Performance Comparison of Prediction Tools

Table 1: Comparison of Enzyme Specificity Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Underlying Architecture | Key Features | Reported Accuracy | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network | Integrates enzyme sequence and 3D structural data; trained on comprehensive enzyme-substrate database | 91.7% accuracy on halogenase validation set [3] [24] | Performance may vary across enzyme classes not well-represented in training data |

| ESP | Not specified in available literature | Previously considered state-of-the-art | 58.3% accuracy on same halogenase validation set [3] [24] | Lower accuracy compared to newer architectures |

| SOLVE | Ensemble learning (RF, LightGBM, DT) with optimized weighted strategy | Uses only primary sequence data; interpretable via Shapley analysis; differentiates enzymes from non-enzymes [26] | High accuracy in enzyme vs. non-enzyme classification and EC number prediction [26] | Limited to sequence information only |

| ML-hybrid Approach | Combination of multiple machine learning algorithms | Integrates high-throughput peptide array data with machine learning; enzyme-specific models [27] | Correctly predicted 37-43% of proposed PTM sites for SET8 and SIRT1-7 [27] | Requires experimental data generation for each enzyme class |

Technical Approaches and Methodological Advances

The next generation of enzyme specificity prediction tools leverages diverse computational strategies and data sources. EZSpecificity utilizes a novel cross-attention-empowered SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network architecture trained on a comprehensive, tailor-made database of enzyme-substrate interactions at sequence and structural levels [3]. This approach specifically addresses the challenge that while an enzyme's specificity originates from its three-dimensional active site structure and complicated transition state, millions of known enzymes still lack reliable substrate specificity information [3].

In contrast, SOLVE employs an ensemble learning framework that integrates random forest (RF), light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), and decision tree (DT) models with an optimized weighted strategy [26]. This tool operates solely on features extracted directly from raw primary sequences, capturing the full spectrum of sequence variations through numerical tokenization of 6-mer subsequences, which was found to optimally capture local sequence patterns balancing computational efficiency and predictive performance [26].

The ML-hybrid approach represents a different paradigm, combining machine learning with high-throughput experimental data generation [27]. This method begins with experimental generation of enzyme-specific training data using peptide arrays, then subjects them to in vitro enzymatic activity assays to characterize enzymatic PTM activity, creating unique ML models specific to each PTM-inducing enzyme [27].

Experimental Validation of Prediction Accuracy

Benchmarking Studies and Experimental Protocols

Table 2: Experimental Validation of Prediction Tools

| Validation Method | Application Example | Key Outcomes | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halogenase Screening | 8 halogenase enzymes tested against 78 substrates [3] [24] | EZSpecificity: 91.7% accuracy for top pairing predictions vs. ESP: 58.3% accuracy [3] [24] | Direct functional assessment of enzyme-substrate pairs | Limited to enzymes with available structural data |

| Docking Simulations | Molecular docking for different classes of enzymes [24] | Created large database of enzyme conformation around substrates; provided missing data for accurate predictor [24] | Provides atomic-level interaction data; complements experimental data | Computationally intensive; may not capture full dynamic behavior |

| In Vitro Peptide Arrays | SET8 methyltransferase and SIRT deacetylases [27] | ML-hybrid correctly predicted 37-43% of proposed PTM sites [27] | High-throughput; generates enzyme-specific training data | May not capture full protein context |

| Metabolic Pathway Analysis | Isoleucine biosynthesis in E. coli [25] | Identified recursive pathway arising from AHASII promiscuity [25] | Reveals physiological relevance of promiscuity | Complex experimental setup requiring specialized strains |

Detailed Experimental Workflows

Halogenase Experimental Validation Protocol:

- Enzyme Selection: Eight halogenase enzymes, a class not well characterized but increasingly used to make bioactive molecules, were selected for validation [24].

- Substrate Library: A diverse set of 78 potential substrates was compiled to test enzyme specificity [3].

- Experimental Setup: Enzyme-substrate reactions were conducted under optimized conditions for halogenase activity.

- Product Analysis: Reaction products were analyzed using appropriate analytical methods (likely HPLC or MS-based techniques) to determine successful enzyme-substrate pairing.

- Data Analysis: Experimental results were compared with computational predictions to calculate accuracy metrics [3] [24].

Docking Simulation Methodology:

- Structure Preparation: Enzyme structures were prepared through homology modeling or obtained from protein databases.

- Molecular Docking: Extensive docking studies for different classes of enzymes were performed using specialized software (e.g., AutoDock).

- Conformational Sampling: Multiple docking calculations (millions in total) provided data on how enzymes of various classes conform around different types of substrates [24].

- Database Construction: The results were compiled into a large database containing information about enzyme sequence, structure, and conformational behavior around substrates [24].

Biological Implications of Enzyme Promiscuity

Mechanisms and Evolutionary Significance

Enzyme promiscuity manifests through multiple mechanistic frameworks. The mechanisms underlying catalytic promiscuity primarily involve three key steps: (1) enzyme binding to the substrate forming an enzyme-substrate complex, (2) catalytic process lowering activation energy by stabilizing high-energy transition states, and (3) release of the modified substrate and regeneration of the enzyme [23]. This flexibility enables enzymes to catalyze alternative reactions or process non-native substrates.

From an evolutionary perspective, enzyme promiscuity serves as a starting point for the evolution of new enzymatic activities and pathways [25]. Natural enzyme evolution occurs through alterations in the electrostatic properties and geometric complementarity of active sites. Divergent evolution allows the optimization process to gradually unfold within the sequence space, enabling closely related enzymes to act on different substrates [23]. Enzyme superfamilies represent quintessential examples where enzymes share similar mechanisms and structural features while often exhibiting promiscuous activities corresponding to the functional diversity present in the superfamily [23].

The biological implications of enzyme promiscuity extend to metabolic network resilience and adaptability. Promiscuity increases the complexity of metabolism but provides significant benefits in terms of network stability and resilience [25]. This is particularly valuable for organisms needing to adapt to changing environmental conditions or nutrient availability.

Case Studies in Natural Systems

Isoleucine Biosynthesis in E. coli: A compelling example of natural enzyme promiscuity was recently discovered in E. coli isoleucine biosynthesis [25]. Researchers identified a recursive pathway based on the promiscuous activity of the native enzyme acetohydroxyacid synthase II (AHASII). This enzyme, which normally catalyzes a step downstream in isoleucine biosynthesis, was found to also catalyze the previously unreported condensation of glyoxylate with pyruvate to generate the isoleucine precursor 2-ketobutyrate in vivo [25]. This discovery represents the tenth known pathway for isoleucine biosynthesis in nature and demonstrates how enzyme promiscuity can create alternative metabolic routes using ubiquitous metabolites.

Lanthipeptide Biosynthesis: In specialized metabolism, lanthipeptide enzymes exhibit remarkable substrate promiscuity, enabling the installation of lanthionine rings on precursor peptides and facilitating further modifications to enhance biological properties [28]. The inherent flexibility of these enzymes—an important characteristic of this class of proteins—can be utilized to create peptides with improved bioactive and physicochemical properties [28]. This promiscuity has been harnessed to produce lanthipeptide libraries for drug discovery and to modify medically important peptides such as angiotensin and erythropoietin to improve their stability [28].

Practical Applications and Industrial Relevance

Biocatalysis and Enzyme Engineering

Enzyme promiscuity has emerged as a pivotal asset in biocatalysis and enzyme engineering. Through targeted strategies such as (semi-)rational design, directed evolution, and de novo design, enzyme promiscuity has been harnessed to broaden substrate scopes, enhance catalytic efficiencies, and adapt enzymes to diverse reaction conditions [23]. These modifications often involve subtle alterations to the active site, which impact catalytic mechanisms and open new pathways for the synthesis and degradation of complex organic compounds [23].

The application of promiscuous enzymes spans multiple industries:

- Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: Halogenases, the subject of EZSpecificity validation, are increasingly used to make bioactive molecules [24]. Their promiscuity enables diversification of chemical structures for drug discovery and development.

- Food Industry: Lanthipeptides like nisin have been widely used as food preservatives for over fifty years due to strong activity against food pathogens [28]. Enzyme promiscuity facilitates engineering of improved variants.

- Bioremediation: Promiscuous hydrolases demonstrate exceptional activity in carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom bond formation reactions, oxidation processes, and novel hydrolytic transformations applicable to environmental cleanup [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Studying Enzyme Promiscuity

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Arrays | High-throughput screening of enzyme-substrate interactions; training data for ML models [27] | Identifying PTM sites for methyltransferases and deacetylases [27] | May lack full protein structural context |

| Activity-Based Probes | Detection and profiling of enzyme activities in complex mixtures | Studying hydrolase promiscuity [23] | Requires careful design to maintain specificity |

| Specialized Expression Systems | Production of enzyme variants for functional characterization | Heterologous expression of lanthipeptide enzymes in E. coli and Lactococcus [28] | Optimization needed for different enzyme classes |

| Biosensor Strains | In vivo detection of metabolic pathway activity and enzyme function | E. coli isoleucine auxotroph for studying underground metabolism [25] | Enables growth-based selection for enzyme activity |

| Isotopic Labels | Tracing metabolic fluxes through promiscuous pathways | Elucidating recursive isoleucine biosynthesis [25] | Provides direct evidence of pathway activity |

The field of enzyme specificity prediction has entered a transformative phase with the advent of sophisticated AI tools that dramatically outperform traditional methods. The integration of structural information, as demonstrated by EZSpecificity, with expanded training datasets has enabled prediction accuracies exceeding 90% in validated cases [3] [24]. Nevertheless, significant challenges remain in achieving comprehensive prediction capabilities across the entire spectrum of enzyme classes, particularly for those with limited structural and functional annotation.

The dual nature of enzyme promiscuity—as both a confounding factor for specificity prediction and a valuable resource for enzyme engineering—underscores the complexity of enzyme function. As noted in recent reviews, striking a balance between maintaining native activity and enhancing promiscuous functions remains a significant challenge in enzyme engineering [23]. However, advances in structural biology and computational modeling offer promising strategies to overcome these obstacles.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) expansion of training datasets to encompass more diverse enzyme classes and reaction types, (2) integration of dynamic conformational information into predictive models, (3) development of multi-scale approaches that combine sequence, structure, and metabolic context, and (4) improved interpretation of model predictions to guide experimental validation. As these computational tools continue to evolve alongside high-throughput experimental methods, they will dramatically accelerate our ability to harness the full potential of enzymes in biotechnology, medicine, and industrial applications.

The biological implications of enzyme promiscuity extend far beyond practical applications, providing fundamental insights into evolutionary processes and metabolic adaptability. The recursive isoleucine biosynthesis pathway discovered in E. coli illustrates how enzyme promiscuity can create unexpected metabolic connectivity [25]. As research in this field progresses, we can anticipate discovering more examples of nature's ingenious repurposing of existing enzymes, inspiring new approaches in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

Computational Prediction Methods: Machine Learning and Structure-Based Approaches

A fundamental challenge in modern biochemistry and drug discovery is the functional characterization of proteins whose structures have been solved but whose biological roles remain unknown. This is particularly true for structural genomics (SG) initiatives, which often yield protein structures that cannot be assigned function based on sequence homology alone [29] [30]. Traditional homology-based methods, such as BLAST and PSI-BLAST, become increasingly error-prone as evolutionary distances grow, with reliability dropping significantly below 40-50% sequence identity [29] [30]. This creates an annotation gap where a vast portion of the structural proteome remains classified as "hypothetical" or "unknown function." Within this context, accurately predicting enzyme substrate specificity represents a particularly complex problem, as it requires identifying the precise molecular interactions that dictate binding and catalysis. Evolutionary Trace Annotation (ETA) has emerged as a powerful alternative that bypasses the limitations of global sequence comparison by focusing instead on local structural motifs composed of evolutionarily critical residues, enabling reliable function prediction even at low sequence identities where traditional methods fail [29] [31] [30].

Methodological Foundation: How ETA Works

Core Principles of Evolutionary Trace

The Evolutionary Trace (ET) method operates on the fundamental premise that residues critical for protein function exhibit variation patterns that correlate with major evolutionary divergences [10]. By analyzing a multiple sequence alignment in the context of a phylogenetic tree, ET ranks each residue by its evolutionary importance, with top-ranked residues typically clustering in three-dimensional space to form functional sites [32] [10]. These clusters have been extensively validated both computationally and experimentally, showing remarkable overlap with known functional sites and proving effective in guiding mutations that selectively alter or transfer protein function [29] [10].

The ETA Pipeline: From Evolution to Annotation

The ETA pipeline transforms evolutionary principles into concrete function predictions through a multi-stage process:

- Residue Ranking and Cluster Identification: ET analysis is performed on the query protein, ranking all residues by evolutionary importance. The method then identifies the first cluster of 10 or more top-ranked residues on the protein surface [29] [30].

- 3D Template Construction: From this cluster, ETA selects the six best-ranked residues to form a 3D template. The template comprises the Cα atom coordinates of these positions, with each residue labeled by its allowed side chain types based on frequent variations observed in homologs [29] [31].

- Geometric Search and Matching: The template is searched against a database of annotated structures using the PDM algorithm to identify matches with near-identical inter-residue distances [29].

- Specificity Filtering: Matches are rigorously filtered using three specificity enhancements:

- Evolutionary Importance Similarity: The matched residues in the target protein must themselves be evolutionarily important [29] [32].

- Match Reciprocity: A template from the matched protein must reciprocally match back to the original query protein [29] [31].

- Function Plurality: The function assigned must receive support from a plurality of matches [29] [30].

ETA Workflow: From Structure to Function Prediction

Performance Comparison: ETA Versus Alternative Methods

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Extensive benchmarking studies have quantified ETA's performance across diverse protein sets. The tables below summarize key performance metrics compared to other function prediction approaches.

Table 1: Overall Performance of ETA in Enzyme Function Prediction

| Performance Metric | High-Specificity Mode | High-Sensitivity Mode | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | 92% (3-digit EC) [31] | 82% (3-digit EC) [31] | Enzyme controls (n=1218) |

| Coverage | 43% [31] | 77% [31] | Enzyme controls (n=1218) |

| All-Depth GO PPV | 84% [29] [30] | 75% [29] [30] | SG proteins (n=2384) |

| GO Depth 3 PPV | 94% [29] [30] | 86% [29] [30] | SG proteins (n=2384) |

| Correct & Complete Predictions | 76% [29] [30] | 68% [29] [30] | SG proteins (n=2384) |

Table 2: Comparison with Alternative Function Prediction Methods

| Method | Basis of Prediction | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ETA | Evolutionary important residues + 3D templates [29] [30] | High specificity (PPV up to 94%); Works at low sequence identity; No prior mechanistic knowledge needed | Moderate coverage (53% in high-specificity mode) |

| ProFunc Enzyme Active Site | Experimentally known functional sites from CSA [29] [30] | Based on experimentally validated sites | Limited by available experimental data; cannot predict novel mechanisms |

| Homology-Based Transfer | Global sequence similarity [29] [30] | Fast; comprehensive coverage | Error-prone below 40-50% sequence identity; error propagation |

| ESP (Enzyme Substrate Prediction) | Machine learning on enzyme-substrate pairs [17] | High accuracy (91%); generalizable model | Requires substantial training data; limited to ~1400 substrate types in training |

Application to Non-Enzymes and Metal Ion Binding Proteins

A significant advantage of ETA is its generalizability beyond enzymatic functions. When applied to unannotated structural genomics proteins, ETA generated 529 high-quality predictions with an expected GO depth 3 PPV of 94%, including 280 predicted non-enzymes and 21 metal ion-binding proteins [29] [30]. An additional 931 predictions were made with a lower but still substantial expected accuracy (71% depth 3 PPV), demonstrating the method's versatility across different functional classes [30].

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

Protocol for ETA Validation

Experimental validation of ETA predictions follows a systematic approach:

- Template Construction and Matching: As described in Section 2.2, using the ETA server (http://mammoth.bcm.tmc.edu/eta) with default parameters [31].

- Function Prediction: The highest-ranked function based on match plurality and reciprocity is selected.

- In Vitro Biochemical Assays: The predicted enzymatic activity is tested using purified protein and relevant substrates under optimized conditions.

- Mutagenesis of Template Residues: Key residues identified in the ETA template are mutated to alanine, and the effect on function is measured to confirm their functional importance [29].

This validation protocol was successfully applied to a protein from Staphylococcus aureus, confirming ETA's prediction of carboxylesterase activity through biochemical assays and site-directed mutagenesis [33].

Case Study: Serine Protease Template Analysis

A seminal study compared ETA templates with traditional catalytic residue templates in serine proteases [32]. A template built from evolutionarily important but non-catalytic neighboring residues distinguished between proteases and non-proteases nearly as effectively as the classic Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad template. By contrast, a template built from poorly ranked neighboring residues failed to distinguish between these groups, demonstrating that evolutionary importance, not just spatial proximity to the active site, drives ETA's predictive power [32].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ETA Implementation

| Resource | Type | Function in ETA | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| ETA Server | Web application | Automated template creation, matching, and function prediction | http://mammoth.bcm.tmc.edu/eta [29] [31] |

| PDBSELECT90 | Structure database | Non-redundant protein structure database for template matching | PDB-derived; updated periodically [31] |

| Evolutionary Trace Wizard | Analysis tool | Generation of custom ET residue rankings | Available through ET suite [31] |

| PyMOL | Visualization | Interactive template visualization and manipulation | Commercial software [31] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) Classifier | Computational filter | Discriminates functionally relevant from spurious matches | Integrated in ETA pipeline [29] [32] |

| Catalytic Site Atlas (CSA) | Database | Source of experimentally validated functional sites for comparison | Public database [29] [30] |

Integration with Network Diffusion for Enhanced Accuracy

A significant enhancement to ETA's predictive power comes from integrating it with global network diffusion approaches. In this methodology, the entire structural proteome is conceptualized as a network where nodes represent proteins and edges represent ETA similarities [33]. Known functions then compete and diffuse across this network, with each protein ultimately assigned a likelihood z-score for every function. This approach has demonstrated remarkable accuracy, recovering enzyme activity annotations with 99% and 97% accuracy at half-coverage for the third and fourth Enzyme Commission levels, respectively – representing 4-5 fold lower false positive rates compared to nearest-neighbor or sequence-based annotations [33]. The network diffusion approach substantially improves both the coverage and resolution of ETA predictions.

Network Diffusion Enhances ETA Predictions

Evolutionary Trace Annotation represents a powerful paradigm shift in protein function prediction, moving beyond global sequence similarity to focus on local structural motifs of evolutionarily critical residues. The method's ability to maintain high specificity (PPV up to 94%) even at low sequence identities makes it particularly valuable for annotating structural genomics outputs and predicting enzyme functions where traditional homology-based methods fail [29] [30]. While coverage remains moderate in high-specificity mode, the integration of network diffusion approaches and the method's applicability to both enzymes and non-enzymes significantly expands its utility [33]. For researchers focused on enzyme substrate specificity validation, ETA provides an orthogonal validation approach that complements both experimental characterization and sequence-based predictions, leveraging evolutionary constraints to illuminate functional determinants that would otherwise remain obscure in the rapidly expanding structural proteome.

The accurate prediction of enzyme-substrate specificity is a cornerstone of modern biochemistry, with profound implications for understanding cellular mechanisms, drug discovery, and biocatalyst development [34]. Within this field, Active Site Classification (ASC) represents a methodological approach that integrates structural and sequential protein information with Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithms to delineate enzyme function and substrate preferences. This guide objectively compares the performance of ASC-inspired methodologies against other machine learning frameworks currently advancing enzyme specificity prediction.

The validation of enzyme substrate specificity predictions remains challenging due to the complex interplay between enzyme active site architecture, substrate accessibility, and dynamic reaction conditions [35]. While sequence-based predictions have historically dominated computational approaches, the integration of structural information has emerged as a critical enhancement for improving predictive accuracy [36] [37]. This comparison examines how SVM-based classification performs against increasingly popular geometric graph learning and transformer-based models across multiple enzyme families and experimental validation paradigms.

Performance Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the performance metrics of various computational approaches for predicting enzyme-substrate specificity and related functional attributes:

Table 1: Comparative performance of computational methods for enzyme function prediction

| Method | Core Approach | Application Scope | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-hybrid Ensemble | Peptide arrays + ML | PTM-inducing enzymes (methyltransferases, deacetylases) | 37-43% validation rate of predicted PTM sites | [34] [27] |

| EZSpecificity | SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network | General enzyme-substrate specificity | 91.7% accuracy identifying single reactive substrate | [3] |

| GraphEC | Geometric graph learning on ESMFold structures | EC number prediction, active site detection | AUC: 0.9583 (active sites); Superior EC number prediction | [37] |

| Three-Module ML Framework | Modular prediction of enzyme parameters | β-glucosidase kinetics (kcat/Km) | R²: ~0.38 (kcat/Km across temperatures) | [38] |

| DeepMolecules (ProSmith_ESP) | Multimodal transformer + gradient-boosted trees | General enzyme-substrate pairs | ROC-AUC: 97.2; Accuracy: 94.2% | [39] |

| GT-B Substrate Specificity Models | Multi-label SVM & other classifiers | Glycosyltransferase-B enzymes | "Good predictive accuracies" (specific metrics not provided) | [35] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SVM-Based Approaches for Active Site Classification

SVM classifiers employed for enzyme substrate specificity prediction typically follow a standardized experimental protocol. For glycosyltransferase-B (GT-B) enzymes, researchers have implemented multi-label machine learning models including Support Vector Classifier (SVC) trained on curated sequence and structural data [35]. The methodology involves:

Feature Extraction: Compiling sequence-based features (amino acid composition, physicochemical properties, position-specific scoring matrices) and structural features (active site residue coordinates, pocket volume, surface characteristics) from experimentally determined structures or homology models.

Feature Selection: Applying dimensionality reduction techniques to identify the most discriminative features for classifying substrate specificity across GT-B enzyme subfamilies.

Model Training: Implementing SVC with various kernel functions (linear, polynomial, radial basis function) to establish optimal decision boundaries in high-dimensional feature space that separate enzymes with different substrate preferences.

Cross-validation: Employing k-fold cross-validation to assess model generalizability and mitigate overfitting, particularly important given the limited annotated datasets for specific enzyme families.

Despite achieving competitive predictive accuracies, these SVM-based approaches face challenges in drawing fully interpretable relationships between sequence, structure, and substrate-determining motifs [35]. The "black box" nature of the decision boundaries, especially with complex kernels, can obscure biologically meaningful insights into the structural determinants of specificity.

Comparative Methodological Frameworks

ML-hybrid Ensemble Method: This approach combines high-throughput in vitro peptide array experiments with machine learning model generation [34] [27]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Synthesis of permutation arrays representing potential modification sites (±4 amino acids around central lysine)

- Exposure to active enzyme constructs (e.g., SET8193-352)

- Quantification of methylation activity via relative densitometry

- Training of ensemble models on the resulting activity data

- Validation through mass spectrometry analysis of predicted substrates

Geometric Graph Learning (GraphEC): This method leverages predicted protein structures for active site identification and EC number prediction [37]. The protocol includes:

- Protein structure prediction using ESMFold

- Construction of protein graphs with geometric features

- Enhancement of features with sequence embeddings from ProtTrans

- Implementation of graph neural networks for active site prediction

- Label diffusion algorithm incorporating homology information

EZSpecificity Framework: This approach utilizes SE(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for substrate specificity prediction [3]. The methodology employs:

- Comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate interactions at sequence and structural levels

- Cross-attention mechanisms between enzyme and substrate representations

- Geometric processing of three-dimensional active site architecture

- Experimental validation with halogenases and diverse substrates

Visualization of Method Workflows

ASC-Inspired SVM Classification Workflow

Comparative Multi-Method Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for enzyme specificity studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide Arrays | High-throughput screening of modification sites | Permutation arrays with ±4 AA variations around central lysine [34] |

| Active Enzyme Constructs | Catalytic domain expression for in vitro assays | SET8193-352 for methylation studies [34] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Validation of predicted PTM sites | Dynamic methylation status confirmation [34] [27] |

| ESMFold | Rapid protein structure prediction | Alternative to AlphaFold2 with 60x faster inference [37] |

| DeepMolecules Web Server | Comprehensive substrate and kinetics prediction | ESP (enzyme-substrate pairs), SPOT (transporter substrates) [39] |

| Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees | Predictive modeling from protein-small molecule representations | TurNuP (kcat prediction), KM prediction models [39] |

| Structural Alignment Tools | Domain decomposition and pocket detection | AlphaFold2-predicted structures for function prediction [36] |

Discussion

The comparative analysis reveals distinctive performance patterns across methodological frameworks. SVM-based approaches for Active Site Classification demonstrate particular utility in scenarios with well-defined feature sets and moderate dataset sizes, as evidenced in glycosyltransferase-B studies [35]. However, their performance appears constrained by dependence on manual feature engineering and limited capacity to inherently model three-dimensional structural relationships.

Geometric graph learning methods like GraphEC achieve superior performance in active site prediction (AUC: 0.9583) and EC number annotation by directly processing three-dimensional structural information [37]. Similarly, EZSpecificity demonstrates remarkable accuracy (91.7%) in identifying reactive substrates, leveraging SE(3)-equivariant networks to model enzyme-active site geometry [3]. These approaches automatically learn relevant features from structural data, potentially circumventing limitations of manual feature selection in SVM frameworks.

The ML-hybrid paradigm exemplifies the value of integrating experimental data generation with computational prediction [34] [27]. By training models on high-throughput peptide array results rather than potentially biased database annotations, this approach achieved 37-43% experimental validation rates for predicted PTM sites—a significant advancement over conventional in vitro methods.

For kinetic parameter prediction, specialized modular frameworks like the three-module ML system for β-glucosidase kcat/Km prediction address the complex interplay between sequence, temperature, and catalytic efficiency [38]. The achieved R² of ~0.38 across temperatures and sequences demonstrates the challenge of predicting quantitative kinetic parameters compared to categorical substrate specificity classifications.

The validation of enzyme substrate specificity predictions requires methodological approaches tailored to specific experimental constraints and information availability. ASC methodologies integrating structural and sequence information with SVM provide interpretable classification boundaries and perform effectively with limited training data. However, geometric graph learning and hybrid experimental-computational frameworks currently achieve superior predictive accuracy for complex specificity determination tasks.

Future methodological development should focus on integrating the strengths of these approaches: the interpretability of SVM-based classification, the structural sensitivity of geometric learning, and the validation rigor of hybrid experimental-computational paradigms. Such integrated frameworks would advance both fundamental understanding of enzyme function and practical applications in metabolic engineering and drug discovery.

Enzymes are the molecular machines of life, and their function is governed by substrate specificity—their ability to recognize and selectively act on particular target molecules. This specificity originates from the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme's active site and the complicated transition state of the reaction [3]. For researchers in biology, medicine, and drug development, accurately predicting which substrates an enzyme will act upon represents a fundamental challenge with significant implications for understanding biological systems, designing therapeutic interventions, and developing novel biocatalysts.

The traditional "lock and key" analogy for enzyme-substrate interaction has proven insufficient, as enzyme function is not that simple. As Professor Huimin Zhao explains, "The pocket is not static. The enzyme actually changes conformation when it interacts with the substrate. It's more of an induced fit. And some enzymes are promiscuous and can catalyze different types of reactions. That makes it very hard to predict" [24]. This complexity has driven the development of increasingly sophisticated computational approaches, culminating in the application of graph neural networks (GNNs) and deep learning architectures that are transforming the field of enzyme specificity prediction.

Comparative Analysis of Next-Generation Predictors

The landscape of enzyme substrate specificity prediction has evolved rapidly from traditional docking simulations to specialized deep learning models. Among these, EZSpecificity represents a significant advancement, but other approaches like OmniESI offer complementary capabilities. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these next-generation predictors based on their architectures, capabilities, and performance characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Enzyme Specificity Prediction Models

| Feature | EZSpecificity | OmniESI | Traditional ML Models | Structure-Based Docking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Cross-attention empowered SE(3)-equivariant GNN [3] | Two-stage progressive conditional deep learning [40] | Random forest, XGBoost, classical ML [41] | Molecular docking simulations (e.g., AutoDock) [3] |

| Primary Input Data | Enzyme sequence & structure, substrate information [3] | Enzyme sequence, substrate 2D molecular graph [40] | Tabular feature data, sequence descriptors [41] | 3D protein structures, ligand conformations [3] |

| Key Innovation | SE(3)-equivariance for structural invariance [3] | Progressive feature modulation guided by catalytic priors [40] | Feature engineering & ensemble learning [41] | Physical simulation of molecular fitting |

| Typical Applications | Substrate identification, enzyme function prediction [3] [24] | Kinetic parameter prediction, mutational effects, active site annotation [40] | Early-stage screening, classification tasks [41] | Binding affinity estimation, structure-based design |

| Experimental Validation | 91.7% accuracy on halogenase enzymes (78 substrates) [3] | Superior performance across 7 benchmarks for kinetic parameters & pairing [40] | Varies by implementation & dataset quality [27] | Correlation with experimental binding measurements |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

Rigorous experimental validation is essential for establishing the predictive power of computational models. In head-to-head comparisons with the previous state-of-the-art model (ESP), EZSpecificity demonstrated a remarkable performance advantage. When experimentally validated with eight halogenase enzymes and 78 substrates, EZSpecificity achieved 91.7% accuracy in identifying the single potential reactive substrate, significantly outperforming ESP at 58.3% accuracy [3] [24]. This validation framework employed a comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate interactions at both sequence and structural levels, with the model trained on extensive docking studies that provided atomic-level interaction data between enzymes and substrates [24].

OmniESI has demonstrated its capabilities across a broader range of tasks through a unified framework. It has shown superior performance in predicting enzyme kinetic parameters (kcat, Km, Ki), enzyme-substrate pairing, mutational effects, and active site annotation [40]. The model was evaluated under both in-distribution and out-of-distribution settings, demonstrating robust generalization capabilities, particularly in scenarios with decreasing enzyme sequence identity to training sequences.

Methodological Deep Dive: Experimental Protocols

EZSpecificity Architecture and Training Methodology

EZSpecificity employs a sophisticated cross-attention-empowered SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network architecture, specifically designed to handle the geometric properties of enzyme-substrate interactions [3]. The key innovation lies in its SE(3)-equivariance, which ensures that predictions remain consistent regardless of rotational or translational changes to the input structures—a crucial property for analyzing molecular interactions where orientation matters but absolute position in space does not.

The training protocol for EZSpecificity involved several meticulous stages. Researchers first assembled a comprehensive, tailor-made database of enzyme-substrate interactions at sequence and structural levels. To address the scarcity of experimental data, the team performed extensive docking studies for different classes of enzymes, running millions of docking calculations to create a large database containing information about enzyme sequences, structures, and conformational behaviors around different substrate types [24]. This approach provided the atomic-level interaction data needed to train a highly accurate predictor.

OmniESI's Progressive Conditioning Framework

OmniESI introduces a fundamentally different approach through its two-stage progressive conditional deep learning framework. The model decomposes enzyme-substrate interaction modeling into two sequential phases: first, a bidirectional conditional feature modulation where enzyme and substrate serve as reciprocal conditional information, emphasizing enzymatic reaction specificity; followed by a catalysis-aware conditional feature modulation that uses the enzyme-substrate interaction itself as conditional information to highlight crucial molecular interactions [40].

The encoding process utilizes ESM-2 (650M) with frozen parameters for enzyme sequences and a graph convolutional network trained from scratch for substrate 2D graphs. The conditional networks incorporate poly focal perception blocks with large kernel depthwise separable convolutions to extract fine-grained contextual representations across diverse receptive fields [40]. This architectural choice enables the model to internalize fundamental patterns of catalytic efficiency while maintaining strong generalization across different enzyme classes and prediction tasks.

Successful implementation and application of these advanced prediction models require familiarity with a suite of computational resources and biological databases. The table below outlines key research reagent solutions that support work in this domain.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Specificity Prediction

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Specificity Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | Database | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information [3] | Provides reference sequences and functional annotations for training and validation |

| Rhea | Database | Expert-curated biochemical reactions [42] | Ground truth data for enzyme-substrate reaction relationships |

| BRENDA | Database | Enzyme functional data including kinetics and specificity [42] | Reference data for model training and performance benchmarking |

| AutoDock-GPU | Software | Accelerated molecular docking simulations [3] | Generation of structural interaction data for training models like EZSpecificity |

| ESM-2 | AI Model | Protein language model (650M parameters) [40] | Enzyme sequence encoding in frameworks like OmniESI |

| Graph Convolutional Networks | Algorithm | Deep learning on graph-structured data [40] | Substrate molecular graph encoding and interaction modeling |

The advent of GNN-based approaches like EZSpecificity and OmniESI represents a paradigm shift in enzyme substrate specificity prediction. By moving beyond traditional machine learning and molecular docking methods, these models capture the complex, dynamic nature of enzyme-substrate interactions with unprecedented accuracy. EZSpecificity's cross-attention mechanism and SE(3)-equivariant architecture provide exceptional performance in identifying reactive substrates, while OmniESI's progressive conditioning framework offers versatile multi-task capabilities across kinetic prediction, mutational effects, and active site annotation.

The experimental validation of these models—with EZSpecificity achieving 91.7% accuracy on halogenase enzymes and OmniESI demonstrating superior performance across seven benchmarks—establishes a new standard for computational enzymology. As these tools become more accessible to researchers, they promise to accelerate discovery in fundamental biology, drug development, and enzyme engineering, ultimately bridging the gap between sequence-based predictions and functional outcomes in complex biological systems.